Lory Widmer Hess's Blog, page 9

February 10, 2024

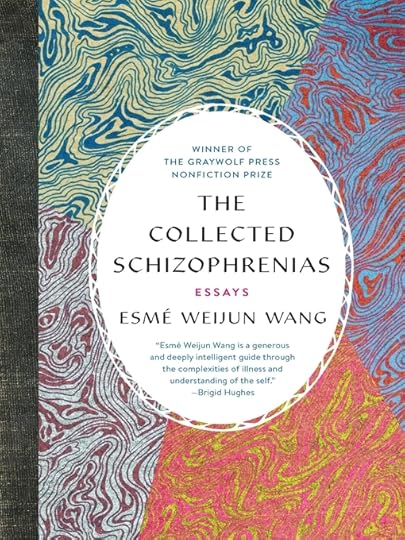

Nonfiction Reader Challenge: The Collected Schizophrenias

Ever since reading Hidden Valley Road (which I highly recommend), I’ve been wanting to read more about schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, to learn more about these mysterious and very challenging states of soul, from as many points of view as possible. I’ve put a number of titles on the TBR, to work through gradually.

The Collected Schizophrenias is a good way to gain a window into the experience of someone living with schizoaffective disorder, bipolar type — the diagnosis author Esmé Weijung Wang was eventually given. In the first essay of this collection, she acknowledges that any diagnosis is a human construct and this might change, but also movingly describes the reassurance it gives her just to have some kind of handle on a condition that by its very nature makes reality hard to grasp.

It also makes human relationships incredibly hard to sustain. In her epigraph, Wang quotes Sylvia Nasar: “More than any symptom, the defining characteristic of the illness is the profound feeling of incomprehensibility and inacessibility that sufferers provoke in other people.” (Emphasis mine.) The “schizophrenias” are not a single, easy to pinpoint deficiency, but a kaleidoscope of overlapping symptoms that disrupt the usual line between inner and outer worlds. In that process, they also disrupt the web of human connection that keeps us grounded in a common reality.

I wonder to what extent they are also caused by the disruption of this web, and how much the withdrawal of others through the “feeling of incomprehensibility” they provoke exacerbates the ailment. Wang doesn’t say much about this side of things, but it’s clear the support of her husband, C., has been a key factor in her being able to come to a place of tenuous stability, and that there remain issues with her parents that are too painful even to go into. Would Wang not even have been born, if her mother had been more willing to take responsibility for her own untreated mental illness? It’s hard to face life with the feeling you shouldn’t exist.

Another quote from Andrew Solomon describes the common understanding of schizophrenia as erasing a person and replacing them with someone or something else. Wang helps to challenge that image, as she presents herself to us as honestly as possible, including vivid accounts of what it’s like to start believing things she knows are not true. When someone becomes inaccessible to others through ordinary thought and language, are they really gone? Where do they go? It makes me think about how fragile each of our own images of the “real world” is, how dependent upon factors of which we know nothing. No doubt this is why it is so frightening when that thin line starts to be broken, and why we want to turn away and not look too hard.

Wang, though, unflinchingly brings to our attention the suffering caused by a mental health system that is not about health care in any ongoing sense, but about categorizing people and neutralizing immediate threats. The indignity of losing her autonomy and being involuntarily committed three times, not one of which helped her. The frightening ease with which lies become truth when transmitted by social media, preying on susceptible minds. “For those of us living with severe mental illness, the world is full of cages where we can be locked in,” Wang writes. It’s hard, but necessary, to look at those cages and consider what we are doing to other human beings in order to keep ourselves safe.

Even as her mind has sometimes been her enemy, it’s also been Wang’s greatest strength, and she displays her intelligence, research skills, and artistic gifts to their full extent here. At the same time, she fully acknowledges that “Yale will not save you,” as one of her chapter titles puts it. I also wonder to what extent our high-achieving society that overvalues the intellect and downplays emotional and relational skills contributes to the pain of mental illness. Certainly, institutions of higher education do a poor job of dealing with their mentally ill students — in Wang’s portrayal, their message is “we can’t deal with you, we take no responsibility, please leave.”

That’s a shameful message to be coming from the institutions we most respect, the ones that should be dedicated to exploring and upholding truth, and more is demanded of us if we are to recover our true humanity. As I keep reading more on the topic, I know I’ll remember The Collected Schizophrenias as a uniquely valuable, moving, and confronting piece of work, a voice speaking up for a population that is too often reduced to silence and “incomprehensibility”.

Esmé Weijun Wang, The Collected Schizophrenias (Graywolf, 2019).

Graywolf Press is an independent, nonprofit publisher founded in Port Townsend, Washington, now located in Minneapolis. Visit the #ReadIndies post at Kaggsy’s Bookish Ramblings for more celebration of independent publishers.

I counted this book for the Health category of the Nonfiction Reader Challenge.

February 6, 2024

Recent publications

A few pieces that I submitted some time ago have come out recently. I am happy to link them up here and incidentally to inform you about some fine online journals.

“Weaving Lessons” was featured at bioStories, which posts an essay each week on Wednesdays. Check out their complete archives for a multitude of stories that “share the extraordinary in ordinary lives.”Vita Poetica published “Listening to Our Pain,” thoughts inspired by the essay collection Nervous by Jen Soriano. The Winter 2024 issue also features poetry, fiction, nonfiction, visual art, an interview, and contemplative practices.My poem “we cover up the roots,” was served up at Poetry Breakfast. Subscribe and every weekday morning, you can get a new poem in your blog reader or inbox.I hope you’ll enjoy these!

February 4, 2024

Month in Review: January 2024

The first book I finished in 2024 was, appropriately enough, a book about books — more precisely the odd and idiosyncratic vocation of selling rare and collectible books, via a venerable London shop.

I am not one for collecting physical books at the moment, but in recent years I have been enjoying reading through authors and series, piling them up on my virtual shelf. I said goodbye to the LoveHain readalong this month; meanwhile, the Ozathon continues! It’s lovely to see a number of blogging friends joining in. I also read a spin-off novel which provided an interesting take on the story of both movie and book from the point of view of Maud Baum, a fascinating women who deserves more attention.

Another project I’m starting this year is the Nonfiction Reader Challenge, which I hope will push me to read more nonfiction on different topics. For my first topic I took on one that I find scary — The Future — and found myself both challenged and reassured. I know there are no easy answers to what lies ahead, but as long as there are books, I have hope that I can learn something worthwhile, possibly even essential.

What did you learn and discover this month?

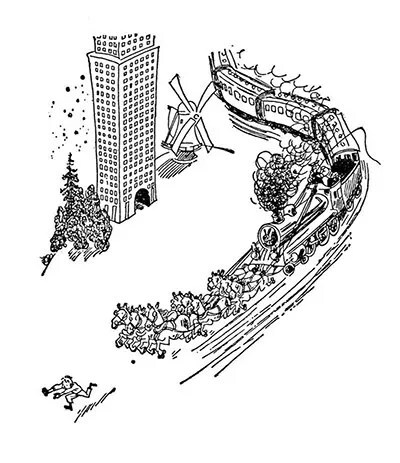

Books read in January Once Upon a Tome by Oliver Darkshire Measuring the World by Daniel Kehlmann The Marvelous Land of Oz by L. Frank Baum The Twelve Lives of Alfred Hitchcock by Edward White Skating Shoes by Noel Streatfeild – Reread Life After Doom by Brian McLaren – Nonfiction Reader Challenge Finding Dorothy by Elizabeth Letts Ozma of Oz by L. Frank Baum In an article in the Guardian about writers’ and artists’ favorite classic book illustrations, Michael Rosen picks this illustration by Walter Trier from Emil und die Detektive, for its “wide space” and “speed”.Language

In an article in the Guardian about writers’ and artists’ favorite classic book illustrations, Michael Rosen picks this illustration by Walter Trier from Emil und die Detektive, for its “wide space” and “speed”.LanguageAs I continue to try to read books in German, I dropped The Wall (which was very slow going) and picked up Emil und die Detektive (more my speed at present). Soon I may be ready to take on some adult novels, but for now I’m happy with the classic children’s books.

Coincidentally, a new English student turned out to be a fan of the Oz books, and was impressed to hear I’ve also read the whole series. It seems that’s quite unusual, although it feels very normal to me. My student has only read the books in Chinese translation, so I’ve encouraged her to try the original. I’m looking forward to sharing these with her.

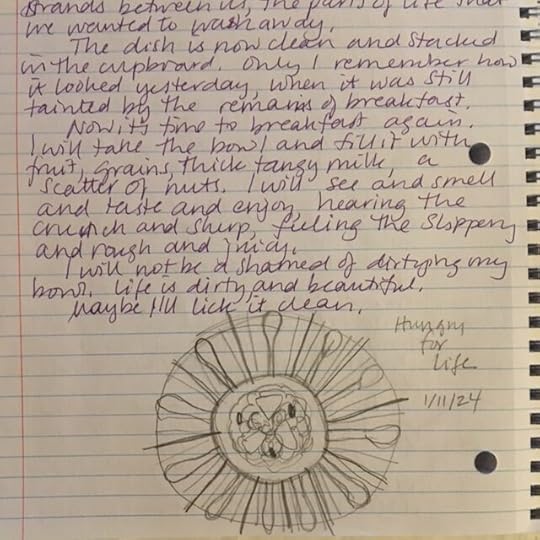

Page from a journaling exercise — the task was to draw a mandala inspired by the journal.Life

Page from a journaling exercise — the task was to draw a mandala inspired by the journal.LifeOn the blog, I looked back at 10 years of blogging, picking out one post from each year. It truly has been a wonderful journey and I’m so thankful for it.

Looking toward the future, my Spiritual Direction training has started up again, this year with actual practice sessions … an exciting and humbling new step into the ministry of sacred conversation. My book, When Fragments Make a Whole, will be published soon, and that is also very exciting, of course.

Writing more and submitting more for publication is a goal of mine this year. I’ve started meeting with another writer for some inspiration and support, working through exercises in the book One Year To a Writing Life by Susan Tiberghien. You can see a sample above.

Please share what’s going on with you!

Linked at The Sunday Post at Caffeinated Book Reviewer, the Sunday Salon at Readerbuzz, and the Monthly Wrap-up Round-up at Feed Your Fiction Addiction

February 1, 2024

#Ozathon24: Ozma of Oz

With the third book of the Oz series, we have the return of Dorothy and her meeting with the newly discovered ruler of Oz, along with a plethora of new characters including a feisty chicken, a mechanical man, and the underground Nomes. With its blend of excitement, humor, and suspense, it’s one of the best-constructed and most narratively satisfying of the series, in my opinion.

Will you agree? If you’re reading along, come back at the end of the month for the wrap-up post. Be sure to share your thoughts and links to any of your own posts.

Check out this post from Hungry Tiger Press for a survey of how Ozma was drawn over the course of the series — with plenty of Ozzy inconsistencies, of course.

January 28, 2024

#Ozathon24: A Land of Life

For this month’s Ozathon posts, be sure to visit The Book Stop, where Deb will be hosting the wrap-up.

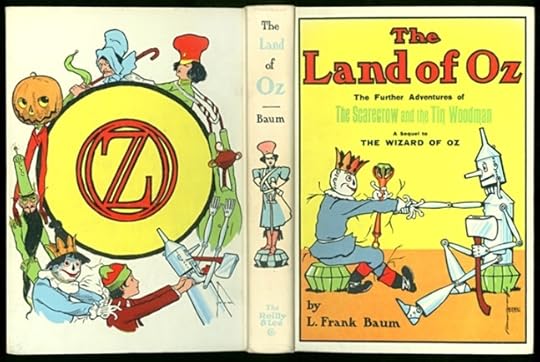

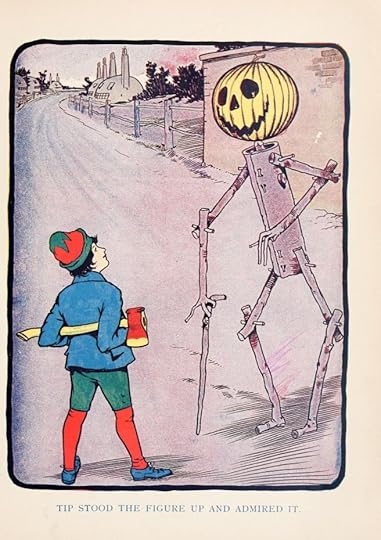

The Marvelous Land of Oz was L. Frank Baum’s follow-up to his breakout success, The Wonderful Wizard of Oz. As a child, I was always a bit puzzled by how different Book 2 was from Book 1. Dorothy does not appear, the Cowardly Lion also plays no role, while the Scarecrow and Tin Man get much more attention. The central character is a boy named Tip, who brings a number of other comical characters to life with a magic powder, and undergoes a surprising transformation himself. The overall tone has changed from ironic fairy tale to slapstick comedy, with another new character, the Wogglebug, supplying verbal humor with his terrible puns. An army of pretty girls who want to take over the Emerald City is another new element.

I didn’t object to the difference because I enjoyed the humor and adventure. The scene where the Scarecrow and Tip’s creation Jack Pumpkinhead decide they can’t understand each other and need an interpreter, even though they’re speaking the same language, always makes me laugh out loud. (How often I’ve found myself in that situation!) But I had no idea of the context in which the book arose. I didn’t know the girl army was a parody of the suffragettes then agitating for votes for women. Nor was I aware that during the four years between the two books, a hit musical had been produced based on Wizard in which the actors playing the Scarecrow and Tin Man were the big stars. Baum, whose true love was the stage, was trying to reproduce the success of this show in the sequel.

From the musical came the “lost ruler of Oz” idea that also becomes a new element in this book; the first time around we heard nothing about the Wizard wrongfully taking over the throne and abducting a child. But that becomes the main quest here, to discover the true ruler of the land and put her back on her throne.

Her? Yes, the ruler of Oz, it transpires, is a girl. Not the girl army, who prove themselves to be vain and petty and cruel. This might be interpreted as criticism of the suffragette cause, but as Baum was a supporter of women’s suffrage himself and married to the daughter of one of the major feminist activists of the era, I think his parody was directed at the idea of suffragettes in the popular imagination. It also simply gave him a way to work in a large chorus of beautiful women, which would be useful if this book became a musical, too. The transformation scene at the end was also a common feature in drama of the time.

Those who critique Baum’s “anti-feminism” have to take into account that the girl army is overcome not by an army of men, but by another army of women, led by the powerful sorceress Glinda the Good. The opposition is not between male and female, but between the forces of unbridled self-interest and the forces of disciplined loyalty to a higher wisdom. Traditional “women’s work” is also valued as more difficult than men’s, as when men have to take it on they quickly become exhausted. And the Wogglebug remarks that girls are as intelligent and fit for education as boys, which was not at all the prevailing notion in Baum’s day. All of this had changed so much by the time the book reached me, that it passed me by.

But now I can better appreciate how unusual Baum’s centering of female power was. As the series continued and grew in popularity, I wonder how many of us were influenced by his images of women as wise and powerful, adventurous and brave. His imagined world of Oz might have helped in changing the real world, in unexpected, underground ways.

Male characters also play an important role, but the values they embody are often also different from those of the usual masculine culture. In this book, for example, Tip creates a wooden figure with a jack-o-lantern head to scare his cruel foster mother, the witch Mombi. Although it is Mombi who animates Jack Pumpkinhead with a magic powder, he hails Tip as his parent; Tip has given him birth, in effect.

Giving life to inanimate objects is a recurring motif in the series. In the first book, the Scarecrow came to life with no explanation, becoming conscious of his own creation as a farmer made him. Perhaps the land of Oz itself sometimes lends its magic forces to some of its inhabitants. The Tin Man, in an opposite process, was once a living human whose parts were gradually replaced with metal, but retained life and consciousness.

Tip steals the magic powder from Mombi and uses it to animate two more creatures: besides Jack, a Sawhorse is brought to life as a steed for Jack, along with the Gump, a strange conglomerate born of the necessity to escape from the girls who have taken over the Emerald City, usurping the Scarecrow’s throne (he was appointed by the Wizard to replace him in the first book). All three were originally made for the use of humans, but take on a life of their own beyond that usefulness, and eventually have to be considered as people in their own right.

The Sawhorse is a willing steed, but requires those who make use of him to be mindful of their words; for example, if they tell him to “go” he’ll run until he falls into a river, not having been told to stop. Meanwhile, when the Gump’s purpose is finished he wants to be taken apart again, and his request is honored. His head once belonged to a noble animal in the forest, and he feels humiliated by being attached to an assortment of household objects. That head retains the ability to observe and speak, though, and sometimes startles visitors; once life has begun, you have to take the consequences.

The theme of sentient beings deserving autonomy and self-determination is another one that will develop through the series, though it’s not quite mature yet in this one. I was sometimes taken aback by how impatient and dismissive the other characters were of Jack, whose guileless remarks are derided as stupid, even by his “father,” Tip. He is often taunted with the fact that his head will spoil and his life will come to a rotten end, something that will change later in the series when Baum decides to confer immortality on Oz. In this book, though, morbid humor abounds, perhaps also intended for the stage.

Oz was not a coherent creation, and the early books are particularly full of inconsistencies, but for readers who love them, their imaginative energy makes up for a multitude of literary sins. Gore Vidal, who was reportedly rereading The Wizard of Oz for the umpteenth time when he died, encapsulated their appeal when he wrote in a 1977 New York Review article that they have the potential to make readers “imaginative, tolerant, alert to wonders, life.”

In a world subject to increasing mechanization, I still look for the ways that anything, even dead wood and metal, can come to life, and I’m sure that quest can be traced back to my hours spent in the Land of Oz.

January 21, 2024

Nonfiction Reader Challenge: Life After Doom

I’ve joined the Nonfiction Reader Challenge hosted by Book’d Out, and with my very first read I decided to take on the scariest topic: The Future!

Brian McLaren pulls no punches with the title of his forthcoming book, Life After Doom. The topic may be alarming — the coming environmental collapse, which could take a variety of forms, none of them pleasant — but rather than staying at a safe distance while laying down the uncomfortable truth, McLaren composes his book as if it’s a conversation with the reader. There is plenty of objective information and science, with abundant footnotes, but McLaren also shares his own thoughts and feelings and experiences, his fears and dreams, even a letter he wrote his grandchildren. He doesn’t claim to have all the answers, and he looks with compassion and curiosity at the strange ways human beings shield themselves from the truth. After each short chapter, he adds questions for individuals or groups to engage with, as we struggle to face uncertainty.

The basic message is that to get through whatever is coming — and nobody can say exactly what that is, except that it’s the end of the world as we know it — we have to turn towards each other and support one another. People who hole up in survival bunkers and pick off the others with guns will end up in a lonely, aggressive world. Is that the world you want? Or could you imagine a different future, one where you even went to your death while putting love and care for others above everything else? A foolish idea, one might say, but we haven’t done so well with conventional wisdom. Maybe it’s time to try being foolish.

What is happening now on an outer level is a revelation of our long-standing inner orientation toward the exploitation of others for personal gain. This is the worship of the God of progress, in what McLaren identifies as an unholy modern alliance of capitalism and religion. It’s an aberration of religion, really, warped to turn humanity’s striving toward knowledge of its own eternal nature into a short-sighted, selfish quest for survival through accumulating and hoarding resources. Perhaps we can imagine a different deity, a different ideal — the ideal of evolution. How can we participate consciously in our own evolution? That is our challenge today, and it’s an immense gift as well as a sobering responsibility.

McLaren has some sobering words to say about hope: people want and need hope, but when hope puts them off from taking action, it can be self-defeating. (This section reminded me of a verse by Rudolf Steiner which speaks of “the wings that have long been lamed by hope.”) Hoping that someone else will fix what we are responsible for puts us in the power of forces inimical to humanity. The hope we need is not a wishing for a better future we don’t have to work for, but a hands-on knowledge of the indomitable strength in the human spirit. That comes only through working together in community, and McLaren’s suggestion for inspiring a better kind of hope is to start working with others. Even two or three at a time, we can make a difference.

I suspect that any reader will find things in this book to disagree with. I disagree with some of McLaren’s fundamental premises, above all the notion that maybe after all the Earth would be better off without us, and we should come to peace with that possibility. He lyrically imagines the beauty that would remain if we were gone, but who would be there to see that beauty? There is no beauty on Earth without the human souls in which it comes to life. The Earth would be an empty, dead shell without us.

That’s why we must do our utmost to come through the coming challenges, holding fast to the human mission, which is resurrection from death. To live our lives in a way that gives life to others and to the Earth as a whole is our task, not infinite personal survival. As we face our doom, we might also find out who we really are. And that is a hope worth having, in my view.

Though I do still feel scared about the future, I also feel more energized and prepared, and motivated to make the connections which will help to carry us through to the other side of doom. So this was a good read to start the challenge, and the year. What next? I’m looking forward to learning more, as I venture into more nonfiction categories and check out the posts of others.

Brian McLaren, Life After Doom: Wisdom and Courage for World Falling Apart (St Martin’s Press, May, 2024).

January 16, 2024

Celebrating 10 Years of Blogging

I forgot to celebrate the occasion, but the 1st of January marked 10 years since I started my first book blog, The Emerald City Book Review. Though the Emerald City has morphed into the Enchanted Castle, I’ve been blogging for a whole decade now.

I’ve gotten so much out of this hobby, and I am so grateful to all my readers and fellow bloggers. Some have been with me almost since the beginning, some have joined along the way, and some have sadly fallen out of touch. But I appreciate each and every interaction that I have through this medium, and I hope that you have found it valuable as well.

I’m picking out some highlights from those 10 years, for a trip down memory lane. This was more or less at random, as I did not have time to go through hundreds of posts! I hope you might find something here to interest you, and perhaps sample a few more of my musings from the past.

2014: I compiled a list of Ten Books You Might Not Have Heard Of. 2015: I made a literary pilgrimage to Emily Dickinson’s House .2016: I looked back at the Reading New England Challenge .2017: I asked, What are your favorite Arthurian books? 2018: I read Les Misérables in a chapter a day.2019: I reflected on the Apocalypse: It’s not the end of the world .2020: I posted a pandemic list of Fourteen books about freedom .2021: I shared photos from a trip to Ticino .2022: I wrestled with my health in Uncovering my eating disorder .2023: I kicked off the Ozathon with Journey into the heart .In the comments, post a link to a past highlight on your own blog, and I’ll check it out! Every chance to connect with one another is worth celebrating.

Photo by Ylanite Koppens on Pexels.com

Photo by Ylanite Koppens on Pexels.com

January 13, 2024

#LoveHain: A Human Universe

Even though I own the Library of America edition of the Hainish novels and stories by Ursula K. Le Guin, I’d not read most of the contents, or had extremely hazy recollections. So when Chris of Calmgrove organized a readalong, I was all for it. Over the course of 2023 I read several novellas and a multitude of short stories — I skipped The Left Hand of Darkness and The Dispossessed, which were fresher in my memory — roughly in the order that Le Guin published them.

It’s not a planned, organized, or internally consistent sequence, but a rough collection of worlds and scenarios based on the premise that people from a world named Hain colonized other planets (including our own) many ages ago, and now, having matured past the point of younger societies, occupy themselves with studying and learning about those other worlds, and fostering a coalition called the Ekumen.

As I look back over the whole sequence, I found it interesting that the earliest stories, published in the 60s, are preoccupied with dread at the expected invasion of an external enemy — reflecting Cold War concerns. By the later stories, the focus turns to slavery and authoritarian rule perpetrated not by a vague extra-galactic threat, but by people against their own neighbors and kin. 25 years after the last story was published, that theme is still very timely.

Against this background of cruelty and injustice, the notion that there could be people who might actually find their fundamental life purpose not in killing and enslaving, but merely observing and learning, shines as a constant beacon of hope, which grows only stronger with time. And yet there is great pain in that role, too, as they are not supposed to interfere in the society they observe. The benefits of joining the Ekumen are meant to discourage the evils of violence, but it’s a slow process. When a civilization has lasted for many thousands of years, though, there is time to learn patience.

Photo by Pixabay on Pexels.com

Photo by Pixabay on Pexels.comOur world, Terra, has not done so well in its learning, ravaged by environmental disaster in an imagined future that now seems around the corner in real life. With a track record of violence and exploitation, it presents a bleak picture, aside from the Terrans who become active in the Ekumen and seek a more peaceful existence.

But there is still that notion that given enough time, enough painful learning, and enough commitment to working together, people can grow into their truest human potential. We can delight in diversity and difference, wondering at the strange and marvelous ways that living creatures adapt to their environment. We can cooperate instead of fighting, share our strengths instead of attacking one other out of fear of our own weakness.

Many of the stories are preoccupied with relativity, with the disjunction between our experience of time and our experience of space. People who leave their home planet to study or work with the Ekumen, for example, know they will never see their loved ones again; by the time they returned, those left behind would be long gone. Going into space is, in many ways, tantamount to entering the realm of death, and the stories often wrestle with the grief of losing our ties to one another.

Photo by Hristo Fidanov on Pexels.com

Photo by Hristo Fidanov on Pexels.comThey also offer many examples of reconnection. I keep thinking about one particular story, called “The Shobies’ Story.” This is about a spaceship crew, drawn from a number of different worlds including Hain and Terra, who have volunteered to explore an intriguing but possibly dangerous new technology. While instantaneous communication has long been possible (via Le Guin’s invented device, the “ansible”), they are going to attempt instantaneous transportation of their ship and its contents to another planet, using the same principles. It’s not known how this will affect sentient beings.

The group is diverse and in some ways ill-assorted. They spend time together ahead of the mission, to strengthen their bond so that they’ll be able to support one another, but that falls apart after they make the transfer and find that they are each experiencing completely different things. They can’t rely on common sensory perceptions, because their sense of all outer happenings has diverged and left each one in a separate universe. The ship won’t even move, can’t get them back to home base while they are in this fractured state.

What do they do? They tell a story. Each one, in turn, tells what he or she has experienced, and the others listen. They don’t rebel against the others’ differences, don’t argue or contradict, but accept each piece, silently weaving them into a common understanding of what has happened to their group. And the ship begins to move.

Le Guin herself was a storyteller who was also a warrior for peace and justice. Sometimes her tales are overly didactic in their urgency, their alarm at the rate at which we are destroying ourselves and our planet, but at their best they present us with living pictures that help to re-orient our imaginations toward the truth. Ranging out into worlds that never were and bringing to life people who never will be, they remind us of who we really are.

I have not yet read all the Hainish stories yet; I’m saving four that were collected in The Birthday of the World (link is to Chris’s review) for another time. When I do, I expect to be taken on another marvelous journey, and to learn more about the possibility of a more human future.

Photo by brenoanp on Pexels.com

Photo by brenoanp on Pexels.com

January 7, 2024

Month in Review: December 2023

I’ve already been reviewing my entire year’s reading this week (see fiction; nonfiction, but here’s what I read in December, 2023. I ended the year with quite a lot of good reading — aided by being on vacation for the last 10 days.

A dramatic shot of the Faroes — when not raining it must be spectacular.

A dramatic shot of the Faroes — when not raining it must be spectacular.Along with joining in some challenges and events and I did a bit of searching in the library catalog to come up with something quite random. This resulted in my reading Far Afield, by Susanna Kaysen — better known as the author of Girl, Interrupted and Cambridge. Here she was departing from autobiography to portray a young male anthropology student who spends a year in the Faroe Islands. The protagonist was emotionally clueless, but his growth through encounter with the remote Faroes and its people was fascinating.

My attempt to find something completely different also resulted in reading How To Catch a Mole, which ended up being one of my favorite books of the year. With a unique combination of nature writing, memoir, and poetry, I learned a great deal about two strange creatures, moles and human beings.

What did you discover in December?

Books read in December:

Healing Your Family History by Rebecca Linder Hintze Discernment by Rose Mary Doughterty Life After Life by Raymond Moody Inheritance by Dani Shapiro – Reread The Fair Miss Fortune by D.E. Stevenson – Dean Street December Five Ways to Forgiveness by Ursula K. Le Guin – LoveHain Far Afield by Susanna Kaysen Heart: A History by Sandeep JauharThe Wonderful Wizard of Oz by L. Frank Baum – Ozathon Miss Mole by E.H. Young – Dean Street December Sacred Conversation by Marsha Crockett How to Catch a Mole by Mark Hamer Everything Is Fine by Vince Granata The Life and Adventures of Santa Claus by L. Frank BaumLanguageDuring my winter vacation, I decided to try to find some more students on italki. Among others, I connected with a student who wants to read classic literature, which is great! We’ll start with some stories by Edgar Allan Poe, and I’m looking forward to that.

In my own language learning, I continue to slowly read Die Wand (The Wall), but I’m not that motivated because it’s a rather depressing story. I’ve gotten about a quarter of the way through, and I should have made good headway while I had time off, but instead I defaulted to reading in English.

Should I keep on with a book I don’t fully enjoy? Or set it aside and try something else?

Hitting a wall in my German reading…

Hitting a wall in my German reading…Photo by Pixabay on Pexels.comLife

I had a number of writing-related posts in December:

My book: When Fragments Make a Whole Two poems: Announcement and Labyrinth An article at Authors Publish: Is an unpublishable book worth writing?December felt very busy and hectic as Christmas approached. I didn’t feel ready for the holiday at all — my husband received two balls of wool from me, with which I’ve promised to knit him a present. Hopefully before next Christmas. But I’ve since started to feel more relaxed, and it was nice to spend some time settling into our apartment. We decided to move our bed into a different room, which entailed a good deal rearranging but I think is an improvement.

I hope the end of your year brought you peace and hope as well.

Linked at The Sunday Post at Caffeinated Book Reviewer, the Sunday Salon at Readerbuzz, and the Monthly Wrap-up Round-up at Feed Your Fiction Addiction

January 5, 2024

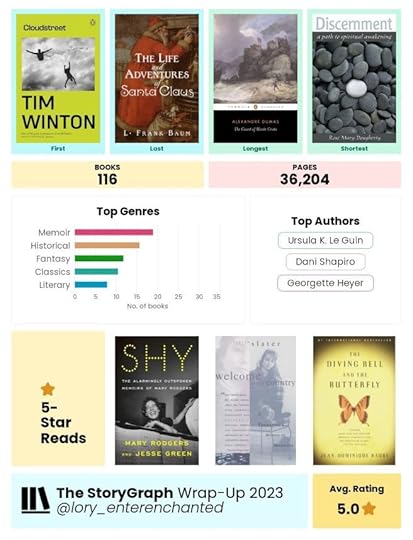

My #StoryGraph Year

In 2023 I decided to transfer my reading records to The StoryGraph – I still use Goodreads for selected reviews, but I wanted a non-Amazon-owned place to keep records, mainly for myself.

After a full year of using The StoryGraph, here’s my assessment:

What I likeClean and simple interface.Easy to keep track of reading challenges.Pretty extensive book database (with some caveats, see below).Independently owned.Statistics are fun and graphically attractive.Here’s my 2023 stats summary, which gives a few highlights:

What I don’t likeBook database has missing information and errors. It’s possible to add or correct information but this is time consuming.Not all stats are useful for me and the problems with the book database play a role in this. For example, I’d like to keep track of which books I read in digital and which in paper form, but this info is not always there and I can’t be bothered to fix it.I find questions on review page about book (e.g. Did you find the characters loveable? Flaws of main character a main focus?) silly and not useful.No author information.What I wish were differentAbove all, I wish there were more ways to interact with other members, for example including a self-description, and a chance to comment on others’ reviews. Such social features could be optional for those who don’t want them. It’s the main thing I miss from Goodreads.The Home Page should have Books Read on it, or an option to choose that instead of another section like Recommendations or Giveaways. This is the section I use the most and it’s annoying to always have to click to it through my Profile.The Community page is overwhelming, I would like to be able to filter it so as to just see when someone leaves a review, for example. I don’t need to see every time someone starts or makes progress in a book.I wish the book cover image was included on book review pages (they are text only).Wish there were a way to create one’s own questions for book reviews, to gather custom information and create personally useful stats.

What I don’t likeBook database has missing information and errors. It’s possible to add or correct information but this is time consuming.Not all stats are useful for me and the problems with the book database play a role in this. For example, I’d like to keep track of which books I read in digital and which in paper form, but this info is not always there and I can’t be bothered to fix it.I find questions on review page about book (e.g. Did you find the characters loveable? Flaws of main character a main focus?) silly and not useful.No author information.What I wish were differentAbove all, I wish there were more ways to interact with other members, for example including a self-description, and a chance to comment on others’ reviews. Such social features could be optional for those who don’t want them. It’s the main thing I miss from Goodreads.The Home Page should have Books Read on it, or an option to choose that instead of another section like Recommendations or Giveaways. This is the section I use the most and it’s annoying to always have to click to it through my Profile.The Community page is overwhelming, I would like to be able to filter it so as to just see when someone leaves a review, for example. I don’t need to see every time someone starts or makes progress in a book.I wish the book cover image was included on book review pages (they are text only).Wish there were a way to create one’s own questions for book reviews, to gather custom information and create personally useful stats.These would be nice, but are not game-breakers for me, so I’ll stick with The StoryGraph for another year at least.

I took part in a few reading challenges created by the site:

The January Reading Challenge, which has a prize draw for those who read at least 1 page every day in the first month of the year. I completed this, but didn’t win. Better luck this year!The Read the World Challenge, which has prompts for reading books from various countries — I completed only half of the prompts, but it did get me to read books from a couple of countries I might not have otherwise (Argentina, Trinidad). I’m signing up again this year.The StoryGraph Onboarding Challenge, which has 6 prompts that encourage using StoryGraph features like Recommendations and Readalongs. I completed 5 out of 6 and it did help me to find some interesting reads. Haven by Emma Donoghue, for example, fit the category “A book published in the last three years that fits your reader profile.” I’ll do this again as well.Last year, I created a page for my own Spiritual Memoir Challenge, and a few people signed up, though I don’t know if they carried through. This year, I’ve set up a Challenge page for Book’d Out’s Nonfiction Reader Challenge (since there wasn’t one already), and one for the Ozathon. I’ve also set up a Readalong page for the January Oz book, and if anybody makes use of this, I’ll keep doing it for the rest of the series.

Do you use The StoryGraph or have you thought about it? What has been your experience?