Theresa Smith's Blog, page 96

August 29, 2019

The Week That Was…

I’m a bundle of nerves right now. Circumstances beyond our control have meant that my two eldest children (17 and 15) have flown off together for an overnight trip for their latest orthodontist check ups. They’ll need to get themselves around a bit in taxis and make sure they get to their appointment on time and the airport for coming back home. Fortunately, they can stay with family instead of a motel, but it’s nerve wracking leaving them to do this on their own. Sometimes I curse rural living where the orthodontist is 10 hours of driving away! Airfares just about break the bank out here too. They’ll be gone almost exactly 24 hours. I’ll be counting each one!

[image error]

~~~~~

Joke of the week:

[image error]

I actually had hair like this, but brown!

August 27, 2019

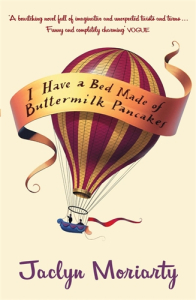

Book Review: I Have a Bed Made of Buttermilk Pancakes by Jaclyn Moriarty

About the Book:

A fairy-tale for grown-ups.

The Zing family lives in a misguided world of spell books, flying beach umbrellas, and state-of-the-art covert surveillance equipment. There’s a slippery Zing, a graceful Zing, and a Zing who runs as fast as a bus. But most significant of all, there’s the Zing Family Secret: so immense that it draws the family to the garden shed for meetings every Friday night.

I Have a Bed Made of Buttermilk Pancakes is a grown-up fairy-tale, and a mystery set in the suburbs. It’s about what happens when hope leads to sad and hilarious mistakes and when mistakes lead to hope once again. It’s about what happens when you meet a Zing.

The first adult novel from the award-winning author of Feeling Sorry for Celia and Finding Cassie Crazy.

My Thoughts:

“The three-legged race was not pointless. You used these skills when you ran in the rain with your arm around your lover’s waist.”

There is an element of Dr. Seuss prevalent throughout this novel, a kind of “Who-ville” aspect that really appealed to my quirky sense of humour. I read my first Jaclyn Moriarty earlier this year – her latest release for adults, Gravity is the Thing – and her style had instant appeal for me. I Have a Bed Made of Buttermilk Pancakes was first released back in 2004, so it has been a long time between adult fiction releases for Jaclyn. This novel though, is quite extraordinary. Truly original and so much fun with a fair bit of poignancy thrown into the mix. Jaclyn writes with an emphasis that jumps right off the page along with well-timed irony and plenty of humorous instances of stating the obvious – even if it is only with introspect. It is quintessentially Australian without any stereotypes and it dates very well – almost a classic in the making. At the heart of this novel is a mystery like no other and it amused me greatly once all the pieces of this charmingly puzzling book began to fall into place. If you read Gravity is the Thing this year and have a yearning for more of Jaclyn Moriarty, then wind back the years and pick up I Have a Bed Made of Buttermilk Pancakes. You will be utterly delighted with it.

“The complication was this: that, sometimes, in the darkest part of the night, she wished that the Secret continued. While her cheeks burned, angry and humiliated by their surveillance, somewhere in her heart was the cold recognition that now she was truly alone. It was almost as if, all her life, she had intuitively known they were watching and had basked in the limelight.”

About the Author:

Jaclyn Moriarty grew up in Sydney’s north-west and studied Law and English on three continents – at Sydney University in Australia, Yale in the US and Cambridge in England. She spent four years working as a media and entertainment lawyer and now writes full-time so that she can sleep in each day. She lives in Sydney.

[image error]

I Have a Bed Made of Buttermilk Pancakes

Published by Pan Macmillan Australia

Released in 2004

August 26, 2019

Book Review: The First Time Lauren Pailing Died by Alyson Rudd

About the Book:

Lauren Pailing is born in the sixties, and a child of the seventies. She is thirteen years old the first time she dies.

Lauren Pailing is a teenager in the eighties, becomes a Londoner in the nineties. And each time she dies, new lives begin for the people who loved her – while Lauren enters a brand new life, too.

But in each of Lauren’s lives, a man called Peter Stanning disappears. And, in each of her lives, Lauren sets out to find him.

And so it is that every ending is also a beginning. And so it is that, with each new beginning, Peter Stanning inches closer to finally being found…

Perfect for fans of Kate Atkinson and Maggie O’Farrell, The First Time Lauren Pailing Died is a book about loss, grief – and how, despite it not always feeling that way, every ending marks the start of something new.

My Thoughts:

This was such a good book. Excellent really. But it’s got me all tied up in knots about how to review it. The very essence of it is its uniqueness, but to consider that with any depth is to ruin the story for potential readers. Perhaps, before getting into what this book is, I’ll mention what it isn’t – because it could be easily interpreted as either time travel or ‘sliding doors’. It’s neither. Think quantum mechanics, and you’re heading in the right direction. However, before this scares you off, The First Time Lauren Pailing Died is not science fiction. I feel like I’m talking in riddles right now! But now that you know what it’s not, let’s talk about what it is.

Clearly, by the title and blurb, you know going into this that at some point, Lauren Pailing is going to die. More than once. She does in fact die twice. I feel I can say this without it being a spoiler. She’s also not the only character to die and then keep on living. How does this work? This is where the quantum mechanics comes in.

“Well, there is a many-worlds interpretation that helps to explain the randomness of our universe. People tend to think of this in terms of parallel universes. You can, for example, be alive in one and dead in another.”

This kind of thing really intrigues me. On one level, I find it so incredibly complicated it makes my brain hurt, yet I’m still drawn to this kind of physics. Maybe in a parallel universe I’m a physicist? Once I finished this novel, I immediately dove into some further reading on this many-worlds interpretation that is ever so briefly mentioned towards the end of the novel. I found this Stanford paper which in its introduction, concisely summed up the theory from which the novel springboards:

‘The Many-Worlds Interpretation (MWI) of quantum mechanics holds that there are many worlds which exist in parallel at the same space and time as our own. The existence of the other worlds makes it possible to remove randomness and action at a distance from quantum theory and thus from all physics.

The fundamental idea of the MWI, going back to Everett 1957, is that there are myriads of worlds in the Universe in addition to the world we are aware of. In particular, every time a quantum experiment with different possible outcomes is performed, all outcomes are obtained, each in a different world, even if we are only aware of the world with the outcome we have seen. In fact, quantum experiments take place everywhere and very often, not just in physics laboratories: even the irregular blinking of an old fluorescent bulb is a quantum experiment.’

Confused? Please don’t be. Because honestly, even though the story operates with this many-worlds interpretation at its core, the science of it is not a big part of the novel. I just really like to get answers about things like this, to dig deeper for plausible explanations. So does our protagonist, who towards the end of the novel, stumbles upon this notion as a viable explanation as to what’s been happening to her.

For as long as she has been alive, Lauren Pailing has been able to see rips in the universe. They appear to her as ribbons of light and they hover and stalk her until she peers into them. These rips are like windows to other worlds. Sometimes she sees people she knows, other times the view is unfamiliar. If she touches one of the rips, she suffers a great deal of pain and even injury. On the two occasions she dies, she wakes up in another version of herself, in a life that is at once familiar yet also strange. But we don’t leave that previous world. We still get to see what’s happening without Lauren, whilst also sticking with Lauren as she makes her way in her new life. So too, for the other character that dies and subsequently makes a jump into another world. Each world has measurable differences, some more obvious than others. It was amusing to note these differences as they popped up. But again, I want to stress, none of this story is confusing. I always knew exactly which world I was in and who was meant to be there. Such clever writing with clear intent!

There are some searing moments within this story, seeing how much of it is given over to grief. But it’s so beautifully rendered, a meticulous examination of love and loss, the evolution of a family that is forced to change by circumstances out of their control. The disappearance of Peter Stanning was the one thing that had no measurable difference between worlds. He always disappeared under mysterious circumstances on the same date and he was always never found. His impact upon Lauren’s story offered an interesting angle and her knowledge of his disappearance appeared to provide a link across worlds. Finding out what happened to Peter seemed akin to finding out what was happening to her.

I don’t want to say much more for fear of giving away the story entirely but suffice to say, this is such a uniquely involving novel, ambitious in its scope yet finite in its execution. I loved it. From the first page to the last, I was hooked. A brilliant debut that I couldn’t recommend higher if I tried. And what about that gorgeous retro cover? It’s just perfect for the story. The First Time Lauren Pailing Died is one of my top reads for 2019.

Thanks is extended to HarperCollins Publishers Australia for providing me with a copy of The First Time Lauren Pailing Died for review.

About the Author:

Alyson Rudd was born in Liverpool, raised in West Lancashire and educated at the London School of Economics. She is a sports journalist at The Times and lives in South West London. She has written two works of non-fiction. The First Time Lauren Pailing Died is her first novel.

[image error]

The First Time Lauren Pailing Died

Published by HarperCollins Publishers (HQ Fiction – GB)

Released 22nd July 2019

August 25, 2019

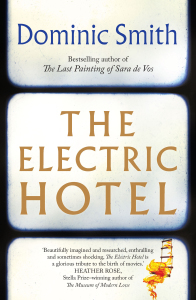

Book Review: The Electric Hotel by Dominic Smith

About the Book:

From the award-winning author of the acclaimed New York Times bestseller The Last Painting of Sara de Vos comes a luminous novel tracing the intertwined fates of a silent-film director and his muse.

Dominic Smith’s The Electric Hotel winds through the nascent days of cinema in Paris and Fort Lee, New Jersey – America’s first movie town – and on the battlefields of Belgium during World War I. A sweeping work of historical fiction, it shimmers between past and present as it tells the story of the rise and fall of a prodigious film studio and one man’s doomed obsession with all that passes in front of the viewfinder.

For nearly half a century, Claude Ballard has been living at the Hollywood Knickerbocker Hotel. A French pioneer of silent films, who started out as a concession agent for the Lumiere brothers, the inventors of cinema, Claude now spends his days foraging mushrooms in the hills of Los Angeles and taking photographs of runaways and the striplings along Sunset Boulevard. But when a film-history student comes to interview Claude about The Electric Hotel – the lost masterpiece that bankrupted him and ended the career of his muse, Sabine Montrose – the past comes surging back. In his run-down hotel suite, the ravages of the past are waiting to be excavated: celluloid fragments and reels in desperate need of restoration, and Claude’s memories of the woman who inspired and beguiled him.

My Thoughts:

‘Maybe memory is just electricity passing through us. Old voltage in the joints.’

This was a glorious novel of historical fiction. Possibly one of my favourite reads in the genre this year. In his latest novel, The Electric Hotel, Dominic Smith brings the beginnings of the silent film era to life with so much atmosphere and energy. It was a real joy to linger in the pages of this novel and learn something about a history I previously knew nothing about. I haven’t even seen a silent film before, at least not in its entirety! I have a strong urge to do so now, and I really wish it could be Smith’s invented ‘The Electric Hotel’. This fictionalised film, of which the story builds up to and then descends from, was brought to life with absolute intensity; I could picture the scenes so vividly, Smith writes that well. The film name, ‘The Electric Hotel’, is borrowed from a Spanish silent ‘trick film’ released in 1908 that was thought to be lost but has now been preserved and resides in safe keeping in the Filmoteca Espanola film archive. In his author note, Dominic Smith writes that more than seventy-five per cent of all silent films have been lost, mostly due to the instability of the medium – celluloid nitrate is both highly flammable and prone to decay. Reading this just made me all the more sad that I haven’t seen one.

When you think of how present movies are in our lives today, how frequently they are made and released, it seems strange to think of a time when they didn’t exist. The marvel of seeing silent moving images on a big screen was beautifully captured within this novel, so too, the skill and work involved in producing these images. From short moments to minutes long, we see motion picture production from its infancy and travel with the characters to the dizzying height of making the longest feature film for the era: an hour long continuous story with a plot, orchestrated score and professional sound effects, complete with outrageous stunts and a real life tiger – because a film would not be a film without the sensational. I thoroughly enjoyed seeing this film come to life from an ambitious idea to a premiere event. And you can’t even begin to imagine what was involved in making a film of this magnitude. Even the short clips that preceded it involved so much labour and meticulous planning. There was very often no room for ‘take two’. It was a case of get it right the first time because we can’t afford to do it again.

Not only is this a story about early cinema. The Electric Hotel is also a study of love and friendship, of peace and war, and using the medium of film to contextualise the state of the world for others. The novel does have a lot of the technical aspects of film and film making broken down and detailed, but I rather liked that. It gave me a real sense of knowledge which enhanced my appreciation of the efforts these early pioneers of cinema had to go to in order to achieve their means. The process of creation, production, and distribution was fascinating and I was more than a little amazed to discover that early film makers were such ‘jack of all trades’. Because we begin the novel when Claude is elderly, I found it difficult to suppress a growing sense of sadness that kept building in me throughout the story. After all, I knew where this was headed, right? Wrong. And therein lies the mastery of Dominic Smith’s storytelling. This is the third novel I’ve read by Dominic Smith and I am quite comfortable now with using the words ‘literary’ and ‘genius’ in the same sentence as his name.

‘She sometimes felt like a coil of wire, a medium for the unravelling ideas of men, for storytellers and visionaries.’

The Electric Hotel is a highly recommended read and for fans of historical fiction, it offers a guaranteed outstanding journey back through time to a fascinating era of innovation and creativity.

Thanks is extended to Allen & Unwin for providing me with a copy of The Electric Hotel for review.

About the Author:

Dominic Smith grew up in Sydney and now lives in Seattle. He is the author of five novels, including The Last Painting of Sara de Vos, an acclaimed bestseller in Australia, winning both the ABIA Literary Fiction Book of the Year and the Indie Book of the Year (Fiction) in 2017. In the US, the novel was also a New York Times (NYT) bestseller and named a NYT Book Review Editors’ Choice. Dominic has received literature fellowships from the Australia Council for the Arts and the National Endowment for the Arts. More information can be found on his website: www.dominicsmith.net

[image error]

The Electric Hotel

Published by Allen & Unwin

Released June 2019

August 24, 2019

The Week That Was…

It’s been a week of riding the waves of sickness this week, hence this weekly reflection broadcasting on Sunday instead of Friday. Everyone seems to be on the mend now, just some lingering coughs and sniffles. One lucky son escaped entirely – probably gives him further reason to advocate for bunking down in your room 24/7. No, this doesn’t mean he’s getting a fridge and microwave for his cave.

~~~~~

My book club met today. We have decided to go on a classics romp for a bit. First up is Little Women. I have already dug my retro copy out (retro, not old):

[image error]

I got this when I was 11 and secreted it around Europe with me for four months. I loved it, read it over and over for about three years, but haven’t read it since. I’m looking forward to reading this old favourite with adult eyes.

~~~~~

Speaking of Little Women, I love the look of this new adaptation!

~~~~~

Joke of the week:

[image error]~~~~~

Book of the Week:

This was a tough call because this week has seen some good books. However, this one is most present in my mind. So unique and heartfelt. I loved it.

[image error]

~~~~~

What I’m reading next:

Honestly, I haven’t decided. But there’s a few front runners.

Maybe this:

[image error]

Or perhaps this:

[image error]

But most likely this:

[image error]

~~~~~

Until next week!

August 21, 2019

Book Review: Dry Milk by Huo Yan

About the Book:

John Lee is a migrant from Beijing who has lived in Auckland for three decades. Formerly a librarian, he leads an increasingly lonely and misanthropic life, reduced to selling second-hand goods, and living in a marriage of convenience with his disabled wife, whom he treats with contempt. When he becomes infatuated with a young student who lodges in their house, and puts his life savings behind a scheme to export powdered milk to China, the dubious balance with which he has held his life together comes apart, and feelings of alienation and humiliation turn to violent obsession.

Dry Milk is a work of fiction that gives, through its unmoored narrator, a uniquely dark perspective on Antipodean culture. The story of an immigrant alienated from his new home, both its New Zealand and Chinese communities, Huo Yan’s novella is a stark portrait of social isolation, and of the experience of some of those who left China after the Cultural Revolution.

My Thoughts:

I came upon this novella, Dry Milk, via this review over at ANZ LitLovers LitBlog, which piqued my interest. In addition to Lisa’s commentary, there was something about the description and cover which drew me in, and also, I’d never before read a Chinese translation, and this was written by a young Chinese woman too, which intrigued me further. There’s a lot packed into this slim book and I was gripped from the beginning through to the end, absorbing it all within the one day. Huo Yan writes with a style that is at once easy to slip along with. We’re in the one perspective for the entire novella, but through telling dialogue and minute observational scene setting, we glean so much more about John Lee and his life.

John Lee is a migrant from Beijing, living in Auckland for the last 30 years. When the novella opens, he is celebrating 30 years to the day of living in New Zealand. A former librarian who watched over the destruction of books during the Cultural Revolution, he came to New Zealand via dubious means. He volunteered to marry a woman – she has no name, is only ever referred throughout as ‘the woman’ – who had been left mentally disabled after being exposed to gas as an infant whilst her parents committed suicide. Foisted onto relatives, when it is discovered she has distant kin in New Zealand, plans are set in motion to send her there. John Lee decides this is just the ticket: marry her and get a visa to New Zealand out of it. He doesn’t care about her disability, and he only finds out after marrying her that she has been repeatedly raped. Not to be deterred, he adds one more rape to the poor woman’s tally on their wedding night. So, thirty years on, living in Auckland, we meet John Lee. He’s a miserly old man, alternating between indifference and cruelty towards his wife. He is beyond cheap, running an antiques/second hand dealership, shopping only right before closing so he can buy his fresh food after it’s been marked down. He seasons his food with condiments fished out of the rubbish decades earlier from when he first moved into his house – they belonged to the previous owner. John Lee lives an emotionally isolated existence. He interacts with other Chinese locals, but only on the surface, never forming any true friendships. He is racist towards Maori New Zealanders and seems to have nothing but thinly veiled disdain for Westerners. He is a man adrift: unable to return to China and uneasy in New Zealand.

Two things happen to John Lee in tandem to upset the quiet order and heavy screen of privacy he has cultivated. He lets a young Chinese woman into his house as a boarder and he accepts a business proposal to export dry milk from New Zealand into China. Apparently this is a booming line of business, with Chinese consumers not trusting the quality and hygiene of local products. So, it seems like a legit deal. John Lee becomes obsessed with his new boarder, acting in particularly creepy and strange ways as time goes on. He’s not really paying attention to what’s going on right under his own nose. He fails to question coincidence and we can see the writing on the wall long before he does. It was really interesting to experience John Lee as a character. Huo Yan has created a man who is both victim and perpetrator. We are repelled by him, disgusted, horrified even; yet, he is an old man who is being swindled out of thirty years of savings. He witnessed atrocities during the Cultural Revolution and was forced into participating in acts that went against his nature. I’ve rarely felt such a contrasting force of push and pull regarding a character. I despised him, yet I wanted to warn him. As he descends further into his obsession, we have to bear witness to some shocking scenes. For me, these seemed to sharply draw into focus John Lee’s ability to dehumanise those who were around him. A legacy of his experiences during the Cultural Revolution, perhaps. As an aside, we also bear witness to an undercurrent of racism towards Chinese people in Auckland. An associate of John Lee is beaten to death by his Western son-in-law whilst attempting to defend his daughter against the violence raining down on her from her husband. There are other instances mentioned, encounters and gossip passed, that all point to an intolerance prevalent that is contrary to public image.

At the end of this novella, we see an aged Chinese woman, who has been abused and misused, dismissed and discarded, for her entire life, rise up in the defence of a younger Chinese woman. The power of this ending moved me greatly, particularly taken within the context of this novella being written by a young Chinese woman, a member of the generation once removed from the Cultural Revolution, born during the decades of China’s one child policy – that which prized boys and discarded girls. A very powerful ending, indeed.

About the Author:

Born in 1987, Huo Yan is a writer of novels, short stories, screenplays and criticism. She began writing at the age of 13 and won her first literary prize at the age of 14. She is the author of eight books, and her work has been published in magazines including Harvest, October and Beijing Literature. She holds a Doctorate of Contemporary Literature. In 2013, she held the Rewi Alley Fellowship at the Michael King Writers Centre in Auckland, and wrote Dry Milk. She lives in Beijing.

[image error]

Dry Milk

Published by Giramondo Publishing

Released July 1st 2019 (first published 2013)

August 20, 2019

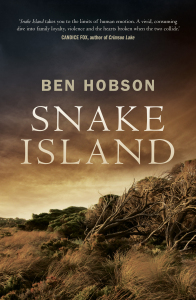

Book Review: Snake Island by Ben Hobson

About the Book:

Vernon and Penelope Moore never want to see their son Caleb again. Not after he hit his wife and ended up in gaol. A lifetime of careful parental love wiped out in a moment.

But when retired teacher Vernon hears that Caleb is being regularly visited and savagely bashed by a local criminal as the police stand by, he knows he has to act. What has his life been as a father if he turns his back on his son in his hour of desperate need? He realises with shame that he has failed Caleb. But no longer.

The father of the man bashing Caleb is head of a violent crime family. The town lives in fear of him but Vernon is determined to fix things in a civilised way, father to father. If he shows respect, he reasons, it will be reciprocated. But how wrong he is.

And what hell has he brought down on his family?

Reading like a morality tale Western but in a starkly beautiful Australian setting, Snake Island is a propulsive literary thriller written with great clarity and power. It will take you to the edge and keep you there long after the final page is turned.

My Thoughts:

Snake Island is a story about consequences. It begins with Brendan Cahill – the eldest son within a local crime family – acting upon an impulse of retribution. It ends with him reaping what he’s sown.

‘All the choices he’d made had led him here. An end he’d surely never wanted. And yet here he was.’

Like a Shakespearean tragedy that’s been injected with wild western hellfire, Snake Island is unashamedly violent, its characters setting themselves onto a path of ruin from which there is no return. Hobson digs deep into the psyche of his characters, exposing their weaknesses, their fears, and their egos. He takes them to places that they didn’t even know they would go, shocking you, the reader, all the more as you bear witness to their descent.

‘What she said was true. He’d never led the boy astray, but he’d never led him anywhere. And in that lack the violence had been born.’

Hobson’s writing is eloquent, his examination of Australian masculinity asking what it is to be a father, a husband, a son, a brother, and a friend. Snake Island is a gripping read, at times unsettling, pushing the limits of mortality and testing the reader over and over. A very different novel to his first – To Become A Whale – but equally as powerful. Highly recommended reading – and wow! This would be an incredible story up on the big screen.

‘This man’s loss had been his salvation.’

Thanks is extended to Allen & Unwin for providing me with a copy of Snake Island for review.

About the Author:

Ben Hobson lives in Brisbane and is entirely keen on his wife, Lena, and their two small boys, Charlie and Henry. He currently teaches English and Music at Bribie Island State High School. In 2014 his novella, If the Saddle Breaks My Spine, was shortlisted for the Viva La Novella prize, run by Seizureonline. To Become a Whale, his first novel, was published in 2017.

[image error]

Snake Island

Published by Allen & Unwin

Released August 2019

August 18, 2019

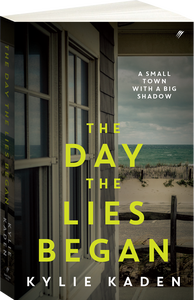

Book Review: The Day the Lies Began by Kylie Kaden

About the Book:

‘It seemed simple at first – folding one lie over the next. She had become expert at feathering over the cracks to ensure her life appeared the same. But inside, it didn’t feel fixed.’

It happened the day of the Moon Festival. It could have been left behind, they all could have moved on with their lives. But secrets have a habit of rising to the surface, especially in small towns.

Two couples, four ironclad friendships, the perfect coastal holiday town. With salt-stung houses perched like lifeguards overlooking the shore, Lago Point is the scene of postcards, not crime scenes. Wife and mother Abbi, town cop Blake, schoolteacher Hannah, and local doctor Will are caught in their own tangled webs of deceit.

When the truth washes in to their beachside community, so do the judgements: victim, or vigilante, who will forgive, who will betray? Not all relationships survive. Nor do all residents.

My Thoughts:

‘Killers look exactly like their victims.’

Well. If ever there was a cautionary tale that screamed: CALL THE POLICE, then this is it. Domestic noir, that new sub-genre born out of the Gone Girl phenomenon, is a bit of a tricky beast for me. Overall I found this novel, The Day the Lies Began, a compelling read, one of the better ones within this genre for me. Once I got past the first 25% of not knowing at all what was going on, I was pretty much hooked and unable to put it down. But that kind of characterises this genre, doesn’t it? You spend much of the first half of the novel in this zone of not having a clue about what’s happening, the main characters alluding to ‘the event’ without actually mentioning it. I think this is my main problem with this type of crime fiction: it gets old very quick. I don’t enjoy the dangle, trying to work out the unsaid. But fortunately, this doesn’t go on for too long in this novel, so I was able to really settle in for a good story without being too frustrated by the pacing. But seriously, people really can be their own worst enemies. Jumping to conclusions, covering stuff up, heaping lies upon lies. Just call the police. Dial 000. Anything else is just not going to work out for you.

‘She convinced herself that these acts of duplicity weren’t betrayal at all, but instead were well intended, planned measures to protect their family. Impulsive, misguided, perhaps, but ultimately acts of love.’

There’s plenty of twists throughout this story and for the most part, realisation arrived with me at the right time. Kylie definitely doesn’t show her hand too early, but, and perhaps more importantly, nor does she disclose her twists too late, which is often the reason why stories within this genre lack credibility. In essence, this is a very sad story, and it’s also one that is particularly pertinent to our current times. There were however some things about it that made me angry, particularly around the notion of people covering stuff up about the people in their family. I don’t want to spoil any part of the mystery, so I’ll need to be vague, but honestly, if you know someone in your family has an abhorrent interest that is also a crime, but you just sit on it, apologising after the fact when it all goes wrong just doesn’t cut it. I think you’re complicit. The idea that there are people out there who know these things but don’t ever really disclose them disturbs me. I was also bothered by the angle presented that we should be sympathetic to certain types of perpetrators, that they may not ‘choose’ to be the way they are, but rather, it’s an ‘illness’ that compels them to act the way they do. This doesn’t fly with me. Ever. I think maybe you have to be a certain type of person for that level of understanding and I’m definitely not one of them. I kept wondering why everyone was concerned the creep was dead. I guess in this sort of situation, for me, any good a person has ever done is nullified by their depravity. I make no apologies for that view.

‘He thought about their relationship trajectory, more aware now of her flaws. The power had always been with her, from the day he’d arrived at her home as the latest in a production line of troubled kids. She’d shown him the ropes, and held them ever since.’

Now, I’ve often encountered novels where I don’t like the main character but still really like the story. It’s lucky these two don’t go hand in hand for me, because I really disliked both Hannah and Abbi, the two women at the helm of this story. I think that by the end, I was supposed to feel sympathy for Hannah. I didn’t. If anything, she just got on my nerves even more. As to Abbi, she was a first class manipulator and I am never tolerant of characters who ‘can’t adult’. I mean, really? That’s not a thing. Grow up. But, these people do exist, and we all have to suffer them. Just as I think I was supposed to feel sympathy for Hannah, I’m pretty sure I was supposed to feel empathy for Abbi, but again, nope. They were just two very big pains that never eased. Abbi’s motivations for her actions were fundamentally selfish, born out of a need to have someone there for her to make all of life’s decisions and bear all of the responsibility for her actions (remember the no adulting thing?), while Hannah was just a whiny ‘poor me’ selfish cow who kept claiming to have been through a lot but really didn’t go through much at all. I hated both of them and felt really sorry for both Will and Blake for having to put up with them. Abbi also did a lot of really trashy things to Blake that fully crossed the line of brother and sister. This is why I don’t read much of this genre. Honestly, the women are mostly the pits. Both of them realise the error of their ways far too late and the idea that either of them could break the habits of a lifetime was pretty thin on the ground to me. But if anything, hating both of these women kind of increased my enjoyment of the novel, if that makes any sense. It’s like I got a macabre sense of enjoyment out of seeing just what stupid thing each of them would do next!

‘This farce was all on her. From the start, she’d directed this play. She’d cast the roles, and wrote the script. A wave of self-loathing pummelled her, before panic overcame her.’

The Day the Lies Began is a gripping story, with twists and turns that will keep you guessing and plenty of characters to love and hate. It would make for a good television series. Kylie Kaden’s first foray into domestic noir is most definitely a successful one. I highly recommend this to fans of the genre.

Thanks is extended to Pantera Press via NetGalley for providing me with a copy of The Day the Lies Began for review.

About the Author:

Kylie Kaden was raised in Queensland and is the author of two previous novels: Losing Kate and Missing You. She holds an honours degree in Psychology and works as a freelance writer and columnist. Her new book, The Day the Lies Began is a domestic noir-thriller that explores one of her favourite themes: why good people do bad things.

[image error]

The Day the Lies Began

Published by Pantera Press

Released on 19th August 2019

August 17, 2019

The Classics Eight: Rebecca by Daphne du Maurier for #rebeccabuddyread

About the Book:

Last night I dreamt I went to Manderley again . . .

Working as a lady’s companion, the heroine of Rebecca learns her place. Life begins to look very bleak until, on a trip to the South of France, she meets Maxim de Winter, a handsome widower whose sudden proposal of marriage takes her by surprise. She accepts, but whisked from glamorous Monte Carlo to the ominous and brooding Manderley, the new Mrs de Winter finds Max a changed man. And the memory of his dead wife Rebecca is forever kept alive by the forbidding Mrs Danvers.

Not since Jane Eyre has a heroine faced such difficulty with the Other Woman.

An international best-seller that has never gone out of print, Rebecca is the haunting story of a young girl consumed by love and the struggle to find her identity.

[image error]

My Thoughts:

Rebecca is one of those classics I have heard mentioned by book lovers time and time again, yet I’d never made the time to actually read it for myself. I even bought a beautiful Folio Society edition as a means of prompting myself to get to it, but it still took me a year on from that purchase to open the cover. In one of those chats where one thing leads to another, Tracey Allen of Carpe Librum blog and I decided to read Rebecca as a buddy read. We threw the idea out there to others and from that point on, #rebeccabuddyread was born. I highly recommend reading a classic as a group – it’s a lot of fun and keeps you present within the story for the duration on account of all of the back and forth commentary. I loved Rebecca, with its dreamy prose and atmospheric presence. This is a classic that I highly recommend and can see myself returning to over time. Even though we had set aside two weeks for the buddy read, I raced through it in four days – I just couldn’t stop reading it! It certainly fulfils the description of timeless classic and I can see why it hasn’t ever been out of print.

For something a little bit different, instead of writing a review, I give you my impression of Rebecca through my favourite quotes.

The illustrations are from my own edition of Rebecca.

[image error]

Moonlight can play odd tricks upon the fancy, even upon a dreamer’s fancy. As I stood there, hushed and still, I could swear that the house was not an empty shell but lived and breathed as it had lived before.

– Chapter 1.

We can never go back again, that much is certain.

– Chapter 2.

He belonged to a walled city of the fifteenth century, a city of narrow, cobbled streets, and thin spires, where the inhabitants wore pointed shoes and worsted hose. His face was arresting, sensitive, medieval in some strange inexplicable way, and I was reminded of a portrait seen in a gallery, I had forgotten where, of a certain Gentleman Unknown.

– Chapter 3.

[image error]

That girl who, tortured by shyness, would stand outside the sitting-room door twisting a handkerchief in her hands, while from within came that babble of confused chatter so unnerving to the intruder – she had gone with the wind that afternoon. She was a poor creature, and I thought of her with scorn if I considered her at all.

– Chapter 4.

She had beauty that endured, and a smile that was not forgotten. Somewhere her voice still lingered, and the memory of her words. There were places she had visited, and things that she had touched. Perhaps in cupboards there were clothes that she had worn, with the scent about them still.

– Chapter 5.

This has been ours, however brief the time. Though two nights only have been spent beneath a roof, yet we leave something of ourselves behind. Nothing material, not a hair-pin on a dressing-table, not an empty bottle of Aspirin tablets, not a handkerchief beneath a pillow, but something indefinable, a moment of our lives, a thought, a mood.

– Chapter 6.

Unconsciously, I shivered as though someone had opened the door behind me and let a draught into the room. I was sitting in Rebecca’s chair, I was leaning against Rebecca’s cushion, and the dog had come to me and laid his head upon my knee because that had been his custom, and he remembered, in the past, she had given sugar to him there.

– Chapter 7.

It seemed strange to me that Maxim, who in Italy and France had eaten a croissant and fruit only, and drunk a cup of coffee, should sit down to this breakfast at home, enough for a dozen people, day after day probably, year after year, seeing nothing ridiculous about it, nothing wasteful.

– Chapter 8.

You could hear the sea from here. You might imagine, in the winter, it would creep up on to those green lawns and threaten the house itself, for even now, because of the high wind, there was a mist upon the window-glass, as though someone had breathed upon it. A mist salt-laden, borne upwards from the sea.

– Chapter 9.

[image error]

The sky, now overcast and sullen, so changed from the early afternoon, and the steady insistent rain could not disturb the soft quietude of the valley; the rain and the rivulet mingled with one another, and the liquid note of the black bird fell upon the damp air in harmony with them both. I brushed the dripping heads of azaleas as I passed, so close they grew together, bordering the path. Little drops of water fell on to my hands from the soaked petals. There were petals at my feet too, brown and sodden, bearing their scent upon them still, and a richer, older scent as well, the smell of deep moss and bitter earth, the stems of bracken, and the twisted buried roots of trees.

– Chapter 10.

I could not believe that I had said the name at last. I waited, wondering what would happen. I had said the name. I had said the word Rebecca aloud. It was a tremendous relief. It was as though I had taken a purge and rid myself of an intolerable pain. Rebecca. I had said it aloud.

– Chapter 11.

Little things, meaningless and stupid in themselves, but they were there for me to see, for me to hear, for me to feel. Dear God, I did not want to think about Rebecca. I wanted to be happy, to make Maxim happy, and I wanted us to be together. There was no other wish in my heart but that. I could not help it if she came to me in thoughts, in dreams. I could not help it if I felt like a guest in Manderley, my home, walking where she had trodden, resting where she had lain. I was like a guest, biding my time, waiting for the return of the hostess. Little sentences, little reproofs reminding me every hour, every day.

– Chapter 12.

If Maxim had been there I should not be lying as I was now, chewing a piece of grass, my eyes shut. I should have been watching him, watching his eyes, his expression. Wondering if he liked it, if he was bored. Wondering what he was thinking. Now I could relax, none of these things mattered. Maxim was in London. How lovely it was to be alone again. No, I did not mean that. It was disloyal, wicked. It was not what I meant. Maxim was my life and my world.

– Chapter 13.

[image error]

Then I heard a step behind me and turning round I saw Mrs Danvers. I shall never forget the expression on her face. Triumphant, gloating, excited in a strange unhealthy way. I felt very frightened.

– Chapter 14.

I thought how little we know about the feelings of old people. Children we understand, their fears and hopes and make-believe. I was a child yesterday. I had not forgotten. But Maxim’s grandmother, sitting there in her shawl with her poor blind eyes, what did she feel, what was she thinking? Did she know that Beatrice was yawning and glancing at her watch? Did she guess that we had come to visit her because we felt it right, it was a duty, so that when she got home afterwards Beatrice would be able to say, ‘Well, that clears my conscience for three months’? Did she ever think about Manderley? Did she remember sitting at the dining-room table, where I sat? Did she too have tea under the chestnut-tree? Or was it all forgotten and laid aside, and was there nothing left behind that calm, pale face of hers but little aches and little strange discomforts, a blurred thankfulness when the sun shone, a tremor when the wind blew cold?

– Chapter 15.

I wished he would not always treat me as a child, rather spoilt, rather irresponsible, someone to be petted from time to time when the mood came upon him but more often forgotten, more often patted on the shoulder and told to run away and play. I wished something would happen to make me look wiser, more mature. Was it always going to be like this? He away ahead of me, with his own moods that I did not share, his secret troubles that I did not know? Would we never be together, he a man and I a woman, standing shoulder to shoulder, hand in hand, with no gulf between us? I did not want to be a child. I wanted to be his wife, his mother. I wanted to be old.

– Chapter 16.

He never spoke to me. He never touched me. We stood beside one another, the host and the hostess, and we were not together. I watched his courtesy to his guests. He flung a word to one, a jest to another, a smile to a third, a call over his shoulder to a fourth, and no one but myself could know that every utterance he made, every movement, was automatic and the work of a machine. We were like two performers in a play, but we were divided, we were not acting with one another. We had to endure it alone, we had to put up this show, this miserable, sham performance, for the sake of all these people I did not know and did not want to see again.

– Chapter 17.

[image error]

She was in the house still, as Mrs Danvers had said; she was in that room in the west wing, she was in the library, in the morning-room, in the gallery above the hall. Even in the little flower-room, where her mackintosh still hung. And in the garden, and in the woods, and down in the stone cottage on the beach. Her footsteps sounded in the corridors, her scent lingered on the stairs. The servants obeyed her orders still, the food we ate was the food she liked. Her favourite flowers filled the rooms. Her clothes were in the wardrobes in her room, her brushes were on the table, her shoes beneath the chair, her nightdress on her bed. Rebecca was still mistress of Manderley. Rebecca was still Mrs de Winter. I had no business here at all. I had come blundering like a poor fool on ground that was preserved.

– Chapter 18.

When people suffer a great shock, like death, or the loss of a limb, I believe they don’t feel it just at first. If your hand is taken from you you don’t know, for a few minutes, that your hand is gone. You go on feeling the fingers. You stretch and beat them on the air, one by one, and all the time there is nothing there, no hand, no fingers. I knelt there by Maxim’s side, my body against his body, my hands upon his shoulders, and I was aware of no feeling at all, no pain and no fear, there was no horror in my heart.

– Chapter 20.

But something new had come upon me that had not been before. My heart, for all its anxiety and doubt, was light and free. I knew then that I was no longer afraid of Rebecca. I did not hate her any more. Now that I knew her to have been evil and vicious and rotten I did not hate her any more. She could not hurt me. I could go to the morning-room and sit down at her desk and touch her pen and look at her writing on the pigeon-holes, and I should not mind. I could go to her room in the west wing, stand by the window even as I had done this morning, and I should not be afraid. Rebecca’s power had dissolved into the air, like the mist had done. She would never haunt me again. She would never stand behind me on the stairs, sit beside me in the dining-room, lean down from the gallery and watch me standing in the hall. Maxim had never loved her. I did not hate her any more.

– Chapter 21

It was ours, inviolate, a fraction of time suspended between two seconds.

– Chapter 25.

The road to Manderley lay ahead. There was no moon. The sky above our heads was inky black. But the sky on the horizon was not dark at all. It was shot with crimson, like a splash of blood. And the ashes blew towards us with the salt wind from the sea.

– Chapter 27.

About the Author:

Daphne du Maurier (1907-89) was born in London, educated at home and in Paris, and lived much of her life in her beloved Cornwall, the setting for many of her novels. Most of her novels have been bestsellers and many have been made into films. She is considered one of the most accomplished novelists of the twentieth century.

August 16, 2019

#BookBingo – Round 17

I have to take what I can get with this category as memoirs really aren’t my cup of tea! Reading them puts the ‘challenge’ into reading challenge.

Memoir about a non-famous person:

Diving into Glass by Caro Llewellyn

[image error]

Fans of memoirs will think this is an incredible book; in many ways it is. Caro Llewellyn certainly writes well, and for the most part, there is a lack of the type of self-indulgence ever present in memoirs. She accepts responsibility for her own actions, she doesn’t demonise her parents, nor does she wallow – all factors I appreciated. I just really wish there had been more of her MS journey through to the present day and less of everything else.

For 2019, I’m teaming up with Mrs B’s Book Reviews and The Book Muse for an even bigger, and more challenging book bingo. We’d love to have you join us. Every second Saturday throughout 2019, we’ll post our latest round. We invite you to join in at any stage, just pop the link to your bingo posts into the comments section of our bingo posts each fortnight so we can visit you. If you’re not a blogger, feel free to just write your book titles and thoughts on the books into the comments section each fortnight, and tag us on social media if you are playing along that way.

[image error]