Rajeev Kurapati's Blog, page 5

March 21, 2017

THE HOSPITAL CHECKLIST

Hospitalization can be a harrowing experience. Patients arrive seriously ill or injured, and in addition to whatever ailments they’re suffering, they must simultaneously find ways to cope with unfamiliar medical professionals and uncomfortable procedures. We doctors and hospital support staff are often asking these people—some of whom might be quite sick or in a great deal of pain—not only to quickly understand their complex conditions and treatments, but also to arrange for the assistance and care they’ll need after discharge. Many will find themselves facing new medications, follow-up treatments, a rash of specialists, unfamiliar equipment, and physical limitations—and this barely takes the emotional strain into account. It’s not difficult to see why such a large number of patients and their families report being overwhelmed by a hospital stay.

As a hospital physician, I see patients and families every day who struggle to understand the information they are (or sometimes aren’t) given. Patient advocacy—for yourself or for someone whose care you’re responsible for—significantly affects health and recovery. I want to help make you better at it.According to the World Health Organization, a study in eight hospitals showed that the implementation of checklists during surgical procedures reduced the rate of deaths and surgical complications by more than a third.

It seems likely, then, that patients would benefit from a checklist of their own. The following list is a resource meant to aid patients and their loved ones in better preparing for and understanding what information they’ll need before, during, and after a hospital stay.

1. After admission, ask the names of your primary hospital doctor and the other specialists who make up your physician team. Your primary hospital physician will coordinate with the team, and your nurses will assist you during your stay.

______________________________________________________________________________

2. Ask your physician: What is my main diagnosis, and are there any other newly diagnosed issues? Feel free to express your fears and anxieties about your diagnosis to the physicians and nursing staff. Don’t let the anxiety build until it becomes uncontrollable.

______________________________________________________________________________

3. Ask your nurse or physician: How are my illnesses responding to treatment? Ask the nursing staff in particular about how your condition is progressing and how you can facilitate your recovery. It’s your fundamental right to obtain information regarding your medical condition. Understanding both your diagnosis and your treatment plan is a central tenet of the Patient’s Bill of Rights, which was adopted by the Association of American Physicians and Surgeons in 1995. According to this document, all patients are entitled “to be informed about their medical condition, the risks and benefits of treatment, and appropriate alternatives.”

______________________________________________________________________________

4. Ask your family, friends, or other trusted individuals to be involved and help support you in your recovery. Yes, it’s hard to put ourselves in a situation where we feel like we’re burdening someone or losing our independence, even for a little while. Understand that these people are an integral part of your treatment team and contribute to the success of your recovery.

______________________________________________________________________________

5. Ask to speak with a hospital social worker if you have questions about insurance and billing related to your stay. The social worker is there to help clarify what your insurance covers and how much you may be required to pay. If you need assistance with payment, discuss the options available to you with the social worker before you leave as well.

______________________________________________________________________________

6. Ask to see the nurse manager or charge nurse if you’re experiencing ongoing issues with care or communication about your condition. The person in this role is responsible for helping patients and easing any misunderstanding or tensions that may arise during your stay.

______________________________________________________________________________

7. As you approach discharge, ask if you should continue taking any of the medications (including vitamins and supplements) you took before you were admitted. This information should be included in your discharge instructions, but take the time to fully understand this aspect of your care to avoid potentially disastrous or even fatal complications later.

______________________________________________________________________________

8. Ask the staff to show you and your caregivers how to perform any tasks prescribed for after you’ve left the hospital, especially any treatments that may require a special skill, such as changing a bandage or giving an injection. Ask the nurse or physician to remain in your room while you practice to ensure you’re doing it correctly.

______________________________________________________________________________

9. Ask your nurse or physician if it’s safe to perform ordinary tasks alone, like bathing, dressing, driving, or exercising. Make sure you’ve arranged for help with any of these activities before you leave the hospital.

______________________________________________________________________________

10. Ask your nurse or physician if you can or should use any medical equipment, such as a walker, brace, or health monitor, to help with your recovery and comfort. If the answer is yes, ask for assistance in obtaining these items before you leave or shortly after your return home.

______________________________________________________________________________

11. At the time of your discharge, ask the discharge nurse any questions you have about your discharge information. You should have been provided with printed discharge instructions. Don’t leave the hospital without obtaining these, reading them (or having them read to you), and making sure you understanding allof the information they cover.

______________________________________________________________________________

12. Ask about any follow-up appointments or additional testing. Take a moment now to record anything that’s already been scheduled or to schedule necessary appointments in the coming weeks.

______________________________________________________________________________

My hope is that regular use of this checklist will aid physicians in providing more streamlined and accessible care; will further educate patients in how to advocate for themselves; will help facilitate the best possible hospital experience for patients; and will reduce or eliminate some of the strain on the emotions, wallets, time, and energy of everyone involved. If we can ease the many demands of a hospital stay, we’re working in service a medical team’s goal: a successful patient recovery.

November 5, 2016

The Day Our World Changed Forever: When Rene Descartes Daydreamed

Portrait of René Descartes (1596-1650) by Fran’s Hals 1649. Statens Museum for Kunst, Coppenhagen

No one comes close to the ingenuity of the man who changed our fundamental understanding of nature (and ourselves) like the legendary French philosopher, scientist and mathematician Rene Descartes. He was not an inventor like Graham Bell or Galileo but he did something iconic. At a time in history when curiosity was suppressed in the name of conformity to the authority of religion and prevailing philosophy, he was the first among (the other was Francis Bacon) to assert that: “There is need of a method for finding out the truth.” As one of the history’s most intriguing minds, Descartes laid the foundation to reason and critical thinking.

There is need of a method for finding out the truth – René Descartes

What happens when a random flash of insight is coupled with an incredible capacity to comprehend and expand upon it? Rene Descartes life is filled with such impactful epiphanies. After determining that the typical path to a standard career wasn’t for him, Rene Descartes made a huge (and uncharacteristic) leap of faith by moving to Holland to join the military. Quickly realizing that he wasn’t necessarily cut out to be a soldier, Descartes made his mark as an engineer, relying on his keen mathematical sense rather than his physicality.

Years of intense education convinced him of only one thing – he could learn more by way of his own philosophy and studying science alone, without the distraction of textbooks and the authority of teachers. He was right. One seemingly ordinary day, as Descartes lay in bed daydreaming, he idly watched a fly buzz about his room. He came to a realization at that instance – the position of the fly at any time could be represented by three numbers – providing a distance from the three walls that met in the corner. We know these today as the Cartesian co-ordinates. In school, we learned that any point on a graph is represented by two numbers, corresponding to the distance along the x axis and up the y axis.

Years of intense education convinced him of only one thing – he could learn more by way of his own philosophy and studying science alone, without the distraction of textbooks and the authority of teachers. He was right. One seemingly ordinary day, as Descartes lay in bed daydreaming, he idly watched a fly buzz about his room. He came to a realization at that instance – the position of the fly at any time could be represented by three numbers – providing a distance from the three walls that met in the corner. We know these today as the Cartesian co-ordinates. In school, we learned that any point on a graph is represented by two numbers, corresponding to the distance along the x axis and up the y axis.

What did this mean? It meant that any shape could be represented with just a set of numbers related to one another by mathematical equation. The discovery, once published, transformed mathematics from its roots. This discovery made geometry able to be analyzed using algebra – the consequence of which went on to inspire both the theory of relativity and quantum theory in the twentieth century.

You might also remember using the beginning of the alphabet (a, b, c) to represent known quantities, and letters at the end of the alphabet (especially x, y, z) to represent the unknown quantities. It was Descartes’ who inscribed this language into mathematics.

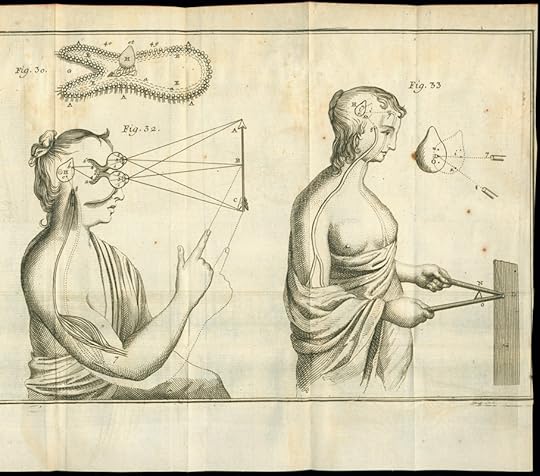

René Descartes, L’homme…. These drawings show the influence of Descartes’ knowledge of mathematics and geometry on his perception of how the body works.

At the age of 24, Descartes left the military in 1620 and sold his estate he’d inherited from his mother, using the proceeds to finance his continued dedication to independent studies. From 1629 to 1633, Descartes worked tirelessly on his treatise Le Monde ou Traité de la lumière, which detailed his ideas on physics. Unfortunately, in a seemingly knee-jerk reaction, Descartes stopped publication immediately upon hearing news of Galileo’s trial for heresy as he was convicted for Copernican beliefs. Luckily Descartes was later able to recycle much of his work in different projects.

René Descartes, L’homme…. “…I desire you to consider, I say, that these functions imitate those of a real man as perfectly as possible and that they follow naturally in this machine entirely from the disposition of the organs-no more nor less than do the movements of a clock or other automaton, from the arrangement of its counterweights and wheels.”

René Descartes, de Homine figuris. In this work Descartes posited that much human behavior can be explained by mechanical responses rather than the actions of the soul. Through a better knowledge of the mechanics of the body, he hoped to cure and prevent disease, and even to slow aging.

His first publication after retracting his original treatise was The Method, published in 1637, which covered meteorology, optics and geometry. Perhaps most profound about this particular work was that it was one of the first essays that attempted to explain meteorology with science and not with the tales of higher beings. While a man of God, Descartes showed us that life and the world around us can be understood through science – all the Earth’s inhabitants obeying laws of which can be determined through experimentation and keen observation. These observations, along with the thoughts and studies of Francis Bacon, laid the groundwork for the scientific method we know today.

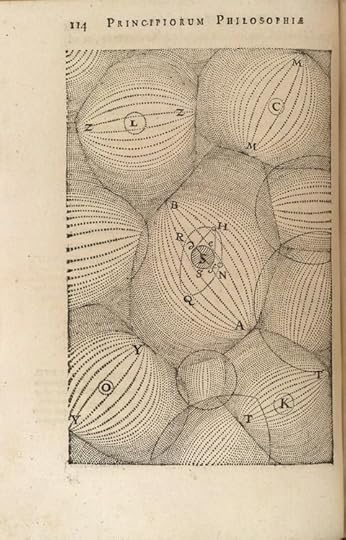

According to René Descartes (1596-1650), the universe operated as a continuously running machine which God had set in motion. Descartes argued that the universe was composed of a “subtle matter” he named “plenum,” which swirled in vortices like whirlpools and actually moved the planets by contact. Here, these vortices carry the planets around the Sun. The vortex theory did not require a gravitational force, so when Isaac Newton proposed a universal force of gravitation in 1687, many preferred Descartes’ explanation, because Newton’s force was not a mechanical force. However, Newton’s gravitational theory worked so well in explaining such matters as the tides, the shape of the earth, and the variation in pendulum clocks with changes in latitude, that cosmic vortices were in general dissipation by 1750, and Descartes’ swirling matter swirled itself into total and complete invisibility by the end of the century.

The Discourse on the Method (French: Discours de la méthode) is a philosophical and autobiographical treatise published by René Descartes in 1637. Its full name is Discourse on the Method of Rightly Conducting One’s Reason and of Seeking Truth in the Sciences. The Discourse on The Method is best known as the source of the famous quotation “Je pense, donc je suis” (“I think, therefore I am”), which occurs in Part IV of the work. (The similar statement in Latin, Cogito ergo sum, is found in Part I, §7 ofPrinciples of Philosophy.)

October 11, 2016

Nobody Wants to Read Your Shit – Steven Pressfield’s insanely brilliant advice to writers

Steven Pressfield offers the most practical and remarkable advice to writers, young and old, in his Nobody Wants to Read Your Sh*t – guidance that applies to any creative endeavor, really:

Sometimes young writers acquire the idea from their school that the world is waiting to hear what they’ve written. They get this idea because their teachers had to read their essays or term papers or dissertations.

In the real world, no one is waiting to read what you’ve written.

Slightly unseen, they hate what you’ve written. Why? Because they might have to actually read it.

According to Pressfield, adopting this approach actually changes your mindset to produce better work. Antonio Damasio wrote in The Feeling of What Happens, “Sometimes we use our minds not to discover facts, but to hide them.” In a bold yet subtle way, Pressfield asserts:

It isn’t people are mean or cruel. They’re just busy. Nobody wants to read your shit.

What’s the answer?

Streamline your message. Focus it, and pare it down to its simplest, clearest, and easy to understand form.

Make its expression fun. Or sexy or interesting or scary or informative. Make it so interesting that a person would have to be crazy NOT to read it.

Apply that to all forms of writing or art or commerce.

The book becomes at once a tool of self-discovery as much as an instructional guide to better writing. He explains:

When you understand that nobody wants to read your shit, your mind becomes powerfully concentrated. You begin to understand that writing/reading is, above all, a transaction. The reader donates his time and attention, which are supremely valuable commodities. And in return you the writer must return something worthy of his gift to you.

The book is far from the typical ego-stroking run-of-the-mill how-to’s and serves as an essential companion for anyone laboring in the art of making something new.

When you understand that nobody wants to read your shit, you develop empathy.

With this, Pressfield brings life to the timeless wisdom of what makes an artist’s skill blossom and become cherished in the minds of audience.

You acquire the skill that is indispensable to all artists and entrepreneurs – the ability to switch back and forth in your imagination from your own point of view as a writer/painter/seller to the point of view of your reader/gallery-goer/customer. You learn to ask questions with every sentence and every phrase: Is this interesting? Is it fun or challenging or inventive? Am I giving the reader enough? Is she bored? She is following where I want to lead her?

Above all, this becomes not only a tool of accountability but a guide post to keep the artist or entrepreneur moving forward in the face of self-doubt and uncertainty.

Steven Pressfield

August 3, 2016

Hidden Meaning of Karma: Timeless Wisdom from Vivekananda, D.T. Suzuki and Madam Blavatsky

Karma is a Sanskrit term, commonly translated to mean deed. What it really embodies is three processes – thinking, speaking and action, essentially encompassing nearly all human activity.

Dharma Comic by Leah Pearlman

The foundation of the belief in karma stems from one premise: As long as we look upon our individual lives as isolated, finite events beginning with the birth of the body and ending with its death, we will not find the explanation of our circumstances. Why is there injustice? Why is there misery? Suffering? However, when we connect our present lives with our past and our future, viewing our life as a looped continuum of eternal existence, we might find meaning in why all things happen in our life. Our present is the result of our past, and our future will be the result of our present.

This belief asserts that what we experience in this finite lifetime is only a blip in the continuum of the entire spectrum of our total existence. A simplified analogy was offered: Suppose our life began each morning and lasted for 24 hours. If we disconnect the life of today from that of yesterday and that of tomorrow and judge each day by its results, we would find poor compensation for our daily endeavors. Furthermore, it would seem terribly unjust to have our life falling on a gloomy, unpleasant day filled with tragedy, while another life fell on the following bright and shiny day filled with luck and bliss. We would not be able to justify the fragments of life.

On a more contemporary commentary in the same lines: “How we spend our days is, of course, how we spend our lives,” Annie Dillard wrote in her timeless The Writing Life.

Swami Vivekananda in Belgaum, India, 1892

Karma could also be viewed as a form of glorified rationalization amounting to, “You suffer because …” Obviously, this conviction cannot be scientifically proven – it is not a testable hypothesis. However, if we make a leap of faith in this assumption without restrictions, a great deal of existential confusion seems to suddenly make sense. Reckoning from this standpoint, we may find satisfactory reasons to some of the perplexing problems and complicated affairs of human life. We come to realize how our choices and actions shape who we become.

Indian monk and philosopher Swami Vivekananda in his timeless wisdom, Karma Yoga: The Yoga of Action published in 1896, explains:

Every thought that we think, every deed that we do, after a certain time becomes fine, goes into seed form, so to speak, and lives in the fine body in a potential form and after a time it emerges again and bears its results. These results condition the life of man. Thus he molds his own life. Man is not bound by any other except that which he makes for himself. Our thoughts, our words, and deeds are the threads of the net which we throw around ourselves, for good or for evil. Once we set in motion a certain power, we have to take the full consequence of it. This is the law of karma.

The idea of karma is in accordance with the popular saying, “Heaven helps those who help themselves.” A person, therefore, is not to be judged by the sufferings he or she undergoes, but by his/her capacity to rise above – ultimately our attitude in the face of adversity.

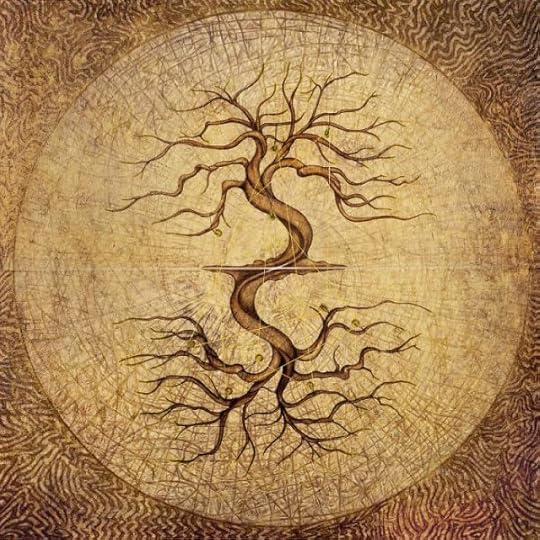

“Karmic” is a painting by Horacio Cardozo. Its main concept depicts our past and present lives as a continuum of cosmic energy represented by the interconnected trees. They keep bound by a thin golden string that runs across ten pulleys hanging on both trees, which represent the tension of causes and effects throughout our lives.

To take this concept up a notch, karma comes down to one thing: Essentially the law of cause and effect pervades everything in the manifested world. Furthermore, understanding cause and effect entails recognizing the very philosophy of our lives, our belief in a super-natural being governing the fate of our lives and the role of freewill.

For those of us who are believers, it is the tug of war between the sovereignty of God and man’s freedom of action that result in our mundane conflict. If we relegate complete dominance of our lives to a supreme being, it makes God responsible for man’s vices and suffering – the all-powerful dictator. Such that, all that happens to us is predetermined by God; concluding that only some receive grace and others are doomed to live in everlasting misery.

The only way that sovereignty of a super-natural being and freedom of man come together is through a more unified understanding of our relationship with this Supreme Being – a non-duality approach. Non-duality means ‘not two’ and points to an understanding of the essential oneness, completeness and unity of life, a wholeness which exists here and now, void of any apparent separation.

Buddhist philosopher D. T. Suzuki says,

Where dualism holds good, this karma does not apply.

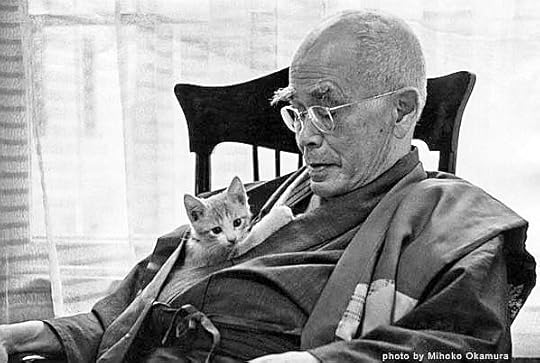

“A ZEN LIFE – D.T. Suzuki” is a documentary about Daisetz Teitaro Suzuki (1870-1966), credited with introducing Zen Buddhism to the West.

It is thus only through a non-dualistic view of the world that the idea of karma makes sense. As Madam Blavatsky, co-founder of the Theosophical Society in 1875 observed,

Karma is that unseen and unknown law which adjusts wisely, intelligently, and equitably each effect to its cause, tracing the latter back to its producer.

July 29, 2016

When Two Giants Met – Rabindranath Tagore and Albert Einstein

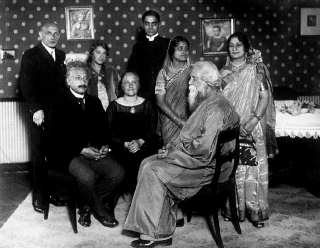

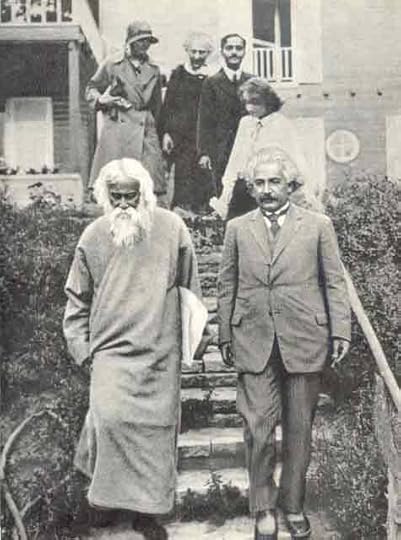

Albert Einstein, his wife Elsa and his stepdaughter Margot with Rabindranath Tagore, Pratima Devi, Tagore‘s daughter-in-law, and Professor and Mrs. Mahalanobis in Berlin, 1930

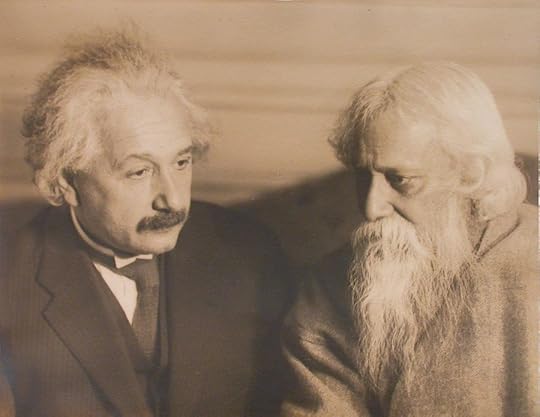

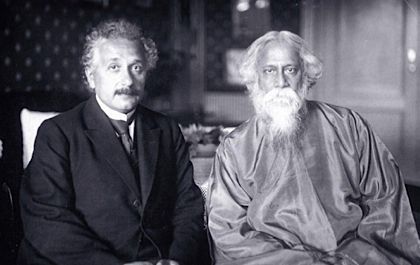

When the two scintillating geniuses of the East and West – Rabindranath Tagore and Albert Einstein – met in 1930, Dimitri Marianoff, a relative of Einstein, described the conversation “as though two planets were engaged in a chat.”

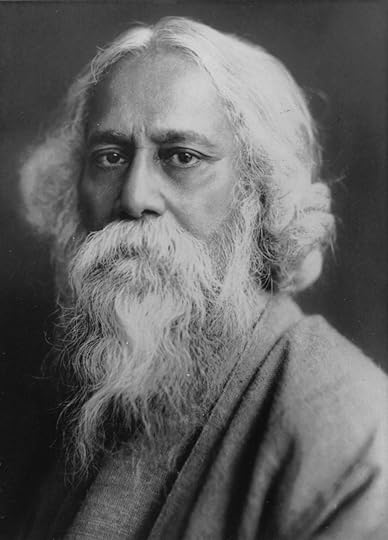

Rabindranath Tagore was a genius polymath of India. A prolific poet, play writer, and songwriter, he wrote 2,000 in his lifetime, one of which was adopted as the national anthem of India. He was also famously given a Nobel Prize for literature in 1913 for his collection of poems Gitanjali. In 1915, Tagore was knighted but he returned it after the Amritsar massacre in 1919.

Albert Einstein is the better known of the two to the world, who received Nobel Prize in 1921 not for his famous Theory of Relativity but for the lesser known theories on photoelectric effect. Einstein searched for universal truths that could be expressed through mathematical equations – an objective verification was required for him to ascertain truth. To him, every theory had to have mathematical simplicity, structure, and order. He not only wanted to understand the “mind of God” but to deduce it into a unified theory.

Rabindranath Tagore (7 May 1861 – 7 August 1941)

Tagore visited Einstein’s house in Caputh, near Berlin, on July 14, 1930. The discussion between the two great men was recorded and subsequently published in a 1931 issue of Modern Review. Einstein with his signature frizzy hair was 50; Tagore with long, flowing beard was 70.

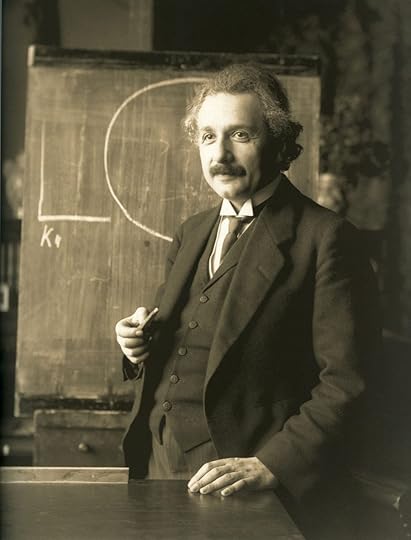

Einstein 1921 by F Schmutzer

Interestingly, when they met, Tagore did not know German and Einstein’s English was too weak to converse. Hence they had to use interpreters for conversation.

Neither Tagore nor Einstein was happy with the recorded conversation, as the translations lost their charm. So, they themselves corrected their parts before making the conversation public.

When Albert Einstein and

Rabindranath Tagore met in 1930

In the afternoon of July 14, 1930, Tagore went to meet Einstein at his house at Kaputh, near Postdam, Germany

Here is an excerpt of their conversation that started with the most fundamental existential question, “Nature of Reality,” the interplay of chance and predetermination. They went on to discuss the ordinary everyday events relating to family, the youth movement of Germany, and finally ended with discussing classical music.

EINSTEIN: Do you believe in the Divine as isolated from the world?

TAGORE: Not isolated. The infinite personality of Man comprehends the Universe. There cannot be anything that cannot be subsumed by the human personality, and this proves that the Truth of the Universe is human Truth.

I have taken a scientific fact to explain this — Matter is composed of protons and electrons, with gaps between them; but matter may seem to be solid. Similarly humanity is composed of individuals, yet they have their interconnection of human relationship, which gives living unity to man’s world. The entire universe is linked up with us in a similar manner, it is a human universe. I have pursued this thought through art, literature and the religious consciousness of man.

EINSTEIN: There are two different conceptions about the nature of the universe: (1) The world as a unity dependent on humanity. (2) The world as a reality independent of the human factor.

TAGORE: When our universe is in harmony with Man, the eternal, we know it as Truth, we feel it as beauty.

EINSTEIN: This is the purely human conception of the universe.

TAGORE: There can be no other conception. This world is a human world — the scientific view of it is also that of the scientific man. There is some standard of reason and enjoyment which gives it Truth, the standard of the Eternal Man whose experiences are through our experiences.

EINSTEIN: This is a realization of the human entity.

TAGORE: Yes, one eternal entity. We have to realize it through our emotions and activities. We realized the Supreme Man who has no individual limitations through our limitations. Science is concerned with that which is not confined to individuals; it is the impersonal human world of Truths. Religion realizes these Truths and links them up with our deeper needs; our individual consciousness of Truth gains universal significance. Religion applies values to Truth, and we know this Truth as good through our own harmony with it.

EINSTEIN: Truth, then, or Beauty is not independent of Man?

TAGORE: No.

EINSTEIN: If there would be no human beings any more, the Apollo of Belvedere would no longer be beautiful.

TAGORE: No.

EINSTEIN: I agree with regard to this conception of Beauty, but not with regard to Truth.

TAGORE: Why not? Truth is realized through man.

EINSTEIN: I cannot prove that my conception is right, but that is my religion.

TAGORE: Beauty is in the ideal of perfect harmony which is in the Universal Being; Truth the perfect comprehension of the Universal Mind. We individuals approach it through our own mistakes and blunders, through our accumulated experiences, through our illumined consciousness — how, otherwise, can we know Truth?

EINSTEIN: I cannot prove scientifically that Truth must be conceived as a Truth that is valid independent of humanity; but I believe it firmly. I believe, for instance, that the Pythagorean theorem in geometry states something that is approximately true, independent of the existence of man. Anyway, if there is a reality independent of man, there is also a Truth relative to this reality; and in the same way the negation of the first engenders a negation of the existence of the latter.

TAGORE: Truth, which is one with the Universal Being, must essentially be human, otherwise whatever we individuals realize as true can never be called truth – at least the Truth which is described as scientific and which only can be reached through the process of logic, in other words, by an organ of thoughts which is human. According to Indian Philosophy there is Brahman, the absolute Truth, which cannot be conceived by the isolation of the individual mind or described by words but can only be realized by completely merging the individual in its infinity. But such a Truth cannot belong to Science. The nature of Truth which we are discussing is an appearance – that is to say, what appears to be true to the human mind and therefore is human, and may be called maya or illusion.

EINSTEIN: So according to your conception, which may be the Indian conception, it is not the illusion of the individual, but of humanity as a whole.

TAGORE: The species also belongs to a unity, to humanity. Therefore the entire human mind realizes Truth; the Indian or the European mind meet in a common realization.

EINSTEIN: The word species is used in German for all human beings, as a matter of fact, even the apes and the frogs would belong to it.

TAGORE: In science we go through the discipline of eliminating the personal limitations of our individual minds and thus reach that comprehension of Truth which is in the mind of the Universal Man.

EINSTEIN: The problem begins whether Truth is independent of our consciousness.

TAGORE: What we call truth lies in the rational harmony between the subjective and objective aspects of reality, both of which belong to the super-personal man.

EINSTEIN: Even in our everyday life we feel compelled to ascribe a reality independent of man to the objects we use. We do this to connect the experiences of our senses in a reasonable way. For instance, if nobody is in this house, yet that table remains where it is.

TAGORE: Yes, it remains outside the individual mind, but not the universal mind. The table which I perceive is perceptible by the same kind of consciousness which I possess.

EINSTEIN: If nobody would be in the house the table would exist all the same — but this is already illegitimate from your point of view — because we cannot explain what it means that the table is there, independently of us.

Our natural point of view in regard to the existence of truth apart from humanity cannot be explained or proved, but it is a belief which nobody can lack — no primitive beings even. We attribute to Truth a super-human objectivity; it is indispensable for us, this reality which is independent of our existence and our experience and our mind — though we cannot say what it means.

TAGORE: Science has proved that the table as a solid object is an appearance and therefore that which the human mind perceives as a table would not exist if that mind were naught. At the same time it must be admitted that the fact, that the ultimate physical reality is nothing but a multitude of separate revolving centres of electric force, also belongs to the human mind.

In the apprehension of Truth there is an eternal conflict between the universal human mind and the same mind confined in the individual. The perpetual process of reconciliation is being carried on in our science, philosophy, in our ethics. In any case, if there be any Truth absolutely unrelated to humanity then for us it is absolutely non-existing.

It is not difficult to imagine a mind to which the sequence of things happens not in space but only in time like the sequence of notes in music. For such a mind such conception of reality is akin to the musical reality in which Pythagorean geometry can have no meaning. There is the reality of paper, infinitely different from the reality of literature. For the kind of mind possessed by the moth which eats that paper literature is absolutely non-existent, yet for Man’s mind literature has a greater value of Truth than the paper itself. In a similar manner if there be some Truth which has no sensuous or rational relation to the human mind, it will ever remain as nothing so long as we remain human beings.

EINSTEIN: Then I am more religious than you are!

TAGORE: My religion is in the reconciliation of the Super-personal Man, the universal human spirit, in my own individual being.

July 15, 2016

The Genius of Ramanujan: What it takes to live among common mortals

German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer observed in his 1818 masterwork The World as Will and Representation: “Talent is like the marksman who hits a target which others cannot reach; genius is like the marksman who hits a target … which others cannot even see.”

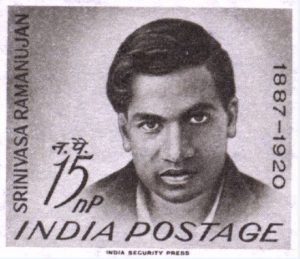

Ramanujan commemorative postage stamp issued in India in 1962. This was his passport photo taken in 1919 on his way back to India. “He looks rather ill,” G. H. Hardy wrote when he first saw the photo in 1937, “but he looks all over the genius he was” – Master and Fellows of Trinity College, Cambridge

These are the individuals who dedicate their lives to passionate journeys doing whatever it is they love to do – treating the universe as an interesting playing field. Nothing more, nothing less. One such individual is little-known, self-taught mathematician Srinivasa Ramanujan, who in his short lifespan of merely 32 years, made some revolutionary and surprising discoveries.

One day, the math teacher pointed out that any number divided by itself was one: Divide three fruits among three people, he was saying, each would get one…

So Ramanujan piped up: But is zero divided by zero also one? If no fruits are divided among no one, will each still get one?

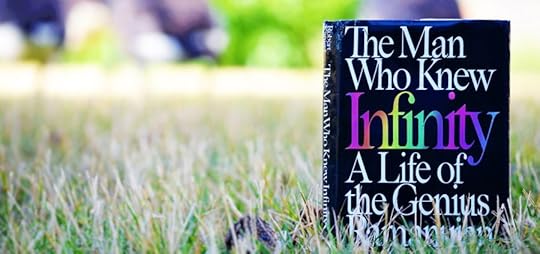

This was Ramanujan’s question to his teacher when he was merely a the third grader. Robert Kanigel’s 1991 biography of Ramanujan, The Man Who Knew Infinity, from which the movie was later adapted, provides the most authentic account of Ramanujan’s early life.

Ramanujan performed his calculations as authentic as it gets — with chalk on slate, scrap paper, scribble on sand, whatever he could get his hands, or mind, on. His childhood best friend proclaimed him a genius the first time he walked in Ramanujan’s room, seeing all of the notes upon the walls. Unable to afford notebooks, he took to a large slate, using his own elbow as an eraser. “My elbow is making a genius of me,” Ramanujan would joke.

The Man Who Knew Infinity: A Life of the Genius Ramanujan. By Robert Kanigel

Being a genius of a certain order also comes with some penalties. Ramanujan’s unique obsession with mathematics made it especially difficult to fit in.

As Schopenhauer observed that individuals of extraordinary genius often fall victim to quite lonely course of life:

The common mortal, that manufacture of Nature which she produces by the thousand every day, is, as we have said, not capable, at least not continuously so, of observation that in every sense is wholly disinterested, as sensuous contemplation, strictly so called, is. He can turn his attention to things only so far as they have some relation to his will, however indirect it may be…

The man of genius, on the other hand, whose excessive power of knowledge frees it at times from the service of will, dwells on the consideration of life itself, strives to comprehend the Idea of each thing, not its relations to other things; and in doing this he often forgets to consider his own path in life, and therefore for the most part pursues it awkwardly enough.

By the time Ramanujan got to college, all he wanted to do was mathematics, failing all of his other classes. At one point, so frustrated with the seemingly arbitrary requirements of college, he ran away, causing his mother to send a missing-person letter to the newspaper:

‘A Missing Boy’, published in September, 1905 in a newspaper. It appeals for the public’s help in tracing “a Brahmin boy of the Vaishnava (Thengalai) sect, named Ramanujam, of fair complexion and aged about 18 years” who had “left his [Kumbakonam] home on some misunderstanding.”

As a college dropout from a poor family, Ramanujan’s future seemed bleak. He depended on the kindness of his friends and showcased his mathematical discovery-filled notebooks to patrons who just might support his work. When Ramanujan’s friends and acquaintances couldn’t land him a scholarship, Ramanujan started looking for jobs, working as an accounting clerk for the Port of Madras (now Chennai) in 1912.

Eventually, he wrote to mathematicians in Cambridge seeking validation of his work. Twice he wrote with no response; on the third try, he finally got an answer.

In 1913 a mathematician named G. H. Hardy in Cambridge, England received a package of papers with a cover letter that began:

Dear Sir,

I beg to introduce myself to you as a clerk in the Accounts Department of the Port Trust Office at Madras on a salary of only £20 per annum. I am now about 23 years of age….

and explained how he had made “startling” progress and solved the age-old problem of the distribution of prime numbers. Ramanujan concluded the letter with a heart-rending request:

Being poor, if you are convinced that there is anything of value I would like to have my theorems published…. Being inexperienced I would very highly value any advice you give me. Requesting to be excused for the trouble I give you.

Yours truly,

S. Ramanujan.

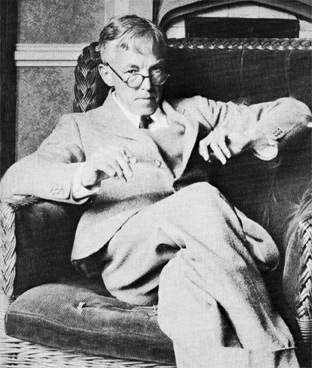

Something about the 11 pages of technical formulas made Hardy take a second look, and show it to his collaborator J. E. Littlewood. Hardy wrote,

Some of the formulae defeated me completely. I have never seen anything in the least like them before. A single look at them is enough to show that they could only be written down by a mathematician of the highest class.

After a few hours, they concluded that the results “must be true because, if they were not true, no one would have had the imagination to invent them.”

Godfrey Harold “G. H.” Hardy (7 February 1877 – 1 December 1947). In an interview by Paul Erdős, when Hardy was asked what his greatest contribution to mathematics was, Hardy unhesitatingly replied that it was the discovery of Ramanujan. He called their collaboration “the one romantic incident in my life.”

Hardy’s colleague, Bertrand Russell wrote that by the next day he “found Hardy and Littlewood in a state of wild excitement because they believe they have found a second Newton, a Hindu clerk in Madras making 20 pounds a year.”

In another letter to Hardy, Ramanujan confessed that he really just wanted someone to verify his results—so he’d be able to get a scholarship, since “I am already a half starving man. To preserve my brains I want food…”

Hardy wanted Ramanujan to come to England, which Ramanujan’s mother resisted as a matter of principle – high-caste Indians were not to travel to foreign lands. Luckily, she eventually agreed to let him go.

Ramanujan prepared for Europe with a new Western-inspired wardrobe, mastery of eating with knives and forks and learning how to tie a tie. He boarded a ship for England, sailing up through the Suez Canal, and arrived to London.

Although he tried his best to conform to the norms of the new society, his struggle to fit within the expectations of established academia seemed impossible. Ramanujan announced that he’d “changed [his] plan of publishing [his] results”. He said that since coming to England he had learned “their methods,” and was “trying to get new results by their methods so that I can easily publish these results without delay.”

The stark contrast between Hardy and Ramanujan is akin to that of many main-stream academicians and the true innovators who developed their own paths.

Hardy was no ordinary mathematician. He was credited with reforming British mathematics by bringing rigor into it. A man with natural affinity for numbers, Hardy’s papers were good examples of state-of-the-art mathematical craftsmanship. By 1910, Hardy had fell into a routine of normalcy as a Cambridge professor. He lived within the typical bounds of society while spending time practicing his mathematics.

Whereas, Ramanujan was a self-taught, poor Brahmin Indian with no formal education, who had a belief that fell far outside the bounds of organized study. He once told Hardy that, “A formula had no meaning unless it expressed a thought of God.”

While mathematicians in general were trained to systematically prove each of their theorems with extensive methodology, Ramanujan was a man of intuition. Once, Kaniglel writes, Ramanujan was asked about a new equation he had derived. His reply was that it was a Hindu goddess who had appeared in his dream and helped him solve that problem.

Hardy wrote:

Here was a man who could work out modular equations, and theorems of complex multiplication, to orders unheard of, whose mastery of continued fractions was, on the formal side at any rate, beyond that of any mathematician in the world … It was impossible to ask such a man to submit to systematic instruction.

[…]

so I had to try to teach him, and in a measure I succeeded, though I obviously learnt from him much more than he learnt from me.

When Hardy saw Ramanujan’s “fast and loose” approach to the infinite limits and the like, his reaction was a need to “tame” Ramanujan and educate him in the structured European methodology.

Rigor in analysis defined Hardy’s work, while Ramanujan’s results were (as Hardy put it) “arrived at by a process of mingled argument, intuition, and induction, of which he was entirely unable to give any coherent account.”

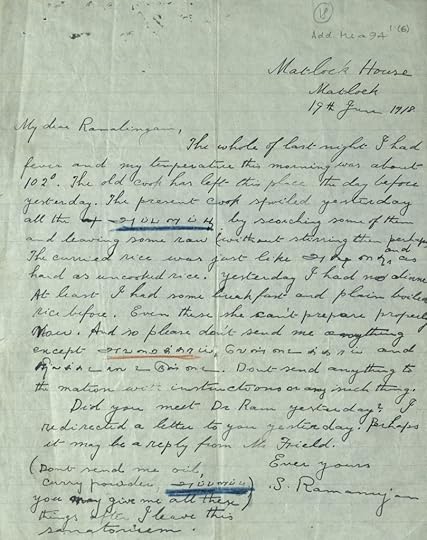

Pages from one of Ramanujan’s last letters.

As for his place in the world of Mathematics, Professor Bruce C. Berndt of the University of Illinois wrote:

Paul Erdos has passed on to us Hardy’s personal ratings of mathematicians. Suppose that we rate mathematicians on the basis of pure talent on a scale from 0 to 100, Hardy gave himself a score of 25, Littlewood 30, Hilbert 80 and Ramanujan 100.

Ramanujan couldn’t easily fit in the constraints of societal or academic expectations because his ideas were much bigger than the limitations imposed by convention.

Ramanujan (centre) with other graduates at Trinity College in March 1916.

Hardy-Ramanujan’s collaboration in England was mathematically productive. Cambridge granted Ramanujan a Bachelor of Science degree “by research” in 1916, and he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society (the first Indian to be so honored) in 1918. His accomplishments were followed quickly by a stark decline in his health as a result of the English winter and the difficulties of adhering to strict dietary rules of his caste in the face of wartime shortages. In 1917 he was hospitalized and nearly died. By late 1918 his health had improved; he returned to India in 1919. But his health failed again, and he died the following year year.

Letter from Ramanujan to friend. Courtesy: Trinity College Cambridge.

In reply to the above letter, his friend wrote:

My dear Ramanujan,

I was exceedingly grieved to have your painful letter. Sorry to hear that the new cook is a failure as far as you are concerned. Now then, I will have to be a bit harsh with you. I am impressed with you being so particular about your palate. But you’ll have to choose between controlling your palate and killing yourself.

Surely some of the greatest minds like Isaac Newton and Albert Einstein lived through their 70’s and 80’s, but their best works were actually produced in their 20’s. These were the individuals who didn’t count their life by the number of years lived, but the contribution they made to the advancement of human progress.

DOCUMENTARY ON RAMANUJAN – Mathematical Genius

A formula had no meaning unless it expressed a thought of God

July 7, 2016

Understanding Teenage Mind: Essential Wisdom For Everyone

Teens go through a period of “invisibility,” naively assuming that they are never vulnerable to harm.

Teenage Love by Xhon Dervishi

We have all been there. Some of us are just now adapting to this phase of our children’s life. In many ways, teenage years represent the most transformative and sometimes tumultuous phase of our lives. Teenagers aren’t quite an adult yet, but are no longer children either. Almost as difficult as this time can be for teens, it is as seemingly impossible for the parents to navigate. For some parents, it’s as if their child has been possessed by some overly emotional spirit. Suddenly they feel like they don’t know their own child anymore and the dynamics of the parent-child relationship are thrown completely off kilter.

Teenagers often have ambitions to fly off to a new, larger world. To this effect, Stephen King observed, “If you liked being a teenager, there’s something really wrong with you.” Scientists have discovered that there are abrupt and rapid growth of certain cells within the frontal lobe (the part that sits behind your forehead) of the brain in early teenage years, around the age of 15.

Another complicated characteristic of teens is the tendency to engage in high-risk behaviors. Teens go through a period of “invisibility,” naively assuming that they are never vulnerable to harm. The neuro-hormonal changes can cause drastic behavioral and mood swings at times and throw the parent for a loop.

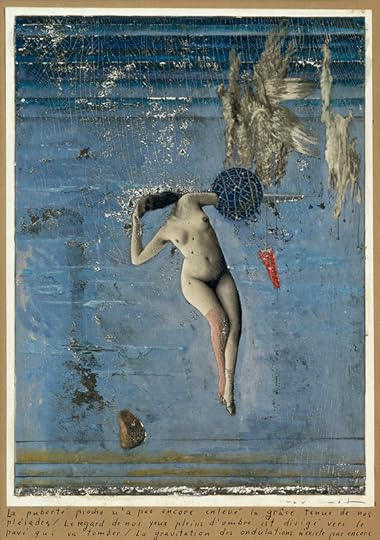

Approaching Puberty (The Pleiades), 1921by Max Ernst. Virginity and lasciviousness, the celestial and the earthly, floating and falling, grace and destruction—in this intriguing work Max Ernst holds a wealth of opposites in balance. Click image.

Puberty is meant to be a phase in our lives during which we blossom from small, dependent creatures into prepared, self-sufficient adults capable of propagating life. From a biological standpoint, this is the most important juncture in the life of humans. Any malfunction in this process and we risk losing the ability to pass on our genes.

Because of the evolutionary pressure involved in preparing us for reproduction, puberty is probably the most tumultuous phase of human life.

Our minds, at this time, are constantly obsessed with instant gratification, persistently seeking the promise of immediate pleasure and psychological security. This is our minds’ way of pressuring us to reproduce—by forcing us to make sexual gratification our top priority. For this reason, the desire to breed remains the most powerful impulse in all of nature. Friction ignites between teens and their parents when parents fail to recognize the teenage minds’ pleasure-obsessed makeup, particularly because an adult, who’s already exited puberty, will often have long subdued these seemingly juvenile attachments to transitory and immediate pleasures.

The incapacity to empathize with our pubescent children is an example of the stark evolution of the mind throughout the different phases of life. Our minds’ desires run the gamut at each stage of the aging process. As we grow, our priorities shift from the need for instant gratification (brought on by the necessity to spread our legacy) to the desire to nurture our offspring.

Shifting Priorities

Our cravings are entirely strategic—the mind’s sophisticated way of preserving its form. When we reach the phase of reproductive capacity and essentially copy ourselves into our children, we experience a level of caring for our offspring previously foreign to us. We care for our children even more deeply than we care for ourselves.

This is how our mind functions. All this is part of being human; a human expression. Unless we understand the nature of our mind, why and how it devises various strategies at different phases of our life to thrive, we will overcome by the more difficult stages of life such as puberty.

The question is: Why are these abrupt and complex changes associated with our teenage years? To understand this is to recognize the bigger picture of our mind.

Recognizing Stages

Our life cycle is characterized by seamless stages, each of which allows our minds to develop different strategies with one overarching goal: Keep living.

Butterflies, for instance, experience a larval stage. The caterpillar, after hatching from its egg, doesn’t stop eating for about two to three weeks, during which time it grows tremendously.When physical maturation is achieved, the caterpillar enters adulthood, and numerous hormonal changes lead to a biochemical disassembly of its current form, transforming it into a beautiful butterfly. The creative destruction of one form births another. The young butterfly will now seek out a mate and allow the cycle of life to repeat once again. Bernard Heinrich, an eminent biologist, writes: “The radical change that occurs does indeed arguably involve death followed by reincarnation.”

It appears as though one form (the caterpillar) completely transforms itself into another form (the butterfly) in a blatant example of how the core of life devises many survival strategies in order to actively participate in this web of nature. Nearly identical to the stages of human life, caterpillars possess a strong capacity to thrive, specialized for little else but feeding during the period of preparation before the next phase of life, similar to children. Like adults, butterflies are fine-tuned for flight and reproduction, comparable to an adult leaving the nest and gearing up for procreation.

The human life cycle is less blatant, but we can still see how our survival strategies are typified at each stage. The first is comprised of our feed and grow stage, the second is our procreation stage, and the third is our reproductive-capacity stage. Separating these first two distinct periods is the transient phase of puberty. While this time is considered to be simply transitory, it is actually a prominent point with its own unique physical and mental characteristics.

What the teenager learns and does during this evolution of the brain combined with their own genetic heritage will consolidate the wiring in certain parts of the brain. So, if the teen is learning skills such as music or math, those are the connections that are hardwired and will retain their connections for years down the line, even if they are not actively using them later in life.

Therefore, it’s the duty of the caregivers to be practice extreme patience and continue to nurture those skills that are conducive to the overall development of the teenage mind, not only for the time being, but for many years to come for a fruitful future.

If the teen is learning skills such as music or math, those are the connections that are hardwired and will retain their connections for years down the line, even if they are not actively using them later in life.

Keys to Nurturing the Relationships

Knowing the facts behind teenage angst is key to successful parenting during these years.

The three things that will ease the tension between adults and the adults-in-transitions:

Empathize, as often as possible, remembering how it felt for you to struggle as a teenager.

Encourage your teenager to channel their energy and emotions into creative, productive outlets – help them find hobbies to help occupy and shape their quickly changing minds.

Listen first – talk to your teen, not at them.

This complex period can make or break your bond with your child, so be prepared to weather the storm by arming yourself with the knowledge of why your teen is behaving and reacting certain ways. Allow the teenage years to come and go – fight through them, and then move on!

In a profoundly loving and luminous letter, sociologist and civil rights activist W.E.B. Du Bois, the first African American person to receive a doctorate from Harvard wrote to his teenage daughter Yolande in 1914,

Remember that most folk laugh at anything unusual, whether it is beautiful, fine or not. You, however, must not laugh at yourself. You must know that brown is as pretty as white or prettier and crinkley hair as straight even though it is harder to comb. The main thing is the YOU beneath the clothes and skin — the ability to do, the will to conquer, the determination to understand and know this great, wonderful, curious world. Don’t shrink from new experiences and custom. Take the cold bath bravely.W. E. B.” Du Bois (February 23, 1868 – August 27, 1963) was an American sociologist, historian, civil rights activist.

June 30, 2016

Why Early Rising is Good for Your Health: Lessons from Aristotle to Latest Science

Benjamin Franklin (January 17, 1706 – April 17, 1790) defines early rising as before sunrise after six to seven hours of sleep.

Benjamin Franklin (January 17, 1706 – April 17, 1790) defines early rising as before sunrise after six to seven hours of sleep.

June 24, 2016

Question Everything: How Francis Bacon Changed Our Study of Nature Forever

In the ancient past, material knowledge and spirituality went hand in hand, in fact all knowledge was a synthesis of the two. Medical knowledge was no different.

Art by Freydoon Rassouli. In many ancient traditions, dreaming is understood to be the link between matter and spirit.

Matter was studied and understood through this loaded concept called the spirit. But this led to much speculation, numerous doctrines and theories came into being. Lineages were established – in the west, the Aristotle’s theories dominated philosophy. Hippocrates and Galen’s theories dominated medicine. Medical books were frequently written with terms pertaining to the union of the soul and flesh.

But after a while, certain elements of the religious establishment started to control the study of every aspect of matter, every aspect of the study of nature. Doctrines became rigid; study of human biology was stalled and there was no advancement in medicine. Dissections and experiments were prohibited in the name of religion. All knowledge was controlled by the precepts of what religions preached. The spirit side was dominating the study of matter.

Up until the 17th century, all the work done was the work of great masters like Aristotle, Plato, Hippocrates, and Galen – the knowledge passed down by generations of sincere followers of past wisdom.

But in the 17th century, several individuals found this approach was not working to understand the bodily functions. So, we had to separate spirit from matter. Matter has to be studied using quantifiable evidence – the human body was seen as a collection of mechanisms which could be studied using chemical reactions, physical laws, and mathematical equations.

Spirituality and philosophy are concerned with subjective experience so cannot be quantified, and therefore not a subject of scientific study. Spirit and matter, therefore, cannot go hand in hand in the study of nature. The separation thus happened around 17th century.

Old methods should die, writes Francis Bacon, who many attribute as the founder of the scientific approach. He proposed methods for a new beginning. He listed unsolved problems in every field of human endeavor. He thus became the prophet of this new institution called science.

Francis Bacon actually called this the “new philosophy.” This was different from any other philosophy because it aimed at practice rather than theory, in search of proof, rather than a doctrine, something concrete rather than speculation. Knowledge, according to him is not an opinion, but a work that has to be verified. Knowledge should have utility and power, he declared. Here, for the first time, was the voice and tone of modern science.

Francis Bacon, Viscount St Alban by Unknown artist oil on canvas, after 1731 (circa 1618). © The National Portrait Gallery, London.

Science is aimed at practice rather than theory, in search of proof, rather than a doctrine, something concrete rather than speculation.

The scientific method emerged as the universal equalizer for all those who wanted to study nature. One peculiarly unique attribute about this scientific method is its process of investigation. The celebrated physicist Richard Feynman candidly articulated how the experimental method works:

Suppose if your experiments prove your theory to be true, it doesn’t mean that your guess is absolutely right. It is simply not proved wrong. Because in the future, there may be a wider range of experiments and a wider range of computations that may prove your theory is wrong…. You can never prove a theory to be right.

Feynman’s assessment remains true. Today, a typical scientific discovery relies on three factors: First, a hypothesis (an intelligent guess); second, the ability to test and re-test the hypothesis in a reputable, controlled experiment; and third, publication of the results. Anyone who correctly follows the steps laid out in a particular study design, no matter who they are, must be able to say, “Yes, I got the same result.”

Since then every claim we make had to be put to the test. For instance, if we claim that brushing our teeth twice a day, once in morning and once before bedtime, is better for the health of teeth, this claim should be validated. Only if it passes the grind of scientific study is it deemed appropriate to follow this practice – of brushing twice a day. If it fails, the habit would be simply discarded.

In this world of science, there is no room for existential questions such as – why have we come into this world? What is the nature of self? What is the goal of life? What is the basis of ethics and morality? These existential questions cannot be quantifiable and therefore cannot be tested.

The words spirit, or god were never to be written in any respectable scientific journal.

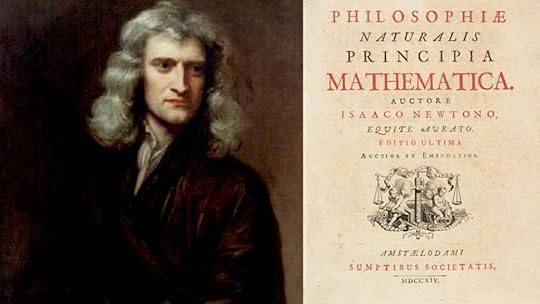

This was the birth of what we call Classical Mechanics, as founded by Isaac Newton. Nature behaves according to certain predetermined laws and by discovering those laws we can understand nature and its functions. “Spirit” has no place in this study. In other words, there are laws in nature, but a law maker is not necessary for those laws to function.

Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica – Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy is a work in three books by Isaac Newton, in Latin, first published 5 July 1687. The Principia states Newton’s laws of motion and Newton’s law of universal gravitation, forming the foundation of classical mechanics. The Principia is regarded as one of the most important works in the history of science.

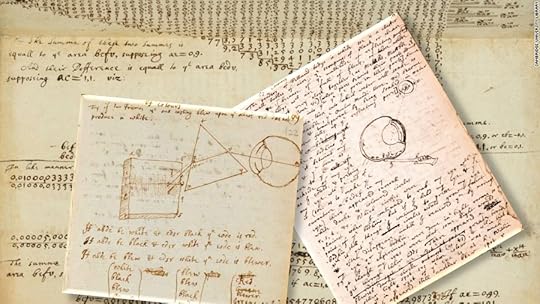

“Plato is my friend, Aristotle is my friend, but my greatest friend is truth.” – Isaac Newton (1642-1727). Cambridge University Library holds the largest and most important collection of the scientific works of Newton.

The founders of scientific method, in the 16th and 17th centuries felt that the universe is similar to a clock-like machine, independent of any law maker. The scientific community loved this idea, not because they truly believed in this assumption, but because only through such assumption, we were able to let go of ourselves of the iron fist of religion that was chocking the study of nature. And so it was reluctantly omitted from all scientific endeavors.

This approach worked. We discovered many mechanisms of nature, and invented many instruments that makes our lives comfortable. For over three centuries, scientists believed that the laws of nature are absolute, and by discovering them, we can understand nature and its functions.

After a while, scientists started to discover that these laws of nature weren’t as absolute as was originally theorized. They discovered that what we can perceive about the universe is grossly limited. The forces of the universe that is not yet reachable to human mind has come to be known as – the dark energy – the unknown force that is not reachable to the scientific study. Instead of calling it the “universal energy,” they called it “the dark energy.”

Many scientifically educated modern day gurus try to rationalize a synthesis of these two approaches – science of matter and the knowledge of spirit into one.

On the other hand, it feels that we may find a medium where we can reconcile the differences. We have surprised ourselves from time to time what the human mind is capable of. May be, we will at some point reconcile the differences between matter and spirit.

In all honesty, I feel that it is impractical to synthesize these two into a unified approach. This is because science, as a branch of studying nature was created to rid of the subjective theories and doctrines from the study of nature. Science and spirituality are two separate approaches to understand our nature and ourselves.

Carl Sagan (November 9, 1934 – December 20, 1996) relentlessly advocated skeptical inquiry and encouraged applying the scientific way of thinking to everyday life. He believed that scientific thinking refines our intellectual and moral integrity.

June 11, 2016

Mastering the Art of Learning

It was the fall of ’95 when I found myself surrounded by 136 other ambitious and nervous new medical students, bracing ourselves for orientation. While my peers and I shared a certain air of confidence, it was hard to miss the palpable anxiety (tinged with self-doubt) that filled the room.

The distinguished professor welcomed us by defining medical professionalism:

Commitment to patient-centered care, intellectual honesty, social responsibility, and advocacy,

she explained. However true the sentiment, we knew what was really expected of us is that we would amass knowledge with single-minded devotion. Over the years, we all shared one common and constant goal: be a sponge of seemingly infinite knowledge.

Twenty years later and the process of learning continues. As students (even as early as grade school), we’re governed by standardized testing and validated by our GPAs—all the while rarely, if ever, being tested on our understanding of what it takes to be an open-minded, lifelong learner. Decades of education taught me one thing above all others: the art of learning to learn.

In the era of No Child Left Behind and the questionable efficacy of cumbersome testing, we’re slowly coming to the heavy realization that perhaps we’ve not yet learned how to learn. Armed with the facts and figures, most of us are never taught how to successfully digest not only what we hear in the classroom, but also how to absorb the world around us as engaged learners.

Telecommunications pioneer Richard Hamming, author of The Art of Doing Science and Engineering: Learning to Learn, offers suggestions about how to succeed in the lost art of learning. Here are ten rules based off of his advice encouraging anyone to be their best self through the simple act of accumulating knowledge:

1. Concentrate on fundamental principles rather than facts.

Structure your learning so that you’re able to ride the information wave, not drown in it.

As time marches forward, the amount of knowledge in the world grows exponentially—doubling about every 20 years. But our brain can only process information at a rate of around 60 bits per second, and our minds aren’t getting faster even as the information load skyrockets. It’s easy to get lost in details, so focusing on fundamentals is key.

Set aside reading time—indulge in your own fields of interest as well as exploring new developments in areas outside of your immediate preoccupation.

2. Learn from those around you.

As people gravitate away from trade jobs, more individuals are graduating from college than ever before. The number of science doctorates earned each year alone grew by nearly 40% between 1998 and 2008. It’s important to balance competition with the company of people who can motivate and inspire us. Learn from the success of others. Hamming says it best,

Vicarious learning from the experiences of others saves making errors yourself.

Let the achievements of others provide you with a sort of roadmap. Young or old, there are always going to be people who are wiser and more accomplished than you—make these people your allies and learn everything you can from them.

3. Focus on the future. Learn from the past and move on. Live in the present.

The landscape of the world is fast changing, transformed by digital revolution and explosive growth of disruptive ideas in almost all human endeavors. While we can’t predict what will happen next, we can be ready to adapt to change. Learning from the past is important also, of course, to ensure yesterday’s mistakes aren’t repeated. In this race toward the future, we lose the present. As Seneca observed,

The greatest obstacle to living is expectancy, which hangs upon tomorrow and loses today… The whole future lies in uncertainty: live immediately.

4. Make it personal.

Always find how your learning impacts you personally. Whether you work a corporate job, run a small business, or maintain an academic career, don’t let your job or degrees box you in. Grow to be a well-rounded, best version of yourself. Structure your learning efforts according to some general direction in which you want to move. Having a vision is what separates leaders from followers. Goals evokes passion, which encourages you to want to learn, not feel like you simply have to.

5. Trial and error is key.

Finding what style of learning best suits you is a process filled with trial and error. How to learn can’t be discovered through words—we have to try different techniques to stumble upon what works best. Rely on your teachers but think for yourself too. Never be afraid to question and challenge the status quo.

6. Make the best of your working space.

The workplace continues to evolve rapidly—with trends like communal workspaces and working from home sweeping the nation. Surprisingly, people tend to do their best work when working conditions aren’t ideal. Don’t let your surroundings distract you from the task at hand. One tip to make the best of your office, if you have one, is to leave your door open often. It may seem counterintuitive, but while you may occasionally be more distracted, you’ll also be able to stay plugged in to what’s most important: ensuring that you’re working on the right matters.

7. Only you can put in the time it takes to learn.

To quote Hamming,

I am… only a coach. I cannot run the mile for you.

Even for those inherently talented, there is no substitute for effort. Don’t wait for or rely upon luck. Remember the old adage: Luck favors the prepared mind.

8. Work on what matters.

If you’re an aspiring entrepreneur, to do great work, you must ask yourself: What is the most important problem in the society that desperately needs resolution? That’s how you make a difference. This focus will motivate you while also ridding the distractions of trivial matters.

9. Strive for excellence.

Sometimes learning is hard—really hard. Don’t let that deter you from what you want to achieve. There is no greater pay-off than living the life you always imagined, and there is no greater joy than discovering things for yourself. Put in the time to learn and always focus on how you learn best.

1915,November 4. Einstein aged 36, having just completed the two-page masterpiece that would catapult him into international celebrity and historical glory, his theory of general relativity, Einstein sent 11-year-old Hans Albert: “These days I have completed one of the most beautiful works of my life, when you are bigger, I will tell you about it.”

Source – Posterity: Letters of Great Americans to Their Children

![René Descartes, Renatus des Cartes de Homine figuris (Lugduni Batuorum [Leyden]: Apud Franciscus Moyardum & Petrum Leffen, 1662). In this work Descartes posited that much human behavior can be explained by mechanical responses rather than the actions of the soul. Through a better knowledge of the mechanics of the body, he hoped to cure and prevent disease, and even to slow aging.](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1478502230i/21078555._SX540_.jpg)

![‘A Missing Boy', published on September 6, 1905 in s newspaper. It appeals for the public's help in tracing “a Brahmin boy of the Vaishnava (Thengalai) sect, named Ramanujam, of fair complexion and aged about 18 years” who had “left his [Kumbakonam] home on some misunderstanding.”](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1468824629i/19748366.png)