C.L. Francisco's Blog, page 10

March 14, 2014

Belief, doubt, and cats in cradles

February 28, 2014

Avinoam Danin and Plants of the Bible Lands

.

.

“We botanists consider the new plants we describe as new-born children and love them all. I have now 42 such plants and it is hard to say whom I love more.” (1)

– Avinoam Danin

Satureja nabateorum, new species discovered near Petra by Avinoam Danin

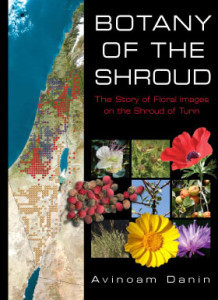

If you’ve read The Gospel According to Yeshua’s Cat, you may have wondered where I found the inspiration for Yeshua’s parable of the caper flower, or the sycamore fig tree. The answer? Eminent botanist Dr. Avinoam Danin, most recently in the public eye with his book, Botany of the Shroud: The Story of Floral Images on the Shroud of Turin.  For much of the time when I was writing Yeshua’s Cat, I was living in isolated rural environments, with no access to academic libraries. When it came to biblical history and texts, this wasn’t a problem. My own knowledge and personal library were adequate. But I found that I wanted more details: what wild plants were native to Galilee? Judea? the Decapolis? Which of them might have provided food for hungry travelers? What trees were native to the different regions? How big were they, and what did they look like? In what seasons did they bear fruit? Have plant species mentioned in the Bible been identified? Might any have inspired parables that never reached us through the gospels? You get the idea.

For much of the time when I was writing Yeshua’s Cat, I was living in isolated rural environments, with no access to academic libraries. When it came to biblical history and texts, this wasn’t a problem. My own knowledge and personal library were adequate. But I found that I wanted more details: what wild plants were native to Galilee? Judea? the Decapolis? Which of them might have provided food for hungry travelers? What trees were native to the different regions? How big were they, and what did they look like? In what seasons did they bear fruit? Have plant species mentioned in the Bible been identified? Might any have inspired parables that never reached us through the gospels? You get the idea.

So, like many writers before me, I turned to the internet, beginning my project with search terms like “indigenous plants of Israel.” It didn’t take long before I identified a site on the Hebrew University server as a gold mine: Flora of Israel Online, moderated by Professor Emeritus Avinoam Danin. Not being a botanist, I found navigating around the site to be quite a challenge at first: if I didn’t come armed with a specific plant’s Latin name, I got nowhere. But once I located a Latin list of Israel’s plants on a less tantalizing website, I was on my way. Each plant on Professor Danin’s site was documented with a wealth of photographs and data.

Tabor Oak, E. Strawberry, Date Palm, Olive, Carob. All photos Flora of Israel Online, Hebrew University

But that was only the beginning. One day I stumbled onto a different section of the site, sometimes called “Plant Stories,” sometimes “The Vegetation of Israel and Neighboring Countries.” Here Dr. Danin allows himself to speak more informally, using personal and cultural anecdotes to enrich his discussion of a huge variety of plants and habitats. From what I could tell, there are few wild places in Israel or its surrounding neighbors that he hasn’t explored.

And hidden among the plant stories was “The Story of the Caper”:

I liked the “tales of the caper” in the Mishnah. Raban Gamliel stated that “There will be trees that will provide fruits daily.” His pupil said “But it is written that there is nothing new under the sun”; Raban Gamliel said “Come and I’ll show you that they already exist in our world – they went out and he showed him a caper. . . (2)

Well, I was hooked, but it only got better–he went on to describe the caper blossom’s transformation through the dusk and night-time, which I used as the basis for Yeshua’s parable told to the young philosopher of the Decapolis (YC, p. 163).

Caper blossoms, all photos Flora of Israel Online, Hebrew University

Interspersed throughout the article I found more reminiscences of his own experience with the caper plant, including his personal practice of pickling and canning hand-picked capers as gifts.

Pickled buds, fruits, leaves and stems of the Capparis zoharyi, photo Avinoam Danin, Flora of Israel Online

Most of his plant stories never found their way into Yeshua’s Cat, although Yeshua’s makeshift meals of kanari berries and locust pods (YC, p. 83) I credit to him, as well as Yeshua’s examples of common knowledge: “If you feast on bitter almonds, will you not die? Where date palms grow, will you not find water?” (YC, p, 172). It still grieves me that I wasn’t able to use his explanation of how to recognize ancient cisterns in order to find water in the desert. Perhaps in the next book.

Ancient Har Nafka Cistern, photo Avinoam Danin, Flora of Israel Online

I suppose this whole blog entry is simply my way of saying thank you to Dr. Danin for being the kind of scholar who is driven by love of his discipline to share what he knows in appealing and accessible ways, so that everyone–not just other specialists in his field–can appreciate it. Whether he will be pleased to find his name mentioned in the context of an imaginative Christian biography of Jesus of Nazareth, I can’t say. But I suspect he is always delighted when his love of Israel’s native plants is shared with new audiences.

Want to read more about Avinoam Danin? Here’s an interview published in 2012.

.

.

February 26, 2014

Win a free copy of Yeshua’s Cat!

Kristi’s Book Nook is offering a free copy of Yeshua’s Cat to some lucky winner! Check out her website for details, but hurry–sign-ups close on March 4th!

Kristi’s Book Nook is offering a free copy of Yeshua’s Cat to some lucky winner! Check out her website for details, but hurry–sign-ups close on March 4th!

.

February 14, 2014

Sleeping with Bacchus: cats and stress

.

Moving: nobody likes it. It’s unsettling, disorienting, chaotic. Every stress scale includes it. If you live within a tight budget it’s also appallingly hard work. And the older you get, the greater the possibilities of personal disaster. The specters of back injury and clinical exhaustion pile onto the routine risks of things broken or left behind, toes smashed, muscles strained, and near-death experiences driving top-heavy, tank-like vehicles. And I speak from a continent of experience.

Moving: nobody likes it. It’s unsettling, disorienting, chaotic. Every stress scale includes it. If you live within a tight budget it’s also appallingly hard work. And the older you get, the greater the possibilities of personal disaster. The specters of back injury and clinical exhaustion pile onto the routine risks of things broken or left behind, toes smashed, muscles strained, and near-death experiences driving top-heavy, tank-like vehicles. And I speak from a continent of experience.

When humans move, we understand why we do it, although it’s never easy, and seldom without pain. But what about the animals who share our lives, who go because we go? No, let’s be more specific: what about our cats?

Morgan

We had finally been forced to leave our fire-scarred land for a new home, and the year was turning toward the 2nd anniversary of my cat Morgan’s death, which had resulted from the stress of our original flight from the wildfire. And that meant I was also approaching the 2nd anniversary of my mother’s death (she died a week after Morgan).

Trauma makes tracks in our memories, links among synapses like connections in a railroad switching yard: a mental switch is thrown, direction changes imperceptibly, and we find ourselves traveling a road wearing the smooth semblance of the here and now, but invisibly cracked and pitted with old emotion. The unseen past trips us with its rubbled pain and creates new trauma where none need be: a trick of the mind, and one that caught me off-guard.

I had adopted a pair of kittens from a local shelter not long after Morgan’s death. From his earliest days, the male, Bacchus, had a sweetness I’d rarely encountered in a cat before, and I loved him beyond reason. When we moved to Colorado, he developed a urinary infection in the first weeks. I watched him closely, and began to see symptoms like Morgan’s appearing. When he strained to urinate for over a minute with no success I packed him into his carrying case and took him to the vet. Probably stress-related from the move, the vet said, and my heart quaked.

Bacchus

Stress. We talk about it all the time. Most of us are sure we have too much of it. We assume we understand what it is, but the word can mean at least four different things:

in physics, force per unit area;

in language, emphasis on a word;

in psychology, emotional discomfort produced by external and/or internal circumstances;

in biology, a stimulus that generates a state of heightened physiological response, and the physiological and anatomical consequences of that response.

The familiar buzzword is #3. Most people are aware of #2, some are superficially familiar with #1 from news reports on structural collapses after earthquakes, but I doubt that many people without biological or medical training are aware of #4.

The vets I consulted about Morgan and Bacchus almost certainly spoke in biological terms—but what I heard was pop psychology. I went away believing that the emotional terrors of moving were direct causes of both infections. We were speaking subtly different languages.

Photo by Hannibal Poenaru

There are two basic scenarios for biological stress: the perceived threat can be real, or it can be imagined. If the threat in the stimulus is real, then running away or fighting will relieve the stress, and the body can return to normal. But when the threat is imagined, the situation is more complex. If, as in Bacchus’ case, a cat perceives a threat in a new environment, but neither fight nor flight is possible, his body is unable to relax from the heightened response, and the stress is prolonged and unresolved. So he remains in a state of inappropriate physiological alert to the stimulus of this new environment for days and weeks. Such stress has an exhausting effect over time.

There are two basic scenarios for biological stress: the perceived threat can be real, or it can be imagined. If the threat in the stimulus is real, then running away or fighting will relieve the stress, and the body can return to normal. But when the threat is imagined, the situation is more complex. If, as in Bacchus’ case, a cat perceives a threat in a new environment, but neither fight nor flight is possible, his body is unable to relax from the heightened response, and the stress is prolonged and unresolved. So he remains in a state of inappropriate physiological alert to the stimulus of this new environment for days and weeks. Such stress has an exhausting effect over time.

Apparently, Bacchus’ response to feeling lousy from the extended time on high alert was to stop drinking water. An unfortunate choice, since he then started building up uric acid in his system, which caused bladder inflammation and pain, making him think he needed to urinate when he didn’t—with the result that he felt worse and even less inclined to drink anything, and became dehydrated.

Morgan-Bacchus collage

By the time I packed Bacchus into his carrying case, my emotional train had already switched tracks without my awareness: I was sure I was rushing to save his life, but in fact I was caught up in a replay of the trauma of the wildfire and Morgan’s illness and death. Judgment and clear-sightedness had fallen away. As for Bacchus, taking him to the vet was probably the worst thing I could have done. Already suffering from the effects of physiological stress because of our move, he found himself suddenly moved again, but this time abandoned in a strange vet’s kennel, with neither his human nor his sister for comfort. Suddenly his life had gotten much worse.

Bacchus stayed overnight at the clinic, but by midmorning the next day he had produced no urine sample, so the vet used a needle to draw urine from his bladder. It hurt, and Bacchus vomited. Concerned that shock was a possibility, the vet hydrated him, analyzed the urine, and sent him back home with some antibiotics. At 2 AM Bacchus began to stagger and vomit. He was going into shock.

Shock is a sudden and drastic drop in blood pressure that is usually fatal if not reversed quickly. It is commonly caused by an extreme reaction to threatening stimuli, great blood loss, or pain—any of which will have greater impact if the animal is already dehydrated. Immediate intravenous fluids are the only effective treatment for a cat in shock, so I rushed Bacchus to an emergency clinic twenty miles away. He barely made it, but they saved his life.

If I had responded to Bacchus’ symptoms with a little thought and research instead of recycled panic, I could have taken special care to be sure he drank enough water and watched him closely for a couple of days. Perhaps he never had an infection—just inflammation. By taking him to the vet, I subjected him to greatly increased stress and dehydration, and when the vet drew urine, Bacchus was frightened by the pain. I might as well have been setting him up to go into shock.

[image error].

February 1, 2014

Painted Gospels

In the days before Yeshua’s Cat was written, before the wildfire scorched our land, I was exploring the changes that had carried humanity forward in time from the old Earth-based cultures of the Stone Age, through the violent upheavals of the late Bronze Age, and into the time of the Roman Empire. The planned lectures and workshops vanished in the wildfire’s smoke, but something else emerged. I realized that without the art of these ancient peoples we would understand almost nothing about them. So where was the art of the early church? How had my education in early Christian history managed to focus so entirely on words? As a result, I turned to the internet and the local university library and began to search for the visual language of the early Church. (In case you’d like to explore on your own, Picturing the Bible by Jeffrey Spier is a good place to start.)

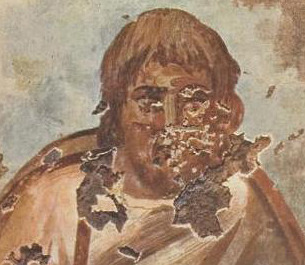

Painted bust of Jesus, Nunziatella Catacombs

For much of the mid-20th century, common wisdom dismissed the “search for the historical Jesus” as a groundless hope, a fantasy for the unrealistic. But although we may never see a portrait of the flesh and blood man Jesus, the search has proved far from “groundless”: in our time the Earth herself has been yielding up the voices and visions of Jesus’ earliest followers with increasing frequency.

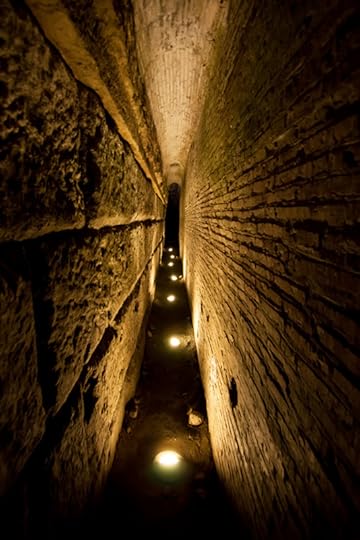

1st C walls under San Clemente, photo Marc Aurel

Anyone who visits Rome today steps into a buzzing archaeological hive. This in itself isn’t so strange; after all, many of Rome’s greatest attractions were literally unearthed from its ancient past. What fascinates me is how these ruins emerge. They aren’t turned up by a farmer’s plow, or weathered out of an eroding riverbank, but excavated from beneath the city’s basements. Apparently, Rome buried itself. And the same can be said of Jerusalem, or almost any other Mediterranean capital.* In Rome, for example, the twelfth-century Basilica of San Clemente that still stands today used the walls of the fourth-century San Clemente as foundations. This earlier church rose on top of a first-century mansion. Stairs of ever-increasing age, exposed in recent excavations, descend from the sunlit world down through the virtually intact fourth-century church and into the bowels of ancient Rome. There visitors can walk along a first-century Roman alleyway and explore a now-subterranean apartment building adjacent to the walls of the mansion used as an early Christian meeting place. And under it all lies the rubble of Rome’s great fire of 64 CE.

Santa Maria Antigua, Rome

Canyons carved into the human past are literally opening at our feet along the Roman streets. We can almost believe we hear the slap of sandaled feet two thousand years dead. Anything seems possible. The past walks with us in ways we never imagined. Beneath the many strata of Roman civilization lies tuff, or hardened volcanic ash. Tuff is relatively soft until exposed to air, and is ideal for tunneling. This Roman bedrock made possible the creation of the lowest levels of all Roman ruins, the catacombs. As long as sufficient structural support was left in place, there was almost no limit to the number and extent of these labyrinthine burial chambers.

Catacombs of St. Callisto

Although the most famous are Christian, catacombs existed before the early church period, and provided burial space well into the Common Era for those of many different religions. Their painted burial chambers offer us some of the earliest glimpses into the faith of Christian believers, perhaps even back to the middle of the first century.

Vatican Necropolis, 3rd C. CE

Visual art as a way of communicating our experience of the world is always personal, and far more powerful than words. Art strikes human depths directly. When a person chooses images to express the soul’s deepest yearnings in the face of death, non-essentials fall away. The heart chooses whatever makes life livable, hope possible. When we look at funerary art, we meet human beings as they turn their faces toward the mystery of life moving into death. This mystery is what we find in the catacombs.

Jesus raising Lazarus, Via Latina catacombs

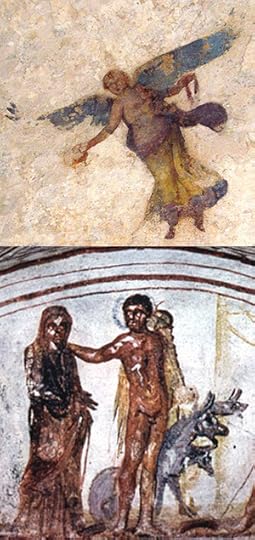

Winged Victory and Hercules

So why are these earliest of Christian testimonies so little known? Why have these painted gospels made so little impact on how Christians understand their faith today? Perhaps it is because our own worldviews get in the way. So an American tourist in Rome snaps a photo of Nike (Winged Victory), and calls her a Christian angel. Another sees a faded catacomb painting of Hercules with the three-headed dog Cerberus and identifies him as the Good Shepherd (with peculiar sheep). We see what we expect to see, squeezing everything into familiar molds. Or perhaps most people just haven’t had the chance yet to truly experience these painted gospels for themselves.

Early Christians chose dramatic images of Jesus and the Old Testament when they painted their tombs. Those appearing most frequently in the 3rd century and earlier are below:

.

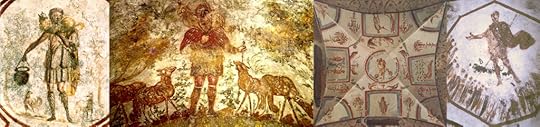

Jesus the Good Shepherd, who cared unceasingly for his flock:

Early catacomb images of the Good Shepherd

Jesus the miracle-worker, who healed the sick, raised the dead, and controlled the elements:

Early catacomb images of Jesus performing miracles

Jesus the wise teacher:

Early catacomb images of Jesus teaching

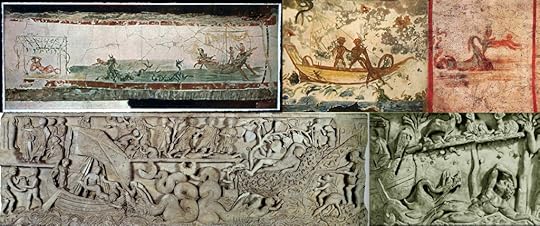

Jonah’s sojourn in and emergence from the fish’s belly:

Early catacomb images and tomb carvings of Jonah

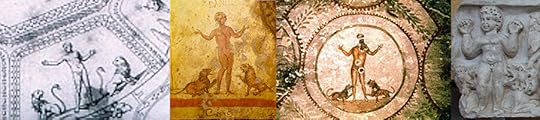

Daniel’s deliverance from the lions:

Early catacomb images of Daniel in lion’s den

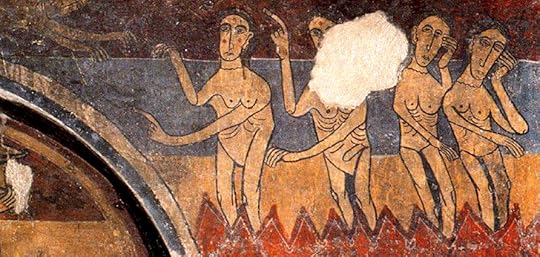

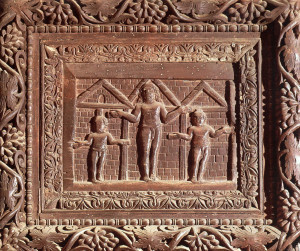

The three young men protected from the fiery furnace:

Early catacomb images of three men in fiery furnace

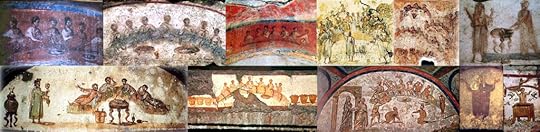

Early Christians also painted images of themselves on tomb walls, using two motifs more often than others: women and men with arms raised in prayer and praise; and small groups of Christians gathered around shared ritual meals.

Early catacomb images of Christians gathered together

The paintings in the house church at Dura Europos in Syria (dating from about 230-250 CE) are the only Christian images of similar age that have been discovered. The paintings there depict the good shepherd, Jesus’ miracles, the Samaritan woman at the well, and the women at the tomb, as well as Old Testament scenes. Also like the catacombs, they portrayed contemporary believers in positions of praise (orants).

No crucifixes, no suffering martyrs, no images of sacrifice appeared in the early years. These came at least 500 years later, with the developing doctrines of the church.

But what does all this have to do with people like us, living two thousand years later? What impact might it have? Let me paint you a picture with words.

Jesus, Nunziatella catacomb

The Christian faith whispering from the dark walls of the catacombs shows us a young man of their own culture–robed, beardless, often holding a wand in his hand–reaching out with compassion and power to touch and heal the human pain around him. He stops the flow of menstrual blood that has made a woman ritually unclean for years. He commands death to release the dead Lazarus, and death yields to him. He sits as a teacher in a circle of disciples, speaking words of life. A strong man with bare legs, he stands among a flock of sheep, carrying a lamb across his shoulders. He betrays no weariness or impatience, only watchful care.

The faith pictured here is in a loving, powerful, and wise man sent from God to point the way and guide his people. They relied on his healing power, his love, and his commitment to their well-being. His God-given power was stronger than death, stronger than the destructive powers of nature, and stronger than human malice.

Early catacomb image of women serving a meal

The believers in these painted gospels were neither theologically complex nor concerned with church structure. Women appeared in positions of leadership as often as did men. No canon of scripture had yet been established, although Paul’s letters were circulating among believers by the 50’s–when there were already growing Christian communities in Rome. Church hierarchy was only a spreading shadow on the horizon, and authority was fluid. What we now consider to be the four gospels were written between 70 and 100 CE, and did not become authoritative until much later. Communities of Christians followed their own personal experience and oral traditions, and suffered at the whim of Roman emperors.

By the third and fourth centuries, the increasingly hierarchical church forcibly silenced dissenting voices. Orthodoxy narrowed to a fine line. A few men concentrated all the power in their own hands. Congregations became sheep in ways they had never anticipated in the early years, and their shepherds were not always good. Too often fear, shame, and guilt discouraged the sheep from straying. Bloody sacrifice–Jesus’ own, and that of the martyrs–became a cornerstone of church doctrine where it had never been before. Bishops formulated creeds, damning those who did not confess Jesus in precisely their words–along with all followers of other faiths. The groundwork was laid for the Crusades and the Inquisition.

The Pains of Hell, 1100 CE

Like the Romans buried Rome, the church buried itself. But unlike Rome, what the church buried they rarely considered fit to use for new foundations. Whether these developments, and those that have followed in the centuries since, have anything at all to do with the message of Jesus of Nazareth is a question more and more people are asking today. In the end each of us may need to dig through the rubble of time and consciousness to find our own buried treasure. But one thing seems clear: the treasure is there. Perhaps our perceptions are at fault.

.

.

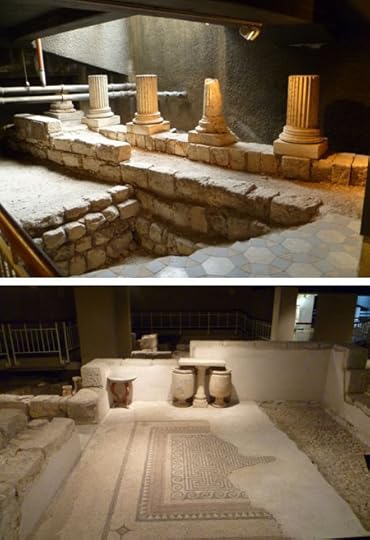

Wealthy Jerusalem home of the Herodian period

* The Wohl Museum of Archaeology in Jerusalem has excavated similar subterranean houses of the Herodian period from the hillside overlooking the Temple Mount. Although currently the museum has no website of its own, many pictures of their discoveries are available online . . . .

.

.

January 16, 2014

The Wildfire that Birthed Yeshua’s Cat

A number of people have asked me to share more about the wildfire that resulted in the death of the young cat whose memory lies behind Mari in The Gospel According to Yeshua’s Cat. This is the story of that wildfire.

Killing drought followed years of plentiful rainfall. Temperatures spiked into the 100’s and refused to drop. Creeks ran low. The odor of pine resin hung heavy in the air. A dry lightning strike—and a rancher who didn’t take it seriously enough—provided the critical mass, and two weeks later wildfire had consumed 40,000 acres of forest, pastures, and homes.

We dismissed the first smoke rising behind the buttes as nothing more than a wayward cloud, never imagining that the storm building there would explode into a holocaust. The days that followed dragged by in anxious succession. Winds dropped, and then blew up again out of nowhere. The fire turned back on itself, only to gather strength and roar off in another direction. Waves of rumor obliterated facts.

We dismissed the first smoke rising behind the buttes as nothing more than a wayward cloud, never imagining that the storm building there would explode into a holocaust. The days that followed dragged by in anxious succession. Winds dropped, and then blew up again out of nowhere. The fire turned back on itself, only to gather strength and roar off in another direction. Waves of rumor obliterated facts.

One night we drove out to watch the fire’s progress from a nearby ridge. News pictures of fire-lit nightscapes are commonplace now, but for us 8 years ago the scene was nothing less than apocalyptic. Small refugee animals fleeing the fire choked the dirt roads as we steered a path among them. I remember the porcupines best, humping their way in unseemly haste through the sullen light. Lines of flame spreading across the black ridges looked like flowing lava. The images presented themselves to our visual processors as nonsense, unreadable data. Nothing in our lives had prepared us for this.

First we evacuated the horses, just in case. We found carriers for the dogs and cats and set them by the doors. When the call came, we were as ready as we could have been, but we had room for little but the animals, basic clothing, toiletries, and our computers. Then for a week of endless days we waited in a small motel on a busy highway 30 miles away.

First we evacuated the horses, just in case. We found carriers for the dogs and cats and set them by the doors. When the call came, we were as ready as we could have been, but we had room for little but the animals, basic clothing, toiletries, and our computers. Then for a week of endless days we waited in a small motel on a busy highway 30 miles away.

Why our home didn’t burn will always remain a mystery. The firefighters abandoned their efforts in the face of high winds and encircling fire. We were advised to expect a total loss. But in the end, the flames stopped as if by divine fiat all along the wire pasture fences that enclosed our buildings. Sap melted out of the old redwood paneling in my house from the heat, but only the land burned—the land and something deep in the flesh of my small black cat.

Why our home didn’t burn will always remain a mystery. The firefighters abandoned their efforts in the face of high winds and encircling fire. We were advised to expect a total loss. But in the end, the flames stopped as if by divine fiat all along the wire pasture fences that enclosed our buildings. Sap melted out of the old redwood paneling in my house from the heat, but only the land burned—the land and something deep in the flesh of my small black cat.

Morgan, cat of quiet pine groves that she was, probably hadn’t ever been in any building other than my house, and certainly never a motel on a busy highway. For a week she hardly came out from under the bed. No matter what I tried, she refused to eat, and she probably didn’t drink. By the time we returned to the still-smoldering ruins of our forest, she had a urinary infection. No medication touched it, and she grew steadily weaker, until at last the vet tested her for feline leukemia. The results were positive: she’d probably been born with it. All options vanished. The vet’s theory, and a sound one from what I’ve heard, was that the physical stress of her changed environment roused the sleeping disease into burning life. She might have stood a better chance if I’d left her behind to survive the wildfire on her own.

Within two months of the fire, Morgan was dead. I buried her in the charred grove where we had planned to build a small chapel. Beneath boughs once sweet with resin, in smoke-filled light and brittle shade, I laid her under the endless sky. And I grieved.

Morgan in her last week with friend Toby (Photoshop design, “Doorway Into Forever”)

But the grief had really begun when the vet first placed the figurative black cloth on his head and passed sentence of death. A dead forest surrounded me. My gentle cat was fading away in my arms. Eventually I gathered courage and resumed my walks beneath beloved trees, now wasted skeletons streaked with amber tears.

.

I remember shutting my heart against the echoes of pain that surely must lie in ambush along those charcoaled aisles. But as weeks passed, only woodland stillness reigned. Blowing ash darkened the sun—smoke without fire, forest lives airborne—but already the forest’s heart was turning to the east. Life was emerging from death.

Blasted meadows were greening. Tenacious pines, seared but stubborn, drank deep to gather strength for life. Fire-crimsoned cones dropped seed. Seedlings broke the fragile soil. *

I found comfort in the cycle of life, and even in death.

.

Somehow over the next five years, Morgan’s death, questions about the Creator’s on-going involvement in non-human nature, the timing of Jesus’ coming in human history, and the redemption of the suffering Earth—all came together into the creation of Yeshua’s Cat. The spiritual doubts that had plagued my heart for years ripened and bore sweet fruit.

.

.

I’ll continue the story of this journey in a few weeks. Come back soon!

.

.

* To read about the devastating effects of salvage logging on the recovery of burned forests, click here.

.

January 3, 2014

The Decapolis

.

What exactly was the Decapolis? It was mentioned twice in Mark’s gospel and once in Matthew’s, but described only as a region near Galilee where Jesus’ fame spread. In The Gospel According to Yeshua’s Cat, Yeshua and Mari spend considerable time in the Decapolis among the Greco-Roman peoples there.

Decapolis meant literally “ten cities” in Greek, and referred to a loosely knit group of ancient cities in what is now Israel, Jordan, and Syria. No one can say for sure which cities were included in the ten–or even if there were exactly ten–since their relationship was never formalized in Greek or Roman law. As best we know, they were independent cities, each established as a polis, or city-state, with its own local sphere of influence. They supported each other because of their common ties of culture, similar economic interests, and commitment to the Greek, and later, Roman, empires. With the construction of Roman roads they became even more closely interconnected: outposts of the Roman Empire on its furthest eastern edges, islands of Greco-Roman speech and culture, determinedly set apart from the Aramaean, Nabataean, and Jewish populations all around them.

The Decapolis

The red dots on the map above mark the eight cities closest to Galilee that were probably included in the Decapolis in the early 1st C. CE. The cities connected by red lines are the ones Yeshua visited in The Gospel According to Yeshua’s Cat, although (except for Scythopolis) they aren’t identified by name in the book. In the paragraphs below, cities where specific events in Yeshua’s Cat took place are identified by small cat silhouettes:

Antiochus Epiphanes

Greek influence in Syria was strongest between the time of Alexander the Great and the reign of the Seleucid emperor Antiochus IV Epiphanes, whose rule ended a century before the Roman conquest in 63 BCE. Most of the Decapolis cities were founded during this period.

When Antiochus Epiphanes desecrated the Temple and forbade the observance of the Jewish religion, Israel revolted, led by Mattathias the

Judas Maccabeus, Acre Synagogue, photo Dr. Avishai Teicher

Hasmonean and his five sons, later known as the Maccabees. They overwhelmed the Seleucids and forced them to concede Israel’s limited independence, thus founding the Hasmonaean dynasty, which ruled in Israel until after the Roman conquest. Once the Greeks were defeated in Israel, the Hasmonaeans turned their eyes to the walled cities of Trans-Jordan, and conquered most of the Decapolis by the beginning of the 1st C BCE.

Ancient Roman statue of Pompey the Great

After annexing the Decapolis, the Hasmonaeans forced Judaism and circumcision on the predominantly gentile population of Hippos, exiled the gentiles from Scythopolis, and burned Pella to the ground after it refused to accept the Jewish religion. Circumcision was a point of irreconcilable conflict between Greeks and Jews. For the Jews it was the essential mark of the male believer in the One God; for Greeks it was a desecration of the divinely formed human body.

Hard feelings between the people of Israel and the Decapolis during the time of Jesus had roots both in the Seleucid oppression of Israel and the years of warfare under the Hasmonaeans. Each side had known cruelty and suffering. When Pompey claimed the Decapolis for Rome in 63 BCE, the gentile population greeted him as a liberator, and killed many Jewish residents in revenge for Hasmonaean cruelty. Once the Romans established themselves in the Decapolis, a period of extensive rebuilding began, lasting into the 2nd and 3rd centuries CE. As a result, little remains of the original Greek cities.

Hippos looking west across Sea of Galilee

HIPPOS sat on a high ridge overlooking the eastern side of Sea of Galilee, surrounded on all sides by steep inclines and high fortifications. One thin shoulder of rock approached the main gate on the east, where a fortified road connected the city to the eastern hills as well as indirectly to the sea. Of all the Decapolis cities, Hippos is said to have harbored the greatest antagonism toward Israel for her part in the Hasmonaean wars.

As you read of the blind man Yeshua healed outside the gates of the first Decapolis city he visited, you can imagine that long ridge by which travelers still approach the gates of Hippos.

As you read of the blind man Yeshua healed outside the gates of the first Decapolis city he visited, you can imagine that long ridge by which travelers still approach the gates of Hippos.

View of the eastern approach to Hippos

GADARA, like Hippos, was built on a long ridge with steeply sloping sides. Unlike the other Decapolis cities, Gadara developed an international reputation for philosophy, art, and literature. Pilgrims to the hot springs located below the city also contributed to its cosmopolitan atmosphere. Some scholars believe that the story of the demoniac among the tombs was set in its general locale.

GADARA, like Hippos, was built on a long ridge with steeply sloping sides. Unlike the other Decapolis cities, Gadara developed an international reputation for philosophy, art, and literature. Pilgrims to the hot springs located below the city also contributed to its cosmopolitan atmosphere. Some scholars believe that the story of the demoniac among the tombs was set in its general locale.

Yeshua’s debate with the young philosopher took place in a wealthy home in Gadara.

Yeshua’s debate with the young philosopher took place in a wealthy home in Gadara.

Gadara’s theatre, photo by Berthold Werner

Abila, photo by APAAME

ABILA is still little more than an excavation in process, with only tantalizing possibilities visible to the visitor. But the area awaiting excavation is immense. The ruins extend across two tells, and appear to include structures going back as far as 4000 BCE.

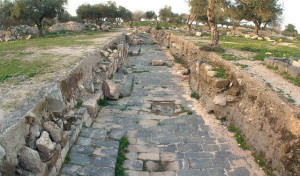

Gerasa Cardo, photo by Bgabel

GERASA, or JARASH, was a strong walled city, but stood in a river valley rather than on a hill. Most of the surviving structures date back to a massive Roman building program begun in the 1st C CE. The Cardo, or main thoroughfare, is one of oldest structures, running east-west through the city, with the marketplace on its west side.

GERASA, or JARASH, was a strong walled city, but stood in a river valley rather than on a hill. Most of the surviving structures date back to a massive Roman building program begun in the 1st C CE. The Cardo, or main thoroughfare, is one of oldest structures, running east-west through the city, with the marketplace on its west side.

Below are the remains of the market, or macellum, where Yeshua’s parable of the prodigal son brought a tide of change to the people of the Decapolis. This was also the market where Mari trapped Maryam into speaking with Yeshua.

Below are the remains of the market, or macellum, where Yeshua’s parable of the prodigal son brought a tide of change to the people of the Decapolis. This was also the market where Mari trapped Maryam into speaking with Yeshua.

The Macellum at Jarash, photo by APAAME

PELLA, of all the ancient cities of the Decapolis, has left the greatest mystery behind. Almost no ruins from the Roman period have survived. Located in the hills on the east side of the Jordan Valley, on a major Roman road, Pella lay in an area with fertile soil and plentiful water, where towns had stood almost continuously from Neolithic times. After Alexander Jannaeus sacked and leveled the city in 82 BCE, it was entirely rebuilt by the Romans. Archaeologists have suggested that after the great earthquake of 526, the inhabitants of Pella might have recycled the rubble of Roman buildings to rebuild the city.

Site of ancient Pella looking toward the Jordan River

SCYTHOPOLIS, or BEIT SHE’AN, is the only one of the Decapolis cities located on the western side of the Sea of Galilee. These ruins have been extensively excavated, revealing almost continuous occupation from the earliest times, although the city’s significance fluctuated with intermittent wars and violent conquest. The Seleucids founded Scythopolis in the 3rd C BCE on the ruins of the ancient city of Beit She’an, destroyed during the Assyrian sack of Israel. During the Hasmonaean wars much of the Greek polis was destroyed. Once the Romans took over, Scythopolis was named the capital of the Decapolis, and a massive urban building program began, which continued through the next 2-300 years. The steep hill, or tell, which rises to the north of today’s excavated Roman city, covers the remains of the biblical Beit She’an, as well as Seleucid and early Roman ruins. Most of the monumental Roman buildings were completed during the 2nd and 3rd centuries CE on the flat land to the south and east of the tell, leaving little evidence of the city’s appearance during the time of Jesus, although the main layout of the streets may have been similar.

SCYTHOPOLIS, or BEIT SHE’AN, is the only one of the Decapolis cities located on the western side of the Sea of Galilee. These ruins have been extensively excavated, revealing almost continuous occupation from the earliest times, although the city’s significance fluctuated with intermittent wars and violent conquest. The Seleucids founded Scythopolis in the 3rd C BCE on the ruins of the ancient city of Beit She’an, destroyed during the Assyrian sack of Israel. During the Hasmonaean wars much of the Greek polis was destroyed. Once the Romans took over, Scythopolis was named the capital of the Decapolis, and a massive urban building program began, which continued through the next 2-300 years. The steep hill, or tell, which rises to the north of today’s excavated Roman city, covers the remains of the biblical Beit She’an, as well as Seleucid and early Roman ruins. Most of the monumental Roman buildings were completed during the 2nd and 3rd centuries CE on the flat land to the south and east of the tell, leaving little evidence of the city’s appearance during the time of Jesus, although the main layout of the streets may have been similar.

Scythopolis Roman ruins with tell behind

Temples were built on the tell at various times during Greek and Roman occupation, perhaps partly because of Scythopolis’ fame as a major center for the worship of Dionysos. Legends of the time located the tomb of his nurse Nysa at Scythopolis.

Because of the city’s connection to the Greco-Roman dying and rising agricultural god, in Yeshua’s Cat the procession of Tammuz’ devotees witnessed by Mari, Yeshua, and the disciples took place in Scythopolis. The tell was the hill the mourning women climbed by torchlight.

Because of the city’s connection to the Greco-Roman dying and rising agricultural god, in Yeshua’s Cat the procession of Tammuz’ devotees witnessed by Mari, Yeshua, and the disciples took place in Scythopolis. The tell was the hill the mourning women climbed by torchlight.

Excavations on the tell at Beit She’an

December 19, 2013

Watching for the return of the light

.

My sister-in-law Wendy Francisco (who did the art for Yeshua’s Cat’s front cover) has insisted that I would find myself adding new pages to the Cat from time to time, and I have equally firmly replied that I never would. Well, Wendy won. Over the last two or three weeks that unmistakable nudge (much like a cat butting her head against your chest) has been growing more insistent.

And, Donna West, it was your kind comment on my post about the cat who inspired the book that pushed the nudge into actual words, drawing me out of the busy-ness of publishing concerns and back into Mari’s world.

So, I wish each of you a blessed Christmas, and as a gift from Mari to you, here are a few new words from her, never published before–perhaps for some later edition.

For those of you who have the paperback edition, this would be inserted at the top of page 124, just after “. . . filled with laughter.” For those of you with the Kindle edition, it’s in Chapter 15, Magdala, just after Mari muses about the nature of the festival of lights, and before Yeshua starts speaking on the last night of the feast.

* * *

One night after everyone had gone to bed I finally asked him. “Are your people celebrating the return of the sun’s warmth when they celebrate their festival of lights, son of Earth?”

“Yes and no, little mother,” he replied, turning his head and smiling as he opened his eyes. “We measure the years by the seasons of the moon, not by the sun’s path, so none of our holy days takes note of the sun’s movement, not even this one. No, this week we rejoice in events almost 200 years past, when a great man named Judas Maccabeus cleansed the Temple in Jerusalem from the pollution of a pagan altar put there by foreign conquerors. Our many lamps call us to remember that the One’s light can dispel even the deepest darkness.”

He rose to his feet and reached out his arm in invitation, so I leapt to his shoulder, wrapping my tail around his neck. Together we walked out under the winter sky and stood on the hill, watching the stars touch the great sea with their cold fire.

“Yet, little leopard,” he continued as if he had never paused, “you are right when you wonder if we are also welcoming the sun’s return. Just as stars grow brighter in the long nights, each light that burns in winter’s darkness whispers of that hope. Together with all Earth’s children, our hearts grow full when we see the sun begin its long journey back to the heights of heaven. This too reminds us of the One’s faithfulness.”

I curled around his neck more closely to dispel the night’s chill, but I said nothing. I only purred with pleasure at his closeness. I sensed that words still lay unspoken in his heart.

“Sweet Mari, my mother told me that I was born on a night like this, when the stars danced in a black sky, and the breath of humans and beasts alike clouded vision with their brief mist. Joy filled the night and sang in the heavens at the wonder of my coming into the world. All things were made new under that sky, she said.”

I rubbed my whiskers against his cheek, and he continued.

“I can almost hear the heavens singing on such nights. The One’s face shimmers behind the host of stars like a distant oasis in the heat of a desert’s summer day. And yet the chill of a winter night and the searing heat of the desert’s noon both lie quiet in the hollow of his hand.

“As do you and I.”

.

.

December 8, 2013

The First “Christmas” Art

.

Catacomb of St Callisto, Rome. Photo by Jim Forest

Did you know that most of the very early “Christmas” art that has survived into the present is in the catacombs around Rome?

The Annunciation, Catacomb of Priscilla, 2nd C CE

Perhaps the earliest known Christian painting is a simple 2nd century portrayal of the Annunciation, on the dome of a tomb in the Catacomb of Priscilla. But dating wall paintings is an inexact science at times, and many believe the paintings at Dura Europos to be earlier.

Virgin and Child with Balaam, Catacomb of Priscilla, 3rd C CE

A painting of the Madonna and Child in the same catacomb complex has been dated to the late 3rd century. These paintings were done in the popular Roman style of the time.

Much of what remains of early Christian art has been discovered in these catacombs, which were used primarily from the 2nd through the 8th centuries CE. They were closed in the 9th century, mainly because of repetitive destruction by invading Goths and Lombards.

Crosses were not common among the earliest symbols. Instead, the Chi Rho, Good Shepherd, fish, anchors, alpha and omega, and praying figures known as “orants” were typically used to decorate tombs. The Good Shepherd in particular was also a common symbol for pagan Roman burials.

Orant figure, Catacomb of Priscilla, 3rd C

Good Shepherd, Catacomb of Domatilla, 3rd C

Jesus with Alpha and Omega, Catacomb of Sts Peter and Marcellinus, 4th C

Chi Rho, 3rd C catacomb

The Magi before Herod, 431, Santa Maria Maggiore

Not until after 313, when the Edict of Milan made the practice of Christianity legal throughout the Roman Empire, did Christian art become more public, and eventually, more complex. The Magi with their gifts was a favorite theme in the 4th and 5th centuries, as was the Annunciation, the angels singing praises, and the Virgin and Child; however, Mary was most often portrayed solemnly, seated on a throne with the child in her lap.

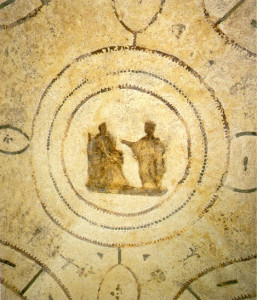

There has been some discussion about whether the arrow-like symbols in the painting below of Jesus with Peter and Paul might also be angels.

Angel, 530, San Vitale, Ravenna

Virgin and Child, 560, St. Apollinaire Nuovo

Christ with Peter and Paul–and possibly angels, 3rd-4th C, Catacomb of Sts Peter and Marcellinus

After the first millennium artists began to “humanize” the nativity, adding details to the scene and softening Mary’s appearance. Finally, by the 1300’s the classical paintings we’re familiar with today began to emerge.

Virgin and Child, 13th C stained glass, England

Adoration of the Magi, Luca di Tomme, 1365

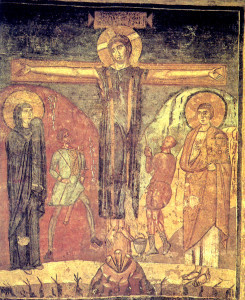

Interestingly enough, the first portrayal of Jesus on the cross didn’t appear until sometime between the 6th and 8th centuries.

Possible crucifixion or possible orant figures, Santa Sabina, Rome, 6th C

Crucifixion, 8th C, Santa Maria Antigua

.

December 3, 2013

Advent puzzle page

.

Find-Yeshua’s-Cat-in-the-Christmas-Painting game page is live for the month of December only. You’ll find detailed, high-resolution Christmas paintings from history–with one minor addition to each: Yeshua’s cat Mari has hidden herself somewhere among the details, and it’s up to you to find her! Sometimes she’s fairly easy to find, sometimes harder. Below is a sample of one of the paintings, but without high-resolution.

I’ll be adding pictures each day throughout Advent. Although I’ve started off with several paintings at once, I’ve decided to make it a Yeshua’s Cat virtual Advent Calendar, with one painting posted late at night for each of the following days of Advent. How much more wonderful a way could there be to anticipate Christmas than with the beauty of the art it has inspired through the years?

Merry Christmas!

And Happy New Year! As of January 1, the Advent puzzles have been taken down. Look for them again next December 1st.

.