David Mutti Clark's Blog

February 2, 2022

Amending America

“All the ills of democracy can be cured by more democracy.” –Al Smith

American democracy has been hijacked by big money and special interests. Paralyzed and polarized, our democracy and people are dying of despair.

Here’s a proposal to take our country back. To return power to the people. To revive and reinvigorate our country by amending our Constitution, curing our catatonia with an infusion of pure democracy.

The proposal: Create an option to amend the Constitution by popular referendum. This provision would allow any American citizen to propose an amendment to the Constitution by popular referendum.

Today, in our era of polarized politics, it’s is virtually impossible to amend the Constitution— even when large majorities of Americans are demanding change. Article V states that an amendment may be proposed either by the Congress with a two-thirds majority vote in both the House of Representatives and the Senate or by a constitutional convention called for by two-thirds of the State legislatures. In order to be approved, either method requires ratification by three-fourths of the States (38 of 50 States).

Article V needs to amended now. If we are to survive as a democracy, if we are to thrive as a people, we need to give ourselves the capacity to reinvent our Constitution as needed– to be nimble and agile enough to respond to the aspirations and priorities of the People.

So let’s allow any American citizen to propose an amendment to the Constitution by popular referendum. To qualify for being placed on the national ballot, a petition for the referendum must be signed by 10% of all eligible voters. To be ratified, the proposed amendment must receive a super majority of all votes (60%). Additionally, 60% of eligible voters must have voted in the national referendum for its proposed amendment to become effective.

Imagine the impact. It could revive and reinvigorate, enable us to Constitutionally address—

Voting Rights

Campaign Finance Reform

Anti-Corruption

Democracy Reform

Climate Justice

Reproductive Rights

By amending America we have the chance to defeat despair, to reduce the influence of big money and special interests, and to offer a belief that our Constitution and legislative processes offer an opportunity to improve life for all Americans.

This amendment makes our Constitution more responsive, nimble, quick, and improvisational. It reflects our American character of optimism and innovation. And it could get our American Mojo goin’ once again. It’s been a long time.

February 1, 2022

Reclaiming Our American Mojo

“All the ills of democracy can be cured by more democracy.” —Al Smith

American democracy has been hijacked by big money and special interests. Paralyzed and polarized, our democracy and people are dying of despair.

Here’s a proposal to take our country back. To return power to the people. To revive and reinvigorate our country by amending our Constitution, curing our catatonia with an infusion of pure democracy.

The Constitution's first three words– “We the People”– emphasize that the government exists to serve its citizens through their elected representatives. The People are paramount. Representative democracy’s purpose is to implement the will of the people.

But our representative democracy is dysfunctional. The will of the people has been frustrated. The government is gridlocked. Our democracy is dying.

To bust the gridlock, to make our government responsive to the wishes of the people, we should infuse our Constitution with a strong dose of direct democracy– pure democracy as it’s sometimes called because power is exercised directly by the people rather than through representatives.

The basis of our political systems is the right of the people to make and to alter their constitutions of government.— George Washington’s Farewell Address (1796)

This proposed amendment has two provisions:

Establishes an option to amend the Constitution by popular referendum. This provision would allow any American citizen to propose an amendment to the Constitution by popular referendum. To qualify for being placed on the national ballot, a petition for the referendum must be signed by 10% of all eligible voters. To be ratified, the proposed amendment must receive a super majority of all votes (60%). Additionally, 60% of eligible voters must have voted in the national referendum for its proposed amendment to become effective.

Currently, Article V provides two ways to propose an amendment to the Constitution, both of which are virtually impossible today in our polarized politics. An amendment may be proposed either by the Congress with a two-thirds majority vote in both the House of Representatives and the Senate or by a constitutional convention called for by two-thirds of the State legislatures. In order to be approved, either method requires ratification by three-fourths of the States (38 of 50 States).

Thomas Jefferson forecasted a need to amend the Constitution on a regular basis. He wrote that we should “. . . provide in our constitution for its revision at stated periods.” “[E]ach generation” should have the “solemn opportunity” to update the constitution “every nineteen or twenty years,” thus allowing it to “be handed on, with periodical repairs, from generation to generation, to the end of time.”

We’re way overdue. The last time the Constitution was amended was in 1992. The Constitution has been amended 27 times, although there have been over 11,000 amendments proposed since 1789.

If we are to survive as a democracy, if we are to thrive as a people, we need to reclaim our American Mojo by remaking our Constitution. So let's give ourselves the capacity to reinvent our Constitution as needed– to be nimble and agile enough to respond to the aspirations and priorities of the People.

Establishes an option to pass and rescind laws by popular referendum. This provision would allow any American citizen to propose a new law, to repeal an existing law, or to amend an existing law by popular referendum. To qualify for being placed on the national ballot, a petition for the referendum must be signed by 5% of all eligible voters. To be ratified, the proposed amendment must receive a simple majority of all votes (51%). Additionally, 50% of eligible voters must have voted in the national referendum for its proposal to become effective.

By amending America we have the chance to defeat despair, to reduce the influence of big money and special interests, and to offer a belief that our Constitution and legislative processes offer an opportunity to improve life for all Americans.

This amendment makes our Constitution more responsive, nimble, quick, and improvisational. It reflects our American character of optimism and innovation. And it could get our Mojo goin’ once again. It’s been a long time.

June 9, 2020

The Poetic Protester: Potawatomi Chief Simon Pokagon Fought Racism with Words

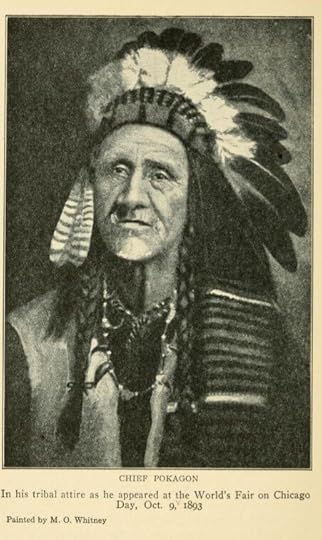

Illustration from Indian sketches: Père Marquette and the Last of the Pottawatomie Chiefs by Cornelia Steketee Hulst.

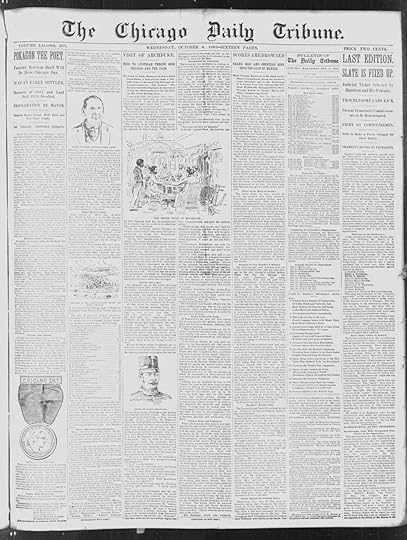

The front page of the Chicago Daily Tribune, October 4, 1893, screamed the news:

POKAGON THE POET.Famous Redskin Bard Will be Here Chicago Day.WAS AN EARLY SETTLER.Massacre of 1812 and Land Deal 1833 Recalled.

Chicago Daily Tribune, Page 1, October 4, 1893.

When Simon Pokagon accepted the invitation to speak at Chicago’s World Columbian Exposition of 1893 he was a 70-year-old legend. Known as the “Indian Longfellow” and called the “Famous Redskin Bard” by the Chicago Daily Tribune, Pokagon was renown for his two visits with Abraham Lincoln at the White House, his writings on Indian affairs in national magazines and his speaking engagements along Chicago’s Gold Coast.

David Dickason sums up Simon Pokagon’s repute:

His contemporary reputation was such that the editor of the Review of Reviews referred to “this distinguished Pottawattomie chieftain” as “one of the most remarkable men of our time. . . His great eloquence, his sagacity, and his wide range of information mark him as a man of exceptional endowments.” (Dickason, David, “Chief Simon Pokagon: ‘The Indian Longfellow,’ ” Indiana Magazine of History, June.)

But what made Simon Pokagon invaluable to the World’s Fair of 1893 was the fact that he was a linchpin between Chicago’s frontier past and its eagerness to be seen as a world-class city of the the future.

As Lisa Cushing Davis explains:

Officials for the city of Chicago were also keen to showcase both progress and civilization. They envisioned the Exposition as an announcement to the world that their city, a mere Indian trading post in 1812 and devastated by fire in 1871, had risen from the ashes to become a world-class metropolis. . . To effectively demonstrate the progress made, however, organizers deemed it necessary to emphasize the events of the past, including the massacre of ‘peaceful’ white settlers by ‘savage’ Indians at Fort Dearborn. (Davis, Lisa Cushing. "Hegemony and Resistance at the World's Columbian Exposition: Simon Pokagon and The Red Man's Rebuke." Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society)

Chicago Tribune, Section 1, August 12, 2012.

Simon Pokagon embodied Chicago’s past, present and future. His father, Potawatomi leader Leopold Pokagon, had embedded his mind with stories about the bloodletting at Fort Dearborn and about the signing of the Chicago Treaty of 1833. Leopold Pikagon was a signatory of this agreement ceding lands on which Chicago was built for three cents an acre.

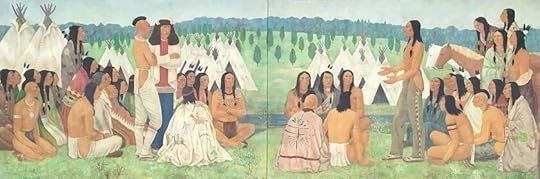

“The Great Indian Council, Chicago - 1833” by Gustaf Dalstrom.

As the special guest of Mayor Carter Harrison, Simon Pokagon was scheduled to ride on a float in the Chicago Day Parade depicting the Fort Dearborn Massacre as well as participate in the reenactment of the Chicago Treaty of 1833. Simon Pokagon had a reputation as an adept politician—being able to nimbly move between the white world and his own Potawatomi people. But how could he maintain his integrity? How could he advocate for his people while participating in a reenactment of a treaty the that gave away Potawatomi land for three cents an acre to the U.S. government—monies he was still trying to recoup for his tribe 60 years later? How could he not appear to be implicitly condoning the white world’s version of the Fort Dearborn battle when riding on a float depicting the ‘massacre’? It seemed to be a challenge that would require all the agility of Harry Houdini.

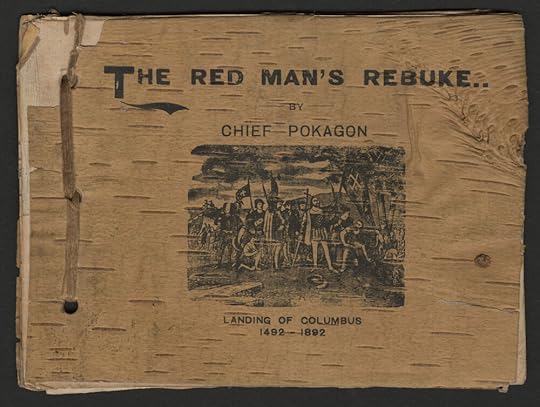

But Simon Pokagon had brought a booklet he had written. It was entitled The Red Man’s Rebuke and was printed on birch bark. Its sixteen pages of text offers a fierce, poetic protest.

Pokagon, Simon. The Red Man's Rebuke. C.H. Engle, publisher, 1893. To read the book, click on the image.

Pokagon wasted no time getting to his rebuke. The first paragraph—

In behalf of my people, the American Indians, I hereby declare to you, the pale-faced race that has usurped our lands and homes, that we have no spirit to celebrate with you the great Columbian Fair now being held in this Chicago city, the wonder of the world.

In the next sixteen pages, Pokagon describes how the pale-faced people destroyed the environment—

. . . the forests of untold centuries were swept away; streams dried up; lakes fell back from their ancient bounds; and all our fathers loved to once gaze upon was destroyed, defaced, or marred, except the sun, moon, and starry skies above, which the Great Spirit in his wisdom, hung beyond their reach.

How wildlife was wantonly hunted—

. . . the beasts of the field and the fowls of the air withered like grass before the flame—were shot for love of power to kill alone, and left to spoil upon the plains.

And what the Europeans brought to America—

They brought among us fatal diseases our fathers knew not of . . . They pressed the sparkling glasses to our lips and said, “Drink and you will be happy.”

Pokagon concludes his treatise by imagining a judgement day. God tells the white man—

I shall forthwith grant these red men of America great power, and delegate them to cast you out of Paradise, and hurl you headlong through its outer gates into the endless abyss beneath—far beyond, where darkness meets with light, there to dwell, and thus shut you out from my presence and the presence of angels and the light of heaven forever, and ever.

In 1897—four years after his appearance at the Chicago World’s Fair and just two years before he died— Pokagon wrote the “Future of the Red Man” concluding with a question—

. . . and generations yet unborn will read the history of the red man of the forest, and inquire “Where are they?”

In 1893, Simon Pokagon captivated Chicago,seventy thousand people came to listen to Red Man’s Bard, the Potawatomi Poet and Chief, speak in the White City on Chicago Day at the World’s Fair of 1893. them with words rather thanwon with words, not weapons. He was an enigma. Not understood by his people or the white man. He said,

Pokagon

May 9, 2020

The Lingering Intimacy of John Steinbeck's Cannery Row

Written and photographed by David Mutti Clark

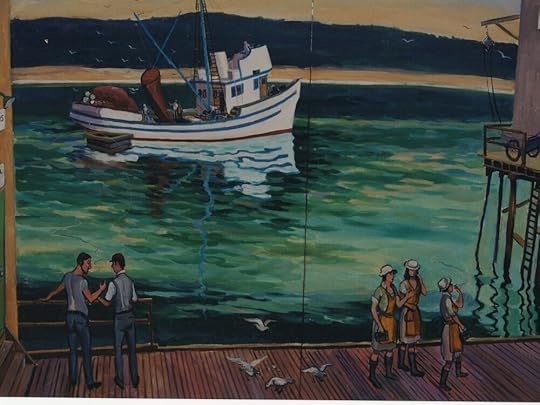

Net Menders by Melissa Lotton. “How can the poem and the stink and the grating noise—the quality of light, the tone, the habit and the dream—be set down alive?”

Cannery Row in Monterey in California is a poem, a stink, a grating noise, a quality of light, a tone, a habit, a nostalgia, a dream. . .

Some writers grab you. And then they swallow you whole. They create characters who become your friends, absorbing and nourishing you the rest of your life. And they give you an intoxicating place that quenches a thirst for intimacy. For me, John Steinbeck was that writer. And Cannery Row was the novel.

The Cutters by Susan Long. “The canneries rumble and rattle and squeak until the last fish is cleaned and cut and cooked and canned. . .”

. . . Cannery Row is the gathered and scattered, tin and iron and rust and splintered wood, chipped pavement and weedy lots and junk heaps, sardine canneries of corrugated iron, laboratories and flop houses. . .

Today, the flop houses, honky-tonks, and whorehouses are long gone. The canneries have been converted to shops and restaurants casting their nets for tourists instead of sardines. But the characters of Cannery Row live on somehow, peeking out from behind the affluence brought by the Monterey Bay Aquarium, art galleries, and boutique hotels.

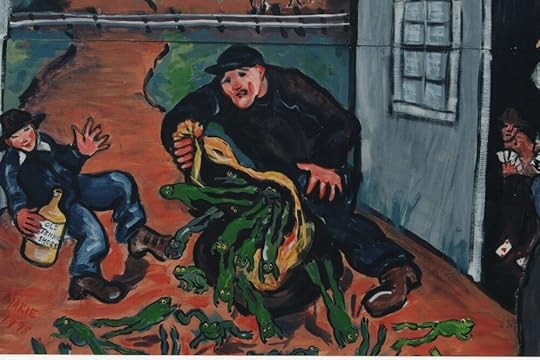

Palace Flop House by Melissa Lotton. “Frogs by the pound, by the fifty pounds. They weren’t counted, but there must have been over six or seven hundred.”

The characters in Cannery Row— Doc Ricketts, Mack and the boys, and Dora and her girls— were outrageous but real, acquaintances of Steinbeck. People he watched and liked.

. . . Its inhabitants are, as the man once said, ‘whores, pimps, gamblers, and sons of bitches,’ by which he meant Everybody. Had the man looked through another peep-hole he might have said: ‘Saints and angels and martyrs and holy men,’ and he would have meant the same thing.

Between the Canneries by Myron Oliver. “. . . the purse-seiners waddle heavily into the bay blowing their whistles.”

Ed “Doc” Ricketts was Steinbeck’s confidant. Ricketts died in 1948. His character debuted in Cannery Row in 1945. And in 2020, Doc still draws a crowd. Until the pandemic, thousands still came to Monterey, walked along the Row and searched for his spirit.

Some lifelong residents say Doc was a teacher, and people came to learn how to dream. But how can a personage in the pages of a novel who has been dead for 75 years teach anything?

Sardine Packers by N.J. Taylor. “Then cannery whistles scream and all over the town men and women scramble into their clothes and come running down to the Row to go to work.”

“Everyone near him was influenced by him, deeply and permanently,” said Steinbeck of Doc. “Some he taught how to think, others how to see or hear. Children on the beach he taught how to look for find beautiful animals in worlds they never had suspected were there at all. He taught everyone without seeming to.”

Alicia Harby DeNoon raucously remembered her lessons from Doc and John. (Alicia lived on the Row from World War II until her death in 2000. I was fortunate to interview her in 1998.) As a young girl, Alicia worked in the canneries cutting and packing sardines, waded in the tide pools where Doc collected his marine specimens and fished off Wharf Number Two with Steinbeck.

Alicia Harby DeNoon of Cannery Row in 1998. A friend of John Steinbeck and Doc Ricketts. She sold antiques, jewelry and nostalgia.

I talked with Alicia in her antique shop across the street from Doc’s former lab. She was a flaming redhead that afternoon. She greeted me with a warm smile and told me stories with the melodious mien of a queen while sitting behind a cluttered desk, watching and waiting on customers, not missing a beat.

Alicia, in fact, had been a queen. In 1963, she was crowned the first out-of-state queen of New Orleans’ Mardi Gras. She pulled out a newspaper from her desk and proved it with a photo showing King Phillip Fillabert taking her hand to lead the grand march.

Alicia paused, then recalled the day Doc died— when his clankity old car was hit by The Del Monte Express, the evening train from San Francisco. Doc was on his way to a steak dinner, but as he turned his sputtering sedan up the hill where the road crossed the Southern Pacific Railroad track, the train slipped around a warehouse and crashed into him. The news spread quickly along the Row, and Alicia rushed to the collision site.

A statue of Edward “Doc” Ricketts stands at the site where he was killed by a train.

“He will not die,” Steinbeck said later. “He haunts the people who knew him. He is always present even in the moments when we feel his loss the most.”

Alicia kept a “Remembrance Room,” a private collection of manuscripts and memorabilia. She showed me a copy of Doc’s last will and testament and a claim on his estate for the value of 300 leopard frogs that Doc wasn’t able to deliver.

As more browsers walked through her shop, Alicia continued telling an anecdote about Doc and John and had everyone laughing. And for a second, we were all inside the covers of Cannery Row. And no one wanted the story to end.

Postscript about the paintings—For over ten years— from 1989 to 2000— smack dab in the middle of Cannery Row, there existed an unsightly construction site. Unsightly because nothing was being built. Lawsuits had stopped all activity. So local artists transformed this this blighted end of the Row into a 400-foot-long mural. Bruce Ariss, a close friend of Steinbeck and Ricketts, provided his original sketches of life on Cannery Row during the sardine canning days. Each artist created their own interpretation of the theme.

The Cannery Row mural attempted to capture the spirit of the Row during its heyday while hiding the mess of a comatose construction site.

May 8, 2020

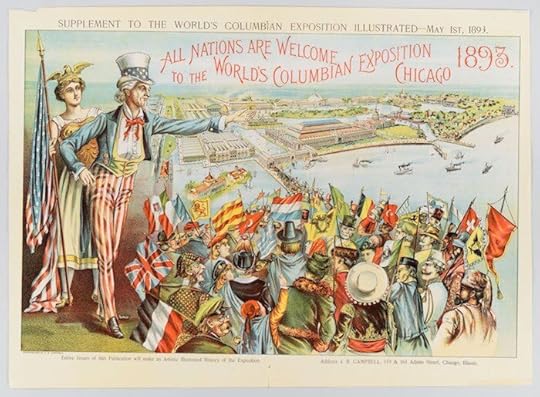

The White City, Chicago's World Columbian Exposition, 1893

Excerpt from The Making of American Aura

Chicago, May 6, 1893

“Lose your story, lose your life,” Catfish told his only son Aura.

The 12-year-old boy’s emerald eyes intensified, luminous against his olive skin and cascading hair. He stood next to his father on a balcony perched high above the White City, a magnificent mirage of neoclassical marble buildings gleaming on the foreshore of Lake Michigan’s infinite horizon. Lagoons and canals interlaced the city. Gondolas glided. Tall ships sailed. The White City scintillated. This was Chicago’s World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893.

Aura clutched the railing to remedy his vertigo. Catfish wrapped an arm around his son’s shoulders and squeezed tight. “Lose your story, lose your life,” he said again.

Aura looked to his father.

Catfish smiled as he reached into his coat pocket and pulled out a flask. “But write your story, son”—he said as he unscrewed the top and took a swig—“but write your story and realize your life.”

May 1, 2020

Chicago's World's Fair, 1893

The Chicago History Museum provides this map of the 1893 fairgrounds to plot your imaginary visit to the world’s fair! Along the way, discover some of the exciting buildings, rides, and amusements. Share your maps and drawings on social media using the hashtag #CHMatHomeFamilies.

Many historians argue that the 20th Century was the American Century. A radiant period of growth, optimism, and creativity. And it was Chicago’s World Columbian Exposition--the Chicago World’s Fair of 1893--that formally proclaimed America’s unbridled belief in itself and its place in the world.

The Fair attracted over a quarter of all Americans to Chicago and its White City, the newly anointed American Mecca for those who believed in the original American ethos of life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness. And that is where The Making of American Aura begins.

April 29, 2020

Understanding history through the stories of those who lived it.

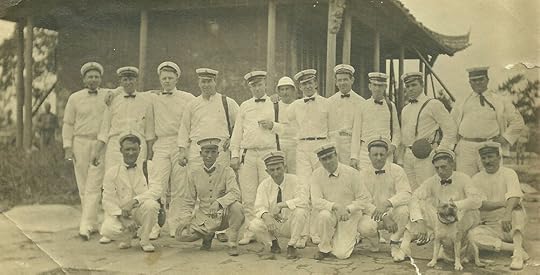

Hoosier sailor Aura Clark (top row, second from the right) in China, U.S. Asiatic Fleet

“Our best chance of understanding the Civil War era is through the eyes of the ordinary people who lived it,” writes Stephen Rockenbach, in his book, War Upon Our Border. I would expand this idea — our best chance of understanding our history is through the stories of those who lived it.

April 28, 2020

Women at the Chicago World’s Fair, 1893

The Women’s Building, Chicago World’s Fair, 1893. From the 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago website.

The 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago is non-profit website is dedicated the history and legacy the 1893 World’s Fair held in Chicago. They provide the following—

Several women played significant roles in making the 1893 World’s Fair a spectacularly grand affair. Chicago Architecture Center (CAC) docent Kathleen Carpenter will introduce you to these remarkable women artists, activists, and achievers in a video lecture “Women of the 1893 World’s Fair” at 7 pm on Wednesday, May 6, 2020. The program will be hosted on Zoom; registered guests will receive an email directly from Zoom on the day of the program with details about how to access and view it. The cost is $8 for the public and free for CAC members. For more information and a link to register, go to

https://www.architecture.org/programs-events/detail/cac-live-women-of-the-1893-world-s-fair/