Alison Dotson's Blog, page 2

April 5, 2023

Psychology Onions: Peter Scobas

I love to laugh, even about the hard stuff in life. And my guest today, Peter Scobas, loves to joke and make people laugh—even about the hard stuff in life! Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) can wreak so much havoc, make us question who we are and where we’re going, but it can help if we’re able to make light of it now and then. Read on to see how Peter takes OCD down a peg. Thank you, Peter!

You’ve described your newsletter Psychology Onions as “If The Onion and Psychology Today had a baby.” What inspired you to start it?

I suppose I started Psychology Onions because I didn’t feel like I could relate to the OCD/mental health content out there. I’m kind of a curmudgeon when it comes to the positive, sincere, good-hearted “you got this!” approach to mental health. I’m a bit of a grump with most things and I have a tough time being serious, especially when I’m feeling emotionally cornered. So Psychology Onions is a newsletter for me—for current me, but also for 13-year-old me and 18-year-old me and 25-year-old me.

It wasn’t until several years after diagnosis that I was able to laugh about my OCD, and I still remember how freeing it was. Somehow I didn’t know I could laugh about something that had nearly ended my life. When did you realize you could joke about OCD? How does joking about it help you?

I think that joking about my OCD is kind of like the cherry on top with respect to my ERP (exposure and response prevention) therapy. It’s like—you don’t need the cherry, but if you like cherries and you feel like cherries help you treat your mental illness, maybe start eating your sundaes with cherries. My psychologist has really hammered home the idea that OCD is this absurd bully who needs to be confronted and called out. He’s taught me that when I’m feeling overwhelmed with my embarrassing, disgusting thoughts and irrational, shameful compulsions, I need to try and scoff at my OCD and have this “is that all you got?” reaction, this “are you kidding me, that’s rich!” response—and I think joking about it is kind of an extension of that.

What advice do you have for folks with OCD who just can’t bring themselves to laugh about it—yet?

You’re doomed. No, I’m kidding. It’s a journey. But also I don’t think you necessarily need to laugh about your OCD. It kinda goes back to my cherries point from before. For me personally, I don’t like actual cherries, only metaphorical ones.

I’d love to hear about your experience with OCD. When were you diagnosed, and how did you realize what you’d been going through might be OCD?

I struggled with obsessive thoughts/irrational compulsions since I was about 13, I first met with a psychologist when I was 18, and I finally got adequate OCD treatment when I was 26. I’m probably about 29 now, depending on when you’re reading this. OCD is this weirdly misunderstood disorder, even among doctors, so I struggled for years with misdiagnoses and ineffective treatments and medications. I think what really slipped me up was the “Pure-O” stuff—the mental obsessions and the mental compulsions. My OCD’s “content areas” have changed from time to time, but some of the bigger ones have been things like needing to drive around to check that I didn’t kill someone or run someone over, obsessing that I’m a pervert/pedophile, washing my mouth/lips/face/body with bleach or rubbing alcohol if I have a “wrong” or “sinful” thought, being paranoid I’m going to prison, cleaning my body until I bleed type of stuff. When I was 26, my wife just happened to read some article about real-event OCD and was like “ohhhhhhhh, mannnnnnn that’s what you have.”

Once you did know it was OCD, how did you go about treating it?

Drinking alcohol and taking sleeping pills at first, then generalized despair, before finally settling on a combination of ERP, a few medications, and a very loving/patient wife. But kidding aside, my wife was a real trouper for sticking with me and fighting for me and refusing to let me fail. I’ll never tell her this to her face but she’s the nicest, funniest, most beautiful woman I ever met. Finding the right psychologist took time, finding the right medication took time, and I think I’m in a really good spot at the moment, but I also acknowledge that OCD is a constant, chronic battle and life isn’t always linear.

Did you tell loved ones about your diagnosis? Do you think opening up then made it easier to advocate for OCD awareness now?

My best friends know, my mom and sister know, my dad kinda knows. Being more open about OCD to some of my family and my friends has definitely helped take a bit of the sting away. OCD thrives in secrecy.

What do you wish people knew about OCD?

I suppose I don’t have many qualms about the average person’s knowledge of OCD. I think it may be a bit ungracious of me to expect my neighbor or my friend or anyone with no OCD experience to understand OCD. I don’t know anything about Lyme disease, or Crohn’s disease, or rickets, or like…99.99 percent of anything medical. I think we should allow people to not have extensive medical or psychiatric knowledge and be okay about it. I dunno. While I do wish everyone had a psychiatrist’s understanding of OCD, I’m not super bummed out that they don’t.

If you could give just one piece of advice to someone with OCD, what would it be?

There’s a quote hanging in the locker room of my favorite NBA basketball team, the San Antonio Spurs. The quote is from a Danish-American journalist and social reformer named Jacob Riis and, pound for pound, it’s my favorite quote of all time. I have part of it tattooed in a regrettable orange, blue, and lime green script on my right forearm. The quote goes, “When nothing seems to help, I go and look at a stonecutter hammering away at his rock perhaps a hundred times without as much as a crack showing in it. Yet at the hundred and first blow it will split in two, and I know it was not that blow that did it, but all that had gone before.” That’s my advice. Be a stonecutter. Keep going. Keep hammering. Persist.

March 21, 2023

Going All In on OCD Advocacy: Tia Wilson

Full-time OCD advocate Tia Wilson is stomping out stigma in nearly everything she does, and she does it with such irresistible humor and creativity you almost forget she’s schooling you on mental health! Thank you, Tia, for sharing your story with us and for giving us hope that life with OCD can be fulfilling and fun.

How long have you had OCD? How did you know what you were experiencing might be OCD?

I have had OCD for as long as I can remember. Symptoms started when I was as young as three when I put myself in timeout due to scrupulosity OCD (or fear of being immoral). From there, symptoms expanded and grew as I did, latching on to every facet of my life. My friends, family, faith, existential existence—everything! I slowly started to notice that my friends weren’t washing their hands as much as me or weren’t anxious to walk home because stepping on the sidewalk might not be perfectly symmetrical. So I got good at hiding the more obvious symptoms and doing a lot of rituals in my head—things like compulsively praying, ruminating, or reassuring myself. These symptoms continued to expand through high school as my compulsions grew more and more dangerous. I knew something was wrong but didn’t know what. Eventually in college things hit an all-time low and I started researching. I stumbled upon a book about OCD and the symptoms were so in alignment I scheduled my first therapy session the very next day with a specialist.

Once you knew you had OCD, did you tell people about it? If so, how did you go about it?

I have always been an extroverted person who can’t keep her mouth shut so my close friends and family knew pretty quick. But the shame was so strong I didn’t want to talk to anyone else about it! In fact, I knew word of my treatment would reach extended family so I emailed them to let them know I would not be answering questions. As I navigated the therapy process I started to realize that I wanted to share and help more people like me. I chose to wait until I left therapy to share my story publicly. It was terrifying! I made a post on social media and the response was so loving and has led to the advocacy platform I have today!

Can you tell us about any of your symptoms?

OCD is characterized by having intrusive thoughts that cause you distress and so you do compulsions to try to escape the consequences of them. For me, these thoughts latched onto everything! My religion, my relationships, anything I valued was fair game for my OCD. They could be violent, disturbing, or just plain scary.

“What if that stranger goes home and hurts themselves because I didn’t say hi?”

“What if I go to hell because I forgot to repent for something?”

“What if an earthquake kills my entire family?”

Because of this I would try to do things to give me comfort or certainty like religious rituals, asking for reassurance, sleeping with an earthquake whistle—anything to feel better. It reached a point where I was no longer really able to take care of myself or leave my house because everything felt too daunting.

I love your videos on Instagram—they’re funny but informative, a perfect mix! What inspired you to start spreading awareness that way?

Through proper treatment I was able to go from clinically severe to subclinical—truly a 180-degree shift! My life was exponentially better and I couldn’t wait to share that with others. I’m a creative and love to find unique ways to speak up for the things I care about so my page has become all about that!

I also find that when making videos funny and relatable it helps people who don’t have OCD not only understand it better but also apply principles of recovery to their own life! Because we all have black and white thinking or get stuck seeking certainty to a degree!

Speaking of videos I love, I love “OCD: We Sink.” I watched it so many times when you first posted it, and it still gets me. Can you tell us a little more about it, and what it means to sink?

That is so kind! I was working with these two filmmakers who wanted to showcase OCD in a unique way. We went through many iterations of script and decided the best way to illustrate OCD as it actually shows up (and not in the stereotypical way it’s presented) was to take a step back and share how the process of recovery can look. To “sink” can be interpreted many different ways but to me it’s all about letting go. Stop resisting the uncertainty of the world, stop trying to figure everything out with absolute certainty, stop trying to control what can’t be controlled. Exposure and response prevention (ERP) therapy (the gold standard therapy for OCD) is all about that.

Why does it matter that people know what OCD really is?

It is so misdiagnosed! When I was thirteen I remember talking to a therapist about my struggles and asking whether it might be OCD (some part of me knew deep down I guess!) and she said “Is your room clean?” And I said “never” and she responded that then it must not be OCD. A huge mischaracterization caused by stereotypes. Understanding OCD as simply a cleaning disorder discounts all the other valid ways it shows up. OCD can grab onto anything. Your newborn baby! Your sex life. Your political ideologies. When we recognize this so many more people are able to get help.

If you could share just one piece of advice with someone who has OCD, what would it be?

You deserve to get better. I truly didn’t believe that until I was on the other side! OCD loves to tell us that we are the exception to the rule. But it gets better and small steps build up over time. You can do it!

March 16, 2023

Treating Scrupulosity and Other “Bad Thoughts”: Jed Siev

I met today’s guest, Jed Siev, PhD, several years ago at an OCD conference—I think Lee Baer introduced us, and as I mention later in the Q&A, I loved Dr. Baer! One of the reasons I loved him was that he was truly and deeply empathetic toward sufferers of “taboo obsessions” (i.e., me) and worked hard to ease the immense pain they can cause. Jed, too, has dedicated so much time to studying these distressing thoughts and how to help people address them. As long as people like Jed exist, we’ll never stop learning about OCD and how people who have it can live richer, fuller lives despite it. Thank you, Jed, for all you do!

As a therapist you treat not only OCD but body dysmorphic disorder (BDD), hoarding, hair pulling and skin picking, and tic disorders. How are these disorders related? Are there treatment methods they have in common?

In DSM-5, all of those except for tic disorders are classified as “Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders.” To varying degrees and with respect to varying factors, there is overlap among them. Some co-occur at higher rates than chance, some share fundamental features, some respond to similar treatment approaches. For example, OCD and BDD are characterized by obsessions and compulsions, and first-line treatments for both are similar (CBT including ERP). It is probably worth noting that some have questioned the validity and utility of this grouping.

Tic disorders are not classified with the others, but behavioral treatments for tic disorders often include techniques that are also part of treatments for body-focused repetitive behaviors (e.g., hair pulling and skin picking) such as habit-reversal training. There are also manifestations of OCD that Charles Mansueto and colleagues have called “Tourettic OCD,” and the diagnostic criteria for OCD actually include an optional specifier to indicate it is “tic-related.”

You’re also an associate professor in the Department of Psychology at Swarthmore College. I’ve often heard from folks who’ve taken psychology courses that OCD was taught for maybe a day or two at most, and the classes barely scratched the surface. With your focus on OCD and related disorders, are you able to delve more deeply into the topic?

For better or for worse, I do, and I joke that my students are a captive audience. In Clinical Psychology (what many institutions call Abnormal Psychology), we spend about a week and a half on OCD and related disorders, but I also end up using many OCD-related examples throughout the semester simply because I have more to draw on from my clinical work. It’s tough because there are so many things to cover in an overview class like that. I also teach a seminar on anxiety disorders, and we spend one week on OCD and another week on “OC spectrum” disorders such as BDD and hoarding.

Do students in your psychology classes come with a fairly good knowledge of what OCD is, or does it seem like most associate it with what we often see portrayed in media, such as excessive hand washing and needing things to be organized a certain way? Have you seen a shift at all over time in how well versed students are in the topic?

I think there’s a lot of variability in terms of how sophisticated the students’ pre-class knowledge is. I’ve had students with OCD or with family members who have OCD in my classes, and when they’ve chosen to tell me about it, I’ve usually been pleasantly surprised to find they’ve received accurate information and quality treatment. Other students have more stereotyped or caricatured impressions of OCD, or simply don’t know much about it at all. I confess that I was probably one of those students when I was an undergraduate.

I hadn’t noticed a shift in the time I’ve been teaching, but I started my first faculty position in 2011, which wasn’t long before more nuanced portrayals of OCD were mainstream (e.g., in Girls).

You trained with one of my favorite people ever, Lee Baer, the author of The Imp of the Mind: Exploring the Silent Epidemic of Obsessive Bad Thoughts. These “bad thoughts” include violent, religious, and sexual obsessions, which Dr. Baer also referred to as taboo obsessions. Why did you decide to focus some of your research on these types of thoughts?

Well first of all, Lee Baer was also one of my favorite people! As I imagine is true of many people, I lucked my way into so much of what I do now. Credit really goes to a series of fortuitous twists and turns.

I went to graduate school to study child anxiety without any interest in OCD. However, I was placed with Jon Grayson for my first treatment practicum, and I finally really understood OCD. I discovered, as well, how rewarding it is to work with folks who can be so severely impaired but for whom treatment can be so effective and life changing. I was hooked.

The following year, I worked with Edna Foa and Jonathan Huppert. We had a steady referral stream from a nearby Ultra-Orthodox Jewish community, and I was able to learn a lot about treating scrupulosity, which in turn got me interested in unacceptable thoughts symptoms more broadly.

Having OCD can make a person feel guilt and shame, and although there’s no obsession or compulsion any of us are particularly proud of, there is another layer of shame and guilt with taboo obsessions. Are there elements of therapy that address some of that guilt and shame, or steps a person can take to ease some of it?

You’re certainly right about the extra layer of shame and guilt. The way I often think about it is that taboo obsessions are extra distressing because people experience them as a threat to their sense of self—who they are—not just what might happen. I actually have been thinking (and reading and listening) a lot recently about how to address shame and guilt, and I’m not sure I have it fully worked out. But here are some of the pieces.

Cognitive techniques can be helpful to explore moral judgments and decision-making, and to clarify one’s actual beliefs—as opposed to fears—about the meaning of taboo obsessions. Are you engaging in emotional reasoning, whereby instead of feeling guilt because of your beliefs and judgments, you infer from your sense of guilt that something must be wrong? (A former graduate student of mine had some data showing that symptoms of scrupulosity were associated with that sort of reasoning.) There are also a number of questions that can help clarify sources and/or targets of shame. For example, are there double standards in how you judge yourself versus others? Is the shame about what you imagine others would think of you?

I think the therapeutic relationship can also be an antidote to shame. It can be powerful to reveal your most shameful thoughts, images, and urges to someone and discover that they feel empathy and care, and don’t seem to view you differently—that they respond to the “shameful” obsessions as matter-of-factly as to the relatively boring ones.

When I first met with an OCD specialist after struggling with sexual and religious obsessions for over a decade, I was afraid I wouldn’t be able to get the words out and tell him what I’d been experiencing. I was afraid he’d have no choice but to report me to the authorities! Luckily he knew these thoughts were OCD symptoms and he barely batted an eye, but there have been some instances where a misguided therapist has reported a person who’s voiced some of their harm obsessions. First, what would you tell a person who wants professional help but is afraid this might happen to them, and second, how can we make sure all therapists, regardless of their specialty, know enough about OCD that they don’t mistake it for something dangerous?

I remember hearing you talk about that experience at a conference a number of years ago. So powerful, and an example of at least part of what I meant about the therapeutic relationship.

Sadly, I have also met people who have received harmful information or reactions from misguided therapists, including being told that obsessional fears were actually true-but-unwanted desires, let alone actually being reported. Unfortunately, I don’t think this is completely unrealistic, so I think it would be disingenuous or at least glib to just say that one should always simply “tolerate the uncertainty” and take the risk. Rather, I think someone needs to make an honest assessment of how rational the fear is in their particular situation, so they can take a more calculated risk. Find a therapist or support person who understands OCD. Anyone who specializes in OCD will have many experiences with people who have obsessions at least as horrible as yours. I imagine that someone reading this blog knows something about how to find qualified resources for OCD, including treatment providers, but the IOCDF is a great place to start.

I wish I had a good answer for how to ensure that therapists won’t mistake a benign but scary obsession with something dangerous. I’m all ears!

If you could offer just one piece of advice to someone with OCD, what would it be?

Treatment works! Yes, it is hard work, and yes, it may seem intimidating. Find someone who can help you work at a pace you can tolerate and in a way that respects your non-OCD beliefs and values (e.g., in a case of religious scrupulosity). You really truly can live a “normal” life, unburdened in your everyday experiences from the grip of OCD. And through organizations like the IOCDF, there is a wonderful community of people who have been through it and are eager to support you.

January 23, 2023

Navigating Faith and OCD: Katie O’Dunne

Help me welcome the wonderful Katie O’Dunne to this week’s Q&A! As you’ll soon learn from Katie herself, she is a dedicated advocate for OCD awareness and how the disorder can affect—and be affected by—a person’s faith. Read more from Katie!

When were you diagnosed with OCD, and how did you first realize it might explain what you’d been experiencing?

Even in my earliest memories, I was consumed by terrifying worries and did everything in my power to alleviate my deepest fears. For instance, I can remember being absolutely plagued by guilt following the death of my aunt to cancer, as I worried that it was somehow the fault of my 8-year-old self. Soon after, I worried constantly that I was somehow a dangerous person. Intrusive thoughts and images flooded my mind at night, as I called my parents into my room to confess every scary thought in order to seek reassurance that I was not a dangerous monster. As I grew older, my fears changed and morphed into every single area that was important to me. By college, I was afraid to go to sleep out of fear that I had left the stove on or the door unlocked. And by graduate school, I was terrified I called individuals derogatory names or wrote horrific things in birthday cards before blocking it out. I managed by checking the stove, taking pictures of the locks, or calling friends to make sure I hadn’t somehow caused harm.

In my early 20s, I learned that I was experiencing symptoms of OCD. I was taking psychology courses and started to recognize some of the symptoms, but I knew very little about the presentation of OCD (and even less about the treatment!). At this point, I was in seminary and doubting absolutely everything…from whether or not I left the candles lit in the chapel in seminary to whether or not I was secretly a horrible monster. And yet, I feared documentation of an official diagnosis would negatively impact my pursuit of ordination. So, I pushed it down and continued to cope by seeking reassurance wherever I could find it, which only made me sicker.

Before you knew you had OCD, what did you think it was? Did your symptoms line up with what you’d been hearing about it?

My symptoms definitely didn’t line up with what I was hearing about, which was that OCD was some “cute quirk.” Ugh…it’s not! While I suspected I had OCD, I definitely didn’t attribute many of my intrusive thoughts to the disorder. By the time I moved into my first role in ministry as a school chaplain, my head was spinning with every worry possible: What if I said something mean to a student in class and forgot about it? What if I kicked the child on crutches? What if I snap and stab someone? What if I’m secretly a murderer and just blocked it out? What if I’m just pretending to be a moral minister and am secretly a horrible person? What if God actually hates me? The entire day swirled with these thoughts, as I supported 2,700 students from different faith traditions through losses, interfaith education, and their own mental health challenges. I felt like I was living two lives: the calm, peaceful, joyful chaplain supporting students…and the life inside my head telling me I deserved absolutely nothing. At my lowest point, I was prepared to call the police on myself to confess to crimes I didn’t commit—just in case they were somehow my fault or I had blocked them out.

And yet, I was one of the fortunate individuals who found evidence-based treatment at this lowest point, after nearly 15 years of symptoms. Engaging in exposure and response prevention (ERP) seemed to oppose every single thing I had done throughout my life. Rather than trying to convince myself I was not, in fact, a sinful, bad, murderous person, the treatment encouraged me to do just the opposite. I had to learn to accept uncertainty in all of its forms. ERP was terrifying for me…but it saved my life.

As a former school chaplain, your faith has played a huge role in your life. How has it affected your experiences with OCD, if at all?

My role in school chaplaincy is honestly what led me to begin telling my story. I spent my entire treatment journey in secret: hiding every obsession and compulsion from those around me. I was terrified that if someone knew the school chaplain was seeking mental health treatment, they would no longer respect me as an ordained minister or as a leader. This couldn’t have been further from the truth.

After witnessing many of my students navigate their own mental health struggles—fearful of being open in their faith communities—I felt like I had a responsibility to share my story. I wanted my students from all faith backgrounds (Jewish, Christian, Muslim, Sikh, Jain, Buddhist, humanist, and beyond) to know that they could authentically engage in their faith practices while seeking evidence-based treatments. To my surprise, as soon as I began speaking up, families started reaching out to me more (not less!). Almost daily, I heard from families who wanted help authentically talking to their priest, rabbi, or imam about their child’s mental health struggles.

This was a profound moment of faith for me, where I deeply believe the Divine created beauty out of brokenness in my life. Ultimately, this journey of faith led me to help others with what I like to call the trinity of recovery, as they have faith in their treatment, their beautiful traditions, and themselves all at the same time. I deeply believe that once I learned to embrace my own struggles, receive treatment, and become open about my identity as a minister navigating OCD, a space for individuals from all faiths to share their individual struggles with me was organically (or perhaps divinely!) created.

After seven years in school chaplaincy, you’ve now committed to helping individuals navigating faith and OCD full-time. How did you come to that decision? What does that look like for you?

When I began to advocate publicly with the International OCD Foundation, I learned about a subtype of OCD involving an individual’s faith tradition: religious scrupulosity. OCD always latches onto the things most significant to the sufferer, and in this case, an individual’s personal faith becomes OCD’s target. For individuals navigating religious scrupulosity as a subtype of OCD, repetitively and rigidly engaging in faith practices can become debilitating, rather than life-giving. In 2020, I was blessed to begin working with an amazing team of humans at the IOCDF to create Faith & OCD initiatives through an interdisciplinary task force, special interest advocacy groups, annual conferences, and a full web resource.

In doing this work, I began receiving requests to use my knowledge of OCD and interfaith chaplaincy background to help separate faith from OCD in religious scrupulosity cases. I began doing this on a volunteer basis, but the passion and need continued to grow. With the encouragement and support of the IOCDF, beginning in May 2022, I moved out of school chaplaincy to found Faith & Mental Health Integrative Services, an organization helping individuals with OCD and related disorders live into their faith traditions in value-driven ways as they navigate evidence-based treatment.” Tangibly, I consult alongside clinicians on religious scrupulosity cases around the world, lead international scrupulosity support groups, train clinicians in interfaith literacy for ERP, and train faith leaders in the understanding of scrupulosity. My entire life is that of an interfaith clinical chaplain specializing in OCD, which is fulfilling beyond anything I could have possibly imagined! My biggest joy is working on care teams to help individuals across faith traditions reconnect with their traditions in value-driven ways not dictated by their OCD.

I am also working on my Doctor of Ministry in Integrative Chaplaincy at Vanderbilt, where I am focusing my research on reimagining ERP as a spiritual practice across faith traditions. Ultimately, I hope to use this work and the model I’m developing to train other faith leaders as clinical chaplains specializing in OCD/religious scrupulosity to work alongside clinicians.

And yet, my biggest call is to inspire and empower others to use their voices within their own houses of worship. I am filled with joy when I see individuals across faith traditions sharing their stories. For anyone who would like to get involved in advocacy/work around faith and OCD or running 50 ultramarathons in 50 states for OCD (another topic for another day!) reach out to me anytime.

You were recently featured in the first commercials about OCD! What was your role, and what was the goal of the commercials?

This was truly the biggest joy! I loved working with my amazing fiance Ethan Smith and with Biohaven throughout the process. I worked on two separate commercials with the opportunity to see both from start to finish, as Ethan developed the entire creative vision before writing/directing each commercial! In one, we literally show our lives flashing by while OCD research remains stagnant. And in the other, we seek to transform uncertainty from terrifying what if’s to beautiful possibilities. Ultimately, the goal is to raise awareness for OCD while sharing information about an amazing clinical trial seeking to develop the first new medication for OCD since the 1990s. Participating in each commercial, sharing my story, and directing the testimonials was beautiful beyond my wildest dreams!

If you could give just one piece of advice to someone with OCD, what would it be?

Ahh! There is so much I would like to share, but I’ll leave it with this: I would like to remind everyone that it’s time to be more afraid of giving up your life to OCD than all of the scary stuff coming true. Because regardless of what OCD says, you deserve a big, beautiful, awesome, amazing life.

January 10, 2023

Using Creativity to Treat OCD: Krista Reed

Krista Reed

Krista ReedObsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) can feel so dark. It can make a person feel lonely, afraid, isolated, ashamed, guilty, and just plain bad! Therapist Krista Reed breaks through some of that darkness with her vibrant and colorful personality as well as the refreshing perspective that therapy is still effective even when there’s an element of fun included. Thank you, Krista, for sharing your story with us!

You belong to a group of very special people: OCD therapists who also have OCD! How did you decide you wanted to treat the disorder you’d been struggling with?

Originally when I graduated in 2007, I wanted to focus on infant mental health. I was very passionate about working with young children and was working on an infant mental health endorsement and becoming a registered play therapist when OCD took hold of my career. I began having fears of molesting my young clients, who several of them were in therapy for sexual abuse. I went to someone in my city who reported on his website that he specialized in OCD. The session was hands down one of the most humiliating experiences in my life. I shared with him the fear of molesting my young clients and he then proceeded to do a risk assessment on me and then reassured me that I was “harmless” and “nothing was wrong.” I recall leaving his office feeling terrified that he would report me, I would lose my license to practice, my husband would leave me, and I would be abandoned by everyone. I lived for years struggling with my OCD and having little to no trust in therapists, even though I was one, and I believed that this was just going to be my life. Eventually, I heard about exposure and response prevention (EPR) therapy. Unfortunately, I could not find anyone locally who treated it. Also, it was hard to find a therapist who I already did not know. In 2016, I learned about ERP and while learning how to utilize this intervention to clients, I began learning how to do exposures myself. The more I got into ERP, also incorporating mindfulness, I noticed that I was in fact getting better. I just feel in love with this work and knew that this was something that I wanted to do throughout my career.

In addition to treating OCD you also treat body-focused repetitive behaviors (BFRBs) and body dysmorphic disorder (BDD). We both know there are a ton of misconceptions about what OCD is—are there any misconceptions about BFRBs or BDD you’d like to clear up?

Body-focused repetitive behaviors and body dysmorphic disorder are both not obsessive-compulsive disorder. Very frequently, a client will step into my office with an OCD diagnosis when they may only pull their hair (trichotillomania) or spend countless hours in front of the mirror camouflaging their “perceived flawed” area (this is a common compulsion with BDD). These disorders may fall under the “Obsessive Compulsive and Other Related Disorders” chapter in the DSM [Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders], yet they are different. Both BFRBs and BDD have different treatments than OCD. Just as it can be harmful for a clinician to falsely advertise that they treat OCD, it can also be harmful and shameful for a clinician to attempt to treat BFRBs and BDD without the proper education.

Family food fight

Family food fightYou treat OCD with cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), specifically ERP, but you sometimes supplement that treatment with play and art therapy as well as yoga and mindfulness. How can these techniques all work together to help your clients with OCD?

I am just a big kid who loves to play and be silly! OCD caused me to believe the fear that people would judge me or dislike me because I am playful and silly. I have learned that this is true with so many OCD sufferers. Although exposures can be scary, disgusting, and stressful, I enjoy finding ways that not only incorporate the individual’s values into them, but also finding something that might also be somewhat fun. Yes, that might sound like a contradiction, but hear me out. Adults can make mud pies, run around barefoot outside, lick the cake batter off a mixer, do cartwheels in public, and even play on a playground with their children or relatives. When creativity, artistically or physically, is used, the possibilities are endless for how exposures can be done. I also love to incorporate food. Doing mindful eating with “unsafe” foods can be extremely cathartic and healing for people struggling not only with OCD, but also ARFID [avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder] and emetophobia.

One of my all-time favorite exposures was singing Christmas carols, in public, in the middle of summer. My client had an absolute blast and even went around throughout the week and went to neighbors’ homes to go caroling!

I have OCD, but I also have fears I don’t consider OCD symptoms, like a fear of heights. Would my fear of heights be treated similarly to my OCD symptoms, with gradual exposures?

Absolutely! With OCD the thought that brings distress can occur even when someone is away from the feared/disgusting stimuli whereas with a phobia, the distress primarily occurs when exposed directly with the feared/disgusted stimuli. For example, your fear of heights might not bother you unless you are in an elevated situation. As with OCD, working alongside a professional who is trained to work with phobias is advised, as if an individual is exposed to the fear too soon, they might feel “flooded” and discontinue treatment.

Family Halloween costumes

Family Halloween costumesYour Instagram posts are so fun and inspiring! Where do you get your ideas? Do you have a background in acting or dance? There’s so much creativity at play.

(Blush) Well, thank you! I grew up loving art, music, theater, and simply am blessed with being incredibly right-brained. I went to Kansas State University with a performance scholarship as I wanted to be on Broadway and then eventually movies. I still have a passion for musical theater and try to see as many musicals as possible.

As far as where do I get my ideas, well, I suppose you can thank my OCD for that one! I hid my disorder for years and I found ways using my creativity to mask it. Honestly, I just got fed up masking my authentic self that now I embrace it. I have learned to put myself out there, be colorful, and be seen. OCD never wanted me to be seen and now I am enjoying my life not being OCD’s understudy.

You recently launched a series of 90-second videos called Taboo Tuesdays, which you will post every Tuesday of 2023. Why did you think it was important to focus on taboo obsessions?

I have been treating OCD for nearly six years and constantly see people struggle to enter treatment for the fear of being judged by the one person whose job it is to not judge them. I want to educate anyone who is willing to listen about what “real OCD” is and that taboo obsessions are not only common, they are treatable. I am fed up with comments about OCD sufferers being dangerous, or pedophiles, or simply it is all about “being clean.” The more information we put out there, not just with my “Taboo Tuesdays” but your blog, OCD advocates, podcasts, etc., the closer we are getting to erasing the stigma of this disorder.

What is the ICT OCD Alliance, and why did you found it?

2020 sucked. Obviously. It was one of the most challenging years I have ever had as a clinician. More and more individuals were seeking therapy services than ever. Being one of the few OCD specialists in my area, I was struggling to get people into the office timely. I only knew one other clinician in the state who treated OCD. She and I were both overwhelmed and wanted to support one another. She heard of another clinician who treated OCD and then I found two more! It felt like a dream come true! We started meeting toward the end of 2020 providing support, education, training and OCD resources, and referrals to one another. Then in 2021, I bought the rights to the name “ICT OCD Alliance.” ICT being Wichita, Kansas, and the word “alliance” because we all advocate for the same cause—getting people who have OCD-related disorders the help they deserve without struggling to find therapists through Google and false advertising. Each therapist who is a part of the alliance has been treating OCD for a minimum of one year using evidenced-based treatments. We are simply a group of clinicians, each with their own practice, who support one another and provide grassroots advocacy for our community. We meet twice a month, once for consultations and the other for advocacy and plans of the community (presentations, trainings, podcasts, etc.) Our goal comes down to my own therapy experience: I never want anyone with OCD to ever feel harmed by their clinician. I want every single person with OCD to find someone who can treat them and guide them toward recovery. This past year our group even provided presentations at the Denver IOCDF conference.

If you could share just one piece of advice with someone who has OCD, what would it be?

Actually I would like to share a poem versus advice. Ironically I just wrote this poem today. The poem is a letter to my younger self.

To Who I Was,

Sincerely,

Who I Am

You were little, young, and fragile

Thoughts filled your head; Damnation

You felt alone, weak, and helpless

You were just a child; Desperation

Words never escaped your tongue

The thoughts echo; Alienation

Little girl crying on the swing

To Hell you would go; Devastation

Weird, awkward, and frightened

Frozen in fears; Stagnation

Grey, Black, and Hidden

Transparent rainbow; Imitation

A mixture of future’s chaos

Swarming the mind; Insubordination;

Quiet the tomorrow tornadoes

Breathing restriction; Suffocation

Life’s beauty untouchable

Stuck with Moments; Dissociation

Your hope was never fully buried

Stubborn young girl; Determination

You’re no longer little, young, or fragile.

Thoughts still fill your head; Toleration

You no longer stand alone weak and helpless.

Embracing inner child; Unification

Your memories now occupy rooms

The thoughts muted; Innovation

Little girl flying on the swing

Mindfully present; Transformation

Brave, graceful, and eccentric

Facing the fears; Celebration

Blue, Green, and exposed

Fluorescent rainbow; Imagination

Blending of time’s surprises

Encompass the mind; Collaboration

Waking today’s atmospheric wave

Openly breathing; Intoxication

Enveloping life’s beauty

Unstuck in moments; Participation

Your hope will never be fully buried

Stubborn young girl; Liberation

January 2, 2023

New OCD Twin Cities President: William Schultz

Meet the new president of OCD Twin Cities! I’ve served in the role for the last nine years, and after a series of changes in my life it’s time for someone else to take over. That someone else is the very accomplished and well-suited local therapist William Schultz. Not only does William treat OCD with a passion for helping his clients lead a life not ruled by OCD, he has lived with the disorder himself and understands firsthand how scary it can be. Let’s hear from William!

You’re an OCD therapist in the Twin Cities area. Why did you decide to focus on OCD?

I feel like it’s a combination of at least two things: First, it’s the area of mental health that I know the most about, so it seemed natural to focus my services in that area. And, a closely related second reason, is that OCD is the mental disorder I lived through. And, based on many client reports, it seems that my having lived through OCD very much helps me understand and support others currently struggling with OCD in their healing process.

How long did you have OCD before you were diagnosed, and how did you realize what you were going through might be OCD?

My OCD began in 2007 but I didn’t realize it was OCD until 2012. I realized this after I began graduate school in clinical psychology. I was reading about anxiety disorders, came across the OCD section, and instantly thought: “That’s me!”

You’re taking over—for me!—as president of OCD Twin Cities, the local affiliate of the International OCD Foundation. What do you hope to accomplish?

For me, much of what I hope to accomplish will be to evolve after consultations with you, past, present, and future board members, and other members of the Twin Cities OCD community. If I had to point to just my own thoughts and priorities, those would include: Doing our best to help those who don’t realize they’re experiencing OCD learn that they aren’t “going crazy” or a terrible person but, instead, someone suffering from a very challenging mental disorder.

Let’s say someone with OCD approaches you and says, “I don’t want OCD to rule my life anymore, but I’ve heard the exposures in ERP can be really hard and scary.” What would you tell them?

Oh. I feel like I could write pages and pages about this. In fact, I’m about 100,000 words into my memoir of my own experience with OCD, where I do my best to communicate my thoughts and feelings about this and related questions. Nevertheless, if I had to be concise, I think I’d say something like: It’s true that exposures are challenging and scary. And it’s also true that no one in the world can 100 percent guarantee your fears won’t come true. However, it’s also true that OCD has taken an enormous amount from you already. And we know from the research that OCD rarely goes away on its own. And so if you don’t participate in ERP (or some other form of therapy), it’s likely you’ll have OCD for the rest of your life. For me, that—a vision of the future where I have OCD for the rest of my life—was the scariest thing.

So I say: If I’ve got to risk something bad happening to me, I’d prefer to risk my (extremely unlikely) OCD-related fears happening rather than risk obsessing and compulsively behaving, day by day, until my time is up.

What do you wish people knew about OCD, whether they have it or don’t, whether they’re clients or other therapists?

Haha…so many things! Here’s a couple for a start: First, OCD often latches on to things we care about deeply. That’s one of the reasons it hurts so bad: OCD constantly tells us a story where the things we care about most are destroyed, or the things we don’t want to happen most end up happening. One way I’ve tried to describe living with OCD is it’s like being cooked alive. Each day can feel like your body is on fire, with the OCD constantly bombarding your mind with scary thoughts, images, and stories.

Second, many people with OCD have a lot of shame around their OCD. For example, my largest OCD theme centered on the intrusive thought that I might be bit by a rabid bat and not realize it. Since I was afraid I would be bit by a rabid bat and not realize it, I was constantly scanning my environment for signs of a bat. Since I constantly scanned my environment, I often saw objects or items on the ground. Which then triggered the thought, “That might be a bat, and that was near you, so it might have bit you without you knowing.” This, in turn, motivated the compulsive behavior to go carefully check the item or take a picture of the item. So, to illustrate what I mean by shame, imagine going back in time to when my OCD was very sever. I’m walking in a parking lot of a gas station and I see an item on the ground. I have an intrusive thought, “That could be a bat.” So now I need to go verify it’s not a bat. But I can’t just give it a quick glance, because then I’ll have the intrusive thought “Well it didn’t look like a bat, but are you sure you correctly saw it? Maybe it looked like a piece of garbage but was actually a bat? Or maybe it was a piece of garbage but there was a bat underneath it?” So I’d have to really get close to the object and spend a good amount of time looking at it. Now imagine that you’re also at the gas station and you see me doing this. You might wonder, “What the hell is that guy doing?” If someone had asked me (which did happen a few times), I felt tremendous shame around being honest. I didn’t feel I could say “Oh, well, I’m carefully checking this piece of trash on the ground to verify it’s a piece of trash and not a rabid bat that bit me without me knowing.” I, like many with OCD, have some sense that my fears are unrealistic and my compulsive behaviors very strange. But the “what if” of OCD can easily push that aside. So many of us with OCD find ourselves in a tough spot where, on the one hand, we really feel like we might be at risk of something terrible happening unless we compulsively behave, and, on the other hand, we feel like our thoughts are “ridiculous” (a word I don’t endorse but, in the past, said myself and hear my clients say all the time) but feel we “have to” compulsively behave anyway.

If you could share just one piece of advice with someone who has OCD, what would it be?

You don’t have to be trapped inside of OCD forever. Find an OCD specialist that feels like a good match for you and do your best to collaborate with that person in your healing process.

December 19, 2022

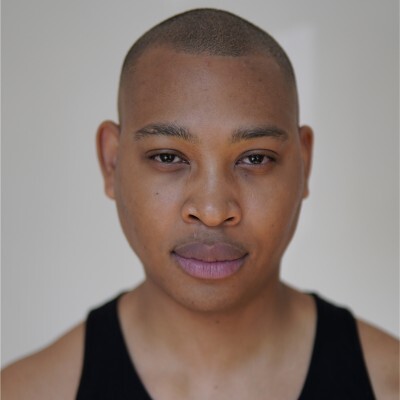

Speaking Out to Destigmatize OCD: Shaun Flores

After Shaun Flores was diagnosed with OCD, he knew he had to share his story to help others—and he has not stopped since! He didn’t see other Black men speaking about their struggles with mental illness, but instead of giving in to stigma and the fear of being judged he has gone full steam ahead, vowing to infuse the OCD community with more diversity. Shaun explains this beautifully himself, so I’ll turn it over to him—thank you, Shaun!

Can you tell us a little of your OCD story? How long did you experience symptoms before you were diagnosed, and when were you diagnosed?

I experienced symptoms for around three or four years—I had the idea that I had a sexually transmitted infection. No matter what I did, I couldn’t get that obsessive idea out of my head. At the worst, I paid for a same-day test to prove I had no infection. That thought migrated to the idea that I had HIV!

The next couple of years I had a dream where I woke up believing I was gay; I threw up because of the anxiety and I couldn’t stop seeking evidence to prove I was gay. I lived with it for years.

The moment that made me realize something was wrong, I had a thought about sexual assault that scared the life out of me. I avoided all my female friends; I didn’t want to be around any females in case I did something. I hated how my mind was.

The final OCD breakdown was when the image of suicide popped into my head. I panicked, called all my friends and told them I wanted to die. The next couple of days I was horrifically depressed. My existence felt like a burden.

On Saturday, June 4, I couldn’t take it anymore. I wanted to know what was going on in my head. I sought help. I searched through the internet and found no answers. I self-diagnosed me with everything under the sun. I found a therapist online called the anxiety whisperer, Emma Garrick. I begged for a call, and she answered, and I poured out crying wanting to know I wasn’t going to hurt anyone. She immediately knew it was OCD.

Since then, we have been doing exposures and I have got my life back. I still have rough days, but for the most part, I am far better.

In an interview you did with Channel 4 you said there have been no Black people at OCD events you’ve attended because Black people don’t speak about OCD. This may be a bigger question than you can fully answer here, but can you say more about why that is? And how did you summon the courage to talk about your experience with OCD when you didn’t see other Black men doing the same?

One day I woke up and said to myself, “Fuck being depressed, I am going to change the world.” I went downstairs and decided to open Google Docs, where I began writing my story. I wanted to tell my story to help others to know they weren’t alone. Writing has been a cathartic experience shedding the skin that OCD enveloped me in.

I already felt ashamed of the thoughts I was having, what could be worse? People will have an opinion of me regardless; I might as well give them the full story so they can form a truer opinion. Either way, their opinion does not stop me from losing sleep.

I released my first story on The Book of Man. I was so nervous, and I wanted them to take the word “rape” out in fear women would be scared. Then I stopped myself; I was avoiding it (a compulsion). I shared it via Instagram and so many people told me they had OCD, mainly Black people. I was shocked! This gave me the fuel I needed to keep burning.

Since then, I have written over fifteen articles—The Metro, INews, Treat My OCD, Black Minds Matter UK, Anxiety UK, Disability Expo, MQ Mental Health Research, Kindred magazine, The Book of Man, The Model Cloud magazine, Beyond Equality, Models of Diversity, London News, Made of Millions, and Orchard OCD—and I have appeared on The OCD Stories podcast, Happiful Magazine podcast, and All the Hard Things podcast.

I have realized yes, the OCD community is a heavily white space, with barely any ethnic minorities, yet OCD does not discriminate. As a young Black man there is already grave shame about speaking about our mental health; it takes someone to make the change. I wanted to be the change I wanted to see. I saw no one Black speak about OCD; I want that to change for others who were previously in my position.

We need more people to share their platforms and give space to ethnic minorities—it literally saves lives. To this day I still have so many people reaching out to me thanking me for telling my story and they felt seen and heard. I will always do my best to speak up and give a voice to the voiceless and give hope to the hopeless. I no longer want to be the only Black guy in Britain who speaks about OCD.

Channel 4 was a watershed moment that made me realize this advocacy and activism is needed in the community and on mainstream conversations. When I spoke, the room fell deafening silent, you could feel the tension. People were being educated, but most importantly I spoke a language people understood. I did not try to overcomplicate what OCD was and my journey. I have found there is a dire need for authenticity and realness because people often won’t speak about their struggles. People keep conversations limited to their highlights, but the highest of highs sometimes do not balance out the lowest of lows.

Courage is not the absence of fear; it is simply using fear to propel me forward toward my aims and goals. A hero uses fear to push him to save and help people whereas a villain uses fear to hurt and harm people. One is for love, and one is for hate; I learned to use fear to help me love the world better and align myself further with my purpose to leave the world in a better place than I found it.

Growing up as a Black man has not been the easiest; however, this is never something I would change. The struggle made me stronger, and without it I would not be half of the character I am today. I enjoy my culture, my heritage, and my background; I just know there is so much to change, the community needs change, and my community has given so much to me. I must give back. I am indebted to the Black community and the wider mental health community and in particular widening discourse within the OCD community.

What would you tell someone who wants to share their OCD story but is afraid of the possible repercussions? What if their goal is to tell their loved ones, not to spread awareness?

First, your fears are valid and come from a sensible place. Society remains not ready to have such conversations at this time. Do not tell your story unless you are willing to face the positives and negatives that come with it. When speaking about my story my mum told me, “Shaun, be careful who sees it as they might not give you a job.” I recognized my mum’s fear comes from a place where she fears the worst; I rather hope for the best and be in spaces where I am understood, and people are willing to listen.

This is such a valid question—the road of advocacy/activism is not for everyone. However, guess what! Telling your family is a form of advocacy and activism. Often, we have this idea hundreds of people must be changed, changing your immediate circle has ripple effects that trickle down over time.

Informing your family, loved ones, your immediate circle is a huge achievement within itself because it takes courage to tell your story. A story shared is a burden halved. Educating your loved ones ultimately can be a huge recovery in taking back your life from OCD.

Whatever you choose you are making change. And that is enough. You are enough.

What do you wish people who don’t have OCD knew about the disorder?

OCD is not a joke; OCD is not an adjective. OCD is not something to be desired. OCD is not to be sought after. You do not want OCD; it takes a lot of mental energy to live with OCD. I implore you to educate yourself as to what OCD is. Using OCD in such casual meaningless ways saying, “I am so OCD” doesn’t put into account the torture OCD can cause and does cause to many people’s lives.

If you could give just one piece of advice to someone with OCD, what would it be?

I can’t give one piece of advice, I want to give several pieces of advice or mere suggestions that have helped me. Never give up; the best project you will ever work on is yourself. I am currently on the NHS trial for OCD where we are testing out the power of “magic mushrooms” on OCD symptoms. It is in fact strangely a great time for us living with OCD; there are more possible treatments coming out. More alternatives and science may feel like it is moving slow, but it is moving fast.

Being of service has helped me come out of the depression OCD left me in and I am aiming to deliver a TEDx talk on OCD; I strongly believe this could change the game for us with OCD. I have plans in abundance. My next plan is to finish my life coach qualification, then I will train to become a therapist.

My private messages are open, I am more than happy to talk to anyone. I will always make time for us with OCD or any mental health issues. You are not defined by your OCD.

Find your why. Your existence is needed, wanted and I love you.

He who has a why can endure any suffering.

December 11, 2022

Facing What’s Hard About OCD: Jenna Overbaugh

Getting treatment—the right treatment—for OCD ranks really high (okay, let’s say it’s number one) on the list of how to take charge of the disorder and live your life according to your values. What’s helped me a lot, too, is simply knowing there are therapists who care about us and go above and beyond to help us feel supported. Jenna Overbaugh is one of those therapists. She’ll get her message of hope to you somehow, whether it’s on Instagram, through her newsletter, on her podcast “All the Hard Things,” or through treatment sessions. Let’s learn more about Jenna!

You’re a therapist for NOCD, meaning you can see clients in an online session instead of in person. How did you decide to work with NOCD? What do you consider the benefits of online therapy?

I decided to work for NOCD during COVID once I realized that there would be an increased need for services during the pandemic. I love that they provide ERP in a way that’s accessible and more affordable than traditional routes of therapy. I loved the training they provided for incoming clinicians and wanted to be part of their mission. There are tons of benefits to online therapy including greater accessibility and also the ability to do exposures from home, which are sometimes where one’s biggest triggers take place. It also allows therapists to see people from a larger area rather than just those who can commute easily to their office.

How did you decide to focus on treating OCD?

I’ve always wanted to work with people who have OCD and anxiety because I grew up as an anxious child. My earliest memories were about being anxious—in school, before school, before talking to someone new. But I always knew that I wanted to challenge myself and go for it, so to speak. When I learned that this was an actual treatment intervention for OCD and anxiety during my Introduction to Psych course in college, I knew it was for me and I started to research it as much as I could.

What do you consider the most common misconception about OCD?

To me the greatest misconception about OCD is that it has to do with cleanliness, germs, or a desire to have things be perfect. It’s so much more than that. I wish people knew that it has the potential to be an extremely debilitating disorder and it’s so much more than what we typically hear people talking about. The taboo thoughts and the shameful images and urges are the ones that no one talks about but we need to be talking more about.

Let’s say a client says, “You can’t possibly help me—I have the worst type of OCD ever, and I don’t think there are any practical exposures for it.” How would you respond?

If someone said that to me I would say that there are always practical exposures for any kind of anxiety or obsessions. Are you avoiding? Are you ritualizing—whether that’s mental or behavioral or both? Then there are opportunities for exposures. The only purpose of an exposure is to put someone in a situation so they can practice not giving in to rituals. So if you’re avoiding, if you’re doing rituals—there are opportunities for exposures and therefore the opportunity to teach your brain new information.

I love your Instagram posts! They’re relatable and funny, and so many are really touching—I get the feeling that not only do you understand OCD, you care a lot about folks who have it. What made you decide to advocate for OCD awareness on that platform?

Thank you! I love doing it. It’s a way to be creative in a field that otherwise feels pretty structured and scientific. I’ve always thought I was pretty creative, I always loved art and especially digital art. I used to make my own websites all the time, I especially love teaching people and I feel like I’m pretty decent at public speaking—so social media came naturally to me. It started out just as fun and I promised myself I would never put too much pressure on myself. I still only ever just have fun with it and try to measure my success based on how much fun I’m having—rather than number of followers, etc.

Speaking of Instagram posts I love, I want to thank you for “How to Do Exposures Without a Therapist.” Even with therapy options like NOCD there are still barriers to treatment for a lot of people, and I hate the idea that people who can’t get therapy might think there’s simply no hope for them. Can you tell us why you wrote that post, and why you prefaced it with “Hi please don’t @ me because you think doing exposures is dangerous without the guidance and supervision of a trained therapist”?

When I made the post a few months ago, 95 percent of people loved it and were so appreciative of the practical tips I provided. Some people, however, came back saying that my suggestion was “dangerous” suggesting that people cannot be trusted or should not be given the feedback to do their own exposures without the supervision and guidance of a therapist. My thought is that, when they’re given ample amount of tools and education and empowerment—like I provide on social and on my podcast—that certainly is better than doing nothing, or continuing to give into OCD by ritualizing and making OCD worse at every turn. I know so many people don’t have access to a therapist but are desperate to try something on their own. I believe I provide (and other therapists too) provide so many awesome resources for free that they can take a post I made like the one you’re referencing and make that just one of the many things they try to implement to try to do something to mess with OCD’s pattern.

If you could offer just one piece of advice to someone with OCD, what would it be?

I would encourage them to do the opposite of what OCD wants them to do. For the most part this will be the best decision for your OCD recovery journey. Also to think of OCD as the doubt disorder—it is the tolerance of uncertainty. You don’t have a cleaning problem, you don’t have a germs problem, you don’t have a fear of harming your family problem—you have a problem tolerating uncertainty and doubt.

December 6, 2022

Thriving in Relationships When You Have OCD: Amy Mariaskin

Help me welcome the amazing Amy Mariaskin! When our beagles were both 15.5 years old we introduced them to each other on a Zoom call—they didn’t seem to know what was going on, but the point is that we tried to foster a connection, and that’s what Amy is all about. Whether she’s working with clients at her Nashville OCD practice, sharing tips in her new book, Thriving in Relationships When You Have OCD: How to Keep Obsessions and Compulsions from Sabotaging Love, Friendships, and Family Connections, or speaking at a conference, Amy leads with compassion and the belief that we can love our lives even with OCD, and she wants to help make that a reality.

Not only are you an OCD therapist at Nashville OCD & Anxiety Treatment Center, you founded the center! This brings up so many questions. For starters, why did you choose to focus on OCD and anxiety, and what led you to opening NOATC?

Like many others in this field, I have personal experience with OCD. Despite developing symptoms in early childhood, I wasn’t diagnosed until I was in my early 20s and studying clinical psychology in a PhD program. I was floored by how much relief I got just from getting a diagnosis. I switched my focus in school and decided to devote my career to helping others with OCD find early intervention and effective care.

My graduate program was tailored more toward research than therapy, but after working with my first client with OCD, I was hooked on being a therapist. It seemed like the perfect combination of science and art and afforded me the opportunity to work with brilliant clients and families. What could be better? I began seeing clients part-time in 2011 in a tiny, poorly lit office, and within six months I had left my other full-time job to be in private practice five days a week! It was clear how much the Nashville community needed specialty care. After a stint as a clinical director at Rogers Behavioral Health Nashville, I wanted to return to providing direct therapy with clients, but I loved working with colleagues. My solution was to open up the NOATC in June 2018. While the first year was a lot of work, late nights, and tears, I feel like we’ve built something really special for Tennessee over the past four and a half years. I’m so honored and privileged to work alongside my awesome colleagues. They make me a better person.

Let’s say someone approaches you and says, “I have OCD but I’ve been told there’s no cure. Should I try therapy anyway?”

Oh, yes—this is such a common question. When people ask it, there’s usually something else lurking underneath it. There might be an underlying fear that if therapy fails to help, it will “prove” to the person that they are truly broken (you’re not!). Or it may be an acknowledgment that therapy is financially and emotionally taxing, and the person is evaluating the pros and cons of taking on this work without the promise of an outcome. It could be that the outcome itself is being portrayed as a black or white situation (cured vs. sick) instead of recognizing the gradations in improvement that can affect one’s life.

Therefore, before I rush to provide a resounding YES, I like to help people explore the meaning behind this question. What does cured mean? What does symptom reduction mean? What if you don’t need total symptom elimination to have a meaningful life? I like to honor people where they are but also acknowledge that if they’ve made it to the therapy room, they are at least therapy-curious, if not completely bought in. Overall, I want to instill hope that therapy can be helpful while empowering people to decide for themselves about how therapy fits into their plan.

You have a new book out, Thriving in Relationships When You Have OCD: How to Keep Obsessions and Compulsions from Sabotaging Love, Friendships, and Family Connections. What an important topic! I think sometimes we focus so much on simply surviving with OCD we forget we also deserve to thrive. What are some tools readers will gain?

It was a deliberate choice to use positive language in the title instead of only talking about how OCD can sabotage us. I wanted for the people with OCD to be centered and to show that we can all thrive above and beyond just managing our symptoms. My goal with this book was to highlight the ways in which OCD can infiltrate our connections with others and how to center our relationship values to create the connections we want. The tools and exercises in the book range from audio clips (like a self-compassion meditation) to structured worksheets (such as one to help track reassurance) to behavioral exercises (like one to increase intimacy). I enjoyed not feeling constrained by any one therapeutic modality. That is, even though all of the strategies are from evidence-based treatments, they are not solely from one treatment method. I had the freedom to write a book the way that I practice with my clients, which is integrative of different techniques.

I hope that people who read this book get the following from it: (1) a sense of validation and connection to others who have struggled with similar things, (2) clarification of their interpersonal goals in different relationships like friendships and partnerships, and (3) tools to reduce the impact of OCD on these relationships. I also tried my best to infuse the book with humor, and even though I feel like some of my best one-liners were removed by the editor, I hope that humor still shines through. Humor is a great way to take the wind out of OCD’s sails and encourages “cognitive defusion,” an acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) term for creating distance between thoughts/emotions and their impact. I wish I could insert an effective joke here to give you an example, but maybe you’ll just have to get the book!

A statement I often see about OCD is that it doesn’t discriminate, and I agree. However, while anyone can get OCD, not everyone has access to effective treatment. How can some barriers to treatment be dismantled?

Financial barriers are probably the biggest one people face. Therapy is expensive, and insurance reimbursement rates are painfully low, discouraging therapists from accepting insurance. If you can’t find someone who has specialty training and takes your insurance, finding clinics that have intern rates is one way to address this. The Open Path Collective is another resource for finding services offered at sliding scale rates. Others may live in geographical areas with few or no trained providers. In some places this has been alleviated by the uptick in virtual therapy services. But depending on licensing laws it can still be near impossible to find care in certain areas of the world. I know that Beyond Borders CBT is working on increasing services across country lines.

Finally, therapy, like many other healthcare fields, has a checkered past in the United States. Sexual and gender minorities were pathologized for years as having mental disorders, and research in the field of psychology was often limited to white, middle-class people. Even now, there are racial disparities in diagnosis; for example, Black clients are more likely than white ones to be diagnosed with schizophrenia in the presence of the same symptoms. Therefore, in addition to lower access to services, certain marginalized groups may harbor some (understandable) mistrust or hesitancy about therapy. Dismantling these kinds of barriers can involve acknowledging that all of these factors might show up in the therapy room, and addressing them in a sensitive and affirming manner.

You’ve said you have a particular interest in working with LGBTQ+ youth. Tell us more.

Hot take maybe, but I think being a kid is actually really hard. There’s a ton of new information coming at you and a ton of strange stuff happening in your body. My worst years with OCD were all before the age of 18, and I think a lot about how we don’t give kids credit for the work that it takes to get to adulthood. Trying to figure out where you fit in when your sexuality/gender differs from the dominant culture is an additional layer that complicates things. So at the intersection of addressing mental health concerns, navigating childhood, and exploring LGBTQ+ identity, I think there’s a magical place to help support and enrich these young people. Being in Tennessee where there is an active push to silence LGBTQ+ voices, it also seemed important to have this focus so that kids and families would have a safe place to land for therapy.

One topic people with OCD can be hesitant to talk about is how their obsessions and compulsions can interfere with their sex life. I was once terrified I’d have certain intrusive thoughts interfere, and it was easier (but more detrimental) to avoid intimacy. How would a therapist help a client work through an issue like this?

It’s tough because you really might have unwanted thoughts during sex or intimacy. Unfortunately, that part is hard to get rid of. However, there are a few things that people can do to reduce the impact of these thoughts on their experience of sex. One is a shift in mindset about the thoughts themselves: instead of seeing them as meaningful and shameful, you can think of them as merely the mental junk that OCD sometimes spews out. Depending on the content, the thoughts can be very compelling, I know. And they can also make it difficult to stay aroused.

Which brings me to point #2—if you can communicate about your symptoms with your partner(s), it can reduce their impact significantly. This doesn’t necessarily mean telling them all about your thoughts in detail, but it can be the difference between a partner slowing things down to help you stay engaged through these symptoms and them misinterpreting your behavior as a sign of disinterest.

Finally, practice refocusing your attention from the mental to the physical. How does it feel in your body to be touched? What textures, temperatures, smells, and tastes can you find on your partner’s body? OCD likes us to spend a lot of time upstairs in our heads, which can make it hard to feel things, well . . . downstairs. By reframing thoughts, communicating, and practicing body-focused mindfulness, you can experience intimacy regardless of whether or not OCD butts in.

If you could offer just one piece of advice to someone with OCD, what would it be?

Channeling Kimberley Quinlan a bit here, but I would start with encouraging self-compassion. Shame is so common with OCD, and it can make engaging in the hard work of therapy more difficult. So I would encourage everyone to practice holding your thoughts and feelings gently and kindly. And give yourself validation even when it seems hard. You can learn over time to be your own biggest advocate and that often starts with treating yourself well internally.

September 7, 2022

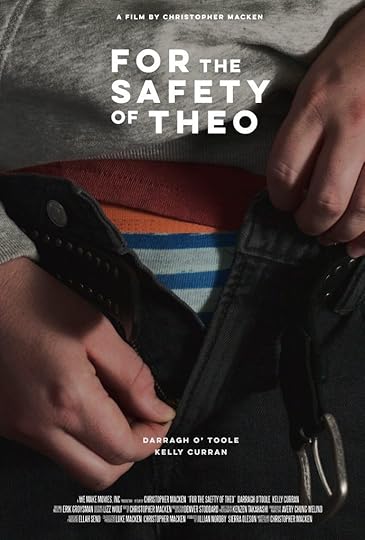

Director of For the Safety of Theo: Christopher Macken

Christopher Macken

Christopher MackenWhen obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) doesn’t manifest as physical compulsions—excessive hand-washing, avoiding cracks in a sidewalk—it can be hard to portray. My guest today has endeavored to make a film that shows some of the anguish of obsessions and mental compulsions. Help me welcome Christopher Macken, director of a short film called For the Safety of Theo. What’s it about, you ask? Well, read on to find out (and to learn more about Christopher)!

You’ve had OCD your whole life, but when did you realize it? What symptoms were you experiencing as a kid that helped you and your parents connect the dots?

I actually wasn’t given the label until I was 28 years old. I know that’s similar to your story, Alison, being diagnosed at 26. I was diagnosed at a time in my life where the compulsions, which once served as survival tactics as a child, started to no longer serve me in my adulthood and I needed help. Putting a name to my compulsive behavior and my distressing thoughts was incredibly freeing.

I look back on my childhood and my OCD was much more physical than it is today. I had more physical tics and rituals that I would perform, but the biggest symptom that followed me into my adult life was reassurance seeking. As a kid, I felt the compulsive need to confess. Whether it was some childhood mischief I had gotten into, or even just simply thought about, I would obsess and panic over it. Relief would only come once I’d confess to my mother or father and get some sort of reassurance that what I did is forgivable and that I am, in fact, still lovable.

Once you knew what you were going through was OCD, how did you go about treating it? What was the plan of action?

I was fortunate enough at the time to have already had a few years in a 12-step program and experience in support groups. So I was able to speak of this diagnosis to kind, supportive fellows and connect with those who could relate or have been through the same thing.

From here, I started reading. The first book I purchased was Brain Lock by Jeffrey M. Schwartz, MD. This helped me learn the science behind what was actually happening within my brain and introduced me to Four Steps: Relabel, Reattribute, Refocus, and Revalue.

Next, I found a therapist who specializes in OCD and laid it all out on the table. This has been the most crucial part of my recovery. Having someone who knows how my brain functions and is able to give me reality checks and help me develop tools to let go and move on from obsessions without acting on them.

I still have a long way to go in my recovery.

What has helped you the most over the years? Was there anything that didn’t work well for you?

OCD therapy and 12-step groups have been my saving grace.

Twelve-step has helped me do some major maintenance on my life and allowed me to make the proper changes in my life and behavior to set myself up for success and not land me in stressful situations that tend to trigger my OCD. It’s also helped me develop a wonderful meditation practice and loving relationship with a higher power.

OCD therapy keeps me current in my recovery and my therapist provides great feedback to my daily struggles, suggesting different methods of responding to my intrusive thoughts.

In terms of things not working, I had trouble with some side effects of an SSRI, so I’m still trying to find my relationship with medication. Being someone who is constantly obsessed with their health and mental being, the idea of medication was doomed from the get-go for me. I’m working on letting go of the historical stigma of antidepressants rooted in my upbringing, and I’m open to exploring different medications down the line if my therapist and I feel like it’s a good idea.

You’ve said your fear of germs and hypochondria affected your relationships. Can you say more about that?