Jason Micheli's Blog, page 99

September 9, 2019

God *Needs* for All to be Saved

I often wonder if Christians are so beholden to belief in an eternal hell because they fail to realize that the doctrine of creation is not merely an explanation of origins but is an eschatological claim, as concerned with our whither every bit as much as our whence.

I often wonder if Christians are so beholden to belief in an eternal hell because they fail to realize that the doctrine of creation is not merely an explanation of origins but is an eschatological claim, as concerned with our whither every bit as much as our whence.

Precisely because that whence is sheer gift, the whither— if God is indeed Good— can only lead to one End, the One.

Belief in an eternal hell relies upon a literal, which is to say static, reading of Genesis. Only such a reading, where the term ‘creation’ is circumscribed to the first six days, can make belief in a Last Day that begets eternal torment coherent.To preach fire and brimstone of the ultimate variety one must first conjugate the Triune God’s deliberation (“Let us make humankind in our image…”) into the past tense.

When Christians erroneously suppose that the doctrine of creation refers to our beginnings, in the past, they not only get into misbegotten debates pitting science vs. scripture, they fail to realize that belief in an eternal hell is morally contradictory to belief in creatioex nihilo, creation from nothing.

Christians do not posit creation from nothing as a claim about the origins of the universe. Nor do we mean it merely as a metaphysical one— that ‘God’ is the answer we give to the question ‘Why is there something instead of nothing?’ Of course it includes both of those claims but creation from nothing is hardly reducible to either of them; instead, creation from nothing, as Church Fathers like Gregory of Nyssa saw clearly, does not refer to God’s primordial act but to an eschatological one which witnesses to God’s ultimate, as in teleological, relation to creation.

For Christians, the doctrine of creation from nothing is not a belief about what God did, billions or thousands of years ago. It’s a confession that necessarily includes what God has done, is doing, and will do unto fruition.

Creation from nothing isn’t so much a statement about what God did or what God does but its a statement about who God is.

To say that God creates ex nihilo is to assert that God did not need creation. God, who is Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, is, already and eternally so, sufficient unto himself, a perfect community of fullness and love, without deficit or need and with no potentiality. Creation from nothing confesses our belief that the world is not ‘nature’ but creation; that is, it is sheer gift because the Giver is without any lack. Creation is not necessary to God. It is not the terrain on which God needs to realize any part of an incomplete identity.

Creation from nothing then is shorthand for the Christian assertion that the Creator is categorically Other from his creation, that the Transcendent is absolutely distinct from the temporal. Simultaneously, however, creation from nothing requires that though— really, because— Creator and creation are ontologically distinct they are morally inseparable.

Precisely because God did not need to create, because creation is sheer gift, God ‘needs’ for creation to reveal his goodness.

Morally speaking, God is now bound to creation’s end because its beginning was not bound to him. In other words, for creation to be gift and the Giver to be good, then God ‘must’ bring to fruition his purpose in creation, “Let us make humankind in our image,” for all causes are reducible to and reflect their First Cause. If creation proves ultimately to be less than good (with an eternal torment for some of creation), then the Creator is no longer in any logical sense the Good.

As my first teacher David Bentley Hart argues:

“In the end of all things is their beginning, and only from the perspective of the end can one know what they are, why they have been made, and who the God is who has called them forth.”

God’s creative purpose does not refer to Adam and Eve’s first day on the third. It was not fulfilled prior to the Fall nor would it have been without it. If, before their mistrust in the Garden, Adam and Eve already bore the fullness of God’s image then God is but a god, and it’s no longer intelligible what we mean by saying Christ is the image of the invisible God for the chasm between Adam and Jesus is only slightly less than infinite.

What Christians mean by the imago dei is not immediate.

It is, in fact, inseparable from what we call sanctification.

Perfection.

God’s “Let us…” does not refer to the events of day 3 of creation but names the plot of the entire salvation story.

Making us- that is, humanity, all of us- into the image of Father, Son, and Spirit is what God is bringing to pass in calling Israel, in taking flesh in Christ, in sending the Spirit, and, through the Spirit, sending the Church to announce the Gospel.

As Gregory saw it, we can only truly say that God ‘created’ when all of creation finally has reached its consummation in the union of all things with the First Good.

Belief in an eternal hell is absurd then exactly because what Christians mean by belief in the imago dei is not immediate but ultimate.

Creation from nothing for the purpose that humanity would bear gratuitously the image of the good God is what God began in Genesis, what God is doing now through the Spirit, and what God has promised to bring to completion in Christ. Eternal hell does not comport with this telos, this End, towards which God has created us.

Indeed belief in eternal hell, where some portion or multitude of humanity is forever lost and forsaken, contradicts belief in creation from nothing, for if God’s promised aim is that, in the fullness of time all of humanity will bear his image, the promise can never be consummated apart without all of humanity included in it.

In creating ex nihilo, God makes himself our end as much as our beginning, the latter being wholly gratiutous makes the former entirely necessary— for all of us.

Follow @cmsvoteup

September 7, 2019

If We’re “Free” to Choose Hell, Then is god Evil?

I’ve been reading a draft of David Bentley Hart’s new book, and towards the end he turns to the argument from “freedom.”

I’ve been reading a draft of David Bentley Hart’s new book, and towards the end he turns to the argument from “freedom.”

If it’s true that God consigns or consents his creatures to an eternal hell then, begs the question, is God evil?

Simply because God (allegedly) does it, doesn’t make it good or just or, even more importantly, beautiful. So we should muster up the stones to ask the obvious question to such a grim assertion: is God evil?

Our concepts of goodness, truth, and the beautiful, after all, emanate from God, who is the perfection of Goodness, Truth, and Beauty; therefore, they participate in the Being of God and correspond to the character of God. Sin-impaired as we are, we can yet trust our God-given gut. Again then, the question— and forget that it’s God we’re talking about— is God evil?

If the calculus of God’s salvation balances out with a mighty, eternally-tormented, remainder, then is God the privation haunting the goodness of his own creation?

For some reason— I conclude from the three passionate arguments DBH’s provoked in the bakery yesterday— eternal hell is the cherished, sacrosanct doctrine of a good many Christians, clergy included, which, I confess, makes me wonder if the decline of the Church is a moral accomplishment. I frankly can’t think of a better descriptor than evil (or maybe monstrous) for a being who creates ex nihilo, out of love gratuitously for love’s sake, only to predestine or permit the eternal torment of some or many of his creatures for supposedly just ends (nevermind, as DBH points out, an eternal punishment, which is not purgative, cannot, by definition, be just.

Grace is more grim than amazing if its constitutive of a being who declares “Let us make humanity in our image…” only to impose upon them an inherited guilt which leads inexorably, except for the finite ministrations of altar calls and evangelism, to eternal hell.

The inescapable moral contradictions and logical deficiencies of belief in an eternal hell require us to assert that God’s essence, his very nature, is secondary to his will. Something is good, then, not because it corresponds to the Goodness that is the nature of God, who can only do that which is Good because he is free and perfect to act unconstrained according to his nature. Rather, simply because God does it, it is good. In other words, it is good for God to consign scores to an eternal torment because God does it. Any sense of justice we have that would cause us to recoil is only a human category, such Christians speculate, and has no corollary in the character of God.

Which, of course, is utter bulls#$%.

A popular (and ostensibly more civilized) perspective on hell attempts to remove the nasty veneer by replacing God as the active agent of damnation.

Excusing God from culpability, which is but a tacit acknowledgement of hell’s Christian incoherence, many fire and brimstone apologists appeal to our human freedom and God’s respect for its dignity.

God does not consign creatures to Hell.

God, like the parentified child in an abusive family, merely consents to Hell.

God consents, so the argument goes, to the risk inherent in any loving relationship, which is the possibility that his creatures will reject his love and choose Hell over Him.

Despite its tempered, rational appearance, this is perhaps the worst argument of all in favor of an eternal hell. Rather than esteeming our creaturely freedom or God’s privileging of it, it sacralizes the very condition from which we’re redeemed by Christ: bondage.

Captivity.

Slavery to Sin and Death.

The fatal deficiency in the free will defense of the fire and brimstone folks is that it employs an understanding of “freedom” that is incoherent to a properly tuned Christian ear. The breadth of the Christian tradition would not recognize such a construal of the word freedom.

For the Church Fathers, indeed for St. Paul, our ability to choose something other than the Good that is God is NOT freedom but a lack of freedom.

It’s a symptom of our bondage to sin not our liberty from it.

“It is for freedom that Christ has set us free.”

For Christians, freedom is not the absence of any constraint upon our will. Freedom is not the ability to choose between several outcomes, indifferent to the moral good of those outcomes. In other words, freedom is not the ability to choose whatever you will; it is to choose well.

You are most free when your will more nearly corresponds to God’s will.

Because we are made with God’s creative declaration in mind (“Let us make humanity in our image…”) the freedom God gives us is not unrestrained freedom or morally indifferent freedom. It is not the freedom to choose between an Apple or a Samsung nor the freedom to choose between Hell or Heaven.

The freedom with which God imbues us is teleological freedom; that is, our freedom is directed towards our God-desired End in God. As creatures, oriented towards the Good, our freedom is purposive. Freedom is our cooperating with the grain of the universe.

We’re free when we become more who we’re created to be.

As Irenaeus says, the glory of God is human being fully alive. Only a fully alive creature in God’s glory is truly free. Freedom, then, is not the ability to do what you want. Freedom is to want what God wants: communion with Father, Son, and Spirit. You are most free, Christians have ALWAYS argued, when your will becomes indistinct from God’s will.

“The will, of course, is ordered to that which is truly good. But if by reason of passion or some evil habit or disposition a man is turned away from that which is truly good, he acts slavishly, in that he is diverted by some extraneous thing, if we consider the natural orientation of the will,” writes Thomas Aquinas.

Christian grammar insists that you are most free when you no longer have any choice because your desire is indistinct from God’s desire. You’re willing and the Good are without contradiction. Nothing, no sin or ignorance, is holding you back. You’re no longer in bondage. Janis Joplin was nearly correct. Freedom is nothing left to lose choose.

As my teacher David Bentley Hart writes:

“No one can freely will the evil as evil; one can take the evil for the good, but that does not alter the prior transcendental orientation that wakens all desire. To see the good truly is to desire it insatiably; not to desire it is not to have known it, and so never to have been free to choose it.”

And just in case you can’t connect the dots to perdition, he continues:

“It makes no more sense to say that God allows creatures to damn themselves out of his love for them or his respect for their freedom than to say a father might reasonably allow his deranged child to thrust her face into a fire out of a tender regard for her moral autonomy.”

The creature that chooses not to enter into God’s beatitude is by definition not a free creature but captive.

Captive still to sin.

If it’s true that we can choose Hell rather than God, forever so, then for those who do Christ is not their Redeemer. And if not, then he was not. If not for them, then not for any of us and the god who purportedly took flesh inside him for the redemption of ALL captives is a liar and maybe a monster.

In either case, he’s neither good nor the Good.

Follow @cmsvoteup

September 6, 2019

Episode #224 — Dr. Beverly Gaventa: On the Precipice of Heresy

“Authentic Pauline Christianity always stands on the precipice of heresy…”

– Karl Barth, Introduction to Romans, 2nd Edition

Beverly Gaventa is back on the podcast to talk about Paul’s Letter to the Romans and the 100th Anniversary of Karl Barth’s commentary on it. Formerly of Princeton, Dr. Gaventa is a professor of New Testament at Baylor Univesity and is the author of When in Romans, which is now available in paperback.

Check out her lecture on Barth and Romans from Princeton’s 2019 Barth Conference: https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=p4-r_vUsvEc

Don’t forget! Go to www.crackersandgrapejuice.com and click on SWAG to get your own Stanley Hauerwas “Jesus is Lord and Everything Else is Bullshit” t-shirt. Or, click “Support the Show” to become a patron of the podcast and receive a free “Incompatible with Christian Teaching” pint glass.

Follow @cmsvoteup

September 5, 2019

All Shall Be Saved

I’ve been reading a review copy of David Bentley Hart’s latest book, That All Shall Be Saved: Heaven, Hell, and Universal Salvation. I’m prejudiced in favor of it; David was my first theology teacher at UVA. His influence upon me, not long after I became a Christian, has abided and may prove permanent.

I’ve been reading a review copy of David Bentley Hart’s latest book, That All Shall Be Saved: Heaven, Hell, and Universal Salvation. I’m prejudiced in favor of it; David was my first theology teacher at UVA. His influence upon me, not long after I became a Christian, has abided and may prove permanent.

If nothing else, DBH’s new book will give Christians permission to return to the New Testament and see, maybe for the first time, that which it names quite clearly: that the God who created all that is ex nihilo as sheer good gratuity, the God who is all and in all, is the God who desires the salvation of all.

“This is right and is acceptable in the sight of God our Savior, who desires everyone to be saved and to come to the knowledge of the truth.” – 1 Timothy 2.3-4

Apparently, to many who worship the God who just is Love, to assert that God desires the salvation of all constitutes a “treacherous absurdity.” It’s a betrayal of the Gospel, I’ve been told in the not so hushed tones of all caps messages, to suppose that the triune God who announced his creative aim in Genesis 1 (“Let us make humankind in our image…”) will not forsake his endeavor until it has reached final consummation, that in the fullness of time humanity will finally bear the full glory of God’s image. Evidently, I take it from these Calvinists in threadbare sheep’s clothing, it’s better to confess that God-with-us may be our Alpha but he is not our End. At least, not for all of us.

It’s amazing to me that those most vested- presumably- in protecting the gravity of sin, the majesty of salvation, and the authority of scripture ignore what scripture itself testifies about it and the nature of the God revealed therein. Spurred by David Bentley Hart, I actually counted them up. The New Testament contains no less than 47 verses which affirm the ‘all-ness’ of God’s salvation compared to the 4 oft-cited but decidedly cryptic verses which may (or as easily may not) suggest eternal torments for the wicked.

47 vs. 4

What was obvious to the ancient Church Fathers, the totality of God’s salvific aim, has become so hidden it now sufficiently smacks of heresy to exile Rob Bell from the pulpit to the Oprah Channel.

A hero of mine, Karl Barth, famously said that as Christians scripture does not permit us to conclude that all will be saved but that as Christians we should hope and pray that all will be saved. Barth’s is a more generous sentiment than I hear from many Christians today, but despite his reticence DBH argues that the logic of the Gospel requires us to say more.

If God desires the salvation of all, he argues rather irrefutably, it is a logical absurdity to assert that the transcendent God will ultimately fail in accomplishing his eschatological will.

The belief in an eternal hell where some are forever excluded from the ‘all-ness’ of salvation echoed by scripture- that is the absurdity which begets still other absurdities like the Calvinist notion that God predestined some to salvation and others to perdition.

Just as God cannot act contrary to his good nature, so too God cannot fail to realize the good he desires. To say, as scripture does, that God desires the salvation of all is to say simultaneously and necessarily, as scripture implies, that all will be saved, that all things will indeed be made new.

Consider the counter:

If not, if we in our sin (or, worse, in our “freedom”) thwart God’s will and desire, casting ourselves into a fiery torment despite God’s sovereign intention, God would not be God. Or, to put it simpler if more baldly, we would be God. Or, still more pernicious, evil, as that which has successfully resisted God’s creative aim though it is no-thing, would be God.

Evil would God.

Thus the belief in an eternal hell betrays the fact that it’s possible for perfect faith to be indistinguishable from perfect nihilism.

It’s clear how offensive the ‘all-ness’ of God’s sovereign saving love can strike the moral ear. For that ‘all-ness’ must include our enemies too.

To suggest instead that even if Christ came for all and died for all only some will be saved better conforms to our calculus of justice, but it is a moral calculus that is not without remainder, for it makes of evil an idol and of (the once transcendent) God a liar.

Therefore just as one man’s trespass led to condemnation for all, so one man’s act of righteousness leads to justification and life for all. For just as by the one man’s disobedience the many were made sinners, so by the one man’s obedience the many will be made righteous. – Romans 5.18-19

For God has imprisoned all in disobedience so that he may be merciful to all. – Romans 11.32

Follow @cmsvoteup

September 2, 2019

It’s All Christophany

Sunday, we kicked off a year-long sermon series through scripture called the Jesus Story Year.

“Jesus Christ [not the Bible] is the one Word of God whom we have to hear, and whom we have to trust and obey in life and in death…Jesus Christ is God’s vigorous announcement of God’s claim upon our whole life.”

Those lines constitute the opening salvo of the Barmen Declaration, the Confession of Faith written by the pastor and theologian Karl Barth in 1934 on behalf of the dwindling minority of Christians in Germany who publicy repudiated the Third Reich.

Barth wrote the whole document while his colleagues slept off their lunchtime booze.

“We reject the false doctrine,” Barth wrote, “that there could be areas of our life in which we do not belong to Jesus Christ but to other lords…With both its faith and its obedience, the Church must testify that it belongs to and obeys Christ alone.”

I studied Karl Barth at Princeton. My teacher, George Hunsinger, had a thick, white beard and reading glasses perched at the end of his nose. A photograph of Karl Barth laughing with Martin Luther King Jr. hung in his office. The picture captured Barth’s first and only visit to the United States.

I remember we were discussing Barth’s Barmen Declaration in class, and Dr. Hunsinger, uncharacteristically, broke from his lecture and took off his reading glasses. His jovial countenance turned serious, and he said, seemingly at random though not random at all, “just outside the Dachau concentration camp in Bavaria, immediately outside the walls of the camp, there was and still is a Christian church.”

It was an 8:00 class but suddenly no one was fighting off a yawn.

“Just imagine,” he said, “the prison guards and the commandant at that concentration camp probably went to that church on Sundays. They confessed their sins and received the assurance of pardon and prayed to the God of Israel and the God of Jesus Christ there, and then they walked out of the church and went back to the camp and killed scores of Jews not thinking it in any way contradicting their calling themselves Christians.”

“How does that work?” someone joked, trying to take the edge off.

“It happens,” he replied, “when you reduce the Gospel to forgiveness and you evict Jesus Christ from every place but the privacy of your heart.”

His righteous anger was like an ember warming inside him.

“Whenever you read Karl Barth,” the professor told us,” think of that church on the edge of the concentration camp. Think of the pews filled with Christians and the ovens filled with innocents and then think about what it means to call Jesus Lord.”

Notice—

Cleopas and the other disciple on the road to Emmaus, they’re not unawares.

They’ve heard the Easter news. They’ve heard from the women who dropped their embalming fluid and fled to tell it. They’ve heard from Peter. They’ve heard that the tomb is empty.

And yet—

Having heard that Death has been defeated, having heard that the Power of Sin has been conquered, and having heard that self-giving, cheek-turning, cruciform love has been vindicated from the grave, our moral imagination is so impoverished that the first Easter Sunday isn’t even over and here we are (in these two disciples) walking back home as if the world is the same as it ever was and we can get back to our lives as knew them.

They’ve heard the Easter news, yet these two disciples still make two common mistakes— two common reductions— in how they understand Jesus.

“Jesus of Nazareth was a prophet mighty in deed and word before God,” they tell the stranger (who is Christ). True enough, but not sufficient.

“We had hoped he would be the one to liberate Israel,” they tell him, “we had hoped he was the revolutionary who would finally free us from our oppressors.” Again, their answers aren’t wrong; their answers just aren’t big enough.”

It’s not until this stranger breaks bread before them that their eyes are opened and they run— in the dark of night, eight miles to Emmaus, they run— to go and tell the disciples what they’ve learned.

And when they get there, after the Risen Jesus has taught them the Bible study to end all Bible studies— what have the learned?

They don’t call Jesus a prophet.

They don’t dash after the disciples to report “God has raised Jesus, the prophet, from the dead.”

They don’t call Jesus a liberator.

They don’t run to Peter and say “Jesus the revolutionary has been resurrected.”

They don’t even call him a savior or a substitute.

They don’t dash after the disciples to report, “The Lamb of God who took away the sins of the world has come back.”

No, after the Risen Jesus interprets Moses and the prophets for them (ie, the Old Testament; ie, the only Bible they knew) they take off to herald the return of Jesus the kurios.

They confess their faith in Jesus as kurios.

“The kurios is risen indeed!” they proclaim to Peter.

Luke book-ends his Gospel with that inconviently all-encompassing word kurios.

The whole entire Bible, Jesus has apparently taught these two, testifies to how this crucified Jewish carpenter from Nazareth is the kurios who demands our faith.

Kurios.

Lord.

The word we translate into English as faith is the word pistis in the Greek of the New Testament. And pistis has a range of meanings. Pistis can mean confidence or trust. It can mean conviction, belief, or assurance. And those are the connotations we normally associate with the English word faith.

In Christ alone by grace through trust alone.

Through belief alone, is how we hear it.

But— here’s the rub— pistis also means fidelity, commitment, faithfulness, obedience.

Or, allegiance.

Allegiance.

Now, keep in mind that the very first Christian creedwas “Jesus is kurios” and you tell me which is the likeliest definition for pistis.

So how did we go from faith-as-obedience to faith-as-belief?

How did get from faith-as-allegiance to faith-as-trust?

I’m glad you asked.

When Luke wrote his Gospel and when Paul wrote his epistles, Christianity was an odd and tiny community amidst an empire antithetical to it.

Christianity represented an alternative fealty to country and culture and even family.

Back then—

Baptism was not a cute christening.

Baptism was not a sentimental dedication.

Baptism was not a blessing, a way to baptize the life you would’ve lived anyway.

Back then, to be baptized as a Christian was a radical coming out. It was an act of repentance in the most original meaning of that word: it was a reorientation and a rethinking of everything that had come before.

To profess that “Jesus is Lord” was to protest that “Caesar is not Lord.”

The affirmation of one requires the reununciation of the other.

Which is why, in Luke’s day and for centuries after, when you submitted to baptism, you’d first be led outside.

By a pool of water, you’d be stripped naked.

Every bit of you laid bare, even the naughty bits.

And first you’d face West, the direction where the darkness begins, and you would renounce the powers of this world, the ways of this world, the evils and injustices of this world.

And the first Christians weren’t bullshitting.

For example, if you were a gladiator, baptism meant that you renounced your career and got yourself a new one.

Then, having left the old world behind, you would turn and face East, the direction whence Light comes, and you would affirm your faith in Jesus the kurios and everything your new way of life as a disciple would demand.

And the first Christians— they walked the Jesus talk of their baptismal pledge.

For example, Christians quickly became known— before almost anything else— in the Roman Empire for rescuing the unwanted, infirm babies that pagans would abandon to die in the fields.

Baptism wasn’t an outward and visible sign of your inward and invisible trust.

Quite the opposite.

Baptism was your public pledge of allegiance to the Caesar named Yeshua.

If that doesn’t sound much like baptism to you, there’s a reason.

A few hundred years after Luke wrote his Gospel and Paul wrote his letters, the kurios of that day, Constantine, discovered that it would behoove his hold on power to become a Christian and make the Roman Empire Christian too.

Whereas prior to Constantine it took significant conviction to become a Christian, after Constantine it took considerable courage NOT to become a Christian.

After Constantine, now that the empire was allegedly Christian, the ways of the world ostensibly got baptized; consequently, what it meant to be a Christian changed.

Constantine is the reason why whenever you hear Jesus say “render unto Caesar the things that are Caesar’s and render unto God the things that are God’s” it doesn’t occur to you that Jesus is being sarcastic.

What had been an alternative way in the world became, with Constantine, a religion that awaited the world to come.

Jesus was demoted from the kurios, who is seated at the right hand of the Father and to whom has been given all authority over the Earth, and Jesus was given instead the position of Secretary of Afterlife Affairs.

Which meant pistis eventually became synonymous with trust.

Faith moved inside, to our heads and hearts, from embodiment to belief.

I apologize for the historical detour, but I figure if you’re such an over-acheiver that you come to church on Labor Day weekend then you ought to be able to handle it.

I want you to see how it’s the shift that happened with the kurios called Constantine that makes it difficult for us to hear rightly when we hear Cleopas call Jesus Lord.

It’s this difficulty that leads to us confusing faith with belief, making pistis private, and reducing the Gospel to after life affairs.

It’s this shift that happens with the kurios called Constantine that produces nonsensical rubbish like the statement “I believe Jesus is Lord, but that’s just my personal opinion.”

Walking along the way to Emmaus, Luke reports that the Risen Christ “interpreted to [Cleopas and the other disciple] all the things about himself in all of the scriptures, beginning with Moses and all the prophets.”

Straight out of the grave, what Jesus wants his disciples to know is that the whole Bible is about him.

The Apostle Paul registers the same claim in his letter to the Romans when he declares that “Jesus Christ is the telos of the Law.”

Telos means end; as in, aim or goal.

Christ is the telos of the Torah, Paul writes.

The Bible is about me, Jesus says today. I am the Alpha and the Omega, the beginning of the Bible and the end, from the first page to the last page.

It’s all Christophany.

It’s all an epiphany of Christ.

It’s not “The Old Testament is over here and the New Testament is over here and the two are radically distinct from one another.”

No, that’s called heresy.

All of it— it’s purpose, Jesus teaches today— is to reveal Jesus Christ to us, to apprentice us under Jesus Christ.

Everything God had heretofore revealed to his People— all of it— telegraphs the way of Christ.

All those strange kosher laws in Leviticus?

They anticipated the day when Christ would call his disciples to be a different and distinct People in the world.

“Eye for an eye?”

In a world of wildly disproportionate justice, “eye for an eye” was meant to prepare a People who could turn the other cheek.

God forbade his People to make graven images because the Father has no visible image but the eternal Son who would take flesh and dwell among us.

Christ is the telos of the Bible, Paul says.

Everything in the Bible telegraphs the way of Christ.

God’s People wandered as refugees and aliens in a foreign land in order to make ready a People capable of Christ’s command to welcome the foreigners in their own land.

God disciplined his People Israel to love neighbor as though the neighbor was God; so that, in Jesus Christ there might be a People schooled to love their enemy, for such a People— a people who’re trained to love their enemy— can never rightly call the Constantines of our world kurios.

After the professor told us about the church at the edge of the concentration camp, he told us about Le Chambon-sur-Lignon, a Protestant village in the hills of southern France.

Around the same time Karl Barth was drafting his call to Christian resistance, Andre Trocme became the town’s pastor. In 1940, after the fall of France, Jewish refugees began arriving by the hundreds in Le Chambon seeking sanctuary.

Without so much as a discussion or debate, Trocme and his parishioners began taking them into their homes and barns and, whenever German soldiers showed up, hiding them up in the mountains.

Still more refugees arrived as word among the Jews spread that this was a community whose only Fuhrer was Jesus Christ.

The villagers of Le Chambon did not decide that their home would become a haven for refugees. They did not cast themselves in the role of rescuers.

In the process of obeying Jesus Christ, they simply now found themselves with refugees before them.

Villagers later told a biographer they believed that having suffered under three centuries of Catholic persecution they’d developed “the habit of quietly refusing to dilute the claims the faith makes upon us.”

“The Bible tells the story of Jesus,” one village woman explained, “and the story of Jesus reveals God’s way in the world so it would be self-destructive to live according to any other way, wouldn’t it? What the refugees asked of us was no different than what we had always done— abide with Jesus.”

Once, in February 1943, Nazi police arrived to arrest the pastor and some of his parishioners. The police officers sat in a villager’s living room waiting for the would-be prisoners to go fetch their suitcases.

The woman in whose house they waited invited the policemen to join her at her dinner table— despite the fact that Jews were hiding upstairs in her bedroom.

When asked by a biographer how she could be so hospitable to enemies who were there to take her husband away, perhaps to his death, the woman, Magda, replied:

“It was dinner time…the food was ready…how could I not invite them to eat with me? Don’t use such foolish words as “forgiving” and “good” with me. Inviting strangers and enemies to supper is just the normal thing to do if Jesus is Lord.”

As the pastor, Andre Trocme, taught a men’s circle, all of whom harbored Jews in their homes, “If Jesus Christ is not only Lord but the one “by whom all things were made” then this life isn’t so much what Christ demands. It’s the life Christ has designed for all of us.”

Faith is a trust that takes the form of allegiance— lived out loyalty, embodied belief— not because we could ever measure up to the example of Christ, not because we’ll be graded on the quality of our performance, but because if Jesus Christ is the kurios “by whom all things are made” then the life of Jesus reveals the grain of the universe, and a beautiful life will be yielded by no other pattern.

.

.

Follow @cmsvoteup

August 30, 2019

Episode #223 — Alan Cross: When Heaven and Earth Collide: Racism, Southern Evangelicals, and the Better Way of Jesus

You might think advocating for immigrants and refugees and against racism would be lonely work in the Southern Baptist Church. Turns out…it is. Our guest for the latest episode of C&GJ is Alan Cross. Alan is a Southern Baptist pastor from Alabama and currently ministering in California. A frequent contributor to publications, he’s the author of the book When Heaven and Earth Collide: Racism, Southern Evangelicals, and the Better Way of Jesus.

You might think advocating for immigrants and refugees and against racism would be lonely work in the Southern Baptist Church. Turns out…it is. Our guest for the latest episode of C&GJ is Alan Cross. Alan is a Southern Baptist pastor from Alabama and currently ministering in California. A frequent contributor to publications, he’s the author of the book When Heaven and Earth Collide: Racism, Southern Evangelicals, and the Better Way of Jesus.

When Heaven and Earth Collide is an investigation into what went wrong in the American South in regard to race and religion—and how things can be and are being made right. Why, in a land filled with Christian churches, was there such racial oppression and division? Why didn’t white evangelicals do more to bring racial reconciliation to the South during the 19th and 20th centuries? These questions are asked and answered through an exploration of history, politics, economics, philosophy, and social and theological studies that uncovers the hidden impetus behind racism and demonstrates how we can still make many of the same errors today—just perhaps in different ways. The investigation finally leads us in hopeful directions involving how to live out the better way of Jesus with an eye on heaven in a world still burdened and broken under the sins of the past.

Before you listen…head to www.crackersandgrapejuice.com. If you become a patron of the podast, we’ll send you a free “Incompatible with Christian Teaching” pint glass. You can also order your very own Stanley Hauerwas “Jesus is Lord and Everything Else is Bullshit” t-shirt.

Follow @cmsvoteup

August 25, 2019

Every Last Loser

I’m sorry if you’ve been led to believe that Jesus should mind his own business and stay out of the public square.

“I don’t want to hear about politics at church!”

It’s maybe the only surviving bipartisan sentiment. Church folks always want the Church to stay out of politics, which for most of us— let’s be honest now— usually means we don’t want the Church to challenge our particular hue of politics.

I remember—

One Sunday back in my very first church just outside of Princeton, after I preached an allegedly “political” sermon against state-sponsored torture, which both of America’s political parties supported at the time (this was right after September 11), this ruddy-faced church member assaulted me in the narthex and, sticking his finger in my chest, hollored at me, “Just where do you get off preaching like that, preacher?!”

I stammered.

So he pressed me.

“If Jesus were still alive, do you honestly think he’d having anything to say about torture and the government?!”

“Um, well, uh…I mean, he was crucified, I think…um…maybe he would have…” I started to say.

He shook his head and waved me off.

“Jesus would be rolling over in his grave if knew you’d brought politics into our church!”

Of course, that’s the rub.

It’s not our church. It’s not my church. It’s not your church. It’s not our church. It’s his Church. We can insist that the Church keep out of politics— that’s fine, I’m not a sadist. It makes my life easier— but notice how such insistence assumes that we’re in charge of the Church.

Though we spent three long years plotting to kill him, unfortunately for us Jesus Christ is not dead.

With Gestapo officers standing in the back of his lecture hall, spying on him, Karl Barth said:

“If Jesus Christ is only a pleasing religious memory, there will be nothing left of the church but a human community which is puffed up with the illusion that it has inherited the kingdom task all to itself—an illusion that works its own revenge upon the church.”

Most of the time, there, I think Barth’s describing the United Methodist Church, but Barth’s point is that Jesus Christ— God’s only chosen one— is not dead.

And the God we serve is Living God, a God who speaks and acts, a God who calls and conscripts. The God we serve is a Living God, a God on the move, a God who is able— able to do more than answer the items on your prayer list.

The God we serve is a Living God who is able to push and pull and prod and provoke his Church to go where it wants not to go.

In our sin, we can do our damnedest to keep politics out of the church, but can we, in our finitude, keep the Living God from dropping politics into our laps if God so elects? Are we able to resist the Risen Lord who persists in recruiting undeserving sinners like us into his labor?

———————-

I’m not being speculative here.

Having returned from vacation last Sunday, I arrived here at church on Tuesday morning, bright and early, with a long To Do list and my whole work week meticulously laid out.

Then our Lord, as he’s wont to do, messed up all my preconceived plans. He dragged politics into his church, and he strong-armed us into doing his work.

We were in the middle of a staff meeting.

A visitor buzzed the security intercom at Door #2.

“I need help,” she shouted into the speaker in hesitant, broken English.

Dottie, our secretary, buzzed her inside and showed her to my office to wait while we finished our work at the staff meeting. I figured if her request was illegitimate then she’d grow impatient with waiting and would move on to the next easy mark.

When we were finished with our work, I walked back to my office and discovered a woman about my age, neatly but simply dressed, with her black hair pulled back taut. Three children sat across the same sofa as her.

Their names, she told me, were Scarlett, Edward, and Denis— 6, 12, and 14 years old respectively.

I offered her my hand and introduced myself in my broken Spanish.

She introduced herself as Carolina.

“I was a teacher,” she said out of the blue and looking like she was struggling to get the English right.

I must’ve looked confused because she went on to explain, and what she told me wasn’t what I was expecting nor was it what I wanted to hear with such a busy week before me.

“We just arrived here,” she said, “last night. From Nicaragua.”

I still wasn’t processing her situation and it must’ve showed because she quickly added: “We left Nicaragua fifty days ago.”

“Porque?”

“My community very dangerous,” she said and wiped away tears, “I left— my home, my work— for them, for my children.”

And then, as best as she could, she told me about their journey, first by bus, then on foot, and finally stowed away in the back of a delivery truck.

Seeking asylum, they’d been separated and detained at the border and then eventually reunited and released on her own recognizance to report back at a later date.

She pulled a cell phone out of her back pocket and showed me the documents that corraborated her story, the first one stamped with her mug shot.

They arrived here on Monday and are now living in the basement of an acquaintance less than a minute’s walk from here.

Literally, a stone’s throw.

God apparently isn’t all that concerned with our concerns about keeping politics out of his Church.

“Do you have any food?” I asked her.

“No.”

“Do you have a job lined up?”

“No.”

“Do you have a lawyer— an abogado?”

“No.”

“What about your children— are they registered for school?”

She shook her head and appeared overwhelmed.

“What are you going to do?”

This time she had an answer.

“I prayed and I prayed all last night,” she said, and she’d suddenly stopped crying and looked both serious and euphoric. “I prayed and finally God spoke. He answered me, and God said to me to come here.”

“Here?”

She nodded.

“God said to me that he’d make you help us.”

“He did, did he?”

And she smiled and shook her head and said “Yes.”

She said “Yes” emphatically, like she’d just witnessed a miracle.

“Isn’t that just like God,” I muttered under my breath, “he knows I don’t have time for one more thing and so he sends you my way.”

“Como?” she asked, confused by my mumbling to myself.

“Nevermind,” I said, “it sounds like Jesus is determined for us to help you so what choice do I have?”

“None,” she said matter-of-factly, “no choice,” like it had been a serious question.

As though God had made me her hired hand.

———————-

Check out this parable.

Jesus would’ve known it. It was taught by the ancient rabbis before getting recorded and canonized in the Jewish Talmud.

“A king had a vineyard for which he engaged many laborers, one of whom was especially apt and skillful. What did the king do? He took his laborer from his work, and walked through the garden conversing with him.

When the laborers came for their wage in the evening, the skillful laborer also appeared among them and received a full day’s wage from the king. The other laborers were angry at this and said, “We have toiled all day long while this man has worked but two hours; why does the king give him the full wage even as to us?”

The king said to them: “Why are you angry? Through his skill he has produced more in two hours than all of you have done all the day long.”

Notice—

In the Jewish Talmudic parable, the emphasis falls on the exceptional worker’s economic productivity, but in Jesus’ remix of the parable, the stress is not on the laborer but on the landowner.

The focus is not on the worker’s activity but the owner’s activity, going out, again and again, seeking and summoning. The focus isn’t on the laborer’s contributions but on the landowner’s character, “Are you envious because I am generous?”

Actually, in Matthew’s Greek, the landowner asks the grumbling laborers, “Is your eye evil because I am good?”

Because I am good— that’s the money line; that’s the clue.

Right before Jesus spins his version of this parable, Jesus chastises a wealthy honor roll student for calling him good. “Good teacher,” the rich young man says to Jesus, “what must I do to have salvation?”

And rather than answer him outright, Jesus takes him to task for his salutation. “Why do you call me good? No one is good but God alone.”

No one is good, Jesus has just said, but God.

If you want salvation, Jesus then tells him, you’ve got to be free for it. Freed for it. Go, offload all your stuff on Craigslist and then come follow me.

In other words, whatever that word salvation includes it cannot exclude following and obeying Jesus Christ.

Follow me, Jesus invites the rich kid with the perfect resume.

But, Matthew reports (this was centuries before Marie Kondo), the rich young man had too much stuff in the way of following after Jesus so he turns around and turns away from Jesus and returns home.

He is the only person recorded in the Gospels who’s invited by Jesus to become a disciple but refuses.

And looking on the rich kid walking back home, Jesus says, “It’s hard for rich folks like him to follow me, about as hard as camel squeeing its humps and luggage through the eye of a needle.”

And the disciples, knowing they have more in common with the overachieving do-gooder than with the unemployed, homeless carpenter from Nazareth, throw up their hands, chagrined.

“Then there’s no hope for any of us!” they gripe, “If a success story like him can’t follow you and following you is salvation, then who can be saved?”

Jesus responds, “For mortals, it’s impossible. But for God, all things are possible,” which offends Peter, who gave up his fishing business— all on his own— to come work for the Lord and here Jesus is saying “Well, God will get even losers like this rich guy to ‘Yes.’ Watch, God will make followers of them too.”

“That’s not fair” Peter grumbles, and I get it. Trust me, no one has a beef with Christ’s poor taste in Christians quite like a pastor.

“That’s not fair,” Peter gripes.

So then Jesus doubles down with a redacted version of a familiar parable.

———————-

The denarius, which the landowner pays all the laborers, was the daily subsistence pay required by the Torah.

It’s prescribed in the Book of Leviticus. It’s minimum wage. It’s the equivalent of pulling a shift at Wendy’s. So the workers who show up just before quitting time— their pay is unearned, yes, but its not extravagant by any means. It’s not gratuitous; it’s what the Law requires.

This is not a parable of God’s grace as opposed to our works.

This is a parable about God’s gracious and determined work to enlist every last loser to his work. Like alot of the parables, this one is misnamed.

It’s not the Parable of the Laborers in the Vineyard. Heck, the laborers don’t do any labor onstage that we see at all. The laborers don’t so much as speak until they grumble at the very end.

No, this is the Parable of the Land Owner and his prodigal labor of summoning workers to his vineyard.

Nearly all the verbs in the story belong to him. He goes out— five times he goes out; he even goes out after there’s hardly anything left to be done— seeking laborers for his vineyard.

Jesus tells you the takeaway at the very top of the story.

“The Kingdom of God,” Jesus says, “is like a landowner who went out to find laborers…”

For his what?

For his vineyard.

Jesus assumes you know the Book of Isaiah where God’s self-chosen image for Israel and her vocation— her vocation to be a light to the world, to be a peculiar, set-apart, pilgrim people, to be a holy people, to be a nation within and among the nations, to be a people who embody— unlike the nations— God’s justice and righteousness— God’s image for his elect People and their vocation in the world is a vineyard.

It’s Isaiah chapter five.

God is the landowner who labors in this parable.

It’s about God’s work to find workers.

The primary difference between a Living God and a dead god, an idol, is that the latter will never shock or surprise you, never offend you or inconvenience you, and never call you to do something you wouldn’t have done apart from conversion and worship.

This parable—

It’s about this vocative God of ours.

This God who refuses to accomodate our apathy and functional atheism by remaining comfortably distant and idle but is instead always on the move, going out, inviting and enlisting, calling and conscripting, seeking and finding and arm-twisting Kingdom accomplices in a world that knows not that Jesus is Lord.

We can argue whether or not there’s any work we must do as Christians who are justified by grace alone, but the reality is that Jesus Christ is not dead and if he’s got a work for you to do, by God, he’s going to give it to you and he’s going to get you to do it.

———————-

I remember—

There was a young woman in one of the congregations I once served. Her name was Ann. She was a straight-A student at an Ivy League school.

She was nearing graduation, and her parents couldnʼt have been more excited about what lay in her future: maybe a graduate degree at another prestigious school; maybe a career and no less than a six figure salary.

Instead Ann threw them all for a loop and one day, out of the blue, announced to her parents that rather than doing anything they wanted, she was going to work in a clinic in some poor village in Venezuela.

I only found out about this when Annʼs mother burst into my office one day, clearly assuming I was the one who put the idea in her daughter’s head.

Red-faced and furious, she said: “Preacher, youʼve got to talk to her. Youʼve got to convince her to change her mind. Youʼve got to show her sheʼs throwing her life away.”

Ever the obedient minister, I met with Ann and communicated all her motherʼs fears: she was being naive, she was being irresponsible, she was being idealistic, her education should come first, she shouldnʼt jeopardize her career.

The Gospel’s about grace not works, I told her.

Ann looked back at me liked Iʼd disappointed her in some way. “Didnʼt Jesus tell the young man to give up all his stuff and follow him?” she asked.

“Uh, well, yeah but…I mean…Jewish hyperbole and all…he couldnʼt have been serious…that wouldʼve been irresponsible. At least tell me why youʼre doing this.”

“Why do you think?” she asked like there could be only possible answer and it should be obvious. “Jesus sorta came to me and he spoke to me and he told me to go and do it.”

“He did, did he?”

And her eyes narrowed, like she was about lay a straight flush down on the table.

“Are you telling me, pastor, that I should listen to you instead of him.”

“Um, uh…okay, I think we’re done here. Just leave me out of it when you talk to your parents.”

————————

I know you want to keep politics out of the Church.

I get it.

But the problem is, it’s not your Church and the Risen Christ, the Living God, he’s on the move. He’s always going out, calling and conscripting.

And he is free to drop whatever work he chooses into your lap whether or not it obeys our boundaries of what’s acceptable.

The Lord is no respecter of propiety. With pictures of asylum seekers all over the newspapers, God this week brought politics in to his church here.

And just like that, God got us to working.

Meredith, our Children’s Director, found games to occupy the kids while they waited. Peter put down what he was doing and left to stuff his trunk with food for them. And I stared at the fourteen items I had on my To Do list for the day as I waited on hold, making calls all day long for Carlina, connecting her with the county, finding her a lawyer, locating services, resourcing her three kids.

When we drove them home later, I carried bags of food inside and I gave her my cell number and I told her that if there was anything else she needed to call me. It was the sort of compassionate gesture you make to someone when you don’t really expect them to take you up on the offer.

Later that night I got a text from a number I didn’t recognize.

“This is Carolina,” it said, “thank you to you and your church.”

“De nada.”

And then I watched the text bubbles roll up and down as she texted another message. “The school say I need to go to Central Office to register my children.”

“How are you going to get there?” I texted back.

“I prayed,” she replied, “and God said you should take me.”

“He did, did he?”

“Si.”

And then the next text quickly followed.

“God say to tell you that I’m baptized. You have an obligation to me. As a brother. In Christ.”

“That’s the annoying inconvenience of worshipping a Living God,” I typed but didn’t send.

And so, thanks to Jesus, I spent most of the next day driving her and her children to Merrifield to get her kids registered and tested and immunized. And then the next day, Jesus apparently summoned my wife and son to go purchase school supplies for all of them.

———————-

At the end of the week, I mentioned all the details to Dottie, our secretary and she replied, “In order to be a pastor, you must have to really enjoy helping people in need.”

“Enjoy?” I asked, “Do you know many people in need? Most of them aren’t that enjoyable.”

“Then why did you choose to do it?”

“Choose? I didn’t choose it at all. I got summoned.”

Follow @cmsvoteup

August 23, 2019

Episode #222 — Mike Lyon: I’m Not Hitler

For #222 of Crackers and Grape Juice, Teer and I talked with Mike Lyon about his new book, a Christian apology, entitled I’m Not Hitler.

For #222 of Crackers and Grape Juice, Teer and I talked with Mike Lyon about his new book, a Christian apology, entitled I’m Not Hitler.

If you think religion is equal to the tooth fairy and Bigfoot, and have been turned off by church, dive into I’m Not Hitler. We all have a death sentence in this life, but do we need to make a decision to play in the next one? I’m Not Hitler explores the mystery and apathy of how a person gets to heaven. In a salty discourse, author Mike Lyon discusses whether a person can be good enough to step through the pearly gates. With plenty of personal anecdotes, the book challenges the broad assumptions that religious, spiritual and non-religious people often conclude.

Fans of the sass of Anne Lamott, David Sedaris and Brené Brown, may find the discourse entertaining. If you’re a Christian and unsure how to discuss God with your friends, the book will be helpful.

Can a person simply pick a religion and do their best? What about a spiritual buffet where the universe serves all you can eat? Who exactly are the bad people who will not enter the big party in the sky?

Find out from someone who believes in God, and listens to Iggy Pop and Johnny Cash while mixing David Mamet with Tim Keller.

Before you listen or while you listen, head over to our website, www.crackersandgrapejuice.com, and click on “Swag.” Now available for sale are our Stanley Hauerwas “Jesus is Lord and Everything Else is Bullshit” t-shirts. Also, if you sign up to become a patron of the podcast, we’ll send you a free “Incompatible with Christian Teaching” pint glass!

Follow @cmsvoteup

August 11, 2019

The Way of the Son in the Far Country

Luke 15.11-32

St. Luke reports the motive.

The Pharisees and the scribes were grumbling, Luke writes at the top of chapter fifteen. They were outraged: “This Jesus welcomes sinners— tax collectors, even, Jewish enablers of Israel’s imperial enemy. This rabbbi welcomes the very worst sinners among us.”

So Jesus, Luke says, told them three parables. The first about a lost sheep. The second about a lost coin. And then, a parable about a family.

The father said his son had wandered far off from how he’d been raised.

He’d wandered far from home.

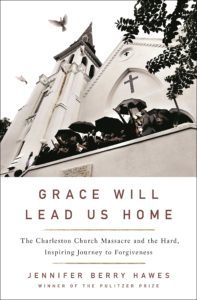

That’s what the father had told the tipline after the Charleston Police Department released Dylan Roof’s picture to the press just after six in the morning on June 18, already four years ago. The father called the hotline to identify the suspect as his son. The father warned them that Dylan owned a .45 caliber pistol, a gift he’d given his son for his twenty-first birthday.

But the son had taken the father’s gift and left home and was now living out of his black Hyundai, the father told the tipline, adding that they could identify the nondescript car by the confederate flag on it.

“My son’s gotten himself lost,” the father said, “obsessing over segregation and another civil war coming. I keep hoping he’ll come to his senses.”

He’d wandered and gotten himself lost.

The night before, aiming to ignite a nationwide race war, the father’s son crept into the fellowship hall of Emmanuel AME, an historically black church in Charleston. The pastor and eleven church members gathered there for Wednesday night Bible Study welcomed him and invited him to join them.

Seeing the stranger, Polly Sheppard, one of the leaders of the Bible Study, declared that “if our guest has come to Emmanuel in search of God, we will guide him to God.” She didn’t know he carried hidden in his napsack a Glock and eighty-eighty bullets— the number symbolic for “Heil Hitler.”

The class members pulled up a chair for him. They gave him a Bible. They offered him a spare copy of the study guide.

They prepared table in the presence of their enemy.

He joined them in turning to the Gospel of Mark, chapter four. They were in the middle of a Bible Study on the parables of Jesus. And he sat next to them and studied with them the Parable of the Sower as Mark tells it.

After an hour, a class leader named Myra read from their study guide: “In like manner, the seed of God’s word, falling upon a heart rendered callous by the custom of sinning, is straightaway snatched away by the “Evil One.””

Given their hospitality towards him, he almost changed his mind. But, while they all bowed their heads and closed their eyes to pray, he pulled his gun, quickly, as he’d practiced.

And then he wandered out, even more lost than when he’d come, as Felicia Sanders, one of the three survivors, wept Jesus’ name over and again.

You know the story.

Two days later Dylan Roof appeared before a magistrate in Charleston County’s bond court. Reporters, photographers, and cameramen filled the courtroom to cover the bail hearing. Cable news stations showed Dylan Roof as he entered escorted by a sheriff, wearing shackles and a gray striped jumpsuit.

As the black-robed and silver-haired judge announced the case, on the other side of the world, in Dubai, Steve Hurd, whose wife had been a victim and who was desperately trying to make his way home, stood up in an airport bar and pointed at the television screen and shouted: “That! That thing killed my wife!”

Before the bond hearing concluded, Judge James Gosnell read the names of the victims, carefully, one at a time. Having finished, he invited their family members to come forward to speak.

Nadine Collier, the youngest daughter of Ethel Lance, sat in the back and hadn’t planned to say anything.

Yet, when her mother’s name was read, she later said she felt herself rise. Something moved her to the front of the packed room, she said. And as she walked forward, she said she heard her mother’s voice warning her, “I don’t want any fast talking out of you today. Don’t be a smart-ass today.”

Nadine’s Mother, Ethel, had been the church’s custodian. Ethel had chided Nadine for her stubborness and incendiary sense of humor, but in the bond coutroom Nadine was determined that her words would be her mother’s words and her mother’s words had always been disciplined by the Gospel Word.

Nadine was so overcome by the Holy Spirit that when she stepped the microphone, at first she couldn’t remember her name.

“You can talk to me,” the judge told her, “I’m listening to you.”

Instead Nadine looked at the lost son and summoned what she knew her mother would’ve said to him:

“I just want everybody to know, to you, I forgive you! You took something very precious away from me. I will never talk to her ever again. I will never be able to hold her again. But I forgive you! And have mercy on your soul. You. Hurt. Me! You hurt a lot of people. But God forgives you. And I forgive you.”

And then she turned away from him and returned to her seat.

Next, a pastor, Anthony Thompson, came forward on behalf of his dead wife, Myra. A retired probabtion officer, he knew the bond hearing was only a formality so he hadn’t planned to say anything.

Like Nadine, the Spirit compelled him, he said later. He stood at the lectern, staring at Roof. In his mind, he said, it was as if everyone else had vanished and he was sitting alone with the killer in his jail cell.

In fact, Reverend Thompson spoke so softly the judge had to ask him to speak up.

“I forgive you,” the pastor whispered to him, “and my family forgives you, and we invite you to give your life to the one who matters the most; so that, he can change it, change you, no matter what happens to you.”

When Felicia Sanders heard her son, Tywanza‘s, name read by the judge, she said she felt God nudge her foward.

As she walked to the microphone, clutching a ball of folded-up tissues, she said she’d thought about how her baby boy was in heaven now and how Jesus says the Kingdom of Heaven is like a father who forgives his son who’d wished him dead. Therefore, she figured, forgiveness was the way she’d see her son again.

And so she said to the lost son who’d killed her son:

“We welcomed you Wednesday night in our Bible Study with open arms. You have killed some of the most beautifullest people that I know. Every fiber in my body hurts! And I’ll never be the same. Tywanza Sanders is my son, but he was also my hero! As we say in Bible Study: We enjoyed you, but may God have grace and mercy on you.”

Other family members spoke too. All of them echoed the same themes of God’s unmerited grace and forgiveness in Jesus Christ.

If you read Luke’s parable closely, it’s the gratuity of the grace that sets him off.

Whatever resentments the older brother was harboring, whatever anger lay buried inside him already— it’s the singing and the dancing and the feasting and the rejoicing that send him over the edge. Why shouldn’t it?

Ancient Judaism had clear guidelines for the return of a penitent. Ancient Judaism was clear about how to handle a prodigal’s homecoming. There was nothing ambiguous in Ancient Judaism about how to treat someone who’d abandoned and disgraced his family. It was called a ‘kezazah’ ritual, a cutting off ritual.

Just as they would have done when the prodigal left for the far country, when he returned home members of his community and members of his family would have filled a barrel with parched corn and nuts.

And then in front of everyone, including the children— to teach them an example— they would smash the barrel and declare, “This disgrace is cut-off from us.”

Having returned home, thus would begin his shame and his penance.

So you see, by all means, let the prodigal return, but to bread and water not to fatted calf.

By all means, let him come back, but dress him in sackcloth not in a new robe. Sure, let him come back, but make him wear ashes not a new ring. By all means let the prodigal return, but in tears not in merriment, with his head hung down not with his spirits lifted up. Bring him to his knees before you bring him home.

Celebration comes after contrition not as soon as the sinner heads home. Repentance is more than saying “I’m sorry” and forgiveness cannot be without justice. It’s the outrageousness of the forgiveness that outrages him. Here’s the thing: the eldest, he’s absolutely right.

It’s as if, in this parable, Jesus is after something different— something bigger— than what’s right.

One of the children of the Emmanuel Nine stood on the outside, looking in on their outrageous Gospel celeration.

Sharon Risher is Nadine Collier’s sister.

Of church custodian Ethel Lance’s five children, Sharon is the oldest.

She is the one who’d helped their mother care for her deaf brother. She is the one who showed up and did whatever needed to be done when Ethel’s second child, Terrie, struggled in a fatal battle with cervical cancer. She is the one who made their mother proud by being ordained and working as a trauma chaplain in Dallas.

Resentments still lingered between Sharon, the eldest, and Nadine, the youngest, from the fight that exploded between them at their sister, Terrie’s, funeral.

Sharon was still in Dallas, packing for a late flight to South Carolina, when the bail hearing came on the network news. Pacing her apartment and chain-smoking cigarettes, she heard her youngest sister, Nadine, mention their Mother— Ethel’s faith in the Gospel of Jesus Christ— before announcing in a quavering voice, “I just want everybody to know, to you, I forgive you!”

With her black horn-rimmed glasses pointed at the TV screen, Sharon watched from afar as other victim’s family members echoed her sister’s outrageous sentiments.

“What is going on?” she asked the television.

Nadine hadn’t told her about any bond hearing much less anything about any plans to offer up forgiveness for him— the police hadn’t even contacted her. While busy juggling her work and now her responsibilities as the family’s eldest, she just stumbled upon it on the TV.

“Why didn’t anyone tell me?” she wondered aloud.

When the news coverage of the hearing ended and the anchors marveled at the extravagant display of grace, Sharon felt infuriated. Not two days had passed. They hadn’t even buried their mother. She still hardly knew any details of what he had done.

Seeing their outrageous display of forgiveness on the TV screen, Sharon, Ethel Lance’s eldest, refused ever to join in.

“I’m the one who knows what should be done. How can you forgive this man?!” Sharon screamed the television.

When Sharon finally arrived in Charleston, she and her sister Nadine embraced, but the latter didn’t feel any warmth from the former.

None was intended, the eldest said.

Colloquial wisdom says that Jesus taught in parables so that the everyday rabble would better understand him. Clearly, whoever first made that argument hadn’t read many of Christ’s parables.

Surely though the members of the Bible Study at Emmanuel knew better. Likely, in their study guide on the parables of Jesus, they’d already encountered Jesus explaining to his disciples that the reason he taught in parables was so that the crowds would not understand him.

Jesus taught in parables— according to Jesus— not to make his teaching clear for the eavesdropping crowds but to confuse them. “To you,” Jesus says to his disciples, “it has been given to know the secrets of the Kingdom of God, but to them it has not been given.”

Jesus teaches in parables because the offensive, upside-down nature of the Kingdom of God is not for everybody to know.

Just anyone (who knows not Jesus) cannot possibly understand such a counterintuitive Kingdom.

You’ve got to see such a Kingdom before you can believe it— you’ve got to catch a glimpse of it.

The words need to find flesh.

Jesus teaches in parables because the parables aren’t for everyone.

Jesus teaches in parables because the parables are for the new family constituted by his call his call to baptism and discipleship.

Jesus teaches in parables that are unintelligible to the world; so that, Jesus’ disciples might then live lives that make intelligible the Kingdom disclosed in those parables.

That is, the parable Jesus gives to the unbelieving world is the parable that the Church tells by its becoming a parable— by exemplifying for the world what Jesus deliberately obscures from the world.

This parable at the end of Luke 15– it’s not a picture of a generalized, universal principle of forgiveness to which anyone can aspire.

We are meant to be the way of the Son in the far country of Sin and Death.

As Stanley Hauerwas says, a God who forgives sinners without giving them something to do is a God of sentimentality. This is why the lectionary always pairs Christ’s parable of the family with St. Paul’s second letter to the Corinthians:

“If anyone is in Christ [by baptism] there is a new creation: everything old has passed away; see, everything has become new! All this is from God, who reconciled us to himself through Christ, and has given us the ministry of reconciliation.”

Christ has given us the ministry of reconciliation.

Christ has given the ministry of reconciliation to us— not to Congress, not to POTUS OR SCOTUS, not to Democrats, not to Republicans, to us.

Christ has given us— the new family of the Father and the Son, created by baptism— Christ’s own ministry of reconciliation.

Christ has given it to us; therefore, it’s not simply something we should do or ought to do in order to get to Christ. We’re already in Christ. And Christ has given us his ministry of reconciliation; therefore, it’s something we can do— it’s something we get to do.

Karl Barth said one of the ways we’re hostile to God’s grace, one of the ways we contend against God’s grace is by not doing what we may and can do, for grace not only pardons; grace empowers.

Grace empowers us to live lives that make no sense if the one who told this parable of the family is not Lord.

Grace not only pardons.

Grace empowers us to live lives that corroborate the Gospel.

Grace empowers us to live lives that corroborate the Gospel because what God wants is not just your life but the whole world.

We are, as St. Paul says in that same passage, “ambassadors of Christ.”

The Living God, the apostle Paul writes, is determined to make his appeal through us, the particular, peculiar people called Church.

We’re the parable Christ communicates to the wider, watching world.

At the end of their testimony at Dylan Roof’s bond hearing, the Charleston police chief, Greg Mullen, said he sat in awe of how, with the world watching, God’s Church had rendered every reporter in the courtroom speechless, their jaws all hanging open, dumbfounded, amazed at grace.

Follow @cmsvoteup

August 9, 2019

Episode #220 — Will Willimon: Accidental Preacher

”As a preacher, I am in over my head on a weekly basis, saying far more than I know for certain, continuously bordering on blasphemy, risking, and fully exposed to contradiction and rejection. It’s a tough way to make a living, but it is the best living worth God’s making.”

Friend of the podcast, mentor, and muse, Will Willimon joined Teer and Jason to talk about his brand new (wondeful) memoir, Accidental Preacher. His answer to the last of the Ten Questions: Q: “Since heaven exists, what do you want to hear God say when you arrive?” A: ”I won’t like it, but it’d be just like God to say “Oh Will, welcome— the Trumps are right over there. They’ve been waiting for you.””

Before you listen, click over to www.crackersandgrapejuice.com where you can support the show by purchasing you’re very own Stanley Hauerwas “Jesus is Lord and Everything Else is Bullshit” t-shirt.

Follow @cmsvoteup

Jason Micheli's Blog

- Jason Micheli's profile

- 13 followers