The Paris Review's Blog, page 798

July 26, 2013

What We’re Loving: Oology, Impostors, Sweden

Lord Walter Rothschild, founder of England’s Natural History Museum at Tring, home of the world’s largest bird-egg collection.

Julian Rubinstein’s “Operation Easter,” in last week’s New Yorker, has been my breakfast reading and dinner conversation most of this week. Concerned with the obsession for collecting birds’ eggs—a mania that dates back almost to the mid-nineteenth century—the article relates lurid tales of collectors falling off cliffs in pursuit of nests, hiding amassed collections in secret compartments in their beds, and donning guises to steal eggs from a museum (the party in question pinched ten thousand eggs in some three years). When investigators from the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds apprehend a suspect in his apartment, the man tells them, “Thank God you’ve come … I can’t stop.” With investigators jumping into cars, busting down doors, and engaging in two-day island-wide manhunts, this article reads more than a little like a thriller. I’d love to see Gary Oldman in a starring role when it hits the big screen. —Nicole Rudick

I can’t help seconding Sadie’s recommendation of In Love, a novella by Alfred Hayes that has just been reissued by New York Review Classics. The story of a casual love affair that becomes serious as soon it starts to fall apart, In Love harks back to a classic French tradition—what you might call the Novel of Disillusionment—perfected over a century by Constant, Flaubert, Turgenev, and Proust, among others. At the same time, in its use of one-sided dialogue, its film noir sensibility, and its evocation of New York life, this 1953 masterpiece also seems utterly modern—a culmination and a book utterly at home in its moment. —Lorin Stein

This month I had a particularly blue moment. I returned to an old favorite, Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye , and then immediately afterward read Maggie Nelson’s Bluets, a book that had been recommended to me several times by fellow students and professors alike. It would be difficult for me to state, with confidence, what exactly Bluets is about. The book-length essay is written in vignettes, each numbered and varying in length. Nelson begins with a captivating proposition: “Suppose I were to begin by saying that I had fallen in love with a color.” Something that began as “[a]n appreciation, an affinity” became something “more serious” and then “it became somehow personal.” I drifted easily into Nelson’s world of blue, in which she seamlessly strings together personal narratives, quotes, and facts, each poignant sketch its own bluish jewel. —Jo Stewart

Austen Ousts Darwin, and Other News

Jane Austen is indeed replacing Darwin on the £10 note.

Margaret Atwood has written an opera, fifteen years in development, about the poet Pauline Johnson.

The letters of Roald Dahl, spanning most of his life, will be published in 2016.

This map, a “chapter-by-chapter breakdown of the comings and goings of characters in the The Great Gatsby,” is lovely.

July 25, 2013

Beer Paradise

My life might well be divided into two categories: Before Beer and After Beer.

Life AB started in the middle of a trailing, boring Carolina winter. Previously, bourbon had been my drink, and I thought the horizon of beer extended only to bottles with “Light” surnames. If you had asked me to describe beer culture, I would have said, what culture? But then one evening, prior to the first round of trivia at a local bar, a friend bought a Rogue Dead Guy for me.

Prior to the first round of trivia at a local bar, a friend bought a Rogue Dead Guy for me. Rather than commit impoliteness, the nastiest of southern sins, I sipped the beer with a smile. And then everything changed. This rich, decadent bread was nothing like the stale, crumbling crackers that filled the malted liquid basket of my past. Now, when referring to places I’ve been before the coming of hops into my life that day, I say, “I’ve been there, but I wasn’t a beer person yet.”

At five o’clock on a mid-September Friday afternoon, the woman I am dating and I have to sneak out of our offices early for our first trip to Asheville together and my first visit to the city “as a beer person.” She comes from the eleventh floor, on loan to the bank from her consulting company. It’s her first job after graduating from Chapel Hill, and she took it while she figures out what she really wants to do. I descend from the thirty-ninth floor, permanently on loan to the partners at my law firm. It’s my first job after graduating from the law school down the road from her sorority house, and I took it, in part, so that someone might introduce me to a woman or to her sister or to her mother much in the same way that Alec describes Fitzgerald’s semi-autobiographical Amory in This Side of Paradise:

ALEC: Oh, he writes stuff.

CECELIA: Does he play the piano?

ALEC: Don't think so.

CECELIA: (Speculatively) Drink?

ALEC: Yes—nothing queer about him.

CECELIA: Money?

ALEC: Good Lord—ask him, he used to have a lot, and he’s got some income now.

(MRS. CONNAGE appears.) MRS. CONNAGE: Alec, of course we’re glad to have any friend of yours—

ALEC: You certainly ought to meet Amory.

I wish I could have met Fitzgerald. I think of him frequently, or rather, I think of his pseudo-autobiographical characters often enough. The draining struggle between writing and money, loves and incomes, and seeming “queer” and appearing “respectable” draws me to Fitzgerald’s characters—Amory in Paradise, Anthony Patch in The Beautiful and Damned. While it may seem strange, even perverse, given his own history with alcohol, Fitzgerald and his writing have always felt particularly tied up with my budding passion for beer. Maybe it’s merely a question of timing; maybe of geography—but for me the two are inexplicably and inextricably linked.

I open and close the car door for the woman, climb into my Tahoe, pull out of the dank subterranean parking garage, head west, and aim for the mountains.

****

Earlier in the week, I send the first of many emails to the woman about the pending trip, filled with itineraries and suggestions. The drive to Asheville isn’t much different. We fill every minute of the trip by planning our every minute in the mountain town. I think, later, of the “great wave of emotion” that washes over Amory and Rosalind, or even the real Francis Scott and Zelda:

They were together constantly, for lunch, for dinner, and nearly every evening—always in a sort of breathless hush, as if they feared that any minute the spell would break and drop them out of this paradise of rose and flame. But the spell became a trance, seemed to increase from day to day. All life was transmitted into terms of their love, all experience, all desires, all ambitions, were nullified.

But once the sixteen-story Buncombe County Courthouse rises from the rolling hills, my courtly concerns for the lady on my right desert me, and my passion for beer sets in. In this, I am alone: she’ll drink it, but she doesn’t see past the horizon. She merely tolerates my obsession. I don’t mind; I can’t be bothered by myopia.

****

In the three years since this initial After Beer Era trip to Asheville, the city’s craft beer community has grown and matured dramatically. One indication of this is Asheville Beer Week, whose second annual celebration occurred in May. Highland poured a 2008 vintage of its perennially popular Cold Mountain Ale and a keg of its Auld Asheville Ale, brewed in 2009 for the brewery’s fifteenth anniversary. The years put on these beers literally prove the community’s coming of age.

And perhaps it’s a paradoxically good sign that Asheville lost the title of Beer City USA in 2013 after four years of holding it. The designation is essentially an online popularity contest conducted each year by homebrewing pioneer and Brewers Association president Charlie Papazian. But the country’s established beer hubs—San Francisco, San Diego, Boston, Denver, Philadelphia, and Seattle—have never won, and Portland last claimed the title in a tie with Asheville in 2009. Maybe “Lil’ Ole Asheville,” as beer writer Anne Fitten Glenn once wrote, has finally grown up.

There’s scarcely a soul in the “Paris of the South” that keeps a finger on Asheville’s beer pulse as reliably as does Glenn. She’s covered the handful of new breweries that have opened this year, including King Henry VIII-influenced Wicked Weed and Thomas Wolfe-inspired Altamont. (The English monarch reportedly said, “Hops are a wicked and pernicious weed, destined to ruin beer,” and Wolfe used “Altamont” for his depiction of Asheville in the roman à clef Look Homeward, Angel.) Glenn was also an invited guest when two of the country’s largest craft beer makers, Sierra Nevada and New Belgium, made their announcements to build breweries in Buncombe County—if one can call restaurants, walking and cycling trails, outdoor music venues, and boat access a “brewery.” Another Colorado-based beer outfit, Oskar Blues, started its second canning line in December about thirty miles away from Asheville at the mouth of the Pisgah National Forest in Brevard. It was this brewery, the maker of Dale’s Pale Ale, that so valued Glenn’s community contacts and her ability to navigate the region’s deep-rooted and convoluted brewery political structure that it hired her to work in marketing—but not before she wrote the definitive “intoxicating history” of the local beer she holds dear.

When you look past the snob stereotypes, the gentrification of the common man’s drink, and really delve into the beer scene, you find a small, trusting, and passionate community of people. The beer is good, but the company is usually better. Just as people who write that send fan emails to each other, tweet praises, and recommend others’ works—all in hopes of receiving acceptance into an unspoken circle of “writers”—brewery owners, brewers, and beer lovers do the same. I credit Glenn with helping me penetrate this circle. It’s becoming evident, as the trip goes on, that my traveling companion knows nothing of this world, a divide that, from afar, is obviously problematic.

Since my first meeting with Glenn, shortly after my first After Beer Era trip to Asheville, she’s become my favorite drinking buddy when I’m in town. One of the first beers we shared together was a Wedge Iron Rail India Pale Ale at Clingman Café, a small sandwich shop across the street and around the corner from the brewery in the River Arts District. Glenn told me this is only place to find Wedge’s beers outside the brewery’s taproom—Wedge owner Tim Schaller is as regular a sight at the restaurant as the “Tim Special” is on the menu: egg, fresh mozzarella, tomato, and pesto on ciabatta.

Schaller bought our beers that day from a small table on the other side of the main seating area before Glenn and I rushed to speak on a panel about the local beer economy at the Southeast Land & Real Estate Conference. The crowd in the musty hotel event space was as electrifying as the conference’s name. I was glad I had that lunch beer in me.

Earlier this year, Glenn released her book chronicling “the region’s explosion into a beer mecca.” And F. Scott Fitzgerald figured in this history. Fitzgerald lived in rooms 441 and 443 at the Grove Park Inn in north Asheville during the summer of 1935 and for several months in 1936, when he brought his mentally unstable wife to Asheville and installed her in the nearby Highland Hospital, a well-regarded treatment facility in Montford.

And, in a completely different way, his Asheville experience, too, seems to have centered around beer. A local bookstore owner and friend, using the discarded bottles in Fitzgerald’s hotel room for reference, estimated that Fitzgerald consumed up to thirty beers per day based on the cache of empties scattered there. Fitzgerald’s secretary similarly took notice of his keenness for malt beverages during the summer of 1936. Glenn quotes her:

I haven’t ever, before or since, seen such quantities of beer displayed in such a place. Each trash basket was full of empties. So was the tub in one of the baths. Stacks of cases served as tables for manuscripts, books, supplies of paper.

Glenn notes a local’s memoir “paints a fairly sympathetic portrait of a tortured artist who produced more in the way of extramarital affairs and empty beer cans than short stories.” (He wrote “The Crack-Up” and started The Last Tycoon during his time at the Grove Park Inn.)

The beer geek in me yearns to know Fitzgerald’s beer of choice, hoping he preferred bottles of locally-made homebrew (his own homebrew recipe resides in Princeton University’s collection of his papers) to Pabst Red, White and Blue, one of the few beers available in Asheville after Prohibition. But given the bounty of bottles and cans allegedly in his possession, Glenn’s assumption is probably correct: “it likely was most any kind he could get his hands on.”

In the mid-1930s, Fitzgerald could have legally bought beer containing only six percent alcohol-by-volume (ABV) or less in North Carolina, and most of the widely available beer was a good bit less. It’s anyone’s guess if he would have enjoyed a small-batch collaboration in 2010 between the Grove Park Inn Resort & Spa and Highland called The Great Gatsby Abbey Ale. At seven percent ABV, he wouldn’t have had a problem partaking in his usual quantities. “[M]erely a vapid form of kidding,” Fitzgerald might say, as he wrote in Paradise.

But in truth, I know of course that his famously destructive habits wouldn’t make him a good drinking buddy. Certainly not one who would take pleasure in the finer points of craft brewing. Yes, the beer community, including those in the industry and those who simply love its fruits, has perhaps a higher rate of alcoholism than most similar-sized groups of people, if only for the fact that its members are around alcohol more than they are away from it. After the senses become numb, the appreciation and enjoyment of a meticulously crafted product also wanes.

****

I sometimes long for the Before Beer Era days, a time when I didn’t plan weekend trips around brewery visits, beer dinners, and tap takeovers. The beer festivals and tastings occasionally become overwhelming—too little time to enjoy too many different things. I can only remember the excitement of that first, obsession-focused vacation. And the tangible costs of such an all-consuming fixation.

On the Saturday afternoon before we plan to drive back to Charlotte, the woman and I sit outside at a wooden picnic table, its legs settled into the gravel that fills the parking lot next to the river at Wedge. A crude metal bucket of spent peanut shells sits between us and our pint glasses sit on the table, and the faint tings as the husks land in the pail break the silence, our trusty companion for most of the weekend. It’s no surprise, to either of us, that the end is near.

I’ll always remember the bitterness of the hops in that Iron Rail IPA, caught in the fall rays of a Carolina sun.

There were days when Amory resented that life had changed from an even progress along a road stretching ever in sight, into a succession of quick, unrelated scenes. It was all like a banquet where he sat for this half-hour of his youth and tried to enjoy brilliant epicurean courses.

Win Bassett is writer, lawyer, and Yale Divinity student. His work has most recently appeared in The Atlantic, Los Angeles Review of Books, Books & Culture, Religion & Politics, Publishers Weekly, and INDY Week. Follow him on twitter at @winbassett.

Hypothetical Tom Robbins–Inspired Ben & Jerry’s Flavors

While we enjoyed the book-inspired ice cream flavors the good people at HuffPo Books put together for National Ice Cream Month, it got us pondering a very real question: How is it that, given their sensibilities and aesthetic, Ben & Jerry’s has never produced an ice cream inspired by the work of Tom Robbins? While one friend pointed out that perhaps Baskin-Robbins gets dibs, the following immediately suggested themselves:

Even Cowgirls Get the Blueberries

Another Rocky Roadside Attraction

Vanilla Incognito

Skinny Legs and Almond (obviously a fat-free yogurt)

Many thanks to all who helped contribute ideas, although it should be said that no one could come up with a delicious flavor based on Still Life with Woodpecker.

On the Map: Sherwood Anderson; Clyde, Ohio; and the Mythologies of Small Towns

Wikipedia will tell you that the National Arbor Day Foundation has bestowed upon Clyde, Ohio, the illustrious title of Tree City USA, and also that the Whirlpool Corporation calls the town home. You might learn, too, from the “Notable Residents” section of Clyde’s Wikipedia page, that former NFL tackle Tim Anderson has lived there, and that he was preceded in this by George W. Norris, a progressive senator from Nebraska during the early part of the twentieth century. Should you meet a Clyde native of a particular sort, though—in San Francisco, say, or New York—she might skip these details to tell you about a more hallowed pedigree. She might say, if she judges you a literary type, that she hails from the small town where Sherwood Anderson’s Winesburg, Ohio is set. (Winesburg’s Wikipedia page will explain, if you happen to visit it, that it is not the setting for Winesburg, Ohio.)

It turns out, though—somewhat perplexingly—that Clyde natives eager to claim ties with Anderson are scarce. Since Winesburg’s publication, in 1919, residents have for the most part regarded Anderson as a prodigal child—a troublemaker and bawdy apostate from whom to keep a wary distance. A 2001 article in Cleveland Scene magazine titled “Unfavorite Son” noted that although the Clyde Public Library boasted a Whirlpool Room, “nary an alcove” had been dedicated to Anderson. For years, the library’s only copy of Winesburg “was kept in a locked closet with other ‘bad books.’” If you wanted a peek, “you had to ask the librarian, and she looked down at you with a scowl.” In the 1980s, an annual Sherwood Anderson Festival was inaugurated but lack of interest saw it swiftly snuffed. Local high school teachers exclude Winesburg from reading lists, and an Anderson scholar from a nearby college told Scene that at the time of the book’s release, townspeople regarded it as gossip: “They didn’t understand what fiction was,” he said. “They thought he was a liar.” It did not help, perhaps, that Winesburg contains much indelicate innuendo regarding married women, teenage girls, and the local religious establishment.

Still, nearly a century has passed since Winesburg’s publication. Anyone who might have detected in the novel traces of her own biography has surely passed on. Modern-day Clyde has little to recommend it, and it strikes one odd, at first, that natives would fail to claim Anderson with pride. A town of some 6,000 citizens fifty miles from Toledo, Clyde is a place of vacant storefronts and empty streets. Stoplights hang heavy between buildings of faded red brick, and plywood boards panel downtown windows. It is the sort of town from which escape can prove difficult and not the kind to which people readily relocate. People in Clyde are quick to discern condescension, and though Winesburg, Ohio owes its endurance to universality—to artful, empathetic investigations of human weakness and desire—they cannot shake the notion that it levels at their town a targeted indictment. They do not see in it a feat of artistic alchemy but a slim volume of petty judgment, a document of isolation rather than transcendence. Read More »

A Table of Remarkable Æras and Events

From the terrific Britannica Blog, a noteworthy page from the first edition of the Encyclopædia Britannica, 1768.

Wearable Books, and Other News

Meet The Wizard of Jeanz. It consists of twenty-one volumes, each a chapter of The Wizard of Oz that, when unfolded, turns into an article of clothing. Designer Hiroaki Ohya says he was “disillusioned with the transitory nature of fashion … [and] struck with the permanency of books as objects that can transport ideas.”

Yesterday it was book-inspired ice cream; now we have Harry Potter beer. Pilsner of Azkaban, anyone?

Speaking of (well, sort of), J. K. Rowling explains how she lit on the pseudonym Robert Galbraith: a combination of Robert F. Kennedy and Ella Galbraith, her childhood alias.

On spirants, those consonants which involve a continuous expulsion of breath.

The bad house guests in literature.

July 24, 2013

Small Island: An Interview with Nathaniel Philbrick

Nathaniel Philbrick has written six books on United States history, most of which take place on or by the sea. In 2000, his In the Heart of the Sea: The Tragedy of the Whaleship Essex—about the sunken whaleship that inspired a young Herman Melville—won the National Book Award for Nonfiction. He then wrote Sea of Glory: America’s Voyage of Discovery, The U.S. Exploring Expedition, 1838–1842, followed by Mayflower: A Story of Community, Courage, and War, which was a finalist for the 2007 Pulitzer Prize in History. Because of In the Heart of the Sea and his articles on the whaling industry, Philbrick and Melville have become something of a pair. Philbrick recently wrote the thin and ruminative Why Read Moby-Dick? and the introduction to the last Penguin Edition of Moby-Dick.

I had read In the Heart of the Sea and Mayflower years ago, but it wasn’t until this past spring when a local bookseller handed me Philbrick’s first book, Away Off Shore: Nantucket Island and Its People, that I decided to write him a letter. There’s a thrifty, poetic quality to the makeup of that book, a clear joy in the research alone. It’s rawer, not so carved by what reviewers have noted as Philbrick’s masterful use of narrative and perspective in his other books, and so shows his research instincts clearer. He includes a description of the spring day when early Nantucketers set a pit of snakes on fire, and the time in 1795 when robbers bent pewter spoons into keys to steal $20,000 in gold coins from Nantucket Bank. Farmers on the island used to fertilize fields by scaring sheep at night with burning coals, and whalers traded their pant cuffs for sex in the South Pacific Islands. I put my e-mail on the bottom of the letter and dropped it in the mail. He wrote back in June, offering lunch and a “ramble” around the island.

We met for chowder and beer down at Nantucket’s South Wharf, near the old ships chandlery. Centuries ago, scallop shanties were on the South Wharf, where “openers” shucked for hours under lantern light and pipe smoke. Philbrick had arrived on his bike and exactly on time, wearing wayfarer sunglasses. It was a sunny day; while transcribing the interview, I listened to wind and gulls behind his voice. He speaks energetically, smiles constantly and in a way that evokes Steve Carell, and, mostly, is humble. Later that evening, walking through his house with him and his beloved golden retriever Stella, I saw just one sign of his success: a tiny framed clipping of the July 9, 2000, New York Times best-seller list, in which Harry Potter is on the fiction side, and In the Heart of the Sea is on the other, at number two. He’s proud of his family and talks about them often. He showed me the marks on the wooden floor where his son had practiced cello, and the room full of his grandmother’s paintings, one of which might be of her good friend, Claude Monet’s daughter.

After lunch, we walked through downtown to visit the Nantucket Historical Association’s Research Library. On the way, he pointed in the direction of where Herman Melville visited and dined with Nathaniel Hawthorne the summer after the disastrous publication of Moby-Dick. As in his books, Philbrick resurrects the past with unexpected precision: “Hawthorne,” he said, “was handsome and shy.” When we arrived at the Research Library, an archivist greeted him by holding up a review of his newest book, Bunker Hill. “Did you see this?” she asked, pointing to a caricature of Philbrick dressed like a colonial. “Oh, jeez,” he said, and turned away bashfully.

Weeks later, sitting in his patio, Stella panting behind us, I asked him why he keeps retelling stories that people already know. The Mayflower story. Bunker Hill. Custer’s Last Stand. “Yeah, sure,” he said, smiling. “Everybody knows about the Little Bighorn. But what do they really know about the Little Bighorn? I knew nothing. What I knew was three sentences that had nothing to do with what happened.” He continued, “In each book, I don’t know what I’m getting into. And if I did know what I was getting into, the book would be stale. There would be no crackle. For me, it’s the act of discovery gives the prose life. Otherwise, it would be dead.”

Why did you move to Nantucket?

We came to Nantucket in 1986. It was my wife’s job that brought us here. She’s an attorney. She grew up on Cape Cod. I’m from Pittsburgh. I love to sail, but I’m not from a maritime area. I had grandparents in West Falmouth—that’s how Melissa and I ended up meeting. We were living in a suburb of Boston before we moved out. She was the breadwinner. I was at home, writing, taking care of the kids. We had kids, one and four.

You were a young dad.

We had Jenny when we were twenty-five. We had made sort of a pact. I said, You’re going to make a lot more money than I will—I was a journalist for what’s now Sailing World, out of Newport.

Neither one of us had spent any time here. It sounded like a good concept—no commuting, everyone would be close. We arrived in September—probably the first people to move to Nantucket without ever having spent a summer here. It took me a while to connect with the community, because I was at home with the kids. But then I got interested in the history of the island, and began to hang out at the archives. Away Off Shore is a product of learning history on my own, of going alone to look around the archives. Read More »

On the Occasion of Zelda Fitzgerald’s Birthday

F. Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald on the Riviera in 1926. In a letter from that year, Fitzgerald wrote,

There was no one at Antibes this summer, except me, Zelda, the Valentinos, the Murphys, Mistinguet, Rex Ingram, Dos Passos, Alice Terry, the MacLeishes, Charlie Brackett, Mause Kahn, Lester Murphy, Marguerite Namara, E. Oppenheimer, Mannes the violinist, Floyd Dell, Max and Crystal Eastman … Just the right place to rough it, an escape from the world.

This image appeared in “Zelda, a Worksheet,” in issue 89.

When Winning Is Everything

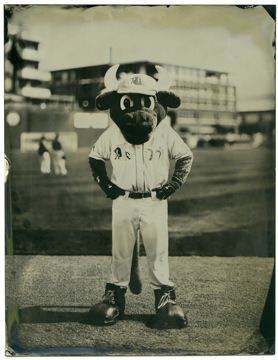

Durham Bulls mascot Wool E. Bull. Wet-plate tintype by Leah Sobsey/Tim Telkamp.

“Not really about baseball”: we’ve adhered pretty well so far to this watchword of our Bull City Summer documentary project, but cultivating indifference has been hard for me. I really care about baseball, and I watch the games closely. Still, I’ve made a season-long effort to notice the surroundings in a rather moony way—trying to soak up the ambient energy in the ballpark, its sheer quality and quantity.

That energy rises and falls throughout the game, but it does so unevenly and unpredictably, not always (in fact, usually not) in step with the action on the field. The video board command to MAKE SOME NOISE!, in huge, undulating letters, can whip the crowd into a lather, as can a Bulls home run, but these exclamatory moments have a short life span. As soon as the words leave the screen, as soon as the next pitch is thrown, the energy reverts, subject to its own mysterious forces.

There is plenty of early froth and surge: the singing of the National Anthem, the anticipatory buzz at first pitch, the grandstand up-and-down for hot dogs and beer and cotton candy, the breakthrough of early hits and runs, the sideshow pileup of mid-inning contests and mascot high jinks and blaring pop music. But then “the game turns inward in the middle innings,” as Don DeLillo puts it in his novella Pafko at the Wall (which is also the opening chapter of Underworld). At the deepest recess of this inward turn, there inevitably comes what I have dubbed “the nadir”: a quiet, satisfying, and almost narcotic moment when all of the energy, on the field and off, recedes, as if subdued by its own exuberance. The crowd noise falls to a low, warm murmur, like a dovecote. Read More »

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers