Lory Widmer Hess's Blog, page 5

September 22, 2024

Postcards from Switzerland: St Ursanne

For my birthday weekend it was my idea to visit St. Ursanne, a lovely town about a half hour drive away. We’d been there in our first year for the medieval festival that takes place every July, but not since then.

The patron saint with his legendary bear, with view across the river Doubs to the town

The patron saint with his legendary bear, with view across the river Doubs to the town Apples and roses

Apples and roses The Collegiale (church)

The Collegiale (church) Memento mori on the church wall

Memento mori on the church wall Archway that seems inspired by Chartres, with its seated Madonna and Child

Archway that seems inspired by Chartres, with its seated Madonna and Child Strange capitals that include mermaids and a wolf being taught in school

Strange capitals that include mermaids and a wolf being taught in school Detail of interior with restored decoration

Detail of interior with restored decoration Vaulting of the church

Vaulting of the church Archway through the town wall

Archway through the town wall We hiked up to the “hermitage” where the saint retreated

We hiked up to the “hermitage” where the saint retreated View of the town from above

View of the town from aboveThe town was much quieter than during the festival, without many shops or other sights, and it was too hot to do much hiking. We enjoyed ice cream and a drink and the quiet atmosphere — at least, away from the main road and its motorcycle traffic.

Hope you enjoyed this glimpse as well!

September 18, 2024

Coming Soon: Lecture and Workshop in Chestnut Ridge, NY

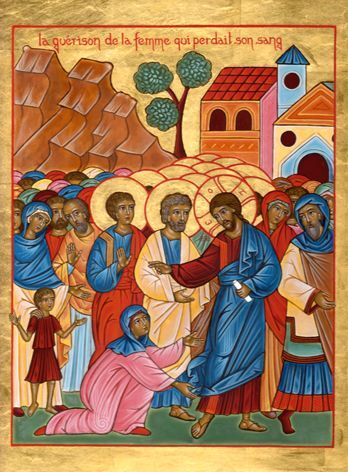

In one month, I’ll be in Chestnut Ridge, New York, where I will be giving a lecture and workshop based on my book, When Fragments Make a Whole. Please share this information with anyone who might be interested and able to come, and of course, consider yourself invited!

Working with the Healing Power of the Gospels in our LivesOctober 18-20, 2024

Working with the Healing Power of the Gospels in our LivesOctober 18-20, 2024 Christian Community Church

15 Margetts Road Chestnut Ridge, NY

$10-$30 suggested donation per section

Friday Evening Talk: 7:30 PM

A Pattern of Wholeness: The Sequence of Healings in the Gospels

Lory will read excerpts from and talk about the process of writing her book, When Fragments Make a Whole: A Personal Journey Through Healing Stories in the Bible. As she studied and worked creatively with the stories of individual healing in the four Gospels during a difficult time in her life, she found herself following a path that led to greater integration and self-awareness. Christ wants to help us to take up our destiny with a greater degree of freedom and responsibility than ever before; the sequence of healings can help to show us the way.

Saturday Workshop: 9:00 AM-Noon

Part of the Pattern: Connecting our own stories with the healing impulse of Christ

The healing forces of Christ are at work in the life-story of all human beings. Lory will lead participants in exercises of contemplative reading and writing that can help to make those forces more visible and conscious. Bring paper and a writing utensil.

Sunday Sharing: 12:15 PM after the Consecration of the Human Being

The Healing Medicine of the Sacrament

Lory will share from her own story about how she became aware of the healing influence of the sacraments in their renewed form, particularly the Consecration of the Human Being and the Sacrament of Consultation. This will serve as an invitation to an open conversation about this “medicine,” how we experience its transformative power, and how Christ is calling us to work in new ways with others.

Please email Rev. Anna Silber with questions: annasilber21@gmail.com / christiancommunitysv.org

September 15, 2024

How To Be Unhappy: Madame Bovary

As I’ve mentioned before, I spent the summer reading Madame Bovary in French, trying to make up for not reading it when I was supposed to in college, along with boosting my language skills. I was very happy to have some company on this challenge, notably Emma of Words and Peace, a native speaker and teacher who is always so supportive of my French-reading efforts, and Deb of ReaderBuzz, who amazed me with her determination to make it through, as she’s teaching herself the language. (She kept a translation alongside, but was able to read much of the book in French.)

In our Discord discussion group, Deb made a comment I found brilliantly encapsulated the essence of this reading experience:

Madame Bovary, from the point of view of someone who has studied happiness for many years, did everything wrong.

She compared her life to that of others, and found her life lacking.She bought things to make her feel better.She couldn’t seem to take joy in the husband she had.She couldn’t seem to take joy in the child she had.She could not find her life’s purpose.She did not realize that initial joy eventually fades because the constant search for happiness leads to a hedonistic treadmill.She centered her life on herself, and never focused on others.She had no social support.She did not practice gratitude.She missed out on simple joys.

“It’s a cautionary tale,” Deb concluded.

Indeed, Emma Bovary spends the book in a fruitless and ultimately fatal pursuit of happiness. What can this teach us, members of a civilization that has been engaging in such a pursuit for centuries, and is now on the brink of extinction?

Flaubert’s book was found scandalous at the time of publication for frankly featuring a woman’s infidelity to her husband, but I think the greater infidelity is to her own spiritual center. Through her, Flaubert points obliquely to a wider lack of moral integrity in the culture in which she is embedded, an emptiness that encouraged her frantic search for fulfillment. She is a symptom, not the originating cause of this malaise. And its continuing unfolding can be seen all around us, in our consumer-oriented, pleasure-obsessed society that seems to be growing more depressed and anxious by the day.

The book was an instant “succes de scandale,” but its continuing fascination can no longer be attributed to outraged morals. We need to look more deeply into what caused Emma to become, essentially, an addict: addicted to sex with men who didn’t truly care for her, to her delusional notion of “love”, and to consuming material things beyond her ability to pay for them.

In fact, it was being a shopaholic, not an adulterer, that led to Emma’s suicide, and perhaps that’s what early moralists actually objected to; she was never suitably punished for her crime, nor repentant for it. Her infidelity is not uncovered until she’s died and been buried, upon which her loving, stupid husband Charles also dies, apparently of a broken heart. Meanwhile, the moneylending merchant who deliberately sucked Emma dry, along with the quack pharmacist who usurped Charles’s business as a doctor, prosper exceedingly.

Flaubert’s cynical critique of the society emerging out of the industrial revolution points up the emptiness at its core, its lack of spiritual substance. Religion is repeatedly presented as ineffectual, hypocritical, and obtuse; perhaps the most powerful example is when Emma and her prospective lover Leon meet up in a cathedral, where Emma vaguely intends to nobly renounce temptation. A priest insists on showing them around the building, oblivious to the mounting sexual tension, until Leon impatiently drags Emma away for their famous carriage ride through the streets of Rouen.

“What is a Christian?” is heard in another scene, in ironic counterpoint to Emma’s inner struggles. Another priest has been blind to her need for help, brushed her off and turned away to instruct some naughty children in their catechism. The mindless repeating of platitudes, clearly, is powerless to help us in our real dilemmas. But no other help is offered to Emma, and she inexorably descends into the abyss.

The most telling incident, to me, was again not related to Emma’s infidelity, but to her wish to make her husband into something he is not, so that she can respect and love him according to her inflated romantic ideals. Wanting him to become a famous, groundbreaking doctor, she pushes him to perform an experimental surgery on a clubfooted boy. The foot turns gangrenous and the leg has to be amputated, leaving the boy worse off than before.

Charles is devastated and guilty, but Emma takes no responsibility. She only condemns Charles all the more for being so incompetent. Her refusal to see her equal role in the disaster is what truly damns her, in my opinion. When we cannot see the harm we do and humbly resolve to make amends, changing ourselves so that others may suffer less, we turn to the siren call of evil. Emma’s passionate pursuit of “love” is revealed as a complete sham, for there is no true love without responsibility.

I found myself both bored and fascinated by this tale, frustrated by Emma and her lack of moral center, not wanting to sympathize or identify with her. Yet in the end, I had to recognize that I, too, can be pulled away from my truest desires and fall into the same kind of trap, even if on a less dramatic scale. I frequently cause harm to people through my coldness and indifference, as she has harmed and been harmed in that way as well. What is needed is not to condemn any one, but to wake up to that vicious, sick cycle and start to see each other more truly. To be Christian in a real sense, perceiving the living, suffering core of humanity in every person, and making ourselves vulnerable enough to honestly share our own human core.

Then we will find ourselves able to ask for and receive what we need, and not become trapped in a cycle of unfulfilled desire. We will practice the opposite of Emma’s recipe for unhappiness:

We will not compare our lives to others and find it lacking.We will not need to buy things to make us feel better.We will accept people as they are, knowing we cannot change them, only ourselves.We will take joy in the children in our lives, letting them know that they are accepted and beloved.We will find our life’s purpose.We will realize that initial joy eventually fades because the constant search for happiness leads to a hedonistic treadmill.We will care truly about others and not be solely self-preoccupied.We will acknowledge and meet our fundamental human need for social support.We will experience and practice gratitude.We will find fulfillment in simple joys.When I’m tempted to do the things that make me unhappy, I’ll try to remember this cautionary tale.

September 11, 2024

Book Excerpt: Better Living Through Literature

I am pleased to announce that my blogging friend Robin Bates has a new book available: Better Living Through Literature: How Books Change Lives and (Sometimes) History. Can books create such personal and social change, and is that in general a good thing? I think all of us here believe the answer is “yes”, but we might not have the research to back up our hunch. Robin has done that research for us, offering rabid readers a survey of views about literature’s impact from Plato to the present, incorporating practical and personal examples of how literature has changed lives, including his own.

Robin is a recently retired professor (Professor Emeritus of English at St. Mary’s College of Maryland), and I’d love to have taken one of his classes. His erudition is balanced by humor, and he’s also not afraid to show deep feeling, acknowledging the emotional impact of reading even as he strives to give an objective hearing to many diverse points of view. Non-stuffy, yet grounded in years of study and teaching, his writing is highly readable and enjoyably educational.

Robin graciously gave me permission to post an excerpt from the book; here is a section from the Introduction. I hope it may inspire you to read further!

Better Living Through Literature was published by Quoir Books in 2024 and is available from Amazon. For more musings on life and literature, be sure to visit Robin’s blog, Better Living Through Beowulf.

The Power of Literary Immersion

By Robin Bates

Operating through images and stories, literature has the potential to invest us emotionally, intellectually, and spiritually in the situation put before us. For a famous literary example of the process at work, check out the scene in Hamlet where the prince encounters a troupe of actors. Hamlet marvels at how one of them can see himself in a literary character—and not only see himself but become emotionally involved. The character in this case is Hecuba, the queen of Troy, who sees the Greeks kill first her son Hector and then her husband Priam. Hamlet shakes his head in wonder at how the actor becomes Hecuba, asking, “What’s Hecuba to him, or he to Hecuba, that he should weep for her?”

It’s not only actors who become immersed. Hamlet intends to use the play, for which he has provided a scene, as a “mousetrap” that will “catch the conscience of a king.” If Claudius can see, enacted on the stage, someone murdering a king, he will not be able to hide from Hamlet whether he has done the same to Hamlet, Sr.

Edwin Austin Abbey, The Play Scene in Hamlet (1897)

Edwin Austin Abbey, The Play Scene in Hamlet (1897)And so it works out. Claudius, already fully immersed in the play, goes on to have the most intense theatrical experience of his life. Seeing himself in a staged fiction that knows him as well as he knows himself, he freaks out and rushes from the room. The trap has snapped.

Imaginary worlds, oral and written, have been immersing audiences since families sat around campfires in prehistoric times, and people have striven to document the experience ever since. In one of the world’s great narratives, the Spanish novelist Cervantes famously shows his protagonist Don Quixote so moved by chivalric romances that he can no longer distinguish between them and reality. As a result, he ends up ludicrously attacking windmills, mistaking them for enemy giants. Quixote, of course, is an extreme example, but many works of literature, bad as well as good, have swallowed up readers.

Drawing of Don Quixote and Sancho Panza by Gustave Dore

Drawing of Don Quixote and Sancho Panza by Gustave DorePhilosopher Georges Poulet dramatically describes the phenomenon as follows:

“As soon as I replace my direct perception of reality by the words of a book, I deliver myself, bound hand and foot, to the omnipotence of fiction. I say farewell to what is, in order to feign belief in what is not. I surround myself with fictitious beings; I become the prey of language. There is no escaping this takeover. Language surrounds me with its unreality.”

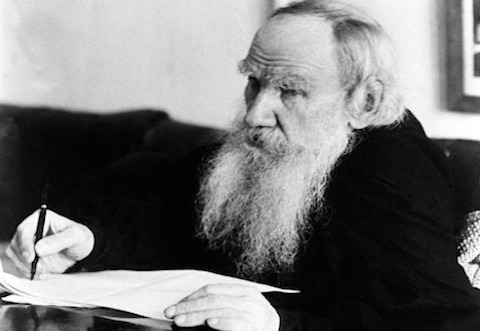

The great Russian novelist Tolstoy once noted that we are “infected” with an author’s ideas and emotions and opined, “The stronger the infection, the better is the art as art.”

Tolstoy at work

Tolstoy at workAs we will see, many thinkers have seen literary infection or literary immersion as a force for good. To give you a quick foretaste of what is to come, Romantic poet Percy Shelley contended that immersion in the works of Sophocles, Dante, and Shakespeare puts one in touch with revolutionary energies, while Victorian poet and critic Matthew Arnold predicted that poetry would one day replace religion as the primary motivating moral force.

Yet we must admit that not everyone has been positive. As Plato saw it, Homer-reciting rhapsodes were like demagogues, exerting a dangerous sway over audiences, which prompted him to ban them from his ideal rational Republic. We’ve already mentioned the 16th century Puritan Stephen Gosson who, disturbed by the hypnotic power that Elizabethan drama exercised over audiences, complained that poetry infects us “with many pestilent desires, with a siren’s sweetness drawing the mind to the serpent’s tail of sinful fancies.” 18th century German parents, as they watched their children adopt the clothing and mannerisms of Goethe’s protagonist young Werther, railed against Goethe’s novel out of fear that their young ones would also follow Werther’s road to suicide. And then there have been those modern parents and church leaders so worried about seeing young people disappear into the Harry Potterverse that they have attacked and, in a few instances, publicly burned J.K. Rowling’s novels.

The suicidal young lover, Werther

The suicidal young lover, WertherObserving the dynamics at work in such encounters, novelist Iris Murdoch notes that “Art is close dangerous play with unconscious forces.” If we enjoy art, she says, it is because “it disturbs us in deep often incomprehensible ways; and this is one reason why it is good for us when it is good and bad for us when it is bad.” Notice that she doesn’t always say that literature is good for us: deep contact with unconscious forces can go multiple ways.

Indeed, because of the power of literary immersion, it’s important to add reflection (and, I would add, application) to the coaching process. The best literature invariably encourages such reflection whereas, as we will discuss in the chapter on pop lit, lesser literature sometimes settles for an unreflective emotional high.

To highlight literature’s power, I have focused on those genres that most take over our minds, conveying us into their worlds and, at least for a moment, persuading us to accept an alternate reality. In other words, I focus on drama, poetry, and fiction. It so happens that, throughout the centuries, these are the three genres that have gotten the most attention, with different ages choosing one of the three to stand in for literature as a whole. In ancient Athens, heroic and tragic poetry commanded the most attention, in Elizabethan England drama, in the 19th century lyric and narrative poetry, in the 20th century the novel, film, and television. In each case, thinkers sought to understand some version (to use a modern example) of the literary immersion that Harry Potter fans experienced when, after having stood in bookstore lines at midnight to purchase Goblet of Fire or Deathly Hallows, they opened the volume and lost themselves in the world of Hogwarts.

Extracted by permission from Better Living Through Literature (Quoir Books 2024).

September 7, 2024

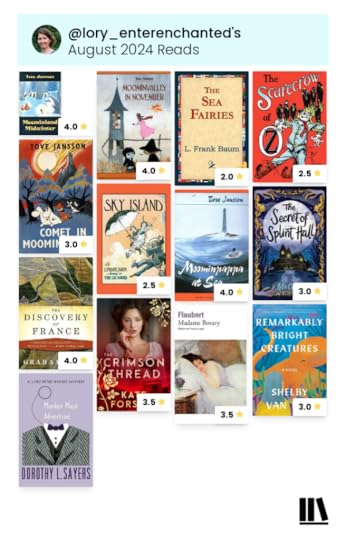

Month in Review: August 2024

August was a month where I celebrated my summer Moomin binge, covered two more Oz books, and also knocked off three categories for the Nonfiction Reader challenge.

Here’s what I read during August:

Moominland Midwinter, Moominvalley in November, Comet in Moominland, Moominpappa at Sea by Tove Jansson – Moomin Week, Women in TranslationThe Scarecrow of Oz, The Sea Fairies, Sky Island by L. Frank Baum – Ozathon (plus related works)The Secret of Splint Hall by Katie CottonThe Discovery of France by Graham Robb – inspired by Paris in JulyThe Crimson Thread by Kate Forsyth Madame Bovary by Gustave Flaubert – Summer in Other LanguagesRemarkably Bright Creatures by Shelby Van PeltMurder Must Advertise by Dorothy Sayers – RereadSee my reviews on The StoryGraph

Language

LanguageYou’ll notice I read a lot of whimsical and magical books this month, which I think I needed as a counterweight to my major challenge of the summer, getting through Madame Bovary in French. It defeated me in college (I read the English translation on the sly), but this time around I was greatly helped by the advent of e-books, which allow me to look up words without all that tedious searching in dictionaries. Aside from a lot of unfamiliar vocabulary, I found that the language was not too difficult, as Flaubert’s devotion to realism means he describes many things in great sensory detail, rather than using lots of obscure figurative language — though he does also do a good metaphor on occasion.

That said, one is often supposed to read between the lines. I had the feeling I missed a fair amount of what was communicated in more subtle ways, though I did certainly get the gist of the story, a very sad and pessimistic one. No wonder I needed regular doses of Moominmamma as an antidote!

Isabelle Huppert as Madame Bovary

Isabelle Huppert as Madame BovaryLife

Another notable event in August was that I graduated from my two-year training in spiritual direction. When I started the program, I wrote one post about it thinking I’d do that on a regular basis, but ended up not doing a single follow-up post! It was quite an intense experience and seemed to need its own space. Our online graduation was very moving as our group of nine wonderful women blessed one another for our future ministry. Meeting such amazing people is what keeps me going when bad news seems overwhelming. There is also so much goodness, often working quietly and humbly. It gives me hope to know there are individuals of such generosity and courage out there in the world.

What gave you hope this month?

Linked at The Sunday Post at Caffeinated Book Reviewer, the Sunday Salon at Readerbuzz, and the Monthly Wrap-up Round-up at Feed Your Fiction Addiction

September 5, 2024

10 Books of Summer 2024

We’ve crossed over into September, so it’s time to check on how I did with my 10 Books of Summer list (Challenge hosted by Cathy of 746 Books). I think of this as a way to knock off some books from other challenges and reading projects, and it worked pretty well for that, although I did not stick very closely to my original list at all.

My original list:

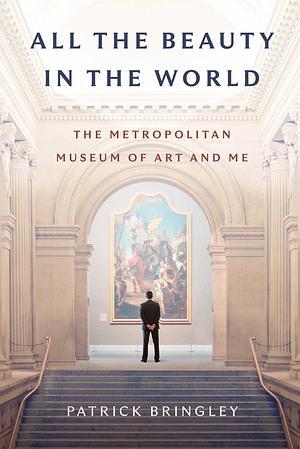

Grimbold’s Other World by Nicholas Stuart Gray for Reading the MeowThe Brain that Changes Itself by Norman Doidge for Nonfiction ReaderSavor by Fatima Ali for Nonfiction ReaderAll the Beauty in the World by Patrick Bringley for Nonfiction ReaderMomo by Michael Ende for Summer in Other LanguagesMadame Bovary by Gustave Flaubert for Summer in Other LanguagesEva Luna by Isabel Allende for StoryGraph Reads the WorldRunning in the Family by Michael Ondaatje for StoryGraph Reads the WorldWell That Was Unexpected by Jesse Q Suntano for StoryGraph Reads the WorldWhat I actually read:

Dewey for Reading the Meow American Nations for Nonfiction Reader All the Beauty in the World for Nonfiction Reader Chartres for Nonfiction ReaderThe Brain that Changes Itself for Nonfiction Reader Well That Was Unexpected for StoryGraph Reads the World Moominland Midwinter and 5 other Moomin books for Moomin Week and Women in TranslationMadame Bovary for Summer in Other Languages (review pending)I think I’ll always remember this as the summer I managed to read Madame Bovary in French — I had to put aside my other goal of reading a book in German for the time being, in order to focus on one foreign language at a time. Really pleased that I managed that, even though it was such a downer that I had to balance it out with lots of Moomin books. If I count all of those, I did make it to 10 books! Regardless of the numbers I did have some great reading this summer, and that’s what matters.

How was your summer reading this year?

Photo by hello aesthe on Pexels.com

Photo by hello aesthe on Pexels.com

August 25, 2024

The marvelous Moomins for #Moominweek #WITMonth

Well, I thought I might read a Moomin book or two for Moomin week but ended up going on an absolute binge where I finished reading all the novels — six of them this summer in addition to the two I’d read previously. I did it in a completely mixed up order, thus:

Finn Family Moomintroll (2 in series, 1948) translated by Elizabeth PortchMoominsummer Madness (4 in series, 1954) translated by Thomas WarburtonMoominpappa’s Memoirs (3 in series, 1950) translated by Thomas WarburtonTales from Moominvalley (6 in series, 1962) translated by Thomas WarburtonMoominland Midwinter (5 in series, 1957) translated by Thomas WarburtonMoominvalley in November (8 in series, 1970) translated by Kingsley HartComet in Moominland (1 in series, 1946) translated by Elizabeth PortchMoominpappa at Sea (7 in series, 1965) translated by Kingsley Hart

Can’t get much more out of order than that! And I finished up by reading The Moomins and the Great Flood (1945), translated by David McDuff, a picture book that is is more of a prelude – the characters have not yet settled into their familiar forms, and the style and tone is quite different from the later books. Interesting to see that the spooky Hattifatteners were there from the beginning, though.

I would now like to read through the series in order, to observe how Jansson’s writing developed over time. However, I don’t think reading in order is essential, with the possible exception of Moominpappa’s Memoirs, where it is helpful to know who some of the characters are before learning about the history of their parents.

I did find that I enjoyed the later books quite a bit more. The earlier ones are more randomly silly — Comet in Moominland in particular is a weird, if inventive, combination of whimsy and horror, while I remember Moominsummer Madness and Finn Family Moomintroll as being pleasant, imaginative diversions that did not leave a strong impression on me.

However, the later books became more deliberately crafted, increasingly beautiful and even profound. I think that my favorite, pending a reread, was Moominland Midwinter, in which Moomintroll, who normally hibernates with his family, wakes up and experiences winter for the first time. This is basically a postapocalyptic scenario that at first horrifies him, but slowly he grows into his new environment, makes new friends, and discovers untapped resources in himself. And he gets to experience the joy of spring coming again, rather than simply waking up with it already there. It’s a lovely story about finding life and hope in an unfamiliar situation, something we could all stand to learn right now.

I also particularly enjoyed Tales from Moominvalley, shorter works that each concentrated on a different character, containing many gems of sly humor and psychological insight. Plus, we finally learn about what really happened when Moominpappa sailed away with the Hattifatteners, a mysterious and traumatic event first hinted at in the Great Flood story and haunting many of the others.

The last two books, Moominpappa at Sea and Moominvalley in November, bring in an increasingly melancholic, indeed “Novemberish” tone, that I would imagine is more appealing to adults than children. But the whole series is a genius mix of elements that appeal to all ages, pointing to the innocence in the adult and the maturity of the child. These are books for humans, or for the Moomin in all of us, not for some segregated age group.

As well as tying in with the Moomin celebration, I am glad to have a chance to participate in the event honoring women in translation. Tove Jansson is now one of those translated authors of whom I have read the most, including several of her works published for adults, and I’ve loved all of them.

Several translators worked on the Moomin books, and I’m not sure whether the differences I detected between them were due to the original or to a different translator’s style. I wonder what the story was behind the choice of different translators — if anyone knows, please inform me.

I had a truly marvelous time with the Moomins this summer, and if you read one or more of the books, please let me know so I can check out your posts.

August 18, 2024

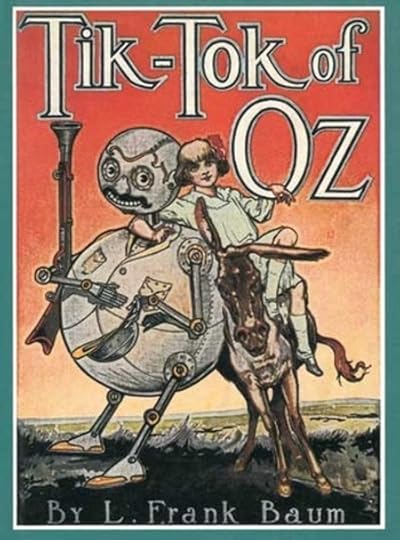

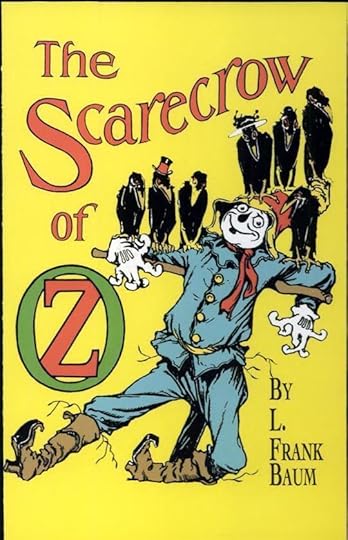

#Ozathon24: More adventures outside Oz

As I make my way through the latter books of the Oz series, I notice how Baum kept trying to get outside the confines of Oz. Perhaps he realized that giving it an all-powerful and all-knowing ruler put something of a damper on conflict and adventure, or perhaps the land had been circumscribed in a way he found too limiting, with its four colored parts and surrounding Deadly Desert.

The eighth book, Tik-Tok of Oz, simply ignores that barrier — when an overbearing Queen forces her handful of subjects to turn soldier and set out to conquer the Emerald City, they are diverted by Glinda so they end up in a region outside Oz. (The Desert is never mentioned.) They then meet up with up with some other characters from Oz who are traveling outside for their own reasons, along with a new pair, Betsy Bobbin and Hank the mule, who have gotten there after the ship they are traveling on is lost in a storm.

If some of this sounds familiar, you are right: the shipwreck is from Ozma of Oz, the army a combination of the ones in that book and The Land of Oz. The rest of the tale also contains many mangled bits of other books: the Nome King is the enemy again, as in Ozma, having remembered his wicked ways, but this time the Shaggy Man (from The Road to Oz) wants to rescue his brother. Polychrome reappears, too, and Shaggy has mysteriously forgotten he ever met her. There are also dragons and vegetable people reminiscent of those in Dorothy and the Wizard in Oz, and a journey through the center of the earth which also recalls that nightmarish installment.

It makes a bit more sense when you know that Baum had in the meantime produced a musical play called “The Tik-Tok Man of Oz” but mainly based on Ozma of Oz and elements from other books. He says in an introduction that “Tik-Tok” the play is not the same as the book, but it clearly was the basis. (Road was being written at the same time as the play, which accounts for the similarities there.) There are also significant changes. Betsy, a curiously character-less character, appears because copyright prevented Dorothy from being in the play. Hank is the Toto stand-in, meant to be played by a vaudeville comedy duo. The plant-based folk are roses rather than root vegetables, also more suitable for the stage, where choruses of pretty girls were required. And so on.

All in all Tik-Tok was readable, but not as memorable as some of the books from which it was derived. The part that stuck most with me from my childhood reading was when Betsy and Co. are in the land on the other side of the earth, waiting to learn what the Nome King’s punishment will be for sending them there. She stays with the lovely queen of light, attended by various kinds of personified illumination — Daylight, Starlight, Electra, and so on. More stage effects, but at the time it caught my imagination, especially the assertion that Electra had as honorable a pedigree as the others. It’s one of those touches of excitement about modern technology that Baum is often slipping in, among more traditional fairy-tale trappings.

The next book, The Scarecrow of Oz, starts with another couple of characters new to Oz, but previously introduced in some non-Oz books: the girl Trot and her older friend Cap’n Bill, who get sucked into a whirlpool off the California coast. I find these two to have more substance to them than Betsy and Hank, even though they are obviously a tie-in effort. Unfortunately they are examples of Baum’s attempt to transcribe childish speech patterns and seaman’s dialect, which I find irritating, but otherwise they’re not a bad pair of protagonists. Cap’n Bill is a very handy companion to have on an adventure, with his skills and knowledge from a lifetime at sea and pockets full of useful things; Trot is another plucky girl in the Dorothy mold.

Anyway, Trot and the Cap’n are saved from the whirlpool but then stuck in an cavern with no easy way to the outside, until another creature caught by the whirlpool appears, an Ork — one of those conglomerates Baum loved to dream up. Together the three make their way out of the cavern, and a series of adventures take them into the Land of Mo (another tie-in to an earlier book) and over the Deadly Desert (which has reappeared). Thus they do come at last into the Land of Oz, which is no longer invisible to outsiders, as Baum had to give up that way of stopping the Oz adventures.

However, since the little kingdom where they have arrived, Jinxland, is completely cut off from the rest of Oz by high mountains, we might as well still be somewhere else. Jinxland is ruled by King Krewl, whom you will not be surprised to learn is not a good ruler, and pays no homage to Ozma. It’s also infected with wicked witches, illegal in the rest of Oz. And Krewl is a usurper who wants to marry off the rightful ruler, Princess Gloria, to one of his cronies, severing her from her true love, Pon the gardener’s boy, and using some dreadful magic to bend her to his will.

Trot and Cap’n Bill, as well as Button Bright, who has randomly shown up again, get involved in the drama, but are no match for Krewl and the witches, until the Scarecrow finally appears. His name is in the title, but his role starts only late in the day when he’s sent by Glinda to rescue the outsiders she’s read of in her Magic Book, which records everything that happens. One wonders why she has not so far noticed the usurping, cruelty, and illegal magic going on in Jinxland, but never mind.

The Scarecrow, in fact, is no match for Krewl either, and really the Ork should get more credit for saving the day … but I suppose “An Outrageous Ork in Oz” was not considered a good title.

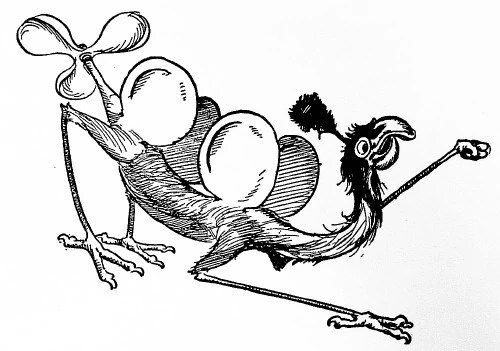

John R. Neill’s illustration of the Ork

John R. Neill’s illustration of the OrkI’ve read that Baum’s wife Maud considered this the best of the Oz books, but I can’t agree. Though there’s some nicely vivid writing, exciting adventure, and memorable characters, the narrative is disjointed. The Jinxland section has a generic operetta sort of feel, and in fact was drawn from yet another Baum project: a film called “His Majesty, the Scarecrow of Oz.” It flopped, but was recycled into the requisite Oz book one year later, adding in the part about Trot, Cap’n Bill and the Ork.

These books go to show how Baum’s real love was the stage and film, at which he was an early pioneer who never became successful. He wanted to bring Oz onto the stage, but kept getting pulled back onto the page, with mixed results. But we have a few more books to go, and as far as I recall some of them are more successful.

Please visit The Book Stop for another excellent analysis of Tik-Tok of Oz, and be sure to share your thoughts if you’ve read these books.

August 10, 2024

Nonfiction Reader: Culture, Architecture, and Science

I’m doing a combined post with shorter reviews here, because in the summer my attention span for blogging has gone out the window. Plus, these books happen to go together well, as I hope you’ll agree…

In early June I read All the Beauty in the World: The Metropolitan Museum of Art and Me by Patrick Bringley. I enjoyed this glimpse behind the scenes by a former museum guard, a job the author took on in the wake of his brother’s death when his high-profile job at the New Yorker became meaningless to him. In some ways undemanding, in other ways challenging (especially on the feet), being a guard gave him a chance to soak in the presence of great art and to spend many hours reflecting on what he saw. He shares some of his insights, along with giving us respect and appreciation for some of the most unsung members of the huge crew that makes such a place possible. He reminds me of the value of slowing down in the presence of art, not trying to inhale everything at once, but taking time for deep encounter with our surroundings — and also with the people we meet. Even as a museum full of random objects tempts me to hurry by and not stay with anything for long, I can try to resist that impulse, hold still and think, return and look again.

Fortuitously, pretty soon I had an opportunity to do just that, when I took ten days in July to visit the cathedral in Chartres. Along with simply looking, I read a number of books before, during, and after the visit, one of which was Chartres: Sacred Geometry, Sacred Space by Gordon Strachan. There was lots to ponder in this architectural-historical-geometrical-theological consideration of the great cathedral, many mysteries to be considered and often no clear answers, but an interesting case to be made for the influence of Islam on Gothic architecture, as well as some of the links to ancient Celtic sites. The author sometimes lost me with his geometrical square root calculations, but made a fascinating point about the rectangular crossing of the cathedral representing the self-denial of God (backed up by theological quotations). It gave the saying “deny yourself, take up your cross and follow me” a whole new meaning for me.

After I got home, I finished The Brain that Changes Itself by Norman Doidge, a book I’ve been chewing on for a while and would like to read again. My favorite kind of science book is one that gives a glimpse into science as a living, evolving process, rather than a fixed body of knowledge. And that’s what Doidge does here, giving examples of current research into how the brain, contrary to previously held opinion, is “plastically” formed and re-formed throughout life. Not only knowledge itself, but the instrument through which we come to know things, can and does change! Many of the stories involve people with injuries or disabilities coming to do things previously thought impossible, a reminder to keep our minds ever-open to possibility. Another important insight is that the plasticity of the brain is, paradoxically enough, what can cause us to become stuck in certain adverse patterns. This is compared to a sled sliding down the same path over and over — impacting the snow more and more until it’s very hard to get out of that track. Again, however, it is possible, only it takes effort, and it helps greatly to have some understanding of how the brain works. Fortunately, although at first there was resistance to the concept of brain plasticity — aptly demonstrating Doidge’s point about rigidity! — this idea is now becoming accepted and could lead to great advances in many fields.

An essay placed in the appendix considers how culture shapes the brain — far more quickly than evolution. Thus, the transformative power of art is confirmed by modern science, and we ought to take it seriously.

Patrick Bringley, All the Beauty in the World (Simon and Schuster, 2023)

Gordon Strachan, Chartres (Floris Books, 2003)

Norman Doidge, The Brain That Changes Itself (Viking, 2007)

Read for the Nonfiction Reader Challenge — Culture, Architecture and Science categories; three of my Ten Books of Summer

Walking up toward the cathedral in Chartres

Walking up toward the cathedral in Chartres

August 3, 2024

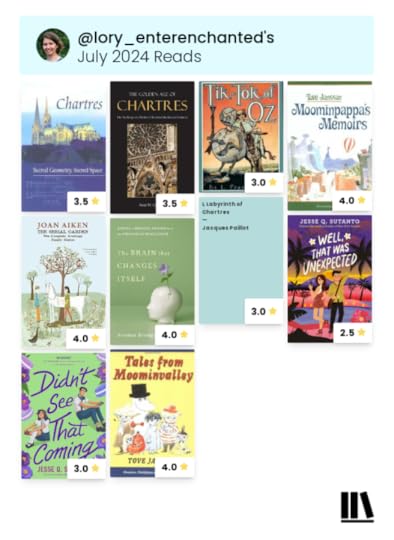

Month in Review: July 2024

It was great this month to participate in a Zoom call with some bloggers from Paris in July, Emma’s event celebrating all things French. It inspired me to start reading The Discovery of France, a fascinating look at how the country (made up of many small groups who didn’t necessarily consider themselves French) came together in the modern period. This fractured history is still influential today, and I’m learning a lot about my neighboring country.

I joined in the Olympic Book Tag — thanks Shannon for these fun prompts that provided a way to look back on my reading from the last months. It also gave me a chance to post some more photos of the Olympic Torch being passed in Chartres.

Below you can see the rest of what I read, many books tying in to present or future challenges and events.

StoryGraph has a new feature that generates wrap up graphic for the month, so I made use of those here. What do you think?

Chartres: Sacred Geometry, Sacred Space

by Gordon Strachan – Nonfiction Reader, 10 Books of Summer, review to come

The Golden Age of Chartres

by Rene QueridoI, Labyrinth of Chartres by Jacques PaillotTik-Tok of Oz by L. Frank Baum – Ozathon, review to come

Moominpappa’s Memoirs

and Tales from Moominvalley by Tove Jansson – anticipating Moomin WeekThe Serial Garden by Joan Aiken – Witch Week readalongThe Brain That Changes Itself by Norman Doidge – Nonfiction Reader, 10 Books of Summer, review to comeWell That Was Unexpected and Didn’t See That Coming by Jesse Q. Suntano – 10 Books of Summer, StoryGraph Reads the World

Chartres: Sacred Geometry, Sacred Space

by Gordon Strachan – Nonfiction Reader, 10 Books of Summer, review to come

The Golden Age of Chartres

by Rene QueridoI, Labyrinth of Chartres by Jacques PaillotTik-Tok of Oz by L. Frank Baum – Ozathon, review to come

Moominpappa’s Memoirs

and Tales from Moominvalley by Tove Jansson – anticipating Moomin WeekThe Serial Garden by Joan Aiken – Witch Week readalongThe Brain That Changes Itself by Norman Doidge – Nonfiction Reader, 10 Books of Summer, review to comeWell That Was Unexpected and Didn’t See That Coming by Jesse Q. Suntano – 10 Books of Summer, StoryGraph Reads the World

For a long time I did not use star ratings, but I’ve decided to try them out. Here’s what my stars mean to me:

5 stars are reserved for books I’ve read multiple times and consider personal favorites.4 stars are for books I found outstanding. I’ll go through at the end of the year and raise some to 4.5 stars.3 stars are for solid books that I recommend, in spite of some flaws. 3.5 puts them a cut above average, though not quite stellar enough for 4 stars.2 – 2.5 stars are for books that I found worth reading for some reason, but had serious drawbacks.1 star is for books I finished but cannot recommend.LanguageAfter taking a German test last month, I have found out I have to take a French test to upgrade my residence permit here in Switzerland. I tried to get my advanced study certificate from college accepted, but no such luck. You might think a German credential would suffice, but each town has its own official language and you have to do the test according to where you live.

I will be fine with comprehension, but my speaking and writing are rusty because I don’t actually need to use French much in daily life. With a little practice I hope to attain a B1 level. Wish me luck!

LifeMy biggest news this month was my trip to Chartres. Read about it here. Yes, this has been a very France- and French-oriented month!

In other news, my son has passed his theoretical driving test, just one step in the multi-layered process of the Swiss system. I had no idea it was so complicated, though I should not be surprised.

First you have to do an emergency aid course, then have an eye exam, apply to take the theory test, get invited to make an appointment for the theory test, actually take the theory test, and only then can you get the learner’s permit. Don’t neglect to buy an official “L” label to stick on your car! Now it will be at least a year before he can get the license — under 20 year olds must have at least 12 months of practice.

So if you ever want to move to Switzerland with a teenager, be warned…

Linked at The Sunday Post at Caffeinated Book Reviewer, the Sunday Salon at Readerbuzz, and the Monthly Wrap-up Round-up at Feed Your Fiction Addiction