Chris Howard's Blog, page 84

April 15, 2013

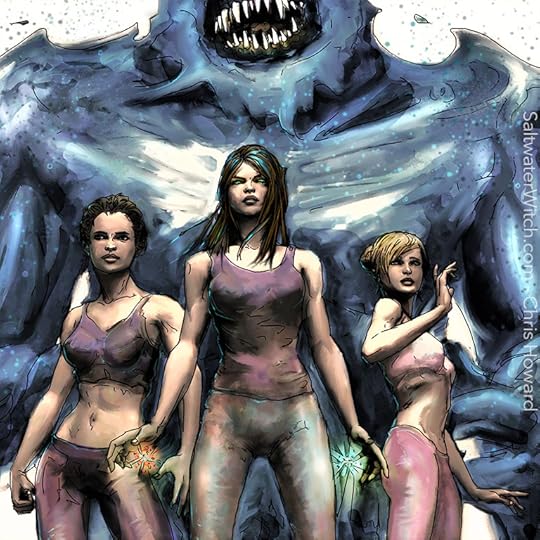

Team Saltwater Witch

Team Saltwater Witch … ready to take on the Avengers and X-men at the same time. I don’t read comics that often–or read anything as often as I would like. Time is always the problem. One of my favorite artists is Chris Bachalo, who’s worked for DC and Marvel. His beautiful work has influenced me for a while. This is Kassandra, Nicole, Jill, and Ephoros (big blue guy in the background) re-imagined as superheroes. Art Rage, about six hours.

April 7, 2013

Magic in the Night

About three hours in Art Rage and CS6. Still have some detail work to do, but here’s where things stand right now. More of my stuff down the portfolio link on my site: http://www.SaltwaterWitch.com

March 31, 2013

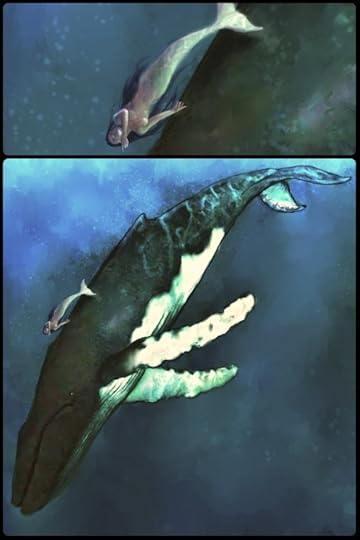

“Mermaids Discuss the Complexities of Global Shipping”

There are millions of shipping containers on vessels on the sea at any given moment, and for various reasons some of these are lost at sea en route, reported missing, and written off. Someone finds them…

March 29, 2013

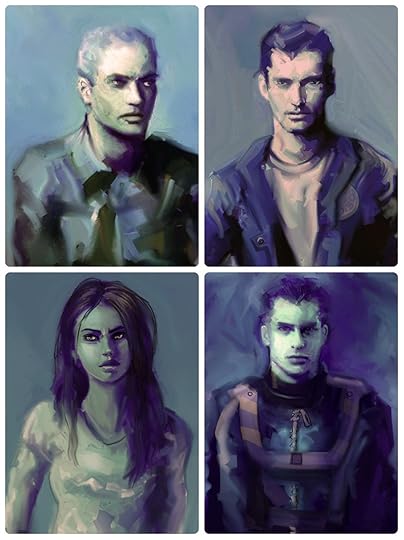

Salvage characters

Here’s some character sketching I did for Salvage, which will be out in July. Top right is the main character.

Mermaid

March 25, 2013

Frank Herbert and the Quest without a Hero

[This was my January 2013 piece for the Fantasy Roundtable]

Like any writer I have many stylistic influences spanning classical, romantic, and contemporary authors from Homer, Hugo, and Dostoyevsky to Terry Pratchett, Richard Morgan, and Caitlín Kiernan. But if I had to pick an author whose work influenced me to the core–and at a young age–it would be Frank Herbert. For a particular work it would be Dune.

One of the things Dune taught me was that the protagonist of the story can go on the quest, suffer at the hands of an oppressor, struggle through and around the obstacles enemies lay out for him, and he can even complete the quest and emerge victorious. And he can do all of this without being a hero.

Or maybe Paul Atreides was just a different sort of hero, one I had never come across before. With Dune, Frank Herbert made me look at heroes and their quests in a different way.

I think many fantasy writers would automatically stick Tolkien on the list, but although I have read the Lord of the Rings dozens of times—and The Silmarillion at least ten—I can’t say Tolkien affected me the same way—or as deeply. Certainly Tolkien showed me the wonder of maps, invented languages, an excitingly deep world, and how a big story—Lord of the Rings—can become just one insignificant fragment of a far longer and more complicated story. These are the things I still love about The Hobbit, The Lord of the Rings, and The Silmarillion. I probably would have said Tolkien was my favorite author when I was a teenager, but when I hit twenty or so, after four or five readings about Paul Atreides and all the craziness he gets up to with the fremen, I sort of felt like I had graduated from The Lord of the Rings to Dune.

Dune was also exotic, non-traditional. It had European roots without being entirely European, and that drew me in. There was also a very familiar parallel with Paul’s move from Caladan with its broad oceans to the faraway and very different desert world of Arrakis. I had moved around a lot and I thought that gave me insight into Paul’s plight—typical teenager. I was living in Japan, going to high school, when I first read Dune, but I had also lived just outside Paris, and in Idar-Oberstein, Germany. I had been up and down South Korea, Italy, and through East Germany by train to Berlin. I had lived on both American coasts, and I would end up living in Silicon Valley. In my seventeen- or eighteen- year-old mind there was definitely something that connected the changes shaking up Paul’s life and the constant moving around when I was young.

If the unfamiliar and striking backdrop of Arrakis lured me in first, that was quickly followed by Herbert’s push and play with the concept of a hero. Paul Atreides wasn’t your typical innocent kid with a quest thrust on him, with everything he counted on pulled from under his feet. He wasn’t just a pawn struggling to find his way in a universe of space-folding guild navigators and galactic-scale trade and political manipulation. He was a significant piece in the Bene Gesserit breeding program. He took the terrible risk—basically gambling everything—to gain god-like powers, which he used to gather and train thousands of fanatical soldiers. He defeated the emperor’s forces, killing armies and princes, the whole time maneuvering himself onto the throne, marrying the emperor’s daughter purely for political gain. And he ends the last chapter with less control over his life than when the story started.

“Paul was a man playing god,” said Herbert.

That idea hooked me at the first reading—that the hero could take on powers that he would not be able to control, that he could end up flawed so deeply he wasn’t a hero anymore.

None of the main characters in The Lord of the Rings had an evolution like Paul Atreides. Frodo, Aragorn, and the others were heroes in the traditional sense. Even if Frodo didn’t come home whole, he came back a true hero, having lost a finger while defeating the greatest evil of his age. Paul Atreides didn’t come home from his long journey a hero. He was a messiah at the head of a monster of religious ferocity he created. Anything that monster did would be done in his name, and he didn’t really control it.

Then he unleashed it on the universe.

In Herbert’s own words, “The bottom line of the Dune trilogy is: beware of heroes. Much better to rely on your own judgment, and your own mistakes.”

Paul had the quest. He made the journey. He was victorious. There’s a clear apotheosis stage—literally. Paul Atreides is deified. He passes through the stages of the hero’s journey. He just isn’t a hero. Not in the usual sense.

I haven’t read Dune in ten or fifteen years, but I can still feel the affect that book and the following two—Dune Messiah and Children of Dune —had on me. I loved the culture clashing in Dune, the court intrigue, the power and plans of the Bene Gesserit sisterhood, the dinner parties with codes and signals and conversations being carried on at several levels at the same time—and only understood by a few. But it was the protagonist wielding power beyond his control that pulled me back into that universe again and again. It was Paul-Muad’Dib driving his followers, his family, the guilds, the Bene Gesserits, and the entire empire toward a doom he could not escape.

That is what has stuck with me to this day. Paul became a model for the kinds of heroes I love to write about. Heroes who barely have the will or personal strength to hold onto the reigns of some monstrous power that is part of them, or that they have created, and sometimes they end up being consumed by it.

In the introduction to his short story collection Eye, Frank Herbert elaborates on this theme. “Dune was aimed at this whole idea of the infallible leader because my view of history says that mistakes made by a leader (or made in a leader’s name) are amplified by the numbers who follow without question. That’s how 900 people wound up in Guyana drinking poison Kool-Aid…”

I don’t know if it’s unusual but I love the idea of a protagonist who isn’t heroic in the traditional sense. I love an unsympathetic hero–or a hero who starts the story without a shared compassion or a strong connection with the reader, and grows to become sympathetic.

On the other hand I also love a good straightforward heroic quest, where the hero is good and right and fights evil. I know Herbert has been taken as being an active opponent of the hero’s journey, the monomyth, the whole Campbell thousand-faced hero, and in the Dune trilogy it looks that way–even with Paul’s progress through the story closely following many of the steps Campbell describes. It’s what Paul ends up becoming that disrupts the structure.

I don’t think Herbert’s in the same camp with David Brin, a confirmed and outspoken adversary of the hero’s journey and the Campbellian insistence that components of the myths are common among most cultures worldwide (Read Brin’s fun and interesting “Star Wars” despots vs. “Star Trek” populists: http://www.salon.com/1999/06/15/brin_main )

Herbert was more of an explorer of conflict and ideas, using his heroes to work through serious flaws in leadership, on the environment and very long range planning, the power of linguistics, and down to challenging what’s considered normal and abnormal. In the Dune books at least, he did not focus on science or future technology. His explorations frequently brought him up against traditional character structure and reader acceptance, but I don’t consider him an enemy of the popular heroic journey and story structure. I consider him a thoughtful science fiction writer who wanted to push the boundaries of the genre in ways that focused on awareness of important issues—ecology, flaws in perception—the infallible leader, and on the dangers of accepting without examination long-held beliefs and cultural fixtures—the hero who completes the quest and returns home a better or at least a more evolved person.

Herbert said, “We tend to tie ourselves down to limited choices. We say, ‘Well, the only answer is….’ or, ‘If you would just. . . .’ Whatever follows these two statements narrows the choices right there. It gets the vision right down close to the ground so that you don’t see anything happening outside. Humans tend not to see over a long range. Now we are required, in these generations, to have a longer range view of what we inflict on the world around us. This is where, I think, science fiction is helping. I don’t think that the mere writing of such a book as Brave New World or 1984 prevents those things which are portrayed in those books from happening. But I do think they alert us to that possibility and make that possibility less likely. They make us aware that we may be going in that direction.”

***

Chris Howard is a creative guy with a pen and a paint brush, author of Seaborn (Juno Books), Salvage (Masque/Prime, 2013), and half a shelf-full of other books. His short stories have appeared in a bunch of zines, latest is “Lost Dogs and Fireplace Archeology” in Fantasy Magazine. In 2007, his story “Hammers and Snails” was a Robert A. Heinlein Centennial Short Fiction Contest winner. He writes and illustrates the comic, Saltwater Witch. His ink work and digital illos have appeared in Shimmer, BuzzyMag, various RPGs, and on the pages and covers of books, blogs, and other interesting places. Last year he painted a 9 x 12 foot Steampunk Map of New York for a cafe in Brooklyn. Find out everything at http://www.SaltwaterWitch.com

March 24, 2013

I suggest we dive…

Just rebuilt my machine, re-installing everything, most from backups. I had to upgrade in a couple cases, which was costly and not so fun. Just got Art Rage 4 and Photoshop going with all my brushes and settings. Here’s my test to see if it still works the way I like it.

March 23, 2013

The SWitch Kits are in the Post

The kits are on their way! A big thank you to those who signed up to receive wave 1 of the Saltwater Witch Guerrilla Marketing Kits. More info on what’s in each kit here: http://saltwaterwitch.com/blog/?p=1087 . If you’re interested signing up for wave 2, sometime in May or early June, sign up for the Saltwater Witch Newsletter. I will also be giving a bunch of Seaborn stickers soon. Stay tuned!

The kits are on their way! A big thank you to those who signed up to receive wave 1 of the Saltwater Witch Guerrilla Marketing Kits. More info on what’s in each kit here: http://saltwaterwitch.com/blog/?p=1087 . If you’re interested signing up for wave 2, sometime in May or early June, sign up for the Saltwater Witch Newsletter. I will also be giving a bunch of Seaborn stickers soon. Stay tuned!

March 21, 2013

Salvage is a go!

I have some exciting news! I just signed a contract with Masque, an imprint of Prime Books, for my fantasy/thriller, Salvage, the first book in an all new Seaborn series centered on the crew of a marine salvage ship who take on the jobs the big salvage operations can’t–ghost ships that look for prey in the world’s shipping lanes, haunted oil rigs, monsters from the deep who are finding it easier to hunt on the ocean’s surface. The first book, Salvage – Tell No Tales, will be out in July.

I have some exciting news! I just signed a contract with Masque, an imprint of Prime Books, for my fantasy/thriller, Salvage, the first book in an all new Seaborn series centered on the crew of a marine salvage ship who take on the jobs the big salvage operations can’t–ghost ships that look for prey in the world’s shipping lanes, haunted oil rigs, monsters from the deep who are finding it easier to hunt on the ocean’s surface. The first book, Salvage – Tell No Tales, will be out in July.