Chris Ferrie's Blog, page 2

August 24, 2019

My Speech to 500 Australian Teenage Schoolboys About Mathematics

I suppose I should start with who I am and what I do and perhaps why I am here in front of you. But I’m not going to do that, at least not yet. I don’t want to stand here and list all my accomplishments so that you may be impressed and that would convince you to listen to me. No. I don’t want to do that because I know it wouldn’t work. I know that because it wouldn’t have worked on me when I was in your place and someone else was up here.

Now, of course you can tell by my accent that I wasn’t literally down there. I was in Canada. And I sure as hell wasn’t wearing a tie. But I imagine our priorities were fairly similar: friends, getting away parents, maybe sports (in my case hockey of course and yours maybe footy), but most importantly… mathematics! No. Video games.

I don’t think there is such a thing as being innately gifted in anything. Though, I am pretty good at video games. People become very good at things they practice. A little practice leads to a small advantage, which leads to opportunities for better practice, and things snowball. The snowball effect. Is that a term you guys use in Australia? I mean, it seems like an obvious analogy for a Canadian. It’s how you make a snowman after all. You start with a small handful of snow and you start to roll it on the ground. The snow on the ground sticks to the ball and it gets bigger and bigger until you have a ball as tall as you!

Practice leads to a snowball effect. After a while, it looks like you are gifted at the thing you practiced, but it was really just the practice. Success then follows from an added sprinkling of luck and determination. That’s what I want to talk to you about today: practice.

I don’t want to use determination in the sense that I was stubbornly defiant in the face of adversity. Though, from the outside it might look that way. You can either be determined to avoid failure or determined to achieve some objective. Being determined to win is different from being determined not to lose.

There is something psychologically different between winning and not losing. You see, losing implies a winner, which is not you. But winning does not require a loser, because you can play against yourself. This was the beauty of disconnected video games of 80’s and 90’s. You played against yourself, or maybe “the computer”. That doesn’t mean it was easy. I’ll given anyone here my Nintendo if they can beat Super Mario Bros. in one go. (I’m not joking. I gave my children the same offer and they barely made it past the first level). It was hard and frustrating, but no one was calling you a loser on the other end. And when you finally beat the game, you could be proud. Proud of yourself and for yourself. Not for the fake internet points you get on social media, but for you.

I actually really did want to talk to you today about mathematics. What I want to tell you is that, when I was your age, I treated mathematics like a video game. I wanted to win. I wanted to prove to myself that I could solve every problem. Some nights I stayed up all night trying to solve a single problem. You know how they say you can’t have success without failure? This is a perfect example. The more you fail at trying to solve a maths problem, the more you understand when you finally do solve it. And what came along with failing and eventually succeeding in all those maths problems? Practice.

Well I don’t know much about the Australian education system and culture. But I’m guessing from Hollywood you know a bit about highschool in North America. I’m sure you know about prom, and of course about Prom King and Prom Queen. What you may not know is that the King and Queen’s court always has a jester. That is, along with King and Queen, each year has a Class Clown — the joker, the funny guy. I wasn’t the prom king, or queen. But I did win the honour of class clown.

When I finished highschool, I was really good at three things: video games, making people laugh, and mathematics. I promise you, there is no better combination. If there was a nutrition guide for the mind, it would contain these three things. Indeed, now more than ever before, you need to be three types of smart. You need to be quick, reactive, and adaptive — the skills needed to beat a hard video game. You need emotional intelligence, you need to know what others are thinking and feeling — how to make them laugh. And finally you need to be able to solve problems, and all real problems require maths to solve them.

There are people in the world, lots of people — billions, perhaps — who look in awe at the ever increasing complexity of systems business, government, schools, and technology, including video games. They look, and they feel lost. Perhaps you know someone that can’t stand new technology, or change in general. Perhaps they don’t even use a piece of technology because they believe they will never understand how to use it.

You all are young. But you know about driving, voting, and paying taxes, for example. Perhaps it looks complicated, but at least you believe that you can and will be able to do it when the time comes. Imagine feeling that such things were just impossible. That would be a weird feeling. You brain can’t handle such dissonance. So you would need to rationalise it in one way or another. You’d say it’s just not necessary, or worse, it’s something some “other” people do. At that point, for your brain to maintain a consistent story, it will start to reject new information and facts that aren’t consistent with your new story.

This is all sounds far fetched, but I guarantee you know many people with such attitudes. To make them sound less harmful, they call them “traditional”. How do otherwise “normal” people come to hold these views? It’s actually quite simple: they fear, not what they don’t understand, but what they have convinced themselves is unnecessarily complicated. I implore you, start today, start right now. Study maths. It is the only way to intellectually survive in a constantly changing world.

Phew that was a bit depressing. Let me give you a more fun and trivial example. Just this weekend I flew from Sydney to Bendigo. The flight was scheduled to be exactly 2 hours. I was listening to an audiobook and I wondered if I would finish it during the flight. Seems obvious right? If there was less than 2 hours left in the audiobook, then I would finish. If not, then I would not finish. But here’s the thing, audiobooks are read soooo slow. So, I listen to them at 1.25x speed. There was 3 hours left. Does anyone know the answer?

Before I tell you, let me remind you, not many people would ask themselves this question. I couldn’t say exactly why, but in some cases it’s because the person has implicitly convinced themselves that such a question is just impossible to answer. It’s too complicated. So their brain shuts that part of inquiry off. Never ask complicated questions it says. Then this happens: an entire world — no most of the entire universe — is closed off. Don’t close yourself off from the universe. Study maths.

By the way, the answer. It’s not the exact answer but here was my quick logic based on the calculation I could do in my head. If I had been listening at 1.5x speed, then every hour of flight time would get through 1.5 hours of audiobook. That’s 1 hour 30 minutes. So two hours of flight time would double that, 3 hours of audiobook. Great. Except I wasn’t listening at 1.5x speed. I was listening at a slower speed and so I would definitely get through less than 3 hours. The answer was no.

In fact, by knowing what to multiple or divide by what, I could know that I would have exactly 36 minutes left of the audiobook. Luckily or unluckily, the flight was delayed and I finished the book anyway. Was thinking about maths pointless all along? Maybe. But since flights are scheduled by mathematical algorithms, maths saved the day in the end. Maths always wins.

How about another. Who has seen a rainbow? I feel like that should be a trick question just to see who is paying attention. Of course, you have all seen a rainbow. As you are trying to think about the last time you saw a rainbow, you might also be thinking that they are rare — maybe even completely random things. But now you probably see the punchline — maths can tell you exactly where to find a rainbow.

Here is how a rainbow is formed. Notice that number there. That angle never changes. So you can use this geometric diagram to always find the rainbow. The most obvious aspect is that the rainbow exits the same general direction that the sunlight entered the raindrop. So to see a rainbow, the sun has to be behind you.

And there’s more. If the sun is low in the sky, the rainbow will be high in the sky. And if the sun is high, you might not be able to see a rainbow at all. But if you take out the garden hose to find it, make sure you are looking down. Let me tell you my favourite rainbow story. I was driving the family to Canberra. We were driving into the sunset at some point when I drove through a brief sun shower. Since the sun was shining and it was raining, one of my children said, “Maybe we’ll see a rainbow!”

Maybe. Ha. A mathematician knows no maybes. As they looked out their windows, I knew — yes — we would see a rainbow. I said, after passing through the shower, “Everyone look out the back window and look up.” Because the sun was so low, it was apparently the most wonderful rainbow ever seen. I say apparently because I couldn’t see it, on account of me driving. But no matter. I was content in knowing I could conjure such beauty with the power of mathematics.

I could have ended there, since I’m sure you are all highly convinced to catch up on all your maths lessons and homework. However, since I have time, I will tell you a little bit about what maths has enabled me to get paid to do. Namely, quantum physics and computation. Maybe you’ve heard about quantum physics? Maybe you’ve heard about uncertainty (the world is chaotic and random), or superposition (things can be in two places at once and cats can be dead and alive at the same time), or entanglement (what Einstein called spooky action at a distance).

But I couldn’t tell you more about quantum physics than that without maths. This is not meant to make it sound difficult. It should make it sound beautiful. This is quantum physics. It’s called the Schrodinger Equation. That’s about all there is to it. All that stuff about uncertainty, superposition, entanglement, multiple universes, and so on—it’s all contained in this equation. Without maths, we would not have quantum physics. And without quantum physics, we would not have GPS, lasers, MRI, or computers — no computers to play video games and no computers to look at Instagram. Thank a quantum physicist for these things.

Quantum physics also helps us understand the entire cosmos. From the very first instant of the Big Bang born out of a quantum fluctuation to the fusing of Hydrogen into Helium inside stars giving us all energy and life on Earth to the most exotic things in our universe: black holes. These all cannot be understood without quantum physics. And that can’t be understood without mathematics.

And now I use the maths of quantum physics to help create new computing devices that may allow us to create new materials and drugs. This quantum computer has nothing mysterious or special about it. It obeys an equation just as the computers you carry around in your pockets do. But the equations are different and different maths leads to different capabilities.

I don’t want to put up those equations, because if I showed them to even my 25 year-old self, I would run away screaming. But then again, I didn’t know then what I know now, and what I’m telling you today. Anyone can do this. It just takes time. Every mathematician has put in the time. There is no secret recipe beyond this. Start now.

August 22, 2019

I gave up social media for a month. This happened next.

Nothing. Nothing, and it was glorious. If you haven’t tried giving up social media, I highly recommend giving it a try. But, now I’m back and — as you can see from the awesome clickbait title — I haven’t lost it. Why am I back and — for that matter — why did I leave? Read on.

First, a little back story for context. I joined social media in earnest about 5 years ago after I published my first book. I thought that I needed to be out there promoting my books. Around the same time, a growing number of academics were also adopting social media. I thought then that I could use social media to promote my academic work as well. Certainly, the number of eyes seeing my work increased with my presence on social media. But the big question was always left unanswered — was it worth the time spent?

This is a very difficult question to answer. I still don’t have the answer and I don’t think I ever will. In part, this is because not all time spent on social media has equal value. As my children get ever-closer to the age when all of their peers have a social media connected phone, I’ve become more and more interested in social media, who uses it, and what they use it for. This has been by no means a controlled — or even exhaustive — study, but I learned enough that I scared myself right off the platforms. I paid close attention as I used (mostly) Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook. I talked to colleagues at the university, other authors and parents, and observed people in public. Here is what I learned.

The uses of social media form a multidimensional spectrum, but there are easy to identify extreme behaviors:

Use it as a megaphone to broadcast your message or brand without any further engagement.

Use it to pass time, starring zombie-like at your phone as you scroll endlessly through your feed, which is curated by an algorithm maximizing the number of advertisements you see.

Use it to troll by intentionally offending people.

Use it to communicate with friends, family, or colleagues.

Use it to engage your audience.

In an ideal social network, there would be mutually beneficial interaction between creators and consumers of media. In reality, though, it’s just a vicious cycle of memes, with the most controversial or sensational going viral. It’s like 24-hour news, but a million times worse. It’s not a nice place to be. So, I left.

But what was the first thought to enter my mind after making this decision? Hey, I should tweet about this. Oops. I became addicted to social media. Luckily, I foresaw this and deleted the apps from my phone and had my browser forget my password. This was enough of a barrier to keep me away, and I stayed away for a month.

It was a great month, too. I was much happier and I got heaps done. It wasn’t just that I got back all the time spent on social media, but that social media was a huge distraction. Every time I had a break in my train of thought, or felt a little bored, or wanted a little dopamine hit from some likes, I’d pick up my phone or open a new tab. Even if I only spent a minute there, it was like hours were lost because that break in my train of thought was now completely lost.

So, given all that, clearly I made the correct decision in leaving social media, right? Well, no. The real lesson I have learned is that I wasn’t using social media optimally. There is value in being on social media, but you must be vigilant. And so, I’m back — ready to make the best of this mess called social media.

June 14, 2019

Your children will kill you, and maybe that’s a good thing

Over a hundred years ago an American medical doctor performed an experiment to weigh the human soul. The number he came up with is the now infamous 21 grams. While this is scientifically uninteresting, it is still fascinating to even the most radical antitheistic rationalist. Try as we might—though I’d argue we shouldn’t—to remove the human element from science, there is one inescapable human inevitability: death.

The 21 gram soul nonsense is often used as proof for life after death, or at least out of body experiences. But it turns out you don’t need any of that pseudoscience to existentially experience your own death. I know this because I died once. And, it was having kids that killed me.

The difficulty of raising children is a constant theme of the blogsphere and Twitterverse. There is no shortage of lamentations. These are often met with both harsh criticism and earnest sympathy. The exhausted parent is shamed on one side and lauded for their honesty on the other.

The great thing about your own death is you hardly remember it. And, maybe I shouldn’t talk about like it was mine, as if I own it. It was his death and I can only pity him because, honestly, I don’t get why it was such a terrible thing anymore. But I’ll continue to talk about it as if it were my own past because in a literal sense it is, and it would just be awkward reading otherwise. Or, poetry.

Before children, I was a work hard, play hard college student. I had infinite freedom and I took advantage of every minute of it. Basically, I was the worst candidate to have real responsibilities, and there is nothing like the responsibility of being handed a helpless baby when you’ve never held a child in your life. Seriously, the nurse hands you the baby, says, “congratulations, dad,” and then everyone leaves the room. What the fuck? What I am supposed to do with this? If you want to see the definition of karma, hand a 27-year-old college student who sleeps 10 hours a night until noon a newborn infant.

But, like I said, I hardly remember it. Today I am woken up at 5:00am to a creepy child silhouette—like, how long have you been standing there?—which whispers as soon as it knows I’m awake, “can I watch a movie?” 7 years and he doesn’t know that he’d get an infinitely more favorable response if he had coffee in his hand. But, the thing is, now I love mornings. There is a calm about sunrise that you don’t experience the rest of the day.

There are so many things about life that being a parent has taught me to enjoy, and many that it has forced me to realize are not important. Sure, you lose a lot of freedom. You can’t play Xbox or binge-watch reality TV every night or have those loud friends over. But, those shows were trash anyway and are people that get grumpy because they can’t drink all your beer until 2am anymore really your friends?

Like a phoenix risen from the ashes, with children I am reborn. Now, where is daddy’s coffee?

March 28, 2019

When will we have a quantum computer? Never, with that attitude

In a recently posted paper, M.I. Dyakonov outlines a simplistic argument for why quantum computing is impossible. It’s so far off the mark that it’s hard to believe that he’s even thought about math and physics before. I’ll explain why.

[image error]

Find a coin. I know. Where, right? I actually had to steal one from my kid’s piggy bank. Flip it. I got heads. Flip it again. Heads. Again. Tails. Again, again, again… HHTHHTTTHHTHHTHHTTHT. Did you get the same thing? No, of course you didn’t. That feels obvious. But why?

Let’s do some math. Wait! Where are you going? Stay. It will be fun. Actually, it probably won’t. I’ll just tell you the answer then. There are about 1 million different combinations of heads and tails in a sequence of 20 coin flips. The chances that we would get the same string of H’s and T’s is 1 in a million. You might as well play the lottery if you feel that lucky. (You’re not that lucky, by the way, don’t waste your money.)

Now imagine 100 coin flips, or maybe a nice round number like 266. With just 266 coin flips, the number of possible sequences of heads and tails is just larger than the number of atoms in the entire universe. Written in plain English the number is 118 quinvigintillion 571 quattuorvigintillion 99 trevigintillion 379 duovigintillion 11 unvigintillion 784 vigintillion 113 novemdecillion 736 octodecillion 688 septendecillion 648 sexdecillion 896 quindecillion 417 quattuordecillion 641 tredecillion 748 duodecillion 464 undecillion 297 decillion 615 nonillion 937 octillion 576 septillion 404 sextillion 566 quintillion 24 quadrillion 103 trillion 44 billion 751 million 294 thousand 464. Holy fuck!

So obviously we can’t write them all down. What about if we just tried to count them one-by-one, one each second? We couldn’t do it alone, but what if all people on Earth helped us? Let’s round up and say there are 10 billion of us. That wouldn’t do it. What if each of those 10 billion people had a computer that could count 10 billion sequences per second instead? Still no. OK, let’s say, for the sake of argument, that there were 10 billion other planets like Earth in the Milky Way and we got all 10 billion people on each of the 10 billion planets to count 10 billion sequences per second. What? Still no? Alright, fine. What if there were 10 billion galaxies each with these 10 billion planets? Not yet? Oh, fuck off.

Even if there were 10 billion universes, each of which had 10 billion galaxies, which in turn had 10 billion habitable planets, which happened to have 10 billion people, all of which had 10 billion computers, which count count 10 billion sequences per second, it would still take 100 times the age of all those universes to count the number of possible sequences in just 266 coin flips. Mind. Fucking. Blown.

Why I am telling you all this? The point I want to get across is that humanity’s knack for pattern finding has given us the false impression that life, nature, the universe, or whatever, is simple. It’s not. It’s really fucking complicated. But like a drunk looking for their keys under the lamp post, we only see the simple things because that’s all we can process. The simple things, however, are the exception, not the rule.

Suppose I give you a problem: simulate the outcome of 266 coin tosses. Do you think you could solve it? Maybe you are thinking, well you just told me that I couldn’t even hope to write down all the possibilities—how the hell could I hope to choose from one of them. Fair. But, then again, you have the coin and 10 minutes to spare. As you solve the problem, you might realize that you are in fact a computer. You took an input, you are performing the steps in an algorithm, and will soon produce an output. You’ve solved the problem.

A problem you definitely could not solve is to simulate 266 coin tosses if the outcome of each toss depended on the outcome of the previous tosses in an arbitrary way, as if the coin had a memory. Now you have to keep track of the possibilities, which we just decided was impossible. Well, not impossible, just really really really time consuming. But all the ways that one toss could depend on previous tosses is yet even more difficult to count—in fact, it’s uncountable. One situation where it is not difficult is the one most familiar to us—when each coin toss is completely independent of all previous and future tosses. This seems like the only obvious situation because it is the only one we are familiar with. But we are only familiar with it because it is one we know how to solve.

Life’s complicated in general, but not so if we stay on the narrow paths of simplicity. Computers, deep down in their guts, are making sequences that look like those of coin-flips. Computers work by flipping transistors on and off. But your computer will never produce every possible sequence of bits. It stays on the simple path, or crashes. There is nothing innately special about your computer which forces it to do this. We never would have built computers that couldn’t solve problems quickly. So computers only work at solving problems that can we found can be solved because we are at the steering wheel forcing them to the problems which appear effortless.

In quantum computing it is no different. It can be in general very complicated. But we look for problems that are solvable, like flipping quantum coins. We are quantum drunks under the lamp post—we are only looking at stuff that we can shine photons on. A quantum computer will not be an all-powerful device that solves all possible problems by controlling more parameters than there are particles in the universe. It will only solve the problems we design it to solve, because those are the problems that can be solved with limited resources.

We don’t have to track (and “keep under control”) all the possibilities, as Dyakonov suggests, just as your digital computer does not need to track all its possible configurations. So next time someone tells you that quantum computing is complicated because there are so many possibilities involved, remind them that all of nature is complicated—the success of science is finding the patches of simplicity. In quantum computing, we know which path to take. It’s still full of debris and we are smelling flowers and picking the strawberries along the way, so it will take some time—but we’ll get there.

March 23, 2019

The point of physics

Something I lost sight of for a long time is the reason I study physics, or the reason I started studying it anyway. I got into it for no reason other than it was an exciting application of mathematics. I was in awe, not of science, but of the power of mathematics.

Now there are competing pressures. Sometimes I find myself “doing physics” for reasons that can only best be seen as practical. Fine—I’m a pragmatic person after all. But practicality here is often relative to a set of arbitrarily imposed constraints, such as requiring a CV full of publications in journals with the highest rank in order to be a good academic boi.

You may say that’s life. We all start with naive enthusiasm and end up doing monotonous things we don’t enjoy. But then we tell ourselves, and each other, lies about it being in service of some higher purpose. Scientists see it stated so often that they start to repeat it, and even start to believe it. I know I’ve written and repeated thoughtless platitudes about science many times. It’s almost necessary to convince yourself of these myths as you struggle through your school or your job. Why am I doing this, you wonder, because it certainly doesn’t feel rewarding in those moments.

On the other hand, many people are comfortable decoupling their passion from their job. Do the job to earn money which funds your true passions. Not all passions provide the immediate monetary returns one needs to live a comfortable life after all. So you can study science to learn the skills that someone will pay you to employ. There are many purely practical reasons to study physics, for example, which have nothing to do with answering to some higher calling. This certainly seems more honest than having to lie to yourself when expectations fail.

(I should point out that if you are one of those people currently struggling through graduate school, academia is not the only way—maybe not even the best way—to sate your hunger for knowledge, or just solve cool maths problems.)

A lot of scientists, teachers, and university recruiters get this wrong. There is a huge difference between being curious about nature and reality and suggesting it is morally good to devote one’s life to playing a small part in answering specific questions about such.

Einstein did not develop general relativity to usher in a new era of gravitational wave astronomy, as cool as that is. He did it because he was obsessed with answering his own questions driven by his insatiable imagination. Even the roots of the now enormous collaboration of scientists which detected gravitational waves started in a water cooler conversation among a few physicists, which is best summarized by this tweet:

Your scientists were so preoccupied with whether or not they could, they didn't stop to think if they should… https://t.co/oBKYZ9Ilsh

— Jeff Goldblum (@jeffreygoldbIum) March 9, 2019

In other words, we don’t actually do things through a consensual agreement about its potential value to a higher power called science. We think about doing certain things because we are curious, because we want to see what will happen, or because we can.

Like all other myths scientists and their adoring followers like to deride, science as a moral imperative is just that—a myth. Might we not get further with honesty, by telling ourselves and others that we are just people—people trying to do cool shit. The great things will come as they always have, emerging from complex interactions—not by everyone collectively following a blinding light at the end of tunnel, but by lighting the tunnel itself with millions of unique candles.

February 7, 2019

The minimal effort explanation of quantum computing

Quantum computing is really complicated, right? Far more complicated than conventional computing, surely. But, wait. Do I even understand how my laptop works? Probably not. I don’t even understand how a doorknob works. I mean, I can use a doorknob. But don’t ask me to design one, or even draw a picture of the inner mechanism.

We have this illusion (it has the technical name in the illusion of explanatory depth) that we understand things we know how to use. We don’t. Think about it. Do you know how a toilet works? A freezer? A goddamn doorknob? If you think you do, try to explain it. Try to explain how you would build it. Use pictures if you like. Change your mind about understanding it yet?

We don’t use quantum computers so we don’t have the illusion we understand how they work. This has two side effects: (1) we think conventional computing is generally well-understood or needs no explanation, and (2) we accept the idea that quantum computing is hard to explain. This, in turn, causes us to try way too hard at explaining it.

Perhaps by now you are thinking maybe I don’t know how my own computer works. Don’t worry, I googled it for you. This was the first hit.

Imagine if a computer were a person. Suppose you have a friend who’s really good at math. She is so good that everyone she knows posts their math problems to her. Each morning, she goes to her letterbox and finds a pile of new math problems waiting for her attention. She piles them up on her desk until she gets around to looking at them. Each afternoon, she takes a letter off the top of the pile, studies the problem, works out the solution, and scribbles the answer on the back. She puts this in an envelope addressed to the person who sent her the original problem and sticks it in her out tray, ready to post. Then she moves to the next letter in the pile. You can see that your friend is working just like a computer. Her letterbox is her input; the pile on her desk is her memory; her brain is the processor that works out the solutions to the problems; and the out tray on her desk is her output.

That’s all. That’s the basic first layer understanding of how this device you use everyday works. Now google “how does a quantum computer work” and you are met right out of the gate with an explanation of theoretical computer science, Moore’s law, the physical limits of simulation, and so on. And we haven’t even gotten to the quantum part yet. There we find qubits and parallel universes, spooky action at a distance, exponential growth, and, wow, holy shit, no wonder people are confused.

What is going on here? Why do we try so hard to explain every detail of quantum physics as if it is the only path to understanding quantum computation? I don’t know the answer to that question. Maybe we should ask a sociologist. But let me try something else. Let’s answer the question how does a quantum computer work at the same level as the answer above to how does a computer work. Here we go.

How does a quantum computer work?

Imagine if a quantum computer were a person. Suppose you have a friend who’s really good at developing film. She is so good that everyone she knows posts their undeveloped photos to her. Each morning, she goes to her letterbox and finds a pile of new film waiting for her attention. She piles them up on her desk until she gets around to looking at them. Each afternoon, she takes a photo off the top of the pile, enters a dark room where she works at her perfected craft of film development. She returns with the developed photo and puts this in an envelope addressed to the person who sent her the original film and sticks it in her out tray, ready to post. Then she moves to the next photo in the pile. You can’t watch your friend developing the photos because the light would spoil the process. Your friend is working just like a quantum computer. Her letterbox is her input; the pile on her desk is her classical memory; while the film is with her in the dark room it is her quantum memory; her brain and hands are the quantum processor that develops the film; and the out tray on her desk is her output.

January 10, 2019

The real magic of quantum computing

There is a magician on stage. It’s tense. Maybe it’s a primetime TV show and the production value is super high. The celebrity judges look nervous. There is epic build up music as the magician calls their assistant on stage. The assistant climbs into a box that is covered with a velvet blanket. Why a blanket? I mean, isn’t the box good enough? What a pretentious as… forget it, I’m ruining this for myself. OK, so the assistant is in the box with their head and legs sticking out. What the fuck? Who made this box, anyway? Damn it, I’m doing it again. Then—oh shit—is that a saw? What’s going to happen with that? Fuck! No! The assistant’s been cut in half! And then the quantum computer outputs the answer. Wait, what? Where did the quantum computer come from? I don’t know—quantum computing is magic like that.

By now you have read many articles on quantum computing. Congratulations. You know nothing about quantum computing. I know what you are thinking: Whoa, Chris, I wasn’t ready for these truth bombs. Take it easy on us. But I see a problem and I just need to fix it. Or, more likely, call the rental agent to fix it.

You probably think that a qubit can represent a 0 and a 1 at the same time. Or, that quantum computing takes advantage of the strange ability of subatomic particles to exist in more than one state at any time. I can hardly fault you for that. After all, we expect Scientific American and WIRED to be fairly reputable sources. And, I’m not cherry picking here—these were the first two hits after the Wikipedia entry on a Google search of “What is quantum computing?” Nearly every popular account of quantum computing has this “0 and 1 at the same time” metaphor.

I say metaphor because it is certainly not literally true that the things involved in quantum computing—those qubits mentioned above—are 0 and 1 at the same time. Why? Well, for starters, 0 and 1 are defined to be mutually exclusive (that means it’s either one OR the other). Logically, 0 is defined as [NOT 1]. Then 0 AND 1 is equal to [NOT 1] AND 1, which is a false statement. “0 and 1 at the same time” just doesn’t make sense, and it’s false anyway. Next.

OK, so what’s the big deal? We all play fast and loose with words. Surely this little… let me stop you right there, because it gets worse. Much worse.

The Scientific American article linked above then deduces that, “This lets qubits conduct vast numbers of calculations at once, massively increasing computing speed and capacity.” That’s a pretty big logical leap, but I’d say it’s a correct one. Let’s break it down. First, if a qubit can be 0 and 1 at the same time then two qubits can be 00 and 01 and 10 and 11 at the same time. And three qubits can be 000 and 001 and 010 and 011 and 100 and 101 and 110 and 111 at the same time. And… well, you get the picture. Like mold on that organic bread you bought, exponential growth!

The number of possible ways to set some number of bits, say n of them, is 2n—a big number. If n = 300, 2300 is more than the number of atoms in the universe! Think about that. Flip a coin just 300 times and the number of possible ways they could land is unfathomable. And 300 qubits could be all of them at the same time. If you believe that, then it is easy to believe that quantum computers will just calculate every possible solution to your problem at once and pick the right answer. That would be magic. Alas, this is not how quantum computers work.

Lesson 1: don’t take a bad metaphor and draw your own simplistic conclusions from it.

Try this one out from Forbes: “A bit can be at either of the two poles of the sphere, but a qubit can exist at any point on the sphere.” Spot on. This is 100% accurate. But, wait! “So, this means that a computer using qubits can store an enormous amount of information and uses less energy doing so than a classical computer.” The fuck? No. In fact, a qubit cannot be used to store and retrieve more than 1 bit of data. Again, magic, but not how quantum computers work.

Lesson 2: don’t reduce an entire field to one idea and draw your own simplistic conclusions from it.

I can just imagine what you are thinking right now. OK hotshot, how would you explain quantum computing? I’m glad you asked. After bashing a bad analogy, I’m going to use another, better analogy. I like analogies—they are my favorite method of learning. Teaching by analogy is kind of like being in two places at the same time.

Alright, I’m going to tell you the correct analogy between quantum physics and magic. Let’s think about what a magic trick looks like abstractly. The magician, who is highly trained, spends a huge amount of time choreographing a mechanism which is then hidden from the audience. The show begins, the “magic” happens, and we are returned to reality with bafflement. If you are under 20, then you also take a selfie for the Insta #fuckyeahmagic.

Now here is what happens in a quantum computation. A quantum engineer, who is highly trained, spends a huge amount of time choreographing a mechanism which is then hidden from the audience. The show begins, quantum computation happens, and we are returned the answer to our problem. Tada! Quantum computation is magic. Selfie, Insta, #fuckyeahquantum.

Let’s dig into this a bit deeper, though. Why not uncover the quantum computer—open the box—to reveal the mechanism? Well, we can’t. If we “watch” the computation happen, we expose the quantum computer to an environment and this will break the computation. The kind of things a quantum computer needs to do requires complete isolation from the environment. Just like a magician’s trick, if we reveal the mechanism, the magic doesn’t happen.

OK, fine. The “magic” will be lost, but at least I could understand the mechanism, right? Sure, that’s right. But here’s the catch: a magician spends countless hours training and preparing for the trick. Knowing the mechanism doesn’t help you understand how to actually perform the trick. Nor does seeing that the mechanism of quantum computing is some complicated math actually help you understand how it works. And don’t over simplify it—we already know that doesn’t work.

Let’s look at the example of a sword swallowing illusionist. If you don’t know what I’m talking about, it’s exactly how it sounds—a person puts a sword the length of their torso in their mouth down to the handle. How one figures out they have a proclivity for this talent, I don’t want to know. But what’s the explanation? Don’t worry, I already googled it for you, and it’s simple: “the illusionist positions their head up so that his throat and stomach make a straight line.” Oh, is that it? I’m suddenly unimpressed. So now that you too know how to swallow a sword are you going to go and do it? I fucking doubt it. That would be stupid—about as stupid as reading a few sentence description of some “explanation” of quantum computing and then declaring you understand it.

Lesson 3: don’t place your analogy at the level of explanation—place it at the level of the phenomenon. Let your analogy do the work of explanation for you.

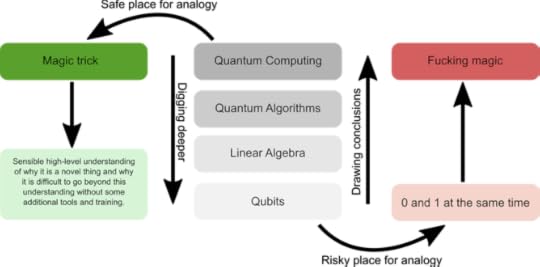

If you like figures, I have prepared a lovely summary for you.

Well there you go. Quantum computing isn’t magic, but it can put on a good show. You can learn about how to do the tricks yourself and even perform a few with a little more effort. I suggest starting with the IBM Quantum Experience. Or, start where the real magicians do with Quantum Computing for Babies

December 31, 2018

Journal | December 2018

Ahhhhh! Summer in Australia. Why did I not know about you sooner?

Eureka!

I’ve been working on a card game on and off for the past few months. Partly as an experiment and partly out of laziness, I decided to “give it away for free”. In practice, this was more work than I expected. For one, I had to learn a little bit about copyright. Long story short, it is released under the license CC-BY4.0, which means—loosely speaking—you can do anything you want with it provided you cite your sources.

I made a game about quantum math. Bring it to your next party and be a hero.https://t.co/wYJ0UGCOa8

— Chris Ferrie (@csferrie) December 12, 2018

One of the big cons of this approach is that you have to find your own way to print their own cards, which is either cheaply done on a desktop printer (lame!) or expensively done on high quality cardstock (ugh!). I’m not sure a way around this.

You can find the instructions for printing and playing the game here.

Reading!

Children’s Literature Recommendations

Pig the Grub by Aaron Blabey

Fun. But would you expect anything less with a Pig book? All the kids love a good Pig story.

Ada Lace Sees Red by Emily Calandrelli and Renaee Kurilla

This is the second book in the Ada Lace series and I think this one is even better than the first! There are lots of relatable elements to this story. But the science—oh, the science—for me made it all the better!

Adult Literature September Reads

Book of Why: The New Science of Cause and Effect by Judea Pearl and Dana Mackenzie

OK, full disclosure. I made a huge mistake in buying the audiobook for this one. There is just too many references to figures to follow along. I made it through alright by slowing it down and already having some experience with causal networks, but I can’t really recommend, or not recommend, this one. Some of the historical anecdotes were interesting, but it was at times hard to read (errr… listen) to the author’s self-pity about not being more recognised.

Through Two Doors at Once: The Elegant Experiment That Captures the Enigma of Our Quantum Reality by Anil Ananthaswamy

Hands down the best popular account of quantum physics. This tells in beautiful detail the key issues surrounding the controversies of quantum physics. The way the author does this all from the lense of a single experiment is inspiring.

Bare Minimum Parenting: The Ultimate Guide to Not Quite Ruining Your Child by James Breakwell

Comedy mixed with unintentional parenting wisdom. The jokes and style get a bit repetitive, but overall I enjoyed the laughs.

Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind by Yuval Noah Harari

Finally got around to reading this highly recommended book. Wish I had read it sooner. Every positive thing written about this book is probably true.

Currently reading: Woo’s Wonderful World of Maths by Eddie Woo

Writing!

Today is the day for ABCs of Engineering with Dr Sarah Kaiser. Check out my #12DaysOfEngineering over on Twitter.

#12DaysOfEngineering

While you are at it, pick up a copy of Blockchain for Babies with Marco Tomamichel.

My first word was #HODL.#blockchain #bitcoin #btc #cryptocurrency #crypto https://t.co/lf5yfwfgmm pic.twitter.com/exq5SCnQcN

— Chris Ferrie (@csferrie) December 24, 2018

The final cover for Cat in the Box (1 June 2019) is here. I’ve seen the internal illustrations and they are great as well! Looking forward to see this one hit the shelves next year! If you can’t quite read the book blurb, it says: Schrodinger’s famous paradox reimagined for the modern world, with more talking animals and fewer dead cats.

Arithmetic! (academic news)

Big news for the Ferrie group! Dr Clara Javaherian and Dr Shibdas Roy have joined as postdoctoral researchers. They will both be working on the AUSMURI project, which is about machine learning and quantum control. Stay tuned to hear about some exciting new science next year!

Events!

I visited Booktopia, Australia largest online bookseller, got a tour and did a podcast: https://twitter.com/booktopia/status/1071275736118558722

Vacation!

Up next!

Both Blockchain for Babies and ABCs of Engineering are released on 1 Jan 2019! But, seeing as it is still peak summer in Australian, we’ll still be at the beach

December 12, 2018

⟨B|raket|S⟩

Created by Me, Chris Ferrie!

2 PLAYERS | AGES 10+ | 15 MINUTES

Welcome to ⟨B|raket|S⟩! The object is to close brakets, the tools of the quantum mechanic! You’ll need to create these quantum brakets to maximize your probability of winning. But, just like quantum physics, there is no complete certainty of the winner until the measurement is made!

No knowledge of quantum mechanics is require to play the game, but you will learn the calculus of the quantum as you play. Later in the rules, you’ll find out how your moves line up with the laws of quantum physics.

What you need

A deck of ⟨B|raket|S⟩ cards, a coin, and a way to keep score.

The instructions are here.

I suggest getting the cards printed professionally. All the cards images are in the cards folder. I printed the cards pictured above in Canada using https://printerstudio.ca. However, they also have a worldwide site (https://printerstudio.com).

You can print your own cards using a desktop printer with this file.

You can laser cut your own pieces using this file.

Open Source

Oh, and this game is free and open source. You can find out more at the GitHub repository: https://github.com/csferrie/Brakets/.

November 30, 2018

Journal | November 2018

Someone told me we need another child so we can cover all 7 colours of the rainbow. As they say in Australia: yeah, nah