Ruth Hartley's Blog: Storyteller

August 9, 2025

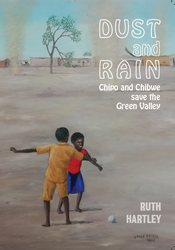

My Grandson, Climate Change, Drought and that Children’s Book

Dust and Rain. cover design by artist Style Kunda

Dust and Rain. cover design by artist Style KundaIn 1993, while sitting in a boat on the Zambezi River floodplain, far north of Mongu, watching the beautiful flights of hundreds of pelicans, I began to make notes and sketches for a book about climate change for my grandson, Stephen Kupakwesu Bush. It was called The Drought Witch. Stephen was 3 years old. It would not be until 2022, after years of hard work editing and adapting it, that the book was published in Zambia by Gadsden Publishers as Dust and Rain: Chipo and Chibwe save the Green Valley. A lifetime later, Stephen is 35 and a successful political journalist at the Financial Times in London. My life has also changed, but my passions for gardening, human rights, art, and my concerns about climate change, Africa and my children and grandchildren have not.

Climate Change: a Recognised Reality for over 50 years

Climate change was a serious concern for me long before 1990. My first book, The Shaping of Water, focuses on the environmental impact of the Kariba Dam. Climate change is not a one-off cause that I selected to write about in this kids’ book. I grew up on farms with my stepfather and father, watching the skies for the first rains to break the drought of the dry season. In 1992, my first husband, Dr Mike Bush, and I attended a medical conference in Canada where a seminar was given by Helen Caldicott, MD, an Australian, whose book If You Love This Planet is about climate change.I knew Silent Spring (1962) by Rachel Carson, and since 1970, I haven’t used pesticides on plants in any of my gardens. I took my daughter, Tanvir, to a permaculture workshop in Zimbabwe in the 1980s and made a permaculture garden in Zambia. Today, I’m watching the heat of a changing climate kill the plants in my garden.

A Bad Woman from a Wicked Past is a Bad Mother

At DB Studios in Lusaka with Peter to make a recording about climate change and my book, Dust and Rain.

At DB Studios in Lusaka with Peter to make a recording about climate change and my book, Dust and Rain.I wrote my memoir, When I Was Bad, primarily for my oldest daughter, but it is for all my kids. When a parent has a disrupted and uprooted life, it is common for the children not to know or understand why things happened the way they did. Secrets and lies can be indistinguishable from each other until the truth and facts are made plain. Divorce, racial politics, the end of colonialism and the liberation wars ruptured my chances of a secure life, so the choices I was forced to make were radical and challenging. Some of these issues are in my short story and memoir book, When We Were Wicked, which is about that past. My family is of mixed heritage, both African and European. It is also multi-ethnic and includes Jews, Muslims, Christians and agnostics. When I started my London life as a single mother in 1966, women were not equal to men under the law, Blacks were not equal to Whites, and there were no guidebooks to life in the future. Few choices are simple to make, and often all that anyone can do is ride the storm waves and try not to drown. We are all subject to unforeseeable and life-changing accidents. How can a parent keep their family safe by ignoring the social, political and environmental problems everyone faces? I’m an ordinary, fearful woman who did her best, but of course, I made mistakes. I wanted to make a good home for my children, but I believed that we had to care for the equality of all people and the planet’s environment at the same time.

The Drought Witch transforms into Dust and Rain

My drawing of Chipo and Chibwe journeying down the Great Zambezi River with Mokoro, their mysterious silent boatman.

My drawing of Chipo and Chibwe journeying down the Great Zambezi River with Mokoro, their mysterious silent boatman.That story is yet another story of how the world changes in ways we can’t control. At St Martin’s Art School in 1995, I learned how to make a children’s picture book, but publishers didn’t think there was a market for a book about African children and climate change then. I wrote sequels to the book. I rewrote the stories as a longer novel and then as a series. The story was rejected for publication in Zimbabwe by women who wanted all the names to be Zimbabwean, a complicated matter to do with meanings, I think. The main character in the original book was named Kupakwesu after my grandson, but as time passed, I wanted his sister to be his equal and a hero too, so the names went through many changes. Finally, I paid for some marketing and literary advice from Cornerstones Literary Consultancy and then sent the story to Fay Gadsden in Zambia. The story was scrutinised for ethnic accuracy, choice of names, as well as quality of writing, until at last it was published as Dust and Rain: Chipo and Chibwe save the Green Valley. I am very grateful to Fay indeed, and I was delighted to go to Zambia to promote the book, as I’ve recorded in several blog posts.

Books, Readers, Sales and Help Promoting Dust and Rain

Chipo saves Chibwe from Kambili, the witch who brought the drought, by spitting the last drop of water from the Zambezi River source at her.

Chipo saves Chibwe from Kambili, the witch who brought the drought, by spitting the last drop of water from the Zambezi River source at her.The main difficulty with my book is its cost for a Zambian child. It is a widespread problem in Africa. There are good writers and enthusiastic readers in Africa, but the cost of a book is still too high in relative terms. There aren’t enough libraries or enough books in them. This subject is currently being researched by my husband, Dr John Corley for his MA dissertation on literature. Environmental and wildlife clubs and agencies want the books, but they need donations to cover the costs. I will forgo my royalties. Please help in any way you can. Buy Dust and Rain. Read the book. Recommend the book. Review the book. Donate the book. Take a journey down the incredible and beautiful Zambezi River with Chipo and Chibwe and help them save the Green Valley and the world from drought and climate change.

June 11, 2025

Paris Noir 1950 – 2000 Black Paris – Artistic Circulations and Anti-Colonial Struggles, 1950–2000

The self-portrait of Gerard Sekoto on my Paris Noir Catalogue

The self-portrait of Gerard Sekoto on my Paris Noir CatalogueI had to see the Paris Noir exhibition. Art and anti-colonialism have always been part of my life, most of which I spent in southern Africa before 1996. I was born in Zimbabwe and studied art in South Africa, but the most significant years of my artistic life were spent working at Mpapa Gallery in Lusaka, Zambia, with Cynthia Zukas, Joan Pilcher and Patrick Mweemba from 1984 to 1994. I had to see what had been happening in ‘Black Paris’ during those years, so I could understand and assess what was the same and what was different from what was happening in the Southern African art world at the time. There are many threads connecting these questions that I will have to explain here before I start to talk about the art. John and I woke up at 4.30 a.m. to catch the flight from our local airport, Tarbes, to Paris for the day because I wanted so much to see the Paris Noir exhibition. It contained so many elements that mattered to me and that I had read and thought about while writing my books, making art and studying for my doctorate.

Gerard Sekoto and South Africa 1948 Pablo Picasso’s drawing of Aime Cesaire for the congress of Black Writers and Writers in 1956 on my book of Cesaire’s poem

Pablo Picasso’s drawing of Aime Cesaire for the congress of Black Writers and Writers in 1956 on my book of Cesaire’s poemPerhaps the first thread is the beautiful Gerard Sekoto self-portrait used to advertise the exhibition. Mpapa Gallery had the good fortune to exhibit a blue painting by Sekoto, a South African artist self-exiled to Paris, that Cynthia Zukas acquired because she felt it was of great importance. Sekoto’s self-portrait had been painted just before the South African nationalists brought in their apartheid state. The expression in Sekoto’s eyes says what apartheid meant for Black South Africans. At the same time, the Jim Crow laws and segregation were in full force in the United States of America whilst in Britain lodging accommodation was advertised stating that no Blacks, dogs or Irish were welcome. In 1948, however, the United Nations declared its promulgation of Universal Human Rights, and Paris became a refuge for Black intellectuals, activists, artists and writers. French and British social and political history are different, even if there were intellectual connections. French and British colonialism and slavery were imposed in differing ways on each African country exploited for the slave trade and colonised. This is not to suggest there is a hierarchy of suffering under slavery and colonialism, despite cultural differences, because all humans resist such abuse and feel the same about it. The fact is that Black exiles in Paris included a wide range of experiences of slavery and colonialism, and had varied political beliefs. That thread is in the next paragraph.

The Congress of Black Writers and Artists 1956This first Congress took place in the Sorbonne in Paris at the time when I had just begun high school. Present at it were Aimé Césaire, Frantz Fanon, Richard Wright, Amadou Hampâté Bâ, James Baldwin, Josephine Baker, Jean-Paul Sartre, Pablo Picasso, Claude Lévi-Strauss, Leopold Sédar Senghor, David Diop, Gerard Sekoto , plus many others from Africa, the Caribbean and America. W.E.B. Du Bois was prevented from participation by the USA government because of his radical views. Many of the participants were descendants of slaves. All believed in Universal Human Rights. Every one of them had an extraordinary life that is worth studying. Please look at the links I’ve provided as they will make clear how wide a range of ideas they represented.. As a political writer, I was fascinated to learn about this congress, as many of them had shaped the ideological struggle against colonialism. I would learn about most of them after I moved to France and I have come to admire them all enormously.

The struggle against colonialism and slaveryResistance to colonisation began immediately, and colonisation was not accepted when early resistance had failed. Resistance in South Africa, Zimbabwe and all African countries grew and developed and was eventually successful. Slavery in Africa and Arabia is however, is a much more complicated story. The truth is that whenever they could, people captured as slaves and sent to the Caribbean and the Americas struggled to escape and be free and to hold onto their own cultures. The ending of slavery is a long and terrible story that took a long time to achieve. Poverty and racism continue today to cause the suffering of Black people.

Art, Culture, Education and the Anti-Colonial Struggle Photo of James Baldwin on the cover of my copy of The Fire Next Time. Baldwin was at the Paris Congress

Photo of James Baldwin on the cover of my copy of The Fire Next Time. Baldwin was at the Paris CongressDuring the Second World War, Félix Éboué, governor-general of the Free French territory of French Equatorial Africa, organised the 1944 Brazzaville conference on colonialism, and some of those present at the later 1956 Congress were there, too. What is well illustrated in both conferences is the importance of the role that artists and thinkers play in the changes needed for liberation and the power of education to help effect that change. I am struck by the universality of human desire for freedom and equality, our need to share ideas and the enormous significance of the role of art and literature. Some of those artists and writers had survived the occupation of Paris, many were poor and their lives were hard, but they fought on for their art and their beliefs.

Paris Noir and African Art My copy of the catalogue of The Neglected Tradition

My copy of the catalogue of The Neglected Tradition Photo of my catalogue of Earth and Everything

Photo of my catalogue of Earth and EverythingLevi-Strauss said there was no difference between the minds of people described by colonialism as “savage” or “civilised”. Jung said that creativity is a human instinct. Pablo Picasso saw in African masks the same driving instinct that propelled his making of art with no distinction. Early 20th-century art history, however, describes African art as “Primitive” and European art as superior, while it mentions no women or Black artists. To remedy this, Steven Sachs produced a catalogue for “The Neglected Tradition: Towards a new history of South African Art, 1930 – 1988” an exhibition of Black art in Johannesburg in the apartheid years. In the Arnofini 1996 exhibition of “Earth and Everything: Recent Art from South Africa”, it can be seen how apartheid affected artists. Educated Black artists, making contemporary art critical of apartheid, went into exile. White artists stayed, and some Black intuitive artists were accepted by progressive galleries. Realising the transformative power of art, Robert Loder worked with David Koloane in Johannesburg. He encouraged art in Zambia and started the Triangle International Artists Workshops which are documented in “Making Art In Africa 1960-2010” edited by Polly Savage.

Paris Noir and Zambian ArtNo complete account of Zambian art exists, and perhaps it can never be made. There are huge gaps in our knowledge of it at this time. What was recognised at Independence in 1964 was the importance of art to a nation’s vision of itself in the exhibition arranged by Simon Kapwepwe. What was needed was the visionary artists who wanted to see Zambian art grow and develop, artists who did not simply make their own art but opened the doors to art for Zambian artists. Foremost among the visionaries in the early years were Henry Tayali, Cynthia Zukas and Bente Lorenz. All three continued to work for these ends until their deaths, and all were involved with the formation of the Lechwe Trust Art Gallery in Lusaka. Henry’s passionate contribution was to fight against the sanitisation of African art for the tourist trade, while making his powerful political paintings about the fight of people for freedom from oppression and poverty. Cynthia worked tirelessly to encourage artists to make art, particularly printmaking and etching, as well as making art herself. Bente believed in and understood both the need for creativity in every human, but also their innate ability to make art. She kept this certainty alive at the heart of all she did. All three worked with and for art societies, also suggesting artwork for the National Art Collection.

Paris Noir and Mpapa GalleryIn 1978 Joan Pilcher and Heather Montgomerie opened the Mpapa Gallery. Their ambition was to show very varied work of a high standard, if possible from international artists, as well Zambian artists. Over 50 years later it will be difficult to understand how little there was to support Zambian artists then. There were no galleries. the art materials shop had closed. The Evelyn Hone art department had closed and art teachers had minimal art history education. The Zimbabwe liberation war continued and the South African liberation war was intensifying. Life in Zambia was difficult, goods and fuel were in short supply and there was almost no market for art at all. The colonial art legacy was of watercolour landscapes and wildlife paintings. Senegalese and Congolese art “masters” shared their knowledge. Traditional African sculptures prized by tourists could be found, but were not authentic. The Zambian economy was 90% informal. People only wanted to make art to earn a living and duplicate paintings were made and copied. Nobody in the world seemed interested in Zambian art or artists or even in Zambia itself. When I joined Mpapa in 1984 it was a challenging time, but I was helped by Patrick Siabokoma Mweemba, Style Kunda, David Chirwa and Lutanda Mwamba. We had a lot to learn. We needed to sustain and develop creativity and high professional and ethical standards in making, selling, and exhibiting art. That was what was wonderful about the Paris Noir exhibition. I saw that we were comrades and contemporaries with the same desires and passions and creative abilities. What we all did and what we all do is make art and help other artists make art.

May 22, 2025

Afrikaners

Trump’s appalling behaviour towards President Cyril Ramaphosa in the White House yesterday has created a storm of different opinions about it in the papers and on Facebook. What Trump and Ramaphosa have in common is no knowledge of art. Trump showed an art installation of white crosses (not graves or on graves) that selectively mark only white deaths in South Africa. Ramaphosa knew nothing about it. The art installation can be found on the Bittereinders website. The Bittereinders (the Irreconcilables) are still fighting the Boer War that ended more than 120 years ago. Trump and his Proud Boys want to go back 160 years to when only Whites had power in America. On the racism score, Trump and Ramaphosa have nothing in common.

A silly story told by an Orange ManAccording to Donald Trump, Afrikaners are a persecuted minority in need of rescue by him in return for their support for his MAWA (Make America White Again) agenda. Trump neither knows nor understands the history of the Afrikaner people. South Africa does suffer from too much poverty, criminal violence, and murder, but it is not specifically against white people. Poverty and violence are linked and are post-apartheid problems in South Africa and post-colonial problems in other African countries. Julius Malema, leader of the small EFF, after being thrown out of the ANC sings ‘Kill the Boer’ (Kill the farmer), an old anti-apartheid war song, which may be considered hate speech but is allowed in South Africa as free speech. Many ex-freedom fighters in South Africa reject Malema’s racism. It is not what they fought for. There were, and are, anti-apartheid Afrikaners. My list of those great and brave Afrikaners is in this blog.

Bram Fischer.https://www.nelsonmandela.org/news/entry/bram-fischer-a-hero-born-100-years-ago/Resistance to Oppression

Bram Fischer.https://www.nelsonmandela.org/news/entry/bram-fischer-a-hero-born-100-years-ago/Resistance to OppressionThe simplistic use of the terms ‘colonialism’ and ‘post-colonialism’ also ignores the complexity of South African literature, visual arts, and resistance to the apartheid regime. Anti-apartheid and resistance movements against oppression began inside South Africa before it was officially noticed. It is also true that oppressive ideas and habits do not immediately disappear with a regime change. Afrikaners are no different to any other group of people on our planet. Like all people, many think for themselves. The best reject oppression, not only for themselves but for us all.

Martin Versveld, my Professor of Philosophy Cape Town UniversityAn Afrikaner Story

Martin Versveld, my Professor of Philosophy Cape Town UniversityAn Afrikaner StoryAfrikaners are mixed-heritage Africans descended from the farmers of the first 1652 Dutch settlement in the Cape region of South Africa, which provided refreshment posts for the Slave and Far East Trade. The Dutch had not planned to colonise Africa then, they simply stayed on along the Cape coast. The British, however, took charge of the Cape Colony and ended first the Slave Trade in 1807 and then slavery itself in 1833. To escape British dominance and the end of slavery, some Afrikaners made the Great Trek north from 1835, where they set up two republics and lived as subsistence farmers dependent on slave labour. African tribes of that time also took, traded and used slaves.

A story about slavery in South Africa by a great novelistPopulation and Language

A story about slavery in South Africa by a great novelistPopulation and LanguageAccording to research, by 1867, the Afrikaner population was a mixture of Dutch, German, French, People of Colour, British, Unknown and Other Europeans. They identify as Africans, however, and recognise no other home. Today South Africa recognises 12 different languages, and after Zulu, Afrikaans is the most spoken. Most Afrikaans speakers are Coloured and Black South Africans in the Cape and Gauteng provinces. Like Afrikaners, Afrikaans is an African mixed-heritage language, perhaps first written in Arabic script by Muslims. Afrikaners were devout Christians, but many were illiterate and had to have their Bibles read to them.

An artist, writer, poet and prisonner, Breten Breytenbach opposed apartheidThe Boer Wars 1880-1881 and 1899-1902

An artist, writer, poet and prisonner, Breten Breytenbach opposed apartheidThe Boer Wars 1880-1881 and 1899-1902The Boer Wars fought by Afrikaners against the British may be described as anti-colonial wars. To prevent food supplies reaching the Boer commandos, Afrikaner women and children were imprisoned by the British in concentration camps, where they died in substantial numbers because of poor hygiene, dreadful prison conditions and typhoid. The result of the Boer Wars was increased poverty for Afrikaners. A few Afrikaners, the Bittereinders, were never reconciled to British rule and sided with the Nazi regime in WW2. Others like General Smuts fought for the British.

Antjie Krog – poet and writerThe Apartheid Regime

Antjie Krog – poet and writerThe Apartheid RegimeIn the 20th Century, British settlers and Afrikaners distrusted and despised each other, a legacy of the Boer War, but also because of apartheid politics. Defining apartheid as oppression by colonists is questionable, as South Africa was an independent Republic by the time apartheid was law. This is not to deny its appalling racist treatment of Black South Africans, but to show how complicated history can be. Apartheid may be better understood as a power grab by a White African tribe of separatists in a country of many different tribes. It was also revenge after a failed war of Independence against English-speaking colonists by people who were Africans or Afrikaners.

J M Coetzee. Nobel Prize for Literature.Colonial and Post-colonial Confusions – The Liberation War

J M Coetzee. Nobel Prize for Literature.Colonial and Post-colonial Confusions – The Liberation WarThe liberation war of South Africa was fought between South Africans, as it was not about expelling outside invaders. It can be described as a civil war complicated by the Cold War. Russia and Cuba supported the liberation army while Britain and America supported the apartheid and Western-leaning government.

A man of extraordinary thoughtful intelligence.

A man of extraordinary thoughtful intelligence. C Louis Leipoldt, a man of compassion and insight

C Louis Leipoldt, a man of compassion and insight A wonderful account of food and cookery in the early days of the Cape.Colonialism and Post Colonialism

A wonderful account of food and cookery in the early days of the Cape.Colonialism and Post ColonialismIn Africa, the historical change from “colonialism” to “post-colonialism” is seen as a moral improvement and a social evolution. The term ‘colonisers’ has become conflated with white-skinned people and is used as a propaganda tool in the analysis of evolving political situations. This tidying-up of history can also create falsities in understanding the complexity of South African tribal history and society. Colonisation began with the Slave Trade and the Far East Trade, but the end of slavery in Southern and East Africa was also a result of colonisation. David Livingstone, missionary turned explorer, foresaw that the Arab Slave Trade in East Africa would only end with colonisation.

A Human ActivityColonisation is common to all life forms on our planet, and it drives them to move to new environments that will continue to feed and sustain the life form when necessary and while possible. Human colonisation happens after a population increase or a change in food supply, trade or climate, but colonisers need to have the ability to colonise through technological mastery of transport and weapons if they are to succeed. Life forms may migrate rather than be forced out by predators. Colonisation and migration occur as a response to circumstances and accidents. It may be sensible not just to see colonisers as bad and the colonised as victims but instead to understand how and why we can change human behaviour.

Andrew Verster was my best art tutor at the Michaelis School of Art in Cape Town

Andrew Verster was my best art tutor at the Michaelis School of Art in Cape Town

May 10, 2025

Storytelling on the Borderlines of Colonial and Post-Colonial Literature

I have been working towards a doctorate about storytelling and this blog is part of my thesis.

Storytellers and artists both entertain and to help us survive by making sense of our lives and world. All stories follow similar patterns of a quest, a passion, and a mistake, followed by a resolution or acceptance of fate, as JD Salinger explained. Poetry and singing arise from the rhythm of heartbeats, breathing and the metre of footsteps. They are part of our physical nature and prove we are alive. We do not know who we are or why we exist in time; all we know for certain is that in the future, we are dead. Our quests are attempts to discover why we exist, and storytellers, singers, and poets are our voiced desires for meaning.

Glory is NoViolet Bulawayo’s second novel.Borderlines

Glory is NoViolet Bulawayo’s second novel.BorderlinesHumans live on borderlines that keep changing, and this state of flux is illustrated by the study of literature and art as the weapons and tools that shape our present perceptions. Storytellers may be seers, foretellers, or myth makers, needed because factual self-knowledge is difficult to attain, and reality can seem unbearable. The importance of storytellers is that they make the present endurable even when recounting the unendurable. Storytellers and artists turn present pain into present art.

Three of the books that are considered in my thesis. They are The Love and Wisdom Crimes, The Shaping of Water, and The Tin Heart Gold Mine.

Three of the books that are considered in my thesis. They are The Love and Wisdom Crimes, The Shaping of Water, and The Tin Heart Gold Mine.The four books that are the basis of my doctorate were written during or soon after the events they describe happened. They are grounded in the confusing interactions of our human experimentation with patriarchal, colonial and post-colonial human systems. Historians, academics and critics come after the events to analyse, categorise, label and judge what happened in the past. That may create new myths based on perhaps on patriarchal power. NoViolet Bulawayo says of her book, ‘We Need New Names’ (2013), that it is not enough to switch power from men to women or colonial to post-colonial systems; we need new ways of living and being human.

Understanding political change Olufemi Taiwo has an interesting view of Decolonisation and African Agency

Olufemi Taiwo has an interesting view of Decolonisation and African AgencyI believe that storytellers play a more significant role in helping us to understand political change, such as colonialism and post-colonialism, than we will learn by studying the plans and promises of the politicians of the same era with the analysis of past events by historians who were their contemporaries. It may also be true when we look at the analysis of the events resulting from the actions of those politicians by the historians who postdated them. Of course, all these things become muddled together and work both against and with each other. Conspiracy theories, myths and propaganda are all “stories” used for subversive political motives to fulfil wishes and cause political disruption.

ImaginationHuman reason is creative, imaginative, and playful regarding time and place. Humans may claim rationality in their search for factual knowledge, but facts and fiction, reality and myth, truth and invention, together with human nature, have a shifting relationship that art, poetry, and stories constantly reorder to make human society function. As Camille Paglia says, “Incarnation, the limitation of mind by matter, is an outrage to imagination.”Humans refuse the limitations and do not act on known facts alone but on the stories and myths they invent as well as those that are invented for them by storytellers. We need and use stories to help us to survive.

Keeping us from evil According to Jonathan Gottshall humans and animals who tell stories.

According to Jonathan Gottshall humans and animals who tell stories.Stories, however, told, as books, films, art, theatre, music or installations not only pleasure us, but exorcise evil and act as intercessors in uncertain futures. Jonathan Gottshall says, humans are storytelling animals and author Philip Meyer says in his book ‘American Rust’, that “Art has eclipsed the Real”. We need stories and storytellers.

December 19, 2024

Grandmother’s Sandwich Story

Sandwich stories by columnist Stephen Bush, was in the Financial Times last week in response to Kemi Badenoch’s Spectator statement that she doesn’t eat them. Somehow Grandmother was mentioned, too, so Grandmother determined to write her own stories about sandwiches – here they are. Read at your peril if you don’t eat or do eat Bread.

Padkos or Road FoodSandwiches are a food you can eat while marching off to war – or to anywhere. Sandwiches are Padkos, the Afrikaans term for Road Food, but their English name comes from the Earl of Sandwich who ate one while gambling, so he that didn’t have to stop. Sandwiches of matzo and bitter herbs are part of the story of Passover and were eaten when Grandmother made Passover meals for her children. Passover bread – matzo – was road food eaten in on the biblical journey from Egypt to Palestine. Bread is the edible packet that holds the nourishing protein anyone needs to live, however white bread has very little food value on its own and it doesn’t keep like wholegrain, rye and brown breads do.

Grandmother doubts that the first sandwiches were made of fresh or white bread. Grandmother’s preferred Padkos is biltong, bananas, nuts, dried fruit and delicious mebos. Grandmother prefers to travel with Padkos, water, fuel for the car, and shoes that she can run away in, because that’s how it had to be until she was fifty years old. Grandmother also loves Pita bread and Naan – both bread envelopes that hold real food from food cultures that she enjoys.

Passover family meal with guest Bornie BornsteinNo Sandwich Shops

Passover family meal with guest Bornie BornsteinNo Sandwich ShopsGrandmother’s generation did not buy sandwiches, because there were no sandwich shops or fast food. Pizza – a flat one-sided version of a sandwich – was not available, either. The Grandmother’s mother made sandwiches for her school breaks, as did every mother who could afford bread, and spread it with homemade jam or peanut butter. Grandmother’s mother sold bread in her African store and Grandmother, locked into the suffocating, dark and dusty back of her parent’s tiny Austin van nibbled at the bread crusts to stop feeling carsick on her windowless journey back from school. Grandmother, the artist, later made a drawing of this journey for an installation about her colonial history.

Drawing of my parent’s Austin van on a dusty road, made for my installation about colonial history.School Sandwiches

Drawing of my parent’s Austin van on a dusty road, made for my installation about colonial history.School SandwichesGrandmother at boarding school with other girls, who are probably grandmothers or dead, ate as much brown bread spread with margarine as she could get at supper because the girls were always hungry for home and for food. In the winter they sneaked the bread and marge out of the dining room and toasted it greasily on top of the paraffin heaters in the prep room before the teacher appeared. Bread came in a square white loaf at home and seemed a luxury. A Dagwood sandwich tower was an American greedy joke and has since degenerated into a MacDonald’s Burger that is not good or food – just body filler-outer. Of course, that’s just her opinion! Manger et bouger is not a French life style yet and is why the French are slim and fit.

Bread and Meat Upper Constitution Street, District Six, 1965.

Upper Constitution Street, District Six, 1965.Grandmother as a teenager did Red Cross and was told by a health worker that African workers and maids ate buns and addictive Coca-Cola and fed it to their children because it was all that was available and cheap, but it was such poor nutrition that it made them vulnerable to tuberculosis. Grandmother learned at university that poor people on the Cape Flats could not afford nutritious food and fed their babies cooked pumpkin squashes. Grandmother knew a doctor who worked in Baragwanath Hospital in Jo’burg in apartheid days who told her that maize meal has no food value unless it has a protein accompaniment and the poor women who ate only mealie pap became huge and swollen, but had no strength. Bread eases hunger, but does not feed one’s body so Kemi may be right to disdain the outside of a sandwich, but Grandmother asks – does her steak come on a plate that requires washing by a staff member? Grandmother loved to make and devour a Hunter’s sandwich, which is a disemboweled loaf of fresh bread stuffed with a juicy peppered steak and garlic mushrooms. It is picnic food and doesn’t need a plate. Grandmother hates soft sandwiches filled with pale battery chicken or ham, processed salad creams, flavourless tomatoes and limp salad. Even that onetime gem, a BTL is longer tasty as it used to be. Sandwiches are costly in every sense.

Bread and Roses

Grandmother is a feminist who believes in Bread and Roses and first saw those words graffiti-ed up on the De Waal motorway in Cape Town in the ’60s. She believes that bread must be good bread. The now traditional French baguette was an invention designed to be mass-produced for the hungry (masses of course!) in about 1920. Before that, people had eaten round, hard loaves of black bread that took too long to make and bake. That’s why bakeries in French are called ‘boulangeries’, because the bread came in ‘boules’ or round loaves. The steam ovens used to bake the long white light and transportable baguettes provided almost instant food and so helped prevent the bread riots, that most common cause of revolutions and war.

Breaking BreadGrandmother loves the breaking of bread together as a family that is a sacrament for so many peoples. It is also a time to share memories of where a family comes from – what makes us into the people we are – and it helps us understand each other. Refusing to break bread and share it together is to side with the dividers, warmongers and destroyers of hope and humanity. Grandmother is forever grateful to her mother and father who did not disown her for her politics or the harm she did them. Brave people!

Grandmother’s family notes – her family is one of many mixed heritages, one race and multiple migrations – it is German and English, Russian and Polish, Indian, Indonesian (Malay), African, Shona, British and French. She advises that generation, class, culture, religion, politics, education and tribal affiliations are ways to either join or divide families and she wonders what bits, or which wholes, might be selected to be cancelled and cut off. What riches and tragedies could be lost instead of being courageously and lovingly sustained as Grandmother’s parents did.

October 4, 2024

Food, Family and Love

Yesterday I was driven to look at my wonderful collection of cookbooks. I did so because I was furious. I had something to prove, and I knew the answer would be in my kitchen on the shelf above my bread board, kettle and toaster. (I’ll tell you what made me angry later in this blog post – perhaps you’ll guess by looking at the photos.)

Food keeps us alive

Food keeps us aliveWe eat to live but most important of all food is about sharing and sustaining love, families, kinship and friendships. I still believe in saying grace, but as an agnostic I don’t thank a God – I thank the providers, the cooks, and the farmers and gardeners. Our daily bread matters – we break bread together. We offer hospitality to strangers, we feed the poor. Sharing food is the giving of love. It starts with the newborn baby at the breast – it ends with spoon-feeding those too ill and too old or weak to feed themselves.

Sharing food around the worldIt is true that we now eat mass-produced processed food grown in ways that contribute to global warming, climate change and obesity, but that will have to be written about in another post. What is important in this post is the way that humans have shared plant crops and staple foods around the globe for very many centuries and not only that, but they have also shared both recipes and ingredients. Pepper and spices were brought from the East to preserve food in Europe. Pasta came to Italy from China, the inventors of noodles. Fish and chips came from Portugal. Potatoes came from America. Maize meal was brought to Africa by the Portuguese – maize meal is a poor substitute for sorghum and millet, though.

Local foods and celebrationsIt is true that the food we grow is dependent on its regional locality, on the climate, on water, on earth and insects. That is what has made flavours and crops specific to cultures and regions. We celebrate the end of Ramadan with a feast of Eid, we celebrate Christmas with cake and roast meat, Easter with eggs, Passover with stories, bitter herbs and the shank-bone of lamb. Humans, though we are made by tradition and family, are also migrants, wanderers, travellers, tourists, explorers and hospitable sharers. We love to taste new foods, share other customs and invite people into our homes.

When I looked at my cookbooks this is what I foundFalling Cloudberries by Tessa Kiros – A family of several different nationalities journey from Scandinavia, through Greece to South Africa gathering their traditional recipes.

Mother Knows Best by the Hairy Bikers – A book of recipes from many British mothers.

Cape Cookery inspired by Indonesian and Afrikaans culture C Louis Leipoldt.

Moro, a book about North African and Spanish food written by Sam and Sam Clark.

French Cooking A famous book by Julia Child, an American.

A Book of Jewish Food from every place in the world where there were Jewish communities from Samarkand and Vilna to the present day by Claudia Roden.

Middle Eastern Food from Algeria through Egypt to Arabia and Iran also by Claudia Roden.

A Taste of India from across all the different cultures of India both vegetarian and meat recipes by Madhur Jaffrey

All of these books were written with love and written to share wonderful foods around the world.

Serve good facts (food) not a hash of liesWhy was I so angry that I wrote about love, food and family? I came across an antisemitic post on Facebook written to arouse hatred of Jews. It claimed that Israelis stole a food recipe from Palestinians. As you can see if you read my post that is not possible. Most Jews in Israel are Mizrachi, over 60% are Middle Eastern people who originated in the Middle East. Their foods are shared among Middle Eastern people. We, who are English or French or German share and prepare foods from other places even if we love our own food most. Where does your food come from and how much food have you adopted from other cultures? Antisemitism is based on lies and falsities . Make judgements – that is what we humans do – but make your judgements on facts, not falsities and don’t be one-sided. Yes – we may all choose one side or the other based on our situation, need and family but that doesn’t have to make us one-sided – both sides are human. Do you want to go to war or stop war? If you don’t want war then be kind and be fair.

September 15, 2024

Kariba Dam, Climate Change, Hydro-Power, Agriculture and Water

There is a huge and important news story to be told about climate change that affects the whole of sub-Saharan Africa and therefore the world. I have been shocked today to watch a video of a man walking across the Zambezi from Zambia to Zimbabwe without the water reaching his knees. This is somewhere I often went camping, boating and fishing. I found this terrifying.

HistoryKariba Dam was a political act by colonial powers planned to hold together the short-lived Federation of Central Africa that lasted ten years from 1953-1963. In 1957 it was said that the dam wall would last 200 years. It is already having monumental repairs to stop it being undermined.

Rainfall

RainfallHuge bodies of water affect and change the climate by their existence which acts as a barrier and enforcer to rainfall. Research work is being done on this at universities. The dam has affected the environment downstream causing soil erosion and adding to the enormous flooding in Mozambique. Climate change largely driven by the industrialised nations of the West and Northern hemisphere has resulted in the failure of the Inter-tropical Convergence Zone rains reaching Zambia and Zimbabwe in 2023-2024. The resulting drought, despite good actions on sustainable agriculture by remarkable people and organisations, is starving people who practice subsistence farming. Kariba Dam is fed by rainfall in the Democratic Republic of Congo that arrives in Zambia’s North-Western Province as the source of the great Zambezi river on which Kariba Dam in built. To understand the importance of the Zambezi River and the dangers of drought read my climate change book for children published in Zambia by Gadsden Publishers and titled Dust and Rain, Chipo and Chibwe,Save the Green Valley.

Hydro Power The review of my book the Shaping of Water by Daniel Sikazwe. Daniel says that the book is an important documentation of early Zambian History.

The review of my book the Shaping of Water by Daniel Sikazwe. Daniel says that the book is an important documentation of early Zambian History.Kariba Dam’s water levels are so low that the generation of power is severely limited. Kariba operates on a shared electricity grid with all the surrounding nations. In cities like Lusaka people have no power for days at a time. This means fridges can’t preserve food, and cooking can’t be done except with damaging solid fuels like charcoal. Education, hospitals, governments are all adversely affected. Cutting down trees caused by the need for charcoal further increases climate change. So many people in Zambia work hard to replant trees and encourage sustainable farming. Their important work may not survive climate change without political change in Europe, America and China. This is a global concern with global effects caused by post-colonial and Neo-colonial exploitation of industrialised nations.This story must be fore fronted and told urgently right around the world.

Lake Kariba from the cottage that my book The Shaping of Water is centered on at Siavonga in Zambia.Information

Lake Kariba from the cottage that my book The Shaping of Water is centered on at Siavonga in Zambia.InformationThere is important background material in my book, The Shaping of Water. about the Kariba Dam and the liberation wars around it before the 1990s. An authentic visitors’ book at a Kariba lakeside cottage provides the theme on the lake environment and its water levels .

There are many other books on Kariba

Ethnography studies . Dr Elizabeth Colson The Social Consequences of Resettlement.

Jonathan Waters Kariba, the Legacy of a Vision.

August 9, 2024

The Mpapa Gallery: Lusaka Zambia 1978 – 1996

It is done. Published this year 2024 and delivered to Zambia where Lechwe Art Gallery has generously and efficiently distributed copies to those artists and creative people connected with the Mpapa Gallery or wishing to research a part of the history of Zambian art. We have been sending out PDF copies to people who are requested copies but cannot get a hard copy. The Mpapa Gallery Monograph is also available on Kindle from Amazon. All the past directors have contributed to the Monograph from Joan (Pilcher) Jenkin who started Mpapa with Heather Montgomery, to Patrick Mweemba Siabokoma, Cynthia Zukas and myself, Ruth (Bush) Hartley who managed it until it closed.

The Mpapa Gallery Zambian artists at my home including Godfrey Setti, Style Kunda, Shadreck Simukanga, Patrick Mweemba and others

Zambian artists at my home including Godfrey Setti, Style Kunda, Shadreck Simukanga, Patrick Mweemba and othersThe Mpapa Gallery was begun by people who were passionate about art and positive about the newly independent country of Zambia. So too, were all the people who connected with the gallery as artists, art enthusiasts, art collectors, art advisors, funders and supporters, workers, managers, visitors and friends. Art galleries almost never make any money so they are usually run as charities with endowments. Above all, it is the creative people and artists who make it possible. All forms of the creative arts are the life-blood of every nation.

A personal account of the history of Mpapa Gallery Cynthia Zukas and me in London in 2023

Cynthia Zukas and me in London in 2023Mpapa Gallery closed done in 1996 and that is 28 years ago – more than a whole generation has grown up since then and a great deal of the history of that time in Zambia is lost and forgotten in part because it was a pre-digital era but also because Zambia like so many African nations suffered the cataclysm of the HIV/AIDS pandemic. In 1996 I suffered the personal tragedy of a forced rupture from Zambia, the place that was home to me and my heart and work but I’ve never stopped being deeply engaged with art and with Zambia and Zambian artists since. That can be clearly seen from the blogs I have written and also from the art I’ve made and the personal contacts I’ve kept up. When I left Mpapa Gallery, I left behind all the information to do with the gallery but fortunately I also copied some of what I thought was most relevant and I kept it as safe as possible. Just as well as it turned out because my personal art and other information was deliberately trashed when I left Zambia and so writing this Monograph has required effort and dedication from me. I am glad and happy that I’ve been able to complete it.

People who helped make the Monograph possible

I’m grateful to everyone I mentioned by name or alluded to to above. I’m extremely grateful to my husband and friend John Corley who has given me every encouragement and made things happen that I could not have managed – thank you John! I’m also grateful to Joel Bossieux of Alize Photographics. Joel has made art catalogues for my art exhibitions and flyers for my books and novels. He always goes beyond what he should do to run an economic business and yet he continues to smile at me. He is very kind and a digital whizz. It was Joel who somehow took the Monograph, squeezed and shaped it into a book that could be published and found a publisher who could deliver it in time for Cynthia Zukas to take it back to Zambia and with the help of Kulamitra Zukas get it distributed at the Lechwe Gallery.

The Tin Heart Gold Mine

It is entirely appropriate to plug my book The Tin Heart Gold Mine here. Picasso said that “art is not made for decoration. It is an instrument of war for attack and defence against the enemy.” I find that true though art does not kill and main and enslave as European wars did to Africa. My book, set in a fictional country like Zambia, is about those European wars, about the necessity of wildlife and the corruption of gemstones, about the importance of love and the battle to make art that changes perceptions.

My Body of Art – Corpus Untitled drawing in charcoal 1993

Untitled drawing in charcoal 1993I always thought that the personal is political and my personal art is political. It’s not a choice but a fact of life. I learned more about making art from the time I spent with artists in Zambia and at Mpapa Gallery than I ever learned at art schools but I did have inspiring teachers who made me realise that nobody teaches another person how to be creative – all you can do is open doors in hearts and minds and encourage curiosity, critical thinking and problem solving.

Please contact me here for information about the Mpapa Gallery Monograph or visit the Lechwe Gallery in Lusaka Zambia. Copies are available on Amazon Kindle or on PDF by request.

August 6, 2024

Glory

Glory by NoViolet Bulawayo

Glory by NoViolet BulawayoNoViolet Bulawayo’s remarkable satire Glory, about Zimbabwe was shortlisted for the Booker Prize in 2022. I can’t recommend it highly enough. As well as being a very good read. it is a skilled, literate, well researched and detailed account of the last days of the murderous Robert Mugabe, the Founding Father of Zimbabwe and the start of the reign of the Killer Crocodile. It is also a gripping story about so many extraordinary “Jihadadan” characters who are simply the ordinary people of Zimbabwe. In Glory they are given their voices – so many different and differing voices – all such human animals.

NoViolet Bulawayo and Zimbabwean writersI follow Zimbabwean writers and always I start with some trepidation because of my colonial heritage and childhood in Southern Rhodesia. I expect to feel pain, shame and guilt heaped on me for my past. It’s not my fault perhaps as all our histories are about complicated responsibilities, memories, actions and reactions. I’ve written a memoir about this time of my life but it’s not in any way to excuse myself. Perhaps all writing is at some level a mix of confession and therapy. Maybe I write to assuage the pain and place myself in a disordered rejecting and rejected world. I was very impressed with NoViolet Bulawayo’s first novel – We Need New Names but that is another story and a new post. So too will be the post explaining why there’s been such a long gap between this post and my last one.

Glory – a glorious story Glory and When We Were Wicked in my reading corner in the fig tree in my garden

Glory and When We Were Wicked in my reading corner in the fig tree in my gardenWhen I say this is a well-researched book I in no way mean it’s academic or authoritarian in tone. Far from it. It’s a great story. What I mean is that NoViolet Bulawayo knows every detail of Zimbabwean government corruption and oppression. She understands the African context in which Zimbabwe is situated and she is writing about the people she knows intimately in Zimbabwe. She writes with her own flesh and blood, knowledge and pain and is I believe taking a huge risk with her own life in satirising the Killer Crocodile. I hope I’m wrong and she suffers no harm because of this book.

Zimbabwean history and me My book in which the last memoir Useful Martyrs about the Gukurahundi massacres is published.

My book in which the last memoir Useful Martyrs about the Gukurahundi massacres is published.I witnessed the Zimbabwe Liberation War from inside Zambia and I also went to Zimbabwe for the 1980 inauguration of Robert Mugabe as President. I was delighted at first by feelings of hope and reconciliation. I understood that there would be difficult issues about land ownership that would be hard to resolve. I even benefited from some of the currency changes in the 1990s but I grieved when I saw the increasing poverty, suffering and oppression of Zimbabweans. It isn’t possible to know exactly or even partially how history is unfolding around us. It is only when we look back at history that we begin to understand what shaped it and the part we played. We suffer events and learn later that it needn’t have been that way. Then there is the terrible Gukurahundi – the theme that cuts to the heart of Glory.

Gukurhundi – the Ndebele massacres 1983-1987The year before Bulawayo published Glory, I published When We Were Wicked, a book of short stories and two brief memoirs one of which tells how the Gukurahundi affected my mother and my family and me. That means that Glory is a book that is very personal for me even though my family did not suffer the horrors that Bulawayo’s family and Bulawayo and the Ndebele did. To research and understand the Gukurahundi massacres you can read the report by the Catholic Commission of 1997 on the subject. There is also a very detailed book about Mugabe and Zanu by Stuart Doran called Kingdom, Power, Glory.

Us – the Human AnimalsWe are all animals. This is something that Africans understand and embrace in their various timeless yet always contemporaneous cultures. The idea that Bulawayo is following George Orwell’s Animal Farm is nonsense because Bulawayo is writing an African story using African traditions and voices that originate a few thousand years before Orwell and probably before Aesop’s Fables. I can hear the pitch of people’s voices from the way Bulawayo writes. Yes – her book is very funny and racy too but satire always has a dark heart that cuts to the centre of our lives. Bulawayo knows too well that the corruption that supported Mugabe and supports the Killer Crocodile is world wide and deep as human history. It is your story too. Read it – it is brilliant.

June 21, 2024

The Shoah and the Confusions of Warring

The 1987 Kubrik film Full Metal Jacket stars Matthew Modine as Private Joker, an American soldier fighting in the Vietnam War. Netflix removed BORN TO KILL from his helmet and destroyed the film’s theme of the duality of human nature. Next to BORN TO KILL was the symbol of peace Private Joker’s statement about his war. This is like the human dilemma we face over the Gaza War. We will not help the Palestinian people by supporting Hamas. Hamas is an army of jihadis from many nations not just Palestine. who care so little for Palestinian women and children they use them as human shields, eat their food, and refuse a ceasefire. Jihadis murder writers like Salman Rushdie, publishers, cartoonists, civilians and people at music festivals like the Bataclan, Charlie Hebdo, and the Manchester Arena. Why we must ask. Can we help Palestinians by killing Jews anywhere or by driving Israelis out of Palestine and chanting from the River to the Sea? What can we learn? What can we understand? What can we change?

At the War MemorialOn May 8th 2024 Armistice Day at the War Memorial in our little village in France, our mayor, Robert Maisonneuve spoke about the rising anti-Semitism in Europe and he reminded us of the Shoah, the Nazi genocide of Jews in Europe. It took place less than a century ago right here, where we live, in civilised industrialised Europe. Do not forget this atrocity Mr Maisonneuve warned. Forgetting the dangers of anti-Semitism is a real threat to our peace, our democracy and our humanity.

Death StatisticsConsider these statistics. Between 5 and 6 million Jews were exterminated. Almost 3 million in Poland in the death camps alone. That was 50 % of European Jews and 40 % of world Jewry. Jews were murdered for trying to return to Poland after the war. Millions of displaced people had to find new homes and no country wanted any of them unless they had money. We all want to return to our roots, to where we belong and hope to be safe. It is estimated that there are 15 million Jews worldwide, over 8 million in the tiny country of Israel. Compare those figures to the size of Muslim countries and Muslim population. Muslims are responsible for most Muslim deaths.

Defeat and VictoryOn 8th May 1945, Germany surrendered to the Allies but victory is not erasure says Sebastien Lecornu, Minister for the Armed Forces in France. The French had been defeated in 1940 and had to cope with betrayal by their own people. The courage to resist comes at a high personal price and most people cannot or will not make that sacrifice. Those who do, being human, may have mixed motives, may make bad decisions and cannot count on good results. After a victory or a revolution, we claim that we were always brave and on the “right “side but were we and can we carry on being right? We want to be as good as we can be in the situation we find ourselves in but making the world into a place where we can all be good seems inachievable. Labelling others as bad or evil is easier than admitting we might be mistaken and revengeful.

Learning from our heritageLecornu ends by saying that commemorating the end of the war is nourished by both the history of the Free French and the Resistance and by the history of deportation and collaboration. Those opposing memories are our heritage and our lessons. According to Antoine de Sainte-Exupery –“The truth of tomorrow feeds on the mistake of yesterday.” but perhaps the truth of tomorrow is born compromised and if we can recognise that we can be wiser and kinder. The war stopped in 1945 but it did not finish. It left an enduring legacy of pain, suffering and wrongdoing and continues as a war for understanding, compromise, tolerance and forgiveness without which there can be no peace.

Wars against WomenFull Metal Jacket ends when Private Joker sees that the sniper he has hunted is a young girl. He kills her. It is a disturbing film. Ironically the war scenes in Full Metal Jacket were shot on an abandoned gasworks site in east London close to areas that were heavily bombed in WW2. Rape is a weapon of war used by Hamas on October 7th. It is used by men in every war. Child marriage, banning education for women, contraception and abortion for women are also weapons of war. Hamas, the Taliban, Boko Haram, Al-Shabab, Al Qaeda, and Hezbollah use these weapons of war against their women now, today at this moment. Shockingly these weapons are used by followers of Donald Trump in the USA. The war that has to be won is not a war against Muslims, Jews, Christians, theists, atheists or agnostics. The war that we must win is against misogyny.

Night and FogA song written by Jean Ferrat, son of a Russian Jewish emigre murdered in Auschwitz was played at our War CommemorationThey were twenty and a hundred, they were in thousands,

Naked and wan, trembling, in sealed wagons,

Who tore at the night with their fingernails,

They were in thousands, they were twenty and a hundred.

They believed they were men, were nothing but numbers. . .

ls étaient vingt et cent, ils étaient des milliers,

Nus et maigres, tremblants, dans ces wagons plombés,

Qui déchiraient la nuit de leurs ongles battants.

Ils étaient des milliers, ils étaient vingt et cent.

Ils se croyaient des hommes, n’étaient plus que des nombres.