Alison Dotson's Blog, page 3

December 1, 2021

The ocdopus: Elise Petronzio

We’ve all seen “cute” OCD jokes on things like T-shirts and mugs (and scented candles and hand sanitizers and soaps and…), and many of us with obsessive-compulsive disorder don’t think they’re funny. A lot of us think they’re actually harmful to people with OCD and get in the way of spreading awareness of what OCD really is. Very few of us, however, have taken it several steps further and started our own line of awareness-building merchandise! Meet Elise Petronzio, who did just that with her shop, the ocdopus.

Your OCD advocacy and recovery shop, the ocdopus, recently turned a year old! First of all, congratulations! Can you tell us more about it? What inspired you to start it?

Thank you so much! I sell things that motivate people with OCD to work toward recovery, as well as advocate for what living with OCD is really like. Things like a “maybe” beanie or an “embrace uncertainty” bracelet are quick, visible reminders of what we are working toward in our everyday lives.

I was inspired to make merchandise because OCD tends to be joked about on T-shirts, home decor, etc., more than other illnesses I’ve really ever seen. This joke merch minimizes OCD to our whole society and is a big challenge in OCD advocacy. It’s hard to believe OCD can be what’s wrecking your life when you see someone with an Obsessive Christmas Disorder T-shirt. I also noticed there was not a lot out there that incorporated what we learn in OCD treatment. I wanted to make things that were specific to our community and really spoke to our experience.

How long have you had OCD, and when did you realize what you were going through was OCD?

I have had OCD since I was at least ten. I showed compulsive behaviors by age six, but it hit the fan right before I turned ten. The therapist at that age I saw was helpful, but did not believe in labeling. I started to see people mention Pure O when I was googling my intrusive thoughts in high school. I self-diagnosed before receiving a formal diagnosis at age twenty.

Did you tell your loved ones about your diagnosis?

I don’t think I have any friends who don’t know about it at this point. When it comes to family, I’m not as forward as I am everywhere else. My distress was obvious from a young age and they saw it, it just wasn’t named. I was diagnosed over ten years after my symptoms began, so it makes the order of it all a little strange. This also means they’ve witnessed parts of my recovery and relapses, but we were all a little late on putting the pieces together, and I think that’s hard to understand. I also feel a little differently when I’m talking to different generations about mental illness. It’s an interesting dynamic to be super open in some places and not in others.

Let’s say you’re out getting coffee and someone in line asks what your Maybe beanie is all about–but you only have a few minutes! What would you tell them?

“This beanie is actually from an Obsessive Compulsive Disorder awareness shop. It says ‘maybe’ because people with OCD have a very hard time dealing with uncertainty, which is why they do compulsions to try to lessen their discomfort. For example, checking the stove because they want to be sure they are not going to burn down the house. It reminds people with OCD to say maybe to these obsessions and keep moving through their day when they’re tempted to get caught up in compulsions instead. It’s not exactly what people think OCD is about, right?”

Pink elephant hoodie

Pink elephant hoodieA few years ago Target had a line of ugly Christmas sweaters that included one with “O.C.D. Obsessive Christmas Disorder” on the front. I tweeted about it and was interviewed by a local news station about my thoughts, and I got so much hate! People felt the need to track me down and let me know what a snowflake I was (I guess it was almost Christmas!) and that I didn’t have a sense of humor. Have you had any experiences like this when trying to spread awareness of OCD? And have you had the opposite response with your awareness-raising merch?

I’m glad you stuck up for it and managed to get some traction! The hate definitely stinks though. I have actually had few experiences like that. My followers tend to be in the OCD community themselves and relate very much to what I say about OCD. Even on TikTok, I have not really had anyone come down on me, only people who were curious/confused about what OCD really is. I have been trolled for my appearance or just in general on social media while doing advocacy though, but never about the OCD advocacy itself, actually!

I’m not what the kids today would call young, so I love that you’re on social media with entertaining messages—especially TikTok. How can younger people advocate for OCD awareness? Any advice for those of us who are shy about being on camera?

I love TikTok. Easily my favorite social media platform. It’s filled with so many creative people and ideas, and it’s easy to see content from people you’ve never interacted with before. This makes it a really great place for OCD advocacy. It’s definitely where I’ve met the most people who were newly diagnosed with OCD or have never met others with it.

“Embrace uncertainty” bracelets

“Embrace uncertainty” braceletsThe good news is there are many ways to make videos without being on camera. People often film things they’re doing and tell stories through a voiceover or through their speech-to-text feature. Someone may be baking a cake and telling a story about what happened in school that day. You could easily bake a cake and just film the decorating process and talk about OCD and it wouldn’t actually be that surprising to people.

I also find being on camera easier on TikTok because I tend to just use sounds and mouth the words, it’s not actually me talking. It’s not the same as going live on Facebook or even filming a video of yourself speaking and posting it. Also, you can redo it if you don’t like it, but for people with OCD that can definitely be a tricky area.

If you could give someone with OCD just one piece of advice, what would it be?

If you can find a way to get treatment, go! (A favorite resource of mine is NOCD’s free support groups, accessed at treatmyocd.com or the NOCD app.)

November 11, 2021

Living Beyond OCD: Patricia Zurita Ona

I’m honored to welcome back Patricia Zurita Ona—Dr. Z—to the Q&A! Dr. Z has written a workbook for adults with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) called Living Beyond OCD Using Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: A Workbook for Adults and hosts a podcast called Playing It Safe, and we talk a lot about the concepts she explores in both projects—ACT, considering our values when we decide to face fears, approaching therapy with compassion, and more.

Tell me about your podcast. What’s it about? Who’s the audience? Why did you start it?

It’s another project from the heart. I was initially going to launch the podcast in 2022, but with COVID everything got put on hold, my book, my online class, I have this itch. I love creating things, so I decided to launch it in 2021. The podcast is called Playing It Safe. The purpose of it is sharing evidence-based and research-based skills for any person struggling with any type of fear-based struggles.

When we think about anxiety or fear-based struggles, very quickly we’re thinking about these disorders: social anxiety, OCD, panic attacks, and, yes, they are real and they exist, but also fear and anxiety are a common human experience and a day-to-day experience. Think about a mother who is afraid about her kid who is African American going to the streets and being shot. Think about the firefighter. Think about that surgeon who is performing heart surgery. Fear is a human experience and it’s embedded in our day-to-day life. Sometimes we feel it more than other times, and sometimes we handle it more effectively than other times. But, we all play it safe when dealing with fear. At times we play it safe by trying to do things right and perfect, by postponing, by avoiding, by overthinking, by anticipating that it’s going to be bad, terribly bad, by doubting ourselves. Sometimes those playing it safe actions work in our favor, sometimes against. The purpose is basically for any person experiencing fear in their day-to-day lives. It’s for the person who comes to therapy and they know they are struggling with social anxiety and panic attacks, but it’s also for the person walking in the streets, outside the coaching or therapy office. In a nutshell, I’m trying to normalize the day-to-day experiences of fear.

Do you think there are people who engage in these fear-based behaviors of avoidance and stuff who don’t realize that it’s fear? Maybe they don’t even really know they’re doing it, or maybe they would just never call it fear, they call it something else.

You know, the challenge with fear is that it doesn’t have good branding, we don’t talk much about fear; people will talk more about stress or anxiety, and I certainly have looked at gender-based differences in how we identify our struggles, but you’re right.

Anecdotally, I can tell you that there is a small group of people who acknowledge and notice when they are scared or afraid and we do have a large crowd who would say “I’m stressed, I’m upset.” People recognize when they are angry, depressed, but I don’t think we have been socialized to accept fear as part of our day-to-day life.

Your most recent book that came out was for teens, and now we’re moving on to adults. Do you want to talk about that decision? Are you trying to hit everyone who needs it, who needs ACT, who needs the workbook?

I’m a big proponent of the idea that one size of exposure doesn’t fit all. I think how people relate to obsessions, fears, panics, and worries is very different from person to person and it is important to acknowledge that there are different treatment options that are also research based. The research has been very consistent—for adults and teenagers—shown that ACT involves ERP and ACT is ERP already and is highly effective for OCD. What I wanted to do with the workbook is to show people that they can learn ACT skills in a way that is jargon-free and more accessible and perhaps relatable.

One variation that I encountered in my work with adults is that, at least in my experience, is very important to help people develop a new relationship with their thinking, with the mind, and with all the messages they have received about worries, fears, and anxieties before doing an exposure. Some people in the field may do a lot of mindfulness-based exercises in addition to ERP, and that’s one way of doing it. In my work what I have found is that especially in the case of OCD and chronic worry, there are some ruling thoughts or some sticky thoughts that people are holding onto with white knuckles, like “Because I think so it makes me so, if I have an obsession about being a pedophile it makes me a pedophile” or if I am thinking a lot about this thought it means it’s important and I have to respond to it. Or if that thought keeps showing up in my mind it’s because it’s showing something important about myself.

The challenge is that all those thoughts are not flexible. OCD literature has talked about thought-action fusion but what we have is a bunch of ruling thoughts that actually undermine exposure work, so even if a person can be ready to do exposure, the mind is still going to be going on and on, like are you sure you don’t want to do that compulsion you have to do it you are endangering someone if you don’t do that compulsion it is the same as causing harm to another person.

I’ve found that if we help people with these microskills to learn how the mind works, to notice that the mind has a life of its own, to notice that the mind will come up with all kinds of hypotheses, explanations before doing exposure work I think we have a larger chance of people responding in a more flexible and curious way to the process of facing their obsessions.

In the workbook there is a whole section on ruling thoughts. I have identified nine ruling thoughts: because I think so makes me so, if I think a lot about it it’s important, not doing my compulsion is the same as causing harm, and I teach clients microskills to tackle each of them. All of that is with the purpose of noticing that the mind has a life of its own, which I think is very, very important. In ACT, we already know that, we’re already stepping back and watching our own mind. But I know for my clients it feels like a foreign concept, and it’s very counterintuitive. So I have found that doing that when I’m teaching these skills for ruling thoughts, it’s really about creating a context of change. I have found that very helpful in the work. There’s a whole section on that. From that we move into the values-based exposure menus, which I think offers people an opportunity to really tackle what matters to them based on what is important. I don’t use hierarchies, I don’t keep track of anxiety because it’s easy to get hooked into this idea of exposure is about getting rid of anxiety, thinking more about how you’re holding onto the thought. Are you holding the thought like this? [Dr. Z is holding her hands in tight fists.] Are you holding an obsession like this? Are you watching it? Can you visualize it? How do you see it? How does it look? How does it sound? And I also talk about these W.I.S.E. M.O.V.E.S.

W.I.S.E. M.O.V.E.S. is an acronym for people to remember microskills about how they can face their fears. Here is the background: When I was delivering ACT exposures, many times my clients ask me “How do I do this? In the session I see it, I feel it, but how can I practice this in my life?” And as usual my clients are the best teachers I have ever had in my whole life. It’s their questions that always make me pause. And it’s because of those questions that I ask myself, okay, how can we make this more accessible for them so they know what to do and how to handle those moments of stuckness. W.I.S.E. M.O.V.E.S. stands for:

Watching your mindInviting your obsessionsStaying with your experience—remember that you can make a choice, either to your values or away from your values.The M stands for making a choice.The O stands for observing what comes with making a choice—which is super important because if we’re doing exposures, and we are attached to the idea that if it’s going to work I will have less anxiety, I don’t have the obsession, it undermines the process. But if you make a choice and you’re willing to be curious and watch what happens when you touch something that may feel contaminated.The V stands for validating the effort you did. Exposure is hard work. It’s not easy. Many times I have seen my clients engaging in these very tough self-criticism judgments, so I think appreciating the effort is important.The E stands for engaging with life. Life is about living, life is not about dwelling in our head but what happens is that many times after an exposure, or when people get stuck, they actually keep dwelling and ruminating on it.My invitation is for people to practice W.I.S.E. M.O.V.E.S. and remember that life is happening in front of them; whether you’re watching a movie or you’re listening to music, whether you’re talking to a friend, whether you’re playing with your puppy, there is life happening.

Personally, I think ACT offers a more compassionate way of looking at exposure but it’s also more validating of the fact that when doing exposures there are not always going to go great, and this also applies to compulsions.

I have heard from my clients that sometimes they say, “Dr. Z, I got stuck.” Those kinds of stuckness are part of the process and not signs that they are doing something wrong. To me it’s important, yeah, that happens. Sometimes we do a mental or physical compulsion, but what do we do next? Where will life take us from there? I think it’s a more flexible and softer approach I have tried to write about.

I know that I would appreciate a softer approach. I think some people want tough love, or they don’t want it to be touchy-feely at all, you know, they just want it to be like, “Do this,” but I feel like it would be so helpful to so many people when you do put the values around it, because then there’s a meaning to it, and I feel like that’s more motivating.

I know that I would appreciate a softer approach. I think some people want tough love, or they don’t want it to be touchy-feely at all, you know, they just want it to be like, “Do this,” but I feel like it would be so helpful to so many people when you do put the values around it, because then there’s a meaning to it, and I feel like that’s more motivating.

I think it’s a very different story to do an exposure because the therapist says so or because exposure is an evidence-based treatment versus saying yes to this awful feeling because it’s important to me to be the person I want to be. It’s very different.

In my opinion, behavior therapists, we are also a tough crowd; we may try sometimes to go quickly into the change phase—certainly in my training I have been one of those therapists. And, I also think that one of the powerful things that ACT has to offer to clients is that it teaches them—it teaches us, all of us—the skills to face life with all of the worries, obsessions, and fears we have. When you think about it, this approach of “just do it and be tough” puts a person on edge. They’re hyper-aroused.

Let’s think about this for a moment, who learns when feeling stressed or hyper-aroused? We know, you know by hundreds of studies, that we don’t learn much when we are very stressed or under high levels of hyper-arousal. And the new research on exposure has shown that that is not necessary for exposure to work. In fact, what we need is more variability of experiences, more variability of exposure exercises.

I think certainly facing an exposure comes with degrees of uncomfortable affect and stress because that’s the work, but it doesn’t mean that we have to quickly push the envelope. I am more invested in helping people to find their own rhythm, to face what matters, to be in charge of the process and be curious about it. And just to clarify, that doesn’t mean that we’re not going to do hard exposures.

I think my clients are incredibly courageous people and they are doing very, very tough exposures, but what is different is it doesn’t matter for how long they’re doing their exposures or how fast they’re practicing them; the emphasis is on them choosing how they are approaching their fears. They are always in charge, and they are the ones deciding how much they do it, how long they do it, how they do it.

Within ACT, there is so much engagement in this process, and you have less dropouts from treatment because a person is so much more engaged in their exposure process. Also, when we give people permission to have an imperfect exposure because that sometimes happens, we also normalize the message that there is no such thing as either/or when facing your fears; learning to live with fears and worries is a process.

Within ACT, we learn to accept and appreciate how hard the process of living with fears is and we learn to make choices—and as long as we are watching the choices we’re making and keep moving, things will work out fine. That has been a very powerful approach in the work I have been doing.

This has been a very rich experience for my clients. Some of them have been exposed to other approaches you mentioned, the “just do it” type of thing, and they noticed how hard it was to drop the compulsions or do exposures. When we switched gears all the way to ACT, one of my clients noticed that he wasn’t afraid as much and that he can actually choose so much more to disengage from compulsions and face obsessions. To me, those are sweet moments to capture. ACT offers something more flexible and compassionate approach and it can be very empowering for people.

It kind of makes me think of weight loss approaches people have sometimes, or getting in shape, where it’s like, “I want it to happen quickly now that I decided I want to make a change, I’m just going to go full bore into it” and then they stop doing it. I’ve done that myself, where I’m like, “I’m going to work out every day!” and then you end up hating working out, you’re sore, and you can’t see the point of it. If you have an easier approach into it or even thinking of your values around it, like “I want to work out to strengthen my heart because I want to be able to hike with my dogs” or something like that.

I think you’re making a really good point—we do have the data in other areas about what happens when people go quickly into the change side of behavioral approaches. Of course we’re advocating for a behavioral change. The challenge is that it makes a huge difference when we tell people let’s stand back, and watch what our mind is doing; watch how your mind has a life of its own, watch how your mind quickly wants to solve this.

All of us know when a person wants to do exposures and hammer exposures; we also know how in therapy that approach gets reinforced many times. Everyone can do that, it doesn’t mean it’s going to help our clients.

To me that’s an old-school belief. What happens if we teach people to learn to watch their mind, and that’s the beauty of mindfulness. For instance, in the case of OCD and chronic worry, the ruling thoughts need to be much more targeted. The umbrella of their particular ruling thoughts are driving very problematic behaviors; so I think, if we teach people to step back from their thinking that before any exposure work, which seems counterintuitive, it makes a huge difference in the long run.

Another thing that came to mind when you were talking is—and actually, I’ve thought about this a lot beyond this conversation—ERP and exposures for the sake of exposures. I wonder if they can be traumatizing for people if it isn’t connected to values at all or if it’s just really harsh. Even if you want to get better, if the idea of this exposure is so terrifying, maybe getting super graphic with a sexual obsession or something and you don’t really know why you’re doing it and it’s just upsetting. Is there evidence for that, that there is trauma sometimes, that people have negative effects from therapy? Even if the anxiety goes down, then there’s something else?

That’s a good question. Here’s what I can tell you: Years ago, I had a client with obsessions about a partner cheating on him and he read all the books, he’s googling, he’s searching on YouTube, very well-versed. My client read and heard that exposure would be imagining the partner having sex with another person. Who wants to do that in life? Why would I want that for myself? Why would I want that for my client? That was the main reason why that client, for maybe five, six years, didn’t enter into treatment.

We do know that in research settings an average of 20 to 35 percent of people don’t start treatment. I think this is the part that we have been missing many times—and it’s possible that there has been a shift, because exposure therapy and research in exposure has switched in the last few years. I haven’t seen that data though.

Practicing exposures is about approaching what is aversive, for example, fears that my partner cheated on me, but those fears are in relationship to the different behaviors that affect a person’s life. So, for example, in the case of my client—and I did exactly what I described in the workbook—we assessed how OCD shows up, we distinguished mental compulsions—those mental compulsions were primarily focused on replaying how my client’s partner talked to him, talked to another person— there were a lot of avoidant behaviors. We looked at the ruling thoughts my client was getting hooked on.

Then, based on the values-based exposure menu we developed, some of the exposures exercises were about my client and his partner hanging out with other people that are considered attractive and teasing my client’s partner with silly comments: look at this hot person; my goodness this person is so hot…look at their bodies…oh my goodness. Other exposures included watching movies with characters that were considered attractive to my client’s partner.

It’s a human experience to doubt whether a person loves us or not. In the example I’m sharing, we never did the exposure of my client imagining his partner having sex with another person. During treatment, my client decreased all these avoidant behaviors and now he’s fully in a beautiful relationship.

To answer your question, to my knowledge there is no data showing that we need to do extreme exposure exercises or always start the treatment there. There are some ACT folks who would do it, I have heard that. I don’t do that. If necessary, I will augment exposure exercises to extreme forms, always in collaboration with my clients. But, to me the beginning of exposure work is always a person’s life, I would always ask things like: how is this obsession affecting your day-to-day life? And let’s start there.

I have clients who certainly are very fused with their obsession like, what if I am emotionally abusing my children? And as a result, my client wouldn’t reprimand the kids when they’re misbehaving, was afraid that if she raised her voice, what if someone calls CPS?

In that case, because those obsessions were very, very sticky after many types of exposures, we augmented the exposure exercises and ended up doing something a bit different: we wrote flashcards: “I am hitting my kid” and we left the flashcards in the bathroom. That is a very tough exposure, but again, we didn’t start our exposure work there.

Sorry if I’m repeating myself here, but I don’t think there is this rule that you should go there right away or that you always have to have intense exposures. To me, it is more important to train my ears and my eyes to notice how sticky an obsession is, how much my clients are moving from holding an obsession as a truth or fact or how much they are just having it.

And if we have to intensify exposures, it’s always with clients’ permission, always. Now, when we think of trauma I think it’s helpful to clarify what PTSD is and how even when a person doesn’t have PTSD but have a history of trauma may still be affected by it. So, the criteria for PTSD is that a person re-experiences a traumatic event, is hyper-aroused and engages in avoidant behaviors, all related to a traumatic event. Now, even if a person doesn’t have the classic symptoms of PTSD, they also may have developed a belief system about themselves, others, and the world.

What I have heard from clients I work with is that first, intense exposures done without any preparation actually contribute to more hyper-arousal, so that will decrease a person’s capacity to face an obsession. And secondly, is that those intense exposures sometimes reinforce the belief that they cannot handle an exposure.

So, those beliefs are brutally hard in treatment. Think about it, it’s already hard to go to therapy, it’s already hard to tell a therapist when you’re having more shame-based obsessions, and then on top of that you have to do one of these awful things? That would reinforce the fear that they can get better and that there is something really wrong with them. I have heard more about those experiences as a reaction to these intense exposures.

I would think, especially if you’re still in a really bad place with your obsessions, the last thing you want to do is feel even worse. If you’re going into it thinking, things are going to be so much worse or I’m going to be more scared of stuff. I love that there’s a softer approach to it, and it doesn’t mean it’s any less effective.

Exactly. I think one of the frames I like to use in my work is clarifying that there is our comfort zone, there is our learning zone and there is my burning out zone. Yes, exposures are about getting out of our comfort zone, but we don’t have to reach a burning out zone. It’s not necessary.

I actually think it’s much more powerful for people when they have the freedom and if needed we can intensify things, but there are certain exposures I don’t do in day-to-day life. It’s always a great beginning. It’s the place to go. I know first hand that my clients didn’t start treatment because they were afraid what exposure would entail for them.

For instance, I had another client, a mother whose fear is of stabbing her children. That’s brutally painful when you really think you want to be a mom and imagine how awful it is to think you have the ability to harm your children. In a traditional model, exposure would be “Imagine you’re stabbing your children,” and I know for some people that has worked. We know that.

But I don’t think one-size exposure fits everyone. For some people that’s the barrier, it gets in the way of them getting help. So with that particular client for example, I never did any exposures about her imagining stabbing her children. We never wrote an imaginal exposure about it. We did more situational exposures about noticing when the obsession show up, how she’s going to name it—my client had a name like a murder movie—spending time with her children and participating in different activities: walking to the park, playing, cooking in the kitchen with them around. A lot of that work was also done on reducing accommodations my client’s partner was making. Again, the treatment was about connecting with the kids (my client’s values) and never did an imaginal exposure. That’s another case in which I didn’t have to push the envelope, it wasn’t necessary.

In the book, you have a section about what this book won’t do or won’t ask you to do, and I love that. One of the things was we won’t focus on your past. Can you say more about that, why you think that that’s important?

As a principle, I don’t think we can understand who we are today and our stories without understanding our history and our context. So, I think our behavior is always understood in the context of all experiences we have had in our lives.

In the book, Living Beyond OCD, I wanted to create a self-help program that will guide a person through how to use ACT and exposure skills, and gradually and progressively move into their lives. Many times I have heard from my clients how they spend two, three months and even years unpacking their stories. I am not saying it’s necessarily bad, I’m saying that the purpose of the book is to help people to get back into their lives.

In therapy, yes, we can’t understand that person’s context and history, but our histories don’t define us. Life is happening tomorrow and in the next couple of hours, not before. Also, in the case of OCD we know that a mental compulsion is going back into the past with what-if scenarios, and it’s easy to fall into that compulsion, so going back into the past is not necessarily helpful for a reader or any person dealing with OCD.

Right. That was a huge thing for me, and I imagine that a lot of other people with OCD too: Why is this happening to me, is there something from my childhood, is there something I did or that was done to me, and it can be a huge rabbit hole you go down. You’re right, it can be a compulsion, trying to remember, and are my memories correct, is it false memories? I definitely appreciate that it’s just like, here we are, in the present moment, we’re focusing on the present moment, and also, what comes next—not that we can control anything really, but what we have the most control over is how we respond to what’s happening now and the decisions we make. You can’t undo anything that’s happened in the past.

Yes, dwelling or opening possibilities for rabbit holes wouldn’t have been helpful.

Is there anything else you wanted to say about the book?

Thank you for asking that question. I would like to emphasize a couple of chapters in the book: There are chapters about what acceptance is and the difference with fake acceptance. There is a whole section on how create a values-based exposure menu. There is a whole section how to make a shift from reactive moves to W.I.S.E. M.O.V.E.S.; W.I.S.E. M.O.V.E.S. is an acronym I use to remind clients and readers of how they can use ACT skills and approach their exposure exercises. There is a whole section in the most common blocks that people experience when starting exposure work.

The book has 52 chapters and while that’s a large number, if you look at the book, you will see that each chapter is two to three pages so they’re actually easy to read. Chapter 5 and chapter 9 are a little bit on the long side but they cover the different types of OCD and the most common forms of mental compulsions respectively.

We know that OCD has a heterogeneous presentation, OCD can come in so many ways—people with OCD can have violent obsessions, somatic obsessions, harm obsessions, existential obsessions, metaphysical obsessions. So, in chapter 5, I put together a long table that captures many different types of OCD, with the purpose of having one single place people can go to and see, “Okay, which of the obsessions am I relating to?”

This chapter is a starting point to show that the brain will always latch on to anything. I really wanted to do something for any person who is learning about OCD or wants to learn about therapy can go to, so that’s a chapter that captures that. Chapter 9 has this super cool continuum of the different types of mental compulsions the brain can latch on to. From simple forms, like confessing, praying, repeating sentences, to more complex forms like figuring out my past, figuring out what I’m feeling, figure out the meaning of my experiences, playing with what-if scenarios, am I racist, did I say something racist, did I look, did I sound racist?

When we help people understand how they are responding to these obsessions and how mental compulsions work, it can be liberating.

That would be very helpful because it’s something people are always asking, what’s the difference between an obsession or intrusive thought and a mental compulsion because they’re both things that are in your brain. I’m sure seeing a list or chart like that would help clarify things for people.

Obsessions usually come with “What if?” “Did I?” “Could I?” “Would I?” and also obsessions can come in very plain statements and even commands. However, to distinguish obsessions from mental compulsions is helpful to keep in mind that, the first thought that’s the obsession, is in the house. The rest—did I do it, could I do more—that’s a mental compulsion.

The challenge we’re facing is OCD has a very heterogeneous presentation on the content of the obsessions and the form of compulsions. We can classify, “that’s compulsion, that’s avoidance,” but in a person’s day-to-day life, that is hard to catch! However, we can help our clients and the readers to map how OCD shows up in their life, and how they are responding to it. That can be extremely empowering.

In the book I also describe what’s fake acceptance. Every exposure treatment has some form of acceptance; what’s unique within ACT is that we have so many more tools and experiential exercises to practice that and the acceptance process goes beyond obsessions. It actually capitalizes our internal struggles, not just related to OCD.

On the chapter on fake acceptance, people can check whether they’re powering through an exposure, like “I have to do this” versus “I am saying yes to this yucky feeling as a choice” and how I can go to myself with many self-acceptance prompts, like “I will do my best to conquer this,” “I’m doing the best I can,” “I will do my best with this feeling coming and going.”

In this chapter I also describe how a person can use self-acceptance prompts; and just to clarify, I think sometimes people think that in ACT we’re all about minimizing coaching or self-talk. We’re not. There is a lot of self-talk and self-coaching within ACT, and it’s always in the service of what’s going to work and a person’s values. Think about it, many times we all have the need to have these natural verbal reminders. So again, I think that chapter clarifies the distinction between what’s acceptance and what’s fake acceptance.

October 27, 2021

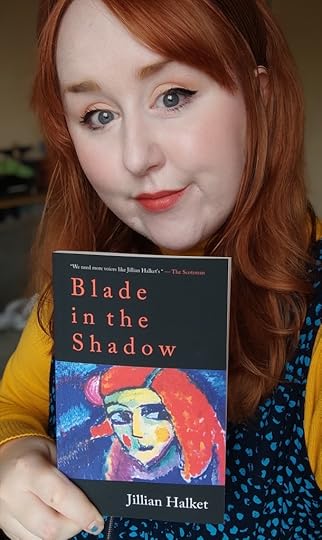

OCD After Trauma: Jillian Halket

Jillian Halket has overcome—and accomplished—a lot in her young life. At just 28 she’s worked through trauma, substance abuse, and undiagnosed obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), and now her first book is out! In her memoir Blade in the Shadow, Jillian shares her experiences with harm OCD and how she tried to cope with it before finally getting the proper diagnosis and treatment. Jillian tells her own story so beautifully, so let’s get to it.

When were you diagnosed with OCD, and how did you realize what you’d been going through was a disorder?

I was diagnosed with OCD at twenty-one.

I’m very grateful that I was diagnosed at this age as I know that it can take a long time for people with OCD to get their diagnosis. However, although it was early in life comparatively, I still spent much of my early life unaware that the intrusive thoughts I experienced daily were part of a disorder.

I struggled with violent obsessions. I thought I was some kind of freak. I tried to hide it—to wear a mask in public and pretend everything was okay but it didn’t work and when I moved away to university at eighteen, I spiraled out of control.

I attempted to numb the thoughts by turning to alcohol and after an experience of sexual assault and my intrusive thoughts increasing in intensity—I turned to self-harm. It was an incredibly bleak time in my life and there are times I didn’t think I’d make it through. But I’m still here and I have my wonderful family and the medical professionals who helped me to thank for that.

Without them I wouldn’t be here today.

I often tell people that I didn’t think I had anything—since my obsessions were largely fears that I might harm others, I thought there was something wrong with me, that I was a bad person. You struggled with violent intrusive thoughts. Did you have any idea that you had OCD?

I had no idea.

I think representation has a big role to play in this. Like many, I associated OCD with contamination or repetitive compulsions only as that was all representation in the media that really existed at the time. I couldn’t reconcile the violence in my mind with what I saw on television about OCD.

In saying that, I remember being completely devastated at a particular episode of Scrubs where Michael J. Fox played a surgeon with OCD. Every time I watched it, I cried at the ending. I couldn’t get it out of my mind. At the time I thought I was just responding to Fox’s amazing performance and the visible pain of his own condition (Parkinson’s) but now I realize I was responding to seeing part of myself reflected on screen.

For years it was the closest thing I had to what was going on in my mind. It’s why I believe sharing our stories is so important. The more representation we can get out there, the more diversity of stories and voices—the better. We all need to see ourselves in reflected in this world and know there is a place for us.

How did it feel to have a diagnosis? Did you share it with loved ones?

I was relieved.

I was sad.

My mama was in the hospital waiting for me and I walked out in a daze with this yellow sheet of paper clutched in my hand. I knew then that there was no going back. This thing in my mind—it had a name. There was no escaping it. No escaping myself. I’d tried that for years. Moving to different places, doing different courses, different groups of friends, different clothes and hairstyles, always trying to be different versions of myself. But in the end, there was no change I could make. It was always there.

And now it was official. That little scrap of yellow paper held the answer to something that had affected my life for so many years. I remember feeling extremely grateful. I now had a name for it. And that meant I could fight. And maybe win.

You recently wrote a book, which came out October 14, 2021. Congratulations! What inspired you to write the book?

Thank you so much. It still feels very surreal.

For a long time when I was at my most unwell so much seemed lost to me. I’m sure a lot of people can relate—when you are your most ill mentally—the future doesn’t exist anymore. So, the fact I’m not only still alive at twenty-eight but that I have this book out there is just beyond anything I could have hoped for. I’m very grateful.

At first, I was just trying to make sense of those difficult years in my life—the mental illness, the sexual assaults, and the alcoholism. Through writing I was able to recontextualize some of the trauma I had been through and turn it into something. I felt a power in choosing creation over destruction.

Then as I read misconceptions in the media about OCD, I became fueled by a desire to add to the conversation in any small way I could. If I’m being honest—I started to become very angry. I’d see the phrase “I’m so OCD!” plastered on shopping merchandise or posts about tidy sock drawers and I just wanted to scream. It upset me to see the disorder being trivialized in such a way. And so, I decided to channel that anger into something productive.

That’s how the beginning of the book came about. I wanted the reader to wake up with me on a typical day and experience the onslaught of intrusive thoughts. For them to see the violent things that bleed into my mind—and the mind of so many people with OCD—on a daily basis. I hoped that maybe after that they would never minimize the suffering of folks with OCD again.

What do you hope readers will walk away with?

The truth is we have no idea what someone else is going through. So be kind.

One email I received was from a woman in her seventies who had gone her whole life with intrusive thoughts and never known there was a name for it. It upset me that she had never had the access to treatment. And yet when I clicked on her profile, I saw her recipes for pumpkin pie and her beach holidays with her grandkids. She radiated kindness and strength and yet no one could know that in her mind there were violent thoughts, obsessions, and trauma. This woman is why I feel so lucky to have this opportunity to tell my story.

Because I believe it is all of ours.

No one gets through this life without being wounded in some way. And in being vulnerable we can foster understanding and realize we aren’t as alone as we might have thought.

Yesterday I was watching an interview with Kathy Bates and she said that storytelling is a way we create empathy. Blade in the Shadow may focus on OCD but in truth it’s a story about healing. About embracing the elemental pain that comes along with living. Of knowing that pain intimately and choosing to stay anyway. I’m glad I stayed. And I want other people to stay too.

What has helped you the most in your recovery process?

I live in Scotland and I was privileged enough to get twelve sessions of acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) on the NHS with a psychologist. The NHS saved my life. I wouldn’t be here without it. Without a doubt therapy was the thing that helped most in my recovery. If you do not have access to therapy at the moment, I would recommend the book The Happiness Trap by Russ Harris for some techniques to help in the meantime. There are also therapists who work on a sliding scale and can offer treatment for lower prices if finances are difficult. There are also free resources online and OCD communities that can help.

OCD is a disorder and like any other disorder—it requires treatment. In the same way you would never tell a diabetic they could do without their medication—I would never say to someone with mental illness that they should try to struggle on without treatment. Now I’m a big advocate for patient autonomy so treatment might look different for different people. Some might be comfortable with therapy or some might need therapy and meds or occupational therapy or inpatient intensive courses or self-help resources and access to a counselling helpline or CBT activities online. But OCD is an illness and needs treatment.

If you could share just one piece of advice with someone who has OCD, what would it be?

You are not your thoughts.

They have no bearing on your character or who you are as a person. Please, if you feel safe enough, reach out to a family member or friend or teacher. If you aren’t ready for that step yet there is information and resources online but please, try your best to get in contact with a medical professional if you have access. OCD needs treatment. Please stay safe and hold on. It won’t always be like this.

September 20, 2021

Working With Parents and Partners: Emily Risinger

If you have obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) or a related disorder, you’ve probably heard how helpful it can be to see a therapist trained in cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), particularly exposure and response prevention (ERP). But what about working with a therapist and your partner so you can take your treatment even further at home—and work through some issues OCD can cause in relationships? Therapist Emily Risinger has worked with parents of children with OCD and partners of people with OCD as well as those people with OCD themselves, using CBT, mindfulness techniques, and art therapy. I learned so much from chatting with her on a video call, and got some good book recommendations too! Thank you, Emily, for sharing your insights with such passion.

Tell me more about your podcast, Brave Me: A Podcast Built for Brave People.

I started it February last year, before the pandemic was in full swing and we kind of just had whispers of it. I was thinking “I want to do something different, that challenges the things that scare the crap out of me but that I can do.” Public speaking scares me, articulating myself really well is challenging for me, so I wanted to do that. So I started off with just a couple really small episodes and then I was kind of absent from it because of all of the chaos in the world, but now I’ve been doing it more consistently and it feels really good, really empowering. I also like tailoring episodes to what I’m searching for to recommend to my clients. I really want to cut out the clutter of “click here, here’s some ads, or here’s a 25-minute mindfulness thing.” I just wanted something quick, easy, accessible for them to use, and then a way to challenge myself as well so I could kind of conceptualize this whole idea of what it was to do some guided meditation and mindfulness practice but also practice using those skills myself and challenging myself. It’s been fun, kind of scary, but I’ve really enjoyed it.

The first couple ones were very basic, just deep breathing and muscle relaxation. I wanted something where someone was guiding the breathing, and where you can hear the breathing more, because I wasn’t finding that from other meditation scripts I was looking for, and I really wanted something that was accessible for people who were trying to practice more of that deep breathing, and I wanted progressive muscle relaxation because I also work with Tourette’s and body-focused repetitive behaviors [BFRBs], to loosen up those muscles when they’re feeling the urge. Those were the first ones I did and then I moved into more guided meditations that had more themes like canoeing down a river or finding gratitude in your home or things like that that helped with grounding exercises and finding some more calming visualizations.

Cool, that sounds great. I find that I’m intimidated by the word “meditation” and that sounds really nice to me. So, sounds like you don’t just treat OCD but OCD and related disorders—how did you decide to focus on that?

I was seeing a lot of folks who had OCD and they’d say, “Oh, I also do this other thing that I haven’t really talked about, and it’s not a big deal, but it bothers me.” I’d say, “Okay, what’s this other thing?” and it would be skin picking or hair pulling, some mild to moderate cases. I did some research on it and I found out how often it happens with folks, where they might have skin picking or hair pulling and OCD and how it was treated in the past like sister disorders and now it’s more like far distant cousins. I kind of went down this path of researching it a bit and I found this really great program from the TLC Foundation for Body-Focused Repetitive Behaviors. [Emily holds up a book by Charles Mansueto, Overcoming Body-Focused Repetitive Behaviors: A Comprehensive Behavioral Treatment for Hair Pulling and Skin Picking.] I did this program with them to learn more about CBT and how it’s used with BFRBs. I found it really fascinating how there’s an overlap with different repetitive behaviors. They’re on different neural circuits, but they’re very similar, and I really liked what these folks wrote about body-focused repetitive behaviors. It was very individualized and targeted therapy and cut out the muck, just here’s the solution, let’s work toward it and tailor it to your needs and put it into play and adapt as needed.

You said they used to be more like sisters and now they’re more like distant cousins. So basically with more research they’ve figured out they’re not that similar and then how are they treated differently? It’s CBT for both of them?

Yeah, it is CBT for both of them, and mindfulness is a big part for both of them. With BFRBs it hits more of the sensory aspects of things, so our bodies are looking for sensory information throughout the day and with BFRBs it’s trying to meet that need but it’s getting into pulling hair and feeling with the fingertips or the scalp. There’s some kind of sensory information our bodies are looking for. How that differs from OCD is it’s on more of a pleasure circuit versus an anxiety circuit.

Interesting! I’m learning new things all the time. How long have you been in practice, and how long have you been treating OCD? Did you always know you would treat OCD? What was your inspiration?

Did I always know I would treat it? No, I originally went to grad school for art therapy, but I always knew I wanted to stay within the cognitive behavioral therapy realm of things, but I felt like something was missing, the self-expression aspect of it. I thought art therapy would be where I wanted to go, but a series of life events happened as it often does, and I was living in Wisconsin after grad school with my son and my partner and we decided to move back to Minnesota. I was living in Minnesota for a while and Rogers opened up in Eden Prairie, which was close to where I was living, and I’d worked with Rogers before when I lived in Milwaukee, and I thought, that’s interesting, I want to hear more about that. I went in for an interview and thought this could work. I launched the IOP [intensive outpatient program] there in the child and adolescent unit, and that was a whole adventure, but I got to learn more about ERP because I worked with therapists who were exposure therapists. I loved how effective it was, I loved how I could sit with people in their fears and watch them become more empowered, and I really loved how person-centered it was and how it hit not only the behaviors and thinking but also their feelings and the essence of themselves and getting back to their values. After that I was like, yes, this is where I was supposed to be. It was a really cool moment.

What misconceptions do people have about OCD? And how do you think we can work to fix it?

Everybody has intrusive thoughts, and I think that’s something that people are like “What? Yeah, I guess I do have weird thoughts, and I never really thought about that before.” I did a lot of work with parents before the pandemic and I had to take sort of a side break from it because of my own kids’ needs, but I used to do a lot of treating parents and how to support their kids and I remember working with parents and saying, “Just pay attention to your thoughts, when you have that weird feeling when you’re cutting carrots or something and you’re like, ‘What if I cut my finger off?'” Later they would say, “Emily, you know that thing about my thoughts? I totally had some weird stuff like what if the oven blows up, what if I put the cat in the fridge?” Yeah, I know! You just don’t have OCD so your brain doesn’t get stuck on it.

So you’re saying that it’s a big misconception that only people with OCD have intrusive thoughts?

Yep. The other thing is I would say anybody can have OCD. It doesn’t matter who you are, it doesn’t matter where you’re from, it doesn’t matter how you were brought up, it doesn’t matter who your parents were, you can have OCD. And you can live a fulfilling life with OCD.

What would you tell someone who says that their goal is to never have an intrusive thought again, knowing that they will?

I like to be really open, honest, and transparent about the information I know from the research that’s available, so with a kid I’d say it’s not so much about not having scary thoughts, it’s more about what perspective you can take with the scary thoughts, how you can work with the scary thoughts. Scary thoughts happen. I think that goes back to everybody has intrusive thoughts. One of my favorite books I just got, because I’m starting to do more parent-oriented OCD, maternal and paternal stuff, is Good Moms Have Scary Thoughts. The fun thing about it is it’s just about two moms sitting on a bench and one’s like “Oh, I should breastfeed, why don’t I breastfeed, because formula is poisonous?” and the other mom is like “I’m breastfeeding, what am I doing, I’m exhausted, am I a bad mom?” What you’re thinking about in the moment can change just from taking a different perspective on it.

You mentioned that before the pandemic you were doing coaching with parents. Can you say more about that and why it’s important to get the family involved?

I currently do more coaching with partners. I think it’s really important to find somebody who will work with accommodations and reassurance with parents and also train parents on okay, yeah, your kid is doing these things, but it’s not so much from your kid, it’s from this OCD thing in their brain. So if you were working with your child on insulin control, it wouldn’t be so much about your child and their inability to manage their sugar levels, it’s more that they have this disorder that they need help with. I really liked working with parents and identifying, like, let’s watch language and track when you are accommodating. There can be a lot of “Oh, I do this for them all the time,” so I say let’s monitor that and see what “all the time” really looks like. I help them use tools like validation or urge surfing techniques or keeping up with the pep talk, like “You can do this, I know it’s tough but let’s work on it together, what kind of exposures can we set up for each other?” So I really did enjoy that and I really enjoy that for partners as well and working through a lot of the turmoil that can accompany having OCD and having a partner. Sometimes one partner ends up being more in charge of the day-to-day things or scheduling changes in the household because of OCD.

What is urge surfing?

I use it a lot more for kids; I don’t use it much for adults. It’s like, “Okay, let’s wait and see what happens.” I got it from The Complete OCD Workbook. I use it with kids. I really love this book because I feel like it’s just a quick down and dirty book about what OCD is all about in the outpatient world, but urge surfing for kids can help them be like “there’s a scary thing that’s going to happen” and sometimes kids know what it is and sometimes not so much, but let’s wait and see, let’s sit together and wait and see what happens.

I love using humor in my practice. You know, it is a serious thing and it is very distressing, but finding that place where you can laugh with your partner, parents, people around you, about these quirky things that happen—I feel like it just helps you work with your OCD. I also like to take OCD as it’s a part of your brain still, it’s kind of like that aunt you never really want to invite to the holidays but you do anyway because they’re your aunt. I like to treat it more like that. There’s some quirky things you can laugh about but they’re still here with us.

I was just thinking about that—you know how people without OCD will make a joke, and it’s like, “It’s not even a good OCD joke, though.” There are funny things about OCD—I laugh about OCD all the time, but sometimes people who don’t have it don’t know how to joke about it so they think I’m offended, and it’s like, “I’m actually not, though, it’s not offensive, it’s just not a very good one.” It’s better when it almost makes you mad—

Ugh, I’m so mad because it’s true!

I would love to work with you if I were in that space right now because it helps so much to have levity. It seems weird to have one thing that’s the serious thing, don’t laugh about this.

Right, you know, I think it’s just part of being human. Even the deepest, darkest parts of ourselves we have to find some humor in it, not so much as a defense mechanism but it’s kind of like that judgmental/nonjudgmental stance or radical acceptance. Yeah, this is daunting, this is scary, but I’m not gonna give it more power by being afraid of it and thinking I have to treat it so factual and observational. It’s more like, yeah, it is scary and it’s scaring the shit out of a lot of people.

I think treating it super seriously like that, for me, would make it worse because then I would overanalyze it and think, “This is a dark, serious topic, why is this happening?” Where, like, that’s fricking hilarious that that’s what you thought, that’s where your brain took you? I know there are times when you shouldn’t laugh, but when you can get to that moment it’s such a powerful thing. When you can think, “No, that was truly ridiculous that I ever thought that.”

That’s where I really like to bring in the art therapy side of things, too, with thought defusion strategies. Saying it out loud, it can just sound so ridiculous, and whether it’s a singsong voice or you’re using your Oprah voice or just saying it louder with your friend, you’re transferring their power. It’s still you confronting OCD, but you’re taking away the power it thinks it has over you.

I love that. What other art therapy techniques would you use for OCD?

Cross-stitching for BFRBs can be really empowering because it’s a tactile thing; it’s also super sensual. I ran a women’s group for women and women-identified individuals with OCD and did some thought defusion, self-care, and creating a profile for what your OCD looks like: when it is strong/loud, what its weaknesses were, what it attacked, where it lived, and making a comic book or a graphic novel page out of it.

If you could give someone with OCD just one piece of advice, what would it be?

I had two that suddenly came to mind. The first one is that you’re not alone and the second was that you have what you need inside you.

February 3, 2021

Demystifying Postpartum OCD on Instagram: Windsor Flynn

Windsor Flynn

Windsor FlynnConsidering how much Windsor Flynn’s Instagram posts make me laugh, it may be surprising what they’re usually about: obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). Windsor shares advice on how to deal with intrusive thoughts and compulsions, drawing on her own experiences with postpartum OCD to make you really believe you can face this too. Thank you, Windsor, for everything you do—and for being here today!

You’ve shared your struggles with postpartum OCD after the birth of your son. Did you know anything about OCD before the onset of your symptoms?

I had only heard of OCD in the same way most everyone has. I imagined people spinning in circles and counting loudly and generally behaving in a very obvious manner. The symptoms I was experiencing were definitely not on my radar as OCD.

How did you realize what you were experiencing was OCD?

After searching for postpartum mood symptoms I came across a checklist for PPOCD/Anxiety and I related to nearly all of the symptoms listed.

You have two children now. How are you doing? Did you experience any symptoms after the birth of your daughter?

I’m doing well, considering the general anxiety and frustration that comes with living through COVID. Other than that I think my mental health is pretty solid. I say that because I know that I have the support of my therapist as I need it, and we have our regular appointments. After Olena was born I had intrusive thoughts about thinking she was the devil and I was looking for any signs that I might actually believe she was the devil. I was constantly checking to see if I was experiencing psychosis. This became pretty intense and for a while I felt like I would feel safer if I was in a hospital. I didn’t know that I was experiencing an OCD relapse but I was.

Windsor and her son, Lucas

Windsor and her son, LucasWhat would you tell a new mom who’s worried she’s going to hurt her baby?

I would tell her that becoming a parent comes with so many fears. Some are rational and some are not. I would encourage her to seek support from family and professionals, not because it is dangerous to fear that, but because the fears can be managed in a healthy way.

I’m new to Instagram—it took me a while to get my first pair of skinny jeans, too—and your posts crack me up! Of course they’re not just funny, they also help people feel less alone in their struggles with OCD. How did you decide to share your experiences (a) on Instagram and (b) with humor?

I was inspired to share my experience with OCD after realizing that I would never wish this on my worst enemy. The worst part of it all was the shame I felt and this belief that I was the only person who could be so awful to imagine these horrific scenarios. The humor part wasn’t planned, it’s just the way I am. I’m glad that the humor has resonated with people because I was scared it would be taken the wrong way. But after all, we need levity to get through something as dark as OCD can be.

Windsor and her daughter, Olena

Windsor and her daughter, OlenaSometimes I find it easier to tell strangers about my OCD than the people closest to me. What has your experience been like?

Oh yea, I totally feel you on that. My husband and immediate family know about my OCD but I don’t talk to them about the specifics. If they want to they can always read my Instagram posts. I feel like telling people puts pressure on them to say something reassuring and we know what happens when we go down that route.

If you could offer people with OCD just one piece of advice, what would it be?

You don’t need to live this way. It is very possible to feel better and to learn to stop ruminating and to stop compulsions. OCD doesn’t have to be this thing that always causes you distress. Also, don’t try to fix yourself with toxic positivity or healthy food. Nothing beats OCD better than ERP therapy.

January 28, 2021

Relying on Community: Hannah Zidansek

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) itself is serious, but that doesn’t mean spreading awareness and clearing up misconceptions about it has to be. Enter Hannah Zidansek, who manages to explain what OCD is really like with humor and a skill I don’t have myself—making videos people actually want to watch. Hannah is an advocate for the International OCD Foundation and a welcome presence at OCD Conferences. Thank you, Hannah, for sharing your story to help others!

How long have you had OCD? How did you realize that what you were experiencing was OCD?

I have had OCD since I was 12 years old, which has been more than half of my life now. I remember the day it started. I was in class, sitting in first-period math, and it was as if a switch was flipped in my brain. Suddenly, I was overwhelmed with obsessive thoughts and anxiety. I remember thinking to myself, “Are these things really happening or is this all in my head? Why would I be thinking about these things if they were not real?” I did not know that I was experiencing OCD until I was 13. I spent a year trying to make sense of what I was going through while trying to keep it a secret, which caused difficulty for everyone in my life. One night I broke down and shared with my parents the constant thoughts that were in my head and how I could not make them stop. Thankfully, my mom understood enough about OCD to get me help. A week later I was sitting in a psychiatrist’s office receiving my diagnosis.

Once you knew it was OCD how did you go about addressing it?

I was diagnosed sooner than the average person, but I did not receive proper treatment, exposure response prevention (ERP) therapy, for a few years after that. There were no resources available in my area at the time. I cycled through a few different therapists who hardly understood the disorder let alone the gold-standard treatment for it. My psychiatrist put me on medication and I was always in some sort of talk therapy, which failed to do anything but put a bandaid on things until I was severe enough to warrant intensive treatment. When I was 16, I spent five months at Rogers Memorial Hospital in the residential program for adolescents and teens with OCD. This is where I was first introduced to ERP and it saved my life.

Can you tell us about some of your symptoms?

My OCD is predominantly health and contamination based. I have two other diagnoses, emetophobia and panic disorder with agoraphobia, that are comorbid with my OCD. They all feed into each other. I have dealt with religious OCD and scrupulosity as well. My symptoms involve obsessions about my health, specifically my digestive system, and worries of contaminating myself with something that could lead me to get sick. This has involved an avoidance of a wide range of potential dangers such as certain colors, numbers, sounds, fragrances, and textures. My rituals have included avoidance, counting, tapping, obsessive praying, checking, reassurance seeking, information seeking, hand washing, and extraordinary efforts to decontaminate. I have overcome most of my rituals but still struggle with avoidance and reassurance seeking.

You have made some of the best stigma-busting videos about OCD. How has it felt to share your story?

Thank you! Sharing my story has felt natural to me and essential for my recovery. I have spent so much time isolated with my own brain and feeling disconnected from the outside world. Talking about it with others, especially people who experience the same kind of afflictions, feels like the ultimate act of reclaiming myself and conquering shame. I have found that speaking about my struggles keeps me motivated and facilitates me in making sense of the bizarre ways I have suffered with this beast. It feels like purpose.

When I’ve told people I have OCD I’ve gotten a mix of reactions, ranging from polite but curious to downright rude. What has your experience been like? When people say something uninformed about OCD how do you respond?

I have been called crazy. I have been given terrible unsolicited advice. When I receive an appropriate reaction, it feels like a treat. I shouldn’t be surprised by decency, but I still am! My least favorite comment has to be “Me too! I’m so OCD about XYZ.” I understand the sentiment; the intention is usually to make you feel “normal.” But the minimization and misunderstanding of OCD has consequences. It is the reason so many OCD sufferers do not seek treatment. When I tell someone I have OCD, I am telling them that I deal with something painful, something that has been destructive to my life. I try to view these misguided comments as an opportunity to educate. Instead of responding with rage, which I believe to be justified, I do my best to inform them of the realities of OCD. My hope is that they will never again mistake their normal, healthy, and universally human idiosyncrasies with a debilitating mental illness.

If you could offer just one piece of advice with others who have OCD, what would it be?

Find the community. Make friends with people who have OCD. My biggest breakthroughs in my recovery have been because of the friendships I have made through the OCD community. This is an isolating disorder that has the potential to fill you up with self-shame and self-stigma. I cannot overstate the healing power of connecting with other humans who know how heavy this disorder is to carry, because they’ve carried it too. The OCD community is full of incredibly compassionate souls with empathy that is hard to match. Though our fights are individualized, there is a feeling of togetherness that makes you realize you are never alone in this.

December 23, 2020

Virtual Therapy for OCD: Allison Solomon

Allison at OCD Gamechangers

Allison at OCD GamechangersThis has been the year of virtual everything: happy hours and weddings, work and school, and, of course, therapy. Many therapists had to unexpectedly make a switch to 100 percent virtual sessions, but Allison Solomon has been offering virtual care for several years. Always wondered if virtual therapy was right for you? Read on to learn more about it, and how Dr. Solomon came to treat obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and related disorders. Welcome, Allison!

How long have you treated OCD? Why did you decide to focus on OCD and other anxiety disorders?

I remember treating my first case of OCD as a graduate student about 25 years ago. My doctoral dissertation was focused on the evidence-based treatment of childhood OCD. Early in my career I treated a wide range of issues but narrowed my focus to specializing in the treatment of OCD and related disorders for the past 15 years. My practice now is solely focused on treating OCD, anxiety disorders (such as panic, phobias, social anxiety), BFRBs (trichotillomania, dermatillomania), and tic disorders with children, adolescents, and adults.

I decided to focus on these issues for several reasons. The first reason is more personal. My younger sister started showing symptoms of OCD, separation anxiety, and Tourette syndrome at around five years old. Her symptoms worsened over the next ten years and my family struggled along with her. I remember my parents desperately trying to find doctors who could help her, and it was very difficult, especially in the 1980s. She was put on extremely heavy-duty medications and she experienced many serious side effects. Not one therapist or physician ever mentioned exposure and response prevention (ERP). I remember feeling horrified, helpless, and frustrated. She was teased by other children for her tics and rituals; even some teachers at school made rude comments. I spent a lot of time standing up to bullies and protecting her, even while I didn’t understand her seemingly illogical fears and rituals. As a family we tried our best to come up with strategies to help her. Over time, her tics dramatically reduced (which tends to happen with some children as they age). In her teens, she finally found a therapist who knew how to treat OCD and anxiety. We worked together as a family and she got dramatically better. I had always had an interest in psychology, and after watching my sister make so much progress, I decided that being a therapist would be my career path in life. She is now a very successful adult and manages her OCD quite well most of the time.

As I progressed through graduate school and my internship and postdoctoral fellowship, I worked in many different settings with very diverse populations. I saw how often OCD was misdiagnosed, misunderstood, and mistreated across all these settings and people from all ages and backgrounds. It was both frustrating and enlightening to see that the struggles my family encountered in trying to get help was something that was happening all over the world.

I have always been fascinated with the human brain and how it impacts our thoughts, feelings, and behaviors. OCD is horrific yet fascinating in the ways it takes deeply held values and creates terrifying scenarios to violate our sense of safety and identity.

Allison’s practice

Allison’s practiceDue to the pandemic, a lot of therapists have transitioned from in-person to virtual therapy, but your sessions are always virtual. Why did you decide to open the Virtual Center for Anxiety & OCD?

That’s a great question. For years I was in private practice in Arizona. I did therapy in my office, as well as in patients’ homes and in the community (due to the need for ERP to be delivered in settings where it would be most effective). I carried a large caseload and had a long wait-list, mostly due to the lack of OCD experts in the state. It was very difficult to juggle out-of-office appointments and travel time with my in-office patients. I began doing virtual sessions from my office and my patients and I were encouraged with the results.

In the fall of 2016, I relocated to New York for my husband’s job. I referred my patients to other therapists, but most decided to continue on with me virtually. I planned on setting up an office in New York as well as continuing virtually with my Arizona patients. Unfortunately, my husband had an emergency back surgery that led to him having to stay in the hospital for months. I was able to continue caring for my patients as well as my husband by keeping my entire practice virtual. It was then that I saw how virtual therapy benefited my patients as well as (and often better than) in-person treatment.

Allison at the OCD Conference

Allison at the OCD ConferenceNeedless to say, 2020 has been a doozy. Have you noticed an increase in people seeking treatment who haven’t experienced anxiety before? Do you think they could learn from some tenets of OCD treatment?

Another great question! I have a few thoughts about this. First, my general observations are that almost everyone has been experiencing heightened stress and anxiety this year at a more significant level than I have seen since the terrorist attacks on September 11. I have definitely noticed an increase in people seeking treatment who have never seen a therapist or sought help for anxiety or OCD-related issues. In my experience, these individuals tend to have had a history of anxiety or OCD in the past but may not have recognized it until they experienced a much higher level of distress or were stable until this year, leading them to seek help. Also, there has been much more conversation and content about stress, self-care, coping, and seeking help on many media outlets, which seems to have prompted validation of emotional distress and normalization of seeking treatment.

To answer your second question, yes! I may be biased, but I think every single person in the world could benefit and learn from tenets of OCD and anxiety treatment. Every human being has experienced fear, anxiety, and doubt. Every human being, at some point in their lives, has engaged in avoidance or ineffective coping behavior. Ultimately, the tenets of OCD treatment I find the most applicable to everyone are: 1. Learning about the brain and how we experience fear and anxiety as well as learning about the cycle of avoidance and other unhelpful responses to these emotions. 2. Understanding the role of acceptance of our discomfort and distress and how it can ultimately lead to a decrease in suffering and a more effective way of dealing with challenges. 3. Developing a plan for increasing exposure to unhelpful thoughts, feelings, and situations while decreasing avoidance and behaviors that reinforce fear is incredibly powerful. 4. Thoughts are not facts and feelings are not facts! 5. Self-compassion is essential when facing life’s challenges. 6. Uncertainty is a fact of life. Nothing is certain except for this fact! Making space for living with uncertainty is the path to freedom!

Allison and her husband

Allison and her husbandWhat’s a common question or misconception people have about virtual OCD treatment?

The most common misconception about virtual OCD and anxiety treatment (or treatment in general) is that it is not as effective as in-person treatment, that it will be difficult to connect with a therapist, and that you cannot do exposures virtually. Another misconception is that virtual therapy for children or adolescents is not possible or helpful.

This year has bombarded us with so many awful and painful experiences. One incredibly positive thing I have witnessed this year has been a massive decrease in the misconception (by sufferers, family members, and therapists) that virtual therapy is not as effective as traditional treatment. Many of us have now been well-versed in meetings, school, or social get-togethers over video conferencing and I believe this has contributed to a decrease in the belief that it is impossible to meaningfully connect with others this way. Another big “win” for virtual mental health is that many insurance companies are now covering virtual treatment and reimbursing at the same rates.

I have found there are so many advantages of virtual therapy for OCD over exclusively in-person therapy. There are definitely disadvantages for both the therapist and client. There are also situations in which ongoing virtual treatment might be contraindicated. All things considered, I believe the advantages far outweigh the disadvantages, and I am so grateful I am able to connect with clients near and far and provide much needed evidence-based treatment.

Speaking of misconceptions, what do you consider the biggest misconception people have about OCD? What can we do to combat it?

There are so many misconceptions about OCD and people with OCD that I am having a hard time picking just one. This may not be the biggest misconception, but it is one that I hear and see often: The idea that if a sufferer recognizes their obsessions and compulsions as irrational, it means that they can and should “just stop” them. People with OCD are some of the bravest, strongest, and kindest people I know. The idea that you can “just stop” is so harmful and invalidating. If that was possible, OCD would not be a problem and we would all be thrilled. Not only is this not true, but it leads to more shame, feelings of inadequacy, and hopelessness and prevents many from seeking treatment because of the fear that this message will be reinforced.

Charlie and Tanner!

Charlie and Tanner!If you could share just one piece of advice with someone who has OCD, what would it be?