Jason Micheli's Blog, page 96

November 26, 2019

Christian Politics — A Sermon by Stanley Hauerwas

By Dr. Stanley Hauerwas, Duke University

A Sermon for Annandale Methodist Church

November 24, 2019

Jeremiah 23: 1-6

Colossians 1: 11-20

Luke 23: 33-43

I do not know about you but I have found going through these last three years exhausting. One of the reasons I have found them exhausting is I have no idea what is going on. Or it may be I think it is obvious what is going on and I do not have the slightest idea what could be done to right the ship. Something seems to have happened to our world and few of us have any idea how to put in back together.

That I am a theologian should make some difference. I have spent a life time reading books that should give me insight into the world in which we find ourselves. For example consider this passage from Bonhoeffer’s Ethics:

“For the tyrannical despiser of humanity, popularity is a sign of the greatest love for humanity. He hides his secret profound distrust of all people behind the stolen words of true community. While he declares himself before the masses to be one of them, he praises himself with repulsive vanity and despises the rights of every individual. He considers the people stupid, and they become stupid, he considers them weak and they become weak, he considers them criminal and they become criminal. His most holy seriousness is frivolous play; his conventional protestations of solicitude for people are bare- faced cynicism. In his deep contempt for humanity, the more he seeks favor of those he despises, the more certainly he arouses the masses to declare him a god. Contempt for humanity and idolization of humanity lie close together. Good people, however, who see through all this, who withdraw in disgust from people and leave them to themselves, and who would rather tend to their own gardens than debase themselves in public life, fall prey to the same temptation to contempt for humanity as do bad people.”

Bonhoeffer wrote that sometime between 194l and 1943 while staying at the Benedictine Abbey Ettal. The secret seminary he directed had been closed by the SS and many of the young men he had trained had been drafted only to be sent to Russia. The passage I just read is obviously Bonhoeffer’s reflections on Hitler and the Nazi takeover of German life. That it is so may mean it is not relevant for our situation because being ruled by a bore is not the equivalent to being ruled by a totalitarian murderous thug. I suspect, however, it is all too relevant to our situation.

I am aware that to begin a sermon with these kind of reflections risks offense. I am visiting preacher. I will say what I have to say and then get out of town. I do not have to pay any price for a sermon, and some may wonder if it is a sermon, that seems far too political. But then I hope to convince you that one of our failures as Christians has been our unwillingness to acknowledge and preach the politics of the cross.

There is also the problem of using a sermon to support or criticize particular political opinions. I obviously am not a big fan of Donald Trump while many of you may well think him as inspired leader for our time. Yet you do not get your view in play because I am in the pulpit and you are in the pew. I win.

Of course we try to avoid acknowledgment of the politics of preaching by underwriting the dogma that religion and politics do not mix. It is assumed my negative view of Trump and those with more positive views should keep those judgments to themselves particularly when they are in church. The only problem with that strategy, which I take to be an attempt to avoid conflict, is the importance of recognizing that few claims are more political than the phrase “religion and politics do not mix.”

That is particularly true when the attempt to keep politics out of the sermon is reinforced by the distinction between the public and the private. Most of us are well schooled by the general presumption that religious convictions are “personal” or “private.” “Private” means it is not incumbent on anyone else to believe what I believe.

That commitment is assumed to take the politics out of religion. Of course as the great historian, Herbert Butterfield, observed some years ago there is usually enough conflict in any church choir to start a war. But that is a politics internal to the church . No one, moreover, takes such a politics seriously. The only problem with the relegation of religious convictions to the private means is that when what we believe is so understood what we believe is seldom thereby thought to be true.

By now I may have tested your patience to the breaking point. You came to hear a sermon and what you have gotten seems more like a lecture about religion and politics that you can well do without. Where is the good news in these problematic generalizations about the relation of the church and politics?

Here is the good news—“There was also an inscription over him, ‘This is the King of the Jews.” Today we celebrate the feast day of Christ the King. It does not get more political than that. The temptation, of course, is to use the language of kingship to make the cross a religious symbol that has no political implications. We are after all Americans. We have never had a king or queen and we have not seemed less for not having monarchs. Was not the War of Independence fought to free Americans from the reach of a king?

We are in the generic sense democrats. Democracies do not have kings. At least they do not have kings that actually rule. We are, moreover, a liberal democracy which is dedicated to the project of making each of us our own tyrant. To be an American means you have to do what you want to do.

Jesus may have been a king but we will not be ruled by a king. We will not be ruled by a king or queen unless we have learned to live as if we are each a monarch of our lives. Yet the desire for freedom without limitation leads, as Bonhoeffer’s analysis presupposes, to servitude.

But this is Christ the King Sunday. If Christ is king it must surely be the case that there is no way to avoid the fact that there was and still is a politics in play that climaxed in his crucifixion. The one who tempted him in the desert was revealed in the crucifixion as the false ruler that tempts us to be more than creatures of God’s good creation.

It is not accidental that the feast day of Christ the King was established by Pius XI in 1925 in his encyclical Quas primas. Pius was so concerned by the murderous reality of WWI he reasoned that the only hope of avoiding future conflicts depended on the public recognition and celebration of “Christ the King.” We become a people incapable of killing one another through the recognition that Jesus is king.

To be sure the politics we experience are democratic. It is also true that there are few examples of the politics of democracy in the Bible. Jesus is nowhere addressed as “Mr. President.” Nor does he seem to be someone who might try to win an election. Take up your cross and follow me does not sound like a winning campaign slogan. I concede that there is one democratic moment in the Gospels—the people choose Barabbas.

I think the problem of articulating the politics of the cross in modernity is not because we are stuck with kingship language in a democratic social order. No, I think the problem is Jesus. In Colossians we are told “He is the image of the invisible God, the firstborn of all creation; for in him all things in heaven and on earth were created, things visible and invisible, whether thrones or dominions or rulers or powers—all things have been created through him and for him.” All things have been created through him—dominions, rulers, or powers.

What are these “powers?” They are givens of God’s good creation that were meant to make our lives possible. But they are fallen giving us the illusion that we are in control of our lives. They were meant to make us cooperative and at peace with one another but they are now used to assert our will over each other.

But they have been exposed and thus redeemed by Christ making it possible for us to live in peace. What does it mean to say they are redeemed? It is to say that the pretention that we are our own creator has been unmasked by the cross. It is to say that if there did not exist a people who worship a crucified king then the world Bonhoeffer describes is never far from reality.

Christ is king. Christians accordingly must be the most political of all God’s creatures but our politics is not “out there.” Our politics is first and foremost here in this bread and wine. Here we become for the world a people of peace in a world of violence. Such a people are made possible by the forgiveness of sins. Forgiveness makes possible the acknowledgment that we can confess the sins of the past without trying to justify what was so wrong nothing can make it right. Slavery was sin.

There can be no question for us who worship a crucified savior—religion and politics do mix. Indeed they do not mix but in fact they are one. There is no politics deeper than the community that is gathered around the cross of Christ. For it is assumed such a community has nothing to lose by acknowledging the truth about our failures to follow this Lord is about truth.

We live in a dangerous world made more dangerous by our unwillingness to obey anyone other than this strange king of the Jews. Do not be afraid but rejoice in the fact that you are a citizen of the kingdom of this crucified king.

Follow @cmsvoteup

November 22, 2019

Episode #235– Parker Haynes: Is the Future of Methodism, Anglican?

Our guest this week is United Methodist pastor Parker Haynes who joins us to talk about his essay “Remember Our Story: Is the Future of Methodism, Anglican?” in which he argues that United Methodism has run aground not because of disputes over sexuality but because, in many core ways, the story of Methodism has come to an end. Our reason for being, that is, is no longer a reason to be a distinct set apart from the Church whence we came.

Our guest this week is United Methodist pastor Parker Haynes who joins us to talk about his essay “Remember Our Story: Is the Future of Methodism, Anglican?” in which he argues that United Methodism has run aground not because of disputes over sexuality but because, in many core ways, the story of Methodism has come to an end. Our reason for being, that is, is no longer a reason to be a distinct set apart from the Church whence we came.

Here’s Parker’s piece here:

Does our future as United Methodists lie in returning to the global Anglican communion whence we came?

Here’s a reflection that comes to us from a friend of the podcast, Reverend B. Parker Haynes:

As The United Methodist Church has been consumed by an idolatrous focus on sex over the past decade, the Church has failed to see that in a few years this conversation will be null and void. The future of The United Methodist Church is in doubt, not because it is considering moving from an orthodox position of sexuality to a heretical one (the traditional view), or because it has oppressed LGBTQIA Christians and its position on sexuality is antiquated, patriarchal and hetero-normative (the liberal/progressive view). Instead, I offer that the future of our Church is in doubt because we have forgotten who we are. That seems like an overly simplistic and naive statement that cannot possibly get at the heart of the issue. But let me suggest that the central reason we are where we are is because we can no longer identify what it means for any of us to be a distinctly United Methodist Christian. What is at stake in the 2020 General Conference and beyond is not whether we will take a traditional or progressive position on sex, but whether or not we can reclaim our story as United Methodists.

The Church in the Modern Age: A Story Forgotten

Perhaps the most significant reason we have forgotten our story is because of the rise of modernity. Former United Methodist and now Episcopalian theologian, Stanley Hauerwas, has said that the project of modernity is an attempt to produce a people who have no story except the story they chose when they had no story. In other words, modernity is an attempt to convince people that since we are rational, enlightened and autonomous individuals, there is no story, no narrative and no tradition that determines our lives except the one we choose for ourselves. Yet despite modernity’s attempt to be story-less, it too is a story. Modernity did not arise out of darkness ex-nihilo; it is a tradition that traces its roots to Christendom. But it is a story and a tradition that is false because human beings do not get to make up their own story; we have been “storied” through being formed as a community called the Church. We have been created, redeemed and sustained by the Holy Trinity. Our past, present and future have already been decided for us.

Ronald Beiner has sought to articulate the way liberalism, which is produced by modernity, has been able to convince us that we are a story-less people whose only identity is the one we create for ourselves. In his book “What’s The Matter With Liberalism?” he argues that in liberalism, we cannot distinguish between what is good and what is bad because human beings are reduced to individual consumers in which the freedom to choose is itself “the good,” meaning the true way of living our lives to the fullest. Therefore, nothing should restrict my freedom to choose how I live my life, including my own sexual preferences.

At first glance, this seems to be a traditionalist victory in the opening skirmish. But the problem is that liberalism is the air we breathe; we are all liberals. We all make up our lives believing we can define for ourselves what it means to be Christian. Conservatives, traditionalists, progressives and liberals all live in what Charles Taylor calls “The Age of Authenticity.” No one can tell me how to live my life or what to believe. In order to be authentic to who I am, I must figure those things out on my own. Even those of us who claim orthodoxy and submit to the Church’s teachings and the Book of Discipline first came to this understanding through a liberal trajectory. Traditionalists, like progressives, choose the ethics and biblical interpretations that fit their narrative rather than a wholesale subscription to historic orthodoxy. The reality is that we cannot go back to the pre-liberal, pre-modern era. To believe that we can defeat liberalism and reestablish the traditional values of the premodern church is exactly to believe the lie of modernity. We are not in control, we do not make up our lives and we cannot go back in time.

Virtue As A Way to Remember Story

This is not to say that all is lost. The true liberation of our enslavement to liberalism is not tighter restrictions, or more rules about who can do what as the Traditional Plan lays out. Liberation will only come through a return to the practice of virtue in the Church. As Christians, it is Jesus Christ through the Holy Spirit who unites us into a common life and has given us shared practices that compose our fundamental identity as a whole, which we call the Church. The penalties and restrictions of the Traditional Plan cannot form us into a common life because we no longer acknowledge or render authority to the Church as our common life. One of Methodism’s best theologians, Stephen Long, professor of ethics at Perkins School of Theology, has done much critiquing of liberalism, but has also noted that the Traditional Plan turns the Church into a nation-state that attempts to enforce laws, which are then enforced by authorities. However, the Gospel of Jesus is not a coercive message that forces others to believe in God; it is a persuasive one that seeks to articulate God’s love for the world. We cannot participate in a common life together through coercion. Relearning virtue, on the other hand, can reconstitute us as a community with shared practices that united us as the Body of Christ.

Aristotle first articulated the idea of virtue thousands of years ago in Athens. For Aristotle, the virtues were the practices that held together the common life of all Athenians. Rather than trying to determine how you would act in a certain situation (the starting place for most modern ethics), Aristotle believed you should focus on developing character through habituated excellence (virtue) that would give you the skills necessary to act rightly in that situation. Furthermore, this character would help you to lead a truly good life, good not only for yourself as an individual, but good for the community as a whole. For Aristotle, the individual and the community did not have a different telos, as if what is good for me is not necessarily good for all, but rather what is good for me is good for all and vice versa. Thus, our chief end is to develop the kind of character through the practice of the virtues so that, rather than competing against one another through violence, we might engender a common life together.

In modernity, we do not live in a world that values virtue, much less one that cultivates it. Such a statement is proof since Aristotle had no conception of “value” as we use it today. That we use the word “value” to describe the things that are important to us demonstrates that modernity has created a world in which everything can be seen as an investment that has a price and can be bought and sold as a commodity in a liberal market economy. Thus we cannot even begin to return to virtue unless we, The United Methodist Church as a whole, can form the kind of habits that will produce people who can articulate that rather than being creators of our own story, we have been storied through the tradition of the Church of Jesus Christ. We did not make ourselves Christians, we were made by others. We did not make up the tradition, we received it from others. Our belief in God is not an individual choice that gives meaning and value to our life. Instead, since God raised Jesus from the dead, we cannot do anything but believe and live in the community of saints.

Formed Through Liturgy

In order for us to cultivate virtue that will allow us to engender a common life as the community of saints, we need to first develop habits that will lead to the development of virtue. I suggest that these habits must be most significantly developed through our worship. James K. A. Smith has written extensively on worship as the arena through which our desires are properly shaped and directed toward God. There is no more effective habit-producing mechanism than liturgy. Liturgy is not only found in the Church’s worship, but everywhere from an NFL football game to a presidential address at a U.S. military base to a concert of a popular rock band. The liturgy found in the Church’s worship as the gathered Body of Christ centers around the eucharistic table to consume the Lord Jesus must be the liturgy that habituates us, shapes our desires, and lays the foundation for our story as United Methodists.

Unfortunately, in The United Methodist Church today, a majority of us have forgotten why the celebration of the eucharist is central to our community. Liturgy is a bad word in some congregations, and at the very least an outdated term that will hinder church growth. It is argued that today our worship needs to be relevant, entertaining, or a “fresh expression,” not boring, old or traditional. Most of our churches continue to celebrate the eucharist only once a month even though modern transportation has long allowed ordained clergy to lead worship every Sunday. When we shape our worship to be exciting, entertaining and only occasionally include the eucharist, we are creating habits that shape our story as a people who worship the god of modernity who caters to individualistic desires and provides optimism in a world of suffering.

One possibility of cultivating the kinds of habits through worship that would develop virtue might be to emphasize services of Word and Table with weekly communion. I would also suggest an emphasis on the Book of Worship or the Book of Common Prayer as a whole as a way to pattern our worship. Although it has been argued that one of the beauties of Methodism is our diversity in worship and style, I would argue that is an attempt to allow entertainment or excitement to form us. In actuality, there is much flexibility and room in the liturgy and a service of Word and Table can be adapted to appropriately reflect culture or the season of the year.

A counter argument might be that more liturgical traditions like Catholicism or Anglicanism are suffering decline similar to The United Methodist Church, and we must not be foolish enough to think that we will instantly be sucked out of our denominational struggles. Modernity and liberalism have formed us so deeply that it will be a long and difficult journey home and we will lose many along the way. But if we can develop the habits and virtues the early Church once had, maybe when we get to the end of all this chaos, we will at least be formed enough to know how to move forward and where the God of Jesus Christ is calling us.

The Future of Methodism: Returning to the Fold

As Methodists, we rightly celebrate John Wesley as the leader of our movement. Despite the number of references to Wesley today among Methodists, we forget many of the most important aspects of his ministry. Wesley remained an Anglican priest until he died and never wanted to start a new church outside of the Church of England. His intent was to reform the Church and reinvigorate it with the Holy Spirit. The question must be asked: When will the reformation be over? Where we stand today, we have lost more than we have gained. For most of our Methodist Christians in America, our Anglican heritage is unknown. Our distinctive theological emphases, worship practices, ecclesiology and social ethics are so muddled that most of our seminary students should not pass board examinations, but they do because of our growing need for clergy. How many of us can articulate what is it that makes Methodists distinct from Anglicans? In what ways are we more aligned with the Spirit, faithful to God’s call or ethically pure? We have lost sight of Wesley’s vision and forgotten our story as Methodists.

Our future lies in returning to the fold of the Anglican Communion. This does not mean that we must abandon all Methodist distinctives or emphases; we can seek ways to rejoin the family that allow us always to remember our heritage. But we can no longer remain separated and divorced from the Church that birthed us. We have forgotten our story because in many ways it has come to an end. Many of our protests against the Church of England have been heard and acted upon. There is no reason to continue protesting when the reforms have been conceded. Wesley never desired for us to exist as an end unto ourselves. It may be argued that the Episcopal Church has suffered a church split and declining membership so why would a move toward liturgy and unity better our chances? If our greatest need is numbers and increased church membership, then unity will not help. But if our greatest need today is remembering our story, who we are and why we began, then unity is the only answer.

Follow @cmsvoteup

November 19, 2019

The Church is Where We Die to Our Goliaths

Here’s a sermon on 1 Samuel 17.1-11, 32-51 and Revelation 12.7-12 from my intern David King, a student at Haverford College.

Here’s a sermon on 1 Samuel 17.1-11, 32-51 and Revelation 12.7-12 from my intern David King, a student at Haverford College.

I remember sitting in Sunday school some years ago and hearing the David and Goliath story for the first time. I’m sure most of you remember it too. It ran something like this:

David was a little shepherd boy working for his father. He’s the underdog that everyone can root for. He’s a good boy who follows the law. He is the youngest of the sons of Jesse. He’s the unlikely one of the bunch, handsome and ruddy, small and unassuming in stature. You get the picture.

The Sunday school teacher described the meaning of the story in three steps. 1) David was chosen and went to the river to get five stones. 2) “David is like you,” he said. “God has given you great gifts.” 3) like David, he went on, if you use those gifts, you can defeat your Goliath.

As the saying goes, God sometimes puts a Goliath in your way so you can find the David within you. Thankfully, I had the great advantage of not having to look far to find David.

Point is, much like me, my namesake isn’t the center of the story. In the ancient church, David was interpreted in light of Christ, as what St. Augustine calls a ‘prefiguration.’ This means that what occurs in David is an imaginative advance of what is accomplished in Christ. David is the vessel by which the good news is communicated. What my Sunday school teacher missed was not that David was a sinner, though the curriculum skipped over that for the most part as well; no, what my Sunday school teacher missed in the telling of the story, in the centering of David in the narrative, was Jesus.

That the early church was committed to understanding the story of the Hebrew scriptures as the same continuous revelation of Christ meant that they were also committed to a rather creative reading of the text. If the Hebrew Scriptures were gesturing towards the fullness that is the Son of God, then they supposed that it could not be referring to our action. That is, David was never viewed or interpreted as a person we were capable of emulating, who was faithful to God, who lived a good life, who did all the right things and followed through when the time came. He was not a moral example. David stood in as a characterization of what occurs in Christ.

The early church understood the opposition between David and Goliath to be an opposition between Christ and humanity in its captivity to sin. The valley into which David descends to face Goliath is interpreted as Christ’s descent into hell. He wrangles the devil, kills the death that holds us captive, and opens to us the life in him. The battle of Revelation that is our second scripture is played out in the Davidic narrative.

Now, bear with me here. Let’s go through the story again. Let’s listen to what the early church might have heard: Goliath, the giant of the time, the dominating force in geopolitics, decked out in the latest and greatest of armor and weapons, challenges the Lord and his people Israel. He presumes to be God. Goliath, you might begin to recognize, is a lot like us. Goliath does not mince words: he is here to deny God’s presence and covenant, for as he says, “today I defy the ranks of Israel,” today I “curse David by my gods.” David, the prefiguration of Christ, remains unmoved. He announces Goliath’s defeat even before he approaches the battlefield, saying to Saul that “the battle is the Lord’s.” David descends into the valley of death in order to meet Goliath head on – just as Christ condescends in the flesh to deliver us from the death that holds us captive. The stone David launches at Goliath is the proclamation of the Gospel – Christ knocks Goliath off his feet with the full message of God’s steadfast determination to disallow Death a victory.

With that stone, David denies us the ability to identify with him. The stone he throws is “the stone the builders have rejected that has become the cornerstone.” David, the early church saw, was to be identified with Christ, not ourselves. David knew that Israel needed to be saved.

Like it or not, we don’t need more Goliaths. We don’t need more Goliaths because we already have more in common with him than we do with David; we don’t need more Goliaths because we can already see ourselves in him. We defy God everyday. We sin. I mean, we armor ourselves with language and structures of security and its corresponding violence. Everyday, we praise the gods of this world, giving them the honor and glory that only Christ deserves. Everyday, we make the mistake of thinking ourselves to be a David, when the reality is we are a Goliath, to our neighbors and to ourselves. How we treat our neighbors deeply how we treat God, and who among us can say that they have truly loved each and every one of their neighbors?

Let me put it bluntly: the Revelation scripture today, through which we read the narrative of David, declares in unrelentingly militant terms that Jesus is Lord and that the powers of this world have been overcome. Goliath has been defeated, struck dead by this truth. The grip of sin on the world is no longer; Jesus has taken the violence that orients our lives and thrown it on its head. David’s act prefigures Christ in the radicality of its claim: there is but one Lord, and it is God.

In 1916, Karl Barth declared that the church should not be a place of refuge, but rather a place of disturbance and crisis. This is not because God is not our shelter in a time of storm; it is not because God does not care for us in our weakness. The church is a place of disturbance and disruption precisely because of the Lord it proclaims. The church is the place that witnesses to the overcoming of the powers of the world that is found on the cross and in the empty tomb. The church ,constituted through its word and sacraments, is where the world is reminded that its violence will not be returned with violence but with the truthful speech of the grace of God.

The church is where we die to our goliath’s, where we die to ourselves. St. Augustine notes that Goliath’s forehead, being the only part of his body not covered in armor, notably does not have on it the sign of the cross; that is, Goliath has, in all his armor, left himself vulnerable to the truth of the Gospel message, and it smacks him in the face. The church is where we hear the Gospel that reminds us, ever so gently as a rock to the forehead, that in our armor of the world we have indeed sinned and fallen short of the glory of God.

However, as Revelation declares, this stone is also the stone that gives us new life, for in it “the accuser of our comrades has been thrown down.” In this watery death, the death inaugurated by “the blood of the lamb,” we are invited into the life that is Christ Jesus. The baptism we share wraps us into the truth that sets us free. That is, our baptism is into death, setting us free from the clinging to life that is the narrative of this world. We can, therefore, truly proclaim the goodness of God, we can rejoice with all the heavens because we have been released from captivity to sin. We need not cling to life anymore, even in the face of death, because God in Christ has thrown down the great Dragon that accuses us before Him.

Apart from God, we are resigned to the woe of the earth, to the devil’s wrath, to the self-absorption and endless failure of pretending to be God. Without Christ Jesus, we are liable to identify ourselves with David, rather than with Goliath. Without the God who descends in Christ and is crucified on our behalf, the kingdoms, empires, and nations would have final say in our allegiance.

For apart from God, David reminds us, we have no hope. There is no sword or power that can overcome the Devil: it is the blood of the lamb and the proclamation, the speech, that overcomes.

Apart from the mercy of Christ and the truth of his freedom we are impotent to be ministers of the kingdom. David reminds us of this – he is not a glorious majestic figure in the story. The strength that ultimately defeats Goliath is not his own, for “the battle is the Lord’s.” In fact, David strips of all armour and safety, taking with him only the markings of a shepherd, the markings of that same shepherd who is nailed to the cross: he makes himself vulnerable to the violence Goliath wishes to enact because the Lord does not save by sword and spear. David, as the prefiguration of Christ, approaches Goliath with only the truth of the cross, the conviction that, truly, God does not return our violence with violence, but with the ever disruptive word of forgiveness and grace, the word of Easter.

David is denuded, made to appear naked in front of Goliath’s menacing figure. This nakedness is constitutive of a people who follow Christ, a people whose lives are marked by the truth of the cross. Revelation shows us that the time of the devil is short, because he has been thrown down by the cross. It is the cross on our foreheads and on our hearts that reminds us of the glory of God that makes us naked in the truth. No pretensions can be held. So, let us come, naked and free, to worship with Michael and all the angels, glorying in the forgiveness and love that is given to all creation by the blood of the lamb and the word of that testimony.

In the name of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit, AMEN.

Follow @cmsvoteup

November 18, 2019

On Becoming a Theologian of the Cross

A couple of years ago now, my wife, Ali, my mother, and I were sitting shoulder-to-shoulder in the mauve exam room where my oncologist had just handed me the results of my latest PET scan.

I’d finished my 8th round of chemo 7 weeks earlier, about a year after getting a call from a GI doctor who started by asking me if I was sitting down.

I’d been getting these double-over stomach pains for months.

The following day I was waking up from emergency abdominal surgery to my wife kissing my forehead and telling me they’d taken an 11×11 inch tumor from my intestine and that I had a rare, incurable cancer called Mantle Cell.

Just like Catniss Everdeen, the odds weren’t ever in my favor, and I thought I was going to die.

I’d staggered across chemo’s finish line like a runner who hadn’t practiced on enough hills.

“So…other than my… what am I looking at?” I asked with bated breath, holding my most recent PET scan in my hand.

“You’re as clear as a “bell”, my friend,” the doctor said, punctuating the news with a warm, knowing smile. “All the tumors you’d had all over you are completely gone.”

———————-

The chemo had killed off the cancer in my body, but we all knew I still had Mantle Cell percolating in my bone marrow, which, in the absence of the chemo treatment, would soon-to-eventually return lumps and masses throughout my lymph system.

“What the scan doesn’t show,” the doctor said, scooting the little round stool closer to us, “is the level of activity of Mantle Cell in your marrow. We’ll need to do a bone marrow biopsy for that.”

The reality that the cloud of cancer would never be completely removed from my body or our lives reasserted itself and hung over us. We nodded.

“Knowing the level of activity in your marrow will help us to gauge how we approach your maintenance chemo over the coming years.”

“We’ll do it here in the exam room. We’ll drill down into the center of your hip bone and extract a couple of vials of marrow.”

“Come again?” I asked.

“Did you say drill?!”

“Yes, drill” he said, oblivious.

“And am I, like, awake during this drilling?”

“Yes, but you needn’t worry. You’ll feel only a quick, momentary discomfort.”

I nodded, calming down.

“Well, I do plan on giving you a prescription for oxycontin to take before you come in that morning.”

“Oxycontin? I thought you said it would be only a momentary discomfort?”

He didn’t reply.

‘Can I just go back to dying?’

He slowly drew a smile across his face and then threw his head back in what seemed with hindsight, less hearty and more a diabolical laugh.

————————-

I returned a week later for the bone marrow biopsy.

I held out my arm for the lab nurse to draw my blood work. “I almost didn’t recognize you,” she said, sliding the needle into me seamlessly, “for most people, after chemo, their hair grows back thick…”

“Very funny.”

The nurse drew the needle out.

“It looks like I’ll be back with you for your biopsy today.”

“Awesome,” I said and then shared with her how the oncologist had described it as a momentary discomfort only then to prescribe a dangerous opiate normally associated with right wing radio hosts and gin-slinging country club wives.

She smiled like a preschool teacher.

“You took it though, right?” looking at me, suddenly sober.

“I didn’t even fill the prescription.” I said, “I forgot.”

“This should be…memorable,” she said, putting a cotton swab and tape over the puncture in my arm.

“For you or for me?” I asked.

“Both,” she was back to smiling.

“What’s it feel like?”

She was putting labels on my vials of blood. “Some people scream.”

“Some? What about the others?”

“They usually pass out.”

“But what does it feel like? There’s no nerves inside the bone there so it can’t hurt, right?”

She was, I could tell, thinking about something, remembering.

She chuckled to herself softly, glanced over into the lab to see if her supervisor was listening and then said: “This one guy- he said it felt like a Harry Potter Dementor sucking his soul out of his rear end.”

I’m not sure why but that struck me as probably the most terrifying thing she could’ve said.

———————

Laying down on my stomach in my birthday suit, I squeezed the corners of the mattress. He pressed his large left hand on my back, in between my shoulder blades, pushing down on me, and grabbed a screw-shaped needle big enough to throw light off the corner of my eye.

“You’re going to feel a little bit of pressure,” he said euphemistically as he started to twist the needle down into my bone.

“You’ve got strong bones.” He grunted.

“That’s probably because I breast fed until I was 12.”

I heard the nurse giggle. He did too.

He wiped his forehead with his sleeve.

He was covered in sweat too.

The nurse squirted some water into his mouth like he was a boxer in the late rounds.

“Okay, are you ready?” he asked.

Just then it felt like a cord was being pulled deep inside me, from my heel all the way up my spine. My legs both kicked involuntarily, like I was a corpse with a last bit of life in me.

“Good,” he said, “now only 2 maybe 3 more times.”

When he finished, I stood up from the exam table, too tired even to pull my pants up. “You were right about that Harry Potter thing,” I said to the nurse breathlessly.

I was so sweaty that pieces of butcher paper were stuck all over my arms and face, like I’d just had the worst shaving accident in history.

The doctor patted me on the shoulder. “You’ve been through the fire, Jason. You’ve been through the fire.”

“Just like Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego,” I joked.

“Well, let’s hope there’s no lion’s den in store for you,” he said, patting me on the back.

———————-

My oncologist— it’s not his fault.

He doesn’t know the Bible all that well. He grew up a Methodist.

Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego— they’re not thrown into a lion’s den.

They’re made to suffer an oven.

A fire from which we get the word, holocaust.

What made the Babylonians unique among ancient oppressors is that, upon invading and conquering neighbor nations, they did not simply kill the best and brightest of their neighbors.

They exiled their enemy’s best and brightest back to Babylon and forced them to become Babylonians.

They gave them new names and new gods.

They made them pagans.

And, so Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego— they’re Jewish exiles, conscripted into the civil service under Nebuchadnezzar, the pagan King of Babylon.

They’re Jews, but the names with which they’re named by Babylon pay homage to Babylon’s pagan gods.

Shadrach (his Hebrew name had been Hananiah) is named for the pagan god of the moon.

Meschach (his Hebrew name had been Mishael) is named for the pagan god, Aku.

And Abednego (his Hebrew name had been Azariah) is named for the pagan god of wisdom.

You see— for Jews, for whom the first and most urgent commandment is “You shall have no other gods but the one, true God,” to bear the name of a false god is a grave sin indeed.

To carry the name of a pagan god is to expect that the true God has forsaken you.

Or, worse, it’s to expect that whatever suffering comes to you has been sent by the God you forsook.

In the story, Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego are denounced for refusing to submit to the gods of Babylon and, by implication, for refusing to submit to the authority of Nebuchadnezzar.

So Nebuchadnezzar orders the three exiles gagged, bound, and cast into a fiery furnace but not before the king instructs his men to crank the oven up to seven times its normal heat, and seven— you should note the surprising clue— is the biblical number for perfection or completeness and, thus, it’s a number that foreshadows the presence of God.

The furnace gets so hot that the heat obliterates the guards who come close enough to the fire to toss the prisoners inside but not Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego.

According to Daniel, King Nebuchadnezzar and his courtiers can see Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego in the fiery furnace, walking around, unbound and unburned.

What’s more surprising, the bystanders report seeing a fourth person there in the fire.

Shadrach, Meshach, Abednego and who exactly?

“The fourth has the appearance of a son of God,” the counselor reports to Nebuchadnezzar.

The story in Daniel ends with a typical Old Testament flourish when King Nebuchadnezzar, having brought Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego out of the fire, unsinged, throws off his former affections and declares: “…there is no other god like this Son of God!”

In other words:

There is no other god who meets us in the fire.

There is no other god who meets us in the crucible of suffering.

———————-

Here’s the thing— pay attention now:

Despite what so much of our God-talk implies, God is not the passive, inactive, fixed-point center of the universe to whom it’s your job, through prayer and piety, to grow closer.

Jesus Christ is not just a God who suffers for us, for our sins.

Jesus Christ is a God who suffers with us, with sinners like us— that’s what it means, as the Gospel promises us, for Jesus to be a friend of sinners.

God doesn’t just take on our suffering in Jesus Christ.

God joins us in our suffering in the Holy Spirit.

It’s not on you to grow closer to God.

God is already closer to you than you are to yourself.

No matter what you’re going through in you life, God is completely active and present in it.

That we don’t always perceive God’s presence in our troubles and suffering has less to do with God— even less with the strength of our faith— and more to do with where we think God is allowed to act in our lives.

We lay down all these laws about where God’s allowed to act in our lives. God can be present in our worship, we think, or God can work through Bible study or prayer.

We can find God, we think, in spiritual disciplines or in acts of service.

But in our desperation? In our doubts? In our anxiety or addiction? In our suffering?

Surely God’s absent in our suffering, we assume.

That we think God can only work in our lives through proper, pious channels but shows how we persist in construing Christianity as a religion of Law.

But, it’s a religion of the opposite.

It’s a religion of grace.

It’s ironic how we don’t expect to discover God in our suffering anymore than Peter and the disciples expected to discover a suffering God.

———————-

While I’ve not been burned or singed by flames, I do have the belly scars and the needle marks and the monthly nausea and the weekly panic attacks and the medical bills to prove to you that I am in the fire.

Here’s what Jason the Patient learned about the fire that Jason the Pastor didn’t appreciate.

Just as learning I had Mantle Cell meant mourning the loss of the life I had and the loss of the future I’d envisioned, so too— paradoxically— finding out that I hadn’t died (just yet) meant mourning the loss of the life I’d found living with cancer.

This surprised me.

As much as I wanted the nightmare called cancer to be over, I found a part of me grieving the news that I would (sort of) get my old life back. I found myself grieving the life I’d learned to enjoy with cancer.

What I had happened upon, without knowing it, is what the Protestant Reformers, starting with Martin Luther, termed a theology of the cross.

Bear with me now.

A theology of the cross is not the same as a theology about the cross.

A theology about the cross says “While we were yet sinners, Christ on his cross died for us.”

A theology of the cross says “My life was in ruins of my own making.

My marriage was blown apart. My job was lost. My self-image was shattered by shame. My diagnosis trashed all my hopes and dreams. I thought God had forsaken me. I thought God must be punishing me.

But God met me there in the crucible of my pain. God met me there in the crucible of my shame. God met me there in the crucifixion that was my suffering.

A theology about the cross says “This is how God in Jesus Christ saves you from your sin.”

A theology of the cross says “This is where the God who has saved you in Jesus Christ meets you.”

This is where God meets you in your own life.

In your suffering.

In your sin!

In your shame and your pain.

A theology about the cross says “Christ and him crucified has taken away the handwriting that was against you.”

A theoloy of the cross says “Jesus Christ joined me in my darkest moment when all I could do was stare at the handwriting on the wall.”

The God who condescended to meet us in the crucified Jesus never chooses any other means to meet us than condescension into our suffering.

That’s how Paul today can declare to the Philippians “I can do all things through Christ who strengthens me.”

Paul’s behind bars when he writes to the Philippians.

Paul thinks he’s about to be executed.

Paul can say “I can do all things through Christ who strengthens me” because the Christ who strengthens him is with him there in the fiery furnace.

Christ has joined him in his suffering.

The cross is not what lies at the end of Jesus’ journey.

For every one of us, the way to Jesus Christ goes through a cross.

The cross is not simply the message we proclaim.

The cross is the means God uses to get to us.

As sure as I’m standing here today, I met Jesus Christ in the crucible of cancer.

Or rather, Jesus Christ met me there.

And I’m not special.

Neither are Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego.

This is how the Living God works.

He meets us in the fire.

As my friend Chad Bird, writes: “The glory of God is camouflaged by humility and suffering, for our God likes to hide himself beneath his opposite.”

Bird just puts more politely what Martin Luther wrote in his Heidelberg Disputation where Luther said that Jesus Christ meets us so far down in the muck and mire of our lives that his skin smokes hot; that is, God condescends to meet us not as a needless accessory in the pristine and happy parts of our lives but in the steaming piles of you-know-what in our lives.

Blank happens we say, but a theology of the cross says wherever it happens, God happens, too.

———————-

When I first got the diagnosis of something for which I’ll never be in remission, I reminded my parishioners over and over again that “God is not behind this. God is not behind my cancer.”

The paradox of the theology of the cross, however, is that though God is not behind my cancer, God is behind my cancer.

That is, God is not behind my cancer in terms of culpability, but God is behind my cancer in terms of condescension, wearing my suffering like a mask or a wedding veil, real enough to bring Nebuchenezzar to his knees and declare, “There is no other god like this!”

I’d never foist my diagnosis an another, yet, at the same time, I’ve found God hidden behind it, present in what others might perceive His absence.

You see, how preachers like me so often speak of the cross is insufficient.

In the suffering Christ, God does more than identify with those who suffer, the poor and the oppressed. By his suffering, God in Christ does more than give us an example in order to exhort us into rolling up our sleeves and serving those who suffer.

No, God is to be found in our suffering.

While we so often wonder where God is in our suffering, St. Paul indicts as “enemies of the cross” anyone who insist that God isn’t in suffering.

Where we assume God’s absence amidst suffering, Paul implies that not to know Christ is not to know that in your suffering, God is hidden, present, and there with us.

Suffering isn’t a sign that God’s asleep at the wheel.

Suffering is the vehicle in which God drives you to his grace.

“Where is God in my suffering?”

It can be the worst question to ask because it implies God’s not present in our suffering.

But then again, “Where is God in my suffering?” can also be the very best question if you’re looking for where God is in your suffering.

Because’s he’s there.

Because the Son of God who joins Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego in the fiery furnace is the same God who meets you in your own suffering.

————————

In his memoir Mortal Lessons: Notes on the Art of Surgery, Richard Selzer tells of a young woman, a new wife, from whose face he removed a tumor, cutting a nerve in her cheek in the process and leaving her face smiling in a twisted palsy.

Her young husband stood by the bed as she awoke and appraised her new self, “Will my mouth always be like this?” she asks.

The surgeon nods and her husband smiles, “I like it,” he says. “It is kind of cute.”

Selzer goes one to testify to the epiphany he witnesses:

“Unmindful, he bends to kiss her crooked mouth, and I’m so close I can see how he twists his own lips to accommodate to hers, to show her that their kiss still works. And all at once, I know who he is. I understand, and I lower my gaze and back away slowly. One is not bold in an encounter with God.”

The doctor and the husband— they’d become theologians of the cross.

Follow @cmsvoteup

November 15, 2019

Episode #234— David Hunsicker: The Making of Stanley Hauerwas: Bridging Barth and Postliberalism

In the past half-century, few theologians have shaped the landscape of American belief and practice as much as Stanley Hauerwas. His work in social ethics, political theology, and ecclesiology has had a tremendous influence on the church and society. But have we understood Hauerwas’s theology, his influences, and his place among the theologians correctly? Hauerwas is often associated―and rightly so―with the postliberal theological movement and its emphasis on a narrative interpretation of Scripture. Yet he also claims to stand within the theological tradition of Karl Barth, who strongly affirmed the priority of Jesus Christ in all matters and famously rejected Protestant liberalism. These are two rivers that seem to flow in different directions.

In the past half-century, few theologians have shaped the landscape of American belief and practice as much as Stanley Hauerwas. His work in social ethics, political theology, and ecclesiology has had a tremendous influence on the church and society. But have we understood Hauerwas’s theology, his influences, and his place among the theologians correctly? Hauerwas is often associated―and rightly so―with the postliberal theological movement and its emphasis on a narrative interpretation of Scripture. Yet he also claims to stand within the theological tradition of Karl Barth, who strongly affirmed the priority of Jesus Christ in all matters and famously rejected Protestant liberalism. These are two rivers that seem to flow in different directions.

In this episode, theologian David Hunsicker offers a reevaluation of Hauerwas’s theology, arguing that he is both a postliberal and a Barthian theologian. In so doing, Hunsicker helps us to understand better both the formation and the ongoing significance of one of America’s great theologians.

You can find the book here.

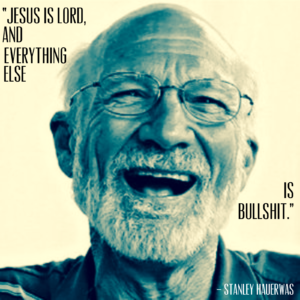

Before you listen, go to www.crackersandgrapejuice.com. Click support the show to become a patron of the pod, or check out our online store where you can get your very own Stanley Hauerwas “Jesus is Lord and Everything Else is Bullshit T-shirt.”

Follow @cmsvoteup

November 14, 2019

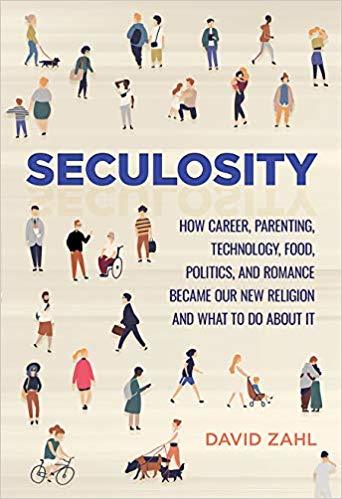

Christian Century Review — Seculosity by David Zahl

Here’s my review for the Christian Century magazine of David Zahl’s book Seculosity:

Here’s my review for the Christian Century magazine of David Zahl’s book Seculosity:

Last Halloween I lit some logs in the fire pit, put a chair in the driveway, and passed out candy to the many versions of Elsa, BB-8, and Captain America who crept up my sidewalk. We’d just moved to the neighborhood. Sometime after dusk gave way to dark, a neighbor ambled up to the fire. We’d exchanged pleasantries a few times before. Noticing the bumper stickers on our cars, we’d congratulated each other on both graduating from the University of Virginia. Otherwise, we’d remained strangers.

He offered me a postcard announcing a Dessert with Democrats gathering. “We’d love to have you there,” he said, and asked about placing some campaign signs in my “ideally positioned” front yard. When I demurred on using the parsonage lawn for political advertising, he spoke of the stakes come November.

“Thanks, really,” I tried, “I’m just not . . . I’m . . . independent.”

“Are you one of those evangelicals (the word sounded rancid on his lips) who voted for Trump?”

“No, I’m not an evangelical,” I said. “I’m just not that interested in politics.”

He looked stricken, as if I was sheltering Nazis in my basement or had stolen kittens from children. “I just don’t understand,” he said, shaking his head, “how a good person—like you seem to be—could not be invested in politics and making a difference.”

“I’ve just got a different religion,” I said.

If David Zahl is correct, this Halloween encounter with my proselytizing neighbor is a slice of all of our lives. Seculosity names the religion-saturated culture in which we find ourselves increasingly angry, judgmental, and exhausted. The religions we adhere to are no longer the conventional Sunday morning varietals. They’re religions grounded in our stances on politics, food, parenting, and leisure—areas of life which would seem to be secular.

The fact that worship attendance continues to decline and an increasing number of people check “None” next to religious affiliation does not mean that Americans are done with religion. “Our hearts are restless until they find their rest in God,” said Augustine, no stranger to shifting religious landscapes, and no matter what Gallup finds in its polling, Augustine wasn’t wrong. The restless quest for what only God can give, Zahl shows, continues apace and is expressed with the zeal and fervency of the newly converted.

The irony exposed by Seculosity is that while churches wring their hands at their dwindling numbers, “we’re seldom not in church anymore.” The many articles announcing the decline of religion in America are not so much wrong as myopic: they are looking to the places where religion once thrived instead of to the places where religiosity has migrated. As the ability of Christianity to shape people’s lives wanes, people turn to secular activities “to provide the justifying story of our life.”

Justify is the key term. Zahl is not arguing that our convictions about politics or our investment in an exercise class are forms of idolatry, although they may be. Rather, they are activities from which we’re unconsciously attempting to derive our ultimate value. Religion, as Zahl defines it, is “what we lean on to tell us we’re okay,” to impute to ourselves the sense that we’re enough. A seculosity is a religious striving for “enoughness” that is directed horizontally—to career, technology, or politics—rather than vertically to God. Because the religious impulse cannot be quenched, we pursue enoughness outside of the traditional vertical mechanisms. We do so to the detriment of our well-being and that of our neighbors.

A quick foray into any thread about politics on social media will illustrate Zahl’s point. Discussion quickly devolves into self-righteousness, judgmentalism, and anger. The horizontal dimension cannot supply what the heart is wired by its Maker to seek. Ever restless by design, we’re increasingly exhausted by default.

In A Secular Age, philosopher Charles Taylor explains the explosion of secularity as unwinding in stages, beginning with the Reformation and culminating in the late 20th century with the rapid diversification of alternatives to traditional belief. “We are now living in a spiritual super-nova, a kind of galloping pluralism on the spiritual plane,” Taylor writes. Using illustrations that are both funny and frightening, Zahl offers a kind of detailed ethnography of life in the spiritual supernova, that effulgence of religiosity that has followed the explosion of traditional religion.

The religious impulse cannot be quenched—only pursued outside the traditional places.

One effect of the supernova is that we’ve simply traded pieties. Whereas our predecessors could say, “I’m baptized,” we say, “I’m so busy,” and hope that the state of busy-ness is enough to justify our lives. Whereas ancient Christians apprenticed themselves to the saints, we count our exercise steps and Facebook likes to validate ourselves. We don’t pray to icons that serve as windows onto the divine, but we carefully stage and edit images for Instagram that will be windows for others to gaze upon a more perfect version of ourselves.

We might not believe any longer in a God who visits the sins of the parents upon their children, but we seem to believe that the achievements of our children will be reckoned as our own. Exhibit A is actress Lori Loughlin, who was indicted for using a bribe to get her daughter into a selective college. The language of righteousness strikes our ears as hopelessly archaic except when it comes to our political or other causes. We’re seldom reticent to excommunicate someone who commits heresy against our preferred ideology.

Seculosity shines its light upon on the conditional “if/then” construction of the promises seculosities make. If you eat organic and sustainably sourced food, then you will be enough. In the language of the apostle Paul and Martin Luther, the oughts and shoulds of seculosities pledge the very same promise that is at the heart of any religion based only on law. The promise is predicated entirely on our performance. Seculosities ultimately lead to exhaustion because we can never measure up to their ever-shifting standard of performance. They also lead to judgmentalism: the fact that we ourselves fall short of the standard doesn’t stop us from pointing out how others fall short.

By the conclusion of the book, readers are in on the joke of the subtitle “and What to Do about It.” Doing is exactly our problem. We’re busy producing, earning, climbing, proving, striving, and performing. We’re chasing our enoughness “into every corner of our lives, driving everyone around us—and ourselves—crazy.” The law is inscribed, Paul says, not just on tablets of stone but on every heart.

The remedy is to be found not in another exhortation about something we must do but in the proclamation of something that has been done for us. The conclusion of Seculosity is a contemporary companion to Luther’s thesis in the Heidelberg Disputation: “The law says, ‘do this,’ and it is never done. Grace says, ‘believe in this,’ and everything is already done.”

In other words, relief from all our replacement religions just might be found in the opposite of religion—the promise of the gospel. Unlike religions of law, Zahl argues, Christianity does not instruct us in how to construct our enoughness. The language of earning is antithetical to the gospel. Christianity rather invites us to receive our enoughness, which is Christ’s own enoughness, as sheer gift. Our Christian activities are the organic fruit of our enoughness, not the stuff by which we earn it.

Much of Christianity in America has been construed according to the if/then formula. The gospel of grace has gotten muddled with the law. On social media you can find Christians making pronouncements like “If your church isn’t preaching about the border crisis this Sunday, you need to find another church.” Pastors make promises about the spiritual transformation, deeper discipleship, or fruitful marriages that can be gained through the prescribed practices or simple steps their church recommends. The message from many pulpits in America boils down to either “You can build a better world” or “You can build a better you.”

“Whether the goal is personal holiness or social justice,” Zahl contends, “the same dynamic holds sway: faith serves as a means to end, a spiritual method of producing such-and-such result.”

As much as I agree with Seculosity, I have the nagging suspicion that my agreement stems in no small part from my identification with its author and the culture he describes. Like Zahl, I’m a fortysomething, relatively affluent white guy. The replacement religions he identifies are the familiar pursuits of my demographic tribe.

We are enough. Our Christian activities are the fruit of this fact, not the stuff by which we earn it.

Being a foodie is not cheap. Apple’s AirPods are as much conspicuous consumption as they are earphones. The boxing gym my teenage son attends works hard to appear authentic and costs a pretty penny to do so. By definition, only the well-off have the luxury of investing food and leisure pursuits with the significance of a religious performance.

I note this sociological fact not to criticize Zahl but to suggest that his argument may go even deeper than he admits. Paul writes in his letter to the Romans that the law increases the trespass, so it follows that seculosities would function not only as replacement religions but as vehicles for sin. That same letter indicates that an intractable feature of any religion is the propensity of its sinful adherents to make distinctions among people. We should not be surprised then that seculosities grounded in food interests, leisure activities, and parenting styles are not just secular outlets for religious impulses but secular ways to wage sin. They’re overt but socially acceptable ways to express how we’re superior to other—usually less affluent—people.

If the cultural landscape is rife with religions of law, and this religion surfaces even in the church, then perhaps the remedy is a return to the Protestant distinctives of “grace alone, faith alone, Christ alone.” Zahl writes in his conclusion:

The ultimate trouble with seculosity has nothing to do with soulmates or smartphones or tribalism or workaholism or even our compulsive desire to measure up. The common denominator is the human heart, yours and mine. Which is to say, the problem is sin. Sin is not something you can be talked out of (“stop controlling everything!”) or coached through with the right wisdom. It is something from which you need to be saved—even when the nature of sin is that it lashes out at that which would rescue it.

But one problem with the Protestant mantra of grace alone is that it can neglect the formation of a community of people who witness to God’s ongoing creation. As Stanley Hauerwas has argued, the gospel requires communities that perform the message being proclaimed. In that sense, performance need not be a bad word.

Furthermore, if people aren’t seeing around them a Christian community that plausibly invites them to perform their lives in the belief that Jesus has been raised from the dead, it’s more likely they will seek their righteousness in replacement religions. In a world without foundations, Hauerwas says, all we have is the church. To put it another way: in a world after the explosion of traditional belief, we all seek communities that make our lives and our religious impulses intelligible.

Over the past year I’ve gotten to know my neighbor down the street, and I’ve learned he’s more than the enoughness he gets through his political views. He’s a lonely man, and he also values the community he’s found in his political work. Through his progressive tribe he’s found friends who, he says, “just might show up when I’m about to die.”

As every pastor knows, participation in religion has as much (and usually more) to do with belonging as it does with belief. From what I can tell, communities built around CrossFit or politics can be better at building a community of accountability, challenge, and joy than many churches. Zahl, whose wonderful and nerdy first book was about rock music, can probably empathize with how people find secular communities of affinity to be vessels of communion.

As I finished Seculosity, I felt saddened by the thought that so many people are exhausted and unhappy in replacement religions because Christianity has failed to be for them a religion of grace. I also felt chastened to realize that some of my friends and neighbors are not unhappy with their new religion at all.

A version of this article appears in the print edition under the title “What is religion now?”

Follow @cmsvoteup

November 10, 2019

Remembering Our Story: Is the Future of the United Methodist Church, Anglican?

Does our future as United Methodists lie in returning to the global Anglican communion whence we came?

Here’s a reflection that comes to us from a friend of the podcast, Reverend B. Parker Haynes:

As The United Methodist Church has been consumed by an idolatrous focus on sex over the past decade, the Church has failed to see that in a few years this conversation will be null and void. The future of The United Methodist Church is in doubt, not because it is considering moving from an orthodox position of sexuality to a heretical one (the traditional view), or because it has oppressed LGBTQIA Christians and its position on sexuality is antiquated, patriarchal and hetero-normative (the liberal/progressive view). Instead, I offer that the future of our Church is in doubt because we have forgotten who we are. That seems like an overly simplistic and naive statement that cannot possibly get at the heart of the issue. But let me suggest that the central reason we are where we are is because we can no longer identify what it means for any of us to be a distinctly United Methodist Christian. What is at stake in the 2020 General Conference and beyond is not whether we will take a traditional or progressive position on sex, but whether or not we can reclaim our story as United Methodists.

The Church in the Modern Age: A Story Forgotten

Perhaps the most significant reason we have forgotten our story is because of the rise of modernity. Former United Methodist and now Episcopalian theologian, Stanley Hauerwas, has said that the project of modernity is an attempt to produce a people who have no story except the story they chose when they had no story. In other words, modernity is an attempt to convince people that since we are rational, enlightened and autonomous individuals, there is no story, no narrative and no tradition that determines our lives except the one we choose for ourselves. Yet despite modernity’s attempt to be story-less, it too is a story. Modernity did not arise out of darkness ex-nihilo; it is a tradition that traces its roots to Christendom. But it is a story and a tradition that is false because human beings do not get to make up their own story; we have been “storied” through being formed as a community called the Church. We have been created, redeemed and sustained by the Holy Trinity. Our past, present and future have already been decided for us.

Ronald Beiner has sought to articulate the way liberalism, which is produced by modernity, has been able to convince us that we are a story-less people whose only identity is the one we create for ourselves. In his book “What’s The Matter With Liberalism?” he argues that in liberalism, we cannot distinguish between what is good and what is bad because human beings are reduced to individual consumers in which the freedom to choose is itself “the good,” meaning the true way of living our lives to the fullest. Therefore, nothing should restrict my freedom to choose how I live my life, including my own sexual preferences.

At first glance, this seems to be a traditionalist victory in the opening skirmish. But the problem is that liberalism is the air we breathe; we are all liberals. We all make up our lives believing we can define for ourselves what it means to be Christian. Conservatives, traditionalists, progressives and liberals all live in what Charles Taylor calls “The Age of Authenticity.” No one can tell me how to live my life or what to believe. In order to be authentic to who I am, I must figure those things out on my own. Even those of us who claim orthodoxy and submit to the Church’s teachings and the Book of Discipline first came to this understanding through a liberal trajectory. Traditionalists, like progressives, choose the ethics and biblical interpretations that fit their narrative rather than a wholesale subscription to historic orthodoxy. The reality is that we cannot go back to the pre-liberal, pre-modern era. To believe that we can defeat liberalism and reestablish the traditional values of the premodern church is exactly to believe the lie of modernity. We are not in control, we do not make up our lives and we cannot go back in time.

Virtue As A Way to Remember Story

This is not to say that all is lost. The true liberation of our enslavement to liberalism is not tighter restrictions, or more rules about who can do what as the Traditional Plan lays out. Liberation will only come through a return to the practice of virtue in the Church. As Christians, it is Jesus Christ through the Holy Spirit who unites us into a common life and has given us shared practices that compose our fundamental identity as a whole, which we call the Church. The penalties and restrictions of the Traditional Plan cannot form us into a common life because we no longer acknowledge or render authority to the Church as our common life. One of Methodism’s best theologians, Stephen Long, professor of ethics at Perkins School of Theology, has done much critiquing of liberalism, but has also noted that the Traditional Plan turns the Church into a nation-state that attempts to enforce laws, which are then enforced by authorities. However, the Gospel of Jesus is not a coercive message that forces others to believe in God; it is a persuasive one that seeks to articulate God’s love for the world. We cannot participate in a common life together through coercion. Relearning virtue, on the other hand, can reconstitute us as a community with shared practices that united us as the Body of Christ.

Aristotle first articulated the idea of virtue thousands of years ago in Athens. For Aristotle, the virtues were the practices that held together the common life of all Athenians. Rather than trying to determine how you would act in a certain situation (the starting place for most modern ethics), Aristotle believed you should focus on developing character through habituated excellence (virtue) that would give you the skills necessary to act rightly in that situation. Furthermore, this character would help you to lead a truly good life, good not only for yourself as an individual, but good for the community as a whole. For Aristotle, the individual and the community did not have a different telos, as if what is good for me is not necessarily good for all, but rather what is good for me is good for all and vice versa. Thus, our chief end is to develop the kind of character through the practice of the virtues so that, rather than competing against one another through violence, we might engender a common life together.

In modernity, we do not live in a world that values virtue, much less one that cultivates it. Such a statement is proof since Aristotle had no conception of “value” as we use it today. That we use the word “value” to describe the things that are important to us demonstrates that modernity has created a world in which everything can be seen as an investment that has a price and can be bought and sold as a commodity in a liberal market economy. Thus we cannot even begin to return to virtue unless we, The United Methodist Church as a whole, can form the kind of habits that will produce people who can articulate that rather than being creators of our own story, we have been storied through the tradition of the Church of Jesus Christ. We did not make ourselves Christians, we were made by others. We did not make up the tradition, we received it from others. Our belief in God is not an individual choice that gives meaning and value to our life. Instead, since God raised Jesus from the dead, we cannot do anything but believe and live in the community of saints.

Formed Through Liturgy

In order for us to cultivate virtue that will allow us to engender a common life as the community of saints, we need to first develop habits that will lead to the development of virtue. I suggest that these habits must be most significantly developed through our worship. James K. A. Smith has written extensively on worship as the arena through which our desires are properly shaped and directed toward God. There is no more effective habit-producing mechanism than liturgy. Liturgy is not only found in the Church’s worship, but everywhere from an NFL football game to a presidential address at a U.S. military base to a concert of a popular rock band. The liturgy found in the Church’s worship as the gathered Body of Christ centers around the eucharistic table to consume the Lord Jesus must be the liturgy that habituates us, shapes our desires, and lays the foundation for our story as United Methodists.

Unfortunately, in The United Methodist Church today, a majority of us have forgotten why the celebration of the eucharist is central to our community. Liturgy is a bad word in some congregations, and at the very least an outdated term that will hinder church growth. It is argued that today our worship needs to be relevant, entertaining, or a “fresh expression,” not boring, old or traditional. Most of our churches continue to celebrate the eucharist only once a month even though modern transportation has long allowed ordained clergy to lead worship every Sunday. When we shape our worship to be exciting, entertaining and only occasionally include the eucharist, we are creating habits that shape our story as a people who worship the god of modernity who caters to individualistic desires and provides optimism in a world of suffering.

One possibility of cultivating the kinds of habits through worship that would develop virtue might be to emphasize services of Word and Table with weekly communion. I would also suggest an emphasis on the Book of Worship or the Book of Common Prayer as a whole as a way to pattern our worship. Although it has been argued that one of the beauties of Methodism is our diversity in worship and style, I would argue that is an attempt to allow entertainment or excitement to form us. In actuality, there is much flexibility and room in the liturgy and a service of Word and Table can be adapted to appropriately reflect culture or the season of the year.

A counter argument might be that more liturgical traditions like Catholicism or Anglicanism are suffering decline similar to The United Methodist Church, and we must not be foolish enough to think that we will instantly be sucked out of our denominational struggles. Modernity and liberalism have formed us so deeply that it will be a long and difficult journey home and we will lose many along the way. But if we can develop the habits and virtues the early Church once had, maybe when we get to the end of all this chaos, we will at least be formed enough to know how to move forward and where the God of Jesus Christ is calling us.

The Future of Methodism: Returning to the Fold

As Methodists, we rightly celebrate John Wesley as the leader of our movement. Despite the number of references to Wesley today among Methodists, we forget many of the most important aspects of his ministry. Wesley remained an Anglican priest until he died and never wanted to start a new church outside of the Church of England. His intent was to reform the Church and reinvigorate it with the Holy Spirit. The question must be asked: When will the reformation be over? Where we stand today, we have lost more than we have gained. For most of our Methodist Christians in America, our Anglican heritage is unknown. Our distinctive theological emphases, worship practices, ecclesiology and social ethics are so muddled that most of our seminary students should not pass board examinations, but they do because of our growing need for clergy. How many of us can articulate what is it that makes Methodists distinct from Anglicans? In what ways are we more aligned with the Spirit, faithful to God’s call or ethically pure? We have lost sight of Wesley’s vision and forgotten our story as Methodists.

Our future lies in returning to the fold of the Anglican Communion. This does not mean that we must abandon all Methodist distinctives or emphases; we can seek ways to rejoin the family that allow us always to remember our heritage. But we can no longer remain separated and divorced from the Church that birthed us. We have forgotten our story because in many ways it has come to an end. Many of our protests against the Church of England have been heard and acted upon. There is no reason to continue protesting when the reforms have been conceded. Wesley never desired for us to exist as an end unto ourselves. It may be argued that the Episcopal Church has suffered a church split and declining membership so why would a move toward liturgy and unity better our chances? If our greatest need is numbers and increased church membership, then unity will not help. But if our greatest need today is remembering our story, who we are and why we began, then unity is the only answer.

Follow @cmsvoteup

November 8, 2019

Episode #233: Matthew Bates — Gospel Allegiance: What Faith in Jesus Misses for Salvation in Christ