Suzanne Fagence Cooper's Blog, page 2

March 2, 2018

Victorian Giants: Clementina, Lady Hawarden

'Studies from Life'Clementina, Lady Hawarden: Victorian photographer (1822-1865)

The photographic object is perishable: as Barthes explains, it is ‘mortal: like a living organism it is born on the level of sprouting silver grains, it flourishes a moment, then ages…Attacked by light, by humidity, it fades, weakens, vanishes’.And if the papery print is mortal, so is the person contained within it. The girls who are lovingly watched by their mother, complicit, aware of their part in the performance of youth and beauty, are long dead. They are now only to be found, to use Barthes phrase, in ‘this image which produces Death while trying to preserve life’. But, in the same breath, we are aware of the paradox that their delightful posing can now only be enjoyed in the hush of a museum, or on a computer screen. The young women have gone, the house has gone, only the fragile photographic paper survives.

The photographic object is perishable: as Barthes explains, it is ‘mortal: like a living organism it is born on the level of sprouting silver grains, it flourishes a moment, then ages…Attacked by light, by humidity, it fades, weakens, vanishes’.And if the papery print is mortal, so is the person contained within it. The girls who are lovingly watched by their mother, complicit, aware of their part in the performance of youth and beauty, are long dead. They are now only to be found, to use Barthes phrase, in ‘this image which produces Death while trying to preserve life’. But, in the same breath, we are aware of the paradox that their delightful posing can now only be enjoyed in the hush of a museum, or on a computer screen. The young women have gone, the house has gone, only the fragile photographic paper survives.  Hawarden made the majority of her photographs in her home in South Kensington. The newly-built townhouse at 5 Princes Gate was filled with her family of eight daughters and one surviving son. Throughout her career as a photographer, Hawarden was almost constantly pregnant: she had her first child Isabella Grace in 1846 and her youngest daughter was born in May 1864. Yet very few of her pictures represent a conventional family interior. A stereoscopic image of two of her girls stands out from the collection precisely because of its apparent normality. [Figure 1, V&A PH.457:499-1968] Isabella Grace is seated in a tub chair, and young Clementina is on a low stool. One is reading and the other sewing. They are shown in an unostentatious morning room, with prints above the fireplace. These pictures within pictures hint at the artistic connections of the family. The landscapes are etchings by Seymour Haden, in an advanced Whistlerian manner, but there is also a popular print of cherubs from Raphael’s Sistine Madonna. This photograph places Hawarden firmly within her mid-Victorian context. Her daughters are spending their time in suitable feminine occupations. Yet this ordinariness is undermined by the extraordinary fact that we know their mother is standing behind a camera in the corner of the room. She has chosen to record this moment, in duplicate, to be looked at later in a stereoscopic viewer that will make the whole scene appear in 3-D. The complicated doubling and playing with perception is heightened by the girls’ clothes. They are wearing identical dresses with fine dark stripes on a white background, and contrasting cuffs and hems. The stripes of their dresses are at odds with the ivy patterned upholstery on the chair and the insistent diamonds of the carpet and wallpaper. The girls keep their eye on their work, so we can study them in profile. This interior, which corresponds in many ways to the expectations of orthodox Victorian taste, has been made queer or peculiar by Hawarden’s decision to freeze it on the prepared plate of her camera. She encourages us to study it, to note how the focus shifts from one lens to the other, to dwell on the folds of the matching dresses, and to try to resolve the design of the wallpaper. But this is not an experiment she cares to repeat. The majority of her photographs are taken in bare rooms, set with props and screens, or in the open air in Ireland.

Hawarden made the majority of her photographs in her home in South Kensington. The newly-built townhouse at 5 Princes Gate was filled with her family of eight daughters and one surviving son. Throughout her career as a photographer, Hawarden was almost constantly pregnant: she had her first child Isabella Grace in 1846 and her youngest daughter was born in May 1864. Yet very few of her pictures represent a conventional family interior. A stereoscopic image of two of her girls stands out from the collection precisely because of its apparent normality. [Figure 1, V&A PH.457:499-1968] Isabella Grace is seated in a tub chair, and young Clementina is on a low stool. One is reading and the other sewing. They are shown in an unostentatious morning room, with prints above the fireplace. These pictures within pictures hint at the artistic connections of the family. The landscapes are etchings by Seymour Haden, in an advanced Whistlerian manner, but there is also a popular print of cherubs from Raphael’s Sistine Madonna. This photograph places Hawarden firmly within her mid-Victorian context. Her daughters are spending their time in suitable feminine occupations. Yet this ordinariness is undermined by the extraordinary fact that we know their mother is standing behind a camera in the corner of the room. She has chosen to record this moment, in duplicate, to be looked at later in a stereoscopic viewer that will make the whole scene appear in 3-D. The complicated doubling and playing with perception is heightened by the girls’ clothes. They are wearing identical dresses with fine dark stripes on a white background, and contrasting cuffs and hems. The stripes of their dresses are at odds with the ivy patterned upholstery on the chair and the insistent diamonds of the carpet and wallpaper. The girls keep their eye on their work, so we can study them in profile. This interior, which corresponds in many ways to the expectations of orthodox Victorian taste, has been made queer or peculiar by Hawarden’s decision to freeze it on the prepared plate of her camera. She encourages us to study it, to note how the focus shifts from one lens to the other, to dwell on the folds of the matching dresses, and to try to resolve the design of the wallpaper. But this is not an experiment she cares to repeat. The majority of her photographs are taken in bare rooms, set with props and screens, or in the open air in Ireland. A large area of Hawarden’s home was given over to her work. Two interconnected rooms on the first floor became her studio. Judging from the different prints remaining in the V&A Museum and a few other scattered examples, Hawarden worked with at least seven different cameras. These would have been expensive pieces of equipment, cumbersome to set up, and awkward to store. And her supplies of chemicals would also have to be given house-room.

Hawarden left no written record of her processes. We have to look closely at the photographs themselves to find clues to her working practice and her intentions. A portrait of young Clementina with stained fingers, and wearing a dark apron over her dress, demonstrates that making photographs was a messy business. [figure 2, V&A PH.457:319-1968]

It also suggests that at least one of Hawarden’s daughters helped her in preparing and developing the plates. It is likely that the dark room was on the same floor as the studio spaces. There was a large windowless space that connected the two light-filled rooms; this was usually screened off while Hawarden was working. The darkroom would have required a good water supply. When Julia Margaret Cameron developed her prints, she wrote that she needed ‘nine cans of water fresh from the well’ to complete each one.

It also suggests that at least one of Hawarden’s daughters helped her in preparing and developing the plates. It is likely that the dark room was on the same floor as the studio spaces. There was a large windowless space that connected the two light-filled rooms; this was usually screened off while Hawarden was working. The darkroom would have required a good water supply. When Julia Margaret Cameron developed her prints, she wrote that she needed ‘nine cans of water fresh from the well’ to complete each one.  When the family first moved into Princes Gate, the rooms set aside for photography had bare walls. However, towards the end of the 1850s, they were decorated with distinctive patterned wallpaper, which featured as a background to many of Hawarden’s studies. In the photographs, the pattern reads as black stars on a pale background. However, in reality, as Charlotte Gere has pointed out, the paper was printed with deep gold flowers, their pointed petals making them seem star-like. The wall covering was heavy and expensive, and was fixed to batons.

When the family first moved into Princes Gate, the rooms set aside for photography had bare walls. However, towards the end of the 1850s, they were decorated with distinctive patterned wallpaper, which featured as a background to many of Hawarden’s studies. In the photographs, the pattern reads as black stars on a pale background. However, in reality, as Charlotte Gere has pointed out, the paper was printed with deep gold flowers, their pointed petals making them seem star-like. The wall covering was heavy and expensive, and was fixed to batons. Of the two main rooms in which Hawarden took her photographs, one looked out onto the road, and the other faced the garden that was shared by the residents. The back room had sash windows and a shallow balcony, while the front room was fitted with casement windows. The family could step through these windows onto a terrace. The liminal open spaces – attached to the house, yet sunny and semi-public – became important elements in Hawarden’s compositions. Like the painters Berthe Morisot and Mary Cassatt, Hawarden discovered that the balcony and the terrace were rewarding sites for female artistic production.

Hawarden was a woman regularly ‘in confinement’ because of her child-bearing. Yet she found expressive ways of piercing the formal boundaries of her home as her daughters moved delightfully between interior and exterior. The windows, elevated outdoor spaces and even the backdrop of houses across the square all became part of her choreographed landscape of the imagination. She bounced reflections off panes of glass at queer angles. She encouraged shafts of light to make luminous geometry on walls and floor. She moved chairs, girls, dogs and carved wooden owls onto the terrace to form odd interactions. [figure 4, V&A PH. 302-1947] She posed her curved and flounced daughters against the insistent regularity of other people’s houses.

Hawarden was a woman regularly ‘in confinement’ because of her child-bearing. Yet she found expressive ways of piercing the formal boundaries of her home as her daughters moved delightfully between interior and exterior. The windows, elevated outdoor spaces and even the backdrop of houses across the square all became part of her choreographed landscape of the imagination. She bounced reflections off panes of glass at queer angles. She encouraged shafts of light to make luminous geometry on walls and floor. She moved chairs, girls, dogs and carved wooden owls onto the terrace to form odd interactions. [figure 4, V&A PH. 302-1947] She posed her curved and flounced daughters against the insistent regularity of other people’s houses.  In Ireland she had more room to play with. On her husband’s estate at Dundrum, Hawarden photographed farm workers and animals. She set up an outdoor studio against the wall of a workshop to experiment with portrait compositions. She also took a stereoscopic camera into a river valley to photograph a young woman. [figure 5, V&A PH.457:49-1968]

In Ireland she had more room to play with. On her husband’s estate at Dundrum, Hawarden photographed farm workers and animals. She set up an outdoor studio against the wall of a workshop to experiment with portrait compositions. She also took a stereoscopic camera into a river valley to photograph a young woman. [figure 5, V&A PH.457:49-1968]

This figure is dwarfed by the cliffs behind her, with sharp marks of cut stone clearly visible on their surface. The river reflects back fallen rock, rock face, and the thoughtful girl who refuses to read the book in her lap. The whole scene is again doubled by the stereoscopic lenses. Her young model is balanced between confinement and release. She appears trapped between the stones that completely fill the background and the water at her feet. However her gaze, up and out of the image, suggests other means of escape: perhaps by creating an image in her mind’s eye, perhaps by the inspiration of a passage in her book, perhaps even by plunging through the mirrored surface of the water and into the unseen depths. Hawarden created a similar sense of alternative realities, beyond the picture plane, in other photographs taken outdoors in Ireland. Her study of a young woman walking away from us, under a canopy of trees, is one example [figure 6, V&A PH.457-1968:149].

This figure is dwarfed by the cliffs behind her, with sharp marks of cut stone clearly visible on their surface. The river reflects back fallen rock, rock face, and the thoughtful girl who refuses to read the book in her lap. The whole scene is again doubled by the stereoscopic lenses. Her young model is balanced between confinement and release. She appears trapped between the stones that completely fill the background and the water at her feet. However her gaze, up and out of the image, suggests other means of escape: perhaps by creating an image in her mind’s eye, perhaps by the inspiration of a passage in her book, perhaps even by plunging through the mirrored surface of the water and into the unseen depths. Hawarden created a similar sense of alternative realities, beyond the picture plane, in other photographs taken outdoors in Ireland. Her study of a young woman walking away from us, under a canopy of trees, is one example [figure 6, V&A PH.457-1968:149].

The figure is seen from the back. Her skirt is kilted up, in dark folds of fabric, revealing a pale hooped underskirt. This may be practical – to save her dress from the dusty road – but it adds an uneasy element to the scene. It implies exposure, vulnerability. It draws attention to the sway of the woman’s body, and to the delicate play of light and shade throughout the composition. As her feet are hidden in the shadow of her skirts, she almost seems to hover above the surface of the track. She is about to pass away from us, around a corner and into the picture, beyond our reach.

Back in London, Hawarden had less room to manoeuvre. She and her daughters could not roam about with cameras and hitched-up skirts as they did on their private lands in Tipperary. But they did nibble away at the boundaries of convention. Hawarden manipulated the codes of Victorian femininity to her own ends. Often she placed her young women deliberately on the threshold of the public spaces: in one photograph, a gate in the balustrade of the terrace has swung open. [figure 7, V&A PH.457-1968:443]

This barrier between public and private has always, in other images, seemed impermeable. But this picture makes it clear that the girls could step out and down into the communal space of the square. Hawarden photographed her daughter in no-man’s-land, leaning on the ledge of the balustrade, poised between home and the wide world.

This barrier between public and private has always, in other images, seemed impermeable. But this picture makes it clear that the girls could step out and down into the communal space of the square. Hawarden photographed her daughter in no-man’s-land, leaning on the ledge of the balustrade, poised between home and the wide world.  In other compositions, Hawarden played with melodramatic notions of confinement and interiority. She and her girls rigged up elaborate muslin drapes across the windows. Some were plain, others sprigged with ivy-leaves, bringing the outside in. [V&A PH.457: 150-1968 and PH.457: 344-1968]. These semi-transparent swags of material became players in a game of hyper-femininity, as young Clementina grasped, crumpled and twisted them in her out-stretched hands. In one reading of these images, she appears to be protesting against the limitations of the domestic sphere, and the restrictions imposed upon Victorian girls. However, the very fact that she was modelling for her mother, and that they were both complicit in the exaggerated posturing, undermines this interpretation. Both Clementinas, mother and daughter, were collaborating in an undomestic, though private, space. This was no claustrophobic, tight-lipped drawing room scene. These images were created in a light-filled studio. The floors are plain, the boards sometimes left bare, and sometimes covered with rush matting. There are scraps of paper left lying about. Objects are out of place. This was a utilitarian space, with none of the upholstery and carpeting seen in the morning-room stereoscopic photograph. Hawarden’s women are inside a Victorian home, but it is unheimlich.

In other compositions, Hawarden played with melodramatic notions of confinement and interiority. She and her girls rigged up elaborate muslin drapes across the windows. Some were plain, others sprigged with ivy-leaves, bringing the outside in. [V&A PH.457: 150-1968 and PH.457: 344-1968]. These semi-transparent swags of material became players in a game of hyper-femininity, as young Clementina grasped, crumpled and twisted them in her out-stretched hands. In one reading of these images, she appears to be protesting against the limitations of the domestic sphere, and the restrictions imposed upon Victorian girls. However, the very fact that she was modelling for her mother, and that they were both complicit in the exaggerated posturing, undermines this interpretation. Both Clementinas, mother and daughter, were collaborating in an undomestic, though private, space. This was no claustrophobic, tight-lipped drawing room scene. These images were created in a light-filled studio. The floors are plain, the boards sometimes left bare, and sometimes covered with rush matting. There are scraps of paper left lying about. Objects are out of place. This was a utilitarian space, with none of the upholstery and carpeting seen in the morning-room stereoscopic photograph. Hawarden’s women are inside a Victorian home, but it is unheimlich.

Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida, p.93 Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida, p.92 See Virginia Dodier, Clementina, Lady Hawarden: Studies from Life 1857-64, V&A Publications, London, 1999 p.120 for a floor plan of Princes Gardens Julia Margaret Cameron, quoted by Colin Ford, Julia Margaret Cameron: 19thCentury Photographer of Genius, National Portrait Gallery, London, 2003, p.39 I am grateful to Charlotte Gere for pointing this out during our discussions at The Gendered Interior in Nineteenth-Century Art symposium on 20 November 2013.

Published on March 02, 2018 08:06

January 16, 2018

Ravilious & Co. I've been thinking about Eric Ravilio...

Ravilious & Co.

I've been thinking about Eric Ravilious for a long time now - ever since we lived in Lewes, and could see the chalk paths across the Downs that he loved to draw. The exceptional exhibition, 'Ravilious & Co', which has just left Sheffield and will be reassembled at Compton Verney on March 17th 2018, is a reminder of the beauty and seriousness of his paintings. It is a testament to the research and persistence of Andy Friend and James Russell. And it demonstrates the astonishing vitality of Ravilious's artistic circle - the women and men who trained and worked alongside him. It seems a good time to try to pin down the reasons why I find his pictures so engrossing and a continual source of visual pleasure.

Sussex, Summer 1939:

A tea-table stands in the corner of the garden. The milk-jug and plate of butter are shaded by a battered umbrella. The warm air smells of fresh bread and new hay. Peggy Angus is expecting visitors. She leans on the wall, her cotton dress flapping against her bare brown legs, humming snatches of old tunes. At the end of the track she sees them, dark figures against a chalk-white ground, a man and a woman carrying knapsacks and painting gear. Eric Ravilious and his love Helen Binyon walk up the long lane from Glynde Station. Refugees from the clatter of London, for a few days they can shelter beneath the open skies and lark-song.

A tea-table stands in the corner of the garden. The milk-jug and plate of butter are shaded by a battered umbrella. The warm air smells of fresh bread and new hay. Peggy Angus is expecting visitors. She leans on the wall, her cotton dress flapping against her bare brown legs, humming snatches of old tunes. At the end of the track she sees them, dark figures against a chalk-white ground, a man and a woman carrying knapsacks and painting gear. Eric Ravilious and his love Helen Binyon walk up the long lane from Glynde Station. Refugees from the clatter of London, for a few days they can shelter beneath the open skies and lark-song.

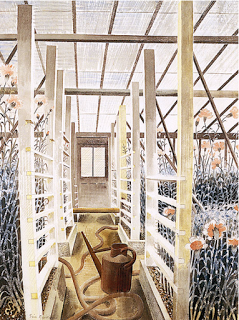

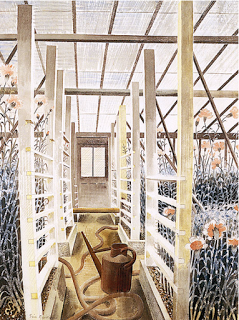

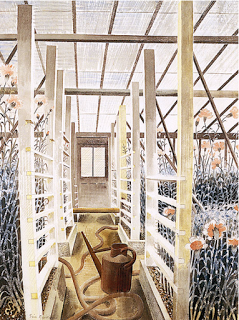

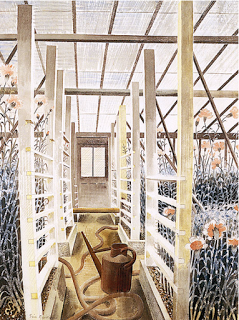

Peggy’s cottage, Furlongs, sits beneath the swelling Sussex Downs. It is a place of retreat for her artist-friends, a survivor from quieter times. While Britain prepares for war, a procession of shire-horses and wagons pass her gate, and her front door stands open to the breeze and sunshine. Her fellow-students from the old days at the Royal College of Art make their pilgrimages here. In her small sitting room, beneath a ruby-glass oil lamp, the artists gather: Eric and Helen, Edward and Charlotte Bawden, John and Myfanwy Piper. They share a desire to catalogue the small wonders of the English landscape. Knowing that their world is under threat, the need to paint becomes more urgent. They are the inheritors of the visionary Romantic tradition, heirs to Samuel Palmer. Yet their art is sharp and never sentimental. It is underpinned by a radicalism drawn from the utopias of William Morris. Ravilious makes it his mission to document the ebb and flow of the Downland and its mysterious carved figures, white horses and giants. His incisive eye, his delight in domesticity, his nostalgia and quirkiness suggest parallels with John Betjeman. The lyricism of his watercolours reminds us of Vaughan Williams. Throughout the 1930s Ravilious fashions calm memorials to Englishness: images of white cliffs, greenhouses hung with ripening tomatoes, and ancient paths climbing to the sunlit uplands.

Ravilious makes it his mission to document the ebb and flow of the Downland and its mysterious carved figures, white horses and giants. His incisive eye, his delight in domesticity, his nostalgia and quirkiness suggest parallels with John Betjeman. The lyricism of his watercolours reminds us of Vaughan Williams. Throughout the 1930s Ravilious fashions calm memorials to Englishness: images of white cliffs, greenhouses hung with ripening tomatoes, and ancient paths climbing to the sunlit uplands.

And then the war breaks in. Ravilious, Piper and Bawden join Kenneth Clark’s band of official war artists. Bawden is posted to North Africa and turns his hand to painting the vast theatres of war in Libya, Iraq and Ethiopia. Piper sits with his sketchbook in the smouldering relics of Coventry Cathedral. And Ravilious is offered a commission in the Admiralty. He records coastal defences, submarines and docks around the South Coast and in Norway. Then in the summer of 1942 he is sent to Iceland. On 2nd September his plane disappears over the sea, and he is lost.

**********************************************************************************

By tracing the patterns of friendship between Ravilious, Bawden and their circle, the exhibition offers an alternative history of English art. Furlongs was barely five miles from Charleston, Virginia Woolf’s Sussex home. Like Charleston, Furlongs provided the backdrop to love-affairs and intrigues. But the artistic atmosphere of the two meeting-places could hardly have been more different. The Bloomsbury group were self-consciously modernist. The folk at Furlongs, on the other hand, embraced the traditions of English watercolour painting and wood-engraving. Their work was intimate and evocative.

By tracing the patterns of friendship between Ravilious, Bawden and their circle, the exhibition offers an alternative history of English art. Furlongs was barely five miles from Charleston, Virginia Woolf’s Sussex home. Like Charleston, Furlongs provided the backdrop to love-affairs and intrigues. But the artistic atmosphere of the two meeting-places could hardly have been more different. The Bloomsbury group were self-consciously modernist. The folk at Furlongs, on the other hand, embraced the traditions of English watercolour painting and wood-engraving. Their work was intimate and evocative.

Ravilious traced the curl of a Swiss-roll with as much care as he mapped the course of a river. He and his friends loved trips to the seaside, DIY and bunting, Bonfire Night and evenings in the pub. Benjamin Britten and Henry Moore crossed their path, but this group of artists chose not to follow their lead. Instead they painted ordinary beauty, glimpsed from a train window. Their visions of Englishness have become more poignant as the years have passed. We now celebrate their legacy in exhibitions, calendars, notecards and fridge magnets. ******************************************************************************

Our first sight of Eric Ravilious is likely to be low key and domestic. He slips quietly into our lives, with his black-and-white designs for the breakfast table. We follow the undulating dot-and-dash around the rim of a bowl. Then we start to feel our way into one of his landscapes, pushing through a wire fence, up a path, over the Downs. Next, we become entangled in a coil of rope washed up in a watercolour. Before we have quite realised what is happening, we are smitten. Ravilious has cast his spell.

Ravilious’s ability to enchant was recognised by his early friends and critics. Fellow-students at the Royal College of Art called him ‘the Boy’. In 1939, his pictures were described as ‘something magic, almost mystic, distilled out of the ordinary’. The taut geometry of his paintings lifts mundane objects, insisting that we take them seriously. A battered bicycle, a loaf of bread, a pot of geraniums, each thing becomes delightful under his touch. And then disconcerting as we acknowledge its peculiarities. He makes us see the curves and edges, the relationship to other things placed beside it. As we look more closely, we notice that Ravilious’s watercolours never try to conceal the skeleton of his drawing beneath the bright washes of blue and yellow and orangey-red.

With a ruler and a pencil he draws a web of lines. They might become ceiling joists or floorboards, a quayside, a runway or young crops in a field. But they are never exactly aligned with our idea of perspective. His rooms are slightly aslant, his table-tops are tilted. He keeps us on our toes, a little anxious that the image could slide away from us or trip us up.

This is one of his magic tricks. Ravilious offers us pictures that at first sight seem straightforward; as he said when he drew the folds of the Sussex Downs, ‘the design was so beautifully obvious’. He holds our attention by making the familiar look fresh. He watches from new vantage points. He makes us question the choreography of his compositions. How could he paint that bedroom, unless he was standing on a chair in one corner? Why did he outline those scissors and spoons on a tray, laid out like a game of Pelmanism?

This tendency becomes more marked from 1940 when he begins his War work. Ravilious’s paintings and lithographs lead us into empty huts, then down into tunnels hung with maps and out onto icy seas. His eye dwells on the uneasy interludes that punctuate conflict. He shows the steady administrative tasks – telephone calls, filing cabinets, test flights – underpinning the drama of war. Occasionally he treats us to a burst of artillery, blazing from a 9.2 gun positioned high above the coast. But even here he suggests that the soldiers are simply getting on with their job. There is no hurry. We do not know what they are firing at, or whether they hit it. The yellow flash from the gun’s mouth is hardly a sign of modern warfare. Instead it seems like a nod to an earlier tradition of fireworks (which Ravilious loved) or William Blake’s flaming flowers in Songs of Innocence and Experience.

This tendency becomes more marked from 1940 when he begins his War work. Ravilious’s paintings and lithographs lead us into empty huts, then down into tunnels hung with maps and out onto icy seas. His eye dwells on the uneasy interludes that punctuate conflict. He shows the steady administrative tasks – telephone calls, filing cabinets, test flights – underpinning the drama of war. Occasionally he treats us to a burst of artillery, blazing from a 9.2 gun positioned high above the coast. But even here he suggests that the soldiers are simply getting on with their job. There is no hurry. We do not know what they are firing at, or whether they hit it. The yellow flash from the gun’s mouth is hardly a sign of modern warfare. Instead it seems like a nod to an earlier tradition of fireworks (which Ravilious loved) or William Blake’s flaming flowers in Songs of Innocence and Experience.

In 1941, the same year that Ravilious painted his bright gun, an appreciation of Blake was published by David Cecil in The English Poets. According to Cecil, Blake’s poems were like ‘a rush of the wind in the tree-tops’ or ‘a fresh gale, racy with the smell of earth’.Ravilious responded in kind. His gun-emplacement is set on a breezy upland. Wind-tossed flowers draw our eye away from the figures, and across waving grasses towards the sea. What are the artillery-men defending? This was the central question for the artists gathered by Kenneth Clark late in 1939 to document the war. It was not simply the ‘green and pleasant land’ that produced Blake. It was the right for a man to sit in a field with his sketchbook, despite the gunfire, in the ‘rush of the wind’. England now meant both Blake and gun-batteries. They co-existed in Ravilious’s watercolour, the pastoral interrupted by a blast.

Clark oversaw a thoughtful and energetic project, encouraging modern painters to respond to the new face of combat. This was no exercise in nostalgia. And Clark did not keep his artists out of harm’s way. In Ravilious’s case, with his work for the Admiralty, his subject was the fragile edges of Britain. He painted a coastline defined by new concrete defences and curls of barbed wire, with the pleasure boats drawn up high onto the beach to sit out the war. There is the recurring motif of the lighthouse marking the intersections between land, sea and sky. Ravilious was particularly fond of the stumpy towers at Newhaven, as well as the elegant tension between curved and flat in the lighthouse at Rye. Sometimes in his paintings they shine into the darkness. More often, though, they are unlit, upright and waiting. Very occasionally, as in Belle Tout interior (1939), Ravilious shows us the view from inside the lantern, the sunlight streaming in through the window panes, almost too bright to look at. A calligraphic line dancing across the paper marks the boundary between land and sea.

Ravilious delighted in rippling borderlines. We find them at the scalloped edges of sandbanks as they dip beneath the waters of Rye Harbour (1938).

They mark the gap between grass and tarmac in Runway Perspective (1942).

And most spectacularly, Ravilious created a sparkling thread of water flowing through marshland in Cuckmere Haven (1939). Here the meander of the river is echoed in the ribbon of a chalk path through the grass, and even in the cloud formations. Earth, water, sky are linked and defined by the looping lines of Ravilious’s pencil.

And most spectacularly, Ravilious created a sparkling thread of water flowing through marshland in Cuckmere Haven (1939). Here the meander of the river is echoed in the ribbon of a chalk path through the grass, and even in the cloud formations. Earth, water, sky are linked and defined by the looping lines of Ravilious’s pencil.

However, he is careful not to let us become lost in a watery maze. A stone wall and a field in the foreground create a gently sloping springboard. From here the acrobatic elements in the composition can rise, soar, twist and come to rest again. In every watercolour there is an underpinning, an architecture which is laid down first. It is rarely quite on the square, and this contributes to the tension between solid and line. But nevertheless, Ravilious mapped the geology of his landscapes and the girders of his underground corridors in pencil, before he explored their more delicate edges and crossing points.

This exhibition allows us to follow the threads back to his early years as an art student, and forward towards his work in Norway and Iceland. It reveals the strands that link him to the avant-garde of the 1920s and his place in a wider circle of artists who wrote and thought and travelled in interwar Britain. It also asks us to consider how the loss of his aircraft in 1942, missing (presumed dead) before his 40th birthday, altered the reception of his art. Above all, these displays allow us to linger, to delight in the complex surfaces of the watercolours, and the enjoy the intricacies of his black and white designs.

Jan Gordon, ‘Influences and Fusion’, The Observer, 14 May 1939, p.14

Eric Ravilious, letter to Peggy Angus, 15 May 1939, in James Russell, Ravilious, exhibition catalogue, Dulwich Picture Gallery, Philip Wilson Publishers, 2015, p.10

Eric Ravilious, Firing a 9.2 Gun, 1941, watercolour on paper, Imperial War Museum

David Cecil, English Poets, from Britain in Pictures series, London, 1941, pp. 9 & 20

I've been thinking about Eric Ravilious for a long time now - ever since we lived in Lewes, and could see the chalk paths across the Downs that he loved to draw. The exceptional exhibition, 'Ravilious & Co', which has just left Sheffield and will be reassembled at Compton Verney on March 17th 2018, is a reminder of the beauty and seriousness of his paintings. It is a testament to the research and persistence of Andy Friend and James Russell. And it demonstrates the astonishing vitality of Ravilious's artistic circle - the women and men who trained and worked alongside him. It seems a good time to try to pin down the reasons why I find his pictures so engrossing and a continual source of visual pleasure.

Sussex, Summer 1939:

A tea-table stands in the corner of the garden. The milk-jug and plate of butter are shaded by a battered umbrella. The warm air smells of fresh bread and new hay. Peggy Angus is expecting visitors. She leans on the wall, her cotton dress flapping against her bare brown legs, humming snatches of old tunes. At the end of the track she sees them, dark figures against a chalk-white ground, a man and a woman carrying knapsacks and painting gear. Eric Ravilious and his love Helen Binyon walk up the long lane from Glynde Station. Refugees from the clatter of London, for a few days they can shelter beneath the open skies and lark-song.

A tea-table stands in the corner of the garden. The milk-jug and plate of butter are shaded by a battered umbrella. The warm air smells of fresh bread and new hay. Peggy Angus is expecting visitors. She leans on the wall, her cotton dress flapping against her bare brown legs, humming snatches of old tunes. At the end of the track she sees them, dark figures against a chalk-white ground, a man and a woman carrying knapsacks and painting gear. Eric Ravilious and his love Helen Binyon walk up the long lane from Glynde Station. Refugees from the clatter of London, for a few days they can shelter beneath the open skies and lark-song. Peggy’s cottage, Furlongs, sits beneath the swelling Sussex Downs. It is a place of retreat for her artist-friends, a survivor from quieter times. While Britain prepares for war, a procession of shire-horses and wagons pass her gate, and her front door stands open to the breeze and sunshine. Her fellow-students from the old days at the Royal College of Art make their pilgrimages here. In her small sitting room, beneath a ruby-glass oil lamp, the artists gather: Eric and Helen, Edward and Charlotte Bawden, John and Myfanwy Piper. They share a desire to catalogue the small wonders of the English landscape. Knowing that their world is under threat, the need to paint becomes more urgent. They are the inheritors of the visionary Romantic tradition, heirs to Samuel Palmer. Yet their art is sharp and never sentimental. It is underpinned by a radicalism drawn from the utopias of William Morris.

Ravilious makes it his mission to document the ebb and flow of the Downland and its mysterious carved figures, white horses and giants. His incisive eye, his delight in domesticity, his nostalgia and quirkiness suggest parallels with John Betjeman. The lyricism of his watercolours reminds us of Vaughan Williams. Throughout the 1930s Ravilious fashions calm memorials to Englishness: images of white cliffs, greenhouses hung with ripening tomatoes, and ancient paths climbing to the sunlit uplands.

Ravilious makes it his mission to document the ebb and flow of the Downland and its mysterious carved figures, white horses and giants. His incisive eye, his delight in domesticity, his nostalgia and quirkiness suggest parallels with John Betjeman. The lyricism of his watercolours reminds us of Vaughan Williams. Throughout the 1930s Ravilious fashions calm memorials to Englishness: images of white cliffs, greenhouses hung with ripening tomatoes, and ancient paths climbing to the sunlit uplands.And then the war breaks in. Ravilious, Piper and Bawden join Kenneth Clark’s band of official war artists. Bawden is posted to North Africa and turns his hand to painting the vast theatres of war in Libya, Iraq and Ethiopia. Piper sits with his sketchbook in the smouldering relics of Coventry Cathedral. And Ravilious is offered a commission in the Admiralty. He records coastal defences, submarines and docks around the South Coast and in Norway. Then in the summer of 1942 he is sent to Iceland. On 2nd September his plane disappears over the sea, and he is lost.

**********************************************************************************

By tracing the patterns of friendship between Ravilious, Bawden and their circle, the exhibition offers an alternative history of English art. Furlongs was barely five miles from Charleston, Virginia Woolf’s Sussex home. Like Charleston, Furlongs provided the backdrop to love-affairs and intrigues. But the artistic atmosphere of the two meeting-places could hardly have been more different. The Bloomsbury group were self-consciously modernist. The folk at Furlongs, on the other hand, embraced the traditions of English watercolour painting and wood-engraving. Their work was intimate and evocative.

By tracing the patterns of friendship between Ravilious, Bawden and their circle, the exhibition offers an alternative history of English art. Furlongs was barely five miles from Charleston, Virginia Woolf’s Sussex home. Like Charleston, Furlongs provided the backdrop to love-affairs and intrigues. But the artistic atmosphere of the two meeting-places could hardly have been more different. The Bloomsbury group were self-consciously modernist. The folk at Furlongs, on the other hand, embraced the traditions of English watercolour painting and wood-engraving. Their work was intimate and evocative. Ravilious traced the curl of a Swiss-roll with as much care as he mapped the course of a river. He and his friends loved trips to the seaside, DIY and bunting, Bonfire Night and evenings in the pub. Benjamin Britten and Henry Moore crossed their path, but this group of artists chose not to follow their lead. Instead they painted ordinary beauty, glimpsed from a train window. Their visions of Englishness have become more poignant as the years have passed. We now celebrate their legacy in exhibitions, calendars, notecards and fridge magnets. ******************************************************************************

Our first sight of Eric Ravilious is likely to be low key and domestic. He slips quietly into our lives, with his black-and-white designs for the breakfast table. We follow the undulating dot-and-dash around the rim of a bowl. Then we start to feel our way into one of his landscapes, pushing through a wire fence, up a path, over the Downs. Next, we become entangled in a coil of rope washed up in a watercolour. Before we have quite realised what is happening, we are smitten. Ravilious has cast his spell.

Ravilious’s ability to enchant was recognised by his early friends and critics. Fellow-students at the Royal College of Art called him ‘the Boy’. In 1939, his pictures were described as ‘something magic, almost mystic, distilled out of the ordinary’. The taut geometry of his paintings lifts mundane objects, insisting that we take them seriously. A battered bicycle, a loaf of bread, a pot of geraniums, each thing becomes delightful under his touch. And then disconcerting as we acknowledge its peculiarities. He makes us see the curves and edges, the relationship to other things placed beside it. As we look more closely, we notice that Ravilious’s watercolours never try to conceal the skeleton of his drawing beneath the bright washes of blue and yellow and orangey-red.

With a ruler and a pencil he draws a web of lines. They might become ceiling joists or floorboards, a quayside, a runway or young crops in a field. But they are never exactly aligned with our idea of perspective. His rooms are slightly aslant, his table-tops are tilted. He keeps us on our toes, a little anxious that the image could slide away from us or trip us up.

This is one of his magic tricks. Ravilious offers us pictures that at first sight seem straightforward; as he said when he drew the folds of the Sussex Downs, ‘the design was so beautifully obvious’. He holds our attention by making the familiar look fresh. He watches from new vantage points. He makes us question the choreography of his compositions. How could he paint that bedroom, unless he was standing on a chair in one corner? Why did he outline those scissors and spoons on a tray, laid out like a game of Pelmanism?

This tendency becomes more marked from 1940 when he begins his War work. Ravilious’s paintings and lithographs lead us into empty huts, then down into tunnels hung with maps and out onto icy seas. His eye dwells on the uneasy interludes that punctuate conflict. He shows the steady administrative tasks – telephone calls, filing cabinets, test flights – underpinning the drama of war. Occasionally he treats us to a burst of artillery, blazing from a 9.2 gun positioned high above the coast. But even here he suggests that the soldiers are simply getting on with their job. There is no hurry. We do not know what they are firing at, or whether they hit it. The yellow flash from the gun’s mouth is hardly a sign of modern warfare. Instead it seems like a nod to an earlier tradition of fireworks (which Ravilious loved) or William Blake’s flaming flowers in Songs of Innocence and Experience.

This tendency becomes more marked from 1940 when he begins his War work. Ravilious’s paintings and lithographs lead us into empty huts, then down into tunnels hung with maps and out onto icy seas. His eye dwells on the uneasy interludes that punctuate conflict. He shows the steady administrative tasks – telephone calls, filing cabinets, test flights – underpinning the drama of war. Occasionally he treats us to a burst of artillery, blazing from a 9.2 gun positioned high above the coast. But even here he suggests that the soldiers are simply getting on with their job. There is no hurry. We do not know what they are firing at, or whether they hit it. The yellow flash from the gun’s mouth is hardly a sign of modern warfare. Instead it seems like a nod to an earlier tradition of fireworks (which Ravilious loved) or William Blake’s flaming flowers in Songs of Innocence and Experience.

In 1941, the same year that Ravilious painted his bright gun, an appreciation of Blake was published by David Cecil in The English Poets. According to Cecil, Blake’s poems were like ‘a rush of the wind in the tree-tops’ or ‘a fresh gale, racy with the smell of earth’.Ravilious responded in kind. His gun-emplacement is set on a breezy upland. Wind-tossed flowers draw our eye away from the figures, and across waving grasses towards the sea. What are the artillery-men defending? This was the central question for the artists gathered by Kenneth Clark late in 1939 to document the war. It was not simply the ‘green and pleasant land’ that produced Blake. It was the right for a man to sit in a field with his sketchbook, despite the gunfire, in the ‘rush of the wind’. England now meant both Blake and gun-batteries. They co-existed in Ravilious’s watercolour, the pastoral interrupted by a blast.

Clark oversaw a thoughtful and energetic project, encouraging modern painters to respond to the new face of combat. This was no exercise in nostalgia. And Clark did not keep his artists out of harm’s way. In Ravilious’s case, with his work for the Admiralty, his subject was the fragile edges of Britain. He painted a coastline defined by new concrete defences and curls of barbed wire, with the pleasure boats drawn up high onto the beach to sit out the war. There is the recurring motif of the lighthouse marking the intersections between land, sea and sky. Ravilious was particularly fond of the stumpy towers at Newhaven, as well as the elegant tension between curved and flat in the lighthouse at Rye. Sometimes in his paintings they shine into the darkness. More often, though, they are unlit, upright and waiting. Very occasionally, as in Belle Tout interior (1939), Ravilious shows us the view from inside the lantern, the sunlight streaming in through the window panes, almost too bright to look at. A calligraphic line dancing across the paper marks the boundary between land and sea.

Ravilious delighted in rippling borderlines. We find them at the scalloped edges of sandbanks as they dip beneath the waters of Rye Harbour (1938).

They mark the gap between grass and tarmac in Runway Perspective (1942).

And most spectacularly, Ravilious created a sparkling thread of water flowing through marshland in Cuckmere Haven (1939). Here the meander of the river is echoed in the ribbon of a chalk path through the grass, and even in the cloud formations. Earth, water, sky are linked and defined by the looping lines of Ravilious’s pencil.

And most spectacularly, Ravilious created a sparkling thread of water flowing through marshland in Cuckmere Haven (1939). Here the meander of the river is echoed in the ribbon of a chalk path through the grass, and even in the cloud formations. Earth, water, sky are linked and defined by the looping lines of Ravilious’s pencil. However, he is careful not to let us become lost in a watery maze. A stone wall and a field in the foreground create a gently sloping springboard. From here the acrobatic elements in the composition can rise, soar, twist and come to rest again. In every watercolour there is an underpinning, an architecture which is laid down first. It is rarely quite on the square, and this contributes to the tension between solid and line. But nevertheless, Ravilious mapped the geology of his landscapes and the girders of his underground corridors in pencil, before he explored their more delicate edges and crossing points.

This exhibition allows us to follow the threads back to his early years as an art student, and forward towards his work in Norway and Iceland. It reveals the strands that link him to the avant-garde of the 1920s and his place in a wider circle of artists who wrote and thought and travelled in interwar Britain. It also asks us to consider how the loss of his aircraft in 1942, missing (presumed dead) before his 40th birthday, altered the reception of his art. Above all, these displays allow us to linger, to delight in the complex surfaces of the watercolours, and the enjoy the intricacies of his black and white designs.

Jan Gordon, ‘Influences and Fusion’, The Observer, 14 May 1939, p.14

Eric Ravilious, letter to Peggy Angus, 15 May 1939, in James Russell, Ravilious, exhibition catalogue, Dulwich Picture Gallery, Philip Wilson Publishers, 2015, p.10

Eric Ravilious, Firing a 9.2 Gun, 1941, watercolour on paper, Imperial War Museum

David Cecil, English Poets, from Britain in Pictures series, London, 1941, pp. 9 & 20

Published on January 16, 2018 13:48

Ravilious & Co. I've been thinking about Eric Ra...

Ravilious & Co.

I've been thinking about Eric Ravilious for a long time now - ever since we lived in Lewes, and could see the chalk paths across the Downs that he loved to draw. The exceptional exhibition, 'Ravilious & Co', which has just left Sheffield and will be reassembled at Compton Verney on March 17th 2018, is a reminder of the beauty and seriousness of his paintings. It is a testament to the research and persistence of Andy Friend and James Russell. And it demonstrates the astonishing vitality of Ravilious's artistic circle - the women and men who trained and worked alongside him. It seems a good time to try to pin down the reasons why I find his pictures so engrossing and a continual source of visual pleasure.

Sussex, Summer 1939:

A tea-table stands in the corner of the garden. The milk-jug and plate of butter are shaded by a battered umbrella. The warm air smells of fresh bread and new hay. Peggy Angus is expecting visitors. She leans on the wall, her cotton dress flapping against her bare brown legs, humming snatches of old tunes. At the end of the track she sees them, dark figures against a chalk-white ground, a man and a woman carrying knapsacks and painting gear. Eric Ravilious and his love Helen Binyon walk up the long lane from Glynde Station. Refugees from the clatter of London, for a few days they can shelter beneath the open skies and lark-song.

A tea-table stands in the corner of the garden. The milk-jug and plate of butter are shaded by a battered umbrella. The warm air smells of fresh bread and new hay. Peggy Angus is expecting visitors. She leans on the wall, her cotton dress flapping against her bare brown legs, humming snatches of old tunes. At the end of the track she sees them, dark figures against a chalk-white ground, a man and a woman carrying knapsacks and painting gear. Eric Ravilious and his love Helen Binyon walk up the long lane from Glynde Station. Refugees from the clatter of London, for a few days they can shelter beneath the open skies and lark-song.

Peggy’s cottage, Furlongs, sits beneath the swelling Sussex Downs. It is a place of retreat for her artist-friends, a survivor from quieter times. While Britain prepares for war, a procession of shire-horses and wagons pass her gate, and her front door stands open to the breeze and sunshine. Her fellow-students from the old days at the Royal College of Art make their pilgrimages here. In her small sitting room, beneath a ruby-glass oil lamp, the artists gather: Eric and Helen, Edward and Charlotte Bawden, John and Myfanwy Piper. They share a desire to catalogue the small wonders of the English landscape. Knowing that their world is under threat, the need to paint becomes more urgent. They are the inheritors of the visionary Romantic tradition, heirs to Samuel Palmer. Yet their art is sharp and never sentimental. It is underpinned by a radicalism drawn from the utopias of William Morris. Ravilious makes it his mission to document the ebb and flow of the Downland and its mysterious carved figures, white horses and giants. His incisive eye, his delight in domesticity, his nostalgia and quirkiness suggest parallels with John Betjeman. The lyricism of his watercolours reminds us of Vaughan Williams. Throughout the 1930s Ravilious fashions calm memorials to Englishness: images of white cliffs, greenhouses hung with ripening tomatoes, and ancient paths climbing to the sunlit uplands.

Ravilious makes it his mission to document the ebb and flow of the Downland and its mysterious carved figures, white horses and giants. His incisive eye, his delight in domesticity, his nostalgia and quirkiness suggest parallels with John Betjeman. The lyricism of his watercolours reminds us of Vaughan Williams. Throughout the 1930s Ravilious fashions calm memorials to Englishness: images of white cliffs, greenhouses hung with ripening tomatoes, and ancient paths climbing to the sunlit uplands.

And then the war breaks in. Ravilious, Piper and Bawden join Kenneth Clark’s band of official war artists. Bawden is posted to North Africa and turns his hand to painting the vast theatres of war in Libya, Iraq and Ethiopia. Piper sits with his sketchbook in the smouldering relics of Coventry Cathedral. And Ravilious is offered a commission in the Admiralty. He records coastal defences, submarines and docks around the South Coast and in Norway. Then in the summer of 1942 he is sent to Iceland. On 2nd September his plane disappears over the sea, and he is lost.

**********************************************************************************

By tracing the patterns of friendship between Ravilious, Bawden and their circle, the exhibition offers an alternative history of English art. Furlongs was barely five miles from Charleston, Virginia Woolf’s Sussex home. Like Charleston, Furlongs provided the backdrop to love-affairs and intrigues. But the artistic atmosphere of the two meeting-places could hardly have been more different. The Bloomsbury group were self-consciously modernist. The folk at Furlongs, on the other hand, embraced the traditions of English watercolour painting and wood-engraving. Their work was intimate and evocative.

By tracing the patterns of friendship between Ravilious, Bawden and their circle, the exhibition offers an alternative history of English art. Furlongs was barely five miles from Charleston, Virginia Woolf’s Sussex home. Like Charleston, Furlongs provided the backdrop to love-affairs and intrigues. But the artistic atmosphere of the two meeting-places could hardly have been more different. The Bloomsbury group were self-consciously modernist. The folk at Furlongs, on the other hand, embraced the traditions of English watercolour painting and wood-engraving. Their work was intimate and evocative.

Ravilious traced the curl of a Swiss-roll with as much care as he mapped the course of a river. He and his friends loved trips to the seaside, DIY and bunting, Bonfire Night and evenings in the pub. Benjamin Britten and Henry Moore crossed their path, but this group of artists chose not to follow their lead. Instead they painted ordinary beauty, glimpsed from a train window. Their visions of Englishness have become more poignant as the years have passed. We now celebrate their legacy in exhibitions, calendars, notecards and fridge magnets. ******************************************************************************

Our first sight of Eric Ravilious is likely to be low key and domestic. He slips quietly into our lives, with his black-and-white designs for the breakfast table. We follow the undulating dot-and-dash around the rim of a bowl. Then we start to feel our way into one of his landscapes, pushing through a wire fence, up a path, over the Downs. Next, we become entangled in a coil of rope washed up in a watercolour. Before we have quite realised what is happening, we are smitten. Ravilious has cast his spell.

Ravilious’s ability to enchant was recognised by his early friends and critics. Fellow-students at the Royal College of Art called him ‘the Boy’. In 1939, his pictures were described as ‘something magic, almost mystic, distilled out of the ordinary’.

With a ruler and a pencil he draws a web of lines. They might become ceiling joists or floorboards, a quayside, a runway or young crops in a field. But they are never exactly aligned with our idea of perspective. His rooms are slightly aslant, his table-tops are tilted. He keeps us on our toes, a little anxious that the image could slide away from us or trip us up.

This is one of his magic tricks. Ravilious offers us pictures that at first sight seem straightforward; as he said when he drew the folds of the Sussex Downs, ‘the design was so beautifully obvious’. This tendency becomes more marked from 1940 when he begins his War work. Ravilious’s paintings and lithographs lead us into empty huts, then down into tunnels hung with maps and out onto icy seas. His eye dwells on the uneasy interludes that punctuate conflict. He shows the steady administrative tasks – telephone calls, filing cabinets, test flights – underpinning the drama of war. Occasionally he treats us to a burst of artillery, blazing from a 9.2 gun positioned high above the coast.

This tendency becomes more marked from 1940 when he begins his War work. Ravilious’s paintings and lithographs lead us into empty huts, then down into tunnels hung with maps and out onto icy seas. His eye dwells on the uneasy interludes that punctuate conflict. He shows the steady administrative tasks – telephone calls, filing cabinets, test flights – underpinning the drama of war. Occasionally he treats us to a burst of artillery, blazing from a 9.2 gun positioned high above the coast.

In 1941, the same year that Ravilious painted his bright gun, an appreciation of Blake was published by David Cecil in The English Poets. According to Cecil, Blake’s poems were like ‘a rush of the wind in the tree-tops’ or ‘a fresh gale, racy with the smell of earth’.

Clark oversaw a thoughtful and energetic project, encouraging modern painters to respond to the new face of combat. This was no exercise in nostalgia. And Clark did not keep his artists out of harm’s way. In Ravilious’s case, with his work for the Admiralty, his subject was the fragile edges of Britain. He painted a coastline defined by new concrete defences and curls of barbed wire, with the pleasure boats drawn up high onto the beach to sit out the war. There is the recurring motif of the lighthouse marking the intersections between land, sea and sky. Ravilious was particularly fond of the stumpy towers at Newhaven, as well as the elegant tension between curved and flat in the lighthouse at Rye. Sometimes in his paintings they shine into the darkness. More often, though, they are unlit, upright and waiting. Very occasionally, as in Belle Tout interior (1939), Ravilious shows us the view from inside the lantern, the sunlight streaming in through the window panes, almost too bright to look at. A calligraphic line dancing across the paper marks the boundary between land and sea.

Ravilious delighted in rippling borderlines. We find them at the scalloped edges of sandbanks as they dip beneath the waters of Rye Harbour (1938).

They mark the gap between grass and tarmac in Runway Perspective (1942).

And most spectacularly, Ravilious created a sparkling thread of water flowing through marshland in Cuckmere Haven (1939). Here the meander of the river is echoed in the ribbon of a chalk path through the grass, and even in the cloud formations. Earth, water, sky are linked and defined by the looping lines of Ravilious’s pencil.

And most spectacularly, Ravilious created a sparkling thread of water flowing through marshland in Cuckmere Haven (1939). Here the meander of the river is echoed in the ribbon of a chalk path through the grass, and even in the cloud formations. Earth, water, sky are linked and defined by the looping lines of Ravilious’s pencil.

However, he is careful not to let us become lost in a watery maze. A stone wall and a field in the foreground create a gently sloping springboard. From here the acrobatic elements in the composition can rise, soar, twist and come to rest again. In every watercolour there is an underpinning, an architecture which is laid down first. It is rarely quite on the square, and this contributes to the tension between solid and line. But nevertheless, Ravilious mapped the geology of his landscapes and the girders of his underground corridors in pencil, before he explored their more delicate edges and crossing points.

This exhibition allows us to follow the threads back to his early years as an art student, and forward towards his work in Norway and Iceland. It reveals the strands that link him to the avant-garde of the 1920s and his place in a wider circle of artists who wrote and thought and travelled in interwar Britain. It also asks us to consider how the loss of his aircraft in 1942, missing (presumed dead) before his 40th birthday, altered the reception of his art. Above all, these displays allow us to linger, to delight in the complex surfaces of the watercolours, and the enjoy the intricacies of his black and white designs.

David Cecil, English Poets, from Britain in Pictures series, London, 1941, pp. 9 & 20

I've been thinking about Eric Ravilious for a long time now - ever since we lived in Lewes, and could see the chalk paths across the Downs that he loved to draw. The exceptional exhibition, 'Ravilious & Co', which has just left Sheffield and will be reassembled at Compton Verney on March 17th 2018, is a reminder of the beauty and seriousness of his paintings. It is a testament to the research and persistence of Andy Friend and James Russell. And it demonstrates the astonishing vitality of Ravilious's artistic circle - the women and men who trained and worked alongside him. It seems a good time to try to pin down the reasons why I find his pictures so engrossing and a continual source of visual pleasure.

Sussex, Summer 1939:

A tea-table stands in the corner of the garden. The milk-jug and plate of butter are shaded by a battered umbrella. The warm air smells of fresh bread and new hay. Peggy Angus is expecting visitors. She leans on the wall, her cotton dress flapping against her bare brown legs, humming snatches of old tunes. At the end of the track she sees them, dark figures against a chalk-white ground, a man and a woman carrying knapsacks and painting gear. Eric Ravilious and his love Helen Binyon walk up the long lane from Glynde Station. Refugees from the clatter of London, for a few days they can shelter beneath the open skies and lark-song.

A tea-table stands in the corner of the garden. The milk-jug and plate of butter are shaded by a battered umbrella. The warm air smells of fresh bread and new hay. Peggy Angus is expecting visitors. She leans on the wall, her cotton dress flapping against her bare brown legs, humming snatches of old tunes. At the end of the track she sees them, dark figures against a chalk-white ground, a man and a woman carrying knapsacks and painting gear. Eric Ravilious and his love Helen Binyon walk up the long lane from Glynde Station. Refugees from the clatter of London, for a few days they can shelter beneath the open skies and lark-song. Peggy’s cottage, Furlongs, sits beneath the swelling Sussex Downs. It is a place of retreat for her artist-friends, a survivor from quieter times. While Britain prepares for war, a procession of shire-horses and wagons pass her gate, and her front door stands open to the breeze and sunshine. Her fellow-students from the old days at the Royal College of Art make their pilgrimages here. In her small sitting room, beneath a ruby-glass oil lamp, the artists gather: Eric and Helen, Edward and Charlotte Bawden, John and Myfanwy Piper. They share a desire to catalogue the small wonders of the English landscape. Knowing that their world is under threat, the need to paint becomes more urgent. They are the inheritors of the visionary Romantic tradition, heirs to Samuel Palmer. Yet their art is sharp and never sentimental. It is underpinned by a radicalism drawn from the utopias of William Morris.

Ravilious makes it his mission to document the ebb and flow of the Downland and its mysterious carved figures, white horses and giants. His incisive eye, his delight in domesticity, his nostalgia and quirkiness suggest parallels with John Betjeman. The lyricism of his watercolours reminds us of Vaughan Williams. Throughout the 1930s Ravilious fashions calm memorials to Englishness: images of white cliffs, greenhouses hung with ripening tomatoes, and ancient paths climbing to the sunlit uplands.

Ravilious makes it his mission to document the ebb and flow of the Downland and its mysterious carved figures, white horses and giants. His incisive eye, his delight in domesticity, his nostalgia and quirkiness suggest parallels with John Betjeman. The lyricism of his watercolours reminds us of Vaughan Williams. Throughout the 1930s Ravilious fashions calm memorials to Englishness: images of white cliffs, greenhouses hung with ripening tomatoes, and ancient paths climbing to the sunlit uplands.And then the war breaks in. Ravilious, Piper and Bawden join Kenneth Clark’s band of official war artists. Bawden is posted to North Africa and turns his hand to painting the vast theatres of war in Libya, Iraq and Ethiopia. Piper sits with his sketchbook in the smouldering relics of Coventry Cathedral. And Ravilious is offered a commission in the Admiralty. He records coastal defences, submarines and docks around the South Coast and in Norway. Then in the summer of 1942 he is sent to Iceland. On 2nd September his plane disappears over the sea, and he is lost.

**********************************************************************************

By tracing the patterns of friendship between Ravilious, Bawden and their circle, the exhibition offers an alternative history of English art. Furlongs was barely five miles from Charleston, Virginia Woolf’s Sussex home. Like Charleston, Furlongs provided the backdrop to love-affairs and intrigues. But the artistic atmosphere of the two meeting-places could hardly have been more different. The Bloomsbury group were self-consciously modernist. The folk at Furlongs, on the other hand, embraced the traditions of English watercolour painting and wood-engraving. Their work was intimate and evocative.

By tracing the patterns of friendship between Ravilious, Bawden and their circle, the exhibition offers an alternative history of English art. Furlongs was barely five miles from Charleston, Virginia Woolf’s Sussex home. Like Charleston, Furlongs provided the backdrop to love-affairs and intrigues. But the artistic atmosphere of the two meeting-places could hardly have been more different. The Bloomsbury group were self-consciously modernist. The folk at Furlongs, on the other hand, embraced the traditions of English watercolour painting and wood-engraving. Their work was intimate and evocative. Ravilious traced the curl of a Swiss-roll with as much care as he mapped the course of a river. He and his friends loved trips to the seaside, DIY and bunting, Bonfire Night and evenings in the pub. Benjamin Britten and Henry Moore crossed their path, but this group of artists chose not to follow their lead. Instead they painted ordinary beauty, glimpsed from a train window. Their visions of Englishness have become more poignant as the years have passed. We now celebrate their legacy in exhibitions, calendars, notecards and fridge magnets. ******************************************************************************

Our first sight of Eric Ravilious is likely to be low key and domestic. He slips quietly into our lives, with his black-and-white designs for the breakfast table. We follow the undulating dot-and-dash around the rim of a bowl. Then we start to feel our way into one of his landscapes, pushing through a wire fence, up a path, over the Downs. Next, we become entangled in a coil of rope washed up in a watercolour. Before we have quite realised what is happening, we are smitten. Ravilious has cast his spell.

Ravilious’s ability to enchant was recognised by his early friends and critics. Fellow-students at the Royal College of Art called him ‘the Boy’. In 1939, his pictures were described as ‘something magic, almost mystic, distilled out of the ordinary’.

With a ruler and a pencil he draws a web of lines. They might become ceiling joists or floorboards, a quayside, a runway or young crops in a field. But they are never exactly aligned with our idea of perspective. His rooms are slightly aslant, his table-tops are tilted. He keeps us on our toes, a little anxious that the image could slide away from us or trip us up.

This is one of his magic tricks. Ravilious offers us pictures that at first sight seem straightforward; as he said when he drew the folds of the Sussex Downs, ‘the design was so beautifully obvious’.

This tendency becomes more marked from 1940 when he begins his War work. Ravilious’s paintings and lithographs lead us into empty huts, then down into tunnels hung with maps and out onto icy seas. His eye dwells on the uneasy interludes that punctuate conflict. He shows the steady administrative tasks – telephone calls, filing cabinets, test flights – underpinning the drama of war. Occasionally he treats us to a burst of artillery, blazing from a 9.2 gun positioned high above the coast.

This tendency becomes more marked from 1940 when he begins his War work. Ravilious’s paintings and lithographs lead us into empty huts, then down into tunnels hung with maps and out onto icy seas. His eye dwells on the uneasy interludes that punctuate conflict. He shows the steady administrative tasks – telephone calls, filing cabinets, test flights – underpinning the drama of war. Occasionally he treats us to a burst of artillery, blazing from a 9.2 gun positioned high above the coast.

In 1941, the same year that Ravilious painted his bright gun, an appreciation of Blake was published by David Cecil in The English Poets. According to Cecil, Blake’s poems were like ‘a rush of the wind in the tree-tops’ or ‘a fresh gale, racy with the smell of earth’.

Clark oversaw a thoughtful and energetic project, encouraging modern painters to respond to the new face of combat. This was no exercise in nostalgia. And Clark did not keep his artists out of harm’s way. In Ravilious’s case, with his work for the Admiralty, his subject was the fragile edges of Britain. He painted a coastline defined by new concrete defences and curls of barbed wire, with the pleasure boats drawn up high onto the beach to sit out the war. There is the recurring motif of the lighthouse marking the intersections between land, sea and sky. Ravilious was particularly fond of the stumpy towers at Newhaven, as well as the elegant tension between curved and flat in the lighthouse at Rye. Sometimes in his paintings they shine into the darkness. More often, though, they are unlit, upright and waiting. Very occasionally, as in Belle Tout interior (1939), Ravilious shows us the view from inside the lantern, the sunlight streaming in through the window panes, almost too bright to look at. A calligraphic line dancing across the paper marks the boundary between land and sea.

Ravilious delighted in rippling borderlines. We find them at the scalloped edges of sandbanks as they dip beneath the waters of Rye Harbour (1938).

They mark the gap between grass and tarmac in Runway Perspective (1942).

And most spectacularly, Ravilious created a sparkling thread of water flowing through marshland in Cuckmere Haven (1939). Here the meander of the river is echoed in the ribbon of a chalk path through the grass, and even in the cloud formations. Earth, water, sky are linked and defined by the looping lines of Ravilious’s pencil.

And most spectacularly, Ravilious created a sparkling thread of water flowing through marshland in Cuckmere Haven (1939). Here the meander of the river is echoed in the ribbon of a chalk path through the grass, and even in the cloud formations. Earth, water, sky are linked and defined by the looping lines of Ravilious’s pencil. However, he is careful not to let us become lost in a watery maze. A stone wall and a field in the foreground create a gently sloping springboard. From here the acrobatic elements in the composition can rise, soar, twist and come to rest again. In every watercolour there is an underpinning, an architecture which is laid down first. It is rarely quite on the square, and this contributes to the tension between solid and line. But nevertheless, Ravilious mapped the geology of his landscapes and the girders of his underground corridors in pencil, before he explored their more delicate edges and crossing points.

This exhibition allows us to follow the threads back to his early years as an art student, and forward towards his work in Norway and Iceland. It reveals the strands that link him to the avant-garde of the 1920s and his place in a wider circle of artists who wrote and thought and travelled in interwar Britain. It also asks us to consider how the loss of his aircraft in 1942, missing (presumed dead) before his 40th birthday, altered the reception of his art. Above all, these displays allow us to linger, to delight in the complex surfaces of the watercolours, and the enjoy the intricacies of his black and white designs.

David Cecil, English Poets, from Britain in Pictures series, London, 1941, pp. 9 & 20

Published on January 16, 2018 13:48

November 15, 2017

The Pre-Raphaelites in TuscanyEdward Burne-Jones, The Mir...

The Pre-Raphaelites in Tuscany

Edward Burne-Jones, The Mirror of Venus, 1875

In the golden autumn of 1859 Edward Burne-Jones and his two friends awoke in Florence. They had already spent several days in Pisa sketching frescoes in the Campo Santo. They were there on the advice of the critic John Ruskin. The young painters had come in search of the real Pre-Raphaelites – artists like Giotto and Fra Angelico who had flourished in Tuscany at the moment when the Renaissance began to emerge from the late Medieval world. And now they were staying in the heart of Florence. On their rambles around the city, as yet untouched by tourism, they stumbled upon angels and Madonnas, tucked away in green cloisters and tiny chapels.

Workshop of Botticelli, Coronation of the Virgin, 1475-1500, owned by Edward Burne-Jones

Above all, they were smitten by Botticelli. Burne-Jones wrote lovingly about ‘a coronation of the Virgin…heaven beginning six inches above our heads as it really does. It was terribly neglected and stuffed up with candles’. In the Accademia, the Pitti Palace and the Uffizi he discovered more delights – ‘the Spring’ and ‘the Dancing Choir’. By the late 1870s, the infatuation with Botticelli was so prevalent among avant-garde British artists, that it was parodied by Punch, and Gilbert and Sullivan. But Burne-Jones was a pioneer in his enthusiasm. The sweetness and otherworldliness of Botticelli’s wistful Madonnas found a new life on his canvases.

Botticelli, Madonna of the Magnificat, Uffizi, 1481

The impact of this first visit resonated for decades: ‘Oh dear’, he sighed as he finished breakfast in his studio-house in London a while later, ‘when I think that this very morning Florence is going on, and I have to go into that muddle of work upstairs.’ But before he went home, he was able to saunter through Siena, take tea with Elizabeth Barrett Browning, and study the sculpture of Pisano in the Cathedral there.

Siena CathedralI have recently been able to follow in Burne-Jones’s footsteps, leading fellow Victorian art lovers around Tuscany. We revisited the medieval cities that he saw as a young man, and those that he was drawn to as he grew older – Siena, Arezzo, San Gimigniano and of course, Florence. Looking at the early Renaissance through the eyes of 19th century artists and poets, we found our way back to a freshness, a more vivid encounter with well-loved images. The wall-paintings of Gozzoli and Pinturicchio, the altarpieces of Duccio were almost unknown in Victorian Britain. Burne-Jones came home exclaiming, ‘I want big things to do, and vast spaces, and for common people to see them and say Oh! – only Oh!’

Piccolomini Library, decorated by Pinturicchio, 1402-7, Siena CathedralDante’s Divine Comedy was available in English, thanks to Henry Cary, but was still an acquired taste. Burne-Jones’ friend and fellow artist, D G Rossetti did not publish his translation of Dante’s ‘Vita Nuova’ and ‘The Early Italian Poets’ until 1861.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Giotto drawing a portrait of Dante, watercolour, 1852, Private Collection

These young Victorians were breaking new ground in their desire to explore and reinvigorate the art of Italy before Raphael. But within a few decades, word had spread, and there were 30,000 English and American residents in Florence, drawn by the climate and the culture.

For my part, as a history student who was enamoured of the Burne-Jones and Rossetti drawings I had seen in the Ashmolean, I came to Florence for the first time in 1989 with my head filled with Pre-Raphaelite drawings of Dante’s Beatrice. The two worlds – the Victorian and the early Renaissance – were intertwined. I saw Botticelli’s heavenly figures, and remembered Burne-Jones’ response to his upbringing in industrial Birmingham: ‘the more materialistic science becomes, the more angels I shall paint.’ These were his prototypes. But it wasn’t just the subjects, but the manner itself that was drawn from the Italian Quattrocento. There was kinship in the delicacy of the swaying figures, the blue of the skies above and the green of their gowns.

Edward Burne-Jones, The Garden of the Hesperides, 1869-73, Kunsthalle Hamburg

This is a timely tour, giving us a chance to look again at Burne-Jones as we approach another anniversary year, with a major exhibition of his work at Tate Britain in 2018. Without his encounters with the fresco-cycles of Pisa, the refined panel-paintings of Florence, and the solemn church decorations of Arezzo and Siena, his yearnings for the landscape of his imagination would have been unfulfilled. As he wrote to a friend, many years later, ‘I belong to old Florence.’

Published on November 15, 2017 13:39

January 14, 2017

The Flowering of Aestheticism: Lily, Sunflower and Azalea...

The Flowering of Aestheticism: Lily, Sunflower and Azalea

Albert Moore, Azaleas, 1868

Art historians at the University of York are looking ahead enthusiastically to the Albert Moore exhibition, opening at York Art Gallery in April 2017. So, in response to the abundance of flowers in Moore’s work, we have been discussing the theme of floral imagery in Victorian art.