Laura Crossett's Blog, page 7

January 15, 2017

I’m Not Sure We’d Be Speaking #52essays2017 no. 3

The author and her father.While I miss him daily, I often reflect that it’s just as well my father isn’t around to discuss politics with me. While other people have to deal with the reality of family members who voted for Trump, I have only to deal with a ghost, one whose intentions can be guessed but never known. But I have a pretty good idea, more’s the pity.

The author and her father.While I miss him daily, I often reflect that it’s just as well my father isn’t around to discuss politics with me. While other people have to deal with the reality of family members who voted for Trump, I have only to deal with a ghost, one whose intentions can be guessed but never known. But I have a pretty good idea, more’s the pity.

It’s one thing to stand for three days beneath the American flag at the college where you teach to prevent students from turning it upside down. I respect the man for that, even though I disagree, and though I would have, as I told my mom when I first heard this story, probably been one of the people trying to turn the flag upside down. (“You and your father would have disagreed on a lot of things,” she said. “Call me if you need to be bailed out. I was on my way to an anti-war march.)

But it’s quite something else to suggest that the Republican party needs to adopt the techniques of the civil rights movement and find its own James Meredith, as my father suggested in a memo to the state Republican party in the mid 1960s. I felt ill reading that memo last year in the basement archives of the college where he taught (the same as the flag incident college). I feel ill writing about it now. But he said it, there in black and white.

Several years ago I resolved to stop writing things about or for Martin Luther King Jr. Day, in part out of embarrassment at what I’d written before and in part for the real and good reason that white people, myself most definitely included, need to talk less and listen more. I’m breaking that promise now, and in the worst way possible, opening a remark about MLK with an image of my racist father. But then it’s my father I’m writing about, really, not Dr. King. If acknowledging one’s own racism is the first step in being a good ally, then surely reckoning with the racism of one’s forebears is part and parcel of that.

I’m not sure how much help it is, though. Anything I start to write is too easily contestable by those who knew him and who might well hold a different impression of the man, about whom I have heard little but good in the years since he died. But not entirely, for which I’m grateful.

I’ve been told, for instance, by multiple sources that he believed the best man would always beat the best woman. If Billie Jean King won anything, it must have been because she wasn’t actually facing the best man. (He was a tennis player and would doubtless have had an informed opinion on this, even if it was wrongheaded. I know King only as a cultural icon and have no ability to pass judgment.)

But then I’ve also been told that he was deeply and profoundly upset by anti-Semitism in any form, despite what we would now term his own anti-Semitic microaggressions, usually in the form of commentary on NPR reporters. For years I clung to this as a sign that he wasn’t completely given over to the dark side: as long as you think Hitler is evil, you can’t be all bad, right?

But what I’ve learned — in part from trying to listen more than I talk, which isn’t a strong point of mine, as this essay demonstrates — is that one good instinct does not a good ally make, or even a potential one.

So it’s just as well, I think, that I can’t talk to my father about the presidential election. Still, though, I wish I could. Because the other thing I know — from listening, from reading, from writing, from life — is that one’s lived experience rarely fits neatly into a paradigm not matter what your political affiliation. Blood, in my case, runs thicker than the bully pulpit, and I’m willing to forgive a lot in the people I love. In real life, I’m not called upon to do so much, as my family and friends largely inhabit the same bubble I do. I often say that if my father were alive, I’m not sure we’d still be speaking. But I never stop wishing we could.

January 8, 2017

Nightmares #52essays2017 no. 2

“A Dream” from the Internet ArchiveI am alone in a grassy valley, and a train car carrying all of my family and friends is pulling away from me up the hill. I try to run after it, but I can’t catch up. No one hears my cries. Around me there is nothing but miles and miles of grass and hills, no sign of human habitation — “Christina’s World” without the barn; the sunset in My Antonia without the plough — nothing. I am all alone.

“A Dream” from the Internet ArchiveI am alone in a grassy valley, and a train car carrying all of my family and friends is pulling away from me up the hill. I try to run after it, but I can’t catch up. No one hears my cries. Around me there is nothing but miles and miles of grass and hills, no sign of human habitation — “Christina’s World” without the barn; the sunset in My Antonia without the plough — nothing. I am all alone.

I have other recurring nightmares, the same kind everyone has—the exam where you’ve never been to the class; the public event where you are naked; the one where you try to run but are frozen in place — but none has the force of that earliest nightmare I remember. I realized the source of it earlier this year while reading to my son. My mother had found my very favorite Little Golden Book, one from her own childhood called Gaston and Josephine about two rosy French pigs who go on a trip. On one page, they too get off a train for a bit of fresh air and the train pulls away, leaving them in the blue grass. In the book they are soon found by a friendly farmer, but my dream never left that page. I was all alone forever. That the source of my nightmare could come from a source of delight shocks me. I loved that book, whose pictures I would describe as gay—gay in the sense of bright and cheerful, back before we had that word to denote a sexual orientation.

But nightmares are funny that way.

Recently my son built a nightmare catcher: a quarter cup measure tied to the banister with a piece of string. He swings it each night to catch any errant nightmares that might be roaming around, catch them and trap them before they can get to him in his bed. But still he worries that a nightmare will come.

“I’m thinking about a nightmare,” he will say to me as he lies in bed. “Let’s think of something happy!” I tell him with forced cheer. “Like ice cream or scooter rides or Paw Patrol!” ??”I can’t think of anything but a nightmare!”

?That is how they work, is it not? When our minds can think of something else, we no longer have the nightmare. We lucidly dream, and the bad things go away.

A nightmare used to mean a real thing, or real as the people writing of it understood reality. “A female spirit or monster supposed to settle on and produce a feeling of suffocation in a sleeping person or animal” is the earliest definition given by the Oxford English Dictionary. Of course it was a female spirit, I think. When has mythological evil ever been male. Also fig. the definition continues. It’s two hundred years before the monster drops away and it simply becomes a bad dream, one that merely makes you feel strangled.

I don’t feel strangled in the dream on the grassy hill, though sometimes I am out of breath from running. Often I realize I will die on that hill, quite literally. There is no food, no water. The train is gone and there is not another one coming. I can walk along the track to try to get to wherever the train is going, but I know in the dream I will not make it. The distance is too far. The sun is too hot—it’s always a sunny hot day in this dream. I will be dead. It’s hard to say which is the more frightening: the fear of abandonment or the fear of death. My dream contains both.

I do no know when I started having this dream. We read the book early on, but when it lodged in my brain is another question. It would be tidy to say the dream began after my father died, or maybe it would be tidy to say it began before, that I had in my child’s brain a premonition.

In a few months my son will be the age I was when my father died. I’ve often been told by well-meaning people that I must not remember my father, and that therefore it must not bother me that he is dead. In fact I remember my father quite well — the way he wore his hat, the way he drank his whisky sours. If I were to die now, what memories would my son carry of me? What dreams would he have, and what nightmares would stay with him?

I hope against all these things, of course. I hope the nightmare trap will work, that the evil spirits, female or otherwise, will get caught in that old tin quarter cup measure and not make it up the stairs to where my baby sleeps. But I know it’s a poor thin sort of protection.

January 1, 2017

The Things of the Dead #52essays2017 no. 1

I’m doing this #52essays2107 challenge. This is the first one.

Perched Rock from the LACMA.I am 41 years old and I have not yet learned that the dead no longer inhabit the objects they leave behind. My father’s body is no longer in his shirts, nor does his breath flow through his pipes. He no longer reads his books nor sits in his chair nor hangs knives from the knife rack he made that fits nowhere in my house but that I keep just the same. He does not mix drinks with the jigger that I don’t use.

Perched Rock from the LACMA.I am 41 years old and I have not yet learned that the dead no longer inhabit the objects they leave behind. My father’s body is no longer in his shirts, nor does his breath flow through his pipes. He no longer reads his books nor sits in his chair nor hangs knives from the knife rack he made that fits nowhere in my house but that I keep just the same. He does not mix drinks with the jigger that I don’t use.

The one remnant of him that lives is his voice, but it is locked away somewhere in a backpack full of reel to reel tapes I can’t play, tapes that may well, in the 36 years since he died, have disintegrated completely, so that I am carrying around a backpack full of nothing. He and I used to play a game about that—we each carried a bag full of nothing, and we were gleeful over how big our bags were. I did not know that my bag would someday fill with all the things he left behind, things I hoard even though they serve no purpose.

I come by this tendency honestly. My grandmother carried her checks in a holder with a picture of her dead father in a photo sleeve on the outside. My mother carries it now. I carry my grandmother’s cigarette case (I store credit cards in it) and wear my great grandmother’s ring. Those things at least we use. My office is piled high with my great-grandfather’s rock collection, and our house is full of boxes of papers from my grandmother’s house. To give you an idea of their value, one turned out to contain a folder labeled “Receipts—Toss.”

My grandmother never got a diagnosis as such but was likely a hoarder in the clinical sense of the word, especially with pieces of paper. The maxim that you should handle no piece of mail more than once was lost on her. Most of them got handled eight or ten times, or, more likely, piled in a pile to be dealt with later. I still remember her sitting at her dining room table, extended to its full length with leaves, sifting through pile after pile of paper looking for her property tax bill, which she hadn’t paid. She had, at least, opened the letter that said they were putting her house on the market in fourteen days if she didn’t fork over the cash.

On one of the last weekends we all gathered as a family at her house, she set my cousin Jennifer to alphabetizing her catalogs. Some were more than a decade old—the LL Bean Christmas catalog from 1994 was among them, as I recall. Jennifer looked at the catalogs, looked at me, and said, “Laura, could you do me a favor? It’s eleven o’clock in the morning, but could you go to the kitchen and get me a beer? Because I don’t think I can do this without one.” I got one for her and one for me, and we set to work.

We moved my grandmother out of her house eventually and into a one-bedroom apartment at a retirement place, but the problem continued. I used to say that getting her a printer was the worst decision we ever made, though I contributed to it, buying her a multifunction printer/coper/scanner exactly like mine so I could help her troubleshoot it over the phone. She printed out recipes and articles and movie reviews and the prices of books she owned as collected by AbeBooks and Powell’s and bookfinder.com. She was convinced her first editions would net us a fortune and always believed the highest price listed was the one we’d get.

It was maddening, and yet I loved her. I loved her even when, when visiting, I could not find a place to sit down and had to move treacherous piles of paper from the sofa to the floor in order to have a place to sleep. I loved her even though she’d never let me help—or not really. She was happy to accept help she got to delegate, so you could sort by year or alphabetize to your heart’s content (after you wiped down the corner of the table you’d just cleared so you’d have a space to sort on), but there was no wholesale tossing or recycling of the sort we all desperately longed to do. Those pieces of paper were as valuable to her as her checkbook with her father’s photo, as her mother’s ring (the one I now wear), as the china bouquet in her glass topped coffee table that came from the Chicago World’s Fair.

I suppose if I were to cling to my grandmother for real, I would keep all those scraps of paper—the movie reviews (she was always hoping to improve the selections for the movies at her retirement home), the book prices, the articles, the magazine clippings, the ancient catalogs, the piles and piles of Sunday New York Times crosswords waiting for their final clues. And indeed, sometimes when I find one, I am tempted, especially if it has her handwriting on it, writing like no one else’s.

But for all that I loved her, I am trying not to become her. So I let them go. But I keep the rocks.

October 23, 2016

An Introduction to Sara Paretsky

Long-running female detective story author Sara Paretsky of Chicago poses for pictures under train tracks in Hyde Park, Thursday, January 12, 2012. (Alex Garcia/ Chicago Tribune)Sara Paretsky received the Paul Engle Prize, awarded by Iowa City UNESCO City of Literature and sponsored by the City of Coralville a little over a year ago. After the award was granted, she was interviewed on stage by NPR book critic Maureen Corrigan at the Coralville Public Library.

Long-running female detective story author Sara Paretsky of Chicago poses for pictures under train tracks in Hyde Park, Thursday, January 12, 2012. (Alex Garcia/ Chicago Tribune)Sara Paretsky received the Paul Engle Prize, awarded by Iowa City UNESCO City of Literature and sponsored by the City of Coralville a little over a year ago. After the award was granted, she was interviewed on stage by NPR book critic Maureen Corrigan at the Coralville Public Library.

Here is the introduction I wrote for her.

“Every writer’s difficult journey is a movement from silence to speech.”

This weekend marks the end of Banned Books Week, the time each year when we librarians stop to call attention to the books that someone, somewhere, doesn’t want you to read. If you stopped at our display near the front desk, you’ll see some of the more frequently challenged books there, along with the reasons they’ve been challenged—they use bad words, or they talk about sexuality, or they express unpopular political opinions, or they encourage witchcraft. Frequently these are books for young people, because it is young people whose exposure to ideas we seem to worry the most about.

Sara Paretsky was lucky to grow up in an environment where books were encouraged—in fact, her mother later became a children’s librarian—but she also grew up in a time and in a household where women were not supposed to get ideas. Though her parents paid to send her four brothers away to school, they told Paretsky that if she wanted to go to college, she’d have to do so in state, and she’d have to pay for it herself. She did, earning a BA from the University of Kansas and eventually a PhD and an MBA from the University of Chicago. Though she’d written privately for years, it wasn’t until she was working in the insurance industry in Chicago in 1978 that, during a meeting with an executive she began thinking of all the things she’d like to say but couldn’t—and V.I. Warshawski was born. Indemnity Only, her first novel, written at nights while she was still working full time, was published in 1981.

She has since written sixteen more novels in the V.I. Warshawski, plus several standalone novels, short stories, and a memoir in essays called Writing in an Age of Silence. Paretsky’s work has garnered both critical and popular acclaim for nearly three decades. Among her many awards and honors, she was named Ms. magazine’s Woman of the Year in 1987; she received Mark Twain Award for Distinguished Contribution to Midwest Literature in 1996; the Gold Dagger from the British Crime Writers in 2004; and the Grand Master Award from the Mystery Writers of America in 2011. She holds honorary doctorates from MacMurray College and Columbia College, Chicago. After remarks she made in 1986 about the way women in many crime novels were treated and the paucity of reviews of books by female mystery authors set off a firestorm, she became a founding member of Sisters in Crime, the now worldwide organization for women crime writers.

With such a long list of publications and accomplishments, it is hard to think of Paretsky as ever being silent, or ever being silenced. “Every writers difficult journey is a movement from silence to speech,” she wrote in her 2007 essay collection Writing in an Age of Silence. “We must be intensely private and interior in order to find a voice and a vision—and we must bring our work to the outside world where the market, or public outrage, or even government censorship can destroy our voice.” Paretsky has had experience fighting all three of those forces of silence, both for herself and on behalf of others.

The Library Bill of Rights notes that “Libraries should challenge censorship in the fulfillment of their responsibility to provide information and enlightenment” and that “Libraries should cooperate with all persons and groups concerned with resisting abridgment of free expression and free access to ideas.”

We are honored tonight to welcome Sara Paretsky, author, activist, and ally in the ongoing fight for free expression.

October 16, 2016

If there is a bear: Dr. Gordon Mixdorf, In Memoriam

I thought Dr. Mixdorf was rather grouchy when I first met him. Grouchy and a hardass. I had him for American Studies II my freshman year of high school and I couldn’t really figure him out. He had an impressive agenda–he taught us about institutionalized racism and union history, topics not often addressed in general high school American history classes then or, I suspect, now–but he often seemed humorless. Then again, I thought, who wouldn’t be if they had to teach American history from that godforsaken book with the sunset and the Statue of Liberty on the cover? One day, though, I was walking out of class when he stopped me. It was late 1990 or early 1991, the lead up to the “first” Gulf War, and I was wearing my black armband with my all time favorite button that read “Are you willing to die for Exxon?”

“Nice button,” he said.

Two years later I had him again for AP Government. The first day of class he assigned us a ten page paper due in a week. My topic was reapportionment and redistricting–topics I’m fascinated by to this day. The day we turned in that paper, we got another assignment–another ten page paper, and a 20 minute presentation, this time with a partner, due in a week. I went to the University of Iowa libraries with my partner Laura to read up on Rousseau. We were so overwhelmed by the library that we spent most of our time at the photocopiers, madly making copies, as we couldn’t check books out.

Things never slowed down much after that. Somewhere I still have the set of drawings Amy made for me of our year in AP Government, which features coffee (which I think we all learned to drink that year), stacks of papers, bad grades we mourned, good grades we were proud of, and “a bed that was never slept in.”

I didn’t much like high school, but for 53 minutes (really more like 50, since I was late every morning) at the beginning of every day of junior year, it wasn’t so bad. Our textbook was written by a James Q. Wilson, and at the end of the year Daw-An made us all JQW tshirts–“outdoor gear for the rugged individualist.” We read the Articles of Confederation and the early constitutions of New York and Virginia. We gave a lot of oral reports, and thus I got a line I still use today when Dan said, “The minority whip is a man named Newt Gingerich, whom my father describes as somewhere politically to the right of Darth Vader.” I got sick of doing straight reports at some point and so instead wrote a play about Harry Truman and the steel mill seizure, complete with a “To seize or not to seize” soliloquy, and I made everyone in class take a part. Dr. Mixdorf tolerated that and even dealt graciously with my argument about why I should get a better grade on a paper comparing Japanese and American political cultures in which I quoted Pretty Woman.

He showed us a documentary about the campaigns of Ronald Reagan, which is where I first learned about focus groups. When they showed the Reagan bear ad, which concludes, “Isn’t it good to be as strong as the bear?” Dr. Mixdorf intoned, in a perfect stage whisper, “If there is a bear?”

Down Becca Down Brownies I made with my son tonight.I made brownies for that class for some occasion or other that I no longer remember. I’d set them out on the table in the middle of the room where Dr. Mixdorf kept copies of the New York Times and the Wall Street Journal in the vain hope that we’d read them. He mentioned there were a few brownies left and then, as Rebecca started reaching for one before he’d finished, said, “Down, Becca, down!” They’ve been called Down, Becca, Down Brownies ever since.

Down Becca Down Brownies I made with my son tonight.I made brownies for that class for some occasion or other that I no longer remember. I’d set them out on the table in the middle of the room where Dr. Mixdorf kept copies of the New York Times and the Wall Street Journal in the vain hope that we’d read them. He mentioned there were a few brownies left and then, as Rebecca started reaching for one before he’d finished, said, “Down, Becca, down!” They’ve been called Down, Becca, Down Brownies ever since.

As the other Laura said earlier today, Dr. Mixdorf made you want to work hard and do well, and that’s a rare quality in anyone, particularly in a high school teacher.

Dr. Mixdorf died two weeks ago, and I made a version of this post on Facebook. I was astounded not so much by how much I remembered (before I got knocked up, I used to remember everything) but by how much of my AP Gov class of thirteen I was still connected to in some way. A year or so after we graduated, a bunch of us got together while we were home on winter break to watch the movie The American President and go out for ice cream and coffee afterward and talk about the movie and college. I don’t remember if we talked specifically about Dr. Mixdorf and how much he taught us, but surely we should have. I am sorry now that I never had the chance to tell him.

Down Becca Down Brownies

Essentially, these are the recipe for brownies on the back of the chocolate box, plus an egg.

4 oz. baking chocolate

1 1/2 sticks butter

2 cups sugar

4 eggs

1 teaspoon vanilla

1 cup flour

Melt the chocolate and butter together. Combine all the other ingredients in a bowl and pour into a greased square baking pan. Bake about an hour at 350 degrees. Cool slightly and eat as soon as possible.

September 23, 2016

An Introduction to Marvin Bell

Occasionally I am called upon to write–and sometimes deliver–introductions to authors. I’m rather fond of some of them, and so I’ve decided to start publishing them here.

Marvin Bell at the Coralville Marriott for the Coralville Public Library

23 April 2015

World Book Day

Marvin Bell in a hat. Photo by Sam Roxas-Chua.

Marvin Bell in a hat. Photo by Sam Roxas-Chua.In 1977, the place where we stand now was a sort of wasteland, a mostly blank spot on the map with a few houses along the edge of the river and a little light industry. I was a toddler, and my mother was a graduate student in the English department at the University of Iowa, and her dissertation director, Paul Baender, sometimes played chess with a poet on the faculty of the Iowa Writer’s Workshop who had just published a book called Stars Which See, Stars Which Do Not See, which included a poem called “To Dorothy.”

A couple of decades later, that poem inspired a sculptor named James Anthony Bearden to make a sculpture, commissioned by the City of Coralville, for a sculpture walk at the recently built Iowa River Landing, built on the site of that former wetland wasteland, which now housed this fancy hotel and a library of books by graduates and faculty of the Iowa Writers Workshop. I grew up to become a librarian at the Coralville Public Library, and one day I wrote to the poet asking if he might come and read and speak a little bit about his work.

That poet was Marvin Bell.

Marvin was a long term member of the Iowa Writers Workshop faculty and served two terms as Iowa’s first poet laureate. Of his twenty-three books, recent titles include Vertigo: The Living Dead Man Poems and Whiteout, a collaboration photographer Nathan Lyons. After the Fact: Scripts & Postscripts, a collaboration with Christopher Merrill, will appear in 2016. He lives in Iowa City and Port Townsend, Washington and teaches for the brief-residency MFA based in Oregon at Pacific University.

In an interview some years ago, Marvin noted “that it’s ultimately pleasanter and healthier and better for everyone if one thinks of the self as being very small and very unimportant. … And I think, as I may not always have thought, that the only way out of the self is to concentrate on others and on things outside the self.”

Art can bring us to that focus, as can time. 3800 years ago this spot was a campsite. In 1864, the naturalist Louis Agassiz gave a talk called “The Coral Reefs of Iowa City” that gave Coralville, founded in 1873, its name. In 1964, the space where we stand now was barren. A girl scout troop held a bake sale to raise funds for a library in Coralville, Iowa, and my parents met, and the sculptor James Anthony Bearden was born. This year the Coralville Public Library celebrates its fiftieth anniversary. And throughout all that time, Marvin Bell has been writing poems: poems that recognize the world around us—the mulberry trees, the heat of summer, the light of the moon—and our history, from the Holocaust to our current wars, and our relationship to those around us, the living and the dead. Many years from now, we cannot guess what this place will hold, but the people here will still be reading poems. We are deeply pleased and honored to welcome Marvin Bell here tonight.

September 9, 2016

Welcome, Mutha Readers!

If you’re here, perhaps it’s because you read my essay The Family Bed on the wonderful Mutha Magazine. I write and blog, shall we say, infrequently, but if you’d like to read more, here are a few things I’m particularly proud of.

My son with the eggs he was moving “very, very carefully.”

The Psych Ward, 10 Years Out — on why I vote in every election

An Open Letter to W. Bradford Wilcox, Robin Fretwell Wilson, and the Editors of the Washington Post — my response to a particularly obnoxious op-ed

Control — the piece that became the prologue to Night Sweats

On Listening to Ani Difranco — self-explanatory, I think, if you were a young woman in college in the 1990s

The Medium is Not the Message — which won an award from the Electronic Frontier Foundation many years ago

Thanks so much for stopping by!

March 6, 2016

Picture Window

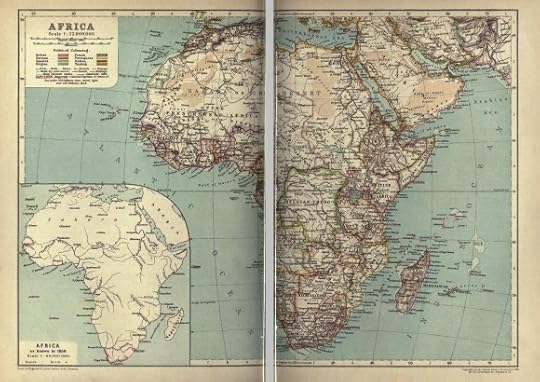

Map of Africa from the 1911 Enyclopaedia Britannica [source]

This is an old, old essay from my MFA thesis, posted in honor of the Shelter House Used Book Sale, happening again today from noon to 4 pm at 1925 Boyrum Street in Iowa City. Many of the books mentioned below are for sale there, as well as many other books you might actually want to read. Every kid who goes gets a free book, and proceeds go to support services for the homeless in Iowa City.

For four years, from third through sixth grade, I lived with my mother and our cat in a brown shingle house tucked far to the back of its lot on a side street near a large park in our small midwestern city. The house was an ordinary split level, ugly and unprepossessing, with a sad band of trees planted haphazardly in its yard: a tilted Russian olive, a sinking willow, a nearly barren pine, trees I climbed and sat in and put stones around, even in their brokenness. The house’s chief feature, and the reason that my mother bought it, was that in back, opening out from the living room, there was a library, added by the house’s previous owner, a lawyer, who moved out when he needed even more room for his books.

Although we gave away 108 boxes of books to my father’s former students and colleagues shortly after we moved in, we still had over 2000 volumes, which is what you get from the marriage of two Ph.D.s with eighty years of book-collecting between them.

My mother kept fiction and children’s books in the living room, and sci-fi novels in her room, but the mass of books was in the library.

The library had greenish-blue industrial carpet and a sloped ceiling. The wall on its higher side was made of bookshelves, and the wall on the lower side was dominated by an enormous picture window.

Out the window you could see our yard and into our neighbors’ and almost all the way to where the street dropped off into a sudden ravine. Over the years, fueled by enthusiasms from reading A Girl of the Limberlost and Gerald Durrell’s The Amateur Naturalist, I learned the rocks and plants and birds outside—shale and limestone, columbine and yew and wild rose, cardinals and chickadees and mourning doves with their low, insistent notes.

I spent a lot of time in this room, often looking out the window instead of doing math homework or practicing viola. But, especially as twilight darkened the window so that it reflected the space in time, my attention turned to the other wall, too, to the shelves and shelves of books.

They were arranged, I now realize, by the Library of Congress system, by genre and nationality and century. The volumes were elegant, many of them hardback, black or grey or blue or olive green or, occasionally, red, with gold leaf and lettering on their spines. The titles and the covers o f these books were as much a part of my landscape as any living aspect of the natural world: The Oxford Book of English Verse, Boswell’s Life of Johnson, Studies in Words, De Boetheius, The Oxford Book of Greek Verse, and its companion, The Oxford Book of Greek Verse in Translation, The Imitation of Christ, The Vagabond Scholars, The Greek Stones Speak, The Faerie Queene, and, at the bottom, the twenty-odd volumes of the Encyclopaedia Britannica from 1911. Unlike the World Book at school, these encyclopedias, though alphabetical, were not separated a letter at a time, but in groups — ITA to LOR, one was called, LOR to MUN, MUN to PAY. I often pulled them out so I could wonder at their tissue-thin pages and unfold with care their delicate and ancient maps, as if they might hold some key to these lost worlds, these foreign words.

* * *

When people asked me what I wanted to be when I was a kid, I said a naturalist and a writer, which produced a certain degree of puzzlement, the latter being an impractical career and the former an obscure one. One could be a journalist or a scientist, but the desire simply to study nature and write of what you saw was, I suppose, peculiar.

The belief that nature has something to teach you, and that you can start from scratch, with the world around you, is as arcane to the world of science as the notion that you can read literature without theory is to the world of letters, but it was not always so. When Aristotle w anted to know how many teeth a horse had, he went out and counted them. That later generations took his word for it seems to me a sign not of progress but of an appalling lack of curiosity. Book-learning may help me identify the species of a bird or the meter of a poem, but what the bird and the poem have to teach me they will do themselves.

In college I was technically a Classics major, but I spent a great deal of time in the eighteenth century. It was an age that seemed to have much that the present one lacks. They all read Latin and Greek, they had intelligent and witty conversations, they never tolerated a fool, and even when they were angry, they were very, very elegant. But, most appealing of all, they seemed genuinely interested in human nature and natural law. All the men I read seemed to be natural philosophers — natural both in that they were observant of the ways of nature and natural in that their observations seemed to come from them, not through any critical or sociological theory. I read Hume on natural religion, Rousseau on man in a state of nature, and Montesquieu on natural law, and I wrote an entire term paper

on American natural history of the eighteenth century, when everyone was trying to figure out the nature of the New World, its new governments, and what Crevecoeur called “this American, this new man.”

But I also learned -— or was told -— that by and large, these men got nature wrong. Their ideas of order and equality left a lot of people out -— had I been around at the time, in fact, they would have excluded me by mere fact of my sex. Rousseau, that great proponent of noble savagery, had no desire to live amongst the “savages” himself, and abandoned his illiterate wife and five children to schmooze with the upper classes. Benjamin Rush, an American physician much enamored of Enlightenment philosophy, believed that black skin was a disease of the moral faculty (located, he posited, in the spleen), though by selective breeding, it might eventually be possible to purify the morals and thus lighten the skin. That phrase that Thom as Jefferson so charmingly altered to “the pursuit of happiness” was still understood by all to mean what John Locke had originally written, “the pursuit of property.” The prescription for manifest destiny and destruction was carved on the cornerstone of the country, and much of it, I was told, came from pondering not only nature but also the very books I had stared at in the library as a child.

Somehow, it seemed, I had horribly misread the words and the world. Growing up in that space where art and nature met had made me want to plunge more deeply into each. Apparently others were similarly impelled, but for them that plunge meant drilling for oil in the wilderness and arguing for the advancement of one group of people by the oppression of another. The effect was something like that of learning you and your worst enemy share a common ancestor or a fondness for the Gospel according to John -— yet it makes sense in a way, for what is enmity if not a belief that someone else is perverting that thing which is dearest to your heart?

Lately I have been reading Longinus, the first century AD rhetorician, in a translation with commentary done by my father and his former student and colleague, James Arieti. His chief work is On the Sublime, a treatise on composition that deals explicitly with questions of art (or technique, as my father and Arieti translate it) and

nature. Are poets born by nature or made through technique? An old question. Both, says Longinus: without nature, art would have no substance; without art, nature would have no form.

Always I find myself back in the library at dusk, watching the world as it fades and then reappears, as the trees turn to books and the leaves to words printed on a page. Always I remember searching for smooth flat black stones to place in a circle on the ground beneath a tree, and lying on the ground to listen and feeling something listening back. Always I remember the night my m other turned to the shelf, pulled out a volume, and read to me from Richard Hooker, Of the Laws of Ecclesiastical Policy.

Now if nature should interm it her course, and leave altogether though it were but for a while the observation of her own laws; if those principal and mother elements of the world, whereof all things in this lower world are made, should lose the qualities which now they have; if the frame of that heavenly arch erected over our heads should loose and dissolve itself; if celestial spheres should forget their wonted motions, and by irregular volubility turn themselves anyway as it might happen; if the prince of the lights of heaven, which now as a giant doth run his unwearied course, should as it were through a languishing faintness begin to stand and to rest himself; if the moon should wander from her beaten way, the times and seasons of the year blend themselves by disordered and confused mixture, the winds breathe out their last gasp, the clouds yield no rain, the earth be defeated of heavenly influence, the fruits of the earth pine away as children at the withered breasts of their mother no longer able to yield them relief: what would become of man himself, whom all these things now do all serve?

See we not plainly that obedience of creatures unto the law of nature in the stay of the whole world?

Perhaps, then, these things, this space, are more than just a hall o f mirrors, art and nature, nature and art. Perhaps they were preparing me to walk that narrow, filmy spider’s thread that connects the ages, touching mountain peaks and hidden caves, galaxies and nuclei, tangled in spots and often invisible, but ever present, just waiting for you to find it.

January 13, 2016

Love and Fate

An illustration from a book of poems called Fate in Arcadia by Edwin Ellis Downey. [source]

Five years ago I moved back to the Midwest from Wyoming. My plan was to stay for five years, or until my grandmother died, and then move on to something else. Maybe I’d move back West and get another library job. Maybe I’d move to some other part of the country I’d always wanted to live in. Maybe I’d join an intentional community. Maybe something else. The plan was hazy, except for this: Leave.Well. You know the joke about how to make God laugh, right? Make a plan. In the nine months after I moved and started a new job, I got pregnant, decided to have a kid, and bought a house. In another nine months, I had a baby and my grandmother died. And now here I am, my kid about to turn four, my house the place I’ve lived in for longer than I’ve lived anywhere in my life, and my plan, for the foreseeable future, to stay. Stay.

The very first issue — if you can call a few hundred words an issue — of The New Rambler was written just a few miles from here, in a basement apartment on Iowa Avenue, and if you can get past the philosophizing of a recent college graduate realizing that we all have to work for a living, it touches on the same panic about staying. Thank God this is a nine-month gig (in fact, I lasted only four months). Thank God I don’t have a plan. Thank God I’m not stuck here. What I remember of that time is sheer terror. Perhaps it’s no surprise that I ended up in the hospital a few weeks after I wrote those words.

The older I grow, the more I wonder if there is that much of a difference between the things we are fated to and the things we choose. I didn’t want to be born in the Midwest, but I’ve chosen to live here. I didn’t want to get pregnant, but I chose to have a baby. I didn’t want to have a mood disorder, but I’ve chosen to write about it as honestly as I can.

Oedipus — I have written about this before, and I will harp on about it until the day I die — had a fate, and he made choices he thought would help him avoid it, and instead they led him to that very thing. He chose his fate, you might say. That’s not the same as loving your fate, but maybe — if I’m right — the difference doesn’t matter so much.

Where that leaves me, exactly, I don’t know, except that almost two decades later I’m still sitting late at night typing to people on a laptop, thinking perhaps a few of them might read it. I suspect I’ll always do that, wherever I end up. And that’s something.

January 2, 2016

On Resolution

An illustration from St. Nicholas magazine, 1873. [source]

In the late summer or very early fall of 1987, my mother and grandmother took me to hear Joe Biden speak at a picnic shelter in Upper City Park in Iowa City. He was running for president at the time. That was truly a golden caucus year — Bruce Babbitt, Jesse Jackson, Gary Hart, Paul Simon, Al Gore, Michael Dukakis, and a few others listed here I don’t even remember. Biden dropped out shortly after we saw him, and my family transferred its allegiance to Bruce Babbitt, thus continuing with our long line of unsuccessful presidential candidates (Paul Tsongas ’92, anyone?). I believe Adlai Stevenson is the only guy we’ve liked who ever got a nomination. I missed the caucus in ’88 because I had strep, and I’m bummed out about that to this day, but a bunch of us at my grade school collected discarded stickers the next day and wore them around proudly till they unraveled in the wash.

But back to that evening in City Park. Biden gave a rousing speech to a few dozen people, most of them the same sort of upper middle class white professionals that we were. I remember he said damn once and changed it to darn. I remember he said every American high school student should be required to take four years of English (that got a lot of cheers). And my mother remembers that he said that even when school was boring (calculus was the example he used — sorry, mathematicians), it was still important.

In 2008, I was living in Wyoming, far from the land of the first caucus and the People’s Republic of Johnson County. I asked my mother whom she was caucusing for, and she said Joe Biden. “Why?” I asked.

“Do you remember when we went to hear him speak?”

“IN 1987???”

“Yeah. Remember how he said that education was sometimes boring but it was still important?”

“Yeah.”

“Well, that just really impressed me.”

“So you’re caucusing for someone based on a speech he gave twenty years ago… ?”

“Yes.”

I tell this story a lot because of course I love to make fun of my mother (whom I love very much), but in actuality, I agree with its message.

I never planned to have children, and thus I never imagined what I would do with a child, or what I would want to teach one or instill in him. I have my doubts about the ability of parents to teach or instill anything in their children, but if I were to pick something, it might well be this: we don’t always get to do the things we want to do. Life isn’t all about fun. You don’t always get to do what you love. And that’s okay. There’s honor and dignity and meaning in all sorts of work, even the dullest. My job is far from glamorous. Once in awhile I get to talk on TV or radio. Once in awhile I get to clean up puke. Most of the time I deal with the cash register and try to make sure the desk schedule is taken care of and handle various problems. Even the parts of my job that sound exciting are often not all that. I order all the adult fiction for my library, which sounds great (and sometimes is, because I get to buy and promote amazing books like Love Me Back and Battleborn and After Birth and Women), but mostly it means that every month I order five copies of the newest James Patterson* novel, because my job is to keep all the readers happy, not just to pander to my particular tastes.

This time of year tends to be full of people Living Their Best Life, or pledging to, and casting aside the past year and planning for only bright and shining things ahead. And that’s all great. (I have a few plans myself — they include getting all my pictures framed and hung and finding black ankle boots that fit. Check back with me in a year to see if either of these things has happened. I have my doubts.) But I often think we don’t give enough credence to drudgery and toil and even ordinary mind-numbing work. It doesn’t matter how many great ideas you have — someone still has to collect the garbage. The folks who make our clothes and gadgets — including the black ankle boots I’m coveting and the fancy machine I’m typing on — still make wretched salaries, work horrendous hours in horrific conditions, and have very little of what we all might consider life.

I was of course raised not only on speeches by Joe Biden but also — and more importantly — on literature that posited a very specific kind of world view. Laura Ingalls Wilder and Louisa May Alcott and so many of the other books I read as a child were about nothing so much as stoicism in the face of deprivation. When Pa survives by eating the candy he was going to give the girls for Christmas, or when Laura wonders if she can bring part of the orange she gets at a party home to share, as she’s never seen an orange before, or when Marmee insists they take their Christmas feast to the poor family — these things have stayed with me, even if I don’t live up to their ideals. “We must never complain. We must always be grateful for what we have,” says Ma over and over and over again. I know there’s a lot to be said against that point of view. No one should be grateful for terrible working conditions or domestic abuse or rape culture. But absent the kind of horror you can and should fight against, there’s a lot to be said for it, too.

*It’s true that Patterson gives a lot of money to independent bookstores and booksellers, including here in my town. But buying multiple copies of books whose major plots involve women getting raped and dismembered always leaves a sick feeling in my mouth. Just handling book covers of hazy women’s body parts — and there are a LOT of these, not just by Patterson — makes me kind of ill.