The Paris Review's Blog, page 842

March 5, 2013

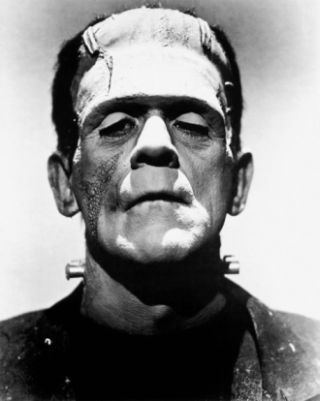

The Indescribable Frankenstein: A Short History of the Spectacular Failure of Words

Mrs. Chesser taught me that there is never any reason to use the word indescribable. Invoking the indescribability of something does no work except to tell everyone, quite explicitly, that you are incapable of describing. Indescribable is not a quality something can possess, only a failure that can overwhelm a writer. Even now, years later, I can practically hear Mrs. Chesser, her voice languid with existential weariness, pleading with all of us in third-period English: “For the love of God, ask ourselves why a thing is indescribable and then write that down. Never be so lazy as to just dash off, ‘It was indescribable.’ It’s a waste of everyone’s time.” I remember her making profound eye contact with me just as the words “waste of everyone’s time” escaped her lips. Chastened, and most likely the prime offender, I made a note to myself, much of it capitalized, and have since made all-out war on the indescribable in my life.

Mrs. Chesser taught me that there is never any reason to use the word indescribable. Invoking the indescribability of something does no work except to tell everyone, quite explicitly, that you are incapable of describing. Indescribable is not a quality something can possess, only a failure that can overwhelm a writer. Even now, years later, I can practically hear Mrs. Chesser, her voice languid with existential weariness, pleading with all of us in third-period English: “For the love of God, ask ourselves why a thing is indescribable and then write that down. Never be so lazy as to just dash off, ‘It was indescribable.’ It’s a waste of everyone’s time.” I remember her making profound eye contact with me just as the words “waste of everyone’s time” escaped her lips. Chastened, and most likely the prime offender, I made a note to myself, much of it capitalized, and have since made all-out war on the indescribable in my life.

But the indescribable has a history, and a distinguished one at that. In her novel Frankenstein, Mary Shelley uses the word “describe,” or some version of it, twenty-one times. Of those twenty-one, fourteen are coupled with a negation. Which means that approximately 66 percent of the time Mary Shelley uses the word “describe,” it is to describe how she, in fact, cannot describe something. “I cannot describe to you my sensations,” or, “How can I describe my emotions at this catastrophe,” or, “I cannot pretend to describe what I then felt,” or, “a hell of intense tortures such as no language can describe.” But these romantic, brain-feverish testimonies to descriptive incompetence are often immediately paired with very precise descriptions, as in, “Over him hung a form which I cannot find words to describe—gigantic stature, yet uncouth and distorted in its proportions,” or when the explorer Robert Walton writes his sister, “I cannot describe to you my sensations on the near prospect of my undertaking. It is impossible to communicate to you a conception of the trembling sensation, half pleasurable and half fearful, with which I am preparing to depart.” What is that indescribable sensation? Well, trembling, half-pleasurable, half-fearful, which is actually quite descriptive. Read More »

All A-Twitter

One-hundred-forty-character poets, channel you inner Bashō, O’Hara, and Williams and listen up! Immortality can be yours: the New York Public Library is sponsoring a Twitter poetry contest for National Poetry Month!

One-hundred-forty-character poets, channel you inner Bashō, O’Hara, and Williams and listen up! Immortality can be yours: the New York Public Library is sponsoring a Twitter poetry contest for National Poetry Month!

Here’s the (slightly Byzantine) deal:

Be American and over thirteen.

Register.

Follow @NYPL.

“Submit three poetic tweets in English as public posts on your Twitter stream between March 1 and 10, 2013. Three poetic tweets constitute one entry and each poem must contain the @NYPL Twitter handle.”

“Two of the poems can cover any topic you choose, but at least one of the three poems needs to be about libraries, books, reading, or New York City.”

The panel of distinguished judges will be looking for “originality, creativity, and artistic quality.” Winners will be highlighted on all the NYPL social networks and stand to claim a passel of truly excellent poetry books. (Plus the aforementioned glory.)

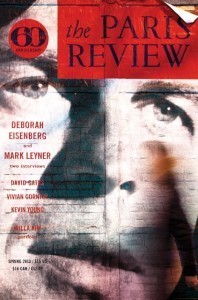

Cover Art

What follows is the Editor’s Note from issue 204.

What follows is the Editor’s Note from issue 204.

For the cover of our sixtieth-anniversary issue, we asked the French artist JR to make a giant poster of George Plimpton’s face and paste it up on a wall in Paris, as a symbolic homecoming and a tribute to the patrie. Posters are what JR does. In Vevey, Switzerland, he covered one entire side of a clock tower with Man Ray’s Femme aux cheveux longs. In Havana, Los Angeles, Shanghai, and Cartagena, Spain, he plastered headshots of elderly residents—headshots many stories tall—across the facades of old buildings. He called the project “The Wrinkles of the City.” We love these pictures. We love the way they honor the desire behind any portrait—to eternalize a particular face—and at the same time welcome the wear and tear of weather, smog, graffiti: of life as it passes by.

It’s been ten years since George died in his sleep, after half a century at the helm of the Review. “George,” we say, even those members of the staff who never met him. He looms large in our imaginations—as large as that image gazing across the rue Alexandre Dumas—because he invented the form of the Review and gave it his spirit. “What we are doing that’s new,” he explained in a letter to his parents, “is presenting a literary quarterly in which the emphasis is more on fiction than on criticism, the bane of present quarterlies. Also we are brightening up the issue with artwork.” This from a man who was about to publish Samuel Beckett! George’s magazine was blithely serious and seriously blithe. Read More »

The Fortress of Solitude: The Musical, and Other News

“If authors are hesitant to work with artists, artists have no reservations about working with authors’ words.” A tribute to some glorious, recent illustrations.

Speaking of lovely books: nominate a cover for the 50 Books, 50 Covers book design awards.

Great, bite-size cell phone reads.

Speaking of short fiction, a tribute to a master of the form, Joaquim Maria Machado de Assis.

The Fortress of Solitude: the musical.

March 4, 2013

Barnaby Conrad: Author, Matador, Bon Vivant, and Thorn in Hemingway’s Side

My brief acquaintance with Barnaby Conrad, one of the bon vivant-iest of all modern bon vivant writers, happened because a stranger decided to wear a certain necklace one evening last fall. I’d been invited to a Fashion Week trunk show in one of New York City’s trendier hotels. I almost didn’t go. I hate trunk shows. But I did go, and the designer greeted me at the door. There was a lovely starkness about her: those gaunt cheekbones and long hands and limbs; Modigliani likely would have loved her. Dangling from a chain around her neck: a charming little brass charm in the shape of a bull.

My brief acquaintance with Barnaby Conrad, one of the bon vivant-iest of all modern bon vivant writers, happened because a stranger decided to wear a certain necklace one evening last fall. I’d been invited to a Fashion Week trunk show in one of New York City’s trendier hotels. I almost didn’t go. I hate trunk shows. But I did go, and the designer greeted me at the door. There was a lovely starkness about her: those gaunt cheekbones and long hands and limbs; Modigliani likely would have loved her. Dangling from a chain around her neck: a charming little brass charm in the shape of a bull.

“My father was a bullfighter,” explained the designer, who’d created the charm herself. “American. You’re an author, right? Then you probably know him: Barnaby Conrad, the writer.”

I did not, as a matter of fact, know Barnaby Conrad. Shame on me: as it turned out, Truman Capote had known Barnaby Conrad. So, for that matter, had Noel Coward and Eva Gabor and William F. Buckley. Sinclair Lewis, John Steinbeck, Alex Haley, and James Michener: they all knew him well. And Hemingway too—although, at one point, he apparently wished that he’d never even heard of Barnaby Conrad.

The first thing that you learned about Mr. Conrad, even when you met him in abstentia: he was charming and very appetite-driven. Two weeks ago, he died at the venerable age of ninety, having authored more than thirty-five books detailing, among other topics, his descent into alcoholism, the secrets of Hemingway’s Spain, and the hijinks of the international bon ton in midcentury San Francisco. He was a Renaissance man with a talent for dwelling at epicenters of rarified, exclusive realms: as one of history’s few high-visibility American bullfighters (while in Spain, he went by the name “El Niño de California,” i.e., the California Kid), the proprietor of a who’s-who nightclub, and also as an accomplished artist (several portraits of his famous friends hang in DC’s National Portrait Gallery). Read More »

March Madness

“It was one of those March days when the sun shines hot and the wind blows cold: when it is summer in the light, and winter in the shade.” —Charles Dickens

In the Buff: Literary Readings, Pasties, and Jiggling Genitalia

The beautiful is always bizarre. —Charles Baudelaire

My first time with the postfeminist, burlesque lit girl culture—pasties, G-strings, audience clapping to jiggling booties—I was in a fun little Brooklyn bar called the Way Station. I had, minutes before, read from my own work, what I thought was a wryly humorous and oh-so-literary postfeminist exploration of time, culture, and relationships. I knew the term “burlesque” had been thrown around on the billing, but to my Midwestern sensibilities, burlesque meant feathers and brief flashes of almost breast, the inner curves of almost vagina, with the full monty saved for fictional accounts. This, on the other hand, was a literary reading. So you can imagine my reaction to the dancer’s G-stringed ass shaking so close to my face I felt an instinct to throw up my hands in self-defense. I don’t think she meant to shake her booty in my face. Not mine particularly. It was coincidental. But it felt so personal at the time, in the moment so intentional, that I was certain something must be happening creatively. There were the dancer’s pastied breasts on my author page, alongside my book, compliments of my publisher’s well-intentioned marketing attempts. Cosmic. There was a message in this. I wasn’t quite sure what the message was except that it involved pasties and butt jiggling. All I knew for sure was that it was disconcerting to an oh-so-serious, postfeminist, gender explorer. Read More »

Bookish Cakes, and Other News

Happy Monday. Here are some cakes inspired by books!

Nineteen Charles Bukowski drawings have come to light; most of them illustrated his column for the Los Angeles Free Press.

A poem written by a thirteen-year-old Charlotte Brontë is expected to fetch at least £40,000 at auction.

“If there has ever been a golden age for the unconventionally named author, it is now.”.

The 2013 Tournament of Books is on.

March 1, 2013

G. Mend-Ooyo, Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia

A series on what writers from around the world see from their windows.

When I was young, every morning I would take our hobbled horse and walk it in the dawn light. My father would say, “Sleep late like a horse. Rise early like a bird.” As I walked with the horse, I was very happy to have the little birds fly just above the light of dawn as they sang.

The rhythm of each morning of my life still moves to the beat of my lovely childhood. From the window of my home in the center of Ulaanbaatar, I grasp the pale light in the east. Just as I used to bring in the horses pastured on the wild steppe, I spend time recollecting in my mind many thoughts that have taken flight. The images of life, transected by the window, are a chiaroscuro.

I can clearly see the great seat of learning that is the National University of Mongolia. Sometimes it seems to be an image hanging on walls. A few steps from the window is my writing desk, made from Mongolian pine wood. When I sit at the desk, the world shifts into a different space. The history books grow thicker. There is no time to watch what goes on beyond my window. —G. Mend-Ooyo

Story Time!

We are delighted to report that our contributors are racking up all kinds of well-deserved honors!

We are delighted to report that our contributors are racking up all kinds of well-deserved honors!

First, David Means's story “The Chair”(Issue 200) has been chosen for this year’s Best American Short Stories anthology.

We also have seven nominees for this year’s Pushcart Prize:

Sarah Frisch, “Housebreaking,” Issue 203

David Gordon, “Man-Boob Summer,” Issue 202

Lorrie Moore, “Wings,” Issue 200

Davy Rothbart, “Human Snowball,” Issue 201

Sam Savage, “The Meininger Nude,” Issue 202

David Searcy, “El Camino Doloroso,” Issue 200

John Jeremiah Sullivan, “The Princes: A Reconstruction,” Issue 200

Congratulations, everyone!

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers