Laura Crossett's Blog, page 8

August 23, 2015

The movement empowers the community: Steven Kanner, In Memomoriam

The fall of 2001 was not a particularly good time for anyone, but it was a particular kind of very bad time for those of us who are pacifists.

I taped a peace sign to the front window of my apartment with masking tape that night; it stayed there till I moved out two years later. It was a patched together thing, uneven, hopelessly hippie-ish, a sign to most, I would guess, that I could not be taken seriously. But I did it anyway, and I kept it up.

Those weren’t easy days. Neal Conan was hosting call in shows on NPR where he’d lambaste anyone who suggested maybe we shouldn’t be bombing Afghanistan. And that was NPR (which my friend, who’d been calling it Neoliberal Propaganda Radio, just started referring to as Nationalist Public Radio). I couldn’t bear to check any other major news source. A group of us met on an upper story lounge of the IMU a few nights after the planes hit to start a group to do something, and Iowans for Peace later did a lot of things — rallies and candlelight vigils and letter-writing campaigns and all the things you do to fight a force larger than you, one you know on some level you can’t stop but that you know you have to resist. And then you wonder at your metaphors — fight, resist, disobey — because all you ever wanted to do was create the beloved community, and here you are in the master’s house with nothing but the master’s tools.

But we met and we marched and we stood in silence, shielding lighted candles, and we wrote letters at a pizza joint downtown, because we cared about stopping the war, but also because we cared about each other. And so sometime that fall when some people started talking about going down to the SOA protest that year, I decided to go along.

Steven Kanner’s sister Rebecca was serving a prison sentence at that time for civil disobedience at the annual SOA march a year or two before. Steven had been going for some years, and likely he was the impetus for the trip that year. I knew Steven as the progressive on City Council, the one who came to Students Against Sweatshops events, the one took us seriously, as he took everyone seriously. I also knew him as something of a doofus, a guy I knew and liked and respected but that I knew no one on Council, and few in town, would ever take as seriously as he took us.

We had a few meetings, rambling affairs held on the porch of the coop house in town, where people would half talk politics and half strum guitars, and then we took off in caravan. My friends Meg and Erica and I took my car, Steven and our friend Karly and a WWII resister whose name I’ve forgotten were in the next, and the rest, whom I can still picture but can no longer name, came in a third.

The times were awful, and the cause was deathly serious, and the drive was long, but it remains suspended, as some drives do, in a magical, out of time place. Meg and Erica and I lost track of the caravan at some point because we got so dreamily distracted singing along to “Rocky Mountain High.” None of us had cell phones yet, but we found each other again somehow. We drove through the night, taking turns, and pulled into a Waffle House in Georgia just at dawn. We stood in the parking lot, dazed, exhausted yet awake, blinking slightly, and Steven — of course Steven — insisted we all do a sun salutation, which he led us in, right there in the parking lot: nine pasty white Midwestern hippies doing poorly formed yoga in a deep South Waffle House parking lot as the sun rose. That was Steven all over.

That night we settled into our rooms at the motel, and Steven — of course, Steven — organized a group to go watch the Leonid meteor shower, and of course I did not go. I don’t remember if it was that night or the next day, but at some point Meg came to me and said, “Oh God, we’re in trouble.” What was it? I asked. “You know Karly rode down all the way next to Steven?” she said. “Well, she just came and told me, ‘Steven and I are in love!’”

We rolled our eyes and sighed, certain we knew better, sure this was going to end in more heartbreak.

We were wrong, of course — or if we were right about the heartbreak, we were wrong about its cause or its timeline. Meg is dead now, and the School of the Americas is still there, and we are still at war. And now Steven is dead, too.

But we were wrong about their relationship, which started that trip and carried on. We were wrong to doubt love and faith and strength, which are the only things, ultimately, that keep us going — the things themselves, and the memory of them. Meg and I talked about that a lot, when she was still here, and writing now I feel her chortling with me still — chortling and then weeping.

This has ended up being more about me, and about Meg, than it is about Steven, which is wrong for Steven but reflective of him, too, and the ways in which he cared for others above himself at all times.

I knew him very little, really, and I learned very little about him. It is my loss. I’ve been reminded in these past weeks of a story someone told at my own father’s memorial service — an old rabbinic tale about “a scholarly and pious man who was repeatedly and brutally rebuffed by those to whom he tried to impart his love of truth. Finally he was asked by a sympathetic man why he persisted in the face of continual failure. He replied, ‘At first I spoke to change people and when I realized I could not change them I kept speaking so that they would not change me.’”

That story is one part of Steven — the part we all know that loved social justice, the part that, as another old friend of our said, was “at odds with a world at odds with justice.” But as I’ve thought about it more I’ve realized it isn’t nearly all of him: for Steven wasn’t simply a person who spoke out against injustice and continued against the odds (though he was that, too). He was a person who in his own life created the beloved community.

We live, I think, by these moments of grace that come in the midst of chaos and tragedy and fear and boredom and nitwittery. Mostly you work and grocery shop and pay bills and do dishes. Sometimes you drive insane distances to protest human rights abuses and don’t get enough sleep and eat too much bad road food and possibly have no effect on the state of the world at all. But then sometimes you find yourself with your friends, doing sun salutations in a parking lot.

Steven lived more of those moments than anyone else I know, and he was better at creating them than anyone I have ever met. I wish I had paid more attention and shown up more.

At the last hootenanny I remember going to before I left town, or before Steven and Karly did, we sang Phil Ochs’s “When I’m Gone.” I’ve always thought of it as the depressive’s social justice anthem, in that it lists both all the pleasures and all the responsibilities that one can’t enjoy or take on when one is dead, so, as the refrain goes, “I guess I’ll have to do it while I’m here.” Steven was a far more energetic and upbeat person than Ochs, or than me, and when I let his spirit in, it’s talked me out of many a funk—as it has many others, I would venture. I guess we’ll have to do it on our own now, but with the memories and moments he created to guide us.

July 17, 2015

Where All the Pages Are My Days

Detail from a Grateful Dead poster drawn by my old friend Josh Koza. Order your copy from his Etsy shop.

I have spent what I can only consider to be an undue amount of time considering the Grateful Dead song “Sugar Magnolia.” [lyrics, YouTube] It is—in case by chance you are not familiar with it—a very pretty and deeply problematic song about what my friend once called a fantasy hippie chick (what we might now call a manic pixie dream girl) who “takes the wheel when I’m seeing double / pays my ticket when I speed” and “waits backstage while I sing to you.” (I’ve also always taken the line “head’s all empty and I don’t care” to refer to the chick, although my friend claims it refers to the dude, which is perhaps a more accurate reading.)

I first started listening to the Dead in high school. I had a dubbed cassette tape, Workingman’s Dead on one side and American Beauty on the other, and a couple of other tracks to fill out the remaining minutes. I am the sort of fan who never went to a show or owned a bootleg, but those songs got to me early, and it seems when I think about it as though there was some eternal April month in high school in which we all quoted from those songs, as if they were a natural extension of our vocabularies, as we all felt we lived in a typical high school involved in a typical daydream. To be seventeen and contemplating the attics of one’s life is ridiculous, of course, but I did it, and surely I cannot have been the only one.

I dwell, for better or for worse, largely in the past, and in the shifting land of memory. The summer after that eternal April I read Virginia Woolf’s Mrs. Dalloway for the first time, and I was blown away, not by the stream of consciousness or the suicide of Septimus or whatever the hell else it is that blows people away about Woolf (though I was later blown away by all those things, too). But at seventeen what blew my mind was that Mrs. Dalloway, at fifty, spent so much of her day thinking about the summer she was eighteen.

Most of the grownups I knew held teenagers in such disdain that I assumed they had promptly forgotten everything about that time and what had happened to them, or that they chalked it all up to youth and stupidity and never thought about it except perhaps under great duress. But here was a woman — older than my mother! — thinking — obsessing, really — about being eighteen, and having a crush on a guy and also on a girl, and being so absorbed in these memories that they supplanted at times her own busy life in London, so many years later. I was astounded. The following spring I sat down in the classroom where I’d taken AP English until I dropped it (the instructor and I did not get along) to take the AP English exam. The essay question that year asked you to discuss a character who appeared seldom or never in a narrative but exerted great influence over it. Everyone I talked to that day and later, when I went to college, wrote about either the ghost in Hamlet or Kurtz in Heart of Darkness. I’d read both of those, Hamlet several times, but they never crossed my mind. I thought immediately of Mrs. Dalloway, and of the guy she’d had a crush on the summer she was eighteen.

I think a great deal about being fifteen and sixteen and seventeen and eighteen, and on the whole, despite the April of the Grateful Dead, and the day I walked home with a boy discussing Doonesbury and the Gulf War, and the day I got the highest score in the class on a geometry test, and the many, many days when my AP Government teacher let me off the hook for being late, and the day my friend brought a giant cookie for my seventeeth birthday, and the day another friend set two quarters in front of that same boy I’d once discussed Doonesbury with on his eighteenth birthday and we all laughed and laughed until he finally realized why (the Adult Pleasure Palace had a sign outside that read “50 CENT BROWSING FEE”) and turned beet red, on the whole, despite all those days, high school was a miserable rotten time for me.

Last summer, because my curiosity always wins, I went to my twentieth high school reunion, where any number of people whom I assumed had been having a fine time in high school while I had been feeling largely fat and miserable and unpopular told me that in fact they, too, had had a miserable time of it. I was stunned.

When I think of those days now, as I often do, I think then not only of the good bits and the misery but I think of the ways those superimpose themselves upon my life now, and I think how the only thing more stunning that the misery of the times then is how kind we all are to each other, for the most part, today—much kinder than we ever were before.

To think of the attics of your life at thirty-nine is still silly, though perhaps not quite as silly as it was at seventeen. But perhaps I knew at seventeen that I was forming the memories that would be stored in those attics, and that one day, feeling sick and miserable in the heat, despairing of how I ever got to this place, again, I would listen to those songs again and live once again in that eternal April, the last time I truly thought that something to come might be better, and that living in that moment again, it would, if only for a moment, give me hope.

July 16, 2015

Welcome, Rumpus Readers!

If you’re here, perhaps it’s because you read my essay Accidents on The Rumpus. If so, thanks a million! (If not, you can of course read it now.) And if you’d like to read more, here are a few things I’m particularly proud of.

The Psych Ward, 10 Years Out — on why I vote in every election

An Open Letter to W. Bradford Wilcox, Robin Fretwell Wilson, and the Editors of the Washington Post — my response to a particularly obnoxious op-ed

Control — the piece that became the prologue to Night Sweats

On Listening to Ani Difranco — self-explanatory, I think, if you were a young woman in college in the 1990s

The Medium is Not the Message — which won an award from the Electronic Frontier Foundation many years ago

Thanks so much for stopping by!

May 10, 2015

On Mother’s Day

I thought I might have more to say on this subject than I did fifteen years ago, in another lifetime, but for the most part I don’t, except to acknowledge how hard and awful a day it is for some people, and how I wonder, much as I enjoy seeing pictures of people’s mothers, if this might not be one of those days Facebook has made worse and not better.

I posted this there yesterday, but I wanted to get it into my own space as well, having gone to the trouble of scanning it and so on. A friend there commented that my name was bigger than the headline, and I said yeah, I used to be sort of famous in this town. That was long ago, when we had an independent weekly, and Dan Coffey (of Ask Dr. Science) and I both were columnists for it, and I was twenty-four years old and had just gotten arrested and accepted into graduate school, and I never planned to have a child. I still believe what I believed then, though, and that’s some comfort (as is the fact that I have a much, much better haircut now).

Here’s a PDF if you want something easier to read/download.

Iowa City / Cedar Rapids ICON, May 11, 2000.

January 22, 2015

A Birth and a Choice

Today marks two things: It is my son’s third birthday and it is the 42nd anniversary of Roe v. Wade. I assume that at least one of my readers will be concerned that I connect those two events, but to me their link is crucial. For a long time I wasn’t sure what exactly made me decide to have my son. The other day I realized: I was free to choose to have a baby because I knew I didn’t have to.

Like almost half of the women in the United States who get pregnant, I did not plan to get pregnant. In fact, I went to considerable trouble and expense — $500 out of pocket and three visits to a clinic 30 miles from where I lived that was open only during the hours I worked — in order not to get pregnant. Like all birth control, though, mine had a failure rate, and I am one of its number. (That I did not ever get pregnant while using much less reliable methods of birth control, or pure blind luck, still strikes me as deeply ironic.) Look around you: half the women you see with children did not plan to have them (half the men, too, presumably). That is a lot. Look again: one in three of those women will have an abortion during her lifetime. That is a lot, too. I offer these statistics not as reasons to mourn or to celebrate. I offer them as facts, like the rocks beneath your feet that may trip you, like the water in which you will either sink or swim. What I hope for is not so much a change in any particular policy as a change in attitude, one where pregnancy is seen as what it is — something bestowed at random, just as frequently coming to those who hope to avoid it as it avoids those who seek it. (It is also not lost on me that the day I took a positive pregnancy test is also the day I read my friend’s story about IVF.)

Abortion rights are perhaps the most heavily euphemism-ridden of all modern political issues, so we end up with “pro-life” people fighting the “pro-choice” people. I tend to say I am pro-abortion rights, as I find it less dodgy than the pro-choice formulation, and, like most people, for many years I was uncomfortable with saying I was pro-abortion. I’ve changed my mind on that, though. I am pro-abortion. I am in favor of recognizing it as a reality, as a necessity, as an inalienable right.

Roe v. Wade was decided, according to my limited understanding of the law, as a matter of privacy — that a woman’s right to her body and to privacy in the decisions she made about it outweighed the state’s interest in her body and its offspring. That’s still a good argument, and it’s still the right one, but it positions abortion as a thing that must always be private, and what is private is often seen as shameful. I am on the side of those who fight shame with openness, and thus I greatly admire (among other things) the work of the Sea Change program and this excellent op-ed piece by Merritt Tierce (really, just go read it — it’s much better than anything I’ve written here). And thus I write this here.

There’s a picture of me on the history wall of the Emma Goldman Clinic here in Iowa City. I was standing near the front of a Roe v. Wade anniversary rally when I was fifteen, and some of the organizers knew me from the anti-war movement, so I was asked to hold the amplifier for the primitive PA system the speakers were using. I was standing right by the speakers, and thus my picture got in the paper with theirs. Twenty four years later I am living back in the same town with my son who is, as the former director of Emma said to me when she met him, “a chosen child.” I would choose him all over again, and I do, every day. But my independence and my ability to do so come, so much, from knowing that I have that choice.

December 30, 2014

StartUp and/or/not Serial

Before we begin, a quick promo:

Do you get enough email in your life? Hahahaha. I know. But do you get enough email that you want to read, that feels the way email did in the 90s, back when it came from real people? If not, sign up for The New Rambler 2015 Email Series. Get an email a month from me all year long, and party like it’s 1994.

And now back to our feature presentation!

A lot of people on the internet these days, including a lot of people I know, are obsessed with Serial. I am not. I have heard it, or rather I have heard a little of it, and at some point I may listen to the rest of it, but mostly I find the critiques I’ve read of it far more interesting than the show itself. Like, do the producers really get the cultures of the people they are talking about? I don’t know, but I’m interested. The show itself is engrossing and slick and smart and everything you expect from a This American Life spinoff, which it is, but in the end I often feel like I’m listening to the 21st century version of a 19th century illustrated crime newspaper — with the added advantage that no one has to do the police in different voices, because they can, at least in some cases, interview the police directly and edit in a studio into this thing I can download on my phone and listen to wherever. The future is pretty amazing. But of course I don’t really care who done it, which is a fundamental problem when the chief dramatic tension in a story is did he or didn’t he kill her.

But as I’ve said, I’m not obsessed with Serial. I’m obsessed with StartUp. Last week on StartUp, Alex Blumberg said if you’d heard of StartUp but not of Serial, you occupied a very interesting niche in the radio landscape and he wanted to hear from you. I’m not a member of that niche, but I might be a member of one of its neighbors, and I have things I want to say on the subject. I was going to brag that I heard StartUp before I heard Serial, but then I realized that everyone did, or at least everyone one who listens to This American Life did: StartUp’s first episode was excerpted in Episode 533; Serial’s first episode was aired as Episode 537. So much for my vaunted avant garde.

StartUp, if you haven’t heard it, is this meta podcast that Alex Blumberg is doing about starting his own podcasting company. I adore Blumberg’s work. I liked it even back when he was doing quirky stories (The Family that Flees Together Trees Together is an early favorite). That expanded when he started doing more topical work (Somewhere in the Arabian Sea is brilliant even though in theory we’re not exactly at war anymore). When he started doing economics stories with Adam Davidson, though, he started being brilliant about something I’ve always thought I should know more about but hadn’t previously spent any time with, because, after the night in seventh grade when my mother spent several hours attempting to explain what “adjusted for inflation” meant (I’d gotten curious about a graph in the back of my geography textbook) and we’d both ended up in tears, I thought maybe economics and I just were not going to be friends.

Blumberg’s work with Davidson, first on This American Life and then on Planet Money, changed all that. I don’t really want to confess to you how many times I’ve listened to the financial crisis stories. I can’t, actually, as I haven’t kept track. I love Planet Money even though I find it, like much of NPR, incredibly centrist and occasionally a little dense (I loved the tshirt project, but was it really a surprise to anyone that the garment industry follows poverty? Perhaps to people who didn’t spend a few years in the anti-sweatshop movement trenches, or read Naomi Klein’s No Logo, or read The Nation for years before that…).

So I was intrigued when Blumberg decided to strike out on his own. Intrigued and worried, and worried for a variety of reasons. If you listen to the very first show, you’ll get some of that worry right off the bat. Blumberg is so awkward, so bumbling, so nervous, so… embarrassing when he’s trying to pitch his project to investors that I actually had to pause the episode a few times just to breathe. The dramatic tension is like that in a really good novel — the kind where you want to jump into the pages and take the protagonist and grab her and say, “STOP! NO! DON’T DO IT!” Brilliant.

What fascinates me about StartUp is its storytelling, which is just as produced as that of Serial but which feels fresher and… messier. I love a good mess. But I’m also fascinated by the tensions it brings up. When Blumberg makes his terrible pitch to Chris Sacca, a venture capitalist, Sacca first gives him a better version of his pitch — all the reasons Sacca and others should invest in his company. Then, seemingly with his next breath, he gives a pitch of all the reasons they shouldn’t. Among those is that Blumberg risks losing all his credibility with public radio listeners by becoming a commercial entity. Some episodes later, you watch that happen, as the team gets into a major internet scandal because they mistakenly let someone who was being interviewed for an ad think she was being interviewed for, well, This American Life.

This is a pretty fangirly post, and I am a big fan. But I’m also a skeptical observer. I really want to see if this thing takes off, if Blumberg and company can build a commercially successful podcast company, and if, in the course of doing so, they can keep my anti-capitalist public radio listener self as a fan.

November 11, 2014

On Anxiety

It starts in the hands. Or no. It starts in the chest. The tightness. The quickening of the heart. The heart beats too fast. Or is it beating at all? Is it there? The heart, it pumps the blood through your body, the blood to the hands, the hands that are shaking. If you’re driving, hold on. Don’t let go of the wheel. Only don’t touch it; you don’t know what it will do if you touch it. You might veer off, the car careening out of control as it does in your dreams, the pedals not working, not the one that makes it stop, and suddenly you’re running over the curb. Don’t drive on the curb, drive on the street. Follow the other cars. Do what they do. And breathe. You’re supposed to breathe. How does that work? In, out. In, out. In out in out in out in out in out inoutinoutinout wait. Not so fast. Can’t breathe fast. Slowly. So much work. Just think about driving, not about breathing. Your body will breathe on its own. Unless it doesn’t. But then you won’t have to worry about it any more. Now. Driving. Almost there. Hands on the wheel. Slowly. See? The car stops when you hit the brake. It turns when you turn. Carefully. Just a little.

If you’re not in the car there’s less to do, so that’s good. Just sit at your desk. No one is watching you. Just sit and it will look like you’re working. Breathing. You’re supposed to breathe. Same problem with that. In out inoutinoutinoutin. The hands won’t stop shaking. Don’t look at them. Water. Drink some more water. If nothing else, then you’ll have to pee, and that will be something normal you can do.

You’ll have to drive in the car later. But you’ll have to drive well because your kid will be with you, and you can’t hurt him. Hope he is okay. Hope he will eat dinner. Crap. Dinner. Must make something for dinner. Hands still shaking, and your kid will want you, and how do you make dinner and sit on the sofa with him at the same time?

Drinking stills the shaking. Have a glass of wine. They call this self-medication, and it’s bad, it works. You can’t take your real drugs because you’ll pass out, and you have to take care of your kid. Somehow no one seems to consider that part. You try to do the right things. Eat well. Go for walks. Breathe. But nothing seems to stop this shaking. Every day. Every damn day. Every day till you fall asleep, when you pray for quiet dreams.

August 23, 2014

This is My 38

Someone posted this thing about being 38 on Facebook, so I read it, on my phone of course, because that’s what I spend a lot of time doing these days. I am 38 and have a 2.5 year old, and my 38 is not remotely like this woman’s. I’m not married and I’ve never been married. Maybe that’s it. My kid is younger than her kids. Maybe that’s it. But whatever it is, I read that and thought, nope, nope, that’s not 38 at all. So here’s mine.

I thought maybe 37 would be the year I stopped getting zits, but I was wrong about that, and 38 has proved no better in that regard. But I am not giving up on miniskirts at 38 or any other age. I never have worn bikinis, though–too impractical for swimming, which is what I do when I’m in water. Even if I had positive thoughts about my belly, my skin is far too fishbelly white to expose that much of it to the sun’s cancerous rays.

38 is realizing that I just don’t care anymore what you think. I feel invincible. I feel like Teflon, or better yet, cast iron. Really well-seasoned cast iron. And so 38 isn’t just for doing what I like; it’s for trying new things. It’s for adventures, whatever small adventures I can have while my kid is still small.

38 is learning new things. I now know, for instance, that excavators have different types of attachments (thank you, small child who loves construction equipment and well-stocked children’s section at the library) and what the names of those attachments are. 38 is also the year I finally learned how to run a cash register, which I somehow avoided truly doing or understanding until now. And it is also appreciating old things anew. Every book I remember or reread now that has a mother in it, I read with fresh eyes, and I suspect I always will. Motherhood changes you, as many things do, but perhaps more irrevocably than most. I think a lot about my mother and her mother, and all the mothers before them and wish I could talk to them about what 2.5 year olds are like.

38 is the age my mom was when she thought she was 36. I was eight or nine and I told her she was wrong, wrong, wrong, and we counted up, and I was right. 38 is the age I am now, though I sometimes forget that.

38 is seeing all these movies I’d like to watch and knowing that I’ll never get to watch them with my grandmother. It’s being so glad she lived long enough to meet my son but heartbroken that they only got nine months of each other’s company.

38 is looking around at my house and the fifteen trees on my property and knowing that I chose a good place, one I hope we won’t leave for a long, long time. I’ve never lived in a house for more than four years in my life. 40 is the year that will change. At 38, I’m looking forward to that. 38 is feeling steady, feeling unshakeable, feeling secure.

38 is caring more for my son than I thought it was possible to care for another human being, ever, and simultaneously knowing that for him to succeed, I have to, too. 38 is getting ready to see what that means. Sometimes it’s staying in at night and snuggling with him on the sofa before bedtime. Sometimes it’s hiring a babysitter to do that so I can go out and listen to music and drink beer. Sometimes it’s wishing I’d done one when I’m doing the other. 38 is know that it doesn’t matter, though, because I can do it differently the next time, because screwing up isn’t the end of the world, because mistakes are there to be made. Fail. Try again. Fail better.

38 is flying.

June 13, 2014

One Year of Self-Publishing

Update: My friend Greg Bales reminds me that you don’t need an agent to get a good editor. NB: He’s a great editor!

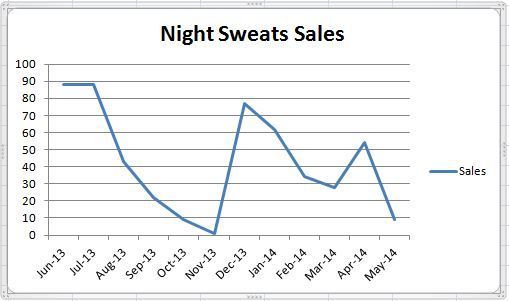

One year ago today, my self-published memoir went out into the world. Since then, it’s been purchased by 515 people or entities (60+ of those are libraries). Since I published it really just so that family and friends could get copies, I’m rather stunned and flattered.

I have done very little to promote the book but have been fortunate to have several strokes of very good luck, as you can see from the graph above. There was an initial rush when I first put the book out and my friends and family and the first few libraries bought it, and then, as you would expect, there was a rapid downward trend. The next two spikes on the graph are the result of Will Manley’s column in Booklist and my piece in the New York Times. I still have no idea how Manley heard about the book (although I know many of the people who have written reviews of it, he is not one of them), nor do I have any insight into how to get one’s writing accepted for publication, other than the usual chestnuts of reading the publications you submit to and then submitting writing to them.

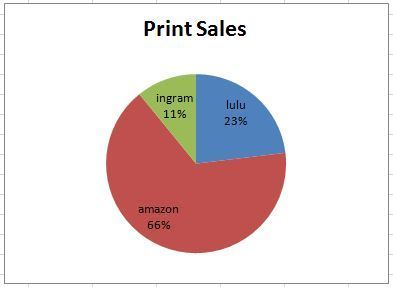

Those 515 sales represent 312 print books and 203 ebooks. The only piece of advice I can offer about selling books, at least based on my numbers, is that it’s useful to have your book available through Amazon, in whatever format.

It is ridiculously easy to buy things through Amazon, and it’s apparently (or so I am told; I’ve only ever purchased one) especially ridiculously easy to purchase Kindle books. My sales numbers would seem to bear that out. A few people purchased the epub through Lulu, and an even smaller number apparently bought it through the Nook store, but Amazon’s Kindle store is by far the big winner.

It is ridiculously easy to buy things through Amazon, and it’s apparently (or so I am told; I’ve only ever purchased one) especially ridiculously easy to purchase Kindle books. My sales numbers would seem to bear that out. A few people purchased the epub through Lulu, and an even smaller number apparently bought it through the Nook store, but Amazon’s Kindle store is by far the big winner.

In print, the book was initially only available through Lulu. It took a few months for it to get to Amazon, and Lulu only began offering distribution to Ingram a few months ago. It’s possible that the Ingram sales might be larger had that option been available earlier, but, again, I’m guessing Amazon would still take the cake.

I would not recommend self-publishing if you want to get rich. Then again, I’m pretty sure no one really recommends traditional publishing as a way to get rich, either. Very few people, relatively speaking, make a living from writing books. I was all on fire about self-publishing (or perhaps I was all defensive about self-publishing) when I started out on this adventure. I look at my book now and realize it could have benefited from further editing. But I lacked both the patience and the courage to pursue an agent — if I hadn’t hit Publish the day I did, I’m pretty sure it would not have happened at all.

I enjoyed the process of putting it together. I like learning things, and, as it turns out, I enjoy typesetting and copyfitting. I have excellent book The Librarian’s Guide to Micropublishing to thank for everything I know about doing that. I’ve enjoyed being able to send some money to Our Bodies, Ourselves, and of course I have not been opposed to earning some money myself. Money is not everything, but it is very, very helpful. And I remain proud of the little book I produced, despite its flaws, or maybe even because of them. It is, as it was always intended to be, a document of a very particular time in my life, a time that was, as Euripides once wrote of the powers of the gods, most terrible and most wonderful. Thank you to everyone who has shared it with me.

June 10, 2014

An Open Letter to W. Bradford Wilcox, Robin Fretwell Wilson, and the Editors of the Washington Post

Dear Mr. Wilcox, Mrs. Fretwell, and Editors:

I am writing to ask for your advice on how I might go about getting married. I’ve just learned that, as an unmarried woman, I’m at increased–one might say terrible–risk for sexual assault. Since I’m also the mother of a small child, I’d like to make sure I minimize the risks to myself, and to my child, as quickly as possible, and according to your op-ed of June 10, the best way for me to do that would be to get married. The subheadline even proclaims that “#yesallwomen would be safer with fewer boyfriends around their kids.” [Note: the original subheadline actually read “the data show that #yesallwomen would be safer hitched to their baby daddies.”]

Clearly you have the data on your side. Indeed, you’ve convinced me with your links that not only am I unsafe as an unmarried woman; my child is at risk, too. I’d like to end that situation for both of us as soon as possible, but I have one problem: how do I go about getting married?

Let us set the stage here a bit. I’m a 38-year-old heterosexual* white female with two masters degrees. I live in a community with excellent schools and a low crime rate. People tend to assume I’m married. Just this morning the dental hygienist asked what my husband did. A medical assistant once asked me if she could just put husband on her form, because my situation sounded “too complicated.” (I assume “baby daddy” was not in her drop-down menu.) My child’s father and I are friends but we do not live together and we never have, and we have never married.

I suppose the obvious answer might be that I should marry him, since we have a child and we get along, but, you see, I’ve asked him if he wants to get married, and he said no, so that’s out. As a WASP (well, mostly–there’s Native American blood on my father’s side and Jewish blood on my mother’s), I wasn’t raised in a culture that does arranged marriages, so I’m not in a position to ask my parents to find a husband for me. (Actually, my mother would also like your advice on how to get married in order to protect herself. She was widowed 33 years ago and thus also raised me mostly as a single mother.)

The obvious answer to my problem would seem to be that I should date, but I’m concerned about that, because it sounds as though having a boyfriend would create enormous risk for both my child and me. The report you quote notes that “only 0.7 per 1,000 children living with two married biological parents were sexually abused, compared to 12.1 per 1,000 children living with a single parent who had an unmarried partner.”

So I’m stymied, and I’m asking for your advice. How do I find a husband without first finding a boyfriend? Should I have accepted the one proposal of marriage that I did once receive, from a man outside the Omaha, Nebraska Greyhound station when I was nineteen? He approached and asked me if I was married, if I spoke English, and if I would like to get married. I said no and yes and no. Was that the wrong thing to say?

I would very much appreciate any assistance you might give. With a toddler and a full-time job, I don’t have a lot of time to date anyway, and clearly if I could just skip that step and go right to getting married, we’d all be better off. (At least I think so–your studies don’t seem to indicate what the risk factors are for a child living in a home with a nonbiological parent that their biological parent is married to, only those for when the parent in question is living with someone they aren’t married to.) Or, of course, I could just go on being single. It seems to have worked for us so far, but I hadn’t been aware before of the terrible dangers I was facing.

I understand that you have busy jobs and lives yourselves, but if you could help me out here, I would be be forever in your debt.

Sincerely,

Laura Crossett

*For the sake of brevity, I’m not even addressing here what the situation might be for unmarried homosexual, bisexual, or transgender women, many of whom do not have the option of getting married even if they have a partner and would like to do so.