Amy Belding Brown's Blog, page 5

December 28, 2013

A Long Time Coming

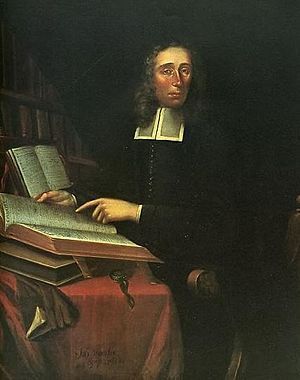

The Rev. Increase Mather, oil portrait by John van der Spriett, 1688. (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

Christmas was a long time coming to New England. It was nearly 200 years after the English Puritans settled in Massachusetts and Connecticut before people began to celebrate Christmas here in a way that we would recognize. They rejected Christmas along with most of the colorful traditions of the Anglican and Roman Catholic churches. Odd as it seems to us today, the Puritans believed that Christmas was a “pagan” holiday. They saw no evidence for it in the bible, (which does not name Christ’s birthday) and – worse – they saw it as an adaptation of the Roman festival of Saturnalia.

In England it was celebrated with drinking, gambling, feasting, mumming and wassailing. Wassailing, as practiced in the 17th century, was the custom of bursting into wealthy people’s homes, singing songs or putting on a little skit, and then demanding money, food and liquor. The line “Now bring us a figgy pudding . . . we won’t go until we get some” from the old carol “We Wish You a Merry Christmas” was intended seriously. If the wealthy homeowner didn’t oblige, the consequences were at best hard feelings, which often evolved into fist fights and rock-throwing. Mumming was another tradition, in which men and women disguised themselves in costumes which sometimes included cross-dressing. The Puritans objected because people could slip into neighbors’ houses for sexual assignations without being detected. They regarded mumming as a roving orgy.

Increase Mather, one of the most influential early Puritan ministers in Boston, condemned people for celebrating Christmas by being “consumed in compotations, in interludes, in playing at cards, in revellings, in excess of wine, in mad mirth.”

Massachusetts Bay Colony actually banned the celebration of Christmas from 1659 to 1681. Offenders who didn’t go about their normal daily business on that day were fined five shillings. Though the official ban lasted only 22 years, the aversion to Christmas became deeply embedded in the New England soul and for generations the holiday was regarded as just another winter day. Businesses and schools were open on Christmas Day well into the 1800s.

As late as 1874, the famous Congregational minister Henry Ward Beecher wrote of his childhood in western Connecticut: “To me Christmas is a foreign day, and it will continue to be so until I die. When I was a boy, brought up in the old Litchfield Hills, nobody talked to me about Christmas.”

Queen’s Christmas tree at Windsor Castle 1848, adapted for Godey’s Lady’s Book, December 1850 (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

Changes came slowly. Episcopalians and Roman Catholics celebrated Christmas in beautiful, moving ceremonies. In 1823 Clement Clark Moore’s “A Visit from St. Nicholas” was published. European immigrants came, bringing their colorful traditions with them. In the 1840’s Christmas trees were first displayed. And in 1843, Charles Dickens’ “A Christmas Carol” focused readers’ attentions on moral values.

After the Civil War, New England embraced Christmas along with the rest of the country. Quiet, family-oriented celebrations replaced debauchery and drunkenness. Now, of course, the observance of Christmas has become a keystone in our national economy. Many retail businesses are dependent on it to remain solvent. Christmas has grown so commercialized that we seem to be on the verge of returning to a time when businesses are open on Christmas Day.

In response, many people find themselves longing for a less hectic, less materialistic celebration. They find ways to focus on what’s important, and turn their backs on the indulgence of over-the-top buying and endless partying. They gather in small groups of family and friends and enjoy the warmth of fellowship over simple home-cooked food.

Perhaps the ghosts of our Puritan ancestors are smiling.

Tagged: Anglican, Boston, celebration, Charles Dickens, Christmas, Christmas tree, Henry Ward Beecher, Increase Mather, Massachusetts Bay Colony, mumming, New England, pagan, Puritan, Roman Catholic, wassailing

December 18, 2013

Cold Worship

We’ve just emerged from a cold spell here in New England, with the temperatures bouncing between 20 below and 20 above. I’ve been more grateful than usual for central heating and wood fires, but it got me thinking about the Puritans and how they managed in the winters. While their homes were equipped with fireplaces that, though they were poorly designed for heating rooms, still put out enough heat to warm a person who was standing near them, their meeting houses were not. Worship was conducted in the cold.

We’ve just emerged from a cold spell here in New England, with the temperatures bouncing between 20 below and 20 above. I’ve been more grateful than usual for central heating and wood fires, but it got me thinking about the Puritans and how they managed in the winters. While their homes were equipped with fireplaces that, though they were poorly designed for heating rooms, still put out enough heat to warm a person who was standing near them, their meeting houses were not. Worship was conducted in the cold.

In the late 1600’s, Judge Samuel Sewall of Boston recorded the effects of the weather in his journal: “Extraordinary Cold Storm of Wind and Snow. Blows much as coming home at Noon, and so holds on. Bread was frozen at the Lord’s Table. Though ‘t was so cold John Tuckerman was baptized. At six o’clock my ink freezes, so that I can hardly write by a good fire in my Wives chamber. Yet was very Comfortable at Meeting.”

Samuel Sewall (1652-1730) (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

It makes one wonder what he meant by “comfortable.” Perhaps he was referring to the warmth of the fellowship. Or the warmth generated by many bodies in an enclosed space. Probably it was no colder than anywhere else. After all, he was used to sitting in rooms so cold that, even when next to the fire, his ink froze.

There were two services each Sunday, and the entire congregation was expected to be present. It must have been nearly unbearable to sit through a one-or-two hour sermon in sub-zero weather.

There are records of ministers annoyed by the people who stamped their feet and swung their arms to keep warm during the service. Those who could afford them sometimes brought small metal foot stoves filled with hot coals to keep their feet warm. But such items were prohibited in some churches, for fear they might start a fire. There is a report that sometimes bags made of animal skins were nailed to the edge of the benches for worshippers to warm their feet. In some places, people brought their dogs to lie on their feet, which created problems of another kind.

I began to think about what the churches they left in England must have been like. And it struck me that they didn’t have sources of heat, either. Most were built of stone and might have been even colder inside than out. The most they did was keep out the wind. So people simply wore their outdoor clothing when they worshipped in the winter.

The more I’ve researched the Puritans the more I’ve been struck by how little their lives differed from those of the friends and relatives they’d left behind in England. The only difference was that in New England the winters were generally colder.

In other words, people simply expected to be cold in winter – wherever they were. It was an unremarkable part of life. And, no doubt, it made the arrival of spring all the more appreciated.

Tagged: 1600's, 17th century, Boston, Congregational, England, foot stove, Heat, meeting house, New England, Puritan, Samuel Sewall, Snow, Worship

December 2, 2013

The Good-Humored Puritan

Like all Europeans, the New England Puritans relied on the medical theory of bodily humors to explain all physical and mental conditions. The theory goes all the way back to the ancient Greek physician Hippocrates; to the Puritans it was a reliable and time-honored methodology. Though the theory is no longer accepted, many of its terms are still in common usage today.

Like all Europeans, the New England Puritans relied on the medical theory of bodily humors to explain all physical and mental conditions. The theory goes all the way back to the ancient Greek physician Hippocrates; to the Puritans it was a reliable and time-honored methodology. Though the theory is no longer accepted, many of its terms are still in common usage today.

The theory of humors asserts that the body contains four basic substances that control a person’s personality and health. These fluids are blood, phlegm, choler or yellow bile, and melancholy or black bile. In order to be healthy, an individual’s humors had to be properly balanced. They determined his or her physical qualities and temperament. The theory also included variations based on heat, cold, moisture, and dryness.

The basic temperaments, personalities and their corresponding fluid are as follows:

sanguine – blood – extroverted, sociable, creative, talkative

choleric – yellow bile – active, energetic, ambitious, passionate, leaders

melancholic – black bile – thoughtful, creative, perfectionist, self-reliant, independent

phlegmatic – phlegm – contented, kind, affectionate, consistent, relaxed, observant, curious

Unbalanced humors were treated by bleeding, cupping, or purging to relieve the patient of the harmful excess of a humor. Puritans believed that all foods had an affinity with a particular humor, and could help to balance the body. They grew herbs used to counter disease symptoms, often based on the heat and moisture of the patient’s skin. Chamomile and arsenic were used to reduce heat by drawing off excess bile.

We still speak of personalities as “phlegmatic” or “sanguine,” and the heat and moisture qualities are reflected in our descriptions of spicy food as “hot” or certain wines as “dry.”

So a “good-humored” Puritan was happy not because of some good fortune that had happened to him, but because his body and temperament were well balanced. Although modern medicine is no longer based on humors, there may be something valuable to learn here, especially when we’re tempted to blame our bad moods on other people, or seek happiness by acquiring more material goods. Maybe we should stop and consider the possibility that there’s something in us that isn’t appropriately balanced – and then proceed to do what we can to fix it.

Tagged: Ancient Greek medicine, black bile, bleeding, choleric, colonial medicine, cupping, Four temperaments, Health, Hippocrates, Humorism, humors, Melancholia, New England, purging, Puritan, sanguine

November 26, 2013

A Puritan Looks at Thanksgiving

It’s deer hunting season here in Vermont. A few days ago it snowed and the ground is still white, making tracking a little easier for hunters. It’s a time of year that has a beauty of its own, a bridge between late fall and deep winter. Yet, there’s something about the sere black-and-white dignity of the landscape that evokes in me a strange mixture of stillness and sorrow.

It’s deer hunting season here in Vermont. A few days ago it snowed and the ground is still white, making tracking a little easier for hunters. It’s a time of year that has a beauty of its own, a bridge between late fall and deep winter. Yet, there’s something about the sere black-and-white dignity of the landscape that evokes in me a strange mixture of stillness and sorrow.

I’m not sure where that comes from; it’s a visceral, intuitive response. It may be some sort of hardwired, biochemical foreboding about the coming of winter and mortality. It might be my consciousness that, deep in the forest, beyond my range of vision, some hunter is visiting death on a healthy young buck.

Tomorrow my husband and I will travel to Massachusetts to celebrate Thanksgiving with our children. I grew up loving Thanksgiving- the warmth and laughter of the gathered family, the familiar scents and flavors of the traditional foods, the cozy satisfactions of the hearth. It was always a special day, partly because – unlike so many other holidays – it was simple and non-commercial. But this year, especially as I think about the Puritans, I’m also aware of an undertone of sorrow.

[image error]

English: “The First Thanksgiving at Plymouth” (1914) By Jennie A. Brownscombe (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

Like it or not, Thanksgiving is part of our national mythology; we learn the story of the first Thanksgiving when we’re very young and we’re reminded of it annually. And Indians are an integral part of the story. The truth is that, when we start looking at the history of Indians in this country, it doesn’t take long to get to a place of sorrow.

The so-called “First Thanksgiving,” celebrated in Plymouth Colony, was likely a three or four-day event marking a peace treaty between the colonists and the Wampanoags. It was a native tradition to seal treaties by sharing food and playing games.

By the middle of the 1600’s, the Puritans in the Massachusetts Bay and Connecticut colonies had established an annual autumn thanksgiving. However, usually thanksgiving days were observed in response to specific events. Overall, there were many more days of fasting and humiliation than there were of thanksgiving. During King Philip’s War, the Bay Colony forswore thanksgivings until the end of the hostilities. On June 29 1676, they held a “day of solemn thanksgiving.” The proclamation read:

“The Holy God having by a long and Continual Series of his Afflictive dispensations in and by the present War with the Heathen Natives of this land, written and brought to pass bitter things against his own Covenant people in this wilderness, yet so that we evidently discern that in the midst of his judgments he hath remembered mercy, having remembered his Footstool in the day of his sore displeasure against us for our sins, with many singular Intimations of his Fatherly Compassion, and regard; reserving many of our Towns from Desolation Threatened, and attempted by the Enemy, and giving us especially of late with many of our Confederates many signal Advantages against them, without such Disadvantage to ourselves as formerly we have been sensible of, if it be the Lord’s mercy that we are not consumed, It certainly bespeaks our positive Thankfulness, when our Enemies are in any measure disappointed or destroyed; and fearing the Lord should take notice under so many Intimations of his returning mercy, we should be found an Insensible people, as not standing before Him with thanksgiving, as well as lading him with our Complaints in the time of pressing Afflictions.”

The context for that thanksgiving wasn’t a celebration of the autumn harvest, but relief that the English had triumphed in the bloody and devastating war with the Wampanoag-Nipmuc-Pocasset-Narragansett alliance. Despite all their posturing of meekness and humility, the fact was that the Puritans believed that God considered them a chosen people, and that it was God who had destroyed their “enemies.”

Just as the beauty of the snow-blanketed forest can conceal the life and death struggles of its occupants, the conventional memes of Thanksgiving can obscure the ugly history of the Puritan treatment of Native Americans. This is just as much a part of our national story as the famous First Thanksgiving. If we are to begin to understand who we, as Americans, truly are, we must acknowledge and embrace its ugliness as well as its beauty.

Tagged: God, Indians, King Philip, King Philip's War, Massachusetts, Massachusetts Bay, Nipmuc, Plymouth Colony, Poccasset, Puritan, Thanksgiving, Wampanoag people, Wompanoag

November 16, 2013

Of Possets and Pompions: More from the Puritan Pantry

When I was writing Flight of the Sparrow, I spent many happy hours researching 17th century food customs.

When I was writing Flight of the Sparrow, I spent many happy hours researching 17th century food customs.

One of the earliest written recipes from New England is for “stewed pompion.” (“Pompion was a term used for both pumpkins and squash.) It was known as a “standing dish” because it was eaten with nearly every meal. (The recipe included a warning that this dish “provokes urine extremely and is very windy.”)

Slice ripe pompions, and cut them into dice, and so fill a pot with them of two or three gallons, and stew them upon a gentle fire a whole day, and as they sink, they fill again with fresh pompions, not putting any liquor to them; and when it is stewed enough, it will look like baked apples. Dish, putting butter to it, and a little vinegar (with some spice, as ginger, &c.) which makes it tart like an apple, and so serve it up to be eaten with Fish or Flesh.

A modern version, developed by experts at Plimoth Plantation, is easier to follow in the 21st century:

4 cups of boiled squash, roughly mashed

3 tablespoons of butter

2 to 3 teaspoons of cider vinegar

1 to 2 teaspoons of ground ginger

1/2 teaspoon of salt

Heat all ingredients together over medium heat. Adjust seasonings to taste and serve hot.

Another food that intrigued me was a “posset.” A posset was a frothy hot drink made from curdled milk, eggs, ale or wine, and spices. It was often used as a remedy for mild illness, such as a cold. Possets were served in posset pots, which usually had two handles and a spout. A well-made posset had three layers: the top was foam, or “grace;” the middle was a smooth spiced custard; and the bottom was the alcoholic liquid. The grace and custard were eaten with a spoon and the “sack” or alcohol at the bottom was sucked through the spout.

Here’s a posset recipe from 1671, followed by two modern versions:

Take a pottle of cream, and boil in it a little whole cinnamon, and three or four flakes of mace. To this proportion of cream put in 18 yolks of eggs, and 8 of the whites; a pint of sack; beat your eggs very well and then mingle them with your sack. Put in 3/4 of a pound of sugar into the wine and eggs, with a nutmeg grated, and a little beaten cinnamon. Set the basin on the fire with the wine and eggs and let it be hot. Then put in the cream boiling from the fire, pour it on high, but stir it not; cover it with a dish, and when it is settled, strew on the top a little fine sugar mingled with three grains of ambergris, and one grain of musk, and serve it up.

Posset

Posset pot, Netherlands, Late 17th or early 18th century, Tin-glazed earthenware painted in blue V&A Museum no. 3841-1901[1] Victoria and Albert Museum, London

1 quart of whipping cream

1 pint of ale

10 medium egg yolks

4 medium egg whites

1 cup sugar (or less according to your preference)

1 tsp. grated nutmeg

In a large stew pan combine the cream and ale and whip them together gently with a whisk.

In a mixing bowl vigorously whip your egg whites until very frothy. Add the egg yolks to the whites and continue to whip until very well blended and add to the cream and ale.

Add the sugar and nutmeg. Over a medium heat cook the mixture, stirring all the while, until it thickens. This should not be runny and not a thick custard either.

It can be served from a small punch bowl to individual bowls or in glasses.

Sack Posset

1/2 cup sugar

2 qts. milk

4 egg yolks, beaten

4 cups medium sweet sherry

Grated nutmeg or powdered cloves

Add sugar to milk in a saucepan. Mix well and heat to just barely scalding. Beat in the egg yolks. Stir in the sherry. Serve warm in punch cups, dusted lightly with nutmeg or cloves.

Tagged: 17th century New England, 17th century recipes, Colonial history of the United States, early America, England, Flight of the Sparrow, food, Indians, Massachusetts Bay Colony, New England, Plimoth Plantation, pompion, posset, pumpkin, Puritans, recipes

November 11, 2013

The Puritan Pantry

Like all immigrants, 17th century Puritans in New England brought their eating and cooking habits with them when they crossed the Atlantic. The hearth or fireplace dominated the main room, which was called a “hall,” a term that had its roots in the great halls of the middle ages. It was the room where most of the inside activity took place: cooking, eating, working, and sleeping. For many Puritans, especially in the early years of settlement, it was the only room.

When we look at pictures of 17th century hearths New England, one of the first things we notice is their enormous size. They’re big enough to stand up in and it’s not hard to imagine them filled with great, roaring fires. But, in fact, that isn’t an accurate image. The Puritan housewife actually spent much of her time inside the fireplace, tending several small fires at once. She had to have at least three fires going to maintain different temperatures for cooking. One was built to flame hotly, one consisted of glowing embers, and the third was made of hot ashes topped with coals. She had to watch them closely.

notice is their enormous size. They’re big enough to stand up in and it’s not hard to imagine them filled with great, roaring fires. But, in fact, that isn’t an accurate image. The Puritan housewife actually spent much of her time inside the fireplace, tending several small fires at once. She had to have at least three fires going to maintain different temperatures for cooking. One was built to flame hotly, one consisted of glowing embers, and the third was made of hot ashes topped with coals. She had to watch them closely.

It was a dangerous business. Long skirts and aprons frequently burst into flame from being too close to the fire. The beam inside the fireplace would quickly become charred from burning.

The housewife’s cooking equipment included earthenware dishes, copper and iron kettles and iron spiders (frying pans resting on legs). She had long handled dippers and spoons and glass bottles and pots. She improvised a double boiler by putting hay in the water at the bottom of a large iron kettle and resting a smaller kettle inside.

Meat was the basis of the Puritan diet. It was made into stews and pies and often flavored with onions and herbs grown in the kitchen garden. Salt was hard to come by, but sugar was plentiful. It came from Barbados and was used to flavor cakes, puddings, and drinks.

Meat was the basis of the Puritan diet. It was made into stews and pies and often flavored with onions and herbs grown in the kitchen garden. Salt was hard to come by, but sugar was plentiful. It came from Barbados and was used to flavor cakes, puddings, and drinks.

Beans, squashes, onions and pumpkins were popular. So was fruit; fruit trees were cultivated on most farms. They Puritans favored apples, pears, and quinces. They drank cider that was spiced and sweetened with sugar.

Here’s a 17th century recipe for a venison pasty:

Line the dish with a thin crust of good pure paste. Make it thick toward the brim that it may be there a pudding crust. Lay the venison in a round piece upon the paste in the dish. It must not fill it up to touch the pudding. Put the cover over it and it over-reach upon the brim with some carved pasty work to grace it. It must go up with “a border like a lace” growing a little ways upwards upon the cover. The cover should be arched and have a little hole in the top to pour in the well-seasoned broth made of broken bones and remaining flesh of the venison.

Bake 5 or 6 hours or more as an ordinary pasty. An hour or an hour and a half before you take it out, open the oven and pour the decoction of broken bones and flesh.

Tagged: Colonial history of the United States, Indians, King Philip's War, Massachusetts Bay Colony, New England, pasty, Puritan, Puritans

November 6, 2013

Cover Story

My new novel, Flight of the Sparrow, will be published in July, and available for pre-order in a month or so. I just received a pre-publication picture of the cover and I love it! It’s brilliantly and beautifully evocative of the story of Mary Rowlandson and her captivity during King Philip’s War. From the native encampment with its domed wetus, to the faint old-fashioned script suggesting the laborious effort it took for Mary to write her best-selling captivity narrative, every detail has significance. I especially like the barely discernible birds flocking across the “sky” of the woman’s apron – they’re so suggestive of freedom and joy.

I’m really excited to share it. And I’d love to know what you think!

Tagged: Boston, Colonial history of the United States, early America, Flight of the Sparrow, Indians, King Philip's War, Mary Rowlandson, Massachusetts Bay Colony, New England, Puritan, Puritans

October 28, 2013

A Dwelling Place

When the Puritans came to New England, one of their first concerns was shelter. They planned to build wood-framed houses with thatched roofs, like the ones they’d left in England. But there was a period of several months during which they had to find other shelter while erecting those houses. They used what they could find: tents and caves and holes dug in the ground. There is even a record of a family living in empty ship casks.

When the Puritans came to New England, one of their first concerns was shelter. They planned to build wood-framed houses with thatched roofs, like the ones they’d left in England. But there was a period of several months during which they had to find other shelter while erecting those houses. They used what they could find: tents and caves and holes dug in the ground. There is even a record of a family living in empty ship casks.  They also built huts and “hovels,” modeled after peasant country dwellings in England and similar to the sod houses of the westward expansion that would take place generations later. These were sometimes described as “wigwam-shaped,” because they resembled the house forms of their Native American neighbors.

They also built huts and “hovels,” modeled after peasant country dwellings in England and similar to the sod houses of the westward expansion that would take place generations later. These were sometimes described as “wigwam-shaped,” because they resembled the house forms of their Native American neighbors.

The Puritans had brought with them their house-building tools, and as soon as possible they began constructing frame houses. They trimmed tree logs into rectangular posts and beams for framing and cut grasses and reeds from the coastal marshes to make thatch. They fashioned their house walls of wattle and daub – a woven lattice of sticks inside the frame  filled with a mortar made of clay and dirt. They covered the exterior walls with clapboards – thin boards split from tree logs and nailed over the frame.

filled with a mortar made of clay and dirt. They covered the exterior walls with clapboards – thin boards split from tree logs and nailed over the frame.

These first frame houses were small, often with only one room in which all the indoor activities took place. They ate and worked there. They slept there on mattresses stuffed with straw, corn, or feathers, which were rolled up during the day. Sometimes there was a loft above the room used to  store food and other goods. The floor was usually hard-packed earth. The small early windows lacked glass, and were closed with a wooden shutter. The hearth dominated one end of the room. Large enough to step into, it’s where women spent much of their time, usually maintaining several small fires at once. Chimneys, when present, were built of wood and clay like the rest of the house. The interiors were smoky and dark. And cold in the winter.

store food and other goods. The floor was usually hard-packed earth. The small early windows lacked glass, and were closed with a wooden shutter. The hearth dominated one end of the room. Large enough to step into, it’s where women spent much of their time, usually maintaining several small fires at once. Chimneys, when present, were built of wood and clay like the rest of the house. The interiors were smoky and dark. And cold in the winter.

Over time, as an owner’s fortune grew, rooms were added, and a second story built. Often a lean-to was attached to the back of the house, creating the distinctive “salt box” profile of early New England architecture.

At the time of European-Indian contact, Native American tribes in southern New England lived in settled villages and practiced agriculture. They also hunted. In the spring they burned the undergrowth in the woods, making travel easier and encouraging the growth of game-attracting plants. In some places the hunting lands were so carefully managed that deer could be spotted at a distance of more than a mile. About every ten years, when the soil was depleted, the villagers moved together to a new location. They lived in extended family groups in domed longhouses in the winter and usually moved into single-family circular wetus (also known as wigwams) for the spring and summer.

At the time of European-Indian contact, Native American tribes in southern New England lived in settled villages and practiced agriculture. They also hunted. In the spring they burned the undergrowth in the woods, making travel easier and encouraging the growth of game-attracting plants. In some places the hunting lands were so carefully managed that deer could be spotted at a distance of more than a mile. About every ten years, when the soil was depleted, the villagers moved together to a new location. They lived in extended family groups in domed longhouses in the winter and usually moved into single-family circular wetus (also known as wigwams) for the spring and summer.

The men gathered saplings and stripped off the bark to form the wetu frames. The sapling bark was then split and used to tie the frame together. A small wetu required about forty saplings. The wetu frame was covered with sheets of bark in winter, or with double-sided mats woven of dried reeds in summer. A smoke hole was built into the center of the roof, situated directly over the fire pit. Sheets of bark were arranged above the smoke hole to shelter it from rain or snow, sheets which could be adjusted as needed.

The men gathered saplings and stripped off the bark to form the wetu frames. The sapling bark was then split and used to tie the frame together. A small wetu required about forty saplings. The wetu frame was covered with sheets of bark in winter, or with double-sided mats woven of dried reeds in summer. A smoke hole was built into the center of the roof, situated directly over the fire pit. Sheets of bark were arranged above the smoke hole to shelter it from rain or snow, sheets which could be adjusted as needed.

Inside, multi-purpose platforms were built that were used for everything from storage to sitting and sleeping. At night they slept under animal skins that were used for sitting on or wearing during the day. Woven mats made of bulrushes lined the wetu interiors. A pot of succotash almost always simmered over the central fire.

Inside, multi-purpose platforms were built that were used for everything from storage to sitting and sleeping. At night they slept under animal skins that were used for sitting on or wearing during the day. Woven mats made of bulrushes lined the wetu interiors. A pot of succotash almost always simmered over the central fire.

In the early days of the colony, the dwellings of these two groups were remarkably similar in size and comfort. There was at least one important difference, though. The round design of the wetus increased their energy-efficiency. When colonists chanced to sleep in wetus in cold weather, they remarked on how remarkably warm they were compared to their own English homes.

In the early days of the colony, the dwellings of these two groups were remarkably similar in size and comfort. There was at least one important difference, though. The round design of the wetus increased their energy-efficiency. When colonists chanced to sleep in wetus in cold weather, they remarked on how remarkably warm they were compared to their own English homes.

Tagged: Colonial history of the United States, frame house, Indians, King Philip's War, Massachusetts Bay Colony, New England, Pilgrims, post and beam construction, Puritan dwellings, Puritans, thatch roof, United States, Wampanoag, wetu, wigwam

October 18, 2013

The Law of the Land

When the Puritans migrated to Massachusetts Bay Colony in the 17th century, they brought their English legal mindset with them. Between 1630 and 1700, they enacted hundreds of laws, ordering people’s lives from cradle to grave. Everything from the proper gait of horses in Boston to the wearing of lace was regulated. As they saw it, these elaborate rules helped them create an orderly, Christian society. Today we find many of their laws amusing for their outdated and controlling perspective. But some are surprisingly progressive in their focus on protecting the weak and less fortunate members of their communities. Overall, they give us a glimpse into the Puritan mind and help us better understand the society they were trying to build.

Here are just a few, with updated spellings. (Note: the monetary fines are in British currency; “s” stands for shilling; “d” stands for pence; and £ stands for pound.)

No surgeon, midwife, or physician shall practice on any without consent of the person or nearest relation.

All persons not worth 200 £ wearing gold or silver lace, or buttons, or bone lace above 2 s. per yard, or silk hoods, or scarves, may be presented by the Grand Jury and shall pay 10 s for every offence.

The selectmen of every town may assess those who dress above their rank, at 200 £ estate, and make them pay as those to whom their dress is suitable, except the magistrates, their wives and children, officers, civil or military, soldiers in time of service, or such as had had a high education or are sunk from a higher fortune.

All parents to teach their children to read, and all masters to acquaint their families with capital laws on penalty of 20 s., and to catechize them once a week.

A son of 16, accused by parents of rebellion and other notorious crimes, shall be put to death.

Fornication is to be punished by compelling marriage, fines, or as the Court sees fit.

Everyone to fence according to his proportion of the corn-field in common, and not to put in cattle while any corn remains.

Every householder has free fishing and fowling in any river, bay, etc., within the precincts of the town where they dwell, so far as the sea ebbs and flows, unless it be appropriated by the Freemen.

No horse to be sold to an Indian, on penalty of 100 £.

Any may pass on another’s land, not trespassing on corn or meadow.

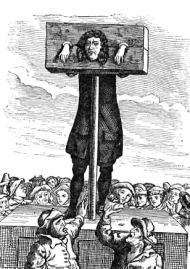

Whoever publishes a lie to the prejudice of the public, or any private person, pays 10 s or sits in the stocks two hours for the first offense, for the second 20 s. or whipped ten stripes, for the third 40 s. or fifteen stripes. Every new fault increases 10 s. or five stripes.

Lands in the jurisdiction not improved by Indians is the property of the English.

None to sell the Indians a boat, skiff, or canoe, on forfeiture of 50 £.

No Court can punish with above forty stripes.

No man must correct any under him with cruelty, or be cruel to a beast.

No dancing in public houses, on penalty of 5 s.

No one to gallop a horse in Boston, on penalty of 3 s. 4 d.

Married persons must live together, unless the Court of Assistants approve of the cause to the contrary.

No work to be done on the Sabbath on penalty of 10 s, for the first offence, to be doubled for every following one.

To travel to a Meeting not allowed by law is a profanation of the Sabbath.

Witches suffer death.

Tagged: Boston, Colonial history of the United States, Colonial laws, Indians, Massachusetts Bay Colony, New England, Puritan, Puritans, regulations in colonial America, witches

October 9, 2013

A Sacred Journey

At the end of October 1675, in the midst of the hostilities of King Philip’s War, the General Court of the Massachusetts Bay Colony ordered an immediate evacuation of Christian Indians to Deer Island in Boston Harbor. A group of men under Captain Thomas Prentice descended on Natick, the largest “praying Indian” town, rounded up all the inhabitants – men, women, and children – and gave them less than two hours to gather their possessions and prepare for the trip. They were marched to the Charles River, about two miles from Cambridge, where three ships waited to transport them. The Reverend John Eliot, of Roxbury, who had been responsible for converting many of them, met to console them and lead them in prayer. On the morning of October 30th they were herded onto the boats and taken to the island.

At the end of October 1675, in the midst of the hostilities of King Philip’s War, the General Court of the Massachusetts Bay Colony ordered an immediate evacuation of Christian Indians to Deer Island in Boston Harbor. A group of men under Captain Thomas Prentice descended on Natick, the largest “praying Indian” town, rounded up all the inhabitants – men, women, and children – and gave them less than two hours to gather their possessions and prepare for the trip. They were marched to the Charles River, about two miles from Cambridge, where three ships waited to transport them. The Reverend John Eliot, of Roxbury, who had been responsible for converting many of them, met to console them and lead them in prayer. On the morning of October 30th they were herded onto the boats and taken to the island.

At that time Deer Island was forested. Uninhabited by wolves, it was used by the English as a place for grazing sheep. Over the duration of the war at least 500 hundred – and possibly more than 3,000 – Indians, most of them converted Christians loyal to the English, were confined there that winter, without sufficient food or shelter. Forbidden to cut the trees and with shellfish as their only local source of food, many died of starvation. Others were kidnapped and put on slave ships headed for the Caribbean.

Next Saturday morning, October 12, 2013, a group of Native Americans will launch canoes from Deer Island and paddle across Boston Harbor and up the Charles River to Brighton, Massachusetts. Among the paddlers there will be Nipmucs, descendants of people who were interned on the 138-acre island. The trip will last more than five hours across wind-whipped water; it will be a cold ride, even if the weather is fine.

The Nipmucs won’t be making this trip for exercise or recreation. They won’t be on a sightseeing excursion. They won’t even be paddling to raise money for a cause. Theirs is a sacred journey. They will be reversing the passage their Ancestors took 338 years ago. They will be carrying the spirits of their Ancestors home.

Tagged: Boston, Colonial history of the United States, Deer Island, Indians, King Philip's War, Massachusetts Bay Colony, Narragansett, Natick, New England, Nipmuc, Nipmucs, Puritan, Wampanoag

![Posset pot, Netherlands, Late 17th or early 18th century, Tin-glazed earthenware painted in blue V&A Museum no. 3841-1901[1] Victoria and Albert Museum, London](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1384672616i/6930348.jpg)