Oliver Lee Bateman's Blog, page 3

April 22, 2015

Pedro Guerrero

“It was something of a shock that night when Pedro [Guerrero], naked as always, slathered his member across the banquet of post-game cold-cuts. It must have finally occurred to him that he simply could. I want to say he did it with relish, but that goes without saying. In any case, the clubhouse was seized with a kind of trauma, the players’ eyes wide, their mouths agape at the singular destruction of dinner. We’d all seen Pedro wield his instrument in any variety of ways but never in the vandalism of free food.” Richard Hoffer, quoted in Deadspin

(LAD 1978-1988, STL 1988-1992), .300/.370/.480, 1618 H, 215 HR, 97 SB, 5 All-Star Games

Pedro Guerrero, one of the eight bajillion players to emerge from San Pedro de Macorís1, was for a couple of years every bit as good as Vladimir Guerrero, who was unrelated to him and from a different part of the D.R. Bill James wrote that Pedro was “the best hitter God had made in a long time,” and from 1982 to 1985 he wasn’t wrong.

I don’t remember that Pedro Guerrero, though. I remember the one who appears on this card, a thick-bodied forever-StL Cardinal acquired for the vestiges of John Tudor during LAD’s 1988 pennant push. Guerrero, it seems, had run afoul of Don Frye/Dan Severn-looking ex-football hardman Kirk Gibson, with whose precious eye black “Pete” had tinkered during spring training. Guerrero’s happy-go-lucky demeanor didn’t fit neatly within Gibson’s “If you’re not first, you’re last” weltanschauung, so off he went.

Baseball card companies continued to tout what remained of Guerrero’s once-nonpareil skillz, which wasn’t much given that “Old Pete” didn’t care nearly as much about training as he did about cocaine. He had one last good season in 1989, was featured on more Donruss “MVP” cards than there are grains of sand in the Mojave Desert, and then declined from “Hall of Fame lock” to “Josh Hamilton-style woulda, coulda, shoulda,” except he was superior to Hamilton in every conceivable respect.2

Guerrero would later wind up as the beneficiary of a “low-IQ” defense3 after getting caught in a DEA bust when a $200,000 cocaine deal went south. Guerrero’s lawyer Milton Hirsch argued that he was simply too mentally deficient to understand the consequences of his actions, the jury bought it, and the ex-Dodgers slugger eluded justice in much the same way he used to elude batting practice and calisthenics drills. In 2015, after apparently pulling his life back together the way everybody does once the race has been run, Guerrero began suffering from cranial bleeding and wound up back in the hospital. His condition has been stabilized, leaving him hopeful that he’ll be able to return to his second career as a manager in the low minor leagues.

The conclusion of Pedro Guerrero’s story, like the conclusion of anybody’s story, isn’t sad or tragic or WTF. It just is what it is. For a couple of years, he was the best player of his generation, and then retrospectively we got together and decided he wasn’t. His .300/.370/.480 line is ridiculously good by the standards of 1980s hitters, but it wasn’t backed by enough counting stats (1618 hits, 215 home runs) for the “small hall” Jay Mariottis of the world, who would prefer a blank ballot to anything else4, and so off our hero went into the dustbin of history. Guerrero didn’t care that much about baseball, at least not as much as “gamers” like Gibson and Will “The Thrill” Clark and Pete “Charlie Hustle” Rose, yet he was probably better than all of them for a little while. That won’t put food on your plate the way a $200k cocaine deal might, but it wasn’t nothing. And it’s all I have for big “Pete,” the Cardinals MVP at the end of his rope.

Do yourself a favor and read U-Pitt professor Rob Ruck’s excellent book THE TROPIC OF BASEBALL for a fuller discussion of this topic. You won’t regret it, unless you, like me, are the type who regrets everything from what you had for breakfast this morning to the last words you spoke to your dying father. Then you might regret it.

But not before trading blows with bulldog Cardinals closer Todd Worrell after Guerrero invited fellow Dominican Sammy Sosa, who wasn’t the PED-engorged superman he’d later become, to tour the StL locker room. By all accounts, Worrell, who was well on his way to being washed-up, got the best of the aging, run-down Guerrero.

Such a defense likely wouldn’t have passed muster in the gr8 st8 of Texas, where men like Marvin Wilson (IQ 61, RIP 8/2012) have discovered to their detriment that low mental capacity is no bar to a one-way, all-expenses-paid trip to the Huntsville Unit’s “ol’ sparky” (or, given that ours is a more humane excecuting society, “ol’ lethal inject-y”)

Certainly a man like Pedro Guerrero, who flashed Willie Mays-type skills early in his career, couldn’t hold a candle to the beer-bellied, piano-legged boozers and chain smokers from the 20s and 30s who availed themselves of an uncompetitive, lily-white league to post numbers that were “ridiculous” in every sense of that word.

–Orsolot BeamMeUpScotty

April 20, 2015

Orestes Destrade

(NYY 1987, PIT 1988, SEI/NPB 1989-1992, FLA 1993-1994, SEI/NPB 1995), .241/.319/.383, 184 H, 26 HR

Ah, Orestes. Son of the murdered Agamemnon, whose untimely demise caused a plague of flies to descend upon the city of Argos. The big O avenges daddy’s murder by slaying his treacherous mother Clytemnestra, only to wind up hounded by the Furies and outside the laws of gods and men. Orestes Not Destrade proceeds to lift the plague of flies afflicting the Argives, and then, at least in JP Sartre’s imaginative retelling (The Flies), leaves his former subjects to create their lives in freedom. Existentialism FTW, yo!

Ah, Orestes Destrade. Cuban refugee and prototypical Quad-A hitter who forged a solid career overseas in the NPB. Possessor of a 1989 Topps card despite an unmemorable .149 batting average in 53 unmemorable plate appearances for the almost-there-but-not-quite-yet ‘88 Pirates. And finally, sorta-home run hero of the 1993 Marlins.

It is in this last capacity that I’m most familiar with Destrade’s work, because I know EA’s first Super Nintendo baseball game, MLBPA Baseball, like the back of my hand.1 It was part of a holy trinity of baseball games that included R.B.I. Baseball '94 and Tony La Russa Baseball 3. The latter two kept statistical records–TLRB 3 actually had an astonishingly detailed career mode–but MLBPA Baseball, with its tomahawk chop theme song and nostalgia-inducing '93 rosters, received the bulk of my actual playing time. In part that’s because I liked the SNES controller so much, in part because RBI Baseball played and handled like a bus, and in part because TLRB 3 lagged and crashed on my vintage Compaq computer.

For reasons that are lost to history, the teams I used most were the '93 Tigers (Eric Davis!), '93 Phillies (“Inky” Incaviglia!), '93 Cardinals (former Mets wunderkind Gregg Jefferies putting up prime-period Hal Chase numbers at first!), and the two expansion teams. The Rockies, although saddled with godawful pitchers like Armando Reynoso and David Nied, at least had a bunch of solid hitters at their disposal. The Marlins, on the other hand, had ageless knuckleballer Charlie Hough on the mound, plus Gary Sheffield coming off a lost season, Jeff Conine coming into his own, and perennial Donruss “Rated Rookies” Nigel Wilson and Darrell Whitmore riding the pine.2

But we can’t forget the great Orestes Destrade, who possessed a mere “5” power rating in spite of his 20 round-trippers. Sheffield, who hit 10 home runs in 275 at-bats, warranted a “6,” and Conine, though he’d later become something of a power threat, received a “3” from the game designers.

It’s strange, really: Destrade, who lives on as a Rays broadcaster and possibly still wears those awful metal-rimmed 90s molester glasses, doesn’t deserve a prominent place in my memory, yet here he is anyway. So too are Nigel Wilson and Darrell Whitmore. They aren’t remembered at all for their playing, although they played the game, but rather for being a part of my life. I stared at their likenesses on trading cards and utilized them as players in my video games. None of this means anything except for the simple fact that, as a way of explaining and justifying my life from 1988 to 1998, it means everything.

Make of that what you will; I’m not the one with the dirty mind and the guilty conscience. I’m just a man awake at 3:30 a.m. CT typing the 6th profile in a series that will eventually contain 700-plus.

But where was Carl Everett? He got 20 ABs that season, and that dinosaur-doubting goofball was a “Rated Rookie,” too!

–Orustus Destreudel, with additional research by JA-Mist

April 19, 2015

Lawns

Burt tumbled across the lawn, half-somersaulting and chuckling, in the way that children and fictional meet-cute couples tumble across greenery. His skin itched. The doctor had guessed it would. “You got a grass allergy son. Fresh cut’s the worst. But don’t worry, you can still eat grass sandwiches with the rest of the kids at playtime.” The doctor had winked twice after this joke, once for Burt and once for his smothering parents, already concerned they had fed their child too few — zero — grass sandwiches.

That was ten years ago. Before.

Burt stole a moment to look at the decently cloudy sky, pausing his roll to peer upward between his cocked legs. He missed this, the suburban landscapes opening into mediocre skies and lines of the same oak and maple trees. The scenery perpetually hung in a half-finished copy-paste. Writers would draw inspiration elsewhere, from the yawning lakes of “upstate” or the tight-lipped deserts of canyon country. Burt speculated, ninety degrees from right-side-up, that this commonness is what made these post-war commuter towns brim with this feeling of potential.

Of course, it was frustrated potential. A ball of energy that would spill like a yolk before it drove any great engine of creative or virtuous or important action. It was the kind of possibility that continually stirred and drained in the early-thirties clerical worker ordering new notebooks to start his first novel. These towns were littered with fat concrete lots and drainage ditches and fallow fields opened up and curved back endlessly, the kind of dry-rot infinity you found on treadmills.

Burt’s childhood had obsessed over the potential of suburban vastness, measured out in weed-whacked roadsides and dotted with cul-de-sacs. He’d stage water-gun campaigns across neighboring developments and organize late-night capture-the-flag tournaments. Of course, these plans would work exactly once, when all the parents’ dispositions and the weather and the fickle mood of his half-friends aligned. He’d spend the rest of the summer trying to recreate the riotous fun of that day, sketching out elaborate rulesets and maps for the sequel. Inevitably, he’d fail to resurrect the good time. He remained enchanted by the possibility. If he just had the right plan.

Before now, as an adult fleeing through a ground-water discharge area, he hadn’t considered that his affection and his attention for this area depended on the town always letting him down. He’d assumed — and written essays arguing for the point for low-rent clickbait blogs — that the allure of yards and lots came from their lack of a clear history and obvious intent. In the suburbs or the country, you might see a shoe crunch through a patch of never-enough-rain lawn. You think, “Has anyone even stepped there before? Is there a secret colony of ants or beetles or … whatever else lives in grass?” Hell, there could be some civil war era musket — did they use muskets? — or some coin buried, waiting to be metal-detectored. But in the city, you knew the story of every square-foot of scuffed and cracking concrete. A dog crapped on it. Some lush vomited two weeks of brunch all over it, decades after she should have ended her binging-into-benedict routine. Then, some long-haired kid, fond of affecting a continental accent — a life-long New Jerseyian — squealed his Vespa into a skidmark. It’s all been shit on, spit on and crammed into some wise-cracker’s heroic tableau. There’s no space left for what-ifs.

But that was sentimental. And Burt had no time for affectation. The sirens had multiplied and gotten louder. There was a megaphone?

Burt dug his heel into a patch of tiger-lilies — can you believe it’s a weed! — and sprang over a fence. It wasn’t any superhuman task but it amazed and emboldened him. You can’t jump over fences in cities. They are covered in barbs and razors and lead to junkyard dogs or rundown construction sites, glass and gravel strewn wastelands where gangbangers gangbang and 23-year-old brokers relieve themselves after long nights at Brother Jimmy’s. There’s categorically no jumping allowed in cities. People walk around like their feet are glued to the pavement shuffling and mumbling, checking their phones and their laces to make sure nothing’s come undone.

Naturally, Burt wasn’t allowed to jump when he was younger either, but he admired the slick-haired acrobats who would pack their cigarettes into their sleeves and hop over hoods of their dads’ T-birds. He was fascinated by the tiny boys who scrambled up fences to the little league dugout. His old man caught him trying to climb a tree once. He asked kindly if he was a monkey and if monkies made good lawyers or really had any futures at all. Of course not. Time implies the kind of continuity of thought that only philosophers and inmates really understand.

His professor had told him that right before he shot himself. That’s when all of this started. When the police — who just happened to be on that corner — smashed down the door and found Burt pants-less standing over his dead professor.

“Why is this man here, he clearly doesn’t belong. Look at that blazer! And those patches. He’s got a ten-dollar haircut in a two-bit town. The man looks just like your father. Sure, a younger version of your father. But that aquiline nose and those meaty glutes. He’s a dead wringer.”

“He - he was grading papers. It’s spring break, after all and … it was just a house call!”

Burt didn’t have time to say another word. The deputy pulled his gun, screaming to compose himself, eyes fully lost to their strabismic tendencies.

“He does this all that time,” the sheriff calmly informed Burt, pushing the suspected murderer out of the way, sparing him from the erratic gunfire, saving him for the judge. Above all the bravado and the badges, the sheriff believed in the letter of the law. Burt could tell.

He had used the opportunity to swan dive out of a screen door into the drainage ditch.

Erock Hudson

April 17, 2015

Rock Raines and Dennis Boyd

Raines (MON 1979-1990, CHW 1991-1995, NYY 1996-1998, OAK 1999, MON 2001, BAL 2001, FLO 2002), .294/.385/.425, 2605 H, 170 HR, 808 SB, 7 All-Star Games

Boyd (BOS 1982-1989, MON 1990-1991, TEX 1991), 78 W - 77 L, 4.04 ERA, 799 Ks

A friend asks: Why is Tim Raines, who was almost never referred to as “Rock,” listed as “Rock Raines” on his 1989 Topps card? And why, by extension, is Oil Can1 Boyd identified here as “Dennis Boyd?” Surely neither man was attempting to reinvent his identity the way the artist formerly known as B.J. Upton but now known as Melville Upton Jr.2 appears to be doing. Raines, of course, had once snorted cocaine the way I ate pizza–i.e., we each spent $40,000/year on our vice of choice–but that was many moons before this card dropped. And the great Dennis Boyd, who would sandwich a 2009 comeback between various arrests, admitted in 2012 that two-thirds of the time he took the mound, he was under the influence of cocaine, so it’s unlikely he was trying to separate himself from any past bad choices.3 But like most editorial decisions, including the ones that have reduced my innumerable op-eds to so much pablum, this one was made; and having been made, there it stands, it can do no other.

“Oil can” meaning “beer can,” because that’s the Mississippi slang term for beer, which the substance-abusing Dennis Boyd apparently enjoyed a great deal. This was the sort of detail that should’ve appeared on the back of Boyd’s ‘89 Topps card, but unlike their competitors, the good people at Topps kept it simple: a meaningless statline and maybe, if the economy was particularly good or the editors were in an especially generous mood, a Goofus and Gallant-style cartoon.

Here’s a trend that needs to stop: the superfluous use of a “junior” designation when the “senior” has done nothing to recommend himself (e.g., who the hell was “Roger Mason, Sr.?”). I mean, I’m Oscar Berkman IV, but you don’t hear me going around stumping for the previous three. By way of contrast, lesser versions of golden originals, such as Tony Gwynn, Jr. and Tim “Little Rock” Raines, Jr. definitely warrant such diminutives.

“There wasn’t one ballpark that I probably didn’t stay up all night, until four or five in the morning, and the same thing is still in your system,” Boyd told WBZ NewsRadio 1030’s Jonny Miller in Fort Myers, Fla. “It’s not like you have time to go do it while in the game, which I had done that. Some of the best games I’ve ever, ever pitched in the major leagues I stayed up all night; I’d say two-thirds of them. If I had went to bed, I would have won 150 ballgames in the time span that I played. I feel like my career was cut short for a lot of reasons, but I wasn’t doing anything that hundreds of ball players weren’t doing at the time; because that’s how I learned it.”

–Urville Boatman, with an assist from the Amistad

April 16, 2015

Some Microfictions About the Inner Lives of My Office Supplies

The dysfunctional family that is my hi-liter collection

We all know that Yellow is the favorite. They use her so often they’ve nearly bled her dry. It makes us jealous, and even she would like a break. Can’t they hear her groan each time they scrape her flat felt head against the most important words?

Why not Purple sometimes? Why not Blue, or Green? It’s because we’re too dark, they say. We upstage what truly matters.

Why not Pink? Because pink makes you look like a psycho – if you’re a man, you’ll seem effeminate, and if you’re a woman, you might as well have a Barbie Dream House at your desk, too. And just you try climbing that corporate ladder with a BDH parked in your cube!

Fair enough, but why not Orange? Orange is only one off from Yellow. Not too dark, and not too Barbie.

I’ll tell you why not Orange. Because Yellow is “classic.” Yellow is tradition. People will purchase the variety pack, but they will always only use Yellow. It has always been thus, and thus it will always be. Sic semper, Bic semper.

Unused Scotch tape with lint on it

I was so happy when you arrived.

Finally, I thought, I will fulfill my destiny.

Day after day I waited to find my purpose. And you silently rebuffed me, time and time again.

I understand most of the time. I mean, it’s an online world – who the heck uses paper these days, let alone Scotch tape? (And am I truly Scotch? I don’t feel Scotch. But then, does a person ever feel the blood of their ancestors within them, or is that just part of the package, the persona we conjure for ourselves – “You know me and my fiery Irish temper!” “We’re a boisterous Italian family!” “I love the boomerang so much because I am an Australian!”?)

With time, dust motes settled on my adhesive underside, then a small piece of lint, and I was embarrassed. I didn’t want to appear less than perfect to you. Do you know how much I love you? Who but me gazes at your face – by turns concentrated, weary, low-blood-sugary – for eight hours of the day and never, never tires of it?

No one else.

Associate phone directory

Whaddya want? I got it!

Pick an associate name, any associate name – I got their number!

I can put you in touch – I can help you connect!

Feelin’ lonely? Come to me!

I can even show you where the emergency exits are located. It’s not what you asked for, but I can do it! My back cover’s a beaut!

–CChaps aka “The Shining”

April 15, 2015

Kevin Mitchell

(NYM 1984-1987, SDP 1987, SFG 1987-1991, SEA 1992, CIN 1993-1994 & 1996, FUK/NPB 1995, BOS 1996, CLE 1997, OAK 1998), .284/.360/.520, 1173 H, 234 HR, 1989 Most Valuable Player, 2 All-Star Games

Kevin Mitchell had the potential to hit 45 home runs every single season he played the game, yet only did it once. “World” Mitchell, so called by Gary Carter because he could play any position and anywhere, rarely appeared in more than 130 games a season.

What Mitchell lacked in durability he made up for in hijinks, maladies, and petty criminality. He allegedly ripped the head off his girlfriend’s cat. He had several run-ins with the law. He never wore a cup, ostensibly because none of them were capacious enough to accommodate his prodigious genitalia.1 He made impossible plays in the field look routine and routine plays look painful. He won one World Series with the doomed, damned ‘86 Mets and lost another with the earthquake-wracked Giants. Managers hated him because he always reported for spring training well above his ideal playing weight, which was listed at 185 pounds but never was. He nursed numerous nagging injuries, most of which could have been prevented with even the slightest bit of exercise or physical therapy, and earned a reputation as a malingerer. He still owes millions of dollars in back taxes.

Mitchell mattered as a player from 1989 to 1991, when he and the much more media-friendly Will “Thrill” Clark were the faces of the Giants, and in 1993-4, when he reemerged as the leader of the briefly resurgent Cincinnati Reds. Other than that, he didn’t: the rest of his years were what-ifs and almost-dids and if-onlys. “If only he gets his act together, he’ll help the Red Sox in the playoffs.” “What if he’s the missing piece for the 1997 Indians?”

When he was good, he was phenomenally good. 1989, which saw Mitchell post a .291/.388/.635 slash line across 640 plate appearances, was an absurd display of power from a 5'10", 215-pound former utility infielder. 1994, the most forgettable great season in history, represented his peak and coda as a hitter: averages of .326/.429/.681 while on pace for 45 to 50 home runs.

Set aside these two outlier performances and you’ve got a lesser Milton Bradley. Include them and you’re talking Hack Wilson without the assistance of the 1930s-era juiced ball. Each year, I’d sit back and wait for Mitchell to do something special. He never failed to disappoint, even when he did.

A friend noted that this brief discussion didn’t do justice to Mitchell’s many idiosyncrasies. “World,” for example, ate Vicks Vapo-Rub and washed down amino acid tablets with Hawaiian punch (srsly, no fooling:

http://articles.chicagotribune.com/1989-10-03/sports/8901190070_1_bottle-vicks-vaporub-locker). He also strained a stomach muscle while vomiting and broke a tooth on a frozen donut he’d overcooked in the microwave. But such accomplishments pale in comparison to the prodigious feats associated with 1980 Rookie of the Year “Super” Joe Charboneau. Charboneau, who flamed out long before Topps could include him in its 1989 set, gained a reputation for eating light bulbs and shot glasses, opening beer bottles with his eye socket, and once tried to cut off a tattoo with a razor blade so that his mom wouldn’t find out about it.

–Erem Boomin

April 14, 2015

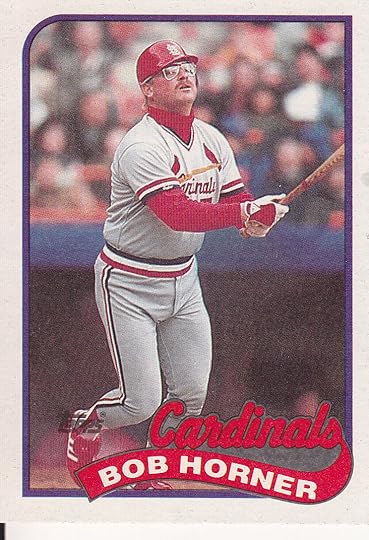

Bob Horner

(ATL 1978-1986, YAKULT/NPB 1987, STL 1988), .277/.340/.499, 1047 H, 218 HR, 1978 Rookie of the Year, 1 All-Star Game

The story of Bob Horner might be a tragic one if more people knew it. He was one of many Arizona State products to strike it rich in the majors, hitting 58 homers during his time at the school and getting drafted by the Braves with the first overall pick in the 1978 draft. He didn’t spend a day in the minor leagues. In just a little over half a season, he hit 23 home runs, slugged .539, and won the Rookie of the Year award over Ozzie Smith, a man who went on to have a far more enduring career.

But just how tragic was Horner’s story? He hit 218 home runs in Major League Baseball and 31 more in Japan. Except for his last season, he was a consistent producer at the plate. Sure, he gained weight, switched positions from third base to first because he was terrible in the field, and suffered a career-ending injury with the Cardinals in 1988. In spite of that, his career spanned a decade, he’s considered one of the greatest college players in the history of the game, and there are literally millions of his 1989 Topps card in circulation. In that photo, where he’s wearing huge 1980s square-rimmed glasses and an ill-fitting Cardinals uniform, resides his such timelessness as he possesses: we remember Horner, and by we I mean I, as this thick-bodied, washed-up athlete hanging on for one last crack at the piñata.

When greatness is measured in 500-homer and 20-season increments, ten years of sustained productivity doesn’t represent failure, only tragedy. How close Horner came to fulfilling his g*d-given talent is unclear. One argument is that he fulfilled all of it, that we can’t do any more than we’ve done, that counter-factual history is a parlor game played by losers. He got fat and hurt his shoulder because genetics dictated that he would, after which his body wouldn’t. The opposite argument is that every moment of life is a freely-elected compromise between competing interests, greatness being one of them. Were five hundred home runs more important than extra time with friends, or extra time spent watching Friends on television? Was the ability to pull a hot grounder out of the dirt at third more important than a dozen extra chili dogs at Atlanta’s The Varsity drive-in? With great talent comes the freedom to squander it, goes this narrative.

Each approach has its merits. The former seems more precise, more “scientific.” So that’s why it happened, eh doctor mister sociobiologist? The latter is more elegant. Among the most beautiful varieties of art is a wasted life. I didn’t pay much attention to Mike Tyson or “J.R.” Rider or “Doc” Gooden on the way up, but I sure as heck noticed them on the way down. Each year, you saw less and less of these guys, until, for one reason or another, there stopped being any there there. Along the way, their flashes of brilliance–a surprising knockout punch, a 360 jam after spending most of the game sucking wind on offense and staying invisible on defense, a no-hitter–reminded you of what once had been and what now was inevitably slipping away. Even as a kid, such thoughts brought a smile to my face. These people, memorialized on card stock like fossils in amber, were living reminders that their glorious 1986s and 87s and 88s would be no more. And neither, of course, would mine.

–Eddie Bookman

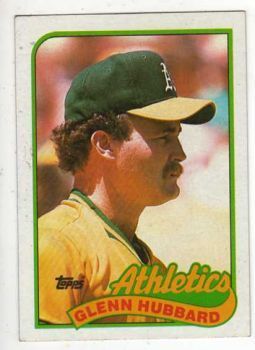

Glenn Hubbard

(ATL 1978-1987, OAK 1988-1989), .244/.328/.349, 1084 H, 70 HR, 1 All-Star Game

Glenn Hubbard is one of those names and faces from the past that, quite frankly, don’t mean much. He just doesn’t. That’s most names and faces, right? But Hubbard, I met him in 1988 at a card-signing event. He was playing for the Athletics then, and they’d just lost the World Series to Kirk Gibson and the Dodgers. He signed a couple of my baseball cards. He wasn’t a very big guy, and by this point he had a little pooch belly.

Advanced metrics now tell us that Hubbard was a great fielder, and also he wasn’t a complete zero with the bat, either. He walked a lot and ran the bases pretty well. I’ll always remember him in his powder-blue Braves uniform, him and overweight Bob Horner and all-American hero Dale Murphy. Hubbard was just an accessory to those two, but he was part of something real and deeply Southern and forgotten. Before 1989, which was this watershed moment in American history that nobody can or will ever write about, something yet remained of the distinctive sporting culture of that region: NASCAR, WCW wrestling (“the superstars on the SuperStation!”), and the Braves as the sole MLB representative of this old, Texas-not-included South.

Dale Murphy and Ric Flair were supermen. They bestrode the spaces below the Mason-Dixon line like colossi. Flair was in his forties by the time 1990 rolled around, and Murphy was all but out of baseball. So was Glenn Hubbard, who retired in 1989 to much less fanfare. But it was an end to something, and that wasn’t nothing. The world I lived in would never be the same.

–Orville Redenbacher

April 13, 2015

The Beginning of the End/The End of the Beginning

Aristophanes’ The Frogs tells of two boys playing near a stream who find a frog and, for fun, kill it. They killed the frog in jest, Aristophanes reports, but the frog died in earnest. People whose lives are diminished, ruined, or taken because of the ethos of the era in which they live are like Aristophanes’ frog. Impersonal forces of history may explain what happened to them, but their suffering and loss are real.

Eddy Jacks Jr., imitation son of the golden original, wrestled his last match when he was 32 years old. Almost since he had finished playing college football and washing out of the CFL, he had been touted as a Next Big Thing. Not the Next Big Thing, because he had a fair number of flaws1, but certainly one of many possible Next Big Things.

It could have happened a bunch of times, such as when he won the IIWF Intercontinental Title at age 24. The Internet smarks, obsessed with four-star matches and the Japanese “strong style” of working, made a big deal out of his victory: here was this kid who could flat-out wrestle, rewarded by a top-heavy, veteran-driven company with a poor reputation for handling young talent. His father, the original Eddy Jacks, was overjoyed. The imitation Eddy Jacks’ friends, most of whom were trying to enter the business themselves, were insanely jealous. He looked to all the world like a future star. What could go wrong?

Everything, of course. Junior’s first couple of title defenses were pretty lifeless, which was tragic given that they served as co-main events for the weekly television show. His big feud with Marty Warnett, a bland English technician who had served as the federation’s default Intercontinental champ for over a decade, generated exactly zero heat. Junior was wrestling then as an All-American blue-chipper, and Warnett was doing a typical European heel gimmick, and those styles didn’t mesh at all. Their work was believable, but their performances weren’t sincere. When it ended at WrestleWar XII, the imitation Eddy Jacks lost cleanly in the center of the ring. He had held the belt for exactly eight weeks, and now he was finished.

The funny thing was, Junior’s promo work actually got better after he left the Intercontinental title picture. The IIWF brought his washed-up father out of retirement and had him serve as his son’s abusive trainer, a role that fit the big man as comfortably as an old shoe. The Jacks Family found itself in a crowded tag team division. The Black Watch, a high-flying tag team from Scotland, was locked in an epic yearlong feud with the Baddest Thangs Running, and because the original Jacks had heat with one of the Thangs, they spent the better part of their run putting them over at house shows.

But people liked the Jacks Family, and their Jacks Family Values vignettes kept them going long after knee and shoulder injuries forced the original Jacks to the sidelines. Junior would go out to the ring, screw everything up, and then the original would hit his son’s opponent with a pair of brass knuckles. There was a Television Title reign mixed in there somewhere, but that strap had been so degraded by innumerable title changes that it was reserved solely for the comic relief guys. Jacks Junior, who hadn’t been booked to look strong in years, excelled at playing a loser–and that’s eventually what everybody came to think he was.

Four years after he entered the Double Eye, Junior’s contract expired. It wasn’t renewed. No reasons were given, and none needed to be: he had once been, in his the words of the original Jacks, “like a hot dog on a bun: on a roll,” but now he was about as valuable as last week’s advertising circular. His old man, whom Junior mostly but not completely detested, was no longer able to perform in any capacity and hung up the boots for good. He would occasionally drag himself out of the house for a one-off show with his kid in some Midwestern palookaville, but his cash value as an attraction had dwindled to nothing, too. The difference between the original Jacks and the imitation was that the original had been the undisputed World’s Champ back when that still meant something, even if he had only held the strap for a week, and the imitation hadn’t been anything at all.

For a while, Junior chased those ever-decreasing bucks. $300 to headline a show in Kalamazoo, Michigan for Great Lakes Championship Wrestling. $1,500 plus travel costs to lose to Tex Violence in a barbed-wire match in Japan that saw Junior’s eye knocked clean out of the socket. 2 Other engagements resulted in worse injuries, ranging from a torn rotator cuff (never surgically repaired) to the amputation of several toes. And so it was at age 32 that the imitation Jacks, already woozy from the semisynthetic opiods that were now his mother’s milk, botched the landing on a clumsy moonsault and wound up with a fractured hip.

Was it in vain? The best years of the imitation Jacks’ life were gone, spent chasing the legacy of an original who hadn’t been all that good in the first place. But the original had been a wrestler, which was the only thing that Junior had ever wanted to be. Junior was a wrestler too, by some accounts an especially gifted one, but now he wasn’t anymore. He had wanted to wrestle since he was five, started at 22, and never participated in another match after turning 32.

“I always kept coming to crossroads,” he told me a couple of weeks ago. “I always found myself on the cusp of something. But by the time I got there, the train had already departed. No matter how early I left, it was gone. I kept missing happiness by a few minutes each time.”

What does it mean, you have to ask yourself, to be so close to something that you can taste it, yet still so far from it that nobody would believe you were ever there? It was similar, Junior felt, to his college football experience: you always believed you were lying to people when you told them you had done it, like you were fudging the record merely by reporting it wie es eigentlich gewesen.

In his wildest dreams, the imitation Jacks would have wrestled a match so pretty that no critic could ever think past it. It would be the match of which no greater could be conceived; and at the precise moment he lost, his shoulders went pinned to the canvas for the “long three,” he would just vanish into thin air. There would be nothing left of him, no trace of his having existed at all. The match would linger in the minds of the fans who witnessed it, but they wouldn’t know what it was that they saw, not really. Their memories would amount to nothing more than a digital picture of a xeroxed copy of a stenciled mimeo of a carbon copy of this golden original, an event that, in the words of another famous wrestler, would be “often imitated but never duplicated.” He would have been his own man at last.

But forget that fantasy: Junior went on living, his dream deferred shriveling up like a raisin in the sun. The steroids he had abused in his twenties and thirties in order to remain viable in a sport dominated by giants had so weakened his heart, though, that he only had to endure two more decades of this. Then he was gone, that best friend of mine, and it was alright.

In no particular order: 1) In a sport dominated by giants, he was 5'10". 2) Although he was great on the mic, his talent never translated into a consistent “gimmick” that got over with the fans. He gained some traction in his twenties working as part of a father-son tag team with his mentally disturbed old man, and after his father’s demise he generated some heat in regional promotions with a “Gorgeous George” persona. 3) He was frequently injured and gained a reputation as something of a malingerer. Most of the injuries were related to his copious intake of oral steroids and other dangerous prescription drugs, which helped him maintain an impressive physique but exacted a high cost in other respects. 4) He refused to submit to the locker room hazing that other rookies experienced. Some promoters, particularly ex-wrestlers like Steve Kowalski, respected Jacks Jr. for this. Most, however, thought he was too big for his britches. 5) Much like his skinflint father, Jacks Jr. was incredibly cheap and argued about every paycheck. 6) Despite not being “one of the boys,” he was all too eager to job if the circumstances demanded it. After a few clean pinfalls, he was basically finished in the estimation of the fans. He really had no idea how to develop his reputation, assuming instead that his abilities would do the talking for him. They didn’t. 7) He was kind of an asshole to the guys he worked with, always forcing them to wrestle his plodding, ground-bound style of match. 8) He managed to blend a sense of entitlement, a sense of false modesty, and a tremendous inferiority complex into a total package of midcard loser-dom. 9) He had been horrifically abused as a kid, though nobody save yours truly knew this, and as a result conducted all his affairs with a sense of fatalism that would impress even a put-upon 19th century Russian serf.

YouTube that, yo. Shit’s nasttteeeee.

–Umma Beachman

April 5, 2015

Historia Calamitatum

Ah, memories. I have some of those: a few good ones, a few medium ones, and a lot of bad ones. The bad ones are what I prefer to dwell on, particularly when I’m around strangers who haven’t yet heard my sob stories.

One thing I’ve learned over the years1 is that it is better to tell fictional sob stories than real ones. What I like to do, given how I’ve inherited the “luck of the Irish” from my deceased and decidedly non-Irish father, is to either exagerrate or to downplay how bad things have been for me, depending on what I believe the expectations of my audience are. So if I’m before a crowd of real fucked-up “Marla from Fight Club” types2, I’ll shoot high: multiple molestations, total impoverishment, suicide attempts stacked one atop the other, years in rehab, and the rest of the Whole Nine Yards starring Matthew Perry and the l8, gr8 Michael Clarke Duncan as the Nine Yards. But if I’m in front of a bunch of good country people of the sort who used to look down on me and my fucking family of fucking idiots, I’ll just mouth some platitudes about how “I’ve struggled to get my act together” and how “my late twenties were rough but I’m in a better place now.”3 I might even append something about centering myself or renewing my faith if that’s what I think people want to hear.

As a historian, or at least as a man who plays a historian at work, I have reached a point of no return: I have lost my faith in the past. Not in the people who lived in the past–they were, much like the people of today, arrant imbeciles and sex-crazed buffoons–but in the fact that there was a past at all. Human memory is more than just faulty, pace Montaigne, it’s nonexistent. How many conversations begin with vague recollections? “Yes, Bill, how’s he doing? Does he still eat shit out of the commode? I distinctly kinda sorta may have heard about him doing that and I’d like to follow up with you regarding this anecdote.” How fleeting and insubstantial is our engagement even with material that has been recorded for posterity? “Oh yeah, that movie I probably saw but that I know exists in the world, it was kinda okay, I guess. Nothing special, but yeah, definitely a movie.”4

At a certain point, you–and you meaning me, while also meaning you–need to recognize that you’re not remembered and that you don’t matter. You need to understand that your job is pointless, and that all of the time you’ve taken to speak to other humans, who are every bit as rotten and ungrateful as you, was actually less productive than pissing in the wind, because at least in that case a “product” of some sort is involved. Other humans can sit across from you and utter words, but their presence, like your own, amounts to little more than a way of killing time while waiting for something better and truer, something more momentous, to occur. You aren’t that thing for them and they aren’t that thing for you.5

“I have now understood that though it seems to men that they live by care for themselves, in truth it is love alone by which they live.”

Leo Tolstoy was a sweetheart and a runny-nosed god of a writer, but he knew more about beard-growing than human nature. Men6 live to eat, first of all, and once they’ve discovered a consistent source of food, they live to pop their cherries, after which they raise or abandon offspring. But once the offspring are raised or fail to materialize due to protection or impotence or “shooting blanks” or what have ye–and here I’m not privileging one outcome over the other–what else is left? Children, insofar as they serve any purpose at all, seem to exist to anchor us to the world until such time as they can be released into the wild, whereupon they’ll relaunch the whole wretched cycle of trying and failing. But I suppose I can understand why they provide “joy” and “hope” for so many. Kids/“kiddos”7, like the prospect that a cherry-popping might be more than just that, represent limitless possibility. Maybe this next run, your child’s doe-eyed look suggests, won’t be so goddamned stupid and pointless &c. Maybe he or she will do the right things for the right reasons, instead of the wrong things for no reasons. Maybe people will listen to him or her, since there’s always a chance. Isn’t there always a chance?8

Screaming! Screaming! I heard screaming!

My own ostensible reason for living was to come back from my hard times, and it’s now clear that I’ve come back and went. Each one of these sweet little stories constitutes a fragment of the last will and testament of Oscar Berkman, a literary character too tough to die and too weak to watch thirty minutes of DailyMotion footage of late-life circumcisions (much less to actually get one in the hopes of scoring a moderately fast-trending and half-viral Slate.com piece out of the ordeal). So I say to you, Oscar Berkman’s Harshest Critics, exactly what I said to my high school classmates when my stellar GPA qualified me to deliver the “baccalaureate oration”: It’s been real, it’s been fun, but it hasn’t been real fun. Catch ya on the flip side, humanoids.

Usually on dates, when I’m trying to “score” or “pop my cherry,” neither of which ever has happened. I really thought that Life™, by which I mean the game of Life™, should revolve around this all-important, all-consuming quest. The game, which is already laid out as a kind of haphazard highway that leads to the enlightenment of the grave, should fix greater attention on the sort of plot device that concerns our finest examples of “teen cinema” and “hot college comedy”; viz., “cherry-popping.” Because, at least as far as I can tell from watching these movies over and over on account of how they stave off the tears, Life™ is all about “popping your cherry” and then just flat-out coming to a bittersweet end. And what I want more than anything else, God how I want it, is an ending. A little closure, is that too much to ask? Because my story, of which you’ll read, skim, or ignore more of in the body of the text, contained plenty of opportunities for a bang finish. But here I am, 30 years old and it’s still just creaking along like an ex-NFL player trying to walk up a flight of stairs. Like srsly wtf omg zomg rofl roflmao

Please don’t take this reference as an endorsement of either the book, which is the most manipulative piece of shit ever committed to paper, or the film, which ought to have come with a barf bag so that I could’ve puked my guts out after becoming overwhelmed by the Fincher-enforced sentimentality.

None of this is true, but what is truth? In my opinion (and that’s all eXiStEnZ is; it’s just, like, your opinion, man), truth is whatever *feels* true to you. Or, as O.W. Holmes Jr. so neatly put it, “truth was the majority vote of that nation that could lick all others.” But isn’t it more than this? Did something real ever happen to me? My lived past, whatever that past might have consisted of, seems about as heavy as a gross of cotton candy skewers.

Said to you after you’ve proceeded to deliver a disquisition on the merits of that film, which undoubtedly had deep meaning for you up until the moment when this brusque and careless dismissal by a third party revealed how barren and infirm your mental landscape was.

Consider, if you will, a date. A meeting with a student or an employer/employee would work equally well here, but I’m going with a date because that’s a universal and universally awful occurrence all of us have had to endure during years on this orb leavened only by the fact that, for reasons entirely out of our control, we weren’t born into one of the hundreds of polities being exploited by the small percentage of elite ones that are currently grinding up the rest of the world to make their bread. To which I say, “tough titty,” as if this were a thing people ever said or still say. Anyway, you’re on this date and saying words and it’s “blah blah blah blah.” “Blah blah blah blah” is exactly how the words are reaching the other person, who within two seconds of meeting you had already decided whether to “pop your cherry” and undoubtedly concluded that safety should be *semper ubique et omnibus* prioritized over feeling sorry. And his or her words are streaming in to you as “blah blah blah blah.” Mixed in there somewhere are a bunch of lies, maybe a generous exagerration of your salary or general lot in life (the two amount to the same thing), and the gradual recognition that Forster’s exhortation to “only connect” is about as bullshit as professional wrestling. Then you go your separate ways, and if you ever see one another again, you pass each other with your heads down and hope that it wasn’t as bad as you thought it was, because damn it seemed bad at the time. But fortunately you and he/she weren’t memorable at all, and are wrong to think that you are (how narcissistic of you both!), so it doesn’t matter.

Here I mean “men and women” but simply don’t want to type that, nor do I want to write “people” because I don’t like how that word sounds. Not that I should give two shits about the literary quality of my work, since a) it’s all dreadful and b) no one reads it, but I have my pride and not much else. You know what really gets my goat, though? Those lazy fucking comedians and social commentators whose entire horseshit careers consist of making observations about how men and women are different, how ethnic groups say and do silly things, and so forth. This is about the lowest form of human creativity, if it can be called such at all, and yet we still continue to embrace it. Think about a comedian like Amy Schumer, whose hackneyed shtick largely consists of insincere jokes about what disappointing assholes 99.9% of men are; what good is this kind of work, aside from shoring up the embodied cultural differences that have made life a vale of tears? We already know that our time on earth is miserable, and that the things that separate us one from the other are what makes it such a ruinous experience. Why not seek in comedy, or in commentary more broadly, for some thread of the universal? Why not aspire to create things that will last beyond your time, if not for all time? You’ll fail at it the way I’ve failed at everything I’ve ever attempted, but at least I’ve failed on my own terms and I’ll go down curled in a fetal ball while other, worse people go down swinging without so much as a clue as to when their fortunes were reversed. They’ll probably still have more money than I do, though, and that’s not nothing.

I know this awful middle-aged sackcloth & ashes of a human being (a “human bean,” as my late father RIP g-d rest his soul etc. used to say) who insists on referring to all people under age 30 as “kiddos,” and it’s a term I hate more than life itself, which is saying something if you’ve read at least a couple sentences of this piece.

I wish I had been by my father’s side when he died. I don’t know what I would’ve said to him, but I would’ve said more to him than I did during our last real conversation, which took place while I was driving up and down the Pacific coast in a gray Toyota van filled to bursting with students. It would’ve been a great scene for the story of my life, you see, and I could’ve jazzed it up with a little James Frey-meets-Mitch Albom hocus-pocus, thereby extracting a threadbare and emotionally bankrupt meaning from a moment that quite honestly would’ve meant jack shit to me, given how broken-down I already was. I’m still not over it, meaning my relationship with him, but neither am I under it. Rather, I’m in exactly the same place with it that I had been for many years, which is to say I’m left with a firm understanding that the point of his life had been to show me that there was no point to mine.

–Ohvuh LeRoi Bimmin

Oliver Lee Bateman's Blog

- Oliver Lee Bateman's profile

- 8 followers