Jennifer Lauck's Blog, page 17

February 14, 2012

Listen in: Valentine's Teleseminar

Hope Edelman, a dear friend and a terrific supporter of my work, joined us for an hour long conversation about how to live the writing life and support yourself with your craft.

Hope Edelman, a dear friend and a terrific supporter of my work, joined us for an hour long conversation about how to live the writing life and support yourself with your craft. Key words: Commitment, adaptability & passion.

Hope is abundant in all of these qualities. If you are a subscriber to this site, you will have access to the full link but if you are not yet on the site, please take a moment to sign up HERE and get the full link.

Published on February 14, 2012 16:25

February 13, 2012

Writing Tip #21: Including Nature

Writing about nature is a challenge. Just how do we do this, and we must do this because the natural world is part of our lived experience, without being boring or being bored? While the writer who waxes on and on about the natural world does run the risk or boring the reader, to "brush stroke" nature in your writing in a simplistic, fast, short hand way deprives the reader of the ground that is nature and this tact also deprives the writer of latching onto the many metaphorical opportunities that nature presents. The point? Don't rush as you work the natural world into your experience. Incorporate nature with generosity of detail and let it reveal the depths of your own story to you. And remember to infuse the experience of nature with a human consciousness that moves through it, observes it and is transformed by it.

Writing about nature is a challenge. Just how do we do this, and we must do this because the natural world is part of our lived experience, without being boring or being bored? While the writer who waxes on and on about the natural world does run the risk or boring the reader, to "brush stroke" nature in your writing in a simplistic, fast, short hand way deprives the reader of the ground that is nature and this tact also deprives the writer of latching onto the many metaphorical opportunities that nature presents. The point? Don't rush as you work the natural world into your experience. Incorporate nature with generosity of detail and let it reveal the depths of your own story to you. And remember to infuse the experience of nature with a human consciousness that moves through it, observes it and is transformed by it. Prompt: Can you articulate what your vision of nature is? If the outdoors draws you and brings you a special kind of knowledge or contentment, can you bring into words what that connection consists of? Can you think of a time when you went into a natural setting to make a difficult decision, work something out in your mind, or somehow come to feel more "yourself"? What led you to that place? Did it help you in the way you wanted?

REMEMBER, as you articulate your sense of nature in language, that there's nothing else (save love) that so easily lends itself to cliché. Tranquil brooks, awesome mountains, trilling birds—these are the stuff of hackneyed writers. Make your descriptions fresh, interesting, and original. (From Tell it Slant, by Brenda Miller & Suzanne Paola)

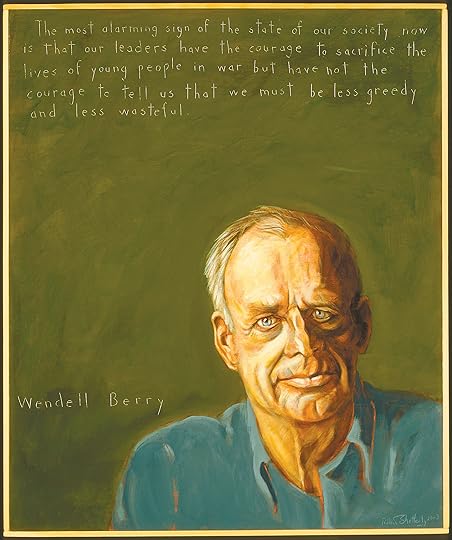

Example: From Wendell Berry's "An Entrance to the Woods."

A farmer, environmentalist, teacher, and writer, Wendell Berry was born in Kentucky in 1934. He is also a critic of technology and government. After living in both New York and California and teaching at New York University in the 1960s he returned to Kentucky, where he now lives, farms, and teaches at the University of Kentucky.

On a fine sunny afternoon at the end of September I leave my work in Lexington and drive east on I-64 and the Mountain Parkway. When I leave the Parkway at the little town of Pine Ridge I am in the watershed of the Red River in the Daniel Boone National Forest. From Pine Ridge I take Highway 715 out along the narrow ridgetops, a winding tunnel through the trees. And then I turn off on a Forest Service Road and follow it to the head of a foot trail that goes down the steep valley wall of one of the tributary creeks. I pull my car off the road and lock it, and lift on my pack.

It is nearly five o'clock when I start walking. The afternoon is brilliant and warm, absolutely still, not enough air stirring to move a leaf. There is only the steady somnolent trilling of insects, and now and again in the woods below me the cry of a pileated woodpecker. Those, and my footsteps on the path, are the only sounds.

From the dry oak woods of the ridge I pass down into the rock. The foot trails of the Red River Gorge all seek these stony notches that little streams have cut back through the cliffs. I pass a ledge overhanging a sheer drop of the rock, where in a wetter time there would be a waterfall. The ledge is dry and mute now, but on the face of the rock below are the characteristic mosses, ferns, liverwort, meadow rue. And here where the ravine suddenly steepens and narrows, where the shadows are long-lived and the dampness stays, the trees are different. Here are beech and hemlock and poplar, straight and tall, reaching way up into the light. Under them are evergreen thickets of rhododendron. And wherever the dampness is there are mosses and ferns. The faces of the rock are intricately scalloped with veins of ironstone, scooped and carved by the wind.

Finally from the crease of the ravine I am following there begins to come the trickling and splashing of water. There is a great restfulness in the sounds these small streams make; they are going down as fast as they can, but their sounds seem leisurely and idle, as if produced like gemstones with the greatest patience and care.

A little later, stopping, I hear not far away the more voluble flowing of the creek. I go on down to where the trail crosses and begin to look for a camping place. The little bottoms along the creek here are thickety and weedy, probably having been kept clear and cropped or pastured not so long ago. In the more open places are little lavender asters, and the even smaller-flowered white ones that some people call beeweed or farewell-summer. And in low wet places are the richly flowered spikes of great lobelia, the blooms an intense startling blue, exquisitely shaped. I choose a place in an open thicket near the stream, and make camp.

It is a simple matter to make camp. I string up a shelter and put my air mattress and sleeping bag in it, and I am ready for the night. And supper is even simpler, for I have brought sandwiches for this first meal. In less than an hour all my chores are done. It will still be light for a good while, and I go over and sit down on a rock at the edge of the stream.

And then a heavy feeling of melancholy and lonesomeness comes over me. This does not surprise me, for I have felt it before when I have been alone at evening in wilderness places that I am not familiar with. But here it has a quality that I recognize as peculiar to the narrow hollows of the Red River Gorge. These are deeply shaded by the trees and by the valley walls, the sun rising on them late and setting early; they are more dark than light. And there will often be little rapids in the stream that will sound, at a certain distance, exactly like people talking. As I sit on my rock by the stream now, I could swear that there is a party of campers coming up the trail toward me, and for several minutes I stay alert, listening for them, their voices seeming to rise and fall, fade out and lift again, in happy conversation. When I finally realize that it is only the sound the creek is making, though I have not come here for company and do not want any, I am inexplicably sad.

These are haunted places or at least it is easy to feel haunted in them, alone at nightfall. As the air darkens and the cool of the night rises, one feels the immanence of the wraiths of the ancient tribesmen who used to inhabit the rock houses of the cliffs; of the white hunters from east of the mountains; of the farmers who accepted the isolation of these nearly inaccessible valleys to crop the narrow bottoms and ridges and pasture their cattle and hogs in the woods; of the seekers of quick wealth in timber and ore. For though this is a wilderness place, it bears its part of the burden of human history. If one spends much time here and feels much liking for the place, it is hard to escape the sense of one's predecessors. If one has read of the prehistoric Indians whose flint arrowpoints and pottery and hominy holes and petroglyphs have been found here, then every rock shelter and clifty spring will suggest the presence of those dim people who have disappeared into the earth. Walking along the ridges and the stream bottoms, one will come upon the heaped stones of a chimney or the slowly filling depression of an old blooming in a thicket that used to be a dooryard. Wherever the land is level enough there are abandoned fields and pastures. And nearly always there is the evidence that one follows in the steps of the loggers.

That sense of the past is probably one reason for the melancholy that I feel. But I know that there are other reasons.

One is that, though I am here in body, my mind and my nerves too are not yet altogether here. We seem to grant to our high –speed roads and our airlines the rather thoughtless assumption that people can change places as rapidly as their bodies can be transported. That, as my own experience keeps proving to me, is through traffic to the freeway, and then for a solid hour or more I drove sixty or seventy miles an hour, hardly aware of the country I was passing through, because one may drive over it at seventy miles per hour without any concession whatsoever to one's whereabouts. One might as well be flying. Though one is in Kentucky one is not experiencing Kentucky; one is experiencing the highway, which might be in nearly any hill country east of the Mississippi.

Once off the freeway, my pace gradually slowed, as the roads became progressively more primitive, from seventy miles an hour to a walk. And now, here at my camping place, I have stopped altogether. But my mind is still keyed to seventy miles an hour. And having come here so fast, it is still busy with the work I am usually doing. Having come here by the freeway, my mind is not so fully here as it would have been if I had come by the crookeder, slower state roads; it is incalculably farther away than it would have been if I had come all the way on foot, as my earliest predecessors came. When the Indians and the first white hunters entered and experienced fully everything between here and their starting place, and so the transition was gradual and articulate in their consciousness. Our senses, after all, were developed to function at foot speeds; and the transition from foot travel to motor travel, in terms of evolutionary time, has been abrupt. The faster one goes, the more strain there is on the senses, the more they fail to take in, the more confusion they must tolerate or gloss over—and the longer it takes to bring the mind to a stop in the presence of anything. Though the freeway passes through the very heart of this forest, the motorist remains several hours' journey by foot from what is living at the edge of the right-of-way.

But I have not only come to this strangely haunted place in a short time and too fast, I have in that move made an enormous change: I have departed from my life as I am used to living it, and have come into the wilderness. It is not fear that I feel; I have learned to fear the everyday events of human history much more than I fear the everyday occurrences of the woods; in general, I would rather trust myself to the woods than to any government that I know of. I feel, instead, an uneasy awareness of severed connections, of being cut off from all familiar places and of being a stranger where I am. What is happening at home? I wonder, and I know I can't find out very easily or very soon.

Even more discomforting is a pervasive sense of unfamiliarity. In the places I am most familiar with—my house, or my garden, or even the woods near home that I have walked in for years—I am surrounded by associations; everywhere I look I am reminded of my history and my hopes; even unconsciously I am comforted by any number of proofs that my life on the earth is an established and a going thing. But I am I this hollow for the first time in my life. I see nothing that I recognize. Everything looks as it did before I came, as it will when I am gone. When I look over at my little camp I see how tentative and insignificant it is. Lying there in my bed in the dark tonight, I will be absorbed in the being of this place, invisible as a squirrel his nest.

Uneasy as this feeling is, I know it will pass. Its passing will produce a deep pleasure in being here. And I have felt it often enough before that I have begun to understand something of what it means:

Nobody knows where I am. I don't know what is happening to anybody else in the world. While I am here I will not speak, and will have no reason or need for speech. It is only beyond this lonesomeness for the places I have come from that I can reach the vital reality of a place such as this. Turning toward this place, I confront a presence that none of my schooling and none of my usual assumptions have prepared me for: the wilderness, mostly unknowable and mostly alien, that is the universe. Perhaps the most difficult labor for my species is to accept its limits, its weakness and ignorance. But here I am. This wild place where I have camped lies within an enormous cone widening from the center of the earth out across the universe, nearly all of it a mysterious wilderness in which the power and the knowledge of men count for nothing. As long as its instruments are correct and its engines run, the airplane now flying through this great cone is safely within the human freehold; its behavior is as familiar and predictable to those concerned as the inside of a man's living room. But let its instruments or its engines fail, and at once it enters the wilderness where nothing is foreseeable. And these steep narrow hollows, these cliffs and forested ridges that lie below, are the antithesis of flight.

Wilderness is the element in which we live encased in civilization, as a mollusk lives in his shell in the sea. It is a wilderness that is beautiful, dangerous, abundant, oblivious of us, mysterious, never to be conquered or controlled or second-guessed, or known more than a little. It is a wilderness that for most of us most of the time is kept out of sight, camouflaged, by the edifices and the busyness and bothers of human society.

And so, coming here, what I have done is strip away the human façade that usually stands between me and the universe, and I see more clearly where I am. What I am able to ignore much of the time, but find undeniable here, is that all wildernesses are one: there is profound joining between this wild stream deep in one of the folds of my native country and the tropical jungles, the tundras of the north, the oceans and the deserts. Alone here, among the rocks and the trees, I see that I am alone also among the stars. A stranger here, unfamiliar with my surroundings, I am aware also that I know only in the most relative terms my whereabouts within the black reaches of the universe. And because the natural processes are here so little qualified by anything human, this fragment of the wilderness is also joined to other times; there flows over it a nonhuman time to be told by the growth and death of the forest and the wearing of the stream. I feel drawing out beyond my comprehension perspectives from which the growth and the death of a large poplar would seem as continuous and sudden as the raising and the lowering of a man's hand, from which men's history in the world, their brief clearing of the ground, will seem no more than the opening and shutting of an eye.

And so I have came here to enact—not because I want to but because, once here, I cannot help it—the loneliness and the humbleness of my kind. I must see in my flimsy shelter, pitched here for two nights, the transience of capitols and cathedrals. In growing used to being in this place, I will have to accept a humbler and a truer view of myself than I usually have.

A man enters and leaves the world naked. And it is only naked—or nearly so—that he can enter and leave the wilderness. If he walks, that is; and if he doesn't walk it can hardly be said that he has entered. He can bring only what he can carry—the little that it takes to replace for a few hours or a few days an animal's fur and teeth and claws and functioning instincts. In comparison to the usual traveler with his dependence on machines and highways and restaurants and motels—on the economy and the government, in short—the man who walks into the wilderness is naked indeed. He leaves behind his work, his household, his duties, his comforts—even, if he comes alone, his words. He immerses himself in what he is not. It is a kind of death.

The dawn comes slow and cold. Only occasionally, somewhere along the creek or on the slopes above, a bird sings. I have not slept well, and I waken without much interest in the day. I set the camp to rights, and fix breakfast, and eat. The day is clear, and high up on the points and ridges to the west of my camp I can see the sun shining on the woods. And suddenly I am full of an ambition: I want to get up where the sun is; I want to sit still in the sun up there among the high rocks until I can feel its warmth in my bones.

I put some lunch into a little canvas bag, and start out, leaving my jacket so as not to have to carry it after the day gets warm. Without my jacket, even climbing, it is cold in the shadow of the hollow, and I have a long way to go to get to the sun. I climb the steep path up the valley wall, walking rapidly, thinking only of the sunlight above me. It is as though I have entered into a deep sympathy with those tulip poplars that grow so straight and tall out of the shady ravines, not growing a branch worth the name until their heads are in the sun. I am so concentrated on the sun that when some grouse flush from the undergrowth ahead of me, I am thunderstruck; they are already planning down into the underbrush again before I can get my wits together and realize what they are.

The path zigzags up the last steepness of the bluff and then slowly levels out. For some distance it follows the backbone of a ridge, and then where the ridge is narrowest there is a great slab of bare rock lying full in the sun. This is what I have been looking for. I walk out into the center of the rock and sit, the clear warm light falling unobstructed all around. As the sun warms me I begin to grow comfortable not only in my clothes, but in the place and the day. And like those light-seeking poplars of the ravines, my mind begins to branch out.

Southward, I can hear the traffic on the Mountain Parkway, a steady continuous roar—the corporate voice of twentieth-century humanity, sustained above the transient voices of its members. Last night, except for an occasional airplane passing over, I camped out of reach of the sounds of engines. For long stretches of time I heard no sounds but the sounds of the woods.

Near where I am sitting there is an inscription cut into the rock:

A · J · SARGENT

fEB · 24 · 1903

Those letters were carved there more than sixty-six years ago. As I look around me I realize that I can see no evidence o f the lapse of so much time. In every direction I can see only narrow ridges and narrow deep hollows, all covered with trees. For all that can be told from this height by looking, it might still be 1903—or, for that matter, 1803 or 1703, or 1003. Indians no doubt sat here and looked over the country as I am doing now; the visual impression is so pure and strong that I can almost imagine myself one of them. But the insistent, the over-whelming, evidence of the time of my own arrival is in what I can hear—that roar of the highway of there in the distance. In 1903 the continent was still covered by a great ocean of silence, in which the sounds of machinery were scattered at wide intervals of time and space. Here, in 1903, there were only the natural sounds of the place. On a day like this, at the end of September, there would have been only the sounds of a few faint crickets, a woodpecker now and then, now and then the wind. But today, two-thirds of a century later, the continent is covered by an ocean of engine noise, in which silences occur only sporadically and at wide intervals.

From where I am sitting in the midst of this island of wilderness, it is as though I am listening to the machine of human history—a huge flywheel building speed until finally the force of its whirling will break it in pieces, and the world with it. That is not an attractive thought, and yet I find it impossible to escape, for it has seemed to me for years now that the doings of men no longer occur within nature, but that the natural places which the human economy has so far spared now survive almost accidentally within the doings of men. This wilderness of the Red River now carries on its ancient processes within the human climate of war and waste and confusion. And I know that the distant roar of engines, though it may seem only to be passing through this wildereness, is really bearing down upon it. The machine is running now with a speed that produces blindness—as to the driver of a speeding automobile the only thing stable, the only thing not a mere blur on the edge of the retina, is the automobile itself—and the blindness of a thing with power promises the destruction of what cannot be seen. That roar of the highway is the voice of the American economy; it is sounding also wherever strip mines are being cut in the steep slopes of Appalachia, and wherever cropland is being destroyed to make roads and suburbs, and wherever rivers and marshes and bays and forests are being destroyed for the sake of industry or commerce.

No. Even here where the economy of life is really an economy—where the creation is yet fully alive and continuous and self-enriching, where whatever dies enters directly into the life of the living—even here one cannot fully escape the sense of an impending human catastrophe. One cannot come here without the awareness that this is an island surrounded by the machinery and the workings of an insane greed, hungering for the world's end—that ours is a "civilization" of which the work of no builder or artist is symbol, nor the life of any good man, but rather the bulldozer, the poison spray, the hugging fire of napalm, the cloud of Hiroshima.

Though from the high vantage point of this stony ridge I see little hope that I will ever live a day as an optimist, still I am not desperate. In fact, with the sun warming me now, and with the whole day before me to wander in this beautiful country, I am happy. A man cannot despair if he can imagine a better life, and if he can enact something of its possibility. It is only when I am ensnarled in the meaningless ordeals and the ordeals of meaninglessness, of which our public and political life is now so productive, that I lose the awareness of something better, and feel the despair of having come to the dead end of possibility.

Today, as always when I am afoot in the woods, I feel the possibility, the reasonableness, the practicability of living in the world in a way that would enlarge rather than diminish the hope of life. I feel the possibility of a frugal and protective love for the creation that would be unimaginably more meaningful and joyful than our present destructive and wasteful economy. The absence of human society, that made me so uneasy last night, now begins to be a comfort to me. I am afoot in the woods. I am alive in the world, this moment, without the help or the interference of any machine. I can move without reference to anything except the lay of the land and the capabilities of my own body. The necessities of foot travel in this steep country have stripped away all superfluities. I simply could not enter into this place and assume its quiet with all the belongings of a family man, property holder, etc. For the time, I am reduced to my irreducible self. I feel the lightness of body that a man must feel who has just lost fifty pounds of fat. As I leave the bare expanse of the rock and go in under the trees again, I am aware that I move in the landscape as one of its details.

Walking through the woods, you can never see far either ahead or behind, so you move without much of a sense of getting anywhere or of moving at any certain speed. You burrow through the foliage in the air much as a mole burrows through the roots in the ground. The views that open out occasionally from the ridges afford a relief a recovery of orientation, that they could never give as mere "scenery," looked at from a turnout at the edge of a highway.

The trail leaves the ridge and goes down a ravine into the valley of a creek where the night chill has stayed. I pause only long enough to drink the cold clean water. The trail climbs up onto the next ridge.

It is the ebb of the year. Though the slopes have not yet taken on the bright colors of the autumn maples and oaks, some of the duller trees are already shedding. The foliage has begun to flow down the cliff faces and the slopes like a tide pulling back. The woods is mostly quiet, subdued, as if the pressure of survival has grown heavy upon it, as if above the growing warmth of the day the cold of winter can be felt waiting to descend.

At my approach a big hawk flies off the low branch of an oak and out over the treetops. Now and again a nuthatch hoots, off somewhere in the woods. Twice I stop and watch an ovenbird. A few feet ahead of me there is a sudden movement in the leaves, and then quiet. When I slip up and examine the spot there is nothing to be found. Whatever passed there has disappeared, quicker than the hand that is quicker than they eye, a shadow fallen into a shadow.

In the afternoon I leave the trail. My walk so far has come perhaps three-quarters of the way around a long zigzagging loop that will eventually bring me back to my starting place. I turn down a small unnamed branch of the creek where I am camped, and I begin the loveliest part of the day. There is nothing here resembling a trail. The best way is nearly always to follow the edge of the stream, stepping from one stone to another. Crossing back and forth over the water, stepping on or over rocks and logs, the way ahead is never clear for more than a few feet. The stream accompanies me down, threading its way under boulders and logs and over little falls and rapids. The rhododendron are the great dark heads of the hemlocks. The streambanks are ferny and mossy. And through this green tunnel the voice of the stream changes from rock to rock; subdued like all the other autumn voices of the woods, it seems sunk in a deep contented meditation on the sounds of l.

The water in the pools is absolutely clear. If it weren't for the shadows and ripples you would hardly notice that it is water; the fish would seem to swim in the air. As it is, where there is no leaf floating, it is impossible to tell exactly where the plane of the surface lies. As I walk up on a pool the little fish dart every which way out of sight. And then after I sit still a while, watching, they come out again. Their shadows flow over the rocks and leaves on the bottom. Now I have come into the heart of the woods. I am far from the highway and can hear no sound of it. All around there is a grand deep autumn quiet, in which a few insects dream their summer songs. Suddenly a wren sings way off in the underbrush. A redbreasted nuthatch walks, hooting, headfirst down the trunk of a walnut. An ovenbird walks out along the limb of a hemlock and looks at me, curious. The little fish soar in the pool, turning their clean quick angles, their shadows seeming barely to keep up. As I lean and dip my cup in the water, they scatter. I drink, and go on.

When I get back to camp it is only the middle of the afternoon or a little after. Since I left in the morning I have walked something like eight miles. I haven't hurried—have mostly poked along, stopping often and looking around. But I am tired, and coming down the creek I have got both feet wet. I find a sunny place, and take off my shoes and socks and set them to dry. For a long time then, lying propped against the trunk of a tree, I read and rest and watch the evening come.

All day I have moved through the woods, making as little noise as possible. Slowly my mind and my nerves have slowed to a walk. The quiet of the woods had ceased to be something that I observe; now it is something that I am a part of. I have joined it with my own quiet. As the twilight draws on I no longer feel the strangeness and uneasiness of the evening before. The sounds of the creek move through my mind as they move through the valley, unimpeded and clear.

I wake long before dawn. The air is warm and I feel rested and wide awake. By the light of a small candle lantern I break camp and pack. And then I begin the steep climb back to the car.

The moon is bright and high. The woods stands in deep shadow, the light falling soft through the openings of the foliage. The trees appear immensely tall, and black, gravely looming over the path. It is windless and still; the moonlight pouring over the country seems more potent than the air. All around me there is still that constant low singing of the insects. For days now it has continued without letup or inflection, like ripples on water under a steady breeze. While I slept it went on through the night, a shimmer on my mind. My shoulder brushes a low tree overhanging the path and a bird that was asleep on one of the branches startles awake and flies off into the shadows, and I go on with the sense that I am passing near to the sleep of things.

In a way this is the best part of the trip. Stopping now and again to rest, I linger over it, sorry to be going. It seems to me that if I were to stay on, today would be better than yesterday, and I realize it was to renew the life of that possibility that I came here. What I am leaving is something to look forward to. ~ Wendell Berry

(Long but so so worth it).

Published on February 13, 2012 20:10

February 11, 2012

Announcements & Check In

Listening to Enchantment by Corinne Bailey Rae and it's time to make Valentine's cards. Here she is, in the dining room and scissors, glue gun, glitter and multi pink paper is scattered across the table. She's not sure sticking candy canes is right for V-Day but I tell her it's the ultimate recycle move. A few minutes of thought and she agrees--turning the candy canes into heart shapes. She is a keeper.

Listening to Enchantment by Corinne Bailey Rae and it's time to make Valentine's cards. Here she is, in the dining room and scissors, glue gun, glitter and multi pink paper is scattered across the table. She's not sure sticking candy canes is right for V-Day but I tell her it's the ultimate recycle move. A few minutes of thought and she agrees--turning the candy canes into heart shapes. She is a keeper. And what of Spencer these days? Second semester is over, finals behind us and he is pulling A's & B's--3.5 GPA. Math and science are his best subjects. That darn Latin is doing him in, but that's okay. "It's a dead language," I tell him. "But it's the language of science, Mom, and that's not dead."

Got it.

For those who don't know yet, I am teaching for The Attic Institute as of March 15th and their fine team is managing my local registrations. Three local classes are out of that space. David Beispiel is growing his teaching space, doubling the studios and it's going to be a great addition to my own programs. I hope to see you there.

For my virtual students, you have class options too. Check out the list of classes and click on the ones that might appeal to you. I'm hear to answer your questions so please, write to me at jennifer@jenniferlauck.com.

Virtual Classes :

Phase I Teaching: Download Your Memoir (Five Week Class)

Phase II Teaching: Critique Circle (Five Week Series)

Phase III Teaching: Sell Your Book (One day teaching)

Don't forget there are one on one consults and manuscript review services. I'm booked until April but don't hesitate to get your project on the list and I'm there for you!

Retreats

Palm Springs, CA - March 2012: Click Here

Manzanita, OR - August 2012: Click Here

Published on February 11, 2012 11:17

February 6, 2012

Writing Tip Monday

"Hey! Where is my writing tip?" you may be asking.

Today is my daughter's 10th birthday and yesterday there was no class...which meant I was at a party which meant I was not teaching...which meant I didn't write a writing tip or prompt.

So you can take a rest. But I have glorious news for you. Hope Edelman will be joining me for a Valentine's Day Live Free Teleseminiar conversation about memoir, publishing and living the writers life. No one does it more honestly than Hope.

So you can take a rest. But I have glorious news for you. Hope Edelman will be joining me for a Valentine's Day Live Free Teleseminiar conversation about memoir, publishing and living the writers life. No one does it more honestly than Hope.

Join us by signing up HERE. Click, sign up on the site and you'll get the announcement and details for how to be part of this terrific call.

Today is my daughter's 10th birthday and yesterday there was no class...which meant I was at a party which meant I was not teaching...which meant I didn't write a writing tip or prompt.

So you can take a rest. But I have glorious news for you. Hope Edelman will be joining me for a Valentine's Day Live Free Teleseminiar conversation about memoir, publishing and living the writers life. No one does it more honestly than Hope.

So you can take a rest. But I have glorious news for you. Hope Edelman will be joining me for a Valentine's Day Live Free Teleseminiar conversation about memoir, publishing and living the writers life. No one does it more honestly than Hope. Join us by signing up HERE. Click, sign up on the site and you'll get the announcement and details for how to be part of this terrific call.

Published on February 06, 2012 17:01

January 30, 2012

Writing Tip #20: Setting the Scene

Painters, like Monet, understand that location is "everything." Afterall, without a location, what would they paint? Location is what holds people, events, experience and without location, there is nothing but emptiness.

Painters, like Monet, understand that location is "everything." Afterall, without a location, what would they paint? Location is what holds people, events, experience and without location, there is nothing but emptiness. As a writer, using words on the canvas of the page and later, the mind of the reader, how do you establish location. Do you do this at all?

Writers new to the craft traditionally write 90% mental activity and this includes "telling" what happened--that is, event downloading. They usually give about 10% to location and setting. I offer up a different formula and invite you to flip the equation around. 80% showing of space, place, people, time, objects and senses and 20% to "what happened." And this includes the setting.

To ground your reader in time, space, place, a good writer knows that location is as vital to the story as the people and the events that take place. Without a location and the details that establish that location, the reader is unable to "land" and truly "experience" what the writer is sharing. Setting grounds the reader and grounds the experience. Setting also holds the forward moving action and can be referred back to again and again.

Prompt: Think about a significant moment from your life such as a turning point or a marker of transition. IE: the day your child was born, the car wreck that changed your life, the day you met your partner or realized you were in love (or told that person you were in love with them), a death in the family, a national disaster (9/11).

Before you write about the event, recall the setting which includes the day of the week, the time of day, the weather on that day, the season, the year (and events in the news that were happening at that time), the way the light moved through the room (if you were in a room), the direction of shadows, the foliage on the trees (if you are outside), the smell in the air, the sounds around you (was music playing, children laughing, dogs barking, bird song, toast hopping, water boiling), the furniture and what collected items lay around, the décor and so on. In one line write: The day so and so happened …and then spend the rest of the writing establishing the setting.

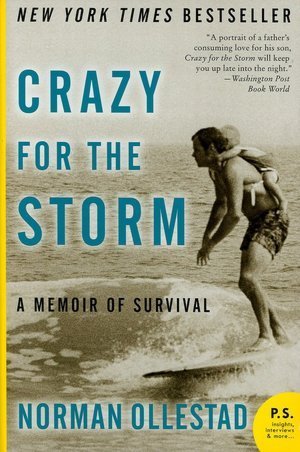

Example: Crazy for the Storm by Norman Ollestad, pg. 1-2

February 19, 1979. At seven that morning my dad, his girlfriend Sandra and I took off from Santa Monica Airport headed for the mountains of Big Bear...

February 19, 1979. At seven that morning my dad, his girlfriend Sandra and I took off from Santa Monica Airport headed for the mountains of Big Bear...The Cessna 172 lifted and banked over Venice Beach then climbed over a cluster of buildings in Westwood and headed east. I sat in front, headphones and all, next to pilot Rob Arnold. Rob fingered the knobs along the instrument panel that curved toward the cockpit's ceiling. Intermittently, he rolled a large vertical dial next to his knee, the trim wheel, and the plane rocked like a seesaw before leveling off. Out the windshield, way in the distance, a dome of gray clouds covered the San Bernardino Mountains, the tops alone poking through. It was flat desert all around the cluster of peaks, and the peaks stood out of the desert as high as 10,000 feet.

I was feeling especially daring because I had just won the slalom championship and I thought about the big chutes carved into those peaks—concave slides, dropping from the top of the peaks down the faces of the mountains like deep wrinkles. I wondered if they were skiable.

Behind Rob sat my dad. He read the sports section and whistled a Willie Nelson tune that I'd heard him play on his guitar many times. I craned my head around to see behind my seat. Sandra was brushing out her silky dark brown hair. She's dressed kinda fancy, I thought.

How long, Dad? I said.

He peered over the top of the newspaper.

About thirty minutes, Boy Wonder, he said.

Homework: Notice setting in the book you are currently reading, or go find a few memoirs and make note of the setting in each one.

Remember, a well-rendered memoir establishes setting within the first few paragraphs and allows the personality of place, revealed through attention to detail, to lift and influence the story.

Published on January 30, 2012 09:17

January 29, 2012

Small Talk & Annoucements

Fred Meyer on a Thursday. Jo, me, 2x2 dressing room and overhead florescent lights that are so bright they feel as if they beat me between the eyes. A man with a gritty southern voice, a loud talker who works the various check stands and who I avoid because of that voice, announces fresh and hot sourdough loaves have just come out of the oven in the bakery

Fred Meyer on a Thursday. Jo, me, 2x2 dressing room and overhead florescent lights that are so bright they feel as if they beat me between the eyes. A man with a gritty southern voice, a loud talker who works the various check stands and who I avoid because of that voice, announces fresh and hot sourdough loaves have just come out of the oven in the bakery"Which one do you like?" Jo asks.

She's down to two dresses. One is white, drop waist (think Flapper from the 20's) and the fabric seems to have been drenched in glitter. I have sparkles on my hands, my arms, my sleeves, my shoulders, my legs, my books. There is a circle of glitter around Jo's feet.

"I'd go with the pink one," I say.

"I always do pink. I've never done white."

Another announcement scratches out over the intercom system and I uncross and re-cross my legs. I have been sitting in this closet sized dressing room for too long. My leg is cramped.

"Mommy," she says, "I can't pick. I love them BOTH. I always get myself into this kind of a pickle."

This makes me laugh. Out loud. And that's unusual. Jo isn't the one who gets me to belly laugh. The comedy job has been filled by Spencer for all these years (he's 14) but Jo--a few days from ten--is funny. Like her body grows, this sense of humor blooms too. She's busted me up several days in a row now. These one line zingers that come from no where.

"Don't yell at the teacher, he has more power than you do," I overheard her tell a friend the other day.

"A-t-t-i-t-u-d-e," she whispered when her brother was being a pill.

"That Eli," she said, after a boy asked her what time it was and then walked away, "he's a nice fellow."

"Pickle," I say. "Yes, I suppose you're in a pickle."

The search and purchase of a birthday dress is my little ritual, I don't recall when I got it started, but Jo has latched on the way kids do. They love routine. And now, every year, we go shopping for a dress.

"Which one would you get?"

"Pink," I say again. "Your skin is perfect with that pink."

And then it happens. Jo, her own person, makes a decision--not based on what I think but based on what she wants.

"I've never had a white dress," she says. "I'm taking the white."

You would think, maybe, that I would care that she picked a dress that I didn't necessarily like. You might think, "well, that girl is going to be a handful when she's a teen." But I don't think about things that way.

While it's almost her birthday, I am the one getting the gift of how she is becoming her own person, her own wonderful self with her own tastes and thoughts and conclusions. I have given that to her, hard earned in a way because I still am not as confident as Ms. Jo is. Jokes are easy but confidence--true confidence in yourself and your choices--that is hard.

As yet another announcement for hot fresh sourdough bread grates over our heads--sound pollution--we leave the pink dress behind and take the white dress to the check out stand. Hand in hand we walk, Jo happy with her choice and me with glitter all over my hands.

~

8 Writers, 3 Days ~ Write, Relax & Restore.

The 2012 Summer Retreat is for writers in search of depth instruction and personal mentoring. Come to Manzanita, a tiny coastal town snugged on the Oregon coastline, and savor four full days to write, receive teachings and read your work aloud. This unique, once a year opportunity, combines the best of camaraderie, solitude, teachings and celebration.

The 2012 Summer Retreat is for writers in search of depth instruction and personal mentoring. Come to Manzanita, a tiny coastal town snugged on the Oregon coastline, and savor four full days to write, receive teachings and read your work aloud. This unique, once a year opportunity, combines the best of camaraderie, solitude, teachings and celebration. SCHEDULE:

Fri:

10-1 p.m. Breakfast & Teachings

1-6:30 p.m. Personal writing time

6:30 - 9:30 Desert, teachings, reading & conversation

Sat:

10-1 p.m. Breakfast & Teachings

1-6:30 p.m. Personal writing time

6:30 - 9:30 Desert, teachings, reading & conversation

Sun:

10-1 p.m. Breakfast & Teachings

1-6:30 p.m. Personal writing time

6:30 - 9:30 Desert, teachings, reading & conversation

COST:

$375.00 Early Sign Up (Prior to May 15, 2012)

$450.00 Late Sign Up (May 16, 2012)

Jennifer covers your teachings, breakfast and evening desserts.

You cover your travel to and from Manzanita and your accommodations.

Sign Me Up!

Early Sign Up Deposit $150.00 USD

Early Sign Up Tuition Bal $225.00 USD

Early Sign Up Full Tuition $375.00 USD

Late Sign Up Deposit $150.00 USD

Late Tuition Bal $300.00 USD

Late Full Tuition $450.00 USD

While we can help make accommodation recommendations for writers and can arrange meetings between students for ride share, we will not be responsible for your travel or accommodations. You are encouraged to find a place to stay that allows privacy, relaxation, restoration and space to write.

RECOMMENDED LODGING:

(Luxury)

Inn at Manzanita

Coast Cabins

Ocean Inn

(Affordable Shabby Chic)

Spindrift

Sunset Surf

(House Share Opportunities)

Sunset Vacation Rentals

Published on January 29, 2012 23:24

January 23, 2012

Writing Tip #19: Your Place in the Family

Writing about our family is hard. Here are some questions I hear all the time:

Writing about our family is hard. Here are some questions I hear all the time: "What if they read what I write and they disagree?"

"What if I'm wrong?"

"What if I hurt someone I love?"

"What if I break our generation-long 'code of silence?'"

Here are a few ways to practice breaking into these fears and breaking out of the habituated ways you look at the people in your life. Your family members are not props on your stage, they are mysterious and complex. You don't have to figure anyone out, you just need to present them accurately and with a level of complexity. Good writing is being a great witness and also being able to describe people in such a way that you touch on the mystery of human beings and human interactions.

Prompt: Create a picture of your family based on some simple gesture: the way they sign, laugh, cry or kiss. Begin with a vivid, original description of these gestures, then describe your father, your mother, yourself, or any other family member. Try to see how examining these small gestures reveals larger details about the family. (Thank you to Brenda Miller and Suzanne Paola from Tell it Slant for this prompt)

See an example of how to do this prompt by reading this excerpt from The Fine Art of Sighing by Bernard Cooper

[image error] You feel a gradual welling up of pleasure, or boredom, or melancholy. Whatever the emotion, it's more abundant than you ever dreamed. You can no more contain it than your hands can cup a lake. And so you surrender and suck the air. Your esophagus opens, diaphragm expands. Poised at the crest of an exhalation, your body is about to be unburdened, second by second, cell by cell. A kettle hisses. A balloon deflates. Your shoulders fall like two ripe pears, muscles slack at last.

My mother stared out the kitchen window, ashes from her cigarette dribbling into the sink. She'd turned her back on the rest of the house, guarding her own solitude. I'd tiptoe across the lino-leum and make my lunch without making a sound. Sometimes I saw her back expand, then heard her let loose one plummeting note, a sigh so long and weary it might have been her last. Beyond our backyard, above telephone poles and apartment buildings, rose the brown horizon of the city; across it glided an occasional bird, or the blimp that advertised Goodyear tires. She might have been drifting into the distance, or lamenting her separation from it. She might have been wishing she were somewhere else, or wishing she could be happy where she was, a middle-aged housewife dreaming at her sink.

My father's sighs were more melodic. What began as a somber sigh could abruptly change pitch, turn gusty and loose, and suggest by its very transformation that what begins in sorrow might end in relief. He could prolong the rounded vowel of OY, or let it ricochet like a echo, as if he were shouting in a tunnel or a cave. Where my mother sighed from ineffable sadness, my father sighed at simple things: the coldness of a drink, the softness of a pillow, or an itch that my mother, following the frantic map of his words, finally found on his back and scratched.

The Lesson: Cooper gives us a terrific sense of how to examine something as unique as the human sigh. I have seen other students take this lesson and apply it to eyebrows, hugs, the way men in the family cry and waistlines. You are only limited by your own imagination.

As you write, keep asking yourself where you fit in your family and if you can observe, with minute detail, your place and their place. Can you separate yourself out and make room for the largess of the others? Can you be the more complete witness?

Published on January 23, 2012 14:44

January 17, 2012

Book Talk: Found: A Memoir by Jennifer Lauck

Taking a swerving diversion off the Book Talk path, I am using this time to speak a bit about a "web tour" that has been orchestrated by Lori, an adoptive mother and a writer. Lori, via her website, coordinates book tours where interested bloggers sign up, read the book and then--on a designated day--review the book.

Taking a swerving diversion off the Book Talk path, I am using this time to speak a bit about a "web tour" that has been orchestrated by Lori, an adoptive mother and a writer. Lori, via her website, coordinates book tours where interested bloggers sign up, read the book and then--on a designated day--review the book. Found was chosen. The tour posts began Friday, continued Sunday and were done by Tuesday.

To read for yourselves, click here. Beware. Some of these posts are not fun to read. Others are simply stunning. To save yourself a whole lotta of cruising around, I list my favorite blogs here:

By Adoptees

Neither Here Nor There

Insert Bad Movie Title Here

Rhonda Rae on Examiner Book Tours

Birthmothers

Letters to Ms. Feverfew

A Birth Mother's Path

Those Who Adopt & Experts in Adoption Counseling

Zeina

Parenting Your Adopted Child

Published on January 17, 2012 14:24

Writing Tip #18: 16 Editing Must Know's

Blatantly stolen from: Tips for Writing Well by Austin Govella

My advice: Print this and keep it near your writing space.

Be vicious when you edit. Vicious. Follow these recommendations with zealous fervor. They help your writing say what it should in a way we'll understand.

1. I think, I'd say, in my opinion, what I've found, in my experience… Yeah. We know. You wrote this. These are your thoughts. If they're not, provide a reference. If they're yours, the byline is enough to remind us.

2. Delete all adverbs and adjectives unless they're absolutely, totally, inherently necessary. Each unnecessary word weakens your impact and clarity.

3. Remove prepositional phrases. Prepositional phrases are less important than your main point. If it's not important enough to deserve its own sentence, it's not important enough to read.

4. Active not passive. Kill "to be" verbs. All of them. Always.

5. Kill -ing words. Restructure your sentence so the -ing is an active verb.

6. Lead with the bottom line up front: BLUF. Then include an example, re-state the bottom line, include an illustration, and when you end restate the bottom line. For every point you make, follow this pattern. That's bottom line, example, bottom line, another example, and then the bottom line (again).

7. Telegraph and signpost what you will say and why we care. We're not reading mystery novels. We want to know who died, how, who killed them, and why we care up front. That way, we know why we want to read before we begin.

8. Use clear, informative headers. Cute or artsy might be pleasant on the first read, but when we reference it later, the cute header makes it a pain to find things. What you're writing is worth going back to, right?

9. Introduce new terminology in the intro. If you've created a new term or applied a new phrase to describe something, define it at the beginning, and use the new terminology throughout your writing. Readers need the entirety of your piece to learn and assimilate the new phrasing.

10. Typically, sometimes, often times, usually… Yeah. We know. You don't have to tell us.

11. Say "you" and "your". Don't use nouns when talking about your audience (like "User Experience Practitioners"). And don't use "one". Speak to us.

12. Ditch clunky words. Instead of "via", write "using". Instead of "upon", say "on".

13. Remove cliches and common phrases. Every time you take a common phrase shortcut, you're telling us it's not worth our time.

14. Use contractions. Write with proper grammar, and people will read. Write like you talk, and people will listen.

15. No pronouns. Repeat the noun over and over again. If you get tired of that, use synonyms.

16. Delete your best lines. We don't care about poetry, wit, or slyness. We care about what you want to say.

After you edit…

The finished piece should be so tight, terse, concise, and clear that it's boring.

Boring.

Then sand off the rough edges.

Write like you talk. Where the concise feels awkward, add conversational. Where tight lacks nuance, tease details. Where terse is cold, be warm.

The first 16 recommendations remove fluff and force you to think and communicate. Once you've finished editing intellectual work, go back and make sure you write like you talk. Writing begins a conversation. If we feel like you're talking to us, we'll listen.

My advice: Print this and keep it near your writing space.

Be vicious when you edit. Vicious. Follow these recommendations with zealous fervor. They help your writing say what it should in a way we'll understand.

1. I think, I'd say, in my opinion, what I've found, in my experience… Yeah. We know. You wrote this. These are your thoughts. If they're not, provide a reference. If they're yours, the byline is enough to remind us.

2. Delete all adverbs and adjectives unless they're absolutely, totally, inherently necessary. Each unnecessary word weakens your impact and clarity.

3. Remove prepositional phrases. Prepositional phrases are less important than your main point. If it's not important enough to deserve its own sentence, it's not important enough to read.

4. Active not passive. Kill "to be" verbs. All of them. Always.

5. Kill -ing words. Restructure your sentence so the -ing is an active verb.

6. Lead with the bottom line up front: BLUF. Then include an example, re-state the bottom line, include an illustration, and when you end restate the bottom line. For every point you make, follow this pattern. That's bottom line, example, bottom line, another example, and then the bottom line (again).

7. Telegraph and signpost what you will say and why we care. We're not reading mystery novels. We want to know who died, how, who killed them, and why we care up front. That way, we know why we want to read before we begin.

8. Use clear, informative headers. Cute or artsy might be pleasant on the first read, but when we reference it later, the cute header makes it a pain to find things. What you're writing is worth going back to, right?

9. Introduce new terminology in the intro. If you've created a new term or applied a new phrase to describe something, define it at the beginning, and use the new terminology throughout your writing. Readers need the entirety of your piece to learn and assimilate the new phrasing.

10. Typically, sometimes, often times, usually… Yeah. We know. You don't have to tell us.

11. Say "you" and "your". Don't use nouns when talking about your audience (like "User Experience Practitioners"). And don't use "one". Speak to us.

12. Ditch clunky words. Instead of "via", write "using". Instead of "upon", say "on".

13. Remove cliches and common phrases. Every time you take a common phrase shortcut, you're telling us it's not worth our time.

14. Use contractions. Write with proper grammar, and people will read. Write like you talk, and people will listen.

15. No pronouns. Repeat the noun over and over again. If you get tired of that, use synonyms.

16. Delete your best lines. We don't care about poetry, wit, or slyness. We care about what you want to say.

After you edit…

The finished piece should be so tight, terse, concise, and clear that it's boring.

Boring.

Then sand off the rough edges.

Write like you talk. Where the concise feels awkward, add conversational. Where tight lacks nuance, tease details. Where terse is cold, be warm.

The first 16 recommendations remove fluff and force you to think and communicate. Once you've finished editing intellectual work, go back and make sure you write like you talk. Writing begins a conversation. If we feel like you're talking to us, we'll listen.

Published on January 17, 2012 06:32

January 14, 2012

Small Talk & Annoucements

The holiday season is officially over and it's "back to work," with a full roster of classes. The Master Class has met twice and I'm teaching for The Attic Institute Monday, Jan. 17th. That class, on Downloading, is full but keep an eye on The Attic schedule for additional classes.

My studio is hosting two more classes this winter: 1) a Critique Circle for writers to workshop pages each week and 2) a class on how to Market, Sell & Publish your book. These are going to be terrific classes so don't miss out.

Here are the details:

Sell It: Market, Sell & Publish Your Book the Creative Way

This class will be helpful to you at any stage of your writing process. You could just be at the beginning phase, at the 4th draft phase or you could be ready right to sell it right now. This five week class will teach you the creative way to sell your book. You will hear the unique story of how I was able to publish my first book as a totally unknown writer. You will be given prompts to create your own way to achieve your goal. And you will be taught the tried and true way of getting published. Learn about marketing comparison survey reports, platform building, networking and how to call on stores of courage you will need to see your book in print! You leave this class with a 85 page workbook and an audio CD of instructions.

This class will be helpful to you at any stage of your writing process. You could just be at the beginning phase, at the 4th draft phase or you could be ready right to sell it right now. This five week class will teach you the creative way to sell your book. You will hear the unique story of how I was able to publish my first book as a totally unknown writer. You will be given prompts to create your own way to achieve your goal. And you will be taught the tried and true way of getting published. Learn about marketing comparison survey reports, platform building, networking and how to call on stores of courage you will need to see your book in print! You leave this class with a 85 page workbook and an audio CD of instructions.

DAY/TIME/DATE: Tuesdays, 7-9 p.m., February 7, 14, 21, 28, Mar. 6

WHERE: 2325 E. Burnside, Suite 102

COST: $325.00 (see refund policy at bottom of school page)

Students leave with a Workbook & a CD of the class

Sign Up Today

Deposit (non-refunded) $100.00 USD

Remaining Tuition $225.00 USD

Full Tuition $325.00 USD

Six Writers-Six Weeks–Critique Circle:

This class is for the more advanced writer who is progress on a manuscript or essay length work (articles are acceptable too). You needs to hear yourself read and to get skilled critique. You will be part of a very small group, just six writers and are invited to bring 8-10 pages of your current work per week. You'll read and discuss your work in the circle.

REQUIREMENT: You must have taken a class with Jennifer or have an interview to discuss your project.

DATES: Tuesday 7-9 p.m., Feb. 6, 13, 20, 27, Mar. 5 & 12

COST: $40.00 per class/$240.00

NOTE: Yes, this class has the virtual option via Go To Meeting

Payment Options

Deposit $80.00 USD

Balance $160.00 USD

Full Tuition $240.00 USD

My studio is hosting two more classes this winter: 1) a Critique Circle for writers to workshop pages each week and 2) a class on how to Market, Sell & Publish your book. These are going to be terrific classes so don't miss out.

Here are the details:

Sell It: Market, Sell & Publish Your Book the Creative Way

This class will be helpful to you at any stage of your writing process. You could just be at the beginning phase, at the 4th draft phase or you could be ready right to sell it right now. This five week class will teach you the creative way to sell your book. You will hear the unique story of how I was able to publish my first book as a totally unknown writer. You will be given prompts to create your own way to achieve your goal. And you will be taught the tried and true way of getting published. Learn about marketing comparison survey reports, platform building, networking and how to call on stores of courage you will need to see your book in print! You leave this class with a 85 page workbook and an audio CD of instructions.

This class will be helpful to you at any stage of your writing process. You could just be at the beginning phase, at the 4th draft phase or you could be ready right to sell it right now. This five week class will teach you the creative way to sell your book. You will hear the unique story of how I was able to publish my first book as a totally unknown writer. You will be given prompts to create your own way to achieve your goal. And you will be taught the tried and true way of getting published. Learn about marketing comparison survey reports, platform building, networking and how to call on stores of courage you will need to see your book in print! You leave this class with a 85 page workbook and an audio CD of instructions. DAY/TIME/DATE: Tuesdays, 7-9 p.m., February 7, 14, 21, 28, Mar. 6

WHERE: 2325 E. Burnside, Suite 102

COST: $325.00 (see refund policy at bottom of school page)

Students leave with a Workbook & a CD of the class

Sign Up Today

Deposit (non-refunded) $100.00 USD

Remaining Tuition $225.00 USD

Full Tuition $325.00 USD

Six Writers-Six Weeks–Critique Circle:

This class is for the more advanced writer who is progress on a manuscript or essay length work (articles are acceptable too). You needs to hear yourself read and to get skilled critique. You will be part of a very small group, just six writers and are invited to bring 8-10 pages of your current work per week. You'll read and discuss your work in the circle.

REQUIREMENT: You must have taken a class with Jennifer or have an interview to discuss your project.

DATES: Tuesday 7-9 p.m., Feb. 6, 13, 20, 27, Mar. 5 & 12

COST: $40.00 per class/$240.00

NOTE: Yes, this class has the virtual option via Go To Meeting

Payment Options

Deposit $80.00 USD

Balance $160.00 USD

Full Tuition $240.00 USD

Published on January 14, 2012 15:41