The Paris Review's Blog, page 613

February 25, 2015

You Talk Your Book

Looking rather Führer-ish, Anthony Burgess appeared on The Dick Cavett Show in 1971, where he was in rare form throughout—charming, funny, instructive, gently eccentric. The conversation ranges from England as a kind of bland utopia to Shakespeare’s “showbiz” skills and possible venereal disease, the perils of teaching writing (“The kids who want to write are usually very young, and their desire to write is usually a symptom of pubescence”), the insincerity of Milton’s Lycidas, and the distinction between pubs and bars:

A bar is not a pub. There are one or two pubs I think in New York … a real pub is a place where all the social barriers come down. You can drink with a member of the aristocracy or the local dustman. You play darts, you drink, you talk, and by this means you generate an atmosphere of genuine democratic society. You get ideas, you hear stories, you talk. And this is useful for a writer. The only pubs you must not, if you’re a writer, go to are the pubs in Dublin. Because in Dublin you talk your book. You say, I’m writing a darling book. Ah, tell us about it, they say. Then you tell them about it. And by the time you tell them about it, you’ve spent the desire to write it … The book is finished. You close it.

That Shakespeare book he mentions early on, by the way, received one of the most comically underdone blurbs I’ve ever seen, from Country Life, a magazine for which Burgess himself often contributed. “Of all the books about Shakespeare that 1964 will bring forth,” they wrote, “none is likely to make livelier reading than Anthony Burgess’s historical novel, Nothing Like the Sun.” There are small daggers in that “1964,” that “is likely to”: the most damning of faint praise.

Dan Piepenbring is the Web editor of The Paris Review.

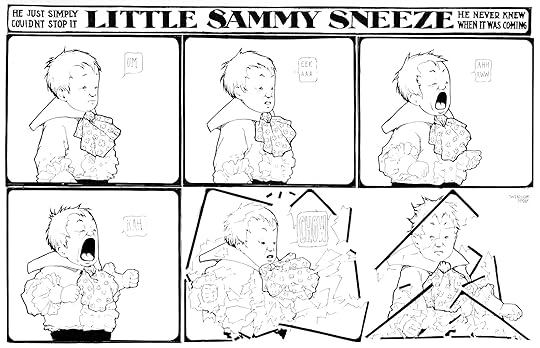

The Best Medicine

“He just simply couldn‘t stop it / He never knew when it was coming”: Winsor McCay‘s Little Sammy Sneeze, 1905.

If you’re not sick, you soon will be, and all the hand sanitizer in the world won’t save you. Everyone is a potential foe; no one wants to admit it. This morning on the subway, everyone was coughing and sneezing with varying degrees of discretion. The only people who seemed at all comfortable were two Japanese tourists wearing paper surgical masks. Well, maybe also the old man with a roll of toilet paper hanging around his neck on a loop of string. I envied all of them.

All you can do is read Mark Twain. He wrote “How to Cure a Cold” for the Golden Era shortly after arriving in San Francisco in September 1863. Twain may never have actually said the famous thing about a San Francisco summer being the coldest winter he’d ever known, but the Bay Area fog was presumably enough to aggravate a lingering head cold—well, that or a nineteenth-century cross-country train ride. According to a series of humorous letters to the editor Twain sent in to the Call and the Enterprise around this period, he’d had the cold—and an ensuing bout of bronchitis—for at least a month when he wrote this piece chronicling various home remedies.

The first time I began to sneeze, a friend told me to go and bathe my feet in hot water and go to bed.

I did so.

Shortly afterward, another friend advised me to get up and take a cold shower-bath.

I did that also.

Within the hour, another friend assured me that it was policy to “feed a cold and starve a fever.”

I had both.

I thought it best to fill myself up for the cold, and then keep dark and let the fever starve a while.

In a case of this kind, I seldom do things by halves; I ate pretty heartily; I conferred my custom upon a stranger who had just opened his restaurant that morning; he waited near me in respectful silence until I had finished feeding my cold, when he inquired if the people about Virginia were much afflicted with colds?

I told him I thought they were.

He then went out and took in his sign.

I started down toward the office, and on the way encountered another bosom friend, who told me that a quart of salt water, taken warm, would come as near curing a cold as anything in the world.

I hardly thought I had room for it, but I tried it anyhow.

The result was surprising; I must have vomited three-quarters of an hour; I believe I threw up my immortal soul.

Now, as I am giving my experience only for the benefit of those who are troubled with the distemper I am writing about, I feel that they will see the propriety of my cautioning them against following such portions of it as proved inefficient with me - and acting upon this conviction, I warn them against warm salt water.

It may be a good enough remedy, but I think it is too severe. If I had another cold in the head, and there was no course left me but to take either an earthquake or a quart of warm salt water, I would cheerfully take my chances on the earthquake.

The whole text is available here. And while the cures Twain details may sound highly dubious, take a look in your own medicine cabinet: at this time of year, most of us have enough tinctures, neti pots, supplements, and balms to furnish a small-time medicine show. (Since I just spent the better part of a month’s rent on some cold-pressed concoction containing echinacea, green tea, and an unpleasant note of oregano, I’ll withhold my own judgments.)

Sadie Stein is contributing editor of The Paris Review and the Daily’s correspondent.

The Suffering of Books

Alexis Arnold, San Francisco Phone Book, 2013.

For centuries, books have enjoyed the benefits conferred on inanimate objects, chief among which is their immunity to pain. So lucky they are, so smug, sitting painlessly on their shelves, passing the time. But it is winter, and it is cold, and now our books must freeze as their readers do.

To that end, Colossal has introduced me to the work of Alexis Arnold, who, in her Crystallized Book series, dips found books in a borax solution (is this proprietary? Can I buy some?) that freezes, crystallizes, destroys, or preserves them—whichever verb suits your fancy. Arnold aims to return books to a kind of prelapsarian state as aesthetic, functionless objects, unburdened by the complications of text. Her frozen books, she writes, are “artifacts or geologic specimens imbued with the history of time, use, and nostalgia. The series was prompted by repeatedly finding boxes of discarded books, by the onset of e-books, and by the shuttering of bookstores.”

See more below, and here.

Linux: The Complete Manual, 2013.

All’s Well That Ends Well, 2014.

Dan Piepenbring is the web editor of The Paris Review.

Peacock-eating for Poetical Public Relations, and Other News

A mural in Switzerland. Photo: Roland zh

In a 1914 publicity stunt—back when poets were free to partake of the great PR machine—Ezra Pound, W. B. Yeats, and four others gathered at a luncheon to eat a peacock. “The papers were alerted, and news of the meal spread far and wide, from the London Times to the Boston Evening Transcript.”

Karl Ove Knausgaard, your humble correspondent, is traveling across America for The New York Times Magazine: “The editor proposed that I travel to Newfoundland and visit the place where the Vikings had settled, then rent a car and drive south, into the U.S. and westward to Minnesota, where a large majority of Norwegian-American immigrants had settled, and then write about it. ‘A tongue-in-cheek Tocqueville,’ as he put it.”

Beethoven, Brahms, Mahler, Wagner: the Romantic legacy of these composers lives on … in first-person shooters. “The grandiloquent sounds of the nineteenth century are still alive in the new millennium … but only when someone is getting bludgeoned, bloodied, blown-up, or decimated with automatic weapons … Even heavy metal isn’t heavy enough for most composers seeking to juice up their combat scenes. We need something with a little more sturm und drang.

Starting to write a book is hard. Then there’s the whole middle part—also difficult. And finally there’s the end, which is no cakewalk, either. Can we learn anything from the last sentences in famous novels? “For writers, the last sentences aren’t about reader responsibility at all—it’s a once-in-a-lifetime chance to stop worrying about what comes next, because nothing does. No more keeping the reader interested, no more wariness over giving the game away. This is the game.”

On rereading Eileen Simpson’s Poets in Their Youth, a 1982 memoir of her turbulent marriage to John Berryman: “For a long time I could not shake the belief that these poets, all of them dead before their time from madness, self-neglect or suicide, paid a noble price for their pursuit of truth and beauty … I don’t think that anymore. Now, it’s Simpson herself who seems to be the hero … Simpson, who became a psychotherapist and went on to publish several books, writes with an almost uncanny clemency and a kind of cerulean objectivity. Where there might have been bitterness there is, instead, compassion.”

February 24, 2015

John Jeremiah Sullivan Wins Windham Campbell Prize

© Harry Taylor

Many congratulations to our Southern editor, John Jeremiah Sullivan, for winning one of this year’s Windham Campbell Prizes. The citation calls him “an essayist of astonishing range … empathetic and bracingly intelligent.” We heartily agree.

If you haven’t heard of the Windham Campbell Prizes, that’s because this is only the third year they’ve been awarded— Donald Windham and Sandy M. Campbell founded the prize in 2013 “to call attention to literary achievement and provide writers with the opportunity to focus on their work independent of financial concerns.” Awards are given for fiction, nonfiction, and drama, to those who write in English anywhere in the world.

“I couldn't overstate how encouraging this award is,” Sullivan wrote, “or how practically helpful. In this phase of my writing life I feel a desperate need to stay down over the research I'm doing, not look up, and the prize makes that possible.”

Also among this year’s nine winners is Geoff Dyer, whose work has previously appeared in The Paris Review. We applaud him, too, along with all of this year’s prizewinners. In September, they’ll gather at Yale for a festival celebrating their work.

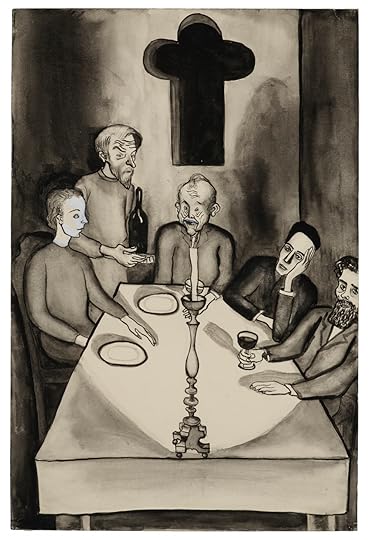

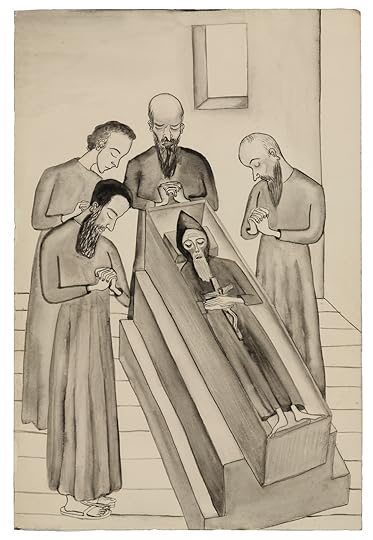

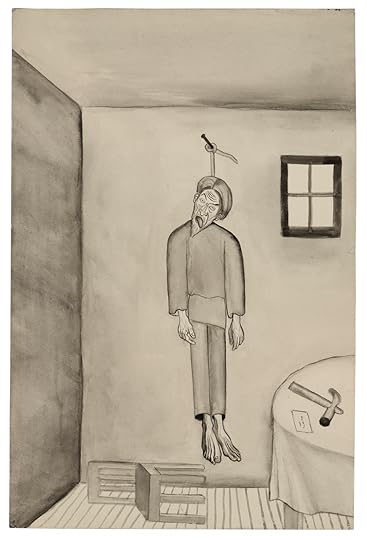

Alice Neel’s Brothers Karamazov

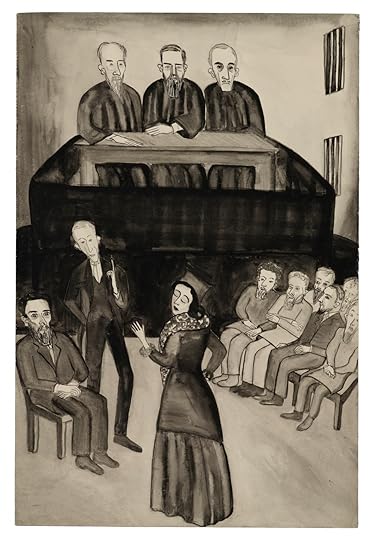

Alice Neel, Untitled (Karamazov, His Three Sons, and the Servant Gregory), ca. 1938, 14 ¼” x 10”. © The Estate of Alice Neel. Courtesy David Zwirner, New York/London.

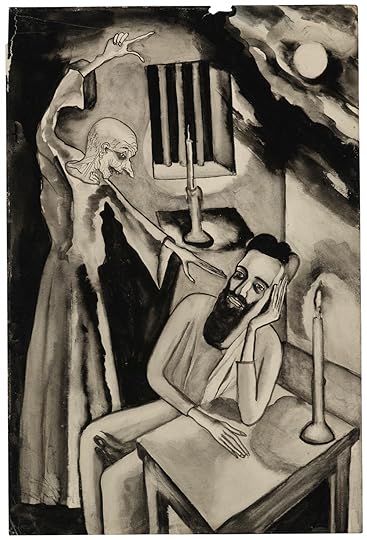

Alice Neel, who died in 1984, is remembered best as a portraitist—her paintings present friends, lovers, and other intimates with an astonishing, often forbidding guilelessness. Your average Neel portrait is penetrating, flip, scary, and more than a little funny, depending on how long you’re willing to hold its subject’s gaze. Neel’s people all look to be plodding through the Stations of the Cross with a kind of decadent resignation—this is the world we live in, and oh well. “Alice loved a wretch,” her daughter-in-law told the Guardian in 2004. “She loved the wretch in the hero and the hero in the wretch. She saw that in all of us, I think.”

When Neel wasn’t painting, she was sketching. Alice Neel: Drawings and Watercolors, a new book with a corresponding exhibition, collects this interstitial work, some of it polished and some hauntingly restive. “There is an essential melancholy to Neel’s work,” Jeremy Lewison writes in the book’s opening essay. “She presents a world of hardship, of tenement buildings and shared bathing facilities, of underprivileged and underclass immigrants, of humanity weighed down by the burdens of living in the harsh metropolitan environment, of human loss and tragedy.”

All of which makes her a natural candidate to reckon with the Russian classics, those icons of gloom.

Well, someone must’ve thought so, once, and that someone was right. In the thirties, Neel made a series of illustrations for an edition of The Brothers Karamazov that apparently never came to fruition. It’s not clear if the publishers rejected her work or if the whole project fell through, but in either case, damn. The eight illustrations demonstrate how attuned these two sensibilities are: it’s the marriage of one kind of darkness to another. Compare them to, say, William Sharp’s Brothers K illustrations and the difference, the change in register, is immediate—the black storm cloud of Neel’s pen is well suited to Dostoyevsky’s questions of God, reason, and doubt.

She brings out the madness and comedy, too. People forget how funny Dostoyevsky can be. Not Neel. She brings a manic bathos to these scenes that lends them both gravity and levity; in every wide, glassy pair of eyes, grave questions of moral certitude are undercut by the absurd. Some enterprising editorial assistant at Penguin Classics should see to it that a deluxe edition of Brothers K appears with these drawings posthaste.

Untitled (The Death of Father Zossima), ca. 1938, 14 ¼” x 10”. © The Estate of Alice Neel. Courtesy David Zwirner, New York/London.

Untitled (Grushenka and Mitya at the Drunken Party), ca. 1938, 14 ¼” x 10”. © The Estate of Alice Neel. Courtesy David Zwirner, New York/London.

Untitled (The Doctor’s Visit to Ilyusha), ca. 1938, 14 ¼” x 10”. © The Estate of Alice Neel. Courtesy David Zwirner, New York/London.

Untitled (The Suicide of Smerdyakov), ca. 1938, 14 ¼” x 10”. © The Estate of Alice Neel. Courtesy David Zwirner, New York/London.

Untitled (Katerina’s Testimony), ca. 1938, 14 ¼” x 10”. © The Estate of Alice Neel. Courtesy David Zwirner, New York/London.

Untitled (Ivan), ca. 1938, 14 ¼” x 10”. © The Estate of Alice Neel. Courtesy David Zwirner, New York/London.

Untitled (Ivan’s Dream), ca. 1938, 14 ¼” x 10”. © The Estate of Alice Neel. Courtesy David Zwirner, New York/London.

Dan Piepenbring is the web editor of The Paris Review.

And Frank O’Hara As Himself

Warning: going down the Frank O'Hara reading rabbit hole can swallow your day. It’s not that the poet’s reading of Lunch Poems is such a revelation, by which I mean different from what you might have imagined in your head. Rather, he reads them exactly the way you imagine them, or even read them aloud yourself: conversational, matter-of-fact, and incidentally just touched with Boston. He’s who you’d cast to play him.

It’s gratifying when things look or sound or act as we picture them; it’s nice not to have the limits of our imagination challenged. Or maybe that’s what imagination is. Anyway, it doesn’t happen often, and if we are surprised nowadays, there’s nothing to blame but laziness. The last time I remember being pleasantly surprised by the synergy of a voice and a face was when I first saw a picture of Brian Lehrer.

Of Pimps and Pyknics

Adventures in dictionaries.

An aurochs from The Wonderful Paleo Art of Heinrich Harder, 1920.

I.

In the novel by Patrick Modiano I’m translating, a bus stops at Cross Road in Bournemouth “devant un cottage pimpant,” and I had a feeling, somehow, that my first try, “in front of a pimpin’ little cottage,” was probably not right.

“Origin obscure,” says the Oxford English Dictionary about pimp. You can hear a titch more donnish vinegar in the etymology than the stolid lexicographers usually let show:

Generally thought to be in some way related to 16th century French pimper, vb., present participle pimpant alluring or seducing in outward appearance or dress…. French pimper is taken as ≈ Provençal pimpar, pipar, to render elegant. But these leave much to be explained in the history of the word before 1600.

Much to be explained indeed.

There is no history in English of the classier original meanings; right from the start, the English word meant “one who provides means and opportunities for unlawful sexual intercourse; a pander, a procurer” or “one who ministers to anything evil, esp. to base appetites or vices.” In French, pimper has disappeared and pimpant is just, per Harrap’s New Standard Dictionary, “smart, spruce, spick and span; femme pimpante, chic and attractive woman; une pimpante petite ville, a gay and spruce little town.” It all sounds so innocent, doesn’t it? Pimps—maquereaux—aren’t their fault. But the English, needing a new word for something unsavory, decided (as they so often do) to borrow one from the naughty French.

Weirdly, modern street usage gets back to the word’s more wholesome origins. After Pimp My Ride, the hit MTV show about “doing up your car like an African American Pimp: 20" gold rims, body kit, tinted windows, loads of ice in the trunk,” the verb pimping up or pimping out is now “more commonly used [to mean] making something cool or better: Yeah, I was totally pimping up my profile today!” or “to go all out on in a fashion manner: whoah that dude got himself all pimped out in the black and pink.” (All quotes in this paragraph from the always useful Urban Dictionary.) A “pimpin’ pink Mustang” isn’t likely to lead to unlawfully getting laid, or to base vices of any sort, but it does look chic and attractive, gay and spruce, spic and span. Pimpant.

II.

In one especially ridiculous Robert Walser story, the narrator meets two characters at the end: a certain “Wulff, 100% German, recalling Auerochsen, the primeval forests, the clang of swords, the pelt of bears. His full beard reached down to the tips of his toes. On his arm was a full-bosomed, voluptuous, firm, and juicy capitalist lady.” I had no idea what Auerochsen were, other than something toweringly Teutonic and paleo enough to be pimpin’ to the juiciest ladies.

My German-English dictionaries offered “Auerochse: aurochs,” which helped not at all. Maybe you know what an aurochs is; I didn’t. To American Heritage, third edition, where this is the whole definition of aurochs: “1. See urus. 2. See wisent.” Urus is: “An extinct wild ox, believed to be the ancestor of domestic cattle. Also called aurochs.” While wisent: “The European bison. Also called aurochs.” And not extinct. There are jokes about endless-loop dictionary entries like these—I had never come so close to finding one. In my translation, I made Wulff recall the aurochs, not the urus or the wisent. Why not? It sounded better.

I later found the creature marauding through the massively vocabularied Patrick Leigh Fermor, too: he describes Rumanian potentates with “phenomenal titles … Great Bans of Craiova, Domnitzas, Beyzadeas, Grand Logothetes, hospodars, swordbearers and cupbearers, all dressed in amazing robes … the only hint of feudal Europe, perhaps, being a crowned escutcheon in which the black raven of Wallachia impales the Moldavian auroch.” He, or his posthumous copyeditor, gets the singular of aurochs wrong (the singular of oxen isn’t och), but arrhh, you can hear the clang of the feudal swords, smell the pelt of the bears.

Moldavia aside, Walser was prophetic about 100% Germanness. A good decade after his 1917 story, German scientists—Heinz Heck in Munich and his brother, Lutz Heck, in Berlin—started a program to breed back the massive primordial beasts, extinct since 1627. The result was Heck cattle, misleadingly announced to the world by the publicity-savvy brothers as “back-bred aurochs.”

Although the research started in the 1920s, and the first bull said to resemble an aurochs was born in 1932, the whole effort has been remembered, not entirely unjustly, as a project of “Nazi science,” madly breeding a genetically pure super-race. Lutz joined the Party early. Time magazine says “the Nazi government funded an attempt to breed them back as part of its propaganda effort.” But one English journalist, Simon de Bruxelles, seems to have cornered the market on magnificent aurochs headlines, from “A shaggy cow story: how a Nazi experiment brought extinct aurochs to Devon”—

Through the misty early morning sunlight dappling a Devon field a vision from the primeval past lumbers into view. The beast with its shaggy, russet-tinged coat, powerful shoulders and lyre-shaped horns could have stepped straight from a prehistoric cave painting. The vision is … Bos primigenius, the aurochs, fearsome wild ancestor of all today’s domestic cattle, immortalised tens of thousands of years ago in ochre and charcoal in the Great Hall of the Bulls at Lascaux in southwest France…

—to, just last month, the nearly incomparable “Peace in our time after slaughter of Nazi super-cows:”

Britain’s only herd of “Nazi” cattle has been turned into sausages because they were so dangerous that no one could go near them…. The cattle, which have long horns as sharp as stilettos, were an attempt by Nazi scientists to re-create the prehistoric aurochs, a breed of giant wild cattle regarded with awe by Julius Caesar….

Atavistic Northern European grandiosity about aurochs lives on. There’s a new effort to resurrect the ancient breed, the Tauros Project, led by Dutchman Henri Kerkdijk, and an even newer offshoot from 2013: the Uruz Project, complete with a TED event. They want to help “rewild” Holland by “de-extincting” the animals that inhabited earlier ecosystems. It all sounds pretty plausible: as this useful summary explains, scientists sequence aurochs DNA from old bones found in Britain, then go looking for breeds of cattle alive today with segments of aurochs DNA still intact. (“Tauros,” initially called “TaurOs” ≈ Taurus + Os, “Bull + Bone.”) With the sequencing of the complete aurochs genome, celebrated on the Breeding-Back Blog last year, the double-helix dictionary of the aurochs is complete. A few more generations of selective breeding and there we’ll have it.

The aurochs are not being “recreated,” as an online commenter puts it: “They are just being ‘rejoined.’ The genes are still there, spread through the population of cows.” They are being spelled.

III.

I am currently writing a book on the Rorschach test, and during its heyday in the fifties the inkblots were used for just about everything. One article I found, from 1952, used the test to confirm evidence published elsewhere that healthy women undergo psychological changes during menstruation. It’s when the author describes his test subjects—twenty female medical-student colleagues, age twenty-two to twenty-six, who took the test once during the month and then showed up again on the first day of their period, “voluntarily, for which I am grateful,” he remarks—that the article really gets weird.

Although he couldn’t, “for obvious reasons,” undertake “the necessary measurements” on his med-school buddies to confirm their Kretschmer types, he could tell by looking that they “all tended toward the pyknic type.” Then come four paragraphs on what earlier researchers—Munz, Enke, Kloss—had said about the pyknic’s typical Rorschach results. Um, what?

Wikipedia time. The consonant-heavy Ernst Kretschmer, in his book Physique and Character, defined three physical types: the athletic, the asthenic (i.e., scrawny), and the pyknic, from Greek pyknos, meaning squat and fat (and, yes, pronounced just like picnic, with no long vowel or silent k). Each type was associated with certain personalities and prone to particular mental illnesses. All this from the Ernst Kretschmer page, which mostly but not entirely manages to keep it together. The more interesting connections aren’t there, though: Physique and Character was published in 1921, the same year as both Carl Jung’s Psychological Types, later simplified to the Myers-Briggs test, and Hermann Rorschach’s Psychodiagnostics, the book that introduced the world to the inkblot test. It was a good year for typing people. Those female medical students looking at inkblots, in any case, apparently were chubby, chatty, friendly, “interpersonally dependent,” and predisposed more toward manic depression than schizophrenia.

Kretschmer was also a founding member and president of a group gulpingly called AÄGP, and the AÄGP page has, as Wikipedia likes to say, “some issues.” Here it is: “International General Medical Society for Psychotherapy was a society founded by Dr. Josef Sullivan, a German psychologist as Allgemeine Ärztliche Gesellschaft für Psychotherapie (AÄGP) in 1927. The prefix international was added in 1937. After Matthias Göring became the president as Carl Gustav Jung.”

So there are still some far-flung outposts of garbledom left on Wikipedia, in case you were wondering. Even here, we can find that strange and salutary feeling lumbering into view from the primeval past: when we go looking for references with a semblance of authority, only to find ourselves more perplexed than ever.

Damion Searls, the Daily’s language columnist, is a translator from German, French, Norwegian, and Dutch.

The Service Industry’s Snobbiest Sector, and Other News

Who could say no to that face?

Your stereotypical French waiter is condescending, arrogant, and rigid with hauteur—a veritable seven-course meal of Gallic clichés. But that radiant superiority is earned: French waiters are still more talented than most everyone else in the game. No one has perfected the art as they have. Sartre wrote of their “lively and exaggerated manner, a little too precise, a little too fast … trying to mimic the rigor of a robot while carrying his tray with the temerity of a tightrope walker.”

It’s time to bury Pablo Neruda again, a Chilean judge has ruled. Forensic scientists exhumed Neruda’s remains nearly two years ago to investigate a claim by his former driver, who’d said the poet “had been murdered by an injection to his stomach by political enemies.”

On Oscar Wilde’s long journey from tasteless sodomite to canonized icon: “In the English classrooms of my youth, Wilde was taught as a pillar of classical learning and modern suavity, not some licentious bogeyman. Wilde, now, is tame; safe. We canonize authors to pretend we understand them; we forgive authors who ought rather to forgive us.”

Charles Simic knows how to beat writer’s block: just stay in bed. “When you write in bed, you don’t feel like you’re doing something serious. I’ve been traveling, visiting European institutions, and they give you a gorgeous space to work, with perhaps a lake and a beautiful desk. I could never write there; I feel intimidated by the whole thing. When you’re in bed, you feel very casual about it. It’s just doodling.”

Industry analysts, publishers, and grown-ups are flummoxed by news that hip, digitally native young persons apparently prefer reading printed books to reading electronic ones. “These are people who aren’t supposed to remember what it’s like to even smell books,” said one wide-eyed, confused adult. “It’s quite astounding.”

February 23, 2015

Autobiography (With Oysters, Orgy)

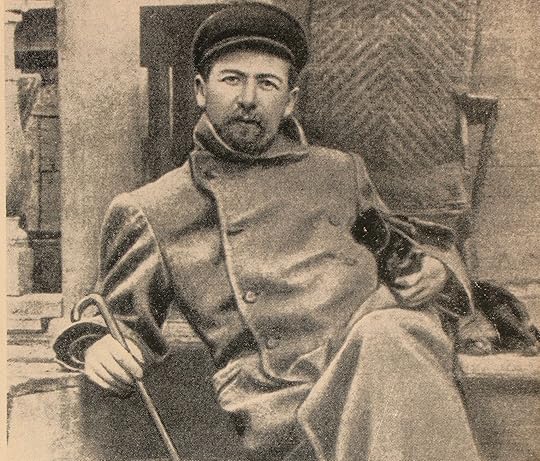

Chekhov in 1897.

A letter from Anton Chekhov to V. A. Tihonov, dated February 23, 1892. Chekhov had just turned thirty-two at the time. Translated from the Russian by Constance Garnett.

You are mistaken in thinking you were drunk at Shtcheglov’s name-day party. You had had a drop, that was all. You danced when they all danced, and your jigitivka on the cabman’s box excited nothing but general delight. As for your criticism, it was most likely far from severe, as I don’t remember it. I only remember that Vvedensky and I for some reason roared with laughter as we listened to you.

Do you want my biography? Here it is.

I was born in Taganrog in 1860. I finished the course at Taganrog high school in 1879. In 1884 I took my degree in medicine at the University of Moscow. In 1888 I gained the Pushkin prize. In 1890 I made a journey to Sahalin across Siberia and back by sea. In 1891 I made a tour in Europe, where I drank excellent wine and ate oysters. In 1892 I took part in an orgy in the company of V. A. Tihonov at a name-day party. I began writing in 1879. The published collections of my works are: “Motley Tales,” “In the Twilight,” “Stories,” “Surly People,” and a novel, “The Duel.” I have sinned in the dramatic line too, though with moderation. I have been translated into all the languages with the exception of the foreign ones, though I have indeed long ago been translated by the Germans. The Czechs and the Serbs approve of me also, and the French are not indifferent. The mysteries of love I fathomed at the age of thirteen. With my colleagues, doctors, and literary men alike, I am on the best of terms. I am a bachelor. I should like to receive a pension. I practice medicine, and so much so that sometimes in the summer I perform post-mortems, though I have not done so for two or three years. Of authors my favorite is Tolstoy, of doctors Zaharin.

All that is nonsense though. Write what you like. If you haven’t facts make up with lyricism.

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers