Rajeev Kurapati's Blog, page 4

November 7, 2017

Is Marriage Key to Happiness?

Can Couples Live Happily Without Marriage?

November 2, 2017

This is How (Scientifically Proven) Meditation Sharpens Your Memory

This is How Meditation Sharpens Your Memory

Memory is not just a property of the complex beings that are humans. The most fundamental unit of life – cells – has to remember things and events for two reasons: One, to avoid harmful predators or enemies and secondly, to seek favorable stimuli. Without this faculty of memory, all living beings are vulnerable to forces of nature. And in this world of modernization, our memory banks are flooded with so much useless information that our minds have less and less time to process what’s important.

We have invented gadgets to help remember things, people, and events. But technology has its limits. We’ve also developed mental technique to bolster our memory by training and challenging our mind to remember and retain mass amounts of information – cross word puzzles, Sudoku, breathing routines, regular exercises, and myriad of stress relieving techniques are abound.

A recent study by Michaela Dewar and her colleagues discovered a simple, yet powerful practice that helps memory last over a long term. Here is an excerpt from this article to be published in the journal Psychological Science, a publication of the Association for Psychological Science.

October 29, 2017

Where Does Creativity Come From?

October 26, 2017

Mahatma Gandhi and Leo Tolstoy Letters: How they disagreed without being disagreeable

May 14, 2017

What is Minimalism?

Minimalism is not fetishizing curated “simplicity” of clean loft spaces, of designer capsule wardrobes, or elaborately reduced diets.

It’s not a coincidence that most of the stuff we accumulate, the elaborate ward robes, the supplies for hobbies and the gratuitous display of power or status. Our urge to accumulate stuff is the result of centuries of social conditioning, mostly powered by consumer driven economy.

Minimalism is the refusal of this mindless consumption.

May 9, 2017

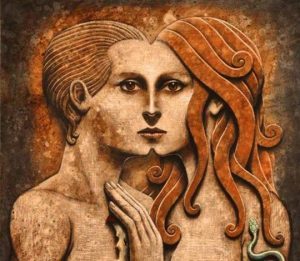

Do Soul Mates Really Exist?

Thomas Moore, in his book Soul Mates describes a soul mate as someone to whom we feel profoundly connected, as though the the communication and the communicating that takes places between us were not the product of intentional effort, but rather a divine grace. Richard Bach describes the relationship as, “our soulmate is one who makes life come to life,” and portrays the partner as “one who unveils the best part of the other.”

So ancient is the desire of one another which is implanted in us, people would spend their lives looking for their other half—their soul mate. For many, this search for their true love is the most important thing in their lives. This is exemplified throughout both ancient and modern literature.

The ancient Greeks used to host philosophical get-togethers attended by some of the most renowned thought-leaders in history. One of the most infamous discussions, The Symposium, was transcribed in great detail by the prolific philosopher Plato, who moderated the night’s discussion on the nature, purpose, and evolution of love. The attendees were each required to take the floor to describe their thoughts on the emotionally complex topic.

Plato’s Symposium, depiction by Anselm Feuerbach

The fourth speaker of the night, Aristophanes, was said to have painted quite a dramatic picture of the reason people so passionately seek a mate. His theory was that primitive humans were descendants from the moon and were androgynous—half male, half female. These sexually ambiguous beings set out to climb to the heavens to be one with the gods.

Aristophanes describes the fateful event:

Terrible was their might and strength, and the thoughts of their hearts were great, and they made an attack upon the gods; attempted to scale heaven, and would have laid hands upon the gods. Doubt reigned in the celestial councils. Should they kill them and annihilate the race with thunderbolts, as they had done the giants, then there would be an end of the sacrifices and worship which men offered to them; but, on the other hand, the gods could not suffer their insolence to be unrestrained. At last, after a good deal of reflection, Zeus discovered a way.

He said: ‘Methinks I have a plan which will enfeeble their strength and so extinguish their turbulence; men shall continue to exist, but I will cut them in two and then they will be diminished in strength and increased in numbers; this will have the advantage of making them more profitable to us. They shall walk upright on two legs, and if they continue insolent and will not be quiet, I will split them again and they shall hop about on a single leg.

As punishment, Zeus, the god of all gods, chopped each person in half, separating the bodies into two separate beings.

After the division the two parts of man, each desiring his other half, came together, and throwing their arms about one another, entwined in mutual embraces, longing to grow into one, they began to die from hunger and self-neglect, because they did not like to do anything apart; and when one of the halves died and the other survived, the survivor sought another mate, man or woman as we call them,–being the sections of entire men or women,–and clung to that.

Aristophanes concludes his thesis on why we love each other:

Aristophanes concludes his thesis on why we love each other:

Suppose Hephaestus (Greek God of welding and sculpturing), with his instruments, to come to the pair who are lying side by side and to say to them, ‘What do you mortals want of one another?’

They would be unable to explain. And suppose further, that when he saw their perplexity he said: ‘Do you desire to be wholly one; always day and night in one another’s company? for if this is what you desire, I am ready to melt and fuse you together, so that being two you shall become one, and while you live a common life as if you were a single man, and after your death in the world below still be one departed soul, instead of two–I ask whether this is what you lovingly desire and whether you are satisfied to attain this?’–

There is not a man of them who when he heard the proposal would deny or would not acknowledge that this meeting and melting into one another, this becoming one instead of two, was the very expression of his ancient need. And the reason is that human nature was originally one and we were a whole, and the desire and pursuit of the whole is called love.

While the tale may be a quixotic interpretation of mutual attraction, it shows that love, in all its glory and despair, has captured our imaginations and dominated our conversations since time immemorial.

For many people, love is the most important thing in their lives. This is exemplified throughout both ancient and modern literature. In his book, The Psychology of Love, American psychologist Robert Sternberg explains, “Without it, people feel as though their lives are incomplete.” Similarly, “Faith, hope, and love abide, these three; but the greatest of these is love,” says Saint Paul in a letter defining love to the Corinthians. He goes on to say, “Love bears all things, believes all things, hopes all things, endures all things.” Additionally, the poet Robert Frost expresses, “Love is an irresistible desire to be irresistibly desired.”

While spiritual gurus proclaim that love is the ultimate ground of all life, some philosophers and literary masters are unsympathetic in their expression of the sentiment: “Love is a serious mental disease,” says Plato. The author Oscar Wild calls love an “illusion.” John Dryden, an influential British poet, describes love as a “malady without a cure.”

What is this love that captivates the imaginations of so many—sages, prophets, philosophers, scientists, and you and me alike? Is love merely a physiological response that is born somewhere in our brains, or is it something more, something deeper and enduring?

To love and be loved is a fundamental and involuntary yearning. Our day-to-day connotation of love embodies a deeply passionate yet enigmatic feeling toward another person. Hippocrates proposed in 450 B.C. that emotions emanate from the brain and, since the dawn of scientific inquiry, researches have feverishly searched for the “seat” of love within the human brain. The science of biology describes love, matter-of-factly, as an emotion of evolutionary significance, a result of chemicals transmitting across neurons.

But despite our obsession with this lure—and the affection, passion, and rejection that often accompanies it—scholars and scientists struggle to this day to define what love is and who a soul mate is.

April 16, 2017

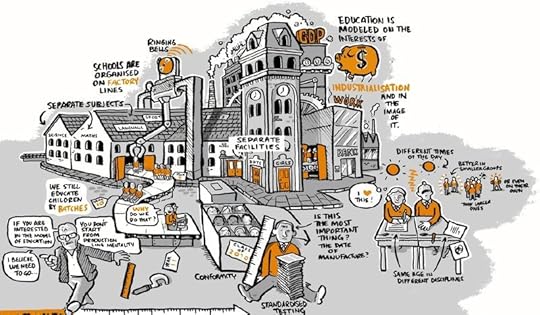

From Artists to Technicians: How We Slowly Lost the Art of the Job

“In the next economic downturn there will be an outbreak of bitterness and contempt for the super-corporate chieftains who pay themselves millions,” management visionary Peter Ducker predicted in 1997.

How did we arrive at the current state of the industrial economy we deal with now? Did we dehumanize the soul of craftsmanship in our efforts to dramatically improve productivity? Today’s industrial management is an enterprise that has no patience for the nuances of human craftsmanship in its urge to find ever greater manual efficiency and mass production. Most of the credit goes to Frederick Winslow Taylor (1856-1915) whose tombstone in Pennsylvania bears the inscription “The Father of Scientific Management.”

Taylor was probably the the first man in history who did not take work for granted but instead studied it. His approach to work still remains the basic foundation of the industrial economy.

In the early 1900s, the scientific method was applied to the concept of labor productivity. In The Principles of Scientific Management, Frederick Taylor described his scientific assessment of how the management of workers impacted productivity. The goal was to optimize tasks and specializations to create best practices.

Taylor observed in The Principles of Scientific Management:

Even in the case of the most elementary form of labor that is known, there is science, and that when the man best suited to this class of work has been carefully selected, when the science of doing the work has been developed, and when the carefully selected man has been trained to work in accordance with this science, the results obtained must of necessity be overwhelmingly greater than those which are otherwise possible.

Taylor conducted studies that utilized methods such as timing a worker’s sequence of motions with a stopwatch to scientifically prove the optimal way to complete a task. He determined that, for maximal productivity, the ideal weight a worker should lift in a shovel was 21 pounds. This knowledge enabled companies to then provide workers with shovels that were optimized for that 21-pound load. Formal performance measures were implemented. The result: companies saw a three-fold increase in productivity, and workers were rewarded with pay increases. It was a win-win for all involved, at least from a productivity standpoint.

The concept of productivity did not have much appeal prior to Taylor’s management methods. Skills were passed on to successive generations and learned by way of lengthy apprenticeships. Craftsmen made independent decisions about how their jobs were to be performed. Many carried out their tasks with immense passion and dedication, producing highly artistic work that was cherished for its craftsmanship. As a result, it would take a considerable amount of time to produce even articles of daily use, such as baskets, bricks, or vases.

The application of scientific methods meant that skilled crafts could be scaled down to simplified jobs performed by unskilled workers, the reason why the world may never again see the likings of another Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci, or Donatello—whose works were so profound that it almost feels like they left a piece of their souls in their creations. We convinced ourselves that the compromise was worth tolerating. The goal was to mass produce products or provide services to meet certain minimum market demands.

Taylor’s methods changed the outlook of the industrial era, as well as the sentiment of these skilled craftsmen. The method took away much of the autonomy craftsmen previously enjoyed in their work. With these newly implemented best practices, though, importance was given only to efficiency and productivity.

After years of various experiments to determine optimal work methods, Taylor proposed four principles of scientific management:

Replace rule-of-thumb work practices with a scientific method for every task.

Scientifically select, train, and teach each worker rather than passively leaving them to train themselves as best as they can.

Insure that all work being done is in accordance with scientifically developed methods.

Divide work nearly equally between workers assigned to the same task, and encourage management to establish many rules, laws, and formula to replace the personal preferences and judgments of the individual worker.

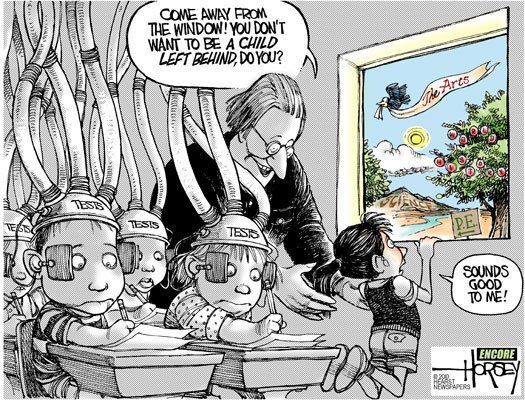

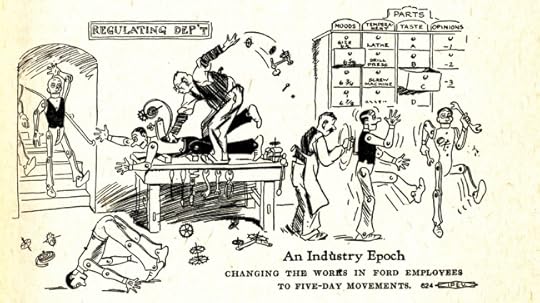

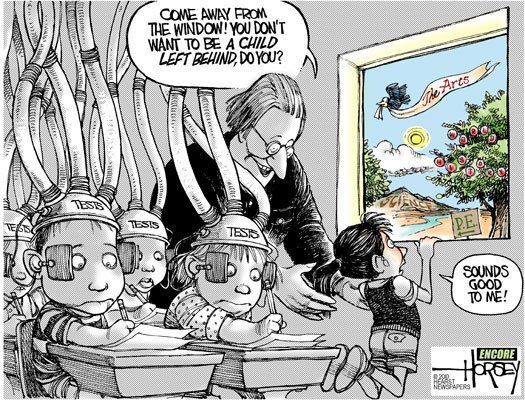

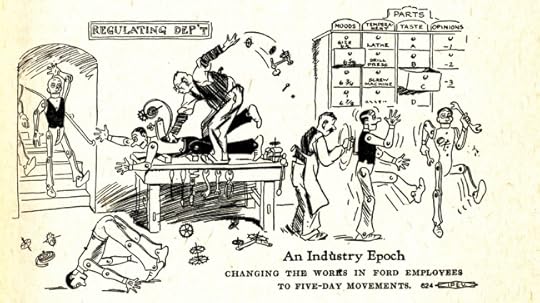

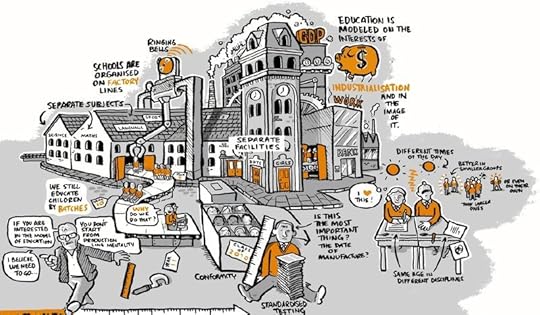

These principles were implemented in many work places, and the result was increased productivity. Henry Ford applied Taylor’s principles in his automobile factories. Even families began to perform their household tasks based on the results of these studies. The only downside was some initial resistance among workers, who complained that this method increased the monotony of their work. Ultimately, though, collective productivity took precedence over the subjective preferences of individuals. Scientific management changed the way we work, and decades later these principles were applied to hospitals and schools. Modified versions of these principles continue to be used today.

Taylor’s idea of “a fair day’s pay for a fair day’s work,” based on his belief that all workers were motivated by monetary reward, also took off. If a worker didn’t achieve his expected output in a given period, it was decided that he/she didn’t deserve to be paid as much as another worker who was more productive. The idea gained traction and was boldly implemented in doctors’ practices and hospitals. Since then, under industry rules, every doctor and hospital service within an individual medical facility is paid the same (more or less) amount for the same services and procedures they provide. The fees for an appendectomy, for instance, are the same whether the surgeon is fresh out of training or has 20 of experience. The more patients a doctor sees in a given day, the more productive he or she is, and thus the more lucrative his or her practice or the hospital’s bottom-line will be.

By grooming us to fit in with the rules and regulations of the industrial enterprise, we became a compliant cog in a giant machine. The idea behind this exercise was simple: people become easily replaceable if they are converted into predictable and subservient units. We can utilize person B if person A doesn’t show up to work today, for instance. This became the motto of industrial economy and has remained so ever since. Yes, all cogs contribute to the proper functioning of the society, but they are replaceable. So are you.

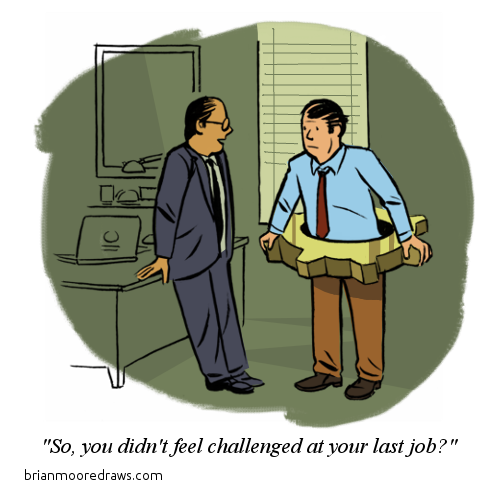

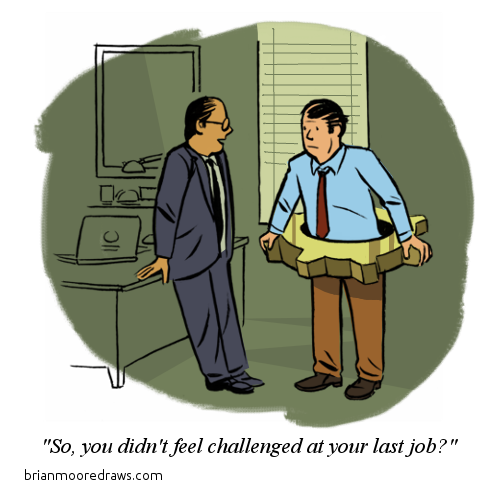

Don’t Feel Challenged in Your Job? Here is Why

“In the next economic downturn there will be an outbreak of bitterness and contempt for the super-corporate chieftains who pay themselves millions,” management visionary Peter Ducker predicted in 1997.

How did we arrive at the current state of industrial economy we deal with now? Did we dehumanize the soul of craftsmanship in our efforts to dramatic improvements in productivity? Today’s industrial management is an enterprise that has no room for the nuances of human craftsmanship in its urge to find ever greater manual efficiency and mass production. Most of the credit goes to Frederick Winslow Taylor (1856-1915) whose tombstone in Pennsylvania bears the inscription “The Father of Scientific Management”.

Taylor was probably the the first man in history who did not take work for granted, but looked at it and studied it. His approach to work still remains as the basic foundation of industrial economy.

In the early 1900s, the scientific method was applied to the concept of labor productivity. In The Principles of Scientific Management, Frederick Taylor described his scientific assessment of how the management of workers impacted productivity. The goal was to optimize tasks and specializations to create best practices.

Taylor observed in The Principles of Scientific Management:

Even in the case of the most elementary form of labor that is known, there is science, and that when the man best suited to this class of work has been carefully selected, when the science of doing the work has been developed, and when the carefully selected man has been trained to work in accordance with this science, the results obtained must of necessity be overwhelmingly greater than those which are otherwise possible.

Taylor conducted studies that utilized methods such as timing a worker’s sequence of motions with a stopwatch to scientifically prove the optimal way to complete a task. He determined that, for maximal productivity, the ideal weight a worker should lift in a shovel was 21 pounds. This knowledge enabled companies to then provide workers with shovels that were optimized for that 21-pound load. Formal performance measures were implemented. The result: companies saw a three-fold increase in productivity, and workers were rewarded with pay increases. It was a win-win for all involved, at least from a productivity standpoint.

The concept of productivity did not have much appeal prior to Taylor’s management methods. Skills were passed on to successive generations and learned by way of lengthy apprenticeships. Craftsmen made independent decisions about how their jobs were to be performed. Many carried out their tasks with immense passion and dedication, producing highly artistic work that was cherished for its craftsmanship. As a result, it would take a considerable amount of time to produce even articles of daily use, such as baskets, bricks, or vases.

The application of scientific methods meant that skilled crafts could be scaled down to simplified jobs performed by unskilled workers, the reason why the world may never again see the likings of another Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci, or Donatello—whose works were so profound that it almost feels like they left a piece of their souls in their creations. We convinced ourselves that the compromise was worth tolerating. The goal was to mass produce products or provide services to meet certain minimum market demands.

Taylor’s methods changed the outlook of the industrial era, as well as the sentiment of these skilled craftsmen. The method took away much of the autonomy craftsmen previously enjoyed in their work. With these newly implemented best practices, though, importance was given only to efficiency and productivity.

After years of various experiments to determine optimal work methods, Taylor proposed four principles of scientific management:

Replace rule-of-thumb work practices with a scientific method for every task.

Scientifically select, train, and teach each worker rather than passively leaving them to train themselves as best as they can.

Insure that all work being done is in accordance with scientifically developed methods.

Divide work nearly equally between workers assigned to the same task, and encourage management to establish many rules, laws, and formulae to replace the personal preferences and judgments of the individual worker.

These principles were implemented in many work places, and the result was increased productivity. Henry Ford applied Taylor’s principles in his automobile factories. Even families began to perform their household tasks based on the results of these studies. The only downside was some initial resistance among workers, who complained that this method increased the monotony of their work. Ultimately, though, collective productivity took precedence over the subjective preferences of individuals. Scientific management changed the way we work, and decades later these principles were applied to hospitals and schools. Modified versions of these principles continue to be used today.

Taylor’s idea of “a fair day’s pay for a fair day’s work,” based on his belief that all workers were motivated by monetary reward, took off. If a worker didn’t achieve his expected output in a given period, it was decided that he didn’t deserve to be paid as much as another worker who was more productive. The idea gained traction and was boldly implemented in doctors’ practices and hospitals. Since then, under industry rules, every doctor and hospital service within an individual medical facility is paid the same (more or less) amount for the same services and procedures they provide. The fees for an appendectomy, for instance, is same whether the surgeon is fresh out of training or has 20 of experience. The more patients a doctor sees in a given day, the more productive he or she is, and thus the more lucrative his or her practice or the hospital’s bottom-line will be.

By grooming us to fit in with the rules and regulations of the industrial enterprise, we became a compliant cog in a giant machine. The idea behind this exercise was simple: people become easily replaceable if they are converted into predictable and subservient units. We can utilize person B if person A doesn’t show up to work today, for instance. This became the motto of industrial economy ever since. Yes, all cogs contribute to the proper functioning of the society, but they are replaceable. So are you.