The Paris Review's Blog, page 849

February 7, 2013

Letter from Jaipur

Last year’s Jaipur Literature Festival was exciting and boring at the same time—a death threat is exciting, but thirty death threats are boring; as Dostoevsky wrote, “Man is a creature who can get used to anything.” Salman Rushdie was scheduled to attend: Islamic groups agitated to deny him a visa, which he does not need in order to enter India, but never mind. It was suggested that instead Rushdie might address the festival via video conference: the government itself advised against this. Hari Kunzru, Jeet Thayil, Amitava Kumar, and Ruchir Joshi read aloud in protest from The Satanic Verses, still banned in India, but, after the gravity of their collective transgression had been brought home to them, they left the festival.

We know what comedy is: life is increased. Think of Rodney Dangerfield addressing the crowd at the end of Caddyshack: “Hey, everybody, we’re all gonna get laid!” And we know what tragedy is: isolation increases. I used to think that life was about winning everything, Mike Tyson once said, but now I know that life is about losing everything.

But what is India, with its boundless affirmation of life in general that befouls so many lives in the particular, with its joyous proliferation unto overcrowding, need, and misery? I did my small part, during my brief month there, to maintain those inequalities: Give me your shoes, I know you have other pair, you not need these, give them me, said a man as he tried to pull my sneakers off while a second man tried to pin my arms; and what he said was true, somewhere on the other side of the world I did have another pair of shoes, four shoes and only two feet; all the same, unhand me, my little friend, before I pick you up and throw you like a javelin.

I attended the 2013 JLF. It began in the same way. Read More »

The Best-Read City in America, and Other News

“The ordinary, mild-mannered bookstore had stripped off its everyday shirt to reveal its superpowers, moving with a slamming shift into warp-speed pleasure.” A paean to vanished bookstores.

How to (if you must) divest yourself of books.

Here is a trademark lawsuit involving both space marines and superheroes. Yes, I said space marines.

“The precision and spirit of Austen’s novels derive, in part, from the cherished objects with which she and her heroines were in daily contact—things that might well have been overlooked or spurned by everyone else.”

Washington, D. C. earns the title of Most Literate City. The Most Romantic crown, however, goes to Knoxville, Tennessee. (If you define romance as only shopping at Amazon.com, of course.)

February 6, 2013

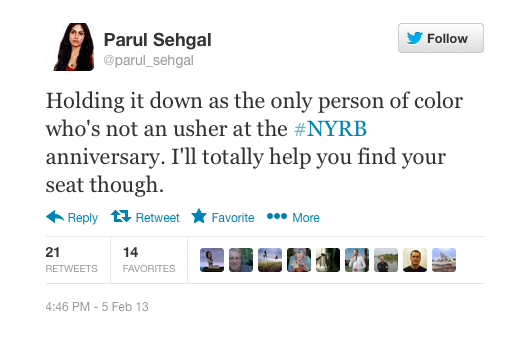

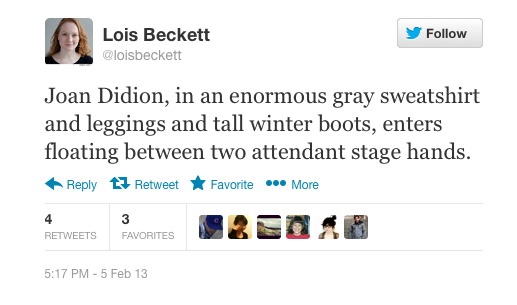

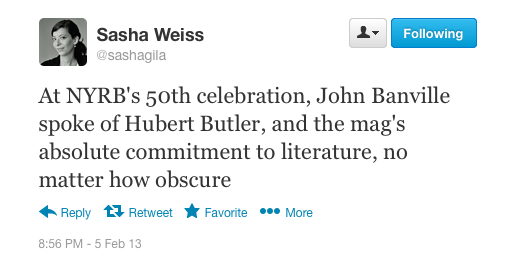

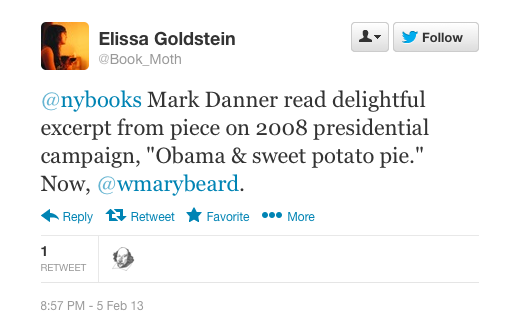

The NYRB Fiftieth Anniversary Kickoff, in Tweets

Crying While Reading

In second grade, I first read “The Little Match Girl.” To the uninitiated, this Hans Christian Andersen tale is about a beggar girl who, on Christmas Eve, warms herself by burning her matches one by one, imagining happier times with her dead grandmother by their light. In a final blaze, she imagines herself warm and happy, surrounded by love and the lights of a Christmas tree. Then we learn she’s actually frozen to death.

In second grade, I first read “The Little Match Girl.” To the uninitiated, this Hans Christian Andersen tale is about a beggar girl who, on Christmas Eve, warms herself by burning her matches one by one, imagining happier times with her dead grandmother by their light. In a final blaze, she imagines herself warm and happy, surrounded by love and the lights of a Christmas tree. Then we learn she’s actually frozen to death.

I was, to put it mildly, traumatized by the story. It haunted me. In the years since, I have learned that this is not an uncommon reaction; no fewer than two of my adult friends have revealed that, from time to time, “The Little Match Girl” intrudes on their thoughts and casts them into the doldrums. But as a seven-year-old, I was wholly unable to deal with my emotions. For days after hearing the story, I was quiet and withdrawn, my thoughts with the poor, cold match girl and her pathetic wares. My teacher, Mrs. Romer, noticed, and asked if everything was okay. I said yes, but one day, thinking of the tiny frozen body on the streets of wintry Copenhagen during a math lesson, I burst into uncontrollable sobs.

The fallout was humiliating. Mrs. Romer asked me to eat lunch with her privately so we could discuss what was bothering me; who knows what trauma she thought to uncover. I was too embarrassed to admit the actual source of my anguish—I knew it to be wildly babyish, as well as irrational—so I quickly concocted a lame story about my brother having the flu. I guess the implication was that I was afraid for his life; in any case, it was unconvincing enough that she called my parents.

Having learned early the dangers of giving into lit-related emotion, I was pleased to see a feature titled What to Do When Books Make You Cry on Public Transportation on BookRiot. Their advice is common sensical and wide-ranging, but does not address the concerns of younger readers. And, really, there is no time like childhood for emotionally wrenching books—if memory serves, in one school year we read Bridge to Terabithia, Number the Stars, Hatchet, and Where the Red Fern Grows. In one school year! Maybe our teachers were trying to toughen us up for public reading; personally, I think holding it together for Cormac McCarthy is a cakewalk after Sounder. “The Little Match Girl,” however, should be reserved for the truly stony hearted. Or at least the over-seven set.

Cruise Control

Shortly before Christmas, New York moviegoers could choose between seeing two Tom Cruise films that were screening simultaneously: Jerry Maguire at Lincoln Center (as part of a retrospective celebrating him), and Eyes Wide Shut at the Brooklyn Academy of Music (as part of a Christmas movie series). Sorry I could not watch both and be one viewer, I opted for Eyes Wide Shut. “You had me at hello” and “Show me the money!” would have to wait for another day. Surely I was taking the cultural high road, the Guermantes Way, if you will, one that would certainly never meet up with any quippy, Tom Petty–inflected sports romance.

Shortly before Christmas, New York moviegoers could choose between seeing two Tom Cruise films that were screening simultaneously: Jerry Maguire at Lincoln Center (as part of a retrospective celebrating him), and Eyes Wide Shut at the Brooklyn Academy of Music (as part of a Christmas movie series). Sorry I could not watch both and be one viewer, I opted for Eyes Wide Shut. “You had me at hello” and “Show me the money!” would have to wait for another day. Surely I was taking the cultural high road, the Guermantes Way, if you will, one that would certainly never meet up with any quippy, Tom Petty–inflected sports romance.

Since the bemused response to the release of Eyes Wide Shut in 1999, the film’s admirers have been increasingly winning out over its critics. But both camps agree that the film is a closed universe, meticulously arranged down to the smallest detail, the ne plus ultra of auteurist micromanagement. Kubrick was a famous hermit who refused to leave England to film Eyes Wide Shut, although it is set in New York. Instead he constructed an enormous studio replica of Greenwich Village, and everything was shot in this controlled environment. Tom Cruise, as though under Kubrick-ordered house arrest, didn’t make another movie for the entire duration of the project (from 1997 to 1999). If you didn’t like the movie, you saw the final product as hermetically sealed and emotionally sterile, a bad imitation of New York and the way that real people talk and feel. But if you liked the movie, it was because each of its frames could be subjected to exhaustive analysis in a thousand term papers, like a game of hidden pictures, mined for occult symbolism, motifs of consumerism, and every possible allegorical reading. Kubrick’s obsessively detailed vision seemed particularly to license a shot-by-shot deconstruction. (I invite you to google: “Eyes Wide Shut illuminati” for a good time.) Read More »

Brotherly Love

Yesterday, My Brother’s Book, Maurice Sendak’s tribute to his brother, Jack, was posthumously published. Says Tony Kushner, “I really feel that the book is a goodbye from him to everybody who loved him—which was a lot of people.”

Bookish Heroism, and Other News

Before they were stars: the wayward youth of Balzac, Flaubert, Baudelaire, and more. (And it was wayward!)

Bookish, a new website created by Penguin, Hachette, and Simon & Schuster, has launched. Check out Elizabeth Gilbert’s riposte to Philip Roth!

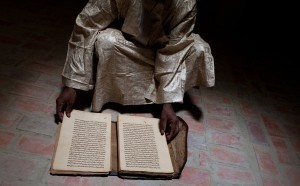

How one man saved eight thousand precious volumes amid the violence in Timbuktu.

We are psyched about the new Believer podcast, The Organist.

A. L. Kennedy: “From here I can see the spine of The Wind in the Willows —the same volume I read in bed when I was a child. It has been my friend for more than 40 years, there for me, a kind light. Here is the volume of Raymond Carver I threw across the room when I was a student because it was so amazing, so tender with broken people. Here is Alasdair Gray and his mind-blowing Lanark, which taught me the courage inherent in thinking and creating when I had no courage of my own. Here is my library.”

February 5, 2013

Early Failures

Toward the end of 1918, infantry from the U.S. Army’s 85th Division occupied Arkhangelsk, a city in North Russia on the shore of the White Sea. They had come with other Allied troops to rescue the stranded Czechoslovakian Legion, forty thousand soldiers abandoned after the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk. Although Josef Stalin—at that time the Commissar of Foreign Nationalities for the newly formed Soviet Russian Republic—had agreed to the evacuation, he also had demands about how it should be done, including the legionnaires’ unconditional disarmament.

Toward the end of 1918, infantry from the U.S. Army’s 85th Division occupied Arkhangelsk, a city in North Russia on the shore of the White Sea. They had come with other Allied troops to rescue the stranded Czechoslovakian Legion, forty thousand soldiers abandoned after the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk. Although Josef Stalin—at that time the Commissar of Foreign Nationalities for the newly formed Soviet Russian Republic—had agreed to the evacuation, he also had demands about how it should be done, including the legionnaires’ unconditional disarmament.

Instead, the Czechs decided to stockpile weapons as they withdrew. Before long, for a variety of reasons, the ceasefire collapsed, and the Czech legionnaires began a violent, almost hallucinogenic campaign to smash through Soviet defenses on their way to the Pacific Ocean. They demolished trainyards and captured cities. They destroyed bridges, commandeered armored locomotives, and inflicted devastating losses on the Red Guard.

Every military action carried them farther from Arkhangelsk. When the Americans—nicknamed the Polar Bears—finally arrived, they discovered no one to rescue and no real mission beyond skirmishing with Bolshevik sympathizers. In Europe, the Great War was ending; in North Russia, though, a strange, confused campaign had just begun. Read More »

The Daughter of Time

“It’s an odd thing but when you tell someone the true facts of a mythical tale they are indignant not with the teller but with you. They don’t want to have their ideas upset. It rouses some vague uneasiness in them, I think, and they resent it. So they reject it and refuse to think about it. If they were merely indifferent it would be natural and understandable. But it is much stronger than that, much more positive. They are annoyed. Very odd, isn’t it.”

With the discovery of Richard III’s bones—and what some are calling the monarch’s redemption—we imagine that somewhere, Josephine Tey is smiling.

A Week in Culture: Carlene Bauer, Writer

Tonight I went to my first Spanish class at Idlewild on Nineteenth Street. 7:30 to 9 P.M.. When I signed up for this class in November, shortly after I came back from spending a few weeks in Barcelona, I was flush with the joy of recent travel, and intent on injecting some novelty, intellectual and otherwise, into my life. I had an idea that I might try to make it back to Spain at the end of this year, and if that happened, I'd like to be able to do more than buy a few peaches without tripping over my tongue, or wanting to revert to French, the only other foreign language I know. And if that never happened, I would at least be doing something to forestall dementia. But as the intervening weeks, growing colder and darker, put more and more distance between me and that trip—I dreamed that, didn’t I?—I started to wonder why I’d done such a thing. It seemed as unnecessary and out of character as signing up for ten colonics through Groupon. But when, after the fifteen of us had gathered in a circle in the back of the store, and the teacher welcomed us in Spanish, something in me quickened in response to hearing the language. Maybe it was just sound as souvenir, but some sleeping dog in me perked up. Something similar had happened back in Barcelona, while standing in the La Central bookstore, looking at all the books I wanted to read but could not, feeling a strange urgency to get the key that would unlock what lay between those covers, a strange feeling that this was a language I needed to know deeper. Read More »

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers