Pete Sutton's Blog, page 25

April 7, 2016

Review - This Census-Taker by China Mieville

China Mieville returns with yet another different book. This one a novella. It is extraordinary (being both remarkable AND unusual)

The narrator is less than reliable, in identity, in time, in tense, in age...

A boy ran down a hill path screaming. The boy was I ... He was nine years old, I think, and this was the fastest he'd ever run, and he stumbled and careered and it seemed many times as if he would fall into the rocks and gorse that surrounded the footpath, but I kept my feet and descended into the shadow of my hill.

This uncertainty in perception runs through the book. It opens with the boy telling the people in the village that his mother has killed his father, or was it that his father killed his mother? The narrative is built upon shifting sand and with each page Mieville poses a new question. But then answers each with ambiguity. This could, in lesser hands, be terribly unsatisfying but Mieville pulls it off with a flourish. It is all misdirection, all illusion, none of it is misdirection, none of it is illusion.

Why 'this' census taker? Who are the census takers and what are they taking censuses for? There are hints and prompts for supposition but there are no easy answers. I expect that this is the type of book that you have to read several times to fully experience, and that is either a masterpiece or not worth the effort - depending upon your point of view.

With well-written books you get the impression that the book is only the visible part of a larger body, like an iceberg. With this book Mieville has obfuscated the visible part and you are left with glimpses of a much larger world, through a foggy lens. It is a masterfully crafted puzzle box that ends on an acrostic. The meaning of which is just another hint, another question, another mist-shrouded viewpoint that makes you wonder, makes you question, makes you want to read it again.

A boy ran down a hill path screaming...

Overall - Mieville fans will have scooped this up, devoured it, left satisfied and yet wanting more. Non-Mieville fans can't really exist, can they?

Published on April 07, 2016 00:47

April 3, 2016

Fight like a girl - the launch

Yesterday, in Bristol, on a quiet sunny afternoon, some fantasy elements descended upon the Hatchett pub (one of three pubs that claims to be the oldest in Bristol) in the centre.

It was billed as a book launch, but it was no such thing. It was a min-con hosted by the inimitable Roz Clarke and Jo Hall

There were readings - awesome ones from Lou Morgan,

Danie Ware

and Sophie E Tallis

There was a panel featuring Joanne Hall, KT Davies, Gaie Sebold and Dolly Garland mistressfully (masterfully would be the wrong word to use for this launch!) handled by Cheryl Morgan

And if that wasn't amazing enough there was a fantastic demonstration of martial prowess by Juliet McKenna

and Fran Terminiello

ably helped by her friend Lizzie

Oh and there was food, and drink, and fans, and other local writers (too many to mention, they know who they are), and chatting about books, and the buying of books and old friends and new.

In short it was a fabulous event that sets the bar very high as far as book launches goes (gulp - got to organise one for A Tiding of Magpies!)

The Bristol Book Blog review is here : and I hope to entice some of these brilliant writers to the blog to talk about, well whatever they want to really, but hoping for tales of swords and representation and discoverability.

A big shout out to Sammy Smith who really deserved to be there, but fate intervened. Kristell Ink have done a top job on the book. The cover is even more fantastic than we imagined (get a copy and put it under a blacklight to see why), the quality of the stories is very high and it is a very nice addition to the bookshelf (especially signed by many of the contributors - with others to be stalked and forced to scribble in it at a future date!)

It was billed as a book launch, but it was no such thing. It was a min-con hosted by the inimitable Roz Clarke and Jo Hall

There were readings - awesome ones from Lou Morgan,

Danie Ware

and Sophie E Tallis

There was a panel featuring Joanne Hall, KT Davies, Gaie Sebold and Dolly Garland mistressfully (masterfully would be the wrong word to use for this launch!) handled by Cheryl Morgan

And if that wasn't amazing enough there was a fantastic demonstration of martial prowess by Juliet McKenna

and Fran Terminiello

ably helped by her friend Lizzie

Oh and there was food, and drink, and fans, and other local writers (too many to mention, they know who they are), and chatting about books, and the buying of books and old friends and new.

In short it was a fabulous event that sets the bar very high as far as book launches goes (gulp - got to organise one for A Tiding of Magpies!)

The Bristol Book Blog review is here : and I hope to entice some of these brilliant writers to the blog to talk about, well whatever they want to really, but hoping for tales of swords and representation and discoverability.

A big shout out to Sammy Smith who really deserved to be there, but fate intervened. Kristell Ink have done a top job on the book. The cover is even more fantastic than we imagined (get a copy and put it under a blacklight to see why), the quality of the stories is very high and it is a very nice addition to the bookshelf (especially signed by many of the contributors - with others to be stalked and forced to scribble in it at a future date!)

Published on April 03, 2016 04:42

April 1, 2016

Guest Post - David Tallerman on short story compilations...

David Tallerman is the author of the novel Giant Thief - described by Fantasy Faction as "one of the finest débuts of 2012" - and its sequels Crown Thief and Prince Thief, all published through Angry Robot. He has also written the Markosia graphic novel Endangered Weapon B: Mechanimal Science, the Tor.com novella Patchwerk, and around a hundred short stories, comic and film scripts, poems, and countless reviews and articles. Many of these have been released in one form or another, and others are forthcoming over the next few months. This post is about the recently released The Sign in the Moonlight and Other Stories,

You'd think that putting together a short story collection would be relatively straightforward.

Well, I did anyway. Three years ago it seemed a simple enough prospect, and one I already had a head start on. I'd written a ton of short fiction - maybe sixty stories at that point - and it so happened that a chunk of those were thematically and tonally similar enough that they'd sit nicely together in one book. I'd had a lengthy phase of being under the spell of a bunch of writers who tend to get lumped together, folks like Lovecraft, Machen, Poe and Blackwood, and of trying to unpick just what it was I loved about their work. Yet at the same time I'd been struggling to find my own voice as a writer, and the result was a number of tales with an interesting, somewhat tense relationship with those great innovators of horror and fantasy. How hard could it be to throw them all together into one book and get it out there?

But I guess I've answered my own question. Because if everything had proved that straightforward, it's a safe bet I wouldn't be writing this three years later.

Having decided I had the makings of a collection, I set about figuring out the best means of getting it into the world. It happened that around the same time, one of the stories I had in mind, novelette The Way of the Leaves, won a chapbook competition being run by a British small press, and it occurred to me that my proposed book was within their wheelhouse. I approached the owner and he seemed interested. I told myself that was the job more or less done.

Sadly the actual experience would prove to be a nightmare worthy of anything I'd written: an endless-seeming parade of ignored e-mails, excuses, missed deadlines and prevarication that dragged on for more than two years. But in the meantime, I was still working to improve the collection that would eventually become The Sign in the Moonlight and Other Stories. I'd long been considering projects to work on with my artist friend Duncan Kay, and eventually I asked if he'd be up for illustrating a few short stories. Duncan, whose tastes in dark fiction run close to my own, was entirely up for it, and over the following months went on to produce some astonishing pieces.

In fact, in that and many other ways, the delays proved a blessing. If nothing else, they made me think hard about what I had and what I needed. Many stories got redrafted during that time, and were greatly improved for it. A few new pieces were added, including my personal favourite. Almost my first project when I began to write full time at the tail end of 2013 was to put together a novelette, The War of the Rats, to shore up the collection, giving it a second significantly longer piece. It also occurred to me that an introduction might not be such a bad idea, so I approached one of my absolute favourite fantasy authors, Adrian Tchaikovsky, who was good enough to agree to help.

In short, the book just kept getting better. So it was that when I finally parted ways with the publisher I'd originally signed on with and approached Canadian outfit Digital Fiction Publishing - with whom there would prove to be no ignored e-mails, excuses, missed deadlines or prevarication at all! - we both felt that the project was something a little special.

Now that The Sign in the Moonlight is finally out there, I can see that there were two huge challenges in putting my first short fiction collection together. The first seems obvious in retrospect, but perhaps it took having such an uphill struggle for me to see it: above and beyond the actual stories themselves, a great deal of energy went into making the book the best it could be, so that it might have a hope of standing out in a crowded marketplace. As for the second, that came down to finding a publisher who was as enthusiastic about and committed to the project as I was - which, thinking about it, is perhaps the hardest part of any book. I count myself lucky that both things came together in the end, and I couldn't be prouder of the results.

The GRSBKBLOG review is here :

Published on April 01, 2016 13:10

March 30, 2016

Fight like a girl review & The discoverability challenge

I received this book in return for an honest review. Happy to say I really enjoyed it.

Grimbold Books have called some of the best female genre writers together under a fantastic cover to tell tales of what it actually means to 'fight like a girl'. Of course that has been thrown as an insult by boys of all ages but what would it actually mean?

There are stories here that run a gamut of second worlds, near and far futures. There is a collection of superb female characters, often making tough choices. This is a rich and varied anthology.

As with all anthologies the variety may mean that not all stories hit the right note for all readers but there are no real duffers in here. With stories by the likes of Juliette McKenna, Gaie Sebold, Julia Knight, Lou Morgan and Joanne Hall (amongst other names you may recognise) you know there will be a quality selection.

There are women who are hard as nails, women who have tough choices and women who fight because life has left them no other option.

I was especially taken by Danie Ware's near future apocalyptic story, Unnatural History, in which the setting stood out, it would have slotted quite well into a collection of weird fiction, a particular favourite genre. Gaie Sebold's Fire and Ash takes control of your emotions in a fitting end to the collection. And those tough choices are rarely tougher than in Joanne Hall's Arrested Development

Also worthy of note were Turn of A Wheel by Fran Terminiello and Vocho's Night Out by Julia Knight - neither author I've read before and both I'd like to read more from.

And that brings me to the discoverability challenge. As with the NewCon Press collections I reviewed in January this is a great addition to the shelves as it has a number of female writers new to me, ones I'd like to read more from.

Overall - If you're a genre reader you need this book on your bookshelf

In February my discoverability challenge book was - All the Birds in the Sky by Charlie Jane Anders, but I didn't get on with that one. Too disjointed, not knowing what it wanted to be (is it YA or adult, SF or fantasy, a love story or an apocalyptic tale?)

Published on March 30, 2016 00:56

March 29, 2016

Cover Reveal - A Tiding of Magpies

Very happy to be able to reveal the cover to the forthcoming short story collection

A Tiding of Magpies

Also very proud to announce that Paul Cornell will be writing the Foreword. Paul is the author of the rather fabulous Shadow Police series, as well as numerous other books and comics and I'm very honoured that he has agreed to write this for the book.

I like the very clean look of the book and its striking black and white design. The next announcement will be of the pre-order and launch dates I expect and I'll be working on the launch.

Also very proud to announce that Paul Cornell will be writing the Foreword. Paul is the author of the rather fabulous Shadow Police series, as well as numerous other books and comics and I'm very honoured that he has agreed to write this for the book.

I like the very clean look of the book and its striking black and white design. The next announcement will be of the pre-order and launch dates I expect and I'll be working on the launch.

Published on March 29, 2016 01:38

March 23, 2016

Guest Blog from A.A. Abbott

AA Abbott is a crime thriller writer, author of The Bride’s Trail and other “racy and pacy” fiction. Read a fuller account of her jury service at http://aaabbott.co.uk/2015/10/whats-it-like-to-sit-on-a-jury-im-about-to-find-out/

You can follow AA Abbott on Twitter , Facebook and LinkedIn , or sign up for newsletters to receive a free ebook!

Have you ever wondered what Jury service is really like? Well A. A. Abbott is here to tell you all about it

WHAT JURY SERVICE IS REALLY LIKE…

This is a true story that never made the news – it wasn’t deemed important enough. Yet, in merely thirty seconds, a handful of young lives changed for the worse. How do I know? I sat on the jury that heard the case. Read on and find out more…

It starts for me when I get the letter telling me I’ve been selected for jury service. Although a crime thriller writer, I dip in and out of the world of big business too, taking contract work for a few months every year. I’m just finishing one contract and have had a meeting to pitch for another. It’s a busy time of year for my prospective employers, and I imagine they’ll look for someone else to fill the contract role. Luckily, it seems they don’t have a problem as long as I’m only away for the average duration of two weeks.

On my first morning, I turn up at the Crown Court, joining the hundred or so souls sitting in the jury lounge. Half of us are new boys and girls like me. The old hands are laughing and chatting with each other, making drinks in the spacious kitchen. We newbies sit in silence, typing on smartphones or reading newspapers. Phones, tablets and laptops can be used everywhere except in the courtroom itself. The wifi is not free, however. Complaints about this are posted in a comments box.

[image error](Picture from The Times)

We’re given a welcome talk. This is an important civic duty. If selected to try a case, we must only talk about the case when the entire jury is present; otherwise we cannot even talk amongst ourselves, and definitely not with anyone else. We must not speak of it on social media. We must not research it online. Then we see a DVD, where a blonde woman so carefully made up she could be animatronic tells us the same things. She shows us the layout of a court. She explains that the court usher, clerk, judge and barristers wear black robes. The judge and barristers wear wigs too.

[image error](Picture The Guardian)

We’re told the computer will pick batches of sixteen to go to each court, then the clerk will pick twelve to stay there. Each selection is random.

That’s how I end up sitting with eleven strangers on the jury benches, to one side of the court. There’s a ledge in front for paper and pens. We may keep the notes for the duration of the trial but they are then to be destroyed.

The judge has a youthful face beneath his grey wig and the barristers seem a similar age, but the three defendants are younger still. Barely in their twenties, Jake Goodman, George Drummond and Lloyd Wick look hopefully from the dock, knowing their fate lies in our hands. Each is represented by his own barrister. The prosecution barrister is supported throughout by the policeman who investigated the case, DC Hampson. The jury is asked if we know any of them, and also various witnesses whose names are given to us. We don’t, so we’re all eligible to serve.

[image error]

The clerk calls us to our seats, one by one. I had expected objections from the advocates - the defendants are all black or mixed race, while the jury is solidly white – but there are none.Mr Goodman, Mr Drummond and Mr Wick sit silently, side by side in the dock, bookended by two security guards. They seem engaged right at the start, then slip into glassy-eyed boredom.

Before the court may begin to hear the case, all the jurors must take an oath. This is passed around on a sheet of paper, along with the bible. We swear before Almighty God that we will try the case fairly. Jurors may simply affirm they will do this without any mention of a higher power if they’re not religious. One of our number stumbles over the words, possibly through dyslexia.

We are given a written list of the charges against the defendants. They are accused of drugs and violent offences. The prosecution barrister then outlines the case. Four young men were offered drugs outside a popular bar. When they declined to buy any, they were followed into the bar and allegedly beaten up by the defendants.

[image error]

The prosecution counsel, Mr Bastow, is put in charge of a DVD player. It takes him a long time to get the hang of it and he’s ribbed by the other legal professionals. Joking aside, the method of address is very formal. The judge is addressed as your honour and referred to as his honour. The barristers are Mr this and Miss that, and my learned friend. The defendants are addressed, and referred to, as Mr Goodman etc.

The first piece of evidence is blurry CCTV footage showing a group storming into the bar and starting a fight. It’s just about possible to tell the attackers and victims are male, but the quality is too poor to identify anyone. The brawl itself is over in thirty seconds.

Our CCTV show finishes in time for a lunch break. We always have at least an hour, sometimes more. The court allows us the princely sum of £5.71 for a meal. This can be reclaimed without a receipt, so many jurors bring sandwiches. In a small way, this helps to make up the difference between the miserly lost earnings allowances and the amount we might actually have made at work.After lunch, Bastow wheels out a couple of witnesses. We end up hearing from all four victims, which takes up the rest of the first day and most of the second.

Three of the victims remember very little. They’d been drunk and concussed; their injuries were serious enough to warrant stitches and staples.

[image error]

“I vaguely recall an argument. The next thing I knew, I woke up amongst blood, police and paramedics,” one says.

The Crown’s star witness is the fourth member of the group, Dan Hart. He was pulled away from the fight and is confident he observed all of the defendants there, picking them out in an identification parade several months later. Gloves are now off as far as the defence counsel are concerned. Before, they’ve been meek as lambs with no questions for Hart’s friends; now they’re wolves going for Hart’s jugular.

Mr Smith represents Jake Goodman, who is supposed to have offered Hart cocaine. “You say he had a distinctive mark on his face,” he tells Hart. “Mr Goodman has no such mark.”

Jake Goodman’s unblemished face beams from the dock.

Miss Shah represents George Drummond. She starts by talking like a schoolmistress, saying she assumes Dan Hart has never given evidence in a court before. He agrees he has not. She says, well it is a serious matter, and again he agrees.

Her focus is to prove his memory is wrong. Did he really only have four pints, as he said, she muses. He would have been over the limit to drive.

Hart is composed. “We began early and I drank over the course of eight hours,” he points out, adding, “But no, I wouldn’t have driven.”

She is hectoring now. “But if you had six pints, your concentration would be impaired. You can’t be certain you identified the attackers correctly.”

“It was only four or five,” he says, “and my memory is clear.” All of the attackers had leaped off the page to him in the ID parade, he tells her.

“But that was months later. I put it to you that you cannot be sure.”

On the contrary, he says, “I am sure.”

Miss Barry, for Lloyd Wick, is similarly snarly. Her lip curls. She forces him to admit a minor memory lapse, then presses her advantage home. “What else are you mistaken about? How can you be certain you saw the defendants that night? I put it to you that your identification could be incorrect.”

The jury retires for a late, but extended lunch break, as there will be more legal discussions. Stepping outside in the sunshine, I see George Drummond walking towards me. We don’t make eye contact or smile. He looks somehow distant, possibly bored but more likely stressed. Mostly, the defendants are looking down while in the dock, so I guess they’re playing video games.

Once we return to court, we’re not there for long.

“We are now going to see agreed statements,” the judge tells us. “They’re statements in writing of evidence on which everyone has agreed. They’ll be typed up tonight, so come back tomorrow morning for 10.30am.”

The next day, having rushed through court security (our bags are checked and we’re frisked every time we enter the building), I discover the trial’s starting even later. Jurors for other courts are shepherded away. It’s nearly twelve when it’s announced that we’re on. I close down my laptop and both my mobile phones as we walk to the courtroom.

[image error]

Today’s proceedings start with agreed facts, the written statements on which both prosecution and defence agree. Dramatically, Jake Goodman admits to being with the attackers in the bar. It is acknowledged that he and George Drummond are friends. All three defendants have been convicted of multiple violent offences, although in Drummond’s case, the convictions are several years old. Once Bastow has read all the agreed facts out, it’s lunchtime again.

For a change, we manage to start the afternoon on time. It’s just as well, as more drama unfolds. The next witness to take the stand is DC Hampson, a middle-aged man with a cynical expression. He is the first to swear on the bible when called to the witness box. The others have merely affirmed they will not lie. He tells us more about identity parades, which now take place in video rooms. The witnesses are shown photos of the suspects within batches of images drawn from a huge computer database. The computer deliberately seeks out similar faces to that of the suspect, and the suspect’s legal advisers vet the images and may object to them before they’re shown to witnesses. The process is known as VIPER: Video Identification Parade Electronic Recording.

[image error]

“We no longer drag members of the public off the streets,” the judge smirks.

All three defence counsel cross-examine Hampson. Smith has little to say, but Misses Shah and Barry have plenty. Miss Shah points out that George Drummond has an alibi for the night. He was with his friends Bradford Dean and Nathan Judd all evening. Hampson had their names and phone numbers two weeks before the trial. Why didn’t he phone them, she wants to know?

Hampson admits it would be normal procedure, and he can’t recall why he didn’t do it.

Hampson is the last prosecution witness, and now the defendants may have their say. Messrs Goodman and Wick decline to do so, but Drummond is keen to speak. He affirms that he will tell the truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth.

George Drummond is tall and broad-shouldered. The men seen on CCTV appear slimmer, and I wonder at the identification evidence.

Miss Shah is now the soul of gentleness as she sympathetically draws out his story. His previous offences took place when he was a boy. He was in care and found it hard to settle; he simply lashed out.

“I know that doesn’t excuse my behaviour,” Drummond says. “But I’m a different person now. I’ve turned my life round.” After a period of homelessness, he’s secured a college place and somewhere to live.

Miss Shah asks him about the alibi. Drummond had been through his social media messages and realised he’d made arrangements to see Bradford and Nathan that night. We are given screenshots.“Can you translate for us?” Miss Shah asks.

Drummond grins while Goodman and Wick fall about laughing. Patiently, Drummond talks her through the messages. He asserts that he spent the evening with his friends and stayed overnight with them.

Now it’s time for Bastow to cross-examine and he lets rip. “You have a temper don’t you, Mr Drummond?”

“No more than anyone else,” Drummond says. “I know I did wrong when I was younger. I was under pressure then, in care or homeless. I’m a different person now.”

“You lose it when you don’t get your own way.”

“I don’t do that now,” Drummond repeats.

Bastow is deeply suspicious that the alibis were so late in being forthcoming. He says it took Drummond a long time to persuade his friends to lie to him. Why weren’t they mentioned before? Drummond says his solicitor advised him to say nothing in police interviews.

“Mr Goodman is your friend too, is he not?” Bastow asks.

Drummond says yes, but not like Dean and Nathan.

“Not someone who would lie for you?” Bastow suggests.

“No.” Poor Drummond is damned however he answers that question.

“And Mr Wick? Do you know him?”

“I know OF him,” Drummond says. “I mean, he’s a friend of a friend. But I don’t know him.”Bastow asks if Drummond has spoken with his alibi witnesses. He claims he hasn’t, saying they were both busy and Bradford had no phone. The judge points out that Drummond has provided a phone number for Bradford. Drummond says it didn’t work when he tried to ring it.

At 4.30pm, with Bastow still raring to go for Drummond’s throat, the judge calls a halt. When the court resumes on the fourth morning, Bastow begins by quizzing Drummond about Bradford Dean’s mobile phone He’s trying to goad Drummond into either losing his temper or admitting he has one. Drummond remains calm.

Bastow eventually gives up. “I have no further questions,” he says.

Then Bradford Dean, Drummond’s childhood friend, takes the stand. He’s a credible witness, of good character, who robustly denies Bastow’s suggestion that he’s lying. The problem is, that although he knows he made arrangements to see Drummond that evening, he has no proof that they actually met. When Bastow asks what he did every other day that week, he can’t remember. The mystery of his mobile phone is solved, though. Under Miss Shah’s examination, it turns out that it stopped working a month ago but Dean didn’t tell anyone.

There are no more witnesses, so Bastow sums up the prosecution’s case. He says Goodman and Wick must have something to hide, because they haven’t taken the stand. Drummond on the other hand is confident, and therefore must be the confident leader of the attackers. All three are violent, says Bastow. We should not doubt Hart’s evidence because he correctly identified Goodman, who admitted he was there. It’s no coincidence that the other two men Hart identified, Drummond and Wick, also have a history of violence and know each other and Goodman. “Fancy that,” Bastow says drily.

We spend the rest of the day hearing from the defence counsel. Smith, who has asked very few questions of the witnesses, gives the jury plenty of eye contact as he tells them they need to be sure to convict Goodman. And they can’t be. Goodman doesn’t have any distinguishing marks on his face, so couldn’t have been the man who tried to sell drugs.

[image error]

Smith is adamant that if we watch the CCTV footage, we won’t see Goodman hitting anyone. “He was a peacemaker. Watch the DVD again,” Smith urges. Alas, when we do, we see Jake Goodman in the middle of the brawl.

Miss Shah is worthy of an Oscar, looking wide-eyed at the jury. She starts by quoting Little Women on important words. She tells us we’ve heard the most important words all along from Drummond: ”I was not there.” The CCTV images could be any one of hundreds of men in the city with a similar physical appearance. Dan Hart hardly saw him and could be wrong. Drummond’s offences took place many years ago, a long time for a young man of his age. We must take this seriously as we have the power to affect the course of his life. She hopes we’ll react to his courage and consistency and acquit him. It has been a privilege to know him, she says.

Miss Barry acknowledges her client is an unpleasant man, but says he wasn’t there, he didn’t do it, Dan Hart was too drunk and had too little time to identify him and the CCTV certainly doesn’t.It remains for the judge to sum up, and that takes us into Day Five. He explains the law on joint enterprise. If two or more people act together with the same purpose, it doesn’t matter who did what – they are all jointly guilty of the crimes committed as a result. The actions can be planned or can happen on the spur of the moment. It is the joint enterprise doctrine that means Goodman, Drummond and Wick are each charged with violent attacks.

We may take silence in court into account, although Wick and Goodman are perfectly entitled to decline to take the stand, effectively saying to the prosecution, “You prove my guilt.” The burden of proof at all times rests with the prosecution. He reminds us that Drummond had elected to give his account in court and has been cross-examined at length, as has his witness, Bradford Dean.

He is dismissive of Drummond’s alibi, saying we are entitled to wonder why it was not forthcoming earlier. DC Hampson should not be criticised for failing to contact the alibi witnesses at such a late stage. Even if we decide Drummond’s alibi is false, however, we should be aware that individuals falsify alibis for a number of reasons. For example, they may have been somewhere else that they wouldn’t want anyone to know about. If we choose to ignore the alibi, we must still convict Drummond only if the prosecution has proved his guilt otherwise.

Although Lloyd Wick answered police questions, he did not give an alibi. He just said he wasn’t there. “That is not an alibi,” the judge says. “It is an assertion.”

The CCTV evidence is of insufficient quality to identify anyone by itself, but it may be used to support Daniel Hart’s identifications. We may similarly use it to exclude suspects, bearing in mind its poor quality, the judge says.

The jury now retires to the jury room, where we will stay until we can reach a unanimous verdict on all charges.

The law does not allow me to say anything about the jury’s discussions, but suffice to say that we reach unanimous verdicts. We agree that Drummond is innocent, whilst Goodman and Wick are guilty of violence only, not of offering to sell drugs.

As soon as we are seated on the benches again, the judge directs the defendants to stand. He then asks the foreman of the jury to stand too. Our elected foreman rises to his feet.

“Have you reached verdicts on all counts put before you?” The judge asks.

“We have,” he replies.

“And are you all agreed on them?”

“We are.”

The clerk to the court reads out each charge in turn. One by one, our foreman gives the verdict.“Thank you,” the judge says. He looks at the dock. “Mr Drummond, you are free to go.”

Young Drummond looks stunned. He does not smile. For a second, he glances sympathetically at another defendant – not his friend, Goodman, but his acquaintance, Wick. I suppose Goodman’s case was dead in the water as soon as he admitted he was in the bar that night. Then Drummond walks from the dock a free man, clutching a large plastic carrier bag. “Thank you,” he says gravely to the judge and jury.

That evening, I stroll through the city, looking at the Friday night revellers with a lump in my throat. I give thanks to God that I have my life and my liberty.

But all that is several hours away. Right now, Smith anxiously asks the judge to sentence Goodman quickly, as he has been on remand for a long time. The judge agrees speed is desirable, and offers a slot next week.

That puts Miss Barry under pressure, as the judge wants to sentence Goodman and Wick together, and she needs to get pre-sentencing reports for Wick. “I’m not sure I can do it in time,” she says.He gives her short shrift, but at least allows Wick to walk free on bail, as his record is nothing like as serious as Goodman’s. The hapless Goodman is returned to prison. “And now, members of the jury, let me thank you,” he says. “It’s not easy to make those kind of decisions. Between you and me, and this is just a personal view, even if you discounted Mr Drummond’s alibi, your decision to acquit him was correct based on the evidence presented to you.”

So we head out into the sunshine. I walk away from the drama of the week, past the bar where several young men had that fateful argument, back to my beautiful quiet life.

Published on March 23, 2016 07:35

March 22, 2016

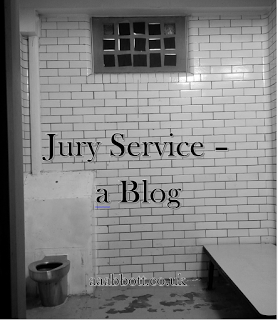

Guest Post from Brian Staveley

After teaching literature, philosophy, history, and religion for more than a decade, Brian began writing epic fantasy. His first book, The Emperor’s Blades, the start of his series, Chronicle of the Unhewn Throne, won the David Gemmell Morningstar Award, the Reddit Stabby for best debut, and scored semi-finalist spots in the Goodreads Choice Awards in two categories: epic fantasy and debut. The second book in the trilogy, The Providence of Fire, was also a Goodreads Choice semi-finalist. The concluding volume of the trilogy, The Last Mortal Bond, is available for from TOR UK on 24 March.

Brian lives on a steep dirt road in the mountains of southern Vermont, where he divides his time between fathering, writing, husbanding, splitting wood, skiing, and adventuring, not necessarily in that order. He can be found on Twitter at @brianstaveley, Facebook as brianstaveley, and Google+ as Brian Staveley. His blog, On the Writing of Epic Fantasy, can be found at: bstaveley.wordpress.com.

Brian dropped by to talk about reading:

Read or Die

One of the cruel ironies of the writing life is that it involves so little reading. I’m sure there are writers out there who manage to churn through a few novels a week while working on their own manuscripts, but I am not one of them. Some days, when I close the computer, I would rather do anything—sled through the fire pit, sort through my underwear drawer retiring the old pairs, sort through a complete stranger’s underwear drawer—than look at and think about words. Reading during the day, on the other hand, feels self-indulgent, almost lazy. Reading, after all, is recreation. The day isn’t for recreating; it’s for writing my own damn books.

This line of thinking, of course, is a mistake. You can’t write without reading any more than you can breathe in without breathing out. When I spend too much time on my own work, I find my pages growing stale, rehearsed, repetitive. I need all these other voices in my head, voices working in my own genre and others far afield from it. Without the constant infusion of fresh thoughts, characters, worlds, words, I’d end up writing the same story over and over in marginally different ways.

This line of thinking, of course, is a mistake. You can’t write without reading any more than you can breathe in without breathing out. When I spend too much time on my own work, I find my pages growing stale, rehearsed, repetitive. I need all these other voices in my head, voices working in my own genre and others far afield from it. Without the constant infusion of fresh thoughts, characters, worlds, words, I’d end up writing the same story over and over in marginally different ways.

Sometimes what I get from reading is as simple as a word. Reading has a great way of shifting forgotten or neglected language into the working vocabulary. Farrago, for instance. I’d forgotten all about farrago! Or actinic, which I used once because I couldn’t resist, even though I worry it might be a little anachronistic. The danger here, of course, is that you can rediscover a new word and get carried away. Just the other day, a good friend of mine, after reading half a dozen chapters of my new manuscript, sent me this email: “You are only allowed one ‘lambent’ per book... the current count is 3, putting you at an estimated 9 by the time you are done. Similarly, you've already used up your ‘flensed,’ so don't try it again.” I’m told I’m a little too fond of “ambit” as well, but I have friends for this very purpose: someone has to tell you when you’re getting too frisky with the English language.

Reading also pushes the boundaries of my thinking about what’s formally possible or desirable. Of course, I’m well aware that some things—like sliding a green bean all the way into one’s sinuses—may be possible without being desirable, but the best writers have a way of eliding the boundary between the two. Joe Abercrombie, for instance, has a chapter in The Heroes, a tour-de-force that follows the battle through the logic of the killings themselves; when a point-of-view character is killed, the POV shifts to his killer, until that person is killed, when it shifts to the next killer. I wouldn’t have imagined the approach could work—it seems too disjointed—but the pell-mell, unpredictable whipsaw pull of the thing is the whole the point.

Or take N.K. Jemisin’s novel, The Fifth Season. She writes a good chunk of this in the second person, a point of view I used to think was appropriate only for Choose Your Own Adventure novels or uncomfortable introductions to speeches: “You, Charles, chose a different path from the rest of us…” Jemisin’s handling of it proved me completely wrong, opening up an entire stylistic avenue for future exploration.

The disappointing books can be just as instructive as the brilliant. It might seem like an odd educational method—aspiring chefs probably don’t have much to learn from my recipe for jello-shots; bluegrass players might do best to steer well clear of my three-year-old son plinking on the banjo; budding cartographers stand to learn nothing from my wife’s sense of direction, a sense that insists on rendering the three-dimensional topography of the world in a single dimension, a line that somehow connects Vermont, Boston, New York, and Florida, and Greece—and yet, I find I learn a lot from the books I don’t really enjoy, the ones I put down.

Whenever I give up on a book, I ask myself why. Occasionally, there’s an overt problem: miserable prose, piles of obvious factual errors. Much more often, however, I abandon a book because something is lacking. It can take a while to figure out what that something is. Just last week, for instance, I started a fantasy novel that had a great premise, engaging characters, an unusual setting, and an interesting mystery. Still, curmudgeonly asshole that I am, I found myself bouncing off of it. I read on a few more chapters before realizing my problem: I couldn’t see anything. I had no idea what anything looked like in this vast, imaginative world, no sense of the colors or contours, no conception of the spatial relation between anything described, on either a large scale or small. Whenever I have an experience like this, it’s a reminder to go back to my own work and to make sure that the things I see inside my head are actually there on the page. “Oh yeah,” I’ll realize. “I forgot to mention the fact that she has a sword sticking through her liver.”

In the end, most importantly, reading reminds me of the joy of stories. I might feel more like cracking a beer than a book after my son is in bed at the end of the day, but the beauty of life is that I can do both, and almost inevitably, after the first few pages a new book begins to work that ancient spell, the one where you slip from this world into another, find yourself lost, and delighted to be so. Any writer who forgets that feeling might as well get out of the game.

Thanks to Brian for his interesting post! Go check out his books - https://bstaveley.wordpress.com/

Brian lives on a steep dirt road in the mountains of southern Vermont, where he divides his time between fathering, writing, husbanding, splitting wood, skiing, and adventuring, not necessarily in that order. He can be found on Twitter at @brianstaveley, Facebook as brianstaveley, and Google+ as Brian Staveley. His blog, On the Writing of Epic Fantasy, can be found at: bstaveley.wordpress.com.

Brian dropped by to talk about reading:

Read or Die

One of the cruel ironies of the writing life is that it involves so little reading. I’m sure there are writers out there who manage to churn through a few novels a week while working on their own manuscripts, but I am not one of them. Some days, when I close the computer, I would rather do anything—sled through the fire pit, sort through my underwear drawer retiring the old pairs, sort through a complete stranger’s underwear drawer—than look at and think about words. Reading during the day, on the other hand, feels self-indulgent, almost lazy. Reading, after all, is recreation. The day isn’t for recreating; it’s for writing my own damn books.

This line of thinking, of course, is a mistake. You can’t write without reading any more than you can breathe in without breathing out. When I spend too much time on my own work, I find my pages growing stale, rehearsed, repetitive. I need all these other voices in my head, voices working in my own genre and others far afield from it. Without the constant infusion of fresh thoughts, characters, worlds, words, I’d end up writing the same story over and over in marginally different ways.

This line of thinking, of course, is a mistake. You can’t write without reading any more than you can breathe in without breathing out. When I spend too much time on my own work, I find my pages growing stale, rehearsed, repetitive. I need all these other voices in my head, voices working in my own genre and others far afield from it. Without the constant infusion of fresh thoughts, characters, worlds, words, I’d end up writing the same story over and over in marginally different ways. Sometimes what I get from reading is as simple as a word. Reading has a great way of shifting forgotten or neglected language into the working vocabulary. Farrago, for instance. I’d forgotten all about farrago! Or actinic, which I used once because I couldn’t resist, even though I worry it might be a little anachronistic. The danger here, of course, is that you can rediscover a new word and get carried away. Just the other day, a good friend of mine, after reading half a dozen chapters of my new manuscript, sent me this email: “You are only allowed one ‘lambent’ per book... the current count is 3, putting you at an estimated 9 by the time you are done. Similarly, you've already used up your ‘flensed,’ so don't try it again.” I’m told I’m a little too fond of “ambit” as well, but I have friends for this very purpose: someone has to tell you when you’re getting too frisky with the English language.

Reading also pushes the boundaries of my thinking about what’s formally possible or desirable. Of course, I’m well aware that some things—like sliding a green bean all the way into one’s sinuses—may be possible without being desirable, but the best writers have a way of eliding the boundary between the two. Joe Abercrombie, for instance, has a chapter in The Heroes, a tour-de-force that follows the battle through the logic of the killings themselves; when a point-of-view character is killed, the POV shifts to his killer, until that person is killed, when it shifts to the next killer. I wouldn’t have imagined the approach could work—it seems too disjointed—but the pell-mell, unpredictable whipsaw pull of the thing is the whole the point.

Or take N.K. Jemisin’s novel, The Fifth Season. She writes a good chunk of this in the second person, a point of view I used to think was appropriate only for Choose Your Own Adventure novels or uncomfortable introductions to speeches: “You, Charles, chose a different path from the rest of us…” Jemisin’s handling of it proved me completely wrong, opening up an entire stylistic avenue for future exploration.

The disappointing books can be just as instructive as the brilliant. It might seem like an odd educational method—aspiring chefs probably don’t have much to learn from my recipe for jello-shots; bluegrass players might do best to steer well clear of my three-year-old son plinking on the banjo; budding cartographers stand to learn nothing from my wife’s sense of direction, a sense that insists on rendering the three-dimensional topography of the world in a single dimension, a line that somehow connects Vermont, Boston, New York, and Florida, and Greece—and yet, I find I learn a lot from the books I don’t really enjoy, the ones I put down.

Whenever I give up on a book, I ask myself why. Occasionally, there’s an overt problem: miserable prose, piles of obvious factual errors. Much more often, however, I abandon a book because something is lacking. It can take a while to figure out what that something is. Just last week, for instance, I started a fantasy novel that had a great premise, engaging characters, an unusual setting, and an interesting mystery. Still, curmudgeonly asshole that I am, I found myself bouncing off of it. I read on a few more chapters before realizing my problem: I couldn’t see anything. I had no idea what anything looked like in this vast, imaginative world, no sense of the colors or contours, no conception of the spatial relation between anything described, on either a large scale or small. Whenever I have an experience like this, it’s a reminder to go back to my own work and to make sure that the things I see inside my head are actually there on the page. “Oh yeah,” I’ll realize. “I forgot to mention the fact that she has a sword sticking through her liver.”

In the end, most importantly, reading reminds me of the joy of stories. I might feel more like cracking a beer than a book after my son is in bed at the end of the day, but the beauty of life is that I can do both, and almost inevitably, after the first few pages a new book begins to work that ancient spell, the one where you slip from this world into another, find yourself lost, and delighted to be so. Any writer who forgets that feeling might as well get out of the game.

Thanks to Brian for his interesting post! Go check out his books - https://bstaveley.wordpress.com/

Published on March 22, 2016 13:22

March 14, 2016

Interview with Clifford Beale

Clifford Beal is a former international journalist and the author of Gideon’s Angel and The Raven’s Banquet by Solaris Books. Following a swashbuckling past where he trained in 16th -17th century rapier combat, he now leads a more sedentary life but daydreams of returning to fighting trim. When not imbibing endless mugs of tea and writing, he can usually be found imbibing endless mugs of tea and reading. Originally from Providence, Rhode Island, he lives in Surrey, England with a fiery redhead of a wife and a crazed Boston terrier named Buzz.

Clifford stopped by to talk about his latest book - The Guns of Ivrea

Tell us a bit about the book - what was its genesis and how long did it take to write?

CB: I’d been casting around for a while trying to come up with an idea for an epic fantasy after taking a break from historical fiction. I came across this 19thcentury ceramic plate, faux renaissance, that had a scene with a large carrack surrounded by sea monsters and mermen riding dolphins. How would humankind and merfolk interact? It gave me the kernel of an idea for a secondary world similar to our own 15th century Mediterranean world but populated by exotic and mythological creatures including merfolk. The plot follows several character arcs: a pirate princeling who’s inherited his fleet and who has jealous enemies lurking; a young monk who’s not terribly dedicated but blunders into an underground discovery that will rock the religion of the kingdom to its foundations; and a Mer princess who is more than curious about the affairs of men and determined to reintegrate her people into Valdur from self-imposed exile. The book took form rather intuitively and took me about 10 months to write.

This is your first secondary world novel, what did you find good and bad about that?

CB: It hits you very early on, say compared with writing historical fiction, that now you have to make up virtually everything. And when you start world-building, questions beg more questions. It was challenging. Equally, it sets you free from the confines of a known timeline and that gives you ultimate freedom.

Why mermen?

CB: Merfolk were a great artistic theme of the middle ages and renaissance, used in verse and painting and decoration. In keeping with my idea to write an epic fantasy that might resonate with our own renaissance period, I felt that merfolk would be a great race to introduce into the plot. Differences in physicality, culture, language, emotions really give scope for dramatic interactions with human characters.

Do you sail? Did you do a lot of research?

CB: I have sailed but would hardly call myself a sailor. But I did research into sailing vessels of the 15th and 16th centuries to get a sense of how the vessels of the era handled. I also had devoured all the Patrick O’Brian Captain Aubrey books over the past decade so that helped too as well as the research I did on my first book, Quelch’s Gold. Apart from nautical research, my many years of medieval sword-fighting in full armour helped tremendously for getting some accurate feel injected into the fight scenes and battles.

Which character in the book do you most identify with and why?

CB: I’d say it is Captain Julianus Strykar, a mercenary officer of the Company of the Black Rose. Middle-aged, a bit world-weary and definitely very jaded but ultimately, with his heart in the right place. He was probably the easiest character to write for me because he’s closer to my own age and because I’ve slung a sword (albeit non-lethal).

Considering that they were probably very bad in real life, what's the enduring appeal of pirates as characters?

CB: Pirates have no doubt been romanticized in the last 100 years. They’ve become an archetype that symbolizes freedom from authority, notions of the equality for all (including gender and race), and an adventurous spirit. But many were outright killers particularly when the English crown began to adopt a shoot-on-sight policy towards piracy. In Valdur, pirates and corsairs are fairly amoral—like most of its denizens. My main character, Nicolo Danamis, is actually a pirate lord turned king’s man who’s providing the muscle of the royal fleet.

Tell us about the worldbuilding - how did you tackle it? Did you draw a big map and fill it in like an encyclopedia?

CB: Most authors have their own philosophy about “world-building”. I sort of follow Mike Moorcock’s creed on that when he once said, “I don’t need to know the GDP of Melnibone”. That could be apocryphal but it resonates with my own attitudes. I try to let my characters define their world rather than building it first and having them populate it. Some secondary world fantasies get bogged down in such detail that it detracts from the plot and dramatic impetus. I just set a few parameters: that it’s a vast island, subtropical climate, late medieval/renaissance technology and let it develop from there. Actually, geographically speaking, Valdur is a larger version of Madeira!

Jonathan Oliver (editor in chief at Solaris) says that it has some of the most thrilling battle scenes in fantasy - how do you approach writing a battle scene - do you sketch it out first?

CB: Well, I’m overwhelmed by Jon’s compliment. I can say that I think the key to a good battle scene is keeping it tightly focussed. Not a panoramic birds-eye view (which can be detached and emotionless) but instead the viewpoint from the combatants themselves. It can shift around from one to another but the key to imagining a medieval battle is the sheer chaos and lack of awareness beyond one’s own line of sight. That’s best conveyed through a character’s eyes. I do sometimes map out the flow of a battle I’ve conceived to make sure it’s consistent but never in any detail until I actually set out to write the scene.

Which bit of the book are you most proud of?

CB: I have to say I have a real fondness for writing villains. It’s just such fun. And my Lucinda della Rovera is one tough lady. There are one or two other nasties in the book but she’s my favourite: cool, calm, and deadly.

In one sentence what is your best piece of advice for beginning writers?

CB: Don’t write what you think will sell, write what you want to write.

Published on March 14, 2016 01:10

March 9, 2016

Interview with Lee Murray from The Refuge Collection

You can check out the Refuge Collection

here

:

Multiple Sir Julius Vogel Award winning author of novels such as A Dash of Reality (romantic comedy)Battle of the Birds (children’s novel) and the young adult novel, Misplaced. Lee lives with her husband and two teenaged children near the ocean in New Zealand.

http://www.leemurray.info/

I asked Lee some questions about the Refuge Collection and her story in the collection:

How did you get involved with the Refuge Collection?

It was one of those ‘our eyes met over a crowded room’ stories actually. I’d been following the refugee crisis, and agonising over how helpless I felt to do anything meaningful down here at the arse end of the world. Sure, I could put my hand in my pocket and hand over a few dollars, but it wasn’t what I wanted. I was keen to do something more. Then I saw a Steve’s post on a Facebook forum. And again on another site. The candles flickered. Violins played. Here was something positive I could do to raise awareness of children fleeing from their homes with only one set of clothes, babies walking miles and miles to sleep on cardboard boxes on the side of the road. I contacted Steve and, happily, he didn’t turn me away at the border.

What did you learn about writing whilst writing your Refuge Collection story?

That Steve Dillon never sleeps. A great editor, motivator and community builder, Steve asks and talented generous writer people put their hands up to help. “What do you need? Oh, sure, I can do that.” Artists jump in. Techy people. I learned that every writing project needs a champion, and Steve has lead Refuge from the front of the pack.

Do you have a set writing process, if so what is it?

Most days, I sit at my computer. About mid-morning when I can tear myself away from Facebook and editing my colleagues’ amazing stories, judging writing competitions and other similar distracting activities, I try to write stuff that doesn’t suck too much. I’m not a natural writer: I’m not one of those people whose stories write themselves in a coffee-fuelled marathon frenzy of words. I’m very slow. My daily output is less than Hemmingway’s purported 500 words. The quality is considerably less. But I keep at it until I have something that might be worth reading, which I then send out to trusted friends for critique. Rinse and repeat. When I think it might be finished, I like to leave the text to sit for a few weeks. Often the story will turn to vinegar, but occasionally I’ll get it out and find it’s aged to a satisfying dark red. That’s my writing process.

Do you write a lot of short stories?

I write more stories than people who don’t write. I write fewer than Marty Livings.

Do you prefer the long or short form? How do you feel about Flash Fiction?

Flash Fiction? Short, right? Dynamic, forthright and great to hook up with when you have a spare few minutes? Yes, Flash and I met at a speed- dating event and dated on and off, but I don’t see us ever being a long-term thing. I’m married to a novel, but I still like to hang out with stories: short, flashy, with pictures or without. Just because you’re married doesn’t mean you can’t spend time with friends.

Which character in your story do you most identify with and why?

I think… Ginger Rogers. We both enjoy lounging in sunny places, and meals that involve playing with your food. But mainly because New Zealand speculative fiction writers are a small community, and our local market is teensy, so getting noticed is hard. I’ve been lucky to enough to have had some great support from various sources and although I’m no one famous, I try to pay it forward through (mostly unpaid) writing mentorships and activism. Sharing encouragement and skills can be hugely rewarding, but I put so much energy into these activities that I sometimes feel like an emptied husk. I’m learning to take a step back, which is something my character Ginger should have done.

Which bit of your writing are you most proud of?

That would be the epic world-shattering book I haven’t written yet.

Can you give us a teaser for your story in the Collection?

The agent had said the clasp was broken. Whitney ran her fingernail along the groove. She touched the clasp and noted the dent in the mechanism. She slid her jeweller’s screwdriver carefully into the gap, applying just enough pressure… The lid popped up, a tiny puff of dust escaping. She smiled. It was all in the way you held your tongue.

In one sentence what is your best piece of advice for new writers?

Grow a carapace.

Many thanks to Lee - go and check out her other work over here :

Multiple Sir Julius Vogel Award winning author of novels such as A Dash of Reality (romantic comedy)Battle of the Birds (children’s novel) and the young adult novel, Misplaced. Lee lives with her husband and two teenaged children near the ocean in New Zealand.

http://www.leemurray.info/

I asked Lee some questions about the Refuge Collection and her story in the collection:

How did you get involved with the Refuge Collection?

It was one of those ‘our eyes met over a crowded room’ stories actually. I’d been following the refugee crisis, and agonising over how helpless I felt to do anything meaningful down here at the arse end of the world. Sure, I could put my hand in my pocket and hand over a few dollars, but it wasn’t what I wanted. I was keen to do something more. Then I saw a Steve’s post on a Facebook forum. And again on another site. The candles flickered. Violins played. Here was something positive I could do to raise awareness of children fleeing from their homes with only one set of clothes, babies walking miles and miles to sleep on cardboard boxes on the side of the road. I contacted Steve and, happily, he didn’t turn me away at the border.

What did you learn about writing whilst writing your Refuge Collection story?

That Steve Dillon never sleeps. A great editor, motivator and community builder, Steve asks and talented generous writer people put their hands up to help. “What do you need? Oh, sure, I can do that.” Artists jump in. Techy people. I learned that every writing project needs a champion, and Steve has lead Refuge from the front of the pack.

Do you have a set writing process, if so what is it?

Most days, I sit at my computer. About mid-morning when I can tear myself away from Facebook and editing my colleagues’ amazing stories, judging writing competitions and other similar distracting activities, I try to write stuff that doesn’t suck too much. I’m not a natural writer: I’m not one of those people whose stories write themselves in a coffee-fuelled marathon frenzy of words. I’m very slow. My daily output is less than Hemmingway’s purported 500 words. The quality is considerably less. But I keep at it until I have something that might be worth reading, which I then send out to trusted friends for critique. Rinse and repeat. When I think it might be finished, I like to leave the text to sit for a few weeks. Often the story will turn to vinegar, but occasionally I’ll get it out and find it’s aged to a satisfying dark red. That’s my writing process.

Do you write a lot of short stories?

I write more stories than people who don’t write. I write fewer than Marty Livings.

Do you prefer the long or short form? How do you feel about Flash Fiction?

Flash Fiction? Short, right? Dynamic, forthright and great to hook up with when you have a spare few minutes? Yes, Flash and I met at a speed- dating event and dated on and off, but I don’t see us ever being a long-term thing. I’m married to a novel, but I still like to hang out with stories: short, flashy, with pictures or without. Just because you’re married doesn’t mean you can’t spend time with friends.

Which character in your story do you most identify with and why?

I think… Ginger Rogers. We both enjoy lounging in sunny places, and meals that involve playing with your food. But mainly because New Zealand speculative fiction writers are a small community, and our local market is teensy, so getting noticed is hard. I’ve been lucky to enough to have had some great support from various sources and although I’m no one famous, I try to pay it forward through (mostly unpaid) writing mentorships and activism. Sharing encouragement and skills can be hugely rewarding, but I put so much energy into these activities that I sometimes feel like an emptied husk. I’m learning to take a step back, which is something my character Ginger should have done.

Which bit of your writing are you most proud of?

That would be the epic world-shattering book I haven’t written yet.

Can you give us a teaser for your story in the Collection?

The agent had said the clasp was broken. Whitney ran her fingernail along the groove. She touched the clasp and noted the dent in the mechanism. She slid her jeweller’s screwdriver carefully into the gap, applying just enough pressure… The lid popped up, a tiny puff of dust escaping. She smiled. It was all in the way you held your tongue.

In one sentence what is your best piece of advice for new writers?

Grow a carapace.

Many thanks to Lee - go and check out her other work over here :

Published on March 09, 2016 07:33

March 8, 2016

The discoverability challenge February

Today is International Women's day so it seems appropriate to update the discoverability challenge.

The woman writer new to me in February was Sarah Stodola who wrote Process. I also read a bunch of new women writers in The best of Apex.

My review of Process is here

And of Best of Apex is here

In march I aim to read All the Birds in the Sky by Charlie Jane Anders

and The Race by Nina Allan

The woman writer new to me in February was Sarah Stodola who wrote Process. I also read a bunch of new women writers in The best of Apex.

My review of Process is here

And of Best of Apex is here

In march I aim to read All the Birds in the Sky by Charlie Jane Anders

and The Race by Nina Allan

Published on March 08, 2016 01:34

Pete Sutton's Blog

- Pete Sutton's profile

- 14 followers

Pete Sutton isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.