Max Haiven's Blog, page 11

May 20, 2020

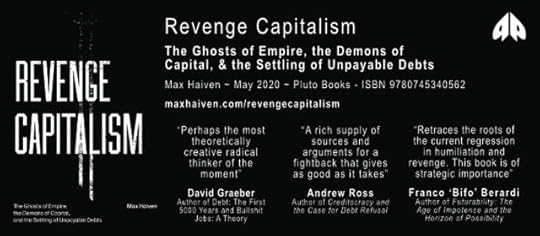

Revenge Capitalism is out now!

I’m thrilled to announce that, at long last, my book Revenge Capitalism: The Ghosts of Empire, the Demons of Capital, and the Settling of Unpayable Debts has been published by Pluto Books and is available for sale online now and in stores… whenever they reopen! You can find out more at:

maxhaiven.com/revengecapitalism

https://www.plutobooks.com/9780745340562/revenge-capitalism/

*** Special: 30% off ***

Enter ‘REVENGE30’ at the checkout over at Pluto Books’ website under “add coupon”

https://maxhaiven.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/RevengeCapitalismTrailer.mp4

A personal request to help spread the word.

The first two weeks of a new book’s life are crucial, and the fact that we’re all stuck indoors makes this especially difficult. While ‘m personally disappointed not to be able to do in-person public events to promote the book (for online ones, see below), the impact of the pandemic on radical publishers like Pluto is dire. Please consider buying extra copies of my book to give to friends (or, better, enemies – they’re guaranteed to hate it) and also contributing to Pluto’s Patreon.

Meanwhile, I hope you might consider doing any of the following to help get the word out about the book:

Please take a moment to share the book on social media

Consider recommending it to a magazine, website or podcast you love for review

Do you know someone who might be interested in writing a book review? (If so, they can email Chris at chrisb@plutobooks.com to obtain a free review copy)

Forward this email or information on to people you know or email lists.

Overview

OverviewCapitalism is in a profound state of crisis. Beyond the mere dispassionate cruelty of ‘ordinary’ structural violence, it appears today as a global system bent on reckless economic revenge; its expression found in mass incarceration, climate chaos, unpayable debt, pharmaceutical violence and the relentless degradation of common life.

In Revenge Capitalism, Max Haiven argues that this economic vengeance helps us explain the culture and politics of revenge we see in society more broadly. Moving from the history of colonialism and its continuing effects today, he examines the opioid crisis in the US, the growth of ‘surplussed populations’ worldwide and unpacks the central paradigm of unpayable debts – both as reparations owed, and as a methodology of oppression.

Revenge Capitalism offers no easy answers, but is a powerful call to the radical imagination.

Endorsements

Perhaps the most theoretically creative radical thinker of the moment.

David Graeber, author of ‘Debt: The First 5000 Years’

Max Haiven retraces the roots of the current regression, of the reactionary trend that is driving the world toward a new darkness. These roots are humiliation and revenge. In my opinion, this book is of strategic importance.

Franco ‘Bifo’ Berardi, author of ‘Futurability: The Age of Impotence and the Horizon of Possibility’

A deeply learned debt warrior, Haiven lays bare the abject cruelty of financial capitalism, and provides us with a rich supply of sources and arguments for a fightback that gives as good as it takes.

Andrew Ross, author of ‘Creditocracy and the Case for Debt Refusal’

Bio

Max Haiven is Canada Research Chair in Culture, Media and Social Justice at Lakehead University and co-director of the ReImagining Value Action Lab (RiVAL). His previous books include Art After Money, Money After Art: Creative Strategies Against Financialization (2018), Cultures of Financialization: Fictitious Capital in Popular Culture and Everyday Life(2014) and (with Alex Khasnabish) The Radical Imagination: Social Movement Research in the Age of Austerity (2014).

Table of Contents

Introduction: We Want Revenge

Ch1. Toward a materialist theory of revenge

Interlude: Shylock’s vindication, or Venice’s bonds?

Ch2. The work of art in an age of unpayable debts: Social reproduction, geopolitics, and settler colonial

Interlude: Ahab’s coin, or Moby Dick’s currencies?

Ch3. Money as a medium of vengeance: Colonial accumulation and proletarian practices

Interlude: Khloé Kardashian’s revenge body, or the Zapatisa nobody?

Ch4. Our opium Wars: Pain, race, and the ghosts of empire

Interlude: V’s vendetta, or Joker’s retribution?

Ch5. The dead zone: Financialized nihilism, toxic wealth, and vindictive technologies

Conclusion: Revenge fantasy or avenging imaginary?

Coda: 11 Theses on revenge capitalism

Postscript: After the pandemic: Against the vindictive normal

Things to read

Short

“ No return to normal : For a post-pandemic liberation” (post-script) in ROAR.

Tambien en español (with thanks to Mario Morales).

Aussi en français (with thanks to Éloi Halloran).

An audio version

Medium

“ Capital’s Vengeful Utopia : Unpayable Debts from Above and Below” in L’Internationale

“Introduction: We Want Revenge” to Revenge Capitalism

Longer

“Capitalism as Revenge :: Revenge Against Capitalism– An Interview with Max Haiven” in Socialism and Democracy.

Also available as an audio interview.

Things to watch/listen

Short

Book trailer, a one-minute teaser.

Overview: a five minute video about Revenge Capitalism.

Medium

A revenge tour of London, a 22-minute video exploring the book’s main chapters

Long

“Money as a Medium of Vengeance: Colonial Accumulation and Proletarian Practices,” A 44-minute illustrated video version of one of the book’s chapters.

“Our opium Wars: Pain, race, and the ghosts of empire,” 55-minute audio interview about one the book’s chapters.

Longest

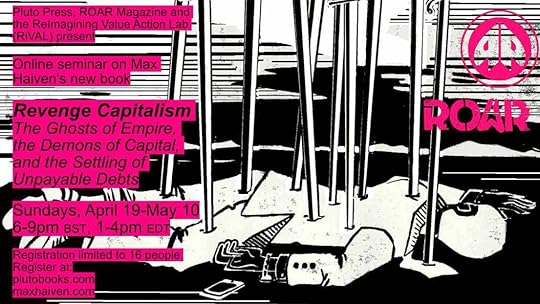

Four video lectures (45-minutes each) on the book’s chapters and themes, recorded as part of a seminar in April and May

Online events

May 7 – “‘Revenge is a human dream.’ On the poetics and politics of avenging” a conversation with Max Haiven and Phanuel Antwi.

Archived in video and in audio.

May 20 – “Is ours an age of revenge capitalism?” University College London Institute for Advanced Study Talking Points Seminar. 6pm BST. Online and open to all.

May 27 – “Art, debt, capitalism and revenge.” Slade School of the Arts public lecture. 5pm BST. 6pm BST. Online and open to all. Link coming soon.

More events coming soon

Art by Amanda Priebe

The post Revenge Capitalism is out now! appeared first on Max Haiven.

May 15, 2020

“Capital’s Vengeful Utopia: Unpayable Debts from Above and Below” in L’Internationale

L’Internationale, the joint online and print publishing initiative of seven major European art institutions, has published a new essay “Capital’s Vengeful Utopia: Unpayable Debts from Above and Below” which addresses themes in my new book Revenge Capitalism: The Ghosts of Empire, the Demons of Capital, and the Settling of Unpayable Debts, due out next week (May 20) from Pluto Press.

Read it online here, or as part of the PDF or epub of the publication as a whole, on the fascinating topic of “Austerity and Utopia.”

Capital’s Vengeful Utopia: Unpayable Debts from Above and Below

Max Haiven

Originally published in May 2020 in L’Internationale, special ebook on Austerity and Utopia

1.

Much can be gained from considering the current order of financialised, neoliberal, racial capitalism as a kind of utopia for capital. This is an inhuman utopianism, one where the world is reconfigured towards the horizon where capital enjoys immanent access to all aspects of human potential: the commodification, monetisation and financialisation of every process of life. The transformative imperative of neoliberalism and the structures of financialisation have the effect of encouraging, disciplining and enticing every social actor into using the logics, measurements and frameworks of capitalist markets, which will, in effect, recode, reorient and recast nearly every sphere of social activity to better resonate with and contribute to the increasingly digital network of capitalist circulation1. We are, of course, resisting and refusing this necro-utopian drive in a variety of ways. But recognising this utopian drive within the system itself helps us better frame its catastrophic trajectory and its demonstrative moments of vengeful excess.

I have previously meditated on the luxury free port (where the world’s super-rich stash their art treasures) as an example of a utopian space of capital2. Certainly these institutions market their services to the elite of the global capitalist class, those who are eager for such exclusive, bespoke hyperspaces, which cater to their whims and their vanity. But while such spaces may have a utopian flavour for their clients, they are more important to understand as the materialisation of capital’s utopia. The free port transfigures ‘art’ (that bourgeois cipher for human creative freedom) into a pure speculative commodity: art and artefacts encrypted within the free port’s vaults may not move in decades or even centuries, but the rights to their ownership are traded, hedged on, used as collateral, leveraged and securitised innumerable times. These artworks exist to all intents and purposes in a parallel universe where capital moves without inhibition or latency. Or perhaps it is more accurate to say, a universe in which latencies, borders, inhibitions, regulatory regimes and laws simply represent a variegated and mouldable terrain.

2.

It is by now well known that the intellectual architects of the neoliberal revolution were, at least in principle, motivated by a fear of utopianism. For economist Friedrich von Hayek and his acolytes and collaborators of the Mont Pelerin Society, capitalism was the only system that might allow human society to transcend the tyranny of particularistic moral value paradigms declared universal and imposed on society by force3. Even when guided by the loftiest principles and the wisest rulers, any political ideology poses a totalitarian threat on the economy and society. This threat stems largely from the fact that society is too vast, too complex and too contradictory to be encompassed by any intellectual or moral framework. As the late theorist of financialisation Randy Martin illustrates, for Hayek and company it was ultimately a problem of knowledge and its limits: no one human mind could possibly know and therefore plan or manage the whole of social intercourse, and so would necessarily come to impose their utopian and authoritarian vision on the whole4. Only a free market system – held in place by a minimum of laws to prevent fraud, theft and violence, and, as Melinda Cooper has recently shown, by the values of the patriarchal family5 – could transcend this contradiction. The unfettered market is (theoretically, at least) a pure reflection of the actuality of plurality and the diverse demands of social subjects, which it accommodates relatively fairly, sustainably and without coercion.

Four decades into the neoliberal revolution and we now know all too well that such an agenda leads to an almost universal dystopia. The theoretical suprahuman and the post-utopian neutrality of markets in practice create vast, coercive forms of inequality and financial authoritarianism – today on the scale of the planet itself. The age when nation states were susceptible to totalitarian leaders who sought to pivot the entire society and economy towards some utopian scheme is well gone. Current authoritarian leaders claim only to offer protection and competitiveness to their chosen (ethnic, religious, national) people against the ravages of the global capitalist market; a dire situation to which they and their policies also contribute. Authoritarianism today does not force society into a formation to fulfil perverse dreams of utopian potential. Rather, it offers austerity, purification and revanchism as means of survival in an ever more hostile world.

3.

I propose that it is fruitful and more so revealing to consider our moment of financialised, global, racial capitalism as so shot through with contradictions that it appears to be taking a needless, warrantless, reckless, and, ultimately, self-destructive vengeance on humanity6. In this frame, austerity appears as a kind of economic sadism, which is not the intention but the result of systemic and structural forces. There are at least three aspects of revenge capitalism in operation today, though these are by no means exhaustive: the making surplus of whole populations who are dependent on capitalist markets for their reproduction, yet remain superfluous to the system’s own reproduction and, thus, left to die; the rise of the ‘hyper-enclosure’, by which I mean the extension of capitalism’s logics of primitive accumulation into the spaces of cognition, affect and sociality (for instance, through digital platform technologies that harvest data and broker connection and attention); and unpayable debts, which I will focus on here.

On the one hand, we have the kind of unpayable debts that are foisted onto whole nations, even though everyone knows that they cannot be repaid and, indeed, the austerity and privation they enforce means the conditions of repayment will never be approached. This imposition of unpayable debt has a long imperialist pedigree: a prime example is the way colonial powers imposed debt on the new Haitian nation in the wake of the revolution of the enslaved, a debt essentially to repay their former French ‘owners’ for the theft of their own bodies7. More recently, we have witnessed the imposition on Greece and Puerto Rico of such ruinous forms of debt financing that even mainstream financial institutions admit it will prevent their economies from reaching a state where actual repayment may be possible. This follows decades of similar forms of endless debt discipline wielded by the Global North (via financial institutions and intermediaries like the International Monetary Fund and World Bank) on nations in the Global South, which to all intents and purposes appeared as a kind of financial vengeance for the successes of decolonisation. Yet, this empire of unpayable debts also affects individuals in a rapidly financialising world. Austerity politics see the regressive enclosure of former public services (including health, education, transportation) and the transfer of costs and fees of social reproduction onto populations, and disproportionately, as Verónica Gago shows, onto women. When combined with stagnating (inflation-adjusted) wages and a financial services industry eager to offer new forms of securitised (meaning: globally tradable) consumer debt, this shift can produce an explosion of unpayable debt on a personal level8. In the US and in the UK, an increasing proportion of adults are expected to die in deep debt, and there is no respite for the younger generations who emerge with astronomical debts for improving their human capital (‘getting an education’) to take a chance on increasingly hostile, competitive and precarious labour markets9.

4.

There are many ways of framing such a situation. But revenge is not only evocative, it is highly suitable – it is as if the economic system itself (without any individual intending it or bearing any malice) is wreaking a strange vengeance on whole nations and populations. I propose the term ‘revenge’, because unlike crass sadism it implies a logic of retribution. Capitalism has always relied on regular incidents of vengeance of the powerful, or their laws to repress and punish workers and others who dare to rise up. The neoliberal revolution, from Pinochet’s Chile to Thatcher’s Britain and beyond, is a kind of reactionary political and economic vengeance against the social gains made by trade unions, students, women, minority groups and others, whose struggles in the 1960s and ’70s so unsettled conservative social factions. Capitalism has never been without revenge. But what I am more interested in here is how a system at large can be vengeful as it spirals deeper and deeper into financialised crisis. Yet, vengeance for what?

As always is the case with the vengeance of the powerful, no infraction or crime actually needs to have been committed: more often it is pre-emptive. Martin, again, has theorised that financialisation is key to how capitalism was reconfigured in order to control, contain and conscript the energies of decolonisation movements in the late twentieth century – literal decolonisation in the Global South, metaphorical decolonisation (of bodies, of social relations) in the Global North10. In both cases, unpayable debt operates as a means to discipline, control and extract value from social actors (individuals or whole nations), while still maintaining flexibility and adaptiveness. As both David Graeber and Maurizio Lazzarato have illustrated, unlike direct violent repression or colonial force, debt has the added benefit of making the debtor imagine their plight as being their own fault and moral failing11. Though, as Miranda Joseph and Jackie Wang state, the notion of the ‘indebted man’ needs to make way for a more nuanced account of how debt actually works on and through different gendered, racialised and classed bodies12.

Capitalism, obviously, doesn’t have intentions and so it can’t be vengeful per se; it is not human and much analytical and political grief will come from attributing human characteristics to it. Yet, metaphors are all we have. And so I propose that revenge is an oddly fitting way to describe a form of capitalism that, in its own utopian drive, creates conditions which appear not only exploitative and oppressive, but irrationally vindictive.

Unpayable debt, debt that sabotages the debtor’s ability to repay or even reproduce themselves, is one such moment of nihilistic capitalist vengeance. Underneath the unpayable debts ‘from above’ are the unpayable debts ‘from below’. These are claimed (or ought to be claimed) by those whose stolen lands and labours built the racial capitalist world system, a system which now superintends a world of coercive unpayable debts from above. These include the unpaid, unacknowledged debts for slavery, for colonialism, for the generation after generation of exploited labour and its accompanying vengeful forms of enforcement. These silenced horrors are the midden on which today’s economy is built13. These debts are unpayable not only because those in power refuse to pay (or acknowledge them in the first place), but, arguably, because there is not enough money or resources in the world to repay them without bankrupting the capitalist economy that was built upon these debts. The crimes and harms are too monumental and too foundational to capitalism to be accounted for in its ledgers. More profoundly, there is a strong argument that even if there was enough capitalist money to pay, it would be the wrong form of compensation: the debt is unpayable because it is not financial, but ontological. Those vengeful systems that wrought colonial violence and whose operations continue to inflict structural violence must be abolished, such that the violence ends once and for all.

5.

Prior to their revolt, the enslaved people of Haiti were subject to constant, brutal and dehumanising vengeance from their enslavers, compelling historian C.L.R. James to muse in his magisterial The Black Jacobins that ‘the cruelties of property and privilege are always more ferocious than the revenges of poverty and oppression. For the one aims at perpetuating resented injustice, the other is merely a momentary passion soon appeased’. He continues that, ‘When history is written as it ought to be written, it is the moderation and long patience of the masses at which men will wonder, not their ferocity’.

It was, in fact, the fear of the potential vengeance of the enslaved that drove the slave-holding class and their agents to perpetuate the normalised atrocities of their rule14. Perhaps it is always thus with the powerful: they mask their own sadistic and vengeful character, necessary to enforcing their exploitative rule, by projecting onto the subjugated the bestial (yet all-too-human) thirst for vengeance. In the name of taming, averting and suppressing that vengeance, all pre-emptive vengeance is justified. Vengeance functions in the imagination of the powerful in tandem with the logic of sub-humanisation. In the same way that they imagine those whom they enslave or oppress as just barely human (or barely not inhuman), vengeance is understood to be uniquely human, but abjectly so15. Animals may react to harm or fear, but do not appear to plot revenge, nurse vendettas, or dream of poetic ways to reclaim a blood debt – only humans do. But what kind of human? Only the worst. As Nietzsche observed, those who would elevate themselves as the legitimate masters of the world and their fellow human beings would declare themselves above petty vengeance and as subjects of the law – even when vengeance is deemed honourable, it is only vengeance inflicted on those deemed one’s peers16. And yet, the system that so empowers and ennobles the slaver is itself based on endless vengeance.

6.

It is important to think about the vengefulness of systems and the particular vengefulness of today’s form of financialised capitalism (and its utopian drives), if we want to understand the recent political turn towards neo-authoritarian politics. These politics, almost universally, are characterised by a kind of political revanchism: ‘it’s time to take back our country, even if it kills us’. Such authoritarianism does not conspicuously promise a better, utopian future, and the oath to return to some past seem dubious, even to adherents. But it does promise a revenge on those who can be blamed for some perversion or deviation in the past, those to whom ‘we’ (or at least some among us) were too kind, too generous, too welcoming, too compassionate, and who ‘stabbed us in the back’. The affects and existential miseries that drive these revenge politics – this will come as no surprise – bubble up from the quagmire of contradictions of revenge capitalism itself. Unable to name capitalist exploitation and alienation as the source of their misery, yet all too aware capitalism is foreclosing the future, whole polities pivot around a politics of bilious invective which treads the well-worn paths of sexism, racism and xenophobia. When no utopian horizon is available, except endless commodification, financialisation and competition unto death, when we live in the shadow capital’s utopia, all that is left is revenge.

Is there a possibility for a radical, revolutionary vision from within this situation? It is valuable here to recall Walter Benjamin’s fateful ‘Theses on the Philosophy of History’, his last major work. Writing of the tragic political reversal of the Weimar Republic, which formed with Germany on the brink of a communist revolution (led by the Spartacists Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht, who were assassinated on the orders of the ‘moderate’ Social Democrats) and ended with the ascendancy of the Nazis, Benjamin observed:

In Marx it [the proletariat] appears as the last enslaved class, as the avenger that completes the task of liberation in the name of generations of the downtrodden. This conviction, which had a brief resurgence in the Spartacist group, has always been objectionable to Social Democrats. … [who] thought fit to assign to the working class the role of the redeemer of future generations, in this way cutting the sinews of its greatest strength. This training made the working class forget both its hatred and its spirit of sacrifice, for both are nourished by the image of enslaved ancestors rather than that of liberated grandchildren.17

In other words, for Benjamin, some measure of movement for liberation not only looks forward to brighter utopian horizons, but swears to account for the unpayable debt owed to all those who came before in the struggle. It is this imagination of avenging history that provides the proletariat with their greatest strength: the abiding hatred of oppression and a willingness to undertake sacrifice. When a politics of liberation refuses to engage with this ‘avenging imaginary’, it is easily co-opted and harnessed by reactionary forces.

7.

I don’t think there is anything easy or comfortable about this formulation, but it does have some undeniable resonance for today. For my part, I have sought to meditate on what it would mean to cultivate an avenging imaginary around unpayable debts from below. These debts are not honoured or even acknowledged in the utopian ledgers of revenge capitalism nor in public discourse, until, that is, they express themselves in conventional legal and economic terms which allow them to be easily recuperated within that system. These might include demands for compensation, reparations and repatriation for losses suffered due to imperialism, environmental catastrophe, heinous exploitation and more. Today, there are many such efforts occurring around the world, which include attempts to retrieve ancestral human remains and artefacts looted during colonialism, demands by descendants for reparations for the transatlantic slave trade, and the insistence on compensation for the theft of Indigenous peoples’ lands and resources18. These movements are vital, especially as they call together a radical constituency of claimants who discover their collective potential in common struggle and represent a reminder that the high-minded rhetoric and cultural supremacism of the coloniser is built on theft and violence. When these claims for repayment of the debt enter into courts and other official venues, they continue to do this work, demonstrating the decidedly illiberal, racist and exploitative origins of the very ‘liberal’ order that deigns to sit in judgement now of its own crimes. Yet, the great risk is that the official capture of these struggles, which are always hedged with questions of monetary compensation and ‘reconciliation’ of accounts (a closing of the books), sacrifice their greatest and most radical asset: the very unpayability of the debt, its vengeful afterlife.

Writing of the ongoing processes of settler colonialism in North America and the kind of racial ordering it demands, Unangax theorist Eve Tuck, writing with C. Ree, proposes a disturbing rebuttal to the recent enthusiasm, especially in Canada, for a state-led initiative towards reconciliation.

Settler colonialism is the management of those who have been made killable, once and future ghosts—those that had been destroyed, but also those that are generated in every generation[…] Haunting, by contrast, is the relentless remembering and reminding that will not be appeased by settler society’s assurances of innocence and reconciliation. … Haunting doesn’t hope to change people’s perceptions, nor does it hope for reconciliation. Haunting lies precisely in its refusal to stop. Alien (to settlers) and generative (for ghosts), this refusal to stop is its own form of resolving. For ghosts, the haunting is the resolving, it is not what needs to be resolved. […] Haunting is the cost of subjugation. It is the price paid for violence, for genocide. […] Erasure and defacement concoct ghosts; I don’t want to haunt you, but I will.19

What would it mean to refuse payment, or to insist that the debt cannot be repaid in the stolen coin of empire? What would it mean to refuse to forgive as there is no evidence that the conditions and structures that led to violences of the past have substantially changed? What would it mean to suggest that there is not enough money in the world to pay back the debt – the same money, no matter in whose pocket, only perpetuates the very atrocities now being assuaged? What would it mean to cultivate an avenging imaginary in which the closure of the debt is the abolition of the economy as such?

The post “Capital’s Vengeful Utopia: Unpayable Debts from Above and Below” in L’Internationale appeared first on Max Haiven.

May 13, 2020

Capitalism as Revenge :: Revenge Against Capitalism An Interview with Max Haiven in Socialism and Democracy

The journal Socialism and Democracy has published an edited transcript of a interview with me by C. S. Soong of KPFA’s long-form interview show Against the Grain. (You can listen to the interview here).

Below is an uncorrected version of the text. You can download a copy of the published article here.

Capitalism as Revenge :: Revenge Against Capitalism

An Interview with Max Haiven by C. S. Soong

C. S. Soong: Revenge in the context of capitalism has been on your mind a lot lately. Why?

Max Haiven: I think what we’re seeing around the globe is the rise of a certain kind of revenge politics. As the capitalist system hovers on the brink of collapse, it unleashes forms of cruelty and irrational behavior that have catastrophic impacts on people’s lives. In response, we are beginning to see whole polities and populations develop repertoires of political action that, at least from certain perspectives, appear as if they are largely motivated by revenge. I think this is probably easiest to see in reactionary movements that now stalk the political landscape, from the far right to various fundamentalist religious movements to the kinds of ethno-nationalism and muscular proto-fascism that we’re seeing in many countries around the world.

But I think there is a danger in simply identifying the tendency toward political revenge or revanchism as purely a right-wing and reactionary movement. If we’re honest with ourselves, many of us – even those who yearn for justice, peace, and human solidarity – have felt a kind of burning desire for revenge for what is being done to our fellow human beings and to the earth. What I’ve taken up is what I think is a very dangerous task: to really dwell with the spirit of vengeance, a spirit we deny at our peril. I want to excavate its histories and try to understand revenge not as something that has surprised us by coming from the margins of society to the center, but as something that in some ways has always been with us. Revenge is, of course, an eternal human passion, but I’m interested in revenge as a political tendency that, while quite active in the present moment, has pervaded the history of both capitalism and colonialism.

Soong: How do or should we feel about actually taking revenge? In what ways might we be repelled by the prospect?

Haiven: It is a repugnant concept. I think part of that repugnancy is something we have been educated and habituated into. Many of the greatest works of human literature and culture across civilizations have warned us about the dangers of revenge, about the ways it creates self-perpetuating cycles of violence and retribution that have brought down human societies and civilizations.

I don’t want to diminish the very real dangers of revenge, but I want to also identify something strange today, and arguably throughout the history of capitalism. It’s something I date back as far as the 1500s, where the ruling class and the colonial oppressors deployed a narrative that blames and accuses the oppressed and exploited of the world of fanatically seeking revenge. This is a narrative that can only interpret our grassroots forms of resistance and rebellion as a kind of bestial reaction. As a result, we have developed a phobia toward revenge which, I think, doesn’t ultimately serve us well.

Soong: What does our fear of revenge prevent us from doing? Why should we push back against a phobia that seems to me quite natural?

Haiven: Our phobia toward revenge leaves us bereft of a way of explaining two things. The first is the way that a system can take revenge on people without any one person wanting or intending it. Revenge is not just an individual human drama; it’s also a systemic or structural pattern. Second, this dominant narrative precludes us from really grappling with what Frantz Fanon called the “legitimate desire for revenge,” something that underscores the experience of many people who are oppressed and exploited. It seems to me that if we ignore this desire for revenge, its associated sentiment and affect can be picked up quite easily by reactionary forces.

Soong: When you say that elites fear revenge or perhaps fantasize that the masses wish to take revenge against them, are you saying that we in a sense internalize that and we begin to understand our desires for revenge against the system as being deplorable and contemptible?

Haiven: Indeed. I have traced this tendency back many centuries to the philosopher and statesman Francis Bacon, the father of the scientific method. As Vandana Shiva and others have noted, Bacon’s work, which continues to shape the dominant regimes of capitalist technoscience, is animated by the theme of patriarchal violence. You can see this in the way Bacon speaks about tearing the veil away from nature and calls for subjugating it to the human, and specifically masculine, will.

Late in his life Bacon made, in one of the first treatises on revenge written in English, a very strange distinction. In his 1625 essay “On Revenge,” Bacon suggested that sometimes what he calls “public revenges” – that is, acts of revenge taken by a ruler or another elite member of society in the name of the public good — are legitimate. On the other hand, private revenges are demonic; they have a kind of cancerous presence within the political sphere. There’s this insistence that revenge taken outside of the “legitimate” forms of state violence and coercion constitutes a bestial and subhuman act that can only lead to utter chaos and disorder. I think this constitutes a clear and influential example of the ruling class (as a kind of shorthand for all of those who perpetuate and benefit from oppression and exploitation) defaming the vengeful actions of the oppressed. That defamation has in many ways been internalized so that, for instance, we come to a moment now where to even speak of revenge feels dangerous and bestial.

Soong: Francis Bacon’s denigration of private revenge, of vengefulness from below, hinges, you’ve argued, on the figure of the witch. Make that connection for us.

Haiven: Bacon famously said that those who dedicate themselves to taking revenge lead the lives of witches, and that therefore their lives will end in misfortune. For Bacon, revenge has an unnatural or supernatural quality. In this he was likely influenced by many years of Christian scriptural interpretation, from which emerged the idea that a person should not take revenge. Instead, God will take revenge in the end times in His final judgment. As Jesus Christ advised his followers, the duty of humans was to turn the other cheek and to render unto Caesar what is Caesar’s, to allow the law of the land to prevail rather than to take vengeance for crimes and injustices done to oneself. It’s a very conservative reading of Christian scripture.

So Bacon is referring to witches as figures possessed by the devil or by devilish desires to take revenge. But the irony is that, as Carolyn Merchant and other feminist scholars have demonstrated, Bacon himself was at the very least a supporter of King James I’s passion for witch hunting, and of the associated use of torture to extract confessions. Indeed, there’s evidence to suggest that Bacon imported this notion of violent gendered interrogation into his conceptualisation of the scientific method. Silvia Federici notes that the witch hunts were pivotal to the introduction of forms of ruling-class power that would eventually emerge under capitalism. The witch hunts were a key means by which the power of commoners and their communities was broken, by the specific targeting of women as politicians, knowledge holders, and healers. Communities of commoners were reduced to a state of vulnerability whereby they could be transformed into a waged working class to be exploited. So it’s ironic that Bacon would name as witches those who were possessed by a desire for revenge, when in fact he was involved in or at least complicit with development of methods for labeling women (and men as well) as witches who could then be, and were, the targets of revenge by the state. All of this points to the ways that power frames its opponents as supernaturally fixated on a kind of vengeance.

Soong: You’ve spent a lot of time engaging with the writings and ideas of Karl Marx. Did Marx write a lot about revenge?

Haiven: No, although it is a theme that runs throughout his work. Marx sought to delineate a scientific way of understanding history, politics, and political economy. He worked on identifying the underlying currents of capitalist development so that workers could rise up against the capitalist class. So he wasn’t that interested in what would probably have been considered, in his era, a humanist theme like revenge. However, there are a few moments in his work, as a young scholar and an older thinker, in which he represents revenge not as something that the working class will seek to exact on the ruling class but as something enacted by the ruling class, for seemingly no reason, on the working class and on oppressed peoples around the world.

For instance, Marx speaks of the British reprisals against the First Indian War of Independence of the late 1850s, which the British called the Sepoy Mutiny, as being unexceptional in the history of colonialism. The British brutally killed hundreds of thousands of people in response to an uprising of Indian soldiers against the East India Company. Marx points out that this form of revenge, and the revenge that was taken by Indian soldiers against British colonial officials, was the natural offspring of the forms of revenge that had been essentially baked into British colonial rule. To paraphrase Marx: revenge was an organic part of British rule; it was integral to the cruel and sadistic behavior that always stands as the hallmark of colonialism and of the rule over colonized populations.

Marx also wrote about the kinds of sadistic revenge taken on what we might now call the surplussed population of unemployed working-class folk in England, people who were consigned to poorhouses established by the state or by ruling-class charities. But of course these poorhouses were essentially torture chambers for the working class; they were places where adults and children were subjected to forced labor, people’s medical needs were not met, and humanity was degraded to its lowest possible state. Marx perceives these facilities as institutions of revenge, where the ruling class essentially takes vengeance (disguised as charity) on the very people upon whom it is parasitically feeding.

Soong: If Marx believed that vengeance is practiced more by the oppressor than by the oppressed, did he say anything about whether revenge taken by the oppressed and the exploited is justified — or can, in certain instances, be justifiable?

Haiven: I have not found statements to that effect, although I think Marx would agree that revenge is sometimes justified. Marx would probably agree with the great Marxist historian and theorist C. L. R. James: to paraphrase James, when the records of history are written as they truly should be written, we will marvel at both the restraint exercised by the oppressed in their uprisings, and the routinized cruelty of the oppressors in their systems of power.

I think Marx — and Engels perhaps expresses this, in various letters, more clearly than Marx – believed that through a scientific understanding of capitalist society, and through the establishment of communist parties that could organize the working class to transform the world rather than simply to take vengeance for their particular conditions, working-class people could rise above their desire for revenge. They could become a world-historical force that would not just annihilate the individual capitalists who exploited them or allowed their children to die of starvation or disease but take what I would call an avenging stance toward capitalism as a system.

Soong: One historical figure who had a lot to say about revenge was the leader of the Haitian revolution, Toussaint Louverture. What did Louverture say about revenge and its importance?

Haiven: The language Louverture used to marshal the enslaved Africans in Haiti and propel them toward revolutionary action was often filled with promises of revenge. It cannot be denied that revolutionary struggles, including the Haitian Revolution, are extremely bloody and vengeful against those who are perceived to be the agents of oppression. But I want to turn our attention away from the spectacular violence of revolutionary moments, especially revolutionary moments in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, because they can distract us from underlying systems and structures. Instead, I want to focus on how revenge was used by Louverture as a means to mobilize a revolutionary constituency. Louverture, as many people have pointed out, was attempting to bring together a revolutionary movement in Haiti that would take the French revolutionary sentiments of liberté, égalité, and fraternité at their word and extend them to all citizens. In Louverture’s eyes, avenging the enslavement of African people and the horrific forms of vengeance that the slave owners enacted upon their slaves (for no reason other than their own sadistic pleasure and their fear of uprisings) became a moral task that bound together the revolutionaries in an enterprise that involved and required much more than revenge or revolutionary bloodlust. It was about claiming a measure of justice that couldn’t exist within the imagination of the colonizer and slaveholder.

So there’s something here about revenge that breaks us out of the moral and religious and philosophical framework developed by the oppressor. It allows for a new reckoning of justice to emerge that could be the foundation of a different social order — not simply a reversal of fortunes, where the oppressor becomes the oppressed and the oppressed becomes the oppressor, but actually a new moral universe where the underlying causes of the original oppression are abolished.

Soong: In thinking about what a sort of productive or generative revenge might look like, I understand you’ve been drawn to a poster produced in the wake of the 1886 Haymarket massacre in Chicago. What does that poster exhort workers to do, and how is rebellion or resistance framed?

Haiven: Yes, there’s a famous poster published by the German anarchist August Spies in response to the Haymarket Massacre. The poster exhorts Spies’s fellow workers to rise up and take revenge against the ruling class, which has sent their agents, the police, and armed gangs to murder striking workers. In the poster Spies likens the kind of revenge the state has taken on these striking workers and protesters to the kind of everyday revenge that the system is taking on the families of working people, especially migrant workers in Chicago.

But more generally, that poster—and many other cultural works from that famous period of labor unrest—asks workers to see or recall themselves as the inheritors of a long line of injustices. The poster calls upon workers to avenge not only the crimes and cruelties done to them and their families but also the injustices perpetrated over the course of decades and even centuries. I think this is most poetically expressed in Walter Benjamin’s enigmatic and haunting reflections in his “Theses on the Philosophy of History” where, to paraphrase, Benjamin says that the problem with German Weimar Social Democracy in the leadup to the Nazi period was its excessive focus on making an appeal to the working classes on the basis of the promise of liberated grandchildren. The claim was that through socialism, the future would be redeemed as a place where one’s descendants could live in peace and abundance. Benjamin wrote that this rhetorical approach severs the sinews of the working class’s greatest strength – namely, its spirit of vengeance and its spirit of sacrifice. These spirits are tied to the idea of avenging one’s ancestors rather than focusing on one’s grandchildren.

Benjamin’s argument, I think, is that social democracy offered this triumphalist vision where if you simply join the party, and you subscribe to its vision of a future we’re all marching toward together, that would be sufficient. But in Benjamin’s view what was needed was a sense that we have to overcome a long history of oppression and exploitation together, and that the future-focused vision of social change put forward by the Social Democrats for very instrumental purposes neglected the deep-seated resentment, anger, and antipathy that is at the core of the experience of being oppressed and exploited. In the absence of dealing with those sentiments in a productive way, in a way that generates solidarity and a vision for a future in which the past will be redeemed, this emotional territory, Benjamin believed, was left open to appropriation by reactionary forces – notably the Nazis. The Nazis were able to offer a very different way for working-class people to get a kind of revenge against the system, one that was ultimately catastrophic and that in fact deepened and worsened their oppression and exploitation.

Soong: What you’ve learned about the former White House strategist Steve Bannon and his career trajectory may help deepen our understanding of the rhetorics and realities of revenge politics. At one point, Bannon worked in the arenas of finance and financialization. He later became a Hollywood producer and co-produced a film called Titus, released in 1999. This was an adaptation of Shakespeare’s play?

Haiven: Yes, the film was based on Titus Andronicus, written very early in Shakespeare’s career. That play is about a Roman general who, after fighting the Goths for many years, returns to Rome, a city corrupted by greed and by internecine struggles waged by and among various political factions. Titus, the general, is represented in the play – and there are parallels here to the first season of the TV series Game of Thrones – as a noble soldier who finds himself in the corrupt, backstabbing world of politics. Titus and his whole family become the target of various political machinations that lead several people to be murdered, after which Titus swears an oath of vengeance that he then exacts, in sadistic fashion, on all of his enemies. At some point in the play the Goth queen, who is working in a kind of conspiracy with the racialized figure of Aaron the Moor, is forced to eat her own adult children. And one of Titus’s daughters has her limbs cut off. It’s an incredibly bloody play that most critics agree is a bit of a discredit to Shakespeare. Nonetheless, it was extremely appealing to Steve Bannon.

Soong: What did Bannon find so appealing about the play, and how was the theme or metanarrative of Titus Andronicus expressed or interpreted in Bannon’s film Titus – and perhaps as Bannon moved over to Breitbart News?

Haiven: I want to begin by saying that I’m not one of those who believe that Steve Bannon is some sort of evil genius. He’s just a bully and a scumbag who happened to be in the right place at the right time. So I don’t want to contribute to the cult of personality around Bannon. But I do find him a useful index for deeper shifts in our age.

I think Bannon liked “Titus Andronicus” because it’s a kind of hypermasculine martial drama, where the individual who’s willing to break the norms and conventions of society effects a cataclysmic social transformation. We know from Bannon’s own interviews and discussions that he has a very apocalyptic imagination. He believes there will be a global race war that will culminate in a new global agenda and a reorganization of human life on the planet. I think the “Titus Andronicus” narrative appealed to Bannon precisely because it is so utterly nihilistic in many respects.

I think Bannon also sees in Shakespeare’s play an allegory for an America that’s like Rome when it was an empire in decline – beset by decadence and corruption and overseen by self-serving elites who used their hegemony over art, culture, media, and politics to rule as a very small minority over a very large majority. The figure of Titus is a kind of elite figure who comes into that world and destroys it from within. So in some sense I think the film “Titus” can be seen, in retrospect, as an allegory for how Bannon came to view Trump: as a thuggish general of capital who could come in and disrupt and destroy the system from within. That system, Bannon believed, had been corrupted by self-serving elites who had marshaled the language of liberalism to perpetuate their power.

Soong: Let’s widen the scope, as I know you are inclined to do, from figures like Bannon and Trump to capitalism as a system and a structure. You’ve written extensively about the phenomenon of financialization. How would you define financialization, and what has it done to workers that might be characterized as revenge?

Haiven: Financialization, in a limited sense of the term, refers to the increased power and influence of the financial sector of the capitalist economy. That sector comprises institutions like hedge funds, investment banks, and bond-rating agencies that many of us became familiar with during the 2008 financial crisis. Their influence is, of course, economic, in the sense that they have immense power over other capitalist firms, but it’s also political, in the sense that most governments around the world (with the exception of oil-exporting countries) are extremely indebted and need to borrow more money every year to make ends meet. This is largely because these governments have chosen not to tax the richest members of society but instead have borrowed the money they need – from, often, these very same wealthy elites. So financialization has had profound and wide-ranging economic and political effects. But I and others have argued that there are also deep sociological and cultural consequences. Sociologically speaking, as the financial sector grows and as public spending diminishes, we begin to see almost every institution of society transformed into a kind of financialized asset.

Soong: What concretely do you mean by this? Give us an example.

Haiven: One that I often point to is the university. Once upon a time we imagined that the university existed to produce research in the public interest and to educate a new generation of citizens to take their place in society. We now understand the university to be something quite different: a place where young people go tens of thousands of dollars into debt to purchase a credential that they can then use to try to sell their labor power in the context of an extremely hostile labor market. Education has thus become an individualized investment rather than a social responsibility.

On a deeper level, financialization has transformed each of us into a kind of miniature investor. We’re being constantly instructed and exhorted to see everything of value in our lives, from our education to our relationships to our housing to our community, as assets that can be leveraged toward our own personal, competitive gain. This has had a massive and catastrophic impact on individuals and communities, as people reconfigure their imaginations to see society as a hostile and competitive environment. And this, I think, has a lot to tell us about the forms of revanchism that have emerged politically in this moment of capitalism. Because if you are unable to see yourself as part of a society nurtured by what Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. called bonds of mutuality, and if you see everyone else as a competitor, then you have a very difficult time understanding that a society might need to redistribute wealth or address systemic and structural issues. You see attempts to redistribute wealth or address systemic and structural issues only as impositions on your own competitiveness, especially if you don’t see yourself as a beneficiary of that redistribution.

So, for instance, we’ve seen in the last forty years of financialization and neoliberalism a visceral antagonism toward anyone perceived – and often the perception is incorrect – to be gaining some sort of benefit from a redistributive state. And this vitriol is almost always racially coded. It presumes that some sort of racially normative white majority is being taken for a ride by opportunistic, racialized people who are claiming unfair advantages or benefits from the state. The narrative that Bannon was able to spin at Breitbart and in the Trump campaign was one of making America great again: we need to “return” to a moment where we could all be our competitive best, and where there are no advantages accruing to any particular group. All of this is based on a completely skewed notion of how society actually works, and it draws on a reservoir of deep racist sentiment within American culture and politics.

So financialization is part and parcel of this political transformation in the imagination that is deeply tied to the culture of racialized fear and resentment that has been so acutely marshaled by revanchist political movements on the right.

Soong: How do attitudes toward women and feminism play into this? To what extent are many of the men who’ve lined up behind Bannon and Trump driven by an understanding of feminism as a threat to their way of life? And what parallels do you see between the condemnation of women’s movements and their agendas and the witch hunts you spoke about earlier?

Haiven: As a number of feminist scholars have pointed out, one of the most successful rhetorical strategies of the far right in recent years – and one that’s been embraced by the revanchist Republican agenda – involves accusing a nebulous alliance of feminists, queer people, and “liberals” of conducting witch hunts against well-meaning and even heroic white men who, for instance, dare to speak their mind about issues of inequality or oppression in our society. The far right has effectively framed university campuses as the sites of these so-called witch hunts against courageous men who are prevented by some sort of conspiracy from sharing their brilliance with the rest of us.

This language of the witch hunt, which has been mobilized so effectively, clearly delineates in my view the kind of patriarchal and misogynistic logic at work. The idea is, and has been since Francis Bacon’s time, that women are irrationally dedicated to a certain kind of revenge that, if allowed to blossom (i.e., if it’s not suppressed by men), will undermine or even destroy the body politic. This is a very clear theme in Bacon’s essay and in the writings of many other Western male elite philosophers since his time: the oppressed can’t be trusted to manage their own affairs and their own lives because they have some sort of pathological tendency toward vengefulness.

We see, then, various forms of revenge being orchestrated and taken by reactionary forces upon women and people of color and others, justified in the name of preventing a revenge that those forces assume will come from the oppressed. So you have, for instance, the rise of what’s called “revenge pornography,” which has become a huge problem. Here you have mostly men who have been jilted, or who are not allowed to be in relationships with women they find attractive, circulating on the web pornographic images of those women that may have been shared in confidence or may be completely fabricated, all as a means to undermine and discredit that individual. Revenge pornography is an example of the kind of preemptive forms of vengeance that oppressors take in order to shore up and buttress their power at a moment when it feels under threat. They see revenge as being necessary in order to prevent the oppressed – in this case, women within a patriarchal society – from themselves taking revenge, which in the right-wing imagination would be the replacement of men by women and the eradication of “traditional” masculinity.

Soong: You referred earlier to an avenging stance toward capitalism as a system. “Living well is our best revenge”: that message, those words, have been spray-painted on many walls and structures in southern Europe since the advent of austerity measures in 2010. Does that suggest to you a fruitful way of thinking about revenge?

Haiven: It does, as long as it’s separated from a consumerist and individualist notion of what it means to live well. There’s a long history of movements and philosophers thinking about what a good life would mean and demanding a transcendence of the conditions of the present. There is a danger of saying that living well within the system is enough; that sentiment is deeply problematic because, under capitalism, the ability of any one of us to live well is predicated on the oppression and injustice done to others, whether they are the people who build our digital technology in sweatshops or the people around the world – mostly from formerly colonized countries – who extract the raw materials that become the material of our lives.

But I do think that the phrase “living well is our best revenge” offers an avenue for envisioning revenge in a more generative light. I call this “avenging.” To imagine a world in which we can all live well is, I think, a step toward the kind of avenging that Walter Benjamin had in mind — not simply the kind of bloody retribution enacted upon the individual agent of oppression or exploitation, but rather an overturning of the whole system that allowed that oppression to arise in the first place.

Soong: Many people who want to change the status quo are enacting alternatives to the system. It sounds like you’re not necessarily completely aligned with such people, and I say this because an important part of your focus is doing something about what’s been hurting us this entire time.

Haiven: Yes, quite so. The underlying philosophical claim of this project is that the powerful dominate the discourse and institutions of “justice.” As financialized and other systems fall into a state of decrepitude, the insistence that capitalism and the state are the only arenas in which we can get justice shrinks the space in which we can locate and pursue the justice we deserve: the good life or the “living well” that is our fundamental birthright as humans on this planet. In those moments, the demands for justice articulated by oppressed and exploited and alienated people are increasingly heard by the system and by the agents of power merely as demands for revenge. And thus it has always been: the demands of the colonized for decolonization have been misinterpreted by the colonizer as brutal and animalistic cries for revenge. Working-class demands for the radical redistribution of wealth and the re-imagining of value have always been framed by the ruling class and the capitalists as inchoate, stupid, and unthinking demands for revenge.

So ultimately my argument is that we need to dream dangerously about what we deserve as compassionate, interconnected human beings on a finite but beautiful planet. And we need not to be afraid that those demands will be reframed by the rulers simply as vengeance. Perhaps underneath this word that carries so much weight and so much terror there lies another potential to overturn that system.

Soong: What on a concrete, material level might what you’ve called the “militant collective refusal,” which seems integral to this “avenging” that you speak of, look like?

Haiven: I couldn’t exhaustively catalogue it because I think people are refusing and resisting all the time. Sometimes it takes extremely small and subtle forms – for example, somebody simply being lazy at work, or somebody committing small acts of sabotage, or people choosing to identify themselves through the hegemonic discourse of mental illness as a means to exit the demands imposed upon them by capitalist society.

Many small refusals are occurring, and there are forms of great mass refusal as well, which are often ambivalent and ambiguous, complicated and contradictory. For instance, the major forms of social movement uprisings we’ve seen over the last decade, from the Yellow Vest movement in France with all its weirdness and ambiguity and fluctuations, to the Occupy Movement with the accusations that it had no focal point of demand, to the Movement for Black Lives that came up with concrete demands but also pushes for radical transformations of society. I think these things are going on all the time; we just need to train ourselves to look for them.

Soong: If vengeance represents a radical break from what’s come before, do you have any worries that actions taken in the spirit of revenge or avenging could run counter to the Left project?

Haiven: Yes, absolutely. Once you open the Pandora’s box of revenge, you can’t close it, as many great thinkers have counselled. But I think the important thing about thinking through revenge in the way I’ve framed it is that, by radically challenging the paradigm of philosophy, morality, and justice that’s been imposed upon us by the oppressors and exploiters, it creates the radical horizon of something truly new.

I think some of the greatest warnings about revenge carry this seed within them. Confucius famously said that before you set out on a journey of revenge, dig two graves. I’m haunted by that vision. I wonder what it would mean to recognize that we live in a political situation where those graves lie open: one for the system we seek to abolish, one for the thing or things we have become within that system in order to survive. In a strange way I think this echoes a vital lesson for struggle that we can take from Marx’s dialectic: the struggle is not just for one class to take revenge on another and elevate itself to power; it is to abolish class altogether in the name of universal liberation.

In the great films about revenge, there’s often this moment where the avenging hero rides off into the sunset, his or her task completed. But we never see what happens afterwards. There’s a great poem by Seamus Heaney that asks us to “hope for a great sea-change on the far side of revenge,” and my interpretation is that the voyage of revenge that Confucius talks about does have a far shore. It’s not just a voyage into the infinite darkness of the maelstrom. There is something on the other side, but it’s something that we will never be able to imagine or predict from where we stand now.

Notes

S. Soong holds a B.A. in history from Brown University and a J.D. from Cornell Law School. He’s also done graduate work in philosophy at San Francisco State University. C. S. co-produces and hosts the syndicated political affairs radio program Against the Grain. His written work has appeared in ColorLines, Turning Wheel, The Best American Nonrequired Reading series, and other publications.

Max Haiven is Canada Research Chair in Culture, Media and Social Justice at Lakehead University in Northwest Ontario and director of the ReImagining Value Action Lab (RiVAL). He writes articles for both academic and general audiences and is the author of the books Crises of Imagination, Crises of Power: Capitalism, Creativity and the Commons (2014), The Radical Imagination: Social Movement Research in the Age of Austerity (with Alex Khasnabish, 2014) and Cultures of Financialization: Fictitious Capital in Popular Culture and Everyday Life (2014). His latest book, Art after Money, Money after Art: Creative Strategies Against Financialization, was published by Pluto in Fall 2018. His book Revenge Capitalism: The Ghosts of Empire, the Demons of Capital, and the Settling of Unpayable Debts will appear in May 2020.

Fanon, Frantz. 1963. The Wretched of the Earth. New York: Grove, 139.

See Merchant, Carolyn. “The Scientific Revolution and The Death of Nature.” Isis 97 (2006): 513–533.

Federici, Silvia. 2005. Caliban and the Witch: Women, Capitalism and Primitive Accumulation. New York: Autonomedia

See, for example, Marx, Karl. 1857. “The Indian Revolt.” New York Tribune, September 16. https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1857/09/16.htm or Marx, Karl. 1849. “A Bourgeois Document.” Neue Rheinische Zeitung, January 4. https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx....

CLR James, The Black Jacobins: Toussaint L’Ouverture and the San Domingo Revolution, 2nd edition (New York: Vintage, 1989), 88-89.

Benjamin, Walter. 1969. “Theses on the Philosophy of History.” In Illuminations, edited by Hannah Arendt, 253–64. New York: Schocken.

The post Capitalism as Revenge :: Revenge Against Capitalism An Interview with Max Haiven in Socialism and Democracy appeared first on Max Haiven.

May 8, 2020

In conversation with Phanuel Antwi about REVENGE CAPITALISM

I was thrilled to talk with my friend Dr. Phanuel Antwi about my new book Revenge Capitalism: The Ghosts of Empire, the Demons of Capital, and the Settling of Unpayable Debts as part of my publisher Pluto‘s contribution to the Radical May series of online events.

VIDEO: https://youtu.be/rJuj1J2yyz4

AUDIO:

The post In conversation with Phanuel Antwi about REVENGE CAPITALISM appeared first on Max Haiven.

April 25, 2020

“No artist left alive” in Arts of the Working Class

My short, provocative essay “No Artist Left Alive” has appeared in the 11th issue of the Berlin-based broadsheet Arts of the Working Class. It argues that, as we emegre from that pandemic, artists and their supporters should consider anti-capitalist strategies not based on making life and economic conditions better for artists, but for all poor and working people, (the vast majority of) artists included.

Text below, but also check out the whole very interesting issue online, or, better yet, buy a copy in Berlin, London, Los Angeles and beyond.

No Artist Left Alive

No Artist Left AliveMax Haiven

Speculations on the Post-Pandemic Struggles of Cultural Workers Within, Against and Beyond Capitalism

Some of my best friends around the world are artists, and I’m deeply concerned about their economic wellbeing during and after the isolation and lockdown phase of the COVID-19 pandemic. I find myself vexed by the language of some of the calls I have seen to “rescue art,” at least when taken in isolation from wider struggles. I categorically support artists, in the immediate moment, getting money by any means necessary. But there is more at stake in the long term.

If these calls are tied to broader demands for the radical redistribution of social wealth and the fiscal decapitation of the super-rich by any number of direct or indirect means, then they resonate with the kind of politics that could facilitate artists and everyone else (except perhaps the decapitated elites) coming into a much better position post-pandemic.

But many calls to support artists specifically, in the absence of universal provisioning and a radical reimagination of value, risk once again making the image of the artist (as opposed to artists in their many actualities) a pawn in the machinations of capital’s reproduction.

Ultimately, what is likely best for artists is what is best for all workers: universal high quality free public services and the abolition of the wage-discipline of capitalism. These demands seem possible surprisingly today and are in a strange way an actually existing fact in the emergency. If artists make common cause with others, we might be able to preserve and extend these, and so abolish capitalism as such.

Going Down with the Ship

The agonizing reality is that, after the pandemic, any resurgence of the hegemonic “art world,” let alone the art market – and here I have in mind the field of visual art, even when it has exceeded “the visual” – must be seen to index the restoration of finance capital’s hegemony (which enriches the lion’s share of the collectors and benefactors), and therefore as catastrophically bad for humanity.

We must admit that “contemporary art,” all theoretical pleasantries aside, is the plaything of the world’s financialized super-rich. This can be observed at art fairs or auctions in the world’s metropoles, and in the careers of the roughly 250 global art stars whose work hangs in the yachts and penthouses of the world’s oligarchs. Any “return to normal” in the art market simply means that the proverbial boss is back from his luxury disaster-bunker vacation and has money burning a hole in his pocket.

An honest assessment of the financial fates of many of the world’s independent and critical galleries and arts institutions also depends on the largess of these finance capital and its functionaries. Sometimes this is direct, in the sense that these super elite sit on the boards of, make donations to, and otherwise, in a million tiny ways, help sustain these institutions – even state-funded institutions, let’s be honest. Other times it is less direct. We all know (I hope) that collectors, gallerists, and others use their influence over even independent and critical galleries and venues as machines to add value to works of certain artists in whom they are invested. We know that even the most eccentric and anti-market art spaces are compelled, by no fault of their own, to participate in generating the upward churn of sub-market “dark matter” (as Gregory Sholette has called it): the hidden mass of aspiring but unsaleable work on top of which the tiny fraction of marketable work depends. We are also all too familiar with the way the most esoteric and outsider margins of the art world function, against their will, to pull to its centre new provocative and antagonistic works that will be tomorrow’s art market bonbons.

Whether we care to admit it, a huge proportion of the global art world is essentially funded by family wealth: artists, gallerists, critics and others who can sustain unsustainable careers only thanks to the hidden largess of trust funds, parents and partners. Then there are all the rest, who sustain themselves waiting tables, teaching, doing sex work, surviving on a trickle of cash from distended graduate degrees, doing discounted labour for arts organizations, or otherwise hustling unto death.

What Remains Contemporary Now?

I don’t blame individuals, rich or poor, for the choices they make to pursue their passion in a sick and abusive economy. But for those art-adjacent people who want to abolish that economy and create a world in which everyone can pursue their passions, the time for collective honesty has come. There is, frankly, nothing more boring to me than the sanctimonious sniping about art’s entanglement with money that, today, so often passes for criticism or, worse still, for art itself. I’m curious what else might emerge if we, collectively, directed our critical acumen, our creative energies, our social talents, and our collaborative dispositions towards supporting the creation of and the fight for a new post-capitalist economy?

Insofar as “contemporary art” is sustained by and ultimately for the pleasure of capitalism’s super-elite, it necessarily demands a certain latitude of freedom from direct capitalist command. The art commodity’s value derives precisely from the fact that it is unlike any other commodity: it bears at very least the illusion of unalienated labour. Though how we can sustain this illusion in an era where art stars employ legions of precarious mini-makers in factory-like studios is a bit rich, if you’ll excuse the pun. To impose direct capitalist discipline on art would be to destroy precisely that which gives it its unique, supernatural value. Thus art retains some degree of “play,” if not autonomy, under capitalism.

Recently, I and a number of critics, including Marina Vishmidt, Suhail Malik, David Beech and Leigh Claire La Berge, have each argued that the financialization of the capitalist economy is based on processes that don’t simply suppress or thwart creativity and the imagination but actively seek to excite and harness it, and that “contemporary art” is in some senses a laboratory for these methods. This is especially important in an age of the so-called creative economy, in which every worker is increasingly exhorted to imagine themselves as (a mythological version of) an artist, eagerly plunging into a world of risk and uncertainty to leverage their passion, moxy and creativity towards growth in market share of their own personal brand.

In other words, far from demanding all artists produce propaganda, capitalism makes the artist themself (regardless of the content they produce – indeed, the more provocative the better) into a figure of their own propaganda.

Work or Die, Redux

But maybe that age has ended.

In the post-pandemic economy it is doubtful that capitalism may have need of such propagandistic illusions. During the pandemic, governments, at least in the (post-)imperialist Global North, are being forced to intervene to relieve the pressures that otherwise blackmail workers into working, offering a raft of social welfare provisions that have been demanded by social movements for decades: a hiatus on rents, some form of de jure or de facto basic guaranteed income, free public transit, and the provisional (re)nationalization of infrastructure.

We are, in a strange way, living through a kind of temporary dream version of the abolition of work itself as government orders prohibit many forms of economic activity, though, of course, millions continue to be compelled to work, notably front-line health and service workers, farmers, and caregivers. Many of us in isolation are, against our will (and with terrible effects on our mental health), now being compelled to live like a distorted images of the quintessential romantic artist: impoverished, unemployed, agonized by romanticized isolation, detached from the world, gripped by ineffable nostalgia and a sense of squandered potential.

In the aftermath, it is not unlikely that capital will demand states use every tool in their arsenal to compel us to “return to work,” to get back to “business as usual.” In such a situation, and in a moment where unemployment threatens to make us compete for a dwindling supply of bad jobs at depressed wages, the bullshit about “doing what you love” and “embracing the inner artist” is likely to be thrown out the window. Work or die, bitches.

“Fuck you, Artists”

In such a moment, artists may be encouraged to stridently claim that their work is work, that it deserves to be compensated. There may be demands for something like the US depression-era Works Progress Administration (WPA), which paid artists to do community-facing work as part of a broader economic stimulus spending package, but also as a form of social uplift. Artists, if they are organized, might be able to make some modest gains in certain jurisdictions. Yet what will become of contemporary art’s thus-far constitutive claims to a hostility (or at least an inhospitality) towards capitalism when it is explicitly (rather than implicitly) put to work towards that system’s rescue and restoration?

I certainly don’t think artists and their friends should forgo struggling to defend whatever legal and economic gains they have been able to make in various jurisdictions when it comes to wages, securities, and working conditions. Yet as tactically important as these may be, I am skeptical of the broader strategy. We are very likely to emerge from this pandemic in a profound global depression. The money that states have already borrowed and that they will continue to borrow to keep the economy afloat and provide disaster relief will be repaid to the world’s financial overlords. Perhaps unlike other sectors of capital, finance is driven by competition into a kind of frantic inability to see their own disastrous collective mismanagement of the very system they superintend and benefit from.

This will likely mean, sooner or later, drastic and brutal austerity, unless social movements mobilize to refuse to repay the debts. We should anticipate that state arts funding, where it has even survived until now, will be early on the chopping block. In spite of Richard Florida and company’s now canonical claims that investments in culture return in long term economic growth, in lean times when states play Russian Roulette to see who will take the bullet for the global economic meltdown, art will be a hard sell. Frankly, a large percentage of the population, forced to work longer, harder and, ultimately, for less, might celebrate an attack on the arts with a misplaced revanchist loathing. “Fuck you, artists: Work to death to bail out the rich like the rest of us.”

The Abolition of the Artist as an Economic Figure

Even if this somewhat dismal prediction doesn’t come to pass (which would require, let’s be clear, a profound and coordinated rejection of neoliberal economic thought on the part of governments and might even demand the nationalization of major sectors of the economy, notably finance), artists in the post-pandemic economy will still be faced with a choice.

On the one hand, they might continue to advocate for themselves, along with other arts intermediaries, as artists, which is to say as the special unicorns on capitalism’s storm-tossed arc. Accordingly, because they are unlike any other workers they need special rights, allowances, compensation, and protection. There is something correct and justified about this approach: like agriculture, health care, and the patriarchal family, capitalism cannot actually sustain those fields on which its reproduction depends. It requires the state, in large or small ways, to help keep these fields alive so the whole system and the society on which it depends doesn’t crumble. Art may get some bailouts precisely so that it can continue to produce nice things for the resurgent financial elite, who would otherwise be content to let artists die, like blithe aristocrats feasting during a famine.

On the other hand, there will be an opportunity for artists to make common cause with other workers (semi-)abandoned by capitalism, like a pampered purebred escaping the mansion to join the feral mongrels. Artists should in this moment be joining radical and ungovernable movements to demand, at very least that the emergency responses of the pandemic, which removed the economic coercion of capital, be extended widely and forever: basic incomes, rent suspensions, free high quality public services, the nationalization of critical infrastructure, and more.