Louis Arata's Blog, page 22

February 24, 2014

Storytelling: Picking Apart

In my last blog, I posted samples of a first draft and a later draft of a paragraph. Here they are again:

FIRST DRAFT:

“I could as easily start with a description of her, Eileen Hesperin, who initially interviewed me for a magazine piece about Living with AIDS. I don’t know how my name came up, out of the myriad, but I said sure, and she offered to come over on Saturday. She was an attractive woman in her late thirties, with scoops of pale brown hair nested over her ears, and a lean chiseled cut to her cheekbones. She shook hands with authority and a firm grip, and maneuvered easily along lines of professional friendliness to put me at ease, I suppose. A fierce, intelligent smile, and a strong voice that commanded attention. I met her at a coffee shop early enough in the afternoon so that we would not be distracted by customers.”

CURRENT DRAFT:

“I could easily start my story with a description of Eileen Hesperin, an attractive woman in her late thirties, with curly brown hair. She had a smooth, round face, and tiny pucker that hid her tiger’s smile. While her handshake was a throw-down, her professional courtesy was intended to put me at ease. I met her at a coffee shop early in the afternoon when few other customers were around.”

How did I choose which changes to make? The first draft meanders into the story, mixing a description of Eileen with the purpose of the interview. I spend a lot of time describing her appearance and mannerisms. It felt better to get down to business.

Eileen’s physical appearance changes between the two drafts too. I decided that giving her curly hair and a round face was a good contrast to her tiger’s smile. Plus, a tiger’s smile is more evocative than a “fierce, intelligent smile.” It gives a sense of threat. A lot of the details get trimmed down. My first drafts tend to emulate Victorian novels, and my subsequent drafts try to use more contemporary language.

Next, the reason for the interview comes out in the dialogue, so it wasn’t necessary to explain it in the first paragraph.

Overall, I like the current version. Given that I am still working on this latest revision, there may be a few more changes, but I feel like I’m moving in the right direction.

FIRST DRAFT:

“I could as easily start with a description of her, Eileen Hesperin, who initially interviewed me for a magazine piece about Living with AIDS. I don’t know how my name came up, out of the myriad, but I said sure, and she offered to come over on Saturday. She was an attractive woman in her late thirties, with scoops of pale brown hair nested over her ears, and a lean chiseled cut to her cheekbones. She shook hands with authority and a firm grip, and maneuvered easily along lines of professional friendliness to put me at ease, I suppose. A fierce, intelligent smile, and a strong voice that commanded attention. I met her at a coffee shop early enough in the afternoon so that we would not be distracted by customers.”

CURRENT DRAFT:

“I could easily start my story with a description of Eileen Hesperin, an attractive woman in her late thirties, with curly brown hair. She had a smooth, round face, and tiny pucker that hid her tiger’s smile. While her handshake was a throw-down, her professional courtesy was intended to put me at ease. I met her at a coffee shop early in the afternoon when few other customers were around.”

How did I choose which changes to make? The first draft meanders into the story, mixing a description of Eileen with the purpose of the interview. I spend a lot of time describing her appearance and mannerisms. It felt better to get down to business.

Eileen’s physical appearance changes between the two drafts too. I decided that giving her curly hair and a round face was a good contrast to her tiger’s smile. Plus, a tiger’s smile is more evocative than a “fierce, intelligent smile.” It gives a sense of threat. A lot of the details get trimmed down. My first drafts tend to emulate Victorian novels, and my subsequent drafts try to use more contemporary language.

Next, the reason for the interview comes out in the dialogue, so it wasn’t necessary to explain it in the first paragraph.

Overall, I like the current version. Given that I am still working on this latest revision, there may be a few more changes, but I feel like I’m moving in the right direction.

Published on February 24, 2014 12:18

February 23, 2014

Storytelling: First Paragraph

On a writing forum, writers were sharing the opening paragraph of their current project. The predominant question was whether it grabbed the reader’s attention. Most wanted an honest critique, and for the most part, people complied. A few did get snipey debating the necessity of proper grammar – whether using good grammar was a requirement for a compelling first paragraph.

What I would love to see is the various iterations of the first paragraph, from first to current draft. How did the writer change the language? How did she hone it down to gristle and bone?

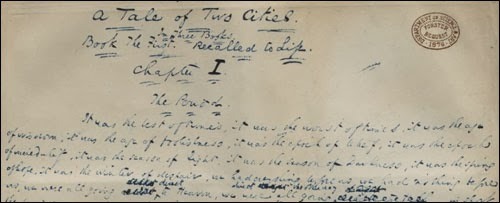

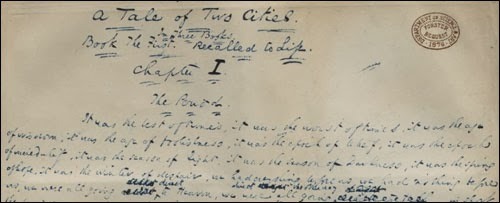

One of the most famous opening paragraphs is Dickens’ A Tale of Two Cities:

“It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity, it was the season of Light, it was the season of Darkness, it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair, we had everything before us, we had nothing before us, we were all going direct to heaven, we all going direct the other way – in short, the period was so far like the present period, that some of its noisiest authorities insisted on its being received, for good or for evil, in the superlative degree of comparison only.”

What did Dickens’ first draft look like? Did the language spring perfectly from his head? My guess is that he had to craft it to make it ring.

Facsimile of the first lines of the manuscript, Victoria and Albert Museum

Facsimile of the first lines of the manuscript, Victoria and Albert Museum

Sometimes I remind myself it’s okay to have a shitty, meandering first draft (thanks, Anne Lamott). Eventually through revision I will get to the language I want.

Here’s a first-draft sample from my current project, Reston Peace. This is not the first paragraph, but the first one in the narrator’s (Kenny’s) voice:

“I could as easily start with a description of her, Eileen Hesperin, who initially interviewed me for a magazine piece about Living with AIDS. I don’t know how my name came up, out of the myriad, but I said sure, and she offered to come over on Saturday. She was an attractive woman in her late thirties, with scoops of pale brown hair nested over her ears, and a lean chiseled cut to her cheekbones. She shook hands with authority and a firm grip, and maneuvered easily along lines of professional friendliness to put me at ease, I suppose. A fierce, intelligent smile, and a strong voice that commanded attention. I met her at a coffee shop early enough in the afternoon so that we would not be distracted by customers.”

This is what it looks like now:

“I could easily start my story with a description of Eileen Hesperin, an attractive woman in her late thirties, with curly brown hair. She had a smooth, round face, and tiny pucker that hid her tiger’s smile. While her handshake was a throw-down, her professional courtesy was intended to put me at ease. I met her at a coffee shop early in the afternoon when few other customers were around.”

While the first version meanders into the story, the second version gets down to business. The purpose of the interview comes later in Eileen’s conversation, rather than in an expository line.

[As a further example of tightening language, here’s the first draft of the previous paragraph: “The second version gets down to business, while the first one meanders into the story. The purpose of the interview comes later, in the conversation, rather than in an expository line. Right now, I like the crispness of the current version, but since I’m still working on this draft, it will likely change, not radically, but hopefully in a manner that will make it crisper.”

At this rate, I could write an entire blog in which I give examples of each paragraph as I write it … ]

In my next blog, I’ll pick apart why I made the changes that I did.

What I would love to see is the various iterations of the first paragraph, from first to current draft. How did the writer change the language? How did she hone it down to gristle and bone?

One of the most famous opening paragraphs is Dickens’ A Tale of Two Cities:

“It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity, it was the season of Light, it was the season of Darkness, it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair, we had everything before us, we had nothing before us, we were all going direct to heaven, we all going direct the other way – in short, the period was so far like the present period, that some of its noisiest authorities insisted on its being received, for good or for evil, in the superlative degree of comparison only.”

What did Dickens’ first draft look like? Did the language spring perfectly from his head? My guess is that he had to craft it to make it ring.

Facsimile of the first lines of the manuscript, Victoria and Albert Museum

Facsimile of the first lines of the manuscript, Victoria and Albert MuseumSometimes I remind myself it’s okay to have a shitty, meandering first draft (thanks, Anne Lamott). Eventually through revision I will get to the language I want.

Here’s a first-draft sample from my current project, Reston Peace. This is not the first paragraph, but the first one in the narrator’s (Kenny’s) voice:

“I could as easily start with a description of her, Eileen Hesperin, who initially interviewed me for a magazine piece about Living with AIDS. I don’t know how my name came up, out of the myriad, but I said sure, and she offered to come over on Saturday. She was an attractive woman in her late thirties, with scoops of pale brown hair nested over her ears, and a lean chiseled cut to her cheekbones. She shook hands with authority and a firm grip, and maneuvered easily along lines of professional friendliness to put me at ease, I suppose. A fierce, intelligent smile, and a strong voice that commanded attention. I met her at a coffee shop early enough in the afternoon so that we would not be distracted by customers.”

This is what it looks like now:

“I could easily start my story with a description of Eileen Hesperin, an attractive woman in her late thirties, with curly brown hair. She had a smooth, round face, and tiny pucker that hid her tiger’s smile. While her handshake was a throw-down, her professional courtesy was intended to put me at ease. I met her at a coffee shop early in the afternoon when few other customers were around.”

While the first version meanders into the story, the second version gets down to business. The purpose of the interview comes later in Eileen’s conversation, rather than in an expository line.

[As a further example of tightening language, here’s the first draft of the previous paragraph: “The second version gets down to business, while the first one meanders into the story. The purpose of the interview comes later, in the conversation, rather than in an expository line. Right now, I like the crispness of the current version, but since I’m still working on this draft, it will likely change, not radically, but hopefully in a manner that will make it crisper.”

At this rate, I could write an entire blog in which I give examples of each paragraph as I write it … ]

In my next blog, I’ll pick apart why I made the changes that I did.

Published on February 23, 2014 12:16

February 22, 2014

Storytelling: Backwards

"How can I tell what I think till I see what I say?" -- E.M. Forster, Aspects of the Novel (1927)

Writing a first draft is fairly linear: start at the beginning and move to the end. But lately I'm discovering that subsequent drafts require writing backwards.

Events that occur later in the story end up influencing what comes before it. In Dead Hungry, it wasn't until I knew that Joyce would become an Amazon that I could construct the trajectory of her story.

In my play, A Careful Wish, the climax involves a comic reenactment of "The Monkey's Paw." In the middle of the night, there's a knock on the door. Frances is panicked that it's her dead son returned. Her husband, Edgar, says, "Calm yourself, Frances. What the hell's the matter with you? It's not the Monkey's Paw."

In the first draft of the play, that was the only reference to W. W. Jacobs' story. I realized I had to set up the reference earlier, so I put in a scene in which Kyle tells his nephew a bowdlerized version of the tale.

Right now I'm working on Reston Peace. To figure out Kenny Reston's trajectory through self-destructive behavior and near-suicide (and, thankfully, recovery) requires me to work backwards to the origins of the sexual abuse he suffered as a child.

In the middle of the book, when Kenny is in college, he tries to protect a friend in an abusive relationship. I realized that this protective quality must have been there in his childhood; it was the piece he wanted for himself -- someone to protect him. That quality becomes the fulcrum of his character.

So, knowing those later key points help inform the beginning of the story. The craft of storytelling, I'm discovering, is rarely linear.

Writing a first draft is fairly linear: start at the beginning and move to the end. But lately I'm discovering that subsequent drafts require writing backwards.

Events that occur later in the story end up influencing what comes before it. In Dead Hungry, it wasn't until I knew that Joyce would become an Amazon that I could construct the trajectory of her story.

In my play, A Careful Wish, the climax involves a comic reenactment of "The Monkey's Paw." In the middle of the night, there's a knock on the door. Frances is panicked that it's her dead son returned. Her husband, Edgar, says, "Calm yourself, Frances. What the hell's the matter with you? It's not the Monkey's Paw."

In the first draft of the play, that was the only reference to W. W. Jacobs' story. I realized I had to set up the reference earlier, so I put in a scene in which Kyle tells his nephew a bowdlerized version of the tale.

Right now I'm working on Reston Peace. To figure out Kenny Reston's trajectory through self-destructive behavior and near-suicide (and, thankfully, recovery) requires me to work backwards to the origins of the sexual abuse he suffered as a child.

In the middle of the book, when Kenny is in college, he tries to protect a friend in an abusive relationship. I realized that this protective quality must have been there in his childhood; it was the piece he wanted for himself -- someone to protect him. That quality becomes the fulcrum of his character.

So, knowing those later key points help inform the beginning of the story. The craft of storytelling, I'm discovering, is rarely linear.

Published on February 22, 2014 07:58

February 17, 2014

Never Land

About ten years ago, I was sitting outside Cobb Hall on the University of Chicago campus. It was a beautiful spring day, and the Classics Quadrangle was filled with students. I was eating my lunch and reading, when I became aware of some music -- Rhapsody in Blue -- coming from one of the music practice rooms. The pianist was energetically alive, so much so that I stopped what I was doing so I could listen to this astounding piece. When it was over, I wish I had applauded.

My short story "Never Land" is my belated applause.

Never Land

My short story "Never Land" is my belated applause.

Never Land

Published on February 17, 2014 07:00

February 11, 2014

reblog: Lifting Characters Off The Page.

An interesting blog on writing characters. I do a similar thing in which I "audition" a character in a scene.

mooderino.tumblr.com

mooderino.tumblr.com

Published on February 11, 2014 11:45

February 6, 2014

Dead Hungry is available at NoiseTrade.com

There's an exciting website called NoiseTrade that has introduced me to a lot of new music. Now they're offering the same great service for e-books.

I've just uploaded Dead Hungry, which is available in pdf, mobi, and epub formats. Check it out!

http://books.noisetrade.com/louisarata

Published on February 06, 2014 09:06

February 3, 2014

Feedback

I’ve gotten a few reviews and some feedback on Dead Hungry. Not surprisingly, what works for one reader doesn’t for another. Some sample feedback (paraphrased):

“I loved the massacre scene at a food competition.”

“I thought the massacre at the food competition was too much. Too repetitive.”

“Great grisly depictions of Ghoul feasts.”

“The grossness became too much. I felt myself detaching from the characters.” This reader couldn’t finish the novel.

“Some of the characters – Robber and Freddie – were just too damned irritating!”

“I loved Joyce’s story, and how she became an Amazon.”

“I got confused by the number of characters.”

The one consensus was that Joyce’s story was the most compelling. I confess that this strikes me as funny – not that people found it interesting, but rather that I didn’t come up with her story until late in the planning process. Somewhere in the first draft I realized that one of the main characters should be a Ghoul, and through process of elimination it fell to Joyce. But she proved to be the perfect character for the story.

The readers and reviews gave such thoughtful care in describing their response that I felt they justified their claims. Setting my ego aside, I can see their points. So I get to store away their suggestions for my next book. I will trim my “cast of thousands,” will pay attention to repetition, will take note of what worked in Joyce’s story but didn’t work in Freddie and Robber’s.

The readers have spoken.

“I loved the massacre scene at a food competition.”

“I thought the massacre at the food competition was too much. Too repetitive.”

“Great grisly depictions of Ghoul feasts.”

“The grossness became too much. I felt myself detaching from the characters.” This reader couldn’t finish the novel.

“Some of the characters – Robber and Freddie – were just too damned irritating!”

“I loved Joyce’s story, and how she became an Amazon.”

“I got confused by the number of characters.”

The one consensus was that Joyce’s story was the most compelling. I confess that this strikes me as funny – not that people found it interesting, but rather that I didn’t come up with her story until late in the planning process. Somewhere in the first draft I realized that one of the main characters should be a Ghoul, and through process of elimination it fell to Joyce. But she proved to be the perfect character for the story.

The readers and reviews gave such thoughtful care in describing their response that I felt they justified their claims. Setting my ego aside, I can see their points. So I get to store away their suggestions for my next book. I will trim my “cast of thousands,” will pay attention to repetition, will take note of what worked in Joyce’s story but didn’t work in Freddie and Robber’s.

The readers have spoken.

Published on February 03, 2014 08:57

January 24, 2014

I Want To Hold Your Hand

My grandmother was a white-haired cherub with a delightful giggle. After thirty-odd grandchildren, she also developed the wisdom to let kids be kids.

I was seven and reading a book with her. I finished the first page, turned to page two then stopped because I had to make sure she was following the story. Turning back to page one, I pointed to a particular sentence. "See? You remember Tommy was the boy who lived in the yellow house?"

"Yes, I remember."

I got to page four before I stopped again. "Tommy's the one who was riding a bicycle on page three."

"I remember."

Even so, I pointed to the appropriate paragraph. I was amazed that she was following the story. My diligence was partly due to fear that I couldn't retain her attention but also due to a fascination with how a writer keeps a reader engaged from page to page.

Even when I read on my own, I was always backtracking to significant plot points, teaching myself that it's these series of events that make the story unfold. In the novel Bambi, I became captivated by one chapter in which one leaf speaks to another as the autumn arrives. Poignantly, one leaf falls, leaving the other one alone. I kept coming back to this chapter because I was fascinated by how the author used the scenario to detail the transition of one season to another.

Dickens is masterful at little refrains, catchphrases, and physical traits to help readers keep track of the cast of characters. Scrooge's "Bah! Humbug!" Micawber's "Something will turn up." Uriah Heep's "humbleness."

Little details like that still captivate me, so when I write stories, I stay aware of how to leader the reader through. It's sort of like holding the reader's hand: "Follow me. I know the way. This is what comes next. Do you see how this connects to the previous chapter? Trust me; it'll all make sense."

(Photo: Missione genovese del Guaricano - Santo Domingo (Dominican Republic), by Twice25)

(Photo: Missione genovese del Guaricano - Santo Domingo (Dominican Republic), by Twice25)

But how to do that without using the written equivalent of a sledgehammer? How do you convey to your audience what is important? How do you hold their hand?

I'd love to hear what techniques other writers use, as well as the details that capture a reader's attention. What are your favorite tricks? Please leave a comment below.

I was seven and reading a book with her. I finished the first page, turned to page two then stopped because I had to make sure she was following the story. Turning back to page one, I pointed to a particular sentence. "See? You remember Tommy was the boy who lived in the yellow house?"

"Yes, I remember."

I got to page four before I stopped again. "Tommy's the one who was riding a bicycle on page three."

"I remember."

Even so, I pointed to the appropriate paragraph. I was amazed that she was following the story. My diligence was partly due to fear that I couldn't retain her attention but also due to a fascination with how a writer keeps a reader engaged from page to page.

Even when I read on my own, I was always backtracking to significant plot points, teaching myself that it's these series of events that make the story unfold. In the novel Bambi, I became captivated by one chapter in which one leaf speaks to another as the autumn arrives. Poignantly, one leaf falls, leaving the other one alone. I kept coming back to this chapter because I was fascinated by how the author used the scenario to detail the transition of one season to another.

Dickens is masterful at little refrains, catchphrases, and physical traits to help readers keep track of the cast of characters. Scrooge's "Bah! Humbug!" Micawber's "Something will turn up." Uriah Heep's "humbleness."

Little details like that still captivate me, so when I write stories, I stay aware of how to leader the reader through. It's sort of like holding the reader's hand: "Follow me. I know the way. This is what comes next. Do you see how this connects to the previous chapter? Trust me; it'll all make sense."

(Photo: Missione genovese del Guaricano - Santo Domingo (Dominican Republic), by Twice25)

(Photo: Missione genovese del Guaricano - Santo Domingo (Dominican Republic), by Twice25)But how to do that without using the written equivalent of a sledgehammer? How do you convey to your audience what is important? How do you hold their hand?

I'd love to hear what techniques other writers use, as well as the details that capture a reader's attention. What are your favorite tricks? Please leave a comment below.

Published on January 24, 2014 06:48

January 21, 2014

Editing Tips

Published on January 21, 2014 10:29

January 13, 2014

Storytelling: Necessity

Storytelling is like a jigsaw puzzle when you don’t always knows the number of pieces you need to complete the picture.

When I write a first draft, I feel like I’m finding all the end pieces and putting together the frame, then fitting in the pieces that make up the primary images of the picture.

What I don’t always know is that I might need to create a piece to fit a particular hole in the story.

In Dead Hungry, the character of Steiner came about out of necessity. There was a hole in Joyce’s story. As Joyce discovers that she is a Ghoul, at first she is mentored by Hector, the leader of a small Ghoul community. Originally, Hector was going to be the one to teach her the ins and outs of feeding on the dead.

Except Joyce had no emotional connection to Hector. He is so busy being a respectable Ghoul that he overlooks that others might not be as comfortable with eating corpses. Joyce needed someone who could empathize with her struggle whether to give into to her Ghoul nature.

Enter Steiner. Practically feral, he recognizes Joyce’s unexpressed desire to hunt and attempts to coach her through the animal nature to kill and feed.

But that’s not what Joyce wants. She’s fighting to retain her humanity, and Steiner represents the exact opposite.

In the first draft, Steiner was a minor character in only one scene which didn’t even involve Joyce. But as I continued to develop her story, I needed more Ghouls to fill out the community. Then as I discovered the depth of Joyce’s struggles, I realized that Steiner spoke to that animal hunger.

When I started writing the book, Steiner was nowhere to be found. By the time I finished revising it, he’d become an integral part of Joyce’s story.

The story had a Steiner-shaped hole, and the only way to fill it was to create him.

When I write a first draft, I feel like I’m finding all the end pieces and putting together the frame, then fitting in the pieces that make up the primary images of the picture.

What I don’t always know is that I might need to create a piece to fit a particular hole in the story.

In Dead Hungry, the character of Steiner came about out of necessity. There was a hole in Joyce’s story. As Joyce discovers that she is a Ghoul, at first she is mentored by Hector, the leader of a small Ghoul community. Originally, Hector was going to be the one to teach her the ins and outs of feeding on the dead.

Except Joyce had no emotional connection to Hector. He is so busy being a respectable Ghoul that he overlooks that others might not be as comfortable with eating corpses. Joyce needed someone who could empathize with her struggle whether to give into to her Ghoul nature.

Enter Steiner. Practically feral, he recognizes Joyce’s unexpressed desire to hunt and attempts to coach her through the animal nature to kill and feed.

But that’s not what Joyce wants. She’s fighting to retain her humanity, and Steiner represents the exact opposite.

In the first draft, Steiner was a minor character in only one scene which didn’t even involve Joyce. But as I continued to develop her story, I needed more Ghouls to fill out the community. Then as I discovered the depth of Joyce’s struggles, I realized that Steiner spoke to that animal hunger.

When I started writing the book, Steiner was nowhere to be found. By the time I finished revising it, he’d become an integral part of Joyce’s story.

The story had a Steiner-shaped hole, and the only way to fill it was to create him.

Published on January 13, 2014 17:36