Louis Arata's Blog, page 18

October 1, 2014

Re-Reading

All the books on my bookshelves I’ve read. Many of them I’ve read more than once.

About ten years ago, I had well over 750 books, double-stacked and crammed into every crevice of the bookcases. All the shelves were two rows deep, so I started stacking them on top.

I always wanted a huge library, something like the Beast’s in that Disney movie. But then I helped pack up a friend’s home for moving, and they had sixty years’ worth of books scattered throughout the house and boxed up in the basement. We’re talking over a hundred boxes of books. The books had been crammed together so long, the covers stuck together from compression.

I really should have alphabetized them ...It kind of cured me of accumulating a lifetime’s worth of reading.

I really should have alphabetized them ...It kind of cured me of accumulating a lifetime’s worth of reading.

Instead, I did a big clear-out, keeping only the books that I absolutely love and would want to read again: Dickens, Eliot, Melville, Steinbeck. Jane Smiley, John Irving, Kazuo Ishiguro. Vikram Seth’s A Suitable Boy. Patricia A. McKillip’s The Riddlemaster of Hedtriology. Mary Roach’s Stiff. The Best American Nonrequired Reading series.

I love going back to re-read something. I usually wait until the story calls to me again – something reminds me of it or I catch a reference to the author, or a scene pops into my head. Then I approach the book with a completely different lens. I’m remembering bits and pieces of it, but now I want to see if my memory is accurate. I want to know if that scene unfolded the way I think it does.

I get a lot of comfort out of the familiarity of a tale. It’s probably why I like to watch the same movies over and over again. It’s like putting on well-worn sweatpants, warm socks, and sweatshirt, and curling up on the sofa. Burrowing down into a blanket and covering yourself with rediscovered sensations.

But it also appeals to my writer’s brain. I get to pay attention to the author’s craft. How they put the pieces together. Having the overall flow of the book already in my head helps me pick up the clues along the way – the reference to the flowers by the side of the road, the significance of a letter in the mailbox. The vocabulary of word crumbs that leads a reader through the fictional landscape.

The only drawback to re-reading the same books is that it takes time away from discovering new ones. I’m trying to balance between the two. Just yesterday I started a new book – You, by Charles Benoit. Very compelling and curious, a great find. And I started an old book that I read when I was fourteen – Harvest Home, by Thomas Tryon. Scenes of that book have stayed in my mind, but now I get to learn how accurate my memory is. And now that I’m older, I get to appreciate the craft of the novel as opposed to only the thrill of the Modern Gothic (which was what appealed to me as a teen).

By the time I finish Benoit’s You, I’ll have to decide if it will join the other books to be re-read. I kind of hope that it does.

About ten years ago, I had well over 750 books, double-stacked and crammed into every crevice of the bookcases. All the shelves were two rows deep, so I started stacking them on top.

I always wanted a huge library, something like the Beast’s in that Disney movie. But then I helped pack up a friend’s home for moving, and they had sixty years’ worth of books scattered throughout the house and boxed up in the basement. We’re talking over a hundred boxes of books. The books had been crammed together so long, the covers stuck together from compression.

I really should have alphabetized them ...It kind of cured me of accumulating a lifetime’s worth of reading.

I really should have alphabetized them ...It kind of cured me of accumulating a lifetime’s worth of reading.Instead, I did a big clear-out, keeping only the books that I absolutely love and would want to read again: Dickens, Eliot, Melville, Steinbeck. Jane Smiley, John Irving, Kazuo Ishiguro. Vikram Seth’s A Suitable Boy. Patricia A. McKillip’s The Riddlemaster of Hedtriology. Mary Roach’s Stiff. The Best American Nonrequired Reading series.

I love going back to re-read something. I usually wait until the story calls to me again – something reminds me of it or I catch a reference to the author, or a scene pops into my head. Then I approach the book with a completely different lens. I’m remembering bits and pieces of it, but now I want to see if my memory is accurate. I want to know if that scene unfolded the way I think it does.

I get a lot of comfort out of the familiarity of a tale. It’s probably why I like to watch the same movies over and over again. It’s like putting on well-worn sweatpants, warm socks, and sweatshirt, and curling up on the sofa. Burrowing down into a blanket and covering yourself with rediscovered sensations.

But it also appeals to my writer’s brain. I get to pay attention to the author’s craft. How they put the pieces together. Having the overall flow of the book already in my head helps me pick up the clues along the way – the reference to the flowers by the side of the road, the significance of a letter in the mailbox. The vocabulary of word crumbs that leads a reader through the fictional landscape.

The only drawback to re-reading the same books is that it takes time away from discovering new ones. I’m trying to balance between the two. Just yesterday I started a new book – You, by Charles Benoit. Very compelling and curious, a great find. And I started an old book that I read when I was fourteen – Harvest Home, by Thomas Tryon. Scenes of that book have stayed in my mind, but now I get to learn how accurate my memory is. And now that I’m older, I get to appreciate the craft of the novel as opposed to only the thrill of the Modern Gothic (which was what appealed to me as a teen).

By the time I finish Benoit’s You, I’ll have to decide if it will join the other books to be re-read. I kind of hope that it does.

Published on October 01, 2014 07:33

September 29, 2014

Reading (Not Reading)

I read several books at once. Not simultaneously. That would make it difficult to follow the stories.

[image error] "It is a truth universally acknowledged ... that a Hobbit living in a hole in the ground ...

shall turn out to be the hero of my own life ... "

Huh?I cycle through three or four books, reading a few chapters, moving to the next one, and coming back around to the first. Maybe it’s an issue of lack of focus. Maybe it’s a voracious appetite for books. If I could read with a book in each hand, I bet I would.

The pattern goes like this: Read Book One, get about a quarter of the way in, then start Book Two. Alternate between the two. Then someone mentions a really good book, so you start Book Three. Now you’re feeling guilty that you’re not reading Book One. Plus there’s Book Two waiting for some together-time. But what about Book Four tempting you from the wings?

Okay, maybe it is lack of focus.

In any case, I always have something to read. I finish Book One, start Books Four and Five, finish Book Two, etc.

Occasionally I finish up all the books, one right after the other, leaving me with nothing to read. That’s where I am today. This weekend, I finished up my last two books. Both of them were enjoyable, and I’m still savoring their taste. I didn’t want either of them to end.

But I’m supposed to be reading!

When this happens, I usually grab something off my shelves, even if it’s something I’ve read before. Practically all the books on my shelves I’ve read at least once. In the case of Walden, The Lord of the Rings, Pride and Prejudice, and A Prayer for Owen Meany, I’ve read them multiple times.

So, today I’m Not Reading. And it’s a tough spot to be in. Since I don’t know what I want to read yet, it’s kind of like being really hungry but not having a taste for any particular food.

Books evidently are food.

[image error] This is going to be a heavy meal.

I’m trying to sit with this feeling, to live with the mild anxiety Not Reading produces. My brain wants exercise, but maybe it’s a good idea to take a rest, even if only for 24 hours.

Tomorrow, I’ll hit the library.

[image error] "It is a truth universally acknowledged ... that a Hobbit living in a hole in the ground ...

shall turn out to be the hero of my own life ... "

Huh?I cycle through three or four books, reading a few chapters, moving to the next one, and coming back around to the first. Maybe it’s an issue of lack of focus. Maybe it’s a voracious appetite for books. If I could read with a book in each hand, I bet I would.

The pattern goes like this: Read Book One, get about a quarter of the way in, then start Book Two. Alternate between the two. Then someone mentions a really good book, so you start Book Three. Now you’re feeling guilty that you’re not reading Book One. Plus there’s Book Two waiting for some together-time. But what about Book Four tempting you from the wings?

Okay, maybe it is lack of focus.

In any case, I always have something to read. I finish Book One, start Books Four and Five, finish Book Two, etc.

Occasionally I finish up all the books, one right after the other, leaving me with nothing to read. That’s where I am today. This weekend, I finished up my last two books. Both of them were enjoyable, and I’m still savoring their taste. I didn’t want either of them to end.

But I’m supposed to be reading!

When this happens, I usually grab something off my shelves, even if it’s something I’ve read before. Practically all the books on my shelves I’ve read at least once. In the case of Walden, The Lord of the Rings, Pride and Prejudice, and A Prayer for Owen Meany, I’ve read them multiple times.

So, today I’m Not Reading. And it’s a tough spot to be in. Since I don’t know what I want to read yet, it’s kind of like being really hungry but not having a taste for any particular food.

Books evidently are food.

[image error] This is going to be a heavy meal.

I’m trying to sit with this feeling, to live with the mild anxiety Not Reading produces. My brain wants exercise, but maybe it’s a good idea to take a rest, even if only for 24 hours.

Tomorrow, I’ll hit the library.

Published on September 29, 2014 07:18

September 26, 2014

Ghouls Rule!

Halloween is coming,and the Ghouls are getting hungry.Enter for a chance to win

Dead Hungry

at GoodReads.com.

Halloween is coming,and the Ghouls are getting hungry.Enter for a chance to win

Dead Hungry

at GoodReads.com.Dead Hungry Giveaway

An excerpt from Chapter One: First Response

“DON’T TELL me that movie didn’t suck, because it did. It was so way like that other movie with the killer in that shitty mask trying to be all Jason, but it’s also like that Wes Craven flick, you know, all self-referential, but this one, this movie, this was just crap!”Freddie combusted with caffeinated energy, his spiky red hair a halo of fire. Enveloped in two oversized t-shirts and a flannel shirt, he wore a belt almost a foot too long, and his boxers jutted over his waistband. He tried to agitate Tucker and Darien into the same state of stunned disbelief.“Can’t they come up with one frigging original idea, just once? Like we don’t know the main chick’s going to be some tough Barbie who stabs the psycho with his own ice pick. And of course you know! You know he’s going to pop up again. Boo! Ooh, I’m scared, he’s still alive! Shit, like we haven’t seen that a bazillion times before!”Freddie turned to Tucker. “Come on, admit it. It was shit. Right? It was shit.”“Yes, it was shit.”“Thank you!” Freddie took a victory lap around his friends. To celebrate, he dodged into traffic like a crazed prophet. “Skip this movie! It sucked!” He gestured wildly at the movie theater.Freddie’s antics reminded Tucker of Kevin McCarthy at the end of Invasion of the Body Snatchers, warning travelers that they’re here, they’re here, you’re next. Grinning, he threw an arm over Freddie’s shoulder and guided him down the street.Freddie proceeded to rave about overlooked classics such as Hell Hounds II: Bark Until Dark and Field of Screams, which were so much better than tonight’s Chop ‘Til You Drop. “Great title, stooopid story,” he said.“Of course it’s stupid,” said Tucker. “What did you expect? Movies like this aren’t about creativity; they’re about what sells. Sexy women, violent stalkers, grisly deaths.”“Don’t forget stupid puns as titles,” said Darien.“No movie like this is going to have an original thought in its head. It’s movie-making by cliché. Stick enough familiar elements together, market it to teenage boys, and you make enough money for a sequel.”“Exactly, exactly!” exclaimed Freddie, as though his ranting had made the same point. “They could be sooo much smarter if they did something cool.”“You’re the one who picked the movie,” said Darien.“Yeah, but still.”A hazy film of car exhaust permeated Chicago’s humid night air. Up and down Michigan Avenue, skyscrapers formed a glistening cavern. Tucker steered his friends onto the plaza next to the Tribune Tower, its neo-Gothic design infested with gargoyles watching from flying buttresses. Freddie ran ahead to pretend-skateboard along the lip of a stone planter.“Next time, I choose the movie,” Darien said privately to Tucker. “No more horror, okay? How can you stomach it?”“It’s all fodder for the dissertation.”“You don’t really like them, do you?” Darien shook his head in distaste. “You heard the guys behind us, right? Laughing their heads off when the killer cut out that girl’s tongue.”Tucker shrugged. “Horror gets more intense as violence becomes more permissible to show, but does it ever really change? The same things still scare us.”“Since when does seeing people get butchered become entertainment?”“All I want is to figure out why people enjoy a good scare. That pleasant chill of fear. Movies are a safe way to experience that. You’re not really in danger, even if you feel scared.”“Okay, I can see that’s why you watch horror movies. But Freddie?”“He’s about the gross-out factor. He’s got that catalog of all the different ways people get maimed in movies.”Darien laughed. “He’s a psycho.”“I don’t think he makes a connection between a real serial killer and the killer in Chop ‘Til You Drop. For him, they are two completely different animals. He’s a goofball, but in-between his ranting and raving, sometimes he’s got a little insight.”“Kind of hard to believe,” Darien murmured. Up ahead Freddie was executing fake skateboard maneuvers that drew cheers from a nonexistent crowd.As they crossed the plaza, Tucker looked up the height of the Tribune Tower, where bricks from other structures were embedded – Nidaros Cathedral, Corregidor, Lincoln’s Tomb. A motley assemblage of world-wide symbols. One piece, like an impressionist bird in flight, was a ribbon-shaped beam from the World Trade Center.A fragment of sobriety stuck in his chest. It seemed silly to lambast a crummy movie when there were reminders of truly horrific moments embedded in the landscape. Tucker’s parents had told him stories of where they’d been when Kennedy was shot or the Berlin Wall came down; when protestors went up in flames in Tianamen Square, or the Challenger exploded over Texas. Events became mythic as they settled into the collective consciousness: a specific date pinned to a generation’s sleeve.Tucker had been in freshman English when the news came. His teacher, typically unflappable, told everyone to go to the gym. As they filed from the room, Tucker joked with his friends that it was an impromptu pep rally or a Scared Straight seminar. That’s when his teacher choked up, and they knew it was serious.Tucker had never grasped the concept of shared experience before, not until the enormity of the terrorist attack. He had watched footage of the buildings disintegrating. They were there, and then they weren’t. For weeks afterwards, even though he had no direct connection to any deaths, he felt a hole in his heart that bled and bled and never emptied. He knew what personal tragedy was: the death of his sister. But some events were too big to comprehend. They didn’t make sense. They couldn’t make sense.Now, compared to the raw truth of September 11th, tonight’s horror movie attained a new degree of idiocy.They headed down to the Loop to a pub for a late night beer. Tucker liked seeing the city lit up along the river. The Wrigley Building glowed in sugar-coated cheerfulness, and behind it loomed the glass visage of Trump Tower. Near the DuSable Bridge, a saxophonist played an endless iteration of Auld Lang Syne.Freddie ran ahead to lean over the rail to watch the river. He pushed himself far out, balancing precariously, his feet poised like a counterweight. It unnerved Tucker to see him carelessly risking himself. He wanted to run up and catch him, but by the time he got close, Freddie had run ahead to the next intersection. Tucker had to shake off his nerves.Further south, they passed under the El tracks on Wabash Avenue. Heavy shadows formed a subterranean world. When a train roared overhead, its cars thumping, it was like a monster rising from its lair. Street lamps couldn’t cut through the grimy residue staining the buildings. Retail stores, pressed shoulder-to-shoulder, featured generic posters for kitschy clothes and jewelry. In second and third-story windows, bright neon signs advertised Tarot readings, yoga and massage.The street stretched empty and dark. Apart from the El trains, Freddie remained the greatest source of noise. He kept mercilessly teasing Darien about the movie. “You had your eyes closed the whole damn time!”Darien refused to be taunted. “I saw it. Though I wish I hadn’t.”Just then, Freddie jumped back a foot. “Holy shit!”A big rat bolted from an alley. It moved so fast, it registered only as fluid motion. In the middle of the street, it halted to pick at litter flattened in the road.A delivery van came through the intersection and crushed it. In an instant it went from being a rat to being a glossy, steaming, lumpy thing. Its leg twitched twice before becoming still.Oh god, Tucker thought.Freddie slapped Darien’s arm. “Come on,” he said, jogging toward the furry gob. He hunkered down next to it. “Poor devil never had a chance.”“Don’t be gross.”“Probably working late to support the wife and kids. I sure hope he had insurance. Notify the next of kin!” Freddie pinched one of the snapped legs and waved it at his friends. In a squeaky voice, he said, “Officer, I saw the whole thing! He was drunk, I tell you, drunk!”“Freddie, leave it alone.”Wiping his hands on his jeans, Freddie trumpeted a doleful Taps. Tucker hated to admit he wanted to laugh. Catching Freddie’s arm, he moved him away from the mess. With a second glance at the rat, Tucker felt surprisingly disturbed, as if he’d witnessed a drive-by shooting.Then something else emerged from the alley. Much larger, it shambled onto the sidewalk. Darkness hid the face, and the body was hefty with layers of soiled clothes. Without a visible face, he seemed less than human. A zombie, something Undead.The man appeared not to see them; he cut across their path at a leaden gait. Tucker gave him a wide berth, while Freddie, more fascinated than brave, hunched over to peer up into the man’s face. “Hey dude, what’s happening?”Darien tried a gentle approach. “Hey, man.” No response. To Tucker, he said, “We need to do something. He needs help.”Tucker wasn’t sure what to do. Something didn’t feel right. The man moved through his own world, disconnected from reality. What emanated from him, maybe a form of psychosis, was more than Tucker could handle. All he wanted was to get his friends to safety.Freddie walked directly up to the man. “Looking to get tanked, blotto, piss-faced? You need some change?” He rummaged loose coins from his pocket.Tucker stopped him. Freddie protested, “Hey, I’m being a good Samaritan is all.”The homeless man, visible beneath a street light, was probably white, except his skin was grimy and his beard too thick to tell. His clothes peeled like the skin of a rotting onion, his boots held together with packing tape. His overcoat had an oily sheen, like city streets after a rainstorm. Unconscious of their presence, he walked like a discarded clockwork winding down.He circled in the street, closing in on the dead rat. No cars were coming, yet even if they were, he paid no attention to his surroundings. He crouched over the rat.It was time to do something; Tucker couldn’t simply walk away. Clearly the man didn’t recognize the danger of wandering in traffic at night, in Chicago. Tucker took a step toward him then stopped.The man was eating the rat.Darien came up beside Tucker. “We should get him to a shelter. Isn’t there one on State?”“Let’s go. Now.”But now Darien saw it too, and without hesitation, he ran straight at the man and shoved him over, and still he ate, protective as a feral dog over his meal.Darien pleaded, “Stop it! God, stop it!” but the man made no effort to hide what he was doing. Holding the rat like a chicken breast, he tore it apart with his teeth.Freddie giggled in shock just before he threw up.Tucker wrestled Darien out of the way when a car was approaching. He was able to get him to the sidewalk, as the driver blasted his horn. And still the homeless man ate. Without slowing, the car swerved around him, its horn wailing into silence.Each moist mouthful made Tucker shudder. His stomach revolted, making him wish he could throw up like Freddie. Darien remained braced against him, pushing to get back to the man, to stop him, but soon the fight went out of him.Freddie stepped forward with his cell phone to capture it on video. Abruptly Tucker knocked his arm down. “Hey!”Still, he recorded the incident, and Tucker hesitated, not knowing what to do. It was sick to capture these images, and yet he didn’t prevent Freddie from taking them. Was it wrong to film it? Maybe they could show it to the authorities so they could help the man. Maybe police, social services, doctors, someone would know what to do. But Freddie’s leering grin made it more about voyeurism.Unable to stand it longer, Tucker pushed Freddie around the corner, toward State Street. They passed through alternating street lights and shadows cut to razor-sharp edges, every object immovably dense: trash containers, newspapers boxes, sign posts. As Tucker hurried his friends past clothing stores, their reflections in the opaque windows tracked them like wolves. Movement was crucial; Tucker was relentless to get them as far away as possible, until Darien pointed out they had passed the Red Line station.At the top of the stairs, they stopped. None of them knew what to say. “Man,” Darien muttered through a heavy sigh. The sound of a human voice broke the tension, freeing them to breathe again.“I, uh, was surprised,” Freddie laughed weakly, indicating the vomit on his jeans.“We’d better get home,” said Tucker. “You okay?”Darien nodded vaguely.Bleached and unsteady, Freddie swung around to point at a stray cat disappearing under a parked car. “Hey look! Dessert.”“Shut up.”“Just a joke, dude.”They took the next train heading north. After directing Freddie and Darien to take the remaining seats – needing them secure in their seats – Tucker leaned against a metal post. As his body relaxed to the rhythm of the train, he found himself narrating the incident to himself, practicing how he would tell the story, turning it into an anecdote. Hiding behind the safety of words, he could overlook the brutal truth – that a homeless man was forced to eat a rat to survive. Tucker breathed deeply through his nose, collecting the sour smell of the train as a means to distract himself. He should have done something to help the man. He watched Freddie talking to Darien; the ratcheting noise of the train masked their conversation. At least Freddie wasn’t pale anymore. Darien was harder to read; he was probably upset but wouldn’t show it.What was most important was to get his friends home safely. The train took them far from the scene of the crime. Tucker balked. Was it a crime? Weren’t they morally obligated to intervene? But what if the man had turned violent? I saw a man eat a rat. That was what he would tell people. The statement gave him more of a chill than any moment in Chop ‘Til You Drop. It was like watching the World Trade Center fall.He shook his head. Was it really akin to September 11th? No, but he didn’t have another comparison to make. The fact that he had shared this experience with Freddie and Darien gave it a communal tone, different than seeing his sister die; Stellie’s death was personal. This had been a public act, and he had failed to intervene.He checked on Freddie and Darien. Darien kept still, his arms braced against his knees, his gaze focused on a metal vent. Freddie played with his cell phone. Proudly he held it up to Tucker to show him the video he’d captured. How could he be delighted with that? Like a little kid who couldn’t comprehend the bigger picture, he giggled to himself until a sour smell reminded him of the vomit on his jeans.“This shit has got to be shared,” he announced as he sent it off to his friends.That was it; Tucker couldn’t handle that he’d walked away. He tapped Darien on the shoulder and said they were going back. At the next station, they switched trains, heading south. Tucker was relieved that clearly Darien agreed with the plan. Behind them, unsure why they were doing this, Freddie tagged along.They came out of the Red Line Station on State Street, and cut across to Wabash Avenue. The El tracks created a steel cavern that stretched ten blocks. They walked swiftly to the spot where they’d last seen the man, but of course, he wasn’t there. Tucker entered the street to find the spot where the rat had been crushed. Now there was only a smudge on the asphalt. Tucker’s heart sickened. The carcass had not been obliterated by traffic; it had been devoured – tiny bones, fur and all.He looked around. No sign of the homeless man. Sighing, Tucker admitted the pointlessness of the quest. Was it better that they had at least tried? Small consolation.Then Darien spotted the man, sitting beneath the Macy’s display windows. Now, at the point of confronting him, they doubted the best tactic to use. Cautiously they approached, half-hoping the man would run away. Instead, he sat there, utterly still, slumped in sleep.Tucker made himself crouch beside him. “Excuse me?” he said softly. “Do you need some help?” His voice was barely loud enough to hear.Darien knelt on the opposite side, and he looked at Tucker across the man. On his face were a dozen choices before he had the courage to touch the man’s arm. The man didn’t respond. He must have been sleeping heavily; that was what Tucker wanted to believe. The man’s stillness, however, warned them otherwise. The second time Darien touched him, his fingers had barely connected before the body toppled over.They didn’t need to convince themselves that the man was dead, given that half his face had been eaten off.

Published on September 26, 2014 09:03

September 23, 2014

Morph

My cat is smoking. I found cigarette butts next to the litter box, alongside Condé Nast and Cat Fancy.

My cat is smoking. I found cigarette butts next to the litter box, alongside Condé Nast and Cat Fancy.How do you deal with this? You never expect your cat will get addicted. He sleeps eighty percent of the day, so when does he have time to take on a vice?

Maybe I should have recognized his addictive personality earlier. When he was a kitten, he loved catnip. I was running late for work and tossed him a sachet of catnip, figuring he’d bat it around for a while as I got out the door. Instead, he caught it with his teeth, and RIIIIP! An herbal explosion. He looked stunned, a kid in a candy store.

Generally, catnip is harmless. Cats will play with it until the sensation wears off. When I returned that night, it was like walking into a mausoleum. The pile of catnip trailed into the bathroom. Behind the cold porcelain toilet lay my cat, stoned out of his gourd. He lazily lifted his head and blinked at me. I swept up the remnants. An hour later, he staggered out to his food bowl. A voracious attack of the munchies.

So, now, cigarettes. I confronted him as he lay sprawled on the window seat. He is a long orange tabby with a crooked whisker. “I know about the cigarettes.”

He stared stonily at me. Then he cleaned his butt.

There’s no talking to him sometimes.

At the dog park, I ran into my neighbor, Roy. His pug and my golden retriever are great buddies. I told him about the cigarettes. He wasn’t surprised.

“What else do you expect him to do all day? He gets lonesome.”

The divorce has been hard on him.

“He won’t talk about it,” I said. “He just looks away.”

Roy nodded. “Let him have his fun. Listen, what’s the life expectancy of a cat, anyway? Ten, twelve years? Fifteen tops. So proportionally, it’ll only shave off a year or two.”

“I’m surprised you’d say that, given what you’ve been through.”

“Yeah,” he sighed. We both looked at his pug, who had the spastic distraction of a cocaine addict. “I still remember finding those glass vials. Pugs, they snort, you know.”

What I couldn’t figure out was how he was getting the cigarettes. He’s an indoor cat. So, who’s his supplier?

Then I spied my golden retriever digging in the grass. When I stood over him, he looked at me guiltily – a kid pretending he hasn’t stolen a cookie. Lowering his head in shame, he vomited a wad of garbage – twigs, acorns, candy wrappers and – cleverly mixed inside – cigarette butts. Kools, Marlboros, Virginia Slims.

Great. A co-dependent dog.

I left a note for my dog-walker to make sure that the dog didn’t bring garbage into the house. Clearly she didn’t follow my request, because soon I was finding cigarette butts by the litter box again.

What bothered me more was the shot glass next to them. I could smell the whiskey.

I called my ex-wife, Marva. “The cat’s been drinking.”

“Again? I thought he was on the wagon. Four years sober. That’s like twenty-eight for a human.”

“That’s in dog-years.”

“I read there’s a high rate of recidivism in cats.”

“What are we going to do about it?”

“We? He’s your cat, remember. He’s what you wanted out of the custody battle. Try explaining that to your daughters sometimes. Do you know why he’s smoking? Is anything upsetting him?”

“He’s a cat.”

“Animals can sense when humans aren’t happy. Maybe he’s picking up something from you.”

I hung up. If Marva wouldn’t stay on the subject, I didn’t want to talk to her.

At the dog park, I ran into the regulars: Roy and Josie, Celia and Ben. I told them about the cigarettes and whiskey.

Josie said, “I had a turtle that was agoraphobic. Hid in his shell all the time.”

“I had a hamster. Obsessive-compulsive. Running on that little wheel,” said Celia.

Ben said, “I had a Doberman that chewed off his fur. We had to give him Ritalin.”

Though they could commiserate, no one had a solution.

I contacted the vet. He prescribed a nicotine patch. That didn’t work. Now my cat’s got a bald patch.

I called my dad. He said, “I had a snake with an eating disorder. All my brother’s mice. Then a guinea pig.”

“What happened to him?”

“Choked to death. Bunny slippers.”

I staged an intervention. After dragging my cat from under the bed, I placed him on the hassock in the middle of the living room.

He growled, his ears back, his crooked whisker flush with the side of his head. This was going to take Tough Love.

“It’s time to face the truth. You can’t hide it anymore.” I dumped the garbage pail right in front of him: cigarettes, whiskey bottles, catnip.

He sounded like a freight train squealing to a halt. I never saw the claws. First blood.

He disappeared into the basement. The sign of a true addict.

Ben recommended a group. Al-A-Pet. I checked out their website. Before-and-after photos of a crack-addicted tabby. They blanked out his eyes to preserve his anonymity.

They met in the basement of the local animal shelter. Most had brought their dogs or cats, in various stages of recovery. A chameleon, deep in denial, tried to blend into the background.

The leader of the group, Alice, presented her Persian, a big fluffy monster. “I was powerless before her addiction. I kept her in diamonds. A little choker, a tiara. It got so bad, all she wanted was to watch the Home Shopping Network. But she’s been clean for two years.”

We applauded. What bravery.

A man told a story about his St Bernard who had died in a snowstorm. “A savior complex. He thought he could rescue everyone. But he couldn’t even save himself.” Overcome, he sat down.

A woman had a horse that had been confined too long in its stable and would compulsively masturbate.

I have to look up that one.

By the end of the evening and all the stories, I felt a strange release. I wasn’t alone in this. Addictions are universal, and we all suffer our private grief.

Still, I was going to break my cat’s habit if it killed me.

Unfortunately, it killed him first. The next morning I heard him hacking. Then I heard the thump. By the time I got to him, he was gone. In his fall, he knocked over his whiskey, which the dog promptly lapped up.

I was sad to see him go, but maybe it’s better this way. There’s a small pet cemetery in town. It was a quiet ceremony; no one else came. I wanted time alone with him. Maybe if I had tried harder. Maybe if I had cared a little more.

As if on cue, a little boy and girl approached me. The girl took my hand. “Don’t cry.”

I wasn’t crying.

The little boy asked, “What’s his name?”

“Morph.”

“Like the computer animation?”

“No,” I said, “as in anthropomorphic.”

They didn’t understand and eventually wandered away.

Published on September 23, 2014 10:15

September 12, 2014

Pen or Pencil?

It’s the stereotype that would-be writers ask the world-famous author, “When you write, do you use a pen or a pencil?”

Writers are an insecure lot. We want the magic solution. Do I have the right tools? Am I setting myself up for failure if I don’t follow the exact, same practices as the famous author? Would I be a real writer if I wrote with a quill?

Actually, it’s not a silly question. It’s all about finding what works for you.

I’ve used different methods of writing, and they all have specific benefits and drawbacks.

PENCIL/PEN: Writing longhand is tortuously slow for me, especially for a first draft. I end up spending so focused on picking the right word that I lose the narrative flow. My writing ends up being terse to the point of detachment. But I can imagine that writers who use a pen are like long-distance runners; their brain fall into a steady rhythm that matches the pace of the hand. They are not in a hurry; they can think during the in-between moments of forming the letters.

I use longhand when I’m revising because it forces my brain to slow down and pay attention to the details. I can think about word choice. I feel a physical connection to the text. And sometimes if I don’t feel like rewriting a sentence, that's a sign that it may not be necessary for the story, and out it goes.

The only quirky thing about writing with a pen and a pad of paper is that periodically I want to hit the save button in case the document crashes, and I lose everything.

TYPEWRITER: I still love the sheer energy required to pound out on a keyboard. I wore out six typewriters before moving to computers. My favorites were the manual ones, and my all-time favorite was a cast-iron monstrosity that sounded like the hammers of doom. Hammers of Doom

Hammers of Doom

Given some of my compulsiveness, I felt compelled to fill up a page before I finished a writing session. No leaving the paper on the spool. If I left it there, then the paper would be forever curled and refuse to lie flat. If I took it out then rethreaded it later, I couldn’t get the margins to line up, which mucked with my sensibilities. So finishing a full sheet of paper forced me to keep writing for a certain stretch of time.

Another drawback to leaving the paper in your typewriter is that your witty sister might be inspired to incorporate Barry Manilow into your text.

Not one of my intended characters

Not one of my intended characters

COMPUTER: If writing longhand is distance running, then writing on a computer is a sprint: the fingers working fast enough to keep up with the brain.

Unlike typewriters, computers give you the chance to go back and fix things. You have the freedom to write as much as you want, without worrying about page length (or paper curl). But when I first started using computers, I had trouble not getting into revising mode while writing the first draft. I work best if I write the first draft at a furious, uncensored pace, and then spending time leisurely revising it.

My philosophy: Whatever works best.

Writers are an insecure lot. We want the magic solution. Do I have the right tools? Am I setting myself up for failure if I don’t follow the exact, same practices as the famous author? Would I be a real writer if I wrote with a quill?

Actually, it’s not a silly question. It’s all about finding what works for you.

I’ve used different methods of writing, and they all have specific benefits and drawbacks.

PENCIL/PEN: Writing longhand is tortuously slow for me, especially for a first draft. I end up spending so focused on picking the right word that I lose the narrative flow. My writing ends up being terse to the point of detachment. But I can imagine that writers who use a pen are like long-distance runners; their brain fall into a steady rhythm that matches the pace of the hand. They are not in a hurry; they can think during the in-between moments of forming the letters.

I use longhand when I’m revising because it forces my brain to slow down and pay attention to the details. I can think about word choice. I feel a physical connection to the text. And sometimes if I don’t feel like rewriting a sentence, that's a sign that it may not be necessary for the story, and out it goes.

The only quirky thing about writing with a pen and a pad of paper is that periodically I want to hit the save button in case the document crashes, and I lose everything.

TYPEWRITER: I still love the sheer energy required to pound out on a keyboard. I wore out six typewriters before moving to computers. My favorites were the manual ones, and my all-time favorite was a cast-iron monstrosity that sounded like the hammers of doom.

Hammers of Doom

Hammers of DoomGiven some of my compulsiveness, I felt compelled to fill up a page before I finished a writing session. No leaving the paper on the spool. If I left it there, then the paper would be forever curled and refuse to lie flat. If I took it out then rethreaded it later, I couldn’t get the margins to line up, which mucked with my sensibilities. So finishing a full sheet of paper forced me to keep writing for a certain stretch of time.

Another drawback to leaving the paper in your typewriter is that your witty sister might be inspired to incorporate Barry Manilow into your text.

Not one of my intended characters

Not one of my intended charactersCOMPUTER: If writing longhand is distance running, then writing on a computer is a sprint: the fingers working fast enough to keep up with the brain.

Unlike typewriters, computers give you the chance to go back and fix things. You have the freedom to write as much as you want, without worrying about page length (or paper curl). But when I first started using computers, I had trouble not getting into revising mode while writing the first draft. I work best if I write the first draft at a furious, uncensored pace, and then spending time leisurely revising it.

My philosophy: Whatever works best.

Published on September 12, 2014 08:51

September 9, 2014

Book Review: White Jacket, by Herman Melville

It took me 63 days to finish Herman Melville’s White Jacket. Admittedly, I’m not a fast reader, and I knew I was in for some dense writing. Reading Melville is like eating buckwheat kishka – you’ve got to take it in small bites. There’s a lot of flavor there, and the language takes time to digest.

(Apparently my reading/writing is generating a lot of food metaphors lately. John Gardner is cilantro, Melville is kishka. It won’t be long before I’m ready for some Dickens pound cake.)

In White Jacket, the narrator describes in documentary detail the workings of a man-of-war frigate. With its crew of 500, the vessel Neversink is the world in microcosm. All the various characters, all the types of work, all the stresses and hardship of daily life, with a good dose of cruelty and tyranny thrown in.

“We mortals are all on board a fast-sailing, never-sinking, world-frigate, of which God was the shipwright; and she is but one craft in a Milky-Way fleet, of which God is the Lord High Admiral.”

The most striking section of the book (no pun intended) is the graphic depictions of flogging. Melville criticizes the brutality and the arbitrariness of its use – how a captain can flog any sailor under the Articles of War, and the sailor has no redress. Evidently, White Jacket was instrumental in Congress abolishing the use of flogging in the navy.

The most striking section of the book (no pun intended) is the graphic depictions of flogging. Melville criticizes the brutality and the arbitrariness of its use – how a captain can flog any sailor under the Articles of War, and the sailor has no redress. Evidently, White Jacket was instrumental in Congress abolishing the use of flogging in the navy.

For all his verbosity, Melville does exhibit a Romantic enthusiasm. Modern readers probably have to pay close attention to catch the humor but it is there. For example, he describes Lieutenant Selvagee, a true 19th Century dandy, with his Cologne-water baths and lace-bordered handkerchiefs, who lacks the cojones even to swear effectively: “Selvagee raps out an oath: but the soft bomb stuffed with confectioner’s kisses seems to burst like a crushed rose-bud diffusing its odours.”

Unlike Melville’s next work, Moby-Dick, White Jacketis weighted more in the real world. There are certainly metaphors, similes, themes, and allusions throughout, but it doesn’t have the dense symbolism of Moby-Dick. You get the day-to-day quality of ship life, the tedium and toil, the human tensions:

“At sea, a frigate houses and homes five hundred mortals in a space so contracted that they can hardly so much as move but they touch. Cut off from all those outward passing things which ashore employ the eyes, tongues, and thoughts of landsmen, the inmates of a frigate are thrown upon themselves and each other, and all their ponderings are introspective. A morbidness of mind is often the consequence, especially upon long voyages, accompanied by foul weather, calms, or head-winds.”

Morbidness of mind? Hmmm, that's kind of a precursor to old Ahab.

(Apparently my reading/writing is generating a lot of food metaphors lately. John Gardner is cilantro, Melville is kishka. It won’t be long before I’m ready for some Dickens pound cake.)

In White Jacket, the narrator describes in documentary detail the workings of a man-of-war frigate. With its crew of 500, the vessel Neversink is the world in microcosm. All the various characters, all the types of work, all the stresses and hardship of daily life, with a good dose of cruelty and tyranny thrown in.

“We mortals are all on board a fast-sailing, never-sinking, world-frigate, of which God was the shipwright; and she is but one craft in a Milky-Way fleet, of which God is the Lord High Admiral.”

The most striking section of the book (no pun intended) is the graphic depictions of flogging. Melville criticizes the brutality and the arbitrariness of its use – how a captain can flog any sailor under the Articles of War, and the sailor has no redress. Evidently, White Jacket was instrumental in Congress abolishing the use of flogging in the navy.

The most striking section of the book (no pun intended) is the graphic depictions of flogging. Melville criticizes the brutality and the arbitrariness of its use – how a captain can flog any sailor under the Articles of War, and the sailor has no redress. Evidently, White Jacket was instrumental in Congress abolishing the use of flogging in the navy.For all his verbosity, Melville does exhibit a Romantic enthusiasm. Modern readers probably have to pay close attention to catch the humor but it is there. For example, he describes Lieutenant Selvagee, a true 19th Century dandy, with his Cologne-water baths and lace-bordered handkerchiefs, who lacks the cojones even to swear effectively: “Selvagee raps out an oath: but the soft bomb stuffed with confectioner’s kisses seems to burst like a crushed rose-bud diffusing its odours.”

Unlike Melville’s next work, Moby-Dick, White Jacketis weighted more in the real world. There are certainly metaphors, similes, themes, and allusions throughout, but it doesn’t have the dense symbolism of Moby-Dick. You get the day-to-day quality of ship life, the tedium and toil, the human tensions:

“At sea, a frigate houses and homes five hundred mortals in a space so contracted that they can hardly so much as move but they touch. Cut off from all those outward passing things which ashore employ the eyes, tongues, and thoughts of landsmen, the inmates of a frigate are thrown upon themselves and each other, and all their ponderings are introspective. A morbidness of mind is often the consequence, especially upon long voyages, accompanied by foul weather, calms, or head-winds.”

Morbidness of mind? Hmmm, that's kind of a precursor to old Ahab.

Published on September 09, 2014 08:57

September 5, 2014

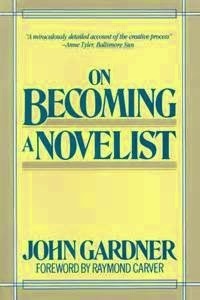

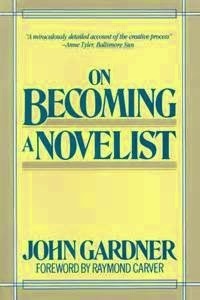

How John Gardner is like cilantro -- Part Two

So, I finished John Gardner’s On Becoming a Novelist, and I’m still having issues. Still think Gardner is a lot like cilantro – either you love him or hate him. For me, I can respect that people love cilantro, but it’s never going to be one of my favorite herbs. So it goes for Gardner.

What I’m struggling with is that Gardner writes eloquently about the art and craft of writing. He captures the complexity of creative imagination – how it can be like capturing lightning in a bottle – while emphasizing that a great deal of hard work is necessary, too. But there’s a critical tone underneath it all. Even when he compliments the work of other writers, nothing ever quite measures up. There’s an ideal that cannot be reached.

I guess I’m feeling intimidated. Which is probably not Gardner’s intention.

Some passages (the use of gendered pronoun aside):

On the creative process: “In his [sic] imagination, he sees made-up people doing things -- see them clearly – and in the act of wondering what they will do next he sees what they will do next, and all this he writes down in the best, most accurate words he can find, understanding even as he writes that he may have to find better words later, and that a change in the words may mean a sharpening or deepening of the vision, the fictive dream or vision becoming more and more lucid, until reality, by comparison seems cold, tedious, and dead.”

On writing and revising: “Fiction does not spring into the world full grown, like Athena. It is the process of writing and rewriting that makes a fiction original and profound. One cannot judge in advance whether or not the idea of the story is worthwhile because until one has finished writing the story one does not know for sure what the idea is; and none cannot judge the style of the story on the basis of a first draft, because in a first draft the style of the finished story does not exist.”

On writer’s block: “If children can build sand castles without getting sandcastle block, and if ministers can pray over the sick without getting holiness block, the writer who enjoys his work and takes measured pride in it should never be troubled by writer’s block. But alas, nothing’s simple. The very qualities that make one a writer in the first place contribute to block: hypersensitivity, stubbornness, insatiability, and so on. Given the general oddity of writers, no wonder there are no sure cures.”

On writer’s block: “Writer’s block comes from the feeling that one is doing the wrong thing or doing the right thing badly.”

Every one of these passages speaks directly to me as a writer. I don’t always understand how I create story but I am endlessly fascinated that I can.

Gardner writes, “We need only to figure out exactly what it is that we’re trying to say – partly by saying it and then by looking it over to see if it says what we really mean – and to keep fiddling with the language until whatever objections we may consider raising seem to fall away.”

That pretty much sums up for me the amazing mystery of the writing process (though E.M. Forster said it more succinctly: “How do I know what I think until I see what I say?”).

What I’m struggling with is that Gardner writes eloquently about the art and craft of writing. He captures the complexity of creative imagination – how it can be like capturing lightning in a bottle – while emphasizing that a great deal of hard work is necessary, too. But there’s a critical tone underneath it all. Even when he compliments the work of other writers, nothing ever quite measures up. There’s an ideal that cannot be reached.

I guess I’m feeling intimidated. Which is probably not Gardner’s intention.

Some passages (the use of gendered pronoun aside):

On the creative process: “In his [sic] imagination, he sees made-up people doing things -- see them clearly – and in the act of wondering what they will do next he sees what they will do next, and all this he writes down in the best, most accurate words he can find, understanding even as he writes that he may have to find better words later, and that a change in the words may mean a sharpening or deepening of the vision, the fictive dream or vision becoming more and more lucid, until reality, by comparison seems cold, tedious, and dead.”

On writing and revising: “Fiction does not spring into the world full grown, like Athena. It is the process of writing and rewriting that makes a fiction original and profound. One cannot judge in advance whether or not the idea of the story is worthwhile because until one has finished writing the story one does not know for sure what the idea is; and none cannot judge the style of the story on the basis of a first draft, because in a first draft the style of the finished story does not exist.”

On writer’s block: “If children can build sand castles without getting sandcastle block, and if ministers can pray over the sick without getting holiness block, the writer who enjoys his work and takes measured pride in it should never be troubled by writer’s block. But alas, nothing’s simple. The very qualities that make one a writer in the first place contribute to block: hypersensitivity, stubbornness, insatiability, and so on. Given the general oddity of writers, no wonder there are no sure cures.”

On writer’s block: “Writer’s block comes from the feeling that one is doing the wrong thing or doing the right thing badly.”

Every one of these passages speaks directly to me as a writer. I don’t always understand how I create story but I am endlessly fascinated that I can.

Gardner writes, “We need only to figure out exactly what it is that we’re trying to say – partly by saying it and then by looking it over to see if it says what we really mean – and to keep fiddling with the language until whatever objections we may consider raising seem to fall away.”

That pretty much sums up for me the amazing mystery of the writing process (though E.M. Forster said it more succinctly: “How do I know what I think until I see what I say?”).

Published on September 05, 2014 08:50

August 29, 2014

Meet Kenny Reston

Kenny Reston turned 41 this year (June 6th – happy belated birthday!). To be honest, he’s surprised he’s made it this far. After a rough childhood and a tumultuous time in college, he was heading down a dangerous path. Alcoholism, failed relationships, amateur porn. It wasn’t looking good.

For years he kept secret how his mother abused him. But secrets have a tendency to leak out around the edges, and no amount of alcohol or sex would cover them up.

Fortunately, eleven years ago he got clean and sober. He dismantled the self-destructive cycle of his earlier life and has built himself a safe cocoon.

Then Eileen Hesperin asked to interview him. She’s an award-winning journalist who was working on a book about sexually-abused boys. Given the wreckage of his past, Kenny proved to be a compelling case study.

Well, Eileen’s book, Come Undone, was an unexpected bestseller. It’s been featured on GMA, local news, and talk radio. Politicians even have waved the book from atop their podiums, denouncing the crime of sexual abuse. The book garnered so much attention that Hollywood got interested.

So it’s no wonder that filmmaker Dilson Fillmore got in touch with Kenny to make a movie about his life. He wants to do something edgy, controversial, in-your-face. He wants to make the audience squirm.

But Kenny’s not sure that he wants his story told that way. Sure, he believes people might find it helpful to hear about his struggles and how he eventually got help. But the movie doesn’t have to be melodramatic. Let’s keep it real and honest, not sensationalistic.

Unfortunately, he’s watching the gap widen between what actually happened and what sells an entertaining movie. It’s hard enough to face the lingering memories of the abuse; now he has to figure out how to reclaim his story.

For years he kept secret how his mother abused him. But secrets have a tendency to leak out around the edges, and no amount of alcohol or sex would cover them up.

Fortunately, eleven years ago he got clean and sober. He dismantled the self-destructive cycle of his earlier life and has built himself a safe cocoon.

Then Eileen Hesperin asked to interview him. She’s an award-winning journalist who was working on a book about sexually-abused boys. Given the wreckage of his past, Kenny proved to be a compelling case study.

Well, Eileen’s book, Come Undone, was an unexpected bestseller. It’s been featured on GMA, local news, and talk radio. Politicians even have waved the book from atop their podiums, denouncing the crime of sexual abuse. The book garnered so much attention that Hollywood got interested.

So it’s no wonder that filmmaker Dilson Fillmore got in touch with Kenny to make a movie about his life. He wants to do something edgy, controversial, in-your-face. He wants to make the audience squirm.

But Kenny’s not sure that he wants his story told that way. Sure, he believes people might find it helpful to hear about his struggles and how he eventually got help. But the movie doesn’t have to be melodramatic. Let’s keep it real and honest, not sensationalistic.

Unfortunately, he’s watching the gap widen between what actually happened and what sells an entertaining movie. It’s hard enough to face the lingering memories of the abuse; now he has to figure out how to reclaim his story.

Published on August 29, 2014 08:30

August 25, 2014

How is John Gardner like cilantro?

I’m about a quarter of the way through John Gardner’s On Becoming a Novelist. Probably about 15-20 years ago, I read other Gardner works: Grendel, Freddie’s Book, and Nickel Mountain, as well as The Art of Fiction.

I confess I’m intimidated by Gardner. I want to like his work more than I do. It’s kind of like my view on The Beatles, Elvis Presley, cilantro, and hoppy beer – I can respect the craft but they’re never going to be my favorites.

The first section of On Becoming a Novelist focuses on “The Writer’s Nature.” Gardner writes about his own experience:

“I worked more hours at my fiction than anyone else I knew, and I was lavishly praised by friends and teachers, even published a little, but I was dissatisfied, and I knew my dissatisfaction was not just churlishness. . . . I had by this time already faced the painful truth every committed young writer must eventually face, that he’s on his own. Teachers and editors may give bits of good advice, but they usually do not care as much as does the writer himself about his future, and they are far from infallible; … But now nothing was clearer than that I must figure out on my own what was wrong with my fiction.”

I can relate. Gardner articulates my own struggles as a writer, and how I have to learn to trust my abilities to develop my craft.

Yet my chief complaint against Gardner is his passionately superior world view about what constitutes true literature. Even as he describes how a writer must figure out her craft on her own, I get the sense Gardner would be hanging in the background, ready to point out where her mistakes are.

Still, I’m appreciating On Becoming a Novelist, and I’m keeping myself open to its lessons. The trick is to take what is useful for me and to disregard Gardner’s critical edge.

I confess I’m intimidated by Gardner. I want to like his work more than I do. It’s kind of like my view on The Beatles, Elvis Presley, cilantro, and hoppy beer – I can respect the craft but they’re never going to be my favorites.

The first section of On Becoming a Novelist focuses on “The Writer’s Nature.” Gardner writes about his own experience:

“I worked more hours at my fiction than anyone else I knew, and I was lavishly praised by friends and teachers, even published a little, but I was dissatisfied, and I knew my dissatisfaction was not just churlishness. . . . I had by this time already faced the painful truth every committed young writer must eventually face, that he’s on his own. Teachers and editors may give bits of good advice, but they usually do not care as much as does the writer himself about his future, and they are far from infallible; … But now nothing was clearer than that I must figure out on my own what was wrong with my fiction.”

I can relate. Gardner articulates my own struggles as a writer, and how I have to learn to trust my abilities to develop my craft.

Yet my chief complaint against Gardner is his passionately superior world view about what constitutes true literature. Even as he describes how a writer must figure out her craft on her own, I get the sense Gardner would be hanging in the background, ready to point out where her mistakes are.

Still, I’m appreciating On Becoming a Novelist, and I’m keeping myself open to its lessons. The trick is to take what is useful for me and to disregard Gardner’s critical edge.

Published on August 25, 2014 08:02

August 5, 2014

Some Thoughts on Kindle Unlimited and Indie Authors, by Mark Coker at Smashwords

Published on August 05, 2014 10:24