David Price's Blog, page 3

February 9, 2016

Teach To The Point Of Tears

As most who follow this blog know, I faced some pretty serious health issues towards the end of last year. That I came through it, when statistically it was a coin-flip, was down to luck and the superb intensive care I received. Coming out the other side, however, I was determined to make the most of whatever time I’m allowed. I’d been thinking a lot about this over the New Year period when a wise Irish friend, Colman Farrell, quoted Camus at me: ‘Live to the point of tears’, he urged me. And there it was, my New Year’s resolution – and new life’s plan – more eloquently stated than I could ever manage.

towards the end of last year. That I came through it, when statistically it was a coin-flip, was down to luck and the superb intensive care I received. Coming out the other side, however, I was determined to make the most of whatever time I’m allowed. I’d been thinking a lot about this over the New Year period when a wise Irish friend, Colman Farrell, quoted Camus at me: ‘Live to the point of tears’, he urged me. And there it was, my New Year’s resolution – and new life’s plan – more eloquently stated than I could ever manage.

Well, I’ve been doing pretty well on that front. Part of this year is dedicated to thanking family and friends who rallied round when I needed them most, and my first thank-you trip was combined with leading a study group of Australian educators to schools in Southern California. Lots of raised glasses, toasts, and not a few tears were shed.

But what we saw, in the schools visited, was an extension of that philosophy: ‘Teach to the point of tears’. I’ve never been to the High Tech High schools in San Diego County without being powerfully moved by the articulacy, confidence and optimism displayed by the student ambassadors, who lead visitors tours there. Of all the amazing students I’ve met at High Tech High, however, I’m not sure I’ve ever met one like the 6th grade student who showed us around the High Tech High Chula Vista campus. Her name – and I’m not making this up – is Life California. With a name like that, she clearly is destined to do great things, and I’m absolutely sure she will (one of her many stated career ambitions was to be President – if you met her you’d see that is eminently possible). Life told us about how the relationship between teachers and students is deep and special at her school – their is a mutual trust there which is astonishing to see. And there needs to be, because students at High Tech High are constantly encouraged to reflect on their growth, as learners, and as human beings too. They do this publicly, through the presentations of learning, as well as in peer groups in their student advisories.

When this abundantly confident little girl told us how the learning environment had allowed her to overcome her initial shyness, I looked around at our tour group – we were all discreetly wiping away tears. Much has been written about the project-based learning philosophy that drives the learning at HTH, but less is heard of the relationships and the culture of the place. The desire to have students and teachers work on often very emotive subjects – trans-gender issues, migration (Chula Vista is right on the Mexican border), adolescent anxieties, all were being discussed as we toured – means that students, and staff, are often teaching and learning to the point of tears. Such willingness to open up, breeds an emotional intelligence in HTH students that other schools can only dream about. Life (the person, not the thing) is by no means exceptional. The recently released film, ‘Most Likely To Succeed” (more of which in subsequent blogs) shows several students making huge growth in their emotional development – I guarantee you’ll cry too, when you see it.

To visitors from Australia and Britain – we’re often portrayed as ‘blokey’ or ‘buttoned-up’ – all this open emotion comes as a bit of a shock to the system. We’re at the point in the UK where fear of litigation means that violin teachers are wary of touching students when working on hand positioning, and we steer well clear of the ‘L’ word. But I’m not advocating pedagogical lachrymosity on some touchy-feely-let-it-go basis. Students might have home backgrounds where the development of emotional intelligence isn’t fostered, or they’ve not been encouraged to investigate difficult social issues. But the biggest reason for teaching to the point of tears is that learning that has deep, emotive roots is simply more likely to stick.

We asked Life California how she saw her future: I wished we’d recorded it. She gave the most eloquent analysis of the future of work, including the impact of automation, globalisation, and the need to create your own ‘job’ (remember, this is a 6th grade student). She saw this as a challenge which her peers would rise to, because her school was helping them develop presentation skills, adaptability, team-working and flexibility. She didn’t mention her grade-point average once.

And so we ended the trip at the incredible New Roads school in Santa Monica. This is an independent school with a strong ethic of equity – approximately 40% of students have their fees waived. Though there’s a wide social mix it’s impossible to tell which kids are from wealthy families and which are less privileged. As they’ve reached their 20th birthday, their philosophy has been refined:

“New Roads School seeks to promote personal, social, political and moral understanding, and to instil in young people a respect for the humanity and ecology of the earth and the sensitivity to appreciate life’s deep joys and mysteries….We understand that there are many kinds of intelligence. As such, our programs assist young people in developing and appreciating cognition, intuition, imagination, artistic creativity, physical expression and performance, sensitivity to others, self-understanding, and personal well-being. To neglect any of these areas is to limit students in the development of their full human potential.”

That’s about as far away from the bland school mission statement, as is possible to get. And in every classroom we visited this philosophy was self-evident. Students were not just expected to work hard academically, they were encouraged to find their true selves. The money hasn’t gone into plush accommodation (although Steven Spielberg, who sent his kids there, has donated a lovely theatre) – it’s gone into creating a rich, socially diverse learning community who are loving appreciating life’s deep joys and mysteries.

The tour finished with a student-devised dance performance, based upon the ‘I Am Malala’ book. The audience were segregated, in an attempt to recreate the gender inequality that Malala experienced. The dance was powerfully and professionally executed. But the clincher came at the end, when each performer went into the audience and brought on stage a teacher, as a gesture of thanks and appreciation. Their evident love of learning was tempered by the knowledge that many children around the world are not able to access even basic education, and their good fortune was celebrated with a spontaneous hip-hop stage invasion. There was, literally, not a dry eye in the house. One student , genuinely perplexed, said “I’ve never cried at a performance before, and I don’t know why I’m crying now, but that was amazing”. A teacher, deeply moved, said: “We are so lucky to be able to come to a school like this, when others are denied education”.

It’s easy to be cynical about such expressions of almost stereotypical Californian sentiment, but ask yourself, what is school for? Is it about processing students to achieve a certification which has increasingly less validity, or is it about them finding out who they are, who they want to be, and finding their ‘element’? Because if it’s the latter then we, as educators, shouldn’t be afraid to share our own passions, foibles, insecurities, uncertainties and, yes, our emotions. In 20 years time, those kids will never remember a single worksheet they filled in. But they’ll always remember Malala, and that dance performance, and the teacher who taught to the point of tears.

It’s easy to be cynical about such expressions of almost stereotypical Californian sentiment, but ask yourself, what is school for? Is it about processing students to achieve a certification which has increasingly less validity, or is it about them finding out who they are, who they want to be, and finding their ‘element’? Because if it’s the latter then we, as educators, shouldn’t be afraid to share our own passions, foibles, insecurities, uncertainties and, yes, our emotions. In 20 years time, those kids will never remember a single worksheet they filled in. But they’ll always remember Malala, and that dance performance, and the teacher who taught to the point of tears.

November 7, 2015

We Need Some New Ideas On Tackling Classroom Behaviour

Here’s a quote from the English Secretary of State for Education:

Here’s a quote from the English Secretary of State for Education:

“If some pupils behave badly they can harm education for other pupils…We need to tackle the roots of bad behaviour….This package of measures will support local education authorities and schools who face the toughest challenges. In return for our investment we must ensure that bad behaviour is tackled head on”

The reference to supporting local education authorities probably tipped you off – this isn’t Nicky Morgan speaking. In fact it was Estelle Morris, speaking in 2002. In 2005 Secretary of State, Ruth Kelly (wow, remember her?) announced a range of measures to deal with disruptive kids ‘who stop other children learning’. However earlier this year Nicky Morgan, the current Secretary of State did announce her own plans to tackle low-level disruptive behaviour such as ‘passing notes and swinging on chairs’. To help her initiative, Ms Morgan appointed ex-teacher Tom Bennett as ‘behaviour tzar’.

If you search the terms ‘government cracks down on bad behaviour in schools’ you’ll find many examples of new strategies being announced – if you did a microfiche search in a public library, no doubt you’d unearth concerns about bad behaviour in the 19th and 20th centuries.

This prompts the question: if government crackdowns on bad behaviour in schools worked, why are we still having to do it? From my own observations, I actually think kids are as well behaved in schools as I can recall – certainly much better behaved than my schoolmates at a catholic grammar school in the 1970s. But it always looks good when a government gets tough with little oiks, so the (metaphorical) beatings will continue until behaviour improves….

And those school leaders who really want to get tough now have official approval. Never mind swinging on chairs, a school made the news this week for forcing kids to adopt the ‘university walk’ – hands clasped behind the back. I don’t know which university students actually adopt this gait – I went to a polytechnic – but it hasn’t dissuaded the headteacher from declaring that ’It was introduced to strengthen pupil safety, further raise the aspirations of pupils and to maximise learning time. Staff report that they appreciate the impact it has had on learning time and pupils continue to be very happy and excited about learning.’ Quite how walking like Prince Charles maximises learning time, or makes kids excited about learning isn’t clear, but pupils are excited enough for their parents to launch a petition to get the walk stopped, so who knows?

A student at a primary school in Darwen made the news recently when she was made to scrub the pavements, as a punishment for laughing in class. The student’s mother claims that when she complained about the Dickensian nature of the punishment, a teacher told her ‘That’s just what we do now”.

Clearly, we need some new ideas around here. Step forward the aforementioned Tom Bennett, who has been tasked with making recommendations for improving behaviour management in newly-qualified teachers.. Tom was widely reported as having worked as a nightclub bouncer, though he actually managed a nightclub and helped out occasionally on the door. Either way, he knows a thing or two about unruly behaviour. Similarly, before I taught, I worked as an entertainer in piano bars in Ibiza. Learning to keep a lid on 200 drunken Brits, hell bent on trouble, is quite instructive. So I agree with Tom when says that teachers should ‘help kids as early as possible to self-manage their behaviour, to learn good things like self-restraint and civil discourse’. This seems to me to mark an important distinction between what governments have repeatedly asked teachers to do, and how we might tackle this differently. Cracking-down on discipline has typically meant that the teacher determines what is/is not acceptable; the teacher determines an appropriate punishment; the teacher administers said punishment on an escalating scale, ultimately leading to exclusion.

Helping kids self-manage their behaviour isn’t some wooly liberal latitude – it’s increasingly seen as a sustainable strategy. Indeed a special school in Birkenhead, Kilgarth School, has gone one step further: it’s banned ‘punishment’. This school has some of the most challenging behaviour to deal with, yet is rated ‘outstanding’ by OFSTED. It concluded that the problem with punishment is that it provided no motivation to improve. The school is being advised by Goldsmith’s psychologist Dr Alice Jones who argues that difficult kids fail to make the association between bad behaviour and adverse outcomes, and don’t respond well to the staple punishment – detention: ‘Once you’ve found yourself at half past nine in the morning and you’re already in detention, where’s your impetus to conform for the rest of the day? It’s already gone.’

The school is instead adopting a strategy which would probably appall Carol Dweck – praising, and rewarding, responsible behaviour. They’re not alone.

In the US, a growing number of schools are following the methods, known as Collaborative and Proactive Solutions, designed by Dr Ross Greene. The essence of CPS (a brief description is here) is that we’ve mistakenly attempted to solve behavioural problems, unilaterally, through the imposition of ‘adult will’. Like government crack-downs, it hasn’t worked. Dr Greene instead proposes a Plan B: teachers work with kids to find changes that are both realistic and mutually satisfactory. Students take responsibility for changes which work for adults and themselves.

This non-punitive, non-adversarial, collaborative model is having a real impact in schools in the US, and CPS has a great website, packed with resources for educators: www.livesinthebalance.org. Schools adopting CPS are achieving remarkable reductions in detentions, suspensions and exclusions.

Why do we need to find some new approaches to handling behaviour in the classroom? Because it’s a relatively small step from school exclusion to the criminal justice system. The MotherJones website recently reported that ’a 2011 study that tracked nearly 1 million schoolchildren over six years… found that kids suspended or expelled for minor offences—from small-time scuffles to using phones ….were three times as likely as their peers to have contact with the juvenile justice system within a year of the punishment.’

In other words, cracking down on bad behaviour in school might be in the interests of the well-behaved students who want to learn, but we’re only just storing up problems that we’ll have to deal with further down the line. And the historically adversarial nature of behaviour management inevitably leads to the increasingly strident imposition of adult will, seen at its grotesque conclusion in the recent example from South Carolina – which, ironically, without the use of mobile phones by students, would have gone unreported:

So, how should we prepare teachers to manage behaviour in their classrooms? The English government has asked Tom Bennett to canvass opinions, so please share your views below, and at:behaviourmanagement.itt@education.gsi.gov.uk

October 31, 2015

Open Education Needs Collaboration, Not Copyright

“This song is Copyrighted in the U.S., under Seal of Copyright #154085, for a period of 28 years, and anybody caught singin’ it without our permission, will be mighty good friends of ourn, cause we don’t give a dern. Publish it. Write it. Sing it. Swing to it. Yodel it. We wrote it, that’s all we wanted to do.”

“ Open will win. It will win on the internet and will then cascade across many walks of life: The future of government is transparency. .. The future of culture is freedom. The future of science and medicine is collaboration. “

Jonathan Rosenberg, Senior VP, Google

______________________________________

We’ve all googled for a particular article or paper, only to find that we’d have to pay $30 to read it and thought ‘stuff that – someone will have made it available for nothing’. Paywalls are the bane of researcher’s lives. So, when I heard about the #icanhazpdf hashtag, it seemed, not only unnecessary, but also verging on the paranoid.

Allow me to explain: Some academics, frustrated at the lack of Open Access to their work, are promoting ‘circumvention’. Andrea Kuszewski set up the hashtag #icanhazpdf, (a tribute to the infamous #icanhascheezburger meme) to encourage authors of paywalled articles to share pdf copies of their work. I’ve shared pdfs of my own articles, dozens of times. But by doing so, authors, having handed over the rights to the publisher, are technically in breach of copyright law. So, once the requested #icanhazpdf paper has been delivered, Andrea strongly recommends that the tweet is swiftly deleted. She describes it as ‘an act of civil disobedience – it’s just a way of saying things need to change.’

Like I said, ingenious, playful, but a tad paranoid? That was until I heard about Dan Pazskowski . Dan is the CEO of the Canadian Vintners Association. An article concerning the CVA appeared in Blacklock’s Reporter, a subscription-only journal. Dan didn’t have a subscription, but a colleague did, so Dan asked for a copy of the article. When Dan contacted Blacklock’s Reporter about some inaccuracies in the article, he was asked how he’d read the article, as he wasn’t a subscriber. He was then sent an invoice for $314, which he refused to pay. Dan was then taken to the Ontario Small Claims Court, where he was ordered to pay $11,470, plus taxes, in damages.

So, it’s perfectly legal to lend a friend a copy of a book you’ve bought, but not, apparently, a journal article? Dan is appealing the decision and all advocates of open access will be hoping he wins. Jonathan Rosenberg is right: OPEN will win. But vested interests will fight tooth-and-claw to hang on to outdated, and restrictive, copyright shackles.

The battle for OPEN is in constant play. This week saw some significant gains for Open Access advocates: US Secretary of State for Education Arne Duncan introduced the ‘#GoOpen’ initiative. This government campaign ‘encourage’ states, districts and schools to use open licensed education materials. In order to provide further encouragement, legislation is being proposed ‘that would require all copyrightable intellectual property created with Department grant funds to have an open license.’ A growing number of districts are supporting the initiative, which could eventually see the end of the textbook in US schools. I haven’t yet seen the response from the major education publishers, but I can’t imagine they’re thrilled at the prospect.

In the UK, the Open Access movement has largely been confined to higher education institutions. The logic in both the UK and the US is the same: when academic papers have been publicly funded by taxpayers, why should we have to pay again to read them? Most colleges around the world have to pay tens of thousands of dollars a year in subscriptions to academic journals, yet the authors of these papers rarely receive payment for their publication.

Academics want their work to be shared with the widest possible audience. As an Oxford academic recently said: ‘Most academics want to communicate things; most conventional publishing fails to do that substantially.’ Do the maths: even popular academic over-priced books sell in the low thousands – Ken Robinson’s Creativity Ted talk has been viewed thirty-five million times.

We’re witnessing ideas spreading like bush fires, through personal and social networks, tweets, Facebook, blogs and google searches. The future of innovation, and the future of research, lies in collaboration, and that can’t happen whilst knowledge is locked away and people face prosecution for attempting to unlock it.

October 23, 2015

Beyond Engagement

During one of the recent #satchatoc discussions, led by the remarkable Andrea Stringer, a teacher, Greg Ashman, queried the assumption that student engagement should be pursued:

During one of the recent #satchatoc discussions, led by the remarkable Andrea Stringer, a teacher, Greg Ashman, queried the assumption that student engagement should be pursued:

‘There must be some larger rationale, right? What’s the objective? I’m not saying it’s a bad idea. I used to be in charge of ‘student voice’. But I never asked why’

It’s a really good question, Greg, and one that is all too infrequently asked. By not having these reality checks we run the risk of perpetuating some of the myths around student engagement:

1. Engaging students is the teacher’s responsibility. A recent Edutopia article began ‘Keeping students captivated and ready to learn is no small task’. Captivated? I know quite a few educators who’d settle for ‘conscious’.. These kind of ‘top tips for teachers’ reinforce the notion of teacher-as-entertainer;

2. Engagement = having fun, right? Wrong. While I firmly believe that engagement precedes learning (you can’t have deep learning if you’re not focussed), it doesn’t always follow that learning will automatically follow engagement;

3. Get engagement right and students will achieve. Alfie Kohn‘s aphorism ‘when interest appears, achievement usually follows’ carries a ring of truth, but attainment, per se, shouldn’t be the driver behind a desire to enhance engagement. For one thing, our assessment systems have a narrow focus, and an engaged student will take their interests to deeper, more diverse, places than most tests can accommodate. But that’s a reflection on assessment, not engagement.

To answer Greg’s challenge, I believe we have to think beyond engagement, or it remains a classroom strategy, when it’s so much more than that. For me, the pursuit of engagement is the pursuit of depth – in relationships, in context, and of course in learning. In exam-driven systems – where students increasingly ask ‘does it count?’ (towards grades), before commencing a task – we need a counterbalance to the obsession of superficially ‘covering’ the curriculum that dominates most teaching and learning strategies.

But we also need to think beyond engagement, because our current students will have multiple jobs, and portfolio freelance careers in 10-15 years time. They’ll have to learn, unlearn and re-learn knowledge and skills in order to be employable – and they’ll have to think independently if they’re to avoid the increasing danger of automation. If your school career was largely spent in a state of disengagement or, worse, feigning engagement, you’re going to be ill-prepared for the demands of the knowledge economy. This is why great educators want their students to think like scientists, engineers, artists – being engaged is just the first, though necessary, step in being ready for the world of work.

But will an engaged class get better test scores? The evidence is unclear – a teacher who seeks engagement is unlikely to favour teaching to the test, and students delving deeply into a subject area in their spare time, might be considered time that could be spent on exam revision. But we have to think longer-term: is our job as educators simply to get our students to score well during the time they’re with us? Or do we have a responsibility for their longer-term prospects? Because here there is growing evidence that students who are engaged in learning at school (not the same as engaged in school) have better life chances than those who are disengaged, irrespective of exam results or soci0-economic background. Better jobs, more likely to complete higher education.

For me, that’s why engagement matters, but we have to think beyond engagement.

And how do we design engaging learning? I’d like to suggest that we need to think less about entertaining/captivating our students – what we do, and how we behave – and more about the ‘why?’. As an educator, I’ve never been irritated when students ask ‘why do we need to learn this?’ – being clear about the purpose is a prerequisite for engagement.

Equally, authenticity and relevance matter. Writing an essay about the holocaust will generate useful research, but interviewing a holocaust survivor will go deeper and make a personal connection. Understanding the health impact of air pollution in developing economies is important, but wouldn’t the issues be better examined if we measured pollution in our own communities? This is one of the reasons why project-based learning is often seen as a catalyst for engagement. When designed well, it can turn knowledge into authentic action.

There are a lot more reasons why I think educators, and schools, need to prioritise engagement (and go beyond it), but perhaps the simplest is to be found in Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi‘s concept of ‘flow’. He describes how that enviable state of flow (or deep engagement) is when both the challenge, and the skills need to overcome that challenge, are greater than anticipated. A sense of clarity and focus emerges, and time disappears. Csikszentmihalyi argues that we are at our happiest, our most fulfilled, when in that state of flow.

There are a lot more reasons why I think educators, and schools, need to prioritise engagement (and go beyond it), but perhaps the simplest is to be found in Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi‘s concept of ‘flow’. He describes how that enviable state of flow (or deep engagement) is when both the challenge, and the skills need to overcome that challenge, are greater than anticipated. A sense of clarity and focus emerges, and time disappears. Csikszentmihalyi argues that we are at our happiest, our most fulfilled, when in that state of flow.

So, for me, striving to create the conditions for enhanced student engagement is as much a human right as it is an educational strategy.

September 8, 2015

Closing The Skills Gap

I recently facilitated a lunchtime discussion, in London, on behalf of the Manpower Group. The event was part of a series called ‘The Human Age’, built upon their excellent report, ‘Entering The Human Age’. The major focus of our session was upon Generation Y (and Z – essentially those aged 16-25) and what is increasingly described as a ‘talent crisis’.

Manpower’s Talent Shortage Survey 2015 estimates that, globally, 38% of employers are having difficulty filling jobs. The key factors behind this shortfall include a lack of applicants, a lack of technical competencies, a lack of experience, and a lack of ‘soft’ skills.

Manpower’s Talent Shortage Survey 2015 estimates that, globally, 38% of employers are having difficulty filling jobs. The key factors behind this shortfall include a lack of applicants, a lack of technical competencies, a lack of experience, and a lack of ‘soft’ skills.

Although only 14% of UK employers are having difficulties filling jobs, those attending the event (HR people from a wide spread of major employers) seemed to confirm those contributory factors. So, how have we got to this position? I would offer two explanations: firstly, we’ve divorced formal learning from the world of work; second, our brightest young minds no longer look to follow a traditional career path.

As someone who regularly works with schools and colleges – in the UK and in Australia – I’m frequently reminded of Seymour Sarason’s assertion that ‘the best way to prepare young people for the world beyond school, is to put them in that world, as often as possible’. The advent of the PISA international comparisons of literacy, numeracy and science skills has led to a relentless focus, by successive governments, upon the core skills of English and Maths, in the UK and elsewhere. Tony Blair’s target of 50% of young people going to university triggered the ‘academisation’ of learning. Filling in worksheets replaced opportunities to learn through projects, outside the classroom. Vocational training has progressively been starved of either investment or respect (despite the continuing shortage of skilled trade workers). Is it any surprise, therefore, that the biggest shortage of talent (according to manpower) lies in the skilled trades sector?

There’s a telling quote from Laszlo Bock, Senior VP at Google on the growing mismatch between preparation for employment and the actual needs of employers:

““Beware. Your degree is not a proxy for your ability to do any job. The world only cares about — and pays off on — what you can do with what you know (and it doesn’t care how you learned it).

And in an age when innovation is increasingly a group endeavor, it also cares about a lot of soft skills —

leadership, humility, collaboration, adaptability and loving to learn and re-learn.

This will be true no matter where you go to work.”

These highlighted so-called ‘soft’ skills are the ones that get sacrificed when the sole focus of education becomes preparation for the written test, rather than the acquisition of practical, real-life skills. It’s one of the reasons that both Google and Ernst & Young now say that they ignore qualifications when choosing new employees.

But if there are problems on the supply side, there are even bigger challenges on the demand side (remember the biggest cited difficulty in filling jobs was lack of applicants). Increasingly, enterprising school and college leavers are choosing not to seek employment, but to create their own jobs. My presentation identified at least five reasons why, from their perspective, smart Gen Y/Zers aren’t applying to your company:

1. It’s never been easier to work for yourself – knowledge process outsourcing sites like UpWork and freelancer.com make it easy to become a micro start-up. You can even start the process while you’re in school or college. And we’ve finally reached the point where the place you work from doesn’t matter.

2. Your network matters too much for you to give it up - think about it: when most over-40s were 18 our social network could be counted on a few hands. For Gen Y, their network is global, large, and the basis of collaborative work.

3. Every business has to be a social business – in last year’s Randstad survey of Gen Y/Z, doing meaningful work matters almost as much as the salary they’re paid. This generation are looking for much more than a set of values and a CSR programme. If they can’t find a sense of fulfilment in an employer, they’ll create their own.

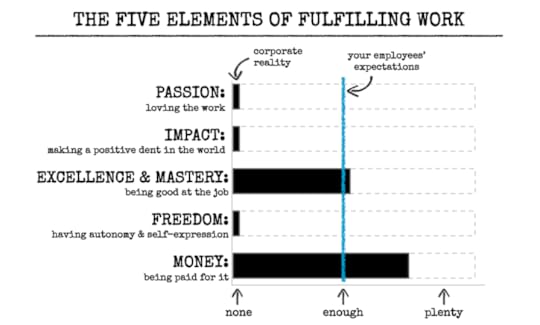

4. Why join the 87%? – Gallup’s last global survey on employee engagement found that only 13% of workers would describe themselves as engaged. Today’s young people have higher expectations of being engaged by their work, and are more likely to find that running their own projects.

5. You’ve more chance of being replaced by a robot – the human age is also blending into the automation age. By 2030, 47% of the world’s current jobs could be replaced by a robot, or artificial intelligence, or automated software. Ironically, some of the jobs that can’t currently be filled (think drivers of all descriptions) could be fixed by automation (for example, driverless cars, trucks and trains)

So, how can companies respond to both supply and demand-side challenges? As we discussed at the event, if organisations are unhappy about the way young people are being prepared for the world of work, they have essentially two options: 1) work with education providers – and government – to make sure the right skills, experiences and dispositions are being developed, or 2) hire based on attitude, not qualifications, and provide your own learning programmes.

But that’s only half the battle – retaining young talent requires a fundamental re-alignment of values, structures and culture with the expectations of young people. In a recent blog, Dom Jackman, co-founder of Escape The City – a consultancy which helps reorientate disaffected corporate employees – provided a neat graphic illustrating the current gap

.

Closing the skills gap is a challenge that occupies the minds of many human resources directors. Closing the expectations gap has had rather less attention paid to it. We need to change that.

July 5, 2015

Will The Last Teacher Leaving Please Switch Off The Lights?

June 8, 2015

Will The Last Teacher Leaving Please Switch Off The Lights?

I was in Australia when the UK general election took place. I can’t say I was looking forward to coming back to an educational landscape that would allow the Conservative government unfettered control over educational policy, especially after having had a month of (largely) positivity and optimism from teachers and school leaders all over Australia.

I was in Australia when the UK general election took place. I can’t say I was looking forward to coming back to an educational landscape that would allow the Conservative government unfettered control over educational policy, especially after having had a month of (largely) positivity and optimism from teachers and school leaders all over Australia.

That’s not a criticism of English educators: their morale has been the subject of a particularly energetic version of ‘Whack-A-Teacher’ by successive governments for a couple of decades at least. But the Michael Gove-led assault on their integrity and motivation was barely ameliorated by the Lib Dems, and now that they’ve got a majority, even the more acceptable face of Nicky Morgan is on the warpath – this time, it’s so-called ‘coasting’ schools that are bearing the brunt. We’ll come to what constitutes a coasting school in a moment, but it’s worth looking at the impact these strategies are having on the profession.

In 2005, 20% of newly-qualified teachers had left the profession within a year. By 2011, those leaving within a year had risen to nearly 40% – within a year. Current figures aren’t available, but I suspect the picture now is even worse. We do know that half of all new teachers have left within five years. Morgan and school reform minister, Nick Gibb, insist that students behaving badly is driving NQTs out of teaching. The OFSTED boss, Michael Wilshaw agrees with this analysis. When teachers themselves are asked why they are thinking of leaving, bad behaviour features in only 25% of responses; 76% blame workload – and one-in-three blame ‘teacher bashing’. Silly teachers – they don’t even know their own minds. Despite the fact that teacher vacancies rose by 30% in 2013 Nick Gibb insists there’s no recruitment crisis.

And so to this week’s morale-boosting announcement. Nicky Morgan has attacked ‘complacency’ in our school system: “for too long, a group of coasting schools, many in leafy areas with more advantages than schools in disadvantaged communities, have fallen beneath the radar.” But the criteria for coasting? Well, that will be based purely on exam results: 60% of good GCSE passes in secondary schools, and 85% achieving a level 4 in reading, writing and maths at primary level. Far from punishing schools in leafy suburbs, this will disproportionately affect schools in poorer, socially deprived areas.

Ms Morgan insists that she wants to see ‘an above-average proportion of pupils making acceptable progress.‘, but she’s blissfully unaware of the inherent bell-curve nature of norm-referenced standardised-testing (please read headteacher Tom Sherrington’s excoriating Maths 101 response). Laura McInerney provided a much more effective definition, and graphically laid out – as an ex-teacher – the impact Morgan’s coasting strategy will have upon the morale of teachers who need our support the most, and schools that find it hardest to attract new, enthusiastic teachers – those working in really tough circumstances.

Oh, but I forgot! We’re not allowed to ‘make excuses’ for the failure of kids living in low socio-economic areas to achieve their full potential. For that makes us ‘enemies of promise’. Never mind that the Joseph Rowntree Foundation study found that only 14% of low attainment can be attributed to school quality, the rest coming from a complex mix of cultural and socio-economic factors, most notably poverty. When you’re hell-bent on playing ‘whack-a-teacher’, the only poverty that matters is poverty of expectation (ours not theirs).

Hell, why not go the whole hog and abolish child poverty? Because that’s what this government seems intent on doing. Having seen that absolute child poverty has risen by half-a-million since coming to power, the government is doing what any self-respecting government would do: scrap the measures and abandon any targets. (If only they’d do that for school accountability, but it seems that there’s one law for them, and another for the rest of us).

Well, I’m sorry, but in a week where it’s taken an Australian to tell it like it is with this government (Thanks Adam) let me add my advice to ministers:

Child poverty is a thing. It actually exists, even though you’d rather re-define it away. Kids have lots of challenges due to the aforementioned poverty, or being newly-arrived in this country, or being carers – some will overcome them, but achieving ‘good’ exam results has to be seen in context. Saying that a teacher who has managed to educate a child who arrived with almost non-existent oracy, literacy and numeracy skills, and got them to get an ‘average’ pass mark, is a greater achievement than coaching a middle-class kid at an independent school to A-star results. Telling that teacher that they’re ‘coasting’ is an apalling insult.

The teacher recruitment crisis is a thing. Teacher morale is also a thing. It’s at an all-time low. If you keep going like this, the only teaching jobs being filled in this country will be at those independent schools.