Amy Belding Brown's Blog, page 3

October 17, 2014

A Puritan Hero

About a decade ago, I worked for a few years at the Orchard House Museum in Concord, Massachusetts. Best known as the home of Louisa May Alcott and the place where she wrote the classic novel, Little Women, the house has an impressive history of its own. When I was there the 300-year-old building, renovated by Bronson Alcott in the 1850’s, was in the midst of a massive preservation project, so I had the opportunity to see, up-close, some of the details of the colonial construction. Ever since, I’ve been fascinated not just by how historical houses are decorated, but how they’re constructed.

About a decade ago, I worked for a few years at the Orchard House Museum in Concord, Massachusetts. Best known as the home of Louisa May Alcott and the place where she wrote the classic novel, Little Women, the house has an impressive history of its own. When I was there the 300-year-old building, renovated by Bronson Alcott in the 1850’s, was in the midst of a massive preservation project, so I had the opportunity to see, up-close, some of the details of the colonial construction. Ever since, I’ve been fascinated not just by how historical houses are decorated, but how they’re constructed.

At that time, I was finishing work on my novel, Mr. Emerson’s Wife, about the Transcendental circle in19th century Concord. Little did I know that a few years later, I’d encounter the house again, as I researched a 17th-century Concord lawyer for my new novel, Flight of the Sparrow.

John Hoar, the man who built the home that the Alcotts purchased, was the colonial negotiator in the ransom of Mary Rowlandson. He was the man who escorted her back to the English towns after her release. Rowlandson writes about him in her narrative, and describes visiting his house on her return to Boston.

Despite his prominence in his own tumultuous time, Squire Hoar remains an obscure figure to us, hidden in the shadows of history. I had learned about some of his remarkable descendants when I was studying the Concord Transcendentalists, but there was little about the man himself – just the tantalizing suggestion he didn’t fit neatly into the Puritan mold.

When I began digging, I discovered a hero.

John Hoar was a principled and independent-minded man, who spoke his mind regardless of the consequences. He began having trouble with the authorities in the mid-1660s when he tried to expose the judicial corruption of Massachusetts Bay magistrates. He petitioned the governor for justice and received a hearing in October of 1665. It probably did not surprise him when his complaints were ruled “groundless and unjust,” since some of the judges he accused were sitting on the court. But even Hoar was surprised when they fined him and sentenced him to prison—to set an example for any who dared to challenge their authority.

Furious, Hoar stormed out of court. When he was arrested and hauled back in, his bond was set at 100 pounds (an extraordinarily high fee for that time), and he was disbarred.

The next spring, Hoar petitioned the court for relief and he was released and his fine was reduced, but his lawyer’s standing was not restored. Though he returned to Concord and his family, Hoar was not a man to remain silent. He told his neighbors exactly what he thought about the authorities. He was soon back in court, subjected to more fines, and the demand for a formal apology. When he was released with a warning, he went back to practicing law – and criticizing the authorities.

In 1675, when King Philip’s War broke out, Hoar offered to protect a group of friendly

Possible site of palisade to protect natives.

Nipmucs who lived near Concord. He set aside some of his own property and, at his own expense, built a workshop and palisade for their defense, and helped them harvest their food.

Some of Hoar’s Concord neighbors, frightened by the close proximity of natives, even though they were friendly, secretly contacted the army captain, Samuel Mosely, a man known for his brutality.

On a Sunday morning in February, Mosely and his soldiers marched into the meeting house. After worship he addressed the congregation. He announced that he’d heard there were “some heathen in the town” that he believed were distressing people, and that if they wanted, he would remove them. Most people said nothing, though “two or three” encouraged him. So, over Hoar’s vigorous objections, he ordered his soldiers to break down the door and take the Indians. They followed his orders, destroying Hoar’s property, seizing the Indians and plundering their food and clothing. The Indians were then marched to Charlestown and sent to Deer Island.

But Hoar was not a man to be defeated. In late April, he volunteered to negotiate with the Indians over Rowlandson’s ransom. This was a remarkable act of courage, especially given the tenor of the times. Even though Hoar was known to the natives, there was no guarantee that he would succeed in his efforts to secure Rowlandson’s release. In fact, when he reached the Indian encampment at what is now Redemption Rock, shots were fired in his direction (over and under his horse), he was threatened with hanging, and was confined to a wetu for days before an agreement was reached.

But John Hoar had never let fear rule him, and he successfully negotiated Rowlandson’s release. He returned to Concord and continued to be a thorn in the side of the Puritan authorities.

The next time you’re in Concord, Massachusetts, I urge you to visit Orchard House. Not only to see the place where Louisa May Alcott lived and wrote, but also to honor the memory of a man of persistence and principle—a Puritan hero.

Tagged: 17th century, Colonial history of the United States, colonial New England, early America, John Hoar, Louisa May Alcott, Mary Rowlandson, Massachusetts Bay, Massachusetts Bay Colony, Nipmucs, Orchard House, Puritan, Puritan dwellings

October 3, 2014

Upon This Rock

On a drizzly fall morning earlier this week, on my way back to Vermont from Providence, Rhode Island, I stopped at Redemption Rock, the site where Mary Rowlandson was ransomed back to the English by her Native American captors. The rock is located just off a narrow, wooded stretch of Route 140 in Princeton, Massachusetts, and it’s easy to miss. It’s been awhile since I’ve visited, and like all outdoor places, its mood varies with the weather. Even though it’s just a few yards from the road, the huge rock feels private, oddly safe. Perhaps it’s the huge size of the rock. It’s really a ledge outcropping, not a boulder, and it rises out of the ground gradually, as if emerging from the earth. It reminds me of the prow of a ship cresting the waves.

On a drizzly fall morning earlier this week, on my way back to Vermont from Providence, Rhode Island, I stopped at Redemption Rock, the site where Mary Rowlandson was ransomed back to the English by her Native American captors. The rock is located just off a narrow, wooded stretch of Route 140 in Princeton, Massachusetts, and it’s easy to miss. It’s been awhile since I’ve visited, and like all outdoor places, its mood varies with the weather. Even though it’s just a few yards from the road, the huge rock feels private, oddly safe. Perhaps it’s the huge size of the rock. It’s really a ledge outcropping, not a boulder, and it rises out of the ground gradually, as if emerging from the earth. It reminds me of the prow of a ship cresting the waves.

The last time I was there, I was in the middle of writing Flight of the Sparrow, and I  spent my time trying to visualize what it must have looked like in the spring of 1676, the ledge at the top of a rise overlooking a large clearing filled with wetus. This time, I breathed in the perfumes of wet autumn leaves and evergreens, and relished the soft cushion of pine needles under my shoes. I noticed how the bright colors of the fallen leaves is enhanced, not diminished, by the rain.

spent my time trying to visualize what it must have looked like in the spring of 1676, the ledge at the top of a rise overlooking a large clearing filled with wetus. This time, I breathed in the perfumes of wet autumn leaves and evergreens, and relished the soft cushion of pine needles under my shoes. I noticed how the bright colors of the fallen leaves is enhanced, not diminished, by the rain.

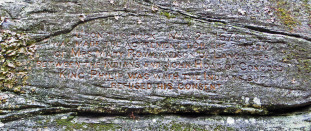

I thought of Mary coming to this place, near-starving and weary after weeks of walking. I wondered if she actually stood on the rock while she was being ransomed. The inscription carved into the south side of the rock in the 19th century reads:

Upon this rock May 2, 1676 was made the agreement for the ransom of Mrs Mary Rowlandson of Lancaster between the Indians and John Hoar of Concord. King Philip was with the Indians but refused his consent.

It’s certainly possible that the actual transfer took place on top of the rock. It’s a suitable setting for what must have been an important ceremony. But what struck me is that the outcropping is such an easily identifiable landmark.

I n a time long before GPS tracking and in a population lacking detailed maps of the area, natural features, especially ones unlikely to change over the years, were godsends. A large rock outcropping on high land in the shadow of Mount Wachusett would have been easy to find – for both natives and English. And it would also have been easy to remember. As the years passed and Mary Rowlandson’s captivity narrative was read and reread by succeeding generations, the site of her ransom became a concrete connection to an increasingly murky past. There’s something that grounds you when you stand on the site of a momentous event in human history.

n a time long before GPS tracking and in a population lacking detailed maps of the area, natural features, especially ones unlikely to change over the years, were godsends. A large rock outcropping on high land in the shadow of Mount Wachusett would have been easy to find – for both natives and English. And it would also have been easy to remember. As the years passed and Mary Rowlandson’s captivity narrative was read and reread by succeeding generations, the site of her ransom became a concrete connection to an increasingly murky past. There’s something that grounds you when you stand on the site of a momentous event in human history.

For me, it was both humbling and haunting.

Tagged: 17th century, Algonquian, captivity narrative, colonial New England, Flight of the Sparrow, King Philip's War, Mary Rowlandson, Massachusetts, Massachusetts Bay Colony, Princeton, Puritan, Puritans, ransom, Redemption Rock

September 17, 2014

Imagined Encounters II: On the Trail

One of the pleasures of writing historical fiction is vividly imagining what it must have been like to live in another time and place. As I’m shaping a novel, I do a lot of preparatory writing that never makes it into the book. This passage imagines the experience of Wowaus (James Printer) as he accompanies other Nipmucs through their territory in the late winter of 1676, fleeing the English soldiers. (See Chapter Eleven in Flight of the Sparrow for Mary Rowlandson’s perspective on these events.)

He is hungry; they are all hungry. There are only scraps to eat; no one has had time to hunt, and they can carry only some of the few winter stores that are left. He knows this hunger well; it is familiar to him, familiar to all Nipmuc. That is the way of things – the great cycles of the seasons bring warmth and plenty and then famine and cold. He has learned – they have all learned – how to endure.

But the English are soft. They do not live according to the seasons but spend their days building up stores of grain for the winter. This is a way the Hassanamesit try to follow, a way that Mr. Eliot and his friend Mr. Gookin praise them for, but Wowaus and others worry that it will make them soft like the English.

Even as they walk, he feels his body grow hard like the trunk of a walnut tree that has lost its summer leaves and stands fast against the wind and snow. He helps to carry some of the old ones, who have become yet more feeble because of hunger. A grandmother rides on his back up a long hill through thick trees. At last they come to the Bacquag which is a tumble of ice and white water. He had hoped that it would be frozen, but should have known better. The past three days have been warm enough to melt snow and the river is often in a rage, even in winter.

He, along with other men, fells trees for rafts. There are hundreds who must be carried to the far side of the river, and their time is short. Though he knows Monoco has sent a party of warriors to cover their tracks, it is no assurance that the English will not stumble upon them by accident. He works in a fury, stopping only to drink from the icy river. The cold is a good thing, he knows. It fortifies him, makes him strong. He realizes as he sinks his hatchet deep into the trunk of a small maple, that he is very much enjoying being a Nipmuc again.

It takes them two days to ferry everyone over. The women build wigwams on the far shore and they rest warm for three days and nights. On the second morning, as he walks about the makeshift village he sees the captive woman sitting outside a wigwam, wrapped in a blanket, knitting stockings. Her eyes are red, as if she has been crying or is ill, and there is a bright bruise on her cheek – a slap mark. She has apparently raised the ire of Weetamoo. He smiles. She is a woman of spirit, perhaps too much spirit for her own good. He wonders what she has done.

He watches her from the far side of a wigwam; he sees her sense that she is being watched, sees her head come up and her eyes skitter over the people nearby, but she does not see him, he is certain.

He considers approaching her and decides not to. There is something very sweet in watching over her this way. As if he is like one of Mr. Eliot’s guardian spirits.

A gray dog comes up to him and sniffs his heel. He wonders when they will start eating the dogs. Food is very scarce. The day before, he watched his uncle butcher a horse taken from the English, the same horse he had arranged for the red haired captive to ride. It would be a starving winter, thanks to this war with the English.

The sun drops into the trough of trees on the far side of the ridge and he leaves his watch for another day. The captive Mary sits outside the wigwam, knitting and knitting.

On the fifth morning, just after dawn, the warriors fire the wigwams and flee north. For hours the air is thick with smoke and from the ridges, Wowaus can see flames licking up into the trees. By mid-day, scouts report that the English army has reached the Bacquag and it has stopped them, at least for a time. Apparently they cannot decide how best to cross. Monoco directs his warriors to take the people down out of the hills to a swamp.

Swamps have always been a place of safety; all tribes retreat to them when threatened. The boggy ground is dangerous, and it’s difficult to track people in the thick vines and thickets that run along the ground and reach out to grab a man’s leg or ankle.

They travel as quickly as possible but the trail is narrow and steep and there are hundreds of people, all weary and weak from lack of food. As they descend into a valley the trees open up to reveal a landscape of abandoned English fields. The yellow spikes of old corn stalks poke through the snow. They halt and Monoco sends scouts out over the fields and into the woods beyond. They soon return with the report that there are no English in the area.

The women fan out across the fields to glean what corn and wheat has been left from a long-ago harvest. Wowaus sees the red haired captive pick up a broken ear of corn and drop it into her pocket. She looks around, furtively, then – miraculously – finds another. He sees how tempted she is to eat it on the spot, but something stays her. She has an uncommon resolve for a woman. Later, he sees a young woman steal one of the ears and watches Mary’s outraged accusation. He knows she will not get it back. The young woman is as hungry as Mary, and has two children to feed as well. The other women gather around the captive, mocking her and laughing.

That night there is an expansive joy in camp, as the stewpots are augmented with grain and maize. For the first time since the Medfield attack, Wowaus feels satisfied after eating. He walks through camp, stopping to talk with friends. He does not acknowledge, even to himself, that part of his reason for walking is to locate the red haired captive. Yet when he comes on her, sitting with Weetamoo’s family by a cook fire, he feels a rush of excitement, a small thrill that begins deep in his belly and rises like sap up through his abdomen and chest.

Mary’s face is smeared red with grease and blood from the half-cooked piece of horse liver she is eating. She holds it, dripping, in both hands and tears at it with her teeth. Blood runs from the sides of her mouth and falls onto her apron. She is entirely absorbed in eating, and does not realize he’s watching. If it were not for her copper hair and the paleness of her skin, she could pass as a Nipmuc. He wonders if she realizes how quickly she has become an Indian.

He is certain she does not. The news would no doubt distress her. It has not escaped his notice that the English fear becoming an Indian even more than they fear being killed by one.

He walks on. He is aware of cold bubbles of happiness rising through his chest. He is glad she is becoming an Indian. She will make a good wife; she is strong and resilient and clever.

Tagged: Algonquian, Colonial history of the United States, Daniel Gookin, early America, Flight of the Sparrow, historical fiction, James Printer, John Eliot, King Philip's War, Mary Rowlandson, Massachusetts, New England, Nipmuc, praying towns, Puritans, Wowaus

August 28, 2014

Blood on the Snow

Mary Rowlandson’s bestselling captivity narrative begins with the words: “On the tenth of February 1675, came the Indians with great numbers upon Lancaster.” Her book then goes on to tell the chilling story of the devastating attack on her home and family and her ensuing captivity.

Mary Rowlandson’s bestselling captivity narrative begins with the words: “On the tenth of February 1675, came the Indians with great numbers upon Lancaster.” Her book then goes on to tell the chilling story of the devastating attack on her home and family and her ensuing captivity.

In my research for Flight of the Sparrow, I came across a 19th century source listing what happened to the people who were in the Rowlandson garrison when it was attacked. Reading the names and ages of those killed and captured – not just numbers – brings the scene, and the individuals, more vividly to life.

Here’s what I was able to find out about those people. (Note: the ages are approximate. There are several people whose fates I was not able to find.)

Killed in the Attack:

Ensign John Divoll, husband to Hannah, brother-in-law to Mary Rowlandson

Josiah Divoll, age 7, son of John and Hannah Divoll

Daniel Gains

Abraham Joslin, age 26

Thomas Rowlandson, age 19, nephew of Joseph and Mary Rowlandson

John Kettle, age 36

John Kettle, Jr., son of John and Elizabeth Kettle

Joseph Kettle, age 10, son of John and Elizabeth Kettle

Elizabeth Kerley, age 41, wife of Lieutenant Henry Kerley and older sister to Mary Rowlandson

William Kerley, age 17, son of Henry and Elizabeth Kerley

Joseph Kerley, age 7, son of Henry and Elizabeth Kerley

Priscilla Roper, wife of Ephriam Roper

Priscilla Roper, age 3, daughter of Ephriam and Priscilla Roper

Taken Captive in the Attack:

Mary Rowlandson, age about 39, wife of town minister, Joseph Rowlandson, ransomed May 2, 1676

Mary Rowlandson, age 10, daughter of Joseph and Mary Rowlandson, ransomed

Joseph Rowlandson, Jr., age 12, son of Joseph and Mary Rowlandson, ransomed

Sarah Rowlandson, age 6, daughter of Joseph and Mary Rowlandson, died of wounds, February 18th

Hannah Divoll, wife of Ensign John Divoll, younger sister of Mary Rowlandson, ransomed

John Divoll, age 12, son of John and Hannah Divoll, died in captivity

William Divoll, age 4, son of John and Hannah Divoll, ransomed

Ann Joslin, wife of Abraham Joslin, killed in captivity

Beatrice Joslin, age 2, daughter of Abraham and Ann Joslin, killed in captivity

Henry Kerley, age 16, son of Henry and Elizabeth Kerley

Hannah Kerley, age 13, daughter of Henry and Elizabeth Kerley

Mary Kerley, age 10, daughter of Henry and Elizabeth Kerley

Martha Kerley, age 4, daughter of Henry and Elizabeth Kerley

Infant, child of Henry and Elizabeth Kerley

Elizabeth Kettle, wife of John Kettle, ransomed

Sarah Kettle, age 14, daughter of John and Elizabeth Kettle, escaped from captivity

Jonathan Kettle, son of John and Elizabeth Kettle

Ephriam Roper, escaped during attack

There were also at least eight people killed and two people captured during the attack on Lancaster who were not in the Rowlandson garrison. A soldier from Watertown was killed a few days after the attack. And a John Roper was killed on March 26, 1676, the same day the town was abandoned by all the remaining inhabitants.

Tagged: 17th century, attack on Lancaster, Colonial history of the United States, early America, Flight of the Sparrow, Indians, King Philip's War, Lancaster, Mary Rowlandson, Massachusetts, New England, Puritan

August 23, 2014

How They Lived

I’ve always been as interested in the day-to-day lives of people in other times as I have in the dramatic events of history. So I spend a good deal of time researching domestic details. Here are a few of the many facts I uncovered about the lives of the New England Puritans:

I’ve always been as interested in the day-to-day lives of people in other times as I have in the dramatic events of history. So I spend a good deal of time researching domestic details. Here are a few of the many facts I uncovered about the lives of the New England Puritans:

Rooms were lit by tallow-candles, made by dipping spun wicks of cotton or tow into melted tallow. Tallow is made from beef or mutton fat, and can be stored for long periods of time without decaying.

Wheeled vehicles, except for ox carts, were rare. While there were coaches in Boston in the late 1600’s, stage-coaches, carriages, and “riding chairs” (a chaise body without a top) didn’t appear until the early 18th century.

Women did not wear jewelry, not even wedding rings.

The first shelters for the colonists were not log cabins but caves or modified wetus. The homes they constructed were modeled on English houses of time. Depending on the wealth of the owner, they ranged from single-room wattle-and-daub cottages with thatched roofs to two or four room frame houses with an entry room and staircase.

Two of the seventeen capital crimes in Massachusetts Bay Colony were for speech: blasphemy and cursing a parent. The penalty was death.

Breakfast usually consisted of leftovers or other foods that were quickly prepared. A typical breakfast was corn mush or milk, though a large breakfast could also include cheese, bread, beer, and leftover meat.

For over fifty years, it was a crime to celebrate Christmas in Massachusetts Bay Colony. Even though that law was repealed in 1681, disapproval of Christmas celebrations continued until after the Civil War.

First marriages required parental permission. The Puritans did not consider marriage a sacrament and prohibited ministers from performing wedding ceremonies. Instead they were informal events which took place in the bride’s home and were presided over by a magistrate.

In 1647, the Old Deluder Satan Law required towns with 50 families to provide for the education of children.

Everyone drank alcoholic beverages, including hard cider, ale, rum, and wine. There were more arrests for public drunkenness than for any other crime.

Tagged: Boston, colonial customs, Colonial history of the United States, colonial life, Massachusetts Bay Colony, Puritan, Puritans, regulations in colonial America

August 7, 2014

The Story of the Slave Silvanus

In my novel, Flight of the Sparrow, Silvanus Warro makes a brief appearance when Mary Rowlandson encounters him after her return to Boston in the home of Daniel Gookin. My first encounter with Silvanus began when I read Diane Rapaport’s fascinating book, The Naked Quaker, which explores stories unearthed from the old court records of colonial New England. Silvanus was born in Maryland on a plantation owned by the Gookin family. He was a baby when Daniel Gookin took him to Massachusetts, where he lived with Gookin’s wife and infant daughter in Cambridge. Gookin was to become an important military and civic leader in the colony, and devoted a lot of time and energy to helping John Eliot convert the natives and organize “Praying Towns.”

In my novel, Flight of the Sparrow, Silvanus Warro makes a brief appearance when Mary Rowlandson encounters him after her return to Boston in the home of Daniel Gookin. My first encounter with Silvanus began when I read Diane Rapaport’s fascinating book, The Naked Quaker, which explores stories unearthed from the old court records of colonial New England. Silvanus was born in Maryland on a plantation owned by the Gookin family. He was a baby when Daniel Gookin took him to Massachusetts, where he lived with Gookin’s wife and infant daughter in Cambridge. Gookin was to become an important military and civic leader in the colony, and devoted a lot of time and energy to helping John Eliot convert the natives and organize “Praying Towns.”

In 1667, Gookin promised to set Silvanus free. However, he “postponed” that promise and rented Silvanus to Deacon William Park in Roxbury. The understanding was that, if Silvanus gave Park eight years of faithful service, then Gookin would set him free in 1675.

Apparently it was too much for Silvanus. In 1668 he tried to escape by taking a horse from Park’s stable and riding away. He was captured and returned to Park, but a few years later he got into more trouble when he fell in love with Elizabeth Parker, an indentured servant from Lancaster who lived in Park’s household, and fathered her child. The couple prepared to flee. Silvanus broke into Park’s strongbox and took money, but the robbery was discovered before they left. Elizabeth gave birth to a son and was sent back to her father in Lancaster; Silvanus went to prison.

Gookin and Park visited Silvanus in prison and presented him with a cruel choice – Gookin could send him to Virginia where he would be sold onto a plantation, or Park could sell him to a Medford slave owner, Jonathan Wade, and use the profits to support the child. It’s not surprising that Silvanus chose to stay in Massachusetts, where he had a chance of seeing Elizabeth and his son. Park got his money and Silvanus left prison in 1672 with Gookin’s advice that he should make a life with Wade’s “Negro wench.”

Meanwhile, in Lancaster, Elizabeth Parker’s father, Edmund, welcomed her and her son and refused to surrender the boy when Lancaster authorities tried to send the baby back to Roxbury. The town officials took the matter to court, claiming that the family was too poor to support the child. Deacon Park, who had received the proceeds from Silvanus’s sale to Wade, never turned over the money. Instead, he proposed selling Silvanus and Elizabeth’s son and putting him “out to service.” The court agreed.

Edmund Parker continued to resist, but eventually the child was taken and sold, while Silvanus continued his life as Wade’s slave. Gookin, who apparently regretted his part in the events, came up with a plan to reclaim Silvanus.

In November of 1682, Silvanus secretly traveled from Medford to Cambridge and signed an indenture agreement to serve Gookin for the rest of his life. When Wade discovered that his slave was missing, he called the constables and sent them to return Silvanus. Gookin sued Wade for “holding and detaining” his servant, and presented a compelling case for why Silvanus should be returned to him, but the court ruled against him, and ordered that Wade could keep him for life.

Silvanus was never set free. In 1707, his son, Silvanus Jr., came back to Boston, severely injured – a “lame cripple” according to court documents – but a free man, after more than thirty years as a slave. It was too late for him to meet with his father; Silvanus had died. But he discovered that he had a half-sister in service in the Wade home, and he vowed to set her free. Unfortunately, there’s no record to tell us whether or not he was successful.

Tagged: Boston, Cambridge, Colonial history of the United States, Daniel Gookin, Deacon William Park, Elizabeth Parker, Flight of the Sparrow, Jonathan Wade, Mary Rowlandson, Massachusetts, Massachusetts Bay Colony, Puritans, Silvanus Warro, slavery in colonial America, slavery in New England

July 20, 2014

Ten Little-Known Facts about New England Puritans

1. They opposed the use of musical instruments in worship services, especially organs. They believed such music distracted worshipers from their spiritual concentration.

2. A Puritan’s certainty of salvation was a sign he or she was probably damned. Uncertainty about salvation was a core doctrine.

3. Early Puritans were hostile to traditional funeral rituals. The dead were buried quickly and matter-of-factly, without ceremony or mourning.

4. All able-bodied men owed their town several days’ labor on roads each year.

5. Men socialized more often than women did.

6. Clergy did not officiate at weddings; magistrates did. The Puritans did not consider marriage a sacrament.

7. Moderate alcohol consumption was seen as socially beneficial. They drank alcohol regularly at meals.

8. Fishing was their most popular sporting pastime.

9. The Puritans enjoyed playing cards. The most popular card game was whist. They also played cribbage, quadrille, all-fours, and piquet.

10. They believed that married partners should have sex for pleasure. Sexually pleasing one’s spouse was a duty. Impotency was grounds for divorce, and women were expected to have orgasms.

Tagged: alcohol consumption, cards, Colonial history of the United States, Colonial laws, dancing, early America, fishing, Massachusetts Bay, Massachusetts Bay Colony, New England, Puritans, regulations in colonial America, salvation, whist

June 27, 2014

Visiting the Plantation

Site of Mary Rowlandson’s capture

When I’m researching a novel set in history, I like to visit the locations where the characters lived. When writing Flight of the Sparrow, I walked the land where Mary Rowlandson’s farm stood in Lancaster, Massachusetts, and visited “Redemption Rock,” in Princeton, Massachusetts, where she was ransomed back to the English. I walked through

Redemption Rock, site of Rowlandson’s release.

Hassanamesit Woods, in Grafton, Massachusetts, which archeologists think may have been the location for the Praying Indian village of Hassanamesit in the 1600’s. These visits give me a sense of the contours of the landscape and the locations of natural landmarks, but they can’t give me what I most want – the full sensory experience of living in another century.

Fairbanks House

The best way I know to get that knowledge is to visit museums. House museums help a lot, but there aren’t many houses from the 17th century that are still standing. The Fairbanks House in Dedham, Massachusetts is a fine exception, but like most homes that have been around for years, it’s been remodeled many times.

Plimoth Plantation

What I found most helpful in researching Flight of the Sparrow was visiting Plimoth Plantation. That living history museum presents life in 1628, which predates that events of my novel by almost fifty years, but it offers a pretty good idea of what the frontier town of Lancaster was probably like when Mary first moved there with her parents. And it has the added advantage of a recreated native Wampanoag village.

I’ve gone to Plimoth Plantation several times, and each time I’ve learned some new bit of information. But more valuable is seeing how the English colonists lived their lives in the spaces they built for themselves in the New World. And observing the traditional ways of the native people – ways passed down through generations – that shaped and inhabited the land the English Puritans came to claim as theirs.

May 8, 2014

The More Things Change . . .

Last night I happened to watch a dated video clip of Michele Bachmann asserting that 9/11 and Benghazi were God’s judgment on the United States. She’s also stated that natural disasters, including hurricanes and earthquakes are the hand of God punishing us. And she’s not alone. Fundamentalist religious leaders of various faiths have perceived God’s chastisement in the human suffering brought on by disasters, including Hurricane Katrina, the Haiti earthquake, the Japanese earthquake and tsunami, Hurricane Sandy, and even the Sandy Hook school massacre. But the idea that disasters are actually divine retribution is not a new one – it stretches back to Biblical times. And the New England Puritans embraced it, enthusiastically.

Last night I happened to watch a dated video clip of Michele Bachmann asserting that 9/11 and Benghazi were God’s judgment on the United States. She’s also stated that natural disasters, including hurricanes and earthquakes are the hand of God punishing us. And she’s not alone. Fundamentalist religious leaders of various faiths have perceived God’s chastisement in the human suffering brought on by disasters, including Hurricane Katrina, the Haiti earthquake, the Japanese earthquake and tsunami, Hurricane Sandy, and even the Sandy Hook school massacre. But the idea that disasters are actually divine retribution is not a new one – it stretches back to Biblical times. And the New England Puritans embraced it, enthusiastically.

Woven through all the Puritan writings on King Philip’s War is the constant refrain that the sufferings the colonists underwent in that war were ones they had rightfully earned through religious disobedience. God had warned them of His anger, the clerics claimed, citing natural signs and portents such as comets and crop failures, but New England had not heeded Him. So God emboldened the natives to mete out His punishment. They went on to claim that this was a sign of God’s love. Just as a father punishes his children because he loves them, so God “corrected” New England colonists because they were His chosen people. It’s straight out of the Old Testament.

Indians Attacking a Garrison House

Cultural and religious chauvinism is a stubborn human trait, and often begets disaster of one sort or another. We are all too easily persuaded to see ourselves and the particular religious or political group we belong to as having cornered the market on truth. It’s too tempting to regard others as ignorant outsiders who need to be “corrected” or “educated” to our ways. The assumption that we have a lock on understanding God’s purposes is a deeply Puritan idea. And a dangerous one.

Tagged: Benghazi, Colonial history of the United States, early America, fundamentalists, God's punishment, Hurricane Katrina, Michele Bachmann, New England, Puritan

April 18, 2014

The Puritan Meetinghouse

The iconic spired, white-clapboard churches that overlook the green in so many New England towns bear little resemblance to the first houses of worship erected by the Puritan colonists. They didn’t call them churches, preferring instead the term “meetinghouse.” It was a descriptively accurate term, for they did indeed use the same building for both civil and religious meetings. They were so focused on stripping away everything that reminded them of the Church of England and Roman Catholicism that they even refused to display a cross—the chief symbol of Christianity for centuries.

Old Ship Meetinghouse, Hingham, MA, By Timothy Valentine [CC-BY-SA-2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0)%5D, via Wikimedia Commons

The exterior of a meetinghouse was indistinguishable from the houses that surrounded it. The first meetinghouse in Haverhill, Massachusetts, was only twenty-six by twenty feet. As the colony grew, they built larger meetinghouses—square, unpainted wooden buildings. Sometimes, if the town had enough money, they were topped with a small turret containing a bell. A prime example of this Puritan architecture is the “Old Ship” meetinghouse in Hingham, Massachusetts.The meetinghouse was the center of the community, not only spiritually but physically as well. Early colonists were required by law to build their homes within half a mile of the meetinghouse. Though that law was no longer enforced as more and more Puritans migrated to New England, the centrality of the meetinghouse in community life did not change.

Often the top of a hill was the chosen location for the meetinghouse, which served as a watch-house and a landmark. Sometimes the hill was so steep that horses had to be tethered at the bottom of the hill, requiring congregants to walk up a precipitous path to attend public meeting. There were no trees in the immediate vicinity, since they had been cut down because of fire danger, so they were usually blazing hot in summer and freezing in winter.

Pulpit – Plimoth Plantation

People were summoned to the meetinghouse by a beating drum. Inside they sat on backless benches (box-pews came later) facing an elaborately-carved raised pulpit over which hung a sounding board. To reach the pulpit, the minister had to climb a flight of narrow stairs. The pulpit Bible would sit on a cushion of green velvet with long tassels hanging from its corners.

Meetinghouses were not considered sacred. They were simply places to assemble. On Sunday, people gathered to hear the word of God. On town meeting days, they gathered to vote on public issues. They believed that God’s presence was an all-encompassing experience and could not be separated from ordinary life and relegated to special places and times. Though their stringent regulations didn’t last, their sober piety had a long-lasting impact on the New England character. This impact is still reflected today in New Englanders’ respect for hard work, community, and pragmatism, as well as their appreciation for unpretentious architecture.

Tagged: Boston, Colonial history of the United States, Colonial laws, early America, house of worship, Massachusetts Bay Colony, meeting house, New England, pulpit, Puritan, Puritan dwellings, Puritan meeting houses, Puritans, regulations in colonial America

![By Timothy Valentine [CC-BY-SA-2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1397897974i/9343523.jpg)