Ronald E. Yates's Blog, page 108

February 13, 2015

TYSON-DOUGLAS SHOCKER REVISITED

TYSON-DOUGLAS SHOCKER REVISITED

Back in Feb. 1990, when I was the Chicago Tribune's Tokyo Bureau Chief, I covered the Mike Tyson-Buster Douglas heavyweight champion fight in Tokyo, one of greatest upsets ever.

For the past few weeks the Japan Times has been running a fascinating series of stories about that historic event written by reporter Ed Odeven. In them he interviewed a wide range of folks, including Buster Douglas himself.

Ed also interviewed a few of us who covered the fight in the vast Tokyo Dome. You can access those stories by clicking on the links below.

I have also included the story I filed for the Chicago Tribune that day. Take a look.

The series archival link: http://www.japantimes.co.jp/sports/column/tyson-douglas-shocker-revisited/

http://www.japantimes.co.jp/sports/2015/02/12/more-sports/boxing-2/ringside-reporters-recall-date-destiny/

Douglas KO's Tyson in 10; Champion floored by right hook

By Ronald E. Yates

TOKYO--Mike Tyson, a prohibitive favorite to retain his world heavyweight championship, was floored in the 10th round of his bout with James "Buster" Douglas Sunday in one of boxing history's biggest upsets.With a mild typhoon howling outside the [image error]Tokyo Domeand an unbelieving crowd of some 40,000 shrieking inside, Douglas peppered Tyson with a right uppercut, several left-right combinations and a crushing right hook to send the former undefeated champion crashing to the canvas.Tyson, his left eye swollen shut and his knees still weak, couldn't climb to his feet in time to beat the count by referee Octavio Meyran Sanchez.For a moment those at ringside seemed stunned at what had happened and Tyson, himself, seemed unable to grasp what had just happened. He looked across the ring at a jubilant, unmarked Douglas as Douglas hoisted his 11-year-old son Lamar in the air."You did it, Daddy, you did it," the youngster said."I sure did," Douglas said, breaking down in tears as he hugged his son."I did it for my mother," Douglas said, wiping tears from his eyes. Douglas' mother, Lula Pearl Douglas, died in mid-January just before Douglas was due to travel to Tokyo to train for his fight with Tyson. "I sure did it, didn't I," he said.Indeed, he did. But earlier in the eighth round, it appeared it would be business as usual for Tyson when he caught Douglas with a crunching uppercut that sent the 6-foot-4-inch, 233-pound challenger crumbling to the canvas.The fight might have ended there, but the knockdown came at the end of the round and Douglas was able to stagger back to his corner where his cornermen worked feverishly to revive him.Tyson, who lacked the fire and intensity of previous fights, uncharacteristically failed to press his advantage in the ninth round and allowed Douglas to regain his strength and composure. As the ninth ended, Douglas peppered Tyson with left-right combinations-a harbinger of what was to come for Tyson in the fateful 10th.Through most of the fight Tyson had difficulty getting inside the awkward Douglas' 12-inch reach advantage and resorted to lunging at the taller fighter. Douglas responded with left jabs to Tyson's head, which kept the former champion at bay.Though Tyson managed to walk from the ring, when he got under the [image error]Tokyo Dome's stands, his cornermen carried him down the steps to his dressing room."No comment, no comment," Tyson's entourage shouted at reporters who mobbed the former champion's dressing room. "This room is off limits!"Tyson also refused to conduct a post-fight interview with [image error]Home Box Office fight analyst Sugar Ray Leonard. HBO beamed the fight back to the United States.Back in the middle of the ring, Douglas, who seemed dazed by his historic upset, waved to the crowd and shouted at the Japanese audience:"Thank you for making me and my son and my trainers feel so at home here in Japan. Thank you for making all of this possible."Even more dazed than Douglas was Evander Holyfield, the undefeated top-ranked challenger that Tyson was to have fought June 18 at Atlantic City."It was a great fight for Douglas," said Holyfield. "He was the best man tonight. No doubt about it. But this didn't look like the Mike Tyson I've watched before.""We rooted hard for Mike Tyson," said Dan Duva, Holyfield's promoter. "Now it's back to the drawing boards."A Holyfield-Douglas matchup will not carry the luster nor the money of a fight with Tyson, admitted promoter Don King."My goal is to be world heavyweight champion and I don't care who I have to fight to reach it," said Holyfield. "Douglas has the championship now, so he's the one I want to fight."For their efforts Saturday night, Tyson reportedly earned $9 million and Douglas $1 million.Douglas, 30-4-1, was too busy celebrating to think about his next opponent."Let me enjoy this one first," he said, when asked if Holyfield would be his next opponent.Douglas seemed to take command of the fight from the opening bell and won the first three rounds as the frustrated Tyson tried unsuccessfully to reach his taller opponent.By the fourth round Tyson had battled back with punishing body shots that seemed to hurt Douglas. Both fighters appeared to tire in the sixth round with Tyson still unable to connect against Douglas.In the seventh and eighth rounds both fighters traded jabs and combinations until Tyson connected with a vicious uppercut that dropped Douglas in the end of the eighth.With Tyson unable to put Douglas away in the ninth, the challenger peppered the champion with five straight punches that closed his left eye completely.The fight was Tyson's 10th title defense-the last six of which had ended in knockouts.As Douglas sent Tyson crashing to the canvas, an American judge had the challenger ahead on points 88-82. One of two Japanese judges had the fight scored 87-86 for Tyson while the last judge had it 86-86."I don't think Mike was hungry enough today," said Holyfield.The prospect of Tyson stepping into the ring against Douglas had electrified the Japanese about as much as a plate of yesterday's sushi. That was reflected in the slow ticket sales for the 63,000-seat [image error]Tokyo Dome, a facility normally used for baseball by Japan's champion Yomiuri Giants.Ironically, some 2,000 ringside "Golden Seats" sold briskly at $1,035 each, snapped up by Japanese corporations as gifts to top customers and perks for executives, and by Japanese and foreign celebrities such as the Rolling Stones (in town for a series of concerts) and New York real estate tycoon Donald Trump, along with several Japanese pop singers, movie stars and television personalities.However, a [image error]Tokyo Domeofficial confided before the fight that more than half the remaining 60,000 tickets were still unsold.It took King to keep the usually kinetic Japanese press and public pumped up for the contest, a formidable task after reporters were invited to watch the 5-foot-11-inch Tyson walk through several listless practice bouts with taller sparring partners such as Greg Page and Phillip Brown.The most excitement generated during the three-week run up to the fight came when Page floored Tyson with a short right during a sparring session two weeks ago.

Published on February 13, 2015 15:54

February 6, 2015

BRIAN WILLIAMS AND JOURNALISTIC CREDIBILITY

For a journalist credibility is everything. Without it what you write, what you say, what you report lacks the critical ring of truth.

Credibility, or more accurately, the loss of it, is what has happened to NBC News anchor Brian Williams in the wake of his false claim that in 2003 while in Iraq he had been in a helicopter hit by an RPG (rocket propelled grenade).

In fact, as Williams himself now admits, that story is simply not true.

He was never in a helicopter that was forced to make an emergency landing because it was hit by an RPG. In fact, he arrived about an hour after the choppers that had been hit by RPG's had already made their emergency landings.

Williams apologized for the fabrication recently during NBC's Nightly News broadcast:

"I made a mistake in recalling the events of 12 years ago. I want to apologize." He added that: “I have no desire to fictionalize my experience and no need to dramatize events as they actually happened. I think the constant viewing of the video showing us inspecting the impact area — and the fog of memory over 12 years — made me conflate the two, and I apologize.” NBC News Anchor Brian Williams

NBC News Anchor Brian Williams

Here's the problem with that statement. Anybody who has ever been in war as a combatant or covered war as a correspondent, as I have, NEVER forgets a near death experience--and that's what being hit by an RPG in a helicopter then crash landing would definitely be.

I recall once lying flat in the bottom of a putrid ditch during a mortar attack on a village in Vietnam's Tay Ninh province and thinking for sure that the next shell was going to land on top of me.

"Don't worry," someone who was hunkered in the ditch with me said, "you never hear the one that gets you."

That was little consolation at the time, but the experience is still etched deeply in my memory bank.

That's why the "fog of memory" is simply not a valid excuse. Williams insists he conflated his inspection of the impact area of those damaged choppers with "thinking" or "remembering" that he was aboard one of the targeted helicopters.

Perhaps it was wishful thinking. After all, if you as an NBC correspondent, can say you were almost killed covering war, in the sometimes flaky and dodgy world of television journalism that goes a long way toward increasing your on-air persona--not to mention an increase in salary.

Now it appears Williams fabricated another story while covering Hurricane Katrina in New Orleans back in 2005. Williams claims to have seen a dead body float past the window of the five-star hotel where he was staying in the French Quarter.

"When you look out of your hotel room window in the French Quarter and watch a man float by face-down, when you see bodies that you last saw in Banda Aceh, Indonesia, and swore to yourself that you would never see in your country," he said in a 2006 interview. "I beat that storm. I was there before it arrived. I rode it out with people who later died in the Superdome."

The fact is there were no corpses floating through the French Quarter because it is on higher ground and was, therefore, spared the rising floodwaters that devastated other neighborhoods when the levees broke.

An unlike the evacuees in the Superdome in the days following the storm, Williams was ensconced in an NBC News RV compound on Canal Street with food and drinks along with a bevy of producers and military-trained security. He did not endure the mayhem that evacuees went through overnight and days afterward.

The sad truth is that television news is seen today more as entertainment and less as journalism--and its starsnot only must be protected, but relentlessly well-groomed.

Television journalists are often viewed the same way Hollywood actors are viewed--superstars who earn substantial salaries. And regrettably, like their Hollywood brethren, they sometimes have difficulty discerning fact from fiction. As such, they sometimes write or present the news to fit their perception of reality, rather than cover it impartially.

Like Williams they often have an inflated view of their own importance.

I am reminded of what English playwright Tom Stoppard had to say about journalists like Williams:

"He's someone who flies around from hotel to hotel and thinks that the most interesting thing about any story is the fact that he has arrived to cover it."

Credibility, or more accurately, the loss of it, is what has happened to NBC News anchor Brian Williams in the wake of his false claim that in 2003 while in Iraq he had been in a helicopter hit by an RPG (rocket propelled grenade).

In fact, as Williams himself now admits, that story is simply not true.

He was never in a helicopter that was forced to make an emergency landing because it was hit by an RPG. In fact, he arrived about an hour after the choppers that had been hit by RPG's had already made their emergency landings.

Williams apologized for the fabrication recently during NBC's Nightly News broadcast:

"I made a mistake in recalling the events of 12 years ago. I want to apologize." He added that: “I have no desire to fictionalize my experience and no need to dramatize events as they actually happened. I think the constant viewing of the video showing us inspecting the impact area — and the fog of memory over 12 years — made me conflate the two, and I apologize.”

NBC News Anchor Brian Williams

NBC News Anchor Brian Williams

Here's the problem with that statement. Anybody who has ever been in war as a combatant or covered war as a correspondent, as I have, NEVER forgets a near death experience--and that's what being hit by an RPG in a helicopter then crash landing would definitely be.

I recall once lying flat in the bottom of a putrid ditch during a mortar attack on a village in Vietnam's Tay Ninh province and thinking for sure that the next shell was going to land on top of me.

"Don't worry," someone who was hunkered in the ditch with me said, "you never hear the one that gets you."

That was little consolation at the time, but the experience is still etched deeply in my memory bank.

That's why the "fog of memory" is simply not a valid excuse. Williams insists he conflated his inspection of the impact area of those damaged choppers with "thinking" or "remembering" that he was aboard one of the targeted helicopters.

Perhaps it was wishful thinking. After all, if you as an NBC correspondent, can say you were almost killed covering war, in the sometimes flaky and dodgy world of television journalism that goes a long way toward increasing your on-air persona--not to mention an increase in salary.

Now it appears Williams fabricated another story while covering Hurricane Katrina in New Orleans back in 2005. Williams claims to have seen a dead body float past the window of the five-star hotel where he was staying in the French Quarter.

"When you look out of your hotel room window in the French Quarter and watch a man float by face-down, when you see bodies that you last saw in Banda Aceh, Indonesia, and swore to yourself that you would never see in your country," he said in a 2006 interview. "I beat that storm. I was there before it arrived. I rode it out with people who later died in the Superdome."

The fact is there were no corpses floating through the French Quarter because it is on higher ground and was, therefore, spared the rising floodwaters that devastated other neighborhoods when the levees broke.

An unlike the evacuees in the Superdome in the days following the storm, Williams was ensconced in an NBC News RV compound on Canal Street with food and drinks along with a bevy of producers and military-trained security. He did not endure the mayhem that evacuees went through overnight and days afterward.

The sad truth is that television news is seen today more as entertainment and less as journalism--and its starsnot only must be protected, but relentlessly well-groomed.

Television journalists are often viewed the same way Hollywood actors are viewed--superstars who earn substantial salaries. And regrettably, like their Hollywood brethren, they sometimes have difficulty discerning fact from fiction. As such, they sometimes write or present the news to fit their perception of reality, rather than cover it impartially.

Like Williams they often have an inflated view of their own importance.

I am reminded of what English playwright Tom Stoppard had to say about journalists like Williams:

"He's someone who flies around from hotel to hotel and thinks that the most interesting thing about any story is the fact that he has arrived to cover it."

Published on February 06, 2015 11:50

January 7, 2015

Here Are 11 Skills Your Great-Grandparents Had That You Don’t

Those of us who write historical fiction are always striving to make sure our characters are part of the time period in which our novels are set. A farmer in 19th Century Kansas, for example, had to know how to hunt and fish, how to forage and how to butcher livestock, clean chickens, and shoe a horse, etc.

There were no supermarkets, no computers or online shopping, no clothing stores or malls. Yes, there were Sears and Montgomery Ward catalogs where women could order ready-made dresses and men could order pants and shirts, but ordering from them was considered an infrequent luxury.

I recently received an e-mail from Ancestry.com, the online genealogy service that asked:

"How old school are you? Do you think you've got what it takes to live in your great-grandparents' era?"

I was intrigued by this question, having just completed the first book in a trilogy of novels, the first of which is set in the late 19th Century American West. As someone who spent time on a farm, who hunted and fished and cleaned hundreds of chickens, rabbits and squirrels, I figured I would be OK if I were suddenly transported to my great-grandparents' time.

But there was more to living back then than hunting and fishing. Life was much, much harder and so were the people.

Take a look at what Ancestry.com had to say:

Our parents and grandparents may shake their heads every time we grab our smart phones to get turn-by-turn directions or calculate the tip. But when it comes to life skills, our great-grandparents have us all beat. Here are some skills our great-grandparents had 90 years ago that most of us don’t.

1. CourtingWhile your parents and grandparents didn’t have the option to ask someone out on a date via text message, it’s highly likely that your great-grandparents didn’t have the option of dating at all. Until well into the 1920s, modern dating didn’t really exist. A gentleman would court a young lady by asking her or her parents for permission to call on the family. The potential couple would have a formal visit — with at least one parent chaperone present — and the man would leave a calling card. If the parents and young lady were impressed, he’d be invited back again and that would be the start of their romance.

2. Hunting, Fishing, and ForagingEven city dwellers in your great-grandparents’ generation had experience hunting, fishing, and foraging for food. If your great-grandparents never lived in a rural area or lived off the land, their parents probably did. Being able to kill, catch, or find your own food was considered an essential life skill no matter where one lived, especially during the Great Depression.

3. ButcheringIn this age of the boneless, skinless chicken breast, it’s unusual to have to chop up a whole chicken at home, let alone a whole cow. Despite the availability of professionally butchered and packaged meats, knowing how to cut up a side of beef or butcher a rabbit from her husband’s hunting trip was an ordinary part of a housewife’s skill set in the early 20th century. This didn’t leave the men off the hook, though. After all, they were most likely the ones who would field dress any animals they killed.

4. BarteringBefore the era of shopping malls and convenience stores, it was more common to trade goods and services with neighbors and shop owners. Home-canned foods, hand-made furniture, and other DIY goods were currency your great-grandparents could use in lieu of cash.

Before Clothes Dryers There was the Sun

Before Clothes Dryers There was the Sun

5. HagglingThough it’d be futile for you to argue with the barista at Starbucks about the price of a cup of coffee, your great-grandparents were expert hagglers. Back when corporate chains weren’t as ubiquitous, it was a lot easier to bargain with local shop owners and tradesmen. Chances are your great-grandparents bought very few things from a store anyway. 6. Darning and mendingNowadays if a sock gets a hole in it, you buy a new pair. But your great-grandparents didn’t let anything go to waste, not even a beat-up, old sock. This went for every other article of clothing as well. Darning socks and mending clothes was just par for the course.

7. Corresponding by mailObviously, your great-grandparents didn’t text or email. However, even though the telephone existed, it wasn’t the preferred method of staying in touch either, especially long-distance. Hand-written letters were the way they communicated with loved ones and took care of business.

8. Making LaceTatting, the art of making lace, was a widely popular activity for young women in your great-grandparents’ generation. Elaborate lace collars, doilies, and other decorative touches were signs of sophistication. However, fashion changed and technology made lace an easy and inexpensive to buy, so their children probably didn’t pick up the skill.

Tatting, the Art of Making Lace

Tatting, the Art of Making Lace

9. Lighting a Fire Without MatchesSure, matches have been around since the 1600s. But they were dangerous and toxic — sparking wildly out of control and emitting hazardous fumes. A more controllable, non-poisonous match wasn’t invented until 1910. So Great-grandma and Great-grandpa had to know a thing or two about lighting a fire without matches.

10. Diapering With ClothDisposable diapers weren’t commonly available until the 1930s. Until then, cloth diapers held with safety pins were where babies did their business. Great-grandma had a lot of unpleasant laundry on her hands.

11. Writing With a Fountain PenWhile it’s true that your grandparents were skilled in the lost art of writing in cursive, your grandparents probably were, too. However, the invention of the ballpoint pen in the late 1930s and other advances in pen technology mean that your great-grandparents were the last generation who had to refill their pens with ink.

Thanks to Ancestry.com for sharing this. I hope it helps you realize how easy you have it today compared to 100 years ago.

Here is a link to Ancestry.com's website: http://home.ancestry.com

There were no supermarkets, no computers or online shopping, no clothing stores or malls. Yes, there were Sears and Montgomery Ward catalogs where women could order ready-made dresses and men could order pants and shirts, but ordering from them was considered an infrequent luxury.

I recently received an e-mail from Ancestry.com, the online genealogy service that asked:

"How old school are you? Do you think you've got what it takes to live in your great-grandparents' era?"

I was intrigued by this question, having just completed the first book in a trilogy of novels, the first of which is set in the late 19th Century American West. As someone who spent time on a farm, who hunted and fished and cleaned hundreds of chickens, rabbits and squirrels, I figured I would be OK if I were suddenly transported to my great-grandparents' time.

But there was more to living back then than hunting and fishing. Life was much, much harder and so were the people.

Take a look at what Ancestry.com had to say:

Our parents and grandparents may shake their heads every time we grab our smart phones to get turn-by-turn directions or calculate the tip. But when it comes to life skills, our great-grandparents have us all beat. Here are some skills our great-grandparents had 90 years ago that most of us don’t.

1. CourtingWhile your parents and grandparents didn’t have the option to ask someone out on a date via text message, it’s highly likely that your great-grandparents didn’t have the option of dating at all. Until well into the 1920s, modern dating didn’t really exist. A gentleman would court a young lady by asking her or her parents for permission to call on the family. The potential couple would have a formal visit — with at least one parent chaperone present — and the man would leave a calling card. If the parents and young lady were impressed, he’d be invited back again and that would be the start of their romance.

2. Hunting, Fishing, and ForagingEven city dwellers in your great-grandparents’ generation had experience hunting, fishing, and foraging for food. If your great-grandparents never lived in a rural area or lived off the land, their parents probably did. Being able to kill, catch, or find your own food was considered an essential life skill no matter where one lived, especially during the Great Depression.

3. ButcheringIn this age of the boneless, skinless chicken breast, it’s unusual to have to chop up a whole chicken at home, let alone a whole cow. Despite the availability of professionally butchered and packaged meats, knowing how to cut up a side of beef or butcher a rabbit from her husband’s hunting trip was an ordinary part of a housewife’s skill set in the early 20th century. This didn’t leave the men off the hook, though. After all, they were most likely the ones who would field dress any animals they killed.

4. BarteringBefore the era of shopping malls and convenience stores, it was more common to trade goods and services with neighbors and shop owners. Home-canned foods, hand-made furniture, and other DIY goods were currency your great-grandparents could use in lieu of cash.

Before Clothes Dryers There was the Sun

Before Clothes Dryers There was the Sun

5. HagglingThough it’d be futile for you to argue with the barista at Starbucks about the price of a cup of coffee, your great-grandparents were expert hagglers. Back when corporate chains weren’t as ubiquitous, it was a lot easier to bargain with local shop owners and tradesmen. Chances are your great-grandparents bought very few things from a store anyway. 6. Darning and mendingNowadays if a sock gets a hole in it, you buy a new pair. But your great-grandparents didn’t let anything go to waste, not even a beat-up, old sock. This went for every other article of clothing as well. Darning socks and mending clothes was just par for the course.

7. Corresponding by mailObviously, your great-grandparents didn’t text or email. However, even though the telephone existed, it wasn’t the preferred method of staying in touch either, especially long-distance. Hand-written letters were the way they communicated with loved ones and took care of business.

8. Making LaceTatting, the art of making lace, was a widely popular activity for young women in your great-grandparents’ generation. Elaborate lace collars, doilies, and other decorative touches were signs of sophistication. However, fashion changed and technology made lace an easy and inexpensive to buy, so their children probably didn’t pick up the skill.

Tatting, the Art of Making Lace

Tatting, the Art of Making Lace

9. Lighting a Fire Without MatchesSure, matches have been around since the 1600s. But they were dangerous and toxic — sparking wildly out of control and emitting hazardous fumes. A more controllable, non-poisonous match wasn’t invented until 1910. So Great-grandma and Great-grandpa had to know a thing or two about lighting a fire without matches.

10. Diapering With ClothDisposable diapers weren’t commonly available until the 1930s. Until then, cloth diapers held with safety pins were where babies did their business. Great-grandma had a lot of unpleasant laundry on her hands.

11. Writing With a Fountain PenWhile it’s true that your grandparents were skilled in the lost art of writing in cursive, your grandparents probably were, too. However, the invention of the ballpoint pen in the late 1930s and other advances in pen technology mean that your great-grandparents were the last generation who had to refill their pens with ink.

Thanks to Ancestry.com for sharing this. I hope it helps you realize how easy you have it today compared to 100 years ago.

Here is a link to Ancestry.com's website: http://home.ancestry.com

Published on January 07, 2015 11:46

January 3, 2015

"JESSICA: PART 2" Blog Tour!

Periodically, my blog participates in virtual book tours which allow authors to showcase their books to a broader audience. Today I am hosting fellow author Jeffrey Von Glahn whose non-fction book "Jessica: The Autobiography of an Infant," is available on Amazon. The blog tour is sponsored by 4WillsPublishing.wordpress.com. (see relevant links below)

Jeffrey Von GlahnJeffrey Von Glahn has been a psychotherapist for 45 years, and counting. He says that experience has been, and continues to be, more exciting and fulfilling than he had ever imagined.

BOOK BLURB:

Jessica had always been haunted by the fear that the unthinkable had happened when she had been “made-up.” For as far back as she could remember, she had no sense of a Self. Her mother thought of her as the “perfect infant” because “she never wanted anything and she never needed anything.” As a child, just thinking of saying “I need” or “I want” left her feeling like an empty shell and that her mind was about to spin out of control. Terrified of who––or what––she was, she lived in constant dread over being found guilty of impersonating a human being.

Jeffrey Von Glahn, Ph.D., an experienced therapist with an unshakable belief in the healing powers of the human spirit, and Jessica, blaze a trail into this unexplored territory. As if she has, in fact, become an infant again, Jessica remembers in extraordinary detail events from the earliest days of her life––events that threatened to twist her embryonic humanness from its natural course of development. Her recollections are like listening to an infant who could talk describe every psychologically dramatic moment of its life as it was happening.

When Dr. Von Glahn met Jessica, she was 23. Everyone regarded her as a responsible, caring person – except that she never drove and she stayed at her mother’s when her husband worked nights.

For many months, Jessica’s therapy was stuck in an impasse. Dr. Von Glahn had absolutely no idea that she was so terrified over simply talking about herself. In hopes of breakthrough, she boldly asked for four hours of therapy a day, for three days a week, for six weeks. The mystery that was Jessica cracked open in dramatic fashion, and in a way that Dr. Von Glahn could never have imagined. Then she asked for four days a week – and for however long it took. In the following months, her electrifying journey into her mystifying past brought her ever closer to a final confrontation with the events that had threatened to forever strip her of her basic humanness.

BLOG POST:

This excerpt is from the Prologue. It describes how my view of infants was changed forever by Jessica’s revelations about her own infancy.

Listening to Jessica during therapy sessions was the same as listening to an infant who could talk describe in vivid detail every psychologically dramatic moment of its life as it was happening. As a result, my perception of infants was radically altered. I will never again think of them as simple little beings primarily interested in eating and sleeping. They are far more complex than I had ever imagined. When I am now in an infant’s presence, I am acutely conscious that an active force in the world is before me. What I say and how I act will be watched with great interest by a mind that, though not as developed as mine, is probably more curious about the world and definitely more sensitive to it.

Infants, especially newborns, pull me toward them with what seems like an irresistible power. Whenever I see one of these brand-new human beings, I must fight my urge to drop whatever I’m doing and immediately rush to its side. In my fantasy, I see myself slow down as I approach my goal and unhurriedly cover the last bit of distance. I close in with the most incredibly joyous smile anyone has ever seen. My eyes bulge in unabashed delight, while my smile and eyes speak for me. They speak the language of infancy, a life rich in feelings, hopes, dreams, potential, and an insatiable curiosity about the world. It is a life as exciting and intriguing as anything adults can even imagine.

My eyes and smile express the words I would like to say:

Yes, I know how powerful your mind is. I know what new information about yourself and the world you are trying to figure out. I know what fundamental psychological processes are happening inside of you. If you could talk, I know what wonderfully exciting details you would tell us about your life. My journey with Jessica seems—even now, after it’s over—more a flight of fancy, an excursion into science fiction, than a real-life story. Had I not been a fellow traveler who saw and heard everything with my own eyes and ears, I would certainly exclaim, “How interesting! I wish I could think of a clever story like that!”

PURCHASE LINKS:

Jeffrey Von Glahn - JESSICA: AN AUTOBIOGRAPHY OF AN INFANT -www.amazon.com/dp/B00IUCKOD8/

Goodreads Event Page - https://www.goodreads.com/event/show/950887-jessica-an-autobiography-of-an-infant-tour

Rafflecopter Page - http://www.rafflecopter.com/rafl/display/4af5be7f7/?

CONTACT INFO:

Twitter: @JeffreyVonGlahn Website: http://JeffreyVonGlahn.com

***This tour was sponsored by 4WillsPublishing.wordpress.com To book your own tour, please contact us.***

Jeffrey Von GlahnJeffrey Von Glahn has been a psychotherapist for 45 years, and counting. He says that experience has been, and continues to be, more exciting and fulfilling than he had ever imagined.

BOOK BLURB:

Jessica had always been haunted by the fear that the unthinkable had happened when she had been “made-up.” For as far back as she could remember, she had no sense of a Self. Her mother thought of her as the “perfect infant” because “she never wanted anything and she never needed anything.” As a child, just thinking of saying “I need” or “I want” left her feeling like an empty shell and that her mind was about to spin out of control. Terrified of who––or what––she was, she lived in constant dread over being found guilty of impersonating a human being.

Jeffrey Von Glahn, Ph.D., an experienced therapist with an unshakable belief in the healing powers of the human spirit, and Jessica, blaze a trail into this unexplored territory. As if she has, in fact, become an infant again, Jessica remembers in extraordinary detail events from the earliest days of her life––events that threatened to twist her embryonic humanness from its natural course of development. Her recollections are like listening to an infant who could talk describe every psychologically dramatic moment of its life as it was happening.

When Dr. Von Glahn met Jessica, she was 23. Everyone regarded her as a responsible, caring person – except that she never drove and she stayed at her mother’s when her husband worked nights.

For many months, Jessica’s therapy was stuck in an impasse. Dr. Von Glahn had absolutely no idea that she was so terrified over simply talking about herself. In hopes of breakthrough, she boldly asked for four hours of therapy a day, for three days a week, for six weeks. The mystery that was Jessica cracked open in dramatic fashion, and in a way that Dr. Von Glahn could never have imagined. Then she asked for four days a week – and for however long it took. In the following months, her electrifying journey into her mystifying past brought her ever closer to a final confrontation with the events that had threatened to forever strip her of her basic humanness.

BLOG POST:

This excerpt is from the Prologue. It describes how my view of infants was changed forever by Jessica’s revelations about her own infancy.

Listening to Jessica during therapy sessions was the same as listening to an infant who could talk describe in vivid detail every psychologically dramatic moment of its life as it was happening. As a result, my perception of infants was radically altered. I will never again think of them as simple little beings primarily interested in eating and sleeping. They are far more complex than I had ever imagined. When I am now in an infant’s presence, I am acutely conscious that an active force in the world is before me. What I say and how I act will be watched with great interest by a mind that, though not as developed as mine, is probably more curious about the world and definitely more sensitive to it.

Infants, especially newborns, pull me toward them with what seems like an irresistible power. Whenever I see one of these brand-new human beings, I must fight my urge to drop whatever I’m doing and immediately rush to its side. In my fantasy, I see myself slow down as I approach my goal and unhurriedly cover the last bit of distance. I close in with the most incredibly joyous smile anyone has ever seen. My eyes bulge in unabashed delight, while my smile and eyes speak for me. They speak the language of infancy, a life rich in feelings, hopes, dreams, potential, and an insatiable curiosity about the world. It is a life as exciting and intriguing as anything adults can even imagine.

My eyes and smile express the words I would like to say:

Yes, I know how powerful your mind is. I know what new information about yourself and the world you are trying to figure out. I know what fundamental psychological processes are happening inside of you. If you could talk, I know what wonderfully exciting details you would tell us about your life. My journey with Jessica seems—even now, after it’s over—more a flight of fancy, an excursion into science fiction, than a real-life story. Had I not been a fellow traveler who saw and heard everything with my own eyes and ears, I would certainly exclaim, “How interesting! I wish I could think of a clever story like that!”

PURCHASE LINKS:

Jeffrey Von Glahn - JESSICA: AN AUTOBIOGRAPHY OF AN INFANT -www.amazon.com/dp/B00IUCKOD8/

Goodreads Event Page - https://www.goodreads.com/event/show/950887-jessica-an-autobiography-of-an-infant-tour

Rafflecopter Page - http://www.rafflecopter.com/rafl/display/4af5be7f7/?

CONTACT INFO:

Twitter: @JeffreyVonGlahn Website: http://JeffreyVonGlahn.com

***This tour was sponsored by 4WillsPublishing.wordpress.com To book your own tour, please contact us.***

Published on January 03, 2015 22:01

December 24, 2014

'Unbroken' is an Unwelcome Film for Some Japanese

'Unbroken,' Angelina Jolie's film about the inhuman treatment of Allied captives in Japanese prisoner of war camps during World War II, is angering some Japanese who are calling for a boycott of the film in Japan.

The film, which opens Christmas day in the U.S., focuses mainly on the story of Louis Zamperini, who survived more than two years of horrendous treatment at the hands of his Japanese captors.

It is based on Laura Hillenbrand's bestselling book, "Unbroken," which detailed Zamperini's life as an Olympic athlete, his wartime role as a bombardier on a B-24 and his eventual capture by the Japanese after his plane was shot down.

Jolie and ZamperiniZamperini, who died this past July at the age of 97, forgave his captors for their merciless treatment of him and other POWS, but many Japanese are still unwilling to admit the atrocities their troops committed throughout Asia during World War II.

Jolie and ZamperiniZamperini, who died this past July at the age of 97, forgave his captors for their merciless treatment of him and other POWS, but many Japanese are still unwilling to admit the atrocities their troops committed throughout Asia during World War II.

This is not the first time a film about Japanese atrocities has sparked outrage in Japan.

In 1990, when I was the Chicago Tribune's Chief Asia Correspondent, I wrote about a graphic Australian film entitled 'Blood Oath.'

That film enraged Japanese Nationalists who still deny that the Imperial Japanese Army committed any wartime crimes--including the slaughter of some 200,000-300,000 Chinese civilians and unarmed POWs in the former Chinese capital of Nanjing in 1937.

'Blood Oath,' which was released in the U.S. under the title 'Prisoners of the Sun,' depicts the plight of Allied POWs from 1942 to 1945 on the Indonesian island of Ambon. Ambon was the site of one of Japan's most infamous prisoner of war camps. Of the 1,150 Australian, Dutch and American POWs interned on the island, fewer than 300 were still alive when British and Australian troops retook Ambon in 1945.

When they did, they made the grisly discovery of 314 decapitated POWs in one mass grave--beheaded by Japanese soldiers wielding razor-sharp samurai swords.

At the Australian War Crimes Tribunal held on Ambon in 1946 about half of the 91 Japanese officers and enlisted men accused as war criminals were convicted and given death sentences or long prison terms. Beheading of a Chinese POW"Most young Japanese today don't even know that Japan fought a war against the United States, let alone about what happened in Ambon," says Toshi Shioya, the Japanese actor who portrayed a soldier convicted and executed for war crimes committed on the Indonesian island of Ambon.

Beheading of a Chinese POW"Most young Japanese today don't even know that Japan fought a war against the United States, let alone about what happened in Ambon," says Toshi Shioya, the Japanese actor who portrayed a soldier convicted and executed for war crimes committed on the Indonesian island of Ambon.

Shioya not only acted in the film, but worked tirelessly to get it released in Japan.

"This was the first film ever shown in Japan that actually portrays ordinary Japanese soldiers as accomplices in war crimes," Shioya said. "We were lucky to find a distributor willing to show the film because for many Japanese, this was a shocking motion picture."

Unlike 'Prisoners of the Sun,' Jolie's 'Unbroken' is yet to be released in Japan. And while some Japanese may decry the film's portrayal of Japanese cruel treatment of Allied POW's, it is impossible to argue with the facts.

U.S. Department of Defense figures show that almost 40 per cent of all Americans taken prisoner by the Japanese died in captivity while just 1 per cent of American POWs died in Germany prisoner of war camps.

But unlike Germany, Japan's wartime iniquities have gone largely unpunished. There have been no Simon Wiesenthals to hunt down Japanese war criminals, and only a relative handful of Japanese military leaders were put on trial for atrocities.

As a result, generations of Japanese have grown up with only the sketchiest knowledge that Japan may have done something wrong in the 1930s and 1940s and that the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki were considered by many to be justifiable retribution.

Anti-Japanese feeling still exists in places like China and Korea where the heavy boot of Imperial Japan was most in evidence. In 1990, during a visit to Japan, then South Korean President Roh Tae Woo received an apology for Japan's 35-year occupation of the Korean peninsula from Emperor Akihito, the prime minister and parliament. But for many Koreans, none of the apologies went far enough.

"Human beings tend to be sensitive to and vividly remember their own sufferings," said Takashi Koshida, author of a two-volume work about the Japanese army's activities in 16 Asian nations during the war.

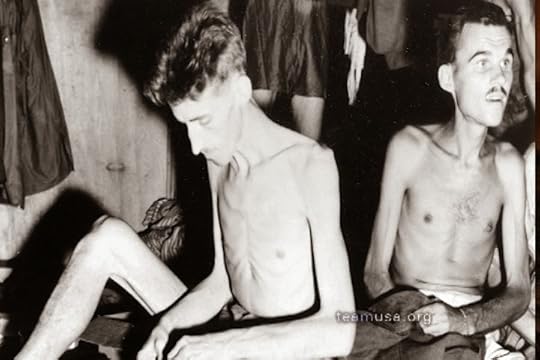

Zamperini when liberated from Japanese POW camp"In the case of the Japanese, the sufferings were the atomic bombings, the air raids and the military conscription. I would say it has taken almost 60 years for the Japanese to realize that they were aggressors . . . and that they caused other people to suffer."

Zamperini when liberated from Japanese POW camp"In the case of the Japanese, the sufferings were the atomic bombings, the air raids and the military conscription. I would say it has taken almost 60 years for the Japanese to realize that they were aggressors . . . and that they caused other people to suffer."

One group of Japanese for whom 'Prisoners of the Sun'has particular significance is the Ambon Remembrance Society, an organization of 100 Navy veterans who served as guards in the POW camp.

"After I watched this film the first time I felt as though I had swallowed lead. . . . I felt very heavy and dark inside," said Yoshiro Ninomiya, a former Navy sub-lieutenant assigned to the camp.Ninomiya, who is the society's secretary-general, has seen "Blood Oath" five times, and he said, "It has made me think about a lot of things (that happened on Ambon)."

Shioya has spent long hours talking with former Japanese soldiers who served at the camp.

"One man still has nightmares about what he did on the island," Shioya said. "This man, who served a 15-year prison sentence after the war, told me of how one day in 1943 he was ordered to decapitate three captured American pilots with his sword.

"As his sword passed through the neck of one pilot, photographs of the man's mother, his wife and a baby fell out of his shirt pocket and lay on the ground staring up at him. "He is still haunted by that scene today."

Check out these links for a trailer on Prisoners of the Sun and a synopsis by imdb.

http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0100414/

http://www.imdb.com/video/imdb/vi3165585689/

The film, which opens Christmas day in the U.S., focuses mainly on the story of Louis Zamperini, who survived more than two years of horrendous treatment at the hands of his Japanese captors.

It is based on Laura Hillenbrand's bestselling book, "Unbroken," which detailed Zamperini's life as an Olympic athlete, his wartime role as a bombardier on a B-24 and his eventual capture by the Japanese after his plane was shot down.

Jolie and ZamperiniZamperini, who died this past July at the age of 97, forgave his captors for their merciless treatment of him and other POWS, but many Japanese are still unwilling to admit the atrocities their troops committed throughout Asia during World War II.

Jolie and ZamperiniZamperini, who died this past July at the age of 97, forgave his captors for their merciless treatment of him and other POWS, but many Japanese are still unwilling to admit the atrocities their troops committed throughout Asia during World War II.This is not the first time a film about Japanese atrocities has sparked outrage in Japan.

In 1990, when I was the Chicago Tribune's Chief Asia Correspondent, I wrote about a graphic Australian film entitled 'Blood Oath.'

That film enraged Japanese Nationalists who still deny that the Imperial Japanese Army committed any wartime crimes--including the slaughter of some 200,000-300,000 Chinese civilians and unarmed POWs in the former Chinese capital of Nanjing in 1937.

'Blood Oath,' which was released in the U.S. under the title 'Prisoners of the Sun,' depicts the plight of Allied POWs from 1942 to 1945 on the Indonesian island of Ambon. Ambon was the site of one of Japan's most infamous prisoner of war camps. Of the 1,150 Australian, Dutch and American POWs interned on the island, fewer than 300 were still alive when British and Australian troops retook Ambon in 1945.

When they did, they made the grisly discovery of 314 decapitated POWs in one mass grave--beheaded by Japanese soldiers wielding razor-sharp samurai swords.

At the Australian War Crimes Tribunal held on Ambon in 1946 about half of the 91 Japanese officers and enlisted men accused as war criminals were convicted and given death sentences or long prison terms.

Beheading of a Chinese POW"Most young Japanese today don't even know that Japan fought a war against the United States, let alone about what happened in Ambon," says Toshi Shioya, the Japanese actor who portrayed a soldier convicted and executed for war crimes committed on the Indonesian island of Ambon.

Beheading of a Chinese POW"Most young Japanese today don't even know that Japan fought a war against the United States, let alone about what happened in Ambon," says Toshi Shioya, the Japanese actor who portrayed a soldier convicted and executed for war crimes committed on the Indonesian island of Ambon.Shioya not only acted in the film, but worked tirelessly to get it released in Japan.

"This was the first film ever shown in Japan that actually portrays ordinary Japanese soldiers as accomplices in war crimes," Shioya said. "We were lucky to find a distributor willing to show the film because for many Japanese, this was a shocking motion picture."

Unlike 'Prisoners of the Sun,' Jolie's 'Unbroken' is yet to be released in Japan. And while some Japanese may decry the film's portrayal of Japanese cruel treatment of Allied POW's, it is impossible to argue with the facts.

U.S. Department of Defense figures show that almost 40 per cent of all Americans taken prisoner by the Japanese died in captivity while just 1 per cent of American POWs died in Germany prisoner of war camps.

But unlike Germany, Japan's wartime iniquities have gone largely unpunished. There have been no Simon Wiesenthals to hunt down Japanese war criminals, and only a relative handful of Japanese military leaders were put on trial for atrocities.

As a result, generations of Japanese have grown up with only the sketchiest knowledge that Japan may have done something wrong in the 1930s and 1940s and that the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki were considered by many to be justifiable retribution.

Anti-Japanese feeling still exists in places like China and Korea where the heavy boot of Imperial Japan was most in evidence. In 1990, during a visit to Japan, then South Korean President Roh Tae Woo received an apology for Japan's 35-year occupation of the Korean peninsula from Emperor Akihito, the prime minister and parliament. But for many Koreans, none of the apologies went far enough.

"Human beings tend to be sensitive to and vividly remember their own sufferings," said Takashi Koshida, author of a two-volume work about the Japanese army's activities in 16 Asian nations during the war.

Zamperini when liberated from Japanese POW camp"In the case of the Japanese, the sufferings were the atomic bombings, the air raids and the military conscription. I would say it has taken almost 60 years for the Japanese to realize that they were aggressors . . . and that they caused other people to suffer."

Zamperini when liberated from Japanese POW camp"In the case of the Japanese, the sufferings were the atomic bombings, the air raids and the military conscription. I would say it has taken almost 60 years for the Japanese to realize that they were aggressors . . . and that they caused other people to suffer."One group of Japanese for whom 'Prisoners of the Sun'has particular significance is the Ambon Remembrance Society, an organization of 100 Navy veterans who served as guards in the POW camp.

"After I watched this film the first time I felt as though I had swallowed lead. . . . I felt very heavy and dark inside," said Yoshiro Ninomiya, a former Navy sub-lieutenant assigned to the camp.Ninomiya, who is the society's secretary-general, has seen "Blood Oath" five times, and he said, "It has made me think about a lot of things (that happened on Ambon)."

Shioya has spent long hours talking with former Japanese soldiers who served at the camp.

"One man still has nightmares about what he did on the island," Shioya said. "This man, who served a 15-year prison sentence after the war, told me of how one day in 1943 he was ordered to decapitate three captured American pilots with his sword.

"As his sword passed through the neck of one pilot, photographs of the man's mother, his wife and a baby fell out of his shirt pocket and lay on the ground staring up at him. "He is still haunted by that scene today."

Check out these links for a trailer on Prisoners of the Sun and a synopsis by imdb.

http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0100414/

http://www.imdb.com/video/imdb/vi3165585689/

Published on December 24, 2014 11:44

December 18, 2014

A Little Advice for New Authors

Fellow author Amy Neftzger recently wrote a column for a writer's group that I belong to called BookDaily in which she provided some good advice for novice writers.

Amy is an author of fiction for both adults and children and you can find out more about her and her work at her website: http://www.amyneftzger.com.

I thought I would share her prescient thoughts with you so I am turning my blog over to her for today. Amy Neftzger

Amy Neftzger

Starting Out As a Writer: 5 Things You Should Know By Amy Neftzger

Becoming an author is a long road to walk, and most people have no idea how long it takes to become successful or what they need to do when traveling this road. There are a lot of different ways to get to the end of it, but here are a few suggestions I have to help you along on this journey.

1. Success is not immediate

Many people think that publishing a book is like winning the lottery: you just put the book up for sale and then watch the royalties roll in. The truth is that simply putting your work out there will not make it sell. Readers have too many choices, and when they want a new book they tend to stick with what they know: authors they’ve already read. It takes quite a bit of time to build a following, so patience is the name of the game here. This is true whether you’re self or traditionally published.

2. In order to do it well, you will need help.

Don’t assume that you can write, edit, design layout, format, create cover artwork, and market your book all on your own. If you’re with a traditional publisher they will help with most of these things. If you’re self-published, you’ll need to find a way to get all these things done. You may be multi-talented but you’re still only one person and you may even have another job that currently pays your bills. So there’s the time factor to consider: If you do everything yourself then you’re spending a lot of time doing things other than writing. Aside from the time, when you do everything yourself your work tends to lack the balance that other people can add. Your finances may be limited, so figure out what you’re better at and where you’re weaker and seek affordable help for your weaker areas.

3. The market is currently flooded.

There are a lot of books out there and the number is growing, so readers have a lot of choices. What this means is that your book needs to be the best it can possibly be, because a less polished work simply won’t get any traction in a flooded market. This means that you may want to consider using beta readers to get feedback, and if you’re self-published you should definitely hire an editor and maybe even a proofreader.

4. Reader experience is everything.

People read books for the experience it provides. Your book should be designed to provide it and avoid anything that detracts from it.Things that pull away from the experience are glitches in plot development, spelling or layout errors, and errors in logic. maintaining a logical and believable flow to the plot will enhance reader experience, so use a good outline and be sure that the characters and situations are believable (even in fantasy).

5. It’s worth the effort

If you love to write and it’s in your blood, then you’ll find that all the work you put into producing your book is worth your time. The key is to keep working and improving your craft and to grow as a writer.

About the Author:

Amy Neftzger is the author of fiction books for both adults and children. She has also been published in business and academic journals, as well as literary publications. A few of her favorite things include traveling, books, movies, art, the Oxford comma, and gargoyles.

Amy is an author of fiction for both adults and children and you can find out more about her and her work at her website: http://www.amyneftzger.com.

I thought I would share her prescient thoughts with you so I am turning my blog over to her for today.

Amy Neftzger

Amy Neftzger

Starting Out As a Writer: 5 Things You Should Know By Amy Neftzger

Becoming an author is a long road to walk, and most people have no idea how long it takes to become successful or what they need to do when traveling this road. There are a lot of different ways to get to the end of it, but here are a few suggestions I have to help you along on this journey.

1. Success is not immediate

Many people think that publishing a book is like winning the lottery: you just put the book up for sale and then watch the royalties roll in. The truth is that simply putting your work out there will not make it sell. Readers have too many choices, and when they want a new book they tend to stick with what they know: authors they’ve already read. It takes quite a bit of time to build a following, so patience is the name of the game here. This is true whether you’re self or traditionally published.

2. In order to do it well, you will need help.

Don’t assume that you can write, edit, design layout, format, create cover artwork, and market your book all on your own. If you’re with a traditional publisher they will help with most of these things. If you’re self-published, you’ll need to find a way to get all these things done. You may be multi-talented but you’re still only one person and you may even have another job that currently pays your bills. So there’s the time factor to consider: If you do everything yourself then you’re spending a lot of time doing things other than writing. Aside from the time, when you do everything yourself your work tends to lack the balance that other people can add. Your finances may be limited, so figure out what you’re better at and where you’re weaker and seek affordable help for your weaker areas.

3. The market is currently flooded.

There are a lot of books out there and the number is growing, so readers have a lot of choices. What this means is that your book needs to be the best it can possibly be, because a less polished work simply won’t get any traction in a flooded market. This means that you may want to consider using beta readers to get feedback, and if you’re self-published you should definitely hire an editor and maybe even a proofreader.

4. Reader experience is everything.

People read books for the experience it provides. Your book should be designed to provide it and avoid anything that detracts from it.Things that pull away from the experience are glitches in plot development, spelling or layout errors, and errors in logic. maintaining a logical and believable flow to the plot will enhance reader experience, so use a good outline and be sure that the characters and situations are believable (even in fantasy).

5. It’s worth the effort

If you love to write and it’s in your blood, then you’ll find that all the work you put into producing your book is worth your time. The key is to keep working and improving your craft and to grow as a writer.

About the Author:

Amy Neftzger is the author of fiction books for both adults and children. She has also been published in business and academic journals, as well as literary publications. A few of her favorite things include traveling, books, movies, art, the Oxford comma, and gargoyles.

Published on December 18, 2014 15:07

December 16, 2014

What is Happening to the News Media?

I hear that question all the time. I hear it mainly because my friends and relatives know I spent almost 30 years of my life in the news business--first as a general assignment reporter, then as a foreign correspondent, then as an editor.

Later I became a professor of journalism and dean of a journalism program at a major university where I spent a lot of time researching the media.

So I know the news business inside and out. I have worked in it, I have studied it and now, like a lot of other people, I wonder about its usefulness and value.

Several factors have combined to alter the media landscape from the one I entered right out of college in 1970 or so.

Some argue that new technologies have had a deleterious impact on the media. There is no doubt that the old business models that once worked for newspapers, television and radio have changed. Advertising revenues have plummeted and news organizations find themselves scrambling to stay financially afloat.

Add to that the fact that the Internet, the blogosphere, and social media have all united to create a new world of pseudo-journalists who are not held to the same standards of excellence that we "professionals" once were and the picture looks bleak.

Sadly, today's "professionals" often are not being held to that higher standard either. Witness the recent fallout over the Rolling Stone story on the bogus gang rape at the University of Virginia that is being walked back because not a single detail could be corroborated.

Or the kind of "personal" and "participatory" journalism that would have gotten me run out of the Chicago Tribune's newsroom back in the early 1970s. I can almost hear my old city editor yelling:

"You can't write this kind of opinionated crap here!"

Yet, "opinionated crap" is often what we read in newspapers today or see on TV news programs. I can recall discussions we used to have in news meetings about how to involve our readers more in the news gathering process--a noble idea, up to a point.

Today, those discussions have become reality because of The Internet, bloggers, social media, etc. The media are more interactive than ever. That's not always a bad thing, but it becomes toxic when news organizations confuse "crowdsourcing" with old fashioned news gathering.

Now we are bombarded with stupid, unscientific "polls" and inane commentary from readers and viewers. No wonder glib MIT Professor Jonathan Gruber says the American electorate is "stupid." It is difficult not to come to that conclusion when you read or listen to some of these comments.

News organizations need to be more than simple aggregators of information. They need to provide knowledgeable, unbiased context for an informed citizenry. Unfortunately, there is little impartial context and even fewer citizens who are adequately informed.

News is often nothing more than "infotainment." It is a prejudicial mix of imprecise information and imprudent stories geared to titillate, rather than inform.

I used to tell my students we needed more of what I call "spinach journalism?" What is spinach journalism? you ask.

It is journalism intended to inform and educate. In essence we are telling news consumers: "Here, read this, watch this, listen to this, it's GOOD FOR YOU!"

Newspapers especially were once the mirrors for the communities they served. They reflected the people and events, the good and the bad of their communities. Granted, the mirrors were not always free of distortion, but at least there were tough professional editors and producers who cracked the whip and kept reporters focused on facts rather than the fiction and opinion we too often see today.

Sadly, I fear there are far too few of those tough and demanding newsroom mentors around today and too many reporters who think the news is theirs to manipulate and mold to fit their worldview or political ideologies.

Along those lines, I am amazed at how far many journalists seem willing to go to protect a Washington administration that has been the most opaque, intrusive and hostile to press freedom than any in recent history.

It makes me wonder what happened to the traditional role of the press? That role is to act as the de-facto "fourth estate" of government. Journalists, I was always told, were to be the watchdogs of government, not its lapdogs.

As someone once said, journalists should "comfort the afflicted and afflict the comfortable."

That is happening less and less today. It is much easier to write stories that reflect one's own values than to get out of one's comfort zone and enter unfamiliar and even disagreeable territory in the search for truth.

Veracity is seldom found within the confines of our own narrow opinions. All we will find there is further reinforcement for what we already hold to be true.

So when people ask me what is happening to America's news media--once the strongest and freest in the world--I have only one answer:

"Where's the spinach?"

Later I became a professor of journalism and dean of a journalism program at a major university where I spent a lot of time researching the media.

So I know the news business inside and out. I have worked in it, I have studied it and now, like a lot of other people, I wonder about its usefulness and value.

Several factors have combined to alter the media landscape from the one I entered right out of college in 1970 or so.

Some argue that new technologies have had a deleterious impact on the media. There is no doubt that the old business models that once worked for newspapers, television and radio have changed. Advertising revenues have plummeted and news organizations find themselves scrambling to stay financially afloat.

Add to that the fact that the Internet, the blogosphere, and social media have all united to create a new world of pseudo-journalists who are not held to the same standards of excellence that we "professionals" once were and the picture looks bleak.

Sadly, today's "professionals" often are not being held to that higher standard either. Witness the recent fallout over the Rolling Stone story on the bogus gang rape at the University of Virginia that is being walked back because not a single detail could be corroborated.

Or the kind of "personal" and "participatory" journalism that would have gotten me run out of the Chicago Tribune's newsroom back in the early 1970s. I can almost hear my old city editor yelling:

"You can't write this kind of opinionated crap here!"

Yet, "opinionated crap" is often what we read in newspapers today or see on TV news programs. I can recall discussions we used to have in news meetings about how to involve our readers more in the news gathering process--a noble idea, up to a point.

Today, those discussions have become reality because of The Internet, bloggers, social media, etc. The media are more interactive than ever. That's not always a bad thing, but it becomes toxic when news organizations confuse "crowdsourcing" with old fashioned news gathering.

Now we are bombarded with stupid, unscientific "polls" and inane commentary from readers and viewers. No wonder glib MIT Professor Jonathan Gruber says the American electorate is "stupid." It is difficult not to come to that conclusion when you read or listen to some of these comments.

News organizations need to be more than simple aggregators of information. They need to provide knowledgeable, unbiased context for an informed citizenry. Unfortunately, there is little impartial context and even fewer citizens who are adequately informed.

News is often nothing more than "infotainment." It is a prejudicial mix of imprecise information and imprudent stories geared to titillate, rather than inform.

I used to tell my students we needed more of what I call "spinach journalism?" What is spinach journalism? you ask.

It is journalism intended to inform and educate. In essence we are telling news consumers: "Here, read this, watch this, listen to this, it's GOOD FOR YOU!"

Newspapers especially were once the mirrors for the communities they served. They reflected the people and events, the good and the bad of their communities. Granted, the mirrors were not always free of distortion, but at least there were tough professional editors and producers who cracked the whip and kept reporters focused on facts rather than the fiction and opinion we too often see today.

Sadly, I fear there are far too few of those tough and demanding newsroom mentors around today and too many reporters who think the news is theirs to manipulate and mold to fit their worldview or political ideologies.

Along those lines, I am amazed at how far many journalists seem willing to go to protect a Washington administration that has been the most opaque, intrusive and hostile to press freedom than any in recent history.

It makes me wonder what happened to the traditional role of the press? That role is to act as the de-facto "fourth estate" of government. Journalists, I was always told, were to be the watchdogs of government, not its lapdogs.

As someone once said, journalists should "comfort the afflicted and afflict the comfortable."

That is happening less and less today. It is much easier to write stories that reflect one's own values than to get out of one's comfort zone and enter unfamiliar and even disagreeable territory in the search for truth.

Veracity is seldom found within the confines of our own narrow opinions. All we will find there is further reinforcement for what we already hold to be true.

So when people ask me what is happening to America's news media--once the strongest and freest in the world--I have only one answer:

"Where's the spinach?"

Published on December 16, 2014 14:19

December 8, 2014

Do America's Enemies Deserve Our Respect and Empathy?

In a recent speech at Georgetown University Hillary Clinton urged Americans to empathize with and respect our enemies--namely Islamic fanatics who want to kill us and obliterate our way of life.

After those words were uttered by a woman who apparently wants to be America's next president, I think I heard Gen. George S. Patton bellowing epithets from the grave. Patton was notorious for his epithets.

Patton, the no nonsense American general known as "blood and guts" who helped push the Germans out of North Africa and Sicily during WW II and who drove the U.S. Third Army deep into the heart of Germany, said this about America's enemies:

“May God have mercy on my enemies because I won't.”

That's poles apart from what Hillary Clinton had to say last week about America's enemies and how we should deal with them: "Show Respect for America's Enemies"

"Show Respect for America's Enemies"

"This is what we call smart power...showing respect, even for one’s enemies, trying to understand and insofar as psychologically possible empathize with their perspective and point of view."

I can just imagine what Patton would say about "smart power" and the preposterous notion that we should have respect for and empathize with our enemy's point of view.

He no doubt would have used one of his favorite words: Bullshit!

I wonder how Hillary's statement might have resonated if she had made it during WW II after the world learned what the Nazi's did in death camps like Auschwitz and what the Japanese did in places like Nanking, China?

Oh, but the war against radical Islam is different, some might argue. Really? You mean beheading journalists, slaughtering innocent aide workers and educators, murdering Christians and Jews, and even butchering Muslims who don't adhere to radical Islam is not the same? Really?

Murder is murder no matter who commits it, how it's committed, or in what decade it is committed. Empathy and respect be damned.

And what if President Roosevelt had gone to Congress seeking a declaration of war following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor and said:

"We must have empathy for the Japanese who did this to us," instead of what he actually said, which was: "Yesterday, Dec. 7, 1941 - a date which will live in infamy - the United States of America was suddenly and deliberately attacked by naval and air forces of the Empire of Japan."

Enemies are enemies. Empathizing and respecting their perspective is a ludicrous thing to say. It is especially preposterous for someone who wants to occupy the White House and become our military's Commander-in-Chief.

Patton understood that the way to win a war was to fight it, not chatter about it while giving a $200,000 speech. The last thing he would have counseled is for American leaders to engage in fearful hand wringing and hope those who want to destroy us will somehow come to love us if only we are benign, compassionate and work harder to understand their perspective.

General "Blood & Guts" Patton

General "Blood & Guts" Patton

In a 1944 speech to the Third Army Patton told his men this: "We want this war over with. The quickest way to get it over with is to go get the bastards who started it. The quicker they are whipped, the quicker we can go home."

Is there any doubt who started the war on terror? On September 11, 2001 when those hijacked planes flew into the twin towers, into the Pentagon, and into that Pennsylvania farm field, we were at war--even if the current feckless occupant of the White House refuses to call it that.

When you are attacked, no matter what your political affiliation may be or on which side of the political aisle you may sit, you basically have two options: you either capitulate because you are afraid to fight, or you respond with "extreme prejudice," as we used to say in the Army.

Regrettably, the current administration seems to have resurrected a third option--one that was proven woefully ineffective back in 1938. It was called appeasement. And Adolph Hitler laughed all the way to the Eagle's Nest.

After Hillary Clinton's ill-advised and placatory remarks you can almost hear the terrorists hooting and whooping in their desert bunkers and strongholds.

I wonder how Patton might have dealt with the brutal Islamic State currently slaughtering its way through Syria and Iraq.

I can't imagine him telling the men of the Third Army to respect and empathize with that vicious rabble; to try to understand why they hate America or why these cowards are beheading American and other Western captives.

After Patton read the Koran and observed North African Muslims during WW II, we have an idea what he thought of Islam. In his book, War as I Knew it, published posthumously in 1947, he wrote:

"What if the Arabs had been Christians? To me it seems certain that the fatalistic teachings of Mohammed and the utter degradation of women is the outstanding cause for the arrested development of the Arab. He is exactly as he was around the year 700, while we have kept on developing."

Not a sentiment that would make the apologists for Islamic radicals and terrorists happy.

Nor would Islamic suicide bombers have embraced one of Patton's most famous statements:

"No bastard ever won a war by dying for his country. He won it by making the other dumb bastard die for his country."

Amen, General.

After those words were uttered by a woman who apparently wants to be America's next president, I think I heard Gen. George S. Patton bellowing epithets from the grave. Patton was notorious for his epithets.

Patton, the no nonsense American general known as "blood and guts" who helped push the Germans out of North Africa and Sicily during WW II and who drove the U.S. Third Army deep into the heart of Germany, said this about America's enemies:

“May God have mercy on my enemies because I won't.”

That's poles apart from what Hillary Clinton had to say last week about America's enemies and how we should deal with them:

"Show Respect for America's Enemies"

"Show Respect for America's Enemies""This is what we call smart power...showing respect, even for one’s enemies, trying to understand and insofar as psychologically possible empathize with their perspective and point of view."

I can just imagine what Patton would say about "smart power" and the preposterous notion that we should have respect for and empathize with our enemy's point of view.

He no doubt would have used one of his favorite words: Bullshit!

I wonder how Hillary's statement might have resonated if she had made it during WW II after the world learned what the Nazi's did in death camps like Auschwitz and what the Japanese did in places like Nanking, China?

Oh, but the war against radical Islam is different, some might argue. Really? You mean beheading journalists, slaughtering innocent aide workers and educators, murdering Christians and Jews, and even butchering Muslims who don't adhere to radical Islam is not the same? Really?

Murder is murder no matter who commits it, how it's committed, or in what decade it is committed. Empathy and respect be damned.

And what if President Roosevelt had gone to Congress seeking a declaration of war following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor and said:

"We must have empathy for the Japanese who did this to us," instead of what he actually said, which was: "Yesterday, Dec. 7, 1941 - a date which will live in infamy - the United States of America was suddenly and deliberately attacked by naval and air forces of the Empire of Japan."

Enemies are enemies. Empathizing and respecting their perspective is a ludicrous thing to say. It is especially preposterous for someone who wants to occupy the White House and become our military's Commander-in-Chief.

Patton understood that the way to win a war was to fight it, not chatter about it while giving a $200,000 speech. The last thing he would have counseled is for American leaders to engage in fearful hand wringing and hope those who want to destroy us will somehow come to love us if only we are benign, compassionate and work harder to understand their perspective.

General "Blood & Guts" Patton

General "Blood & Guts" PattonIn a 1944 speech to the Third Army Patton told his men this: "We want this war over with. The quickest way to get it over with is to go get the bastards who started it. The quicker they are whipped, the quicker we can go home."

Is there any doubt who started the war on terror? On September 11, 2001 when those hijacked planes flew into the twin towers, into the Pentagon, and into that Pennsylvania farm field, we were at war--even if the current feckless occupant of the White House refuses to call it that.

When you are attacked, no matter what your political affiliation may be or on which side of the political aisle you may sit, you basically have two options: you either capitulate because you are afraid to fight, or you respond with "extreme prejudice," as we used to say in the Army.

Regrettably, the current administration seems to have resurrected a third option--one that was proven woefully ineffective back in 1938. It was called appeasement. And Adolph Hitler laughed all the way to the Eagle's Nest.

After Hillary Clinton's ill-advised and placatory remarks you can almost hear the terrorists hooting and whooping in their desert bunkers and strongholds.

I wonder how Patton might have dealt with the brutal Islamic State currently slaughtering its way through Syria and Iraq.