Austin Scott Collins's Blog: Upside-down, Inside-out, and Backwards, page 4

April 19, 2015

What Is Art?

Elitism is one of my peeves. I don't just mean callous CEOs, disdainful hipsters and sneering 15-year-old Internet trolls, either. I mean anyone with a superiority complex exhibiting any kind of presumptuous behavior. Such people probably think their scornful scowls are a means of asserting their dominance and advertising their preeminence; in fact it is broadcasting the fact that they are insufferable dicks. There are as many flavors of pretention as there are arenas of human activity, but since this is a blog about writing, I'm going to focus on the bookish variety.

It seems quite fashionable to dismiss mainstream, commercial, mass-market fiction as somehow less valid, less relevant, less important etc. than literary fiction. This bugs me, and I'll tell you why. The fact that something is popular and successful does not necessarily mean it's bad. The fact that something is obscure, opaque and inaccessible does not automatically make it great. Is it possible for an erotic dystopian vampire Western to be good? Of course it is. Is it possible for an 800-page, experimental, cross-cultural, multi-generational, semi-fictional memoir that uses an unreliable narrator and boldly combines a minimalist style with an existential brand of magical realism be awful? Oh, yes.

I have a friend who makes a very good living writing period romance novels. I feel chafed on her behalf whenever I hear someone disparage that genre. Criticize or praise a specific book, if you wish, but don't categorically write off an entire segment of the publishing industry. Remember how you figured out in elementary school that the secret to taking true/false tests was that statements that included absolute words such as "always" and "never" often tended to be false?

Shakespeare's plays were written to sell tickets, not to permeate the English cultural tradition and achieve immortality. All those juvenile puns, crass innuendos and gratuitously bloody fights were blatant theater-bait. But he (or she or they, whatever) did it well, and that's what counts.

Some things are so firmly embedded in the collective consciousness that their status is safe. Michelangelo? Art. Handel? Art. Baryshnikov? Art. Olivier? Art. Kurosawa? Art. Lennon? Art. Where it gets tricky is drawing the line at the bottom. Comparing Finnegan's Wake to 50 Shades of Grey is ludicrous. They're not striving for the same goal. It's like asking, which is better, a loaf of bread or a vacuum cleaner?

On the other end of the spectrum, some might broadly claim that everything is art — every rock, every tree, every sunset, every fire hydrant, every roll of paper towels. Well, that is certainly a poetic point of view, but I feel like it renders the term somewhat meaningless. Is it really a compliment to call something "art" when every scrap of windblown garbage also qualifies?

Art is an intrinsically elusive idea that resists all but the most flexible parameters. Even when you hammer out a relatively agreeable consensus, an exception inevitably comes along, giggling.

Even so, many self-anointed critics are quick to snort that this or that is "not art," a proclamation that is notoriously difficult to dispute. So what is art? Ambitious question. There is an entire field of science and philosophy, aesthetics, devoted to this tangled, squishy subject. And since everyone from Plato to Nietzsche to the clerk at the Circle K has already weighed in, I may as well toss in my own 1.04 cents (adjusted for inflation).

My personal five-part definition of art casts what I consider to be a very wide net:

And this brings me to the fifth and most bitterly controversial element of my test:

That fifth rule doesn't mean that a sculpture made from bits and pieces of trash can't be art. It certainly can. Just recently, Trish and I visited a gallery on Central Avenue in which an artist had created astonishingly beautiful and intricate figures made entirely from discarded household items. But if no one — not even other artists — can tell the difference between the alleged sculpture and an actual pile of ordinary trash, then perhaps that attempt falls below the threshold.

I want to emphasize that these are only general guidelines, and that almost anything can be done with artistic intent. I also want to tack on the caveat that it doesn't matter at all whether I actually happen to like a particular thing. Cubism, for example, doesn't generally speak to me, but that doesn't mean I say cubism isn't art.

The real point is this: by that definition, yes, I do call every novel on the New York Times Bestseller List art, even the ones I don't personally care for. Even the ones that, by most reasonable and objective academic standards of writing, aren't especially good.

Just because an artist has never sold a single piece of her own work in her life does not mean she is any less of an artist than someone who has made millions selling her work. And the opposite is equally true. Financial success is neither directly proportional nor inversely proportional to artistic credentials; it is immaterial.

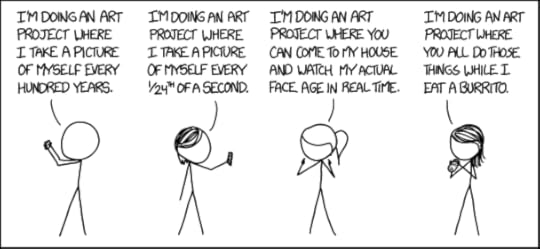

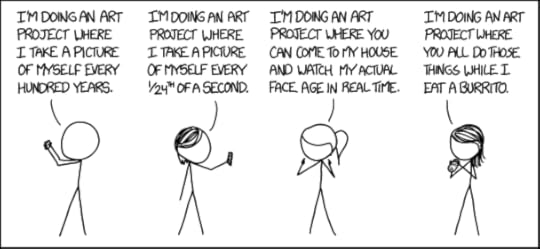

( xkcd )

Recent popular posts:

Jerks: Some Observations

Martinus or Martino?

Answering the Inevitable Questions

Crazy People in History #1

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

My author page:

www.AustinScottCollins.com

It seems quite fashionable to dismiss mainstream, commercial, mass-market fiction as somehow less valid, less relevant, less important etc. than literary fiction. This bugs me, and I'll tell you why. The fact that something is popular and successful does not necessarily mean it's bad. The fact that something is obscure, opaque and inaccessible does not automatically make it great. Is it possible for an erotic dystopian vampire Western to be good? Of course it is. Is it possible for an 800-page, experimental, cross-cultural, multi-generational, semi-fictional memoir that uses an unreliable narrator and boldly combines a minimalist style with an existential brand of magical realism be awful? Oh, yes.

I have a friend who makes a very good living writing period romance novels. I feel chafed on her behalf whenever I hear someone disparage that genre. Criticize or praise a specific book, if you wish, but don't categorically write off an entire segment of the publishing industry. Remember how you figured out in elementary school that the secret to taking true/false tests was that statements that included absolute words such as "always" and "never" often tended to be false?

Shakespeare's plays were written to sell tickets, not to permeate the English cultural tradition and achieve immortality. All those juvenile puns, crass innuendos and gratuitously bloody fights were blatant theater-bait. But he (or she or they, whatever) did it well, and that's what counts.

Some things are so firmly embedded in the collective consciousness that their status is safe. Michelangelo? Art. Handel? Art. Baryshnikov? Art. Olivier? Art. Kurosawa? Art. Lennon? Art. Where it gets tricky is drawing the line at the bottom. Comparing Finnegan's Wake to 50 Shades of Grey is ludicrous. They're not striving for the same goal. It's like asking, which is better, a loaf of bread or a vacuum cleaner?

On the other end of the spectrum, some might broadly claim that everything is art — every rock, every tree, every sunset, every fire hydrant, every roll of paper towels. Well, that is certainly a poetic point of view, but I feel like it renders the term somewhat meaningless. Is it really a compliment to call something "art" when every scrap of windblown garbage also qualifies?

Art is an intrinsically elusive idea that resists all but the most flexible parameters. Even when you hammer out a relatively agreeable consensus, an exception inevitably comes along, giggling.

Even so, many self-anointed critics are quick to snort that this or that is "not art," a proclamation that is notoriously difficult to dispute. So what is art? Ambitious question. There is an entire field of science and philosophy, aesthetics, devoted to this tangled, squishy subject. And since everyone from Plato to Nietzsche to the clerk at the Circle K has already weighed in, I may as well toss in my own 1.04 cents (adjusted for inflation).

My personal five-part definition of art casts what I consider to be a very wide net:

(1) It must be a form of human expression.

(2) It must have been created on purpose.

(3) It must have required some kind of technical skill.

(4) It must provoke an emotional response.

And this brings me to the fifth and most bitterly controversial element of my test:

(5) It must be possible to differentiate it from random objects or normal daily activity. (I know that sometimes people spill a bottle of turpentine on a newspaper in their garage and call it art, but I call shenanigans on that. It's disrespectful to real artists.)

That fifth rule doesn't mean that a sculpture made from bits and pieces of trash can't be art. It certainly can. Just recently, Trish and I visited a gallery on Central Avenue in which an artist had created astonishingly beautiful and intricate figures made entirely from discarded household items. But if no one — not even other artists — can tell the difference between the alleged sculpture and an actual pile of ordinary trash, then perhaps that attempt falls below the threshold.

I want to emphasize that these are only general guidelines, and that almost anything can be done with artistic intent. I also want to tack on the caveat that it doesn't matter at all whether I actually happen to like a particular thing. Cubism, for example, doesn't generally speak to me, but that doesn't mean I say cubism isn't art.

The real point is this: by that definition, yes, I do call every novel on the New York Times Bestseller List art, even the ones I don't personally care for. Even the ones that, by most reasonable and objective academic standards of writing, aren't especially good.

Just because an artist has never sold a single piece of her own work in her life does not mean she is any less of an artist than someone who has made millions selling her work. And the opposite is equally true. Financial success is neither directly proportional nor inversely proportional to artistic credentials; it is immaterial.

( xkcd )

Recent popular posts:

Jerks: Some Observations

Martinus or Martino?

Answering the Inevitable Questions

Crazy People in History #1

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

My author page:

www.AustinScottCollins.com

Published on April 19, 2015 12:09

April 11, 2015

Jerks: Some Observations

No character should ever truly be evil in the pure and unambiguous sense of that word. That's melodrama, and melodrama is lazy storytelling. That doesn't mean characters can't have rotten motivations, but their reason for doing bad things shouldn't simply be, "because they're bad." While it may be tempting to create an individual so vile and despicable that he or she is utterly beyond sympathy, a black hole of a human, that's not likely to be a resonant, enduring villain. The best bad guys are a little bit relatable. We see something in them, a recognizable glimmer, and when it's an uncomfortable echo of ourselves, we find that regardless of arbitrary and subjective labels like "good" and "bad," we care.

In Dicing Time for Gladness (Book I of the Victoria da Vinci series), as well as Crass Casualty (Book II), the primary antagonistic figure is Victoria's personal nemesis, the Baroness von Berge, Greta Greaves of Austria. But Greta doesn't think of herself as bad or even unreasonable. In her vain and paranoid mind, she is a victim of constant persecution, a tragically misunderstood woman slandered by rivals who are jealous of her wealth and power. She rationalizes her actions so thoroughly that she can't understand why anyone would have a problem with anything she was doing.

Another antagonist is Bamwighul Elucidus Fishfire, who makes a brief appearance in Book I and returns as a major character in Book III, Hate's Profiting, which I am currently writing. Bam is a particularly interesting case. He's a murderous psychopath, and feels no empathy for his victims. But he feels no antipathy towards them, either. He isn't motivated by hate or anger. Killing is a game to him, a sport. (And in book III, it has developed into a lucrative, thriving business for him as well.) In one sense at least, Greta is the more sadistic of the two. Bam commits a homicide and them moves on to his next prey with no emotional attachment (and no remorse). Greta wants her enemies to live and suffer. More than that, she wants them to fear, respect and even admire her. She seems to be aware at some level that the things she does are wrong, because she goes to such great lengths to defend and justify herself with bizarre, inconsistent and convoluted logic.

Other characters who come into conflict with Victoria include conservatives such as Josiah Blumfield (Constance's father) and City Councilman Hautious Sugging. But remember, they think of themselves as guardians of civilization and defenders of virtue and morality. In their minds, their impulses are righteous and their actions are noble (even if Sugging is a sanctimonious creep). The point is, they are the heroes of their own private internal narratives, from the standpoint of which Victoria is the bad guy — a purveyor of corrupt values, wickedness and degeneracy.

According to the results of a recent study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (see the abstract here), violent behavior is tied to a sense of over-estimation of self. In other words, people who score highly for narcissism on psychological tests are more likely to be aggressively anti-social and commit various kinds of assault, both physical and emotional. This isn't very surprising.

Low self-esteem: "I'm no good. I'm not worthy of happiness."

Normal, healthy self-esteem: "I am as good as anybody else. It is reasonable for me to expect to be treated with the same courtesy and respect that should be extended to everyone. If I work hard and do good things, I should be acknowledged and fairly compensated for it."

Narcissism: "I am better than other people. I am worthy of special treatment and privileges. Those around me should recognize that they are lesser beings. They should be grateful for my mere presence. I should be generously and immediately rewarded for anything I do."

Of course we all recognize that behavior pattern: people who push in front of other people in line because they're in a hurry. (Like the rest of us aren't in a hurry, too? Asshole.) People who interrupt you to tell you why you're wrong. (Who the hell made you Emperor of Facts?) People who harass and criticize and can't seem to understand why it's not received well. (Oh, you disapprove of me? How galvanizing. I shall change my erroneous ways at once. Thank you for jolting me to action.) People who contribute little, yet make extravagant demands of everyone else with no shame whatsoever. (Do you not see that everyone in the room is staring at you with disgust right now?)

Since these kinds of individuals have so deeply internalized the assumption of superiority and entitlement, of course they become angry when they do not receive the lavish adulation that they believe they ought to be getting just for showing up. So they lash out, with words or punches, in any and all ways they think they can get away with. How dare the world not shower them with a never-ending stream of gifts, VIP treatment and sincere, gushing compliments? They are often obsessed with teaching other, inferior people to know their place. They rarely say anything nice or offer real support, and when they do it's in the form of presumptuous bragging, asserting their inherent right to judge anyone, anywhere, any time, on the basis of anything. (Examples: "Hey, you're not bad for a beginner." "Let me show you how you're supposed to be doing that." "Can I give you a few pointers?")

If you have people like this in your social media feed, you may notice that they never pop up to say things like, "congratulations!" or "I'm so happy for you!" or "you look great!" or "wow, that looks like fun!" or "what a beautiful place!" But they very quickly appear to argue, to challenge, to mock, to condescend, to insult or to contradict. They can't resist the urge. And then what happens when somebody else calls them out on their rude and arrogant behavior? They get all whiny and indignant, hiding behind such defenses as, "I'm just telling the truth!" (The "truth," as they see it, is whatever opinions they hold, and if others disagree it's because they're just too stupid to get it.)

I believe it's helpful, when writing characters who do awful things, to consider why they think they do them. How do they see themselves? How do they see their choices? What made them like this?

It has been observed repeatedly that I like to write flawed, morally ambiguous characters. Even my protagonists tend to be damaged, sometimes irredeemably. I certainly prefer that to one-sided stock characters for whom you are supposed to root wholeheartedly, or else despise. We might feel unalloyed love or searing loathing towards actual human beings out here in real life, but if we try to force that feeling on our readers in our fiction, that's a sloppy shortcut. We must always leave enough ambivalence to make our characters feel like real people and not single-purpose literary devices.

Recent popular posts:

The Intersection of Grammar and Philosophy

Sleeping With My Editor

Martinus or Martino?

Answering the Inevitable Questions

Crazy People in History #1

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

My author page:

www.AustinScottCollins.com

In Dicing Time for Gladness (Book I of the Victoria da Vinci series), as well as Crass Casualty (Book II), the primary antagonistic figure is Victoria's personal nemesis, the Baroness von Berge, Greta Greaves of Austria. But Greta doesn't think of herself as bad or even unreasonable. In her vain and paranoid mind, she is a victim of constant persecution, a tragically misunderstood woman slandered by rivals who are jealous of her wealth and power. She rationalizes her actions so thoroughly that she can't understand why anyone would have a problem with anything she was doing.

Another antagonist is Bamwighul Elucidus Fishfire, who makes a brief appearance in Book I and returns as a major character in Book III, Hate's Profiting, which I am currently writing. Bam is a particularly interesting case. He's a murderous psychopath, and feels no empathy for his victims. But he feels no antipathy towards them, either. He isn't motivated by hate or anger. Killing is a game to him, a sport. (And in book III, it has developed into a lucrative, thriving business for him as well.) In one sense at least, Greta is the more sadistic of the two. Bam commits a homicide and them moves on to his next prey with no emotional attachment (and no remorse). Greta wants her enemies to live and suffer. More than that, she wants them to fear, respect and even admire her. She seems to be aware at some level that the things she does are wrong, because she goes to such great lengths to defend and justify herself with bizarre, inconsistent and convoluted logic.

Other characters who come into conflict with Victoria include conservatives such as Josiah Blumfield (Constance's father) and City Councilman Hautious Sugging. But remember, they think of themselves as guardians of civilization and defenders of virtue and morality. In their minds, their impulses are righteous and their actions are noble (even if Sugging is a sanctimonious creep). The point is, they are the heroes of their own private internal narratives, from the standpoint of which Victoria is the bad guy — a purveyor of corrupt values, wickedness and degeneracy.

According to the results of a recent study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (see the abstract here), violent behavior is tied to a sense of over-estimation of self. In other words, people who score highly for narcissism on psychological tests are more likely to be aggressively anti-social and commit various kinds of assault, both physical and emotional. This isn't very surprising.

Low self-esteem: "I'm no good. I'm not worthy of happiness."

Normal, healthy self-esteem: "I am as good as anybody else. It is reasonable for me to expect to be treated with the same courtesy and respect that should be extended to everyone. If I work hard and do good things, I should be acknowledged and fairly compensated for it."

Narcissism: "I am better than other people. I am worthy of special treatment and privileges. Those around me should recognize that they are lesser beings. They should be grateful for my mere presence. I should be generously and immediately rewarded for anything I do."

Of course we all recognize that behavior pattern: people who push in front of other people in line because they're in a hurry. (Like the rest of us aren't in a hurry, too? Asshole.) People who interrupt you to tell you why you're wrong. (Who the hell made you Emperor of Facts?) People who harass and criticize and can't seem to understand why it's not received well. (Oh, you disapprove of me? How galvanizing. I shall change my erroneous ways at once. Thank you for jolting me to action.) People who contribute little, yet make extravagant demands of everyone else with no shame whatsoever. (Do you not see that everyone in the room is staring at you with disgust right now?)

Since these kinds of individuals have so deeply internalized the assumption of superiority and entitlement, of course they become angry when they do not receive the lavish adulation that they believe they ought to be getting just for showing up. So they lash out, with words or punches, in any and all ways they think they can get away with. How dare the world not shower them with a never-ending stream of gifts, VIP treatment and sincere, gushing compliments? They are often obsessed with teaching other, inferior people to know their place. They rarely say anything nice or offer real support, and when they do it's in the form of presumptuous bragging, asserting their inherent right to judge anyone, anywhere, any time, on the basis of anything. (Examples: "Hey, you're not bad for a beginner." "Let me show you how you're supposed to be doing that." "Can I give you a few pointers?")

If you have people like this in your social media feed, you may notice that they never pop up to say things like, "congratulations!" or "I'm so happy for you!" or "you look great!" or "wow, that looks like fun!" or "what a beautiful place!" But they very quickly appear to argue, to challenge, to mock, to condescend, to insult or to contradict. They can't resist the urge. And then what happens when somebody else calls them out on their rude and arrogant behavior? They get all whiny and indignant, hiding behind such defenses as, "I'm just telling the truth!" (The "truth," as they see it, is whatever opinions they hold, and if others disagree it's because they're just too stupid to get it.)

I believe it's helpful, when writing characters who do awful things, to consider why they think they do them. How do they see themselves? How do they see their choices? What made them like this?

It has been observed repeatedly that I like to write flawed, morally ambiguous characters. Even my protagonists tend to be damaged, sometimes irredeemably. I certainly prefer that to one-sided stock characters for whom you are supposed to root wholeheartedly, or else despise. We might feel unalloyed love or searing loathing towards actual human beings out here in real life, but if we try to force that feeling on our readers in our fiction, that's a sloppy shortcut. We must always leave enough ambivalence to make our characters feel like real people and not single-purpose literary devices.

Recent popular posts:

The Intersection of Grammar and Philosophy

Sleeping With My Editor

Martinus or Martino?

Answering the Inevitable Questions

Crazy People in History #1

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

My author page:

www.AustinScottCollins.com

Published on April 11, 2015 16:24

April 4, 2015

The Intersection of Grammar and Philosophy

Words have the power to mold thought. Complex thinking, conversely, demands an adequate vocabulary in much the same way you can't work on an engine without a large box of specialized tools. When we don't have a suitable word, we are likely to concoct neologisms as needed and/or borrow liberally from other languages that do a better job of expressing that particular idea. But does the lack of a proper grammatical framework actually make certain types of thinking difficult or impossible? Does the structure of the communication systems we have created reciprocally alter the structure of our cognitive patterns?

Imagine a person who speaks a language that lacks a true future tense. This can lead to awkward sentence constructions (and misunderstandings) when trying to convey something that hasn't happened yet. (E.g., "I am being there for the editorial conference tomorrow.") This raises the inevitable question: do people whose native language lacks a future tense actually perceive the world differently? Do they somehow exist in a perpetual capital-N Now? And what about languages with no past tense? When a man speaks of his friend who has been dead for five years and mentions, "Elathóu likes to play music," does that indicate that he somehow actually feels, at least on an intuitive level, that Elathóu never died? And if so, is that a literal or figurative belief? How does it alter his sense of the universe he inhabits?

These are qualia, obviously, and we can never hope to fully understand another human being's subjective personal experience, any more than you can know how I perceive the color red.

That impossibility only makes the issue more interesting, however, and I would love to see some ingeniously designed behavioral and attitudinal experiments in which linguists, neurologists, evolutionary biologists, ethnologists, sociologists and maybe a caterer all get together and do everything from careful interviews and testing to functional MRI scanning and see if they can tease out some fundamental, underlying contrasts in modes of thought (and even the nature of conscious awareness itself) directly related to language differences.

Scientists such as Steven Pinker (author of The Language Instinct) believe that humans are born with an innate capacity for language. It's just something we're wired for. In his book Zero: The Biography of a Dangerous Idea, Journalist Charles Seife argues that the ability to symbolically represent abstract concepts (such as the titular number zero) is what enables a civilization to become great. Zero might not seem like an integral principle of normal primate life, and I suppose it probably isn't, but until some proto-hominid is smart enough to draw a circle in the dirt and tell everyone it means "no bananas," advanced math (and everything that math makes possible, from astronomy to engineering) is impossible. Until then, history never moves beyond picking fleas off each other.

For me, I think the grammatical key to my personal doctrine lies in the gerund. A gerund is a verb used as a noun. The verb “skydive,” for example, can be turned into a participle by adding -ing, and then it can be used as an adjective. (I.e., “She won the skydiving championship.” What kind of trophy? A gold trophy. What kind of championship? A skydiving championship.) That same word can also be used as a noun, in which case it becomes a gerund. “She enjoys skydiving.” (What does she enjoy? Skydiving.) The word now indicates not a description of an event or occurrence, but the activity itself — or even the idea of the activity.

I tend to strongly prioritize experiences over material possessions. And yes, I am well aware that the American economy would collapse if everyone did this. I would much rather live in a very small, simple, modestly furnished house (if I lived in a house at all) and travel extensively than live in a comfortable sprawling mansion and never leave.

Things are appealing to me only when they facilitate adventures. A sailboat, for example, appeals to me because I can use it to go on ocean voyages. The idea of owning a big shiny sailboat that never leaves the dock just to impress my rivals at the yacht club does not appeal to me. It's not that I like airplanes, it's that I like flying. It's not that I like motorcycles, it's that I like riding.

An excellent example of the extreme opposite of this line of thinking is a story I was told about a woman whose wealthy fiancé gave her $20,000 and told her to go buy herself a wedding ring, and that they would use whatever was left over to go on the honeymoon of her dreams. She spent the entire sum on the ring. “Who cares about a honeymoon,” she laughed later, waving the sparkly rock in her friends’ faces over lunch.

If there is one area where I feel English is a bit deficient, it's in the area of describing very specific feelings, social roles, situations and sensations related to universal human experiences. This is where we have to steal from other languages. Déjà vu. Schadenfreude. Quid pro quo. Prima donna.

We can never escape from within our own skulls. Language is a squishy mechanism that imperfectly and inconsistently shares elusive, ambiguous truths. Perhaps this is not always a bad thing.

Popular recent posts:

Sleeping With My Editor

Martinus or Martino?

The Joy of Being Finished

Answering the Inevitable Questions

Crazy People in History #1

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

My author page:

www.AustinScottCollins.com

“But if thought corrupts language, language can also corrupt thought.”

― George Orwell, 1984

Imagine a person who speaks a language that lacks a true future tense. This can lead to awkward sentence constructions (and misunderstandings) when trying to convey something that hasn't happened yet. (E.g., "I am being there for the editorial conference tomorrow.") This raises the inevitable question: do people whose native language lacks a future tense actually perceive the world differently? Do they somehow exist in a perpetual capital-N Now? And what about languages with no past tense? When a man speaks of his friend who has been dead for five years and mentions, "Elathóu likes to play music," does that indicate that he somehow actually feels, at least on an intuitive level, that Elathóu never died? And if so, is that a literal or figurative belief? How does it alter his sense of the universe he inhabits?

These are qualia, obviously, and we can never hope to fully understand another human being's subjective personal experience, any more than you can know how I perceive the color red.

That impossibility only makes the issue more interesting, however, and I would love to see some ingeniously designed behavioral and attitudinal experiments in which linguists, neurologists, evolutionary biologists, ethnologists, sociologists and maybe a caterer all get together and do everything from careful interviews and testing to functional MRI scanning and see if they can tease out some fundamental, underlying contrasts in modes of thought (and even the nature of conscious awareness itself) directly related to language differences.

Scientists such as Steven Pinker (author of The Language Instinct) believe that humans are born with an innate capacity for language. It's just something we're wired for. In his book Zero: The Biography of a Dangerous Idea, Journalist Charles Seife argues that the ability to symbolically represent abstract concepts (such as the titular number zero) is what enables a civilization to become great. Zero might not seem like an integral principle of normal primate life, and I suppose it probably isn't, but until some proto-hominid is smart enough to draw a circle in the dirt and tell everyone it means "no bananas," advanced math (and everything that math makes possible, from astronomy to engineering) is impossible. Until then, history never moves beyond picking fleas off each other.

“Language comes first. It's not that language grows out of consciousness; if you haven't got language, you can't be conscious.”

― Alan Moore

For me, I think the grammatical key to my personal doctrine lies in the gerund. A gerund is a verb used as a noun. The verb “skydive,” for example, can be turned into a participle by adding -ing, and then it can be used as an adjective. (I.e., “She won the skydiving championship.” What kind of trophy? A gold trophy. What kind of championship? A skydiving championship.) That same word can also be used as a noun, in which case it becomes a gerund. “She enjoys skydiving.” (What does she enjoy? Skydiving.) The word now indicates not a description of an event or occurrence, but the activity itself — or even the idea of the activity.

I tend to strongly prioritize experiences over material possessions. And yes, I am well aware that the American economy would collapse if everyone did this. I would much rather live in a very small, simple, modestly furnished house (if I lived in a house at all) and travel extensively than live in a comfortable sprawling mansion and never leave.

Things are appealing to me only when they facilitate adventures. A sailboat, for example, appeals to me because I can use it to go on ocean voyages. The idea of owning a big shiny sailboat that never leaves the dock just to impress my rivals at the yacht club does not appeal to me. It's not that I like airplanes, it's that I like flying. It's not that I like motorcycles, it's that I like riding.

An excellent example of the extreme opposite of this line of thinking is a story I was told about a woman whose wealthy fiancé gave her $20,000 and told her to go buy herself a wedding ring, and that they would use whatever was left over to go on the honeymoon of her dreams. She spent the entire sum on the ring. “Who cares about a honeymoon,” she laughed later, waving the sparkly rock in her friends’ faces over lunch.

If there is one area where I feel English is a bit deficient, it's in the area of describing very specific feelings, social roles, situations and sensations related to universal human experiences. This is where we have to steal from other languages. Déjà vu. Schadenfreude. Quid pro quo. Prima donna.

We can never escape from within our own skulls. Language is a squishy mechanism that imperfectly and inconsistently shares elusive, ambiguous truths. Perhaps this is not always a bad thing.

“Meanwhile, the poor Babel fish, by effectively removing all barriers to communication between different races and cultures, has caused more and bloodier wars than anything else in the history of creation.”

― Douglas Adams, The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy

Popular recent posts:

Sleeping With My Editor

Martinus or Martino?

The Joy of Being Finished

Answering the Inevitable Questions

Crazy People in History #1

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

My author page:

www.AustinScottCollins.com

Published on April 04, 2015 12:22

February 24, 2015

Sleeping With My Editor

Aside from being the one who made the offhand suggestion that I "should write some sort of burlesque-steampunk story," my wife has been a priceless asset during this entire wonderful, painful process.

This trilogy literally never would have existed had it not been for that casual remark — see this post for the full account of how the Victoria da Vinci series was born at that moment and evolved from there — but beyond that, I never would have finished and published the first book without her constant support, encouragement, assistance, validation, occasional prodding and abundance of helpful input. She has a strong grasp of promotion, branding and marketing, whereas I do not. She has a willingness to explore fruitful new avenues of exposure and outreach, whereas I am more likely to get lost in a volume about political upheavals in the Balkans between 1821 and 1912. I can be introspective to the point of absolute uselessness, but my wife can be eminently practical.

Aside from being my most zealous advocate, my biggest fan, my most honest critic and my tireless publicist, however, she is also my primary front-line editor. She has suffered bravely and uncomplainingly through multiple drafts of each manuscript and always gives me excellent notes. She notices things that I miss because she's reading without assumptions. She scribbles comments in the margins such as, "when did she get there?" (I knew she was there, but I forgot to say so.) or "would she really say something like that?" (of course not; what was I thinking?).

Trish is an excellent proofreader, but she has an undefeatable opponent: me. I never cease to massively re-write entire passages, so I generate new errors faster than she can catch and correct them. Where you see a goof, it's mine, not hers. Unlike me, she has a real job, and cannot be expected to proofread the entirety of draft 8.24 as well as drafts 8.25, 8.26 and 8.27.

Since I write my stories out of chronological order (as I explained in this post ), there are often amusing little continuity errors that I fail to catch, such as a character drinking Chardonnay in one paragraph but Pinot Noir in the next. Trish does an excellent job of catching these embarrassing incongruities before they get into print.

Ever since I was in sixth grade, I have often joked that for me, writing was a spectator sport. I just sort of sit there and watch as it happens. Don't you hate it when writers get all pretentious and start to pontificate about life, as if they are qualified to talk about anything other than writing? Because I'm about to do that. Not to get overly philosophical, except that I totally am overly philosophical so never mind what I just said, but the individual human experience is kind of a spectator sport, isn't it? We don't know what we're going to do. We believe we do, sure, but how often do we really make the decisions we expected or hoped to make when confronted with the actual situations about which we had speculated?

Daniel Wegner wrote a book called The Illusion of Conscious Will, which (aside from winning the Austin Scott Collins award for the most perfectly descriptive title ever) poses the dangerously destabilizing question, "do we really decide what to do, or do things just happen to us?" A mounting body of evidence strongly suggests that we convince ourselves later that we had carefully evaluated all options and then deliberately chose a course of action, but in reality we do what we do because of our culture, our upbringing, our genetic predisposition, the chemicals in our bloodstream at the time etc.

When I sit down at my desk to write, I have a fairly solid story outline already built and a relatively firm grasp of who these characters are. But I never know exactly what I'm going to say until I start typing. Although the big elements are scripted out in advance, the details are more improvisational. Thus, when I write the second half of a particular scene in February and then go back and write the first half of the same scene in August (and then go back and add something important to the middle in October), there are inevitable bumpy tonal shifts that must be polished out. This is where Trish's assistance is most valuable.

The single most difficult and important thing than a writer must do as part of the revision process is cutting out material that has to go. (I blogged about that here .) Coming in at a very close second, however, is getting solid and meaningful feedback about the story from smart people who read a lot. The opinions of random strangers are frequently unhelpful, but it is highly advisable to solicit the insights and impressions of those who have strong literary backgrounds. Chances are, someone who reads a lot of books will have at least a few constructive observations. It isn't easy, but it's essential. All it takes is one foul grain within the text, one mildly askew item, to break the spell and send the story off the rails.

In this blog I gave some advice to people who want to become writers. I would add one more bullet point: find a great publicist/editor/business manager and marry that person. (Move fast, because you don't want him or her to find out what it's like to be married to a writer until it's too late.)

Popular recent posts:

Martinus or Martino?

The Joy of Being Finished

Answering the Inevitable Questions

Crazy People in History #1

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

My author page:

www.AustinScottCollins.com

This trilogy literally never would have existed had it not been for that casual remark — see this post for the full account of how the Victoria da Vinci series was born at that moment and evolved from there — but beyond that, I never would have finished and published the first book without her constant support, encouragement, assistance, validation, occasional prodding and abundance of helpful input. She has a strong grasp of promotion, branding and marketing, whereas I do not. She has a willingness to explore fruitful new avenues of exposure and outreach, whereas I am more likely to get lost in a volume about political upheavals in the Balkans between 1821 and 1912. I can be introspective to the point of absolute uselessness, but my wife can be eminently practical.

Aside from being my most zealous advocate, my biggest fan, my most honest critic and my tireless publicist, however, she is also my primary front-line editor. She has suffered bravely and uncomplainingly through multiple drafts of each manuscript and always gives me excellent notes. She notices things that I miss because she's reading without assumptions. She scribbles comments in the margins such as, "when did she get there?" (I knew she was there, but I forgot to say so.) or "would she really say something like that?" (of course not; what was I thinking?).

Trish is an excellent proofreader, but she has an undefeatable opponent: me. I never cease to massively re-write entire passages, so I generate new errors faster than she can catch and correct them. Where you see a goof, it's mine, not hers. Unlike me, she has a real job, and cannot be expected to proofread the entirety of draft 8.24 as well as drafts 8.25, 8.26 and 8.27.

Since I write my stories out of chronological order (as I explained in this post ), there are often amusing little continuity errors that I fail to catch, such as a character drinking Chardonnay in one paragraph but Pinot Noir in the next. Trish does an excellent job of catching these embarrassing incongruities before they get into print.

Ever since I was in sixth grade, I have often joked that for me, writing was a spectator sport. I just sort of sit there and watch as it happens. Don't you hate it when writers get all pretentious and start to pontificate about life, as if they are qualified to talk about anything other than writing? Because I'm about to do that. Not to get overly philosophical, except that I totally am overly philosophical so never mind what I just said, but the individual human experience is kind of a spectator sport, isn't it? We don't know what we're going to do. We believe we do, sure, but how often do we really make the decisions we expected or hoped to make when confronted with the actual situations about which we had speculated?

Daniel Wegner wrote a book called The Illusion of Conscious Will, which (aside from winning the Austin Scott Collins award for the most perfectly descriptive title ever) poses the dangerously destabilizing question, "do we really decide what to do, or do things just happen to us?" A mounting body of evidence strongly suggests that we convince ourselves later that we had carefully evaluated all options and then deliberately chose a course of action, but in reality we do what we do because of our culture, our upbringing, our genetic predisposition, the chemicals in our bloodstream at the time etc.

When I sit down at my desk to write, I have a fairly solid story outline already built and a relatively firm grasp of who these characters are. But I never know exactly what I'm going to say until I start typing. Although the big elements are scripted out in advance, the details are more improvisational. Thus, when I write the second half of a particular scene in February and then go back and write the first half of the same scene in August (and then go back and add something important to the middle in October), there are inevitable bumpy tonal shifts that must be polished out. This is where Trish's assistance is most valuable.

The single most difficult and important thing than a writer must do as part of the revision process is cutting out material that has to go. (I blogged about that here .) Coming in at a very close second, however, is getting solid and meaningful feedback about the story from smart people who read a lot. The opinions of random strangers are frequently unhelpful, but it is highly advisable to solicit the insights and impressions of those who have strong literary backgrounds. Chances are, someone who reads a lot of books will have at least a few constructive observations. It isn't easy, but it's essential. All it takes is one foul grain within the text, one mildly askew item, to break the spell and send the story off the rails.

In this blog I gave some advice to people who want to become writers. I would add one more bullet point: find a great publicist/editor/business manager and marry that person. (Move fast, because you don't want him or her to find out what it's like to be married to a writer until it's too late.)

Popular recent posts:

Martinus or Martino?

The Joy of Being Finished

Answering the Inevitable Questions

Crazy People in History #1

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

My author page:

www.AustinScottCollins.com

Published on February 24, 2015 07:29

February 23, 2015

Martinus or Martino?

“The only American invention as perfect as the sonnet.”

— H. L. Mencken

“A man must defend his home, his wife, his children, and his martini.”

— Jackie Gleason

“The elixir of quietude.”

— E.B. White

“I like to have a martini. Two at the very most. After three I’m under the table. After four, I’m under my host.”

— Widely misattributed to Dorothy Parker, but what the hell, let her have it

What author doesn’t enjoy a celebratory martini after a long day of flagellating a manuscript until it pops and sings? There is only one problem. As the poet Mr. Bellamy pointed out to a group of us on Saturday, “martini" is plural. As in, “Jesus Christ, dude, how many martini have you had tonight? And how did you get up on the roof?”

Mr. Bellamy worships language as much as he worships a fine cocktail, so this is a subject worthy of further consideration. What is the proper singular form?

In Latin, -i replaces -us when changing from singular to plural (e.g., radius/radii and stimulus/stimuli). We would therefore be inclined to use “martinus” as the singular form.

In Italian, however, for regular masculine nouns that end in -o, the ending changes to -i in the plural (e.g., graffito/graffiti and vino/vini). This would give us a singular form of “martino.”

So is it a martino or a martinus? To answer that question, we must first determine whether the word “martini” is Latin or Italian.

Tricky. The invention of the drink itself is of no use; it’s a quintessentially American recipe — despite the many contradictory stories floating around regarding exactly who actually came up with it.

We could resort to the history of the principal ingredients, but gin is primarily British — with ancient Dutch influences — and vodka (although some would say its use in a martini amounts to apostasy) is inescapably Baltic, so we get no help there. Vermouth, on the other hand, is definitely a product of the Apennine Peninsula, so that’s our best lead.*

*Side note: Noël Coward once declared, “A perfect martini should be made by filling a glass with gin, then waving it in the general direction of Italy.”

Now it becomes an issue of when rather than where. Although the practice of aromatizing fortified wine with botanicals reaches back into prehistory (like drinking itself!), the modern version of what we call vermouth was developed relatively recently, in 18th-century Turin. This fact would seem to point us towards an Italian etymology. Another piece of inconclusive but suggestive evidence lies in the point that in the year 1863, an Italian vermouth maker began marketing its product under the brand name of capital-M Martini, leading some to speculate that the brand name might be the source of the cocktail’s name.

I submit that the preponderance of evidence nudges us towards an Italian nomenclature, rather than a Latin one. Therefore, I drink a martino. Then again, the use of -i to pluralize Latinate words ending in -us is so widely recognized and understood that I would argue the use of “martinus” is equally acceptable. Perhaps the ultimate solution, my friends, is to always order more than one.

Published on February 23, 2015 12:58

January 29, 2015

Book Giveaway! And a Podcast Interview.

Guess what? We're doing a book giveaway! Right here on Goodreads! Want to win a FREE copy of

Crass Casualty

(Book II in the Victoria da Vinci series)? Enter to win!

Good luck!

Back in December, I was one of several local writers interviewed by arts journalist and event organizer extraordinaire Tiffany Razzano for Episode #13 of the Wordier Than Thou show on Life Improvement Radio. The subject was writing goals for 2015. It's very interesting to hear different perspectives on how we work and how we structure our objectives. (You'll hear me say I was hoping to get Crass Casualty finished by February; I'm pleased to report that I beat that deadline by two weeks!) If you're interested, click HERE to listen to the entire podcast.

Published on January 29, 2015 09:53

January 22, 2015

The Joy of Being Finished

Wow. That's all. Just wow.

Not an extravagantly articulate way to wax rhapsodic about how good it feels to be done, but there you have it.

I began Crass Casualty in December of 2013, just a few weeks after Dicing Time for Gladness went on the market. I had the benefit of knowing the entire story arc at that point, so with the boost of momentum provided by good sales and reviews of the first book, I finished it in 14 months.

That was 14 months of constant writing and re-writing. Novelists (and the spouses of novelists) know that I am not engaging in exaggeration by using the word "constant." When a manuscript is in progress, the writer is always writing. The body might be at a cocktail party, but the mind is composing and editing. That was 14 months consumed by obsessive research into strange and arcane little details, 14 months of seemingly endless revisions, followed by revisions to revisions.

But with each successive draft, the changes got smaller and smaller. Eventually I was playing around with subtle points of punctuation and trying to decide whether this pause warranted a sentence break or a paragraph break. Paragraph. No, sentence. No, paragraph.

Once you realize you are fiddling with tiny, nit-picky things (and especially when you realize you have made and then un-made the same minor alteration four successive times), you must embrace the fact that the time has come to abandon your tinkering, untie the dock lines and let it float out to sea. It's not perfect; it will never be perfect. But it's complete, and that's enough.

I have promised myself that I would take a break now. Hate's Profiting, book III in the series and the final installment in the Victoria da Vinci trilogy, has already been created as a Word file on my computer and is already about 20 pages long (mostly notes and ideas), but I'm not even going to open it until March 1st.

Really.

Not an extravagantly articulate way to wax rhapsodic about how good it feels to be done, but there you have it.

I began Crass Casualty in December of 2013, just a few weeks after Dicing Time for Gladness went on the market. I had the benefit of knowing the entire story arc at that point, so with the boost of momentum provided by good sales and reviews of the first book, I finished it in 14 months.

That was 14 months of constant writing and re-writing. Novelists (and the spouses of novelists) know that I am not engaging in exaggeration by using the word "constant." When a manuscript is in progress, the writer is always writing. The body might be at a cocktail party, but the mind is composing and editing. That was 14 months consumed by obsessive research into strange and arcane little details, 14 months of seemingly endless revisions, followed by revisions to revisions.

But with each successive draft, the changes got smaller and smaller. Eventually I was playing around with subtle points of punctuation and trying to decide whether this pause warranted a sentence break or a paragraph break. Paragraph. No, sentence. No, paragraph.

Once you realize you are fiddling with tiny, nit-picky things (and especially when you realize you have made and then un-made the same minor alteration four successive times), you must embrace the fact that the time has come to abandon your tinkering, untie the dock lines and let it float out to sea. It's not perfect; it will never be perfect. But it's complete, and that's enough.

I have promised myself that I would take a break now. Hate's Profiting, book III in the series and the final installment in the Victoria da Vinci trilogy, has already been created as a Word file on my computer and is already about 20 pages long (mostly notes and ideas), but I'm not even going to open it until March 1st.

Really.

Published on January 22, 2015 15:23

January 5, 2015

Answering the Inevitable Questions

"So, what's your book about?"

It's a perfectly reasonable question, of course. So why are most novelists stumped by it? I know I always am. I tweeted about this conundrum and the response I got from other writers was, "I know, right?"

The problem is that we have so much to say about our own work that we never know where to begin. We certainly don't know where to stop.

I wrote an entire blog about the primary overarching symbolism in Dicing Time for Gladness, as well as an entire second blog about recurring themes within the narrative, so clearly I can (and do) prattle on endlessly about it. But a rambling, self-indulgent monologue about your big ideas is not what your friend is looking for.

Neither is a plot synopsis. Listening to someone summarize a storyline is almost as boring as listening to someone recall a weird dream they had last night.

You might be tempted to recite the blurb from the back cover, but unless you do it ironically using a Hollywood voice-over delivery, it will just sound silly. Actually, it will sound silly anyway, but if you do it that way at least it might be slightly funny.

What's the solution? HAVE AN ANSWER READY.

Your answer should be no more than a sentence long. It should consist of two elements:

(1) The genre

(2) The premise

That's all they're looking for here. Chances are, they were just making polite conversation anyway.

Example:

"So, what's your book about?"

"It's a cyberpunk romance set in a dystopian future, centered around a teenage pastry chef with a robotic arm who falls in love with a girl who has inherited a magic whisk, and together they use it to overthrow the government."

Don't try to unpack all the layers of meaning and the nuances of the character arcs. Now is not the time for that. (When Terry Gross is interviewing you on "Fresh Air," that will be the time.) Remember, this stranger at the bar is just making small talk.

"Awesome! Where can I get a copy?"

First of all, suppress your impulse to say, "are you not familiar with how to use Amazon? Type in the title and/or author (me) and you will find it in under ten seconds. It's not brain surgery, dumbass."

Whoa, there! Lose the attitude, Angsty Author. I know you're living in a world of shattered dreams and you spend a lot of time crying alone in the dark (we all do), but that is not this person's fault. This person is probably just being nice. Therefore, be rightfully flattered by the question and reply with a smile that conceals your inner suffering and rage. "It's available on Amazon in print and e-reader editions. Just enter my name, Brianne Torchwood Hufflepuff, and it will take you to my author page. All my novels are there, along with free previews." (You do have an Amazon author page, don't you? Of course you do.)

An even better way to handle this is to offer the person one of the business cards you have handy while making the statement above.

Unfortunately, instead of the previous question, the person might ask this alternate version:

"Awesome! Can I have a copy?"

Instead of getting pissy and explaining that you are trying to make a living here, dammit, and pointing out how rude it would be to casually ask for a free haircut or a free massage, simply respond with the exact same answer you would have given if the person had asked where to buy it. If the person persists in pestering you for a free one, just say you're all out. (I once had a random person challenge me on this, saying, "don't you get a bunch of free copies?" I explained that, darn the luck, I had just handed out my very last book at a signing a couple of days earlier. Conveniently, this was true.)

Then there is this:

"Is it a best-seller?"

You have several options here.

(A) "It's my best-seller so far!" Bonus points if it's true. Double bonus points if it's your only book.

(B) "No, the world isn't ready for my genius. But it will be required reading in high school 100 years from now."

(C) "Yes. Do you not recognize me from television?"

(D) Sobbing and binge drinking.

And my personal favorite:

"Are they going to make it into a movie?"

This is when you know you are wasting your time talking to this person, so you can use my standard response. "They already did. But they made a few changes to the story, and re-named it The Hunger Games."

Published on January 05, 2015 04:55

January 4, 2015

Crazy People in History #1

Let's face it: crackpots are fun to read about. Today I'll tell the short, weird story of Dr. Ed. Not only did Dr. Ed try to redefine pi, by golly he was determined to monetize it.

Writing Dicing Time for Gladness (which came out in November of 2013) and Crass Casualty (which should be released in about two weeks) involved a lot of historical research, an activity which can take you down some pretty interesting wormholes, strewn with a panoply of eccentric characters.

Dicing Time for Gladness takes place primarily in Chicago in the year 1899, and Crass Casualty takes place mostly in and around Paris the following year. Even though these stories belong to the historical science-fantasy adventure sub-genre — and I like to call special attention to the fact that out of those four words, only one is "historical" — I do enjoy reading about the true history of the time and place I'm writing about, both for creative inspiration and as a source of period detail. (I blogged about the tension between reality vs. make-believe in my fiction in this post.)

A lot of the strange stuff I dig up ultimately does get incorporated into the story one way or another, often as a throwaway reference. Some things, however, just don't fit into the plot in any logical way, so they don't get used.

This blog is about one of those things: a funny and 100% real event that took place very close (both chronologically and geographically) to the setting of Dicing Time for Gladness .

First, a little background. "Squaring the circle" is a mathematical exercise, a problem proposed by ancient practitioners of geometry.

The original challenge was to start with a circle and then construct a square with the same area, using only a compass and a straightedge. Also, it had to be possible with a finite number of steps; you couldn't cheat and say "and then I repeat this process an infinite number of times" to make it work.

At the time, the axioms of Euclidean geometry — which were still steeped in magic and mystery in those days — suggested that this might not be possible at all, but no one knew for sure yet.

Today, of course, we all know that if you divide the circumference of a circle by the diameter of the circle, you get a number called pi, and that pi is both an irrational and a transcendedal number. I'm not speaking poetically here. "Irrational" in this context simply means that it cannot be exactly expressed as a common fraction and "transcendental" means that it is not algebraic (i.e., it is not a root of a non-zero polynomial equation with rational coefficients). No matter how powerful your computer is, you can calculate pi to the zillionth decimal place and you will never find an exact value for it. It just goes on and on.

This characteristic of pi, its transcendence, basically implies that it is impossible to solve the ancient challenge of squaring the circle with a compass and straightedge. It simply cannot be done. You can approximate it, of course, but you can't actually complete the challenge according to the rules.

The transendence of pi was proven in 1882 with the publication of the Lindemann–Weierstrass theorem. Proving the transendence of pi effectively proved the impossibility of squaring the circle, and the phrase "squaring the circle" soon came to mean "attempting to do something impossible."

If you're still reading (bravo!), you're probably wondering where the hell I'm going with this. This is not a blog about math. This is a blog about crazy people with a lot of self-confidence.

Our story begins in the state of Indiana in the year 1894, when a physician and enthusiastic amateur number-twaddler named Edward J. Goodwin decided that he had "discovered" a way to square the circle. Oh, sure — it required pi to be a flat 3.2, which is technically what all those fancy college eggheads refer to as "wrong," but that did not discourage Dr. Ed.

Like so very many nutjobs before and since, Dr. Ed was not troubled by self-doubts. He submitted his "solutions" for squaring the circle, trisecting the angle and doubling the cube to the American Mathematical Monthly, who politely printed his claims along with a note explaining that they were only including them in their journal because he asked them to.

Now convinced that he had solved problems which (in his own words) "had been long since given up by scientific bodies as unsolvable mysteries and above man's ability to comprehend," Dr. Ed took his "discovery" to Taylor I. Record, Representative from Posey County to the Indiana General Assembly. (Dr. Ed lived in Posey County, in a place called Solitude. Really.) It wasn't enough that he had advanced human knowledge with his brilliance. He wanted to make it statutory.

Dr. Ed wanted to license these new facts for use in textbooks. He would receive royalty payments from schools around the United States who used them. Except schools in Indiana, of course. They could use them for free.

Instead of saying, "get out of my office, you obvious lunatic," in 1897 Representative Record introduced bill #246 to the floor of the Indiana General Assembly. It was not the first time people had attempted to establish scientific facts by legal decree, but it was probably one of the most ridiculous.

Representative Record was a good choice. He was not well versed in formal math. Aside from being a farmer, he was, according to Purdue University's Web site, "a timber and lumber merchant." The site goes on to note that Representative Record did not have a long and illustrious government career; apparently the 1897 legislative session occurred during the only term he ever served.

If it was amazing that Dr. Ed ever got anyone to listen to him at all, let alone a state representative, it was even more astounding that the bill went before the Committee on Education, which seemed to like it, and the bill passed the full House on February 6th without a single dissenting vote, 67-0.

But before you lose all hope in American democracy, this is where the story takes a turn. Purdue University Head Professor of Mathematics C. A. Waldo happened to be in Indianapolis at the time. (He was there to secure the annual appropriation for the Indiana Academy of Science, of which he was a charter member.) Professor Waldo immediately recognized three things:

(1) You cannot legislate the relationship of the diameter of a circle to its circumference.

(2) You cannot impose fees on the teaching or use of mathematical facts.

(3) Edward J. Goodwin's "breakthrough" was a bunch of self-contradictory mumbo-jumbo that violated the fundamental principles of sixth-grade geometry.

By now, the news had already gotten out. Never missing a chance to make fun of Indianapolis, The Chicago Tribune wrote that "the immediate effect of this change will be to give all circles when they enter Indiana either greater circumference or reduced diameter. An Illinois circle or a circle originating in Ohio will find its proportions modified as soon as it lands on Indiana soil."

Professor Waldo got to the Indiana Senate before bill #246 did, and it was quietly killed. If not for Professor Waldo, Indiana's "Pi Law" might have joined the illustrious pantheon of spectacularly stupid legislation still on the books in the United States today.

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Popular recent posts:

Martinus or Martino?

The Joy of Being Finished

Answering the Inevitable Questions

Sleeping With My Editor

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

My author page:

www.AustinScottCollins.com

Writing Dicing Time for Gladness (which came out in November of 2013) and Crass Casualty (which should be released in about two weeks) involved a lot of historical research, an activity which can take you down some pretty interesting wormholes, strewn with a panoply of eccentric characters.

Dicing Time for Gladness takes place primarily in Chicago in the year 1899, and Crass Casualty takes place mostly in and around Paris the following year. Even though these stories belong to the historical science-fantasy adventure sub-genre — and I like to call special attention to the fact that out of those four words, only one is "historical" — I do enjoy reading about the true history of the time and place I'm writing about, both for creative inspiration and as a source of period detail. (I blogged about the tension between reality vs. make-believe in my fiction in this post.)

A lot of the strange stuff I dig up ultimately does get incorporated into the story one way or another, often as a throwaway reference. Some things, however, just don't fit into the plot in any logical way, so they don't get used.

This blog is about one of those things: a funny and 100% real event that took place very close (both chronologically and geographically) to the setting of Dicing Time for Gladness .

First, a little background. "Squaring the circle" is a mathematical exercise, a problem proposed by ancient practitioners of geometry.

The original challenge was to start with a circle and then construct a square with the same area, using only a compass and a straightedge. Also, it had to be possible with a finite number of steps; you couldn't cheat and say "and then I repeat this process an infinite number of times" to make it work.

At the time, the axioms of Euclidean geometry — which were still steeped in magic and mystery in those days — suggested that this might not be possible at all, but no one knew for sure yet.

Today, of course, we all know that if you divide the circumference of a circle by the diameter of the circle, you get a number called pi, and that pi is both an irrational and a transcendedal number. I'm not speaking poetically here. "Irrational" in this context simply means that it cannot be exactly expressed as a common fraction and "transcendental" means that it is not algebraic (i.e., it is not a root of a non-zero polynomial equation with rational coefficients). No matter how powerful your computer is, you can calculate pi to the zillionth decimal place and you will never find an exact value for it. It just goes on and on.

This characteristic of pi, its transcendence, basically implies that it is impossible to solve the ancient challenge of squaring the circle with a compass and straightedge. It simply cannot be done. You can approximate it, of course, but you can't actually complete the challenge according to the rules.

The transendence of pi was proven in 1882 with the publication of the Lindemann–Weierstrass theorem. Proving the transendence of pi effectively proved the impossibility of squaring the circle, and the phrase "squaring the circle" soon came to mean "attempting to do something impossible."

If you're still reading (bravo!), you're probably wondering where the hell I'm going with this. This is not a blog about math. This is a blog about crazy people with a lot of self-confidence.

Our story begins in the state of Indiana in the year 1894, when a physician and enthusiastic amateur number-twaddler named Edward J. Goodwin decided that he had "discovered" a way to square the circle. Oh, sure — it required pi to be a flat 3.2, which is technically what all those fancy college eggheads refer to as "wrong," but that did not discourage Dr. Ed.

Like so very many nutjobs before and since, Dr. Ed was not troubled by self-doubts. He submitted his "solutions" for squaring the circle, trisecting the angle and doubling the cube to the American Mathematical Monthly, who politely printed his claims along with a note explaining that they were only including them in their journal because he asked them to.

Now convinced that he had solved problems which (in his own words) "had been long since given up by scientific bodies as unsolvable mysteries and above man's ability to comprehend," Dr. Ed took his "discovery" to Taylor I. Record, Representative from Posey County to the Indiana General Assembly. (Dr. Ed lived in Posey County, in a place called Solitude. Really.) It wasn't enough that he had advanced human knowledge with his brilliance. He wanted to make it statutory.

Dr. Ed wanted to license these new facts for use in textbooks. He would receive royalty payments from schools around the United States who used them. Except schools in Indiana, of course. They could use them for free.

Instead of saying, "get out of my office, you obvious lunatic," in 1897 Representative Record introduced bill #246 to the floor of the Indiana General Assembly. It was not the first time people had attempted to establish scientific facts by legal decree, but it was probably one of the most ridiculous.

Representative Record was a good choice. He was not well versed in formal math. Aside from being a farmer, he was, according to Purdue University's Web site, "a timber and lumber merchant." The site goes on to note that Representative Record did not have a long and illustrious government career; apparently the 1897 legislative session occurred during the only term he ever served.

If it was amazing that Dr. Ed ever got anyone to listen to him at all, let alone a state representative, it was even more astounding that the bill went before the Committee on Education, which seemed to like it, and the bill passed the full House on February 6th without a single dissenting vote, 67-0.

But before you lose all hope in American democracy, this is where the story takes a turn. Purdue University Head Professor of Mathematics C. A. Waldo happened to be in Indianapolis at the time. (He was there to secure the annual appropriation for the Indiana Academy of Science, of which he was a charter member.) Professor Waldo immediately recognized three things:

(1) You cannot legislate the relationship of the diameter of a circle to its circumference.

(2) You cannot impose fees on the teaching or use of mathematical facts.

(3) Edward J. Goodwin's "breakthrough" was a bunch of self-contradictory mumbo-jumbo that violated the fundamental principles of sixth-grade geometry.

By now, the news had already gotten out. Never missing a chance to make fun of Indianapolis, The Chicago Tribune wrote that "the immediate effect of this change will be to give all circles when they enter Indiana either greater circumference or reduced diameter. An Illinois circle or a circle originating in Ohio will find its proportions modified as soon as it lands on Indiana soil."

Professor Waldo got to the Indiana Senate before bill #246 did, and it was quietly killed. If not for Professor Waldo, Indiana's "Pi Law" might have joined the illustrious pantheon of spectacularly stupid legislation still on the books in the United States today.

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Popular recent posts:

Martinus or Martino?

The Joy of Being Finished

Answering the Inevitable Questions

Sleeping With My Editor

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

My author page:

www.AustinScottCollins.com

Published on January 04, 2015 11:52

November 28, 2014

The First Draft of Book II Is Finished!

It took me three years to write the first book in the Victoria da Vinci trilogy,

Dicing Time for Gladness

(although to be fair working on that project was not my number-one priority for much of that time). I mention this now because as of just a few minutes ago, I NOW HAVE A FINISHED FIRST DRAFT OF BOOK II. I don't bust out the obnoxious all-caps maneuver very often, but I'm feeling exultant.

As I discussed in this blog post, writing a sequel poses special challenges. On the other hand, however, as I explained in the same post, it can be easier than starting with a blank piece of paper if your over-arching story is already well mapped out. I severely doubt that I could have written this story from scratch in 12 months.

There is still a lot of work to do: editing, proofreading and the usual endless massive revisions. No manuscript is ever truly finished; you just get to a point where you feel compelled to abandon it. I once had a writing coach who said it was time to quit re-writing when you find yourself adding and then subtracting the same comma over and over again.

But I'll worry about that later. For the moment I am celebrating with a toast. The first draft came out to 240 pages and 51,718 words, almost exactly the same as Book I, so I expect it to swell up by about the same amount (another 20-30 pages) by the time I'm done fleshing out details in places where I skimmed on the first pass.

When Dorothy Parker was asked to name the two most beautiful words in the English language, she quipped that she was partial to "cheque" and "enclosed." If I had to choose three, I think that "finished first draft" might be my picks.

As I discussed in this blog post, writing a sequel poses special challenges. On the other hand, however, as I explained in the same post, it can be easier than starting with a blank piece of paper if your over-arching story is already well mapped out. I severely doubt that I could have written this story from scratch in 12 months.

There is still a lot of work to do: editing, proofreading and the usual endless massive revisions. No manuscript is ever truly finished; you just get to a point where you feel compelled to abandon it. I once had a writing coach who said it was time to quit re-writing when you find yourself adding and then subtracting the same comma over and over again.

But I'll worry about that later. For the moment I am celebrating with a toast. The first draft came out to 240 pages and 51,718 words, almost exactly the same as Book I, so I expect it to swell up by about the same amount (another 20-30 pages) by the time I'm done fleshing out details in places where I skimmed on the first pass.

When Dorothy Parker was asked to name the two most beautiful words in the English language, she quipped that she was partial to "cheque" and "enclosed." If I had to choose three, I think that "finished first draft" might be my picks.

Published on November 28, 2014 20:33

Upside-down, Inside-out, and Backwards

My blog about books, writing, and the creative process.

- Austin Scott Collins's profile

- 28 followers