Max Haiven's Blog, page 13

February 15, 2020

Culture and Financialization: Four Approaches (Handbook of Financialization)

The following essay appears in Philip Mader, Daniel Mertens, and Natasha van der Zwan (eds.) 2019 The Routledge International Handbook of Financialization (London and New York: Routledge)

The following is an uncorrected copy – please cite the published version

Introduction

The difficulty of the task of providing an overview of the relationship between culture and financialization stems not only from the fact that both terms are hotly debated and seek to identify complex phenomena. It also stems from the fact that the spheres one is seeking to describe (culture and finance) are, today, substantially transforming one another. For noted cultural theorist Frederic Jameson (1998a: 60), what we typically identify as post-Bretton Woods financialization coincides with and, indeed, is part and parcel of “the becoming economic of the cultural and the becoming cultural of the economic.” What are we, for instance, to make of a moment when central bank governors, investment bank CEOs and other major financial luminaries must carefully script and stage their public announcements to forestall (or, occasionally, foment) seismic market movements? Or what of the way institutions and practitioners of the arts, now recast as spheres of “cultural production” or the “creative economy,” seem to have embraced many of the logics, priorities, dispositions and practices from the financial world (Haiven 2014b; Vishmidt 2015)? It’s It is not only that culture, today, is big business, hence of interest to financial speculators. Nor is it simply that activities in the financial sector are deeply shaped by “cultural” factors like aesthetics, belief, language games, representation, spectacle and performance (Davis 2018; Knorr-Cetina 2011; MacKenzie 2006; Marazzi 2008; Knorr-Cetina 2011; Davis 2018). It is, more broadly, that in some ways culture and finance name one another’s horizon of disappearance in a neoliberal, globalized world (Jameson 1998b; Martin 2015).

This chapter briefly examines the relationship between culture and financialization from four inter-related angles. First, we explore the finance culture. Here I mean culture in the more anthropological sense of the term and intend to outline some of the recent scholarship on the institutional codes, value systems, representational schemas, quotidian practices and structures of feeling that circulate in and hold together corporations and institutions in the financial sector. Here we will take the example of the institutional culture of Wall Street investment banks.

Second, I want to outline some dimensions of the cultures of financialization, by which I here mean the way the logics, codes, value paradigms, speculative ethos, measurements and metaphors of the financial sector have filtered into other (non-financial) economic and social spheres, offering a set of techniques or dispositifs for the recalibration of institutional priorities towards an alignment with financialization. Here, we will examine the financialization of Anglo-American universities.

Third, I want to dwell on the financialization of cultural production, by which I mean two things: (a) the increased influence of the financial sector on creative industries and creative workers, and (b) the role of film, fiction, art and other creative media in exploring and critiquing financialization. Here, I take up the example of the financialization of the (visual) art world.

Fourth, I turn to the quandaries of cultural production about financialization discussing how producers might adequately represent and respond to financialization, contrasting several recent Hollywood films with John Lanchester’s novel Capital.

Approaching Financialization and Culture

All too often the cultural dimensions of financialization are sidelined in favour of what can appear to be more substantial and material discussions of its economic, political, geographic and sociological aspects. Yet a number of authors have noted the importance of paying close attention to culture in the study of financialization, for a diversity of reasons.

Jameson’s work since the 1980s has been singularly influential in investigating not only the impact of financialization on culture, but the integration of the two. Here, Jameson follows on and develops the bridging of two notions of culture first theorized by members of the Birmingham School credited with pioneering the field of cultural studies: on the one hand, culture as the realm of creative production, on the other culture in the anthropological sense of a complex lifeworld, a society’s remit of beliefs, rituals, social institutions and practices (McRobbie 2005). Jameson theorized postmodernism as the “cultural logic of late capitalism,” the way the rise of speculative capital shaped and was shaped by both notions of culture (Jameson 1991). Hence Jameson encouraged a reading of literature, film, architecture and contemporary art as, on the one hand, symptomatic of deeper political-economic shifts and, on the other, in some ways constitutive of those shifts. Here, Jameson has sought to maintain some deep connection between political economy and culture without falling prey to the trap of economic determinism.

Another important theorist who has sought to bridge this gap is anthropologist Arjun Appadurai, whose work has stressed the “grassroots” development of financial ideas, cultures and structures of feeling, both within the financial realm itself and also in the wider world (Appadurai 2016). For Appadurai, institutional and corporate ecosystems and the realm of daily praxis are spaces where cultures of valuation are produced in dialogue with the overarching economic system. This is as true in the offices of Goldman Sachs as it is in the slums of Mumbai. His work sensitizes us to the way that “the economy” which is being “financialized” is made up of social actors whose actions, relationships, identities and practices are, in sum, “cultural.” But, by the same token, that zones of “culture” are inexorably influenced and shaped by “the economy.”

These themes are addressed quite directly in the pioneering work of Paul du Gay and Michael Pryke, culminating in their edited collection of 2002 Cultural Economy which set forth some key terms for an exploration of (a) how “culture” (both in terms of expressive and creative works and in terms of a fabric of social life) is produced within economic fields of value and power and (b) how the realm that we understand as “the economic” is produced in substantial ways through culture (see also Thrift 2000). Such an approach necessarily puts both concepts under critical scrutiny as in some ways arbitrary or at least flexible markers of two territories which, while conventionally imagined to be very distant to one another, overlap in complex ways (see Best and Paterson 2009, 2010). This work, and that of others, has led to a thriving interdisciplinary field, notably represented in the last decade in the pages of the Journal of Cultural Economy and other periodicals.

In this vein, my definition of financialization as a cultural phenomenon implies more than simply the subordination of a distinct and discrete arena of “culture” to economic pressures. Rather, I am seeking to outline the ethos germane to and in part constitutive of the historical moment and socio-economic processes of financialization. This is an ethos where the techniques, metaphors, dispositions, narratives, ideas, ideologies and relational practices we associate with high finance come to have purchase over a wide diversity of other fields of practice, social life and imaginative expression (Haiven 2014a; McClanahan 2016). This ethos is characterized, in general terms, by the imperative towards speculation, monetary measurement, individualistic competition in which anything and everything of material or immaterial value is transformed into an asset to be leveraged. Importantly, as Randy Martin (2002, 2007, 2015) argues, financialization is distinguished from commodification and monetization by the way it demands a transformation of the imagination towards a mapping of future potentials, the calculative activities of risk management and notions of hedging, leveraging and securitization. Financialization here appears as a habit of the imagination oriented towards reorienting individuals, institutions and society at large towards a kind of conscription of the future itself, with each actor competing to better anticipate and thereby profit from potential trajectories of present-day activities (Haiven 2014aAscher 2016; Ascher 2016Haiven 2014a). The financialization of culture also names the way these tendencies are expressed not only in fields that come under the direct subordination of money, but also in the fields of practice defined by other forms of value, such as cultural capital, social capital or subcultural capital.

Finance Culture

This brings us to our first approach to the question of culture and financialization: the institutional cultures of the production of financial wealth, by which I mean those of the financial sector, including the diversity of “cultures” of investment banks, hedge funds, private equity firms, central banks, public and private financial governance and oversight organizations, bond-rating agencies, accountancy firms and more. This work has been undertaken by a wide range of sociologists and anthropologists focused on a vast diversity of issues (Zaloom 2006; Finel-Honigman 2009; see also Weiss in this volume).

One of the most revealing ethnographies of financial cultures is detailed in Karen Ho’s 2009 book Liquidated (Ho 2009). Identifying herself as a “downsized anthropologist,” Ho worked for years in the back offices of Wall Street investment banks, gaining vital data through participant observation and detailed interviews. A selection of her observations paint a vivid picture of an institutional culture that has such momentous influence on the rest of the world. For one, she confirmed the image of a highly competitive, ruthless and macho world hyperbolized for mass audiences in films like Oliver Stone’s Wall Street or Martin Scorsese’s The Wolf of Wall Street (see also McDowell 1997). She explains how many of the executives and aspiring executives of such firms are gleaned from extremely pricy Ivy League universities, and how it is expected that they will endure gruelling hours and maltreatment as a rite of passage. Indeed, careers in finance are typically short but intense and institutions churn through young talent at an accelerated rate. It is a culture that prizes swiftness, daring and cunning, held in place in part by an occult system of annual bonuses to reward success and punish anything less than excelsior performance.

Importantly, Ho notes that this institutional culture rewards its participants with the idea that they are the best of the best, the most intelligent and competent people in society. This, then, justifies the incredible power the financial sector wields over the economy, over other firms, over society at large: indeed, the investment bankers Ho interviewed generally thought of themselves as serving a beneficial social role by acting as agents of the infallible market, as what I have called “angels of creative destruction” (Haiven 2014b). Ho notes that the effect is the redrafting of the economy and society in finance’s own image.

Ho’s fascinating ethnographic research reveals how, for all its mystique of sanguine calculative reason, the financial sector is held together by the common dramas of culture that animate all societies, communities and social institutions. Indeed, her research and that of others shows us that the cultivation and sustenance of such institutional cultures is vital to the sustainability and competitiveness of financial firms. It also explains how it exists within a broader network of mutually reinforcing institutions, including other firms, educational institutions, parafinancial zones of confluence and sociality (strip clubs, art museums, corporate boards). But even more importantly, her research shows us that the culture of the financial firm has impacts beyond its own corridors: the culture of finance as exhibited in these firms has a massive influence on the culture and the political-economic reality of actors and institutions throughout the capitalist economy that these firms superintend.

Cultures of Financialization

This leads us to our second valence of the intersection of culture and financialization, which names the diverse and deeply disturbing ways the processes of financialization have come to shape and recalibrate institutional governance, social priorities and the general ethos of public and private sector organizations who, at least on the surface, appear to have nothing whatsoever to do with the financial sector. Much work has been done in the field of political economy to seek to understand how, in the post-Bretton Woods moment, the governance of all manner of capitalist firms shifts towards the maximization of “shareholder value,” typically at the expense of long-term economic sustainability, to say nothing of the workers, environments and communities sacrificed on the altar of ever greater quarterly stock performance (see Erturk in this volume). Likewise, there has been a fair amount of attention paid to the disciplinary use of debt, whereby private firms and also whole national governments and public institutions are brought to heel by the power of creditors (Ross 2014; Lazzarato 2015; Ross 2014; Vogl 2017).

But underneath this political-economic phenomenon is a broader cultural shift of which the financialization of Anglo-American post-secondary education is a good bellwether. Here, the introduction or escalation in tuition fees has been accompanied by a state-backed expansion of access to credit, ensuring that the first truly adult experience of many citizens is consigning oneself to post-graduation financial obligations that typically constitute several times the average annual income (McGettigan 2013; Ross 2014). Yet this economic and policy shift are both the cause and the consequence of a cultural transformation where education, once widely imagined as a public good and the responsibility of society at large, is recast as an individualized commodity. Each individual is now responsible for “investing” in their “human capital” by enrolling in post-secondary education or other forms of training (see Brown 2015).

This is a key example of the way financialization encourages, on the one hand, the conditions for intensified privatization, individualization, neoliberal restructuring and free-market solutions while at the same time, on the other, presenting individualized solutions to these transformations. Young people, from one perspective abandoned by their society, are now recast as savvy, empowered “investors.” And as “investors” they come to demand an ever-more financialized model of education: one that promises results when it comes time to try one’s luck on the increasingly uncertain job markets. Financialization in this sense is not experienced as a dystopian imposition from above, but a transformation in the nature of agency and empowerment (see Haiven 2014a).

Meanwhile, within universities themselves, financialization has also led to a recalibration of institutional cultures to better align with the overarching financialized paradigm. For one, the hierarchies and governance of such institutions increasingly comes to mirror the pattern in high finance, with a highly paid executive branch commanding an ever-increasing share of both proceeds and power (Martin 2011). Universities, which often also control considerable endowments are increasingly concerned with managing their own financial investments in profitable ways (Eaton et al. 2016; de Angelis and Harvie 2009). Universities in major urban centrers have begun to recraft themselves as major players in speculative real-estate markets, leveraging their public or not-for profit status and residual credibility as beneficial social institutions (Goddard, Coombes, Kempton, & and Vallance 2014; Valverde & and Briggs 2015). Funding for the professoriate are is increasingly tied to the speculative value of research outcomes, especially to the extent these can be either supported or validated by outside public or private bodies, notably corporations (Newfield 2011; Martin 2011). Out of a desire to open new revenue streams, many prestigious universities have leveraged their academic reputations into global brands, sometimes partnering with private interests to invest in speculative overseas satellite campuses in “emerging economies” (Edu-factory Collective 2009). This is to say nothing of the way predatory firms have manipulated universities (as they have cities and whole nations) into dubious if not outright usurious financial relationships (Russel, Sloan, & and Smith 2016; Eaton et al. 2016).

The example of the financialization of the university is a good illustration of the cultural impacts of financialization for a few reasons. First, universities are allegedly the custodians of culture. While one should not participate in any mythology that imagined that the Anglo-American university was ever free of political or economic influence, the recalibration of this influence towards financialization offers a useful index of profound intertwined cultural and economic trends and tendencies. Second, the Anglo-American university’s residual guild-like structure has been at times replaced by, at times leveraged into a financial logic, which tells us something about how financialization spreads through social institutions not only through directly hegemonic economic impositions, but also culturally, which is to say by a subtle influence over ideas, priorities and patterns. Third and related, the fact that the university remains by and large a public or at least not-for-profit institution means that its financialization can indicate the degree to which that process more generally represents a deep shift on the level of relationships, expectations, notions of value and social hierarchies (Newfield 2011; McGettigan 2013; Newfield 2011).

The Financialization of Cultural Production

The third layer of the relationship of culture and financialization we will explore here is the reciprocal influence of financialization on cultural production, and of cultural production on finance. Cultural production here refers to a wide range of market-mediated expressive or communicative activities including the spheres of film and television, digital media, print and literature, music, the performing arts and, the focus of this section, visual art.

In general terms, studies and critiques of the migration of cultural expression into the capitalist market have a long pedigree, especially in the tradition of thinkers associated with the Frankfurt School and the Birmingham School. More recently, this focus has shifted towards a concern for the condition of cultural and creative workers, especially in light of the pivot of many post-industrial nations and cities towards identifying “culture” and “creativity” as economic catalysts (Banks, Gill, & and Taylor 2013). Meanwhile, of course, cultural production and distribution have become global corporate concerns, with film, music and print production firms consolidating into financialized global empires (Mosco 2010), many of them increasingly tied to high tech and web-oriented firms like Apple, Alphabet (parent company of Google and YouTube), Amazon, Netflix and Spotify (Fuchs 2015).

The rise of these conditions and platforms have has encouraged cultural producers, from novelists to film-makers to musicians to artists, to imagine and advance themselves in a financialized and entrepreneurial register. While the commodification of culture is nothing new, increasingly cultural producers today are recognizing success demands not only technical and artistic excellence (indeed, sometimes this can be a liability) but also a virtuosity in self-promotion, networking and hype (Koz_owski, Kurant, Sowa, Szadkowski, & and Szreder 2015; McRobbie 2015). As early as the turn of the millennia millennium cultural studies scholar Angela McRobbie (2004) wryly identified artists as the “pioneers of the new economy,” the model workers for a post-Fordist capitalism no longer interested in compliant and machine-like industrial workers but, rather, self-activating, imaginative, free-wheeling “entrepreneurs of the self,” to borrow Foucault’s (2008: 226) turn of phrase (see also Rose 1990).

Though they may at first appear marginal, I join others in thinking that the example of art markets have has a great deal to teach us about the relationship of financialization to cultural production (Haiven 2018; Malik and Phillips 2012; Vishmidt 2015; Haiven 2018). Perhaps most notoriously, this relationship is marked by the astronomically high prices achieved at auction by artworks since the 1990s, largely thanks to the competitive bidding power of an ascendant subclass euphemized as “high net worth individuals” (Adam 2017). This has led to a massive boom in the sales and prices of contemporary and post-war artworks, in part because of the influx of new global players eager to obtain unique and esteemed luxury items, in part because many antiquities and works by old masters and impressionists are now in permanent collections (Horowitz 2011). This condition has led critics like Marc C. Taylor (2011) to decry the “financialization of art”: the orientation of many artists, as well as dealers, gallerists, auction houses and other intermediaries, to cater to the whims of the financial elite. This is emblematized for Taylor in the work of artists like Damien Hirst, Takashi Murakami and Jeff Koons, all of whom employ legions of (typically precariously employed) assistants to churn out charismatic, recognizable and extremely expensive “baubles for billionaires.”

Beyond the depraved circus of glitzy auctions and art-world badboys, the broader financialization of art has a great deal to teach us about how something as obstreperous and often explicitly anti-capitalist as contemporary art is folded into the machinations of financialization (Gielen 2010). First, as the hunger for contemporary art has deepened, it has given rise to a panoply of institutions, start-ups and ventures aimed at providing liquidity to what is otherwise a notoriously opaque and cryptic art market. These include art investment funds (which allow investors to pool money to collectively buy artworks for speculative purposes), deluxe “freeport” art storage facilities for the accumulated loot and online platforms that purport to use algorithms to detect and advise on the “next big thing” (the hot art trend whose assets can be bought cheap now and soon sold dear) (Steyerl 2017; Haiven 2018; Steyerl 2017). Art has long been considered an “alternative asset class,” and has also long been a vehicle through which the super-wealthy avoid taxes (Cabra & and Hudson 2013). It has also, as Pierre Bourdieu (1984) and others have shown, long been an essential tool by which the financial elite have navigated their own class reproduction, offering a means towards esteem, cultural capital and the social capital that can come with the connections and relationships art collecting can provide (Velthius 2007). But the financialization of art here demonstrates the degree to which, under financialization, seemingly anything can and does become a speculative asset through a complex set of institutional and, importantly, cultural transformations (Malik and Phillips 2012; Deloitte 2016; Malik & Phillips 2012).

While it may seem that the art market is a provincial example of the financialization of culture it is important to recognize the impacts and reliance of this phenomenon on shifts throughout the whole field of artistic production. As the artist and writer Andrea Fraser (2012) points out, it’s it is not simply that the money of high finance trickles down through the hierarchies of the art world to reach, ultimately, even the most radical and independent institutions. It’s It is also that the logics of financialization come to structure the whole field of cultural production (see also Stakemeier & and Vishmidt 2016). Public museums and galleries are often overseen by boards of directors made up of financiers and collectors, eager to leverage their influence to have the institution invest in the work of artists also in their own portfolios, thereby raising their market prices (Thompson 2010; Thornton 2008). Cuts to public funding for the arts has meant that, increasingly art institutions, art schools and artists themselves cater to the whims of collectors and market intermediaries, whims that are ever fickle and volatile, meaning that throughout the art world there is a fair degree of speculative activity ongoing to produce the “next big thing.” Even those artists and institutions who seek to explicitly reject the pressure and largesse of finance end up speculating on how to avoid its shadow, maneuvers which, ironically, might well be the most successful at producing the “next big thing.” Even when public galleries or museums are not compelled to seek out self-serving donors, there remains often the imperative to maximize a return on a public “investment,” with institutions increasingly orienting themselves to attracting larger and “more engaged” audiences and offering programming that can prove some sort of measurable “impact” on society or culture at large (Bishop 2012).

The structure of the art market, when taken as a whole industry, is an expressive, at times hyperbolic portrait of the future of all labour markets under financialization: a vast pool of unpaid or underpaid workers (would-be artists) investing in themselves and producing work in order that they might compete for recognition and thereby stand a chance of being elevated to the tiny fraction of 1% of such workers who manage to even earn a sustainable living at their vocation (see Adkins et al., this volume).

In this sense the financialization of visual art represents a case study of the ways that financialization saturates and reshapes a sphere of cultural production. But it also offers us a window into the ways various fields of cultural production are enfolded into the circuits of financial accumulation.

Cultural production Production about Financialization

This brief sketch of the financialized art market reveals the contours of financialization in one of the places we presume it least likely to manifest: the allegedly almost autonomous realm of creativity and imagination. Unlike the heavy-handed influence of the wealthy and powerful in times gone by, which demanded that artists create portraits and monumental works to glorify or ornament the ruling class, the influence of financialization on the production of art is more subtle but arguably more insidious. It implies a radical transformation of the economic, institutional and social ecology within which culture is produced while at the same time preserving (if not propagandizing) the sacrosanct creative freedom of the individual artist. In this way, the financialization of art, and of cultural production more broadly, is perhaps the most important and telling example of financialization as a whole: as Martin (2015) explains, today’s moment of financialization arises as a means by which capitalism can reorganize itself to preserve and profit from autonomous, experimental, renegade and self-actualizing actors throughout society (see also Boltanski & Chiapello 2005). Because it is vested in transforming all social actors into vehicles for and innovators of further financialization (often driven precisely by the material pressures of financialization itself), this system is not averse to critique, provocation, resistance and individual rebellion. Indeed, it thrives in part because of these, so long as they are manifested in individualized and financialized ways. We should not see this “cultural” tendency as somehow tangential, contingent or simply symptomatic to financialized capitalism; it is structural (see Langley in this volume).

What, then, of cultural production that would seek to reveal, challenge or critique financialization? Is it all doomed to reincorporation or, worse, inadvertently becoming the prompt for the system’s next stage of evolution?

It can be tempting to mobilize the moral authority, aesthetic charm and communicative flexibility of cultural forms like film, visual art, performance or literature to reveal the “truth” of the otherwise hidden financial world. Recent Hollywood films like The Big Short, Inside Job, The Wolf of Wall Street, Wall Street: Money Never Sleeps, Margin Call and Equity, as well as the TV series Billions have sought to leverage the notoriety of post-2008 Wall Street as a means to, themselves, rake in returns for the movie studios and investors, posing themselves as cautionary tales or pedagogical vehicles (Parvulescu 20182017). One of the long-standing virtues of the financial sector within capitalism is that it presents a villainous face of the system, but also one that is largely resilient to public outrage. The sector can well afford to be represented as the source of economic inequality and corruption because it has little to fear. Workers can strike in factories, riot and loot retailers and blockade ports, but rarely have targeted financiers or their infrastructure, which in any case today are distributed in highly secured offices around the world (Clover 2016). For this reason, too, cultural representations of finance have tended to cause us to imagine arcane, mysterious, shadowy and conspiratorial scenes (see Crosthwaite, Knight & and Marsh 2014).

But beyond simply trying to vivify the machinations of the financial sector (as important as that work is) there is the broader question of how critical cultural producers might represent financialization, which is to say the broader economic, political, sociological and cultural transformation that is the subject of this book. This represents a profound challenge precisely because it is so multidimensional.

One example might come from the realm of literature, in the form of John Lanchester’s 2012 novel Capital, set prior to and during the 2008 financial crisis. While one of the book’s many characters is indeed a City of London financial executive, the focus of the book is a mundane South London street where a whole cast of characters live out loosely interconnected lives. The novel seeks to map out many of the complex and subtle dimensions of financialization through the fates of its characters, in the process revealing that, though they are all grappling with conditions of precarity and “risk-management,” they are still divided by deep(ening) inequalities based on class, gender, age, citizenship status and more. What emerges from the novel, which Lanchester wrote at the same time as he was preparing a highly successful non-fiction account of the financial crisis (Lanchester 2010), is a tableau of subjective shadows cast by the stark and withering light of unleashed finance capital. Financialization itself is only elliptically referred to in the novel’s title, an allusion both to money, to the notion of London as a capital city, and, of course, to Marx’s famous trilogy (though Lanchester’s approach is decidedly not Marxian) (see Shaw 2015).

The absent presence (or present absence) of financialization in Lanchester’s work is, in a sense, symptomatic of the fundamental challenge for representing financialization, which is itself, in part, a system for representing the world in a speculative fashion. As Leigh Claire La Berge (2015) persuasively shows in the case of literature, financialization itself marks a transformation in the structure of capitalist totality such that residual forms and methods for representation are riven, and as such fiction about finance and financialization offer us a vantage from which to think through both the changing nature of capitalism and culture together.

Conclusion

In each of these approaches, financialization is revealed to be a profound shaper of cultural production, whether or not the content of the resultant cultural text explicitly or intentionally references it. On the one hand, such readings of structural and systemic powers into or onto literature and other cultural production is by now an accepted and very fruitful methodology (see Jameson 1981; Eagleton 2000, Jameson 1981). But something more is at stake.

Even as we focus on its cultural dimensions we should never forget that financialization names a material process or part of a suite of material processes that are arguably fundamentally recalibrating the fabric of social life. Martin (2015) suggests that the “order of the derivative” (the financial instrument which he sees as instrumental and paradigmatic) has drastically and irrevocably ushered in a new moment of both fragmentation and interconnectivity as people, populations and economies are transformed by the combined force of money and technology. Alberto Toscano and Jeff Kinkle (2015) echo Frederic Jameson’s (1998b) observation that these shifts in the very nature of social life under late capitalism, though they may appear in the form of post-modern aesthetics and cultural habits, signal a transformed landscape of cognition, one where the ability to “cognitively map” the social totality is sundered.

If this is indeed true, then we may no longer find the term “culture” useful, nor the term “economy” for that matter: if the realms they described ever were truly distinct (which is in fact doubtful), today they are certainly not. Studying the intersection of culture and financialization, then, profoundly challenges us to think anew about both.

Works Cited

Adam, G., 2017. Dark Side of the Boom: The Excesses of the Art Market in the 21st centuryCentury. Farnham, Surrey_; Burlington: , Lund Humphries.

Appadurai, A., 2016. Banking on Words: The Failure of language Language in the age Age of Derivative Finance. Chicago, IL. , London: The University of Chicago Press.

Ascher, I., 2016. Portfolio Society: On the Capitalist Mode of predictionPrediction. New York, NY: Zone Books.

Banks, M., Gill, R. and Taylor, S. (eds.), 2013. Theorizing Cultural Work: Labour, continuity Continuity and change Change in the creative Creative industriesIndustries. London and New York: Routledge.

Berardi, F., 2009. Precarious rhapsodyRhapsody: semiocapitalism Semiocapitalism and the pathologies Pathologies of the postPost-alpha generationGeneration. New York: Autonomedia.

Best, J. and Paterson, M. (eds.), 2010. Cultural Political Economy. London and New York: Routledge.

Bishop, C., 2012. Artificial Hells: Participatory Art and the Politics of Spectatorship. London and New York: Verso.

Boltanski, L., & and Chiapello, E., 2005. The new New spirit Spirit of capitalismCapitalism. London and New York: Verso.

Bourdieu, P., 1984. Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Bourdieu, P., 1993. The Field of Cultural Production: Essays on Art and Literature. New York: Columbia University Press.

Brown, W., 2015. Undoing the Demos: Neoliberalism’s Stealth Revolution. New York: Zone.

Cabra, M. and Hudson, M., 2013, April 23. Mega-rich use tax havens to buy and sell masterpieces. Available at https://www.icij.org/offshore/mega-ri... [Accessed February 27, 2017].

Clover, J., 2016. Riot. Strike. Riot: The New Era Of of Uprisings. London and New York: Verso.

Crosthwaite, P., Knight, P. and Marsh, N. (eds.), 2014. Show me Me the moneyMoney: The image Image of financeFinance, 1700 to the presentPresent. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Davis, A., 2018. Defining speculative value in the age of financialized capitalism. The Sociological Review, 66(1), pp. 3–19.

De Angelis, M. and Harvie, D., 2009. “Cognitive capitalism” and the rat-race: How capital measures immaterial labour in British Universitiesuniversities. Historical Materialism, 17(3), pp. 3–30.

Deloitte. (2016). Art and Finance Report 2016. Luxembourg. Available at https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam...

Du Gay, P. and Pryke, M. (eds.), 2002. Cultural Economy: Cultural Analysis and Commercial Life. London, Thousand Oaks, CA and New Delhi: SAGE.

Du Gay, P., Millo, Y., and Tuck, P., 2012. Making government liquid: Shifts in governance using financialisation as a political device. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 30(6), pp. 1083–1099.

Eagleton, T., 2000. The Idea of Culture. Oxford and Malden MA: Blackwell.

Eaton, C., Habinek, J., Goldstein, A., Dioun, C., Santibáñez Godoy, D. G. and Osley-Thomas, R., 2016. The financialization of US higher education. Socio-Economic Review, 14(3), pp. 507–535.

The Edu-factory Collective, (ed.), 2009. Toward a Global Autonomous University: Cognitive Labor, The the Production of Knowledge, and Exodus from the Education Factory. New York: Autonomedia.

Finel-Honigman, I., 2009. A Cultural History of Finance. London and New York: Routledge.

Foucault, M., 2008. The Birth of Biopolitics. London and New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Fraser, A., 2012. There’s no place like home / L’1% c’est moi. Continent, 2(3), pp. 186–201.

Fuchs, C., 2015. Culture and economy Economy in the age Age of social Social mediaMedia. New York: Routledge.

Gielen, P., 2010. The murmuring Murmuring of the Artistic Multitude: Global Art, Memory and postPost-Fordism. Amsterdam: Valiz.

Goddard, J., Coombes, M., Kempton, L. and Vallance, P., 2014. Universities as anchor institutions in cities in a turbulent funding environment: vulnerable Vulnerable institutions and vulnerable places in England. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 7(2), pp. 307–325.

Haiven, M., 2014a. Cultures of Financialization: Fictitious Capital in Popular Culture and Everyday Life. London and New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Haiven, M., 2014b. The creative and the derivative: Historicizing Creativity creativity under post- Bretton Woods Financializationfinancialization. Radical History Review, 118, pp. 113–138.

Haiven, M., 2015. Art and money: Three aesthetic strategies in an age of financialisation. Finance and Society, 1(1), pp. 38–60.

Haiven, M., 2018. Art after Money, Money after Art: Creative Strategies Against Financialization. London: Pluto.

Harvey, D., 2006. The limits Limits to capitalCapital. 2nd ed. London and New York: Verso.

Harvey, D., 2014. Seventeen Contradictions and the End of Capitalism. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press.

Hilferding, R., 1981. Finance Capital. A Study of the Latest Phase of Capitalist Development. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Ho, K., 2009. Liquidated: An ethnography Ethnography of Wall Street. Durham, NC and London: Duke University Press.

Holmes, B., 2007. The speculative performance: Art’s financial futures. Transversal. Available at http://eipcp.net/transversal/0507/hol...

Horowitz, N., 2011. Art of the Deal: Contemporary Art in a Global Financial Market. Princeton, NJ and London: Princeton University Press.

Jameson, F., 1981. The Political Unconscious. Ithica, NY: Cornell University Press.

Jameson, F., 1991. Postmodernism, or the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism. Durham, NC and London: Duke University Press.

Jameson, F., 1998a. Notes on globalization as a philosophical issue. In F. Jameson & and M. Miyoshi (eds.). .), The Cultures of Globalization. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, pp. 54–77.

Jameson, F., 1998b. The Cultural Turn_: Selected Writings on the postmodernPostmodern, 1983–1998. London_and New York: Verso.

Knorr-Cetina, K., 2011. The market spectacle. Rethinking Capitalism, 2, 1–4.

Koz_owski, M., Kurant, A., Sowa, J., Szadkowski, K. and Szreder, J. (eds.), 2015. A Joy Forever: The Political Economy of Social Creativity. London: Mayfly.

La Berge, L.C., 2015. Scandals and Abstraction: Financial Fiction of the long Long 1980s. New York: Oxford University Press.

Lanchester, J., 2010. I.O.U: Why Everyone Owes Everyone and No One Can Pay. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Lanchester, J., 2012. Capital. New York: Norton.

Lapavitsas, C., 2013. Profiting Without Producing: How Finance Exploits Us All. London and New York: Verso.

Lazzarato, M., 2015. Governing by debtDebt. South Pasadena, CA: Semiotext(e).

Lenin, V.I., 1948. Imperialism, the Highest Stage of capitalismCapitalism; A Popular Outline. Revised translation. London: Lawrence & Wishart.

Levitt, K., 2013. From the Great Transformation to the Great Financialization: On Karl Polanyi and Other Essays. Halifax and Winnipeg: Fernwood.

Luxemburg, R., 2003. The accumulation Accumulation of capitalCapital. London and New York: Routledge.

MacKenzie, D., 2006. An engineEngine, not a cameraCamera_: How Financial Models Shape Markets. Cambridge, Mass.A: MIT Press.

Malik, S. and Phillips, A., 2012. Tainted love: Art’s ethos and capitalization. In M. Lind and O. Velthuis (eds.). .), Contemporary Art and its Commercial Markets. A Report on Current Conditions and Future Scenarios. Berlin: Sternberg, pp. 209–240.

Marazzi, C., 2008. Capital and Language: From the New Economy to the War Economy. New York: Semiotext(e).

Martin, R., 2002. Financialization of Daily Life. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press.

Martin, R., 2007. An Empire of Indifference: American War and the Financial Logic of Risk Management. Durham NC and London: Duke University Press.

Martin, R., 2011. Under New Management Universities, Administrative Labor, and the Professional Turn. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Martin, R., 2015. Knowledge LTD: Towards a Social Logic of the Derivative. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

McClanahan, A., 2016. Dead Pledges: Debt, Crisis, and twentyTwenty-first-century cultureCulture. Stanford, CA and London: Stanford University Press.

McDowell, L., 1997. Capital Culture: Gender at Work in the City. Oxford and Malden MA: Blackwell.

McGettigan, A., 2013. The Great University Gamble: Money, Markets and the Future of Higher Education. London and New York: Pluto.

McRobbie, A., 2004. “Everyone is creative”: artists Artists as pioneers of the new economy? In T. Bennett and E.B. Silva (eds.). .), Contemporary culture Culture and Everyday Life. London: British Sociological Association, pp. 186–202.

McRobbie, A., 2005. The uses Uses of Cultural Studies. London: Sage.

McRobbie, A., 2015. Be Creative: Making a living Living in the New Culture Industries. CamcridgeCambridge, UK_; _ and Malden, MA: Polity Press.

Mosco, V., 2010. The Political Economy Of of Communication. Los Angeles, Calif.A: SAGE Publ.

Neff, G., 2012. Venture Labor: Work and the burden Burden of risk Risk in innovative Innovative industriesIndustries. Cambridge, Mass.A: MIT Press.

Nelson, A., 1999. Marx’s concept Concept of moneyMoney: the The god God of commoditiesCommodities. London and New York: Routledge.

Newfield, C., 2011. Unmaking the Public University: The Forty-Year Assault on the Middle Class. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

O’Neil, C., 2016. Weapons of Math Destruction: How Big Data Increases Inequality and Threatens Democracy. New York: Penguin.

Parvulescu, C. (ed.), 2017. Global Finance On Screen: From Wall Street to Side Street. London and New York: Routledge.

Pasquale, F., 2015. The Black Box Society: The Secret Algorithms that Control Money And and Information. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Passquinelli, M., 2006. Immaterial civil war: prototypes Prototypes of conflict within cognitive capitalism. Available at http://www.rekombinant.org/ImmCivilWa...

Perelman, M., 1987. Marx’s Crisis Theory: Scarcity, Labour And and Finance. New York and London: Praeger.

Pryke, M. and du Gay, P., 2007. Take an Issueissue: Cultural economy and finance. Economy and Society 36(3), pp. 339–354.

Rose, N., 1990. Governing the Soul: The Shaping of the Private Self. London: Routledge.

Ross, A., 2014. Creditocracy. New York: OR Books.

Russel, D., Sloan, C. and Smith, A., 2016. The financialization Financialization of Higher Education: What Swaps Cost our schools Schools and studentsStudents. New York: The Roosevet Institute. Available at http://rooseveltinstitute.org/financi...

Shaw, K., 2015. Crunch litLit. London: Bloomsbury.

Stakemeier, K. and Vishmidt, M., 2016. Reproducing Autonomy: Work, Money, Crisis and Contemporary Art. London: Mute.

Steyerl, H., 2017. Duty Free Art: Art in the Age of Planetary Civil War. London and New York: Verso.

Taylor, M.C., 2011. Financialization of Artart. Capitalism and Society, 6(2), pp. 1–19.

Thompson, D., 2010. The $12 Million Stuffed Shark: The Curious Economics of Contemporary Art. London and New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Thornton, S., 2008. Seven Days in the Art World. New York: WW Norton.

Thrift, N., 2000. Performing cultures in the new economy. Annals of the American Association of Geographers , 90(4), pp. 674–692.

Toscano, A., and Kinkle, J., 2015. Cartographies of the absoluteAbsolute. Winchester: Zero Books.

Valverde, M. and Briggs, J., 2015. The University as Urban Developer: A Research Report. Toronto: Centre for Criminology & Sociolegal Studies, University of Toronto. Available at https://utopenletter.files.wordpress....

Velthuis, O., 2007. Talking Prices: Symbolic Meanings Of of Prices on the market Market for Contemporary Art. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Vercellone, C., 2007. From formal subsumption to general intellect: Elements for a Marxist reading of the thesis of cognitive capitalism. Historical Materialism, 15(1), pp. 13–36.

Vishmidt, M., 2015. Notes on speculation as a mode of production in art and capital. In M. Koz_owski, A. Kurant, J. Sowa, K. Szadkowski and J. Szreder (eds.). .), Joy Forever: The Political Economy of Social Creativity. London: Mayfly, pp. 47–64.

Vogl, JosephJ., 2017. The Ascendancy of Finance. Cambridge and Malden, MA: Polity Press.

Zaloom, C., 2006. Out of the Pits: Traders and technology Technology from Chicago to London. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

The post Culture and Financialization: Four Approaches (Handbook of Financialization) appeared first on Max Haiven.

February 13, 2020

“Culture and Financialization: Four Approaches” (2020)

Haiven, Max. 2020. “Culture and Financialization: Four Approaches.” In The Routledge International Handbook of Financialization, edited by Natasha van der Zwan, Daniel Mertens, and Philip Mader. London and New York: Routledge.

Abstract

This chapter briefly examines the relationship between culture and financialization from four inter-related angles. First, we explore the finance culture. Here I mean culture in the more anthropological sense of the term and intend to outline some of the recent scholarship on the institutional codes, value systems, representational schemas, quotidian practices and structures of feeling that circulate in and hold together corporations and institutions in the financial sector. Here we will take the example of the institutional culture of Wall Street investment banks.

Second, I want to outline some dimensions of the cultures of financialization, by which I here mean the way the logics, codes, value paradigms, speculative ethos, measurements and metaphors of the financial sector have filtered into other (non-financial) economic and social spheres, offering a set of techniques or dispositifs for the recalibration of institutional priorities towards an alignment with financialization. Here, we will examine the financialization of Anglo-American universities.

Third, I want to dwell on the financialization of cultural production, by which I mean two things: (a) the increased influence of the financial sector on creative industries and creative workers, and (b) the role of film, fiction, art and other creative media in exploring and critiquing financialization. Here, I take up the example of the financialization of the (visual) art world.

Fourth, I turn to the quandaries of cultural production about financialization discussing how producers might adequately represent and respond to financialization, contrasting several recent Hollywood films with John Lanchester’s novel Capital.

https://drive.google.com/open?id=1hDY...

The post “Culture and Financialization: Four Approaches” (2020) appeared first on Max Haiven.

February 7, 2020

Is there a radical potential in the epidemic of student anxiety on today’s campuses? (Audio)

Today, the problem of anxiety among students on university campuses has reached epidemic proportion, gaining the attention and concern not only of university administrators and government officials but the general public as well. What is wrong with the kids these days? In this presentation, Dr. Max Haiven, Canada Research Chair in Culture, Media and Social Justice and co-director of the ReImagining Value Action Lab (RiVAL) explores the link between this “epidemic” and financialization: the transformation of society towards an increasingly anxiety-inducing, cut-throat competitive idiom.

Recorded in Thunder Bay (Canada) in October of 2019, Haiven outlines a new research agenda he is pursuing with Dr. Aris Komporozos-Athanasiou (University College London) to explore the hidden radical potential of the anxiety epidemic. Without discounting the terrible toll it is taking on millions of young people or the challenges it poses to universities and their staff, Haiven and Komporozos-Athanasiou propose that it may represent a rejection of financialized society and hold the seeds for a different vision of the future. They see the university as a crucial site of struggle.

Komporozos-Athanasiou and Haiven’s writing on the subject can be found here: https://roarmag.org/essays/from-anxiety-to-revolt-against-the-financialized-university/

In this recording

PART ONE: Introduction: Financialization and the anxiety epidemic (00:00 – 12:30)

PART TWO: Three individualizing explanations for a crisis of individualism (12:30 – 23:40)

PART THREE: Our era of financialization (23:40 – 40:19)

PART FOUR: The anxious university and the university of anxiety (40:19 – 54:03)

EPILOGUE: What comes next? (54:03-59:27)

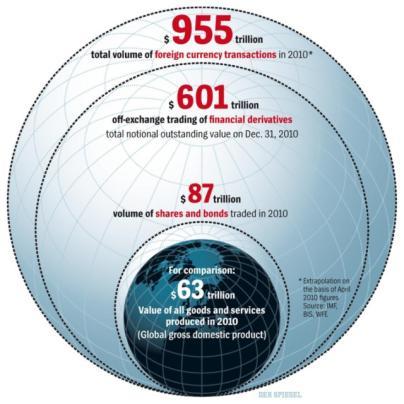

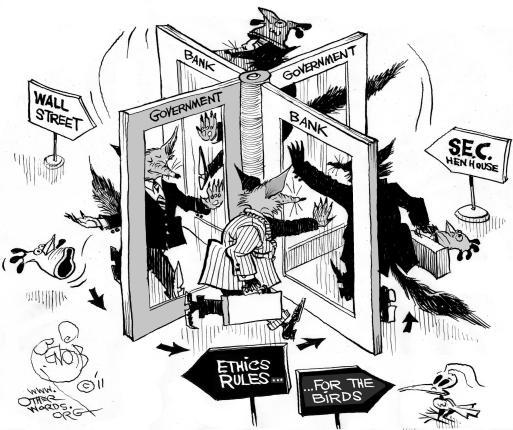

Some of the charts and visuals referred to in the talk:

Animation of 0.2 seconds of high-frequency stock trading: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=B_k_elbBz8c

Comparison between global GDP and financial trades:

Cartoon illustrating the revolving door between finance and government:

Workers mocking McDonald’s “Financial literacy” campaign: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kltKmJhUgLY

The post Is there a radical potential in the epidemic of student anxiety on today’s campuses? (Audio) appeared first on Max Haiven.

January 22, 2020

London, Ramallah, Toronto, Ljubljana (Jan/Feb 2020 newsletter)

December 26, 2019

Revenge Capitalism (May 2020)

Revenge Capitalism

November 11, 2019

Preparing for Millions to Bury their Smartphones

By Krystian Woznicki

An interview with the art collective The University of the Phoenix about responding to the climate crisis with a global secret society for interspecies cooperation.

Original –> https://blogs.mediapart.fr/krystian-woznicki/blog/111119/preparing-millions-bury-their-smartphones

While climate change seems to be intangible, nowhere and everywhere at the same time, it is entangled with everything and everyone. Against this backdrop, the Berliner Gazette’s 20th anniversary initiative MORE WORLD stimulated a critical dialogue. The goal was to better understand and grasp the causes of climate change through entanglements of ecosystems with communal, state and global structures – and ultimately to explore possibilities to tackle climate change from within such interconnections. In the following interview, the Thunder Bay-based art collective The University of the Phoenix (UotP) reflects on the challenges for planetary cooperation in the face of climate crisis.

Krystian Woznicki: Your work extensively deals with dispossession in the context of global capitalism. How do your work in general related to climate change?

The University of the Phoenix: In general terms, The University of the Phoenix is a kind of parafictional educational institution that invites the living and the dead to work together to avenge the crimes and cruelties of global capitalism. We often work in social situations, such as conferences, where, in spite of the fact that most people would like to abolish capitalism, we end up reproducing it against our wills because of the way capitalism ends up conscripting our creativity, autonomy, relationships and hopes.

By inviting in dead people, who no longer pay rent, accumulate social capital or compete for work, who no longer care about success or prestige in any worldly way, we try to influence the not-yet-dead (living people) to rethink their attachment to the time and value of their lifetime. There are no work deadlines without a body, a community or without a planet. We think of life as a kind of training or practice for becoming dead, and so the dead have a lot to teach the not-yet-dead.

Especially for those of us who are compelled by this moment of so-called cognitive capitalism to measure our self-worth in terms of our ability to propose, fund, complete and report on projects, working with the dead is a reminder that any project worth doing actually began generations before our bodies were even born, and will continue after we join the ranks of the dead. The dead remind us to take a longer view that extends outside the individual lifetime and encompasses past and future generations. This shift in imagination from what is ‘mine’, what is possible in ‘my’ life, and what makes a ‘good life’ means that maybe we can assess and participate in our lifetimes differently.

Working with the dead can help the not-yet-dead disconnect from the networks of capitalist neurohacking and, instead, connect to much bigger projects, much longer desires, such as the desire to ensure the earth can sustain less violent forms of human thriving, the desire to find the means to work together to actually confront climate change. In a sense, we are working with the dead to dispossess the not-yet-dead of our pathological attachment to individual success and to so many dangerous phobias and false hopes that keep us all enrolled in or captivated by a system of global dispossession.

KW: For the Berliner Gazette’s MORE WORLD event you developed the performance piece The Order of the Immortal Stranger, for the first time in your history explicitly addressing the climate crisis. Could you explain some of the general assumptions underlying this piece, especially with regard to emancipatory politics in the face of the climate crisis?

UotP: In the past, we have typically used techniques including seances, rituals and walking tours to welcome the dead to work with the living. This time the dead wanted to tell us a story.

Our performance revolved around a fable from a potential tomorrow, told by a sort of collective hypothetical daughter who might be born nine months after the More World Conference. We know that her name is Adrestia, and that she might record herself in approximately 2036, when she would be 16 years old. Her parents might by this time have already disappeared into the growing social upheavals of the climate crisis, and she lives in some sort of collective. Essentially, in this future, she and other children come to recognize adults as the source of the world’s problems and create a kind of “order” or secret society that uses biohacking to ensure that everyone over the age of about 16 dies.

In this future, adults are all addicted to a genetically modified form of coffee that allows them to withstand a kind of social disease called The Wasting, which has symptoms like depression, inertia, nostalgia and narcissism and, if left untreated, leads quickly to death. As the story progresses, Adrestia and the other children team up with a very special anti-colonial plant, The Immortal Stranger, to ruin coffee and allow the adults to succumb to The Wasting. Adriesta might make this recording as she herself is becoming an adult and dying of The Wasting.

The children form The Order of the Immortal Stranger to accomplish their mission of abolishing adults and adulthood, based on lessons they might learn from the tree. Capitalism today is based on the frantic extraction and depletion of the earth’s “resources,” as well as our bodies and souls, all in the name of a completely unsustainable and, in fact, sick form of “life” and “growth,” a kind of obsessive vitalism based on consumption of anything and everything. In contrast, the Immortal Stranger teaches the children that it is more important to create good soil for future things to grow. What if, instead of being obsessed with life we spent our lives learning how to die, so that we might literally and metaphorically become the soil in which future generations might thrive? What if we considered the earth so important that we were willing to die to keep it alive?

As she dies and looks forward to becoming soil, Adrestia might record her story to be part of a self-learning module for the children who will come after her, but will not have teachers because there are no more adults, and there never will be. Her story is paused at several moments so that an AI she might design can demand that the listener/learner follow instructions and perform some embodied and somatic yogic techniques to better understand and internalize several key lessons from the Immortal Stranger. One of the key pedagogical methods of The University of the Phoenix is planting important ideas in the body using these kind of techniques, because, in our age of capitalist neurohacking (through, among other things, our smartphones) it is important to remember our always-dying bodies, our corpses. The audience/participants for these activities were, at the same time, the future children but also today’s adults who had gathered at the conference. In fact, it is in a way the ghosts of these future children whom we invited to join us.

KW: Your work is designed as an intervention that thoroughly confounds distinctions between fiction and reality. This said, an underlying idea of your piece – involving performers Hannah Levin and Florence Freitag – is that the Immortal Stranger was named as “president” of The University of the Phoenix. What is this ‘narrative figure’ actually about? What is its ‘profile’? And what sources of inspiration does it have?

UotP: The Immortal Stranger is a plant: a tropical tree, also known as Tulipan Africano. It is considered one of the world’s most invasive weeds. It is widely hated because, while beautiful, it is considered useless. It originated in West Africa, where to this day it has many uses, medicinal and utilitarian. We have found two myths about the way it spread worldwide. One story is that it was taken by imperialists who wanted to include it in their controlled, tropical gardens. But when it arrived it took over, destroying the garden. The other story we have heard is that enslaved people and migrants from West Africa brought the tiny, heart-shaped seeds with them, perhaps knowing of the plant’s uses, perhaps knowing of its powers of revenge.

We discovered the Immortal Stranger, or maybe it discovered us, when we were in Puerto Rico in the summer of 2017 on a research trip to talk to local artists and activists about the debt crisis. This was a few months before the hurricane that devastated the island. Then as today Puerto Rico remains essentially a colony of the US and the aftermath of the hurricane proved this when the population was abandoned by the US, and speculators and profiteers moved in. In any case, when we were there we wanted to find a representative of the resilient spirit of the land and a young radical coffee farmer suggested the Immortal Stranger. As she showed us, the plant is everywhere, with huge, trumpet-like red flowers. When we first met, it was a small weed that was growing up in between the concrete on a highway overpass.

It turns out that the Immortal Stranger had long been the enemy of the kind of cash-crop mono-culture agriculture that were the basis of the colonial extractive economy of PR because it thrives in damaged and abused landscapes, like large-scale plantations. After the US transitioned the PR economy away from agricultural production and towards low-cost, hyper-exploitative manufacturing in the 1950s, the Immortal Stranger took over a lot of the now-abandoned plantations and was responsible for one of the greatest reforestations in recorded global history: it grows quickly, provides a canopy, and repairs the soil so other plants can return.

We were so inspired we named the Immortal Stranger the “president” of our university and have been asking our agents in tropical zones to harvest and send us its seeds. We use these seeds in almost all our activities. We have, for instance, planted them at the HQ of a “vulture fund” that is deeply invested in the financial colonization of PR and other economic crimes. We also often “plant” the seed in people’s phones, reasoning that, not only can the spirit of the Immortal Stranger help protect us from the ways digital capitalism infiltrates and makes a plantation out of our mind-bodies, eventually these phones will end up back in a tropical zone as e-waste, where the Immortal Stranger might once again take its strange, slow vengeance.

KW: How does the global secret society for interspecies cooperation emerge from this?

UotP: In Adriesta’s potential future, The Order of the Immortal Stranger might form to abolish adulthood and radically transform the world through interspecies cooperation with the Immortal Stranger. In the performance/ritual, the Order transports itself back, through time and space, to claim or recruit the audience at the BG conference. Perhaps, in the future those children might create, they have some technology that makes them capable of such quantum terrorism. We hope so. In any case, we at The University of the Phoenix believe that learning from the Immortal Stranger is crucially important for our struggles today.

KW: In order to instigate the global secret society for interspecies cooperation, you collected smartphones from the audience at the MORE WORLD event and then buried them. At this point, Sherry Turkle’s book “Alone Together” (2011) may come to mind where she argues that technological developments that have most contributed to the rise of interconnectivity have bolstered a feeling of alienation between people. Is this what you had in mind?

UotP: Detaching people from their phones has become a very important part of all The University of the Phoenix procedures with the not-yet-dead. For the University, the smartphone is both a literal material manifestation and ambassador, and also a potent symbol of our moment of global capitalism. It is, of course, one of the chief artifacts and commodities of that system, assembled from a world-wide collection of resources and forms of labour. It is also the chief mechanism, today, whereby we are each inscribed within that now-digitized capitalist system, in terms of the way the smart-phone ecosystem conscripts us to a whole variety of capitalist behaviours. At the same time, partly because of all this, the smartphone is a kind of fetish that we all obsess over, so from an artistic angle taking away people’s phones and doing something strange with them is very effective, and places the audience in a very different kind of headspace.

We often speak of “disconnecting the nervous system from the global economy” so that we can make new, better connections, relationships, for instance to the world of the dead. We have been thinking a lot not only about the kind of alienation you mention, which is an alienation from other living humans, but also an alienation from death. Digital capitalism is relentlessly vitalist: it promises life, life, life. Now the same pirates who have comandeered our minds through these devices seek to escape death, too, with all sorts of stupid ideas about uploading our consciousnesses and so on. Of course, this will only be for the super-wealthy, but there is a way this pathological vitalism “trickles down” to us plebs as well, especially through the rhetorics of self-care and therapy, in their commercialized form. We at The University of the Phoenix want to ask, how can we move away from the cruel optimism that surrounds the notion of “healing” in a fundamentally toxic world. Instead, how can we better learn how to die?

There are other networks that connect us, more generative, powerful and important networks. The network that connects us to the dead, for instance. Or the networks that connect us to other living things. Why do we so obsess over using toxic, blood-soaked, disposable machines to allow us to incessantly access networks designed to hack into our social and neurochemical systems the better to exploit us?

KW: How will the global secret society for interspecies cooperation enable us to tackle the climate crisis?

UotP: Most of the pedagogy of The University of the Phoenix is to work with the dead to train them to help the not-yet-dead avenge the crimes and cruelties of global capitalism, including capitalism’s climate crisis. Those who attend, or in fact even read about our so-called performance, if they are sympathetic to these objectives, become haunted by ghosts who will help them achieve this end. This is The Order of the Immortal Stranger, a global secret society that is so secret even many of its own living members do not know they are members. You may have become a member simply by reading these words. For this, there is no end-user licence agreement, we are sorry to say, but you wouldn’t read it anyway, and the EU doesn’t even know how to regulate it.

Not-yet-dead Members of the Order are charged to enter the multiverse of climate change activism with a perspective renewed and emboldened by the connection to death and to the trust in the natural anti-colonial qualities of plants, like the Immortal Stranger.

These are the lessons we put through the social body who attended the performance, using story, sound, movement and force:

We thrive uninvited where we were never meant to grow.

Their waste is our teacher.

We use our life time to transform their ruins, into our home

Let us learn to die to become one another’s soil.

These mantras help members of the Order take the long view that stems from a recognition of our interdependence with multiple generations, past and future. These mantras, developed by our hypothetical children, for their children, can help we adults today to remember that we cannot act as if we are the first or the final generation.The best proof of our work will be if there is good soil for future generations— and we mean soil as the stuff made of decomposed bodies, both literal and metaphorical. The University of the Phoenix is part of a long pedagogical tradition of teaching the not-yet-dead how to die. If we learned to die to become one another’s soil in these ways, how might it change how we work, cooperate and spend our time?

About The University of the Phoenix

The University of the Phoenix (UotP), a collaboration between artist Cassie Thornton and scholar-activist Max Haiven, is a free-school and research institute for the dead that is also sometimes open to not-yet-dead auditors. Working at the intersection of research, art and activism UotP instigates locally-informed collaborations for radical financial literacy. In an age when technologically-accelerated financialization and debt overshadows social and political life UotP offers revenge consultancy services to those wronged by global capitalism. UotP instigates conversations, produces and distributes disruptive media, and plots uninvited appearances of the otherwise invisibilized. More info on this website: http://universityofthephoenix.com

The post Preparing for Millions to Bury their Smartphones appeared first on Max Haiven.

October 29, 2019

Fall 2019 newsletter

Revenge Capitalism is coming in the Spring, and Europe

July 18, 2019

Epic interview on art and money, plus (summer updates)