Suzanne Fagence Cooper's Blog, page 3

August 29, 2014

Effie Gray and Scottish Independence

Over the past weeks I’ve been trying to work out how Effie and her family would vote in the Scottish referendum. Of course, the very idea of voting on a national issue would be alien to her – Effie died two decades before women won the right to vote for their Westminster MP. But I’m sure she and her parents, and brothers, and daughters, would have debated the question over the dinner table. Their letters show that the Grays were a vocal clan, and willing to squabble and then resolve their disagreements. They didn’t bear grudges. They kept talking through their differences even when they were cross with each other.

George Gray, Effie’s father, c. 1865

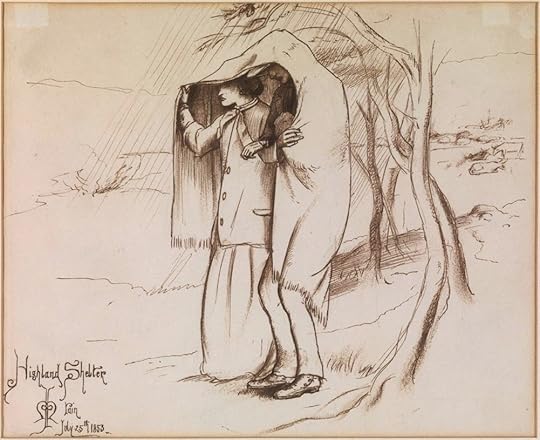

So, what would Effie think about Scotland as an independent country? She was staunchly loyal to the place of her birth. And she returned home to Bowerswell, her family house just outside Perth, when she knew she was dying. She always relaxed in the Scottish hills. The Trossachs held special associations for her. It was at Brig o’Turk that she came to realise that her first marriage, to John Ruskin, was over. Ruskin ‘had no intention of making her his Wife’. Here she began to wrestle with the possibilities for her future. The young pre-Raphaelite, John Everett Millais, fell in love with Effie on this Scottish holiday. He drew her obsessively in the cramped cottage he shared with Effie and Ruskin throughout the wet summer months.

John Everett Millais, Highland Shelter, 25thJuly 1853

After Effie left her husband, she went straight home to Perthshire. Back in Scotland, she swam, and strode out along the coast, regaining her strength and pondering. Eventually, in July 1855, she quietly married again. She and her second husband, Millais, spent their honeymoon on Arran, where Effie admitted, ‘they were very comfortable’, waking each morning to clear skies and rowing out into the bay in the cool of the evening. In August 1855 Effie and Millais settled in Bowerswell, safe from the wagging tongues of the London art world. Millais grew to love Scotland. His most sensitive paintings, including ‘Autumn Leaves’ and ‘The Vale of Rest’ were set against the Scottish sunset, with Bowerswell as a backdrop and local girls as models.

John Everett Millais, Autumn Leaves, 1855-6

Effie was sure of her Scottishness even when she moved back to South Kensington in the autumn of 1861. She kept in touch constantly with her parents, and went home as often as she could. Her father had shares in the Dundee-London steamer service, so Effie and her children made the journey several times a year. And every summer Millais joined them, decamping to the Highlands to fish and shoot. Effie’s young family wrote longingly about holidays with their grandparents, when the perpetual hum of London traffic was replaced by the hum of bees. The children associated these visits with the taste of fresh cream and honey on porridge, with music and parties, with bicycle outings, with family.

So Scotland was a place of personal refuge. But Effie was also well aware of its political and judicial differences from England. She was married (twice) in her father’s house. As a Scottish wife, she understood that her legal status was a little better than a woman married in England. She was entitled, for instance, to defend herself against accusations of infidelity. And she could demand financial support from her husband. Unlike English brides, she retained some of her own property after marriage – at least her clothes and ‘paraphenalia’ remained hers and not her husband’s.

Effie came from a family of lawyers and bankers. She recognised and applauded the autonomy of the Scottish legal system. She also benefited from the self-reliance that characterised her family. Her father, George, was an entrepreneur. Sometimes he made the wrong call. His investments in French railway stock at a time of political turmoil on the continent brought the Grays to the brink of financial disaster in the Spring of 1848. But he recovered, and by the 1860s was a pillar of the banking establishment in Perth.

And here, in a nutshell, lie the answers to Effie’s reaction to Scottish independence: self-reliance, and the Establishment. Effie and her family were conservatives. They wanted to be accepted by their neighbours and their colleagues. George Gray worried about the gossip in the golf-club when his girls got themselves into romantic scrapes. His reputation mattered. He made himself indispensable as manager of the Perth branch of the Royal Bank of Scotland for many years. He founded the Standard Life Assurance Company in the town, and threw parties for the directors of the Gas Light Company, with ‘as much champagne as they could drink’. After a few shaky speculations in the 1840s, George Gray was a substantial figure by the time Effie married her second husband. This security, this sense of having arrived financially and socially, was underpinned by a strong political conservatism.

Effie shared her father’s aspirational attitude, and his conservative political outlook. She was a social-climber, unashamedly marrying money. She only had one possible career path, and that was a good marriage. John Ruskin offered her security, family connections and the chance to make a splash in Society. She could provide the social skills he lacked, and smooth his path through London soirées. Effie expected to be presented at Court as Mrs Ruskin. When she made her debut on 20thJune 1850, she was admired for her dress and her poise as she curtseyed and kissed Victoria’s hand. As Mrs Millais, she was barred from the Queen’s presence – because she had 2 husbands still alive. This did not stop her becoming good friends with Constance, Duchess of Westminster, and later, Princess Louise, the sculptor-daughter of Queen Victoria. These friendships mattered. They signified that the scandalous failure of her first marriage had not blighted her life. But Effie could not afford to be politically radical. Her reputation was too fragile. Yes, she and Millais enjoyed the company of Louise Jopling, the dazzling artist, Suffragist and teacher. But Effie did not agree with Louise’s forthright campaigning for ‘Votes for Women’.

John Everett Millais, Louise Jopling, 1879

In fact, Effie’s only overtly political act was to join the Primrose League. This organisation had been established in 1883 in memory of the Prime Minister, Benjamin Disraeli. When Effie enrolled as a Dame of the League in July 1885, she vowed to ‘uphold and support God, Queen and Country, and the Conservative cause’. Effie was a staunch Tory. By the summer of 1885, she was also a Lady herself, since Millais had just been made Baronet.

In these circumstances, it seems unlikely that Effie would countenance the break-up of the Union. Disraeli and his Tory party were staunchly Unionist when it came to the question of Ireland. They would never have dreamt that Scotland might seek independence. Effie was a Scot who came to London to seek her fortune. And she was successful. Scotland was home, but London was where she shone.

And so finally we come to the element of self-reliance. Effie Gray was prepared to stand up for herself when her marriage became intolerable. She learnt to thrive and think independently as a teenager – she kept house when her mother was confined by childbirth. Her brothers and cousins, and sons and nephews all demonstrated that they could flourish in adversity. They were flung across the Empire, to farm and fend for themselves. Their letters home, from Melbourne or Dunedin told how they ‘were getting the wool off the sheep’s backs to send to London to convert into coin.’ Effie’s daughter Mary made the crossing from England, to Cape Town, to New Zealand and then on to Australia in 1885-6, visiting family as she went. Mary linked the scattered outposts of the Gray clan together. Her correspondence and her photographs show how Effie’s family embodied the idea of Empire. They took the opportunities that were given by a Greater Britain, and they prospered.

Walter Crane, Imperial Federation Map, 1886

It is this idea of a Greater Britain that made sense to Effie and her daughters. They saw the virtues of thinking big. They loved their Scottishness, but they were not limited by it. I think Effie would vote for the Union.

Published on August 29, 2014 08:04

July 15, 2014

'Art Happens': James Whistler and Ten O'Clock lecture

February 1885: the Ten o’clock Lecture

A man in immaculate evening dress stepped onto the stage in Prince’s Hall, Piccadilly. He placed a glossy opera hat on the table, set down his walking-cane and adjusted his eyeglass. James Whistler appeared in the footlights like a figure from one of his own canvases: an Arrangement in Black and Silver. ‘It is with great hesitation and much misgiving’ he began, ‘that I appear before you, in the character of The Preacher’. Whistler had practised his lines during the past winter months, trying out turns of phrase as he strode up and down the riverbank at Chelsea. He had perfected his principles over countless dinner-tables. As one friend put it, ‘the only new thing was Whistler’s determination to say in public what he had said in private.’ But now he faltered a little as he cast his eye over the up-turned faces before him. He recognised several devoted followers, some sceptics, many critics.

What had they come to hear? Most expected a fashionable evening’s entertainment, an American eccentric showing-off. His droll delivery meant that they underestimated the force of his attack on the art-establishment. For Whistler’s monogram was very apt – a butterfly with a sting in his tail.

Whistler’s radical artistic manifesto struck at the heart of Victorian assumptions about beauty, Nature and the role of the artist in society. Firstly, he declared that art-critics should leave the masses alone. Most folk would never be enthusiastic about spending their spare time in galleries or creating the House Beautiful. ‘The people have been harassed with Art…their homes have been invaded’ and, Whistler suggested, this has left the public bewildered and resentful. Instead, Art should be left to those who could best appreciate it. The true artist, Whistler said, was an outside, a ‘dreamer apart.’ Like himself.

And Art was not meant to be improving. The public were encouraged to delight in pictures that were morally uplifting. They admired naturalism, anecdote or sentiment. Whistler summed up this approach: ‘Before a work of Art, it is asked: ‘What good shall it do?’. In his view, this was utterly wrong-headed. For Whistler, Art was ‘occupied with her own perfection only – having no desire to teach’. Art was about beauty, delight, joy.

He went on to tackle another fundamental tenet of Victorian thinking. Whistler denied that art was more likely to flourish in a particular time or place. The most beautiful things could be made in ancient Greece, or at the Court of Philip II of Spain, in Rembrandt’s Amsterdam or Hokusai’s Japan. Whistler scoffed at the ‘fabled link between the grandeur of Art and the glories and virtues of the State’. Beauty was wedded to individuals, not to Nations. In his words, ‘peoples may be wiped from the face of the earth, but Art is.’

His delivery gained strength as he took on the British obsession with painting the natural world. An artist, Whistler believed, ‘does not confine himself to purposeless copying, without thought, each blade of grass.’ (This was a dig at the hypnotic realism of the Pre-Raphaelites.) Whistler denounced Nature as vulgar. He acknowledged that many in the audience would be shocked by this blasphemy. ‘Nature is very rarely right’, he argued, ‘to such an extent even, that might almost be said that Nature is usually wrong.’ Only the artist could select elements from the natural world, group them, and create something harmonious.

Whistler used a musical analogy to explain his idea. He suggested that ‘Nature contains the elements, in colour and form, of all pictures, as the keyboard contains the notes of all music’. So drawing directly from natural examples was like saying to the musician ‘that he may sit on the piano.’ Whistler knew how to make an audience laugh, but he also kept them on their toes. They could not anticipate whom he would lunge at next.

In his bantering way, Whistler was taking on the Victorian heavy-weights, John Ruskin and William Morris, as well as the more esoteric art-criticism of Oscar Wilde and Walter Pater. He was paying off old debts, and sizing up new rivals. In 1878 he had been publicly humiliated by Ruskin. In the ensuing libel case, Whistler was forced to justify the value of his art to the Attorney-General. His paintings were described in court as ‘strange fantastical conceits,…daubs,…not serious works of art’. He was bankrupted. Whistler destroyed many of his paintings, sold his house and left London. He passed a chill winter exiled in Venice. He took with him two dozen copper etching plates, reams of brown paper and boxes of pastels. He etched, though his fingers were so numb with cold that he could hardly hold the needle. He drew his bare lodgings in a dilapidated palazzo, with his companion Maud Franklin silhouetted against the open window. He called this work The Palace in Rags. He refused to picture the buildings that Ruskin had glorified in his book, ‘The Stones of Venice’. Instead Whistler’s Venice was ephemeral, glittering and intimate.

Now, five years on, Whistler was ready to answer his critics. He had regained a foothold in the London art-world, with his one-man exhibitions at the Fine Art Society. He was re-establishing his name as a portraitist. Whistler combined the verve of Velasquez with a sharp critique of modern manners. His painting of Lady Archibald Campbell caused a sensation at the Grosvenor Gallery in the summer of 1884: her shiny yellow boot and black stocking could be glimpsed beneath the hem of her dress as she whisked her skirts away from the picture frame. Whistler’s female figures were supple and ambiguous. He designed many of the gowns worn by the women who sat for him and he chose to dress them gorgeously in translucent layers of tulle and soft pleated silks. He disliked the current vogue for ‘Aesthetic Dress’. Whistler deplored the uncorseted, ‘unbecoming’ robes in sad colours that made young women look lanky and dishevelled. One reason for his dislike was that the campaign for ‘Dress Reform’ was so publicly championed by Oscar Wilde. Both men liked nothing better than a verbal sparring match.

Wilde had lectured on ‘Beauty, Taste and Ugliness in Dress’ to audiences across Britain in 1884-5, from Leeds to Dublin, from Bury St Edmunds to Newcastle. So it was partly in response to Wilde’s successful speaking engagements that Whistler decided to book the Prince’s Hall in February 1885. Whistler had heard Wilde there, delivering his ‘Impressions of America’. Now an American-born artist would take to the stage to lecture about the British, their failings and follies. Whistler’s line about the public’s reluctance in the face of Art – ‘they have been told how they shall love Art, and live with it…their very dress has been taken to task’ – was a jibe directed at Wilde. Their wit was competitive. Their friendship, formed in 1881, was now wearing thin. But the rivalry was still, to some extent, stage-managed.

Whistler asked Helen Carte, wife of the impresario Richard D’Oyly Carte, to arrange the booking of the lecture hall. As she was in the throes of producing The Mikado, Whistler took to wandering over to her tiny office at the Savoy Theatre in the evenings. There, in the winter lamplight, they discussed Whistler’s plan. He wanted his audience to enjoy an un-hurried dinner before coming on to the lecture. Ten o’clock in the evening seemed like a civilised hour to start. Whistler recognised that this timing alone would raise eyebrows among the industrious middle-classes. He evidently did not expect his audience to have to rise early the following day. But as he consistently explained in the lecture, Art was not a matter for the masses, but for the Few.

Whistler was of course aware of the paradox. He was preaching the gospel of the artist set apart from society before a large paying audience. And he was prepared to take his ideas on the road. He gave the same lecture on three more occasions in 1885 – Cambridge, Oxford, and again in London – and then had the text privately printed. It was an edition of 25 copies, a trifle that could be passed off to friends. His Ten o’clock lecture was a triumph of self-publicity, it made him a celebrity, a gift for the cartoonists with his monocle and his tuft of white hair carefully arranged among the black curls.

But, for all the swagger, Whistler was in earnest. He derided Ruskin, as he would later deride the poet Swinburne and indeed Wilde, because they could do nothing but talk. They could not make an image appear upon the canvas as Velasquez did when he ‘dipped his brush in light and air, and made his people live within their frames, and stand upon their legs.’ Critics were parasites. The true artist did not want his pictures to be read as novels, decoded for their morals. Painting was about form, colour and composition, not about subject. Whistler gave his works musical titles – Arrangements, Harmonies, Symphonies – to deflect attention from the thing in the picture, and to focus on the way it was painted. His canvases could be consumed as a piece of music is consumed, the audience concentrating on the formal aspects of the art, its shape, its rhythms, its mood. Whistler was not interested in story-telling. When he was questioned about one of his landscapes, a Harmony in Grey and Gold, Whistler wrote, ‘I care nothing for the past, present or future of the black figure, placed there because the black was wanted at that spot.’ Narrative was unnecessary. Morality, history, faith, patriotism, pity were irrelevant.

It may have seemed on that February evening that the audience were merely watching a butterfly flapping its wings, and causing a small stir in Piccadilly. But the repercussions were breath-taking. Whistler’s lecture brushed away the old certainties about what to paint, how to paint it and how to write about painting. Whistler imagines the artist as ‘differing from the rest, whose pursuits attracted him not.’ An artist was not bound by the laws of realism. An artist could decide when a work was finished: it may look like a sketch to the uninitiated, but according to Whistler, ‘the work of the master reeks not of the sweat of the brow – suggests no effort – and is finished from the beginning’. An artist worked for the pleasure of the few, not for the many.

This was a manifesto showing how art could be made modern. Art is uninhibited by history, uninterested in explaining itself to those who cannot see. It is concerned with the vision of the artist, not the expectations of the patron or the critic. Art is swift. It is eclectic. As Whistler put it, ‘Art happens’.

Published on July 15, 2014 06:39

June 30, 2014

Pop Goes the Artist

New Lecture for summer 2014

POP GOES THE ARTIST: FROM WARHOL TO DYLAN

Something a little different - 20th C American, rather than 19th C British Art. Recently I've had a chance recently to look closely at some fascinating works of Pop Art. And it all ties in rather neatly with my work on music and the visual arts. So here's a taste of Pop culture:

Bob Dylan's Pictures:

‘The press never let up’, Dylan wrote in his autobiographical Chronicles: Volume One (2004). ‘Once in a while I would have to rise up and offer myself for an interview so they wouldn’t beat down the door.’ Dylan answers his critics by creating his own headlines. In his world, Robert Zimmerman can transform himself: as he told his audience in 1964, ‘I have my Bob Dylan mask on.’

Throughout his career, Dylan has been accused of borrowing, cutting and pasting. His 2001 album Love and Theft acknowledged as much in the title. Joni Mitchell infamously called him a plagiarist. ‘Everything about Bob is a deception’, she said in 2010. But many others take different view. He is beloved by cultural historians who write academic essays about intertextuality and his use of the ‘embedded’ quotation.The tales told in traditional songs also resurface in his works of visual art too, his prints and drawings. Greed, guilt and jealousy. Exile and tragedy. Outlaws and temptresses. The folk stories are spelt out in banner headlines. These blatant texts also take us back to Dylan’s starting-point, when he wrote ‘finger-pointing’ songs, protesting about politics and fame. The words splashed across faux magazine covers are the grandchildren of the slogans he held up to the camera in the 1965.

Dylan’s choice of medium – the silkscreen print – is another gesture towards 1965. This was the year that he came into contact with Andy Warhol. At the time, Dylan was close to Edie Sedgwick, a young woman who starred in many of the underground movies made at Warhol’s Factory. That summer, Warhol persuaded Dylan to sit for one of his Screen Tests, a trial by camera. After enduring his silent, slow-motion portrait, Dylan toured the Factory. He saw Warhol’s monumental silver screenprint of the Double Elvis (now in MOMA, New York), and he took it home. Later Dylan acknowledged Warhol as ‘the king of pop.’ But, he went on, ‘One art critic in Warhol’s time had said that he’d give you a million dollars if you could find one ounce of hope or love in any of his work’.It is impossible for Dylan to work with silkscreen without comparisons being made with Warhol’s productions. However, Dylan’s use of the technique is deliberate and singular. He plays with the disjunctions between the text, the image and the mechanistic manner in which each work appears to be made. This is a collage, but we cannot see the joins. He has sampled brand identities, seamlessly overlaying them with impossible statements. The medium, despite all its associations with Pop and the Factory, is made to take second place to the collision of words and pictures.

Dylan never makes it easy for his audience to understand his message. He told us back in 1965, ‘You have to listen closely’. Dylan has always been a magpie. As a young singer-songwriter, he gathered and sifted, adding new words to old tunes, changing key, mood or instrument, restless, ears open. But as he said in 2004, ‘You can’t do something forever. I did it once and I can do other things now.’Bob Dylan’s art is not constrained by medium. Texts, pictures and tunes intersect and reverberate. As he wrote, ‘Folk songs were the way I explored the universe, they were pictures and the pictures were worth more than anything I could say’. And if you want to find out more, click here: http://www.halcyongallery.com/artists/bob-dylan

See for example, Christopher Rollason, ‘Tell-tale signs – Edgar Allen Poe and Bob Dylan: towards a model of intertextuality’, Atlantis, Dec. 2009, p.41 Martin Carthy interviewed by Matthew Zuckerman in 1995, quoted by Zuckerman in ‘If there’s an original thought out there, I could use it right now: The Folk Roots of Bob Dylan’, posted www.expectingrain.com, 20 Feb 1997 Chronicles: Volume One, p.174 Bob Dylan: Like a Complete Unknown, p.1 Bob Dylan: Like a Complete Unknown, p.122 Chronicles: Volume One, p.41 Chronicles: Volume One, p.18

POP GOES THE ARTIST: FROM WARHOL TO DYLAN

Something a little different - 20th C American, rather than 19th C British Art. Recently I've had a chance recently to look closely at some fascinating works of Pop Art. And it all ties in rather neatly with my work on music and the visual arts. So here's a taste of Pop culture:

Bob Dylan's Pictures:

‘The press never let up’, Dylan wrote in his autobiographical Chronicles: Volume One (2004). ‘Once in a while I would have to rise up and offer myself for an interview so they wouldn’t beat down the door.’ Dylan answers his critics by creating his own headlines. In his world, Robert Zimmerman can transform himself: as he told his audience in 1964, ‘I have my Bob Dylan mask on.’

Throughout his career, Dylan has been accused of borrowing, cutting and pasting. His 2001 album Love and Theft acknowledged as much in the title. Joni Mitchell infamously called him a plagiarist. ‘Everything about Bob is a deception’, she said in 2010. But many others take different view. He is beloved by cultural historians who write academic essays about intertextuality and his use of the ‘embedded’ quotation.The tales told in traditional songs also resurface in his works of visual art too, his prints and drawings. Greed, guilt and jealousy. Exile and tragedy. Outlaws and temptresses. The folk stories are spelt out in banner headlines. These blatant texts also take us back to Dylan’s starting-point, when he wrote ‘finger-pointing’ songs, protesting about politics and fame. The words splashed across faux magazine covers are the grandchildren of the slogans he held up to the camera in the 1965.

Dylan’s choice of medium – the silkscreen print – is another gesture towards 1965. This was the year that he came into contact with Andy Warhol. At the time, Dylan was close to Edie Sedgwick, a young woman who starred in many of the underground movies made at Warhol’s Factory. That summer, Warhol persuaded Dylan to sit for one of his Screen Tests, a trial by camera. After enduring his silent, slow-motion portrait, Dylan toured the Factory. He saw Warhol’s monumental silver screenprint of the Double Elvis (now in MOMA, New York), and he took it home. Later Dylan acknowledged Warhol as ‘the king of pop.’ But, he went on, ‘One art critic in Warhol’s time had said that he’d give you a million dollars if you could find one ounce of hope or love in any of his work’.It is impossible for Dylan to work with silkscreen without comparisons being made with Warhol’s productions. However, Dylan’s use of the technique is deliberate and singular. He plays with the disjunctions between the text, the image and the mechanistic manner in which each work appears to be made. This is a collage, but we cannot see the joins. He has sampled brand identities, seamlessly overlaying them with impossible statements. The medium, despite all its associations with Pop and the Factory, is made to take second place to the collision of words and pictures.

Dylan never makes it easy for his audience to understand his message. He told us back in 1965, ‘You have to listen closely’. Dylan has always been a magpie. As a young singer-songwriter, he gathered and sifted, adding new words to old tunes, changing key, mood or instrument, restless, ears open. But as he said in 2004, ‘You can’t do something forever. I did it once and I can do other things now.’Bob Dylan’s art is not constrained by medium. Texts, pictures and tunes intersect and reverberate. As he wrote, ‘Folk songs were the way I explored the universe, they were pictures and the pictures were worth more than anything I could say’. And if you want to find out more, click here: http://www.halcyongallery.com/artists/bob-dylan

See for example, Christopher Rollason, ‘Tell-tale signs – Edgar Allen Poe and Bob Dylan: towards a model of intertextuality’, Atlantis, Dec. 2009, p.41 Martin Carthy interviewed by Matthew Zuckerman in 1995, quoted by Zuckerman in ‘If there’s an original thought out there, I could use it right now: The Folk Roots of Bob Dylan’, posted www.expectingrain.com, 20 Feb 1997 Chronicles: Volume One, p.174 Bob Dylan: Like a Complete Unknown, p.1 Bob Dylan: Like a Complete Unknown, p.122 Chronicles: Volume One, p.41 Chronicles: Volume One, p.18

Published on June 30, 2014 07:16

January 29, 2014

Forthcoming events:Sat 8th February: The Ruskin Society b...

Forthcoming events:

Sat 8th February:

The Ruskin Society birthday lunch with illustrated talk

'The Model Wife?: Effie, Ruskin and Millais'

contact secretary@theruskinsociety.com for more details

Weds 12th February:

Jodrell DFAS

'The Invisible Woman: into the heart of Dickens'

Sat 22nd Februrary:

York CityScreen

'The Invisible Woman' pre-screening talk, 3pm

contact cityscreenyork@picturehouses.co.uk for more details

Weds 26th March:

Belfast DFAS

'The Invisible Woman: into the heart of Dickens'

Weds 2nd April:

Melksham DFAS

'The Invisible Woman: into the heart of Dickens'

Sat 8th February:

The Ruskin Society birthday lunch with illustrated talk

'The Model Wife?: Effie, Ruskin and Millais'

contact secretary@theruskinsociety.com for more details

Weds 12th February:

Jodrell DFAS

'The Invisible Woman: into the heart of Dickens'

Sat 22nd Februrary:

York CityScreen

'The Invisible Woman' pre-screening talk, 3pm

contact cityscreenyork@picturehouses.co.uk for more details

Weds 26th March:

Belfast DFAS

'The Invisible Woman: into the heart of Dickens'

Weds 2nd April:

Melksham DFAS

'The Invisible Woman: into the heart of Dickens'

Published on January 29, 2014 05:56

September 3, 2013

Events for Autumn 2013

I shall be travelling up and down the country this autumn, lecturing on Dickens and the Pre-Raphaelites. Do contact me on suzannefagencecooper@yahoo.com if you need more information about times and venues.

Forthcoming lectures:

Mon 16th Sept: Harrogate

'St.Cecilia's Halo: the Pre-Raphaelites and stained glass'

Weds 18th Sept: Market Harborough

'The Invisible Woman: into the heart of Dickens'

Tues 8th October: Dorking

'Painting and Poetry: an introduction to the Pre-Raphaelites'

Thurs 17th October: Hornsea

'Victoria's Secrets'

Tues 22nd October: Kelso

'The Model Wife: Effie Gray, Elizabeth Siddal and Jane Morris'

Weds 20th Nov: University of Bern, Switzerland

as part of the 'Gendered Interior' conference

'Through the Looking Glass: the photography of Clementina, Lady Hawarden'

We are also looking forward to a series of events (4th-11th October) in Nun Monkton, nr.York, as part of the 'Art in the Village' project. Details to follow soon.

Forthcoming lectures:

Mon 16th Sept: Harrogate

'St.Cecilia's Halo: the Pre-Raphaelites and stained glass'

Weds 18th Sept: Market Harborough

'The Invisible Woman: into the heart of Dickens'

Tues 8th October: Dorking

'Painting and Poetry: an introduction to the Pre-Raphaelites'

Thurs 17th October: Hornsea

'Victoria's Secrets'

Tues 22nd October: Kelso

'The Model Wife: Effie Gray, Elizabeth Siddal and Jane Morris'

Weds 20th Nov: University of Bern, Switzerland

as part of the 'Gendered Interior' conference

'Through the Looking Glass: the photography of Clementina, Lady Hawarden'

We are also looking forward to a series of events (4th-11th October) in Nun Monkton, nr.York, as part of the 'Art in the Village' project. Details to follow soon.

Published on September 03, 2013 03:27

April 19, 2013

New Dickens lecture & Events: Spring/Summer 2013

As historical consultant on the forthcoming film directed by Ralph Fiennes, 'The Invisible Woman', about Dickens and Nelly Ternan, I had an unprecedented opportunity to immerse myself in the Victorian world. I advised on the details of locations and costume. I thought hard about vocabulary and turns of phrase. And I tried to understand from his letters and novels how Dickens could be at once so generous, and so hard-hearted. Building on my research for this project, I have created a new illustrated lecture on The Invisible Woman: into the heart of Dickens.

Forthcoming events

8th May: Sutton Coldfield, Christopher Dresser: A pioneer of modern design?

15th May: Beverley, Christopher Dresser: A pioneer of modern design?

28th June: Portico Library, Manchester, Written out: women's letters and the Victorian art world

2nd July: Saltaire, The Pre-Raphaelites and the V&A Museum

16th September: Harrogate, St. Cecilia's Halo: Music, Sex and Death in Victorian Painting

18th September: Market Harborough, The Invisible Woman: into the heart of Dickens

for more information about times and venues, please tweet me @suzannefagence or email suzannefagencecooper@yahoo.com

Forthcoming events

8th May: Sutton Coldfield, Christopher Dresser: A pioneer of modern design?

15th May: Beverley, Christopher Dresser: A pioneer of modern design?

28th June: Portico Library, Manchester, Written out: women's letters and the Victorian art world

2nd July: Saltaire, The Pre-Raphaelites and the V&A Museum

16th September: Harrogate, St. Cecilia's Halo: Music, Sex and Death in Victorian Painting

18th September: Market Harborough, The Invisible Woman: into the heart of Dickens

for more information about times and venues, please tweet me @suzannefagence or email suzannefagencecooper@yahoo.com

Published on April 19, 2013 06:14

September 6, 2012

Forthcoming lectures - Autumn 2012

Tate Britain's exhibition, 'The Pre-Raphaelites: the Victorian Avant-Garde', is opening on 12th Sept. If you'd like to find out more about Victorian art, I'll be giving lectures all over the UK this autumn. Please email or tweet me @suzannefagence if you need more info:

Thur 13 Sept, Waterstones York, http://www.waterstones.com/waterstonesweb/displayProductDetails.do?sku=6990153

Mon 17 Sept, Harrogate: New Art for the New Woman

Fri 28 Sept, Ripon: New Art for the New Woman

Tues 2 Oct, Derby: Painting and Poetry: an introduction to the Pre-Raphaelites

Tues 9 Oct, Kendal : Christopher Dresser

Thurs 11 Oct, Mayford, Surrey : Pre-Raphaelite Art in the V&A Museum

Mon 15 Oct, Harrogate: Frederic Leighton and the Aesthetic Movement

Tues 16 Oct, Knutsford Literature Festival, http://www.knutsfordlitfest.org/booking.htm

Tues 23 Oct, Bookham, Surrey; Painting and Poetry: an introduction to the Pre-Raphaelites

Thurs 8 Nov, Harrow: Painting and Poetry: an introduction to the Pre-Raphaelites

Thurs 15 Nov, Northleach: Music, Sex and Death in Victorian Painting

Thurs 22 Nov, Oakham: Pre-Raphaelite Art in the V&A Museum

Thur 13 Sept, Waterstones York, http://www.waterstones.com/waterstonesweb/displayProductDetails.do?sku=6990153

Mon 17 Sept, Harrogate: New Art for the New Woman

Fri 28 Sept, Ripon: New Art for the New Woman

Tues 2 Oct, Derby: Painting and Poetry: an introduction to the Pre-Raphaelites

Tues 9 Oct, Kendal : Christopher Dresser

Thurs 11 Oct, Mayford, Surrey : Pre-Raphaelite Art in the V&A Museum

Mon 15 Oct, Harrogate: Frederic Leighton and the Aesthetic Movement

Tues 16 Oct, Knutsford Literature Festival, http://www.knutsfordlitfest.org/booking.htm

Tues 23 Oct, Bookham, Surrey; Painting and Poetry: an introduction to the Pre-Raphaelites

Thurs 8 Nov, Harrow: Painting and Poetry: an introduction to the Pre-Raphaelites

Thurs 15 Nov, Northleach: Music, Sex and Death in Victorian Painting

Thurs 22 Nov, Oakham: Pre-Raphaelite Art in the V&A Museum

Published on September 06, 2012 06:23

June 11, 2012

St Cecilia's Halo: Music, Sex and Death in Victorian Painting. Now on Kindle

'Music has become the modern art’, Macmillan’s Magazine, July 1876

'Music has become the modern art’, Macmillan’s Magazine, July 1876 Rossetti, Burne-Jones, Leighton and Whistler: four radical Victorian artists, who embraced the idea of painting music. They understood that music suggested many meanings to Victorian audiences: spirituality, sex, death. The slippery nature of its symbolism made it attractive to Aesthetic artists. Musical subjects, often combined with seductive images of women, sidestepped the constraints of narrative and moral frameworks. Even conventional subjects, like the figure of St. Cecilia, could be subverted, to create new and troubling works of art. In the 1850s, music was usually signified by esoteric props: organs, psalteries, flutes. But as musical ideas started to suffuse the concrete arts of painting and design, so music stopped being a collection of unexpected objects, and became the subject.

This study offers a fresh reading of familiar Pre-Raphaelite and Aesthetic images from 'The Golden Stairs' to 'The Awakening Conscience'. By analysing the music in these paintings, we suddenly see connections between works that look, on the surface, so different. Music links Leighton's sensual classicism, Rossetti's medieval fantasies, Burne-Jones's androgynous beauties and Whistler's colour-harmonies.

Rossetti, Whistler and their Aesthetic colleagues recognised that realism was a cul-de-sac. Instead art should glimpse a space where all senses were satisfied, where nature, for once, sang in tune. As music did not try to replicate the real or the visible, it offered the ideal pretext for exploring a landscape of the imagination.

Read the full work on Kindle now: http://www.amazon.co.uk/St-Cecilias-Halo-Victorian-ebook/dp/B00873GPNS

Published on June 11, 2012 02:53

May 23, 2012

A Pre-Raphaelite Masterpiece in Yorkshire: the stained glass of St Mary's, Nun Monkton

I thought I would share with you some of the research I did for a fund-raising lecture for the village church.

The East Window of St. Mary’s Church, Nun Monkton

Edward Burne-Jones, The Virgin with St. Anne

This unexpected masterpiece, tucked away in a small Yorkshire village, fulfilled the desire of the artist, Edward Burne-Jones (1833-1898) to create a sense of wonder through his work. He confessed ‘I want big things to do and vast spaces and for people to see them and say ‘Oh!’, only ‘Oh!’.

1. Why was the glass commissioned?2. Who designed it?3. What does each section mean?

1. Why was the glass commissioned?St. Mary’s Church, Nun Monkton is the only remnant of the medieval Benedictine nunnery that gave the village its name. Founded in 1153, it was probably built on the site of a pre-Conquest hermitage. The architecture of the church shows the transition between the Romanesque and Gothic styles, and is inch-perfect. After the dissolution of the nunnery in 1536 under Henry VIII, the priory chapel became the parish church. But the Reformation in worship meant that the building was radically transformed. The East end, which had been the focal point of the Roman Catholic Mass, was now a blank wall with plain glass windows and a few memorials. A print hanging near the font shows what it looked like in the early 19th century.

The interior of the church remained plain and white-washed until the mid 19th century when, throughout Victorian Britain, there was a revival of interest in medieval buildings. This was accompanied by a desire to inspire greater devotion in the congregation. The reinvigoration of the Church of England was partly a response to the challenge of Non-Conformist churches, like the Methodists and Baptists. They appealed to the working classes through uplifting sermons and popular new hymns.

Some in the Church of England believed that the best way to encourage worship was to focus on holiness. They wanted to demonstrate that Church should be different from the everyday, by increasing the sense of ritual, and concentrating on the ‘beauty of holiness’. This strand within the Church grew out of debates in Oxford in the 1840s, and so became known as Oxford movement. Some aspects of the movement were very controversial, like having candles on altars, using incense, or priests wearing embroidered robes. But they were intended to add to the sense that the act of worship was special, and also to look back to the highpoint of Christianity in Britain in the Middle Ages. This was part of greater stirring of interest in the medieval: the Gothic Revival.

This historical context helps to explain why the people of Nun Monkton were prepared to pay so much for the restoration of their church, and also why the East window looks like it does.

Between 1869 and 1873, the East end of the Church was made Gothic again. It became the focus for the ritual of communion and the actions of the priest. The Gothic was not just a style, but a way of thinking about art and life. It was based on natural forms of leaves, flowers and trees. Victorian commentators claimed that the Classical Georgian architecture of the 18th century, was enslaved by the need to be exact. It was based on uniformity and straight lines. We only have to think of the Royal Crescent in Bath – a perfect sweep of identical houses – to understand this principle. The Gothic, by contrast, was free to adapt to needs of the people who used a building.

The great propagandist for Gothic architecture, John Ruskin, made the Victorians look at medieval buildings afresh. He showed them how the best of the medieval could be recreated for the modern world. Ruskin demonstrated the continuing vitality of the Gothic style: it could ‘coil into a staircase, [or] spring into a spire, with undegraded grace and unexhausted energy’. The Gothic was not just about pointed arches, but about ‘grace and energy’ in buildings and in their decoration. The stained glass windows of Nun Monkton are a perfect example of the Gothic revival in practice.

The people of Nun Monkton were caught up in this enthusiasm. The Lord of the Manor, and owner of Priory, Isaac Crawhall led them in a campaign to beautify the church. It would no longer be the bare box of Georgian times. Now it was full of colour and decoration, with new glass, pews and pulpit.

The restoration took place between 1869 and the installation of East Window in 1873. The architect was John H Walton. Unfortunately we know very little about him, except that he also designed John Smith’s Brewery in Tadcaster. His offices were registered in Buckingham Street, London, and his plans for Nun Monkton Church were illustrated in the Building News in 1884. The cost of restoration was £4,400, at a time when £300 per year would be respectable income for middle class man to support his wife, children and probably a couple of servants. In the late 1860s, only 300 people were living in village, but they all tried to contribute to the cost. Some local women, for example, made needlework to help with fundraising.

The bulk of cost - £2500 - was for rebuilding the chancel. This is the most important part of church, where the altar now stands. The church was lengthened by 2 bays, choir stalls were added, and the new East Window was installed. This work was paid for by Isaac Crawhall personally. He originally came from County Durham, and had bought the Priory in 1860.

It is not clear how much the window itself cost. For comparison, we know that one of Isaac Crawhall’s daughters paid £1000 for three other windows in the West End, above the organ, showing the archangels – Gabriel, Raphael and Michael - and saints. These include the local abbess St. Hilda of Whitby, St. Chad with Lichfield cathedral and St. Etheldred. The windows were added as a memorial to Isaac Crawhall himself in 1901.

The East window seems to have been dedicated as a memorial to Isaac’s wife Ann who died 1860. We can trace the history of the Crawhall family on their tomb, which is in the churchyard, near Priory Wall. It is a granite cross, with an iron railing around it.

So the window remembers a wife and mother. It is a work of art in praise of women. On a personal level, it commemorates the life of Ann Crawhall. On another level, it recognises that the church was originally part of a nunnery. And of course, it reminds us that this church is dedicated the Virgin Mary.

The idea of celebrating women is woven into the designs for the glass. This theme probably encouraged Morris and Company to accept the commission; womanhood was a favourite subject of William Morris (1834-1896) and his friends. As young men, they had scandalised a stuffy Oxford don who asked the artists how they imagined heaven. They replied that it would be ‘a garden full of stunners’ – stunner was slang for a beautiful woman. So here is their vision of heaven, full of distinctive Pre-Raphaelite women with long thick hair, strong faces, and curvaceous figures.

Edward Burne-Jones, The Annunciation

2. Who designed the glass? The early 1870s, when this window commissioned, are regarded as the highpoint of stained glass production by Morris and Company. The firm had begun making stained glass in 1861 in their first workshops in central London. They produced glass for church decoration as well as for homes. It was part of their desire to beautify British houses and public buildings, not just through their designs for wallpaper and curtains, but by making everything from tiles and wine glasses to cushion covers and light fittings. In the early years, stained glass design was the mainstay of their business. It supported the other branches of their practice. Morris began by employing just 2 experienced craftsmen, a glass painter and a fret glazier (who puts the jigsaw of coloured glass together). They were helped by 2 boys. Within a year, the workshop had expanded until there were 12 men and boys working through the stained glass order-book.

3. How were the windows made? Morris and Company bought in coloured glass from Powell and Son, a well established source. (They later supplied the West windows, designed in-house by J.W. Brown.) This raw material was known as ‘pot metal glass’. Morris cared deeply about every stage of production in his workshops, but did not feel compelled to make his own pot metal as Powell and Son lived up to his exacting standards. The glass was cut to fit the pattern, and then the details were painted on. Finally all the pieces were assembled, following designs created by Morris’s colleagues. These included one of the original Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, the painter D. G. Rossetti, his old friend Ford Madox Brown, and the architect Philip Webb. Morris himself also designed some of the figures.

The most prolific designer for Morris’s firm was Edward Burne-Jones. He had worked on stained glass from the earliest days of his career. Even before Morris and Company had been founded, he had created designs for Powell in 1857. This had been one of his first paid jobs as artist. By the 1870s, Burne-Jones had taken over bulk of design work for Morris and Company.

Edward Burne-Jones, The Nativity

The art of stained-glass manufacture is in selecting colours. This is what makes Morris and Company glass so distinctive. Morris chose strong but not acid colours – ruby rather than scarlet, leaf green rather than turquoise. Other Victorian companies had begun to make Gothic Revival glass. We can see an example from late 1850s on the North Wall of Nun Monkton’s church, dedicated to Isaac Crawhall’s daughter Maria who died in 1857, aged 20. Comparing this window with the great East window, we can appreciate the shift in style and approach in the intervening 15 years. Maria’s window has geometric borders, cramped figures, and colours that grate. The designer has attempted to recreate Medieval feel, and it is certainly a very high quality product. But when we contrast this with Morris’s window, we recognise how stained glass design can be inspired by the Middle Ages, yet still remain fluid, glowing, and immediate.

The aim of Morris and his craftsmen, once they had established a colour-scheme, was to select materials that would keep painting to a minimum. The ideal was to create folds of fabric, or waves of water through the innate colouring of pot metal. This has been successfully achieved, for example, in Joseph’s ruby robes in the central panel of the Nativity. Then there was the skill required in piecing the glass together, so that the glazing bars followed the lines of composition. They should not interfere with the design, but enhance it, as if they are part of the drawing. No-one wants glazing bars cutting across faces or hands. They should act as a web that stands between us and the light.

The craftsmen were supervised by Morris. He was obsessive and passionate about his work, wanting to unravel every detail of design and production. He was well-known as a poet before he started Morris and Company. In fact, he said that if you could not compose poetry while also weaving a tapestry, you were no good as a poet. A larger-than-life figure, he wore a full beard and by the 1870s was growing stout. He was an adventurer, who particularly loved travelling to Iceland. He liked extremes. Morris was a genius at pattern-making. He could take the natural forms of leaves and flowers, and transform them into repeating designs, but without losing the individuality of the original.

The results can be seen here in the stained glass, with its intricate background of green tendrils and tiny white flowers. These tendrils hold together and harmonize all the figures. Friends described how easily and joyfully he created these patterns. He would take a large sheet of paper, one pot of black ink, and another of white. Using a brush he would stroke the outlines onto the paper. It looked as if he were stroking a cat. There is a sense of flowing pleasure in the creation of these natural networks.

The glass makers had to translate his brush and ink patterns into the brittle medium of glass, while still maintaining sense of fluidity. By 1873 when this window installed, they were helped in this process of translation, by using photography to enlarge Morris’s drawings.

From the early 1870s, Burne-Jones was designing most of the figures for the workshop. He worked on these in the evenings after dinner. His wife described how, like Morris, the shapes flowed out of his hand onto the paper: ‘he made the designs without hesitation,… it seemed as if they must have already been there, and his hand were only removing a veil. The soft scraping sound of the charcoal in the long smooth lines comes back to me, together with his momentary exclamation of impatience when the [charcoal] stick snapped off short, as it often did, and fell to the ground.’

Burne-Jones and William Morris had met at Oxford, and had been best friends ever since. They had made a decision together to become artists. They were two very different characters. Burne-Jones had a mischievous sense of humour, but was less robust than Morris, and more introspective. He delighted in the Middle Ages, which seemed to offer an ideal alternative to the industrialised landscapes of his childhood. He had been born in Birmingham, into the lower middle class. He was brought up by his father, a picture frame maker, as his mother had died soon after his birth. He did well at school, and made it to Oxford, but never forgot the dirt, the oppressive buildings and the poverty he had grown up with. He looked to the past - the world of Chaucer and Malory – as a time of great deeds, chivalry, and open spaces. He created a landscape of the imagination, and almost felt as if he lived alongside the knights and ladies of his pictures. The medieval world was his true home.

Why were Morris and Burne-Jones commissioned by Isaac Crawhall to create a window for Nun Monkton? We do not know for sure, but there are various theories. It could be simply that Morris and Company were the most successful glass makers of their generation. They had caused a stir at the International Exhibition in London in 1862 with their designs. Perhaps the Crawhalls or their architect had seen their work in London or elsewhere and simply liked the look of it, and wanted to buy the best. There are other local connections. Morris and Co. had installed windows in St. Martin’s Church, Scarborough from 1862. Our Annunciation panel is a version of the Rose window in Scarborough. The firm also installed windows in Knaresborough in 1873, so clearly they had become fashionable in this part of Yorkshire.

It is possible that the commission came about because of Morris and Burne-Jones’s links with the Howard family, who owned Castle Howard. They were good friends of George Howard and his wife Rosalind. Howard was a well-regarded artist. Burne-Jones said he produced ‘simply the best watercolour work…[of] the present day…the most refined, the most poetic.’ The couple were part of a vibrant artistic circle, and they invited Burne-Jones and Morris to decorate the drawing room of their London house in Kensington. George’s uncle owned Castle Howard, and commissioned Morris and Company to create stained glass windows for his chapel. These were installed in 1872. Perhaps this contributed to the fame of the firm in Yorkshire. There is sadly no evidence that Morris or Burne-Jones ever visited Nun Monkton, but it would be good to think that they stopped off here on way North to George and Rosalind Howard’s country house in Naworth in Cumberland. We know that they travelled to Naworth in the late summer of 1873 when this window was being fitted. It is interesting to imagine them coming up river from York. Morris always loved boats and fishing. The pair would have enjoyed poking about here, but might have been anxious about the extent of the restoration work. In fact, Nun Monkton is lucky to have the window at all. In 1877 Morris founded the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings. After that he refused to supply modern glass for medieval churches. He had been appalled by insensitive restoration of old buildings, notoriously at St. Mark’s in Venice, but also in Burford in Oxfordshire. He felt the restorers were stripping away the centuries to try to create a sanitised version of the Gothic. Morris tried to persuade architects that old buildings should show their age. He also hated grandiose schemes that tried to turn parish churches into ‘small French cathedrals.’ His business manager described the Morris and Comapany ethos. It was essentially English in character. Churches should be ‘small as our landscape is small, sweet, picturesque, homely, farmyardish.’

At present we do not know exactly how the design was commissioned and ended up here. But we do know the Crawhall’s got their money’s worth. This is one of the finest Morris and Company windows to be seen anywhere.

William Morris, St. Cecilia’s angel

3. What does each section mean?It helps to imagine the design as a cartoon strip, with the same figures appearing in different boxes, and several locations appearing one after another. The window tells a coherent story, but on a number of levels.

The side panels are a vision of heaven with musician angels, three on each side. These were designed by William Morris in the 1860s. They appear on tiles made by Morris and Company, as well as in stained glass windows in many other churches. They were originally drawn without wings, as they were intended for a domestic setting. When the wings were added, they became angels.

Why do they make music? The musical instruments create an extra dimension of imagined sound, that is meant to evoke ‘music of the spheres’. It is something beyond our hearing, but we can still imagine it. Specifically, music was associated in medieval religion with the Virgin Mary. Many saint’s tales described her with musical attendants.

The window design also gives a nod towards the legend of St Cecilia, the patroness of music. The 3rd angel down on the South side is a female figure playing a little portative organ, which is the Saint’s traditional accessory. She wears garland of flowers around head, which provides a clue to the legend of St Cecilia. According to the story, the flowers were given to Cecilia by her guardian angel as proof of her connection with heaven. They were meant to reinforce her faith. This was a favourite subject of Morris’s friends Burne-Jones and Rossetti. So here is Cecilia’s guardian angel playing the heavenly music that Cecilia heard as she prepared to get married. The music encouraged her to turn away from the wedding ceremony, stay celibate, and ultimately to accept her martyrdom at the hands of the Romans.

We can compare the angels by Morris in the outer panels with the other female figures by Burne-Jones. Morris’s female figures are fairly sturdy and substantial, while Burne-Jones’s girls seem more willowy. Burne-Jones designed all the other figures. We can look at these section by section.

The scenes at the base, and in the centre are all in praise of Virgin Mary. They tell her story.

On the pulpit side, Mary is shown as young girl being taught by her mother, Anne. The Education of the Virgin Mary is a traditional subject. It emphasises Mary growing up as spiritual child, learning the scriptures, and preparing for her role as Mother of God. Also, the subject is particularly appropriate in this context, as the East window is a memorial to Isaac’s wife Anne. Like St Anne, she will be remembered as a virtuous mother. On the outside wall of the East End of the church, there is an inscription explaining that the restoration project was undertaken in memory of Anne. This inscription can now only be seen from the private Priory gardens.

The middle scene at the base is the Annunciation. Here the angel Gabriel is bringing word to the Virgin Mary that she will bear the child Jesus. This is the critical moment of God’s intervention in history. As in the first scene, Mary is shown as a pious girl, praying at her prie-dieu. Burne-Jones played around with this figure group over many years, starting in 1863. In this version of events, he imagines a bold encounter, characterised by billowing robes and dramatically twisting bodies.

Edward Burne-Jones, The Repose on the Flight into Egypt

On the Priory side of the church, there is a design made especially for Nun Monkton. (The rest of the images had been used previously in different configurations for other commissions). This third scene is the Repose on the Flight into Egypt. Mary and Jesus are escaping from Herod. Burne-Jones’s account book says he charged Morris and Company £10 for this design in June 1873. It would be hard to identify the subject without Burne-Jones’s own notes. The Virgin is not wearing the same colour robes as in other scenes, which would have helped us to identify her. And there are no clues in the background: often this subject would include details like camels or pyramids, but Burne-Jones clearly thought these would be a distraction. Here is simply a woman caring for baby. The image is stripped down to basics.

At the heart of the East window is the Birth of Christ, his Nativity. Again the Virgin Mary is prominent. The Baby is lying on flowery grass, not in a manger. This is a striking image, and not straightforward so it is worth taking some time to look at all the details. Heaven and earth are coming into contact. Only a band of waves or clouds separates the red-winged angels from the humans. The individualised faces of angels give the impression that we should recognise them. They are singing ‘et in terra pax’ (‘and in earth, peace’).

The angels are looking over edge of heaven at the figures gathered around Christ. One angel has descended to earth, and is playing music. Again, this musical intervention creates the sensation of an extra dimension of sound and movement. But the angel’s face is strained. He seems to be singing, but it is a rather jarring note. On other side, towards the Priory, are two standing men. They are probably meant as shepherds, but there are no obvious sheep. They stand in for us, the onlookers, the people who Christ has come to save. Beneath the whole scene is the Latin inscription ‘verbum caro factum est, alleluia, alleluia’ (‘the word was made flesh, alleluia, alleluia’).

Above the heads of the shepherds, the great star shines, and smaller stars glimmer. There is a sense of the immensity of space. Joseph and Mary seem overawed by the presence of the child. They contemplate Him as he lies on the grass sprinkled with forget-me-nots.

This is no shed or stable. This is the entrance to a cave. Blocks of stone frame the figures. The prominence of these rocks might make us uneasy, as they create a blank at the heart of the image. Everything else whirls around this static space. For all the singing, this is a scene of contemplation and anticipation. The stones prefigure the great stone rolled across the grave after the Crucifixion. The Child is bound and stretched out on the grass, not held by his mother and cuddled. In the beginning, we have the seeds of the end of the story. It is as if we are left to ponder it: the implications of this moment of connection between heaven and earth. We are shown what Mary has been given, and what she will lose at Easter.

This meditation on the subjects in the East Window should not leave us down-hearted. We can enjoy the patterns of colour woven across the different scenes, creating a harmonious whole. The window can be appreciated as a vision of light and colour, held together by the underlying web of Morris’s tendrils. But it can also be unpicked. Each scene can help us to understand the human element in the story of Salvation. We are constantly reminded of motherhood, and holy women.

Morris once declared ‘My work is the embodiment of dreams’, and in this small corner of Yorkshire he offered a glimpse of something beyond the everyday, a hint of the beauty that lies just out of reach. We should be grateful to Isaac Crawhall for his generosity. Sadly he only had four years to enjoy the East window. He died in 1877. But we are thankful for his foresight in giving this gift to the people of Nun Monkton.

The East Window of St. Mary’s Church, Nun Monkton

Edward Burne-Jones, The Virgin with St. Anne

This unexpected masterpiece, tucked away in a small Yorkshire village, fulfilled the desire of the artist, Edward Burne-Jones (1833-1898) to create a sense of wonder through his work. He confessed ‘I want big things to do and vast spaces and for people to see them and say ‘Oh!’, only ‘Oh!’.

1. Why was the glass commissioned?2. Who designed it?3. What does each section mean?

1. Why was the glass commissioned?St. Mary’s Church, Nun Monkton is the only remnant of the medieval Benedictine nunnery that gave the village its name. Founded in 1153, it was probably built on the site of a pre-Conquest hermitage. The architecture of the church shows the transition between the Romanesque and Gothic styles, and is inch-perfect. After the dissolution of the nunnery in 1536 under Henry VIII, the priory chapel became the parish church. But the Reformation in worship meant that the building was radically transformed. The East end, which had been the focal point of the Roman Catholic Mass, was now a blank wall with plain glass windows and a few memorials. A print hanging near the font shows what it looked like in the early 19th century.

The interior of the church remained plain and white-washed until the mid 19th century when, throughout Victorian Britain, there was a revival of interest in medieval buildings. This was accompanied by a desire to inspire greater devotion in the congregation. The reinvigoration of the Church of England was partly a response to the challenge of Non-Conformist churches, like the Methodists and Baptists. They appealed to the working classes through uplifting sermons and popular new hymns.

Some in the Church of England believed that the best way to encourage worship was to focus on holiness. They wanted to demonstrate that Church should be different from the everyday, by increasing the sense of ritual, and concentrating on the ‘beauty of holiness’. This strand within the Church grew out of debates in Oxford in the 1840s, and so became known as Oxford movement. Some aspects of the movement were very controversial, like having candles on altars, using incense, or priests wearing embroidered robes. But they were intended to add to the sense that the act of worship was special, and also to look back to the highpoint of Christianity in Britain in the Middle Ages. This was part of greater stirring of interest in the medieval: the Gothic Revival.

This historical context helps to explain why the people of Nun Monkton were prepared to pay so much for the restoration of their church, and also why the East window looks like it does.

Between 1869 and 1873, the East end of the Church was made Gothic again. It became the focus for the ritual of communion and the actions of the priest. The Gothic was not just a style, but a way of thinking about art and life. It was based on natural forms of leaves, flowers and trees. Victorian commentators claimed that the Classical Georgian architecture of the 18th century, was enslaved by the need to be exact. It was based on uniformity and straight lines. We only have to think of the Royal Crescent in Bath – a perfect sweep of identical houses – to understand this principle. The Gothic, by contrast, was free to adapt to needs of the people who used a building.

The great propagandist for Gothic architecture, John Ruskin, made the Victorians look at medieval buildings afresh. He showed them how the best of the medieval could be recreated for the modern world. Ruskin demonstrated the continuing vitality of the Gothic style: it could ‘coil into a staircase, [or] spring into a spire, with undegraded grace and unexhausted energy’. The Gothic was not just about pointed arches, but about ‘grace and energy’ in buildings and in their decoration. The stained glass windows of Nun Monkton are a perfect example of the Gothic revival in practice.

The people of Nun Monkton were caught up in this enthusiasm. The Lord of the Manor, and owner of Priory, Isaac Crawhall led them in a campaign to beautify the church. It would no longer be the bare box of Georgian times. Now it was full of colour and decoration, with new glass, pews and pulpit.

The restoration took place between 1869 and the installation of East Window in 1873. The architect was John H Walton. Unfortunately we know very little about him, except that he also designed John Smith’s Brewery in Tadcaster. His offices were registered in Buckingham Street, London, and his plans for Nun Monkton Church were illustrated in the Building News in 1884. The cost of restoration was £4,400, at a time when £300 per year would be respectable income for middle class man to support his wife, children and probably a couple of servants. In the late 1860s, only 300 people were living in village, but they all tried to contribute to the cost. Some local women, for example, made needlework to help with fundraising.

The bulk of cost - £2500 - was for rebuilding the chancel. This is the most important part of church, where the altar now stands. The church was lengthened by 2 bays, choir stalls were added, and the new East Window was installed. This work was paid for by Isaac Crawhall personally. He originally came from County Durham, and had bought the Priory in 1860.

It is not clear how much the window itself cost. For comparison, we know that one of Isaac Crawhall’s daughters paid £1000 for three other windows in the West End, above the organ, showing the archangels – Gabriel, Raphael and Michael - and saints. These include the local abbess St. Hilda of Whitby, St. Chad with Lichfield cathedral and St. Etheldred. The windows were added as a memorial to Isaac Crawhall himself in 1901.

The East window seems to have been dedicated as a memorial to Isaac’s wife Ann who died 1860. We can trace the history of the Crawhall family on their tomb, which is in the churchyard, near Priory Wall. It is a granite cross, with an iron railing around it.

So the window remembers a wife and mother. It is a work of art in praise of women. On a personal level, it commemorates the life of Ann Crawhall. On another level, it recognises that the church was originally part of a nunnery. And of course, it reminds us that this church is dedicated the Virgin Mary.

The idea of celebrating women is woven into the designs for the glass. This theme probably encouraged Morris and Company to accept the commission; womanhood was a favourite subject of William Morris (1834-1896) and his friends. As young men, they had scandalised a stuffy Oxford don who asked the artists how they imagined heaven. They replied that it would be ‘a garden full of stunners’ – stunner was slang for a beautiful woman. So here is their vision of heaven, full of distinctive Pre-Raphaelite women with long thick hair, strong faces, and curvaceous figures.

Edward Burne-Jones, The Annunciation

2. Who designed the glass? The early 1870s, when this window commissioned, are regarded as the highpoint of stained glass production by Morris and Company. The firm had begun making stained glass in 1861 in their first workshops in central London. They produced glass for church decoration as well as for homes. It was part of their desire to beautify British houses and public buildings, not just through their designs for wallpaper and curtains, but by making everything from tiles and wine glasses to cushion covers and light fittings. In the early years, stained glass design was the mainstay of their business. It supported the other branches of their practice. Morris began by employing just 2 experienced craftsmen, a glass painter and a fret glazier (who puts the jigsaw of coloured glass together). They were helped by 2 boys. Within a year, the workshop had expanded until there were 12 men and boys working through the stained glass order-book.

3. How were the windows made? Morris and Company bought in coloured glass from Powell and Son, a well established source. (They later supplied the West windows, designed in-house by J.W. Brown.) This raw material was known as ‘pot metal glass’. Morris cared deeply about every stage of production in his workshops, but did not feel compelled to make his own pot metal as Powell and Son lived up to his exacting standards. The glass was cut to fit the pattern, and then the details were painted on. Finally all the pieces were assembled, following designs created by Morris’s colleagues. These included one of the original Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, the painter D. G. Rossetti, his old friend Ford Madox Brown, and the architect Philip Webb. Morris himself also designed some of the figures.

The most prolific designer for Morris’s firm was Edward Burne-Jones. He had worked on stained glass from the earliest days of his career. Even before Morris and Company had been founded, he had created designs for Powell in 1857. This had been one of his first paid jobs as artist. By the 1870s, Burne-Jones had taken over bulk of design work for Morris and Company.

Edward Burne-Jones, The Nativity

The art of stained-glass manufacture is in selecting colours. This is what makes Morris and Company glass so distinctive. Morris chose strong but not acid colours – ruby rather than scarlet, leaf green rather than turquoise. Other Victorian companies had begun to make Gothic Revival glass. We can see an example from late 1850s on the North Wall of Nun Monkton’s church, dedicated to Isaac Crawhall’s daughter Maria who died in 1857, aged 20. Comparing this window with the great East window, we can appreciate the shift in style and approach in the intervening 15 years. Maria’s window has geometric borders, cramped figures, and colours that grate. The designer has attempted to recreate Medieval feel, and it is certainly a very high quality product. But when we contrast this with Morris’s window, we recognise how stained glass design can be inspired by the Middle Ages, yet still remain fluid, glowing, and immediate.

The aim of Morris and his craftsmen, once they had established a colour-scheme, was to select materials that would keep painting to a minimum. The ideal was to create folds of fabric, or waves of water through the innate colouring of pot metal. This has been successfully achieved, for example, in Joseph’s ruby robes in the central panel of the Nativity. Then there was the skill required in piecing the glass together, so that the glazing bars followed the lines of composition. They should not interfere with the design, but enhance it, as if they are part of the drawing. No-one wants glazing bars cutting across faces or hands. They should act as a web that stands between us and the light.

The craftsmen were supervised by Morris. He was obsessive and passionate about his work, wanting to unravel every detail of design and production. He was well-known as a poet before he started Morris and Company. In fact, he said that if you could not compose poetry while also weaving a tapestry, you were no good as a poet. A larger-than-life figure, he wore a full beard and by the 1870s was growing stout. He was an adventurer, who particularly loved travelling to Iceland. He liked extremes. Morris was a genius at pattern-making. He could take the natural forms of leaves and flowers, and transform them into repeating designs, but without losing the individuality of the original.

The results can be seen here in the stained glass, with its intricate background of green tendrils and tiny white flowers. These tendrils hold together and harmonize all the figures. Friends described how easily and joyfully he created these patterns. He would take a large sheet of paper, one pot of black ink, and another of white. Using a brush he would stroke the outlines onto the paper. It looked as if he were stroking a cat. There is a sense of flowing pleasure in the creation of these natural networks.

The glass makers had to translate his brush and ink patterns into the brittle medium of glass, while still maintaining sense of fluidity. By 1873 when this window installed, they were helped in this process of translation, by using photography to enlarge Morris’s drawings.

From the early 1870s, Burne-Jones was designing most of the figures for the workshop. He worked on these in the evenings after dinner. His wife described how, like Morris, the shapes flowed out of his hand onto the paper: ‘he made the designs without hesitation,… it seemed as if they must have already been there, and his hand were only removing a veil. The soft scraping sound of the charcoal in the long smooth lines comes back to me, together with his momentary exclamation of impatience when the [charcoal] stick snapped off short, as it often did, and fell to the ground.’

Burne-Jones and William Morris had met at Oxford, and had been best friends ever since. They had made a decision together to become artists. They were two very different characters. Burne-Jones had a mischievous sense of humour, but was less robust than Morris, and more introspective. He delighted in the Middle Ages, which seemed to offer an ideal alternative to the industrialised landscapes of his childhood. He had been born in Birmingham, into the lower middle class. He was brought up by his father, a picture frame maker, as his mother had died soon after his birth. He did well at school, and made it to Oxford, but never forgot the dirt, the oppressive buildings and the poverty he had grown up with. He looked to the past - the world of Chaucer and Malory – as a time of great deeds, chivalry, and open spaces. He created a landscape of the imagination, and almost felt as if he lived alongside the knights and ladies of his pictures. The medieval world was his true home.

Why were Morris and Burne-Jones commissioned by Isaac Crawhall to create a window for Nun Monkton? We do not know for sure, but there are various theories. It could be simply that Morris and Company were the most successful glass makers of their generation. They had caused a stir at the International Exhibition in London in 1862 with their designs. Perhaps the Crawhalls or their architect had seen their work in London or elsewhere and simply liked the look of it, and wanted to buy the best. There are other local connections. Morris and Co. had installed windows in St. Martin’s Church, Scarborough from 1862. Our Annunciation panel is a version of the Rose window in Scarborough. The firm also installed windows in Knaresborough in 1873, so clearly they had become fashionable in this part of Yorkshire.

It is possible that the commission came about because of Morris and Burne-Jones’s links with the Howard family, who owned Castle Howard. They were good friends of George Howard and his wife Rosalind. Howard was a well-regarded artist. Burne-Jones said he produced ‘simply the best watercolour work…[of] the present day…the most refined, the most poetic.’ The couple were part of a vibrant artistic circle, and they invited Burne-Jones and Morris to decorate the drawing room of their London house in Kensington. George’s uncle owned Castle Howard, and commissioned Morris and Company to create stained glass windows for his chapel. These were installed in 1872. Perhaps this contributed to the fame of the firm in Yorkshire. There is sadly no evidence that Morris or Burne-Jones ever visited Nun Monkton, but it would be good to think that they stopped off here on way North to George and Rosalind Howard’s country house in Naworth in Cumberland. We know that they travelled to Naworth in the late summer of 1873 when this window was being fitted. It is interesting to imagine them coming up river from York. Morris always loved boats and fishing. The pair would have enjoyed poking about here, but might have been anxious about the extent of the restoration work. In fact, Nun Monkton is lucky to have the window at all. In 1877 Morris founded the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings. After that he refused to supply modern glass for medieval churches. He had been appalled by insensitive restoration of old buildings, notoriously at St. Mark’s in Venice, but also in Burford in Oxfordshire. He felt the restorers were stripping away the centuries to try to create a sanitised version of the Gothic. Morris tried to persuade architects that old buildings should show their age. He also hated grandiose schemes that tried to turn parish churches into ‘small French cathedrals.’ His business manager described the Morris and Comapany ethos. It was essentially English in character. Churches should be ‘small as our landscape is small, sweet, picturesque, homely, farmyardish.’

At present we do not know exactly how the design was commissioned and ended up here. But we do know the Crawhall’s got their money’s worth. This is one of the finest Morris and Company windows to be seen anywhere.

William Morris, St. Cecilia’s angel

3. What does each section mean?It helps to imagine the design as a cartoon strip, with the same figures appearing in different boxes, and several locations appearing one after another. The window tells a coherent story, but on a number of levels.

The side panels are a vision of heaven with musician angels, three on each side. These were designed by William Morris in the 1860s. They appear on tiles made by Morris and Company, as well as in stained glass windows in many other churches. They were originally drawn without wings, as they were intended for a domestic setting. When the wings were added, they became angels.