Richard Veryard's Blog, page 11

January 26, 2013

Information and Affirmation

@timrayner01 points out that so-called information-sharing is never neutral, disengaged - it is a positive act of communication.

Tim Rayner, The gift shift: what’s social about social media? (August 2012)

So even scorn is a form of affirmation. The comedian who devotes his spleen to the latest reality show is thereby contributing (in a complex post-modern fashion) to the show's success. Daniel Smith describes this as alternative consumption, and sees Charlie Brooker as a modern version of Baudelaire.

Daniel Smith, Spleen and Modernity: Baudelaire and ‘alternative’ consumption (July 2010)

The Royal Television Society may pretend that Charlie Brooker represents the high-brow alternative to Simon Cowell. But Brooker's material is basically the same as Cowell's, it just has a different sentiment. They obviously need each other.

Jonathan Harwood, Cowell and Morgan beaten by Brooker and Theroux (The Week March 2010)

"Don’t think of what you share as information. Even if what you share is information, by sharing it, you are telling the world that it is information that you affirm

in some way. It is the affirmation that counts. We share what we

love. Even when we share details about things we despise, they are

things we love to hate. Love is the key to understanding how we

contribute to social media commons. We populate the commons with

expressions of love."

Tim Rayner, The gift shift: what’s social about social media? (August 2012)

So even scorn is a form of affirmation. The comedian who devotes his spleen to the latest reality show is thereby contributing (in a complex post-modern fashion) to the show's success. Daniel Smith describes this as alternative consumption, and sees Charlie Brooker as a modern version of Baudelaire.

Daniel Smith, Spleen and Modernity: Baudelaire and ‘alternative’ consumption (July 2010)

The Royal Television Society may pretend that Charlie Brooker represents the high-brow alternative to Simon Cowell. But Brooker's material is basically the same as Cowell's, it just has a different sentiment. They obviously need each other.

Jonathan Harwood, Cowell and Morgan beaten by Brooker and Theroux (The Week March 2010)

Published on January 26, 2013 16:43

January 21, 2013

The Price of Fish

Michael Mainelli and Ian Harris have written a wide-ranging survey of economics, choice theory (game theory, psychology and ethics), systems theory, chaos theory, global warming and evolution. So what's all that got to do with the price of fish?

One of the themes running through the book is that the price of fish bears no relation to the value of fish, especially if we are concerned about long-term value and the sustainability of fish stocks.

Oscar Wilde famously defined a cynic as one who knows the price of everything and the value of nothing. This definition has also been applied to accountants and economists. Michael and Ian are leaders of the Long Finance initiative, a movement within the City of London that aims to overcome this kind of short-term financial cynicism.

Michael and Ian describe the price of fish as a wicked problem - a problem that lacks easy definition as well as easy answers. "Sustaining the supply of edible fish is a wicked problem that presents global risks." (p 301) And yet they suggest that the system might possibly sort itself out. "As fish run out and have to be sustainably fished, the historic underpricing of fish ceases." (293)

But this is no time for naive optimism, and the system will undoubtedly need some intervention. "When the price is the same as the value, there are opportunities for sustainable financing. So far, price has not equaled value for fish. This is the biggest, wicked decision-making problem of all: knowing how to set a price that equals the value." (p 295)

In other words, the problem is not just the alarming dwindling of fish stocks but the collective cynicism that not only led to this problem but also amplifies it and resists dealing with it effectively. The key word in the problem statement is the word "set" - even if a few clever people can say what they think the right price of fish should be, the real challenge is to set this price into global trading and consumption systems.

While the survey is light on the sociopolitical elements of the problem, the authors complain that governments have often made things worse, by inappropriate regulations and subsidies. Thus lazy or short-term thinking on the part of government is another manifestation of cynicism.

The Wikipedia article What's that got to do with the ...? derives the phrase from the alleged tendency of economists to connect everything with everything else. The authors go much further in this respect than most economists. But one trouble with systems thinking is this: once you start it's difficult to know where to stop. Although the authors have covered a great deal of material, it's not hard to think of other stuff they could have mentioned.

I don't think the authors are in any hurry to write a sequel, but if they did it might be about the Price of a Bee. While fish are undervalued, bees (apart from those involved in honey production) have no direct economic value at all; but when the bee population is threatened, global agriculture as a whole is in serious jeopardy. The indirect value of bees is vastly greater than the market for honey. Under the right conditions, with appropriate political and financial systems, people and communities may be able to make long-term ethical investments in sustainable fisheries, with a reasonable prospect of a long-term financial return: the Long Finance initiative is trying to stimulate the kind of system change that will create these conditions. But how on earth do we get communities to invest in the world bee population, without creating a market for bees? And would we really want that? Systems thinking tells us to be careful what we wish for. (Mary Catherine Bateson calls this The Revenge of the Good Fairy.)

Systems thinking also tells us that management (both public sector and private sector) has a tendency to over-intervene, to meddle and micromanage and ultimately make things worse. On the other hand, doing nothing doesn't feel like a good option either. (See Owen Barder on Good Global Citizenship, January 2013.) But there may be some kind of leverage or nudge that might just help a complex system to avoid catastrophe. It is always difficult to steer a path between naive optimism and pessimistic fatalism, but the battle against cynicism requires that we try.

Price of Fish website

Long Finance website

Wikipedia What's that got to do with the ...?

One of the themes running through the book is that the price of fish bears no relation to the value of fish, especially if we are concerned about long-term value and the sustainability of fish stocks.

Oscar Wilde famously defined a cynic as one who knows the price of everything and the value of nothing. This definition has also been applied to accountants and economists. Michael and Ian are leaders of the Long Finance initiative, a movement within the City of London that aims to overcome this kind of short-term financial cynicism.

Michael and Ian describe the price of fish as a wicked problem - a problem that lacks easy definition as well as easy answers. "Sustaining the supply of edible fish is a wicked problem that presents global risks." (p 301) And yet they suggest that the system might possibly sort itself out. "As fish run out and have to be sustainably fished, the historic underpricing of fish ceases." (293)

But this is no time for naive optimism, and the system will undoubtedly need some intervention. "When the price is the same as the value, there are opportunities for sustainable financing. So far, price has not equaled value for fish. This is the biggest, wicked decision-making problem of all: knowing how to set a price that equals the value." (p 295)

In other words, the problem is not just the alarming dwindling of fish stocks but the collective cynicism that not only led to this problem but also amplifies it and resists dealing with it effectively. The key word in the problem statement is the word "set" - even if a few clever people can say what they think the right price of fish should be, the real challenge is to set this price into global trading and consumption systems.

While the survey is light on the sociopolitical elements of the problem, the authors complain that governments have often made things worse, by inappropriate regulations and subsidies. Thus lazy or short-term thinking on the part of government is another manifestation of cynicism.

The Wikipedia article What's that got to do with the ...? derives the phrase from the alleged tendency of economists to connect everything with everything else. The authors go much further in this respect than most economists. But one trouble with systems thinking is this: once you start it's difficult to know where to stop. Although the authors have covered a great deal of material, it's not hard to think of other stuff they could have mentioned.

I don't think the authors are in any hurry to write a sequel, but if they did it might be about the Price of a Bee. While fish are undervalued, bees (apart from those involved in honey production) have no direct economic value at all; but when the bee population is threatened, global agriculture as a whole is in serious jeopardy. The indirect value of bees is vastly greater than the market for honey. Under the right conditions, with appropriate political and financial systems, people and communities may be able to make long-term ethical investments in sustainable fisheries, with a reasonable prospect of a long-term financial return: the Long Finance initiative is trying to stimulate the kind of system change that will create these conditions. But how on earth do we get communities to invest in the world bee population, without creating a market for bees? And would we really want that? Systems thinking tells us to be careful what we wish for. (Mary Catherine Bateson calls this The Revenge of the Good Fairy.)

Systems thinking also tells us that management (both public sector and private sector) has a tendency to over-intervene, to meddle and micromanage and ultimately make things worse. On the other hand, doing nothing doesn't feel like a good option either. (See Owen Barder on Good Global Citizenship, January 2013.) But there may be some kind of leverage or nudge that might just help a complex system to avoid catastrophe. It is always difficult to steer a path between naive optimism and pessimistic fatalism, but the battle against cynicism requires that we try.

Price of Fish website

Long Finance website

Wikipedia What's that got to do with the ...?

Published on January 21, 2013 03:19

January 18, 2013

Beyond Personal Knowledge Management

@hjarche via @Cybersal says "I'll show the same thing many times and people have various interpretations of it. Sharing knowledge artifacts is not transferring knowledge."

In other words, we don't actually share knowledge, what we share are documents and other artifacts that are supposed to contain knowledge.

If I send a document to Harold or Sally, they may or may not be able to extract some knowledge from it. There are many possible causes of knowledge impedance or attenuation, such as obscure language and specialized terminology, poor presentation, low motivation, and information overload. Even if either of them is able to glean some knowledge from perusing my document, what they get out may be quite different from the knowledge I thought I was putting in. Their interpretations depend on many things: their situation, their prior knowledge, beliefs and values, their expectations about what I'm trying to say, and their ability to read between the lines. (Even my closest friends and associates, who I imagine share a lot of my assumptions, read my documents in ways I find surprising, which is why I always greatly value their comments.)

Harold promotes something he calls Personal Knowledge Management, which describes knowledge management as an Input-Process-Output system.

Input (Seek) - we gather knowledge from our environment, including other people

Process (Sense) - we interpret, personalize and use knowledge

Output (Share) - we pass on our knowledge to other people

Harold talks about Network Learning, which seems to be about taking advantage of digital connectivity and embedding the Input (Seek) and Output (Share) into a wide social network. What I don't see in Harold's account of Network Learning is any sense of collective sense-making - knowledge emerging from the collaboration rather than being generated by one person. I'm also troubled by the implication that knowledge is produced by thinking rather than doing, since I think the most useful knowledge is what emerges from practice.

So while there is undoubtedly a great deal of value in Harold's approach, I think it underplays some of the social and practical elements of knowledge management and organizational intelligence.

Harold Jarche's website: Personal Knowledge Management, Network Learning

Places are still available on my forthcoming workshops Business Awareness (Jan 28), Business Architecture (Jan 29-31), Organizational Intelligence (Feb 1).

In other words, we don't actually share knowledge, what we share are documents and other artifacts that are supposed to contain knowledge.

If I send a document to Harold or Sally, they may or may not be able to extract some knowledge from it. There are many possible causes of knowledge impedance or attenuation, such as obscure language and specialized terminology, poor presentation, low motivation, and information overload. Even if either of them is able to glean some knowledge from perusing my document, what they get out may be quite different from the knowledge I thought I was putting in. Their interpretations depend on many things: their situation, their prior knowledge, beliefs and values, their expectations about what I'm trying to say, and their ability to read between the lines. (Even my closest friends and associates, who I imagine share a lot of my assumptions, read my documents in ways I find surprising, which is why I always greatly value their comments.)

Harold promotes something he calls Personal Knowledge Management, which describes knowledge management as an Input-Process-Output system.

Input (Seek) - we gather knowledge from our environment, including other people

Process (Sense) - we interpret, personalize and use knowledge

Output (Share) - we pass on our knowledge to other people

Harold talks about Network Learning, which seems to be about taking advantage of digital connectivity and embedding the Input (Seek) and Output (Share) into a wide social network. What I don't see in Harold's account of Network Learning is any sense of collective sense-making - knowledge emerging from the collaboration rather than being generated by one person. I'm also troubled by the implication that knowledge is produced by thinking rather than doing, since I think the most useful knowledge is what emerges from practice.

So while there is undoubtedly a great deal of value in Harold's approach, I think it underplays some of the social and practical elements of knowledge management and organizational intelligence.

Harold Jarche's website: Personal Knowledge Management, Network Learning

Places are still available on my forthcoming workshops Business Awareness (Jan 28), Business Architecture (Jan 29-31), Organizational Intelligence (Feb 1).

Published on January 18, 2013 02:42

January 15, 2013

On Readiness

In his presentation on Enterprise Agility at the SCiO meeting yesterday, Patrick Hoverstadt introduced the concept of Yarak.

In falconry, the word Yarak describes a trained hawk that is fit and in a proper condition for hunting. According to the Oxford Dictionary, the word entered the English language in the 19th century, perhaps from Persian yārakī 'strength, ability' or from Turkish yaraǧ 'readiness'.

Patrick explained that Yarak involves a balance between two forces - motivation and strength. The falcon has to be hungry enough to want to hunt, and strong enough to hunt effectively. So the falconer has to get the balance right: too little food and the creature cannot hunt, too much food and it can't be bothered.

When I talk to people about building organizational intelligence in their own organizations, I hear two forms of resistance. One is that the organization has so little inherent intelligence at present that the task is daunting; the other is that the bosses wouldn't want it.

When I take examples from glamorous high-tech companies like Microsoft and Google, this can provoke a somewhat fatalist reaction. People say: This kind of intelligence may be all very well for these hi-tech birds of prey, but ordinary companies like us simply don't have the resources or capability to do any of this stuff.

So it's important to see examples from ordinary companies as well as from the glamorous ones. Every company has some intelligence, although it may be patchy, fragmented and inconsistent. So we need to find ways of linking and leveraging this intelligence to create a positive spiral of improvement.

As for the question of motivation, there will still be many organizations where the senior management team, perhaps lacking confidence in its own intelligence, will lack enthusiasm for developing intelligence across the rest of the organization. This may be a generation thing - the younger generation of management may be much more comfortable with new styles of management (such as "Theory Y") as well as with social networking and other technologies.

Does this mean we have to wait for a generation, until the current bosses have shuffled off to the golf course or the Caribbean cruise? Not if the organization can start to develop intelligence in a bottom-up piecemeal fashion. In which case, what matters is the motivation and strength of the people and groups across the organization, and not just the motivation and strength of the bosses. Can we achieve some useful results without top-down support?

In falconry, the word Yarak describes a trained hawk that is fit and in a proper condition for hunting. According to the Oxford Dictionary, the word entered the English language in the 19th century, perhaps from Persian yārakī 'strength, ability' or from Turkish yaraǧ 'readiness'.

Patrick explained that Yarak involves a balance between two forces - motivation and strength. The falcon has to be hungry enough to want to hunt, and strong enough to hunt effectively. So the falconer has to get the balance right: too little food and the creature cannot hunt, too much food and it can't be bothered.

When I talk to people about building organizational intelligence in their own organizations, I hear two forms of resistance. One is that the organization has so little inherent intelligence at present that the task is daunting; the other is that the bosses wouldn't want it.

When I take examples from glamorous high-tech companies like Microsoft and Google, this can provoke a somewhat fatalist reaction. People say: This kind of intelligence may be all very well for these hi-tech birds of prey, but ordinary companies like us simply don't have the resources or capability to do any of this stuff.

So it's important to see examples from ordinary companies as well as from the glamorous ones. Every company has some intelligence, although it may be patchy, fragmented and inconsistent. So we need to find ways of linking and leveraging this intelligence to create a positive spiral of improvement.

As for the question of motivation, there will still be many organizations where the senior management team, perhaps lacking confidence in its own intelligence, will lack enthusiasm for developing intelligence across the rest of the organization. This may be a generation thing - the younger generation of management may be much more comfortable with new styles of management (such as "Theory Y") as well as with social networking and other technologies.

Does this mean we have to wait for a generation, until the current bosses have shuffled off to the golf course or the Caribbean cruise? Not if the organization can start to develop intelligence in a bottom-up piecemeal fashion. In which case, what matters is the motivation and strength of the people and groups across the organization, and not just the motivation and strength of the bosses. Can we achieve some useful results without top-down support?

Published on January 15, 2013 01:25

January 13, 2013

How to make change happen in government

Steve Hilton, David Cameron's one-time policy adviser currently on mid-term sabbatical in California, has given Stanford students some frank insights into the workings of Government.

The Prime Minister sometimes opposes the measures his own

ministers put forward. He often finds out about these policies from the radio or newspapers.

Only 30 per cent of what the government is doing is actually delivering what

we are supposed to be doing.

It’s a brilliant system for paper-shuffling people to be in control. The bureaucracy masters the politicians.

I just wanted to make a few comments about collective intelligence and the role of the policy adviser.

Some Prime Ministers and Presidents have had an extraordinary ability to get through large quantities of paperwork and master the critical points. Cameron has many strengths as a leader, but this doesn't seem to be one of them. As a consequence of this, he is effectively leaving journalists to perform a filtering function - thus he pays attention to an issue only when it is drawn to his attention by the media, and of course, this delayed attention may cause some irritation or embarrassment sometimes. Perhaps a more diligent policy adviser should have picked up some of these issues earlier?

In the system we may infer from Hilton's description, journalists are not only performing a filtering function but also a sensemaking function. There is clearly a difference between the way a

policy looks in some bundle of government papers and how it looks when

it appears in the media. Again, we might have expected a diligent policy adviser to have anticipated how policies would appear to the public.

But it seems that the politicians and their advisers don't control the volume of paperwork they are given to wade through. Fans of the "Yes Minister" series will find it easy to imagine civil servants calculating the amount of paperwork that an individual can cope with, and making sure that key items of information are well-buried in trivia. (For example, if a given politician or adviser can just about manage three boxes of papers per night, then the most important item will be hidden somewhere in the fourth box.) In his seminar, Hilton dramatically produced a pile of paper one foot high (representing four days committee output), prompting gasps from students.

"The idea that a couple of political advisers read through all this and spot things that are bad, things that are contradictory, is just inconceivable", pleads Hilton.

When Hilton talks about "delivering what

we are supposed to be doing", this presumably refers to some kind of top-down strategic plan, formulated before the election and presented in the manifesto. But this raises some important questions about the relationship between strategy and execution, and the possibility for strategies to emerge and evolve during execution.

Which in turn raises some questions about government as a learning system. Recent governments (including Blair's New Labour) have had a focus on delivery, which emphasizes single-loop learning - getting better at achieving a fixed set of goals. However, this has to be balanced against double-loop learning - changing the goals to fit changing circumstances.

In an earlier analysis of New Labour and Delivery, two MORI analysts argued that delivery and achievement was at least partially subjective and rhetorical.

"Delivery" is not keeping your promises, it is convincing the public that you have kept your promises.

What matters is not what you promise, but what the public understands by those promises, and what expectations they arouse.

Hilton clearly agrees about the importance of communication. He encourages his students to think about how policies can be "branded", and suggests that policies often fail not because they weren't very good policies in the first place but because they are poorly presented. That might be true, but it is also a common excuse: politicians genererally find it easier to admit to errors in presentation than to errors in policy.

Which part of this ecosytem has the longest memory? Presumably the civil servants. And which part has the shortest memory? With some honourable exceptions, probably the media. According to one theory of change, when there are several subsystems operating on different timescales, it is the slowest system that controls the whole. And the Purpose Of the System Is What It Does.

Roger Mortimore and Mark Gill, New Labour and Delivery (IPSOS MORI May 2004)

PM’s aide exposes No 10’s lack of control (Sunday Times, 13 January 2013) (subscription)

John Harlow and Eric Kiefer, Shoes off, feet up, the dude lifts lid on No 10 (Sunday Times, 13 January 2013)

Patrick Hennessy, David Cameron finds out about policies from the newspapers, reveals Steve Hilton (The Telegraph 13 January 2013)

James Tapsfield, Prime Minister often finds out about policies from the radio or newspapers, says former advisor Hilton (The Independent 13 January 2013)

Richard Veryard (ed), Fragile Strategy or Fragile Execution (Storify, December 2012)

The Prime Minister sometimes opposes the measures his own

ministers put forward. He often finds out about these policies from the radio or newspapers.

Only 30 per cent of what the government is doing is actually delivering what

we are supposed to be doing.

It’s a brilliant system for paper-shuffling people to be in control. The bureaucracy masters the politicians.

I just wanted to make a few comments about collective intelligence and the role of the policy adviser.

Some Prime Ministers and Presidents have had an extraordinary ability to get through large quantities of paperwork and master the critical points. Cameron has many strengths as a leader, but this doesn't seem to be one of them. As a consequence of this, he is effectively leaving journalists to perform a filtering function - thus he pays attention to an issue only when it is drawn to his attention by the media, and of course, this delayed attention may cause some irritation or embarrassment sometimes. Perhaps a more diligent policy adviser should have picked up some of these issues earlier?

In the system we may infer from Hilton's description, journalists are not only performing a filtering function but also a sensemaking function. There is clearly a difference between the way a

policy looks in some bundle of government papers and how it looks when

it appears in the media. Again, we might have expected a diligent policy adviser to have anticipated how policies would appear to the public.

But it seems that the politicians and their advisers don't control the volume of paperwork they are given to wade through. Fans of the "Yes Minister" series will find it easy to imagine civil servants calculating the amount of paperwork that an individual can cope with, and making sure that key items of information are well-buried in trivia. (For example, if a given politician or adviser can just about manage three boxes of papers per night, then the most important item will be hidden somewhere in the fourth box.) In his seminar, Hilton dramatically produced a pile of paper one foot high (representing four days committee output), prompting gasps from students.

"The idea that a couple of political advisers read through all this and spot things that are bad, things that are contradictory, is just inconceivable", pleads Hilton.

When Hilton talks about "delivering what

we are supposed to be doing", this presumably refers to some kind of top-down strategic plan, formulated before the election and presented in the manifesto. But this raises some important questions about the relationship between strategy and execution, and the possibility for strategies to emerge and evolve during execution.

Which in turn raises some questions about government as a learning system. Recent governments (including Blair's New Labour) have had a focus on delivery, which emphasizes single-loop learning - getting better at achieving a fixed set of goals. However, this has to be balanced against double-loop learning - changing the goals to fit changing circumstances.

In an earlier analysis of New Labour and Delivery, two MORI analysts argued that delivery and achievement was at least partially subjective and rhetorical.

"Delivery" is not keeping your promises, it is convincing the public that you have kept your promises.

What matters is not what you promise, but what the public understands by those promises, and what expectations they arouse.

Hilton clearly agrees about the importance of communication. He encourages his students to think about how policies can be "branded", and suggests that policies often fail not because they weren't very good policies in the first place but because they are poorly presented. That might be true, but it is also a common excuse: politicians genererally find it easier to admit to errors in presentation than to errors in policy.

Which part of this ecosytem has the longest memory? Presumably the civil servants. And which part has the shortest memory? With some honourable exceptions, probably the media. According to one theory of change, when there are several subsystems operating on different timescales, it is the slowest system that controls the whole. And the Purpose Of the System Is What It Does.

Roger Mortimore and Mark Gill, New Labour and Delivery (IPSOS MORI May 2004)

PM’s aide exposes No 10’s lack of control (Sunday Times, 13 January 2013) (subscription)

John Harlow and Eric Kiefer, Shoes off, feet up, the dude lifts lid on No 10 (Sunday Times, 13 January 2013)

Patrick Hennessy, David Cameron finds out about policies from the newspapers, reveals Steve Hilton (The Telegraph 13 January 2013)

James Tapsfield, Prime Minister often finds out about policies from the radio or newspapers, says former advisor Hilton (The Independent 13 January 2013)

Richard Veryard (ed), Fragile Strategy or Fragile Execution (Storify, December 2012)

Published on January 13, 2013 09:12

December 28, 2012

Organizational Intelligence Forum - Spring 2013

In association with Unicom, I am trying to put together an Organizational

Intelligence Forum, possibly on April 25th to coincide with the Performance Management Forum.

Unicom is also planning another Enterprise Architecture Forum in London on

March 21st. These generally attract a good audience of senior IT

management from blue chip organizations. At the previous Forum in

September, we had case studies from finance, oil and higher education.

Anyone wishing to present a case study at the next event, please contact

me or Unicom.

Those outside the UK may wish to plan a trip to London to coincide with these events.

These

events are part-funded by commercial sponsorship and vendor

exhibitions. Please contact me or Unicom for a vendor information pack.

Intelligence Forum, possibly on April 25th to coincide with the Performance Management Forum.

Unicom is also planning another Enterprise Architecture Forum in London on

March 21st. These generally attract a good audience of senior IT

management from blue chip organizations. At the previous Forum in

September, we had case studies from finance, oil and higher education.

Anyone wishing to present a case study at the next event, please contact

me or Unicom.

Those outside the UK may wish to plan a trip to London to coincide with these events.

These

events are part-funded by commercial sponsorship and vendor

exhibitions. Please contact me or Unicom for a vendor information pack.

Published on December 28, 2012 07:01

December 1, 2012

Challenge-Led Innovation

#oipsrv One view of innovation is that it is motivated by a series of

challenges. Once upon a time, we would have used the word

"problems", and called this the "problem-solving" approach to

innovation. But the word "problem" is now taboo in business world,

and we have to find various euphemisms such as "opportunity" or

"challenge". Necessity is the mother of invention.

At a seminar at the British Library yesterday (Open

Innovation in Public Services), I heard several ways of

managing innovation in these terms.

Challenge Prizes - Offering cash prizes to the first

person or team that can solve a well-defined problem. This

approach has been used for centuries, although the history of

technology is littered with unfortunate inventors who have

produced something brilliant only to have the prize taken by a

rival, or unfairly denied for various spurious reasons.

Furthermore, a poorly designed prize can discourage

collaboration and thus inhibit innovation instead of encouraging

it. However, as Vicki Purewal explained, prize schemes do not have to follow the

winner-takes-all, loser-gets-nothing rule, and are often

designed to distribute the rewards more fairly and in stages. See Centre for Challenge Prizes

Hack Days - Bringing volunteers together for a day to build

quick and dirty solutions to a broad range of problems. This

approach is most commonly seen in the software arena, and the

example presented was NHS Hackdays.

Challenge Platform - Creating a social network and/or funding for

collective problem-solving. Contrasting examples from Barking and Dagenham, Camden, and York.

I think these are all good and useful initiatives. One of the

benefits is that they open up the organization or ecosystem to ideas

from a much larger community of people. This can be both more

democratic and a lot more cost-effective than hiring one of the

large consultancies, which seems to be the default method in some

organizations. One way of putting this is that it changes the available scope of Organizational Intelligence.

However, problem-solving may be necessary for innovation, but is not

sufficient. These initiatives concentrate on invention, which tends

to be the sexy part of innovation. @davidtownson from the Design

Council showed two slides that placed invention into a broader

context. The first of these slides showed the Design Council's design process, drawn as a Double Diamond. The first diamond is devoted to clarifying the problem or requirement, and the second diamond is devoted to solving a well-defined problem. If the challenge-led approach starts from a well-defined problem, then it is just doing the second diamond.

Source: Design Council

The second of David's slides showed a spiral model of innovation, culminating in Systemic Change. (I can't find a version of this spiral on the Design Council website.) This might suggest extending the Double Diamond into a Triple Diamond, where the third diamond tackled the difficult and unglamorous end of the innovation process - rolling out the solution, integrating it with systems and working practices, and embedding it into the target organization or ecosystem.

This triple diamond faintly echoes the three-phase innovation model proposed (in a somewhat different context) by Abernathy and Utterback, which combined product innovation, process innovation, competitive

environment and organizational structure:

Fluid phase (exploratory)

Transitional phase (convergence on solution)

Specific phase (focus on costs and performance)

Within the public sector, there may be broad demand for innovations (individual challenges), but there is also extremely strong demand for innovation as such (focus on costs and performance). So a suitably modified version of the Abernathy and Utterback model would be extremely relevant to the public sector.

Let us return to the question of Open Innovation. In her presentation, Heather Niven contrasted a large tanker with a flotilla of small boats. In the specific area of NHS information systems, Heather's metaphor applies very well to the contrast between the NPfIT - a grossly expensive centralized white elephant - and a large number of small but useful apps developed in the NHS Hackdays Carl Reynolds has organized. The "bottom-up" approach may be more promising than the "top-down" approach, as well as more exciting, but there probably needs to be a stronger element of coordination and integration before we can see this innovation as anything more than a load of well-meaning but marginal efforts by a bunch of extremely clever geeks.

Finally, there was some discussion about the word "innovation", and resistance to this concept within the public sector in particular. Perhaps we need to go back to talking about problem-solving?

Abernathy, W.J. and Utterback, J.M. Patterns of Innovation in Technology (Technology Review 1978) via Innovation Zen

For @LucyInnovation 's report of the British Library seminar, see Because not all the smart people work for you ...

challenges. Once upon a time, we would have used the word

"problems", and called this the "problem-solving" approach to

innovation. But the word "problem" is now taboo in business world,

and we have to find various euphemisms such as "opportunity" or

"challenge". Necessity is the mother of invention.

At a seminar at the British Library yesterday (Open

Innovation in Public Services), I heard several ways of

managing innovation in these terms.

Challenge Prizes - Offering cash prizes to the first

person or team that can solve a well-defined problem. This

approach has been used for centuries, although the history of

technology is littered with unfortunate inventors who have

produced something brilliant only to have the prize taken by a

rival, or unfairly denied for various spurious reasons.

Furthermore, a poorly designed prize can discourage

collaboration and thus inhibit innovation instead of encouraging

it. However, as Vicki Purewal explained, prize schemes do not have to follow the

winner-takes-all, loser-gets-nothing rule, and are often

designed to distribute the rewards more fairly and in stages. See Centre for Challenge Prizes

Hack Days - Bringing volunteers together for a day to build

quick and dirty solutions to a broad range of problems. This

approach is most commonly seen in the software arena, and the

example presented was NHS Hackdays.

Challenge Platform - Creating a social network and/or funding for

collective problem-solving. Contrasting examples from Barking and Dagenham, Camden, and York.

I think these are all good and useful initiatives. One of the

benefits is that they open up the organization or ecosystem to ideas

from a much larger community of people. This can be both more

democratic and a lot more cost-effective than hiring one of the

large consultancies, which seems to be the default method in some

organizations. One way of putting this is that it changes the available scope of Organizational Intelligence.

However, problem-solving may be necessary for innovation, but is not

sufficient. These initiatives concentrate on invention, which tends

to be the sexy part of innovation. @davidtownson from the Design

Council showed two slides that placed invention into a broader

context. The first of these slides showed the Design Council's design process, drawn as a Double Diamond. The first diamond is devoted to clarifying the problem or requirement, and the second diamond is devoted to solving a well-defined problem. If the challenge-led approach starts from a well-defined problem, then it is just doing the second diamond.

Source: Design Council

The second of David's slides showed a spiral model of innovation, culminating in Systemic Change. (I can't find a version of this spiral on the Design Council website.) This might suggest extending the Double Diamond into a Triple Diamond, where the third diamond tackled the difficult and unglamorous end of the innovation process - rolling out the solution, integrating it with systems and working practices, and embedding it into the target organization or ecosystem.

This triple diamond faintly echoes the three-phase innovation model proposed (in a somewhat different context) by Abernathy and Utterback, which combined product innovation, process innovation, competitive

environment and organizational structure:

Fluid phase (exploratory)

Transitional phase (convergence on solution)

Specific phase (focus on costs and performance)

Within the public sector, there may be broad demand for innovations (individual challenges), but there is also extremely strong demand for innovation as such (focus on costs and performance). So a suitably modified version of the Abernathy and Utterback model would be extremely relevant to the public sector.

Let us return to the question of Open Innovation. In her presentation, Heather Niven contrasted a large tanker with a flotilla of small boats. In the specific area of NHS information systems, Heather's metaphor applies very well to the contrast between the NPfIT - a grossly expensive centralized white elephant - and a large number of small but useful apps developed in the NHS Hackdays Carl Reynolds has organized. The "bottom-up" approach may be more promising than the "top-down" approach, as well as more exciting, but there probably needs to be a stronger element of coordination and integration before we can see this innovation as anything more than a load of well-meaning but marginal efforts by a bunch of extremely clever geeks.

Finally, there was some discussion about the word "innovation", and resistance to this concept within the public sector in particular. Perhaps we need to go back to talking about problem-solving?

Abernathy, W.J. and Utterback, J.M. Patterns of Innovation in Technology (Technology Review 1978) via Innovation Zen

For @LucyInnovation 's report of the British Library seminar, see Because not all the smart people work for you ...

Published on December 01, 2012 08:16

November 14, 2012

Conflicting Narratives

@queenchristina_ writes an excellent article on Google, Starbucks, and Amazon, arguing that "for these multinationals immorality is now standard practice" (Independent 13 November 2012). See also Martin Hickman, Good Bean Counters (Independent 16 October 2012).

It is much too easy for British politicians, journalists and taxpayers to get a sense of moral outrage when they discover how little UK tax these American companies pay on their UK earnings. There may be nothing illegal about the fact that the coffee beans are purchased from a Starbucks subsidiary in Switzerland, or that the UK subsidiary pays a royalty for the use of the Starbucks brand to another Starbucks subsidiary in the Netherlands. By a strange coincidence, the Netherlands charges a very low tax rate on royalty payments. Of course there are many British companies that use similar devices to reduce their UK tax bill.

The word "account" essentially means "story". The Starbucks accountants have constructed a story in which Switzerland and the Netherlands are essential links in the Starbucks value chain. British politicians have constructed a different story in which Starbucks is ripping off its British hosts. The moral outrage comes from the clash between these two narratives.

When two narratives clash, it seems natural for us to want to impose our preferred narrative on the Other. Wouldn't it be grand if Starbucks saw the error of its ways and started to pay a fair rate of UK tax. Or wouldn't it be equally grand if the UK tax laws were changed to regulate against these tax avoidance schemes? Or from Starbuck's point of view, wouldn't it be grand if UK corporate tax rates were reduced, so it could simplify its value chain at no cost to its shareholders? (Obviously words like "grand" and "fair" depend on the narrative.)

Of course, what is more likely is that the politicians will issue some threat of tighter regulation, the companies will make some temporary gesture to alleviate public hostility, and that the media will move onto the next target. In the meantime, politicians and the media can make things uncomfortable for corporate executives in the public eye.

And here's a slightly older example - the attempts by the US Government to hold BP to account for the oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico. One BP executive complained that "The

administration keeps pushing the boundaries on what we are responsible

for." (Wall Street Journal 1 June 2010 via NakedCapitalism)

In any case, there are always going to be conflicting narratives. I was at a workshop in the City this morning discussing how externalities might affect the future of money and the future of commerce. We discussed a range of topics, from mega-cities to carbon trading.

But what exactly are these externalities? Almost anything that one person thinks to be part of The System and another person thinks to be outside The System. As William P. Fisher, Jr

points out, "If we have to articulate and communicate a message that people then have

to act on, we remain a part of the problem and not part of the

solution." (Reimagining Capitalism Again, Sept 2011).

Oliver Greenfield identifies the following challenge:

Thus we have conflicting narratives, which result from disagreement about system boundaries (including time horizon as a type of boundary). A true systems approach might give us a systematic way of playing contested narratives off against each other.

See also

William P. Fisher, Jr, Question Authority (Oct 2011)

José M. Ramos, Temporalities of the Commons: Toward Narrative Coherence and Strategic Vision (Nov 2012)

Linked-In discussion on Good Bean Counters

and my post on Regulation and Complexity (Oct 2012)

It is much too easy for British politicians, journalists and taxpayers to get a sense of moral outrage when they discover how little UK tax these American companies pay on their UK earnings. There may be nothing illegal about the fact that the coffee beans are purchased from a Starbucks subsidiary in Switzerland, or that the UK subsidiary pays a royalty for the use of the Starbucks brand to another Starbucks subsidiary in the Netherlands. By a strange coincidence, the Netherlands charges a very low tax rate on royalty payments. Of course there are many British companies that use similar devices to reduce their UK tax bill.

The word "account" essentially means "story". The Starbucks accountants have constructed a story in which Switzerland and the Netherlands are essential links in the Starbucks value chain. British politicians have constructed a different story in which Starbucks is ripping off its British hosts. The moral outrage comes from the clash between these two narratives.

When two narratives clash, it seems natural for us to want to impose our preferred narrative on the Other. Wouldn't it be grand if Starbucks saw the error of its ways and started to pay a fair rate of UK tax. Or wouldn't it be equally grand if the UK tax laws were changed to regulate against these tax avoidance schemes? Or from Starbuck's point of view, wouldn't it be grand if UK corporate tax rates were reduced, so it could simplify its value chain at no cost to its shareholders? (Obviously words like "grand" and "fair" depend on the narrative.)

Of course, what is more likely is that the politicians will issue some threat of tighter regulation, the companies will make some temporary gesture to alleviate public hostility, and that the media will move onto the next target. In the meantime, politicians and the media can make things uncomfortable for corporate executives in the public eye.

And here's a slightly older example - the attempts by the US Government to hold BP to account for the oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico. One BP executive complained that "The

administration keeps pushing the boundaries on what we are responsible

for." (Wall Street Journal 1 June 2010 via NakedCapitalism)

In any case, there are always going to be conflicting narratives. I was at a workshop in the City this morning discussing how externalities might affect the future of money and the future of commerce. We discussed a range of topics, from mega-cities to carbon trading.

But what exactly are these externalities? Almost anything that one person thinks to be part of The System and another person thinks to be outside The System. As William P. Fisher, Jr

points out, "If we have to articulate and communicate a message that people then have

to act on, we remain a part of the problem and not part of the

solution." (Reimagining Capitalism Again, Sept 2011).

Oliver Greenfield identifies the following challenge:

"The externalities created by companies - or, for that matter, nation

states - in their pursuit of self-interest can seem rational at the

local, country and even regional level. But at a global level, in a

closed system, externalities are costs. What is rational at a company or

nation state level is irrational at a global level." (Green Economy Coalition, April 2012)

Thus we have conflicting narratives, which result from disagreement about system boundaries (including time horizon as a type of boundary). A true systems approach might give us a systematic way of playing contested narratives off against each other.

See also

William P. Fisher, Jr, Question Authority (Oct 2011)

José M. Ramos, Temporalities of the Commons: Toward Narrative Coherence and Strategic Vision (Nov 2012)

Linked-In discussion on Good Bean Counters

and my post on Regulation and Complexity (Oct 2012)

Published on November 14, 2012 14:09

November 12, 2012

Seeing is not observing

@anniemurphypaul advises us how to increase our powers of observation - by emulating scientists. "As practiced by scientists", she writes, "observation is a rigorous activity that integrates what the scientists are seeing with what they already know and what they think might be true."

Here are some tips that she draws from an article by Eberbach and Crowley.

Train your attention. Practise focusing on relevant features.

Keep field notes - careful records of your observations, quantifying them whenever possible. Try attaching a number to each episode you observe: how many times a customer picks up an item before deciding to buy it, how many minutes employees spend talking about office politics before getting down to business.

Develop hypotheses that you can test. What happens if a salesperson invites a potential customer to try out a product for herself? How does the tone of the weekly meeting change when it’s held in a different room?

Extended reflection. Actively engage with your observations after the event, organizing and analyzing what you've seen

Cycle. Engage in the cycle of observing, recording, testing, and analyzing many times over.

It may be useful here to distinguish between Field Notes and a Field Journal. Field Notes contain a record of what has been seen or heard by the observer. Whereas the Field Journal contains a record of ideas, thoughts, interpretations and other material. In particular, the Field Journal records anything else that was going on at the time, which later reflection may determine to have influenced the observations.

Sheldon Greaves outlines the approach adopted by Joseph Grinnell, who kept detailed records of his observations from 1894 to 1939, and who was Director of the Museum of Vertebrate Zoology at Berkeley for most of that time.

But in her review of Molly Gloss's short story The Grinnell method (Sept 2012), Maureen Kincaid Speller offers a detailed critique of the Grinnell method for observing human affairs, and complains that "there seems to be no place in Grinnell’s method for analysis, just the ongoing

accumulation of information".

Which is clearly why we also need extended reflection.

Annie Murphy Paul, How To Increase Your Powers of Observation (Time Ideas, May 2012)

Catherine Eberbach, Kevin Crowley From Everyday to Scientific Observation: How Children Learn to Observe the Biologist’s World (abstract) Review of Educational Research March 2009 vol. 79 no. 1 39-68 doi: 10.3102/0034654308325899

Cathryn Carson, Writing, Writing, Writing: The Natural History Field Journal as a Literary Text (Feb 2007)

Jamie Cromertie, How to keep your field notes and journal,

Sheldon Greaves, Making, Maintaining, and Using Serious Field Notes (Feb 2012)

Paul Handford, Notes on Keeping a Field Journal,

Betsy Mason, Beautiful Data: The Art of Science Field Notes (Wired Science, July 2011)

Places are still available on my Organizational Intelligence workshop, November 22nd.

Here are some tips that she draws from an article by Eberbach and Crowley.

Train your attention. Practise focusing on relevant features.

Keep field notes - careful records of your observations, quantifying them whenever possible. Try attaching a number to each episode you observe: how many times a customer picks up an item before deciding to buy it, how many minutes employees spend talking about office politics before getting down to business.

Develop hypotheses that you can test. What happens if a salesperson invites a potential customer to try out a product for herself? How does the tone of the weekly meeting change when it’s held in a different room?

Extended reflection. Actively engage with your observations after the event, organizing and analyzing what you've seen

Cycle. Engage in the cycle of observing, recording, testing, and analyzing many times over.

It may be useful here to distinguish between Field Notes and a Field Journal. Field Notes contain a record of what has been seen or heard by the observer. Whereas the Field Journal contains a record of ideas, thoughts, interpretations and other material. In particular, the Field Journal records anything else that was going on at the time, which later reflection may determine to have influenced the observations.

Sheldon Greaves outlines the approach adopted by Joseph Grinnell, who kept detailed records of his observations from 1894 to 1939, and who was Director of the Museum of Vertebrate Zoology at Berkeley for most of that time.

"The idea behind the Grinnell system is to turn you from a passive

recorder of information into a participant in a dialogue with nature.

Rather than just recording bits of data, you poke, explore and

cross-examine nature in order to sluice nuggets of knowledge from what

you see."

But in her review of Molly Gloss's short story The Grinnell method (Sept 2012), Maureen Kincaid Speller offers a detailed critique of the Grinnell method for observing human affairs, and complains that "there seems to be no place in Grinnell’s method for analysis, just the ongoing

accumulation of information".

Which is clearly why we also need extended reflection.

Annie Murphy Paul, How To Increase Your Powers of Observation (Time Ideas, May 2012)

Catherine Eberbach, Kevin Crowley From Everyday to Scientific Observation: How Children Learn to Observe the Biologist’s World (abstract) Review of Educational Research March 2009 vol. 79 no. 1 39-68 doi: 10.3102/0034654308325899

Cathryn Carson, Writing, Writing, Writing: The Natural History Field Journal as a Literary Text (Feb 2007)

Jamie Cromertie, How to keep your field notes and journal,

Sheldon Greaves, Making, Maintaining, and Using Serious Field Notes (Feb 2012)

Paul Handford, Notes on Keeping a Field Journal,

Betsy Mason, Beautiful Data: The Art of Science Field Notes (Wired Science, July 2011)

Places are still available on my Organizational Intelligence workshop, November 22nd.

Published on November 12, 2012 17:24

On Agility, Culture and Intelligence

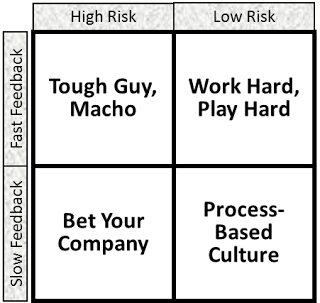

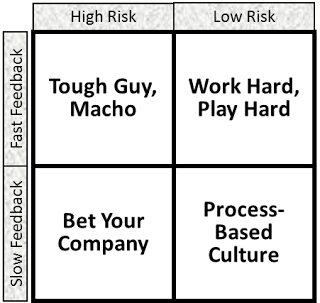

Deal and Kennedy (1982) proposed a model of organizational culture, which depended on two factors, risk and the speed of feedback.

Source: Deal and Kennedy

Meanwhile, speed of feedback also affects organizational intelligence. Shorter feedback loops are associated with greater agility and responsiveness, and faster learning, and is a popular meme of the Agile Software movement. Shahzad Bhatti is one of those who emphasizes the link with John Boyd's OODA loop.

So that seems to associate Agile with the upper two quadrants of the Deal and Kennedy model, and OODA with the top left quadrant.

So then what are the cultural implications of Agile for the host organization?

Notes and references

Lisa Crispin, Shortening the Feedback Loop (March 2011)

Ilan Kirschenbaum, What does a butterfly say at the end of the day? (May 2012)

Rune Larsen, Know your feedback loop – why and how to optimize it (Oct 2012)

Thomas Sundberg, Why should you use different technical practises when you develop software? (April 2011)

Places are still available on my Organizational Intelligence workshop, November 22nd.

Source: Deal and Kennedy

Meanwhile, speed of feedback also affects organizational intelligence. Shorter feedback loops are associated with greater agility and responsiveness, and faster learning, and is a popular meme of the Agile Software movement. Shahzad Bhatti is one of those who emphasizes the link with John Boyd's OODA loop.

"One of key finding he made was that shorter feedback or iteration loop

of OODA with low quality was better than longer or tiring cycle of OODA

with high quality. Despite the fact that everyone calls his/her

organization agile, this feedback loop is real essense of agility."

So that seems to associate Agile with the upper two quadrants of the Deal and Kennedy model, and OODA with the top left quadrant.

So then what are the cultural implications of Agile for the host organization?

Notes and references

Lisa Crispin, Shortening the Feedback Loop (March 2011)

Ilan Kirschenbaum, What does a butterfly say at the end of the day? (May 2012)

Rune Larsen, Know your feedback loop – why and how to optimize it (Oct 2012)

Thomas Sundberg, Why should you use different technical practises when you develop software? (April 2011)

Places are still available on my Organizational Intelligence workshop, November 22nd.

Published on November 12, 2012 16:58