Victoria Dougherty's Blog, page 26

January 14, 2014

Faith’s Little Deaths

My husband, Jack, can be found on any given holiday entertaining my family with his over the top renditions of some of our Slavic tales of woe.

My husband, Jack, can be found on any given holiday entertaining my family with his over the top renditions of some of our Slavic tales of woe.

“Tell me, Jack, what you think is better?” he’ll say in my grandmother’s languorous accent. “To have your legs torn off in gulag and die like dog in ditch like Uncle Vladislavomiroslav? Or be burned alive slowly by laughing German soldier like Cousin Jiroslavomiravova?” Far from being offended, my mother will laugh until tears smear her thick mascara. My grandmother – smoke curling from her bottom lip – will wave her 120 cigarette and say, “Oh, you!”

Or at least she used to, God rest her soul.

It’s easier to laugh about the big tragedies sometimes – the ones cartoonish in their proportions.

I know Jack and I had some of our heartiest, clutching our sides and nearly falling to the floor laughs when our youngest daughter was really, really sick. Especially when we didn’t know if she would live or die. Laughs like that lighten the load and help keep you in love despite the storm raging around you.

Although I’ve laughed like a hyena at things like Biliary Atresia (or Biliary Atrocious, as we started calling it when our daughter was – wrongly, thank God – diagnosed with this condition), and all manner of afflictions and possible syndromes, I still can’t laugh about a nurse I’ll call Tatitana.

She was the nurse who neglected to feed my sick daughter through her feeding tube before heading off to her own cozy lunch. The same nurse who I overheard on the phone telling one of her friends that she thought she was too good for her job. That perhaps medical school was where she belonged.

I remember thinking – You are so wrong. Trust me, as the daughter of not just a good, but a great doctor, medical school is not where you belong, girlfriend. And nursing, on the contrary, is way too good for you.

She performed her job with a boredom that bordered on contempt, and I detested listening to the way she would sigh when she actually had to get up off her bony a** and do something.

To this day, if I saw this nurse on the street my stomach would churn and my fists would clench in rage. I’m sure my face would contort into a mask of scorn and this young woman – who probably wouldn’t even remember me – might say,What’s your problem, lady?.

You might think I’m overreacting. It was just a little vial of baby formula and it’s not like my kid didn’t get fed eventually.

She didn’t starve.

But it was so much more than that. In that moment, under those circumstances, blowing off my daughter’s feeding was not only careless, but cruel. My baby was doped up on morphine, hooked up to all sorts of machines, fighting for her life, and I wasn’t even allowed to hold and comfort her. The only good thing in her whole existence right then was that her little tummy was getting filled on a regular basis and she didn’t have to lie there being both hungry and in pain.

Honestly, in my mind, this nurse was on par with Hitler and Stalin. And that’s saying something. I shudder to think this careless, selfish brat ever went on to medical school. To this day, I hate the idea of her caring for patients in any capacity. I wonder what else she’s forgotten to do, and if she was smart enough to cover it up. I know she thought she was.

In those situations – the BIG situations that come up in life sooner or later – it’s the little deaths that can be hard to have a sense of humor about. The ones that reveal an ugly side of human nature instead of merely a case of bum luck – no matter how bum that luck turns out to be.

My mother, a Czech political refugee, will tell a story over and over again of a little girl she was teaching how to knit after school. I think my mom was about twelve or thirteen and the girl was a couple of years younger.

At that time, my mom didn’t have a lot of friends. Given her political situation, most of the other kids treated her like toxic sludge.

And she loved hanging out with this girl, getting a chance to share a laugh, and treat her like a little sister. Knit one, pearl two.

Turned out the girl was reporting everything my mother said, or didn’t say, to the local authorities for a few coins.

My mom was devastated when she found out, and even though she’s had so many worse things happen to her in her life – she remembers how she felt about this betrayal in technicolor. Not even her abusive first marriage can evoke the kind of sadness that this little friend of hers can arouse to this day.

All of those hours they spent together. And none of them were real.

These are faiths little deaths.

They can happen anywhere, and don’t have to be accompanied by the fog of Nazis and the pollution of Communists. Or the horror and helplessness of watching someone you love suffer.

It may be, in fact, the more ambiguous tragedies that are the most devastating. They can ripple slowly through time like a single raindrop in placid waters.

January 7, 2014

Cold, Cold Birthday

It’s Cold’s birthday today. Okay, not exactly today – I’ve just decided that we’re going to celebrate it today.

It’s Cold’s birthday today. Okay, not exactly today – I’ve just decided that we’re going to celebrate it today.

We are, after all, in the middle of a cold snap.

So, roughly one year ago I posted my very first missive. In honor of that day, which had absolutely nothing else special about it, I thought I’d repost it.

I’ve even added a few more pictures for your enjoyment.

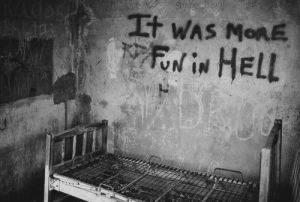

Ponurý: A case for sorrow-loveliness

Years ago, when my husband decided to treat himself to a trip to Auschwitz for his 30th birthday, it raised a lot of eyebrows. I mean, really, why not Vegas? But I got it. His father had recently died, and being of Irish-Jewish decent, he felt a certain draw. I’m especially fond of that particular trip of his to Eastern Europe because we met there – in Prague, at a 300 year-old candle-lit pub just two days before he left for his tour of the Nazi death camp.

Months later, when we were already in love, he told me about his experience.

He said, like many people I know who’ve visited, that the Auschwitz part of the complex wasn’t as compelling as he’d thought it would be. It consisted mostly of plain, brick buildings that could’ve been anything. There was something sanitized about it that he couldn’t quite put his finger on.

The part of the complex that really hit him in the gut was Birkenau. Birkenau is where the “surviving” inmates lived – the ones who weren’t gassed upon arrival. In bunkers built on a barren field. Somewhere behind that field, there’s a small body of water called the Pond of Ashes, and even then, more than sixty years later, it was still a murky gray from the cinders of burnt corpses.

It’s a place of unbearable sorrow beget by unspeakable cruelty and yet my husband told me about standing at that pond and watching a bevy of deer trot by as if they lived in the most glorious place on Earth. This was their home, and they shared it unreservedly with the souls of the departed. He said that if they were able, the deer would’ve smiled at him.

Maybe the deer were indifferent to human suffering and only saw the beauty of their home: The mist in the trees and the cawing of black birds, the comic melody of the Polish language spoken throughout the countryside.

Or maybe they found a tender allure in the vague smell of death that still clings to the landscape even though it’s been decades since a smoke smelling of burnt cashews rose from the chimney stalks. It could be the melody of the visitors’ sobs and not the inhabitants’ chatter that makes this place home.

“Ponurý,” I said, and my husband gave me a quizzical look. He’d never heard of what would become his favorite word.

If you look up Ponurý in an English-Czech dictionary, it will be defined as gaunt, gloomy, dismal and grim, but that’s not its only definition. The way I’ve understood Ponurý is more nuanced. To my Czech friend, Katerina, it means “sorrow-lovely,” implying the beauty in pain, the soulful, life-affirming misery of a stormy day.

“Ah,” my husband said. I’d been able put my finger on something that he’d always recognized, but as an American had no way to define. To Americans, sorrow equals one thing – bad. Ain’t no lovely about it.

Ponurý. I can’t imagine a place like Auschwitz-Birkenau conjuring any other feeling. My experience of the place, I told my husband, wasn’t all that different from his. It involved wrapping my brain around an almost crushing sense of tragedy – yes – but was also filled with tranquility, camaraderie, and even comedy.

I first went to Auschwitz almost two years to the day before my husband visited and had his deer sighting. I was a translator for a British film crew that was making a documentary on the Czech composer Pavel Haas, who died there.

The Prague we’d left was in vivid color, and the train we’d boarded was more muted – flecked with reds and golds, dirty browns and dulled French blues. It was a creaky, communist train – each car still stamped with a prominent red star, though it was 1993. We headed for Poland from Prague on a night that looked a lot like it belonged in Casablanca – the movie, not the Moroccan city. The moon was full, but covered by a thin wisp of clouds that seemed almost like a piece of white muslin wrapped around a fat auntie’s belly. The night was wet cold and our fellow passengers were mostly Polish gypsies, each of whom looked easily ten years older than they were and swore with a gusto I’d never encountered before. They threw the word cunt around as if it were no different than “dude” and could spit out an insult more grotesque than a hard, wet lugie. They lived close to the death camp complex, but appeared to have no interest in it – even if countless of their people, perhaps even members of their own family, had perished there.

I didn’t know my British companions very well. They were BBC journalists with a cameraman and a producer thrown in for good measure. All of them pleasant and smart. I remember doing shots with them in the bar car, but what really stood out about that night – other than the moon – was the way one of the gypsies called me a “stinkin’ cock-sucking cunt of a dead, rotting bitch” for not telling her I was American. She’d been fooled by my then flawless Czech and knew she’d missed a big opportunity when the border guard demanded our passports and I whipped out a dark blue little booklet with the United States of America printed in gold on its cover. Had she known, she would’ve hidden her contraband in my suitcase. “They never check the Americans,” she told me. And it’s true – half her suitcase was confiscated and they never even peeked in mine. That night, I slept with my money and passport shoved into my underwear like a maxi pad.

The journalists thought that was hilarious.

I figured by the time we stepped off the platform in Oswiecim (as Auschwitz is called in Polish), I would be entering a black and white film. But I didn’t. Even though it was an overcast day that saw some drizzle in the afternoon, the air was refreshing, and the death camp complex clean and unassuming. I remember someone had written into the dust on one of the sleeping bunks, “Let he who has never discriminated cast the first stone.” I thought – big difference between discriminate and exterminate, buddy – whoever you are. And that’s when I saw it – my equivalent of the deer by the ash pond. Beyond the fence that encloses the complex was a cluster of small houses. I watched a woman in a housedress amble outside carrying a bundle of wet dish rags. One by one, she hung them on a clothes line. I heard a voice in the distance and the woman waved – a neighbor had come home. She hardly seemed to notice us and we couldn’t have been more than 50 feet away.

“How can anyone live here?” someone said from behind me. Maybe it was the camera man. If I’d known then about the deer, I would’ve told him. I might have said something as simple as, It’s their home. Or, if he’d seemed eager to listen, and I was willing to talk, I might’ve told him about Ponurý, and the counter-intuitive enchantment it can cast over an unsuspecting soul.

Thanks so much for reading. It’s been a great year and I love hearing from all of you.