Rupert Matthews's Blog, page 12

April 2, 2020

The Black Douglas - key Scottish commander at the Battle of Bannockburn, 1314

The tomb of Sir James Douglas. After his death fighting the Moslems while on Crusade in Spain, Douglas’s bones were packed into a casket and carried back to Scotland by Sir William Keith of Galston, who had missed the fatal battle due to an earlier injury. They were deposited in this tomb in St Bride’s Kirk in Douglas, Lanarkshire, the seat of the Douglas family.

The tomb of Sir James Douglas. After his death fighting the Moslems while on Crusade in Spain, Douglas’s bones were packed into a casket and carried back to Scotland by Sir William Keith of Galston, who had missed the fatal battle due to an earlier injury. They were deposited in this tomb in St Bride’s Kirk in Douglas, Lanarkshire, the seat of the Douglas family. The fourth division of the Scottish army was officially commanded by Walter the Steward, but in reality was led by Sir James Douglas. Walter was the hereditary High Steward of Scotland, an exalted position that made him the king’s representative whenever the king himself was absent. Walter was, however, barely in his teens so Bruce ensured that he had Douglas to keep an eye on things. Sir James Douglas was widely known as Black Douglas due to his mass of unruly black hair and murderous nature. He was 29 or 30 at the time of the battle and a highly experienced commander. In 1304 he had sought an accommodation with Edward I of England, but Edward rebuffed him due to the fact that Douglas’s father, Sir William Douglas, had been the first Scottish knight to back William Wallace. When Robert Bruce claimed the crown in 1306, Douglas hurried to join him and remained loyal ever after. Douglas fought at the Battle of Methven, thereafter taking to guerrilla warfare with skill and passion. His most notorious incident came on Palm Sunday 1307 when he attacked the English garrison of Douglas Castle while they were in church. Dozens were killed in the church, the rest dragged outside to have their heads hacked off. On 19 February 1314 Douglas captured Roxburgh Castle, one of the strongest in Scotland, by a ruse. He had his men dress up as cattle, then move slowly towards the walls after nightfall. Once at the foot of the walls, the men dropped their disguises, threw up ladders and were over the walls in seconds. The garrison was slaughtered and the castle burned. Douglas then received the summons from Bruce to come to Stirling, arriving in time to take part in the Battle of Bannockburn.

You can buy the book HERE

Published on April 02, 2020 09:42

The French attack the Isle of Wight, 1377

The Gatehouse of Carisbrooke Castle

The Gatehouse of Carisbrooke CastleThe French did not go far and next day landed on the Isle of Wight. Tovar had, of course, been here before and knew the lie of the land. He knew that the key to the island was Carisbrooke Castle, and sent a fast-marching column of men to capture the place. The column of men was led by a French knight, possibly the Sir Jean de Raix who had led the landing at Rye. A second column went to Yarmouth and a third to Newtown, then the two biggest towns on the island. The column that reached Carisbrooke found the gates of the castle firmly shut and the commander, Sir Hugh Tyrrel refusing even to discuss terms. The other columns encountered less opposition. Rather than spend time plundering and trying to find hidden treasures, Vienne offered the terrified civilians - who unlike those at Rye had nowhere to run - a deal. If they paid him 1,000 marks he would go away and leave both them and their property intact. A mark was the equivalent of 160 pennies, so at a time when the average workman was paid two pennies a day this was a huge sum of money. Nevertheless the people of the Isle of Wight managed to find the ready cash and handed it over. Instead of leaving, however, Viennes merely settled down to lay siege to Carisbrooke Castle. A siege could be a tedious business, and Vienne had many demands on his time. Not least he had to use his ships to keep control of the Solent to stop any English relief force crossing over. Carisbrooke Castle on the Isle of Wight managed to hold out against the French raiders, but the rest of the island was pillaged and the local authorities were persuaded at swordpoint to pay the raiders a large sum of cash to go away without burning every building to the ground.

On a day when Viennes was absent and another French knight was in charge of the siege, Tyrell decided that the time had come to teach the French a lesson. Keeping his preparations hidden from French view, Tyrell mustered his men for a sally. First local knight Sir Peter de Heyno, who lived at Stenbury, offered to shoot the French commander. He fetched what he called his “silver bow” and stood at an arrowslit until the French knight came within sight. Pulling his bow back to its maximum bend, Heyno let loose. His arrow flew true, struck the French man in the chest and knocked him from his horse. That was the signal Tyrell had been waiting for. The castle gates were thrown open and the English soldiers streamed out. A short, but savage battle followed that saw the besieging French overwhelmed by the sudden onslaught. Tyrell had brought lit torches and kindling with him, so he was quickly able to set fire to the French siege engines and made sure that they were well alight before pulling his men back into the castle. When he heard of the sally, Viennes realised that he was not going to gain much more from the Isle of Wight. Calling Tyrell “a dangerous serpent”, he abandoned the siege and marched his men back on board the ships. It was now 21 August.

From The Battle of Brighton, 1377. Buy the book HERE

Published on April 02, 2020 09:36

The Blackout of 1939-45 - The Background

A poster encouraging people to take care during the Blackout

A poster encouraging people to take care during the BlackoutThe blackout lasted throughout the war, plunging Britain into darkness every night. Lights could not be shown outside at night for any reason at all. Cars drove without headlights, streetlights were switched off and even torches were banned. It made life not only inconvenient, but also dangerous. Several people were run over by cars or bicycles, while others fell down holes or over the edge of bridges that they could not see. The reason for the blackout was the fear of German bomber aircraft. It was known and expected that the bombers would come by night as well as by day. During daylight British anti-aircraft guns and fighters could see the German aircraft to try to shoot them down, but at night the German bombers would be almost impossible to see. They could roam at will over Britain's skies to rain down death and destruction. And the German bombing would be much more accurate and deadly if the German airmen could see what they were aiming at. If the ground was in darkness, aiming would be difficult so the Germans would be able to do less damage.

It was not only bombaiming that the blackout was designed to frustrate. Navigating an aircraft in 1939 was usually a business of following landmarks on the ground: rivers of a particular shape, road junctions, villages with unusual shapes, large buildings standing alone among fields. At night very few of these landmarks would be visible, unless they were lit up. If every house in a village had its lights on, the pilot of an aircraft high above could make out the shape of the village and would know where he was. But if the lights were all out, the pilot would have to rely on less reliable features. Rivers and lakes reflect moonlight, so water features could be used as navigational aids, but these are few and far between. Even worse one river bend can look much like another.

Published on April 02, 2020 09:28

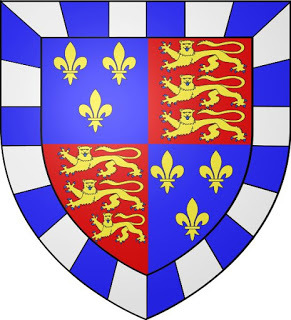

The Lancastrian Commanders at the Battle of Northampton

The Beaufort Coat of Arms

The Beaufort Coat of ArmsThe Lancastrian forces at Northampton were nominally under the command of King Henry VI. Henry had been born the son of King Henry V in 1421, which made him 39 at the time of the battle. He was only nine months old when he inherited the crown of England from his father. He grew up to be a kindly and devout man, but his childish nature and simple mind made him a weak king. Henry slipped into periodic bouts of insanity which made his grip on government even less secure. Henry was no more fit to lead an army than to rule a kingdom, so real command fell to Humphrey Stafford Duke of Buckingham, the most experienced diplomat and commander at the battle. Born in 1402, Buckingham was 58 when he drew up his men outside Northampton. Through his mother, Buckingham was a great grandson of King Edward III, yet another royal relative active in the Wars of the Roses. His father had died when he was barely a year old, leaving him the title of Earl of Stafford and a handsome income of £1260 a year, not bad when the average worker would get a penny a day. He was knighted in 1421 and became a Privy Councillor to the infant Henry VI in 1424. In 1430 he went to Normandy to take part in the fighting against the French and although he did not have an independent command, he did gain valuable experience of the business of war. When his mother died in 1438 he inherited her lands, tripling his income at a stroke, and the title of Earl of Buckingham. He was now one of the richest and most noble men in England. As such he was made a Knight of the Garter and entrusted with a string of diplomatic missions. His military experience was broadened by being made Captain of Calais, effectively commander of the English forces in northern France, as well as Warden of the Cinque Ports (a naval command) and Constable of Dover Castle. When the disputes between Somerset and York broke out in earnest, Buckingham played the role of peace-keeper between his two truculent cousins. By way of family links, Buckingham had a foot in both camps. His daughter was married to Somerset’s son while he himself was married to a cousin of Warwick. Buckingham declared himself to be a firm supporter of Henry VI, and sought constantly to push for good government and impartial justice. He quarrelled constantly with Somerset, but refused to accept the more radical solutions of York. At the Battle of St Albans in 1455 he had commanded King Henry’s bodyguard. He was slightly wounded and captured by the Earl of Warwick. Buckingham continued to try to find common ground between the two sides, expressing shock that the dispute had come to blows and seeking to bring people to their senses. Finally realising that Margaret and York were unwilling to find any sort of compromise deal, Buckingham decided to remain loyal to King Henry, even though that meant siding with Margaret. In October 1459 he led a Lancastrian army to Ludford Bridge in Shropshire, where his friendship with several of the lesser nobles in York’s army persuaded them to change sides or slip away in the night. As a result Buckingham was able to drive York into exile in France almost without striking a blow. He took the Duchess of York and her three youngest children into his own care, being careful not to pass them on to the vengeful Queen Margaret. Henry VI rewarded Buckingham with estates confiscated from those who had gone into exile with York. He was in London through the winter of 1459-60 trying to muster men and money for the cause of King Henry, but finding his efforts largely thwarted by the unpopularity of Queen Margaret. He had nevertheless mustered a reasonably large army by the standards of the day, and marched it north away from pro-York London two or three weeks before Warwick and Edward Earl of March got to the city. Serving under Buckingham was Lord Edmund Grey of Ruthin. By his family links Grey was firmly linked to the Lancastrian cause. By his mother he was a great grandson of John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster, and therefore a cousin to Henry VI. He married Lady Katherine Percy, daughter of Henry Percy, Earl of Northumberland. The Percys had a long running feud with the Nevilles, the family of the Earl of Warwick. However, Grey had got involved in a bitter dispute with Henry Holland, Duke of Exeter and a key supporter of Queen Margaret. Exeter was bad tempered and particularly rapacious when it came to exploiting contacts at court for his own benefit. Exeter had made a bid to seize control of the wealthy manor of Ampthill, Bedfordshire, from Grey on rather dubious grounds and was busily using bribery and pressure to get his way. Nevertheless, Grey had remained a staunch supporter of Buckingham in his efforts to find a compromise peace and to be loyal to the anointed King, Henry VI, come what may. Grey, like Buckingham, had seen extensive service in the French wars. He had fought in the Aquitaine campaigns of 1438-40 and been knighted as a consequence. He sat on the Council of Regency from 1456 to 1458 and was notable for his refusal to get dragged into supporting either York or Queen Margaret. At the time of the Battle of Northampton he was 44 years old.

You can buy the book HERE

Published on April 02, 2020 09:21

The Aftermath of the Siege of Newark

Newark Castle

Newark CastleWhen the various armies packed up and marched away from Newark in May 1646 they left Newark in a mess. Many houses and other buildings in the town had been damaged or destroyed by artillery and mortar fire - the scars of cannon balls can still be seen on the castle walls. The Muskham Bridge had been destroyed along with Winthorp Church and dozens of outlying houses and farms. The River Trent was in even worse condition. It was blocked in several places by the fallen Muskham Bridge, the Parliamentarian dam and the banks were strewn with sharpened stakes. All this had to be repaired and cleared before life returned to normal for Newark. For many, of course, life could not return to normal. Hundreds of people had died from battle or disease, and the deaths continued for hunger had weakened the old and young so that they fell victim to diseases they might otherwise have survived. Nor was the material damage to the town over. In 1648 the Parliamentarian army returned to blow up sections of the castle and reduce it to ruin so that it could never again be used to defy them. The economy of the town was also devastated. Unable to export their yarn and cloth, the merchants had gone bankrupt, and those who survived found that their overseas customers had turned elsewhere for supplies. Money to repair the damage was hard to come by. It would take years for Newark to regain its prosperity and its population. Some marks of the siege still remain. The castle ruins still stand on the banks of the Trent. After generations of neglect they were restored in the 1840s. The grounds are now public gardens and a museum and a local history museum stands in the ruins. If Newark took time to recover from the fighting, at least it did recover. King Charles did not. Although he had come to a deal with his Scottish subjects and was in the process of negotiating a peace with the English Parliament, he decided to start a new Civil War in the spring of 1648. That war was over quickly, having achieved nothing but the deaths of many brave men in a lost cause. Parliament then began a debate on how to deal with a king who, quite clearly, could not be trusted. The Parliamentarian army had no doubt about what Charles deserved. Led by Cromwell the army marched into London, threw out of Parliament any MP they did not trust and put Charles on trial for treason. The verdict was a foregone conclusion. Charles was beheaded on a scaffold erected in Whitehall on 30 January 1649. Thereafter England was ruled by the Parliamentarian army, which in effect meant by Oliver Cromwell. After Cromwell’s death Charles II returned to the throne having reached an agreement with Parliament that settled many of the issues over which the Civil War had been fought.

You can buy the book HERE

Published on April 02, 2020 09:17

The Armies deploy for the Battle of Losecoat Field

A handgunner at Losecoat Field

A handgunner at Losecoat FieldIt was probably just north of Tickencote Laund that Edward arrayed his army for battle. This was just over half a mile south of Welles’s position and on a fairly large area of flat land halfway up the long slope that led from Great Casterton to the ridge where Welles was. He would have been out of bowshot range, but within sight. And he wanted Sir Robert Welles to see what was going to happen next. At the time nobody recorded how big Edward’s army was on the day of the Battle of Losecoat Field. It is known that Edward had fewer men than did Sir Robert Welles, but since we cannot be certain how many men Welles had that does not help much. We know that a large part of his cavalry were off looking for the rebels near Melton Mowbray, but even so Edward had considerably more horsemen than did the rebels. Most of these men will have been hobilars, but there would probably have been a small number of more heavily armoured men. Edward’s infantry at this battle would have comprised his own personal retainers, plus those of Arundel, Hastings and the other noblemen present. These retainers were professional soldiers and while we don’t know how many of them were present they would have been considered the heart of the royal army. Edward also had a fair number of militia men with him. He had called out several county militia and ordered them to meet him on the road north from London. Ordinarily these commissions of array would have raised as many as 15,000 men, but given the speed with which Edward was marching it is unlikely that more than a fraction of this number appeared in time. Certainly some units were still marching north up the Great North Road hoping to catch up with Edward while the battle was taking place. Where Edward undoubtedly had an advantage was in artillery. He had the royal artillery train, the rebels had no cannon at all. This may not have been as great an advantage as it might appear to modern readers since late 15th century artillery was unreliable, inaccurate and of shorter range than is often realised. Nevertheless these guns could fire cannonballs at least as far as a longbow could shoot while the noise, fire and smoke they produced were very impressive to men unaccustomed to them. Nor should the effect on morale of an incoming cannonball be dismissed. A sword could slice a man’s head off, an arrow could pierce him from front to back, but only a cannonball could reduce him in an instant to such a mess of bloody pulp that it was impossible to see where his head, torso or arms had been. Seeing one’s comrades destroyed in such grisly fashion was a massive blow to medieval morale. But before battle could be joined, Edward had a task to perform. Lord Welles and Sir Thomas Dymmock were brought forward to stand in front of his army, facing toward the rebel force. Sir Robert Welles and Sir Richard Warren could be seen watching. Edward reminded Welles and Dymmock that in London in February he had generously granted them pardons for their actions over the winter. But that they had repaid him by helping to organise the uprising that now saw the men of Lincolnshire arrayed for battle on the ridge of Tickencote. He declared that he had told Sir Robert Welles that his father would be held responsible if the uprising did not disband at once. It had not disbanded, and so Lord Welles was as guilty of treason as was his son. Thereupon Edward ordered that the heads of Wells and Dymmock be sliced off. A burly retainer stepped forward and did the deed. The severed heads of the two men were picked up by their hair and displayed first to Edward’s army and then to the rebels.

You can buy the book HERE

Published on April 02, 2020 09:13

Introduction to the Battle of Lincoln

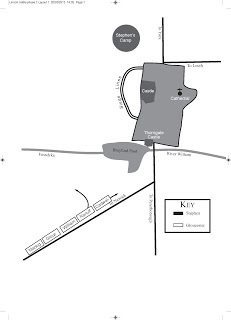

The opening moves of the Battle of Lincoln

The opening moves of the Battle of LincolnThe Battle of Lincoln seemed to be a turning point in the civil war that had broken out in England in 1135. For more than a year the two main rival armies had been moving around England, both looking for a weakness in the other, but neither willing to strike. All that ended at Lincoln in February 1141 when Earl Robert of Gloucester caught King Stephen at a disadvantage and launched an assault that he hoped would end the war in a single blow. The battle that followed is one of the best recorded conflicts of its age. Unlike most medieval battles, the Battle of Lincoln was recorded by a chronicler who spoke to men who had been there and who were able to describe who had done what and why. The battle belies the usual image of medieval battles as a vicious free for all and instead shows just how subtle and sophisticated the tactics and strategems could be. With its violence, fury and drama, the Battle of Lincoln was one of the most decisive battles of medieval England. It is not often that a king is captured by his rival for the throne, still less is he wrestled to the ground while hacking at his enemies with a two-handed sword able to slice a man in half. The capture of King Stephen gave his rival Empress Matilda a crucial advantage when it came to securing the throne of England. That she was not able to do so was as much her own fault as it was anyone else’s. The battle was fought to the west of the old city walls, overlooking the Fossdyke and what is now the old racecourse. Part of the battlefield was built over in the 19th century, with roads such as Cambridge Avenue, York Avenue and Richmond Road covering the most likely site of King Stephen’s original position. But other parts of the battlefield, west of Rosebery Avenue are little different from how they were back in 1141 when a king came to Lincoln and nearly lost his crown. This book seeks to explain why the Battle of Lincoln was fought, how it was fought and what its results turned out to be. So read on and learn how history was made in Lincoln.

You can buy the book HERE

Published on April 02, 2020 09:07

March 28, 2020

The German Ultimatum to Denmark, 9 April 1940

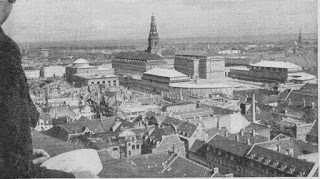

Copenhagen on the eve of war

Copenhagen on the eve of warThen, at 4am on 9 April the German ambassador in Denmark Cecil von Renthe-Fink phoned the Danish foreign minister Peter Munch and demanded an immediate meeting. Twenty minutes later von Renthe-Fink was being shown into Munch's house. He handed to the worried Munch a note that had been sent to the German embassy by radio a couple of hours earlier and was signed by German Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop. The note read:"The Government of the Reich is in possession of documents that prove that Britain and France intend to occupy certain districts of the Scandinavian States within the next few days. The Scandinavian States have not only offered no resistance to these activities but have allowed measures to be taken without taking any appropriate counter measures. But even if the Danish Government would adopt counter measures, the Government of the Reich is well aware that he Danish forces are not adequate to furnish resistance in the event of a Franco-British invasion. "In this decisive phase the German Government cannot passively sit back and watch how the Western Powers would turn the Scandinavian States into a theatre of war against Germany. The German Government is not willing to put up with this situation. The German Government has therefore given orders to begin certain operations which will lead to the occupation of certain points of strategic importance on Danish territory."The German Government hereby undertakes the protection of Denmark for the duration of the war. The Government of the Reich is, moreover, determined from now on to defend Denmark with all adequate measures against French and British attacks. "The protection by the German forces is the only conceivable security for the Scandinavian States for the defence of their territories, so that these territories may not become theatres of war and the arena of the most terrible operations in the present war. "The Government of the Reich expect the Danish Government and the Danish people to understand the German procedure and expect them not to offer any resistance. Any resistance that might be made will be broken and must be broken by all means, and such resistance would therefore only lead to needless bloodshed. "In view of the traditional good relationships between Germany and Denmark the German Government assure the Danish Government that Germany does not intend by these measures to destroy Denmark's territorial integrity and independence either at the present moment or in the future". The reason for the rather convoluted statement was that Hitler was desperately worried about the impact the German invasion might have on neutral countries such as Romania, Bulgaria, Hungary and especially the USA. He needed to have not only a pretext for the invasion but a reason for acting that would not breach the non-aggression pact signed only 10 months earlier. By claiming to be coming to the defence of Denmark Hitler could march his troops in to occupy the kingdom without declaring war and, in strictly pedantic terms at least, without breaching the non-aggression pact. For these obviously hollow claims to have even a mask of truth about them it was important that the Danes not fight back - hence the emphasis on avoiding bloodshed. The meeting between von Renthe-Fink and Munch ended at 4.35am. Munch had already phoned his king and prime minister to alert them to the meeting and he at once phoned both to tell them what the note read. Stauning at once called General Prior, also already alerted, to tell him that a German invasion was imminent. It was 4.45am. The Germans were already on the march.The German invasion of Denmark had begun.

Published on March 28, 2020 09:49

March 23, 2020

Meeting Salvador Dali

A bit of background: when my mother met Salvador Dali she was working from home for a children's comic. She wrote scripts for stories about teddy bears and bunny rabbits, and made a very good living at it too. I was aged two when this incident happened.

Salvador Dali was then a famous, notorious, fashionable Spanish artist. He enjoyed great international success and had the reputation of being eccentric if not completely crazy.

Articles by famous columnists who had met him - reminiscences by old acquaintances - all appeared in the magazines and newspapers, saying how weird he was and how crazily he behaved. Dali himself encouraged all this by posing for photographs with bulging, staring eyes, twirling moustaches and outlandish clothes.

Well for the record we met him round about 1963 and he was one of the sanest people I ever encountered.

We were on holiday in Spain at Rosas on the Costa Brava. I believe Rosas is now a built up, huge holiday resort. When we were there it was still a small fishing village, as were most of the surrounding villages. We were there because a friend of ours, the writer Hank Jansen (Steve Francis) who wrote what were for those days rather daring Westerns, was living out there with his Spanish wife and child (later two children).

Incidentally although Steve made a good living from writing stories about the western United States, he had never been there. Travel was much less usual in those days. My husband who had been to the States told Steve that he absolutely must go there as he was making background mistakes in his writing. But Steve would not hear of it. He said none of his readers had ever been Out West, so they would not know whether he was making mistakes or not. How times have changed. A writer could not get away with that now.

We were staying in a rented flat next to the flat where Steve and his family lived. Steve missed the company of English people and prevailed upon anyone and everyone he could to join him in Spain for their holidays. I think his Spanish wife, an extremely intelligent, nice person and far too good for Steve, found all these summer throngs of foreigners something of a trial - but life is imperfect.

Unknown to us until we got there, a few miles along the coast at a place called Cadaques was living Salvador Dali. This was his family home. He was related to quite a few of the local people. They of course had known him since childhood. A fishing friend of Steve’s, a local builder, was some sort of cousin to Dali - second cousin twice removed - or whatever.

When this cousin learned from Steve that this latest English visitor in the flat next door was a director of an English publishing house and his wife was a scriptwriter, the cousin knew at once that Dali would be interested. He was quite a humble relative of the great man who had made good and he thought he could earn some merit points by making an introduction.

We were very surprised when Steve told us that Salvador Dali had invited us to his home in Cadaques to have tea and or a drink one afternoon. I felt slightly embarrassed. I had five year old and two year old children with me and I would not leave them to be minded by strangers in a foreign country. I suggested that Dali must have meant the invitation for my husband, not the whole family. I would not be the least offended if we had to stay behind. But the invitation came back that we were all invited and on the due day off we went.

Cadaques was then a small village and I remember lots of swans on a sheltered inlet from the sea. This was the first time I had ever seen swans on seawater.

Up on the cliffs overlooking the sea was Dali’s home. He had made it by having several tiny fisherman’s cottages knocked into one dwelling. It was painted completely white and sprawled along the clifftop in a series of small rooms. Dali very proudly showed me and the two children round the ‘garden’ which was a series of ins and outs of little courtyards and sitting areas, all completely paved and also white painted. He showed us where he had had small pieces of mirror embedded into the walls here and there to reflect the glinting of the sun as it moved across the sky.

This was clearly his real home where he relaxed and worked. His apartment in (was it in Madrid or Barcelona? I can’t remember.) was clearly where he put on all the crazy acting to get himself into the magazines.

We had gone on the visit with Steve Francis and the cousin who had arranged the meeting. Dali met us at the door looking quiet and businesslike and in normal correct clothes for a well-heeled Spaniard on a hot day in his own home - a quiet shirt, well cut trousers and lightweight shoes. There was not the slightest sign of craziness.

His wife did not join us. The cousin had told us that she would not put in an appearance. She never put in an appearance. No one ever saw her. Sometimes they wondered if she existed.

My recollection, although it is all a long while ago, is that Dali did not speak English well and that Steve was translating much of the time. The cousin sat not saying a word, but swelling with pride at being in the good books of his famous relative.

Dali had welcomed us all into one of the rooms of the cottage. He gave us refreshments and was friendly with the children, who as always on these occasions were quiet and well behaved [That means me - ed.].

Of course Dali had not the slightest interest in us, although he went through the usual conversational pleasantries. He wanted to talk to my husband about getting an interview in one of the women’s magazines of the publishing house of which my husband was a director. There were several weekly and monthly magazines with circulations of millions in the group. The women’s magazines had women editors and a woman director on the board. These women knew their jobs inside out and were fearsome dragons. The men directors were terrified of them. My husband noted down the details of what sort of interview Dali would like and when and where he could be available. When we got back to England he crept humbly into the presence of the great ladies and told them all about it. What happened I never followed up. I was too busy scriptwriting and looking after my family to have time for anything else. Those years of my life went by in a blur of work. I can hardly remember the passing of the days. Only those writing to their full capacity to weekly production can understand the pressure

One thing sticks in my memory about the visit to Dali. Some of his pictures were painted on truly huge canvases and on our little walk round with the children he showed me how he did it.

In one of the rooms was a long slot in the floor. It was about a foot wide and ten - fifteen feet long. I can’t really remember, but it was long. Sticking a few feet up through the slot was the top of a huge unpainted canvas. At the side was a wheel and pulley. The slot went way down into the floor - at least into the room below and probably into the room below that. (Remember the cottages were built on the steep side of a cliff.). Dali showed me that he could wind the canvas up and down so that he could reach any part of it and work comfortably in close up. If he wanted to paint anything at the foot of the canvas he would wind it right up and then stand or sit to work. If he wanted to paint at the top he would wind it right down. This room had a high enough ceiling so that he could wind the whole canvas up into the room when necessary to get a general view. He was obviously pleased with his practical gimmick.

So the visit came to an end and we went back to Rosas.I think everyone was satisfied. We were happy at unexpectedly meeting a great man and Steve and the cousin were glowing with the virtue of a good deed done to all.

But of the crazy man I still read reminiscences about there was no sign. Dali was a sane, courteous business man, living in a modestly sized home in the area where he had grown up and his family still lived.

Published on March 23, 2020 03:21

January 28, 2020

The Kingdom of Kent throws off Mercian overlordship AD775

In 764 King Eanmund of Kent died and was replaced by two joint kings: Heabert and Egbert II.Offa himself travelled down to Canterbury in 764 to attend the coronations. The method by which the people of Kent chose a new king is not entirely clear, but it seems to have been the nobles who had the right to appoint a new ruler, though they had to choose an adult man from among the ranks of the ruling dynasty, the Eskings. Kent had seen joint kings before, there being a long standing division between east Kent and west Kent, with the River Medway marking the boundary. Usually one of the joint kings was the acknowledged senior with the junior ruler concentrating on his own lands and steering clear of international or church matters. A coin of Offa showing him in armour, but bareheaded. The inscription describes him as "Rex Mercior" or King of Mercia.

There is some evidence that it was Offa who had chosen the new joint kings. It may be that he came to Kent not to attend the celebrations but to ensure that his placemen got chosen.While he was there, Offa chose to demonstrate his overlordship of Kent in a very solid fashion. King Heabert granted some land to the Bishop of Rochester. It was usual when this happened for the title deeds, or charter, to be signed by the ruling King and witnessed by whichever nobles and clerics were around at the time and had learned to read and write well enough to sign their names and, hopefully, have read the charter. This particular charter, however, was signed not by Heabert, but by Offa. Heabert signed as a mere witness among others though he did describe himself as King of Kent when he did so. One name noticeably absent was that of the new King Egbert II.When Egbert did choose to act he did so on his own account. Some months after Offa had gone back to Mercia, Egbert chose to have a charter confirmed by King Heabert, implying that it was Heabert who was the senior ruler. Offa's name is nowhere to be seen. One name that does appear as a witness is that of Jaenbert, Abbot of St Augustine's Abbey in Canterbury. The following year Bregowine, Archbishop of Canterbury, died and Jaenbert was elected to succeed him. A few months later Heabert died and Egbert II became sole King of Kent.All appeared calm, with Offa clearly having the upper hand over Kent. But ten years later he overstepped the mark. In 774 Offa called a meeting of Mercian churchmen and Archbishop Jaenbert went along to officiate as was his right. Travelling with Jaenbert was a nobleman named Baban, who may have been acting as observer for Egbert II or who may have been there on his own business.At the meeting Offa decided to give some land he owned to the Archbishopric of Canterbury. Jaenbert was, naturally, pleased but Baban was not. Although the land belonged to Offa the taxes on it were owed to Egbert II and so Offa should have asked Egbert for permission to transfer the land. He did not, he simply signed the charter and when Baban objected told him that Egbert would have to accept the situation.When the news reached Egbert he was predictably furious. Offa had acted as if he, not Egbert, were King of Kent. Having an overlord living miles away in Mercia was one thing. Having an overlord who issued orders to you, expected to have them obeyed and then insulted your dignity was something quite different.It was not only Egbert who was enraged, the Kentish nobles were incensed as well. Egbert was from their own royal family, was related to many of them and had been chosen by them. Offa was a foreigner with no links to Kent at all. While they could expect to have some influence over a local king, they could have none over Offa. Jaenbert was also unimpressed. It suited the Archbishops of Canterbury to be ruled by a local king who could be influenced by them rather than to have a powerful but remote monarch.In 775 Egbert threw off Offa's overlordship. He began ruling in his own right, making no reference to Offa and not seeking to have new laws or taxes approved by his supposed overlord. In his turn Offa could not afford to let this rebellion, as he saw it, go unpunished. He gathered an army and in 776 sent it south to invade Kent.

<!-- /* Font Definitions */ @font-face {font-family:"Cambria Math"; panose-1:2 4 5 3 5 4 6 3 2 4; mso-font-charset:0; mso-generic-font-family:auto; mso-font-pitch:variable; mso-font-signature:-536870145 1107305727 0 0 415 0;} @font-face {font-family:Cambria; panose-1:2 4 5 3 5 4 6 3 2 4; mso-font-charset:0; mso-generic-font-family:auto; mso-font-pitch:variable; mso-font-signature:-536870145 1073743103 0 0 415 0;} @font-face {font-family:"MS Mincho"; mso-font-alt:"MS 明朝"; mso-font-charset:128; mso-generic-font-family:modern; mso-font-pitch:fixed; mso-font-signature:-536870145 1791491579 18 0 131231 0;} /* Style Definitions */ p.MsoNormal, li.MsoNormal, div.MsoNormal {mso-style-unhide:no; mso-style-qformat:yes; mso-style-parent:""; margin-top:0cm; margin-right:0cm; margin-bottom:6.0pt; margin-left:0cm; mso-pagination:widow-orphan; font-size:12.0pt; font-family:"Times New Roman"; mso-fareast-font-family:"MS Mincho"; mso-ansi-language:EN-US; mso-fareast-language:JA;} p.Style1, li.Style1, div.Style1 {mso-style-name:Style1; mso-style-unhide:no; mso-style-qformat:yes; margin-top:0cm; margin-right:0cm; margin-bottom:6.0pt; margin-left:0cm; mso-pagination:widow-orphan; font-size:12.0pt; font-family:"Times New Roman"; mso-fareast-font-family:"MS Mincho"; mso-ansi-language:EN-US; mso-fareast-language:JA;} .MsoChpDefault {mso-style-type:export-only; mso-default-props:yes; font-size:10.0pt; mso-ansi-font-size:10.0pt; mso-bidi-font-size:10.0pt; font-family:Cambria; mso-ascii-font-family:Cambria; mso-fareast-font-family:"MS Mincho"; mso-hansi-font-family:Cambria;}size:612.0pt 792.0pt; margin:72.0pt 90.0pt 72.0pt 90.0pt; mso-header-margin:36.0pt; mso-footer-margin:36.0pt; mso-paper-source:0;} div.WordSection1 {page:WordSection1;}</style><br /><img src="http://feeds.feedburner.com/~r/blogsp..." height="1" width="1" alt=""/>

Published on January 28, 2020 03:49