Theresa Smith's Blog, page 92

October 16, 2019

#TBT: What I was reading this time last year…

Winding back just a little bit this time, only to a year ago.

[image error]

I was having a very productive week, reading wise, this time last year!

All good books, each of them. Have you read any of these? Thoughts on them?

October 15, 2019

Book Review: Invented Lives by Andrea Goldsmith

About the Book:

Knowing what you want is hard. Accepting what is possible is harder still.

It is the mid-1980s. In Australia, stay-at-home wives jostle with want-it-all feminists, while AIDS threatens the sexual freedom of everyone. On the other side of the world, the Soviet bloc is in turmoil.

Mikhail Gorbachev has been in power for a year when twenty-four-year-old book illustrator Galina Kogan leaves Leningrad — forbidden ever to return. As a Jew, she’s inherited several generations worth of Russia’s chronic anti-Semitism. As a Soviet citizen, she is unprepared for Australia and its easy-going ways.

Once settled in Melbourne, Galina is befriended by Sylvie and Leonard Morrow, and their adult son, Andrew. The Morrow marriage of thirty years balances on secrets. Leonard is a man with conflicted desires and passions, while Sylvie chafes against the confines of domestic life. Their son, Andrew, a successful mosaicist, is a deeply shy man. He is content with his life and work — until he finds himself increasingly drawn to Galina.

While Galina grapples with the tumultuous demands that come with being an immigrant in Australia, her presence disrupts the lives of each of the Morrows. No one is left unchanged.

Invented Lives tells a story of exile: exile from country, exile at home, and exile from one’s true self.

It is also a story about love.

My Thoughts:

‘Yet she was all too aware that she, a Russian Jew, was formed by Russia – the Russia of her lifetime and the earlier Russia of her mother and grandparents. She might well be surrounded by freedom and delight, but she carried her past with her. It was as if she were inhabiting two lives simultaneously, and much of the time they were not an easy fit.’

What a novel. I should warn you up front that I’ve used numerous quotes in this review. I just feel as though there are so many profound passages within this story, and who better to demonstrate the beauty of its essence than the author herself?

‘She had thought she would assimilate more quickly if she kept herself separate from other Russian émigrés; now she wondered if she would ever fully assimilate, and, more especially, whether she could tolerate all the losses if she did. What seemed distressingly clear was that her choices – a type of self-annihilation, it now occurred to her – had made her exile total and absolute. She needed other émigrés to connect her with home.’

Invented Lives is a novel about migration, but it’s also about so much more. Novels about the USSR and life ‘behind the iron curtain’ interest me greatly – which I pointed out in my recent review of The Secrets We Kept (see my review here). We learn much about life within Soviet Russia from Galina’s story, along with so much about Russia’s tumultuous history. It was all so fascinating, and horrifying, and so desperately other to anything I have ever lived. We, who were born in Australia and have lived here all of our lives, are so very lucky. We really probably don’t have any idea just how much, and that’s just further evidence of our luck.

‘There were, she was discovering, so many possible pairings in the existence of the émigré. While gathered with this family in their home, Galina was soaking up their warmth and closeness while simultaneously being aware of what she was being forced to live without. So many impossible pairings. Even émigré and immigrant. To the Soviets she was the former, to the Australians the latter, but to herself she was both. Always this double life: an old Soviet and a new Australian.’

My grandparents were migrants, but from Belgium, not a communist European country. Growing up in a bilingual household, my life was a blend of Australian and Belgian culture. But even witnessing the different things my grandparents struggled with, it’s still so far removed from what Galina’s first experiences within Australia were like. To go from East to West is so monumental: from oppression to freedom. I can’t even begin to express how much I appreciate the authenticity of experience articulated within the pages of this novel. There were so many things that Galina had to face and grapple with that I would never have ever contemplated. The choice available, and being overwhelmed by so many options for everything, really stood out for me. The longing for Russian experiences but knowing that Russia itself was a place no longer for you.

‘And that was the crucial difference. She didn’t have a choice. When she received her exit visa to leave the Soviet Union, she forfeited any right of return. Ever. But there was something else. Imprinted in the semantics of exile was a desire to return, and the assumption that when things had improved, you’d be permitted to return.

Perhaps you stopped being an exile when you no longer wanted to return home because you were home.’

Alongside Galina’s story is that of Andrew and his parents, Leonard and Sylvie. I found Leonard to be a selfish character, but fairly typical of his generation. It was Sylvie who I really championed for and appreciated. Through Galina’s observations of this family, we were privy to a glance back through time, a look at what Australia was like in the mid to late 1980s. It was nostalgic and a little bit cringe worthy in the way that looking back can be, but also kind of quaint. I’m finding that I’m getting a lot of enjoyment of late out of reading books set in the 1980s. Far enough removed to no longer be embarrassing but not that long ago that I can’t remember. Anyway, Leonard and Sylvie provided plenty of fodder to turn over and ponder on. I really did enjoy watching Sylvie’s metamorphosis unfolding in tandem with Leonard’s destabilisation.

‘Given enough time, she can deal with disgust and betrayal, but more difficult is her sense of having been short-changed – by Leonard, certainly, but more so by their marriage. Their long marriage has allowed him freedoms denied to her; their long marriage has been far more generous to him than it has been to her.’

I also immensely enjoyed Sylvie’s letter project. There used to be a time when fat envelopes graced my letterbox frequently, but now they’re few and far between – for everyone, I would think. I still have letters that were written to me by my brother from before he died, when we were in our twenties. This passage; it pierced me.

‘And how much more precious does a letter become – not to me, the collector, but the original recipient – when the writer of the letter has died. Think of it: for the wife who lives on after her husband, the man whose brother has passed away, the woman who’s lost her best friend, death does not alter their letters. I think that’s profound.

Death, which changes almost everything, leaves letters untouched.’

There is a focus on art within this novel that touched me deeply. Each of the main characters were artists: Galina was an illustrator, Andrew a mosaic artist, Leonard had been a poet in his younger days, and Sylvie was a person who embraced many types of creativity. Art was a vivid presence to each of them by differing degrees. I have always been an advocate for the importance of the arts, so this aspect of the novel reached right into me. I just have to share this passage and it’s a fitting way to bring this review to a close too. You will hopefully see, through these words, just how splendid this novel is.

‘Every Russian knows that art saves lives; poetry, music, novels, paintings, all these have saved lives. A million people died in the siege of Leningrad, but the number would have been greater if not for poetry. Throughout those nine hundred desperate days, so her mother had told her, Olga Berggolt’s radio broadcasts encouraged with inspiring words and stories, but most of all it was her poetry that sustained the people.

And another story from the siege: a young woman, an artist, starving like everyone else, who made herself paint through a long freezing night, knowing that if she didn’t she would succumb to the overwhelming desire to curl up on the floor and let death take her.

This meticulous ability to mute pain – that’s what art can do, and Andrew was denying it. Andrew with his comfortable, fear-free life didn’t know what he was talking about.

Then there was Shostakovich’s life-saving Seventh Symphony first heard in Leningrad during the seige. Andrew probably knew nothing of the great Dimitri Dmitriyevich. The Germans tried to stop the performance, they wanted to silence so powerful a weapon. But they failed and the performance went ahead; recorded and played over the wireless, it energised hundreds of thousands of Leningraders. The Nazis knew what Andrew was now denying: art saves life, art gives life. And the reams of literature circulated in samizdat in the post-Stalinist years – people risked their life for this art because they knew it would make them stronger.’

And at the end of this chapter, about Andrew clumsily denying that art saves lives and Galina staunchly refuting this, Andrew himself disproves his own words:

‘He finished just before dawn. He had created a stormy seascape at sunset with a lighthouse. It was unlike anything he had ever done before. He made himself fresh coffee and went up to the roof. It was a vibrant dawn; the sky was lit with the colours of his painting. He watched the sun rise. He had survived the night.’

I love this so much. Enough said. Invented Lives. Just read it and weep at the beauty of it.

Thanks is extended to Scribe for providing me with a copy of Invented Lives for review.

About the Author:

Andrea Goldsmith originally trained as a speech pathologist and was a pioneer in the development of communication aids for people unable to speak. Her first novel, Gracious Living, was published in 1989. This was followed by Modern Interiors, Facing the Music, Under the Knife, and The Prosperous Thief, which was shortlisted for the 2003 Miles Franklin Literary Award. Reunion was published in 2009, and The Memory Trap was awarded the 2015 Melbourne Prize. Her literary essays have appeared in Meanjin, Australian Book Review, Best Australian Essays, and numerous anthologies. She has mentored many emerging writers.

[image error]

Invented Lives

Published by Scribe

Released April 2019

Book Review: The Giver of Stars by Jojo Moyes

About the Book:

Inspired by a remarkable true story, the unforgettable journey of five extraordinary women living in extraordinary and perilous times.

Alice Wright has travelled halfway across the world to escape her stifling life in England. Handsome American businessman Bennett Van Cleve represents a fresh start. But she soon realises that swapping the twitching curtains of suburbia for newlywed life in the wild mountains of Kentucky isn’t the answer to her prayers. But maybe meeting Margery O’Hara is. The heart and backbone of the small community of Salt Lick, a woman who isn’t afraid of anything or anyone, Margery is on a mission.

Enlisting Alice, along with three other women, all from very different backgrounds, to join her, the band of unlikely sisters battle the elements and unforgiving terrain – as well as brave all manner of dangers and social disapproval – to ride hundreds of miles a week to deliver books to isolated families. Transforming the lives of so many is all the impetus they need to take such risks.

And for Alice, her new job and blossoming friendships become an unexpected lifeline, providing her with the courage she needs to make some tough decisions about her marriage. Then a body is found in the mountains, rocking the close-knit community and tearing the women apart as one of them becomes the prime suspect. Can they pull together to overcome their greatest challenge yet?

A love letter to the power of books and literature and their ability to bring us together and deliver the truth, as well as a tribute to female friendship, The Giver of Stars is the book that Jojo Moyes was born to write.

My Thoughts:

Recent releases from Jojo Moyes have focused on the Me Before You trilogy, but she has written historical fiction in the past, of which I was a fan, so it’s nice to see her return to this territory. I enjoyed this novel immensely, both the topic and history it covered along with the characters. Focusing on the WPA Horseback Librarian programme set up in the 1930s by Eleanor Roosevelt to improve literacy within Kentucky, The Giver Of Stars is a book about books – a reader’s dream.

‘The WPA’s Horseback Librarian programme ran from 1935 to 1943. At its height it brought books to more than a hundred thousand rural inhabitants. No programme like it has ever been set up since.

Eastern Kentucky remains one of the poorest – and most beautiful – places in the United States.’ – Author’s Postscript

This is not the first novel I’ve read about the Kentucky packhorse librarians. Earlier this year, I read The Book Woman of Troublesome Creek (see my review here), which was a deeply affecting read. Fortunately, there were more differences than similarities between these two excellent novels, so I was able to avoid falling into a comparison trap.

‘The Packhorse Library had become, in the months of its existence, a symbol of many things, and a focus for others, some controversial and some that would provoke unease in certain people however long it stayed around.’

Jojo Moyes has done a splendid job with capturing the historical tone of her setting along with tapping into the social fabric of Kentucky life in the 1930s. The poverty, the violence, the extreme temperatures and terrain. But also the community spirit balanced against the community prejudices. She examines the environmental, economical, and community effects of unregulated coal mining throughout the mountains, detailing the impacts this has had on compounding poverty. Above all though, The Giver Of Stars is a two-fold story about women: how they can band together over a common cause, forming strong bonds of enduring friendship, going above and beyond for each other and what they believe in; and on a more sombre note, how much they lack agency over their own lives.

‘You know the worst thing about a man hitting you?’ Margery said finally. ‘Ain’t the hurt. It’s that in that instant you realise the truth of what it is to be a woman. That it don’t matter how smart you are, how much better at arguing, how much better than them, period. It’s when you realise they can always just shut you up with a fist. Just like that.’

There’s not a bit about this novel that I didn’t like. It’s written with a spark of humour and a river of true feeling. The beauty of the Kentucky wilderness shines through, the author’s admiration for the place very much in evidence. The history conveyed is well balanced with the more dramatic aspects of the storyline, making this novel a page turner in every sense of the expression. Highly recommended reading. I heard a rumour that this story might be headed to the movies – fingers crossed this is true. I’ll look forward to that!

About the Author:

Jojo Moyes was raised in London. She writes for the Daily Telegraph, Daily Mail, Red and Woman & Home. She’s married to Charles Arthur, technology editor of The Guardian. They live with their three children on a farm in Essex, England.

[image error]

The Giver of Stars

Published by Penguin Random House Australia

Released 1st Oct 2019

October 13, 2019

Book Review: City of Girls by Elizabeth Gilbert

About the Book:

It is the summer of 1940. Nineteen-year-old Vivian Morris arrives in New York with her suitcase and sewing machine, exiled by her despairing parents. Although her quicksilver talents with a needle and commitment to mastering the perfect hair roll have been deemed insufficient for her to pass into her sophomore year of Vassar, she soon finds gainful employment as the self-appointed seamstress at the Lily Playhouse, her unconventional Aunt Peg’s charmingly disreputable Manhattan revue theatre. There, Vivian quickly becomes the toast of the showgirls, transforming the trash and tinsel only fit for the cheap seats into creations for goddesses.

Exile in New York is no exile at all: here in this strange wartime city of girls, Vivian and her girlfriends mean to drink the heady highball of life itself to the last drop. And when the legendary English actress Edna Watson comes to the Lily to star in the company’s most ambitious show ever, Vivian is entranced by the magic that follows in her wake. But there are hard lessons to be learned, and bitterly regrettable mistakes to be made. Vivian learns that to live the life she wants, she must live many lives, ceaselessly and ingeniously making them new.

My Thoughts:

It is so wonderful to have a novel by Elizabeth Gilbert again. While I enjoy reading whatever she writes, she does have that special skill of weaving magic through a story. City of Girls begins with its protagonist, Vivian, elderly, receiving a letter from a woman named Angela, who is writing to inform Vivian of the death of her mother. She ends the letter as such:

‘Vivian…given that my mother has passed away, I wonder if you might now feel comfortable telling me what you were to my father?’

And so begins City of Girls, in which the novel itself is Vivian’s response to Angela’s question.

We are taken back to New York City in the 1940s, guided by Vivian, who was an incredibly naive, and if I’m completely honest, pretty stupid, nineteen year old. But given the hindsight narration of the story, Vivian herself fully acknowledges this, which makes what could have been exasperating into something more amusing. The story is filled with risqué behaviour and debauchery, but as you might expect from Elizabeth Gilbert, important themes lie beneath all of this frivolity, for City of Girls is a story about women – their relationships, their choices, their sexuality, and the ways in which society has, in every decade, demanded some form of subservience from them.

‘This is the image that I think of, Angela, whenever I hear people talk about how the past was a more innocent time. I think of fourteen-year-old Maria Theresa Beneventi, fresh off her first abortion, with no roof over her head, masturbating the owner of an industrial bakery so that she could keep her job and have somewhere safe to sleep. Yes, folks – those were the days.’

~~~~~

‘At the time, reading that article made my conscience feel like a rotting little rowboat sinking into a pond of mud. But thinking about it today, I have to say that it enrages me. Arthur Watson had completely gotten away with his misdeeds and lies. Celia had been banished by Peg, and I had been banished by Edna – but Arthur had been allowed to carry on with his lovely life and his lovely wife, as though nothing had ever happened.

The dirty little whores had been disposed of; the man was allowed to remain.

Of course, I didn’t recognise the hypocrisy back then.

But Lord, I recognise it now.’

Vivian’s honesty and humour makes this a refreshing read. It’s expansive and intricate in detail. We get such a recreated sense of New York City from the 1940s through to the 1970s. The tapestry of history is just sublime. The people, the lifestyles, the changing face of the city pre-war and post-war. It’s like a goldmine of social history and I loved every bit of it. And as to Vivian herself, well, I adored her. Even when she was entirely without sense, but especially once she had come into her own. Vivian’s profession as a seamstress was of particular interest to me. My grandmother was a seamstress, out of the same era, and I grew up around fabric, loose threads, pin cushions, and the dust of marking chalk, so I always appreciate a protagonist who makes their living creating clothes. Vivian was one of those characters who, to my mind, was perfectly imperfect, unapologetic about who she was, but only because she’d been through the wringer to get there.

‘After a certain age, we are all walking around this world in bodies made of secrets and shame and sorrow and old, unhealed injuries. Our hearts grow sore and misshapen around all this pain – yet somehow, still, we carry on.’

It seems at times as though Vivian’s response to Angela is a long time coming, but when she gets there, you see why Angela needed to know everything. Sometimes in life, we have no idea of the impact we have upon other people, even after the most fleeting contact. Elizabeth Gilbert shows us this, through Vivian’s relationship with Angela’s father. Their relationship was not what I had expected and it was profoundly more meaningful than I could have ever envisaged.

‘It was on the rooftop of our little bridal boutique that I learned this truth: when women are gathered together with no men around, they don’t have to be anything in particular; they can just be.’

Needless to say, I loved City of Girls. It more than lived up to its fiction predecessor, The Signature of all Things. Elizabeth Gilbert might not give us fiction very often, but when she does, it’s more than worth the wait.

About the Author:

Elizabeth Gilbert is the Number One New York Times bestselling author of Eat Pray Love and several other internationally bestselling books of fiction and non-fiction. Her story collection Pilgrims was a finalist for the PEN/Hemingway award; The Last American Man was a finalist for both the National Book Award and the National Book Critics Circle Award. Her follow-up memoir to Eat Pray Love, Committed, became an instant Number One New York Times bestseller. The Signature of All Things was longlisted for the Baileys Women’s Prize for Fiction and shortlisted for the Wellcome Book Prize. She lives in New Jersey.

www.elizabethgilbert.com

@GilbertLiz

[image error]

City of Girls

Bloomsbury Publishing

Released 4th June 2019

October 11, 2019

#BookBingo – Round 21

I’ve filled a horizontal line this round. Bingo!

Beloved Classic:

The Scarlet Letter by Nathaniel Hawthorne

I have a lot of beloved classics but just in case I don’t read anymore of them this year, I figured I’d better lock this one in! This round gives me another full row filled across the top of the card. Bingo!

The Scarlet Letter is a real treasure of a novel, in my opinion. It offers contemporary readers a view of a society that formed the basis of early American life. Hawthorne claims, from his place in 19th century New England, that the puritan ways still lingered, and not for the better; an interesting evaluation for him to publicly make. Of course, this part of America is the same one that conducted the Salem witch trials. It’s a society that was born out of fundamentalism, indeed, the colonists themselves had left England, the old country, in a bid to shrug off Catholicism and indulgence, with a view on beginning their lives anew in ‘purity’. Perhaps aspects of this linger there still. As far as classics go, The Scarlet Letter is a challenging read but a rewarding one. There is an omnipresent narration that reminds you right the way through that this is a cautionary tale, a love story doomed from the beginning. I think Hawthorne was a bit ahead of his times, with this novel anyway. I do really love a classic that is also an historical fiction. The impressions of an author writing about the 17th century from the distance of the 19th century is vastly different to a modern interpretation of the 17th century and therein lies its value sociologically. Needless to say, The Scarlet Letter is one of my recommended classics.

[image error]

For 2019, I’m teaming up with Mrs B’s Book Reviews and The Book Muse for an even bigger, and more challenging book bingo. We’d love to have you join us. Every second Saturday throughout 2019, we’ll post our latest round. We invite you to join in at any stage, just pop the link to your bingo posts into the comments section of our bingo posts each fortnight so we can visit you. If you’re not a blogger, feel free to just write your book titles and thoughts on the books into the comments section each fortnight, and tag us on social media if you are playing along that way.

[image error]

October 10, 2019

The Week That Was…

Back to work this week and I am really feeling the early mornings and busy days! My reading time has taken a hit this week on account of dropping off to sleep each time I get comfortable on the couch. As an end of week treat, I’m headed to the cinema to watch Downton Abbey tonight with friends!

October 8, 2019

Book Review: Rosa: Memories With Licence by Ros Collins

About the Book:

As British as Earl Grey tea, ‘Rosa’ has spent most of her life in Melbourne. Her children and grandchildren are all Australian-born, as was Alan, her writer husband. But Rosa is hesitant about an unconditional commitment to Vegemite, mateship and the ANZAC legend; she remains a perennial migrant, often amused by her memories, here presented with a deliberate overlay of lies and licence.

Her family’s history is nearer to Dickens than the shtetls of Eastern Europe; Rosa herself recalls Dunkirk and the Blitz. Beyond the conservatism of 1950s London that she escaped, Rosa flings open the windows and doors to invite the reader into her Anglo-Australian-Jewish family. She refrains from delving into deep psychological examinations of what it means to be an only child, an only grandchild, a reluctant Jewish teenager, and muse to a man whose terrible childhood scarred him for life; the ‘clues’ are all there for the curious reader to discover.

My Thoughts:

I would have to say that this is the most enjoyable memoir I have ever read. Maybe, in some part, this is owing to these words from the author in the introduction, where she describes the nature of her book:

‘Memoir with a little fiction, or fiction with a little history? It’s hard to say. Memories with licence.’

This instantly appealed to me, as memoirs and I have a difficult relationship. With this preface, I was able to just settle in and read, in the same way as I would with any fiction book. Ros writes in such a warm and conversational style, giving the reader the same feeling you would get if you were sitting opposite her drinking tea and listening to her recount memories and family stories. Her personality really shone through for me, turning this into a most enjoyable reading experience. Ros describes her book as a means of offering:

‘A small window into some unfamiliar scenes of Anglo-Australian-Jewish life.’

And this is exactly what she does. Rather than offer a chronological history, she has fashioned the book in a more eclectic style, like a series of vignettes, each chapter themed to a certain agenda. In this it wanders, but I liked that about it, dipping in and out of Rosa’s history, pondering alongside her on the greater meaning of life’s moments.

Rather than a life story, or even a journey of sorts, this book is more of an introspection on her personal Jewish history. Along the way, I learnt so much about what it means to be Jewish, pre and post Holocaust. I was also enlightened on the many ways in which being Jewish differs for people, much of this being dependent on where you have migrated from and your family’s history in relation to the Holocaust. There are some heavy themes touched on, but Ros keeps the book, as a whole, on an even keel. There is a lot of love infused into this book and it glows with warmth and genuine feeling.

By the time I reached the end, I realised that I hadn’t given much thought to what might be true and what might be fiction. I had been too busy just enjoying it all, which I would wager, was Ros’s intent. If you are at all interested in finding out about Anglo-Australian-Jewish life, then this might just be the book you have been looking for. Whether you are a fan of memoirs or not, this book has much to offer to all readers and I recommend it highly.

Thanks is extended to Hybrid Publishers for providing me with a copy of Rosa for review.

About the Author:

Ros Collins’ first book, Solly’s Girl, was published in 2015 as a companion piece to Alva’s Boy written by her late husband, Alan. Like him, she strongly believes in the power of humorous literature; any serious intent is clothed with a self-deprecating wit. Professionally, Ros Collins was a TAFE college librarian. In later years she was director of Makor Jewish Community Library (now the Lamm Jewish Library of Australia). She is interested in writing about Anglo-Australian-Jews, often overlooked in fiction and memoir. ‘We have an 1830s convict in our family – aristocracy!’ Ros shares her 1928 bayside cottage with Roxie, a very British corgi with republican tendencies.

[image error]

Rosa: Memories With Licence

Published by Hybrid Publishers

Released September 2019

October 7, 2019

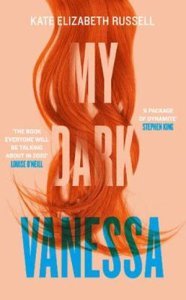

#BRPreview Book Review: My Dark Vanessa by Kate Elizabeth Russell

About the Book:

An era-defining novel about the relationship between a fifteen-year-old girl and her teacher.

ALL HE DID WAS FALL IN LOVE WITH ME AND THE WORLD TURNED HIM INTO A MONSTER.

Vanessa Wye was fifteen-years-old when she first had sex with her English teacher.

She is now thirty-two and in the storm of allegations against powerful men in 2017, the teacher, Jacob Strane, has just been accused of sexual abuse by another former student.

Vanessa is horrified by this news, because she is quite certain that the relationship she had with Strane wasn’t abuse. It was love. She’s sure of that.

Forced to rethink her past, to revisit everything that happened, Vanessa has to redefine the great love story of her life – her great sexual awakening – as rape. Now she must deal with the possibility that she might be a victim, and just one of many.

Nuanced, uncomfortable, bold and powerful, My Dark Vanessa goes straight to the heart of some of the most complex issues our age.

My Thoughts:

My Dark Vanessa is a profoundly disturbing narrative of manipulation disguised as love. Beautifully written literary fiction, yet challenging like no other novel I’ve read before. The scenario is provocative, the characters emotionally charged, the content instinctively relevant. Compulsive reading that I can’t help but recommend even if it does journey into territory I’d rather not contemplate. This is not a novel I devoured though, more like a partaking in fits and bursts. Vanessa herself is quite a toxic character, filled with so much self-loathing, and Jacob, well, he was sickening. And of course, the themes are ultimately distressing, so lightly does it in terms of approaching this one.

“I should be used to this by now but it’s still surreal – how he can talk about the books and also about me, and they have no idea. It’s like when he touched me behind his desk while everyone else sat at the table, working on their thesis statements. Things happen right in front of them. It’s like they’re all too ordinary to notice.”

Thanks is extended to HarperCollins Publishers Australia via Better Reading for providing me with a copy of My Dark Vanessa for #BRPreview.

About the Author:

Kate Elizabeth Russell is originally from eastern Maine. She holds a PhD in creative writing from the University of Kansas and an MFA from Indiana University. Her work has appeared in Hayden’s Ferry Review, Mid-American Review, and Quarterly West, among other journals, and has been nominated for a Pushcart Prize. She currently lives in Madison, Wisconsin. This is her first novel.

[image error]

My Dark Vanessa

Published by HarperCollins Publishers Australia – Imprint: 4th Estate – GB

Released 1st February 2020

October 6, 2019

Book Review: The Secrets We Kept by Lara Prescott

About the Book:

Sold in twenty-five countries and poised to become a global literary sensation, Lara Prescott’s dazzling first novel about the women in the CIA’s typing pool and the fate of Boris Pasternak’s banned masterpiece is a sweeping page turner and the most hotly anticipated debut of the year.

The September pick for Reese Witherspoon’s Hello Sunshine Book Club

TWO FEMALE SPIES. A BANNED MASTERPIECE. A BOOK THAT CHANGED HISTORY.

1956. A celebrated Russian author is writing a book, Doctor Zhivago, which could spark dissent in the Soviet Union. The Soviets, afraid of its subversive power, ban it.

But in the rest of the world it’s fast becoming a sensation.

In Washington DC, the CIA is planning to use the book to tip the Cold War in its favour.

Their agents are not the usual spies, however. Two typists – the charming, experienced Sally and the talented novice Irina – are charged with the mission of a lifetime: to smuggle Doctor Zhivago back into Russia by any means necessary.

It will not be easy. There are people prepared to die for this book – and agents willing to kill for it. But they cannot fail – as this book has the power to change history.

My Thoughts:

Stories about the Cold War era and life ‘behind the Iron Curtain’ have begun to intrigue me of late. Drawing on facts gleaned from declassified CIA documents pertaining to its secret Zhivago mission, The Secrets We Kept fills in the gaps, with fiction, of the incredible story behind the story that is Doctor Zhivago.

‘They had their satellites, but we had their books. Back then, we believed books could be weapons – that literature could change the course of history. The Agency knew it would take time to change the hearts and minds of men, but they were in it for the long game. Since its OSS roots, the Agency had doubled down on soft-propaganda warfare – using art, music, and literature to advance its objectives. The goal: to emphasize how the Soviet system did not allow free thought – how the Red State hindered, censored, and persecuted even its finest artists. The tactic: to get cultural materials into the hands of Soviet citizens by any means.’

I never studied literature at University so in many respects, I am rather ignorant about the stories behind some of the world’s greatest classics. The upside of this: there’s always an opportunity to find out something new. I haven’t read Doctor Zhivago, nor have I watched any adaptations. I’ve always had a bit of a fear of Russian literature which I can only attribute to the fact that the books are all so thick. I fear they might be complex too, so these two factors merged together have resulted in me never indulging in any Russian literature at all. This story behind Doctor Zhivago was very intriguing in itself, but the author of The Secrets We Kept didn’t stop there, and the resulting novel is one that grips from beginning to end, the layers of secrets and elements of danger weaving together in a manner that leaves the reader racing through the pages, your own tension mounting in tune with that on the page. In short, this is a sensational novel, in every sense of the word.

‘The initial internal memo described Zhivago as “the most heretical literary work by a Soviet author since Stalin’s death,” saying it had “great propaganda value” for its “passive but piercing exposition of the effect of the Soviet system on the life of a sensitive, intelligent citizen.” In other words, it was perfect.’

The novel is told from a range of perspectives, alternating between the East and the West, which I felt worked really well. This is at its heart a story about women, as much as it is about a banned manuscript. It’s a complicated story told in the least complicated manner; I honestly couldn’t put it down. I particularly enjoyed the chapters told from the perspective of The Typists – very illuminating. There is so much within this story to think about, but one thing that struck me more than anything else was the disregard for consequence on the part of the CIA. I found myself at first getting very caught up in the thrill of the plan: get a hold of the banned manuscript, translate it back into Russian and then smuggle it into the USSR. What can the Russian authorities do, when the book falls into so many different people’s hands, despite their best efforts at banning it? Turns out they could do plenty and it’s this side of the story that left me uneasy. It’s kind of like upsetting the applecart without sticking around to see what happens to the apples. Sure, the applecart has been destabilised, but what of the fate of the apples? The apples still exist. The fate of the apples should be equally as important as what’s going on with the cart.

The consequences of Doctor Zhivago being published globally whilst banned in Russia had far reaching consequences for its author, and even more so for his mistress and her children, who suffered greatly at the hands of KGB ‘justice’. The initial foreign publication was by Italian publisher and lover of literature, Giangiacomo Feltrinelli. He set the ball rolling on what was to become a Nobel Prize winning novel. The CIA capitalised on what was already shaking up authorities within the USSR by obtaining a copy, having it translated back into Russian, publishing cheaper light weight versions and then distributing them to visiting Russians at the 1958 World Expo in Bussels. From here, Doctor Zhivago spread through the black market in Russia. It was this same year, 1958, that the novel was awarded the Nobel Prize. You can imagine the Russian authorities were pretty, ahem, annoyed at the entire affair. Someone needed to pay.

Which brings us to the author and his mistress, Olga Ivinskaya. While Boris Pasternak had long been on the KGB’s watch list for his anti-Soviet sentiments conveyed through his poetry, it was Olga who bore the brunt of Boris’s inability to toe the line. Prior to Doctor Zhivago being published, she spent three years in the Gulag simply because she was his girlfriend. The KGB figured, as you do, that by punishing Olga, Boris would cease writing the novel they had heard so many juicy rumours about. It didn’t work. Olga later was sentenced to eight years back in the Gulag after Boris’s death, purely as punishment for not ‘stopping Zhivago and controlling Boris more effectively’. They also imprisoned her daughter for a year on bogus charges of hiding foreign earnings. Olga was quietly released after serving four years. But where was the CIA in all of this? Probably off upsetting other applecarts. Don’t worry about those apples. They’ll sort themselves out.

And then there’s the story of The Typists, all university qualified women, some former highly experienced WWII agents, all relegated to the typing pool within the CIA. The misogyny rampant throughout the organisation was just appalling. Sally’s experiences are a dire example of just how disposable the skills of women were. And I have to say, hell hath no fury like a woman ignored – no, I haven’t misquoted, I just feel in this instance, ignored is more apt than scorned.

The manner in which this story is told is both clever and cutting. I really enjoyed the author’s style and the way in which the novel was structured. There’s some clever work done with the headings of chapters as the novel progresses which amused me to no end. It’s rather a long novel, but it doesn’t feel that way while you’re reading it. When I say I devoured it, I’m not joking, I didn’t want to stop reading. Needless to say, this one comes highly recommended to you from me. One of my top reads of the year, for sure.

Thanks is extended to Penguin Random House Australia for providing me with a copy of The Secrets We Kept for review.

About the Author:

Lara Prescott received her MFA from the Michener Center for Writers at the University of Texas, Austin. Before she started the MFA, she was an animal protection advocate and a political campaign operative. Her stories have appeared in The Southern Review, The Hudson Review, Crazyhorse, BuzzFeed, Day One, Tin House Flash Friday, and other places. She won the 2016 Crazyhorse Fiction Prize (and Pushcart honorable mention) for the first chapter of The Secrets We Kept, which she spent years researching.

[image error]

The Secrets We Kept

Published by Penguin Random House Australia – Imprint: Hutchinson

Released 3rd September 2019

October 4, 2019

Six Degrees of Separation from Three Women to The Summer of Impossible Things…

It’s the first Saturday of the month which means a new round of #6degrees and this month’s starting book is Three Women by Lisa Taddeo.

You can find the details and rules of the #6degrees meme at bookaremyfavouriteandbest, but in a nutshell, everyone has the same starting book and from there, you connect to other books. Some of the connections made are so impressive, it’s a lot of fun to follow.

I haven’t read the starting book for this month’s six degrees and with a tagline like this:

‘Desire as we’ve never seen it before: a riveting true story about the sex lives of three real American women, based on nearly a decade of reporting.’

…it’s unlikely I ever will. I honestly can’t think of something that would repel me more.

Of course, this book is being advertised as ‘the next big thing’ and is a NY Times #1 bestseller. The last NY Times #1 bestseller I read was The Nest by Cynthia D’Aprix Sweeney and it was possibly one of the most shallow books I’ve ever read. Nothing at all like Nest by Inga Simpson, of which it shares a name. Nest culminates in the ‘big wet’ (a Queensland summer weather pattern) which also features in The Breeding Season by Amanda Niehaus. The Breeding Season is chiefly about grief, specifically, the loss of a child to stillbirth. In this it shares themes with The Trick to Time by Kit de Waal. In this book, a young Irish girl leaves home and moves to a Birmingham boarding house for an independent life. This immediately puts me in mind of Brooklyn by Colm Toibin. The destination may differ, but the era and starting points for the characters are similar. Any book about Brooklyn will lead me to The Summer of Impossible Things by Rowan Coleman, which is so very Brooklyn you almost feel like you are right there alongside the characters.

And there you have it. I wonder where next month’s starting book will take me?