Gareth E. Rees's Blog, page 4

November 12, 2020

The Eerie Tale of the Zombie Junction Behind Sainsbury’s Car Park

LOCATION: St Leonards, East Sussex

WORDS & PHOTOS: Gareth E. Rees

At the end of Lockdown#1, I ventured out to a supermarket for the first time.

St Leonards Sainsbury’s is on the busy A21 where it leaves town, nestled among a petrol station, McDonalds, Premier Inn and Toyota showroom.

The expected retail outliers on the urban edge.

We parked up but I didn’t go inside the supermarket. Too much plague for me.

Instead, my girlfriend went in, all masked up like a bandit, while I took a walk around the car park.

My book Car Park Life had come out six months prior. It was all about my adventures walking through Britain’s retail car parks.

But I’d not touched a car park since.

I’ll be frank with you – I was absolutely sick of car parks.

So I got really, really bored of walking around this one.

“I AM DONE WITH THIS,” I said, in my mind, to nobody in particular.

“BOLLOCKS”, I thought, as I looked at a bollard.

“THERE IS NOTHING LEFT TO SAY”, I yelled at a discarded Coke can in a trolley bay. “I AM A SPENT FORCE”.

As I returned to the store front, I noticed that they’d created a buffer zone of inverted trolleys, lined up in rows, like a skeleton army ready to attack.

This was new.

Not good, but new.

Maybe I wasn’t done with car parks yet.

Car Park Life: The Apocalypse.

It had a nice ring to it. Better than…

Car Park Life II: Electric Boogaloo.

Beside the cash machines, Roley the Steamroller looked visibly distressed by Bob the Builder’s early return to work – particularly as he wasn’t wearing PPE.

Beyond this tense scene was an alleyway. It ran alongside the store, by some rat traps and discarded shopping baskets, where it met a muddy slope.

Curious to see where it led, I ascended towards a woodland, where I followed a footpath through the trees, then out into open ground.

As I emerged, blinking in the sunlight, I found myself somewhere else entirely.

Before me was an abandoned road junction, consisting of an overgrown roundabout with truncated access roads that led to nowhere.

Round and round went nothing.

Nothing, with nowhere to go.

It was as if I’d walked into a Lockdown metaphor…

….a turgid urban frustration dream….

….the fevered memories of a moribund psychogeographer on his sick bed.

“Mmmm…. uhhh… abandoned junction… urrrr…. ah…. desolate roundabouts…. mmm…. uhhhh…. rusted drain covers….”

Sloping embankments to either side of the roundabout were weedy and green, dotted with yellow flowers. Tall weeds sprouted along verges of sun-baked mud, littered with energy drink cans.

Then, suddenly, I saw movement.

A shivering of leaves down below, where the scrubland met the trees.

Very slowly, a middle aged woman crawled on her hands and knees out of the undergrowth.

She got to her feet, rubbed herself down, then began shambling down the path, like a zombie.

Moments later, another woman appeared on the path, and began following at a consistent distance, never catching up.

Soon they both vanished around a corner.

Where could they possibly be going out here, in this aborted place?

I strode up the middle of the empty road, between the swaying weeds towards another – active – roundabout where the occasional car whooshed past.

But I didn’t go that far.

Instead, I turned abruptly and hopped over the metal barrier.

I plunged down the verdant slope of thistles and buttercups towards the spot where the zombie women had vanished.

For a while I circled around the embankment, through a shabby countryside in the lee of the sliproad scree slopes.

There was an apocalyptic feel to this place, patrolled by the undead.

I had to assume that I was the exception – that I was still alive.

There was no sign of the zombies, but there was a low, arched tunnel in the earthwork of the junction, with ribbed pipes protruding from the black chasm like the arms of giant robot octopus.

I entered the gloom, and stayed for a while in the cool, letting my eyes adjust.

It had only been 10 minutes, but already I’d begun to forget about Sainsbury’s, and my girlfriend shopping inside the virus-infested supermarket.

I was far away from all that now.

Things had changed.

I was now a troglodyte beneath an unfinished junction, on the lookout for undead creatures in the scrubland.

My mobile phone started to ring but I didn’t want to answer it.

It all seemed a bit pointless, that life I left behind.

This wasn’t so bad.

The lush green fronds of the wasteland were pretty in the sunshine. The breeze in the tunnel was cool. Crows sang to me from distant trees. The piping was comfortable to sit on.

Perhaps I could stay here for a while, and ride out pandemic for as long as possible.

Whenever I was hungry, I might feast on the occasional curious visitor as they emerged, confused, from the supermarket car park.

Nights, I’d sleep safe in the tunnel.

Days, I’d join my middle-aged undead comrades as we foraged for rats and berries in the undergrowth.

FOR MORE WEIRD TRIPS THROUGH JUNCTIONS, ROUNDABOUTS, FLYOVERS AND RINGROADS, CHECK OUT UNOFFICIAL BRITAIN; JOURNEYS THROUGH UNEXPECTED PLACES

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Gareth E. Rees is author of Unofficial Britain (Elliott & Thompson, 2020) Car Park Life (Influx Press 2019), The Stone Tide (Influx Press, 2018) and Marshland (Influx Press, 2013).

November 11, 2020

The Banshee and the Roundabout: Bizarre stories & folklore today

Unofficial Britain’s Gareth E. Rees in conversation with Irish storyteller Helena Byrne and place writer Marcel Krueger. They discuss the importance of folklore in modern times; the bizarre stories generated by urban environments and the differences (and similarities) between contemporary Irish and British folklore.

Near the end of the talk, they are interrupted by a mischievous digital prankster sprite who tries to knock them off their stride with erotic interjections. Not to be missed.

ABOUT THE SPEAKERS:

Gareth E. Rees’s new book Unofficial Britain: Journeys Through Unexpected Places is available in hardback now via Amazon, Waterstones, Hive, and your local bookshop.

You can hear, see and find out more about Helena Byrne’s work on her website here.

Marcel Krueger’s Iceland – a Literary Guide for Travellers is available to buy online and from all good indie bookshops.

November 6, 2020

Nothing With Nothing: A Lonely Drift Down Marine Drive, Margate

LOCATION: Margate, Kent

WORDS: An extract from ‘Nothing With Nothing’ by Emilia Ong

PHOTOS: Emilia Ong

I didn’t go to the Main Sands but most people did.

The day-trippers came seeking sand and sea air, deep fried fish and swiftly liquefying ice cream; this much had not changed in a century.

Some came for the Art, of which it was whispered there had been a resurgence in recent years. Unless it was of oils and sunsets however, the Art was hidden away; I couldn’t say where exactly. In back lanes and repurposed warehouses I imagined; inside the spun-out minds of those who kept their bodies bound indoors.

Because one could not see the Art, because there was something extra, something other, which was there but not there, suffusing the atmosphere and conferring Reputation, this place was called cool.

Cool because of the something-beyond the poky glass-fronted shops with their dappled landscape prints and wooden seagulls and promises of fudge; cool because of the something outside of the big Gallery, which had planted itself at the town’s most desirable tip with its haughty announcement that that something-beyond lay, in fact, within its spanking white walls. Well, doubtless there was something going on.

Cool, I thought: such a status couldn’t have come from nowhere.

So yes, the place was fashionable – newly, sneakily so. Art’s enigma rolled along the streets, weaving in and out of the crushed cans and polystyrene. Often old chairs, browned mattresses, smashed TV sets, could be found lolling on the pavements. Because of the enigma, these looked like part of the Art too. The vision of junk ran down my glassy eyes stickily, like the albumen of broken eggs. Daily I picked my way through the shells.

*

I didn’t go to the Main Sands, but I could see them from my bedroom window. Perhaps it was because I could see them that I didn’t go. I had moved here for reasons of frugality – that, and to get away from all which, I felt, had barbarised me for years.

The air! The sea! The view! These were what would heal me.

However, after a week or two, such ludicrous displacements dissolved away. The air was too fresh, the wind too biting. The sea was simply there, day in and day out, its tides rising and falling with the same mockery as the need to shower and to eat. Time took on the mantle of repetition, replacing its old veil called Loss and Decay: where repetition is in residence nothing can be escaped, and nor does one wish to escape.

Round and round went the days, and in their unwavering similitude they became encrusted with a sort of meaning. I delighted in their crispness, in the same way that the brittle edges of the overly thick pancakes I fried compensated for the stodgy centres. There was no sense to a thing in and of itself, I thought, if it was denied repetition. Repetition, I decided, was the very foundation of thought itself – and this, even if it laughed at you.

Sometimes I would want to do nothing and sometimes I would want to do Everything and there was nothing in-between.

I was reflecting on this one day as the sun went down. It had been what people called a Pleasant day and because of this many had gathered on the steps which had been erected at one end of the beach, making of the sky a stage, of the steps an amphitheatre.

It was charming in a black kind of way to see them from my window – mere specks dotted all over the concrete – and it was blackly charming, too, to later wander along Marine Drive and find myself weaving amid the drunks who had had a rather heavy session in Wetherspoons.

Every day I went along Marine Drive because there was nowhere to go but along Marine Drive. This route took me past the Main Sands. But I did not look towards the ocean. Instead I looked the other way, towards a long line of arcades. The assault was swift: colours and lights blared onto the pavement; grins and hollers tripped on them. I had only to pass the car park and the shut-up casino – whose mirrored doors continued to command that one go ‘THIS WAY’ in spite of smaller signs which thanked in a concluding manner former customers for their business – in order to reach them.

Many fingers had rubbed FUCKs and GO HOMEs into the grime which caked the casino’s untended doors (just who was to Go home had always, by the time I saw it, been overwritten so many times that the original object was indecipherable) and so, having by the time I arrived at their lurid carnival taken in the strength of the ire which the people of this town saw fit to broadcast, I would discover that I was in no mood to observe possibly the very same people engaged in the tumultuous pursuit of electronic, competitive glory.

As I walked past the arcades, people eyed me and I looked back at them; I looked at them looking at the arcades, and I looked at them playing in them. My looking was intended to circumvent their looking at me, but the most unabashed examination could do nothing to put these inspectors off.

In prime position, and inching presumptively into the street proper, nosed several cumbersome machines, of which two commanded particular esteem in the eyes of passers by.

One was replete with a complex-looking platform, upon whose surface women – for they were uniformly women – threw their weights; this machine played loud pop music (never quite the latest songs), and upon its screen flashed neon arrows, pointing up or down, right or left. The Amusement was called the ‘DanceMaster’, or possibly the ‘DanceMonster’; I forget. Players were required to hurl their feet at the corresponding arrows on the platform. Their arms, redundant when it came to the game proper, would be vaguely bent, held out from their sides like cowboys ready to draw weapon from holster. As soon as their feet touched – hammered – into the specified arrow, a new arrow would flash, and their bodies would jerk, wireless puppets, to chase the latest, usurping, instruction.

Backing onto the DanceMaster was one for the boys: this comprised a screen and two enormous guns. The guns mimicked machine guns, were near two-foot long and attached to the device by thick snaking ropes; frequently the plastic mock-ups dwarfed the weedy, sun-starved teens who gripped them, brows furrowed and legs splayed beneath their torsos. They slanted their torsos towards the screen in eagerness of the shoot: there was no sarcasm to this machine. Only, I thought, the hardest and most adhesive variety of rage. The boys would stare into the screen, enchanted.

I was alert for the slightest indication of a lurch: players tended to pitch suddenly either forwards or back, and it was not unusual for me to only narrowly miss outright collision.

Once I nearly stepped on a player’s untended scrap of a dog. Ferfuhkssay, he hollered at my shrinking back. In response, my eyes flicked towards the clock tower, which loomed diagonally across the road. Its hands had stopped shortly after my arrival, and the council was taking its own sweet time about restarting them, meaning that the clock tower posed merely as a redundant relic.

One day I looked up to find it’d been clad in scaffold: surely a harbinger, I thought, of imminent change. But several weeks went by, and neither a tick nor a tock was in evidence. Everything came from the void, I thought, and absence made the heart grow stronger.

I only wanted to be left alone.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Emilia Ong is a British writer, born in Hackney, London, in 1983 to an English father and Chinese-Malaysian mother. A now ex-English teacher with a degree in philosophy, she is currently working on her first novel. For more information about Emilia’s work, please take a look at her website, www.emiliaong.com Or follow her on Twitter: https://twitter.com/e_o_n_g_

October 31, 2020

Ghostspaces Where the Bombs Once Fell

LOCATION: Sheffield

WORDS & IMAGES: Deeana Violet

This city was burned to the ground in 1942.

Or perhaps that’s hyperbole, as it didn’t quite take the blitz that Coventry did, but it’s certainly the story that’s told.

Steel mills were vital targets for bombing raids. I imagine them coming out of that Peak night, droning fear of engines echoing over those huge spaces, the big skies of Big Moor.

Many bombs missed the steel mills to devastate the city centre, which is half the reason that this city doesn’t have many truly old buildings. The other half concerns council policy from about 1950 onwards.

I grew up with concrete and steel. Towers and offices that looked like castles, fortresses in some reworking of medieval times, with windows shaped like arrow slots. Sheffield lost its castle in the civil war and I think we’re always looking for it, dreaming of what we should have had, but for Cromwell’s forces and a lot of gunpowder.

In a world with very little that’s old, ghosts have to fill in the spaces that are left.

And there were plenty of those…

Terraced housing estates survived, here and there, their passages and entries filling with shapes of things unknown. There’s a story about a red eyed beast that waited in the shadows of the old steel district. It spied on courting couples and threw metal garden forks at them. It ran along rooftops and through attics.

This was not the first time either…

Before the war burned this city, a white caped fiend did exactly the same. There’s also an account of a blue-eyed version – a hairy creature running along the rail lines that carried coal and steel between sleeping houses, late, late at night.

My school was on the site of an old medical waste dump. Black mould; tannoys; tall heating chimneys; floodlights. A grey all-weather sports pitch like the surface of the moon. Encroaching wild woodlands from the city limits. Adisintegrating housing estate that faded out into abandoned farmland.

Two underpasses below the urban motorway that we had to cross, one filled with graffiti and danger, the other peaceful and almost unused.

We filled these spaces with ghosts too. The boy who died here. Devils rattling windows in the English corridor and leaving enigmatic satanic messages. A child in Victorian school uniform, an unlikely revenant given that there was no school within miles of this site until 1963.

We were, like everyone, desperate for the old stories of the dead returning to carry on their conversations, in the darkness around the edges of this city’s sodium glare.

There can be magic and fear anywhere, even in an urban futurescape.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Deanna Violet lives in Sheffield and it shows. She grew up listening to stories about the city’s secret past and got obsessed with its mysteries. Her dad once showed her how to turn street lights on, and her mum met a ghost on the stairs. You can read this full version of this post plus more of her work on her website, Crow Violets.

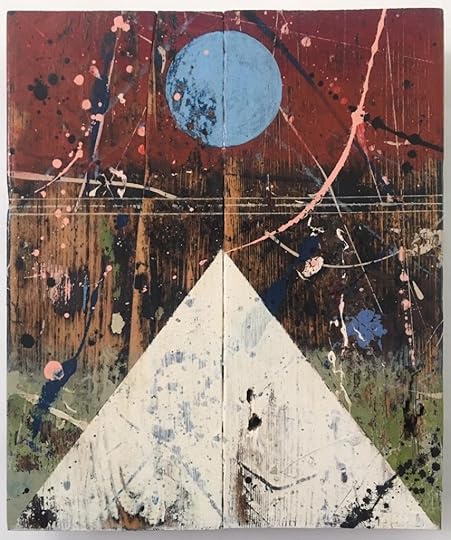

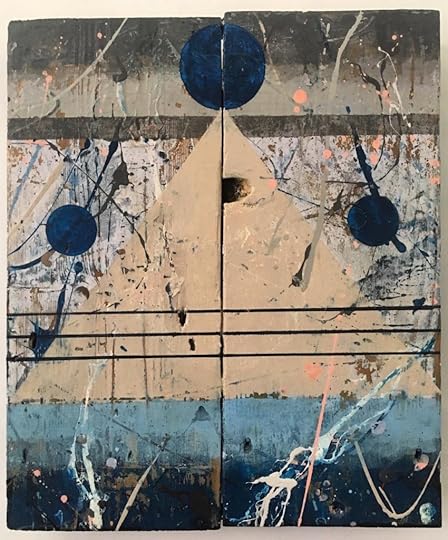

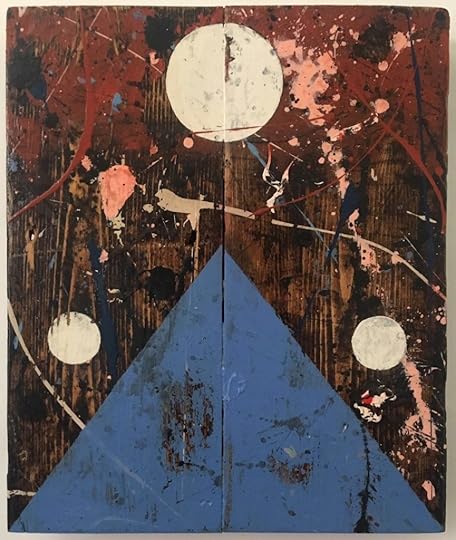

October 2, 2020

Edgeland Visions

LOCATION: London (the edge of)

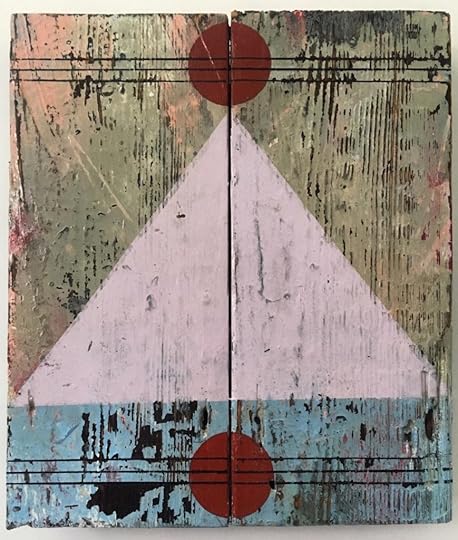

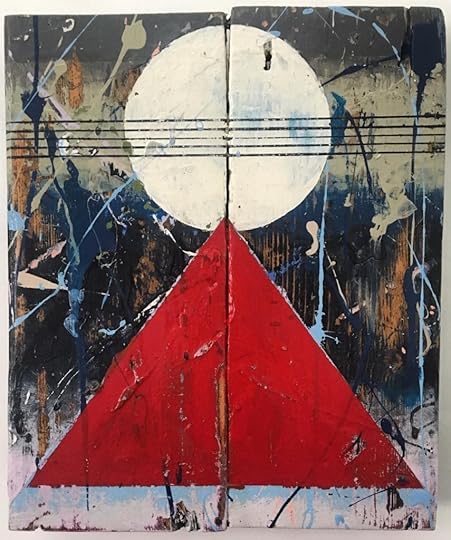

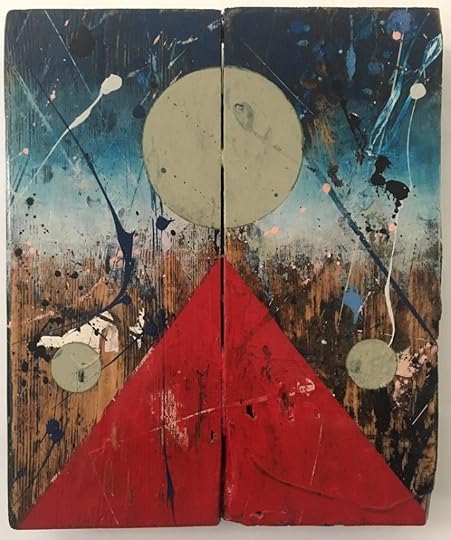

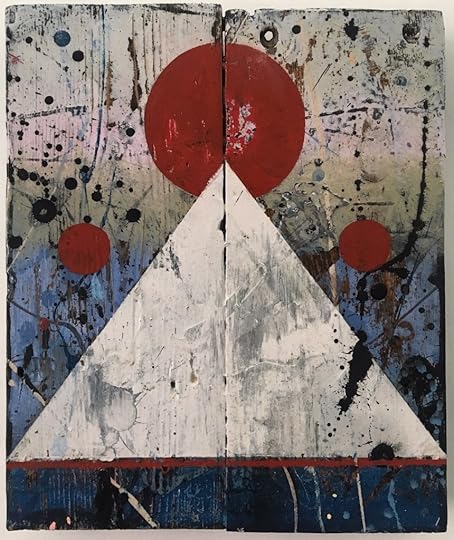

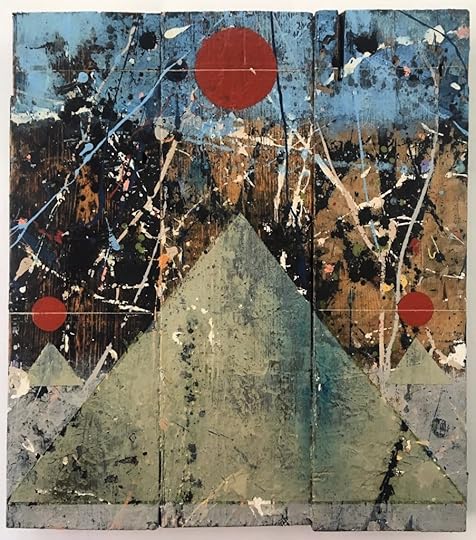

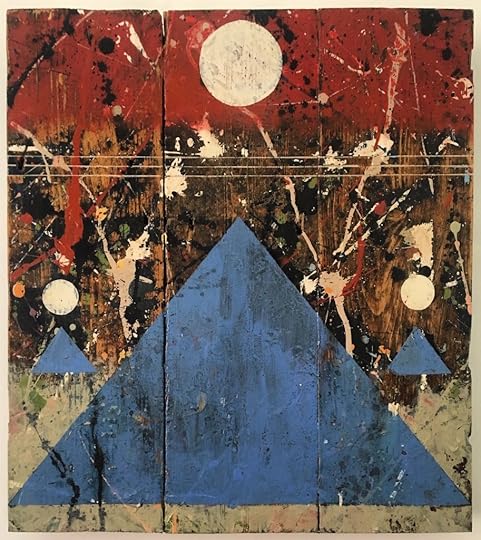

Matt Healy is a London born artist who works and lives in Folkestone.

In his ‘Edgeland Vision’ series he explores liminal urban spaces, using household paint and wood stain on handmade panels of wood, foraged from industrial edgelands.

The artworks were a response to spending many days exploring the Lea Valley Park in London.

Over time, certain landmarks and their surroundings took on an almost religious significance…

Electricity pylons became the giants of Albion; the man-made chalk pits became lakes of fire; wires overlapping the sun and moon produced music of the spheres…

Until all of his surroundings in these London edgelands became interwoven with a personal mythology.

Here are the 14 pieces for your viewing pleasure…

Edgeland Vision I

Edgeland Vision II

Edgeland Vision III

Edgeland Vision IV

Edgeland Vision V

Edgeland Vision VI

Edgeland Vision VII

Edgeland Vision VIII

Edgeland Vision IX

Edgeland Vision X

Edgeland Vision XI

Temple I

Temple II

Temple III

ABOUT THE ARTIST

Matt James Healy is a London born painter working in the Neo-Romantic tradition. He currently lives and works in Folkestone. Visit his website here: www.mattjameshealy.com

Or follow him on Instagram @mattjameshealy

September 24, 2020

Under Sheffield: A Subterranean Mystery

WORDS & PICTURES BY: Deeana Violet

This city has a sky like no other.

People keep telling me this when they visit for the first time.

“Big sky”, people say.

They are quite right. It is the sky that I remember most clearly from childhood.

Two visual memories seem to dominate. A plain whitewash sky, a cloud layer so smooth it seems like paper.

And the other, a dirty orange one. The same smooth surface lit up by cheap sodium streetlamps.

Perhaps I am old enough to remember the light of steel furnaces adding to the burnt tone. I’m not sure, but it would fit.

Driving back at night, the orange glare was reassuring, reflecting off the cooling towers and bridges.

Always the clouds though! Why don’t I remember sunny blue skies?

This town is built around rain. Sometimes the rivers come out to claim it back.

I remember the last great flood, seeing the road tear open in front of me from the pressure of water coming up below.

We used to build tunnels here. It’s in our instincts to do so.

Generation on generation went underground.

Mine-shafts and secret escape routes of folklore…

Sometimes that folklore escapes into reality when they turn up an archway in the foundations of a new building.

The tunnels are always there, except they officially aren’t, which is a bit of a laugh because you can see them if you know where to look.

Gargantuan Victorian drainage systems run in chambers underneath the city.

The entrances are there, if you know what fence to look over, which culvert to follow.

The air down there can be foul, above those irritable rivers that can change in an instant and sweep everything away.

There are legends too. Linking cellars and running to the old castle over ridiculous distances.

Everyone seems to know a story, though they are wearily explained as old sewers or bits of mining left over.

But if you ask, people will tell you about the dark chamber with the archway that ran on under the city streets, and the ghost stories attached to it.

You can ask me if you like, I was shown a hidden tunnel entrance deep below the city about twenty five years ago, and I’m sad to say I never explored further (I needed the job that I would have lost by doing so).

We built a huge network of tunnels in the late 60s and early 70s. They linked the shops. You could enter and leave through basements. The only one I’ve seen like it was in Kyoto, part of the station complex there in fact.

But this was very different to the bright and regulated centre over there.

This one was all about hiding from the rain.

That’s where you went, avoiding the traffic and the damp. Concrete running wet and smeared with millions of dark wet footprints.

In the centre, a huge dome open to the sky, to let everyone hurry under back into the tunnels, kiosks built into the walls, bright lights against dark patterns.

Ask anyone of a certain age and listen to them talk about it like a long lost home, even though it smelled a bit and you could get murdered at night.

Humans are strange like that.

When they built it, they cut through old tunnel routes. The people in the travel agents said that something walked through at night sometimes, following the path.

They filled the tunnels in. They blocked them up and if you wanted to stay out of the rain, you had to go to the mall out of town.

Anyone you talk to about this will tell you that nothing was ever the same again.

I hate useless nostalgia and the championing of the past just because it’s the past, but for once, this is true.

People still tell you about things glimpsed underground.

A forum post about looking over a security fence and seeing a thing like an inexplicable underground station, exposed for a few hours by building work…

Mention of impossible rail lines seen running underneath a demolition site….

A mysterious vault deep beneath the library building, itself covered in arcane and masonic symbols…

Rumours of deep shelters and unknown systems…

Strange wires and LED lights in dark alcoves….

We’re still tunnelling, into myth and stories. Loving the sound of the rain while keeping dry.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Deanna Violet lives in Sheffield and it shows. She grew up listening to stories about the city’s secret past and got obsessed with its mysteries. Her dad once showed her how to turn street lights on, and her mum met a ghost on the stairs. You can read this full version of this post plus more of her work on her website, Crow Violets.

August 5, 2020

Traffic Reports from Dark Roundabouts, Deadly Roads & Stone Age Service Stations

Between 2016 and 2017, musician Mark Williamson (AKA: Spaceship Mark) made a series of series of films from British accident black spots and other locations that feature commonly on traffic reports. Through their repetition and persistence in the media, the names of these seemingly unremarkable places have become part of the national consciousness.

Incidentally, two of the locations featured in Mark’s films – The Black Cat Roundabout and The Snake Pass – also appear in the forthcoming Unofficial Britain: Journeys Through Unexpected Places.

With their commonplace urban backdrops, unexpected mythology and history, blended with treated soundscapes of traffic noise, I think these films will be right up the alley of Unofficial Britain’s readers. And for this reason I am delighted to present them here for your titillation.

Traffic Report No.1: Charlie Brown’s Roundabout

Traffic Report No.2: Clacket Lane Services

Traffic Report No.3: The Polish War Memorial

Traffic Report No. 4: The Sun in the Sands

Traffic Report No.5: Snake Pass

Traffic Report No. 6: Black Cat Roundabout

ABOUT THE FILMMAKER

Based in Todmorden, Mark Williamson is a sound collector, film maker, primary school teacher and geologist. You can find Mark on Facebook or Twitter or listen to his many albums here. He has also appeared regularly on this website. Check out these links below:

A sound walk on Walthamstow Marsh

July 15, 2020

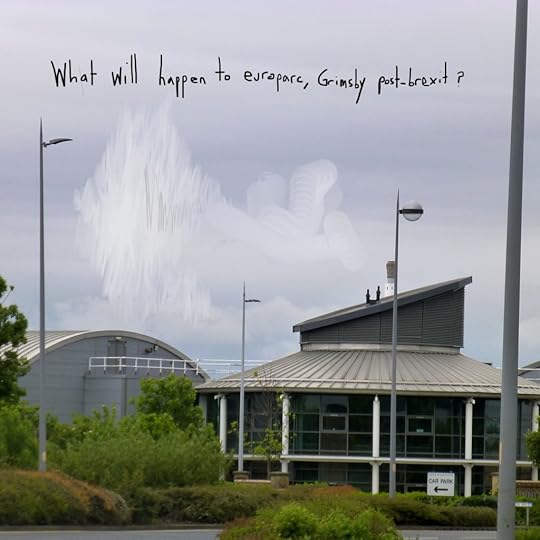

The Business Park in the Marsh: Post-Brexit Wanders in Grimsby’s Europarc

WORDS & PHOTOS: Gareth E Rees

LOCATION: Grimsby, Lincolnshire

My forthcoming book, Unofficial Britain, explores the mythology and lore of industrial estates, electricity pylons, motorways, housing estates, roundabouts, ring roads, flyovers, hospitals & factories. To research the book, I made a series of trips around the country, one of which was to Grimsby in mid-December 2018.

In the aftermath of the Brexit vote, Article 50 had been invoked and the withdrawal agreement had been published the month before my journey. It was in this political atmosphere, on a grey Sunday morning, that I drove northwest from Grimsby to Europarc, a business park situated in a marshland between the A180 and the Humber estuary.

I pulled up outside ‘Beechwood Farm’ a harvester-style restaurant carvery pub on the edge of the business park, surrounded by boggy fields of pylons, striated with drainage ditches, crossed by ramshackle wooden bridges. In the near distance loomed the hulks of factories along the estuary edge, and the imposing Victorian tower rising from Grimsby’s dockland.

Inside the carvery, I met Marc Renshaw, a Lincolnshire-based artist who has grown a strong attachment to Europarc. In 2016 he created an exhibition based on the site, combining short fiction, film, drawings and marketing materials. He has also documented his wanderings through the business park and its environs on a blog.

We sat at a table and I ordered a tea. This turned out to be an empty mug and a finger pointed at a table containing teaspoons, jugs of milk and an urn of hot water. Marc ordered a cappuccino which took an age to arrive. When he asked for its whereabouts, the waitress said she hadn’t forgotten, though it was clear she had. There were a surprising number of people at the tables around us. A few families arrived, presumably using the pub as some kind of service station en-route to somewhere else. Or perhaps Europarc was now a destination in its own right, which is precisely how Marc had been experiencing it for years: a place to wander, think and – as he puts it – to occasionally “wallow in capitalism”.

Marc grew up in the Isle of Man, the British Crown dependency in the Irish Sea. Perhaps this is why he was drawn, he told me, to this island of business activity on the outskirts of Grimsby. As an adult, Marc lived in Cambridge for a while, near the Science Park. When he moved to Grimsby and saw Europarc for the first time, glimpsed in the corner of his eye while driving, he wondered what was going on in the marsh, where the trucks rumbled among stark metallic buildings. The place felt similar to the science park, which he had loved in Cambridge. But also familiar somehow, to his childhood idea of what Britain looked like.

“As a kid, big England appeared as a shadow on the horizon” he said. “On a clear day you could see the towers of Sellafield”.

From the Europarc island, Marc could look out at the industrial skyline, including the Grimsby Dock Tower, Lenzig Fibers factory and Novartis Pharmaceuticals, and feel strangely comforted. I wondered whether being called Marc with a ‘C’ made him feel even more predisposed towards Europarc, also spelled with a C? But I didn’t ask.

For a while after moving to Grimsby Marc worked out here in the marsh in the Kerry foods factory, a fish processing plant. It had now become a Morrisons distribution centre. He told me that it was the very Europeanness of the park that first captured his imagination. Evocative names like ‘Fabricom’ and ‘Achtis’ and global enterprise. Road names like Origin Way, Genesis Way, Pegasus Way and Innovation Way spoke of mythic rebirth and visions of progress. But now the general vibe of the place, said Marc – influenced by Brexit and the forces of isolationism behind that vote – was turning it into something more bland. Perhaps it would not even be called Europarc in the near future.

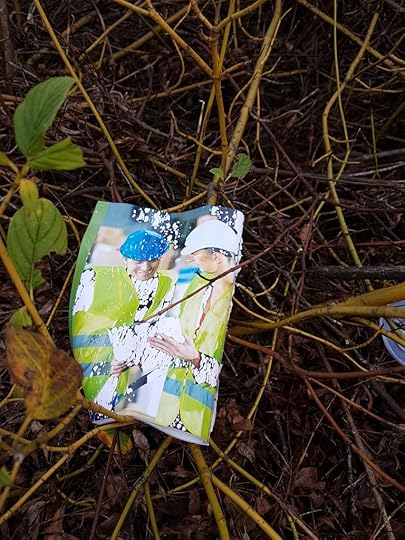

A weekend morning was a strange time to visit the place. The business park felt abandoned. In a layby jutting into a field near the carvery, we found the remnants of a plastic playground slide, and a smashed wooden farm fence, surrounded by energy drink containers. In a verge I spotted a page from a corporate magazine, showing two men in hard hats smiling at a piece of paper, had become distorted by sun and moisture, bleaching them with stark white blobs, as if they were being consumed by some ghostly ectoplasmic entity.

We walked down long straight streets, bordered by hedgerows, interrupted by access roads into vacant car parks for monolithic office buildings and warehouses in greys and beiges, punctuated by the occasional steel chimney. But this rigid formality was tattered by desire paths cutting through verges, endless litter from discarded kebabs and soft drinks, and occasionally signs of violent damage. For instance, the sign for Innovation Way looked like it had been hit sideways by a vehicle. Or perhaps this was simply an innovative sign design.

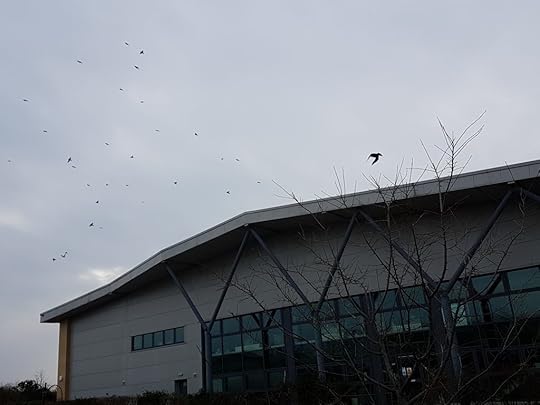

With a retro 1980s school dinner smell in the air, emanating from a readymeal food company, we visited the warehouse of Haiths, a birdseed company that was established in Grimsby town centre in 1937. A family business of local renown. However, for cost and space reasons it had moved out here to the island to become a big warehouse, like any other in the park, bland and anonymous.

However, the company has tried to retain its unique identity by placing multiple bird feeders and birdbaths at the edge of its car park.

All around the Haiths building, crows and starlings darted in and out of the hedgerows, spiralling over the grey roof, filling the small space above it with shrieking life. One of his Marc’s blog posts takes the form of a poem, which describes this spot:

I’m waiting on Genesis Way in my car.

The sun is blinding my eyes as I recall passive stares from the shirtless fishers by the lake.

A gentle sadness…

The obligatory fountain has stopped.

The Haiths bird food hopper is on repeat.

A perpetual hum of productivity…

It was a strange sight, this flurry of wildlife, even more disconcerting amidst the perpetual roar of the A180 feeder road from the motorway, which we could only hear and not see. In the vacant sunday morning business park, that traffic noise was a constant ghostly presence. An intimation of its other life, as a thriving hub of commerce. I keep expecting a car to swing into view or suddenly rush past me, but when I turned to look, there was nothing on the road. The whole place was empty.

It might have been a twist of the circumstances, that abandoned grey weekend morning, but Europarc felt haunted by the spectre of economic disasters yet to come. A year later, the global pandemic would begin and a ‘no deal’ Brexit would be well and truly underway.

An image by Marc Renshaw from his Europarc Project copyright @ Marc Renshaw

An image by Marc Renshaw from his Europarc Project copyright @ Marc RenshawIf you want to find out about the haunting qualities of trading and industrial estates, pylons, factories and modern roads, then order a copy of Unofficial Britain: Journeys Through Unexpected Places today (published September 17th 2020). It’s available on Amazon, Hive and Watersones: https://bit.ly/30yk6sg

For find out more about Marc Renshaw’s work, visit his website here.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Photo by Sara-Louise Bowrey

Photo by Sara-Louise BowreyGareth E. Rees is author of Car Park Life (Influx Press 2019), The Stone Tide (Influx Press, 2018) and Marshland (Influx Press, 2013). His weird fiction and horror has appeared in Best of British Fantasy 2019, An Invite to Eternity, This Dreaming Isle, The Shadow Booth: Vol. 2, Unthology 10 and The Lonely Crowd. His essays about place have appeared in Mount London, An Unreliable Guide to London and The Ashgate Companion to Paranormal Cultures.

May 25, 2020

Bare Knuckles, White Ladies and Martyred Rebels: The Mythic Townscape of Merthyr Tydfil

WORDS & PHOTOS: Gareth E. Rees

In the year leading up the (Not So) Great Pandemic, I was fortunate enough to take a trip around Wales, researching my next book, on a sunny weekend in spring.

It was just me, my car and a smartphone. Plus some underpants. Clean ones, at that. No expense spared. Those were the days when you could buy pants on a whim, simply by walking into a clothes shop.

One of my aims of my trip was to explore the Brymbo steelworks near Wrexham, where my grandfather worked until his death in 1976, and where my uncle worked until the factory closed in 1990.

As I was to discover, the ruins of the Brymbo works are haunted by a bottom-pinching phantom steelworker and two black dogs, which I saw with my very own eyes, but that is a story you can read in the book when it comes out.

While I was in North Wales, I was accompanied to the secret mustard gas factory nestled in the Rhydymwyn Valley by Bobby Seal, who wrote about it for Unofficial Britain in 2015: The Valley Works: Mendelssohn, Mustard Gas and Memory.

On the second day of my mini-tour I drove to South Wales, stopping at Port Talbot to look at its still-functioning steelworks, where a monk is said to haunt the grounds of Tata Steel (more of that in my forthcoming book, too).

As I approached Cardiff, I decided on a detour to Merthyr Tydfil, once the great industrial centre of the British Empire, dominated by four ironworks: Plymouth, Penydarren, Dowlais and Cyfarthfa. By the 1830s, the latter two had become the largest in the world.

As iron made way for steel in the latter half of the 19th century, the Ynysfach Ironwork closed. Its Coke ovens became a hub for the homeless, destitute and society’s outsiders. At the time is was considered a den of boozing, thievery and prostitution, but it may well have great place to hang out and – from the perspective of today – at least they could all be closer than 2 metres apart.

It was here where local bare knuckle fighter Redmond Coleman became locked in an epic battle with his rival, Tommy Lyons. The fight is said to have lasted over three hours, leaving both men flat out on the ground at the end, panting with exhaustion. It would have made the infamously long fist-fight scene in John Carpenter’s They Live seem like a minor playground scuffle. Redmond Coleman was so attached to the place that he later claimed his spirit would never leave Merthyr and instead would remain to haunt the Coke Ovens.

This form of afterlife was to be the fate of Mary Ann Rees. Alas, she had no choice in her decision to haunt Merthyr Tydfil. In 1908 she was murdered by her boyfriend, William Foy, whom she had followed into Merthyr on her final evening alive, suspecting him of sleeping with someone else. Her broken body was found in a disused furnace. Rees is considered to be the White Lady who today haunts the old engine house: a sad lady in a long, flowing dress.

The decline of the coal, iron and steel industries devastated Merthyr but it remained a hub for manufacturing. In the 20th century the Hoover factory employed over 4,000 people, with its own sports teams, social clubs, fire brigade and library.

In 1985, Sir Clive Sinclair’s infamous C5 battery operated vehicle went into production at the factory. A local urban myth was that the motors for the CV were, in fact, repurposed Hoover washing motors. They created only 17,000 units before operation was shut down six months later.

The factory closed in 2009 and remains a quiet hulk by the Taff at the edge of the town. Across the road is a derelict car park, its tarmac crumbling, with moss and grass creeping across the last faded parking bay lines.

A majestic pylon inside the perimeter of the abandoned car park slings electricity over the factory to the other side of the valley, where its brethren have amassed on the hills in great numbers. Whatever has happened in the past century, power still pulses through the town, coursing through the veins of Wales.

The fall of the Hoover factory was another blow to the economically stricken town, which might have lost its role in the world, but keeps its story alive in public artworks that I saw on my journey.

The past is never far away when you walk through Merthyr, a townscape saturated in industrial lore.

… Near St. Tydfil’s Church is an ornate drinking fountain on a raised plinth. It commemorates the pioneers of the South Wales steam coal trade. Its canopy is adorned with steel motifs of coal wheels, steamboats and a miner with a pickaxe.

…On a modern brick wall in the town centre, beneath a ‘To Let’ sign, is an abstract frieze of the industrial landscape.

….A pub that has opened in the restored water

board building is named The Iron Dragon, with two resplendent golden dragons

sculptures jutting from either side of the stone columns that frame the door.

…The Caedraw Roundabout outside the Aldi contains a sculpture by Charles Sansbury, which transforms an earth-bound pit winding gear into a 12 metre tall spire, surrounded by a crescent of standing stones, positing some link in the imagination between the Neolithic and the industrial revolution.

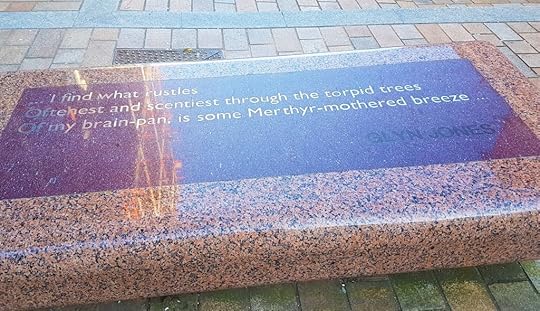

…Pink granite benches are engraved with poems about the industrial past. “the stalks of chimneys bloomed continuous smoke and flame”, says one by Mike Jenkins. Another quotes the scientist Michael Faraday:

“The fires from the hills shone very bright into my room and the blast of the furnace kept up a continual roar.”

On another bench I read lines from ‘Merthyr’ a poem by local lad, Glyn Jones:

“…I find what rustles/ Oftenest and scentiest / through the torpid trees / Of my brain-pan, is some Merthyr-mothered breeze”.

In that same poem, Jones describes the post-industrial town’s decayed slum areas mid-century as “battered wreckage in some ghastly myth”.

On this bench pictured below, was a reference to Dic Penderyn and the 1931 Merthyr uprising.

At that

time, the town was home

to some of the most skilled ironworkers in the world. But unrest was growing….

Locals were increasingly angry about their inadequate wages, while they were lauded over by the industrialists of the town. It was time for change, but they were hopelessly disenfranchised with only 4% of men having the right to vote.

In May 1831, workers marched through the streets, demanding Parliamentary reform, growing rowdier as their ranks swelled. They raided the local debtors’ court, reclaiming confiscated property and destroying the debtors’ records. Growing nervous about the rebellion, which was beginning to spread to other villages and towns, the industrial bosses and landowners called in the army.

On June 3rd,

soldiers confronted protestors outside the Castle Inn and violence broke out.

After the scuffle, Private Donald Black lay wounded, stabbed in the back with a

bayonet by an unseen assailant.

Despite there being no evidence that young Richard Lewis committed the act, he was accused of the crime and sentenced to death by hanging, disregarding the petition of the sceptical townsfolk, and even doubting articles in the local newspaper. The government wanted the death of a rebel as an example to others, and poor Dic Penderyn was to be it, regardless of trifling matters like proof.

He is now an important cult figure in the working class struggle, buried in his hometown of Port Talbot, but remaining here in spirit, one small burning flame of Merthyr’s fiery legacy.

For more information, check out the wonderful Merthyr History Website https://www.merthyr-history.com/

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Gareth E. Rees is author of Car Park Life (Influx Press 2019), The Stone Tide (Influx Press, 2018) and Marshland (Influx Press, 2013). His weird fiction and horror has appeared in Best of British Fantasy 2019, An Invite to Eternity, This Dreaming Isle, The Shadow Booth: Vol. 2, Unthology 10 and The Lonely Crowd. His essays about place have appeared in Mount London, An Unreliable Guide to London and The Ashgate Companion to Paranormal Cultures.

February 28, 2020

As the Crow Flies: Cross City Walks in Birmingham

1. Take a map of a city

2. Draw a straight line from one side of the city to the opposite side, passing through the centre

3. Walk this line

In the winter of 2014/15, Andy Howlett and Pete Ashton undertook four straight-line walks across their home city of Birmingham using the legendary Outer Circle bus route as their boundary.

For the 5th anniversary they’ve put together a short film in an attempt to figure out what it all meant.

Culverted rivers, trauma-scarred industrial estates, motorway-side reveries – experience all this and MORE in this Go-Pro odyssey. Then subscribe to Andy’s new YouTube channel Footnotes for more psychogeographical dispatches from Birmingham and beyond.

If you’d like to know more about walking in the Midlands….

Andy and Pete have just launched Walkspace along with fellow perambulatory practitioner Fiona Cullinan.

A collective of West Midlands based artists, writers and walkers, Walkspace will report on walks that have happened, promote walks that are due to happen and generally discuss the interesting, weird edges of the humble perambulation.

Sign up here for more.

ABOUT THE ARTISTS

Andy Howlett is an artist and filmmaker based in Birmingham, UK. He is interested in walking, concrete, guerrilla heritage and expanded cinema. He runs Magic Cinema nights, is part of the Video Strolls community, and is currently editing his film about Birmingham’s brutalist, recently demolished, Central Library.

Pete Ashton is a multidisciplinary artist creating site-specific work, online and offline. His work often uses media technologies to explore how we perceive and understand the world around us, from camera obscura lens art to algorithmic image manipulation.