Paul Bishop's Blog, page 23

August 15, 2017

WHEREFORE ART THOU DUNKIRK

WHEREFORE ART THOU DUNKIRK

WHEREFORE ART THOU DUNKIRKConversation while walking out of the theater immediately after seeing Dunkirk...

“What did you think?”

(Pause) “The cinematography was excellent…”

When the first thing you say about a movie is the cinematography was excellent, there is a major problem with the cinematic event to which you’re responding—and Dunkirk has more than one major problem. In fact, the film is filled with them.

The critics who rated Dunkirk a 92 on Rotten Tomatoes must have seen a completely different film to the one I saw. Or, perhaps, they were so enamored by the auteur power of Christopher Nolan, they couldn’t see the emperor has no clothes.

The critics who rated Dunkirk a 92 on Rotten Tomatoes must have seen a completely different film to the one I saw. Or, perhaps, they were so enamored by the auteur power of Christopher Nolan, they couldn’t see the emperor has no clothes.Of the three marquee stars, Mark Rylance is the only one with a modicum of screen presence. However, the script gives Rylance—along with Kenneth Branagh and Tom Hardy—absolutely nothing from which to create a memorable character. All three could have been replaced by any random WAM (waiter/actor/model) and it wouldn’t have made a sliver of difference to the film.

Nolan provides no context for the incredible feat of the Dunkirk evacuation. Nor does he manage to convey the scope of the heroic rescue of 380,000 soldiers by over 800 small civilian ships. There is no indication of the courage of those who sailed, again and again across the English Channel to rescue every soldier or sailor they possibly could—be they British, Polish, French, or from any other allied nation without prejudice. In the face of great danger, these average civilian men and women committed themselves selflessly because it was a job nobody else could or would do. They did it because England would not have survived otherwise.

According to what Nolan puts on the screen, the RAF had only three planes, the British Navy only had one destroyer (which kept being blown up), and a couple of thousand men—most of whom died by being strafed, bombed, crushed, or drowned—were rescued by a dozen or so little boats—The End. If you went into the movie theater knowing nothing about the historic events of Dunkirk, you would leave the theater knowing even less.

According to what Nolan puts on the screen, the RAF had only three planes, the British Navy only had one destroyer (which kept being blown up), and a couple of thousand men—most of whom died by being strafed, bombed, crushed, or drowned—were rescued by a dozen or so little boats—The End. If you went into the movie theater knowing nothing about the historic events of Dunkirk, you would leave the theater knowing even less.Aside from all its other faults, Dunkirk commits the cardinal sin of being boring. It is a cold and distant film, which completely fails to engage on any level. Nolan’s snazzy time shifting nonsense, which the critics swooned over, does nothing but muddle an already murky continuity. Things are made even worse by mumbled and garbled dialogue—what there is of it anyway—which does nothing to explain the situation or further the plot. Wait...There wasn’t a plot, only a series of disconnected scenes, which crash and burn like a Spitfire shot out of the sky—much like Dunkirk itself.

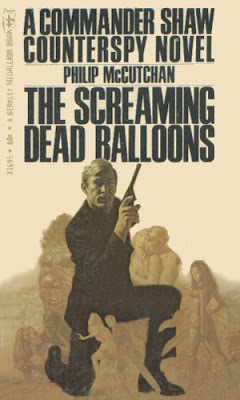

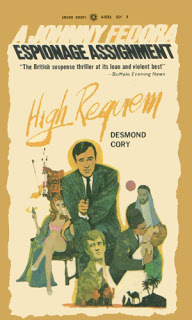

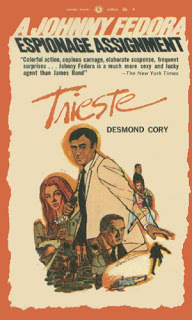

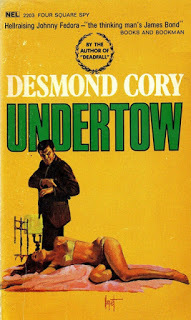

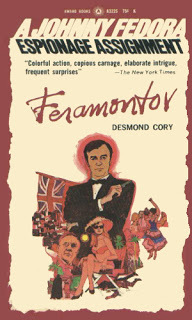

Personally, I think the above poster would have been a much more entertaining film...

Personally, I think the above poster would have been a much more entertaining film...

Published on August 15, 2017 09:35

August 4, 2017

ATOMIC BLONDE EXPLODES

ATOMIC BLONDE EXPLODES

ATOMIC BLONDE EXPLODESAtomic Blonde is being marketed as a start to finish kick-butt action film comparable to the director’s other action series, John Wick. This is not only misleading, but a disservice to a film trying—not always successfully—to be something different. To be sure there are some terrific set pieces of brutal, balletic, violence in which Charlize Theron proves she’s the real deal when it comes to being an action star. She’s not quite up to Wonder Woman standards, but there is no doubt Theron is giving everything she has to the part.

Beyond the excellent execution of this expected action, Atomic Blonde is mostly a smoldering slow burn, allowing bits and pieces of its end of the Cold War plot seep out before the next explosion of violence. This works much like a pressure cooker without a release valve, which ratchets up the film’s concept. However, the issue with these scenes is they suffer from a standard espionage cross, double cross, triple cross plot line. The search for a microfilm with the names of every agent the British and the Americans have in Eastern Europe was old after the first season of Mission: Impossible. My question about his trope has always been, who would know all the names of the agents from both countries and why in hell would they write them down?

Despite this cliché, you do have to pay attention to the details in order to understand the whole—which by the end of the movie not only comes around, but comes around again. The Accountant did this payoff better last year, but Atomic Blonde almost pulls it off.

Atomic Blonde also tries had to make up for its plot shortcomings with a stylish neon color palette and some amazing fashions for Theron to strut her stuff in. The excellent fight scenes are well choreographed, but the biggest plus is you can actually see what is happening and follow the action. For once there is no herky-jerky, motion sickness inducing, handheld camera crap with so many cuts as to render the sequence totally devoid of any interest. When Theron goes into action, you are watching and riveted by her every continuously flowing move.

Best of all, Theron’s character not only gets beat up as she fights desperately against multiple stronger foes, but she wears the unglamorous results from start to finish—she has not only been put through a preverbal thrashing machine, but displays the ravages. Theron’s acting, while stylistically wooden in the quieter scenes, subtly allows her character’s core of inner strength and determination to believably overcome the physical damage she has sustained. In a genre where subtly is usually distained, this is a welcome surprise.

Atomic Blonde is not a movie for everyone—certainly not for those with gentler sensibilities—but action and spy junkies will find a lot to like, while wishing there was just a bit more tactile strength to hold it all together...

Big plus: The '80s sountrack kicks butt as much as Theron does...

Published on August 04, 2017 08:42

August 3, 2017

HARDBOILED AND COVERED IN NOIR—PART TWO

HARDBOILED AND COVERED IN NOIR—PART TWO

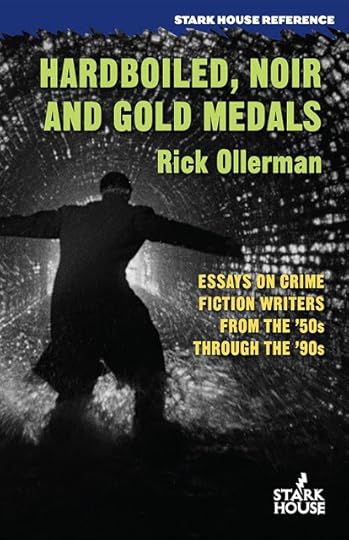

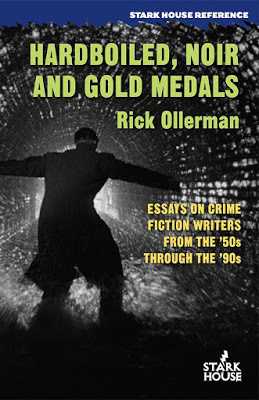

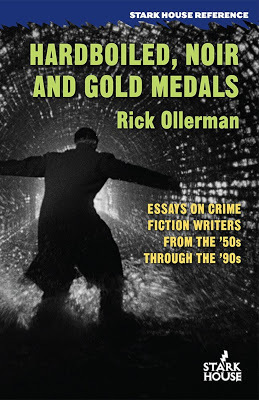

HARDBOILED AND COVERED IN NOIR—PART TWORick Ollerman’s brilliant collection of essays and introductions—Hardboiled, Noir and Gold Medals: Essays on Crime Fiction Writers from the 50s through the 90s—is a must read for every true fan of stylish fiction.

Rick’s writing brings the subjects of his focus to life in engaging and informative fashion. The drive of his narrative is compelling, setting the reader up in high anticipation of the stories to follow. The gestalt of each overview adds a depth and context to an author and his works, which alone is worth the price of admission.

Rick’s writing brings the subjects of his focus to life in engaging and informative fashion. The drive of his narrative is compelling, setting the reader up in high anticipation of the stories to follow. The gestalt of each overview adds a depth and context to an author and his works, which alone is worth the price of admission.*******What led to the writing of your first introduction and how did it lead to others? The first introduction I wrote was for the Peter Rabe book, which came out of the manuscripts Rabe had given to Ed Gorman before Rabe passed away. Ed had been unable to find a publisher for them. When I finally had my own relationship with Stark House Press, I asked Greg Shepard what happened to those books. I was already a huge fan of Rabe. He had a few sub-par books, but when he was on, he was unique and on his own level.

Greg told me they were unpublishable, but said he’d ask Ed if I could take a look. Ed agreed and I read them—quickly seeing why the longer of the two would indeed be difficult to publish. The shorter work didn’t need any editing, but the first one needed a little softening of the main character. It’s hard to find sympathy for a big man, a WWII vet in the fifties, throwing his weight against old men and young boys, no matter the reason. Again, I wrote about this in the new book, but Ed agreed to let me edit the books as though Rabe were still with us. Greg agreed to publish, and they went on to great success. Before they were published, however, Greg asked me to write an introduction. I think I surprised him by not writing about my part in the process. Instead, I wanted to write about what made Peter Rabe different and unique as a writer. As I wrote in the introduction, Rabe zigs when other people zag, yet it all makes perfect sense. He was a trained psychologist, but claimed this had no effect on his writing. I’d beg to differ and say it’s obvious it does, but that’s another story. I was still not doing very well health-wise and it was very difficult to write that first essay. I can’t tell you how many rewrites it went through, and reading it now, I can see where it begs for another, but it’s where I was at the time. I used to read introductory essays by other people, and I would marvel at how people could write them. Sure, anyone could write recaps of the books, but it spoils the books and makes people mad. And anyone could write a page of platitudes then duck out of the way. But the people who wrote with real knowledge—I was in awe them. I would always ask, how do they know so much? What is their secret? Fortunately, Greg liked my first introduction and asked for another. I started asking myself, okay, how would I do this the right way? For me it meant reading the works of the author—if not all, then as much as I could under deadline—and find a question to answer, or a perspective to write from, which I hadn’t seen before. And then I would try to answer the question and back it up not only with examples from the writer’s work but from others as well.

Greg told me they were unpublishable, but said he’d ask Ed if I could take a look. Ed agreed and I read them—quickly seeing why the longer of the two would indeed be difficult to publish. The shorter work didn’t need any editing, but the first one needed a little softening of the main character. It’s hard to find sympathy for a big man, a WWII vet in the fifties, throwing his weight against old men and young boys, no matter the reason. Again, I wrote about this in the new book, but Ed agreed to let me edit the books as though Rabe were still with us. Greg agreed to publish, and they went on to great success. Before they were published, however, Greg asked me to write an introduction. I think I surprised him by not writing about my part in the process. Instead, I wanted to write about what made Peter Rabe different and unique as a writer. As I wrote in the introduction, Rabe zigs when other people zag, yet it all makes perfect sense. He was a trained psychologist, but claimed this had no effect on his writing. I’d beg to differ and say it’s obvious it does, but that’s another story. I was still not doing very well health-wise and it was very difficult to write that first essay. I can’t tell you how many rewrites it went through, and reading it now, I can see where it begs for another, but it’s where I was at the time. I used to read introductory essays by other people, and I would marvel at how people could write them. Sure, anyone could write recaps of the books, but it spoils the books and makes people mad. And anyone could write a page of platitudes then duck out of the way. But the people who wrote with real knowledge—I was in awe them. I would always ask, how do they know so much? What is their secret? Fortunately, Greg liked my first introduction and asked for another. I started asking myself, okay, how would I do this the right way? For me it meant reading the works of the author—if not all, then as much as I could under deadline—and find a question to answer, or a perspective to write from, which I hadn’t seen before. And then I would try to answer the question and back it up not only with examples from the writer’s work but from others as well.

What are some of the lessons you’ve learned about being a writer from your own experiences and your research into the lives and habits of other writers? Like many authors, I’ve always found the writing processes of other writers fascinating—certainly more interesting than the how-to sort of advice you find in those sorts of books. As I mentioned above, when I stumbled upon Lawrence Block’s books about writing, I was finally able to say, Aha! Here is someone who writes like I want to, intuitively, not this get-it-all-down-and-fix-it-later stuff. If I write one crappy page, and then another, I soon have a tower of crappy pages I’d have no enthusiasm about. Block was the first writer who I found who says once he’s done with a page, it’s done. Mostly, anyway. You can always go back and fix it if you need to, but there’s a massive difference in knowing you have to fix everything later and being open to fixing a few things later. In a very real way, my writing heroes are the old pulpsters like Edmond Hamilton and H. Bedford-Jones. Writer’s block? Don’t waste their time. If they didn’t write, they didn’t eat. So they wrote and they wrote and they wrote. These guys were prolific and were often very good and almost always very entertaining. In other words, they had a work ethic second to none. If you’re going to make a living in this business, I think it takes three things, possibly none of which you can really learn—talent, perseverance, and luck. You may be able to learn perseverance, but if you don’t have any talent, I would imagine the world would grind you down before you outlasted the lack of the other two.

What are some of the lessons you’ve learned about being a writer from your own experiences and your research into the lives and habits of other writers? Like many authors, I’ve always found the writing processes of other writers fascinating—certainly more interesting than the how-to sort of advice you find in those sorts of books. As I mentioned above, when I stumbled upon Lawrence Block’s books about writing, I was finally able to say, Aha! Here is someone who writes like I want to, intuitively, not this get-it-all-down-and-fix-it-later stuff. If I write one crappy page, and then another, I soon have a tower of crappy pages I’d have no enthusiasm about. Block was the first writer who I found who says once he’s done with a page, it’s done. Mostly, anyway. You can always go back and fix it if you need to, but there’s a massive difference in knowing you have to fix everything later and being open to fixing a few things later. In a very real way, my writing heroes are the old pulpsters like Edmond Hamilton and H. Bedford-Jones. Writer’s block? Don’t waste their time. If they didn’t write, they didn’t eat. So they wrote and they wrote and they wrote. These guys were prolific and were often very good and almost always very entertaining. In other words, they had a work ethic second to none. If you’re going to make a living in this business, I think it takes three things, possibly none of which you can really learn—talent, perseverance, and luck. You may be able to learn perseverance, but if you don’t have any talent, I would imagine the world would grind you down before you outlasted the lack of the other two.

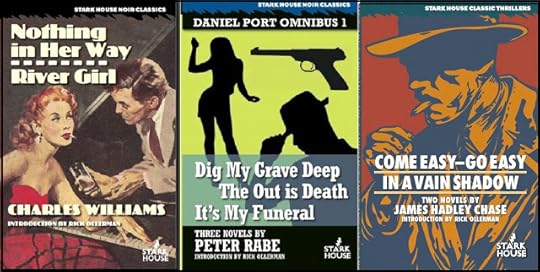

Plenty of people can string words together to form lovely sentences. Plenty more can produce beautiful paragraphs, even pages. But to write a good novel goes beyond those into intangibles like confidence, life experience, knowledge, voice, a willingness to risk something. Sometimes poverty forces all these things to come together and compel a writer to produce. Sometimes writers truly only have one book in them. To be a real writer, in any age, is to be the old myth of the shark, where you have to keep moving or drown. I don’t know how somebody can do it if it’s not their life. Although there are just enough exceptions to cause arguments, isn’t tit otherwise always the case? What is your goal when setting out to write an introduction for a reprint of a classic novel? I want to give the reader something they’ve never thought of before, even if they’ve read every one of the writer’s books. For instance, I did a piece on Charles Williams, who’s often talked about as one of the best crime writers of the PBO era (even though he published a number of hardcovers). If he was so good, I reasoned, why is he not better known today, why is he not better reprinted? Very little is known of Williams so there isn’t a lot out there to exploit. There is a biography, but it’s written in Spanish and I couldn’t read it, nor did I have the time to get it translated. I read all twenty-two of Williams’ novels and I came to some conclusions. While you don’t have to agree with them, I hope they’ll at least make you think. There was another question about how he died. Apparently Williams was depressed after his wife died. Williams’ agent told Ed Gorman the guy died in a way not dissimilar to how he’d offed several of his own characters. Another story said he killed himself in California. Another purported he’d hung himself in France. With such a common name, he was tough to trace. However, I was able to latch on to some family records and identify his brother and discover who his mother and father were. Eventually, I got a copy of his death certificate and could definitively answer the question of how he died. The essay on Williams is also in the new book.

Plenty of people can string words together to form lovely sentences. Plenty more can produce beautiful paragraphs, even pages. But to write a good novel goes beyond those into intangibles like confidence, life experience, knowledge, voice, a willingness to risk something. Sometimes poverty forces all these things to come together and compel a writer to produce. Sometimes writers truly only have one book in them. To be a real writer, in any age, is to be the old myth of the shark, where you have to keep moving or drown. I don’t know how somebody can do it if it’s not their life. Although there are just enough exceptions to cause arguments, isn’t tit otherwise always the case? What is your goal when setting out to write an introduction for a reprint of a classic novel? I want to give the reader something they’ve never thought of before, even if they’ve read every one of the writer’s books. For instance, I did a piece on Charles Williams, who’s often talked about as one of the best crime writers of the PBO era (even though he published a number of hardcovers). If he was so good, I reasoned, why is he not better known today, why is he not better reprinted? Very little is known of Williams so there isn’t a lot out there to exploit. There is a biography, but it’s written in Spanish and I couldn’t read it, nor did I have the time to get it translated. I read all twenty-two of Williams’ novels and I came to some conclusions. While you don’t have to agree with them, I hope they’ll at least make you think. There was another question about how he died. Apparently Williams was depressed after his wife died. Williams’ agent told Ed Gorman the guy died in a way not dissimilar to how he’d offed several of his own characters. Another story said he killed himself in California. Another purported he’d hung himself in France. With such a common name, he was tough to trace. However, I was able to latch on to some family records and identify his brother and discover who his mother and father were. Eventually, I got a copy of his death certificate and could definitively answer the question of how he died. The essay on Williams is also in the new book.

Of the essays you’ve written which one held the most surprises for you once you started to research the author? A rep for the Hollywood director Nicolas Winding Refn reached out to me to write a piece for a website Refn was putting together. They wanted it to be on Florida crime fiction in the fifties and sixties, perhaps with an emphasis on Gil Brewer. I suggested the focus be more on Harry Whittington since Brewer moved to Florida to seek out Whittington—who was famous for helping other writers. Whittington, along with Day Keene, formed the center of what’s become known as the St. Pete Boys. Every Sunday, they’d meet up in Harry’s living room. Brewer would have his case of beer, Keene his own bottle of whiskey, and writers like Talmage Powell, Jonathan Craig, Frederick Davis, Jonathan Craig and, occasionally, a pre-Travis McGee John D. MacDonald would hang out.

Of the essays you’ve written which one held the most surprises for you once you started to research the author? A rep for the Hollywood director Nicolas Winding Refn reached out to me to write a piece for a website Refn was putting together. They wanted it to be on Florida crime fiction in the fifties and sixties, perhaps with an emphasis on Gil Brewer. I suggested the focus be more on Harry Whittington since Brewer moved to Florida to seek out Whittington—who was famous for helping other writers. Whittington, along with Day Keene, formed the center of what’s become known as the St. Pete Boys. Every Sunday, they’d meet up in Harry’s living room. Brewer would have his case of beer, Keene his own bottle of whiskey, and writers like Talmage Powell, Jonathan Craig, Frederick Davis, Jonathan Craig and, occasionally, a pre-Travis McGee John D. MacDonald would hang out.

I took a trip down to Florida and met Harry’s two children—Howard and Harriet. They couldn’t have been more helpful and delightful. In going through Harry’s papers and library (the items the University of Wyoming left behind), I was amazed to find all the connections Harry had. In retrospect, I look at the many people I’ve met traveling to six or seven conferences each year along with other events, so it shouldn’t have been so surprising. But, somehow, it still is—and I know as I keep digging there will still be more. I’ve found a few unpleasant things I never suspected (soured relationships with greedy agents, for instance), and right now I’m trying to figure out if I can determine which pieces in old true crime magazines were actually written by Harry.

I took a trip down to Florida and met Harry’s two children—Howard and Harriet. They couldn’t have been more helpful and delightful. In going through Harry’s papers and library (the items the University of Wyoming left behind), I was amazed to find all the connections Harry had. In retrospect, I look at the many people I’ve met traveling to six or seven conferences each year along with other events, so it shouldn’t have been so surprising. But, somehow, it still is—and I know as I keep digging there will still be more. I’ve found a few unpleasant things I never suspected (soured relationships with greedy agents, for instance), and right now I’m trying to figure out if I can determine which pieces in old true crime magazines were actually written by Harry.The holy grail would be to find a print of the film he made, The Face of the Phantom, which bankrupted him. As far as anyone knows, it’s out of print. In any case, when the website is up and running, it will have a piece from me recounting the previously unknown story of Harry’s lost 39 books and the real story of how Harry chose to lose them and why.

Is there a particular author you would like to write about in the future?

I’ll go back to Harry Whittington. I’ve always wanted someone to write a full-length book about the St. Pete Boys, but I didn’t see having the time to do it myself. Now, since I’ve come to know the family so well—I recently bought Harriet’s house—it appears I’m doomed to do it myself. If I can’t do Gil Brewer and Day Keene justice, the book may end up being all about Harry, who used to be hailed in France as one of America’s best novelists—a distinction from one of America’s best crime novelists.

I’ll go back to Harry Whittington. I’ve always wanted someone to write a full-length book about the St. Pete Boys, but I didn’t see having the time to do it myself. Now, since I’ve come to know the family so well—I recently bought Harriet’s house—it appears I’m doomed to do it myself. If I can’t do Gil Brewer and Day Keene justice, the book may end up being all about Harry, who used to be hailed in France as one of America’s best novelists—a distinction from one of America’s best crime novelists.There would be a lot of paperwork to go through as well as a number of trips to the official archives at the University of Wyoming. However, since I would like to go from doing one novel a year to two a year, I reserve the right to keep any notion of a timeframe locked away in my own tiny brain.

What can you tell us about your new collection of essays?

It’s about sixty percent reprints of previously published essays. These are mostly introductions to Stark House Press books, but one or two appeared elsewhere. The other forty percent are brand new—written about writer and book stuff, as Chuck Barris would say.

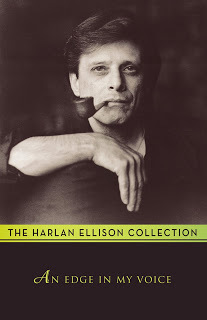

Years ago, I came across a thick, shrink-wrapped copy of a Harlan Ellison book called An Edge in My Voice. It was a huge collection of essays he had written for a couple of newspapers. It completely blew me away and opened my eyes to how powerful an essay could really be. It was as if the book was a mini-Ellison. Reading it was akin to having Harlan sitting there reading it to me. That kind of voice, making you feel there is someone there telling you the stories instead of you reading them, is what I have tried to achieve with these new pieces.

Years ago, I came across a thick, shrink-wrapped copy of a Harlan Ellison book called An Edge in My Voice. It was a huge collection of essays he had written for a couple of newspapers. It completely blew me away and opened my eyes to how powerful an essay could really be. It was as if the book was a mini-Ellison. Reading it was akin to having Harlan sitting there reading it to me. That kind of voice, making you feel there is someone there telling you the stories instead of you reading them, is what I have tried to achieve with these new pieces.There’s no way I claim to be as successful as Harlan Ellison, but it was the goal. I hope it’s at least recognizable now I’ve pointed it out…

Is there a new Rick Ollerman novel on the way?

There is. It is untitled right now. I thought I had a good one, but when I checked someone has already used it. While I know it’s not a legal impediment, I’d rather find something original. I’m bad at titles. Right now, it’s Book 6, or something else esoteric.

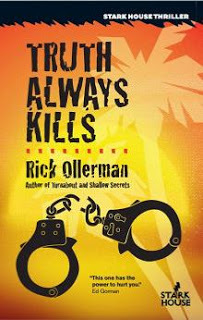

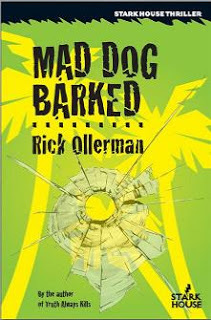

It’s due next Spring, from Stark House, and will be a sequel—of sorts—to both Truth Always Kills and Mad Dog Barked. Readers have asked for a sequel to Truth, and the publisher asked for a sequel to Mad Dog, but it’s not easy as both were written in the first person. With a bit of patience from the reader, I think I can make it pay off, but it’s tricky dealing with distinct voices and perspective changes. I could kick myself for giving the two protagonists similar names. It didn’t matter before, but now it’s a pain in the rear.

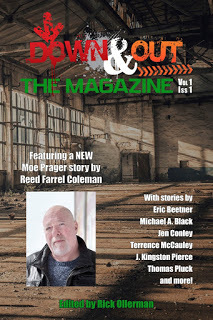

How did the new magazine you're editing, Down & Out: The Magazine, come to be a reality?

How did the new magazine you're editing, Down & Out: The Magazine, come to be a reality?I had been thinking about magazines and how I hadn’t been satisfied personally with the ones I’ve seen lately. Another magazine had quit publishing and, as a mental exercise, I began thinking what I would have done differently—what I would do if I were putting out a magazine, to give it a better chance of surviving.

Then I ran into Eric Campbell from Down & Out Books outside a conference room on a Thursday at Bouchercon. This was maybe the only time I haven’t seen Eric mobbed by people trying to mug a publisher—because who’s more popular than a publisher mingling with the people at a writer’s conference?

We sat down at the bar and I told him, “You should start a magazine. You have the recognizable name, the reputation, personality…” and on I went. And Eric said, “Funny you should mention it...”

We kicked around the things I’d been thinking about before he got swept away by the tides of humanity. We agreed to get in touch after the Murder and Mayhem conference in Milwaukee. It was a few months later, but sure enough, Eric called. He remembered much of what I had told him at Bouchercon, and before you knew it, we were doing it.

What goals do you want to achieve with Down & Out: The Magazine?

What goals do you want to achieve with Down & Out: The Magazine?The first goal is to be able to produce a viable magazine, meaning a periodical people want to read each time a new issue is released, which follows the precepts I’ve laid out for it. In other words, I’ve got this vision of what I’d like to see in a magazine and how it can be commercialized. Hopefully other fans and readers would like to see those same things, and we can deliver it and make everyone involved—the writers, the publisher, the advertisers—happy. It’s like writing a book and getting the feeling when someone you’ve never seen before buys your stuff and presents it to you for a signature. As an author, unless you’re a genuine ass, you truly are grateful people have chosen to spend their hard earned coin on your books.

By what we’re doing, I want people to see we get it. For instance, I want to see fans of Reed Farrel Coleman pick up the first issue because he’s in it. I want completists of his Moe Prager series to pick it up because there’s a brand new Moe Prager story illustrated by Reed’s son. I want people to write in and tell me they were fascinated by the history of short crime fiction in the back where I give some background on what the pulps did when Hammett and Chandler left, and then introduce Frederick Nebel’s first Donahue story, the series that replaced the Continental Op in Black Mask.

In fact, the only non-series related story in the issue is Tommy Pluck’s. The rest are all to one degree or another series stories by their authors. Terrence McCauley wrote a Universitystory for me. He’s got a series there with legs and there’s all sorts of room for novels and short stories in the universe he’s created. But the same is true of everyone in the issue. My primary goal is to get the thing out there, get it reviewed, and get feedback to see how much of it people get. Bottom line, all they gotta do is like it.

You've obtained a dynamic line up of writers for the first issue, including Terrence McCauley, Eric Beetner, Reed Farrel Coleman, and others. How did you manage to snag these terrific writers?

You've obtained a dynamic line up of writers for the first issue, including Terrence McCauley, Eric Beetner, Reed Farrel Coleman, and others. How did you manage to snag these terrific writers?In short, I asked them. It wasn’t any harder than that. Once you decide on doing a magazine, you have to figure out how you’re going to fill the first issue. If you rely only on submissions, you have no idea if you’re going to get gold or charcoal—are you going to get a wonderful writer’s best work, or the unsold piece sitting at the bottom of their steamer trunk for fifteen years.

The best way to avoid the problem, I reckoned, was to invite people I knew would give me great stories. I’ve worked with almost all of them before, many of whom will also be in an anthology called Blood Work, which Down & Out Books will publish next summer (it’s a tribute to the late bookseller Gary Shulze).

Going ahead, we’ve got Bill Crider with a new Sheriff Dan Rhodes story as the feature for Issue #2. I’m going through submissions slowly but surely, still working with people I’ve invited. I think, hopefully, going forward it’s the way I’d like to move ahead.

The featured story author for Issue #3 is probably set, but I can’t reveal their identity yet. Plus, I’ve been talking to a number of other writers who have told me yes, but without confirming later. With a quarterly magazine there’s not a mad rush, though we would like to go bi-monthly once we can handle the flow.

When are you going to send me a story?

What can readers expect from Down & Out: The Magazine in future issues?

If everything works in Issue #1, more of the same. Once it gets out to the masses in big numbers, reader feedback will tell us a lot, I hope. We’ll still have a big name feature story with the author’s series character (one of them anyway), there’ll still be a column by J. Kingston Pierce (late of Kirkus Reviews) though it may not always be a review column, and there will be another history of short crime fictionpiece by one of the old guys and gals, without whom we wouldn’t have what we do today.

We hope to have our subscription program ready for people before Issue #2 is ready for press, Peter Rozofsky will be our regular cover photographer, and while there might be a few other surprises, a move to bi-monthly at some point would be nice. And I’ve been mulling over the idea of a possible themed issue somewhere down the line. Possibly a letters column if I think it might be interesting for people to read. We’ll have to see, won’t we?

******** Thanks to Rick Ollerman for taking the time to chat. Be sure to check out the special collection of his introductions, Hardboiled, Noir and Gold Medals: Essays on Crime Fiction Writers from the 50s through the 90s...Due out August 4, 2017…

FOR MORE ABOUT RICK OLLERMAN CLICK HERE

HARDBOILED, NOIR, AND GOLD MEDALS ESSAYS ON CRIME FICTION WRITERSFROM THE 50s THROUGH THE 90s Rick Ollerman has been writing introductions for Stark House Press for the past six years. This book collects all those essays, plus includes a lot of new material written specifically for this book. Rick Ollerman's detailed critical essays, written about both modern and classic crime writers, have an electric-charged verve so brilliant the modern reader is compelled to develop a new understanding, a new appreciation, even a new witnessing of the writers and their most important and influential works. The context is always truthful to the era of creation, but it is fully developed with a modern understanding that brings new revelation to seemingly old topics. Which is a hard way of saying, Mr. Ollerman writes about crime fiction and its crafters brilliantly. -—Benjamin Boulden, critic/essayist An introduction by Rick Ollerman is always a promise of insightful, informative, and entertaining details about the author or topic. His essays are as valuable as the restored fiction that follows. —Alan Cranis, Bookgasm Reading one of Rick Ollerman's essays is like sitting in a master class on the writer. Having all of the essays in one collection is like getting a master's degree. This is an important book and a must-have for anybody who cares about good criticism, about the writers discussed, and about crime fiction in general. —Bill Crider, mystery author

HARDBOILED, NOIR, AND GOLD MEDALS ESSAYS ON CRIME FICTION WRITERSFROM THE 50s THROUGH THE 90s Rick Ollerman has been writing introductions for Stark House Press for the past six years. This book collects all those essays, plus includes a lot of new material written specifically for this book. Rick Ollerman's detailed critical essays, written about both modern and classic crime writers, have an electric-charged verve so brilliant the modern reader is compelled to develop a new understanding, a new appreciation, even a new witnessing of the writers and their most important and influential works. The context is always truthful to the era of creation, but it is fully developed with a modern understanding that brings new revelation to seemingly old topics. Which is a hard way of saying, Mr. Ollerman writes about crime fiction and its crafters brilliantly. -—Benjamin Boulden, critic/essayist An introduction by Rick Ollerman is always a promise of insightful, informative, and entertaining details about the author or topic. His essays are as valuable as the restored fiction that follows. —Alan Cranis, Bookgasm Reading one of Rick Ollerman's essays is like sitting in a master class on the writer. Having all of the essays in one collection is like getting a master's degree. This is an important book and a must-have for anybody who cares about good criticism, about the writers discussed, and about crime fiction in general. —Bill Crider, mystery author;

Published on August 03, 2017 23:31

HARDBOILED AND COVERED IN NOIR—PART ONE

HARDBOILED AND COVERED IN NOIR—PART ONE

HARDBOILED AND COVERED IN NOIR—PART ONE Rick Ollerman is a force to be reckoned with—master skydiver, world record holder, columnist, essayist, editor, author, and expert on the hardboiled and noir genres. His critically lauded and entertaining introductions for many of Stark House Press’ reprints of classic crime novels have provided new insights into the authors behind the brass knuckles and darkly twisted dames. Now, Stark House has collected these introductions, along with several new essays, in Hardboiled, Noir and Gold Medals: Essays on Crime Fiction Writers from the 50s through the 90s—a must read for every true fan of stylish fiction.

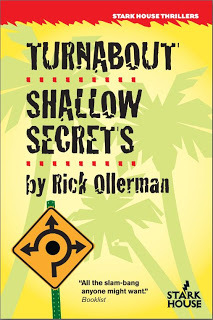

Rick’s writing brings the subjects of his focus to life in engaging and informative fashion. The drive of his narrative is compelling, setting the reader up in high anticipation of the stories to follow. The gestalt of each overview adds a depth and context to an author and his works, which alone is worth the price of admission. Rick has written four novels (

Turnabout

,

Shallow Secrets

,

Truth Always Kills

,

Mad Dog Barked

) set in the hash heat and dirty secrets behind the Florida sunshine. Rick has been coerced into stepping under the bright lights of the interrogation room to spill the secrets behind his works...********If your life took a turn for the noir and you found yourself on the run from the police and the mobster boyfriend of the dame running with you, what details would be included in an all-points bulletin?

Rick’s writing brings the subjects of his focus to life in engaging and informative fashion. The drive of his narrative is compelling, setting the reader up in high anticipation of the stories to follow. The gestalt of each overview adds a depth and context to an author and his works, which alone is worth the price of admission. Rick has written four novels (

Turnabout

,

Shallow Secrets

,

Truth Always Kills

,

Mad Dog Barked

) set in the hash heat and dirty secrets behind the Florida sunshine. Rick has been coerced into stepping under the bright lights of the interrogation room to spill the secrets behind his works...********If your life took a turn for the noir and you found yourself on the run from the police and the mobster boyfriend of the dame running with you, what details would be included in an all-points bulletin?

If that were really the case I’d try to point the people looking for me to a three foot midget with long hair, platform shoes and an eye patch, but I don’t think that’s what you’re going for. I’m a shade over six feet tall, about 180 pounds, I have no idea what my eye color is and, although I know my real age, it seems up for debate. I was picking up some copies of DVDs made from VHS tapes provided by Harry Whittington’s estate, and the guy who did the work asked if I was in my late thirties or early forties. Late thirties, he finally decided. On the other hand, I did a Noir @ the Bar in Austin after last year’s Bouchercon and I went into a Schlotzsky’s sandwich shop. The guy behind the register said he didn’t think I quite qualified for the senior discount, but he’d help me out. I was so excited to have finally found a Schlotzsky’s again it took a minute to register what he’d said. After being flustered and drooling on myself for a minute, I asked him just how old he thought I was. He told me he was really good at this and he guessed a number younger than I was but still much higher than the upper thirties from the DVD guy. Well, I thought automatically, I’ll show this guy how good he is, and I told him I was seven years older than his guess. Then I walked away to one of those magic Coke machines, the ones where you can pick all the unusual flavors and mix and match until you get something truly disgusting, and thought, Wow, what the hell did I just do? So clearly, in answer to your original question, the best thing I could possibly do would be to go to my nearest sandwich shop, take out my teeth, gum a grilled cheese sandwich and some cottage cheese, yell at children, then call 911 and surrender. What were your earliest reading influences? The first one had to be the Sunday paper. They would publish this comic strip each week and feature a letter of the alphabet. I’d cut each of those out as soon as they’d come out and then go over them again and again until the next one came. After a while, it seems I’d learned to read.

If that were really the case I’d try to point the people looking for me to a three foot midget with long hair, platform shoes and an eye patch, but I don’t think that’s what you’re going for. I’m a shade over six feet tall, about 180 pounds, I have no idea what my eye color is and, although I know my real age, it seems up for debate. I was picking up some copies of DVDs made from VHS tapes provided by Harry Whittington’s estate, and the guy who did the work asked if I was in my late thirties or early forties. Late thirties, he finally decided. On the other hand, I did a Noir @ the Bar in Austin after last year’s Bouchercon and I went into a Schlotzsky’s sandwich shop. The guy behind the register said he didn’t think I quite qualified for the senior discount, but he’d help me out. I was so excited to have finally found a Schlotzsky’s again it took a minute to register what he’d said. After being flustered and drooling on myself for a minute, I asked him just how old he thought I was. He told me he was really good at this and he guessed a number younger than I was but still much higher than the upper thirties from the DVD guy. Well, I thought automatically, I’ll show this guy how good he is, and I told him I was seven years older than his guess. Then I walked away to one of those magic Coke machines, the ones where you can pick all the unusual flavors and mix and match until you get something truly disgusting, and thought, Wow, what the hell did I just do? So clearly, in answer to your original question, the best thing I could possibly do would be to go to my nearest sandwich shop, take out my teeth, gum a grilled cheese sandwich and some cottage cheese, yell at children, then call 911 and surrender. What were your earliest reading influences? The first one had to be the Sunday paper. They would publish this comic strip each week and feature a letter of the alphabet. I’d cut each of those out as soon as they’d come out and then go over them again and again until the next one came. After a while, it seems I’d learned to read.

Then I’d haunt the library. There was the patch of woods, then a short cut through the cemetery and the little league fields, down the hill, and finally the library in Simsbury, CT. The Hardy Boys, Alfred Hitchcock and the Three Investigators, the usual suspects. Then for some reason (probably reports for school), I became a fan of biographies. As I grew up, I followed the fairly typical path of science fiction to crime fiction, then to bestsellers and classics, back to crime, then to the discovery of classic crime fiction. But always a bit of everything. What books or authors were your introduction to the hardboiled and noir genres? That’s a tough question. It probably has to do with reprint paperbacks of The Avenger, The Shadowand Doc Savage. I’d pick those up wherever I could find them. They were exciting and fresh, even though they were old, if that makes sense. And if they were old, there had to be similar things between what was written back then and what was being written now, which might be even better, right? My mother would also pull me along when she went to estate sales in Minneapolis. She didn’t want to go alone and no one else wanted to go with her. She could turn me loose and I’d haunt the places for their books, and if I found something interesting, I’d try to talk her into ponying up, which she often would. I picked up a few things this way, most of which I’ve forgotten, but one book I still have, which is an Edgar Allan Poe collection. There’s nothing like reading The Raven aloud for the first time. For me, old didn’t mean old as in over with, it meant old as in ready to be rediscovered. Somewhere in there came The Maltese Falcon with all its brilliant dialogue, and the quintessential noir, James M. Cain’s The Postman Always Rings Twice, which to this day is the book I tell people is the answer to their question, What is noir? Anyway, the more I found, the more I kept wanting to find more. What was it about hardboiled crime stories and the darkness of noir that developed your obsessions with the genres? In all fiction, characters and plot are intertwined to make worthwhile books, but in the hardboiled and noir genres, voicebecomes really critical to the reading experience. Take Lou Ford’s voice out of The Killer Inside Me, and Jim Thompson’s book becomes a completely different story. Adding all three of these things in a crime setting can be an extremely heady and intoxicating mix. Many of the character in hardboiled and noir books have over-developed or under-developed moral codes, and those are interesting enough, but what can be even more interesting are the characters who exist in the grey in-between. I have a character in Truth Always Kills where I dump impossible choice upon impossible choice on him, and he almost can’t help himself from doing what he knows is right even though these decisions often have very grave consequences for himself and those around him.

Then I’d haunt the library. There was the patch of woods, then a short cut through the cemetery and the little league fields, down the hill, and finally the library in Simsbury, CT. The Hardy Boys, Alfred Hitchcock and the Three Investigators, the usual suspects. Then for some reason (probably reports for school), I became a fan of biographies. As I grew up, I followed the fairly typical path of science fiction to crime fiction, then to bestsellers and classics, back to crime, then to the discovery of classic crime fiction. But always a bit of everything. What books or authors were your introduction to the hardboiled and noir genres? That’s a tough question. It probably has to do with reprint paperbacks of The Avenger, The Shadowand Doc Savage. I’d pick those up wherever I could find them. They were exciting and fresh, even though they were old, if that makes sense. And if they were old, there had to be similar things between what was written back then and what was being written now, which might be even better, right? My mother would also pull me along when she went to estate sales in Minneapolis. She didn’t want to go alone and no one else wanted to go with her. She could turn me loose and I’d haunt the places for their books, and if I found something interesting, I’d try to talk her into ponying up, which she often would. I picked up a few things this way, most of which I’ve forgotten, but one book I still have, which is an Edgar Allan Poe collection. There’s nothing like reading The Raven aloud for the first time. For me, old didn’t mean old as in over with, it meant old as in ready to be rediscovered. Somewhere in there came The Maltese Falcon with all its brilliant dialogue, and the quintessential noir, James M. Cain’s The Postman Always Rings Twice, which to this day is the book I tell people is the answer to their question, What is noir? Anyway, the more I found, the more I kept wanting to find more. What was it about hardboiled crime stories and the darkness of noir that developed your obsessions with the genres? In all fiction, characters and plot are intertwined to make worthwhile books, but in the hardboiled and noir genres, voicebecomes really critical to the reading experience. Take Lou Ford’s voice out of The Killer Inside Me, and Jim Thompson’s book becomes a completely different story. Adding all three of these things in a crime setting can be an extremely heady and intoxicating mix. Many of the character in hardboiled and noir books have over-developed or under-developed moral codes, and those are interesting enough, but what can be even more interesting are the characters who exist in the grey in-between. I have a character in Truth Always Kills where I dump impossible choice upon impossible choice on him, and he almost can’t help himself from doing what he knows is right even though these decisions often have very grave consequences for himself and those around him.

I write about a private eye in Mad Dog Barked where his moral compass points more toward the ends justify the means star, but he tries not to push the boundaries that much. Even though, he slices the pie thin enough to do the right thing, even at certain costs to himself, he’s arrogant enough he won’t let those around him see it, or help him through it. And that’s assuming he can even admit it to himself. I’m not sure how these sorts of characters would have been possible for me to write without the background in hardboiled and noir literature. They make me strive harder for the voice, work harder for the non-cookie cutter characters—I certainly don’t want to give you the feeling of having been there, done that, or being able to guess the ending or solve the mystery ahead of the book—and most of all, I try to provide the same breathless level of entertainment readers used to get from the days of the old paperback originals. The books are longer now, but I often get remarks by readers saying they couldn’t put the books down. That’s perfect. It reminds me of someone like Harry Whittington, who when he was on, would have you turning pages as fast as you could so you could finally let out the breath you didn’t know you’d been holding. You’ve cited Randy Wayne White and Ed Gorman as early mentors. How did you meet them and how did their encouragement and guidance shape you as a writer?

I write about a private eye in Mad Dog Barked where his moral compass points more toward the ends justify the means star, but he tries not to push the boundaries that much. Even though, he slices the pie thin enough to do the right thing, even at certain costs to himself, he’s arrogant enough he won’t let those around him see it, or help him through it. And that’s assuming he can even admit it to himself. I’m not sure how these sorts of characters would have been possible for me to write without the background in hardboiled and noir literature. They make me strive harder for the voice, work harder for the non-cookie cutter characters—I certainly don’t want to give you the feeling of having been there, done that, or being able to guess the ending or solve the mystery ahead of the book—and most of all, I try to provide the same breathless level of entertainment readers used to get from the days of the old paperback originals. The books are longer now, but I often get remarks by readers saying they couldn’t put the books down. That’s perfect. It reminds me of someone like Harry Whittington, who when he was on, would have you turning pages as fast as you could so you could finally let out the breath you didn’t know you’d been holding. You’ve cited Randy Wayne White and Ed Gorman as early mentors. How did you meet them and how did their encouragement and guidance shape you as a writer?

I met Randy along with Peter Mattiessen at a writers’ retreat in the Everglades a long time ago, after Randy’s third book (under his own name) was published. Peter, a wonderful man who was really a terror behind the wheel of a car, said extremely encouraging things about my writing. Over the course of the long weekend, I’d also received positive feedback from every one of the attendees. This was very important to me as a young writer. We probably all have those moments, those times where you’ve gone to conferences, you’ve studied ad nauseaum, you’ve read books—some you agree with (Lawrence Block, for me), others you don’t (most of the rest)—and it comes time you just feel you must sit down and grind it out. There’s nothing else to do. It’s now or never. The next stage in learning how to write a novel is by writing a novel, otherwise it’s all repeat. Randy pulled me aside one day at lunch and asked me where I wanted to go with my writing. At the time, he had taken the place of Tim Cahill in Outside magazine, and I was a huge fan. He wasn’t yet publicly acknowledging the two series he’d written earlier under two different pseudonyms, and he told me he had switched to the first person perspective for his fourth book in his Doc Ford series. I asked him how he liked it, and he said he was finding it easier. Anyway, I told him basically I wanted to be him. I wanted to write non-fiction pieces with the same touches of humor and humanity he and Cahill were known for, and while I personally found his third Doc Ford book a bit off, his first two, Sanibel Flats and The Heat Islands, are breathtaking examples of what’s come to be recognized as the Florida book or genre. He gave me his two private numbers and told me he’d do anything he could to help, except for one thing—he wouldn’t read a manuscript. He wouldn’t read any Florida writer’s manuscript for concern of becoming tainted. So I went home and started a novel. I called him once, when I was about ten thousand words in, mainly because I didn’t want to lose touch. I told him where I was and he said, “Oh, don’t worry. In my experience, once you hit ten thousand words you’ll finish the book.” And that was it. Afterward, I pretty much let it go. I kept going to conferences in Florida and see Randy surrounded by the same couple of people. I thought to myself, I don’t want to be one of those guys. As a result, I kept my distance. Randy went on to become a bestseller, I was never a groupie, and Randy probably doesn’t remember me even a little.

I met Randy along with Peter Mattiessen at a writers’ retreat in the Everglades a long time ago, after Randy’s third book (under his own name) was published. Peter, a wonderful man who was really a terror behind the wheel of a car, said extremely encouraging things about my writing. Over the course of the long weekend, I’d also received positive feedback from every one of the attendees. This was very important to me as a young writer. We probably all have those moments, those times where you’ve gone to conferences, you’ve studied ad nauseaum, you’ve read books—some you agree with (Lawrence Block, for me), others you don’t (most of the rest)—and it comes time you just feel you must sit down and grind it out. There’s nothing else to do. It’s now or never. The next stage in learning how to write a novel is by writing a novel, otherwise it’s all repeat. Randy pulled me aside one day at lunch and asked me where I wanted to go with my writing. At the time, he had taken the place of Tim Cahill in Outside magazine, and I was a huge fan. He wasn’t yet publicly acknowledging the two series he’d written earlier under two different pseudonyms, and he told me he had switched to the first person perspective for his fourth book in his Doc Ford series. I asked him how he liked it, and he said he was finding it easier. Anyway, I told him basically I wanted to be him. I wanted to write non-fiction pieces with the same touches of humor and humanity he and Cahill were known for, and while I personally found his third Doc Ford book a bit off, his first two, Sanibel Flats and The Heat Islands, are breathtaking examples of what’s come to be recognized as the Florida book or genre. He gave me his two private numbers and told me he’d do anything he could to help, except for one thing—he wouldn’t read a manuscript. He wouldn’t read any Florida writer’s manuscript for concern of becoming tainted. So I went home and started a novel. I called him once, when I was about ten thousand words in, mainly because I didn’t want to lose touch. I told him where I was and he said, “Oh, don’t worry. In my experience, once you hit ten thousand words you’ll finish the book.” And that was it. Afterward, I pretty much let it go. I kept going to conferences in Florida and see Randy surrounded by the same couple of people. I thought to myself, I don’t want to be one of those guys. As a result, I kept my distance. Randy went on to become a bestseller, I was never a groupie, and Randy probably doesn’t remember me even a little.

As for Ed Gorman, you don’t have to go far to find people who haven’t praised him for his support and friendship above and beyond over the years. When he passed away a couple of years ago, his loss sent ripples through the community. And although I spoke at his funeral, I never actually met him. When I got to the service, I thought I might be the only one in that situation, but it turns out it wasn’t the case. I knew Ed didn’t like to travel, but I had no idea he didn’t even like to get in an elevator.

As for Ed Gorman, you don’t have to go far to find people who haven’t praised him for his support and friendship above and beyond over the years. When he passed away a couple of years ago, his loss sent ripples through the community. And although I spoke at his funeral, I never actually met him. When I got to the service, I thought I might be the only one in that situation, but it turns out it wasn’t the case. I knew Ed didn’t like to travel, but I had no idea he didn’t even like to get in an elevator.

I first discovered Ed through his blog. It was a wonderful source of information for a newcomer to the paperback original world like me. A few years later, I remembered Ed had mentioned two unpublished manuscripts by the late, great Peter Rabe, and I got hold of him and the manuscripts through Stark House Press (I wrote about this in my new non-fiction collection). I was able to edit these and see them through to publication—a terrific project. For so reason, Ed took an interest in my career. He began writing nice things about me, at one point saying in his opinion my first book, Turnabout, should have been nominated for the Edgar award as Best First Novel. A bit ridiculous, I thought, but a beautiful gesture on behalf of Ed. Later, he requested, through Stark House, I write an essay to introduce a pair of his books they were reprinting. Again, I wrote about this in my new collection so I won’t repeat it all here, but he sent me an e-mail thanking me heartily, telling me this was a piece he could show his grandchildren. It was one of those few occasions where you have visceral proof the words you sometimes wield have actual power on people. You had some tough health experiences forcing you to stop writing for an extended period. Has that affected your writing in the long run—for better or worse—and if so, how? Oh, man. That’s actually a difficult thing when you read it—as opposed to BS about it in person—and it’s hard to write about. Hmm.

I first discovered Ed through his blog. It was a wonderful source of information for a newcomer to the paperback original world like me. A few years later, I remembered Ed had mentioned two unpublished manuscripts by the late, great Peter Rabe, and I got hold of him and the manuscripts through Stark House Press (I wrote about this in my new non-fiction collection). I was able to edit these and see them through to publication—a terrific project. For so reason, Ed took an interest in my career. He began writing nice things about me, at one point saying in his opinion my first book, Turnabout, should have been nominated for the Edgar award as Best First Novel. A bit ridiculous, I thought, but a beautiful gesture on behalf of Ed. Later, he requested, through Stark House, I write an essay to introduce a pair of his books they were reprinting. Again, I wrote about this in my new collection so I won’t repeat it all here, but he sent me an e-mail thanking me heartily, telling me this was a piece he could show his grandchildren. It was one of those few occasions where you have visceral proof the words you sometimes wield have actual power on people. You had some tough health experiences forcing you to stop writing for an extended period. Has that affected your writing in the long run—for better or worse—and if so, how? Oh, man. That’s actually a difficult thing when you read it—as opposed to BS about it in person—and it’s hard to write about. Hmm.

First, the health issues are not over, and they may never be. To quote the doctors at Dartmouth-Hitchcock up here in New Hampshire, “Medicine is very good at telling you what you don’t have. You don’t have [insert large list here]. We don’t know what you do have. In the meantime, all we can do is treat your symptoms.” This is not what you want to hear from your doctors. You want a problem. You want a cure. You want a recovery. You want your life back. Sometimes, however, they won’t give it to you. I had finished writing my first book, and I thought it was okay. There had been some publishing interest—one editor told me it was publishable, but she didn’t like how I’d taken an ordinary guy, messed up his life, then let him get things back to normal. This was back in the day when all male protagonists had to be alcoholic Vietnam vets who had become cops and accidentally killed a young child/allowed a young child to be killed while on duty. Another one read the synopsis and sample chapters and had her secretary request the full manuscript via FedEx. I sent it, but didn’t hear back from her. Everyone tells me this means she lost it, which happens, but I never followed up. Why, you ask? Because I had time. I’d started another book, and the only thing you can control in this business is the writing. If you try to sell, sell, sell all the time, when would you write? Meanwhile, in theory, with each book you get better, cream would rise, etc., etc. Just don’t get sick.

First, the health issues are not over, and they may never be. To quote the doctors at Dartmouth-Hitchcock up here in New Hampshire, “Medicine is very good at telling you what you don’t have. You don’t have [insert large list here]. We don’t know what you do have. In the meantime, all we can do is treat your symptoms.” This is not what you want to hear from your doctors. You want a problem. You want a cure. You want a recovery. You want your life back. Sometimes, however, they won’t give it to you. I had finished writing my first book, and I thought it was okay. There had been some publishing interest—one editor told me it was publishable, but she didn’t like how I’d taken an ordinary guy, messed up his life, then let him get things back to normal. This was back in the day when all male protagonists had to be alcoholic Vietnam vets who had become cops and accidentally killed a young child/allowed a young child to be killed while on duty. Another one read the synopsis and sample chapters and had her secretary request the full manuscript via FedEx. I sent it, but didn’t hear back from her. Everyone tells me this means she lost it, which happens, but I never followed up. Why, you ask? Because I had time. I’d started another book, and the only thing you can control in this business is the writing. If you try to sell, sell, sell all the time, when would you write? Meanwhile, in theory, with each book you get better, cream would rise, etc., etc. Just don’t get sick.

There was a problem with the heel of my left foot. It got so bad I couldn’t put weight on it while I was walking during my IT day job. I ended up having two surgeries on my heel before I realized it was really my back causing the problem. I was referred to a doctor for some injections into my back. The first two didn’t help, and I almost didn’t go back for the third. We went to him because he had a fluoroscope. I couldn’t understand how it could help when it was more or less behind him, and then when he punctured my dura mater, I lost all feeling from my waist down, and things got worse. He knew what he’d done, but he didn’t tell me. Some feeling came back after a while, but unbeknownst to me the cerebrospinal fluid continued to leak. This is the stuff, which among other things, keeps your brain floating in your skull. Two days later, I couldn’t be upright, the pain was so bad. They call them spinal headaches, but they are so much worse than anything with the label headache. I did try to drive the fifty miles to my office the next day because I’m an idiot, but I was screaming when I got there. I dove to the floor, told the first person who found me I was going home, then drove all the way back, literally screaming. It burned out my throat but it actually helped the pain. It was eight months before I could walk for longer than a few seconds. I worked with a laptop on my stomach while I lay on a fold out bed, largely unable to sleep. I went through several repair procedures (which didn’t work), several diagnostic procedures (which found nothing), and just outlasted it. When that was done, I had a whole new set of symptoms. I’ll stop there before I move into fifteen years or so of Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (now about to be promoted to a disease), chronic Lyme disease, etc. When I was still working in IT there was a time when I had to write down everything I worked on, and what I did, or I either wouldn’t remember it or would jumble it together. We had a vice-president who would come in and tell me how brave I was, and every time I would tell her this wasn’t bravery—bravery involved a choice of doing something with risk to potentially benefit another party. What I was going through was a series of really bad breaks—or maybe I’d stepped on too many ants in a previous life or something. But no, I couldn’t write at all during this period. I couldn’t hold anything in my head long enough to make sense of anything. Interestingly enough, when I finally did get back to writing, I came back better than I had been. The learning curve I needed to go through, and had gone through, was over and didn’t need to be repeated. There are things you have to learn when you begin writing, which have nothing to do with the book. Now all those things weren’t even a question mark, which was a relief more than a benefit.********In Hardboiled And Covered In Noir—Part Two, Rick will delve into the art of essay writing and why the past should always be with us...

There was a problem with the heel of my left foot. It got so bad I couldn’t put weight on it while I was walking during my IT day job. I ended up having two surgeries on my heel before I realized it was really my back causing the problem. I was referred to a doctor for some injections into my back. The first two didn’t help, and I almost didn’t go back for the third. We went to him because he had a fluoroscope. I couldn’t understand how it could help when it was more or less behind him, and then when he punctured my dura mater, I lost all feeling from my waist down, and things got worse. He knew what he’d done, but he didn’t tell me. Some feeling came back after a while, but unbeknownst to me the cerebrospinal fluid continued to leak. This is the stuff, which among other things, keeps your brain floating in your skull. Two days later, I couldn’t be upright, the pain was so bad. They call them spinal headaches, but they are so much worse than anything with the label headache. I did try to drive the fifty miles to my office the next day because I’m an idiot, but I was screaming when I got there. I dove to the floor, told the first person who found me I was going home, then drove all the way back, literally screaming. It burned out my throat but it actually helped the pain. It was eight months before I could walk for longer than a few seconds. I worked with a laptop on my stomach while I lay on a fold out bed, largely unable to sleep. I went through several repair procedures (which didn’t work), several diagnostic procedures (which found nothing), and just outlasted it. When that was done, I had a whole new set of symptoms. I’ll stop there before I move into fifteen years or so of Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (now about to be promoted to a disease), chronic Lyme disease, etc. When I was still working in IT there was a time when I had to write down everything I worked on, and what I did, or I either wouldn’t remember it or would jumble it together. We had a vice-president who would come in and tell me how brave I was, and every time I would tell her this wasn’t bravery—bravery involved a choice of doing something with risk to potentially benefit another party. What I was going through was a series of really bad breaks—or maybe I’d stepped on too many ants in a previous life or something. But no, I couldn’t write at all during this period. I couldn’t hold anything in my head long enough to make sense of anything. Interestingly enough, when I finally did get back to writing, I came back better than I had been. The learning curve I needed to go through, and had gone through, was over and didn’t need to be repeated. There are things you have to learn when you begin writing, which have nothing to do with the book. Now all those things weren’t even a question mark, which was a relief more than a benefit.********In Hardboiled And Covered In Noir—Part Two, Rick will delve into the art of essay writing and why the past should always be with us... FOR MORE ABOUT RICK OLLERMAN CLICK HERE

HARDBOILED, NOIR, AND GOLD MEDALS: ESSAYS ON CRIME FICTION WRITERS FROM THE 50s THROUGH THE 90s Rick Ollerman has been writing introductions for Stark House Press for the past six years. This book collects all those essays, plus includes a lot of new material written specifically for this book. Rick Ollerman's detailed critical essays, written about both modern and classic crime writers, have an electric-charged verve so brilliant the modern reader is compelled to develop a new understanding, a new appreciation, even a new witnessing of the writers and their most important and influential works. The context is always truthful to the era of creation, but it is fully developed with a modern understanding that brings new revelation to seemingly old topics. Which is a hard way of saying, Mr. Ollerman writes about crime fiction and its crafters brilliantly. -—Benjamin Boulden, critic/essayist An introduction by Rick Ollerman is always a promise of insightful, informative, and entertaining details about the author or topic. His essays are as valuable as the restored fiction that follows. —Alan Cranis, Bookgasm Reading one of Rick Ollerman's essays is like sitting in a master class on the writer. Having all of the essays in one collection is like getting a master's degree. This is an important book and a must-have for anybody who cares about good criticism, about the writers discussed, and about crime fiction in general. —Bill Crider, mystery author

HARDBOILED, NOIR, AND GOLD MEDALS: ESSAYS ON CRIME FICTION WRITERS FROM THE 50s THROUGH THE 90s Rick Ollerman has been writing introductions for Stark House Press for the past six years. This book collects all those essays, plus includes a lot of new material written specifically for this book. Rick Ollerman's detailed critical essays, written about both modern and classic crime writers, have an electric-charged verve so brilliant the modern reader is compelled to develop a new understanding, a new appreciation, even a new witnessing of the writers and their most important and influential works. The context is always truthful to the era of creation, but it is fully developed with a modern understanding that brings new revelation to seemingly old topics. Which is a hard way of saying, Mr. Ollerman writes about crime fiction and its crafters brilliantly. -—Benjamin Boulden, critic/essayist An introduction by Rick Ollerman is always a promise of insightful, informative, and entertaining details about the author or topic. His essays are as valuable as the restored fiction that follows. —Alan Cranis, Bookgasm Reading one of Rick Ollerman's essays is like sitting in a master class on the writer. Having all of the essays in one collection is like getting a master's degree. This is an important book and a must-have for anybody who cares about good criticism, about the writers discussed, and about crime fiction in general. —Bill Crider, mystery author

Published on August 03, 2017 17:50

July 29, 2017

THE APES HAVE IT

THE APES HAVE IT

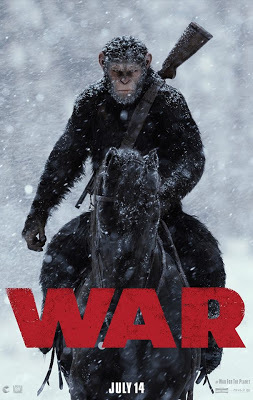

THE APES HAVE ITWar for the Planet of the Apes may not be the best movie I've seen all year, but I have to admit it's close. It is certainly the only 'summer blockbuster,' other than the reigning queen of action Wonder Woman, to fully deliver on its premise and promise.

Combining breathtaking special effects, fantastic costuming, amazing performances from Andy Serkis (Caesar), Steve Zahn (Bad Ape), and newcomer Ahmia Miller (Nova), and a powerful, poignant narrative, War for the Planet of the Apes concludes this rebooted trilogy on a powerful-and truly blockbuster-bang.

With its allusions to Shakespeare, Joseph Conrad, the Bible, American slavery, and the civil-rights movement, War may not be subtle in presenting its ethical dilemmas, but it's ultimate proof summer sequels and blockbusters don't have to be brain-dead, time wasting, exercises in futility.

On a final note, I can't say enough about the performance of Andy Serkis in the lead role of Caesar, the ape whose display of intelligence, emotion, and 'humanity' is Oscar worthy.

Published on July 29, 2017 11:46

BRIT SPY—COMMANDER SHAW

BRIT SPY—COMMANDER SHAW

BRIT SPY—COMMANDER SHAW

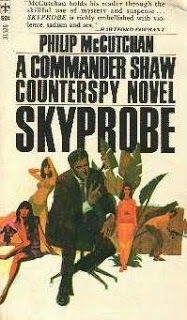

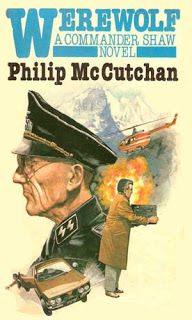

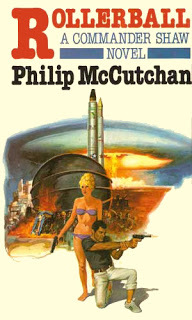

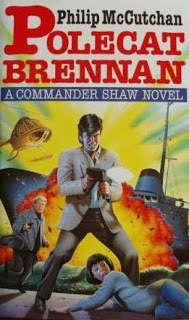

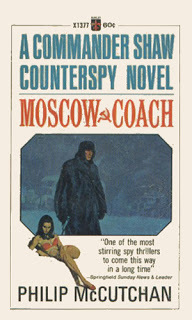

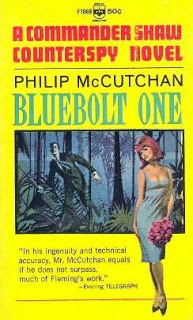

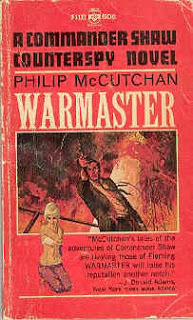

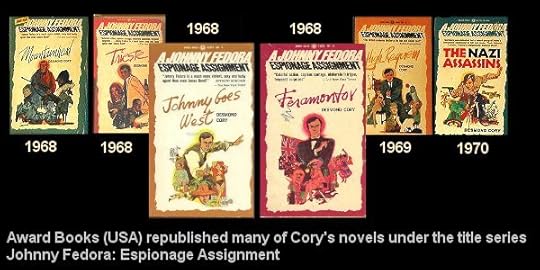

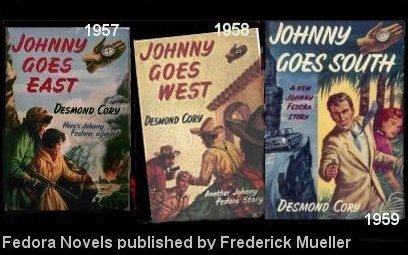

From 1960 to 1995, British Navy Commander Esmond Shaw carried out daring missions against larger than life villains as an agent of Britain’s shadowy Intelligence organization known as 6D2. While sharing the same rank as his much better known counterpart, Commander James Bond, Shaw deserves to be read and remembered in his own right. However, the novels detailing the adventures of the resourceful and debonair Shaw are definitely in the realm of Fleming’s spy fiction, as opposed to the darker espionage fiction of LeCarré.

From 1960 to 1995, British Navy Commander Esmond Shaw carried out daring missions against larger than life villains as an agent of Britain’s shadowy Intelligence organization known as 6D2. While sharing the same rank as his much better known counterpart, Commander James Bond, Shaw deserves to be read and remembered in his own right. However, the novels detailing the adventures of the resourceful and debonair Shaw are definitely in the realm of Fleming’s spy fiction, as opposed to the darker espionage fiction of LeCarré.

Shaw was the creation of prolific English author Philip McCutchan. After having served on various British war ships during WWII, McCutchan left the navy to concentrated on writing. During his career, he published more than 80 books, including fifteen books in his bestselling Halfhyde series of naval warfare adventures. In his first eight adventures, Shaw is assigned to the Special Services Division of Defence Intelligence. He’s the Admiralty’s go-to guy when action is need off the decks of sea bound ships. Eventually, Shaw becomes disillusioned and comes in out of the cold and quits. The inevitable spiral into alcohol and blondes and debauched behavior is brought to a halt when he reluctantly is brought back into the fold by 6D2, a highly classified branch of British Intelligence.

Shaw was the creation of prolific English author Philip McCutchan. After having served on various British war ships during WWII, McCutchan left the navy to concentrated on writing. During his career, he published more than 80 books, including fifteen books in his bestselling Halfhyde series of naval warfare adventures. In his first eight adventures, Shaw is assigned to the Special Services Division of Defence Intelligence. He’s the Admiralty’s go-to guy when action is need off the decks of sea bound ships. Eventually, Shaw becomes disillusioned and comes in out of the cold and quits. The inevitable spiral into alcohol and blondes and debauched behavior is brought to a halt when he reluctantly is brought back into the fold by 6D2, a highly classified branch of British Intelligence.

In Sunstrike, the 14th Shaw novel, Felicity Mandrake is assigned as Shaw’s secretary. Unlike, Bond’s Moneypenny (at least in the books), Felicity becomes Shaw’s partner, working alongside him in the field for the rest of the series. Shaw’s adversaries run the gamut of colorful (if standard) villains from Russian spies to fanatical terrorists both domestic and international. Shaw even had his own international criminal cartel to rival Specter, SMERSH, or THRUSH. The oddly initialed WUSWIPP—World Union of Socialist Scientific Workers for International Progress in Peace—like every other organization of their ilk was dedicated to total world domination through any nefarious plots, weapons of mass destructions, or government downfalls necessary.

In Sunstrike, the 14th Shaw novel, Felicity Mandrake is assigned as Shaw’s secretary. Unlike, Bond’s Moneypenny (at least in the books), Felicity becomes Shaw’s partner, working alongside him in the field for the rest of the series. Shaw’s adversaries run the gamut of colorful (if standard) villains from Russian spies to fanatical terrorists both domestic and international. Shaw even had his own international criminal cartel to rival Specter, SMERSH, or THRUSH. The oddly initialed WUSWIPP—World Union of Socialist Scientific Workers for International Progress in Peace—like every other organization of their ilk was dedicated to total world domination through any nefarious plots, weapons of mass destructions, or government downfalls necessary.