Sara Crowe's Blog, page 4

July 15, 2014

Marshlands

A hectic few weeks and suddenly everything has changed. We’re no longer wanderers. We’re settlers with a couple of acres of overgrown land, a sound (we think) cottage in need of serious renovation, three milk sheds and various tumbledown outbuildings bodged together from corrugated iron, random bits of wood, old doors, salvaged windows, nails, string and sackcloth.

We share this place with badgers, foxes, Little Owls, Barn Owls, moles, voles, shrews, mice, pheasants, rabbits, hares, kestrels, bats, and lots and lots of birds. We’re told there are Muntjac and roe deer around but I haven’t seen any yet.

Our stuff arrived out of storage yesterday. Furniture, and many big boxes whose contents we’ve long forgotten. Having lived comfortably with much less stuff for so long, it’s a culture shock. Possessions weigh you down. They feel like too much gravity. We’ve become unused to it. But some things are welcome – a proper fridge-freezer, a washing machine, all our tools, certain things of sentimental value.

Living in a van for so long, we learned that you don’t need much indoor space if you have the outdoors, and that you don’t need a lot of possessions to live comfortably and well. I worry that I’ll gradually unlearn this lesson. I hope not, because it’s a valuable one.

We’re like rabbits caught in the headlights. So much to do that we barely know where to start.

Mixed feelings, but also excitement and wonder. These are the flatlands, the Marshlands, ancient and mysterious. The skies and horizons are vast. I saw the pale orange supermoon rise through a drift of pale cloud. I saw a barn owl hunt in the field across the lane. I saw a tiny shrew emerge from the long grass and snuffle around. I saw early morning mist fading as the sun rose. The air is full of lark song, sparrow chatter, the two-note calls of pyewipes.

And all is well.

June 22, 2014

Reading things: some book recommendations

One of the great joys of waving goodbye to my old life and setting out on a great adventure in a camper van has been that I’ve had lots of time to read. This seemingly small thing has been extraordinarily exciting, like falling in love over and over, with something of the intensity and wild joy books inspired in me when I was a child. I can’t list every wonderful book I’ve read over the past couple of years but here are a few I’ve read and loved recently.

I bought Nigel McDowell’s first book, Tall Tales from Pitch End, because I loved the title and the cover. Then I read it and loved it even more – an isolated rural micro-tyranny, a mysterious book of folk tales that may in fact be a history of Pitch End, a rebellious and dogged young hero, sinister clockwork cats… It’s a glorious feast of invention that, like all the best fantasy, asks big questions that resonate in our real world.

I preordered The Black North long before its release earlier this month and started reading as soon as it arrived. Like Tall Tales from Pitch End, it has a wonderfully evocative cover and page after page of McDowell magic within. Where Tall Tales from Pitch End is set in a tiny, cut-off corner of the world, The Black North is a perilous journey into an unknown full of terrors and wonders as Oona and her shapeshifting jackdaw companion Merrigutt search for Oona’s stolen brother. Here you’ll find bog-soldiers, Briar-Witches, a sinister creeping blight, Ponderous Giants, and a magical stone ‘the size of a plum, and not far off the same colour’. Oona is as fierce, bold, stubborn, resourceful and loyal as you could wish for in a heroine and at the end… let’s just say that I wanted to go with her.

Nigel McDowell is one of the most exciting and original YA fantasy authors around. Strongly recommended for readers aged 10 to 110.

Another, very different MG/YA novel that I’ve read and loved recently is Murder Most Unladylike: A Wells and Wong Mystery by Robin Stevens. This is a super book – a proper old-fashioned murder mystery (and by ‘old-fashioned’, I don’t mean in a fuddy-duddy way but in its commitment to great storytelling). Set in a boarding school in 1934, 13 year olds Daisy Wells and Hazel Wong – the founders and only members of the Wells and Wong Detective Society – set out to discover who murdered Miss Bell in the gym. They soon find themselves caught up in a web of secrets, intrigues and denials. Funny, pacy, charming, packed with boarding school lore, this is a clever, twisty and delightful start to the Wells and Wong Mystery series. I read it on a hot, crowded train and was mercifully transported to the 1930s world of Deepdean for the duration of my journey – so much so that I nearly missed my stop.

Finally – Janni Howker. Janni Howker! Somehow until a couple of weeks ago, I’d never heard of her or read any of her books. I’m not sure how this oversight happened but there it is. Then Gordon Askew mentioned her book The Nature of the Beast in his very generous review of Bone Jack on his blog Magic Fiction Since Potter. And so I read The Nature of the Beast, then I read Martin Farrell, and now I’m reading Badger on the Barge and Other Stories. Bleakly beautiful, raw, local yet with a universality and timelessness that comes from their intense humanity and the folklore that runs through them like a river – just go read them, if you haven’t already.

June 13, 2014

A conversation with S.P. Moss

Flying and travel are in S.P. Moss’s blood – she visited four of the world’s continents before starting school. She read avidly and wrote determinedly in between plotting to become a spy and building brother-proof camps.

She studied Psychology at Trinity College, Cambridge, taking part in some interesting experiments in parapsychology as well as playing trumpet in a Big Band.

A chance meeting in an Austrian ski hut resulted in more travel – this time to Germany, where she now lives in a small town outside Frankfurt with her husband and son. She still makes use of her trumpet-playing, spying and camp-building skills in her busy life as an author, mother and freelance marketing consultant.

The Bother in Burmeon was her first published novel. The danger, dirty deeds and derring-do continue in the sequel – or is it a prequel? – Trouble in Teutonia.

Sara Crowe – Your books The Bother in Burmeon and Trouble in Teutonia are a carnival of genres. There are strong echoes of Boy’s Own Annual adventure fiction, war stories, spy stories, historical fiction, and a nod to fantasy in the devices of the magic kaleidoscope and time travel. Are relevant storytelling traditions important to you and, if so, what do you think they offer young readers today?

S.P. Moss – A carnival of genres – I like that! I’m lucky, in a way, that in writing for children you don’t need to worry too much about which genre you’re in. I loved all the influences you mention as a child – not just in book form but also through films and TV series, and they all found their way into Burmeon and Teutonia – from Biggles to Bond, from Tintin to Thunderbirds. I suppose I could have left it at that, but I felt it important that children today should feel some sense of connection to that world, hence my main character being very much a 21st century boy. My son was born in 2000 and is partly fascinated and partly bewildered by 20th century technology – you can’t just delete everything and Play Again. And in your book Bone Jack, although Ash may Google this or that, the internet can’t give him the answers to the dark mystery he’s involved in, nor can it fight his battles or run his race.

Sara Crowe – I was very aware of having to negotiate internet and mobile phone use in Bone Jack. It was important to me that Ash and Callie went to a library rather than spending 5 minutes on Google to get all the answers they needed. There’s a magic and thrill of discovery about libraries that you don’t get from search engines, as well as archives and collections that don’t exist anywhere on the internet.

Mobile phones can present a different sort of problem if your story is set in the 21st century. You can’t put your protagonist in jeopardy and then have your reader thinking ‘Why doesn’t he just phone his dad or the cops?’ so you have to find reasons why that’s not possible – no signal, a flat battery, a lost or forgotten phone, or perhaps make your character someone who refuses to ask for help or doesn’t have anyone he or she can call upon.

This won’t have been such an issue for you because Billy time-travels back to 1962 in The Bother in Burmeon and to 1957 in Trouble in Teutonia, long before mobile phones and the internet existed. Did you find it liberating in any other ways to set the main part of your stories in the past?

S.P. Moss – Liberating is a good word. One idea I had when I started the stories was to make a bit of social commentary about our health & safety obsessed, risk-averse society. It was just after the time that The Dangerous Book for Boys and its clones came out, and all those “Born in the 50s/60s/70s” articles were floating around the ether (emails with huge distribution lists in those days, rather than Facebook!). Children didn’t seem to be having adventures in the real world any more – it had become “out of bounds” or only accessible if dressed from head to toe in protective clothing. Adventure had become virtual. It was refreshing to write about a lost world of “goodies and baddies and brave Uncle Johnnies” as my master-villain Featherstonehaugh puts it, without worrying too much about being strictly PC, or giving Billy’s heroic Grandpop “issues” instead of letting him get on and fly planes, wield swords, right wrongs and generally be an action man.

Refreshing and liberating for me, yes, but in my search for an agent and a publisher, I still wasn’t convinced that the “Boy’s Own Adventure”, reimagined for the 21st century was exactly what they were looking for.

Sara Crowe – Many contemporary adventure stories seem to be set in fantasy, science fiction, or dystopian worlds. The hunger for adventures hasn’t gone away but often it’s transplanted to a world or a time that’s at a remove from ours. It probably also has something to do with changed perceptions of our own world in an age of TV, affordable air travel, and ladders on Everest. Even so, adventures set in our own world do seem to be making a come back – you mentioned The Dangerous Book for Boys, and Anthony McGowan’s Willard Price Adventure books also spring to mind.

I note that we both have boy protagonists. A boy protagonist wasn’t a conscious choice on my part – my major characters seem to manifest fully formed in my imagination and once that’s happened, I find it impossible to change them much. I also wanted a particular dynamic in Bone Jack – a boy who hero-worships his soldier father in a rather childish way and whose priorities and assumptions about what courage is are challenged and changed by the reality of the damaged man who returns from war.

How did Billy arrive in your imagination?

S.P. Moss – Billy arrived via my son – who has always been a bit of a dreamer. At some absurdly young age, someone suggested I should get him “tested” for Attention Deficit Disorder, which of course I didn’t, but I did read a little into the subject with the result that Billy is a boy with a vivid imagination – and difficulties concentrating at school. His name, Billy Blake, is no coincidence as I feel what is labelled as a disorder these days may actually be a special ability. I go along with Billy’s famous namesake in believing “If the doors of perception were cleansed, everything would appear to man as it is, infinite.” It seems quite possible to me that normal human perception only lets in a small percentage of what is going on out there. Some of us are better primed to access beyond that small percentage than others. This ability may well attract a negative label as it deviates from the norm, from expectations. Edith Sitwell said of Blake: “Of course he was cracked, but that is where the light shone through.”

I do detect something of this theme in Bone Jack, too – the sense of the vastness of nature and eternity, with us, at the present time, being only a minute speck on an infinite canvas.

Sara Crowe – For me, the appeal of writing and reading about landscape, nature, history, or huge events such as war or revolution, is the shift in perspective that comes from that. Painting characters and their lives into a vaster canvas opens up all sorts of possibilities, new connections and ways of seeing and understanding, as well as any amount of dramatic potential. The writers whose books I loved as a child all did this, in their different ways – Susan Cooper, Alan Garner, Rosemary Sutcliff, Jack London, Ursula Le Guin.

To change tack – you’ve now got two books featuring Billy and his trips back in time to Grandpop’s heyday. What’s next? Will there be a new Billy and Grandpop adventure?

S.P. Moss – In the same way that your characters appear fully-formed, Billy and Grandpop’s adventures arrived in my head as a series, so yes. I have had ideas for the third and fourth books floating around in my head, accompanied by odd notes in various places for some time now.

When I think about it, it is rather odd that I am writing a series. At primary school, I went through an Enid Blyton phase as anyone who reads my books can tell (!) but from the age of 9 or 10, apart from an odd foray into Biggles, all the books I read were of the non-serial variety.

I assume that Bone Jack is standalone – what part do you think series play for children and YA readers (and writers/publishers) vs. one-off novels? I’m wondering about supply and demand here.

Sara Crowe - Yes, Bone Jack is a standalone. I think series need to have either a significant world-building dimension or else a premise that propels the same core characters into a series of self-contained adventures, which is what the time-travel kaleidoscope does in your books.

My next book will be another standalone but I also have two very rough outlines for series – one a dark fantasy YA series and the other for an adult crime series. I’m not sure if I’ll ever write them though – I’m always sketching outlines for books that will probably never be written. Having an idea is one thing; having a good idea is another. Which brings us to that question that so many writers seem to dread: where do you get your ideas from? Or, to be a little more subtle about it, what fires your imagination?

S.P. Moss – Maybe writers dread that question because it’s a very difficult one to answer when phrased in the general. It’s certainly easier to answer about a specific book. My view is that ideas come from a fusion of the external world, with all its colours, sounds, sights and smells (and here I do find the internet a rather pale reflection) with the personal, internal world of the author, where memories, dreams and imagination live. This fusion creates an energy that’s hard to stop once it is unleashed.

The inspiration for Bother and Trouble came while I was writing a biography of my dad for friends and family. I’d spent ages poring over log books, black and white snapshots in exotic locations and reminiscences from old chums when my young son asked what his granddad was like. One of those delightful “what if” questions flitted into my mind, and with it a lost world full of danger, dirty deeds and derring-do. This was no fantasy world, but rather the past re-imagined, as seen through a mysterious kaleidoscope by a 21st century boy. It’s a world built from early Bond films, mid 20th century book covers, Betjeman poems, old BOAC posters, Ladybird Books, 1960s TV series … and all before Pinterest came along! My publisher described it as “a long-forgotten beauty – not fantasy, not ancient history, but something you and I had forgotten was magic: a Britain where country roads were bright and welcoming, where cars, motorbikes and aeroplanes – not to mention their pilots – still had an aura of adventure about them.” I recently saw the film The Grand Budapest Hotel, which I loved as it builds a world that is the past, but not exactly.

But it’s important that the fusion I mentioned can’t be forced. It has to be a case of spontaneous combustion. While I was trying to find a publisher for my first book, I had another idea that came from thinking about “what could be more commercial – what would agents/publishers jump at?” – it was a YA story based on real historical events. Funnily enough, I never had the energy to write it – and I have noticed recently that a book on exactly this theme has just come out.

Sara Crowe – That’s a great point about the ‘where do you get your ideas from?’ question being too general. It may be easy to say where a particular idea came from but novels are a mesh of many ideas, some of which seem to appear out of thin air, like magic. Most of my ideas start with a setting. It might be a whole landscape, like the mountains in Bone Jack, or an old house, or a gnarly oak tree, or a little crossroads along a quiet country lane, or anywhere. Then it does get a bit like magic – I’ll get a vision of a character in that setting, perhaps a whole scene. If it’s interesting enough to me, I start to build on it. Who is this character? Where did they come from? Why are they here? What will happen next? Almost before you know it, a story is unfolding.

S.P.Moss – Well, having been entranced and enchanted by Bone Jack, I’m intrigued to see which settings have worked their magic for your next book. I’m busy at the moment marketing Trouble in Teutonia – setting up a few school visits, which I love doing (and it gives me an excuse to come home to the UK). Being with a small publisher, a lot of the onus is on the author to promote their work, so it’s great to find guest blog spots or fellow authors with whom you can chat in public! This conversation has been both fun and stimulating so thanks ever so much for having me. And soon, I’ll start piecing all those notes and ideas for my next adventure together. It’s set even further forward in time than The Bother in Burmeon, in 1966, so there will be a few tricky time-travel dilemmas to play with. I just need to get cracking now, as Grandpop would say.

Sara Crowe – Back to it, then! Thank you so much for talking to me!

You can read more about S.P. Moss, her books and their world here and here.

June 10, 2014

In which I go orchid hunting

Orchid hunting sounds tame. But it’s not. William John Swainson brought tropical orchids to Europe from Brazil in 1818. Soon, the weird architecture of these colourful, fleshy plants inspired a craze: orchid fever. With fortunes to be made, in the century that followed intrepid orchid hunters set forth to seek rare and exotic specimens in the far corners of the Earth.

The world was a lot bigger back then. Not literally but figuratively. The orchid hunters travelled for weeks by sea to reach their destinations, then continued by horse or on foot into wild, roadless terrains. These were difficult, dangerous expeditions. In 1868, botanist David Bowman was attacked and robbed of his collection in La Paz, Colombia. He died of dysentery in Bogota soon after. William Arnold drowned in the Orinoco River. Augustus Margary was murdered in China, Osmers was killed somewhere in Asia, Bestwood vanished in Madagascar… and the list goes on. Perhaps the most unfortunate expedition was to the Philippines in 1901. One member was doused with oil and burned alive. Another was killed by a tiger. Five others vanished in the deep forest. The lone survivor returned with around 7000 orchid specimens.

Luckily for me, the wilds of Lincolnshire are considerably less perilous. And so it was that Dog the Smaller and I set out in the noonday sun to hunt for orchids.

Around 50 orchid species are native to Britain. Different species like different habitats so you may find orchids in woodland, meadows, on heathland, in marshes. On paper, the area I went orchid hunting looked promising for several species: chalky soil, plenty of open swathes of long grasses and wildflowers.

We wandered along paths that are now no more than creases in the early summer growth. We pushed valiantly through a seemingly endless exuberance of brambles. I was wearing knee-length shorts, which was a bad move – my legs are still buzzing with nettle stings.

Bees droned.

Butterflies flopped.

Path after overgrown path.

There was dog rose:

There was lesser stitchwort:

There were delicate ropes of vetch twisting around grasses:

And not a single bloody orchid did I see.

Until at last we walked along the stony track leading back to the lane. Then there was this solitary but unmistakable spike of speckled pink:

Not so common around here.

May 20, 2014

On the verge

There’s a straight footpath we sometimes walk, a narrow worn track with ditches and birch woods on either side. Along its length run margins of the same exuberant greenery you can find along any lane or road until council mowers arrive to raze it. We pass it all the time but rarely pay it much attention. But when you stop to look, it’s no longer nondescript green stuff but cow parsley, dock, nettles stinging and dead, tall grasses, ribwort and broadleaved plantain, dandelions, wild campion, meadow buttercup, and much else.

Verges are important habitats, teeming with insects, their flowers food sources for bees and butterflies. In these dense and diverse mini-forests, small mammals forage and tunnel – vole, shrew, wood mouse. As I walked, a frog crossed the path in two huge leaps and, a few minutes later, a stoat rippled ahead of me before vanishing into the undergrowth.

Speedwell

Speedwell

Vetch

VetchTwo photos of vetch, because I love its delicate green, its symmetry, its questing tendrils.

Vetch

Vetch

Silverweed

SilverweedThe Welsh name for silverweed is Palf Y Gath Palug, Cath Palug’s Paw – named after a monstrous cat that haunted the Isle of Anglesey and killed nine warriors before it was slain by Cai, Knight of the Round Table.

Life and lore. It’s all around us when you look for it.

May 19, 2014

A soundcloud trailer for Bone Jack

May 7, 2014

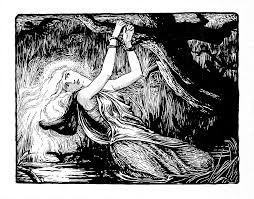

A Tale of the Drowned Moon

The Drowned Moon, or The Buried Moon, is a strange old tale from Lincolnshire. The best version is by Joseph Jacobs in his collection More English Fairy Tales (1894). Mine is a pale imitation but folk storytelling is a living tradition and its tales are meant to be told and retold so I’m retelling.

This tale is set in the Carrs – a flat, marshy area between the Lincolnshire Wolds and the Lincoln Cliff.

If you’re sitting comfortably, then I’ll begin.

Pity the traveller who finds himself out in the Carrs on a moonless night. Such paths as there are wind through bogs and around the edges of deep black pools, over tump and tussock, through sticky muck and alongside stinking streams. The lanterns of will-o’-the-wykes flicker far out across the marshes, luring the unwary to a watery doom. All else is a terrible dark and from this dark come things that creep and things that crawl, things that slither and things that grope and grab, screaming howlers, quicks and bogles, chill gobbins that suck the heat from your blood, long-fingered boggarts dripping weeds, snags that claw, rip and grip.

The Moon heard tell of these horrors. Being a kindly soul, she decided to find out for herself what evils oozed from the darkness on those nights when she did not emerge to brighten the night. So she wrapped a black cloak around herself to hide her light and out she went along the devious marshland paths.

She wandered far out into the bogs, with only starlight to guide her and with terrors all about her.

All was tarry dark. On and on went the Moon until at last she stumbled at the edge of a deep black pool. She snatched at a snag to stop herself falling in but as she gripped it so did it grip her, twisting its woody fingers about her wrists until she was held fast. All her struggles were to no avail; the snag had her and she could not break loose.

So she waited, starting at every slurp and suck and sigh and snarl out in the fathomless night.

Time passed and then came other sounds: panicky splashes, stifled sobs and fearful moans. Through the dark came a man, senseless with terror, blundering through mud and mire.

Kindly was the Moon so she twisted and wrenched and fought against the snag’s grip. Still she could not break free but her efforts caused her cloak to fall open. Her glorious silver light burned bright across the marshes, lit up the paths, chased the crawling things back into their dark places.

The man sobbed with relief. In his terror and haste, he gave no thought to the source of the light. He only fled back to the path, running as fast as he could in the direction of the nearest village.

Exhausted, the Moon slumped to the ground. Her cloak fell about her once again, and the pitchy dark flooded back across the Carrs.

Seeing their old enemy helpless, the horrors crawled out again from their hide-holes. They swarmed about her and filled the night with their screeches and howls and curses.

‘You!’ screamed the witch-bodies. ‘You broke all our spells with your moonbeams!’

‘You drove us into the cold black depths,’ hissed the boggarts, ‘and kept us there.’

‘We were hungry, always hungry,’ whispered the quicks, ‘because of you.’ And they whined so pitifully that the Moon would have been overcome by guilt had she not known that they hungered only for souls and warm blood and living flesh.

‘Smother her!’ cried the witch-bodies. ‘Smother her, smother her!’

Then all the night creeps joined in together, the gobbins and bogles, the quicks and boggarts, the necks and fetches, the ullerts and witch-bodies, until the marshes crackled with their howling chant of ‘Smother her! Smother her!’

By now, the dark was dimming in the east. The spiteful creeps gazed upon and knew they hadn’t much time before the first light of morning drove them back into the shadows. They crowded around the Moon, bent their bony fingers about her and hauled her down into the black pool at the foot of the snag. Then the bogles fetched a huge rock and dropped it upon her to keep her under the dark water forever.

As the sun rose, the horrors retreated into their pools and slimy crevices, their dank lairs among snag roots and under rocks.

The Moon lay buried under the rock, dead to all intents and purposes.

Days past. The time of the New Moon came but no New Moon appeared. The nights stretched black and empty from sunset to sunrise and the bog horrors grew wilder and bolder and no man, woman or child dared stray outside the villages after dark.

When the Carr folk could bear it no longer, a group of them went to the Wise Woman and asked her what they should do.

The Wise Woman gazed long into her cauldron and into her Magick Book. At last she said, ‘The dark has brewed so thick and deep that I cannot see what became of the Moon. Come back to me when you’ve got something more for me to go on.’

The Carr folk returned to their homes, for there was nothing more they could do. More days and more terrible nights passed and they hummed and hawed and puzzled among themselves whenever they gathered at the inn.

One such evening, a man from the other side of the marshes overheard their talk. All at once he slapped his mug of ale down on the table and stood up. ‘By my faicks!’ he exclaimed. ‘I reckon I know where the Moon lies hid!’

And he told them how he’d got lost in the bogs one night, all panicked and hounded by the creeping things, until a silvery light shone bright and showed him where the path was.

Back went the folk to the Wise Woman and told her what the man had told them.

Again the Wise Woman gazed long into her cauldron and long into her Magick Book.

‘The dark is still deep and sightless,’ she said at last. ‘But I’ll tell you what you must do. Leave just after the sun sets. Each man of you must hold a stone in his mouth and a hazel twig in his hand and speak not one word until you’re home again. You must go far out into the the marshes until you find a coffin, a candle, and a cross. Then look around you until you find the Moon.’

The next night, just after sunset, the men set off, each with a stone in his mouth and a hazel twig in his hand and no word uttered between them. Frightened though they were, they kept along the path. Deeper and deeper they went into the marshy wastes, and all along they heard squelchings and slitherings and eerie howls, felt cold breath against their skin and the scraping of bony fingers through their clothes.

At last they came to the black pool where the snag had caught the Moon. There they saw the rock that the bogles had brought to bury the Moon, lying half in and half out of the water and as long and as deep as a coffin. And upon it danced a will-o’-the-wyke, its lantern for all the world like a candle flame, and there above it was the snag with its thorny boughs outstretched like a cross.

The men searched all around, in the bogs and the slimy streams and among the tussocks, but there was no sign of the Moon.

One man peered down into the black pool and there, where the rock sat in the dark water, he saw the faintest glimmer of silvery light. He called the other men around and together they seized the rock and strained until their sinews tautened like ropes and sweat lay upon them like dew and they heaved the rock aside. For one brief instant a lovely face looked back at them and smiled. Then a great wash of silver light blazed out and dazzled them. When they shook the glare from their eyes and looked up, there was the Full Moon in the sky.

The Moon sent her shimmering light out across the bog lands to light up the paths and to chase the creeping horrors into the deepest nooks, as if she wished them as far away from her as possible.

April 28, 2014

A Walk in the Woods

We’ve given names to the paths we walk regularly, purely for the purpose of describing routes taken and planned, the locations of certain things and events. There’s nothing romantic or poetic about these names. They map the woods prosaically: the Brambly Path, the Pine Needle Path, the Beech Leaf Path, the Fox Poo Path, the Escaped Cow Path, the Amanita Path, the Badger Sett Path, the Muntjac Path. More whimsical is the Baba Yaga Path, so called because it tunnels through mostly dead trees and looks very much as if it might lead to a fence of skulls and bones and a weird hut that stands on huge chicken feet.

The Baba Yaga Path

The Baba Yaga PathAt this time of year, everything changes very quickly and there’s always something new: an intact pheasant egg, oddly placed atop a tree stump; a muntjac doe with a fawn in tow; a blue mist of forget-me-nots edging a forest of nettles; an orange-tip butterfly;. the fresh living greenness all around.

New growth birch leaves

New growth birch leavesOne of the things I love most about photography, or any sort of seeking, is that it slows you down, obliges you to take in what’s around you. The swathes of random green weeds (long grass, nettles… stuff!) that we usually pay no attention to as we stride past suddenly come into focus – silverweed as pale as moonlight, delicate wildflowers, a flake of bark that’s actually a subtly beautiful spider, a beetle with a carapace that shimmers like oil on water, tiny ferns, perfect little toadstools as bright as embers.

Sulphur tuft

Sulphur tuftAnd in this close-up world, there are miniature landscapes – alien forests of moss and lichen, tiny mountains, hills and valleys, scattered with a gigantic detritus of leaf, catkin, twig. My photographs of these aren’t particularly popular but I like them because something about the scale makes me marvel at them. Perhaps I should Photoshop in a few teeny hobbits on a perilous quest… But for now, you’ll just have to imagine them.

April 25, 2014

Road’s end

Yesterday we sold our van and this morning the new owner drove it away.

We stood in the rain and watched it go. It was our home for almost 18 months. It’s taken us all over Britain, from Dartmoor to the Orkney Islands, Snowdonia to the salt marshes of Norfolk. Crows and gulls have trotted around on its roof. Foxes have circled it, yowling and yelping. It got stuck in the mud in Kent and had to be hauled out by tractor. Rocked like a boat on a rough sea in the storms that ripped across Britain through the winter months. It’s inched along narrow winding mountain roads at the edge of terrifying drops. It’s never failed to start and it’s kept us warm, dry and safe throughout our meandering 10,000 mile journey.

In that van, I learned how to be me again instead of the stressed-out and half crazy ghost-version of myself that I’d become. I rose with the sun, walked a thousand footpaths, read books purely for pleasure, finished the edits on my own book, fell asleep at night listening to owls or curlews or the slow rhythms of the ocean or the wind howling through trees.

And now the van is gone. Soon someone else will load it up with dogs and bikes and boots and head for the horizon.

Instead we have a car, a caravan, a tent. In the summer, we’ll move on to a scrap of land with a few ancient milk sheds and resident kestrels, barn owls, foxes, badgers.

But one day, maybe quite soon, we’re going to get another, smaller van. And we’ll be off again.

April 12, 2014

Dissecting a kestrel pellet

The other day I found what I thought was an owl pellet under a big old tree. A pellet consists of the undigestible parts of the bird’s diet, regurgitated in a neat little package.

It was about 4cm long, very pale grey, rounded at one end and tapered at the other. Lots of birds produce pellets – not only owls but also raptors, rooks, jackdaws, gulls, blackbirds, even robins. So I did some research and, so far as I can tell, it seems it’s not an owl pellet but a kestrel pellet.

I broke it open. It was dry, crumbly, dusty. It didn’t smell. Inside were lots of tiny bone fragments in a felty wrap of fur and feather.

I used tweezers to pull out fragments – bone, feather, a little claw, something that looked like a tooth.

Kestrels have stronger stomach acid than owls so the bones in their pellets are more damaged and less easy to identify. But the feathers indicate a small bird, and from what’s left of their colouring it was perhaps a long-tailed tit. One fragment looked like a little spiky tooth, perhaps the remains of a shrew.