Victoria Dougherty's Blog, page 16

November 22, 2016

A Little Note of Thanks

This is a list – just a list of things I’m grateful for. Nothing more, nothing less. It’s stuff I don’t think about most of the time, but that undeniably bring joy and purpose into my life. Things that perhaps you don’t think about either, but might put a smile on your lips, conjure a memory, remind you of a dream…

This is a list – just a list of things I’m grateful for. Nothing more, nothing less. It’s stuff I don’t think about most of the time, but that undeniably bring joy and purpose into my life. Things that perhaps you don’t think about either, but might put a smile on your lips, conjure a memory, remind you of a dream…

I’m grateful for my mother, and our loving, annoying, complicated and sometimes strange relationship. And that there are a bunch of black-eyed Susans that grow in our backyard right around mid-summer. My daughter puts them in her hair, making her look like something between a fairy and hippie.

I love when wispy clouds wrap around the full moon like a piece of white linen around a fat auntie’s belly…dirty jokes, I love those, too…and the way footsteps echo inside of an empty church.

I”m grateful for my youngest daughter’s scars, which serve to remind me how hard she fought for her life and how hard her doctors worked to save her…for contrarian opinions that challenge my most staunch beliefs…for a peanut pie recipe that sounds great, but I’ve yet to make…for my son’s pet snake, Fellina, because I don’t have to do one damned thing to take care of her…for a son who takes care of his own snake…for the wasp I sat on that didn’t sting me…the red and green light bulbs we screw into our porch lanterns every holiday season…that my husband makes my coffee every morning, and my cocktail every night.

Cocktails in my husband’s office

In a grotesque way, I’m grateful for the swarm of houseflies that somehow got trapped between my office window panes and the storm windows just behind them…for the funny baby videos I watch with my twelve year-old daughter…and the smell of sweat and hormones that linger in our house after my teenage son has his friends over.

I love that my neighbors always say hi…that I speak Czech…that my husband told me I was pretty just last week…that there are ghosts in my house…that my nine year-old daughter is really into spaghetti westerns…that nobody in my family likes okra…but that we all love to dance to 1970s funk.

Then there’s the absolute insanity of our day-to-day lives – the sports, the Scout meetings, the school events, that create a rich flow and make us serve the greater good of our family…the fact that few things we truly care about have come easily…the taste of honeysuckle…the powerful combination of toothpaste and mouthwash that keep our teeth clean and our breath fresh…the invention of penicillin…and pasteurization…and vaccines…the space program…the human genome project…that Galileo, Michelangelo, Marcus Aurelius, America’s founding fathers, Ernest Hemingway, Winston Churchill, Oprah, Jonas Salk, Moses, David Mamet, Nelson Mandela, Vaclav Havel and Eleanor Roosevelt ever existed.

Great walking sticks – love those…the sun as it breaks through heavy cloud cover…the way the fall wind blows leaves in a cyclone…a good game of hide and seek…fake mustaches…southern accents and southern cooking…the Irish…the Jews…cringy disco songs…constructive criticism…nice butts…my best friend’s cat obsession and the songs she writes about it…a nagging conscience…lipstick…black licorice…campfire smells…yodling…ladybugs…insect repellent…candleabras…fiery sunsets.

And so much more, but I won’t put you through that.

Thank you for reading and for being a part of my life. And have a wonderful Thanksgiving!

Thanksgiving at The Doughertys, 2015

November 11, 2016

How Country Music Made Me a Better Writer

I wasn’t always a die-hard country music fan.

I wasn’t always a die-hard country music fan.

Growing up in Chicago, and subsequently moving to other cities like Prague and San Francisco, I was raised on a steady diet of screaming guitars, Blues, a smattering of Jazz, and the occasional hipster band.

Don’t get me wrong – I still love them all! They’ve been the soundtrack to some of the best times in my life and when a song like Jane’s Addiction’s “Been Caught Stealing” comes on the radio in my car, I go off like a firecracker – pounding my hands on the steering wheel and frightening my children.

It wasn’t until I was in my early thirties and actually moved to a rural area that country music made its way onto my radar. Then subsequently wormed it’s way into my heart. A couple of years into living in my new home town, I realized that honky-tonk had pretty much taken over my iPod, leaving The Clash, Bowie, countless British New Wave bands and Madonna lonely for play.

(The Rockabilly songs of the Stray Cats got to stay in the fold.)

I’ve got to admit that a lot of my city slicker friends found my new taste in music questionable. Some openly wondered if my move to central Virginia didn’t coincide with a minor head injury.

City slicker friend: “You actually like John Denver. Really like him. You don’t listen ironically?”

Me: “I think he’s one of the great songwriters of the twentieth century.”(I’m deadly serious here)

City slicker friend: “Oh.”

Country music just ain’t on the playlist in yankee cities. Sure, a city dweller might enjoy “cool” country stars that have had Hollywood movies made about their lives. Singer-songwriters like Johnny Cash and Loretta Lynn come to mind. But for the most part, country music to a city person runs neck in neck with elevator music and polkas when it comes to their listening pleasure.

And I was right there with them.

It took changing my habitat dramatically to inspire me to learn an entirely new repetoire of songs that have little to no relationship with the good ole days of my teens and twenties.

I slowed down, started working out of my home office, and found myself noticing how the breeze would blow through so many leaves on a summer evening that I’d swear I was listening to wind chimes. Without even meaning to, I got to know – intimately – the movement of sunlight throughout the day and the phases of the moon. I can’t sleep when the moon is full, I’ve learned, so I might as well put on something soft. Maybe Willie Nelson.

It was finally seeing what a holler really looked like, and hearing the truly terrifying shriek of a fox’s mating call. Driving on roads called 22 curves (and for good reason), drinking whiskey in a rocker on my front porch (yes, we really do that), or hearing my daughter say her dream car is a pick up truck (not kidding here).

Still, all of those genteel country living experiences led me to water, but they didn’t make me drink. What did was my congential love of a great story.

Because in country music, I’d found some of the best lyrical storytelling I’d ever heard, and it was not confined to the usual trilogy of sex, drugs and teen angst that can make great music, too, but gets a bit repetitive. And frankly, starts to lose its oomph after you’ve had a kid or two.

Even some of the schlockiest country tunes tend to have very adult themes that present a complicated set of circumstances. Like a good book.

A country singer will warn you not to come home a drinkin’ with lovin’ on your mind, tell you to stand by your man, lament that if their phone still ain’t ringin’, they assume it still ain’t you. They teach you how to play the game of life through a game of cards, fall into a ring of fire, and go to Jackson, Mississippi looking for trouble of the extramarital variety. They sing about their daddies and their wayward loves, their friends, their problems, the mountains they grew up drinking in like moonshine. They take you this close to their face, till you can smell their breath.

And over the past decade – more than poetry, even more than reading – country music has inspired the way I’ve constructed the personalities of some of my favorite fictional characters.

Johnny Cash’s Delia, A Boy Named Sue and Number 13 colluded to help me create a bulemic Hungarian assassin with a penchant for rich food and sadistic murder…and a heart for only one woman.

Frankie Laine’s Wanted Man showed me how impulsivity and desire can spawn a fledgling outlaw.

Dolly Parton’s Touch Your Woman guided me in writing a heartbreaking love scene between two characters about to face their doom.

And Garth Brooks’s Friends in Low Places, about a regular guy who crashes his ex-girlfriend’s wedding to a high roller, always reminds me to give my characters a sense of humor – even amidst some of their most painful, cringy episodes.

Well, I guess I was wrong

I just don’t belong

But then, I’ve been there before

Everything’s all right

I’ll just say goodnight

And I’ll show myself to the door

Hey, I didn’t mean

To cause a big scene

Just give me an hour and then

Well, I’ll be as high

As that ivory tower

That you’re livin’ in

‘Cause I’ve got friends in low places

Where the whiskey drowns

And the beer chases my blues away

And I’ll be okay

I’m not big on social graces

Think I’ll slip on down to the oasis

Oh, I’ve got friends in low places –Garth Brooks

These artists continue to teach me not to waste words and to tell a compelling story in the shortest amount of time possible, so as not to bore a reader with competing descriptions and over-wrought emotions. They remind me that I don’t need a shoot-out or car chase or even a bunch of sex to put tension or excitement into a scene.

And they’ve shown me that having heart and brazen sentimentality can illustrate a powerful truth that kicks even the most cynical reader in the gut.

So, writers…and readers…next time you need to boost your imaginations, or just want to hear a great yarn – find your local country music station (I swear, even big cities have one), sit back, put your boots up and have a listen.

October 19, 2016

Why We Don’t Tell Our Kids How We Vote

We have three children, ages fourteen, twelve and nine. I’m not sure when exactly my husband and I made the firm decision not to tell them how we vote, but I know it was when they were really young. Pre-political young. I remember one of them thought Barack Obama was the name of a candy bar.

We have three children, ages fourteen, twelve and nine. I’m not sure when exactly my husband and I made the firm decision not to tell them how we vote, but I know it was when they were really young. Pre-political young. I remember one of them thought Barack Obama was the name of a candy bar.

I think it started as something of an experiment. We thought it could be beneficial to our kids and illuminating for us to see how their political beliefs developed if we exposed them to both sides of the debate. If we tried our best not to infuse our biases into their thought processes, yet demanded a certain degree of rigor. “I got it from the internet” is never the correct answer when offering support for your point of view, we would tell them.

In those early days, I guess you could say there were definitely some high falutin’ ideals behind our decision. We wanted to teach them how to think as opposed to what to think, in the hopes that it would make them more tolerant and less lazy. We didn’t like the tone that had crept into political discourse – the rants on social media and the everyday erasure of basic manners – and were hoping to help our kids become broad-minded enough to be comfortable outside of their own tribe.

But our decision was also rooted in how our own political opinions were formed as we grew into adulthood.

See, I was raised in a household of passionate beliefs formed by extraordinary circumstances. My grandparents and parents had front row seats for the holocaust and the Cold War, and their true to life stories were more thrilling and heartbreaking than most feature films. They knew from their own personal experience what it was like to be cold, hungry, frightened and exiled. To have made their home in a new country, knowing they could never return to the place where they were born. To have learned a brand new language – taping lists of vocabulary words by the kitchen sink, at the bedside table, next to the toilet.

They also knew what it was like to work hard and claw their way up into the middle class, to feel the buzz of success and the joy of watching their kids take piano lessons, graduate from college, publish books in the language that had sounded like a garbled cassette tape to them only a couple of decades earlier.

I learned pretty early on that even some of the most “out there” convictions – conspiracy theories about Soviet-spy presidential candidates, for instance – weren’t the result of either ignorance or stupidity. They evolved out of experience: “I saw this happen in the old country and it could happen here.” Or perceptions of identity: “I am a good person. Good people don’t like poverty. Candidate X says he doesn’t like poverty, therefore I will vote for X.”

As a result, I never saw the other side as the villain. I just figured we wanted the same things, pretty much, but had a different idea of how to get there.

My husband was raised in a die-hard democrat household where union wages put food on the table. His first job was doing opposition research for democrat and former presidential candidate Richard Gephardt and it lit a fire to his innate passion for debate. He now works for corporations, politicians and trade associations and has to get his head around both sides of an argument on a daily basis. Election time is hilarious around our house since the pollsters have no idea what to make of us. We watch both Fox and MSNBC and have at one time or another subscribed to everything from Mother Jones to the Weekly Standard – usually at the same time.

I guess you could say we were well prepared as we began the massive undertaking of making our kids do their own political due diligence. And to be honest, we haven’t always been sure our way was going to work. There are a lot of opinions out there, and who’s to say our little darlings wouldn’t just slack off and glob onto one of those? My mother has certainly never hidden her political beliefs from them and gleefully tries to influence their thinking.

And to be honest, we haven’t always been sure our way was going to work. There are a lot of opinions out there, and who’s to say our little darlings wouldn’t just slack off and glob onto one of those? My mother has certainly never hidden her political beliefs from them and gleefully tries to influence their thinking.

We understood early on that we couldn’t just sit back and do nothing more than refuse to divulge anything either. We had no intention of leaving our kids to navigate the political spectrum and corresponding media circus alone. As exhausting as the prospect was, we decided to actively play devil’s advocate for every single issue and try to give the best possible arguments for both sides – even on opinions that inflame our passions.

It’s a lot of work and tipping our hand has always been a concern.

But all in all, I think we’ve done a pretty good job with confusing our children as much as we confuse the pollsters. At one point this summer, our son did a one-eighty between whether we were democrats or republicans about six times, until finally giving up and stating, “You two are evil.” Now, I realize our way is not the way for everyone. Nor do I advocate that it should be.

Now, I realize our way is not the way for everyone. Nor do I advocate that it should be.

If the very thought of one or more of your children potentially forming a political belief that doesn’t reflect your own is deeply upsetting to you, then you might think we’ve done a lousy job. Only one of our kids has fully taken on our top-secret political views. Another refuses to tell us (we deserve that one), while still another is way off the reservation.

But overall, things have turned out pretty well so far.

Some of the most hilarious, thoughtful and downright brilliant political observations have come from our children. That alone has been worth it. Having to consistently argue the other side has also enabled us to keep learning and has even forced us to rethink or at least introduce more nuance into some of our most staunchly held beliefs. Even on hot topics such as abortion, capital punishment, and racism.

And it’s nothing short of amazing to watch how our kids’ innate personality traits influence their judgements. How being outdoorsy, interior, overly sensitive, chronically ill or even musical plays its role in the way conclusions are drawn, values are interpreted. It has helped us understand them better and established yet another layer of trust that we hope will keep them close to us during their more turbulent years. Surely, their current political opinions will evolve and change. Come five or ten years from now, our children’s notions of politics and the world at large might look nothing like they do now.

Surely, their current political opinions will evolve and change. Come five or ten years from now, our children’s notions of politics and the world at large might look nothing like they do now.

People evolve.

Political parties flip-flop.

The world moves on from our youthful perceptions.

Sometimes we discover we were just plain wrong.

And we hope we’ve given our children the tools to be as open and conscientious throughout their lives as they have been during this admittedly bizarre election cycle. We hope they don’t lose their temper too often when faced with beliefs that contravene their own. We hope they maintain their sense of humor and build a thick skin. Most of all, we hope they remain gracious towards all citizens of our great country, and retain their ability to change their minds. To us, that’s success.

October 3, 2016

Purpose and Perfection: The Many Roads to Paradise.

Jan Saudek “The Slap”

I read somewhere – perhaps at an art exposition years ago – that Jan Saudek, one of my favorite photographers – believed that his purpose as an artist was to bring beauty into the most wretched corners of existence. As he spent a memorable part of his childhood in Terezin, the Nazi “show” camp in Czechoslovakia, it’s easy to see how he could view the monstrous and the holy with the same, adoring eye.

At least it’s easy for me. Others have called Saudek’s work “disturbing,” “violent,” “deviant” and “shocking.”

And certainly, a photo like the one above – a man angrily slapping a woman who seems to be enjoying it – can elicit some pretty strong emotions.

That’s precisely what I love about it.

If we strip “The Slap” of its obvious sexual undertones, of its politics, of its sarcasm, what you see is not just the wreckage of some sort of relationship – a husband and wife, adulterous lovers, perhaps, or a John and his harlot. You see two people holding on to something. Just barely, maybe. But it’s there in her smile. You can’t escape it. Her expression visits you over and over again – long after you’ve gone home and tried to put the photograph out of your mind. You might keep asking yourself what the hell she was smiling about?

I always thought I knew.

Jan Saudek “My Mother”

My mother endeavored to have a child – me – while in a wretched marriage. She didn’t do it to try and save her marriage. That ship had sailed years before. After the shouting matches and the violence and the blackmail and the affairs. She most definitely wanted out.

What made my mother approach my father about having another child – even when she knew that her marriage was utterly doomed, and she could hardly stand to be in the same room with him – was grief. Plain and simple.

My brother died about eleven months before I was born. His was a sudden, unfathomable death. He was only four, and died essentially of stomach flu. Only a couple of days before his death, he’d been climbing trees and picking berries from a neighbor’s garden, collecting bugs. Then, in what seemed like the blink of an eye, he became sick, then dangerously dehydrated, and ultimately drew his last breath.

He would remain four years old forever.

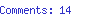

Jan Saudek “First Steps”

My mother says the only thing that kept her from taking her own life at that time was that my then seven year-old brother needed her. He was also grieving and looked to my mom to get them through that horrible experience. To bring hope back into their lives. And the only thing that gave my mom hope for the future was the prospect of bringing another life into the world. Not to replace my brother, but to bring joy back into hers and her surviving son’s lives. She needed to do something – anything – to the fill the black hole that my brother’s seemingly senseless death had left behind. The one that was sucking the life out her, crushing her spirit.

So, you could say I was born of lies, broken dreams and most of all sorrow. Grief was the sole purpose of my conception. Perhaps not surprisingly, grief – in one form or another – has become the purpose of my life’s work.

Now, I don’t mean to be a downer here. My books, stories and essays are not all about gloom and doom for heaven’s sake. I think more than anything they’re about hope. About the fragile, shimmering, silver lining that forms around every puff of smoke we see rising from the ashes of our latest heartbreak. What’s beautiful to me is that it’s always there – no matter how bottomless our pain seems to be. It can take the form of an unexpected gesture of kindness from the least likely person under the least likely circumstances, to a revelation you could have never imagined otherwise, to the fundamental relaunching of a life – the reinvention of an identity.

And it’s contagious.

Jan Saudek “Man on Motorcycle”

When my youngest daughter was born with a catastrophic illness, I remember a conversation I had with one of her care givers – a doctor or nurse, I can’t remember which. But I think I remember her name. It was Diane. Diane told me about how working at the Children’s’ Hospital of Philadelphia – where my little girl was born – had expanded her own definitions of love. How before her job there, she could not understand the connection between a parent and child with severe brain impairment, for instance.

Diane recalled how one day she watched a mother as she brushed her teenage daughter’s hair. The daughter had been born with such low brain function that she was deemed a vegetable and needed help with every aspect of her care. And she just laid there all the time. She could never smile, hold her mother’s hand with intention. Her eyes didn’t even follow as her mother walked around her hospital room.

But here was her mother – every day – washing her, fixing her hair, filling her feeding tube, giving her dignity.

“It made me understand love on such a deeper level,” Diane told me. “It’s not about them – all of those kids with really big problems. It’s about us. How they change us and make us better.”

She then leaned in to me, like she was afraid of being heard.

“With genetic testing, we now have the ability to manage so many terrible problems out of our lives – and that is such a great thing. But we also lose something as we get closer to perfection.”

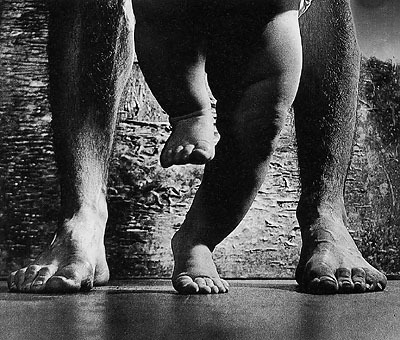

Jan Saudek “Woman and Skull”

I’ve always thought perfection was overrated. Perhaps because I was born of so little that could resemble love, and during the worst time of my mother’s life. Diane’s words resonated so deeply with my own perceptions of purpose – my purpose. The grief without which I wouldn’t even be here.

And no, I want to be clear. I don’t think that couples shouldn’t get genetic testing, or try to cure their children not only of major illnesses, but even relatively minor issues – like allergies. I’d do anything for my kids. It is our biological imperative, at least according to both Charles Darwin and the Bible, to reach for the stars both literally and figuratively. To improve our lives and the lives of our children in every possible way we can. To crawl out of the swamp and grow legs to stand on and arms with which to make tools, and snatch apples off of trees, and hold our loved ones. To leave Egypt and spend forty years in the desert until finding the promised land. To enter heaven, or nirvana, or whatever kind of utopia you believe in.

It’s just that my purpose, I believe, is to remind anyone who will listen that there’s more than one way to get to paradise.

Jan Saudek “Baby and Man”

Click below for your free download of COLD: Essays of Love, Faith, Family and Other Dangerous Pursuits:

September 14, 2016

Decaying Worlds – Inhabiting the Ruins of a Structure and a Soul

Recently, my husband sent me an article on abandoned places. These were once glorious, but now forsaken European castles and villas. Dying tokens of splendor and opulence captured by architectural photographer Mirna Pavlovic, who has a thing for deserted structures. She risks getting arrested, falling through rotted floors, or just plain getting cooties by climbing fences and ignoring “no trespassing” signs in order to get some truly incredible shots. Ones of beautiful homes that for reasons we can only imagine, have been ditched and left to slowly decay. Their murals, marble and artisan carpentry are being encroached upon by the elements, until one day they will become part of the natural earth again.

Recently, my husband sent me an article on abandoned places. These were once glorious, but now forsaken European castles and villas. Dying tokens of splendor and opulence captured by architectural photographer Mirna Pavlovic, who has a thing for deserted structures. She risks getting arrested, falling through rotted floors, or just plain getting cooties by climbing fences and ignoring “no trespassing” signs in order to get some truly incredible shots. Ones of beautiful homes that for reasons we can only imagine, have been ditched and left to slowly decay. Their murals, marble and artisan carpentry are being encroached upon by the elements, until one day they will become part of the natural earth again.

“They are never truly dead, yet never really alive,” Pavlovic says of these villas. “Precariously treading along the border between life and death, decay and growth, the seen and the unseen, the past and the present, abandoned places confusingly encompass both at the same time, thus leaving the ordinary passerby overwhelmed with both attraction and revulsion.”

I love the duality she sees in these spaces. That the ghosts who visit while she snaps her pictures may tell a very different tale to her than to someone else. They might speak of folly, dancing, formality, and wing-dings. Or anguish, broken dreams, empty promises, death, hope, rebirth. Perhaps all of those things jumbled up into one, long Russian novel.

“Reminds me of the stories you write,” my husband told me.

And he has a point. It seems I cannot write a story without a double meaning or phantom of some sort. While Pavlovic focuses on place, I train my eye on people – emotion, memory, the senses. Picking apart and reassembling the interior mechanisms that conspire to make up a soul. Urging my imagination to recognize the spiritual components which make that soul eternal. It may seem counterintuitive, but I feel an inherent sense of optimism when I’m dreaming up characters who have been disavowed, betrayed, left behind to descend into ruin. From there, the only way is up. Thought by thought, step by step, decision by decision. Understanding this narrative is what gives life meaning. It opens our hearts to mercy.

It may seem counterintuitive, but I feel an inherent sense of optimism when I’m dreaming up characters who have been disavowed, betrayed, left behind to descend into ruin. From there, the only way is up. Thought by thought, step by step, decision by decision. Understanding this narrative is what gives life meaning. It opens our hearts to mercy.

So, I understand Pavlovic’s fixation.

The chronicling of this organic and at times supernatural metamorphosis is the sole reason I’ve never even considered giving up on being a fiction writer. Even when the frustration and fear of failure has been so great that it’s kept me up at night, found me tearing through my kitchen to cook up gourmet meals no one in my family really wants to eat, made me say mean things to my mother’s bird.

Because writing is so much more than a skill to me, or a way to do my part in keeping my kids ensconced in their expensive enrichment activities. Writing is an extension of faith, of compassion, of trying to leave behind something that will matter to someone else.

When I take time off from my stories for any extended period, I find myself averting my eyes from the ruined places and ruined souls that I would otherwise be exploring. Not because I can’t bear to look at them, but because I can’t spare the time. The hours in the day fill up with cooking and laundry and driving. And for a while, yes, the house looks better, our lives are more organized, our kids are always on time for their events.

Those intervals are important, too, and I’m not knocking them. Nor would I give them up.

But when they stretch out for too long, my interior life becomes a bit more stark. I might be a more competent wife and mother, but not necessarily a better one. I start to pick teams instead of examining issues. Ugly words begin to mean less, and even make me a little giddy. They feel like contraband – smoking a cigarette behind the shed doors. If I look away for too long, I start to give myself permission to retreat comfortably behind the sanctimony of political correctness, biblical passages, or quotes from my favorite philosophers – believing, wrongly, that I’ve got this empathy thing down. Smug in my place in the world, judgement and condescension worm their way into my daily thoughts. I have so much less to teach my children.

If I look away for too long, I start to give myself permission to retreat comfortably behind the sanctimony of political correctness, biblical passages, or quotes from my favorite philosophers – believing, wrongly, that I’ve got this empathy thing down. Smug in my place in the world, judgement and condescension worm their way into my daily thoughts. I have so much less to teach my children.

I don’t mean for it to happen, it’s something that creeps up – like the ivy in some of the mansions Pavlovic likes to photograph.

And that’s when I know.

It’s time to climb that fence again, march past the “no trespassing” sign, risk falling through a rotten floor and getting cooties in order to spend some time inside a soul – perhaps denied, friendless and pitiful, but still standing.

Read the article on Pavlovic’s amazing work here.

August 29, 2016

The Eye of the Beholder

I live in a beautiful place.

My daughter on our neighbor’s fence

Misty, Civil War battlefield mornings, hummingbirds zigzagging like bees from one open-mouthed hollyhock to the next, the smell of honeysuckle, dew and wood smoke in a heavenly perfume. It wafts in as I open my front door. The morning sun illuminates a large oil drum stain on our ancient wood floors, one of many historical scars in our house.

And this is the splendor of just any old day.

I haven’t even begun to tell you about the mountains, the orchards, the vineyards, the fact that we have as many rivers, streams and creeks as we do roads. Or the hot air balloons that float leisurely over our town on clear, fall days.

This view is pretty much walking distance from our house

Where I grew up in suburban Chicago, unequivocal beauty was pretty scarce. The winters were harsh and a fresh snow would descend from white into gray within hours of falling. We’d have to make our Sno Cones quickly.

The city’s skyline was breathtaking – especially at night – and anywhere near Lake Michigan seemed like a vacation spot. But most of Chicago was industrial, gritty and rough around the edges in a way that was only charming if you grew up there. Even the so-called “beautiful” neighborhoods – the rich ones – weren’t all that great. They were fancy, yes, but when compared to some of the places I’ve lived in my adulthood, they were and remain fairly meh.

Truly beautiful days were uncommon enough when I was growing up that when they came, especially after a long and bitter winter, kids skipped school and adults called in sick. Or at the very least, tried to spend as much time outside as possible – maybe taking an extra long cigarette break (those were the days, right?), or offering to run an errand they would normally duck like an uncovered sneeze. In the city, people sat on their stoops after work, while in the burbs, they migrated to their porches or decks.

These were moments of stolen magic every bit as soul-stirring – at least for me – as the gentle, classical beauty of the Blue Ridge Mountains in my backyard today. They were beautiful because of the stockyards across town, the stained bricks and dirty smells, the mornings so frigid it took real effort to make an expression on your face, or grip your keys firmly in hand.

This is no exaggeration.

Those tiny glimpses of something fresh and wonderful – the dandelion that grew in the crack of a sidewalk, the vacant lot – weedy and clovered, offered plenty of fodder for my imagination. To this day, I can say without reservation that I have seen nothing as riveting as a thunderstorm viewed from my parent’s cluttered garage. I would sit in a rusty folding chair as rain pummeled our driveway, lightening cracked above the roof of the mud brown ranch house next door, and wind battered our American flag. It felt Biblically wild and dangerous. Like anything could happen.

The creek across the street, nestled next to a four-lane highway, was like the wilderness to my friends and me. We pretended to fish in it during the summers (the water was too iffy for us to eat anything we might have caught) and it became our ice skating rink in the cold months. A grouping of trees huddled on no more than two, undeveloped acres on the other side of our block, was uniformly referred to as “the forest.” Every winter a dramatic icicle sculpture would burst out of split gutter somewhere – a surprise, poor man’s Michelangelo.

The creek across the street, nestled next to a four-lane highway, was like the wilderness to my friends and me. We pretended to fish in it during the summers (the water was too iffy for us to eat anything we might have caught) and it became our ice skating rink in the cold months. A grouping of trees huddled on no more than two, undeveloped acres on the other side of our block, was uniformly referred to as “the forest.” Every winter a dramatic icicle sculpture would burst out of split gutter somewhere – a surprise, poor man’s Michelangelo.

It was more than enough. In fact, the very personal nature of the beauty I experienced as a girl growing up in an unbeautiful place was what made it so special. To this day, driving down Interstate 55 in Illinois – what my husband calls “possibly the ugliest corridor I have ever seen” – makes me sigh. Forget the billboards and congestion, the railways, the chimney stalks billowing smoke, one’s my youngest daughter mistook for “cloud factories” on our most recent visit. This was the path to Chicago in my youth, and evokes nothing but feelings of excitement and possibility for me. I loved the way the streetlights came on at night, their yellow, harvest-moon glow. I savored the smell of air-conditioning puffing out of the vents of our metallic green Lincoln.

Perhaps it meant so much to me then, and still does now, precisely because of its paucity and particular nature. It belonged to me. Not even my own husband has grown to appreciate it over the years – no matter how many times I’ve tried to explain.

One of several “cloud factories” on Interstate 55 in Illinois

The beauty of where I live now – undeniable, unrelenting in every season, every incarnation – belongs to everyone. There is not a sane person living who would deny it.

And I do love it.

But it’s not mine.

In John O’Donohue’s book Beauty: The Invisible Embrace, he writes at great length about how beauty, whatever our interpretation of it, is the ultimate source of compassion and hope, the spark of both our collective and individual imaginations. The influence of beauty on our creative minds, he contends, is the only true tether to innocence.

“[only the imagination, through beauty] has retained the grace of innocence. This is no naive, untested innocence. It knows well the shadows and troughs of the world but it believes that there is more, that there are secret worlds hidden within the simplest, clearest things. The imagination is not convinced of the world of external fact. It is not persuaded by situations that pretend to be finished or closed. The innocence of the imagination is willing to see new possibilities in what appears to be fixed and framed. There is a moreness to everything that can never be exhausted.” — John O’Donohue

The moreness is what got me. That a storm watched from the garage of a 1960s style house can be as moving as a full, double rainbow over a pasture of wildflowers in the Virginia countryside is a testament to the moreness of the imagination. To the power of beauty as muse to the heart and mind.

John O’Donohue tells us, “Beauty is only a visitor. It’s not meant to stay.” But I’m not so sure. The beauty of my ugly childhood home has stayed with me, a travelling companion as I’ve passed through some of the most objectively beautiful places in the world. It will always be the standard to which I hold any surrounding, and the inspiration for some of my deepest, most contrary thoughts. The ones that help me understand people who are nothing like me, whose views I may find abhorrent, or whose values I deem silly.

The sumptuous beauty I live amidst today gives me serenity. It does inspire me. But my beauty – that of the chain-link fence, the brief summer, the gangway, the wall to wall carpeting, the tchotchkies, the plains – has been a wellspring of empathy and artistry. A dogged champion of independence and the fight for originality.

“The Spindle” sculpture of suburban Chicago – called “The ugliest sculpture in the world” until its demolition in 2007.

August 9, 2016

Happy Birthday, Cold! Now Let’s Party and Unwrap Some Presents!

When I started this strange little blog four years ago, several knowledgeable people – journalists, my agent, successful bloggers – warned me that long form blogs were doomed for failure. I should keep my posts under 300 words or else risk exhausting the reader. People don’t have time for anything more, they said. The days of a real conversation were over.

And I really did try to follow their advice. But the truth is, I’m just not a love em and leave em kind of writer. So here I am, many thousands of followers later, with most of my posts averaging 1200 words. I think I’ve proved that bit of wisdom wrong, but who knows? Maybe if I’d stuck to the good advice of professionals, I’d have a readership numbering in the six figures? Hard to say. But I do know that if I had taken their advice to heart, I wouldn’t have developed the level of intimacy with you, Cold readers, that I feel took root early on this simple WordPress page. And it has grown into something I never expected.

Cold is a very special place for me. It’s a sanctuary where I share heartfelt thoughts about the things that most touch my soul. I take very real personal risks here, laying bare what are for me the fundamental truths about love and family and loss. Delving into things as private as passion and faith. As particular as art and music and its effect on my relationships, and the way I tell a story.

I muse about the writers life – how comically tragic it is for a grown woman – a wife and mother for the love of God – to spend her days in a little, red room filled with weird memorabilia, staring at a screen and obsessing about what imaginary people might say or do under fantasy circumstances.

And without really setting out to do so, I launched a forum here that more than anything is about friendship. Close friendship. Nearly every post I’ve published is the kind of in-depth conversation that I would have with a true friend. And so many of you continue to reward me with your profound and unfiltered comments and stories. Even your secrets. I know that’s not necessarily an easy thing to do – essentially opening a vein in a public space, letting your guard down just to connect with another human being.

So today, I want to reward you with sort of a reverse birthday present.

COLD is a collection of essays, most of which have appeared on this blog. Several have been expanded upon, thanks to your thoughtful responses. Your feedback stretches the reach of my imagination, making me a better thinker and writer. I owe you a lot for that, which is why I want to offer Cold readers a free digital copy of COLD: Essays on Love, Faith, Family and Other Dangerous Pursuits. Designed by Chris Bell at Atthis Arts, with original photographs by filmmaker John Michael Triana, the collection is more than just an anthology. It is, I hope, an experience that combines the written and the aesthetic. Is something you can hold close, reflect upon, and share with friends.

Just click on the link below, enter your email address, and you will be taken through an easy, step by step process for downloading your free copy. Kind of like unwrapping a birthday present, but without the mess of silly, loud paper and festive ribbons.

And if COLD has meant something to you, I ask that you please take the time to leave a review on Amazon (http://amzn.to/2bb8H6Q) and Goodreads (http://bit.ly/2aHCOQj), or whatever is your prefered platform. It doesn’t have to be a long review, just honest. A couple of sentences will do. And feel free to mention that you’re a Cold blog reader, who received the book as a gift from Yours Truly.

Above all, thanks.

And here’s your link:

http://victoriadoughertybooks.com/get-your-free-book/

July 24, 2016

Review: “Welcome to the Hotel Yalta” by Victoria Dougherty

I am a big fan of Victoria Dougherty and her Cold Noir Writing. Having met her in person in Prague, the city with a Cold War history, and scene of her amazing book “The Bone Church” , d…

Source: Review: “Welcome to the Hotel Yalta” by Victoria Dougherty

June 8, 2016

From Movie Stardom to Baseball: Childhood Dreams Leave a Mark on Our Lives

Recently, I had a long and winding talk with friends about childhood dreams. We each told our story, prompted by a “Question of the Week,” which is the way we keep in close touch during the course of our busy lives. All of us are bound to answer, unless there’s a tsunami or something.

“So, I asked, What was your childhood dream?”

My friend Ellen chimed in immediately. She has always wanted to be a writer and is one. Fiction has been a constant in her life – throughout moves, changes in relationships, child-rearing and illness. It has never left her side and she cannot imagine herself doing anything else. Not even when she was a kid, and her friends wanted to be fairies, firemen or just super rich. When it was Ellen’s turn to float out her heart’s desire, she always said “writer.”

However, Ellen was the exception.

What was so interesting was how the rest of us did not end up actually pursuing our childhood dream, but somehow that dream informed our careers, our sensibilities and lifestyles. The dream may not have been a constant, like it has been for Ellen, but more a constant companion. That friend who’s always whispering, “Wanna go on a road trip?” “Are you going to go all the way with him?” “Let’s ditch school and go to the beach!”

When I was a kid, I wanted to be Carol Burnett more than anything else in the world. I watched her variety show every week, memorized her skits, wrote my own – even filmed a few of them on an old Super 8 camera (it wasn’t old then). Being funny, making people laugh seemed an honorable profession to me, one as worthwhile and noble as being a doctor or a teacher. At my darkest times, during my most Charlie Brown childhood moments, Carol was always there for me. And I wanted to do what she did – make people feel good afer a rough day or year.

Of course, my comedy dreams were not exclusively altruistic. I loved watching people spit strawberry milk out of their noses after one of my cracks, disrupting class, earning a smack on the head from Sister Margaret Ann. She was built like a wrestler, and her meaty palms were powerful – but it was so worth the headache, the ringing in my ears.

To this day, being called funny is the highest compliment I can receive. So much better than being told I look beautiful. When asked by a mutual friend what first attracted my husband to me, he said, “She had a real sense of humor. Most women I’ve gone out with like laughing at jokes but never make any.”

That made my heart flutter.

Yet somehow, even though becoming Carol Burnett was without question my fondest dream, I became a novelist who writes thrilling spy adventures and epic, heart-wrenching young adult love stories. All very serious stuff.

But I can’t deny that there’s a deep current of humor in everything I’ve ever written. Even my most somber essays on this blog – about death or faith or true love – tend to be embroidered with some manner of joke. I guess because of Carol and her influence on me, I cannot stand taking myself too seriously. In even the greatest heartbreak, I leave room for the absurd, the ironic, or downright hilarious, and have little tolerance for victim culture. Not because I don’t acknowledge that victims exist and that their pain is real, it’s that I feel succumbing to victimhood is toxic. As unhealthy as smoking five packs of cigarettes a day and washing them down with a fifth of vodka.

I see good humor as a trait of good character, not just a fun personality feature. During the course of my life, a person with no sense of humor has typically been my natural enemy in the wild. We circle each other carefully, and usually end up just backing away.

But while chasing off the sullen and tedious, my childhood dream has sucked into my orbit people who share my world view, and don’t even blink when I tell them that Carol Burnett has had the greatest influence on my life. Not Gandhi, not Martin Luther King, but Carol. They not only understand, but say, “I totally see that!”

Because they have had a similar journey.

My friends Nick and Jess both took some of the best parts of their respective childhood dreams and helped calibrate them for their growth and changing needs.

Jessica wanted to be a movie star, but became a tech entrepreneur instead. Those are seemingly unrelated careers on the surface of things, but if you could see how Jess lights up any room she enters you’d understand. She loves making the pitch, and hatches approximately three life-changing, sh*t-disturbing schemes a day. She is a charismatic and ethical leader.

“You are a movie star,” I told her.

Her husband, Nick, wanted to be a baseball player, but now writes baseball mysteries. His alter ego, Johnny Adcock, is an aging major league pitcher who supplements his diminishing baseball salary with high-priced gum shoe work – helping rich friends being blackmailed by murderous gold-diggers and such. By writing baseball mysteries, Nick has gotten to hang out with a crew of baseball players he’s interviewed for research. He’s played ball with them, drank with them, lived vicariously through them.

And maybe that’s what I’ve hit on here. The vicarious part. My friends and I – all creative people like writers, actors, and entrepreneurs – are a curious combination of wallflower and leader. We desire an inexorable amount of control not only over our own lives, but the lives or our characters or products, made-up people and gadgets we endeavor to use as avatars for our worldview, for being able to affect a mood, a belief, perhaps a childhood dream of someone else’s.

Of course, not everyone has allowed their childhood dream to stick around, and share space with with their more practical choices.

We all have friends who wanted to be musicians, scientists, chefs and never took one recognizable step in that direction. They seemed to have no invisible companion standing on their shoulder and telling them to take the dive. Not surprisingly, their dream died, and when you ask them about it now, they just sort of shrug or change the subject. Perhaps it’s because they’re unsatisfied with the path they chose, and don’t want to talk about it. Or maybe their childhood dream really did lose its allure. Like a second grade crush – based on a freckle-faced cousin’s ability to eat a worm without flinching – their dream perhaps seemed silly once they’d grown up a little bit. As a result, what they became in adulthood was perhaps a reaction to the old dream, an opposing stance.

Whatever the case, whether we fulfill them, absorb and repurpose them, or reject them outright, childhood dreams give so much more than mere career direction. They leave their mark. Some might say a scar. As for me, they are a fond memory, like a first kiss. I remember the taste of his lips, the thrill, the way his hand stroked my back and inched its way under my t-shirt just to feel my sun-kissed skin. But even that kiss, as intoxicating as it was, doesn’t compare to the way my husband leans into me and looks into my eyes, holding me tight. That’s the stuff truly realized dreams are made of.

May 11, 2016

Northern Lights, Southern Exposure: A Yankee’s Thoughts on Living in the South

I’ve been on a Sally Mann kick lately.

I’ve been on a Sally Mann kick lately.

In the span of a few days, I binge-watched a recent CBS Sunday Morning segment, then a documentary about her life and photography. And if that wasn’t enough, I read her memoir, Hold Still, and reacquainted myself with her stunning body of work (at least what we have of it on our bookshelves) – from the controversial photos of her young children in Immediate Family to What Remains, her visual meditations on death.

And yet, despite how compelling I find her process and meticulous attention to detail, what’s stuck with me most is her philosophy of capturing the local, the immediate, rather than the highly conceptual, the wide-flung and international.

She talks at great length about being a southerner and loving the south – warts and all. In the way you love your family, even if some of them make you want to put a nail gun to your temple. Or theirs.

After having now spent a good deal of my adult life in the South, interpreting Sally Mann’s work and reading her life story has made me think about my own evolution in thought about my adopted home.

I grew up in the suburbs of Chicago, surrounded by neighbors with last names like O’Malley, Dulik, Zito and Dumbrowski. And I’m a Yankee who moved south with many, if not all of the same prejudices that my northern peers excel at.

See if this sounds familiar: the South is racist, backward, quaint, overly-mannered, full of fake smiles. It’s uneducated, unenlightened, and uninterested in ever evolving out of its troubled past.

I won’t discount them. Stereotypes don’t appear out of nowhere in a puff of pink genie smoke. Like gossip, they hold some truth.

Except that the South is also beautiful in a weeping, classical sense. Lush. It’s air is like hot breath, and it’s people are neighborly, stubborn, courtly, and languorous.

When I dropped off an antique clock at a repairman’s in April and asked when I should plan on picking it up, the clerk said – I kid you not, “Why don’t you try back about Thanksgivin’ ma’am.” The place was as quiet as church. The man as leisurely as a sip on a Mint Julep.

As a compulsive storyteller and story-listener, living in the South has provided fascination and fodder for me. Like the Irish, Southerners are lyrical in their thought and speech, chronicling the local through verse, drama, a pick on a guitar.

Think Mark Twain, Edgar Allan Poe, Frederick Douglass, Kate Chopin, William Faulkner, Tennessee Williams. And this is only a sampling from the immediate post Civil War period – a time when the South was utterly devastated and had no business contributing to the canon.

Post war stars of the literati include Eudora Welty, Flannery O’Connor, Harper Lee, William Styron, Truman Capote, Tom Wolfe, Anne Rice, John Grisham, Pat Conroy and Tom Robbins, just to name a few.

(Ok, I know I went heavy on the writers here, but what do you expect?)

It is because of the South that we have Jazz, Country and Rock-n-Roll music. Around the world, hearts ache, flutter and rejoice to the distinctly southern sounds of Johnny Mercer, Louis Armstrong, Ella Fitzgerald, Elvis Presley, Johnny Cash, Dolly Parton, Lyle Lovett, Jimmy Buffett, REM, The Black Crowes and yes, Lynyrd Skynyrd.

Because there is a depth in Dixie, one that plays muse to those of us inclined to interpret and examine. Maybe sing a love song. It lies beneath the wrap-around porches and behind the polite banter. In the tiny, time-warp towns that dot the valleys.

It is evident in the writings of Thomas Jefferson, notably “The Declaration of Independence.” In perhaps one of history’s great ironies, this document, written by a southern gentleman and slave owner, includes what has been called the greatest sentence ever written:

“We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.”

Still, at least for Yankees, the Hollywood invented “Dukes of Hazzard” TV show seems a more typical example of southern culture.

Now, I’m not putting the blame squarely in the lap of un-watchable early eighties television here. It would appear the South’s reputation as a cultural backwater has been around for a while. It really took off in the 1920s, when Yankee writer H.L. Mencken penned a satirical piece highlighting the South’s inability to produce anything of cultural value. He became wildly popular after the publication of his essay, and his perceptions have stuck, taking on a life of their own and feeding the imaginations of coastal city rats.

Years ago, when I acted in a British play (“Grace” by Doug Lucie), I portrayed a southern woman. A theater critic (NYC born and bred) spotlighted my excellent southern accent while disparaging another actress whose cadence”seemed fake” to him. Only that I’d gotten my accent from TV and my fellow actress was a real live southerner from Alabama.

I’m not saying this to pick on the critic – not much, anyway. It’s just that we northerners think we know southerners the way people think they know Britney Spears. We’re vaguely aware that regional inflections exist, but are utterly incapable of distinguishing between a Texan’s drawl and a Virginian’s lilt. We snicker about the South’s preoccupation with the Civil War. The statues of Stonewall Jackson and Robert E. Lee, the re-enactors.

“War, war, war,” if I can quote Scarlett O’Hara. Get over it!, we say.

But can you really blame southerners for their obsession? The Civil War was the pivotal event in our country’s history – the one that scarred us, shaped us, grew us up and made us who we are today. It happened on southern soil – the fighting and the bleeding, the burning, the gouging and the tears. Then the aftermath. The shame which lives on.

As Sally Mann points out, southerners are the only non-immigrant Americans who know what it’s like to lose. To return home in utter defeat…to crawl back to their families quite literally on their hands and knees. To have been on the wrong side of history and morality.

When you look at other cultures who have had to navigate devastating losses – the Slavs, the Germans, the Jews, the African-Americans – they share with the American South a fixation on who we are that’s difficult for your average Yankee to understand.

Here is my interpretation.

Yes, the South is the place of lynchings and the Ku Klux Klan. But it is also a place of self-reflection, of having to own up to devastating mistakes. Of trying painfully, desperately to change, without losing a sense of identity and dissolving into self-loathing and bitterness. Or violence.

Despite the specter of the past, or maybe because of it, there is a fellowship here that I never encountered in any place I’ve lived in the North. A sense of family and level of comfort between the classes and races that I admit took some getting used to.

Not because I didn’t like it, but because I simply didn’t expect it.

In many parts of the South, including my own neighborhood, the poor, middle class and rich still live on the same street. When there’s a big storm, we offer those who lost power a place to hang out. When there’s snow, we help shovel each others driveways. We know each other’s kids. We smile and wave at each other. We don’t lock our doors.

And yes, I mean “we” now. We’ve been here long enough that we can’t say “they” very credibly anymore. This is the place our children call home.

There are Confederate flags tacked in the windows of ramshackle country homes and there’s a proliferation of “Don’t Tread On Me” licence plates. Delusions of grandeur permeate every level of society. There is ignorance, and a simultaneous fear of moving on and being left behind. But southerners don’t have the luxury of placing themselves above it all the way northerners do. The way I used to.

Southerners have had to look one another in the eye for a long time, and deal with a disgraceful past. Clumsily perhaps. Imperfectly. But with a sense of “the local” that Sally Mann inherently understands. Her images of Civil War battlefields depict strips of land that have absorbed blood, death and despair, but remain luxurious. Reclining sensually, and with a weary grin, they tell our story.

All photographs by Sally Mann.