David Price's Blog, page 2

October 23, 2016

Is It Time For A Different Story?

“It is not what you put into the child, but what you draw out that constitutes education.”

BH Montgomery Head, King Alfred School 1945-1962

This has been one of those weeks that I suspect I’ll remember for a very long time. A week ago, I was giving a keynote at King Alfred School, in London. The school is an independent school and, if I’m being completely honest, not one that I would have spoken at in the past.

I’m so glad I decided to accept the invitation to speak there.

The occasion was the Annual Conference of the King Alfred School Society, the group that has steered the philosophy of the school since its inception in 1898. It was born out of frustration with Victorian schooling, and, as the film below shows, placed a strong emphasis upon values that are pretty much unchanged, today: Mutual respect; Individuality and self-reliance; Social responsibility; Freedom, play and the enjoyment of education; A broad definition of success. That’s quite a list, and as current today as it was then.

Its Head Teacher, Robert Lobatto, made it clear in his introduction that the purpose of the day was for staff, parents and visitors, to be challenged as much as inspired. Robert speaks to what W.E.Deming would call a ‘constancy of purpose’, when he says, “Passing examinations is important. However, we want our students to take them in their stride, and value their learning beyond the exam grade. Students will also experience the moral dimension of learning.”

I decided to use the occasion to highlight the almost complete dominance of a narrow, results-obsessed (thanks mainly to PISA) story of what schooling should look like. Progressive schools, at least in the state sector, are under unprecedented pressure to sacrifice all the components of a well-rounded education, in pursuit of literacy, numeracy and science. The arts are being squeezed out of curricula, as are those who advocate any form of ‘independent learning’. The fixation upon ‘keeping our children safe’ means that it’s impossible to imagine the King Alfred ritual, where every child has to climb the school tree, happening in many UK state schools. The King Alfred Year 8 students also create ‘the village’, where they build huts, eschew electricity, phones and the internet, and work out their own community, living together for a week – such projects may happen in many UK schools, but I’ve yet to come across anything quite like ‘the village’.

We have to accept that in countries like the UK and the USA, schools are increasingly becoming regimented, joyless, exam-factories. The increases in mental health issues among our young people are truly alarming: a doubling of depression between the 1980s and 2000s, and a 75% increase in self-harm cases, over the past five years, in British young people; a 44% increase in adolescents accessing mental health services in the USA, between 1998 and 2012; steadily increasing rates of attempted and actual suicides on both sides of the Atlantic. Of course, there are many factors behind these increases, but increased anxiety to get good grades, in order to get into university, is real.

So, the gist of my talk was this: the current perception of a ‘good’ school being defined only by their test scores, has become so all-pervasive, that we now need to create a different narrative around the purpose, and outcomes, of an education worth having.

I thought of King Alfred this morning when I read this article from the Washington Post, on the injection of ‘joy’ as a character strength in so-called “no excuses” charter schools. Now, I get it with the ‘no excuses’ argument – if your mission is to close the achievement gap, then inner-city kids probably need to have their expectations raised. But if the only way to achieve good results is to make students quiet, submissive droids (if you want to see what submissive students look like see this video), and then have ‘joyous interludes’, then you’ve lost the argument. The article highlights one school, Achievement First, where the prescribed ‘joy’ in the classroom consists of making kids do the following chant: “Hey hey hey, I feel all right,” followed with a stomp. The phrase is repeated with two stomps, then three stomps and finished off with: “I feel motivated to learn. And graduate college.”

When I read this kind of stuff, I’m trying hard not to think of the last time I heard African-Americans being told what to chant, in order to make them more productive. Instead, I like to think that, however well meaning their aim, their short term results (there’s no doubt that test scores will improve when you push kids through a high-intensity sausage machine) are offset by the long-term absence of independent and critical thinking. The long-term prospects for these kids are not being helped by this kind of logic: yes, we know we tell you what to do every second of the day, and because that’s dispiriting, we’ll mandate episodes of joy by telling you what to chant. KIPP Triumph Academy’s handbook explains it this way: ‘For fifth-graders, learning to chant their multiplication tables during summer school is an essential part of their KIPPnotizing’.

Wouldn’t it be simpler just to stop the brainwashing, and commit to making learning joyful wherever possible?

Ørestad Gymnasium: Where students take responsibility for their own learning

I spent the rest of the week with leaders from some of the most innovative schools in the world, visiting schools in Denmark. Although the Danish government is nudging school improvement down the ‘test scores are all’ route, what we saw were academically successful schools that still believe in giving students a well-rounded curriculum, and the space – and time – to discover who they are, and the kind of future they want for themselves.

Hellerup School: 4 floors, one big open space

And here’s the thing: it’s not an either/or. Hellerup School and Ørestad Gymnasium, both in Copenhagen, share very similar characteristics to King Alfred School: they get good results, but they’re developing students’ abilities to problem-solve, think imaginatively, and show empathy and compassion for others. Their students don’t seem to be stressed, (Denmark has, after all, been rated the happiest country in the world) and they really enjoy coming to school.

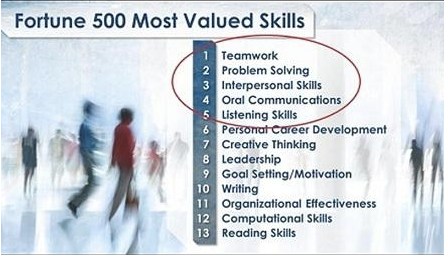

When the school leaders (from USA, Cambodia, Australia, India, Denmark and the UK) got together to make sense of the week, a clear message emerged: we have a growing evidence base that demonstrates that what governments are telling us we need is diametrically opposed to what the majority of parents, employers and students want from our schools. Take a look, for instance, at this list of Fortune 500 companies ‘most valued skills’ list:

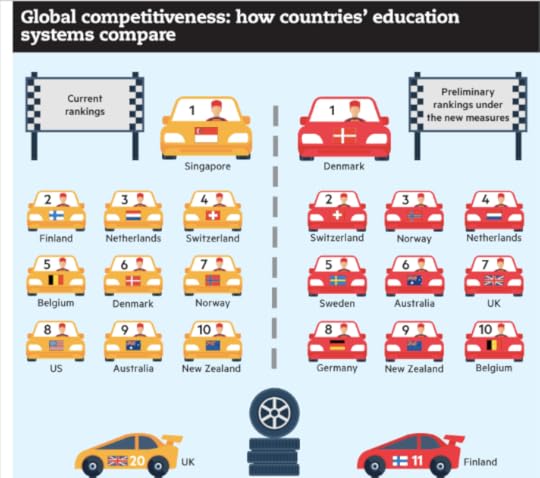

The PISA rankings offer a much too narrow assessment of students capabilities. Thankfully, the World Economic Forum has just announced that it will ditch its current criteria – including quality of maths and science, and how well schools are managed, in favour of student’s preparedness for the new world of work. This aligns with the Fortune 500 most valued skills, ranking students by a range of measures, including ICT skills, collaboration, critical thinking and problem-solving. This shift tells a very different story:

World Economic Forum: On the left – current assessment of core subjects and school management. On the right: preparedness for work

And it’s striking how none of the Far-Eastern countries that dominate the PISA rankings feature in this more rounded assessment of student skills!

If we’re really going to give our kids the best preparation for an increasingly uncertain world beyond school, (not to mention saving the sanity of a dangerously dispirited teaching workforce) then we have to forge alliances wherever we can find them:

We can’t allow independent/government schools to ignore one another, so that we can accumulate the necessary evidence that you can have both well-rounded, happy, employment-ready citizens whilst still achieving good academic outcomes;

We have to give voice to parents’ concerns that their kids’ welfare matters more than improving the national PISA ranking;

We have to amplify the voice of business leaders when they tell us that the current ‘teaching to the test’ regime isn’t giving them the workforce they need;

We have to find ways to measure the skills and aptitudes that might not show up on a standardised test, but matter just as much;

We need to show the positive impacts of a more progressive and humanistic approach to schooling: a lifelong love of learning; a reduction in mental health issues; the ability to think for yourself; the opportunity to find your ‘element’ through a rich and broad curriculum; the development of skills that employers are crying out for.

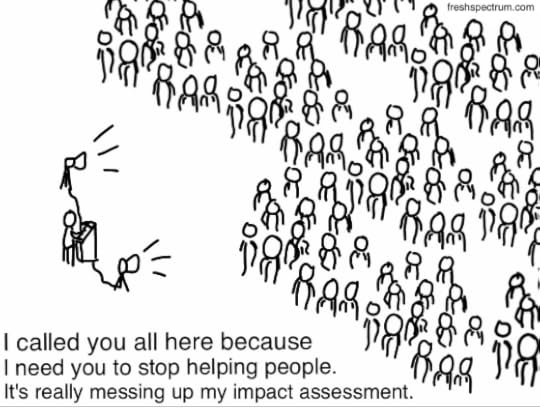

I’ve written this post after talking with a number of very experienced educators. I think it’s fair to say that we all feel that a cross-sector coalition of parents, employers, teachers and students could create an idea whose time has come. Then again, I could be sitting in the middle of an echo chamber.

So, please leave a comment below (“even if it’s just an ‘agree/disagree’). Is it time to reverse the results-driven direction we’ve been heading in for decades, and, collectively tell a different story?

October 11, 2016

What Counts As Evidence in Changing Practice?

(This is one of my longer posts, but it necessarily deals with quite a lot of detail – I’ve tried to shorten it through the inclusion of links to further detail)

A few weeks ago I was embroiled in a heated (though ultimately futile) argument with a teacher from Australia who claimed that I was training teachers in a methodology (Project-Based Learning) for which there was no positive evidence.

Even as I was presenting the evidence, I knew it would make little difference to his view: for all the supposed impartiality of educational researchers, personal bias and the cherry-picking of supportive evidence still marks most of the – increasingly acrimonious – social media ‘debates’. And, yes, I’m as guilty of choosing my evidence as anyone else.

In my defence, I feel I can be excused on one count: I don’t go along with the current obsession that any educator should only care about ‘evidence-based practice’. And the past few weeks have given me a chance to think about what teachers look for when they decide to innovate in the classroom, not least because I’ve been running workshops in the science of improvement (more of which later) in Australia, India and (soon) the UK.

There’s a dismissive view of some education researchers, that teachers work mainly on their guts, introducing only the innovations that press their political, cultural and emotional buttons. They’re accused of failing their students because they don’t keep abreast of the empirical evidence emerging in academic journals. If that isn’t bad enough, even more scorn is reserved for those who use evidence to inform their teaching and learning strategies but use the wrong type of evidence. Twitter is full of these arcane, ‘angels-on-pinheads’ back-and-forth slanging matches. For now, let’s ignore the question of why so much academic research is written for fellow academics, rather than teachers (but please read this really cogent critique on the failure of research to affect practice in education)

Now, I want to clear – there is undoubtedly value in RCTs when evaluating classroom innovation. But there are also deep flaws that many teachers rarely get to hear about. I want to touch on them here, but I don’t wan’t to get into the nit-picking detail, as this post is aimed at time-starved teachers – people who get excited about that stuff can investigate the integrated links.

Concerns about using RCTs in Evidence-Based Education emerged soon after the first RCTs were conducted. The key issues could be summarised as:

RCTs exist to identify causality and predictability. But complexity theory suggests that conclusions drawn from RCTs ignore context and, as we know, context is everything. A paper written 15 years ago supports the view of W.E. Deming, that you can’t understand why something worked unless you look at the system in which it worked: the people, the structures, the motivations behind the implementation…I could go on. Well-respected academics have even suggested that the same teacher, teaching the same class, will see markedly different outcomes from one day to the next. What difference does chance play depending upon the day that data is gathered?

RCTs attempt to eliminate variables during the implementation period, but the given innovation is then scaled-up in a wide variety of conditions, where results are invariably less impressive. This explains why we’ve seen a succession of ‘silver bullets’ hailed as transformative, only to be re-classified as duds in the intervening years. The elimination of variables doesn’t just plague education: healthcare research is similarly torn between attempts to eliminate all variables, and a desire to put experiments into ‘real world’ conditions;

RCTs are also criticised for understating the value of other data sources, and for failing to investigate what Yong Zhao has labelled ‘side effects’ – unintended consequences and impacts further down the chain;

There are serious ethical considerations behind RCTs, particularly in promising cancer treatments (I speak from personal experience) – many people feel that it’s not only ethically wrong to deny stage four cancer patients access to promising new drugs (by giving them placebos) but that they will ‘contaminate’ the evidence by finding their own alternative treatments. We don’t have ‘placebo’ effects in education, but we do have control groups, against whom intervention effects can be compared. But think about the amount of variables involved in this group: the learning kids do at home; the impact upon learning that their non-participating teachers have; the oft-reported higher levels of time and enthusiasm allocated to the novel, compared to the control experience . (Anecdote: a while ago I’d delivered two days of Project-Based Learning training at a school who then asked how they could further extend their professional implementation of PBL. I suggested they join the trial group of a national RCT into the impact upon literacy/numeracy that projects can make. They then told me they were already in the control group! “But you’re contaminating the evidence” I said. The senior leader said: “We’ve been told we can’t touch PBL as a methodology for the next three years – our kids can’t wait that long!”) I would argue that it’s not only futile to eliminate all variables in RCTs, it’s ethically questionable;

RCTs may be seen as the gold standard, but you only have to look at the literature surrounding RCTs to see that there are ‘good’ and ‘bad’ RCTs (in design, execution and analysis). Equally, any given classroom innovation can be implemented well or appallingly. I have seen excellent Project-Based Learning practice, for example, and really, really, awful implementation – the impacts upon learning would be poles apart. RCTs attempt to lay strict guidelines on the implementation of the innovation being evaluated, but so long as humans are delivering these innovations, there’ll always be significant differences.

(Please note: this is intentionally a broad overview of problems with RCTs. For a forensic examination in flaws on the US What Works Clearing House evaluation in a single subject (Maths), I’d urge you to read Smith and Ginsburg’s excellent paper, Do Randomized Controlled Trials Meet the “Gold Standard” ? , where they cite a whole host of specific flaws with studies that were influencing policy making. Also see Nick Hassey’s piece on RCT limitations )

In summary, RCTs will inevitably confirm that anything can work for some schools, under some conditions, and in some contexts. But they also prove that no single innovation can work for everyone, everywhere. Yet this is precisely how they’re used by policy-forming politicians.

Ah, but what about meta-analyses? Surely, when you gather enough data, the bumps in the road listed previously can be smoothed out, and absolute conclusions drawn? This, after all, is how John Hattie’s ‘Visible learning’ came to be seen as ‘the holy grail’ for teachers.

Would that it were so…. Since the publication of ‘Visible Learning’, there have been a string of criticisms surrounding the methodology used (averaging effect sizes is misleading), the maths deployed (Hattie initially indicated probability as a negative number, which – I’m assured – is mathematically impossible), the idea of ranking interventions, and, the most problematic of all, the categorisation of interventions. I understand why, in an attempt to make sense of 1200 meta-analyses, you have to have some general classifications, but by ranking them for effectiveness, a license to cherry-pick was unleashed, and the inevitable dumbing-down of complex data spawned a whole host of dumb statements by education ministers globally. What, for example, constitutes a ‘Creativity progamme’? And is it significantly more impactful than homework? The label ‘direct instruction’ covers a multitude of sins, like ‘problem-based learning’, but, hey, it’s more effective, so what we see around the world are creative problem-seeking teaching strategies being abandoned for discredited ‘explicit instruction’ pedagogies that Hattie never had in mind to begin with. And we’re now seeing a whole industry springing up to support teachers in making learning ‘visible’.

It seems that, although it was done for the right motives, the end-result of the Visible Learning phenomenon has been to further de-professionalise teachers, and impoverish the debate around educational reform, not enhance it.

(And you can’t read Todd Rose’s excellent “The End of Average’ without seeing any processes resulting from averaging in a new light – more in a future review.)

Ultimately defining what works will always be a matter of teacher judgement, not simply data, and the disproportionate leverage of RCTs and meta-analyses causes teachers to question their own judgement, not complement it.

So what else counts when considering whether to introduce a new innovation? Here are (at least) seven factors:

See for yourself – I write books, pamphlets and articles. I give talks, I run training events. But the single most persuasive factor in convincing teachers is for them to see it in action. They compare contexts and organising systems. Most importantly, they see the effect upon students, and determine how their own students might respond. There’s a reason why the High Tech High schools in San Diego (global exemplars of project-based learning and much more) receive over 5000 visitors a year;

Speak to peers – social media makes this a far easier proposition than it used to be. When I was first advocating the pedagogies behind the Musical Futures programme, teachers were openly sceptical. And rightly so. But once they’d talked to a teacher who’d been there and done it, they were more willing to try it out;

Have a problem to which the given innovation might represent a potential solution – there are simply too many silver bullets out there, so a disciplined innovator is much more likely to look at those that might meet their ‘moment of need’;

Undertake training – if our training is indicative, this is often the final step before introducing an innovation. And it’s surprising how often this stage is skipped, contributing to less than impressive results, compared to the original pilot;

Examine student outcomes – and not necessarily test scores, though of course these matter. When we had sufficient data from the Musical Futures evaluation to show a 30%+ increase in students electing to take music as a result of the innovation, the scale-up really began to snowball;

Determine the match with the school’s culture, design and philosophy – an innovation can only attain a sustainable improvement if there’s coherence with the school development plan, and the support structures. Put simply, without senior leadership support, any innovation is dead in the water. As Peter Drucker famously observed ‘culture eats strategy for breakfast’, and nowhere more so than the school staffroom;

Parental response – woe betide the senior leader who attempts to introduce iPads, or BYOD, or circadian rhythm-determined start times, without testing the waters with parents first.

So, these are just some of the forms of evidence that are important to educators. To repeat, there’s clearly an important place for RCT data and meta-analyses, but they’re no more important than teachers exercising their professional judgement through more practice based sources.

I believe that the only sustainable future for professional learning and innovation in schools is one which is driven by teachers, not externally imposed. One that sees innovation as constant, not coercive, or ad-hoc. This is why I believe so much in transferring the science of improvement from the healthcare, aviation and automotive sectors into education – and I’ll examine this in more detail in my next post.

Teachers need to work with academics to design their own innovations and then determine what evidence works for them, not for others. What if, instead of urging evidence-based practice, we called for the reverse: what Tony Bryk called ‘practice-based evidence’ – how might the pace, and ownership, of innovation, be transformed?

September 7, 2016

Biting on Twitter Has Consequences

Recently I wrote a blog post about the aggressive tone of some teachers on Twitter. I had ten times the number of views compared with any previous post, so I assume it struck a chord. Because one of the stock defences by such people when challenged is to complain of ‘ad hominem’ personal attacks, I made no direct references to individuals. I’d still rather not, but a post at the weekend by Greg Ashman (a teacher from an independent school in Ballarat, Victoria) has given me no option but to respond in-kind.

Mr Ashman had come across a flyer for our new programme  “Deeper Learning Through Projects” and tweeted me to ask why there was no evidence quoted for the effectiveness of project-based learning on the flyer. I replied “It’s a flyer Greg, not a research paper”. In a civilised world that might have been the end of it. But very soon thereafter Mr Ashman wrote this blog post, naming me as the person that the NSW governments is spendin

“Deeper Learning Through Projects” and tweeted me to ask why there was no evidence quoted for the effectiveness of project-based learning on the flyer. I replied “It’s a flyer Greg, not a research paper”. In a civilised world that might have been the end of it. But very soon thereafter Mr Ashman wrote this blog post, naming me as the person that the NSW governments is spendin g ‘thousands of taxpayer dollars’ on to deliver training.

g ‘thousands of taxpayer dollars’ on to deliver training.

He then ‘reported’ me, by tweeting his post to the NSW Department for Education, BOSTES (a teacher accreditation agency in Australia) and the Victorian Minister for Education. I’m investigating the potential for defamation in his actions, but I want to use this post as an opportunity to put the record straight, before returning to the consequences of people who use Twitter to malign other educators. It’s worth pointing out however that, should Mr Ashman think he was warning NSW DoE ‘off’ the dangers of project based learning, that last year the NSW Department for Education didn’t just hire me as keynote speaker for their annual schools conference ‘Inspire, Innovate’, they also hired me to run project based learning workshops for government schools. They’ve also got one of the best government websites featuring teacher support for PBL

I tweeted that Mr Ashman was factually inaccurate and displaying a misunderstanding of what project-based learning was, and here’s why:

In his original post, and a subsequent post, he frequently conflates Problem Based Learning with Project Based Learning, when they are very different things – he even says himself that they are ‘not necessarily the same thing’. There’s no necessarily about it, Greg. They’re different. He also describes Project Based Learning as a ‘teaching method’, when it’s not. I freely admit that project-based learning struggles to define itself accurately (no inconsistency there – ‘direct instruction’ and ‘creativity programs’ cover a multitude of sins too). So, in the absence of a copper-bottomed definition, we are left to define it individually. Mine would be that project based learning incorporates a variety of teaching and learning approaches to support students in the acquisition of knowledge and skills, through the creation of purposeful products and services. In other words, it attempts to create the same context that most of us experience in our working lives – we learn through working on projects. In training, I ask teachers to think of it as a ‘wraparound’, and the Buck Institute refer to it as an ‘envelope’ that encompasses a range of pedagogies.

Of course there’s good and bad project based learning (as there is good and bad in any approach to learning – it’s contingent upon the teachers ability to design, scaffold and support the learning). Which is why I always say that, personally, I would prefer that teachers deployed direct explicit instruction well, than project based learning badly.

Mr Ashman says that there’s very little evidence of project based learning’s effectiveness quoted on my website. That’s true. That’s because I believe that busy teachers don’t have time to plough through footnotes, references and sidebars. I had a lot more citations in my book, OPEN, but my editor told me to thin them down as it was becoming indigestible, and I had always wanted to write a book that any parent, teacher or student could read (1) . Additionally, if he had bothered to attend any of our training events he would see that I cite evidence quite a bit and every school attending our training receives a usb with a resource pack containing teacher guides, tools, articles and a comprehensive literature review of the research on project-based learning. If Mr Ashman had spent five minutes googling for ‘evidence’ (we’ll come to the problems with evidence in a moment) he would have found it himself. I have added some references at the end of the post for those who see that as the sole yardstick.

To support his criticism of project based learning, Mr Ashman then cites two key texts: Hattie’s ubiquitous ‘Visible Learning’ and a 2006 study by Kirschner, P. A., et al. I can find no direct reference to project based learning anywhere in Visible Learning, and the Kirshner is entitled Why Minimal Guidance During Instruction Does Not Work: An Analysis of the Failure of Constructivist, Discovery, Problem-Based, Experiential, and Inquiry-Based Teaching. So, on the one hand he is arguing that I have no evidence, and his ‘evidence’ is to cite two texts that don’t even investigate project based learning.

There are many concerns about the way in which Hattie’s now-seen-as-seminal book was both put together and subsequently deployed (see here, here, and here (2)) but there’s no denying its clout. Without direct references to projects in Visible Learning we have to look at what our deeper learning training is about and how that figures in Hattie’s top approaches, based on effect size.

The deeper learning training that I run offers tools, scaffolds, and try-outs of a number of approaches that I feel support deeper learning through projects:

Socratic Seminars – these are facilitated class room discussions – ranked #7 in Hattie’s effect size

Peer (and teacher) feed-back – we look at a variety of critiques – ranked #10

Examples of ‘on-demand’ direct instruction – closely related to ‘micro-teaching’ ranked #6

Students critiquing texts – closely aligned with reciprocal teaching’ ranked #14

Multiple drafting – aligned to spaced practice ranked #27

Developing oracy skills – not covered by Hattie, but should be)

Scaffolding student research and critical thinking

Meta-cognitive strategies (self reflection through presentations of learning)

In addition to coaching in these strategies, the training also puts teachers in the shoes of learners through the completion of a project – in the current programme, creating/publishing a 30pp ‘book’ showing their research, hypotheses, writing and predictions.

There is a perception held by some (and I suspect Mr Ashman is one) that see project based learning as an environment where students are largely left to their own devices. And, in fairness, that used to be the case in some of the worst examples propagated during the 1980’s. But the field has advanced significantly since then – it’s just that others haven’t caught up. A classic misconception was brought home to me when I took a group of British teachers over to see the High Tech High schools in San Diego. One teacher gleefully reported back “I saw someone giving a lecture!” as though this were anathema to good PBL practice. The ‘lecture’ in question was being given by Dr Jay Vara, a renowned scientist before joining High Tech High. It was a classic example of ‘micro-teaching’ – a short injection of direct instruction. But the point of departure between myself and the direct instruction folks seems to be that they believe that students can’t begin to work on projects until they’ve been taught everything they will need to know. What Dr Vavra was doing was teaching ‘in the moment of need’, as the students had encountered a problem that could only be solved by an injection of knowledge. Such responses are entirely consistent with good project based learning practice.

The last point I want to make on Mr Ashman’s post was the insinuation that I ‘could be encouraging teachers to use an approach that leads to less equitable outcomes.’ Now, I consider myself a reasonable person, but I don’t need lectures on equity from teachers who are working in schools charing $18,000 per student, and whose students start with a considerable advantage over kids from low SES backgrounds. Don’t get me wrong, I occasionally train teachers in independent schools and I have no problem with them. But practitioners working in these schools should be very careful when making judgements on equity. Ironically, I read Mr Ashman’s second post while working in a special needs support unit in NSW, who attended our training, instigated PBL and have seen remarkable improvements in their students cognitive abilities since introducing PBL (alongside the existing direct instruction). But that’s just personal testimony, and doesn’t count, I suppose. The evidence for PBL and equity (summarised below) exists, but the most powerful evidence is in the outcomes of schools that have based their entire curriculum around a project base. High Tech High (13 schools) and the Expeditionary Learning schools (152 schools) in the US are two of the most prominent examples. Despite having higher than average numbers of students from economically disadvantaged backgrounds (HTH are close to the Mexican border and EL schools are almost all inner city schools) High Tech High student’s college acceptance rates, over an eight year period, have been between 80-90%; 13 of EL’s 31 high schools had a 100% college acceptance rate in 2014.

This data matters to teachers – perhaps more so than heavily averaged generalised interventions listed in Visible Learning – and Mr Ashman demeans himself by offering no evidence on equity and project based learning.

Since he made his criticisms personal, I have to say that I have now spent some time looking at Mr Ashman’s twitter feed and blog and I find it sad and depressing that a teacher would take such apparent pleasure out of what is essentially a deficit view of teaching. His posts seem to fixate upon what doesn’t work , according to his selective use of ‘evidence’, rather than putting his own practice forward, and letting teachers decide if it’s for their kids or not. And his previous history on social media does him no favours. He used to tweet and blog anonymously under the alias of Harry Webb, and Webs of Substance (just to make the rest of us feel inadequate) and, so I’m told, was rather less circumspect than he is now. We have no way of verifying that, since he closed his Twitter account, deleted all the tweets, and his former blog is now locked away (you have to be vetted by him before you can see his posts) He took this action, apparently, because ‘ I didn’t want to have to think about whether something I wrote was in line with my own school’s approach.’

So, presumably now that he’s emerged into the open, his views ARE in line with his school’s approach? If so I feel sad that a school would pour scorn on the gullible fools that attended our PBL training – over 500 teachers in Australia and many more around the world. I’ve said it before, but I’ll say it again: teachers cannot hide behind that ‘all views my own’ smokescreen. When teachers tweet, they are inevitably representing their school, so they should consider that before making unsubstantiated claims, and rounding on their peers.

I’d like to close with a challenge to Mr Ashman: I believe in the professional judgement of teachers, so I put what I believe works, supported by evidence, into my training programmes, and let attendees judge what might be right for their students. I’d invite him to do the same: first, have the courage of your convictions to make your previous tweets and blog public; second, put your own practice up for review by running training programmes, and then we can, in the words of Bing Crosby, accentuate the positive and eliminate the negative.

_______________________________

Research Notes:

As I said in the main body, there is more research needed into what makes for effective project based learning teaching. But it’s not as barren a field as Mr Ashman argues. Here are just some of the studies carried out:

On the positive associations between a Project-Based Learning approach and students’ development of knowledge and cognitive skills :

Parker, W. C., Lo, J., Yeo, A. J., Valencia, S. W., Nguyen, D., Abbott, R. D., Nolen, S. B., Bransford, J. D., & Vye, N. J. (2013). Beyond breadth-speed-test: Toward deeper knowing and engagement in an advanced placement course. American Educational Research Journal, 50(6), 1424-1459.

Harris, C. J., Penuel, W. R., DeBarger, A. H., D’Angelo, C., & Gallagher, L. P. (2014). Curriculum materials make a difference for next generation science learning: Results from Year 1 of a randomized controlled trial. Menlo Park, CA: SRI International.

Gültekin, M. (2005). The effect of project based learning on learning outcomes in the 5th grade social studies course in primary education. Educational Sciences, Theory and Practice, 5(2), 548-557.

Mioduser, D., & Betzer, N. (2007). The contribution of project-based learning to high achievers’ acquisition of technological knowledge and skills. International Journal of Technology and Design Education, 18(1), 59-77.

On the positive effect on SES, SEN and ESL students:

Halvorsen, A-L., Duke, N. K., Brugar, K. A., Block, M. K., Strachan, S. L., Berka, M. B., & Brown, J. M. (2012). Narrowing the achievement gap in second-grade social studies and content area literacy: The promise of a project-based approach. Theory and Research in Social Education, 40, 198-229.

Filippatou, D., & Kaldi, S. (2010). The effectiveness of project-based learning on pupils with learning difficulties regarding academic performance, group work and motivation. International Journal of Special Education, 25(1), 17-26.

Campbell, S. A. (2012). The phenomenological study of ESL students in a project-based learning environment. International Journal of Interdisciplinary Social Sciences, 6(11), 139-152.

____________________

Footnotes:

Access matters. Mr Ashman wrote in a post that he was happy with sales of 70 (seventy) of his book ‘Ouroboros’ (yes, I had to look it up too). Bizarrely, he removed his book from Amazon because he was unhappy with the royalty he was receiving. The kindle version of my book is currently around half the price of Mr Ashman’s, and 25% of my sales (currently close to 40,000) have been heavily discounted.

This highly critical review of Hattie’s maths and methodology contains a comment by ‘Harry Webb’ describing it as an excellent post. Harry Webb is Greg Ashman’s former alias, so one is left wondering whether he approves of Visible Learning’s methology or not.

August 23, 2016

Why do (some) Teachers on Twitter seem so unwilling to learn?

On a warm Saturday afternoon, a few years ago, I was working in a school (it needs to remain nameless as it would be easy to attribute names to places, and I’ve no desire to name and shame anyone in this piece). Anyway, I was facilitating a student-to-staff training session. It was quite a well-known school, not previously known for progressive pedagogy, but here were an entire cohort of teachers being respectfully asked to allow students to co-design lessons, hold regular conversations about what great learning looked like, and remember the need for engaging lessons.

The teachers took all of this critical feedback remarkably well, mainly because the students were so considerate and civil in the phrasing of their feedback – as Ron Berger says, ‘kind, specific and helpful’. I’ve worked in these schools (for they’re a MAT) on a number of occasions, and the students always strike me as polite and keen to hear other’s views.

I was reminded of this experience on recent visits to Twitter. I don’t know if I’m just following the wrong people but it seems to me that there’s a latent aggression in too many exchanges involving teachers these days, that’s both disturbing and surprising. I’m currently training some teachers in Australia about bringing the Socratic seminar into classrooms, so the irony is not lost on me. All educators stand on the shoulders of giants like Socrates, and I think he’d be appalled by the willingness – of a minority – to immediately dismiss views that don’t accord with their own, and the reluctance to understand the others position. Daniel Willingham defined critical thinking as “seeing both sides of an issue”, and that seems to me to be lost in the froth of tetchiness. With some teachers on Twitter, you have to get through an awful lot of ‘critical’ before you get to the thinking.

Now, let’s keep it in perspective. I’m not talking about the kind of cyber-bullying that celebs and D-listers have to endure. But still, educators are supposed to stand for courtesy, reasoning and respect. And I particularly recalled those students because one of those who was having a go at Ross McGill recently was actually a teacher at the school trust mentioned above. Ross (aka @TeacherToolkit, one of the most followed educators on Twitter) gets way more of this stuff than me, but on this occasion I felt the need to support his view (the issue is not important, we’re talking about tone). In the space of an hour he, and I, were called ‘intellectually barren’, ‘gutless’, ‘beyond embarrassing’, ‘unprofessional’, ‘very stupid’, ‘spiteful’, ‘daft’ . Ross got the peak praise: “I would remove my child from a school whose educational culture could be in any way influenced by someone peddling that gibberish.” This was about the point that I asked him to try a little civility and was met with: “if you find me uncivil pls feel free to take your inane arguments elsewhere.”

Like I said this is nothing that Kanye West would even blink at but, call me old-fashioned I still find this sort of thing coming from teachers unsettling. Do they talk to their students like that? If not, why dish it out to fellow professionals?

In the interests of balance, I was also taken to task for categorising those indulging in this (because they frequently hunt in packs) as an ‘arrogant herd’. But here’s the context: another teacher had just dismissed a blog post by the well-respected director of the film ‘Schooling The World’ as ‘the most dreadful nonsense’. Those jumping in were equally dismissive, while there were a few asking why people were dismissing the person, rather than presenting a counter-argument. And then the veil slipped: “calling out anti-scientific mumbo jumbo is an honourable pursuit.”

Ah, the ‘call out’. During the past week, I’ve twice had this kinds of aggressive dismissals defended as in ‘it’s my duty to call this stuff out’ or ‘’I will call you out every time … every time”. The root of this calling someone out is, according to slang dictionaries, the prelude to a fight. And it’s inevitably a duty. An interesting combination of the military and the ‘hood.

And it’s when the veil slips that I think this latent aggression reveals a number of consistencies:

There’s undoubtedly a gender dimension to this. These kind of edutweeters are, in my experience at least, exclusively male. I’m yet to meet a female teacher who puts people down in such condescending, patronising language. So, it’s absolutely a gender thing. Which leads me to….

When calling someone out you have to show absolute belief in your rightness (or righteousness). No scintilla of doubt is tolerated – you are never going to be ‘beaten’ if you refuse to acknowledge that they might have something to say that could trigger introspection or, God forbid, a change of opinion. Besides, there’s just no time for anything other than one-line put-downs when you’re fighting on so many fronts at once (and some of these teacher’s output is prodigious).

The most aggressive put-downs are reserved for those who have either never taught in a school or to those with a significantly higher follower-ship than their own. And you are considered fair game if you meet both of those criteria. So, some of the worst vitriol has been reserved for @SirKenRobinson, @Sugatam (Sugata Mitra), and Graham Brown-Martin. Is there some latent jealousy there, or just a desire to ‘call out’ the bigger kid in the playground?

It’s relatively easy to spot the sort of edu-tweeter I mean. Just go on their profile, read their tweets and see how far you have to go before you see ‘This tweet is not available’. Not that being blocked seems to bother them – in fact it seems to be seen as a notch on the belt, and the bigger the profile of the blocker, the greater the pleasure for the blockee.

Now, I’m not in the league of celebrity of Sir Ken and Sugata, but just so you know, lads (and it is just lads): In the past six years I’ve had two different forms of cancer, a stroke, a heart operation and last year I nearly died of sepsis – during that latest illness I had more bile floating around my system than a year’s worth of Twitter abuse. So, there isn’t a put-down or insult you can imagine that would possibly bother me, but my final point is not a personal, but a professional, one.

I left the last institution I worked for because I realised that I couldn’t say what I really felt about education without it reflecting on that institution. Despite all the disclaimers (“all views my own, not my school’s”) Twitter is a public forum and you do represent your school or college when you Tweet. Some of your students read them, your work colleagues read them, and others inevitably assume those views, values and behaviours are reflective of your host school.

When you’re generous and respectful to others (take a bow @stringer_andrea and @corisel) you are a credit to your school. But when you can’t find a way to disagree agreeably, then don’t be surprised if your employer takes a view.

I know that only a small percentage of teachers are on Twitter anyway, and the overwhelming majority use it to genuinely learn from others. But teachers do have role-model responsibilities – so can we lay off the ‘calling out’ macho pretence, please?

If you’re reading this as a teacher who is new to Twitter, you might be wondering if you should go elsewhere for your professional development. Well, please don’t be put off. As I said at the start, it’s a small minority and the bulk of educators on Twitter are as willing to listen and learn as they are to share and comment.

I wrote in OPEN that social media is morally neutral – it merely holds up a mirror to ourselves. But I also wrote that it’s barely a decade old, and we’re still working out the etiquette. Initially, I was inclined just to ignore those men behaving badly as in the “don’t get involved, it’ll only encourage them”. But I’ve now decided to try a different tack. If I see someone being dismissively abusive, I’m going to try (and no doubt I’ll lapse) a strategy of polite but persistent questioning. I don’t think it serves much purpose to react in kind, but neither do any of us learn anything from a dialogue where a valid question is met with instant scorn.

I’d invite you to do the same. Just ask polite, but persistent questions, so that a one-liner has to be explained and a discourteous personal bard has to be brought back to the point under discussion. Who knows if enough people do it, maybe they’ll either exhaust themselves, or adopt a more respectful tone? One can only hope that, in time, we’ll eventually have a Twitterverse where ‘thinking’ precedes ‘critical’.

I await the first ‘sanctimonious codswallop’ with anticipation….

July 2, 2016

Wilful Ignorance And The Contempt Of Expertise

via Independent.co.uk

It’s been a troubling week in post-Brexit Britain. Racially-motivated hate crimes have risen 500%, with many incidents involving people who couldn’t be mistaken for Europeans, but, still, they were foreign, so it’s OK to pick on them. It’s as though those who have been keeping a lid on their xenophobia have been given approval to tell people (many of whom were born in the UK) to ‘go back where you came from’. Actually, if they’d used those words it might have seemed relatively polite. I can’t repeat many of the insults, they were obscene, and hopefully the law will deal with them.

The extent to which politicians are to blame for the sharp rise in hate crimes is debatable, but it certainly didn’t help when Nigel Farage of UKIP declared in an interview that if immigration isn’t curbed ‘then violence is the next step’.

Alongside the rising anger on the streets is the emergence of an even more worrying trend. In truth, this one’s been around for a long while, but went into overdrive during the referendum campaign. The complete disregard for the ‘truth’ in presenting arguments for and against Brexit, coupled with a lack of contrition when found out, seems to be a tactic used by both The Donald and The Leavers equally. As anyone who’s been in a long-term relationship can attest, truth is the first casualty when passions run high. But, most couples will say “I’m sorry, I didn’t mean it’, when trying to find a way forward. Politicians like Trump, Farage, Johnson and MEP Daniel Hannan have either shrugged their shoulders or have appeared utterly unrepentant when presented with their lies.

But perhaps the most worrying trend in recent months has been the outright revulsion for expertise. In a referendum debate, Michael Gove (former Secretary of State for Education who therefore ought to know better) opined that ‘the people of Britain have had enough of experts’. It has to be said that Gove has previous on this: shortly after taking the job at the Department of Education, when told that business leaders wanted applicants with the so-called ‘C-skills’ (collaboration, creativity, critical thinking) was reported to have said ‘business leaders are talking out of their arses’. Whether that’s apocryphal or real, he subsequently dismissed a whole cadre of academic experts, who presented evidence to suggest his educational reforms might not work, as ‘the Blob’ and ‘enemies of promise’.

How can blatant lie-telling and a contempt for facts appear to not only go unpunished, but in Trump’s case actually improve ratings? Trump has revealed an uncomfortable, even depressing, reality in contemporary politics: a large portion of the electorate simply don’t care about the veracity of facts anymore. It was the economic experts who didn’t see the global financial crash coming, and if global warming was actually a thing, why is it so cold this summer? Don’t listen to experts, pander to your prejudices and your Facebook friends instead….

Above all, public figures are now required to be angry and absolute, above truthful, these days. A while ago playwright Tom Stoppard recorded a documentary called ‘Tom Stoppard Doesn’t Know’ where he emphasised the importance of an internal dialectic, and self-doubt. Such balance of viewpoint seems almost quaint in comparison to the disregard for balance we are living with now.

For people who work in education, or with knowledge, it’s hard to know how to counter the anti-expertise virus that is being intentionally spread by Trump, Gove, and the others. President Obama and John Oliver have recently placed their faith in satire. In a recent speech he said: “It’s not cool to not know what you’re talking about”

Lambasting the wilful distortion of the now infamous claim that the UK sends the EU £350m per week, John Oliver took no prisoners, claiming that the red bus making this spurious claim should have read, “We actually send the EU £190 million a week, which as a proportion of our GDP makes sound fiscal sense. In fact considering some of the benefits we reap in return…oh, shit we’re running out of bus”.

One might hope, with Trump’s ratings plummeting, and both Gove and Johnson facing the end of their political ambitions, that such ridicule is working, and that, eventually, the truth will out. I hope that a popular desire to respect objective expertise might return too. As George Bush (another lover of experts) once famously said: “Fool me once, shame on — shame on you. Fool me — you can’t get fooled again.”

But without wishing to overdramatise the current malaise, if you put these things together, we should not just laugh at ignorance, but also recognise that when it’s wilful (as in the case of Gove, who is an intellectual himself) then something more sinister might be afoot. Racial hatred on the streets, politicians warning of violence if their views aren’t listened to, and open contempt for expertise….when did we last see that? Oh yes, in 1930’s fascism. Let’s keep ridiculing ignorance, but watch out if they start burning books.

May 3, 2016

Seven Reasons Why Taking Your Kids Out Of School Isn’t A Bad Idea

On what has been the first glimpse of summer in Northern England, I’ve spent most of today in the garden, trying to bring some semblance of order to rampant flower beds. As I’ve been weeding, I’ve been listening to the BBC coverage of the so-called ‘parents strike’: a one-day protest organised by parents today who are concerned that we’re testing our kids too often.

On what has been the first glimpse of summer in Northern England, I’ve spent most of today in the garden, trying to bring some semblance of order to rampant flower beds. As I’ve been weeding, I’ve been listening to the BBC coverage of the so-called ‘parents strike’: a one-day protest organised by parents today who are concerned that we’re testing our kids too often.

Having listened to the media reaction, and the Twitter response, I feel sorry for these parents. So, for what it’s worth, here are my reasons why the sky won’t fall in if you take your kids out of school for a day, and why you deserve our support:

Too much testing DOES have consequences.

In the days leading up to the boycott, the Twitter neocons asserted that anyone who was in support of the boycott was ‘teacher bashing’. That certainly wasn’t my impression listening to the teacher-supportive accounts from parents. Some of the tales of kids, anxious and stressed at the prospect of yet another test, were genuinely upsetting – but I didn’t hear one parent attach any blame to teachers . Once these stories started to air, however, the neocons – most prominently from Policy Exchange and the Campaign For Real Education – quickly resorted to some teacher-bashing themselves, arguing that, if kids were stressed, it was teachers that were at fault. They argued that the tests had no consequences for kids, they were only there to make to make bad teachers accountable. These tests, apparently, are critical to spotting reading and writing problems at the earliest stage – all the while ignoring the fact that good teachers do that week-in, week-out But if you still believe that these tests have no consequences for kids, read this recent piece from a parent.

2. Tests aren’t the only yardstick

Teachers are trained to continuously assess, so it’s not clear what purpose these national standardised tests serve (one reason why the previous government got rid of them). All day, the Policy Exchange (founding Chair, Michael Gove, former Sec. Of State for Education) cited OECD stats that placed England at the bottom of the table for literacy and numeracy – conveniently forgetting that the OECD report was looking at adult skills, not primary ages. There’s no yardstick that I’m aware of that suggests we have a problem in literacy and numeracy at primary level. Indeed, some people argue that the reason why our English and Maths scores suffer later on is as a direct result of switching kids off learning through ‘drilling-and-killing’ test prep.

3. There’s no evidence that more tests = better outcomes

Finnish kids don’t even go to school until they’re seven, and they seem to do OK, but they were dismissed by SATs defenders as being too homogenous a society to make viable comparisons. However, when asked repeatedly by BBC reporters to cite evidence that shows a link between testing and improved outcomes, there was a deafening silence…

4. Test prep is time that could be better spent on learning

Please don’t imagine that, when there’s a national spotlight shining on them, schools won’t spend time – lots of it – on preparing kids for tests. It’s just self-protection. I’m not aware of any stats for England, but a recent estimate in the US suggested that, on average, kids spend between 20-25 hours, per test, in preparation. I work a lot in schools, and some schools that are feeling pressure from government high-stakes accountability are now testing their students every six weeks. Add it up.

5. They’re testing the wrong things

We should insist that no standardised test should be inflicted upon our kids that hasn’t been passed by our education ministers. The BBC tripped up schools minister Nick Gibb on the difference between a subordination conjunction and a preposition (I don’t know the difference either). His dismissal of his failure to answer the question correctly (he wasn’t taught grammar at school, and we need to make sure future generations don’t suffer the same fate). Nick, you made it to schools minister without knowing the difference between a preposition and a subordination conjunction – is it such a critical thing to know?

A major source of kids’ stress has been the shift in the nature of the tests: away from expressive writing to regurgitating arcane grammar rules. Author after author has cheerfully admitted today that they couldn’t pass the test, so fear not, parents, it’s not what employers are looking for anyway (and 50% of your kids are going to be freelancers anyway)

6. Taking your kids out of school for a day isn’t going to make a shred of difference to their learning – it might even improve it

Despite the protestations of schools ministers that even a day out harms their learning, it won’t. If that were the case, then alumni from Summerhill School (where kids can opt to attend classes or not) would be living on the streets, their prospects ruined by not conforming – and that’s clearly not the case. Having your kids out in the woods – as most of you did today – is not, as the Twitterati had it, ‘opening the floodgates’ to laissez-faire schooling. They always tell you that parents are the primary educators, not schools – but only if you do as you’re told.

7. What else can you do?

I’ve been enormously impressed by the cogent arguments of parents in the media today, despite all the guilt-tripping and name-calling. All the stereotypes have been trotted out: you’re a bunch of middle-class tree-hugging activists – at least according to ‘other’ middle-class activists (the ones who hold opposing political views), but no matter. The education community has, for decades, asked for greater parental engagement in learning, so it’s great that you’ve made your case clear. Incidentally, your numbers would have been significantly swelled were it not for the fact that school is seen, first and foremost, as a free child-minding service, so a future protest might need to tap into those whose work commitments prevented more active participation today.

Don’t be deterred by the lack of overt support from school leaders – they can’t be seen to advocate ‘bunking off’, but the vast majority of them share your concerns. And it’s been great that you have never criticised teachers, or schools, in your campaign. They’re with you and hope that you make an impact. Nor have you ever fallen in to the neocon trap of being seen to be against testing. You’re simply again too much testing, and at too high a stake.

While I was listening to the media representation of your views, I was digging up plants that could have been weeds, or vice versa. I was reminded of the great John Holt’s gardening analogy of testing. It’s as true today as it was in the 1970s: no one is against testing, but too much of it is like a gardener frequently digging up a plant to see how well its roots are developing.

Keep your parental campaign going – you’re the only constituency that government will listen to.

April 20, 2016

The Pirates And The Bean Counters

At exactly the same time today as UK Prime Minister, David Cameron, was telling the House of Commons that the best option for raising standards was to make all schools government monitored academies, I was sitting with a bunch of educators who were living proof that he’s flat-out wrong.

At exactly the same time today as UK Prime Minister, David Cameron, was telling the House of Commons that the best option for raising standards was to make all schools government monitored academies, I was sitting with a bunch of educators who were living proof that he’s flat-out wrong.

I go to lots of education conferences, mainly because I’m asked to keynote at them. Truth be told, if I have a day off, the last thing I feel like doing is going to an education conference. But today, I attended a conference as a participant, and I wouldn’t have missed it for the world.

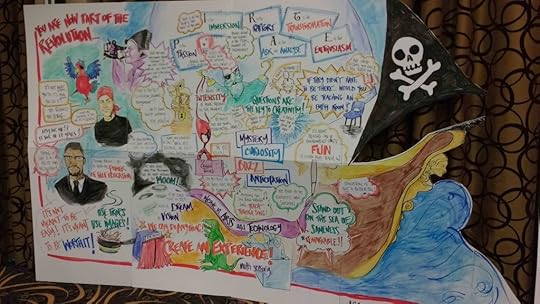

The EOS Conference set

The EOS Alliance held their annual conference today. It was unlike any conference I’d been to. When I keynoted at the inaugural EOS conference, I blogged that it felt like several hundred educators were plugged into the mains, such was the electricity in the room – today was that, on steroids.

For one thing, the space was unlike any other conference space I’ve seen – completely immersive and in keeping with the EOS desire to make classrooms entirely immersive spaces. The whole event had a piracy theme, so it was a happy coincidence (or not) that their opening keynote was conducted by Dave Burgess, of Teach Like A Pirate fame.This was one of the most inspiring and engaging presentations I’ve ever seen. Dave spoke passionately about the maverick, rebellious nature of pirates, and it’s a sad indictment of our school system today that astoundingly great teachers like Dave are dismissed as ‘mavericks’.

Graphic Note-taking from creativeconnection.co.uk

Dave brings his experience as a magician to the classroom and the conference venue alike, and that’s because, as he says, teachers should include their own passions in their teaching. His just happens to be magic. I was making furious notes as he spoke, some of which were things like ‘brilliant, charismatic, but how transferrable is this?’ As if he was reading my notes, he then demolished my reservations by arguing that: a) he worked bloody hard, failing often, to be this charismatic; b) the myth of the blinding flash of light means that some teachers excuse themselves, from the kind of magic Dave was creating, by saying “I’m not creative”. His dismissal of this was to say that we won’t see creative ideas for teaching – and therefore get over our creative phobia – unless we think it’s important. Another brilliant analogy he used was to liken teaching to a great barbecue. Content = the meat, but the magic happens in the use of heat, the marinade, the accompaniments. Too many teachers throw the raw meat (content) at students and say ‘Eat it’.

That was the opening – the closing presentation was provided by Mark Stevenson who brilliantly showed how the future is going to be so radically different to what we’ve experienced so far (pilotless planes, abundant cheap energy, home 3D printing of medicines, reverse desertification, for starters) that to think we can continue to teach kids the way we’ve always done is farcical. The urgency of the breakdown of most of our infrastructures – capitalism, party politics, fossil fuel production, economic, social and food distribution – require tomorrow’s citizens/today’s students to display creativity and problem-solving on an unprecedented scale. And we’re arguing about the best way to teach times tables?

Between those two keynotes were a range of workshops where teachers were sharing their classroom innovations in a genuine spirit of openness, reciprocity and mutual. benefit. No-one mentioned league tables, standardised testing or literacy and numeracy levels, because they all understood there was a much bigger game in play. As Dave Burgess said, teachers real effectiveness can only be measured through generations, not test scores. Government – and some academy chains I’ve worked with – only measure teachers effectiveness by the most recent set of exam results. How can that possibly be in the best long-term interests of our students?

And yet, that’s precisely what our Prime Minister was dictating was going to happen, while 400 committed educators, with vast aggregated experience, were metaphorically ‘walking the plank’.

EOS CEO Carl Jarvis – Sometimes he wears a suit…

The strap-line of the EOS conference was ‘There’s a storm coming’. Well, actually, there are two: the first is the triumph of the neoliberal agenda in education, so that all schools are forced to compete, in a free-marketplace, tested against a set of standards that bear no relation to the other approaching storm. That one says that we’re in a global scenario where, in the words of Mark Stevenson, ‘all bets are off’, and we’d better place a premium on finding solutions collaboratively, not competitively, so that we grow the innovators of the future.

The sheer arrogance of this government, dismissing the assembled expertise of educators, academics and local authority experts – who’ve spent their whole lives grappling with these problems – as the irrelevant squealing of ‘the blob’, is gob-smacking. Our Prime Minister decreed today that, structurally, there’s a one-size-fits-all solution that’s going to be handed down by government – so you’d better ‘eat it’.

Well, I’m sorry, but it doesn’t have to be that way. The EOS Alliance, and their counterparts, prove that schools can voluntarily come together, to find ways of preparing our kids for a radically altered future. Can learn from each other cheaply, socially, with a sense of fun and mutual respect. Can undertake peer review of each other’s practices, so that teaching and learning is transformed. Can welcome complexity, and divergent thinking, so that the best interests of their students can be served. Can see that the prime focus of education isn’t to drill experts in test-taking, but to build citizens who want to make the world a better place.

Being a pirate is a risky business, compared to carrying out the orders of bean-counters, but it’s not only way more fun, it’s essential to our student’s futures. If you wanted evidence of the compelling nature of the counter-movement, bubbling away under the gaze of the government, it’s this: 75% of tickets for next years EOS conference were sold by the end of this years. Get a ticket quick – join the mutiny!

An Open Letter To David Cameron On Forced Academisation

I’ve just seen your performance at today’s Prime Minister’s Questions where you defended the government’s decision to force all schools to become academies. I notice you didn’t say that all schools will be forced to join multi-academy trusts (MATs) – a subtle but important distinction. As you know, there is considerable concern that the education white paper’s reference to MATs – effectively abolishing single school academies – smacks of ‘pre-privatisation’ and will usher in the march of the robber barons, existing chains becoming rapidly larger, and mergers happening to ensure that there are a manageable number of trusts for your department to deal with. (Sir Michael Wilshaw recently felt that many of the existing large chains are performing worse than the local authorities they replaced, but that view was dismissed by your department – the wrong expert I guess).

However, you asked today that we consider the ‘evidence’ that schools do better when they become academies. Well, according to your Education Select Committee’s inquiry, published as recently as January 2016, there was no clear evidence that academies raised standards. The select committee also expressed concerns about conflicts of interest in governance of academies, a lack of transparency and inadequate oversight, thus echoing Sir Michael Wilshaw’s complaints. The NFER report of 2013 also found no conclusive evidence that academies do better than non-academies in GSCE results. There appears to be no clear evidence that MATs (your preferred solution) do better than either individual academies, or non-academies. OFTED (as you know you prevented OFSTED from inspecting academy chins) reporting that ‘In two of the largest chains, at least half of the schools were rated “requires improvement” or “inadequate”’.

If all that weren’t enough, the recent local schools network analysis also rubbished your ‘evidence’,

All of this suggests at best, you’re taking a selective view of the ‘evidence’, or at worst, simply ignoring evidence that doesn’t suit your policy direction. Today, however, you asked us all to be idiots, by claiming that, of the converter academies, “88% of them are either good or outstanding”, while ignoring the fact that 100% of ’converter’ academies had to judged as at least ‘good’, with outstanding features, before they could qualify for conversion. Does this mean that 12% have now become worse since becoming academies? In today’s world a dodgy ‘fact’ is immediately checked and within hours this – how shall we put it – ‘inconsistency’ was quickly revealed in the media.

You seem to be deaf to all of the voices objecting to the many successful schools and local authorities (and there are some, you know) being obliged to go through the expensive process of conversion when they neither want to, nor need to.

So be it. But at least have the grace to admit that the policy of ‘what works’ and evidence-based policy making is now over. What we appear to have in its place is the opposite – ‘policy-based evidence making’ – in order to support nothing more than ideology.

April 17, 2016

The Neoliberal Paradox: Forced Freedom For Schools

These are confusing times for educators. Two weeks ago I arranged for the UK premiere of a much-debated film about the kinds of schools we need for the future, ‘Most Likely To Succeed’. The film argues that the skills our kids will need in a highly automated, freelance/contracted, future workforce, can’t be developed through a standardised drilling-and-killing model of teaching and learning. We had a good mix of educators and concerned parents in the audience, and the discussion afterwards largely revolved around the knowledge-skills tension: corporates increasingly seem to demand higher-order skills, but schools are being pressured into training students in test-taking. And are the two mutually exclusive?

These are confusing times for educators. Two weeks ago I arranged for the UK premiere of a much-debated film about the kinds of schools we need for the future, ‘Most Likely To Succeed’. The film argues that the skills our kids will need in a highly automated, freelance/contracted, future workforce, can’t be developed through a standardised drilling-and-killing model of teaching and learning. We had a good mix of educators and concerned parents in the audience, and the discussion afterwards largely revolved around the knowledge-skills tension: corporates increasingly seem to demand higher-order skills, but schools are being pressured into training students in test-taking. And are the two mutually exclusive?

Coming on the back of the recently published Education White Paper in England, there seems to be a fierce protest from educators about the direction of travel (forced academisation, increased testing, diminution of parental representation on governing bodies), yet relative quiet from parents themselves. Is this because they’re generally content and don’t see education as a key issue, or are the issues simply too confusing?

Some critics of the government have seen the compulsory centralising of schools, directly under DoE supervision, as a Stalinist ploy, while others have seen it as the ‘pre-privatisation’ stage in a bigger neoliberal conspiracy. Others are determined to see the positives. Alistair Falk, Director of Partnerships at Birmingham Education Partnership, in a recent post, urges us all to see the prospect of every school being part of a Multi-Academy Trust (for that is what’s being proposed, not all schools becoming academies, but all becoming part of a MAT) as an opportunity: no more national curriculum constraints, no more local authority control, a chance to re-design schooling.

Like I say, it’s all a bit confusing. One thing seems certain: these steps aren’t being taken because there’s overwhelming evidence that the ‘free-marketisation’ of schooling provides better outcomes, because that clear-cut evidence (the kind that would warrant such a drastic move) just isn’t there. Indeed, Laura McInerney (@miss_mcinerney) recently reported on a damming study on 160 forced academies (forced, because they were deemed to be ‘failing’). 21 of them brought in so-called ‘super-heads’ to turn around exam results. The super-heads followed a by-now familiar strategy: focus absolutely on English and Maths; kick out badly-behaving students; move great teachers to work with year 11 (exam year) students; don’t enter low-ability students in exams, or persuade parents to home-school them. The longer-term results show a striking consistency: a short-term improvement in test scores of around 9%, but once the super-head had left, a 6-9% dip in scores. Schools without super-heads showed, in general, only incremental improvement, but no dip.

Like I say, it’s all a bit confusing. One thing seems certain: these steps aren’t being taken because there’s overwhelming evidence that the ‘free-marketisation’ of schooling provides better outcomes, because that clear-cut evidence (the kind that would warrant such a drastic move) just isn’t there. Indeed, Laura McInerney (@miss_mcinerney) recently reported on a damming study on 160 forced academies (forced, because they were deemed to be ‘failing’). 21 of them brought in so-called ‘super-heads’ to turn around exam results. The super-heads followed a by-now familiar strategy: focus absolutely on English and Maths; kick out badly-behaving students; move great teachers to work with year 11 (exam year) students; don’t enter low-ability students in exams, or persuade parents to home-school them. The longer-term results show a striking consistency: a short-term improvement in test scores of around 9%, but once the super-head had left, a 6-9% dip in scores. Schools without super-heads showed, in general, only incremental improvement, but no dip.

The super-head strategy is more or less what we see with corporations whose profits fall: a ‘fixer’ CEO is brought-in to satisfy shareholder anxiety; if he (because it’s nearly always a he) succeeds then he gets lured away to a better paid position, and the cycle starts all over again.

Except schools aren’t businesses and they don’t have shareholders – yet.

Let me make my position clear. I don’t believe that having an ideological position on education is helpful to the prospects of our kids. I’ve had Twitter maulings for saying that I thought that an aim of the government instigated ‘free schools’ – to bring diversity and innovation to school models – was laudable. But, increasingly, I feel that the reforms of the past 3 years are not based on ‘what works’, but on an ideology of neoliberalisation. There are two classic strategies of neoliberalists: never let a good crisis go to waste, and exercise ‘creative destruction’, so that the former system can never be revived. For the former, you only have to read Naomi Klein’s ‘The Shock Doctrine’ to see that the economic crisis provided the perfect excuse (via austerity cuts to public services), to remove local accountability for schools. As for ‘creative destruction’ – well, if the current government collapsed overnight, it would take decades to restore a more democratic framework for schools, if even possible. So, that’s two boxes ticked.

Neoliberalism advocates privatisation, deregulation, competition and a ‘free market’, which begs two questions: will we soon have a free market for schools, and does any of this matter, anyway?

It maybe wouldn’t be such a bad thing if there really was a free market for schools – defined by each school having an equal chance, and equal funding. But the initial aim of free schools appears to have been distorted by government ideology: Laura Mcinnerney again (boy, has she been busy lately…) has fought a one-woman battle to have transparency over why some free schools have been approved while others were rejected. This post highlights a very disturbing opacity.

And does it matter, so long as standards and test scores improve? Well, setting aside the recent doubt of the schools inspector, that multi-academy trusts performed no better than the worst performing local authorities they were meant to replace, yes it does. The neoliberal bit that seems to be missing in current education policy is the ‘laissez-faire’ part. The schools minister, Nick Gibb, has made his views clear – in total opposition to the arguments made in ‘Most Likely To Succeed’, he wants to see traditional teaching of facts to replace ‘joyless skills’. So, we can expect to see MATs (who will be directly monitored by the Department for Education, remember) being coerced into changing their teaching. Leaders of schools advocating ‘progressive’ teaching – many of whom lead schools judged as ‘outstanding’ are already being personally abused on social media, and some have even had their families threatened.

So, whatever the declared intentions of structural reforms, there’s no question that it’s bound to have an effect on teaching and learning – and will be driven by a testing obsession which benefits no one but the profits of education businesses.

I’ll end with the two questions which were left hanging at the showing of ‘Most Likely’ and ask you for your views: Is the Education White Paper primarily an attempt to remove democratic accountability from schooling by privatising it (the neoliberal conspiracy)? And if parents oppose the future plans what can they do about it?

March 20, 2016

Why ‘What Works’ Doesn’t

There’s not a day goes by on Twitter without educators arguing over their preferred pedagogies, and which one has ‘proven’ to be the most ‘effective’. I use inverted commas because proof, absolute proof, is a slippery concept. And the interpretations of effectiveness are equally complex – most measures of effectiveness focus upon academic performance: crudely, does the given innovation improve test scores? Let’s put aside the question of whether, in a world where employers and colleges are increasingly disregarding terminal exam performances, and students ability to regurgitate content, this is the most commonly cited measure of effectiveness. The other key question lies in what’s known as the ‘experimental science’ model.

Most new educational theories are developed using the experimental science model, where an external academic – or sets of academics – set up pilots using small groups of schools. These pilot programmes are often sold as ‘evidence-based’ randomised control trials, where variations are minimised (RCTs hate variations) in order to replicate laboratory conditions. Now that RCTs are all the rage in education, schools are increasingly not fashioning their own innovations.

Instead, they’re told what they need to do by regulatory authorities based on experimental science research initiatives. The exhortation goes like this: “we’ve worked out ‘what works’ – now you need to do it”. The problem is ‘what works’ doesn’t – or rather it works, but only if your school happens to share most of the same contexts and conditions that were seen in the original pilot. And that’s the point: schools exist within messy, complex and various contexts. ‘What works’ silver bullets frequently turn out to be duds when scale-up happens. And it is often in scale-up stage, when less than impressive results occur, that two opposing educators can cite completely contradictory evidence. Or two opposing politicians citing the evidence that suits their world view, hence the phenomenon of ‘policy-based evidence making’ (and not what they claim to be ‘evidence-based policy-making).

So, if the experimental science method is flawed, is there any alternative? Thankfully, yes. And the good news is that it puts schools back in the driving seat when it comes to ‘getting better at getting better’.

We’ve recently begun training school leaders and teachers in a new, exciting, approach to building a culture of adult learning and a culture of continuous improvement. Our excitement stems from the possibility – and it’s so new that it’s only that – of this approach unlocking the key to the holy grail of educational reform: self-improving schools (and teachers). It’s called Improvement Science.

What is Improvement Science?