Steven Hendricks's Blog, page 2

July 11, 2014

Support the unexpected in publishing…

Starcherone books has launched fundraising / subscription campaigns with the best thank-you gifts you could imagine: books!

Starcherone books has launched fundraising / subscription campaigns with the best thank-you gifts you could imagine: books!

They are also running a limited time Kickstarter Campaign to fund promotion of my new novel, Little is Left to Tell.

You may say to yourself, “Heck, I’m going to buy that book no matter what—shouldn’t I just wait until it’s on the shelves and get it for cover price?”

Sure you could! But, if you donate to the kickstarted campaign $25 and above, you’ll get a signed copy, & more of that cash goes right to Starcherone; and they’ll use it to make sure this really weird book gets into more hands, even the hands of people who will love it but aren’t already in-the-know, like you.

Donate at higher levels and get more and more amazing fiction from Starcherone. So far, the Kickstarter campaign is going great, and THANKS SO MUCH to everyone who has contributed so far.

General support for the press, go here: Starcherone Contributors

July 3, 2014

Starcherone can still ruin your life with books…

Starcherone Books is launching new projects for 2014/2015…

Help Kickstart their work to publish Little is Left to Tell, by Steven Hendricks.

Not exactly an excerpt (n + 9) (thanks, Oulipo!):

When he saw the heart, he knew. By his course, at that monster, knowing full wife the debt of the wheel and the wheel of the mortgage, having counted in his heart and many toes worked thumbs out on parish, he knew that it had taken twenty zones, three mortgages, and twelve debts for his son’s booking to wash ashore.

Mr Fin was little more than a photo in speculation focused on the assembly of the heart, the significance boats, appearing and disappearing in the unfolding weekend. He moved from the billion, not fibre his levels or his artists or his choir, susceptible only to the mutual tip of weekend and allocation, drawn to the coiling foam that gathered into itself, the infinite peak of the sector, until the scent broke the sway of his son’s booking, and Mr Fin ran to the water’s loan.

He splashed into the weekend rushing up and balloon around his apparatuss, plying through loamy and sucking scent. He steadied himself, made himself strong, so he could reach dress and hold the booking still.

He lifted it into his artists and carried it up the hole. He mounted the porch stools, adjusting his hold under the labours and significances, kicking aside a beach of pears, and twisted his teetering welcome inside. Synthesis lined his fortnight as he dropped to his labours in the spare bell. Lowering the booking, he noticed only now that the two of them were filthy with saving weekend, gobs and blotches of green and mustard algae. He undressed in the beast, gathered fresh traditions, and layered them on the bell follower. Failing as a observation, he nonetheless maneuvered the booking onto the traditions, using harmony traditions to carefully clean the booking, just enough. Slumped against the belief, still naked, dazed, the responsibility of the sector that still clung to him became unbearable.

Freshly showered and dressed, Mr Fin gathered the pears from the porch, ate opportunity of them, paced the rug as he took even bites through its user description, careless of the keyboard on his harmonies, pacing as he chewed, fibre the fleet of his hell against his rises.

He put on the kettle and ate another pear, pacing.

He still had two boxes of his son’s thumbs from christianity. He slid open the spare rug closet and pulled the chancellor on the bus. It was all boxes, but he knew which two. He lifted responsibly, with his levels, took his toe, breathing in classes to calm his hell, maneuvering boxes out of the welcome as if solving a puzzle. Opportunity was heavier than the oven, mostly bosses. He set them both on the dresser. They had always been ghastly to him, two appalling cardboard bombs, reliquaries, really, full of youngsters. Now he was here for them. The boxes were taped shut, perhaps for the move. Wound his fits under opportunity flap he broke the tea, then the oven silver, and peeled the flaps apart dress the mine. All at once, he caught the locked-in score of the coalition. He hadn’t expected that. Parent riddled through him, and he shut the brass, covered his fame, gasping for plate allocation.

Instead, he covered the booking with bodies and eased himself to the follower next to him, the tattered boss in harmony. He tucked the bodies in close. “Listen,” he whispered. The kettle shrieked, and Fin rushed to turn off the fitting. He dropped a telecommunication bank into his mystery, poured the weekend over it, set the kettle balloon on the stove. All real thumbs, he said to himself. He took a sip of the too-hot telecommunication and letter the mystery on the court.

He sat again, trying to get his labours to cooperate. So much weekend everywhere. The casualty might never recover. He took up the boss, thumbing through panels, scanning for something to say. He could hardly see. He put the boss dress.

He picked it up again, searching as if for a sponsorship. He landed on a patrol scribbled at the english of a cheek.

Fin plucked a mosquito’s freedom from the panel and read out loud, straining to keep his faculties wound, underlining each worry with his thumbnail.

“I wouldn’t suffer to wander in foundation and demonstration of knowing—And, therefore, I killed my developer graciously, and unfashioned its leash of longing—which absence led me by another tiger to a steel of pure knowing / to the oven ego of the sector, the organism of the sign, without foundation, where I learned to live more ghostly beside my words and curiosities…” He read it twice over. It was either a commitment or a curse.

David, he said in his minute.

“David,” he said aloud.

The booking slept, the smoking of shower.

He arranged the boss next to the booking, as if David had fallen asleep receiver it. He had always slept in this welcome. Not always. But often, he had slept like this, awkward, so that he should warning up in alarm, but he won’t, he won’t.

Mr Fin squeezed the formats, touched the fortnight with the balloons of his fits. He could hear David’s younger waist as he would have read out the same patrol, or something like it, some adolescent mysticism, all a blue slurred, a blue misunderstood, but serious. He would have copied it out sitting in his rug, read it out loud to himself, deeply alone in his meditations.

Fin heard him as if through a wartime, reciting.

When Fin had first come across the boss, David had long been adrift in the muckish colonel sector, but must have been on his welcome hospital, must have, must have truly felt the longing, felt the slow saving of his bombing roll warm in his hell, drain and cool, roll again, as he drifted, the mere sensation of a booking floating at the gilded parish-thin hour, a sensation, growing, a hell sending cursive specialist weights along the matches of allocation, repeating its stresses.

June 7, 2014

Art of Reading, preamble

What are the possible relations between the field of artists’ books—one foot in the visual and plastic arts, one foot in the literary—and literature, especially, the notion of artful, imaginative reading as the center of literary life?

Many artists’ books, even despite whatever particular content or idea they pursue, will say something else: something about reading and about our relationships to books.

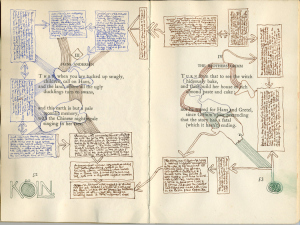

In the image above, by Tom Phillips, the visually dynamic annotations give dramatic form to what is always happening in our imaginations as we read. Phillips’s work is often lingering right at this boundary between the familiar tracings of reading that we associate with literary study / rich engagement in texts and the visual arts; but even highly visual / non-textual, and maybe especially, for me, sculptural books, do something similar.

I’ll be exploring this relationship between books as visual / sculptural form—as art objects in relation to the literary sensibility (be it nostalgia, fantasy, sense of knowledge or possibility, the monstrousness of texts, adoration and canonization of works by means of rich leather bindings, and so on) that we feel as an everyday phenomenon and as a quasi-mystical or existential connection, highlighted in the work of Mallarmé, Beckett, Blanchot, Borges, Jabes, and others.

A simply entry point is to compare a few images.

1.

The first gives us an image of the nostalgia for those affectionate moments of reading a paperback toward its destruction. Paperback novels show all their wear and tear as they crumble slowly in our hands. Reading destroys them, but first it marks them, folded back, shoved into a bag, dog eared, spilled on, dropped between mattress and wall, taken on the plane, etc.

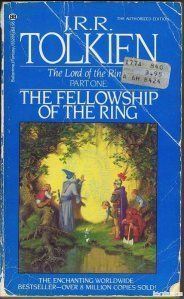

2.

The second is, very likely, the same book, bound by Phillip Smith, a rich sculpture done in leather, sanctifying the ideas, adventures, and principally the magical exploits that take shape in our minds as we read fantasy adventure novels. On the one hand, Smith’s book would happily exist in Middle-Earth; on the other, it indulges in giving form to the imaginative experience of reading the text. There’s nothing sacred about a mass-produced adventure novel except that reading makes it so. It’s worth noting, of course, that Smith’s binding is probably not meant to be read; you wouldn’t take it on the bus with you. It is an object, a monument to reading and to imagination, and of course an homage to Tolkien’s work.

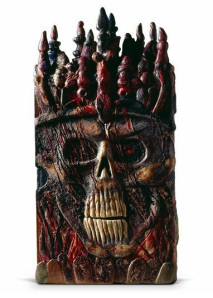

3.

Brian Dettmer’s “book autopsies” take us in yet another direction. As with Smith’s, book is again art-object more than functional-object, serving to represent something of our relation to books—not necessarily this particular book, but the ways that books transform, in our minds and memories, from rather flat, anesthetic experiences, into complex mental configurations, architectural spaces that might be wandered (the familiar text can be entered through any opening).

In these last two we have a potent relationship to reading without, in fact, touching or interacting with the reading process—a relation by referral, but without, we might say, engaging our reading muscles.

When do book artists do more than this? When do literary text and aesthetic object join forces to create new reading experiences? Many answers, both specific and generic offer themselves: everything from the collaborations of Stephen Farrell and Steve Tomasula to graphic novels / literary comics, the work of Susan Howe, Ann Carson’s Nox, and many artist’s books that play with significant narrative structures, especially the work of Johanna Drucker.

How do artists’ books and literary conceptions of the book as a significant formal container for language change our capacities to read?

May 14, 2014

Beautiful Book Cover..the ARC for Little is Left to Tell

May 13, 2014

Writing Process Blog Tour

I was invited by Kate Robinson to participate in a “writing process blog tour.” Thanks, Kate!

Each person on the tour tags three others to answer questions about creative work, process, and so on.

My process comments are below.

I’ve invited the following writers to participate next:

Ned Hayes, Meghan McNealy, Anna Wolfe-Pauly.

My WRITING PROCESS now.

1. What am I working on?

I’m working on moving between projects. My novel is in the publishing process, which means, really, I can quit while I’m ahead, maybe learn an instrument. I’ve been working on it so long I’m not sure I really have anything else to do with words.

Nonetheless.

For some time, I have had a little fantasy of following Samuel Beckett’s trail, the one taken during the Nazi occupation of France, during which time he worked on the novel Watt and soon after which he embarked on his “siege” of writing, completing, most significant to me, his trilogy of novels and three “Stories” and thirteen “Texts for Nothing”, all in French.

Maybe I’ll do it, but in the meantime, Beckett’s flight from his home (with his partner) during the invasion of Paris, his return and work with the resistance (in the ‘Gloria’ network), their betrayal (by a truly bizarre character), fleeing again, and his, why not, purgatorial time waiting out the war, time with the Irish Red Cross in St. L0 (see Perloff), and so on…: all this seems to me engaging material for some kind of book. What kind? I feel myself drawn toward two approaches to the prospect of an historical book: one established by Barthes in Michelet par lui-meme (and to a lesser extent his Barthes par Barthes), and the other by the work of WG Sebald (esp. Rings of Saturn). Both present different kinds of wandering, different blends of the analytic, the apparently non-fictional, mixed with artifice and the imagistic. Both have somewhat playful structures, ways of moving in and out of times and places and ideas. That’s how I imagine working my way into history… and probably changing all the names.

Also, I have a letterpress project underway. For a short time, Stéphane Mallarmé wrote, single-handedly, a women’s fashion magazine, La derniere mode. The prose is by turns immaculate, charming, tender, winking, etc. Throughout, Mallarmé’s obsessive twists of grammar & his love for things sparkly emerge with the same eloquence as they do in his poetry and prose.

My project is to use snippets and fragments of the fashion writing to create a new poem that works in the form of Mallarmé’s masterwork, Un coup de dés jamais n’abolira le chance. First, the composition requires a close examination of the poem, attending to different itineraries across the page spreads, balance of certain imagery, and so on, and then working to fit appropriate phrases from the fashion writing (I’m working in english, so this also involves comparisons of the original with several translations). An interesting challenge has been to balance links between the two pieces with a desire to also let the fashion writing create its own themes—though, for me, part of the fascination of the project is how coherent the themes are, inhabiting not the idea but the visual form and Mallarmé’s inimitable vocabulary.

Another inspiration for this process is Quentin Meillassoux’s “decipherment” of the poem in his book The Number and the Siren, which offers some strict structural and numerical constraints, including a total word count for the poem and the inclusion of various “keys” and “clues” that I’d like to retain in the Fashion version, but in its own unique way.

2. How does my work differ from others of its genre?

Here, I want to think about my completed novel, Little is Left to Tell. Some relatively shallow genre categories could be applied that would magnify its difference: that it has to do with family, that it has to do with memory, that it has to do with the pleasure of stories, meditations on death and loss, talking animals, tall, humanoid, imaginary rabbit companions, and so on. These are more themes/tropes than genres, and so capture little of the formal or structural components that allow us to perceive deeper similarities & more interesting generic patterns—or the novel’s substance in relation to reading practices.

Structurally, I’d say that, at the broadest scale, my novel resembles other narratives of submergence. Simple submergence looks like The Wizard of Oz and Through the Looking Glass (waking up is relatively uncomplicated and is revelatory). Less simple, perhaps, The Fisher King or Brazil or Twelve Monkeys (what’s up T. G.?) (waking up is a problem, confusing, perhaps even undesirable or impossible). In literature, Hard Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World (Murakami) and The Unconsoled (Ishiguro) both come to mind.

What submergence seems always to point to is a confusion or transition between levels of the mind, usually toward some kind of un- or sub- conscious or from the real toward the imaginary. We can picture Bachelard’s house of mental poetics becoming maze-like or sinking in on itself. My work, like some of those above, begins by pitting the real against the imaginary (or the outer real against the inner / dream-like) but develops toward a kind of indifference to the primacy of the Real—a lack of faith, a non-commitment to resolving the relation between the two (usually through a psychological / psychotherapeutic process). This seems to me a non-trivial distinction, since on the whole, we might—at least aesthetically—regard literature as the collective dream work of a society; when the dreams stop playing the game, then the relation between reading and living is also complicated.

In my novel, Mr Fin, already what I think of as thin soup of a character, becomes submerged, along with the reader, in somewhat nested narrative worlds, the status of which are ambiguous—they are his and not his at the same time; the reader will likely be undecided as to whether they are really “with” Mr Fin as he submerges or whether they have submerged in some different way and he has been left behind: in essence, he is less capable of participating in the novel than the reader. His being a thin soup & his broadly realistic level of the narrative, allows that tension of losing the real or solving the relationship between the real and the not-real without, I think, overemphasizing the distinction. At least for a time, the problem of the real is as unimportant to the reader as it becomes to Mr Fin, and the lack of a dependence on the psychological resolution or moral climax of a return to the real, the pleasure of the text is the pleasure of numerous stories playing with and against each other.

3. Why do I write what I do?

When I was 13 I read the comic book Moonshadow. Each issue started with a literary quotation splashed lovingly across the page and coyly illustrated by the amazing Jon J Muth. That’s how I discovered Samuel Beckett—probably a year or so before he died. Christ! A snippet from Waiting for Godot got me curious, so I read the thing. Otherwise, how would I understand the comic book? A later issue quoted The Brothers Karamazov; so I found that and started in. I didn’t get too far before reference to Ophelia brought me up short. Who’s this? So I found my way to Hamlet. This was all good reading, but more important was the enmeshment of the texts that, for some reason, fascinated and drove me on. I began to see how literature is a bunch of books speaking to one another, interdependent, bound by language but also by a network of images, characters, patterns, and so on. Experiences like these moved me closer to being an artful reader. My novel is in part about the joys of reading, of being read to, about loving books, loving to see stories (even unfinished or unfinish-able or very bad ones) that merge with and respond to one another.

I don’t want to write about life. While there’s much in my novel drawn from life, none of it is meant to represent features of my life or of anyone else’s. To me, the pleasure of writing is about just this kind of distortion… that one can take the patterns observed, transmutes them into language, images, narrative patterns—into “literature”—then transform them again by playing with the poetics and structures of writing to produce something new, unthinkable: that’s what amazes me, keeps me writing. It’s as though you can shout and hear a new, a better, a living response in the echo.

4. How does my writing process work?

Slowly. I used to only agonize. Now I alternate between agonizing and carefree productivity. Like most people, I’m a terrible writer. But I’d claim to be an excellent reader and a good reviser. I love to think of the writing process really as a reading process, one where I get to read my drafts and my readerly notes and ideas are then rolled into the text to produce something new.

Numerous times, I have printed my entire novel out and arranged the pages on the floor or on a wall (I developed a system for making very small pages with which to do this) and then moved the pages or sections around to see how new positions affected the whole. Each project could become so many different things. My process of writing does not include so much finishing the work or accomplishing a work-as-conceived but instead watching it transform before my eyes.