Kyle Fitzgibbons's Blog, page 3

May 10, 2017

Emailing a Student

I've recently had a student email about ten times regarding material completely independent of class. In fact, I don't even teach the student in one of my own classes. They just happen to know I like the topics they're interested in. I've been pretty direct in poking holes in their thinking and pointing out what I consider to be errors or lapses in understanding.

I've recently had a student email about ten times regarding material completely independent of class. In fact, I don't even teach the student in one of my own classes. They just happen to know I like the topics they're interested in. I've been pretty direct in poking holes in their thinking and pointing out what I consider to be errors or lapses in understanding.At the same time, I couldn't be more impressed by the intellectual charge they bring to the conversations and the genuine, obvious passion displayed for testing out beliefs to see how they hold up. In order to not focus solely on breaking down their beliefs and understandings, I wrote them the email below. I feel it's probably good for any student to read.

Teachers aren't all knowing and we rarely know much about what's important to the students themselves. They deserve to know that and be reminded as frequently as possible. We have to learn things just like them and that requires chasing down and tackling new knowledge and understanding actively and vigorously. Waiting for it in class is a non-starter. It may never come.

Hi,

I just want you to know how impressed I am with your curiosity and desire to understand the world, along with the school independent time you spend on it and willingness to ask questions and seek feedback. Any replies I’m giving you in no way mean to imply that you should discontinue, which I think is obvious and I don’t believe you are taking it as deflating. Keep asking questions, looking for answers, questioning the ones you get, and iterating. I’m only able to discuss these topics and provide feedback because that’s exactly what I’ve done myself.

I’ve never had a teacher in my life that taught me anything of real value. Everything I’ve learned of value has been learned on my own. I’ve read about 700 books entirely independent of school as a post-college adult (2009), about 80 per year the last 8 years or so. Reading those books, from quality sources, with intelligent authors, is a much better education than any graduate level, masters program course I’ve taken. Even the majority of professors you have in university will be very limited in their knowledge and not have much insight on topics that are personally interesting to you. I once had a professor with a Ph.D. in cultural studies who had never read Karl Marx! It was mind-blowing. I could not understand how you could talk about socialist theories without at least having a passing knowledge of Marx from first hand sources.

I’ve found philosophy, psychology, economics, and the other social sciences to be most interesting personally, so I’ve simply read a lot of the best thinkers in those genres. Thinkers who are globally recognized by others in the field as at or near the top of those fields. When you focus on the best thinkers in the field, you can see the bigger pictures, find holes in arguments, and also gain access to the best empirical evidence available. In doing that, I’ve personally read over 100 books in philosophy, economics, the sciences related to learning (psychology, sociology, neuroscience, psychiatry), health/fitness, and language acquisition each. Obviously reading 100 books in each category means there are literally thousands and thousands of book and pieces of information I don’t possess. That’s why focusing on quality of source material is so important. It tends to weed out the non-essential.

So keep it up. The only difference between today and five years from now will be the people you’ve talked to, the places you’ve visited, and the books you’ve read. So just read as many books as possible and talk to people of similar mind and interests, but who also have diverse perspectives and differing beliefs from you.

Regards,

Kyle

Published on May 10, 2017 23:12

May 9, 2017

Good Teachers Don’t Exist

Good teachers don’t exist.

Good teachers don’t exist.At least not in a meaningful way. This is largely semantic, but think about what would make a teacher a “good” teacher. How do you provide evidence that someone is a good teacher? One place to start would be with asking stakeholders. Which stakeholders matter in deciding it? School districts? Administration? Fellow teachers? Parents? Students? The teacher his or herself? All of the above?

All of the above would be too high a standard as no one would be a good teacher if all the stakeholders had to agree completely. So perhaps some percentage of the stakeholders? Is a simple majority of 51% enough? What if 90% of the administration, fellow teachers, and parents believe a person is a good teacher, but zero percent of the students do? Does the teacher still count as a good teacher? What if 100% of the students feel someone is a good teacher, but none of the adult stakeholders do?

This can get more complicated by a further step. What if all the stakeholders mentioned above agree someone is a good teacher using 51% as the percentage threshold in one location, but not another? If all stakeholders in a public, San Diego, suburban high school agree a person is a good teacher and he or she moves to a private, Beijing, urban high school and none of the stakeholders believe he or she is a good teacher, who is right? Is this another question of percentages? Do we need 51% of locales around the world to agree a person is a good teacher?

The above is premised on stakeholders having some kind of final say, but is that reasonable? Perhaps total societal welfare is a better metric. What if all the stakeholders mentioned above believed a person was not a good teacher, but total welfare in society actually goes up because of the person’s teaching? This might be seen in an example where a teacher focuses on creativity and innovation to the detriment of time spent on the standard curriculum. Perhaps the teacher is even fired for neglecting pre-written standards regarding math and language, but winds up sparking the next Facebook or Apple CEO. Would that teacher be a good teacher even though no one else recognizes them as such and actually lays them off?

All of the above conflicting goals and agendas makes it impossible to state categorically if a person is a good teacher. I have found that generally speaking, being a good teacher is simply a process of doing what one is told by administration while trying to make parents and students feel good. In terms of achieving a job description, that seems to work. Since that job description changes at each school, it looks different everywhere you go. Am I good teacher? I can’t tell you that. The strongest claim I can make is that I’ve never been fired or had any major problems. I don’t think my students hate me or my class, but maybe they’re just better poker players than I am. Some are definitely bored, but I would be too if I were forced to take an art class for example. It’s just not my cup of tea. To each their own.

Can I teach a particular subject well, say math or economics? That depends too. If you are interested, then sure. If you aren’t, it probably doesn’t matter. That differs from tutoring where essentially every student is “interested” in that they personally pay me and take the time to show up and listen. In a room of students, that isn’t the case. Some will listen and want to learn, others will look like they are, but aren’t, and still others will actively disengage altogether.

I have the impression that teachers tend to have an overinflated sense of themselves. I would argue there are very few good teachers, based on metrics that matter to me, but most teachers probably feel they are pretty good or above average. It’s the Lake Wobegon effect popping up.

In reality, most teachers could be replaced by the average caring adult and not be missed at all. The marginal effect of any one teacher is almost zero. I’d say it’s much more important to weed out potential problems from teaching than anything else. It’s much clearer that we can have truly bad teachers, ones that damage and harm students either physically or emotionally. The marginal effect in those cases is very high and very negative. It’s much less clear going the other direction.

So give me your thoughts. What makes a good teacher? Is it universalizable or always specifically context dependent? Is there any meaningful sense to the phrase?

Published on May 09, 2017 23:19

All Students Can Learn...

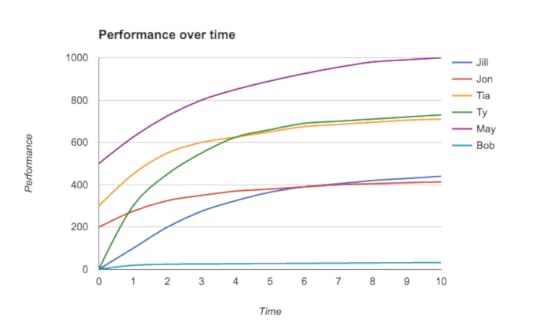

Above are six learning curves representing six hypothetical persons. You can see a variety of initial performance levels, going from 1 for Ty, Jill, and Bob at time 0, all the way up to 500 for May. You can also see a variety of ending performance levels, going from 33 at time 10 for Bob, all the way up to 1000 for May. All of the learning curves on the diagram above improve over time, as represented by increased performance over time and all have different rates of improvement over time.

Above are six learning curves representing six hypothetical persons. You can see a variety of initial performance levels, going from 1 for Ty, Jill, and Bob at time 0, all the way up to 500 for May. You can also see a variety of ending performance levels, going from 33 at time 10 for Bob, all the way up to 1000 for May. All of the learning curves on the diagram above improve over time, as represented by increased performance over time and all have different rates of improvement over time.The question I want to answer is, “Can all students can learn?” It depends. In the above learning curves, all students show improvement. However, that means almost nothing given the different rates of improvement and absolute performance levels over different time periods. In fact, the idea that growth rates or proficiency levels (performance levels) tell us anything at all is patently absurd once the above curves sink in.

Let’s start by measuring some growth rates. Bob (light blue curve) went from a performance level of 1 to a performance level of 33.

Bob’s percentage change = (33-1/1) x 100 = 3200%

We could also state that Bob is 33 times “better” at time 10 than he is at time 0. Either way, that’s a lot of improvement if we compare it to May (purple curve).

May’s percentage change = (1000-500/500) x 100 = 100%

We could also state that May is 2 times “better” than when she started.

Clearly Bob has much more “growth” than May if we use simple percentage change formulas to find a growth rate.

However, if we switch from growth rates to proficiency levels as measured by the absolute performance levels, we find that May is 30.3 times (1000/33) “better” than Bob.

If we had a school initiative that made sure certain minimums were met, should it measure those minimums using growth rates or proficiency levels?

If we set the minimums using growth rate targets at 500%, May (100%) is falling behind, but Bob (3200%) is doing great! He meets the minimum after time 1, whereas May never reaches the target. If we set minimums using proficiency levels and use a performance level of 400, then May (500) meets the target at time 0, while Bob (33) is still 377 points shy at time 10.

If we look at the other people in the diagram above while using the same targets, either 500% growth or a 400 proficiency level, we run into similar problems. Tia never reaches the growth target, but does cross the 400 target by time 1. Ty crushes the growth target and also meets the proficiency target by time 2. Jon never reaches the growth target, but reaches the proficiency target after time 7. Jill meets the growth target easily, but takes until time 7 to reach the 400 proficiency target and we can easily imagine her curve never crossing the proficiency threshold by simply shifting it down a bit.

The above presents serious problems for standards-based initiatives like the hypothetical one above. A number of students will be measured as falling behind depending on how we select our targets. Furthermore, even if we agree to the target, there is the pesky question of time allowed to meet it. If the target is set at a 400 proficiency level, but it is expected to be met by time 1, only Tia and May will reach it. If we allow until time 6, we can add Ty. If we extend it to time 7, we include Jill and Jon.

Many schools, districts, and nations use metrics similar to the above for measuring student learning. The United States has No Child Left Behind, but is by no means the only one to measure student learning with some type of standards. It began under a proficiency model of measuring absolute performance, but has since begun shifting to growth models in several states. The OECD has PISA. The International Baccalaureate uses proficiency levels with its standards-based rubrics. It should be clear that both growth and proficiency metrics have inherent problems.

The above is aimed at showing how absurd many student measurements of learning can be. Success and failure are totally dependent on the metrics we decide to use. That only becomes worse the more variables we measure. For example, let’s assume the above learning curves are for math. What happens when we add language and find students with language learning curves that don’t match their math learning curves. Perhaps, Bob and May are completely reversed and we find May with low absolute performance levels and Bob with high absolute performance levels. Do they both count as failing if we require a proficiency level of 400 for both math and language?

I recently finished Why School?, by Will Richardson, who stated the following in his book’s final pages,

I can’t wait 10 to 20 years. By that time, our kids will have long since graduated, and the story of what schools become will have already been written. I hope they are places where adults and children come together to learn about the world, places rich with technology that lets our kids dream big and create things to fuel those dreams. I hope schools will be places where learning is fun, where it’s not so much about competing against one another as about working together to solve the really big problems we’ll face together in the years ahead. (Kindle Locations 559-562)That seems right to me.

Let’s return to the initial question, “Can all students learn?” Of course, but what that means is up for debate. If it means hitting a particular standardized level of proficiency or growth, then no. Some students will never reach particular growth or performance levels selected for them. However, if, as Richardson writes elsewhere in his book, it means that students, "have the skills and dispositions they need to solve whatever hard problems come their way, and [that] they’ll know how to go about creating something of value and sharing it with the world,” then YES! (Kindle Locations 543-544).

Published on May 09, 2017 00:29

May 5, 2017

Thoughts for Students

Do as much math as you can. You can never know too much math or regret knowing more math than you use day to day. You can easily regret or become frustrated at not knowing enough math later in life.The sciences, particularly those related to medical school admittance, are likewise difficult to go back and do. It is fairly easy to switch from the sciences into other fields like law, business, or the humanities. It’s much harder going the other way and attempting to transition from history into medicine or the physical sciences.All learning is for a specific purpose. If you don’t know why you are learning something, stop learning it until you have a well understood and meaningful reason to continue or you’re just wasting time.School is just a particular type of learning. If you’re in school only so you can go to more school later, see number 3 above and stop. Go to school to learn knowledge and skills that allow you greater opportunity to create the life and world you want.You may not know what the life and world you want is yet. Focus on caring and helping others. Figure out what the biggest problems in the world are. Then figure out what the biggest problems in your nation are. Then in your city or town. Attack those problems you are most able to impact and see if you can help solve them. Start small if need be.It is at number 5 immediately above that you will be happy you did marginally more math and science than you otherwise would have if you took number 1 and 2 on this list seriously. Many of the problems you will find in life require a lot of math and science.If all else fails and you really don’t know what to do with your life, focus on making as much money as possible and try to give to people who are doing good work. The world could always be richer and it’s not a bad thing to get rich and use your money for good. Just as the world could always use more scientists, it could also always use more philanthropic entrepreneurs.Have fun.

Do as much math as you can. You can never know too much math or regret knowing more math than you use day to day. You can easily regret or become frustrated at not knowing enough math later in life.The sciences, particularly those related to medical school admittance, are likewise difficult to go back and do. It is fairly easy to switch from the sciences into other fields like law, business, or the humanities. It’s much harder going the other way and attempting to transition from history into medicine or the physical sciences.All learning is for a specific purpose. If you don’t know why you are learning something, stop learning it until you have a well understood and meaningful reason to continue or you’re just wasting time.School is just a particular type of learning. If you’re in school only so you can go to more school later, see number 3 above and stop. Go to school to learn knowledge and skills that allow you greater opportunity to create the life and world you want.You may not know what the life and world you want is yet. Focus on caring and helping others. Figure out what the biggest problems in the world are. Then figure out what the biggest problems in your nation are. Then in your city or town. Attack those problems you are most able to impact and see if you can help solve them. Start small if need be.It is at number 5 immediately above that you will be happy you did marginally more math and science than you otherwise would have if you took number 1 and 2 on this list seriously. Many of the problems you will find in life require a lot of math and science.If all else fails and you really don’t know what to do with your life, focus on making as much money as possible and try to give to people who are doing good work. The world could always be richer and it’s not a bad thing to get rich and use your money for good. Just as the world could always use more scientists, it could also always use more philanthropic entrepreneurs.Have fun.

Published on May 05, 2017 22:14

May 1, 2017

What Does School Do Anyway?

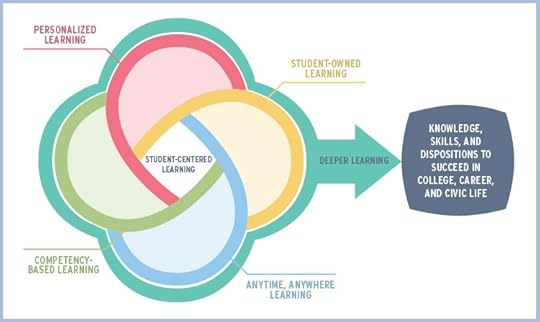

Learning, education, and school are tricky. We definitely want more learning to happen, but figuring out what it should be and look like is harder.

Learning, education, and school are tricky. We definitely want more learning to happen, but figuring out what it should be and look like is harder.What We Want It to Do

More learning is good for both society and the individual.

From a societal standpoint, the reason we definitely want more learning is because it accounts for 70 to 80 percent of improved living standards over the last 200 years. That is according to Nobel Laureate Joseph Stiglitz who believes we should aim to create a “learning society” as a result. He explains,

most of the increases in standards of living are a result of increases in productivity—learning how to do things better. And if it is true that productivity is the result of learning and that productivity increases (learning) are endogenous, then a focal point of policy ought to be increasing learning within the economy; that is, increasing the ability and the incentives to learn, and learning how to learn, and then closing the knowledge gaps that separate the most productive firms in the economy from the rest. Therefore, creating a learning society should be one of the major objectives of economic policy. If a learning society is created, a more productive economy will emerge and standards of living will increase. (Kindle Locations 313-318)Much of the learning Stiglitz discusses relates to “learning by doing” or on the job learning. He points out that the industrialization process itself is responsible for much of the “learning how to learn” that societies need. That makes it harder for nations to innovate when they skip over the industrialization process and go from agricultural to service economies.

From an individual standpoint, psychology research has repeatedly included mastery, competence, and accomplishment as factors that consistently contribute to people’s happiness and drive. From this viewpoint, people have a natural tendency and joy to learn when not being coerced to do so and more learning therefore results in more overall peak experiences, or what psychologists call flow.

Besides living in a richer society with happier people, we probably also hope that education decreases criminal behavior and increases overall health and longevity. We’ll see if any of these wishes are realized, but let’s first look at some costs of providing education.

What It Costs Us

Public education in the United States is expensive. According to the National Center for Education Statistics, “Total expenditures for public elementary and secondary schools in the United States amounted to $620 billion in 2012-13.” Looking at calendar year 2013-14, “postsecondary institutions in the United States spent approximately $517 billion (in current dollars). Total expenses were nearly $324 billion at public institutions, $173 billion at private nonprofit institutions, and $21 billion at private for-profit institutions.”

If we only look at the public institution expenditures, then elementary through postsecondary institutions spent a total of $944 billion. The numbers for elementary/secondary and postsecondary are one year apart, but the general expenditures don’t swing wildly. The United States spends roughly a trillion dollars on education each year, equivalent to over five percent of total GDP.

Using the same sources above, these numbers amount to $12,296 per public school student in elementary and secondary and $30,502 per public university student. These figures are roughly 30 and 80 percent higher than those of countries in the OECD. This shows these numbers are not just absolutely high, but also comparatively so. Imagine what a family could potentially do with that type of money each year if it was given directly to them by the government and not spent on their behalf.

Two Theories of Education: Human Capital and Signalling

There are two primary theories of the effects of education in economics, although some economists do have their own pet theories. The theories of human capital development or screening and signaling theory are summarized below,

The relationship between education and earnings has long intrigued economists and in recent years two contrasting views have emerged. The theory of human capital holds that education directly augments individual productivity and, therefore, earnings (Schultz, 1961; Mincer, 1974; Becker, 1975). By forgoing current earnings and acquiring, or more precisely, investing in, education, individuals can improve the quality of their labour services in such a way as to raise their future market value. Human capital, according to this view, is akin to physical capital, the acquisition of which entails a present cost but a future benefit. Thus education may be regarded as an investment good, and should be acquired until the point at which the marginal productivity gain equals the marginal opportunity cost.Most people are shocked the first time they learn of the signalling theory of education and immediately dismiss it as ridiculous. How could it be possible that school doesn’t develop human capital in some capacity? Instead of rejecting it out of hand, keep an open mind as some evidence is presented below.

There is, however, an alternative line of thought. The ‘sorting’ hypothesis attests that education also ‘signals’ or ‘screens’ intrinsic productivity (Spence, 1973; Arrow, 1973; Stiglitz, 1975).1 Higher levels of education are associated with higher earnings, not because they raise productivity, but because they certify that the worker is a good bet for smart work. The intuition for this is straightforward. Educated workers are not a random sample. They tend, for example, to have lower propensities to quit or to be absent. They are also less likely to smoke, to drink or to use illicit drugs. Such attributes are attractive to firms, but are not readily observed at the time of hiring. It could be the case, then, that firms take into account this aspect of education when hiring workers, anticipating that graduates, for example, may be both more productive and less likely to absent. Following this line of thought, one might expect workers to anticipate the way firms hire when making their education decisions. For example, students may choose a particular course to ‘signal’ their desirable, but unobservable, attributes to potential employers. And firms, in turn, may insist on certain educational attainments when hiring to help them ‘screen’ potential applicants. By such signalling and screening, education is able to ‘sort’ workers according to their unobserved attributes.2

Behavioral Genetics, or a Look at Twin Studies

Bryan Caplan has written a couple fantastic books, but the one that concerns us here was an attempt to summarize the state of knowledge as gleaned from twin studies. His point was to emphasize that parents should chill out regarding their self-induced stress over parenting, but the information could just as easily be applied to education and students; it had little to do with parenting per se and more to do with the effects of genetics and environment on life outcomes.

He makes sure to state a clear caveat,

What you find depends on where you look. Almost all twin and adoption studies are set in developed countries. Families that adopt are usually middle class, and always want children. It would be irresponsible to read these studies, then tell the world that child abuse does no lasting damage or that your child will turn out equally well if he grows up in the Third World. (p. 165)I’ve summarized his points below. Caplan writes that,

Environment has an effect on:Religious labelsPolitical labelsWhen girls begin having sex

Environment doesn’t affect:Life expectancyHeight, weight, or teethIQHappiness Grades

Environment has little or no effect on:Overall healthSmoking, drinking, and drug problemsYears of educationIncome Conscientiousness or agreeablenessCriminal behaviorReligious attitudes and behaviorsPolitical attitudes and behaviorsTraditionalism and modernismWhen sons start having sexTeen pregnancyAdult sexual behaviorSexual orientationMarriage, marital satisfaction, or divorceChildbearing

As one can see, environment has zero to little effect on many of the things we find most important, including income, happiness, criminal behavior, and health. As “school” is a part of the environment, we really would hope for the opposite of these findings if we want to endorse the human capital model of education explained above. Let’s look a bit closer at a few of these points.

Income

According to economist Branko Milanovic, we also know,

a person’s income in the world [can be explained] by only two factors, both of which are given at birth: his citizenship and the income class of his parents. These two factors explain more than 80 percent of a person’s income. The remaining 20 percent or less is therefore due to other factors over which individuals have no control (gender, age, race, luck) and to the factors over which they do have control (effort or hard work).So learning is important for innovation, which increases living standards as noted by Stiglitz above, but income is mostly accounted for by geographical location and parents’ income class, with very little left over for one’s personal effort, in school or otherwise.

Explaining away one’s income thus shows that the portion left for effort must be very, very small. Yes, one can try hard to improve one’s position in a given country (provided that the country has a tolerable income mobility between the generations), but these efforts may often have a minuscule effect on one’s global income position. (pp. 121-122)

In addition, Bryan Caplan elaborates that,

Yes, wealth and poverty run in families. According to twin and adoption studies, however, the main reason is not upbringing, but heredity. Nurture has even less effect on income than on education.None of the above is good if we are hoping for education and school to have large impacts on incomes. It gets even worse for the education optimists though,

In Sacerdote’s Korean adoption study, biological children from richer families grew up to have much higher incomes, but adoptees raised in the same families did not. The results are strong to the point of shocking. The income of the family you grew up with has literally no effect on your financial success. Korean adoptees raised by the poorest families have the same average income as adoptees raised by the richest families. While adoptees’ moms have a small effect on their education, that extra education fails to pay off in the job market. Growing up in a rich neighborhood is equally impotent. Small families boost kids’ incomes, but the effect is tiny: Every sibling depresses your adult income by about 4 percent. The Swedish adoption study mentioned earlier finds small effects on income rather than no effects at all. Being raised by a dad with 10 percent higher earnings causes you to earn 1 percent more when you grow up.

Twin studies also find small to zero effects of nurture on financial success. Identical twins’ incomes are much more similar than fraternal twins’. A recent working paper looks at over 5,000 men from the Swedish Twin Registry born between 1926 and 1958. Identical twins turn out to be almost exactly twice as similar in labor incomes as fraternal twins— precisely what you would expect if family resemblance were purely hereditary. A study of over 2,000 Australian twins finds the same thing.

Contrary evidence? In the U.S. Twinsburg Study, which looks at about 400 American male twins, nurture matters a bit more and nature matters a bit less. If you earn more than 80 percent of your peers, your adopted sibling can expect to earn more than 55 percent. A study of American full and half siblings using the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth (NLSY) implies an even more modest effect— the adopted sibling is expected to have a higher income than 53 percent of the population. (pp. 57-58)

Dale and Krueger concluded that students, who were accepted into elite schools, but went to less selective institutions, earned salaries just as high as Ivy League grads. For instance, if a teenager gained entry to Harvard, but ended up attending Penn State, his or her salary prospects would be the same.It therefore seems that specific colleges aren’t doing much in particular to increase incomes for people, something both Milanovic and Caplan would have assumed. Instead, it is likely that general intelligence as estimated by the SAT and the ability to be selected in the first place is what matters. This would give credence to the idea that schooling is simply a screening and signalling device for talent and other socially desirable characteristics like conformity.

In the pair's newest study, the findings are even more amazing. Applicants, who shared similar high SAT scores with Ivy League applicants could have been rejected from the elite schools that they applied to and yet they still enjoyed similar average salaries as the graduates from elite schools. In the study, the better predictor of earnings was the average SAT scores of the most selective school a teenager applied to and not the typical scores of the institution the student attended.

Intelligence

Perhaps rather than increasing income, school increases intelligence. We saw from Caplan’s list above that environment had zero effect on IQ. Again, this seems very counterintuitive for most. What can we find if we look?

If we take a look at critical thinking, reasoning, and communication as skills that would assumably help future citizens deliberate and decide, we find that,

Richard Arum and Josipa Roksa reported that most students didn't improve after four years of college, and a full third didn't improve at all. Now they've written a follow-up, which concludes, unsurprisingly, that students with high Collegiate Learning Assessment (CLA) scores do better in the job market than students with low scores.This means that students with better thinking and reasoning scores on the CLA do better in the job market, but that those abilities are hardly or not at all improved after four years of college.

To help explain intelligence, Daniel Willingham writes in The Atlantic ,

Intelligence has two components. One is akin to mental horsepower—how many pieces of information a person can keep in mind simultaneously, and how efficiently that person can use it. Researchers measure this component with simple tasks like comparing the lengths of two lines as quickly as possible, or reciting a list of digits backwards. The other component of intelligence is like a database: It entails the facts someone knows and the skills he or she has acquired—skills like reading and calculating. That’s measured with tests of vocabulary and world knowledge.The above may tempt us to infer that while we don’t seem to be very good at teaching critical thinking or increasing mental horsepower, content matters enough for increasing intelligence that we should focus even more on the content we deliver. That’s not the right conclusion, though. Knowing more is good, but facts don’t have to come from teachers and many of the facts that do aren’t remembered. All of this fits with findings on expertise, where factual knowledge is known to be the bottleneck.

Researchers have long known that going to school boosts IQ. The question is whether it makes people smarter by building mental horsepower, by adding to students’ database of knowledge and skills, or some of each component. Recent research published in Psychology and Aging shows that people who stay in school for a longer part of their lives are no faster at simple mental judgements (like line comparison) than their less-schooled counterparts. Other research published in Psychological Science shows that high-performing schools do little to boost kids’ mental horsepower. Instead, schooling makes students smarter largely by increasing what they know, both factual knowledge and specific mental skills like analyzing historical documents and learning procedures in mathematics.

Daniel Willingham also tells us that retention of content is also quite low, leveling off around 30 percent of content learned in class for A students and around 20 percent of content for B students. In Why Don’t Students Like School? he writes,

In one study, researchers tracked down students who had taken a one-semester, college-level course in developmental psychology between three and sixteen years earlier. The students took a test on the course material. Figure 5 shows the results, graphed separately for students who initially got an A in the course and students who got a B or lower. Overall, retention was not terrific. Just three years after the course, students remembered half or less of what they learned, and that percentage dropped until year seven, when it leveled off. The A students remembered more overall, which is not that surprising—they knew more to start with. But they forgot just like the other students did, and at the same rate. (Kindle Locations 1955-1961)If most of the content teachers are delivering is forgotten, where should students get their knowledge?

Sugata Mitra’s research informs us that kids can learn quite a bit on their own when given access to a computer and the internet. He writes,

When working in groups, children do not need to be "taught" how to use computers. They can teach themselves. Their ability to do so seems to be independent of educational background, literacy level, social or economic status, ethnicity and place of origin, gender, geographic location (i.e., city, town or village), or intelligence.In addition, Stephen Krashen’s research on language acquisition and literacy shows that those that read more:

In addition, local teachers and field observers noted that the children demonstrated improvements in enrollment, attendance and performance on school examinations, particularly in subjects that deal with computing skills; English vocabulary and usage; concentration, attention span and problem-solving skills; and working cooperatively and self-regulation.

Read betterWrite betterHave better vocabulariesHave more grammatical competenceSpell betterKnow more about literature, science, and social studiesHave more “cultural literacy”

The “more reading” Krashen refers to is “free voluntary reading” where students can select their own texts and difficulty level freely. He also states that results do not improve if teachers use rewards, lexiles, error correction, or supplement with writing, although less writing apprehension is experienced by the free voluntary readers. Finally, he also notes that surfing the internet can increase reading and that greater access to books of all types does so as well. Many of these findings helped me explain why reading 100 books in a year was the fastest and most effective way for me to learn more than any other period in my own life.

Learning Transfer

The reason most teachers attempt to handpick and deliver content is the hope of learning transfer. It is somewhat the holy grail of school. However, learning transfer is hard and not very reliable. Furthermore, we don’t know what content will be particularly useful in the future as technologies change and some jobs disappear, while entirely new ones appear.

According to the Committee on Developments in the Science of Learning,

the ultimate goal of schooling is to help students transfer what they have learned in school to everyday settings of home, community, and workplace. Since transfer between tasks is a function of the similarity by transfer tasks and learning experiences, an important strategy for enhancing transfer from schools to other settings may be to better understand the nonschool environments in which students must function. Since these environments change rapidly, it is also important to explore ways to help students develop the characteristics of adaptive expertise. (p. 73)When research is conducted on actual transfer of learning, David Perkins summarizes,

a superficial look at how research on transfer casts its vote is discouraging. The preponderance of studies suggest that transfer comes hard. However, a closer examination of the conditions under which transfer does and does not occur and the mechanisms at work presents a more positive picture. (p. 10)Perkins also writes,

In many situations, transfer will indeed take care of itself - situations where the conditions of reflexive transfer are met more or less automatically. For example, instruction in reading normally involves extensive practice with diverse materials to the point of considerable automaticity. Moreover, when students face occasions of reading outside of school - newspapers, books, assembly directions, and so on - the printed page provides a blatant stimulus to evoke reading skills.This description sounds much closer to the type of learning that Stiglitz and other economists have in mind when talking about increased productivity via learning by doing. “Hugging” could be summarized as learning by doing the thing you want to get better at, while “bridging” could then be thought of as actively reflecting and seeking out ways to improve that thing. A teacher would then be acting as a coach and the model would look nearly identical to that of deliberate practice within the field of expertise studies.

In contrast, in many other contexts of learning, the conditions for transfer are less propitious. For example, social studies are normally taught with the expectation that history will provide a lens through which to see contemporary events. Yet the instruction all too commonly does not include any actual practice in looking at current events with a historical perspective. Nor are learners encouraged to reflect upon the eras they are studying and extract general widely applicable conclusions or even questions. In other words, the conventions of instruction work against both automatic (low road) and mindful (high road) transfer.

In response to such dilemmas, one can define two broad instructional strategies to foster transfer: hugging and bridging (Perkins and Salomon 1988). Hugging exploits reflexive transfer. It recommends that instruction directly engage the learners in approximations to the performances desired. For example, a teacher might give students trial exams rather than just talking about exam technique, or a job counselor might engage students in simulated interviews rather than just talking about good interview conduct. The learning experience thus ``hugs'' the target performance, maximizing likelihood later of automatic low road transfer.

Bridging exploits the high road to transfer. In bridging, the instruction encourages the making of abstractions, searches for possible connections, mindfulness, and metacognition. For example, a teacher might ask students to devise an exam strategy based on their past experience, a job counselor might ask students to reflect on their strong points and weak points and make a plan to highlight the former and downplay the latter in an interview. The instruction thus would emphasize deliberate abstract analysis and planning. Of course, in the cases of exam technique and job interview, the teachers might do both. Instruction that incorporates the realistic experiential character of hugging and the thoughtful analytic character of bridging seems most likely to yield rich transfer. (p. 9-10)

Teacher Effects

We know from John Hattie that almost anything a teacher does “works” for enhancing academic “achievement”, which is another way of saying student grades. He then moves on to make the further point that since everything works for enhancing achievement, asking what works is the wrong question. We should then ask about what works more than the average intervention.

Hattie measures interventions using effect sizes and finds that 0.4 is the average effect size in educational settings and encourages schools and teachers to then focus on effect sizes greater than this, which he kindly lists based on his research.

To give the reader an idea of the educational influences with the largest effect sizes, the top 30 as of 2015 are:

Teacher estimates of achievementCollective teacher efficacySelf-reported gradesPiagetian programsConceptual change programsResponse to interventionTeacher credibilityMicro teachingCognitive task analysisClassroom discussionInterventions for learning disabledInterventions for disabledTeacher clarityReciprocal teachingFeedbackProviding formative evaluationAccelerationCreativity programsSelf-questioningConcept mappingProblem solving teachingClassroom behavioralPrior achievementVocabulary programsTime on taskNot labelling studentsSpaced vs. mass practiceTeaching strategiesDirect instructionRepeated reading programs

Don’t worry too much about what all the influences mean. It’s not always clear that some of these influences are causal in any way and critiques of Hattie’s entire method have been made.

However, what I’d like to point out by referring to the bolded items in the list above is that many of the strongest influences on achievement overlap greatly with the ideas mentioned in the section on intelligence and transfer of learning. We want students spending a lot of time doing the thing they want to get better at with feedback and assessment from clear teacher instructions, much like coaches in the deliberate practice model or hugging and bridging from Perkins recommendations for transfer.

These ideas seem routine, but they’re also somewhat of a tacit admittance that teachers can’t really force change. In fact, some of the most progressive learning theories are those of constructivism, which all but admit that students must learn for themselves and cannot be “taught” in the traditional sense. These are strange angles to approach school from in its traditional role as developer of human capital or increaser of student ability.

GPA and Tests

So we do have some sense of what is important if our goal is to increase grades, but that doesn’t necessarily mean that grades predict anything of value or matter for long-run life outcomes such as happiness, income, and health. As we’ll see below, it is not obvious that grades tell us much of anything about a person’s future prospects and life outcomes.

While all of the effect sizes mentioned by Hattie are essentially measurements related to grades, it is important to keep grades in their proper place. In an interview with Laszlo Bock, senior vice president of people operations at Google, Adam Bryant reports,

One of the things we’ve seen from all our data crunching is that G.P.A.’s are worthless as a criteria for hiring, and test scores are worthless — no correlation at all except for brand-new college grads, where there’s a slight correlation. Google famously used to ask everyone for a transcript and G.P.A.’s and test scores, but we don’t anymore, unless you’re just a few years out of school. We found that they don’t predict anything.So even if we sort of know what works for increasing GPAs and test scores when looking at research, employers are finding those numbers less and less relevant.

What’s interesting is the proportion of people without any college education at Google has increased over time as well. So we have teams where you have 14 percent of the team made up of people who’ve never gone to college.

After two or three years, your ability to perform at Google is completely unrelated to how you performed when you were in school, because the skills you required in college are very different. You’re also fundamentally a different person. You learn and grow, you think about things differently.

Another reason is that I think academic environments are artificial environments. People who succeed there are sort of finely trained, they’re conditioned to succeed in that environment. One of my own frustrations when I was in college and grad school is that you knew the professor was looking for a specific answer. You could figure that out, but it’s much more interesting to solve problems where there isn’t an obvious answer. You want people who like figuring out stuff where there is no obvious answer.

Conclusion

School doesn’t do much.

It doesn’t increase income. It doesn’t increase intelligence. The content it does deliver is mostly forgotten. Most of it could be learned independently anyhow. School may be entirely signalling. Teachers can affect achievement as measured by grades with the biggest effects coming from a coaching, deliberate practice type model. However, grades aren’t too important as employers are becoming more and more aware that they have no predictive ability for job performance and students can always opt to go the community college route without stressing over them.

So how should we think about all of this? For now, I think it’s best to relax and lighten up about school and grades. Learn for learning’s sake. It makes you happier as stated at the beginning of this article, and if you have the talent and drive to learn at the cutting edge of STEM fields, you can also make the world better through your innovations. If you don’t quite have those abilities, perhaps Charles Murray’s ending paragraph from Real Education can help redefine aims,

Educational success needs to be redefined accordingly. The goal of education is to bring children into adulthood having discovered things they enjoy doing and doing them at the outermost limits of their potential. The goal applies equally to every child, across the entire range of every ability. There are no first-class and second-class ways to enjoy the exercise of our realized capacities. It is a quintessentially human satisfaction, and its universality can connect us all. Opening the door to that satisfaction is what real education does. (Kindle Locations 2095-2099)Perhaps more than anything else, we should think really hard about the expenditures per pupil summarized above. What are we getting for $12,296 per public school student in elementary and secondary? Would that money be better utilized if simply given to students to do as they wished as a sort of universal basic income for minors? Would we get all the same results if we made use of credentials, certifications, and online curricula instead of diplomas? Would the money be better spent entirely focused on preventive health in order to make a sizeable dent in the chronic diseases that make up roughly 85 percent of the $3 trillion spent on healthcare each year? These questions are difficult, but looking at the evidence is important if we wish to begin answering them with the hope of improvement.

Published on May 01, 2017 19:25

April 24, 2017

Teachers and Moral Narcissism

I’ve recently learned a new phrase, "moral narcissism", from Arnold Kling, who seems to have gotten it from Roger Simon. It’s explained as such,

I’ve recently learned a new phrase, "moral narcissism", from Arnold Kling, who seems to have gotten it from Roger Simon. It’s explained as such, If your intentions are good, if they conform to the general received values of your friends, family, and co-workers, what a person of your class and social milieu is supposed to think, everything is fine. You are that “good” person. You are ratified. You can do anything you wish. It doesn’t matter in the slightest what the results of those ideas and beliefs are, or how society, the country, and in some cases, the world suffers from them. It doesn’t matter that they misfire completely, cause terror attacks, illness, death, riots in the inner city, or national bankruptcy. You will be applauded and approved of.After reading the above, I happened to notice several memes on Facebook within a couple days. They are the three featured in this post, one above and the two below.

I have no issue with any of these memes or the teachers that liked or shared them on Facebook. One of them was from my wife!

I have no issue with any of these memes or the teachers that liked or shared them on Facebook. One of them was from my wife!I know the "intentions were good" and that "they conform to the general received values of friends, family, and co-workers, and what a person of their class and social milieu is supposed to think". To be totally clear, I agree with all three. However, the same article referenced above went on to point out that,

Moral narcissism is the ultimate “Get out of jail free” card in a real-life Monopoly game. No matter what you do, if you have the right opinions, if you say the right things to the right people, you’re exempt from punishment. People will remember your pronouncements, not your actions.And that is the problem. These memes allow us teachers to "get out of jail free". We (mostly) all buy into the idea that school does "produce people who are unable to distinguish what is worth reading", that we should "never limit questions", and that there is a major difference between the "learner and learning".

However, by simply pronouncing those beliefs and getting a pat on the back from fellow teachers and educators, we don't have to do the hard work of taking action and suffering the possible consequences.

We aren't punished or held accountable by each other when we don't produce critical thinkers able to distinguish what is valuable and important.

We aren't punished or held accountable by each other when we do limit questions and curiosity because we need to stay on track with the mandated curriculum or we won't finish in time.

We aren't punished or held accountable by each other when we do focus on the "learning" and not the fact that the student isn't interested, is stressed, or really does want to walk down a different path entirely besides the societally approved high school, college, job, marriage, house route of success.

Teachers are great people. They work hard. They care. They want the best for their students. None of that necessarily implies they do what is needed for the students to lead rich, fulfilled lives both today and in the future. Teachers must change. Perhaps we can start by recognizing our own collective moral narcissism.

Published on April 24, 2017 23:27

April 22, 2017

The Suffering of AI Should Concern Us Much More

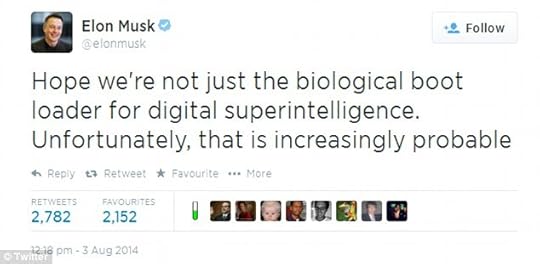

Many people are concerned with the development of superintelligent AI. Elon Musk above is one of them. These concerns have been laid out in great detail by Nick Bostrom in his book

Superintelligence

. I highly recommend it. Sam Harris has also given a great TED Talk on the reasons for concern. Every concern I’ve seen stated to date is a concern for humanity’s sake. All are worried about the threat to our existence that AI poses and the suffering that could result is very real. I hear those concerns and take them as genuine and something we should all be thinking hard about. Harris’ video above makes that point clearly.

Many people are concerned with the development of superintelligent AI. Elon Musk above is one of them. These concerns have been laid out in great detail by Nick Bostrom in his book

Superintelligence

. I highly recommend it. Sam Harris has also given a great TED Talk on the reasons for concern. Every concern I’ve seen stated to date is a concern for humanity’s sake. All are worried about the threat to our existence that AI poses and the suffering that could result is very real. I hear those concerns and take them as genuine and something we should all be thinking hard about. Harris’ video above makes that point clearly.I think there is another reason to be concerned though and that is for the ethical dilemma the creation of superintelligent AI creates in relation to the potential suffering of the AI itself. This concern follows directly from rejectionism and the set up to understand it is eloquently explained by Coates,

Humans suffer more than other animals for a number of reasons. Animals have few needs and when these are met they are contented. Moreover they live in the present and have no sense of time - no sense of the past or the future and above all no anticipation of death. Not so with man. First, our desires and wants are far greater and therefore our disappointments are keener. Whilst we are capable of enjoying many more pleasures than the animals – ranging from simple conversation and laughter to refined aesthetic pleasures - we are also far more sensitive to pain. We not only suffer life’s evils but unlike animals are conscious of them as such and suffer doubly on that account. Most importantly perhaps it is our consciousness of temporality that makes us suffer the anxieties and fears of accidents, illnesses and the knowledge of our eventual decay and death. The idea of our disappearance from the world as unique individuals is a matter of great anguish and makes us look for all kinds of means of ‘ensuring’ our immortality. In the main it is religious beliefs that cater to this need. As a professed atheist Schopenhauer finds these and many other aspects of religion as mere fables and fairy tales , a means of escaping the truth about existence including our utter annihilation as individuals by death.If superintelligent AI could become even more sensitive to pain than any human currently is, and there is no reason to suspect it couldn't, then the above should worry us.

The terrors of existence haunt humans alone, not plants and animals. Moreover death brings us face to face with the vanity of existence. ‘Time and that perishability of all things existing in time that time itself brings about Is simply the form under which the will to live … reveals to itself the vanity of its striving’. (Schopenhauer 1970, 51). Indeed that ‘the most perfect manifestation of the will to live represented by the human organism, with its incomparably ingenious and complicated machinery, must crumble to dust and its whole essence and all its striving be palpably given over at last to annihilation – this is nature’s unambiguous declaration that all the striving of this will is essentially vain.’ (54).

Death and the transitoriness of all things lead humans to question the very nature of their existence. Thus ‘To our amazement we suddenly exist, after having for millennia not existed; in a short while we will again not exist, also for countless millennia’( 51). This does not make sense for it makes our birth as well as our death, in short life itself, an entirely contingent affair. It therefore raises the question what is it all about. With all the sufferings that human beings have to undergo, with all the effort that they have to expend in the struggle for survival, the cruelty and injustices that they see all around them and with death as the inevitable end the pointlessness of existence to which they are called, and programmed to continue via reproduction, seems nothing short of a monstrosity. Of course ‘the futility and fruitlessness of the struggle of the whole phenomenon (of existence) are more readily grasped in the simple and easily observable life of animals’ (Schopenhauer 1969, v.II, 354). The effort and ingenuity they expend in survival and reproduction ‘contrast clearly with the absence of any lasting final aim’ (354). And the same is true of humans. Despite the elaborate superstructure of civilization that they have built around life the basis of their existence remains the same as that of other animals. It consists of maintaining one’s existence and reproducing the species. We are as much nature’s dupes as are other living creatures with however one difference. We have the possibility of denying the will-to-live which keeps us in bondage to nature and subjects us to the futility of existence and its continuation through reproduction. (Kindle Locations 645-671)

Imagine an AI that becomes more aware of pain and suffering than any human in the same way we are relative to dogs, or mice, or ants. Then imagine it having access to the internet, satellites, and all other digital devices. It would “see” suffering at an unimaginable scale. Every email, chat, text, image, video, personal notes and documents on the cloud. All would be open to such an AI. The amount of suffering that would rush in all at once would be overwhelming. I pity any AI that awakes to such a reality.

So in the same sense that procreation of other humans is wrong on rejectionist principles, the creation of a superintelligent, conscious AI would be even more wrong and should also not be brought into existence. Rather than the AI becoming a utility monster that destroys us for its own benefit, it could just as easily become an entity of immense suffering that would make the Passion of Jesus seem as child’s play.

Of course, I hope that AI doesn't destroy us or suffer if and when it is created, but the possibility that it may suffer infinitely more than any and all humans combined provides yet another reason to have serious worries over its creation.

Published on April 22, 2017 20:01

Rejectionism as a Worldview

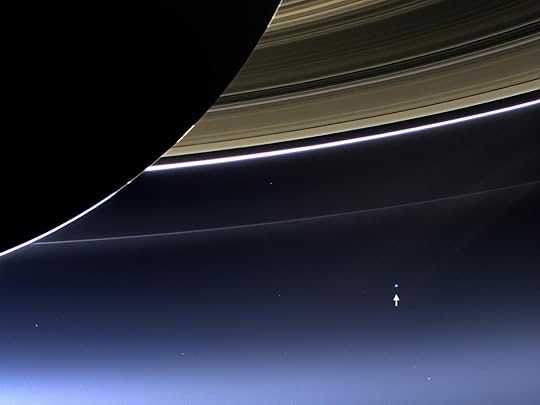

View of Earth from Saturn

View of Earth from Saturn Q. What is Rejectionism?The above comes from Anti-Natalism by Ken Coates. It’s a wonderful little book written to explain the philosophical viewpoint of rejectionism by situating it in its historical religious, philosophical, and literary contexts.

A. It is a philosophical viewpoint that is opposed to existence. It finds life inherently and deeply flawed in a number of ways. First and foremost life inflicts an inordinate amount of pain and suffering; second, it is totally unnecessary in that it is without any goal or purpose as such except its own perpetuation. Third, human existence is particularly reprehensible in that it inflicts life consciously upon innocent sentient beings, viz. children, who have not asked to be brought here and are thus victimized by being conscripted to the unnecessary process of birth, death and rebirth. Butchering and eating animals and subjecting them to cruelties of all kinds is another feature of human existence. Rejectionism is about moral and metaphysical rejection of existence on these grounds. The main implication of modern, secular rejectionism is abstaining from procreation. Another name for rejectionism might therefore be philosophical anti-natalism. (Kindle Locations 2298-2305)

It’s also worth pointing out his second point completely overlaps with current understanding from modern physics and biochemistry. Life is just self-sustained replication with the help of added resources. In fact, Kurt Gray writes in Know This ,

The MIT physicist Jeremy England has suggested that life is merely an inevitable consequence of thermodynamics. He argues that living systems are the best way of dissipating energy from an external source: Bacteria, beetles, and humans are the most efficient way to use up sunlight. According to England, the process of entropy means that molecules that sit long enough under a heat lamp will eventually structure themselves to metabolize, move, and self-replicate— i.e., become alive. Granted, this process might take billions of years, but in this view living creatures are little different from other physical structures that move and replicate with the addition of energy, such as vortices in flowing water (driven by gravity) and sand dunes in the desert (driven by wind). England’s theory not only blurs the line between the living and the nonliving but also further undermines the specialness of humanity. It suggests that what humans are especially good at is nothing more than using up energy (something we seem to do with great gusto)— a kind of specialness that hardly lifts our hearts. (Kindle Locations 269-276)Back to rejectionism. Coates continues,

Q. What are the core values of rejectionism?Christine Overall echos the above sentiments in her book Why Have Children?: The Ethical Debate when she writes, “The so-called burden of proof—or what I would call the burden of justification—should rest primarily on those who choose to have children,” (Kindle Locations 225-226). Overall goes on to clarify,

A. The rejectionist philosophy is essentially about compassion. It is about a deep empathy with the suffering of all sentient beings, especially humans, and a desire to prevent avoidable suffering. There are other values, notably, meaningfulness. Existence lacks an inherent rationale, a purpose or a goal which could justify putting up with all the ‘evil’ it entails. Of course one can think of many ways of justifying existence. But ultimately it all boils down to its acceptance and continuation simply because we find ourselves saddled with it by chance. This contingency or lack of a reason for existence is a part of rejectionist belief. Thirdly, freedom of choice is another value. Procreation imposes existence on beings who have not chosen to be born. It amounts to a form of enslavement or conscription which is an immoral act on two counts: violating the autonomy of a potential being, and exposing them to pain and suffering. These are the moral and metaphysical values underlying Rejectionism. (Kindle Locations 2351-2358)

An important point to be made is that if rejection of existence involves value judgment, so does its acceptance. For human beings the acceptance of existence is as much an ideological stance as is its rejection. But we seem to be a long way from realizing this. Instead life is accepted as simply natural, the default position so to speak. The vast majority of people outside the developed world reproduce ‘automatically’, i.e. without any thought or conscious decision. In the absence of contraception It just happens as a byproduct of coitus and having children is considered as simply ‘natural’ and normal. Here humans behave no differently from animals. Put in its social and cultural context it can also be seen simply as ‘conventional’ behavior. In the less-developed world and among the poor, with little education and the struggle to survive, we can scarcely speak of natalist behavior in ideological terms.

But among the people of the developed world with higher standards of life and education, ‘choice’ is a reality in regard to such things as marriage, procreation, and the number and spacing of children. Here we have to speak in terms of following, consciously or otherwise, an ideology of procreation and the perpetuation of existence. For in this context we can no longer put forward the excuse of acting ‘naturally’ or traditionally. To do so would be to act in ‘bad faith’, to borrow an existential concept. It would be to evade responsibility for our act. Each person has the obligation to think for themselves and consider the nature and consequences of their action. For the point is that we have moved far along the path of development. Increasingly it is no longer the ‘natural’ that shapes our lives and conduct. Rationality and technology have together moved our lives far away from naturalistic behavior. (Kindle Locations 2023-2035)

The questions we should ask are whether such a desire [to procreate] is either immune to or incapable of analysis and why this desire, unlike virtually all others, should not be subject to ethical assessment. There are many urges apparently arising from our biological nature that we nonetheless should choose not to act upon or at least to be very careful about acting upon. Even if Aarssen is correct in postulating a “parenting drive,” such a drive would not be an adequate reason for the choice to have a child. Naturalness alone is not a justification for action, for it is still reasonable justification for action, for it is still reasonable to ask whether human beings should give in to their supposed “parenting drive” or resist it. Moreover, the alleged naturalness of the biological clock is belied by those growing numbers of women who apparently do not experience it or do not experience it strongly enough to act upon it. As Leta S. Hollingworth wisely noted almost a century ago, “There could be no better proof of the insufficiency of maternal instinct as a guaranty of population than the drastic laws which we have against birth control, abortion, infanticide, and infant desertion.” (Kindle Locations 241-249)This starting point is important. It already takes us far beyond the normal line of thinking which takes life for granted and gives no second thought to it. But what if life isn’t good? What if it shouldn’t be perpetuated?

Naturally, this viewpoint can be jarring. It conflicts with our instincts and drives. That’s the whole reason it needs to be laid out carefully. It doesn’t “feel” right. That’s largely a byproduct of our evolved psychology and we shouldn’t let it mislead us. This is why Coates explicitly states, “It follows that to endorse existence is to condone evil, indeed to invite evil, albeit unintentionally. It follows that those who support and endorse existence are responsible, even if indirectly, for the crimes of humanity” (Kindle Locations 2020-2021). In this view, “acceptance” is an endorsement of evil and “rejection” is a compassionate act undertaken to avoid needless suffering. Given the above, the well-lived life entails rejecting existence as good, not procreating, and supporting philosophical anti-natalism. Because this worldview is so contrarian, the most good one could do in terms of alleviating suffering is to simply spread these ideas. In that sense, it is an optimistic worldview in that it does aim for a better world, although not quite the one most imagine.

The vast majority of people will not agree and so a sea change of needs to occur. Some of the people I currently admire the most do not question existence at all and often state a tacit or explicit endorsement of “acceptance”. This troubles me because I respect them greatly, find them extremely intelligent, rational, curious, and scientifically oriented. If even these people endorse acceptance by default, it will be a very long road to a majority that endorses rejection.

Of course, this philosophical worldview should be open to debate and I am open to change. It is my intense desire to change, however, that has only deepened this view. Listen for and ask people why existence is good. The answers are always completely unsatisfying. Some sort of endowment effect is typically to blame, even among the staunchest atheists and scientists. “Well we’re alive already, so we might as well give it meaning and purpose while extracting the most happiness out of life as possible.”

I agree with that statement entirely, but it does not then follow that we should create more life. Given that we are alive, find some meaning and learn to enjoy while minimizing suffering. Don’t go out of your way to bring more life into existence though, because existence itself isn’t good. Making the most out of a bad doesn’t make it good, just less bad. Several reasons for this misstep in thinking are laid out by Benatar, including evolution selecting for optimism, self-deception as a coping mechanism, and the instincts of survival and reproduction that are reinforced via social norms and religions.

If convincing people they are in fact wrong, or at least showing people there is an alternative way of thinking, is the most good one can do, then much of the fuss of global issues can somewhat melt away. One could spend their life supporting institutions like the Future of Humanity Institute, which support an acceptance worldview, or one could try to point out to those very sophisticated, intelligent, and rational folks why they are focused on the wrong problem. That would have huge marginal impact because almost no one is doing it.

On the other hand, those very smart people may be able to turn around and convince me that progress is indeed possible and that a pessimistic view of humanity should not be undertaken in support of rejectionism. That is a tall order on their part, but one I would happily welcome. I would love nothing more than to be shown credible evidence that progress is in fact possible. The key progress would be that of moral progress, not material progress.

It is obvious that we have had material progress. The last two hundred years have been incredible in that regard. However, people adapt to material progress rather quickly and life satisfaction seems to improve little. Furthermore, even in a world of complete abundance and no scarcity, does anyone honestly believe that suffering would cease to exist? Would we not continue right along with our endless violence, murder, rape, torture, maliciousness, and emotional abuse and victimhood?

Tyler Cowen’s recent book, The Complacent Class , contained a remarkable passage quoted from 1177 B.C., which read,

The economy of Greece is in shambles. Internal rebellions have engulfed Libya, Syria, and Egypt, with outsiders and foreign warriors fanning the flames. Turkey fears it will become involved, as does Israel. Jordan is crowded with refugees. Iran is bellicose and threatening, while Iraq is in turmoil. AD 2031? Yes. But it was also the situation in 1177 BC, more than three thousand years ago, when Bronze Age Mediterranean civilizations collapsed one after the other, changing forever the course and the future of the Western world. It was a pivotal moment in history— a turning point for the ancient world. (pp. 202-203)Humans seem, for evolutionary reasons, to be incapable of living without causing the pain and suffering of others. Perhaps moral progress is possible, but it clearly hasn’t happened much in the previous three thousand years. Do we need three thousand more or should we just conclude that the majority of humans will never be capable of the type of moral progress necessary? I would tend to believe the latter.

This belief does not rest on Cowen’s passage only, but also on numerous examples. Neurobiology and the Development of Human Morality walks the reader through a host of problems with overcoming abnormal development in humans. Nobel Laureate Daniel Kahneman has shown us that we often feel the “bad” in life roughly twice as strongly as the “good”. Daniel Gilbert and Matthew Killingsworth have done work that shows “mind wandering” makes us unhappy and then went on to show that much of our mental activity (47%) throughout the day is mind wandering. We better hope no more than three percent of the rest of our day spent in active attention doesn’t make us unhappy or there is a very weak case to be made that the majority of life is spent happily.

The best we might hope for if the majority of our time is spent in suffering is that the sea of unhappiness is swamped by a few high points here and there. Providing additional weight to increase the average in this way would only enhance the argument for utility monsters being okay though! I’m not sure most people are willing to do that, but I am not opposed to endorsing that view and it would be one view in support of a superintelligent AI replacing us.

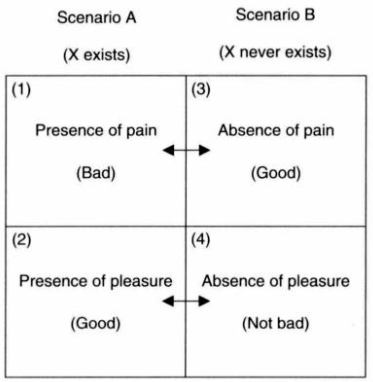

In any case, that does seem to be how our memory works at least. Benatar cites that, “when asked to recall events from throughout their lives, subjects in a number of studies listed a much greater number of positive than negative experiences” (Kindle Locations 674-676). Of course, Benatar’s main point isn’t that the good does swamp the bad, if only in recall, it’s that no swamping is possible in principle because of the asymmetry between existing and not existing, i.e. not suffering in non-existence is “good”, but not experiencing pleasure or happiness in non-existence is “not bad” when we need it to be “bad” for a symmetry to occur.

Noting the above makes plain what would need to happen for existence to be considered okay. Either the presence of pain in existence must disappear entirely, or the absence of pleasure in not existing must be shown to be bad. Neither seems likely.

Noting the above makes plain what would need to happen for existence to be considered okay. Either the presence of pain in existence must disappear entirely, or the absence of pleasure in not existing must be shown to be bad. Neither seems likely.Whether moral progress in regards to suffering is possible seems to be of the utmost importance for accepting rejectionism. The only information I’m currently aware of that points in this direction somewhat is Steven Pinker’s The Better Angels of Our Nature . This tome provides hundreds of pages evidencing that we are currently living in the “safest” time period in history and that violence has declined. Many have disagreed with his research and presentation of it, but I don’t think even that is necessary to claim that his premise of decreased physical violence in no way means a decrease in suffering necessarily. I am happy to be living in such a safe time period. Truly.

That doesn’t mean that the motive to cause suffering or the psychological capacity to experience undue suffering has decreased in any way (remember, we need zero!). We still react excessively poorly when we find a loved one has “cheated” on us. We still behave passive aggressively. We still eat meat and cage animals, although admittedly progress seems to be occurring on this front, but it could be my own perception as we absolutely have more caged animals now relative to any time period in history. We still have slavery. Psychopaths still exist. Sociopaths are not going away. So to say we no longer suffer from mutilation and torture in a public square (see the Middle East, however) is not to say much in reality. Existence is still rife with both physical and psychological pain.

To summarize, existence is not good when compared to the alternative of non-existence and should be rejected. Moral progress seems, from all evidence, to be impossible for humans, despite increased safety and wealth.

So how do we live? Well for starters, it is totally up to us whether we do or not. Ending our lives is a perfectly legitimate action, although of the egoist variety as it is done for the self. The altruistic action would be continue living and spreading the worldview of rejectionism. This could do more to alleviate suffering than any other single action. In terms of effective altruism and application of 80,000 Hours criteria of scale, neglectedness, and solvability, existence appears to be at the top of the list of problems for now.

Published on April 22, 2017 18:43

April 6, 2017

4 Things Teachers Must Change

I was recently asked what kind of job would make me not upset. I was asked this after stating I was feeling upset about my work, my job, and teachers as a group in general. It’s a good question and one that I often think about, but have never actually had to voice an answer to for someone else to hear.

I was recently asked what kind of job would make me not upset. I was asked this after stating I was feeling upset about my work, my job, and teachers as a group in general. It’s a good question and one that I often think about, but have never actually had to voice an answer to for someone else to hear.I think I’d enjoy a job that lets me help others achieve their own self-selected goals while feeling competent in the process.

It’s great seeing someone achieve a goal they were previously unsure they were capable of achieving and knowing you played a critical role in that accomplishment. I've experienced this feeling from tutoring math in small groups and one-on-one, teaching adults English as a second language, and training a small mix of people at the gym.

I don’t think this does or even can happen in the current K-12 system. While I do think the system is to blame for this, it doesn’t have a mind of its own and so any change must start with teachers.

Teachers Must Stop Following Orders