Gareth E. Rees's Blog, page 3

April 29, 2021

Elegy for an Industrial Estate flattened to make way for Luxury Apartments

FILM: Martin Fuller

WORDS: Gareth E Rees

MUSIC: Pett Level Sounds (Gareth E. Rees & Matt Frost)

LOCATION: Tower Hamlets, London.

Just off Bromley Hall Road in Poplar is a ramshackle area of salvage businesses and knacker’s yards, piled with mattresses, tyres, corrugated iron, air-conditioning units, reclaimed wood, and rubble sacks. Once a hive of activity, it is now abandoned and desolate,

In 2019, while researching a chapter about industrial estates for my book Unofficial Britain, I took a walk there with filmmaker Martin Fuller and my dog, Hendrix.

We wandered down Ailsa Street and Lochnager Street, between scree slopes of baby buggies, fridge freezers and office chairs. There were skips stacked up along the lane, as if waiting for a larger skip to take them away.

Behind a landslide of junk stood the building of a company that manufactured Indian and Pakistani clothing; a bricked-up window had the words ‘SNACK BAR’ engraved on the stone lintel from the days when this was a bustling place of work.

Now its time was almost up. This whole area was about to be redeveloped into flats.

This is Martin’s film of that walk, combined with footage of how the place looks now, flattened and empty, ready for development. It’s accompanied by a music track I have written with my collaborator, Matt Frost.

Here is our elegy for an industrial estate, and a vanishing way of life.

For more films by Martin Fuller, check out his Vimeo page.

Or follow him on Twitter here.

For more psychrock pscyhogeography from Pett Level Sounds, check this out: The Tragedy of the Hastings U-Boat.

Facebook Twitter LinkedInApril 22, 2021

The Tragedy of the Hastings U-Boat: a Soundtrack

WORDS: Gareth E. Rees

MUSIC: Pett Level Sounds (Gareth E. Rees & Matt Frost)

VIDEO: Kirsty Otos

On 23 February 1919 a German U-boat was surrendered to France. Two months later it was being towed from France to Scapa Flow, where it was to be scrapped. But in a storm, U118 broke loose and began to drift toward the Sussex shoreline. French gunships gave chase, trying to break it up with heavy shelling, but as the submarine approached Hastings, they were forced to turn back.

U118 settled on the beach, drawing crowds. The coastguards assigned two officers to assess the situation below deck. Soon they fell ill. They’d inhaled chlorine released from a reaction between the damaged batteries and seawater, mixed with gasses from rotting food. Five months later, they were dead. What had been the summer’s tourist attraction was now enemy number one. They dismantled it in October.

This is the soundtrack to that event.

Facebook Twitter LinkedInApril 9, 2021

Re-weirding the Urban Landscape

In this online talk for the Reweirding series @ Conway Hall, Gareth E. Rees discusses the future folklore of industrial estates, pylons, motorways, ring roads, hospitals, housing estates, roundabouts, and flyovers.

ABOUT THE SPEAKER

Gareth E. Rees is author of Unofficial Britain (Elliott & Thompson, 2020) Car Park Life (Influx Press 2019), The Stone Tide (Influx Press, 2018) and Marshland (Influx Press, 2013).

Facebook Twitter LinkedInApril 6, 2021

Tales from a Covidian Landscape

ARTWORK: Nigel Dawson

The lockdown restrictions are beginning to lift, but what effect has this had on our sense of place and community? How will empty streets and distanced people feature in our memories of this time? What form of humanity will emerge from the fog?

These images by photographer Nigel Dawson, from a film entitled ‘Tales From a Covidian Landscape’, capture the eeriness of the Covid 19 urban landscape, shuttered and empty, where figures drift like ghosts we can see but not touch.

Nigel says: “They were taken around Islington, Hackney and Hoxton, but the the underlying theme is desolation, change, and our ability to change to cataclysmic events.”

You can see the full set of images on the film below.

bty

btyABOUT THE ARTIST

Nigel Dawson is an artist and photographer based in Northamptonshire. His current work focusses on the urban landscape. Nigel’s previous work has featured on Unofficial Britain – you can view it here: Shadowlands: Light and Darkness on the Urban Edge.

Facebook Twitter LinkedInFebruary 18, 2021

Landscapes of Post-War Infrastructure: A Conversation with Painter, Jen Orpin

WORDS: Gareth E. Rees

LOCATION: A motorway near you

Last month I took part in ‘Landscapes of Post-War Infrastructure’, an online event for the Modernist Society & Manchester school of Architecture.

I talked to the landscape painter, Jen Orpin about our shared interests in the memories and mythology of roads, motorways and service stations. The event was compered by David Cooper.

You can watch a recording of the event below:

And here’s where you can look at more of Jen’s work – Jen Orpin.

There were two other events in this series, in which writers and artists talk about their approaches to overlooked, neglected and underestimated places.

Martyn J Bull talks to Brian Lewis (compèred by Mark Thomas)…

Kevin Crooks talks to Helen Angell (compèred by Luca Csepely-Knorr.)

Facebook Twitter LinkedInFebruary 15, 2021

A Yorkshire ‘Goonies’ Adventure Inside the Secret Tunnel of Holden Park

WORDS & ILLUSTRATION: Patrick Wray

LOCATION: Holden Park, West Yorkshire

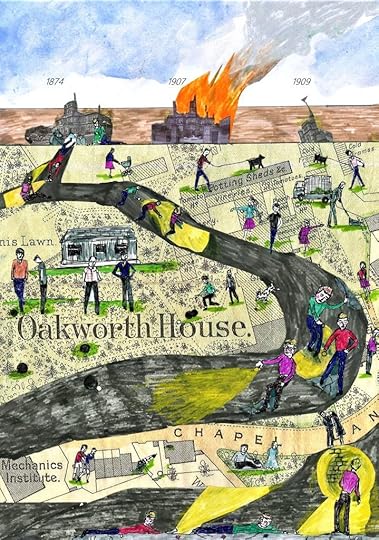

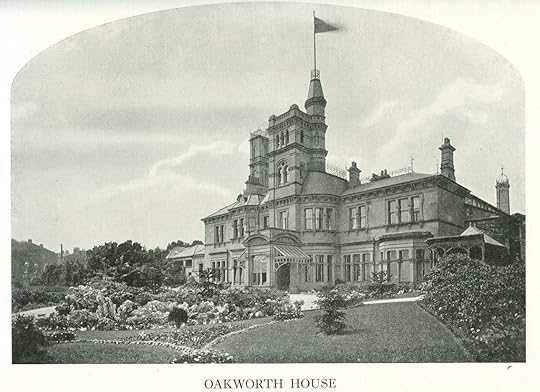

In the picturesque village of Oakworth, West Yorkshire, is Holden Park, often referred to as ‘Oakworth Park’ by locals. It once formed the grounds of Oakworth House, the home of esteemed inventor, manufacturer and radical liberal politician, Sir Isaac Holden.

It was a sunny afternoon in 1991 when I ventured there with two school friends. We had heard a story from someone at school about a tunnel which ran underneath the park. Although seemingly unknown to most people in the area, this tunnel was common knowledge amongst local children and so we went to have a look.

One of the boys I went with must have known its location as I don’t recall us having to search for it. Within one of the cave-like rock formations that decorate Holden Park was a tiny opening in the stones. It was just big enough to crawl through.

I was not a particularly adventurous boy, but something about going down this tunnel appealed to me. I suppose I’d probably read numerous Enid Blyton novels by then and watched the Indiana Jones films enough times to get the message that tunnels are generally worth going in.

One by one, all three of us climbed inside the tight opening in the rock, too small for any adult to fit through. This led to a small alcove like room which was large enough for us to sit up in. From inside this room, another opening below was visible. We had to crawl downward through a short tunnel and underneath a pipe to get through it. This led to the main tunnel which we could just about stand up in when crouching. It was pitch black now, but we didn’t have a torch; just the light from a digital watch. We decided to call off this particular expedition and come back the following weekend more prepared.

All week at school the conversation returned to the mysterious tunnel and what secrets it may hold. Here was our chance to live out a ‘Goonies’ style fantasy on our own doorstep, or that’s how I thought of it anyway.

We travelled from our home town of Keighley the following weekend with a torch each, fully equipped this time for an afternoon’s adventure. Once back in the main part of the tunnel, we walked along it until it came to a dead end. We then turned around to investigate what was in the other direction. We followed its downward slope to another dead end; a wall with rocks and cement piled up against it, and some strange white globs of something or other. We could hear the sound of voices and bowling balls clicking against one other above our heads.

We were now directly beneath the Bowling Green on which Oakworth House had once stood.

Oakworth House was designed by architect George Smith and completed in 1874, a luxurious Italianate style villa built to Isaac Holden’s aesthete specifications, fitted with every modern amenity and luxury. The sprawling grounds contained ornamental lakes, glass houses and various gardens, stone grottos and walkways.

One of its most notable features was an air-conditioning system which required a complex network of ventilation shafts, as well as a huge basement furnace.

When Isaac Holden died in 1897 no buyer could be found for the property and so the house stood derelict for a decade. It was ravaged by fire in 1907 and partially destroyed, before being completely demolished in 1909.”

At the time, we knew little of this past, only that we had stumbled upon one of its subterranean secrets….

A few metres before the end of the main tunnel was an opening in the floor. We climbed down to find ourselves inside a room. This room had a very low ceiling and we had to crawl around on the floor amongst rocks and decades of dust to move around it. Some detritus from previous visitors was scattered around; a few crisp packets and Coke cans. There was not much of this detritus though, just a bit, so perhaps we were, if not the very first to visit; at least among only a small number who had made it here over the years.

We crawled to the other side of the room where it was possible to fully stand up and there was a red brick wall. We hung around chatting for a short time before deciding to make our exit. This didn’t really feel like the kind of place to outstay your welcome.

The whole place looked pretty fragile, like it could cave in at any moment, entombing us for eternity. We obviously didn’t tell our parents where we were going so if it had caved in no-one would have a clue where we were. You can just imagine the news reports about the three boys who disappeared without a trace on a summer’s day. Still down there now, waiting in the dark to be found; reduced to an enduring mystery, occasionally revived by internet sleuths, if we were lucky.

We made our way out and I never went in the Holden Park tunnel again. I heard the entrance was filled in with concrete not long after my visit there; no doubt to prevent any other local youths from exploring it in future. I have not actually visited Holden Park since my subterranean wander there thirty years ago though, so it is vaguely possible that the entrance to the tunnel is still open, but I suspect not.

It was only when I decided to write this article that I put any serious thought into what the tunnel and room actually were. I did a little research, it wasn’t difficult to find out about Oakworth House; I had just never looked. I have found no reference to the tunnel whatsoever, or any mention of anyone else going in it. I only know that it’s existence must have been common knowledge among local kids at the time, because that is how I found out about it. Apart from local children, it is possible then, that it was not generally known about.

It seems possible to me that the underground room that my friends and I found may have been part of the ‘huge basement furnace’ which was the foundation of Oakworth House’s innovative and elaborate ventilation system. It is also possible that the main tunnel we went in was originally one of the ventilation shafts that led to this. We will never know the answer for sure though.

The tunnel and the room are no doubt still there beneath the bowling green in Holden Park. They stand now as one of the last remaining echoes of Oakworth House, hidden from view and deprived of any modern visitors. A sorry subterranean tombstone for a place that was once so full of life and rich with the promise of Isaac Holden’s dreams and vision.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR/ILLUSTRATOR:

Patrick Wray is an artist originally from up North, but now based in London. He published his debut graphic novel The Flood that Did Come via Avery Hill in 2020. You can find out more about his work at www.patrickwray.com

February 12, 2021

Shadowlands: Light and Darkness on the Urban Edge

PHOTOGRAPHY: Nigel Dawson

MUSIC: Chris Ashton

LOCATIONS: London & Sheffield

Unofficial Britain is proud to present a selection of films by artist Nigel Dawson, sound-tracked by Chris Ashton.

In these stark, photographic mutations of the everyday, human ghosts lurk in the shadows of high-rise housing estates, derelict buildings and industrial edgelands.

Dawson explains: “The location of these photographs include Hackney, the Lea valley, and various other areas in London and Sheffield. The images are manipulated in post processing, using a technique I have perfected over many years.

My love of the urban landscape started when I was at school. When I got home, me and my friends would go out into the local countryside and inevitably end up in derelict buildings. I can still smell the damp and a sense of the passage of time in these places. It put my imagination into overdrive.

I do not see my art as concerned with place in a topographic sense. Instead I seek to evoke the dynamic of the environment,…. its spiritual and physical energy…. its fundamental mystery. The haunting soundtracks to these films are as important as the images themselves, and are composed and played by Chris Ashton.”

LONDON: THE DARK CITY

SHADOWLANDS

INVISIBLE SUN

bty

btyABOUT THE ARTIST

Nigel Dawson is an artist and photographer based in Northamptonshire. His current work focusses on the urban landscape.

Facebook Twitter LinkedInDecember 31, 2020

Unofficial Britain’s Weird & Eerie Landscape Reads of 2020

WORDS: Gareth E. Rees

As a father of two young children, with a hyperactive cocker spaniel, a day job, and a second career as an author, I don’t get as much time to read books as I’d like, even in the best of times. During the ‘pandemic year’ I had to complete the final edits of my latest book, Unofficial Britain, while working, home schooling kids and indulging in my anxiety coping mechanisms – which include booze, loud psychedelic music and long walks. Then I capped it all off by getting Covid in December.

So this is absolutely NOT a ‘best of 2020’ list – I haven’t read nearly enough material to do that, even if I wanted to, which I don’t. Who am I to say what’s best? Instead, what follows is a list of some books I read in 2020 that I believe will be of interest to Unofficial Britain readers. They weren’t all published this year, but I really don’t care.

Hauntology: Ghost of Futures Past – Merlin Coverley (Old Castle Books, 2020)

A highly readable, comprehensive account of hauntology, going right back to its 19th Century origins, with 1848 being ground zero, with the publication of The Communist Manifesto. Primarily, this book focusses on the literary incarnations of hauntology, rather than its musical legacy, covering Freud, Dickens, Derrida, JG Ballard, Nigel Kneale and Mark Fisher. Why are we so haunted by our recent past? And what has happened to the future in which we once believed?

The English Heretic Collection: Ritual Histories, Magickal Geography – Andy Sharp (Repeater, 2020)

This is mind-blowing stuff. Andy Sharp draws tremulous lines of synchronistic connection between the British landscape and a host of artists, occultists and historical figures, tracing magickal connections beneath the surface of our reality. While it’s ostensibly a collection of Sharp’s work over the years, the book has a weird, mad coherence. You will feel altered, very slightly after reading this, but you won’t know precisely why.

Settling the World – M John Harrison (Comma Press, 2020)

M John Harrison is my favourite living author, a huge influence behind my own work, and this collection of weird short stories spanning 50 years of his work makes a great primer. Harrison writes brilliantly about the spectral qualities of everyday urban place, where inexplicable forces operate behind the veil of the apparent. God’s motorway rumbles with trucks hauling transported body parts through the industrial Midlands. A mourning train passenger wanders into a spectral Kentish town where time is out of joint. A man’s troubled psych appears to be manifesting a catastrophic physical collapse of the geology around him. This is a journey though an unsettling, unsettled world.

Ghost Town: A Liverpool Shadowplay – Jeff Young (Little Toller, 2020)

An autobiographical portrait of Liverpool in the second half of the 20th Century. What distinguishes this book is Young’s poetic expression of memory – its uncertainty, fluidity and inherent ghostliness. This is the city as a “ruined dream-space”, a “ritual world where the cinema trip and bonfire night have as much mythic and emotional resonance as the hospital visit”. In the act of remembering and retelling, everyday urban life can become mythic and folkloric.

High Static, Dead Lines – Sonic Spectres & the Object Hereafter – Kristen Gallerneaux (Strange Attractor Press, 2018)

This is a book about how technology can be haunted. Sonic spectres manifest through the electronic and mechanical artefacts of the 19th and 20th Centuries, from phone lines and television sets to Moog synthesisers and magnetic tape. Gallernaux’s book itself is a thrilling object to look at, illustrated with haunting collages created by the author.

London Incognita – Gary Budden (Dead Ink, 2020)

If you love intelligent horror writing then this book of weird stories is for you. Troubled outsiders are tormented by demonic forces lurking in the decayed concrete underworlds of the capital city. This is the fever dream of a London built by degenerate architects, its fragmenting edges haunted by the ghosts of its past. You can read more of Gary Budden’s work on this website. Take a look here.

The Memory of Place: A Phenomenology of the Uncanny – Dylan Trigg (Ohio University Press, 2012)

This is an academic book I’ve been dipping in and out of this year, in search of inspiration for my own work. It looks at how place and memory are inextricably intertwined. In part, places are real and objective, unknowable to us in their entirety. But in other ways, places are psychological entities – extensions of our bodies and minds. In both senses, they are spectral and uncanny.

Mudlarking – Lara Maiklem (Bloomsbury Circus, 2019)

The Thames is a repository of memory, the exposed banks of which reveal a shattered unofficial history of Britain and its empire. Mudlarks are those unsung seekers on the fringe of the city, probing the remnants of times past, discovering wonderful treasures, from metal typeface cast into the depths by a disgruntled printer, to witches’ bottles and Mesolithic flints. This is a wonderfully written account of a beautiful obsession.

The Earth Wire – Joel Lane (Influx Press, 2020)

I’d not heard of the late Joel Lane before, so this was a real surprise to me. The Earth Wire is his debut collection of weird fiction, published in 1994 but reissued by Influx Press. The stories are set in the liminal city spaces of ’90s Birmingham and the Black country – car parks, underpasses, derelict factories, railway sidings and canals. The characters are as flung out and marginal as the places they inhabit, dealing with their own crumbling psychic landscapes. Brilliant stuff.

A Land – Jaquetta Hawkes (Collins UK ed. Edition, 2012)

A majestic biography of the geology of the British Isles, where the land itself is an evolving consciousness, published in 1951. I read this book as Covid started to spread through our shores and I was battling on a final edit of my book. I was so bowled over by it, I had to include it in what I was writing.

“Jacquetta Hawkes takes the reader on a journey from the formation of the planet, through the geological upheavals that created what we know as Britain today, to the time in which she was writing, 1949, on the pivot of a rapidly changing century. She describes how Cambrian mud formed the Welsh slates used for roofs; how Jurassic rocks were crucial to the Bath and Portland stone structures of the eighteenth century; and how Carboniferous sandstones defined the buildings of the Victorian era, filled as they were with fossils, ancient plants and antediluvian sediments, and gave urban areas their distinct regional differences.” [From Unofficial Britain: Journeys Through Unexpected Places (Elliott & Thompson, 2020)]

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Gareth E. Rees is author of Unofficial Britain (Elliott & Thompson, 2020) Car Park Life (Influx Press 2019), The Stone Tide (Influx Press, 2018) and Marshland (Influx Press, 2013).

November 25, 2020

White Tents in the Car Park: A Covid 19 Despatch from Kent

WORDS & PHOTOS: Emilia Ong

In Hollywood disaster movies, there’s always some guy who warns of a coming catastrophe.

Nobody listens to him. Not until the shit starts to hit the fan.

That’s the moment when dimwit authorities pull themselves together and begin grudgingly to work with him (it’s usually a him).

But you know that the situation is really serious when you see the white tents, filled with scientists in plastic goggles, masks and suits like crinkly, synthetic babygros.

White tents in a film means that things are bad.

That’s how I feel at the moment, looking out of my window in Margate. Because there are tents in the car park, right beneath my flat. I know I should start quaking but, to be honest, I am just weirded out.

As they say, truth is stranger than fiction.

It’s funny being in a seaside town during lockdown.

Everyone talks about how great it is, about how thankful they are. The whole nation is hankering to be where we are, apparently; to be by the coast, enjoying the sun and the sea air. But now it is winter and there is no more sun. The impassive sea goes in and out, heedless of human problems.

When I arrived it was early June, and the first lockdown was still in force. As I walked down the High Street, litter rolled around my feet, and steel shutters were pulled down over doors, like closed eyelids. I was in Margate to begin a new life, but staring into the grimy windows of Costa Coffee, I understood that there was little life to be had. Everything was on hold, including Beginnings.

As we edged into July however, hope swelled. More people began to emerge, to emerge and to linger; the concrete benches outside Poundland were occupied with scrawny teenagers, the crumpled tops of McDonalds’ bags scrunched in their fists.

The heat wave brought bucket-loads to the beach: one could scarcely make out the sand between the sunburn. Merry-makers jostled for space, drinking lager and breaching guidelines; should it be one metre or two, nobody seemed to know.

The authorities issued statements: You are not welcome here. It made no difference. The town was in its element. The streets were paved with fat golden discs: chips squashed by hundreds of feet into a vinegary mash. Cars filled the car park, shining like beetles in the sun: Margate was getting back on its feet. People looked – vaguely – happy.

But today the car park is filled with tents, and it’s like those few short weeks never happened. The people who came have gone away again, and everything’s being repurposed. The car park is now a dedicated Covid testing site.

Meanwhile, in nearby parts of Kent, another camp has been fashioned out of an army barracks. That camp has been created to serve as makeshift housing for the channel-crossing migrants this country is not gracious enough, or human enough, to properly welcome.

It appears that the disease and the migrants have each been given a ghetto of their own.

If one ever needs a reminder that one isn’t supposed to be going anywhere, let me tell you: a car park filled with tents does the job rather well.

No, we can’t go anywhere, and no one is coming here either. No one is coming to save this tourist town. It is lockdown mark-two, and everyone is at home.

The gift shops are closed, and the pizza place is closed, and the stalls selling ice cream and fried doughnuts are closed, and the fancy seafood bar is closed, and the gallery is closed. And the Italian is closed and the Thai is closed and behind all of the windows of each of the cafés, all of the chairs are upturned. They look like the legs of dead insects which have rolled onto their backs: the world is spiky, forbidding.

In one restaurant window, I see a sign which has been left on: its scarlet LED bulbs flash on and off, sending the word ‘OPEN’ into the darkness like a strobing call of SOS.

Now people only come to the car park – testing site – if they’re in fear of death, or of spreading it. From my window, I watch red-and-white hazard tape snapping in the wind. The tape has been stretched between numerous traffic cones, and scores the once-empty space so that it looks like the long lines at the airport for immigration.

There never seem to be any people around – no one but the staff. That they’re staff is obvious: they are men in high-visibility jackets. The men stand around in small clusters of three or four, their gaits disconsolate, like limp teachers in the school playground chancing a sneaky fag break.

The car park occupies an odd patch of land: car parks usually do. It is bordered by Dreamland – a ‘traditional theme park’ whose Big Wheel I have never seen turn, and whose Scenic Railway is empty of carriages – and by a rubble-strewn back alley which stretches gutter-like behind Wetherspoons.

To another side, there is a rhombus of wasteland. This is strewn with scrap metal and old bottles; diapers languish between scrubby tufts of grass. There are also a couple of abandoned caravans, and several rusting shipping containers arranged in two storeys. A busy road runs along the final edge, home only to a large discount furniture showroom.

Once darkness falls, the tents are floodlit, like a football pitch, and their brilliantine radiance swells haughtily into the Margate nights. The bleaching glow overtakes Dreamland’s bold lettering, which is illuminated in juvenile yellow and underscored in naïve royal blue. The glow competes with the moon which, even when full, looks tired and sallow in comparison.

Each morning I wake and look out, and wonder at the tents’ curious positioning. It is too haphazard, I reflect – they look like heedless toys which come out to play under cover of darkness, toys which have put themselves back in their places too hastily. One has nosed that bit forwards, one has inched that bit back. The tents are not quite in line. They look giddy, slapdash; they are poorly arranged.

For some reason this bothers me.

Of course there’s no getting away from the incongruity of the sight. A testing site ought to be a stringently sanitised place, carefully isolated from the wider world, while car parks are big and dirty and open to all elements.

But perhaps, after all, it is appropriate that the virus is being tested in a car park. When we are travelling somewhere, the act of pulling up in a car park signals that we are there – and yet, not there. Not quite there.

Like a car park, lockdown is an interim, it is not a destination in itself. Or it ought not to be. We hope that it isn’t.

Now that it is winter, the roofs of the tents sparkle with frost. The pandemic is starting to feel like the waiting room of the future. Talk of vaccines is bandied about; so far, it is all just talk.

From my window, I look at the tents. In Hollywood, when the tents arrive, things are bad. But the film’s not done yet. Surely it is not done yet. Will the vaccine come? Will it work?

I look at the tents again; I watch them hold space. And I wait.

This is an edited extract from Emilia’s longer essay, ‘Of White Tents and Unwanted Things’, which you can read here.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Emilia Ong is a British writer, born in Hackney, London, in 1983 to an English father and Chinese-Malaysian mother. An ex-English teacher with a degree in philosophy, she’s working on her first novel. For more information about Emilia’s work, please take a look at her website, www.emiliaong.com Or follow her on Twitter: https://twitter.com/e_o_n_g_

November 20, 2020

From Neolithic Roundabouts & Satanic Car Parks to Council Estate Poltergeists – The Weird Lore of Everyday Urban Places

Gareth E. Rees is author of ‘Unofficial Britain: Journeys Through Unexpected Places‘ (Elliot & Thompson). In this presentation, hosted by October Books on 19th November 2020, Gareth talked about his emotional relationship with a factory chimney…. the phenomenon of council estate poltergeists…. his hunt for cryptobeasts lurking in Scotland’s industrial edgelands… Neolithic roundabouts in retails parks…. satanic messages in haunted multi-storey car parks… ritualistic folk offerings in underpasses… and the mysterious Concrete Henge of the M6.

October Books is a co-operative, radical neighbourhood bookshop and community hub in Southampton. Find out more about the shop here.

You can buy ‘Unofficial Britain’ now from local bookshops or on Amazon, Hive, Waterstones or Bookshop.org https://uk.bookshop.org/books/unoffic…