C.L. Francisco's Blog, page 3

June 22, 2017

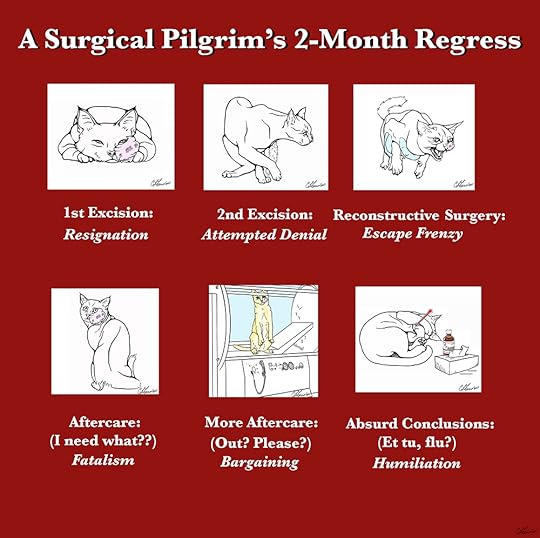

No posts for the last few weeks due to illness

May 18, 2017

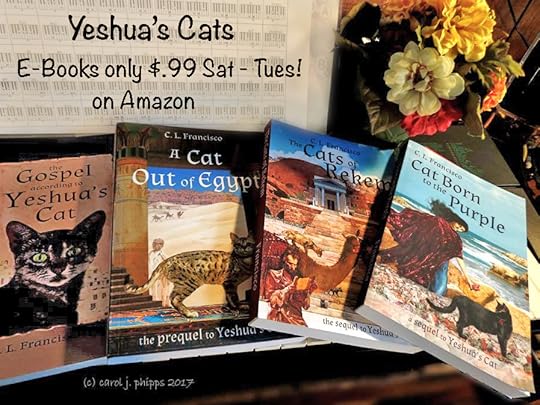

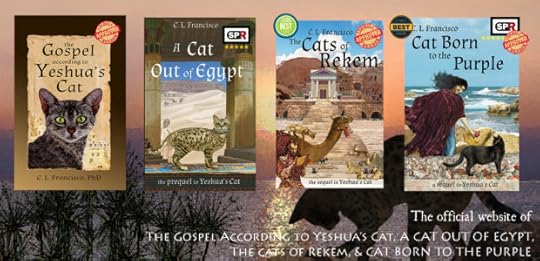

Thank you from Yeshua’s Cats!

Thank you all for making the Yeshua’s Cats Kindle sale such a success!

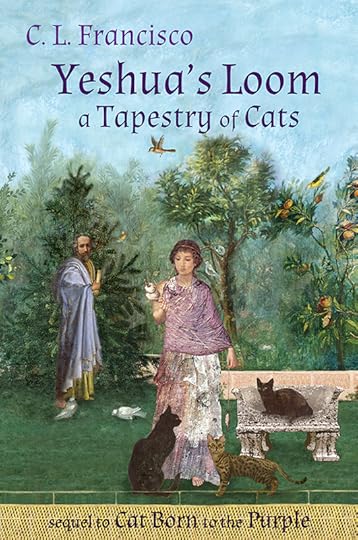

The new Yeshua’s Cats book,

working title Yeshua’s Loom: A Tapestry of Cats,

is scheduled for release this fall.

To read the prologue and 1st chapter, click here, or on the Yeshua’s Loom tab at the top of the page.

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

All Yeshua’s Cats E-books $.99 this weekend!

photo by C.J. Phipps

photo by C.J. PhippsSaturday, May 20th – Tuesday, May 24th

All Yeshua’s Cats E-Books on sale for only $.99

Buy your summer Kindle copies now!

[image error]

Starting at 8 AM EDT on Saturday, May 20,

ending at 8 AM EDT on Wednesday, May 25.

Save

Save

April 9, 2017

The Stones of Easter

“If the people were silent, the very stones would cry out.” Luke 19:40

The stones are speaking. Are we listening?

The memory of stone. People have spoken of it since humankind first wielded tools to chisel its surface. What stories might be locked in the smallest of river stones, the bedrock beneath the plains’ rich soil, the mountains crushed into gravel for our roads? Certainly we find there the record of the earth’s transformations, the bones and footprints of long-dead species, delicate traceries of plants, massive forests. But what about human lives? Have stones absorbed the fleeting touch of our lately-come species, the storms of blood, tears, laughter, prayer that accompany our kind wherever we wander? Do stones remember us?

Stones of Easter: Bread. Photo C.L. Francisco

Stones of Easter: Bread. Photo C.L. FranciscoI love stone. I have loved it from earliest childhood. I love the weight and feel of it in my hand, the warmth of it beneath me when I rest from walking, the magic of its kaleidoscopic patterns. When I can I travel to mountains and canyons and deserts to spend time in its company. Stone is alive, sentient in some way I can’t explain. I feel it most strongly in wilderness, where human busy-ness is limited—but it has also caught me unawares in urban alleys.

Stones of Easter: Wine. Photo by C. L. Francisco

Stones of Easter: Wine. Photo by C. L. FranciscoI am unlikely ever to hear a stone speak in human words, or a tree in propositions, or a dog in iambic pentameter. A stone communicates in the manner of stones, just as a dog communicates as dogs do. My experience of the speech of stones is deeply non-verbal, partly visceral and partly emotional, untranslatable. Sometimes I take a photograph or pick up a stone when I feel it; other times I simply let it be. The imagery comes later.

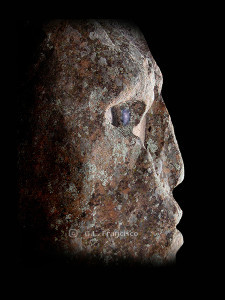

Stones of Easter: Flesh. Photo by C. L. Francisco

Stones of Easter: Flesh. Photo by C. L. FranciscoI am not a professional photographer, or even educated in photography. In the past I saw the images in a camera’s eye as an imagined canvas, in terms of shape and balance, tension and flow, light and dark. Now I find myself photographing scenes that pulse with the energy of subtle presence, and I let the rest take care of itself. Sometimes my pictures absorb a hint of that power, sometimes not.

Stones of Easter: Blood. Photo by C.L. Francisco

Stones of Easter: Blood. Photo by C.L. FranciscoWhat is a photograph? At its simplest it is a record of objects seen, events observed, people known. But like history, a photograph participates in the awareness of the one who watches and records. And like a scientific experiment, the photographer’s participation is a variable that must be considered. The same scene taken by different people with identical cameras at roughly the same time may be distinctly different—based on something I call “soul,” for lack of any better term. At times the camera’s eye appears to mediate an exchange of understanding? meaning? relationship? being? between photographer and subject, and this fleeting touch (or lack of it) marks the photo.

The Stones of Easter: Release. Photo by C.L. Francisco

The Stones of Easter: Release. Photo by C.L. FranciscoWhat are the stones saying with their images? I believe they are communicating their presence, no more. “Look at us!” they cry. “We are alive, in ways you have forgotten you ever knew. We are—as the trees are, and the waters, and the atmosphere that shields the Earth from the extremes of space. Truly see us—see all of creation—we who have been dismissed by your arrogance as mere commodities. See us, before only stones remain to see the sunrise.”

The Stones of Easter: Tomb. Photo by C.L. Francisco

The Stones of Easter: Tomb. Photo by C.L. FranciscoSlipping unseen along the fringes of consciousness, the temptation is always there—to “clean up” the images, make them perfect, adjust their proportions to fit more neatly into Western ideas of beauty. Sometimes I make changes without thinking, and then I have to destroy the image if I can’t undo the edits. We have an implicit understanding, the stones and I—that their images will remain as I find them, removed only from their matrix, and, at most, adjusted for contrast. After all, they are the language of stone, and much is inevitably lost in translation.

The Stones of Easter: Searching the Skies. Photo by C. L. Francisco

The Stones of Easter: Searching the Skies. Photo by C. L. FranciscoMany years ago I discovered a new word: panentheism. Not pantheism (many gods), not theism (usually one god separate from creation), but pan-en-theism—one Spirit present in all creation, without the great divide between spirit and flesh that seems unavoidable in most Western traditions. Perhaps this word can suggest a way to bridge the gulf between stones that speak and a planet of dead rock.

The Stones of Easter: Lament. Photo by C. L. Francisco

The Stones of Easter: Lament. Photo by C. L. FranciscoIn Christian scripture the apostle Paul describes the perceptions of ordinary people: “For now we see in a mirror, dimly . . . .” These words could describe any human being who has lost her sense of kinship with the web of life in which she lives. We see the world distorted in a bit of poorly polished metal—and ourselves more prominently than all else. But unlike Longfellow’s Lady of Shallot, we have no curse to excuse our stubborn avoidance of the Earth’s true face.

The Stones of Easter: Emergence. Photo by C. L. Francisco

The Stones of Easter: Emergence. Photo by C. L. FranciscoStone is patient. Stone does not envy or boast, and is neither arrogant nor rude. Stone simply is, demanding nothing. Stone is not false, but embodies the truth of creation. Stone accepts human abuse and awaits our healing. Stone endures all things, is always being transformed, yet is ever the same.

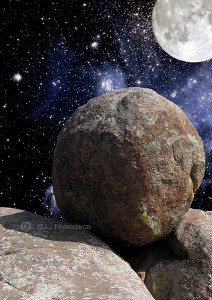

The Stones of Easter: Rolling Stone. Photo by C. L. Francisco

The Stones of Easter: Rolling Stone. Photo by C. L. FranciscoAll the photos in The Stones of Easter series* were taken on my brother Don’s mountain during Easter week, 2010, when I was deeply immersed in writing the final chapters of The Gospel According to Yeshua’s Cat. Starting on the morning of Maundy Thursday and ending on Easter Sunday, each day I packed a lunch and water flask and set off up the mountain with my camera. In a very literal sense, I went in search of a vision.

The Stones of Easter: Gone Away. Photo by C.L. Francisco

The Stones of Easter: Gone Away. Photo by C.L. FranciscoThe result of the vision that met me there is Yeshua’s Cat.

And, of course, one of Wendy’s cats.

.

* Sixteen photos in The Stones of Easter series are available for sale at http://www.zazzle.com/moon_seasons. The original series included 24.

This post was originally published in April, 2014.

.

Save

Save

Save

April 5, 2017

The Houses of Pompeii

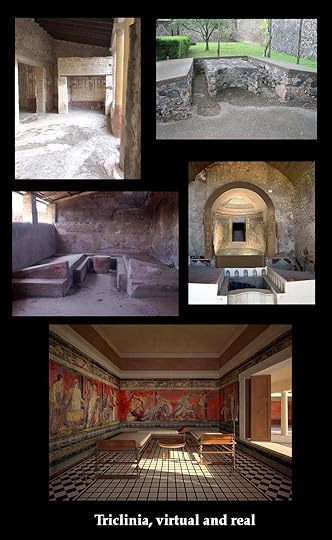

Ancient Vine virtual reconstruction of Roman triclinium

Ancient Vine virtual reconstruction of Roman tricliniumMy favorite thing about beginning a new book is all the new research required. It’s like being turned loose in an exotic new universe with an unlimited railpass–but, unfortunately, no maps. The internet can be as irritating as a poorly drawn subway map with half the lines left out or mislabeled, but once I stumble onto the right line, I hardly stop to eat or sleep! If I didn’t go half blind and start hitting dead ends and duplications I might never stop to write. I share T. H. White’s feelings about learning:

“The best thing for being sad,” replied Merlin, beginning to puff and blow, “is to learn something. That’s the only thing that never fails. You may grow old and trembling in your anatomies, you may lie awake at night listening to the disorder of your veins, you may miss your only love, you may see the world about you devastated by evil lunatics, or know your honour trampled in the sewers of baser minds. There is only one thing for it then — to learn. Learn why the world wags and what wags it. That is the only thing which the mind can never exhaust, never alienate, never be tortured by, never fear or distrust, and never dream of regretting.”

― T.H. White, The Once and Future King

Among the many things I’ve explored in my research for the 5th Yeshua’s Cats’ book, the details of Pompeii’s houses may be the most intriguing–perhaps because I knew absolutely nothing about Roman houses! So, on the chance that you may find the subject engaging too, I thought I’d do a post about them.

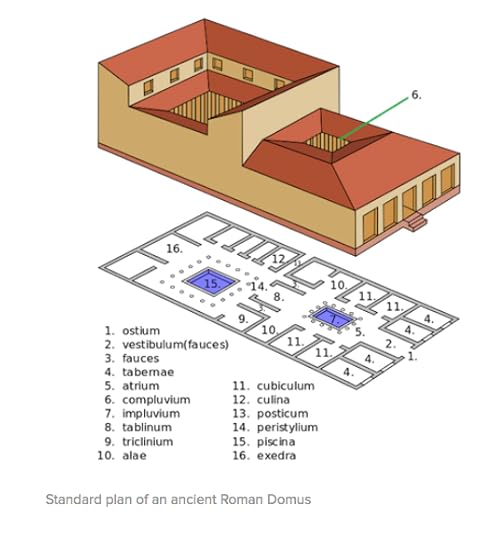

Here is the clearest plan I could find of the basic Roman house, or domus. Unfortunately, although it comes from Wikipedia, the original source is not given. A more detailed description of the separate rooms is available here.

The difference between an moderately wealthy city house and the seaside villas of the obscenely wealthy is clear from the plans below (Villa of Mysteries and moderate city house).

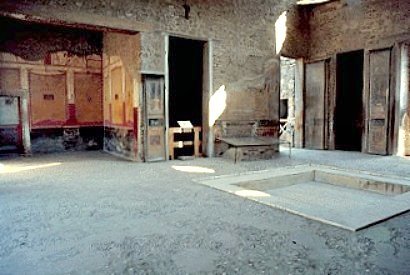

Most Roman houses–modest or palatial–were lined up on a visual axis from the main entrance, through the large public room, or atrium, and eventually out through the courtyard and garden. If you look at the house plan above, you can see this. The view below, of the House of Menander, is typical of a wealthy home. The photo was taken near the entrance, looking through the tablinum, toward the courtyard.

Most Roman houses–modest or palatial–were lined up on a visual axis from the main entrance, through the large public room, or atrium, and eventually out through the courtyard and garden. If you look at the house plan above, you can see this. The view below, of the House of Menander, is typical of a wealthy home. The photo was taken near the entrance, looking through the tablinum, toward the courtyard.

Apart from ventilation, this axis seems intended to give visitors the most impressive view possible of a home when they first entered. After all, status and wealth made the Roman world go round. In the words of the mosaic in the entryway of the merchant’s house below, SALVE LVCRVM, “Welcome (hail) profit!”

Apart from ventilation, this axis seems intended to give visitors the most impressive view possible of a home when they first entered. After all, status and wealth made the Roman world go round. In the words of the mosaic in the entryway of the merchant’s house below, SALVE LVCRVM, “Welcome (hail) profit!”

If you refer to the house plan above you can follow me as I explore the layout, with examples of the different types of rooms found in Pompeii. BTW, most photos, if not labeled otherwise, came from an amazingly helpful site on Pompeii, https://sites.google.com/site/ad79eruption/pompeii/

Entryway

Even the wealthiest homes in Pompeii opened directly onto the street and shared walls with the houses on each side–unless the owners were wealthy enough to own the entire city block (insula). A back entrance for servants and tradespeople usually opened off a narrow corridor on the side or rear. The street front of the Menander House (above) was slightly set back from the sidewalk by a raised bench, possibly for people to sit upon while waiting to see the master of the house. The metal gate is positioned where the wooden door stood.

Once inside the house, the visitor finds herself in an entry hall called the fauces, #2 on the plan. The fauces below leads into the House of the Ceii. Like almost all the houses in Pompeii, the walls were frescoed in fairly standard styles. Archaeologists now classify early Roman wall paintings as Pompeiian styles 1-4. The style below is #4. If you look at the plan, you can see that the fauces runs between shops that open onto the street.

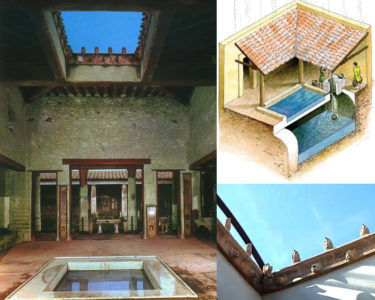

Atrium

At the inner end of the narrow fauces the visitor emerges into the large main room, or atrium. Most atria had openings in the center ceiling to let in light and collect water for the cisterns, which were buried in the floor. The opening in the ceiling was called the compluvium. The pool that collected the water below and drained it into the cisterns was the impluvium. You can see both clearly in the photo below from the House of the Lararium. Also below is a cut-away diagram showing the location of the cistern, and a closeup of rain spouts from the House of Casca Longus.

From the look of the modern photo below by Roger Ulrich, the atrium isn’t an ideal place to sit on a rainy day! I assume that the rain spouts and guttering in the diagram following would have prevented such drenching rain-spatter.

From the look of the modern photo below by Roger Ulrich, the atrium isn’t an ideal place to sit on a rainy day! I assume that the rain spouts and guttering in the diagram following would have prevented such drenching rain-spatter.

The atrium was the main public room of the house, and opened onto a room called the tablinum, where the master of the house did business and kept accounts. The tablinum was at least partially open on both the front and back sides to allow for airflow, light, and a clear view into the colonnade and garden. Draperies provided privacy when necessary. Below is Lund University’s virtual image of the tablinum (right) in the House of the Ceii, with the typical hallway or andron on the side (left). An identical andron ran along each side of the tablinum.

The atrium was the main public room of the house, and opened onto a room called the tablinum, where the master of the house did business and kept accounts. The tablinum was at least partially open on both the front and back sides to allow for airflow, light, and a clear view into the colonnade and garden. Draperies provided privacy when necessary. Below is Lund University’s virtual image of the tablinum (right) in the House of the Ceii, with the typical hallway or andron on the side (left). An identical andron ran along each side of the tablinum.

Often in Pompeii the rooms directly on the street were rented out to businesses, or used as shopfronts by the family living in the house. If they were rented shops, there was no access to the house itself. As shown on the house plan, these rooms were called tabernae. They could be rented apartments, living quarters for family servants, storerooms, or shops. As shops,they were often thermopolia, or cafes (below), where hot and cold food was served from deep dishes set into marble counters. Businesses like bakeries and laundries usually occupied whole buildings. Craftsmen used such rooms for selling their own goods, while using the house behind as their home and shop.

Atria sometimes had an open alcove to one side, perhaps where guests might be seated, called an ala, (#10 in the domus plan above). The photo of the atrium in the House of the Vetti (below) shows an ala on the left. The entrance is to the right.

Atria sometimes had an open alcove to one side, perhaps where guests might be seated, called an ala, (#10 in the domus plan above). The photo of the atrium in the House of the Vetti (below) shows an ala on the left. The entrance is to the right.

Atria also commonly housed household shrines (lararia) as well as elaborate strongboxes intended to demonstrate the family’s wealth. (below)

Virtual altar by Ancient Vine

Virtual altar by Ancient VineCubiculae

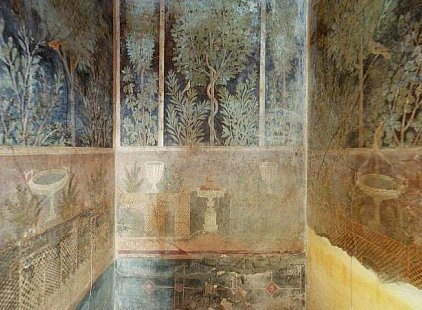

The small closed rooms called cubiculae on each side of the atrium are bedrooms, either for guests or family. The House of the Orchards had two bedrooms lavished painted with gardens (below). Bedrooms were also located upstairs, and sometimes opened off the courtyards.

Bedrooms rarely had windows. For that matter, neither did the rest of the rooms in the house. Except for rare windows in rooms facing into the peristyle, the only windows in Pompeiian houses tended to be tiny and set high up on the walls. The exception to this rule were in very wealthy homes on the coast itself, where windows with sea views might be found in any room of the house.

Windows into peristyle in House of the Prince of Naples

Windows into peristyle in House of the Prince of NaplesOf all the cultural differences between ancient Roman houses and modern American ones, the thing that surprised me most was the placement of family bedrooms around the main room in the house–the one most frequently visited by strangers. Although this arrangement was the result of older housing patterns built around a courtyard as a common living space, nothing else quite communicated to me the vast difference between “personal space” or privacy as I understand it and the ancient Roman one.

Here is a virtual reconstruction of a bedroom from the House of the Tragic Poet:

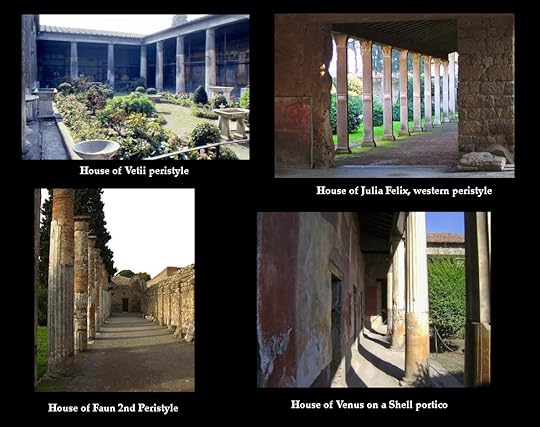

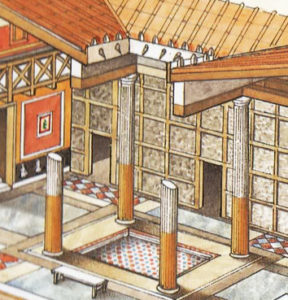

Peristyle

Immediately past the atrium and the tablinum with their adjoining rooms, was the courtyard, or peristyle, a colonnaded garden space with rooms around its side. Larger, wealthier homes often had more than one courtyard, as well as a large open garden. The rooms around the peristyle were usually used for dining and entertaining: the triclinia, or dining chambers, and the excedra, or banqueting room. Wealthy homes often had several triclinia. The kitchen (culina, #12), latrines, and baths (in very wealthy homes) were in this back area as well. Oddly enough, the latrines were often located in a corner of the kitchen, perhaps because of the easy access to water.

Villa of Mysteries virtual image copyright © 2011, James Stanton-Abbott, Stanton-Abbott Associates

Villa of Mysteries virtual image copyright © 2011, James Stanton-Abbott, Stanton-Abbott Associates

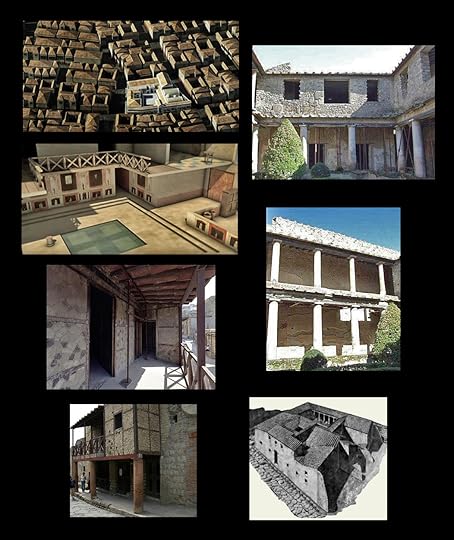

Upper Floors, Fountains, Paintings, and Mosaics

Because most of the upper floors of Pompeii’s houses were destroyed, piecing together a lifestyle that includes them has been difficult. A few still stand, and virtual reconstructions have been attempted:

The multiple stories of some cliff-side villas withstood the eruption better– for instance, the House of the Relief of Telephus at Herculaneum:

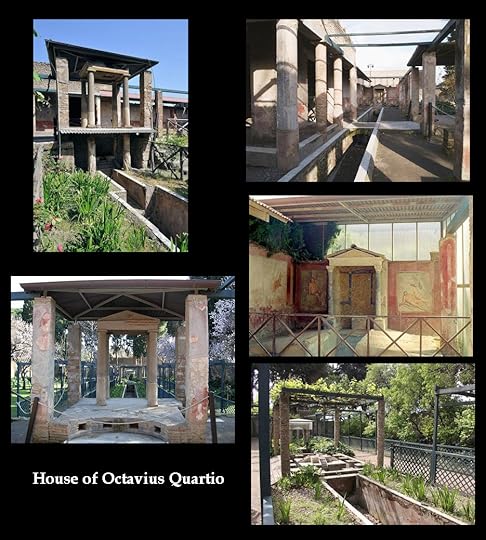

The larger mansions often had multiple pools and fountains in the peristyles and gardens. One house in particular, the House of Octavius Quartio, has an extravagant series of fountains and canals. The House of the Large Fountain has a particularly fine fountain (below).

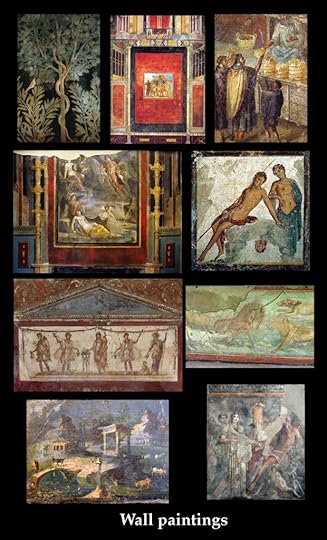

Below is a selection of Pompeiian wall paintings and mosaics. I hope you’ve enjoyed your tour!

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

March 25, 2017

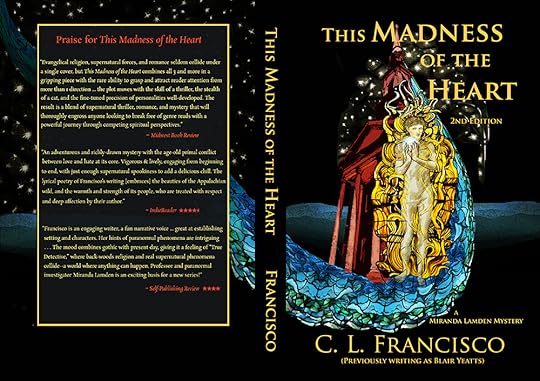

This Madness of the Heart April Fool Sale!

April Fools’ weekend! “This Madness of the Heart”

e-book only $.99 on Amazon!

Starting at 8 AM EDT on Friday, March 31st,

get the ebook edition of This Madness of the Heart for only $.99

(down from the regular price of $5.99)!

Sale ends at 8 AM EDT, April 2nd. Don’t miss out!

Save

March 1, 2017

This Madness of the Heart out in paperback!

“This Madness of the Heart” out in paperback!

The paperback 2nd edition of Madness is now available in the CreateSpace Store, and on Amazon! The Kindle format is also live on Amazon.

Here are some of the reviews coming in:

Midwest Book Review, Diane Donovan, Editor and Senior Reviewer

“Evangelical religion, supernatural forces, and romance seldom collide under a single cover, but This Madness of the Heart combines all three and more in a gripping piece that holds the rare ability to grasp and attract reader attention from more than one direction . . . Mood and setting are exquisitely placed throughout the story . . . the plot moves deftly with the skill of a thriller, the stealth of a cat, and the fine-tuned precision of personalities well developed.

“The result is a blend of supernatural thriller, romance, and mystery that will thoroughly engross anyone looking to break free of genre reads with a powerful journey through competing spiritual perspectives.”

IndieReader Review: 4 1/2 stars

“An adventurous and richly drawn mystery, with the age-old primal conflict between love and hate at its core. Vigorous and lively, engaging from beginning to end, the lyrical poetry of Francisco’s writing carries just enough supernatural spookiness to add a delicious chill!

While Jarboe fits many of the nastiest stereotypes of the fundamentalist preacher, others – particularly his retired predecessor, Elmus Rooksby – show themselves as models of warmth, generous love, and human kindness.

Can Professor Miranda Lamden untangle the threads of a crime involving an old family curse, a secret religious fellowship, a business partnership gone sour, and family relationships embittered at their roots before it’s too late?”

Self Publishing Review:

“Francisco is an engaging writer, a fun narrative voice . . . great at establishing setting and individual characters. The hints of paranormal phenomena are intriguing throughout . . . The mood combines gothic with the present day, giving it a feeling of “True Detective” (first season), in which backwoods religion and real supernatural phenomena collide – a world where anything can happen. Professor and paranormal investigator Miranda Lamden is an exciting basis for a series . . . the rock through it all.”

Kathleen Eagle, New York Times Bestselling author of Sunrise Song:

“This Madness of the Heart is a wild ride through the dark hills of eastern Kentucky with Miranda Lamden, a professor of religion who spends her spare time studying arcane spiritual rituals–if not participating in them herself. Francisco fields an engaging cast of characters, and throughout she weaves a compelling pattern spun of the Appalachian wilderness and its people. The plot twists kept me guessing, all the way to the very satisfying ending. Fans of Joyce Carol Oates and Nevada Barr should relish this new series, and I look forward to more–the sooner the better!”

Nancy McKenzie, award-winning author of Queen of Camelot:

“Kudos to C. L. Francisco for an absorbing read and an original thriller, with intriguing characters and hair-raising plot twists (protagonist Miranda Lamden is solid gold)! This Madness of the Heart explores the genesis of hate and the power of forgiveness in a small college town in eastern Kentucky’s hill-country, where a haunting spirituality–both Christian and pagan–drives this fast-flowing mystery to an electrifying close. But beware: pick it up and you won’t be able to put it down again—I couldn’t!”

Gail Godwin, author of Evenings at Five:

“Blair Yeatts can certainly write!”

.

Jane Reads Blogspot:

“This Madness of the Heart is amazing . . . I haven’t read such a good gothic mystery in ages! I was intrigued from the beginning, and hooked from the first chapter. Even though there are many twists and turns in the plot, each time, I thought, “I did not see that coming!”

“I highly recommend This Madness of the Heart to all fans of gothic mystery and suspense—and particularly to fans of Barbara Michaels and Sharyn McCrumb.

“Five out of five stars!” (kitties)

Save

Save

February 11, 2017

Miranda Lamden’s Mysteries and Yeshua’s Cats Together!

I’ve been thinking a lot about how This Madness of the Heart (and all the following Miranda Lamden Mysteries) fit together with my Yeshua’s Cats series–and why I feel certain the two series can coexist as books by the same author. But since my reasons are more feelings and instincts than logic, I’ve had trouble putting them into words.

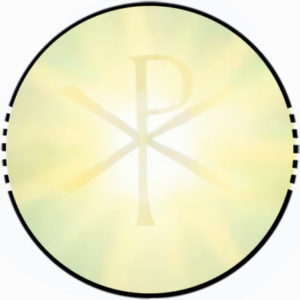

So I did what I often do when I need to make sense of something: I created a piece of art (below). After all, what good is an art therapy degree if you can’t use it to clarify your own confusion? If I’m lucky, by explaining the image I’ll be opening up what lies behind it!

The Sleuth, Chi Rho, and the Cat

The Sleuth, Chi Rho, and the CatSo, what are you looking at here?

First, I chose a Hubble image for the background: “Interacting Spiral Galaxies” . . . surely ideal for this project, since galaxies don’t often interact–anymore than churchfolk and professor-sleuths! It felt like a propitious beginning.

Hubble, Interacting Spiral Galaxies

Hubble, Interacting Spiral GalaxiesThree interlocking circles fill the foreground. The center circle pulses with a glowing gold and green light; the Christian Chi Rho emerges from its heart.

What is the Chi Rho? Like most symbols, it has different meanings across cultures, but for me it’s a symbol used by early Christians in the first three centuries after Yeshua’s birth–before Constantine transformed it into an imperial banner (the cross didn’t emerge as a Christian symbol until after the year 500).

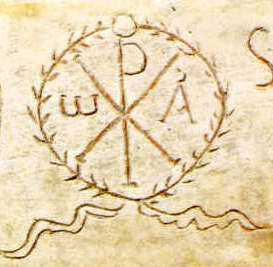

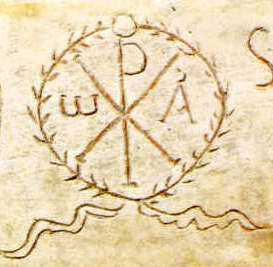

Chi Rho, early 3rd C catacomb

Chi Rho, early 3rd C catacombThe Chi Rho gets its name from the two Greek letters that overlap to create the symbol: Chi and Rho, the first two letters of the Greek word Christos, or Christ. In the image above, the Greek letters Alpha and Omega are added. I did experiment with using a cross in the center circle, but I like the visual effect of the Chi Rho better, probably because it has “rays” like the sunburst. Anyway, the central circle is meant to be the Christian faith–not the organized religion–but the living faith of all the individuals who hold themselves to be Christian.

The circle to the right is Mari, from Yeshua’s Cat, turning aside from a path in a green forest to investigate the central circle. In her circle she represents all of the natural universe. Creation. Everything that exists naturally, apart from the intervention of humankind. This natural order also includes human beings, since they’re part of the created universe–but not their civilizations.

The totality of the created world–as we know it on Earth–is flowing back from Mari’s search like the tail of a comet.

The circle on the left is where Miranda, my detective, lives. Her circle is the world of human civilization–urban, complex, multi-cultural, and often unsure exactly what they believe. Many, like Miranda, have their roots in Christianity, but have turned away from the church. Spinning out from her circle is a spiral of different world religions. But in her circle she, like Mari, has paused to examine something about the Christian faith that has caught her eye.

Both Mari and Miranda live outside the Christian fold, and they approach it from opposite directions. Mari moves from the non-human, natural environment, Miranda from a detached, urban, academic world. Still, both find themselves intrigued by the light in the center circle. Mari has the easier approach: Yeshua introduces himself by saving her life, and she joins him as a friend. But Miranda has been scarred by her Christian experience; she mistrusts the church and its agendas. As a professor, she sees all religions as examples of the human yearning toward the divine. Truth claims don’t enter the picture. She simply records what she observes, without making judgments. Her methods are catlike: she steps cautiously toward anything new, not committing herself, poised to slip back into the shadows if conflict threatens.

I knew a number of women like Miranda in my years apart from the church. Their worlds were full and rich, but they didn’t screen their experiences through a Christian worldview. Yet they were sometimes attracted by a light shining out from this tradition many of them had left behind.

. . . maybe the light shone through a person

a man like Elmus

or as comfort in the midst of evil

perhaps through the One’s presence in some crisis of their own

or simply in prayer and meditation.

But today we live in a world where it’s increasingly difficult to say, “I believe.” The language is lost. What does it mean to believe? Who are we believing in? People who live in the secular world can’t respond to most Christian overtures–because they don’t understand the words anymore. God-talk is becoming literal non-sense to those outside the churches.

People like Miranda are who they are, just as cats are cats. Each responds to life according to their gifts . . . but for some reason those inside and outside the churches are drawing further apart.

Perhaps we might learn from the effort, and love, we put into cross-species communication with our cats (and dogs, gerbils, birds, and ferrets) . . . and look at the incomprehensible human beings around us as if they concealed inner selves as delightful, unique, and full of surprises as a cat’s. It’s not really such a stretch.

I happen to find the lives of alienated Christians intriguing, perhaps because I’ve been there myself. And if the polls are right, their numbers are growing. Their honesty is often fierce, like their determination never to be taken in again by faux-Christianity and self-serving lies. Sadly we don’t have to look far to find the lurking predators they’re avoiding. And that’s what This Madness of the Heart is about.

Miranda peers into the light of Christian faith–but she looks from a place apart. Her own experiences haven’t shown Christianity to be that promised “light to the gentiles.” So she watches, examines, records, and considers. In the meantime, I feel privileged to narrate her journey.

Click here to visit my Miranda Lamden Mysteries site.

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Miranda Lamden’s Mysteries and Yeshua’s Cats

I’ve been thinking a lot about how This Madness of the Heart (and all the following Miranda Lamden Mysteries) fit together with my Yeshua’s Cats series–and why I feel certain the two series can coexist as books by the same author. But since my reasons are more feelings and instincts than logic, I’ve had trouble putting them into words.

So I did what I often do when I need to make sense of something: I created a piece of art (below). After all, what good is an art therapy degree if you can’t use it to clarify your own confusion? If I’m lucky, by explaining the image I’ll be opening up what lies behind it!

The Sleuth, Chi Rho, and the Cat

The Sleuth, Chi Rho, and the CatSo, what are you looking at here?

First, I chose a Hubble image for the background: “Interacting Spiral Galaxies” . . . surely ideal for this project, since galaxies don’t often interact–anymore than Christians and professor-sleuths! It felt like a propitious beginning.

Hubble, Interacting Spiral Galaxies

Hubble, Interacting Spiral GalaxiesThree interlocking circles fill the foreground. The center circle pulses with a glowing gold and green light; the Christian Chi Rho emerges from its heart.

What is the Chi Rho? Like most symbols, it has different meanings across cultures, but for me it’s a symbol used by early Christians in the first three centuries after Yeshua’s birth–before Constantine transformed it into an imperial banner (the cross didn’t emerge as a Christian symbol until after the year 500).

Chi Rho, early 3rd C catacomb

Chi Rho, early 3rd C catacombThe Chi Rho gets its name from the two Greek letters that overlap to create the symbol: Chi and Rho, the first two letters of the Greek word Christos, or Christ. In the image above, the Greek letters Alpha and Omega are added. I did experiment with using a cross in the center circle, but I like the visual effect of the Chi Rho better, probably because it has “rays” like the sunburst. Anyway, the central circle is meant to be the Christian faith–not the organized religion–but the living faith of all the individuals who hold themselves to be Christian.

The circle to the right is Mari, from Yeshua’s Cat, turning aside from a path in a green forest to investigate the central circle. In her circle she represents all of the natural universe. Creation. Everything that exists naturally, apart from the intervention of humankind. This natural order also includes human beings, since they’re part of the created universe–but not their civilizations.

The totality of the created world–as we know it on Earth–is flowing back from Mari’s search like the tail of a comet.

The circle on the left is where Miranda, my detective, lives. Her circle is the world of human civilization–urban, complex, multi-cultural, and often unsure exactly what they believe. Many, like Miranda, have their roots in Christianity, but have turned away from the church. Spinning out from her circle is a spiral of different world religions. But in her circle she, like Mari, has paused to examine something about the Christian faith that has caught her eye.

Both Mari and Miranda live outside the Christian fold, and they approach it from opposite directions. Mari moves from the non-human, natural environment, Miranda from a detached, urban, academic world. Still, both find themselves intrigued by the light in the center circle. Mari has the easier approach: Yeshua introduces himself by saving her life, and she joins him as a friend. But Miranda has been scarred by her Christian experience; she mistrusts the church and its agendas. As a professor, she sees all religions as examples of the human yearning toward the divine. Truth claims don’t enter the picture. She simply records what she observes, without making judgments. Her methods are catlike: she steps cautiously toward anything new, not committing herself, poised to slip back into the shadows if conflict threatens.

I knew a number of women like Miranda in my years apart from the church. Their worlds were full and rich, but they didn’t screen their experiences through a Christian worldview. Yet they were sometimes attracted by a light shining out from this tradition many of them had left behind.

. . . maybe the light shone through a person

a man like Elmus

or as comfort in the midst of evil

perhaps through the One’s presence in some crisis of their own

or simply in prayer and meditation.

But today we live in a world where it’s increasingly difficult to say, “I believe.” The language is lost. What does it mean to believe? Who are we believing in? Secular humans can’t respond to most Christian overtures–because they don’t understand the words anymore. God-talk is becoming literal non-sense to those outside the churches.

People who live in the secular world are who they are, just as cats are cats. Each responds to life according to their gifts . . . but for some reason those inside and outside the churches are drawing further apart.

Perhaps we might learn from the effort, and love, we put into cross-species communication with our cats (and dogs, gerbils, birds, and ferrets) . . . and look at the incomprehensible human beings around us as if they concealed inner selves as delightful, unique, and full of surprises as a cat’s. It’s not really such a stretch.

I happen to find the lives of alienated Christians intriguing, perhaps because I’ve been there myself. And if the polls are right, their numbers are growing. Their honesty is often fierce, like their determination never to be taken in again by faux-Christianity and self-serving lies. Sadly we don’t have to look far to find the lurking predators they’re avoiding. And that’s what This Madness of the Heart is about.

So Miranda peers into the light of Christian faith–but she looks from a place apart. Her own experiences haven’t shown Christianity to be that promised “light to the gentiles.” So she watches, examines, records, and experiences. In the meantime, I feel privileged to narrate her journey.

Click here to visit my Miranda Lamden Mysteries site.

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

January 21, 2017

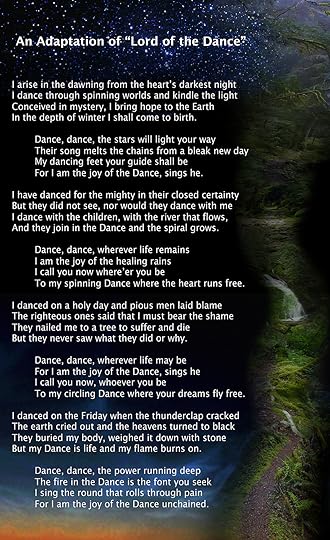

“Lord of the Dance”

I’ve loved this song most of my adult life, but always wanted it to say more, somehow. So I eventually wrote my own adaptation, below. It follows the original tune of “Simple Gifts,” with its erratic rhythm (the beats of the verses should be 13-11-11-11, and the refrains 8-10-8-10)