Ronald E. Yates's Blog, page 86

September 19, 2018

The “TREAT” Reads Blog Hop! Day 2

(NOTE: For the next few days ForeignCorrespondent will be hosting the second annual RRBC “TREAT’ Reads Blog Hop. #RRBC #RRBCTreatReads)

“Greetings! Welcome to the 2nd RRBC “TREAT” Reads Blog Hop! These members of RRBC have penned and published some really great reads and we’d like to honor and showcase their talent. Oddly, all of the listed Winners are RWISA members! Way to go RWISA!

We ask that you pick up a copy of the title listed, and after reading it, leave a review. There will be other books on tour for the next few days, so please visit the “HOP’S” main page to follow along.

Also, for every comment that you leave along this tour, including on the “HOP’S” main page, your name will be entered into a drawing for a gift card to be awarded at the end of the tour!”

[image error] Author, Mary Adler

Book: IN THE SHADOW OF LIES – https://www.amazon.com/dp/B00K7WYTSU/

Book Blurb: Richmond, California. World War II. Marine Lieutenant Oliver Wright comes home from the war in the Pacific injured and afraid his career as a homicide detective is over. But when an Italian Prisoner of War is murdered the night the Port Chicago Mutiny verdicts are announced, and black soldiers are suspected of the crime, the Army asks Oliver to find out the truth.

He and his canine partner Harley join forces with an Italian POW captain and with a black MP embittered by a segregated military. During their investigation, these unlikely allies expose layers of deceit and violence that stretch back to World War I and uncover a common thread that connects the murder to earlier crimes.

In the Shadow of Lies reveals the darkness and turmoil of the Bay Area during World War II, while celebrating the spirit of the everyday people who made up the home front. Its intriguing characters will resonate with the reader long after its deftly intertwined mysteries are solved.

Twitter: @MAAdlerWrites

My Review of In “The Shadow of Lies”

In the Shadow of Lies—A menacing mystery

When I began reading M.A. Adler’s “In the Shadow of Lies” I couldn’t help but think of the day I spent with Joe DiMaggio at his restaurant near San Francisco’s Fisherman’s Wharf. He had just turned 65, and I was there to do a profile on the Yankee Clipper for my newspaper, the Chicago Tribune.

Joe wasn’t much of a talker, but on that day he talked about a lot of things. One of the things he talked about was what it was like growing up as an Italian-American kid in San Francisco in the late 1920s and early 1930s. Then, the topic turned to the 1940s and World War II. Joe told me about how during the war, the U.S. government seized the fishing boats of Italian-Americans who docked at the wharf—including the one operated by Joe’s father Giuseppe DiMaggio—an immigrant from Italy.

He told me how thousands of Italian-Americans lived under nightly house arrest, with a curfew from 8 p.m. to 6 a.m. His parents could not travel more than 5 miles from home without a permit. And here was “Joltin’ Joe,” who was not only a super-star center fielder with the New York Yankees but who was serving with the U.S. Army Air Force during the war.

That rather long preamble is my way of introducing you to this marvelous debut novel about the Italian-Americans and the Italian POW’s who shape much of the plot of this book. The San Francisco that Tony Bennett sings about is NOT the San Francisco that Ms. Adler depicts in this book—not by a long shot. Her San Francisco may be a “City on a Hill,” but it’s also a dark place rife with intrigue, racial tension, bigotry, and murder.

Oliver Wright is Adler’s chief protagonist. He’s a city detective, and the setting is the city of Richmond, located in the East Bay region of San Francisco Bay. The story begins with the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor—an event that propels the U.S. into World War II. There are multiple threads and subplots as the story progresses, in some cases, almost too many. You will need to pay attention to the twists and the plethora of new characters.

In fact, there are so many characters that Adler has a page at the beginning that lists the families portrayed in the book—the Flemings, the Wrights, the Fioris, the Slaters, the Buonarottis, and the Hermits. But fear not. Oliver’s character is well-developed, and he is the thread that binds this complex narrative together.

Adler is an excellent wordsmith as evidenced by this delightful bit of descriptive prose:

“The wily old fox had timed it perfectly: the rainy September day, the cemetery, the weeping mother huddled with her son under a black umbrella, a clichéd study in grays and blacks that evoked a memory of another coffin’s descent into the earth, a memory that stirred Oliver Wright’s guilt and made him so deeply tired that he slid into the thankless habit of trying to please his father. They had barely returned from the Fleming children’s funeral when Oliver’s father summoned him to the study.”

Adler’s prose is supported by the prodigious amount of research she clearly did to reconstruct the San Francisco area of the 1940s. She reveals the kind of overt prejudice that existed for African-Americans in the military as well as the hysteria that gripped both the public and the government that resulted in rampant discrimination against Japanese-Americans, Italian-Americans, and others. She does a masterful job of capturing the widespread unbridled fear that many on the West Coast felt in the wake of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. It was a palpable dread and panic. Would San Francisco be the next target for Japanese planes? Would Japanese troops land in Marin County and sweep south into San Francisco? It may sound absurd today, but in 1941 these were genuine apprehensions.

Adler also does a splendid job of reconstructing the battle for Guam where Oliver serves with the U.S. Marines. The scenes are short and crisp, and we come to respect Oliver for the concern he shows for Harley, his K-9 German Shepherd partner, even after he is wounded in battle.

I won’t go any further into the plot. Suffice it to say that the plot is multifaceted and involved as it covers several years. Be patient as this intricate story unfolds.

So, you might ask, is this a novel worth your time and money? You bet it is. It will keep you busy and profoundly engaged. What more can you want from a book?

JOIN ME FOR ALL OF THE BOOKS IN THE “TREAT” READS BLOG HOP

(Just type #RRBCTreatReads in your Twitter search box.)

Tuesday, 9/18/18: “THE IMPROBABLE JOURNEYS OF BILLY BATTLES” by Ronald Yates

Wednesday, 9/19/18: “IN THE SHADOW OF LIES” by Mary Adler

Thursday, 9/20/18: “LETTING GO INTO PERFECT LOVE” by Gwen Plano

Friday, 9/21/18: “SON OF MY FATHER” by Peggy Hattendorf

Saturday, 9/22/18: “EXCLUSIVE PEDIGREE” by Robert Fear

Sunday, 9/23/18: “ONE DYKE COZY” by Rhani D’Chae

Monday, 9/24/18: “OUTSHINE” by Karen Ingalls

Tuesday, 9/25/18: “TURPITUDE” by Bernard Foong

Wednesday, 9/26/18: “DOG BONE SOUP” by Bette A. Stevens

Thursday, 9/27/18: “HIEROGLYPH” by Wendy Scott

Friday, 9/28/18: “THE WAY TO HER HEART” by Amy Reece

Saturday, 9/29/18: “ELEMENTS” by Nia Markos

Sunday, 9/30/18: “DESTINY’S PLAN” by Victoria Saccenti

September 18, 2018

Join the RRBC “Treat” Reads Blog Hop

(NOTE: From Sept. 19 to Sept. 30 ForeignCorrespondent will be hosting the second annual RRBC “TREAT’ Reads Blog Hop. I hope you will check out these great reads from my fellow authors in the Rave Reviews Book Club (RRBC) and the Rave Waves International Society of Authors (RWISA). #RRBC #RRBCTreatReads)

Word Play Masters Invitational: It’s a Hoot!

Since 2010 Word Play Masters has run a contest circulated on the Web in which readers are asked to take any word from the dictionary, alter it by adding, subtracting, or changing one letter, and then supplying a new definition.

As a writer, I have always been fascinated by words, how they are formed, and their definitions. I know, I know, an interest like that borders on abject nerdiness. But I can’t help it. For more than 30 years I have made my living by stringing words together, and these articulations grabbed my attention and refused to let go.

Take a look for yourself. And if you can think of any words to contribute, the wordsmiths at WordPlay Masters have issued the following memorandum:

“Please feel free to send us your words and definitions on the Submit Words page. We’ll post anything that’s clean (meaning your very bright seven-year-old can read it without you wincing). Once a year we’ll have a contest to determine the winners (with no scientific validity whatsoever). If you want to enter the contest, there’s nothing to do but send in a word for consideration. A panel of “experts,” made up of some clever previous winners, determines the final winners each year.”

The Brainiacs at WordPlay Masters point out that for years an email has been circulating about something called the “Washington Post’s Mensa Invitational” which includes a very clever list of “new” words. However, they have issued the following disclaimer:

“THIS SITE IS NOT ASSOCIATED WITH THE WASHINGTON POST!”

Here are a few winners from the past few years.

Cashtration (n.): The act of buying (or building) a house, which renders the subject financially impotent for an indefinite period.

Ignoranus: A person who’s both stupid and an asshole.

Intaxication: Euphoria at getting a tax refund, which lasts until you realize that it was your money to start with.

Reintarnation: Coming back to life as a hillbilly.

Bozone (n.): The substance surrounding stupid people that stops bright ideas from penetrating. The bozone layer, unfortunately, shows little sign of breaking down in the near future.

Foreploy: Any misrepresentation about yourself for the purpose of getting laid.

Giraffiti: Vandalism spray-painted very, very high

Sarchasm: The gulf between the author of sarcastic wit and the person who doesn’t get it.

Inoculatte: To take coffee intravenously when you are running late.

Hipatitis: Terminal coolness.

Osteopornosis: A degenerate disease. (This one got extra credit.)

Karmageddon: It’s when everybody is sending off all these really bad vibes, and then the Earth explodes, and it’s a serious bummer.

Decafalon (n.): The grueling event of getting through the day consuming only things that are good for you

Glibido: All talk and no action.

Dopeler effect: The tendency of stupid ideas to seem smarter when they come at you rapidly.

Beelzebug (n.): Satan in the form of a mosquito, that gets into your bedroom at three in the morning and cannot be cast out.

Caterpallor (n.): The color you turn after finding half a worm in the fruit you’re eating.

Here is another list of winning submissions in which readers are asked to supply alternate meanings for common words.

And the winners are:

Coffee, n. The person upon whom one coughs.

Flabbergasted, adj. Appalled by discovering how much weight one has gained.

Abdicate, v. To give up all hope of ever having a flat stomach.

Esplanade, v. To attempt an explanation while drunk.

Willy-Nilly, adj. Impotent.

Negligent, adj. Absentmindedly answering the door when wearing only a nightgown.

Lymph, v. To walk with a lisp.

Gargoyle, n. Olive-flavored mouthwash.

Flatulence, n. Emergency vehicle that picks up someone who has been run over by a steamroller.

Balderdash, n. A rapidly receding hairline.

Testicle, n. A humorous question on an exam.

Rectitude, n. The formal, dignified bearing adopted by proctologists.

Pokemon, n. A Rastafarian proctologist.

Oyster, n. A person who sprinkles his conversation with Yiddishisms.

Frisbeetarianism, n. The belief that, after death, the soul flies up onto the roof and gets stuck there.

Circumvent, n. An opening in the front of boxer shorts worn by Jewish men.

Let me know what you think and feel free to add your very own new word!

September 15, 2018

W. Somerset Maugham and the World’s Ten Greatest Novels

I began reading W. Somerset Maugham in the 1980s when I was covering Asia for the Chicago Tribune. Many of the places I worked and lived were the same places that Somerset Maugham set some of his books and short stories, so I felt it was my duty to get to know this author.

First, I began reading Maugham’s Malaysian Stories, which dealt with life at the end of British colonial rule in what was then called Malaya. I also read The Painted Veil, which is set mostly in Hong Kong.

Then I read The Razor’s Edge, which begins in Chicago where the protagonist, Larry Darrell, settles after being wounded and traumatized by the death of a close friend in World War I. He eventually travels to India seeking enlightenment, happiness, and some meaning to life. Does he find it? You will have to read The Razor’s Edge yourself to find out.

During Maugham’s prolific 90-year-long life he wrote 20 novels, 25 plays, and hundreds of short stories and magazine articles, many of which were made into movies.

[image error] W. Somerset Maugham

So, in 1958 when Maugham decided to list what he thought were the 10 best novels of all time, people took note. Not all agreed with him. I’m not sure I do either—after all, there have been many novels written before and after 1958 that surely qualify to be on that list.

Nevertheless, in his book, The World’s Ten Greatest Novels: Great Novels and Their Novelists, Maugham makes his choices and goes on to defend them in a series of brilliant essays.

Maugham’s list

Tom Jones

Pride and Prejudice

The Red and the Black

Old Man Goriot

David Copperfield

Wuthering Heights

Madame Bovary

Moby-Dick

War and Peace

The Brothers Karamazov

Not even the great Maugham, however, insists that his list is definitive and irrevocable. He even lists ten more books that he could just as easily listed as the “greatest.”

I will let Maugham himself explain his choices in these selected passages from his book. Please read on. You won’t be disappointed.

“Let me begin by saying that to talk of the ten best novels in the world is to talk nonsense. There are a hundred, though even of that I am far from sure; if fifty persons, well-read and of adequate culture, were to make lists of the hundred best novels in the world, at least two or three hundred, I believe, would be mentioned more than once; but I think that in these fifty lists, supposing they were made by persons of English speech, the ten novels I have chosen would find a place.

“Now this great diversity of opinion can be somewhat easily explained. There is a variety of reasons that may make a particular novel so much appeal to a person, even of sound judgment, that he is led to ascribe outstanding merit to it. It may be that he had read it at a time of life or in circumstances when he was particularly liable to be moved by it, or it may be that its theme or its setting has a more than ordinary significance for him owing to his own predilections or personal associations.

“But the chief reason for the great diversity of opinion that exists on the respective merits of novels comes, I think, from the fact that a novel is essentially an imperfect form. No novel is perfect. Of the ten I have chosen there is not one with which you cannot in some particular find fault.

“I think Balzac is the greatest novelist the world has ever known, but I think Tolstoy’s War and Peace is the greatest novel. No novel with such a wide sweep, dealing with so momentous a period of history and with such a vast array of characters, was ever written before, no, I surmise, will ever be written again. It has been justly called an epic. I can think of no other work of fiction that could with truth be so described.

“But before I enlarge upon this statement I wish to say something about readers of fiction. The novelist has the right to demand something of them. He has the right to demand that they should possess the small amount of application that is needed to read a book of three or four hundred pages.

“He has the right to demand that they should have sufficient imagination to be able to envisage the scenes in which the author seeks to interest them and to fill out in their own minds the portraits he has drawn. And finally, the novelist has the right to demand from his readers some power of sympathy, for without it they cannot enter into the loves and sorrows, tribulations, dangers, adventures of the persons of a novel. Unless the reader can give something of himself, he cannot get from a novel the best it has to give.

“Now I will specify what, in my opinion, are the qualities that a good novel should have. It should have a widely interesting theme, by which I mean a theme interesting not only to a clique, whether of critics, professors, highbrows, truck drivers or dishwashers, but so broadly human that it is interesting to men and women of all sorts.

“The story should be coherent and persuasive; it should have a beginning, a middle and an end, and the end should be the natural consequence of the beginning. The episodes should have probability and should not only develop the theme but grow out of the story. The creatures of the novelist’s invention should be observed with individuality, and their actions should proceed from their characters; the reader must never be allowed to say: So and so would never behave like that; on the contrary he should be obliged to say: That’s exactly how I should have expected so and so to behave. I think it is all the better if the characters are in themselves interesting.

“And just as behavior should proceed from character, so should speech. A fashionable woman should talk like a fashionable woman.

“The narrative passages should be vivid, to the point and no longer than is necessary to make the motives of the persons concerned and the situations in which they are placed clear and convincing. The writing should be simple enough for anyone of ordinary education to read it with ease, and the manner should fit the matter as a well-cut shoe fits a shapely foot. Finally, a novel should be entertaining.

“But even if the novel has all these qualities, and that is asking a lot, there is, like a flaw in a precious stone, a faultiness in the form that renders perfection impossible to attain.

“When I consider how many obstacles the novelist has to contend with, how many pitfalls to avoid, I am not surprised that even the greatest novels are not perfect, I am only surprised that they are not more imperfect than they are. It is largely on this account that it is impossible to pick out ten and say that they are the best.

“I could make a list of ten more that in their different ways are as good as those I have chosen: Anna Karenina, Crime and Punishment, Cousin Bette, The Charterhouse of Parma, Persuasion, Tristram Shandy, Vanity Fair, Middlemarch, The Ambassadors, Gil Blas. I could give good reasons for choosing those I have just mentioned. My choice is arbitrary.

“It is to induce readers to read them that this series has been designed. The attempt has been made to omit from these ten novels everything, but what tells the story the author has to tell, exposes his relevant ideas and displays with adequacy the characters he has created. Some students of literature, some professors and critics will exclaim that it is a shocking thing to mutilate a masterpiece and that it should be read as the author wrote it.

“But do they actually do this? I suggest that they skip what is not worth reading, and it may be that they have cultivated the art of skipping to their profit, but most people haven’t: it is surely better that they should have their skipping done for them by someone of taste and discrimination. If he has made a good job of it, he should be able to give the reader a novel of which he can read every word with enjoyment.

“They will lose nothing that is valuable, and because nothing is left in these volumes but what is valuable, they will enjoy to the full a very great intellectual pleasure.”

Maugham points out that three of the books on his list were considered “dead failures when first published,” referring to Moby-Dick, The Red and the Black, and Wuthering Heights. Maugham then explains why those three books were considered hopeless failures.

“Such critics as noticed them had little good to say of them. The public ignored them. That is easy to understand. They were highly original. Now, the world, in general, doesn’t know what to make of originality; it is startled out of its comfortable habits of thought, and its first reaction is one of anger. It needs a long time, and the guidance of perceptive interpreters before it can abandon its instinctive recoil and accustom itself to novelty.”

That last passage by Maugham should give all of those budding authors out there some hope that THEIR original work only needs to be seen by “perceptive interpreters” so it can hit the bestseller lists.

September 7, 2018

Judge Kavanaugh Survives 3 Days of Senate Grilling

Now that Judge Brett Kavanaugh has survived three days and almost 30 hours of examination and cross-examination by the 21-member Senate Judicial Committee it is only a matter of time before he is confirmed as the newest Supreme Court justice.

As someone who watched the ENTIRE three-days of the hearings, I feel like the old Alka-Seltzer TV commercial in which a man who ate several pounds of lasagna groans as he struggles to suppress a belch: “I can’t believe I ate the whole thing.”

Here are a few of my observations. Please forgive any belching.

I have never seen so many grandstanding senators struggling to get their moment under the TV lights. Of course, some, such as Cory Booker (N.J.) and Kamala Harris (Calif.) who are running for president in 2020 saw the Kavanaugh hearings as one of the first stops on their campaign trails. Both did their best to score points during the hearings, Booker going so far as to offer to be booted from the Senate for releasing a confidential document about Judge Kavanaugh’s stance on racial profiling. Nevermind that the document Booker threatened to “release” was made public the night before.

[image error] Sen. Cory Booker

One of the best moments of the hearings came Thursday when Republican Ben Sasse of Nebraska gave the committee and those watching a 15-minute civics lesson on the way the three branches of government (Executive, Legislative, and Judicial) should operate and then decried why hearings such as the Kavanaugh hearing have devolved into a circus of protests, TV cameras, and hateful speech.

“It’s because legislators who are supposed to make laws don’t really do it,” Sasse said. “They appoint bureaucrats to do what legislators should have done, and when things go wrong, as they always do, the public can’t find a face to blame and so they look to the most obvious thing: The nine people sitting on the Supreme Court, whose faces they can see and whose opinions they can excoriate.

“What we mostly do in Congress is not pass laws but permit bureaucracy X, Y, or Z to make law-like regulations. We write giant pieces of legislation with undefined terms — and then say the secretary of such-and-such shall promulgate rules that do the rest of our jobs. Legislators love power more than the people and job security more than preserving liberty. The reason this institution punts its power to exec-branch agencies is that it’s a convenient way to avoid responsibility for unpopular decisions. If your biggest long-term priority is just re-election, then, sadly, giving away power is a good strategy.”

I felt like applauding when I heard that. I suspect a lot of people in the hearing room felt the same way, but decorum prohibited such displays.

Of course, the concept of decorum was NOT a factor for the dozens of loudmouthed demonstrators who continually interrupted the hearings with shouts and insults hurled at Kavanaugh, President Trump, and members of the Judicial Committee. Over and over again Capitol Police hustled unruly and vociferous demonstrators from the room.

At several points during the hearing it was clear to me that many senators—especially those on the left side of the room—didn’t understand or didn’t want to acknowledge the fact that a judge does not make laws and policy, he follows them via legal precedent.

That point was lost on Democrat Senators like Dick Durbin of Illinois who grilled Kavanaugh on a case involving a pregnant teenage illegal immigrant who wanted an abortion while she was in the United States. “You are stopping her from getting an abortion,” Durbin asserted during one exchange.

[image error] Sen. Dick Durbin

“I’m not,” Kavanaugh responded. “I’m a judge. I’m not making the policy. My job is to decide whether that policy is consistent with law. What do I do? I look at the precedent.”

Durbin still didn’t get it, and he continually vilified Kavanaugh for his stance. So Kavanaugh had to repeatedly defend himself saying he was not the one responsible for the policy—he was a judge making a fair ruling on that policy.

After that exchange, it was manifestly clear to me how Democrat senators on the Judicial Committee view the U.S. Supreme Court. Not as a body charged with acting as the final judge in all cases involving laws made by Congress as well as the Constitution, but as a body that should bend and manipulate those laws and the Constitution to fit a particular political ideology.

If that’s the case, then it is little wonder why they so vehemently oppose Judge Kavanaugh’s appointment to the Supreme Court. He is a strict constitutionalist who believes in the inviolability of the Constitution, not in its continual undermining and deterioration the way so many on the left do today.

These hearings demonstrated that Kavanaugh believes in the sanctity of the First Amendment, the magnitude of the Second Amendment, and the importance of the remaining 25.

The First and Second, especially, have come under attack in recent years. Thank God Brett Kavanaugh, our next Supreme Court justice will be a bulwark against those who want to take away our rights of free speech and to keep and bear arms.

As for me, I think I have had enough Senate hearings to last me until I join the Great Majority.

And I still can’t believe I watched the WHOLE THING!

September 5, 2018

Judge Kavanaugh & the Senate Judiciary Committee Bar Brawl

The first day of confirmation hearings for Judge Brett Kavanaugh, President Trump’s Supreme Court pick, could just as well have been held in a bar instead of the U.S. Senate.

It was a raucous affair with people yelling, holding up placards, and a succession of Democrat senators (in a carefully orchestrated bit of theater) interrupting Senate Judiciary Committee chairman Chuck Grassley demanding that the hearing be adjourned before he could even get the inquiry underway.

“This is the first confirmation for a Supreme Court justice I’ve seen, basically, according to mob rule,” Republican Senator John Cornyn said.

Democrats charged that documents about Kavanaugh’s past had been withheld. Never mind that every Democrat on the committee has already said they will vote “No” on the Kavanaugh confirmation. They still wanted the documents “even if we are voting no; the American people have a right to see them.”

Republicans have said Democrats have more than enough documents (500,000 at last count) to assess Kavanaugh’s record, including his 12 years of judicial opinions as a judge on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit.

Democrats said the raucous disorderly and often harsh hearing was “democracy in action.”

To me, it looked like something akin to a bar fight waiting to happen. Insults flew back and forth between the left and the right, and more than 60 protestors were escorted from the hearing room and charged with disorderly conduct. Thank God no alcohol was being served or we might have seen flying chairs and beer bottles.

Is this American democracy in action? Some may say yes, but it didn’t seem that way to me.

The intensity of the disrespect, name-calling, and anger was so palpable and vicious that at one point Kavanaugh’s children were hustled out of the room. What a pitiable lesson about America’s representative form of government his daughters witnessed. How delightful it must have been for them to see their father insulted and vilified by obstreperous protestors and mean-minded Democrats in their bombastic opening statements.

During the first break, Judge Kavanaugh was approached from behind by a man holding out his hand. Security quickly hustled the judge away from the man, who we later learned was the father of one of the 17 victims in the Feb. 14 Parkland, Florida shootings.

Naturally, the incident was quickly politicized when the father, Fred Guttenberg, tweeted that the judge pulled away because “he did not want to deal with the reality of gun violence.”

In fact, Judge Kavanaugh had no idea who Guttenberg was or what his motive was in rushing after him. His security detail did the right thing in stepping between the two and ushering Kavanaugh out of the room.

Another father, Andrew Pollack, whose 18-year-old daughter Meadow was killed in the Parkland shooting, accused Guttenberg of “weaponizing Parkland to advance a dangerous political agenda.”

“Judge Kavanaugh was not responsible for the Parkland school shooting that killed my daughter,” Pollack tweeted. “Judge Kavanaugh is a decent man and should be confirmed.”

The hearing lasted seven hours, and I watched almost all of it—much to my dismay.

Today, the Q & A session begins. I wonder what kind of Guerilla Theater we will be treated to.

One thing is for sure; it will not be the kind of democratic process I learned about in any of my civics classes. Judge Kavanaugh should wear a Kevlar vest during the remainder of these alleged hearings.

[Stay tuned. I will be posting on the rest of this circus]

September 3, 2018

Test Your Knowledge of the Vietnam War

The Vietnam War ended 43 years ago on April 30. For those of us who lived through it and the turmoil it created in the United States, it still seems like yesterday. For those of you who view the war as ancient history, here’s a chance to test your knowledge.

Take this test to see how much you know about the war that divided our country more than any other war since the Civil War in 1861-65.

Click on the link below.

http://history.howstuffworks.com/historical-events/vietnam-war-quiz.htm.

August 24, 2018

Join Me Tomorrow at the San Diego Festival of Books

Click on the link below to see a short video about the festival and for more information take a look at the San Diego Union-Tribune story that follows.

By John Wilkens Contact Reporter

The day will begin with the announcement of the 2018 One Book, One San Diego selection, culled from 10 finalists. Then it’s on to the panels, 30 of them, up from a dozen last year.

Attendees can hear from more than 90 authors discussing a variety of topics: contemporary fiction, crime, and mysteries, military history, science-fiction, romance, sports, comics, the “dark side” of business, self-help, microbes.

Among the featured authors: Brit Bennett, whose debut novel, “The Mothers,” was a New York Times bestseller; Bill Walton, retired basketball star and memoir writer; crime novelists Lisa Brackmann, Matt Coyle and T. Jefferson Parker; Lynn Vincent and Sara Vladic, whose “Indianapolis” is enjoying success on themes’ non-fiction list; and children’s book illustrators Kadir Nelson and Janell Cannon.

[image error] Attendees at last year’s festival listen to authors during one of the panels. (Eduardo Contreras/Union-Tribune file photo)

Admission to the festival grounds is free, but the panels are ticketed at $3 each, with part of the proceeds benefiting the San Diego Council on Literacy. Last year, most of the panels sold out in advance.

There will also be a free panel called “Fake News, Real Problems,” featuring Union-Tribune editors Lora Cicalo and Matthew T. Hall, as well as Brooke Binkowski, former managing editor at Snopes, a fact-checking website.

For children, there will be a reading stage and an activities pavilion.

Dozens of writers will be in “Author Alley” and more than 60 exhibitors, including local bookstores, will be offering items and services for sale.

[image error] Signing books in Authors’ Alley

Tickets and more information are available by clicking on the following link:

August 21, 2018

Join Me Saturday, August 25 at the San Diego Festival of Books

By John Wilkens Contact Reporter

The day will begin with the announcement of the 2018 One Book, One San Diego selection, culled from 10 finalists. Then it’s on to the panels, 30 of them, up from a dozen last year.

Attendees can hear from more than 90 authors discussing a variety of topics: contemporary fiction, crime and mysteries, military history, science-fiction, romance, sports, comics, the “dark side” of business, self-help, microbes.

Among the featured authors: Brit Bennett, whose debut novel, “The Mothers,” was a New York Times bestseller; Bill Walton, retired basketball star and memoir writer; crime novelists Lisa Brackmann, Matt Coyle and T. Jefferson Parker; Lynn Vincent and Sara Vladic, whose “Indianapolis” is enjoying success on the mes’ non-fiction list; and children’s book illustrators Kadir Nelson and Janell Cannon.

[image error] Attendees at last year’s festival listen to authors during one of the panels. (Eduardo Contreras/Union-Tribune file photo)

Admission to the festival grounds is free, but the panels are ticketed at $3 each, with part of the proceeds benefiting the San Diego Council on Literacy. Last year, most of the panels sold out in advance.

There will also be a free panel called “Fake News, Real Problems,” featuring Union-Tribune editors Lora Cicalo and Matthew T. Hall, as well as Brooke Binkowski, former managing editor at Snopes, a fact-checking website.

For children, there will be a reading stage and an activities pavilion.

Dozens of writers will be in “Author Alley” and more than 60 exhibitors, including local bookstores, will be offering items and services for sale.

[image error] Signing books in Authors’ Alley

Tickets and more information are available by clicking on the following link:

July 19, 2018

Writing A Memoir: Five Common Misconceptions

I am pleased to share with my readers this post from award-winning author Marylee MacDonald, author of Bonds of Love & Blood and Montpelier Tomorrow. Marylee is also a teacher and writing coach and is the author of 7-Day Writer’s Bootcamp, a short course on writing. You can find out more about Marylee at her website: http://maryleemacdonaldauthor.com/

By Marylee MacDonald

[image error] Marylee MacDonald

So you’ve always dreamed of writing a memoir. Where should you start, and how can you get a handle on the big and small turning points, traumas, and people that constitute your life?

Are You Confused?

Writing a memoir is not simple. The writing itself takes far longer than beginning writers think it will.

Let’s take a hypothetical. Imagine getting a letter with this message.

“You’re about to embark on the most intense four years of your life. Welcome to Med School!”–Best regards, Dean of the Medical College of Grenada

You would be taken aback. “Gosh, I don’t think I even applied!”

On the other hand, if you’ve had a secret hankering to become a doctor, you might welcome such a letter. You would swallow hard, adjust your expectations, and prepare for the long hours that developing medical competency will take.

Plowing through to the end of an 80,000- to 110,000-word manuscript can feel similarly daunting. It can take years to figure out what you want to say and how you want to say it. And, then, you’ll start on revisions. Before you produce a readable and engaging book, your manuscript may go through five, ten, twenty, or thirty revisions.

Writing a Memoir Takes Courage

The act of putting words on the page–words that are but a faint approximation of the lived experience–requires a huge amount of emotional investment on your part. You may have to live in a place of emotional pain every time you sit down at the computer. And, even when you give this story your best, you will believe you have failed to tell it as it should be told.

So much for the hors d’oeuvre. Now for the meat.

Here are five misconceptions about memoirs. Think about them when your work is in the formative stage, and you’ll save yourself some grief.

Myth #1: Recovering From Trauma

Can writing a memoir help you recover from trauma? Possibly, but not necessarily. I’m amazed when folks say, “Oh, you wrote about getting trapped in a mine shaft for 91 days. I guess writing about the experience helped you put it behind you.”

People, there is a huge, huge difference between journaling to “work through the problem” and writing a memoir. If you have stuff to work through, then write faithfully in your journal and hope you can expunge the trauma or loss.

However, ask any vet who has PTSD issues, and you’ll find that memories or experiences are not so easily expunged. From my reading in neuropsychology, I believe the best bet for recovery involves cognitive behavioral therapy, desensitization therapy (talking/reliving the experience until it has lost its power to wound), and hypnosis. (For more about PTSD, check out these resources at the Veterans Administration. Writing a memoir is not therapeutic.

What writing a memoir can do is help you find the deeper truths. It can give you the satisfaction of making art. As memoirist Annie Dillard wrote:

Why are we reading if not in the hope that the writer will magnify and dramatize our days, will illuminate and inspire us with wisdom, courage, and the possibility of meaningfulness, and will press upon our minds the deepest mysteries, so that we may feel again their majesty and power?

Now, that’s a reason to write a memoir! Are you game?

Myth #2: Writing To Set the Record Straight

All of us feel aggrieved. We are disappointed that life hasn’t turned out the way we thought it would, that our good intentions go unrewarded, or that people who’ve done us an injustice get off scot free.

Those who have suffered childhood trauma–rape, incest, neglect, or abuse–may very well feel that the only way to sort out the lingering effects of that past is to wrestle it into submission via a memoir.

The problem is that any hint of victimhood will doom your book. If you come off as “someone to whom bad things happened,” readers will put the book down.

Life is hard enough for all of us. We want to know that it’s possible to survive, even in the direst circumstances. Readers want to be uplifted.

Ishmael Beah’s memoir, A Long Way Gone, is an example of violence, trauma, and reinvention. The point is that Beah, though showing us the dark place, doesn’t leave us stranded.

Can your memoir show us the resilience that wells up from within the human spirit? Can it offer hope?

Myth #3: Having a Monopoly on The Truth

In geometry, we might call Myth #3 a corollary to Myth #2.

One of the most fertile places to look for memoir material is childhood. That’s because children have greater access to their feelings. We haven’t yet learned to shut down or filter out what might be unacceptable if spoken aloud.

Another reason to tap into childhood is that our memories remain vivid with smells, sights, and “firsts” –dates, kisses, and defeats.

But the danger with using material from that portion of our pasts is that we may find ourselves mired in the “Little Matchgirl” (aka “The Poor Little Matchgirl”) syndrome. Read Hans Christian Andersen’s story here, and you’ll see what I mean.

Hans Christian Andersen’s “Little Match Girl” is an example of a protagonist who is a victim. Though she tries to escape in her imagination, she cannot help freezing to death.

Frank McCourt’s bestseller, Angela’s Ashes, taps into a similar vein. It’s a tearjerker of a childhood in which humor leavens the pathos. What’s so wonderful about this book is that McCourt stands the cliche of victimization on its head. Here’s an exce rpt:

rpt:

Frank McCourt waited until late in life to publish ANGELA’S ASHES. What makes his work so popular is “voice”–the voice that takes a wry look at a childhood of deprivation.

When you write your memoir, you must set the bar high, both in terms of objective truth and of what I call “truth of intention.” Consider the other people in your story. Note that McCourt sees his alcoholic father and long-suffering mother as “characters” crushed by poverty, religion, colonialism, and tradition. He pities them.

Can you find it in your heart to forgive?

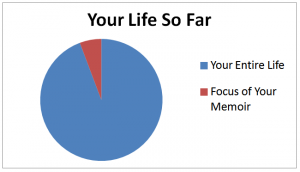

Myth #4: Writing the Whole Life, Not Just Part

The instant you embark on a memoir, you will discover one of its biggest myths–the illusion that the book must cover your whole life, not just part of it. You don’t have to emulate Frank McCourt, looking back on a long life. (If you’re young you haven’t lived it yet!) The easier path in this memoir-writing endeavor is to write about part of your life.

When you’re writing a memoir, think about which slice of the pie will be the most interesting for the reader. Focus on one event, theme, or subject, and let the remainder of your life stay in the background.

Pin the above visual above your writing desk. Narrow your focus. Find and read memoirs that start in medias res–in the middle of the action. Put readers there with you, and you’ll win their loyalty.

The excerpt below comes from Tobias Wolff’s In Pharoah’s Army: Memories of the Lost War. Wolff would rather show than tell. He allows us make up our own minds about Vietnam.

Tobias Wolff selected one slice of life to write about–the Vietnam war. His memoir, IN PHAROAH’S ARMY, has been called one of the finest books ever written about armed conflict, and yet it’s told through the lens of one man’s war experience. What makes memoirs so compelling is that they are particular stories (of one individual); but, in the particular, readers find universal truths.

Myth #5: You Are Writing A Memoir Only For Family Members

My granddaughters are always bugging me to write about my life. “Grandma, you were a carpenter. That’s awesome!” Or “Grandma, you were a single mom. How did you do it?”

But, what they actually want, and what I would love to provide, is a document that will help them make up for the time we didn’t know each other. My young mommy years, when I made my kids eat five bites. And to take that back further, my teenage years, when the hormones raged and decades of either/or choices lay before me.

When we are young, we have all the time in the world. And, yet, I know that if I penned even a short memoir about the days before cell phones and social media, my eager admirers would grow bored.

No one can bear to read a book that has no tension. A straight, chronological retelling of the past will bore readers and remind them of how they feel on a long plane flight with a seatmate who yammers in their ear.

If you want to write a memoir, learn from others who have written them.

Two Resources to Make Your Memoir a Success

Mary Karr has just published The Art of the Memoir. It’s a funny and thoughtful book that will give you the benefit of her wisdom. If you aspire to “become a writer,” read it. (Karr is the author of several bestselling memoirs, one of which is The Liar’s Club.)

Another resource you might explore is the National Association of Memoir Writers, founded by Linda Joy Myers, herself a memoirist and author of Don’t Call Me Mother. This site is especially good for beginning writers. NAMW’s podcasts contain a ton of information about writing memoirs and getting them published.

Writing a memoir can be a great way to share what life has taught you about the human condition. If you can find humor in the ordinary and compassion for those who’ve wronged you, you’re halfway to your goal.

I’d love to know whether you’ve attempted a memoir or whether you prefer fiction. http://maryleemacdonaldauthor.com/