The Paris Review's Blog, page 43

October 25, 2023

Summer

Tove Jansson, Sommarön (Summer Island), n.d., pencil and gouache on paper, 24 x 15 cm. Photograph by Hannu Aaltonen.

Each summer, when they couldn’t stand the city anymore, when the heat was unbearable, and they had a brief reprieve, they drove for three days to the middle of the country to stay at a log cabin on a lake that her grandfather had built now a century ago and where she had spent summers during her childhood. Her father, her children’s grandfather, and his sister, her aunt, would drive up the eight hours from Chicago and spend a week with them so that they could be around her two small children.

The previous summer, in the week before her father and her aunt arrived, she was able to relax into the lassitude that overtook her from being there, and possibly as the result of the long series of days in the car, with two children to monitor and soothe and attempt to entertain. That summer, after having just finished a period of work, she spent most of the time on the bed in the newer room that the four of them stayed in. She would sit, on the old gray-green sheets, the dog curled up next to her, watching the two children and their father through the window, making notes in her notebook. She sat there amidst the green light of the lake and the surrounding green and sketched out the familiar geometry of the trees surrounding the lake, the fallen trunk the ducks often slept on. She attempted to sketch in pen the white pine tree directly outside her window, the surging upwards of the boughs, like a series of prickly mustaches.

The mother showed the drawings to her oldest in the morning, who became jealous of her notebooks scattered across the bed and demanded her own small notebook, which they later purchased in town, one for both of the small children. She wondered, then and now, if they would remember the sound of their mother’s pen, her illegible scratching that probably looked to them like the branches on a tree.

On their daily morning walk, they picked raspberries by the road, the littlest in wet overalls. Never in these woods growing up had she seen raspberries. She wondered whether it had something to do with the heat and heavy rains of the past years.

In the late afternoon, the sun was bright and hot. She sits with her notebooks and her copy of Tove Jansson’s The Summer Book on the front porch. There were windows on all sides of the cabin. Through the window, she can see the girls and their father at the blue rope swing and hammock in the nested area of the woods near the water, where her oldest has made a fort of long branches. She hears the children lightly fighting, the father’s warning tones. She thinks about the grandmother in The Summer Book, charged with the granddaughter while the father is absent, alone with his work or grieving, or both. The mother is gone, but we don’t know anything about her. The father is allowed to not be present, to also be a ghost.

She wonders whether she is the older woman companion, or the absent father, in this narrative. The children are less on top of her here, they are more free. She couldn’t hear them now. Where were they? Suddenly, they emerge from the woods.

The lake is dark and moves silkily as the afternoon turns into evening. She charts the different patterns. At night the waterlilies recede. She just sits at the window and watches the lake and the trees. In the morning, the lake can be incredibly still, like a mirror. The lake looks dark green, reflecting the trees. Her oldest comes in and shows her a drawing of a bird in her new notebook, without the usual smiling face. She had paged through The Summer Book and seen the illustrations of creatures—mouthless yet expressive. The eldest and her father read the book together during the toddler’s naps.

That morning they had seen a blue heron near the red canoe. It looked like a naked alien, or a dinosaur. It surprised her to see it up close. It took a large shit and flapped slowly away by the time the girls could get to the bedroom window. She ran out with her daughters to look at its excrement, like speckled white paint across the grass. Will you write that in your notebook? her oldest asked her. The other day, she told her mother to write the textures of the lake. Like the brown muck, she said.

How silent everything was—it seems to just be them, like they were the last people on earth. Sunday and no weekenders, save the drunken boaters Friday night trying to see the supermoon. Almost no one on the sparkling lake. The retired town doctor and ER nurse that live across the way come near on kayaks. Sometimes they wave. The curiosity of the boaters that come nearby, like the dreaded pontoon boats. You can hear the voices before you see the people appear, coming closer sometimes to see who is there. She knew they were supposed to wave. They hated these boats, hated the interruptions.

Everything mostly silent except the birdsong The oldest sits at the rocking chair and deliberates on a large and speckled feather from a walk, poring over one of her grandfather’s bird books. Owl or woodpecker, she decides. They counted fourteen ducks on the lake that summer, learning how to fly. The mother sat on the bed looking out at the lake through the window and made spiral drawings of the ripples of the lake. How it can move rapidly.

On their last day by themselves, before their grandfather and great aunt arrive, they sunbathe nude on the dock, her and the two children, the pale moons of their little butts. She knows that all of this solitude will be gone in a few hours. Her peace punctured. The stomping around. The shuffling of slippers. The sighs. Having to remark on everything. But the children are so happy with them, pleased to have family.

There was so much of her oldest, who was then almost six, that reminded her of the child in The Summer Book—her curiosity and independence, but also how she clung to the two elders on the front porch, wanting them to play with her, wanting to chat at them. The aunt, who was actually her great-aunt, had brought a ball of yarn and needles to teach her how to knit, as she had done when she herself was a child. She wasn’t sure exactly what her oldest and her grandfather did or talked about during the hours of nap—she was relieved to have family watch her children.

Tove Jansson, Ensittaren (Recluse), 1935, pastel on paper, 66.5 x 49 cm.

They made sure the grandfather went for a walk down the road every day, sometimes holding the hands of one of his grandchildren, naming the wildflowers on the side of the road.

On the walk, they stopped to check out droppings and animal tracks. The large black mound with fur, acorns and berries in it was most likely Bear. They had witnessed while driving in one day from town two alien creatures running down the road, which they were convinced were wild turkeys. She drew the bird tracks later in her notebook. With the grandfather, they stopped at a burrow on the road and stared at the strange hole, trying to imagine the mysterious creature inside. A badger, the grandfather decides authoritatively. So many creatures that summer. The fox in the middle of the road they saw while driving. The mouse in a cup in the sink. The red ants in sand hills on the road and around the trash can.

On their walk, the grandfather looks with pleasure at the baby pines going up by the road. Red pines and jack pines, he pronounces out loud. He’s allowed a large part of the forest to be cut down by a logging company, which has also carted away the dead trees at no fee. Her father looks at trees the size of small humans and feels optimistic, but it is a source of tension with his youngest daughter, the now middle-aged mother, that continues into the next summer.

The aunt never goes on the walks. She sits there with her large glass of milky coffee and straw and her knitting or her stories on her device. At a certain time she switches to decaf. She has always been an old woman, even when her nieces and nephew were very young, and she was only in her late twenties and thirties, and lived forever in that house in the other city with her other brother and her mother. Now, she takes her mother’s place, and sits at the sliding loveseat that used to be a swing, and watches. The women up at the cabin are supposed to be the ones watching through the windows, while the men and children have adventures in the immediate vicinity. When the lock breaks, the men focus on fixing the doorknob, and the mother is called into being a panopticon for the children. The plant position, to plant yourself in front of children. Like the woman is a tree. Although she was the one to also chase after them.

The next summer, they spent the first week with the grandfather and aunt, which took away the ease she usually felt upon reentering the lake and the woods, their little island. They were already on the rhythm of the others, and the silence was marred by constant voices. For most of the summer her father and aunt would be up there alone, sitting on the newly built front porch—newly built meaning much more than a decade ago—looking at the lake, remarking upon the birds that arrived at the bird feeders, such as the hummingbirds who came to drink the sugar water in the jewel-red feeders. They must name the blue jays, the grackles and the hummingbirds. Oh, look, a goldfinch. Two hummingbirds. They must be hungry.

They didn’t cringe at the increasingly occasional pontoon boats, instead waving at them. They didn’t mind intruders, which they saw as company. Very slow season on the lake, the aunt said.

At the beginning of the week a man came blazing up their road in a vehicle, from one of the more brutish clans that had hunting camps closest nearby, and offered to widen the road, which her father agreed to. As soon as she saw the older, athletic man out there talking to her father, she froze in the doorway and backed away. She was hoping to go out to check up on the children with their father at their swing. The grandfather was uncomfortable seeing the fort that the almost seven-year-old had built over consecutive summers, which he hadn’t noticed. He was worried it was a fire hazard. That was his new obsession—the dead wood, which is why he let the trees get cut down, why he let this man leave a mess of branches widening the road so that, he said, the firetrucks could get in if they needed to. There had been serious fires in this forest in the past, but the recent vigilance seemed to be a response to that summer’s fires in Canada, but not, for her father, mixed with anxiety about warming, which he professed to not believe in, or want to think about. She found herself wondering again whether her father was a good steward of the land.

They settled into a pattern of making meals for the older relatives, of encouraging the grandfather on a late afternoon walk, the children often whining that they wanted to play instead. The sight of their neon t-shirts against the sand road. Wearing the toddler on the mother’s back until she complained and wanted to run after her sister. There weren’t any berries at all on the side of the road this year, at least not yet.

There was an identical feeling to last summer. A palimpsest feeling, especially in the notebooks, the repetitions of the two summers. Only subtle changes. And that everyone was a year older.

She wonders often whether writing in the third person makes the “I” a fiction. Does it make her less real, she wonders?

Because they were up this summer earlier than usual, they kept picking ticks off themselves, which were crawling all over them, including the toddler’s tender arm.

The grandfather wanted them to take him on the boat to see the outlet which bisected his property. He had been fragile since falling the previous winter, outside of a restaurant, and didn’t want to get into the boat without help, which he did, slowly, hanging on to the dock and grunting. The little girls sat in the middle in life jackets. He wanted to see if the pines that were planted were still growing. They were not. Why did you let them cut the healthy ones down? the daughter said again, causing, as usual, prickliness. Well, the loggers weren’t going to just take the dead ones, he said. The water levels are high again, that was good, he said.

When the grandfather and great aunt left, one week later, the children were sad, but the mother was finally able to relax, to look onto the lake, still as glass, with the upside-down reflections of the empty cabins. Then the lake begins to ripple, the double world vanishes. The mother watched the oldest make crayon drawings, her back facing the lake. A house with a triangle roof, just like she was seeing now. Then a large tree. The self is wearing a triangle skirt. The self is as big as the tree. The summery light on the lake. Sweating. Saturated blue and green. Swaying of grasses, ripple of water.

One cooler morning she watches from the window the children with their father on the dock. Pleasure at the red overturned canoe, the red hummingbird feeder, even the red stripes of the flag her father buys every year to hang out there. The water bugs make ripples. The children are trying to catch fish with nets. The littlest captures a small fish. Her net gets caught on the splintered dock. The mother calls out, worried the little one is going to trip. It was like this for her mother, and her grandmother—the women sitting there watching. Her holler matching her grandmother’s. Eventually the toddler falls in the shallow end and emerges weeping, her yellow cotton sweater dripping. The mother runs to help as they pull off soaking wet pants, sweater, shoes, lay them out to dry.

It was perfect weather, after the storms when her father and aunt were here. Not hot. Cold at night, cool in morning. Earlier in the morning she watched two girls make their “pasta soup” in a metal bowl—ferns, weeds, pinecones, dirt, crumbled pieces of bark.

They can walk farther now that the grandfather is not with them. They take a morning walk to the other side of the lake, wearing long sleeves and pants to avoid insect bites, the mother wearing the toddler on her back, the oldest child managing the dog leash, moving to the side of a road when a truck or aging sports car came roaring around. They admired the elaborate signage of the houses more crowded together on the other side of the lake, the solar panels, the modern-looking cabins with Swedish and Finnish flags. Their family, even though they owned most of the lake for a century, did not get nice things. Her father and aunt used the same chipped ceramics that their mother had gotten free in a spaghetti catalogue. When they brought new beds, which they finally did after about forty years, they got the cheapest quilts.

Talking to each other, the parents remarked on this, on the specific sounds of the rustling birch trees, that there are so many less crickets on the sandy road.

When they return, the oldest begs for the mother to go swimming with her, but the youngest needs to be put down to nap. The mother watches the oldest sitting on the splintered, now sunken dock, the bench covered in lichen and bird shit. Her feet in the water, the spirals the water makes. She is waiting with the net, watching for the fish. It surprises the mother, how imaginative and solitary her oldest has become, their secret world here.

In the afternoon, after the toddler’s nap, they finally took out the canoe as a family. The oldest complaining she was not allowed to row, but the mother wanted to, like she had as a child. The children sat in the middle of the boat, in their life jackets, exclaiming over spiders and large ants on the floor. They traced the edges of the property, towards where she had remembered there was a beaver dam when she was a child. Apparently, there was a new dam, in the outlet, which they rowed towards to try to see. Another source of tension between the mother and her father, the grandfather. The father was letting one of the neighbors, who all hunted, try to shoot the beavers. The two adults remarked that in the past the outlet used to be dry, all muck. Now there were so many lily pads. And the ducks sheltered there. It comes as a shock, like a pain, seeing again the thinning trees. What must the other inhabitants of the lake think, she now wondered, to have their view so altered?

When they got back, almost as if to shake herself of this melancholy, she stripped down out of her overalls to her underwear, delighting and surprising the children milling about the shallow side of the water. Later, all three of them naked, as there was no one around, she watched the children climb the overturned boats on the shore, playing pirates. It was like they were the only people in the world. A joy watching them be free, like a relief.

Tove Jansson, Rökande Flicka (Smoking Girl), 1940, oil on canvas, 41 x 33.5 cm.

From the exhibition catalogue for Houses of Tove Jansson, on view at Espace Mont-Louis in Paris through October 29, 2023.

Kate Zambreno is the author most recently of The Light Room (Riverhead, 2023) and Tone, a collaborative study with Sofia Samatar, published next month from Columbia University Press.

October 23, 2023

The Future of Ghosts

Image of a ghost, produced by double exposure, 1899. Courtesy of the National Archives and Wikimedia Commons.

There’s a theory I like that suggests why the nineteenth century is so rich in ghost stories and hauntings. Carbon monoxide poisoning from gas lamps.

Street lighting and indoor lighting burned coal gas, which is sooty and noxious. It gives off methane and carbon monoxide. Outdoors, the flickering flames of the gas lamps pumped carbon monoxide into the air—air that was often trapped low down in the narrow streets and cramped courtyards of industrial cities and towns. Indoors, windows closed against the chilly weather prevented fresh oxygen from reaching those sitting up late by lamplight.

Low-level carbon monoxide poisoning produces symptoms of choking, dizziness, paranoia, including feelings of dread, and hallucinations. Where better to hallucinate than in the already dark and shadowy streets of Victorian London? Or in the muffled and stifling interiors of New England?

Ghosts abounded—but were they real?

Real is a tricky word. It is no longer a three-dimensional word grounded in fact. Was it ever? We are living in a material world, but that is not our only reality. We daydream, we imagine. Everything that ever was began as an idea in someone’s mind. The nonmaterial world is prodigious and profound.

You don’t have to be religious, or artistic, or creative, or a scientist, to understand that the world and what it contains is more than a 3D experience. To understand that truth, all we have to do is log on. Increasingly, our days are spent staring at screens, communicating with people we shall never meet. Young people who have grown up online consider that arena to be more significant to them than life in the “real” world. In China, there is a growing group who call themselves two-dimensionals, because work life, social life, love life, shopping, information, happen at a remove from physical interaction with others. This will become more apparent and more bizarre when metaverses offer an alternative reality.

Let me ask you this. If you enjoyed a friendship with someone you have never met, would you know if they were dead? What if communication continued seamlessly? What if you went on meeting in the metaverse, just as always?

Already, there are apps that can re-create your dead loved one sufficiently to be able to send you texts and emails, even voice calls. And if you both entered the metaverse in your avatar form, there is no reason why the “dead” avatar couldn’t continue. Truly, technology is going to affect our relationship with death. In theory, no one needs to die. In theory, anyone can be resurrected. We can be our own haunting.

Humans are terrified of death. Will technological developments allow us to avoid its psychological consequences? Or will it give us a new way to go mad? By which I mean to detach from the world of the senses into the metaverse?

And does it matter? If Homo sapiens is in a transition period, as I believe we are, then biology isn’t going to be the next big deal. We are already doing everything we can to escape our biological existence—most people barely make use of the bodies they have, and many would be glad to be freed from bodies that are sites of disappointment and disgust.

Perhaps we are moving steadily toward the nonmaterial life and world that religious folks have told us is the ultimate truth. This time around, we won’t have to die to get there—we join the metaverse.

There are plenty of horror stories about evil spirits impersonating the newly dead. I wonder if spirits of all kinds will infiltrate the metaverse? I am being playful here, but how would we know if a being in the metaverse had a biological self or not?Why wouldn’t ghosts hack the metaverse? Surely it will feel like a more user-friendly, at-home space to them. The metaverse exists, but at the same time, it occupies no physical space. Ghosts exist (maybe), but they have no physical being. Tangible reality is getting old-fashioned.

Once the hard boundary between the “real” world and other worlds comes down—and that’s what the metaverse intends—being alive matters less. Once the physical body becomes optional, where does that leave ghosts?

A ghost is the spirit of a dead person. An avatar is a digital twin of a living person. Neither is “real.” A haunted metaverse. Why not?

In a sense, the Plato sense, materialism is about the hard copy. It is impressive. But it is still a copy.

In other words, we are living in Toytown, and we mistake the substance for the shadow. The substance isn’t what we can touch and feel—and we know we are not actually touching or feeling anything; that’s an illusion. Substance may not be material at all.

Shakespeare put it this way, in sonnet 53: “What is your substance, whereof are you made / That millions of strange shadows on you tend?”

I don’t want to get into Shakespeare’s Neoplatonism here—which is what those lines swirl around—but I do want to get into the fact that computing power and AI have left multimillions of us wondering what is real, in the old-fashioned sense of the word. This will only get faster and stranger as we enter the metaverse; a virtual world with digital twins in our world—or the other way ’round, if you prefer.

“What is your substance, whereof are you made?” This could be addressed to a human. Or a transhuman. Or a post-human. Or an avatar. Or a ghost.

This essay is an adapted excerpt from Night Side of the River: Ghost Stories, out from Grove Press tomorrow.

Born in Manchester, England, Jeanette Winterson is the author of more than twenty books, including Why Be Happy When You Could Be Normal?, Oranges Are Not the Only Fruit, 12 Bytes, and The Passion. She has won many prizes including the Whitbread Award for Best First Novel, the John Llewellyn Rhys Prize, the E. M. Forster Award, and the Stonewall Award.

October 20, 2023

Remembering Louise Glück, 1943–2023

Louise Glück’s studio in Vermont. Photograph by Louise Glück. Courtesy of Richard Deming.

Requiem for Louise

We were supposed to meet Louise Glück in New York, at the end of September, to see Verdi’s Requiem at the Met. My husband and I wanted to see Tannhäuser. Louise wanted to see the Requiem, and she was insistent. We decided to hear both, and I was tasked with procuring the tickets.

Louise clearly did not have faith in my ability to achieve this, and I received a number of anxious emails in the lead-up to the day on which individual tickets became available for sale. Would the seats be any good? What would they cost? And, once I had finally purchased the tickets: Now, where are we going to eat?

All summer long we exchanged emails in anticipation. Listening and listening to recordings, comparing our favorites. Louise told us about attending productions as a young girl, becoming enchanted with the music, the drama, and the atmosphere of opera. “I’ll restrain myself from singing along,” she said.

As the day of the concert approached, Louise reached out to say she was feeling sick and might not be able to go. Then it was official; she had to cancel her trip. Massive deprivation, she called it.

My husband and I went; a lovely friend filled in last-minute. The chandeliers sparkled. The audience coughed. In the darkness of Lincoln Center, the music shook us with its beauty and drama. It’s a huge choral work—too large for a liturgical setting and often undertaken by opera companies—with passages of real terror (and the biggest bass drums you’ve ever seen) and passages of quiet, despairing supplication.

Exaudi orationem meam:

ad te omnis caro veniet.

Hear my prayer:

all earthly flesh will come to you.

As I listened to the chorus, and watched the translated titles before me, the poetry of the piece struck me. Even though I’d read those lines over and over, this music made the poetry sensuous, felt.

Louise waited until after the weekend to tell us that she had been diagnosed with cancer the day before we had intended to see the Requiem. “I hadn’t wanted to tell you immediately and spoil the concert,” she told us.

It was the last we heard from her. I can’t stop thinking now about how much I wish she had been able to hear the Verdi. I can’t stop thinking about the terrible irony of having to miss a requiem in order to die.

Also, how like the text of the Requiem Mass her own poetry could be—lines of crystalline beauty, simple in utterance but heavy and resonant with moral authority and mortal truth. True lyrics, what Helen Vendler has called that “genre for literary aria,” with the full range of human interiority: entreaty, wrath, confession, and prayer.

Little soul, little perpetually undressed one,

do now as I bid you, climb

the shelf-like branches of the spruce tree;

wait at the top, attentive, like

a sentry or look-out.

Like Verdi’s Requiem, her poems are somehow both enormous and intimate. Not stuck there on the page, but always a voice, ethereal and alluring, that rises like music up from it.

Let’s play choosing music. Favorite form.

Opera.

Favorite work.

Figaro. No. Figaro and Tannhauser. Now it’s your turn:

sing one for me.

—Richie Hofmann

“And the Sun Says Yes …”

1. Louise was a connoisseur of the specific. I don’t think I ever had a dinner with her at which she didn’t ask for a different wine after sampling a glass. She didn’t like Orson Welles’s movies because she didn’t like the way he furrowed his brow. Her favorite gift that she received from me and my wife was either an elegant pair of scissors or four teak sticks for stirring salt in a cellar. Had I ever called her a connoisseur of the specific in her presence, she would have pointed out that it wasn’t wrong, but was far too general.

2. In September of 2002, Yale’s Beinecke Library and Whitney Humanities Center put together a festival for all the living recipients of the Bollingen Prize at a packed church on the New Haven Green. So many people attended that a live feed was projected in the church next door, and that was standing room only as well. The first reader was John Ashbery, whom I had not seen give a reading before, and he had been the brightest star in poetry’s firmament for almost my entire life. He read well—I forget what—and when he finished, for some reason, instead of returning to his seat on the stage established at the front of the church he drifted down to the pews and plopped himself next to Penelope, Robert Creeley’s wife. The next to read was Creeley himself, who was in part the reason why I had become a poet—he had been my teacher and was in fact why I’d dragged my beloved to live in the snowy, snowy environs of Buffalo for three years. Bob read beautifully, with a stolid, craggy elegance. He too drifted down to the pews, afterward. The stage seemed noticeably emptier. It was Louise’s turn. At that point, I wasn’t that familiar with her work. Back then, I was perhaps too ensconced in a polemical need to be edgy and avant-garde. I had heard she was okay as a reader, though not great. Someone told me she had pioneered the Iowa “uptalk” reading style that dominated poetry in the nineties. On the other hand, my beloved—one of the organizers of the festival—had risked driving from Buffalo to Rochester one night a few years before, in the middle of a blizzard, to hear Louise read. They’d closed the thruway before they even hit the Buffalo city limits, however, forcing them to turnaround. Nancy barely made it back.

Louise stepped to the podium. I picked up a program and began to leaf through it distractedly. Then she began to read “October”: “Is it winter again, is it cold again.” From that first line, she leveled the room in a way I have never seen a poet do before or since. The poem was—and remains—a revelation. Not Romantic, not stormy or angsty or moralizing—it was resolved, insistent, fierce but focused. Her voice enacted what language could do for us, what it could do with us.

3. My favorite photo of Louise is one of those “live photos” that captures motion just before and just after the picture is taken. We are crossing the historic Annisquam Bridge in Gloucester, Massachusetts, that spans four hundred feet across Lobster Cove. It is nearly dusk, and the late-August light drifts into shadows among the sailboats and pylons.

Nancy, walking a few feet behind us, must have called out. I step out of frame. Turning toward the camera, Louise’s face, for a moment, becomes wide, surprise-filled smile. She then glances off-screen and the sly skepticism creeps in at the corners of her eyes. She asks, “Now what are we doing?”

4. Now, memory: she steps forward again, onto that wooden bridge. I hear her voice—softer, then softer. She is saying something to Nancy, something about rain or light or wine. Soon, too soon, she’s on the far shore. We’re here. Now what are we doing?

—Richard Deming

Hello. It’s Louise.

“Hello.” Pause. “It’s Louise.”

Her phone-machine messages, back when people had phone machines, began that way, with an enjambment. Her name came as a comic redundancy after the surprisingly deep and gravelly greeting, which of course was unmistakable.

Part of what was funny was the slight suggestion of apology in her admission that it was she calling—again, as it were. She knew—and knew her listener knew—that what was coming would involve a demand of some kind, flimsily disguised as a preference or proposal. She didn’t call just to find out how you were.

She did, however, want very much to talk to you, to see you. In fact, it was so important that the day, the hour, and the place of your dinner had to be established weeks and sometimes months in advance.

Before she signed off, there would be a few more pauses and pivots, a few more line breaks.

***

Louise’s need to control her calendar was expressive of her acute awareness of passing time and her will to fight it.

Time was the engine of her extraordinary will, her drive to say something permanent in poetry, to win all those prizes. Behind her resolve was a certain terror. She knew that choices matter in life and on the page because we have only so many of them. She saw us all as moral creatures obliged to make the best of our days, however best might be defined. Most of us fail at what we do with our time. She was determined to be different and so she was.

Age, the seasons, families, memory, death—maybe time is what her poetry is all about? The slow, daily emergency of the clock.

***

While time is a central theme of Louise’s poetry, timing is basic to the form of it. Timing is a matter of syntax: how sense unfolds in language. Syntax is everything in Louise’s poetry, where there is a good deal of complex sound-patterning, but no rhyme or meter and little of what might conventionally count as lyric song. She was allergic to these commonplace features of traditional verse, which stunk of inauthenticity, mere performance. (That attitude puts a sort of time stamp on her work, locating her beginnings in the late sixties.)

Her own technique heavily relies on enjambment and the grouping of lines in stanzas. These provide a visual structure for the drama involved in speaking.

Not stage directions exactly, but a way of measuring language through which we hear her weighing what she is saying while she’s saying it. Testing its truth, her reader judging with her. Thought opens in the beat between one line and another. The white space of the page is part of the poem. Part of the sound of it.

***

Only two American-born poets have won the Nobel Prize for Literature, Louise and T. S. Eliot. Eliot, who wrote lyric poems as dramatic monologues, fruitfully complicating the relationship between poet and poetic speaker, seems to me the crucial model for Louise’s poetry.

In an essay on Eliot written many years ago, Louise declared, “I read to feel addressed.” It follows that she wrote to address a reader. Psychoanalysis was one of the deep sources of her creativity. I don’t mean psychoanalytic theory or motifs, although there is plenty about parents and children and their tribulations in her poetry. I mean psychoanalysis as a speech situation in which one person addresses another with truth at stake, and in which words, our untrustworthy words, are the only way to get at it.

“My preference, from the beginning, has been the poetry that requests or craves a listener,” Louise writes in an essay about her literary education. “Let us go then, you and I”: Louise makes the same invitation to the reader, but she is hungrier, more ready to admit her hunger, to place her demand, than Eliot. She says craves.

***

For a while, Louise pretended not to read on a screen or do email, at least officially. Eventually she made friends with her iPad, and she became a rapid responder. I can’t replay those phone-machine messages from long ago, but I can reread her emails and texts. She tended to sign off “XL.” Extra-large? Of course not. Don’t be silly. Excel, she was saying. That was what she was driven to do. It is also the challenge she left to the rest of us. How like Louise to turn her embrace into an imperative.

—Langdon Hammer

Richie Hofmann is the author of two books of poems, A Hundred Lovers and Second Empire.

Richard Deming is the author of five books, including This Exquisite Loneliness, Day for Night and Art of the Ordinary. He teaches at Yale University, where he is the director of creative writing.

Langdon Hammer is the Niel Gray Jr. Professor of English at Yale and the author of James Merrill: Life and Art.

October 19, 2023

Real Play

Autumn, Sims 2. Courtesy of Lucie-Bluebird Lexington. Licensed under CC BY 2.0.

I played The Sims a lot as a preteen. It was the only computer game I ever liked that didn’t involve horses, and it lived at my dad’s house, where screen time was not limited. My friend Diana had it, too, and she and I played together sometimes, in the small office connected to her parents’ bedroom. Diana liked the design element of the game, and would use cheat codes to make her Sims very rich, then build them big houses. She chose balconies with glass railings, and reupholstered her Sims’ furniture.

That part was not interesting to me. My Sims were not allowed to use cheat codes. Instead, they had to succeed within the terms of my own life, or what I imagined it would be as an adult: they had to get jobs, learn skills, and build relationships. They spent time learning to cook, mostly by reading the cookbooks on their bookshelves. They paid bills that arrived in the mailbox, and redid their kitchen floors only if they made the money on their own. Everyone got a smoke detector, and I worked hard to help them keep their Need meters—Hunger, Bladder, Social, Fun, Energy, Hygiene, Comfort, Environment—in the green. If not given instructions, Sims will do their best to handle these needs themselves, electing to use the bathroom or play on the computer. But I liked to do it for them, sending them to the fridge if they were hungry, to bed if they were tired, and to another Sim if they were lonely.

At my dad’s, I started with the first edition, The Sims, which came out in 2000. That one had only four angles available, each ninety degrees apart, in which I could look down and out (and through the walls) of my Sims’ square houses, at three possible levels of zoom. The game was very gridded: furniture could only sit within blueprinted squares, never diagonally. Cockroaches, when they came, crawled in circles within one square only. The cheapest flooring option was black-and-white linoleum tile, which I sometimes used for my entire house, and on which the cockroaches would spread, in a grid, if I didn’t kill them.

The Sims 2 came out in September 2004, when I had just started fifth grade. I think I got it right away—I remember I was excited—though I’m surprised, now, that I had access so early to a game that I mostly remember in terms of where I could make my Sims WooHoo, their term for sex: bed, hot tub, shower. They were very demure, and would go under the sheets, or underwater, or behind the door, and then become pixelated. Still, though: there was a lot of WooHoo, and eventually a lot of Try for Baby, which would, in The Sims 2, sometimes lead to infants, then toddlers. The toddlers grew into children, whom my adult Sims could Help with Homework. Eventually these children became teenagers, and got boyfriends, girlfriends, pimples, and the desire to run away.

Sims, like people, live in networks of relationships. For the Sims, these were scored on a range of -100 to 100, based on formal ties (Family Member, for example) and past interactions. Certain interactions became possible if a relationship was particularly negative—Fight, Declare Enemy–but I didn’t want my Sims to have enemies. I wanted them to have Friends, then Crushes. I wanted them to Fall in Love–symbolized by red hearts, which would spin around their heads–and I wanted them to Get Married, succeed in their careers, make babies, and become good artists. I liked to have them Practice Painting, and then, when they were good enough, just Paint. I liked to see what they made, and sometimes I put their art on their walls, to improve their sense of Environment.

I would note that I was playing this game for six or seven hours at a time on a big black laptop of my dad’s, at his kitchen table, on otherwise undefined Saturdays and Sundays. Without imposing any intention on my younger self, I can say, factually, that I was engineering for my Sims what I considered to be normal family lives. I wanted them to live near beautiful trees, and to have gardens. I wanted them to be good artists, and I wanted them to not die until I said so. Because of this, I obsessively saved my gameplay, even though it took a minute every time. The unexpected could always happen. My Sims could get eaten by magic plants, which looked like cows. Aliens could abduct my Sims and return them pregnant. Sometimes Death, a sort of nonplayable character, would show up at my door and come in to eat a sandwich, if he didn’t have other plans for me or a member of my family. There were professional dilemmas, which sometimes seemed rigged against good outcomes. If anything went wrong, or did not support the healthy and expected development of my Sims’ growing families, I wanted to be able to exit the game and return to the last save. The gameplay didn’t have a sense of fate: lightning almost never struck twice, and with my consistent effort, my Sims could usually live the lives I wanted for them.

I don’t seem to share this gameplay experience with most former Sims players I know. Usually, when The Sims comes up, people talk about the ways they would kill theirs. The classic was to put them in the pool, then delete the ladder, and watch their Energy deplete as they swam in circles and waved at us, through the screen, asking for help. I did not do this.

Instead, I planted aspens, Japanese maples, and willows on my Sims’ properties, which I think of, often, when I see them real life. Socially, I still think in terms of clickability: who feels clickable to me, and what will become possible once I’ve decided to click. Sims can only initiate certain interactions (Make Out, WooHoo, Fight, Confess to Cheating) if they already have a certain degree of connection and history with another Sim, as designated by the points system, and occasionally by descriptors such as Acquaintance, Just Met, Best Friend Forever, or Going Steady. The interacted-with will respond positively or negatively to another Sim’s social advances based on their prior conception of that Sim, or the strength of their relationship. At my recent birthday party, everyone felt extremely clickable: I saw people I wanted to interact with, and the interactive possibilities, once clicked, tended to fan out into the positive. I was confident that whatever interaction I chose would likely go well and that I would leave with a very full social meter, as well as a positive memory.

Memories were a new feature for The Sims 2, and they existed in unweighted timelines. Burned Toast could be beside Fell In Love, or Got Fired, or Burglar! While these were important for my Sims’ personal histories, I, too, was obsessed with documenting my Sims’ lives. There was a Camera feature, available to the player, which would allow me to capture moments that felt, to me, important. Typically these were first kisses–which I would frame near the willows, getting multiple shots of the same moment from different angles—and weddings, and playing with babies. I especially liked when they fed wedding cake to each other. It didn’t matter that I could repeat any moment, or that the gestures were always the same: documenting these moments felt urgent. These photos were stored in an album only I could see, and which I never looked at. No one looked at it: my Sims didn’t even know it was there. They didn’t get cameras, or if they did, I don’t know what they did with their photos. I don’t know why I did this—social media wasn’t a thing yet, and I didn’t like photography in real life. Now I’d like to see those albums, if only as an archive of what I thought, at twelve, would eventually be worth remembering. The photos probably do live on a disc in a box somewhere in my dad’s house, so I guess it’s possible I could find them, which I might try to do.

If that disc is there, the Sims I made and knew so well are there, too, unchanged since we last interacted. I gave them up around seventh grade, without any ceremony. One day I told my dad that I felt I had to stop playing: that eventually my Sims’ lives would start to substitute for my own. Thirteen going on fourteen, I could see that I was approaching the point in life where things were supposed to happen to me. If I continued to play at being other people, I might not figure out how to do anything myself. To WooHoo, for example: I might never actually WooHoo if I spent so much time taking dirty pictures of fake people WooHooing, especially since they went under the covers, and I couldn’t see anything at all.

I told myself, though, that if I ever became seriously injured, ill, or confined to bed for an extended period of time, I could download The Sims again. I figured there would be nothing better to do, or that I would at least have earned it—via my discomfort, or enduring whatever had happened. Fourteen years later, when I was twenty-seven, I was suddenly facing two months of lying down. I downloaded The Sims when I got home from the hospital.

By then, we were onto The Sims 4. I started my Sim off the same way as always: she looked like me, and though there were new personality factors to manipulate (rather than ten-point ranges, such as Grouchy to Nice, I now had to choose descriptors), I tried to make her someone I wanted to be. I think I made her Creative, and a Genius, and potentially Good, though I might have chosen Bookworm instead. When she got to her new square house, I made her Read cookbooks, then Find a Job on the computer. She paid her bills, sometimes after she left them on the floor. She did not have a roommate, and she wasn’t trying to have kids, at least not immediately. When she had the time, she Practiced Painting until she was good enough to just Paint. If she had the energy, she Practiced Writing, and eventually, she began to Write Book. Her aspirations were not so explicitly career-based as they had been when I was younger, which I guess is nice, though she did struggle, having moved to a new place, to make friends.

It turned out, for me, that The Sims was a terrible game if I had to Go To Work, Pay Bills, Cook Dinner, and Clean Counter in real life. My Sim was always getting hungry, burning toast, and stomping her feet. Often it took so much time to Go To Work, Sleep, and Eat from the plate she left on the counter that she’d start to smell bad, and would take a shower without me telling her to. None of these things boosted her Fun need meter, and the things I did in my free time, ostensibly for fun—Practice Writing, and Paint—weren’t fun to her, at all. Her Fun meter was always in the red, and she’d give up on her writing and painting before I told her to. I ended up buying her a nice bookshelf—for +5 Fun points, out of a possible ten—but she didn’t think reading was fun, either. She left her books on the floor and started waving at me with a thought bubble over head, inside of which there was a television.

I didn’t want to buy her a television, because I didn’t have a television. I told her to Go to a bar in town, but she didn’t have Fun there, either. She did invite a non-playable character home, but when they got there, she didn’t seem very interested in him, and instead played on her computer. The NPC didn’t seem to mind. He spent the hours until dawn picking up her books from the floor and putting them in her nice bookshelf. Then he went home.

I didn’t take any pictures of my new Sim’s life. It seemed both boring and exhausting, the way she tried to take care of herself while also maintaining a social life, not to mention a creative practice. None of her art was very good, and I didn’t get to read her writing, which she didn’t like to work on. She was always so tired. I guess I could say it was an affirming experience; I was already living the life I would want to design; there wasn’t anything I really felt I needed to explore virtually, or at least nothing that was available via this Sim, who really complained a lot. I ended up returning the game within forty-eight hours, which meant I got a refund. After that, I used my computer to watch a lot of television, and read a cookbook Diana had mailed me, to be nice, since I was injured. She’s an interior designer now.

Devon Brody is a writer living in Nashville.

I’m High on World of Warcraft

The city of Thunder Bluff in World of Warcraft. Screenshot from the game.

It was about four in the morning when the warrior decided to leave our group. He’d started weeping, apparently, into his mic. I didn’t have a headset, but the other members of the group did, and they detailed the player’s breakdown in the chat. He couldn’t take the pressure, they said. He was sorry. He’d let us down. He was tired. He was blubbering now. He left the group and opened a portal to Stormwind, his home city. The rest of us waited a few minutes, trying to think of a way to replace the most important member of the group before giving up, surrendering the hours we’d spent working our way through Uldaman, a subterranean dungeon filled with cursed Dwarves. I stood up and took two steps away from the computer to lie down in bed and stare red-eyed at my character on the screen, which was now lit by the late-summer sun breaking through the bedsheets nailed vaguely across my windows.

I think about World of Warcraft nearly every day, but considering the millions of people who play the game, I’m not alone. Launched in 2004, WoW is the most successful MMORPG (massively multiplayer online role-playing game) ever. At the height of its popularity, in 2010, the game had more than twelve million active subscribers and continues to be the most played MMORPG today, almost two decades after its release. The game is so well populated that whole books have been written on the game’s sociological aspects and in-game economy. The objective of the game, if you could say there is a single objective, is to increase your character’s level. You do this by completing quests, raiding dungeons, and fighting in player-versus-player (PvP) combat, as well as engaging in the literally hundreds of other tasks and story lines the game contains, all of it taking place within the vast world of Azeroth, with each player’s character being a combination of a race (orc, troll, night elf, et cetera) and a class (shaman, mage, warrior, et cetera).

I got the game for my thirteenth birthday, in March of 2005, and somehow managed to play only occasionally until that summer, when I became hopelessly addicted, often playing for upward of fourteen hours a day. The addiction lasted through the summer, during which I rarely bathed, ate, left the house, or did anything but play WoW. By fall my room was littered with rotting food and unwashed clothes, and bedsheets covered my windows. I didn’t consider myself to be addicted, but dedicated. I cherished the fact that I was capable of spending my time doing just one thing. My favorite moment of the day was when I wandered through the silent house at dawn after a fourteen-hour session, impressed by the feeling of remembering what it felt like to walk. I’ve rarely been happier than I was during that time.

Most of my time in Warcraft wasn’t even spent questing, but simply “exploring” the game—walking my character across Azeroth’s forty distinct in-game zones while listening to music or imagining my own story lines. I spent whole days walking through the World with an almost obsessive fascination and appreciation for the game’s atmosphere: its infinite pixelated horizon, its endlessly looping orchestral music. Often I would just stand still and rotate the in-game camera, admiring the infamously simple graphics—which were mostly swaths of a single texture with plants or rocks drawn on them—or jump my character around to admire the way their armor moved. Once the game map had been completely explored, there were various tactics that players could use to get to unfinished or hidden areas, some of which were accessible only by a technique called “wall jumping,” wherein a player would jump directly at a wall for hours until they found an invisible hole that allowed them into the unpolished world beyond, making exploring in the game a literally endless endeavor.

Sometimes I took a rare break from the game to watch videos of other people playing. There were thousands of videos with millions of views, many of them produced by Chinese players; the most popular being of rogues engaging in PvP combat, displaying their ability to kill others with a single strike. The best videos didn’t show just PvP footage, but created entire story lines around their characters through graphic cutaways and text overlays (often in Chinese) that created a narrative of their character simply being a good person in a bad world, or being a hopeless romantic, et cetera, all of it tied together with a soundtrack of My Chemical Romance and Evanescence songs, and interspliced with footage of them effortlessly and viciously killing other players.

My computer became a kind of cathedral that I built and rebuilt over the years, constantly replacing the graphics card, memory, and CPU in order to see the game more clearly, to enter into the world as much as possible. I adjusted the user interface (the buttons and elements on the screen that control the character’s actions) almost daily, tinkering with it in an attempt to put as small a barrier between myself and the world on the screen.

But it wasn’t enough. It wasn’t enough to simply play the game or to optimize my computer. So during the summer of 2007, while I was deep into the game’s first expansion pack, The Burning Crusade, I started playing the game on drugs.

Up till that point I’d occasionally played after smoking weed and had tried to play on shrooms, before realizing that the high was too intense to play the game properly. But that summer, inspired by reading Erowid.com’s Experience Vaults forums, on which people recount their own drug usage in great detail, I started experimenting with taking minor amounts of the cold medicine Robitussin, which in larger doses apparently produces the strongest psychedelic experience one can have, due to the high levels of dextromethorphan it contains. On Erowid, people documented drinking so much Robitussin (“Robotripping,” as they called it) that they literally tripped themselves into other universes and were able to transcribe full conversations that they’d had with aliens. I never went that far, instead limiting myself to about five times the suggested dose, or about ten tablespoons, which I swallowed in between taking bites of a banana to try to stave off the revolting Robitussin taste. With my sensory sensitivity at a peak, I would wrap myself in a blanket and sit down in front of the computer in the evening, then play until dawn, when the luster of the drugs wore off with the rising run.

Robitussin was like a new computer, a graphics card in itself. On a mild dose it feels as though you’re always about to become high, as though you’re permanently “coming up.” But you never do, and instead remain in a constant state of mild highness that consists mostly of a euphoric body high coupled with vision that is both blurred and slightly enhanced, as though you’re looking at the world through tears. The new outer-space-jungle areas of the expansion pack were slurred, and swam lucidly on the screen. The acts of killing, interacting with another player, or even just walking through the atmosphere seemed like miracles. I played on drugs intermittently that whole summer, then stopped before the beginning of the school year. The only other time I played on any sort of drug was during the winter of 2008, while playing the Return of the Lich King expansion pack, when I sniffed raw peppermint leaves in order to keep myself awake longer, a method, I’d read, that Beethoven and Voltaire used.

After that winter, my playtime staggered, and by the end of 2009 I’d stopped playing completely. I tried to play again in 2014, but couldn’t justify spending my time questing in a game, as opposed to working in an increasingly gamified reality. When I think back on the game, I think of the World—of the rocky red terrain of Durotar, the rocky beige terrain of The Barrens, or the green jungle terrain (with trees) of Stranglethorn Vale—and the game’s humor. There’s just no real-life corollary to spending half your day trying to converse with a player in China, from whom you’ve just purchased in-game gold with real money; raiding a dungeon with forty other mentally ill people; or having a three-hour argument with a literal child on the in-game chat, all while sitting at your desk. Sometimes I’ll try watching a gameplay video, but I won’t be able to stand it for more than a couple of minutes, as I’ll find the changes made to the game —the endless amount of new areas, classes, and races, and the game’s vast oversimplification—genuinely depressing.

Patrick McGraw is the editor of Heavy Traffic .

October 18, 2023

Against Remembrance: On Louise Glück

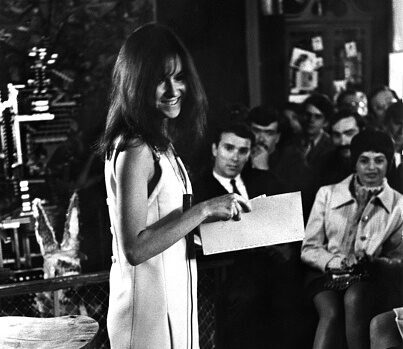

LOUISE GLUCK SMILES AS SHE READS HER WORK TO AN AUDIENCE IN THE HOME OF NORMAN MAILER, NEW YORK, NEW YORK, MAY 24, 1968. PHOTOGRAPH BY FRED W. MCDARRAH/MUUS COLLECTION, VIA GETTY IMAGES.)

Before I can think how to begin, she rebukes me: “Concerning death, one might observe / that those with authority to speak remain silent …” (“Bats,” A Village Life).

Flip the pages, to “Lament,” in Ararat, and once more, a reproof:

Suddenly, after you die, those friends

who never agreed about anything

agree about your character.

They’re like a houseful of singers rehearsing

the same score:

you were just, you were kind, you lived a fortunate life.

No harmony. No counterpoint. Except

they’re not performers;

real tears are shed.

Luckily, you’re dead; otherwise

you’d be overcome with revulsion.

Those two lines—a joke that hinges on being dead—make me smile. A reflex, as I am also crying. And I think, as I often have, that Louise Glück wasn’t given enough credit for being a funny poet. She is more commonly characterized as an investigator of death. Some find her poetry too skewed toward the grave; I wonder if we are too afraid of the fact that breath is the only thing keeping us out of it. To speak of her as if her death is the culmination of the work, though, is to ignore her attention to death’s vast and fecund opposite, rife with pleasure, with suffering, dominated by silence though it produces much speech in defiance: living, in the present continuous. To live is the verb it’s easy to forget you always embody. I stand. I walk around my bedroom. I worry the cuff of my gray wool sweater. I touch the petal of an Easter lily that opened just this morning. I remember that Louise prized completeness and detail when it came to natural things, so I walk back to my desk. On my laptop, I search the Latin name, Lilium longiflorum. I smile again: my futile attempt to draw closer to her becomes a joke that hinges on death.

Back to the book. My past self has drawn a line in blue ink beside this stanza: “Death cannot harm me / more than you have harmed me, / my beloved life” (“October,” Averno). Is there anything else to say?

***

My first conversation with Louise was a total failure. We both thought so.

You have to understand that I was in some essential way a feral creature, with that skittish hideaway instinct that comes from practicing survival. Though technically “homeschooled,” I was basically an autodidact: I’d spent years reading my way through the library. Since early childhood, my father had terrified and beaten me. When, a little older, I started to resist his control, he also deprived me of language, keeping me in my room for days without books. He read my journals and punished me for my thoughts. At nine, I’d started thinning myself compulsively. Then not just eating but talking became so difficult that I often could not answer direct questions. By twelve, I rarely spoke. My adolescence was silence, secret-keeping, desperate longing for a different future without the ability to imagine any future but death, which I expected would come to me young. You can see why I loved Louise’s poetry.

When she called me, I was eighteen, and had just been admitted to Yale, where she taught from 2004 until her death. I was at a gas station in Lancaster, Ohio, as far from poetry as anywhere could be. An unknown number, Cambridge area code. The admissions office, she said, had sent her the poems I’d submitted with my application and asked her to talk to me. Neither of us, fortunately, ever remembered exactly what was said, but my terror of talking, and talking to her, specifically, made me even less articulate than usual, and she, awkward in the face of awkwardness, faltered. “I thought you hated me,” she told me later. When I applied to her workshop at the beginning of my first semester of freshman year, I hoped she wouldn’t remember me. She did. I became her student.

She fascinated me. Her ability to extemporize in whole paragraphs. Her delphic certainty, a stated preference for the definite article, alongside an almost religious commitment to doubt, her sentences chained together by small temperings: “a kind of,” “as if,” “it may be that,” “I think,” “I believe.” And then—bang—a proclamation I’ll remember till I, too, no longer have memory. During office hours, I peeked at the labels of her clothes, which fell in luxurious folds of silk and wool and cotton and leather, black or gray or a dark green, and memorized the names of designers I looked up later. And I studied her mobile face while she read a poem: in those shifting expressions, a theater of perception and judgment before the lifted hand brought down the pen.

Sometimes, when she looked at me with a cool speculation or, other times, with a softness I named to myself as pity but did not resent because it seemed the gentle hand one experienced sufferer offers another, I felt as if I were watching her describe something to herself, the something being me, and sometimes she did describe me to myself, her clarity having some of the heartlessness of a real oracle: “You love your mother and hate your father, and you hate that your mother still loves your father.” The intensity of my desire to be seen matched the intensity of her seeing. She recognized my docility as a facade (obedience, never a quality she respected), and stoked the fire that burned it up. At least on the page, speech, choked by my father and then by myself, surged forth at her invitation—no, her urging—to speak.

“You have the makings of a real poet,” she told me that semester. Excited, as if she had made a rare discovery. I couldn’t meet her gaze; the idea overwhelmed me. But it took root in my mind and, shyly, slowly flowered into a dream and then a pursuit. She often thought in oppositions: “real” pointed to its negative, “false,” which was a betrayal of the art. (In the same way, she often described a poem or a line as “alive,” and though I do not remember her ever saying something was “dead,” I heard the unspoken problem.) “‘Poet,’” she wrote in an essay about her own education, “must be used cautiously; it names an aspiration, not an occupation. In other words: not a noun for a passport.” In her encouragement there was a warning, and a goad: You must do the making, Elisa, and the making goes on till you end.

She rejected many of my lines (“inert,” “hopelessly conventional”) but she never rejected my thoughts, no matter how cruel or deviant or strange. Often she anticipated the logic or the emotion, as if it were natural, at least comprehensible. In front of her, to her, for the first time in my life I could say anything.

***

The first time I read Louise’s poetry, I was twelve and sitting on a concrete berm at a gas station in northern Ohio. Nearby, my mother was making clouds of steam by pouring cup after plastic cup of water into the van’s radiator. My brothers and sisters played tag in a triangle of scrawny grass. Although my family didn’t often buy books (expensive), for some reason we’d recently visited a bookstore, where I chose The First Four Books of Poems (four-for-one appealed to my sense of value). I’d read poetry before, but it was this particular encounter with poetry, at dusk in high summer surrounded by the smell of gasoline, that remade me. Louise thought it funny—it is funny—that both of my introductions to her happened at Midwestern gas stations.

Her books, now piled beside me, encompass something like six decades of moods and situations. As a poet, she is both fixed and fluid. Change, I believe, was one of her deepest interests and drives. “As soon as I can place myself and describe myself—I want immediately to do the opposite thing,” she told an interviewer. Each book responds to some aspect of the previous. The distinctiveness of her lines—the powerful clarity of her thoughts—obscures, I think, that she is a master of personae, and it’s possible, at least from Ararat onward, to understand the books as both lyric and dramatic. The poems are made so subtly it’s easy to miss that subtlety, like grandeur, is one of her modes. The lines people often quote, such as the closing couplet of “Nostos”—“We look at the world once, in childhood. / The rest is memory.”—resound because of their daring assurance. But that conclusion requires the preemptive undermining of the previous lines: “Fields. Smell of the tall grass, new cut. / As one expects of a lyric poet.” (Again, she never gets enough credit for being funny.)

An abiding preoccupation, which compels the changes from poem to poem, voice to voice, book to book, is an anxiety about creation. Sometimes it emerges as an anxiety regarding form: finding a sufficient one, dealing with the consequences of fixing anything in words, which necessarily holds it still. Sometimes it is the fear, lurking or stated, that there will never be another poem. (“I’m talking too much,” she said to me recently. “But you’re our great poet of silence,” I teased her.) The greatest anxiety, however, concerns whether the thing created—the poem—will do justice to creation itself.

When I learned she had died, I was sitting on my bed, a red notebook in my lap. In that dazed rebellion that’s grief’s first incarnation, I wrote, You wrote my life, and then I corrected, You wrote all over my life, and then I corrected that correction: You wrote all through my life, and now I correct with a line I know I’ll correct again till I’m dead, too: You wrote me into my life.

“Sentimental,” I can hear her saying, with a grimace.

***

In the years since I met Louise as a person, not only as a poet, I’ve felt as if we were bound by an affinity that did not always emerge from the best parts of either of our souls. That we both casually use the word soul is one piece of that affinity. But there was also a sharpness, a darkness, an ironic eye turned on the self and the world—these tied us together as much as the appreciation of absurdity, the frustration with language, the fear of silence, the devotion to art, the passion for sensory experience and for passion itself, in its manifold forms. Manifold, a word that I associate with her, because its most perfect use may be in the first poem by her that I read, “The Drowned Children”—who are forever lifted in the pond’s “manifold dark arms.”

Louise had so many friends, so many students, and I suspect that many feel an analogous sense of affinity. Her perceptiveness made her, I think, unusually capable of forming intense connections. It could also (here, Louise, I offer a counterpoint, a harmony) make her unkindness especially devastating.

When I look back, I trace what feels like her love for me. She read. She listened. She critiqued. She encouraged. She nagged. Her faith in me exceeded my faith in myself. She supported me during a psychiatric hospitalization, and after my brother’s death. In turn I tried to love her, to understand her, to live, and to write.

After I heard she was sick, and before I heard she died, I copied down a passage from Camera Lucida, in which Roland Barthes rebels against the application of any category to his specific grief over the absence of his specific maman: “what I have lost is not a Figure (the Mother), but a being; and not a being, but a quality (a soul): not the indispensable, but the irreplaceable.” My first, flailing, childish thought when she told me that she was ill: I can’t do this without you. I still am not sure what I meant by this (poetry? life?) but I know what I meant by you. You, Louise, who would hate this whole thing.

I last saw her—how can “last” really mean “last”?—at the end of August, when I spent a few days visiting her in Vermont. For much of that time we talked as I drove her through a landscape of a solid green fortified by the wild rains that had flooded Montpelier, and spoiled her garden. In a labyrinthine antique store, we sat for a couple hours in a matched pair of damasked armchairs, discussing the history of our relationships with beauty (in people, in objects, in the world). In Plainfield, I inched the car forward slowly enough for her to point out every place of past significance, and outside the house where she wrote The Wild Iris, we talked about our terror of how love works on the lover, how pathetic it makes you. When I began the long drive back to New York, we were in the middle of many conversations, which we said we’d pick up soon, next time we saw each other, and the next time, when we would finish our conversations, then I would buy her dinner, for a change, a really excellent dinner, appropriate to her gourmand taste. As I write this, the intervening time disappears. We are sitting across from each other at a dining table. Sunset behind her, which means night is already behind me. The silence that follows a bout of laughter has settled on us. The wine she chose is almost gone. She asks, “Do you think anyone would expect us to laugh as much as we do?” And because I am again answering, I know that she was right, in “Lament,” to conclude that “this, this, is the meaning of / ‘a fortunate life’: it means / to exist in the present.”

Elisa Gonzalez is a poet, fiction writer, and essayist. Her debut collection of poetry is Grand Tour.

October 17, 2023

What Lies Beyond the Red Earth?

Carle Hessay, Image of the Hollow World, 1974. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons, licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

A few years ago, I read a lecture by Chinua Achebe given in 1975, later published as an essay entitled “An Image of Africa: Racism in Conrad’s Heart of Darkness.” While I greatly respect Achebe’s novels, his essays have often left me wanting. His voice reminded me of my grandfather’s, the intonations of a proud Nigerian man, rightly aggrieved at the dysfunctional state of his country, his continent, and its indefatigable life in the face of rampant, extractive exploitation by imperial powers. I feel that Achebe’s frustration can leave blind spots in his arguments, and the lecture in question—an outright denouncement of Conrad’s famed novel and its canonized status as “permanent literature”—was, I thought, an example of this. Achebe considered Conrad’s novel explicitly racist in its themes, in its depictions of the “natives,” and in the gaze of Marlow, Conrad’s primary protagonist, who Achebe believed wasn’t much removed from Conrad’s disposition.

Achebe questions the meaning of writing to our society, or the meaning of any art for that matter, when it can be so explicitly racist and go mostly unremarked upon by fans and critics alike, regardless of how beautiful the turns of phrase or evocative the depictions of the lush, sweltering alien landscape. I have a complex relationship with Conrad’s novel and agree with some of what Achebe put forth, but his argument felt incomplete. Achebe’s disgust is understandable, but I think one can see Conrad was also getting at a lack of vocabulary for this rich, intricate world, of atmospheres and new sensory and metaphysical experiences, at times in his prose defaulting to beautifully phrased but reductive tropes, which are still embedded in the unconscious of Western society today. As Achebe railed at Conrad’s reduction of complex cultures, knowledge systems, and languages, down to a dark, flat backdrop for Marlow’s descent into the pit of despair, and lamented Conrad’s objectification of West African bodies, I became hooked on an important and maybe even existential question—who was Achebe’s lamentation aimed at? Who was the primary audience for his words, written in English? And was there a moral authority to hear his appeal, and if so, what then?

I envision this moral authority: a shining round table, a collective ethereal body. I can picture where this body receives education, and what information and legacy bestow upon this body to uphold such cosmic authority. I peer at this body’s ancestral responsibility and how intricately woven its cultural history is with morality, technology, and progress—through religion, reason, language, war, and subsequent laws. I wonder, wouldn’t this same moral authority Achebe speaks to be the same that has canonized Conrad’s novel, lauding it as one Western literature’s great works?

Roughly around the time of Conrad’s birth, Anglican and Baptist missionaries from Britain began spreading the Christian word across Nigeria alongside armed colonial powers, and systemically implemented a proposed order and moral structure, offering bondage under the benevolent cloak of Christianity. They found innovative ways to suppress and diminish ancient local knowledge systems whilst leveraging the locals’ deeply inherent spiritual devotion. Tribal factions with differing religious and philosophical dispositions were difficult to control without the concerted imposition of particular moral principles through Christianity. Coordinating labor and governing over resource-rich lands was made easier by exploiting the tenets of local knowledge and sowing discord between tribes. Christianity has been significant to psychological governance, by imposing a moral condition and constraining culture, dissenting thought, or ways of seeing and being alien to the new “explorers” of this productive continent of vast cultural and environmental diversity.

Christianity existed in Africa before the arrival of missionaries. However, their spectral presence served a particular economic purpose, the legacy of which I witness today on the continent and across its diaspora. We can see this coercion and its resulting conservative legacy of docile communities as part of a colonial extraction strategy.

Many early contributions to foundational mathematics originated in Asia and Africa, and roughly a century before these missionary expeditions, the origins of European statistical mathematics and probabilistic methodologies were forming. These methods are now pivotal to computational methods like machine learning , vital to the pursuit of AI. Bayes’ Theorem, for example, a formula founded by the reverend and early statistician Thomas Bayes, is a significant driver of machine learning and originates in what appears to be shaky, metaphysical, and even monotheistic beginnings, as Justin Joque explains in his book Revolutionary Mathematics: Artificial Intelligence, Statistics and the Logic of Capitalism.

Bayes’ Theorem is a mathematical formula for determining conditional probability: the likelihood of an outcome occurring based on a previous outcome having occurred in similar circumstances. One might establish a belief, and later update said belief with newly acquired information supporting one’s argument or intention. Bayesian influence is significant to quantum mechanics (which is key to AI research and development) and its attempts to understand the physics of nature and the uncertainty of the universe.

As Joque says, the metaphysical origins of Western statistics have been well-documented by mathematicians and historians alike, many of whom have strongly resisted the Bayesian method, particularly in the twentieth century. Still, intriguingly, this method has recently resurged and is now very popular in algorithmic computing, developing “truths” (the outcome of this subjective method), principally for capital from numerous subjective origins (including social origins) that, over time, we have established for primarily economic purposes. This subjective Bayesian method—beginning with a guess or an assumption and adding data to solidify one’s guess or assumption—inevitably puts us in a slippery metaphysical dimension, not too dissimilar to where we might have been in years gone by, particularly in Europe, where society leaned on monotheistic reasoning to make sense of the world. Therefore, one might speculate that the logical endpoint of computation based on this statistical model, implemented by engineers and venture capitalists educated under a singular ontological framework, might aim at a convergent “truth,” whatever that may be, if we understand the (even unconscious) influence of monotheism on these protagonists implementing their dominant beliefs and morality, through the accumulation of vast amounts of information, with origins already hazy.

So then, a moral authority? If we use—and I consider this pronoun necessary here, for several reasons, as our involvement purports to be passive, but is not—algorithmic models to determine who has access to a loan or whether someone is guilty of a crime or not (to be then placed in for-profit prison systems), does morality, or a moral authority, as we understand it, ultimately serve only the acquisition, maintenance, and accumulation of capital? If so, then to who is the moral vanguard Achebe appeals to?

Achebe’s appeal, deep into the latter half of the twentieth century, is to an English-speaking, educated authority, of a dominant economic and educational system, with culture prominently in its service. Hundreds of years of Christian influence and legacy intersect with the Enlightenment’s emphasis on reason and individualism, which allies with violent methods of implementing extraction in distant lands in ways increasingly invisible to us as technology surges, all which combine to form today’s Western world, where race, class, and gender make for active feedback loops to further accumulate capital by manipulating datasets, which entrench and dictate our respective fates within this socially constructed economic system.

The same system of imbalances and inbuilt gaslighting narratives provide much of the patronage of art and culture. Patronage that attempts to uphold a moral center, guiding us to how we might exist alongside each other. “Culture” defines society’s artistic and intellectual refinements. We needn’t disregard the etymological origins of the word in this instance: of cultivating and tilling earth until it is fruitful and beneficial enough to sustain life. Or the biological meaning: an environment suitable for the growth of bacteria to spread indiscriminately. Culture maintains primacy for this economic system, affirming a dominant language and knowledge and suppressing other influences and dissent. Culture’s power and intentions are even crystalline in how few works of literature from across the world are translated into English until they’re deemed worthy of translation by an authority, the same authority, ultimately, that canonizes Conrad’s Heart of Darkness. I remain, for example, astounded by how many contemporary novels from the United States I read with a complete lack of a “nonwhite” person written into their pages as if none exist. An observation I make with some understanding of the history of segregation, yet, even so, when I imagine the scale of such autonomous formulations within society, it is enough to take one’s breath.