Owen R. O'Neill's Blog, page 8

April 30, 2016

More on Reviews

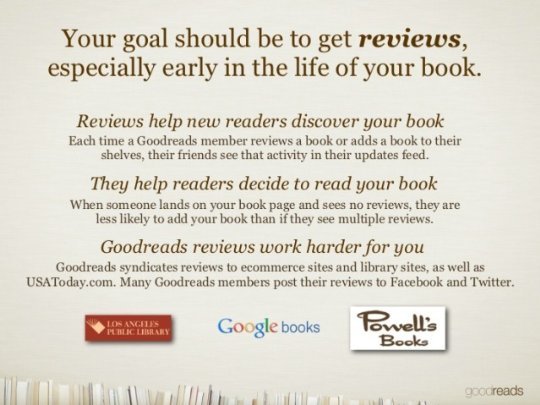

I spent some time thinking up catchy titles for this post, but I’ve decided to forego the license. A helpful member of Goodreads posted a comment there, regarding my previous article and supplied a handy graphic stating Goodreads’ stance on reviews. It’s about what one would expect. I have included said handy graphic in this post, and I will deal with it in due time.

First, a few points to be clear on what the point is:

I’m discussing reader reviews, not editorial reviews.

Observe the distinction between organic reviews and solicited reviews. [See my previous post regarding that if the terms are unfamiliar.]

I am speaking of fiction, not non-fiction.

The question is not: “Do reviews influence readers’ buying decisions?” Yes, they do. Let’s move onto the real question.

Below is a screenshot that states, in bold print Goodreads’ stance on reviews. Let us consider it carefully. Indeed, allow me to dissect it line-by-line. That will Step 1. Step 2 will put this in a broader context.

So, first line: “Goal should be. . .” Note the imperative tone, and the bold text. This a call to action. And “especially early. . .” This is specific to a new book.

What does this mean? Why should getting reviews be a goal? Note that Goodreads does not say in this statement that it is because “reviews sell books.” But by using the imperative tone, Goodreads clearly means they review benefit us and I doubt very much that they just mean striking our egos here. I invite the individual in charge of Goodreads to personally clarify this if I am mistaken, but my assessment is that Goodreads is stating this in support of the belief that “reviews sell books.”

Next, this does not apply to organic reviews. It can’t. No author can have as a goal getting organic reviews, that is simply impossible. Organic reviews happen, or they are not organic. We can have as a goal getting editorial reviews, but those are different. Moreover, they have nothing to do with Goodreads (which arguably matters). We can have any number of goals that might, in time, increase the chances that we will garner some organic reviews as a result of selling some books. But in these case, selling books is the goal, not getting reviews.

Yet, authors swapping reviews and soliciting reviews from readers are against Goodreads’ TOS. Goodreads discourages in its “best practices” that authors contact readers is a poor practice. So, in this call to action, any direct action an author would take to satisfy this goal is frowned upon.

Already, the whole statement is in trouble. In a practical sense, this devolves to authors asking other authors to review their work, or giving away their work “in exchange for an honest review” which requires a disclaimer which, in turn, damages the legitimacy of the both the review and the author in the view of some number of readers, especially when those form a large portion of the book’s reviews.

Even if reviews given in exchange for a free book do some good, organic reviews will do more good. Amazon supports my view on this by deemphasizing the former in their rating calculation.

But let’s move on.

This deserves a brief mention: “especially early. . .” Why? Ebooks do not go out of print. There is no time urgency, no deadlines, nothing. Nor have my investigations shown any support for notion reviews are especially helpful for new books. Plenty of new books sell best before they get reviews.

If Goodreads has proof that reader reviews are a sales driver for new books, and not a result of new books selling for other reasons, they need to present that proof, clearly and unambiguously, not imply it.

This problem lies at the heart of their other statements. Let’s consider them:

“Reviews help readers discover your book . . .”

I’m not going to deal with this statement here because it relates to visibility, the subject of my previous post. Suffice to say that a positive review, spread by word of mouth (which is what this amounts) will sell books. But, per the above, getting said review cannot be an author’s goal. Our real goal is to write a book someone enjoy enough to merit such a review.

“They help reader decide. . .” Yes, reviews may help readers decide to try your book or avoid your book. Positive reviews can harm your book’s sales potential and negative reviews can help it. See my previous post on this for more detail.

Bottom line: “help readers decide” does not equal “sells books” and it is irresponsible to imply that, as this point seems to.

Next point on this: “they are less likely to add your book. . .” This an unambiguous claim. I would like to see it support with data. But the real point is the implied claim that adding a book to someone’s list on Goodreads have sales value. I see no evidence of this. I see the reverse: “to read” lists on Goodreads appear to be something of a joke. In general, they do not appear to show any serious intent of ever purchasing the book, and I believe readers looking for new books to buy do not, as a rule, consult them.

Here, again the argument is “increased visibility” but I argue this visibility is of no practical worth as a sales driver, especially for new books. And—to repeat myself—this is neither amenable to, or justifies, making reviews a “goal.”

Finally: “Goodreads reviews harder. . .” Note the sales tone, it’s important. Harder than what or who? That’s the sales pitch—a statement of no value that sounds “catchy.” But examine what comes next.

The bit about many Goodreads members posting their reviews on Facebook and Twitter: what is the point here? That is unrelated to Goodreads. Goodreads cannot plausibly take credit for what their members do elsewhere. Making this claim is disingenuous.

But I’m more concerned with this part: the statement that Goodreads’ reviews are syndicated to USAToday, etc. Who’s reviews are syndicated? Yours? Mine? Or Stephen King’s?

The point here is that Goodreads does not state their policy on syndication. If they impose criteria related to a book’s sales record, then they are simply agreeing with others who use reviews as a proxy for past sale success. That destroys their argument that getting reviews should be a goal, as it shows Goodreads understands what reviews actually mean, and it’s not what that graphic implies.

The time has come to wrap this up. Last question: what is the purpose behind Goodreads’ stance as expressed in that graphic?

Consider this: Amazon is very stringent about reviews. They have evaluated what lends credibility to reviews and they actively and vigorous defend it, much to the annoyance of some authors.

Note to Authors: when Amazon pulls a review, you should thank them! They did you a favor. That review was harming your book’s sales potential. Amazon wants to sell our book more than we do. Very few of us earn our living by selling our work. Amazon does. They know more about it than we do. Trust them on this one.

Moving on: Amazon knows just what role reviews play in selling books, and Amazon’s depends on selling products. Amazon is, as I said, careful about reviews.

Goodreads is not. My family and friends can review my book. Even I can review my book, although Goodreads will state that. Amazon does not allow any of this. Amazon also does not have a rating system that allows “drive-by” ratings: a reviewer has to write something, so visitors can evaluate it.

Why the difference? I cannot say, but I will make this observation: Goodreads does not sell books. Goodreads sells advertising. The number of reviews and ratings on Goodreads are one of the things that make it more attractive to advertisers.

Getting reviews posted on Goodreads is of material benefit to Goodreads. It may be slight, but it is there and it is always positive. From the point of view of Goodreads, thinking “our goal should be to get reviews” makes good business sense.

Whether those reviews benefit us, as authors, is much more problematic, as explained in my previous post.

That statement by Goodreads in the graphic above is using bad logic and irrelevant points to exhort you and me to have as a goal something that may harm us, will usually do nothing for us, and will only benefit us when we’re already being successful.

But it will always benefit Goodreads.

I will leave it at that. The rest is up to you.

April 24, 2016

The Price of a Book—One Perspective

When my co-author and I write a book, and especially when we get ready to click the Publish button on KDP, one thought above all occurs to me: If this were the only book out there, would anyone read it?

Because no one needs to buy our book. Our book—in common with all fiction—is a luxury. We are story-telling animals: we tell them around campfires, in bars, at parties, and share them with our hairdresser. We painted them on the walls of caves and in petroglyphs many millennia before this thing called “writing” occurred to us. No one needs to pay for a story.

This realization gives the lie to all the worry about “visibility”, all the wailing about “saturation” and “competition” in the book market. If people feel like ignoring our book, they are probably going to feel that way independent of all other books in existence.

So what, then, is the price of our book?

It’s not the $2.99 or $3.99 we charge for it. That cost is trivial to anyone who has the ability to buy it off Amazon—they’d spend as much or more on a latte without thinking about it. They’ll earn that much back in a matter of minutes at pretty any job in this country.

The real cost is time—hours spent reading they will never recover. That is what we are asking of them: to spend some hours on us instead of doing something else. The few bucks we get from the sale is just a tip that helps us write more so they can (hopefully) spend more time on us in the future.

Seen in this light, what they give us in exchange for our stories is arguably the most precious thing of all, the only thing the universe does not conserve.

We strive to be worthy of that. Nothing else really matters—does it?

April 20, 2016

Ignorance is Bliss

Ignorance is Bliss

Not so long ago, when I should have been gainfully employed, I happened upon a discussion of style—styles for writing fiction, in this case. It was mighty edifying. Heretofore, I’d been aware of 1st-person and 3rd-person, past tense and present tense. Those constituted my understanding of the options available—2nd-person would seem to present insuperable difficulties as it would seem to imply either a first or third person to be second to, but maybe it’s just that my brain lacks the pliancy to bend itself around the problem.

Anyway, the discussion aforementioned informed me that my knowledge of style was paltry and barren, and all these decades I’d been sculling about in a backwater of blissful ignorance. In addition to the styles I knew of, there were modifiers: close, omniscient, and even one called “indirect”. I had to look that one up. There is a Wikipedia article on it. It made about as much sense to me as the proof of Fermat’s Last Theorem.

The foregoing added to the tonnage of Things I Did Not Know. For instance, I once learned that “that” is considered a no-no and that using “that” should only be resorted to only in emergencies. I’m not quite sure why that is. I’ve always considered that “that” is a kindly word, which at times is gracious enough to give place to “which”, but that is wholly inoffensive. I’m sorry but I cannot agree to hop on the bandwagon of those persecuting “that”. And that’s that.

One of the sins of “that”—if I correctly understood an article written by a woman who allegedly consults on such matters, and boasts many other qualifications—is that it is a “crutch word”, along with “when” and I don’t know what. “Crutch words,” she admonishes us cripple our writing. I’m sure she thinks she means well, but I’ll thank her not to refer to my writing is “crippled”. My writing is “differently abled” and I expect her to respect that.

Next, a Jovian presence called down from the lofty summits of the NYT best-seller lists, excoriating adverbs. Searching my failing memory I recalled what an adverb was— that “ly” thing. I know it well. I gather this happened a long, long time ago, perhaps in galaxy far, far away, which might account for me not hearing about it. Or maybe I just wasn’t paying attention. I can’t recall why adverbs were being picked on. I think it’s because they are “weak”.

If so, that’s just mean. Aren’t we supposed to succor the weak? I mean seriously: here’s a guy who’s made more money on one crummy book than I have in my entire lifetime, and he’s bullying poor little weak adverbs. I think that’s just wrong. I’m just a poor no-account guy who writes but at least I can open my arms and embrace adverbs. They will be safe with me.

Then I encountered ten “rules” of writing I was unaware of, apparently promulgated by someone that (from the name ascribed) I assumed was a cousin of Elmer Fudd. Fudd’s cousin said something about “said”. I don’t recall what. I do know that if you want to get a bunch of otherwise somnambulant writers stirred up, bring up “said”. The sparks will fly in no time. Why this happens, I have no idea. But it can be amusing to watch for 4 mins while you’re waiting for coffee to brew.

Now, I have to mention “had”—just for fun. Wandering aimlessly one day, I encountered a discussion about how many times English grammar allows the use “had” in row. “Had had” is well attested, and I believe even “had had had” but some daring soul might’ve been pushing things even further. That is the kind of debate I can get behind. How many “had’s” can fit in a row strikes me as the linguistic equivalent of “how many angels can dance on the head of a pin?” and perhaps almost as much fun.

I’ve learned other things as well: prologues are passé, “heading hopping” is rude, and infodumps are a cardinal sin. This last especially interests because at least two authors I know of (and probably more) have sold ten of millions of books almost solely (as near as I can tell) by employing infodumps liberally, not to say flagrantly and promiscuously. Talk about your mixed messages.

Aside from the Jovian pronouncement and Fudd’s cousin, the authority for all these “rules” is obscure. Most often, I heard cited “the readers”. Which readers? That is the (well, my) question. The ones who love Homer or J.K. Rowling? Nabokov or EL James? Hemingway or whoever wrote “Twilight”?

And who’s to say that isn’t all the same person? If ever there was a hydra-headed beast, it’s the “reader”—every head enjoying or deploring a different book.

Where does all this leave me, the poor benighted writer? Up to my knees in a morass of “rules” propounded by some Illuminati-like entities, judged by Star-chamber procedures, to “appease” a chimerical beast of dubious nature, not to say existence.

Yes—at times, ignorance truly is bliss.

April 3, 2016

Can Anyone See Me?

Almost certainly—even if you’re an independent author. Whether we know it or not (and often we don’t) visibility happens. Despite how we feel, and it is all too easy to feel lost and invisible in the seas we swim in, visibility is not so much our problem, nor can we do a lot about it if it was. Our problem is that what visibility we get doesn’t do much for us, at least in terms of selling books, which is what I’m going to start with here.

Now, before I get going I want state that some may justly claim that I’m using “visibility” in a literal and narrow sense, and what they mean by “visibility” encompasses all of what I’m about to say. Quite true. I’m insisting on the distinction because I believe the literal and narrow meaning often tends to overshadow the penumbras we attach to it, with concomitant effects on behavior. History—here the history of independent publishing—can be seen as supporting this view. (Of course, people may disagree on this point. That’s all right with me. We can take up that discussion later.)

To be explicit (and state the obvious—something I’m known for), allow me to breakdown the decision chain for buying a book. First, the buyer needs to be aware of the book. This is visibility pure and simple. Next, the book must be of some potential interest to the buyer. This conditional visibility (what a corporate type might call applicability—I won’t though) . Finally, the buyer must be convinced to invest in the book, both money and time, though it is the money that we see. This is called a sale.

The first link is where most of us feel rather helpless and where we are, in general, weakest. Amazon, to cite one example (but an important one for indie authors) has a much greater reach than almost any of us can expect, especially when we are new. So do other well-known outlets and agencies, such as BookBub. One argument for traditional publishing is that they have much greater reach than we do, and we can benefit from it. This is debatable (the benefit part) and another discussion best left to another day.

The second link is where we can exert more influence by appropriate use of keywords and categories to help prospective readers find our book, and also learning where said readers are and who they are, so we don’t waste resources gaining visibility with people uninterested in what we write.

The final link is what concerns me most, and that part of the chain is all on us. To sell a book requires one thing above all: credibility. There is no workaround or short cut to gaining credibility. (Okay, people can be conned—not going there.) This makes things tough, because we authors, especially new authors and fiction authors in particular, start out with essentially no credibility. If I were to write nonfiction on certain subjects, my professional resume would confer a degree of credibility to my work. But it says nothing about my ability to craft a story anyone would want to read. I have to “prove” that. Until I do, all the visibility in the world won’t do me much good.

To put this in perspective, my previous post is about reviews. If you believe (as I do) that if every indie author saw that post, it would not make much of a dent in the entrenched belief that reviews are necessary to sell books, then you see my point. I don’t have the credibility to shift opinion on this topic, no matter how visible that post is. (If you disagree, tell your friends!)

But all is not lost. We can go about gaining credibility in a number of ways. First, there is the way we present our work. I’m not going to venture into discussing blurbs and covers and editing and grammar. Those debates are generally more about ego than books, they are frequently nasty, and they are almost always counterproductive.

What matters is not what is “good” or “bad”, “professional” or “amateurish”, but what our audience considers credible. And that is something we need to learn. This is why asking the opinion of the vox populi on these matters typically results in a discordant and not terribly helpful chorus. Everyone brings their own notions of what is credible to the discussion, most of which will not apply, and it’s not always easy to sift out which do and which don’t.

However, I particularly want to address credibility as it relates to visibility (in the narrow sense) and thus to “marketing”—that thing we are told is essential (like getting reviews). This topic appears vex indie authors on a par with the whole review thing, maybe more so.

To speculate for a moment, I suspect this is because we feel helpless on the one hand, but on the other, we live in a hyper-connected society which displays to our bedazzled eyes the chimera of limitless visibility. Perhaps it would be better if I likened it to a mirage in a vast desert.

The problem, I believe, is made more acute by the reality this mirage both reflects and obscures. We do live in a hyper-connected society, where in principle, just about anyone is a click, a tweet, a Facebook like (or whatever) away. If only we could harness it, riches untold would pour forth at our feet. And it doesn’t help that we are told this, over and over and over—an incessant drumbeat by persons who present social media as a panacea for everything, but more than anything, as a way to separate us from our hard-earned money. In all too many cases, belief in the mirage—or the panacea (I’ve called it 3 things now)—results in broken hearts, crushed dreams, and lighter wallets.

Why?

You probably can guess the answer by now: credibility (the lack of it).

It is worth noting at this point that credibility comes in different forms, especially with respect to marketing. The first and most obvious type is the credibility that gets people to listen to us. The second and (I think) less obvious type, is the credibility that gives us the “right to talk” in the first place. That may deserve some elucidation.

We live in a society marinating in advertising. A large chunk of the information we are exposed to in the media we use every day consists of ads. Yet “no one” likes ads. No demographic (it appears) enjoys being marketed to. Yet we all are marketed to, relentlessly, and the resources expended to do this thing which “nobody” likes is a substantial part of the overall economy.

Something seems wrong here. Companies would not spend enormous sums on ads if they saw no benefit, or if doing so actually harmed their business. Yet public opinion can’t be wholly dismissed.

Answering this kōan is the concern of what I think they call “market research” and the subject of an extensive literature. It is not of interest here, except in one particular: whatever our feeling about ads, we tolerate them. We may object to a the content of an ad, and make our ire known in such a way that the company takes heed, but we don’t object in the same way to the fact that companies advertise at all.

Yet, it appears this tolerance has limits. While the public is prepared to accept that McDonalds can advertise pretty as it likes, they do not appear to feel the same way about us. As a group, we have not yet “earned” the same “right” to advertise. So our attempts to gain visibility for our work carry a cost, and we all bear that cost, to the extent that it reinforces the rather unenviable reputation indie authors have in many circles.

Therefore, we do have “visibility” and all too often, that visibility does us no favors. The inept and inappropriate use of social media by indie authors appears to have played a significant role in this. That is what happens when we seek visibility without first building up the necessary credibility.

I’m harping on this because it is a new problem. Back in the day when McDonalds was small, visibility and credibility went hand in hand. Society was not hyper-connected, and to get visibility required going through gatekeepers. If one had not built up some credibility, one did not get access. (Having made a enough money to pay said gatekeepers was a form of credibility. It still is.)

These days, we can publish as we please—a very good thing—and “market” as we please. But that puts the onus on us as individuals to build credibility, and market intelligently once we have, to thus gain visibility that is helpful, not damaging.

In short, building credibility is its own reward. Once we have it as individual authors (and someday as a group), our lives become much easier and we find we probably don’t have to do much marketing on our own. All the various hidden (and powerful) factors tend to come to our aid, and the word spreads without much effort on our part.

That is, people visit our websites, sign up for our mailing lists, get interested in our giveaways, follow us if we are on whatever social media they frequent, and promote us via word of mouth. Our books sell as a result, and success breeds success.

Do things the wrong way round, and we usually get the opposite reaction. In that case, if we want to make money off our writing, we’d probably do better by printing something catchy in bold black letters on a large piece of cardboard and standing on a busy street corner.

We are writers, after all.

March 31, 2016

Support Indie Authors April Sales Event!

Support Indie Authors is holding a sales event this Friday, April 1st. Over 60 books are being offered for free or just 99¢. There is work for every taste on sale. This is a great opportunity to pick up some discounted reading and introduce yourself to a whole slew of indie authors.

Click here get to all the details: Support Indie Authors April Sales Event

March 26, 2016

Brother, can you spare a review?

I warned you that I planned to talk about reviews, and now I’ll make good on my threat. Of the various beliefs I’ve encountered circulating within the indie author community, few appear to be as deeply entrenched as the idea that reviews are critical to a book’s commercial success. I want to examine this notion from a few different angles. What you want to do is your own business.

To begin, I will make 3 points, which I will then develop. This is so you can decide if you want to stick around.

1. A thoughtful positive review by someone who actually bought your book and read it is a great gift. You have every right to feel good about these: your work touched someone and made a positive imprint on their lives and they were moved to tell “the world” this. That is a wonderful thing. It lies at the heart of why we create.

2. Reviews do not sell books.

3. Reviews do not provide valid feedback on your writing, and while #1 above is undoubtedly true, reviews can be dangerous to your well-being as a writer.

Okay, I kind of snuck two points into #3, but so be it.

Now, if you are an author, you can believe those points, in which case there’s no need to read the rest of this. Or you can simply deny these points and go off believing the “conventional wisdom” (meaning misinformation) about reviews being necessary to sell books, in which case you’re setting yourself up for a lot of needless stress.

Or you can read the rest of this post, which will explain how and why those points above are true. Your call. But before you decide, I want to clarify that I mean fiction. Nonfiction has different characteristics. If you’re an author who writes nonfiction, you can ignore most of this. (Probably all of it.)

Nice to see you here!

I think #1 speaks for itself and I don’t need to say much more about it at this time. Later perhaps I will expand on it in another post.

On to #2.

First, allow me to state I’m focusing on reader reviews here, not editorial reviews. Editorial reviews are different kettle of fish, and I’ll touch on them later, but reader reviews are the main issue, in large part because meaningful editorial reviews are harder for indie authors to come by.

Reader reviews divide into reviews which come along organically from readers, and reviews the author solicits from readers. These latter are required to be disclosed, both by sites’ TOC (e.g. Amazon and Goodreads) and FCC regulations. This is why we often see this statement: “I received a free copy of this book from the author in exchange for an honest review.”

Organic reviews and solicited reviews mean different things and convey different impressions to prospective readers. Neither sell books. Allow me to expand on that.

When I say: “Reviews do not sell books,” I am guilty of boiling down a more complex issue into a simple statement of principle. The principle may not be accurate in a mathematical sense, but it’s true in that if adhered too, the adherent will never go wrong.

Organic reviews are a trailing indicator of past sales: a book must sell to get them. If a book has 500, 1000, or 10,000 organic reviews, it has sold quite well. The fact that it has sold that well may often have a positive effect on a person’s buying decision. Put another way: popular books sell by virtue of being popular.

But those organic reviews did not make the book popular in the first place. They did not even appear until after the book sold, maybe weeks or months after. So the book initially sold for some other reason, and in enough quantity to garner a significant number of reviews. So “reviews do not sell books”, QED.

What about solicited reviews? Those often come from ARCs (advance review copies), which the author sends out to get reviews and generate “buzz” and get some “visibility”. Do they sell books? They might in some cases, if they are viewed as being credible, but they also might hinder sales, if they are not. Generally, the evidence is that solicited reviews hurt sales more than they help. Why is this?

First, if organic reviews mean a book has sold well in the past, solicited reviews mean that an author has succeeded in getting people to write reviews in exchange for a free copy. That ability says nothing about the author’s ability to write a book any particular person will enjoy.

Next, that review was bought. Sure, it says “an honest review” — right. That’s like a used car salesmen saying the beater he’s trying to dump is an “unbelievable deal.” Does every person feel that way? No. But every person who does feel that way is a lost sale; perhaps without actually looking at the book. And a considerable number of people do feel that way. That’s a considerable number of lost sales: people who might have given the book a chance otherwise.

What solicited review will tend to have credibility? This one: “I received a free copy of this book from the author in exchange for an honest review. It stinks.” People may not care or agree, but most will tend to think the reviewer is being honest. Is that review going to help sell a book? Doubtful.

Now a few solicited reviews in with a bunch of organic ones aren’t going to do much harm. They aren’t doing much good either. But if solicited reviews make up the bulk of a book’s reviews, what message can this send? This one: “I’m desperate for reviews! Because I think my book SUCKS!!!”

Okay, the author didn’t think that. The author believed they were following the “rules” about generating “buzz” and getting “visibility” and that “reviews are ABSOLUTELY necessary” and all that. But the author is just drinking the Kool-Aid peddled to authors. The author is not listening to readers or thinking like a reader: they are thinking like an author who really cares about getting sales now.

Every solicited review is statement that the author could not wait for the real reviews to come in, or thinks their book isn’t good enough to get positive reviews on its own, and these can add up to an ear-splitting wail of desperation. Does that sell books? Doubtful.

If you want the proof of the foregoing, go to Amazon and look at the books ranked way down around the million mark or so, and check the reviews. See how many have solicited reviews and the number of solicited reviews they have. Compare them to books in the top 100,000. Chances are you won’t see a lot of difference over a large sample. That’s because different markets have different sensitivities, but the main point is that it’s not the reviews which are responsible for the difference in sales. Over a large sample, it’s not possible (as far I was have been able to determine) to accurately rank books based on the number of reviews.

I will add a further note. Amazon, which probably knows more about selling books than anyone (they have about ~70% of the eBook market, where us indies are heavily clustered) does not treat all reviews the same. About their star ratings, Amazon says this:

Amazon calculates a product’s star ratings using a machine learned model instead of a raw data average. The machine learned model takes into account factors including: the age of a review, helpfulness votes by customers and whether the reviews are from verified purchases.

Now, which do you think Amazon weighs more heavily? Reviews by verified purchasers? Or solicited reviews? If your money is on verified purchasers, you’re with me.

I think that deserves a QED.

All right, what about editorial reviews?

First, a bit of history. Back in the early 90s or late 80s (I don’t recall), I read an article about market behavior, which dealt at some length with the question of reviews. The author did this by pointing this interesting fact: for new movies, reviews were critical. Movies lived or died by the reviews they got just before release. For books, reviews had essentially no effect. Book reviews were about vanity; as marketing tools, they were worthless. (I seem to recall he stated this was “well-known.”)

Given the times, this obviously refers to editorial reviews. The author was speaking overall, and thus the second point was heavily influenced by genre fiction. At about this time, this conclusion was born out by the fact that publishers of genre fiction emphasized plugs from popular authors far more than reviews. This practice remains in force today. Some authors appeared so often on book covers, I would not be surprised to learn publishers were holding seances to get them to plug books from beyond the grave! Editorial reviews are mentioned these days, but my observation is that they appear more on hardcovers than trade paperbacks; when constrained by space, the reviews tend to be reduced in favor of the plugs. (I think it is possible that buyers of hardback books put more stock in reviews than buyers of paperbacks. If one is shelling out $25 to $35, one probably wants all the info one can get.)

For literary fiction, reviews do have weight if they from the right publication. The NYT Review of Books has great credibility with readers of literary fiction, and a glowing book review there will sell that book. But unless you are Salman Rushdie or have a Nobel Prize of Literature, you’re probably going to have a tough time getting that glowing review. If you are an indie author, you can’t get it, because the NYT Review of Books bans us from their ranks. So do most established review publications.

As an indie author, you can buy an editorial review — Kirkus sells them — and it may or may not do any good. It seems to be a mixed bag and I’ll note that I rarely see Kirkus reviews mentioned these days on books from Big 5 publishers. Kirkus reviews (my observation) do not appear to hold a great deal of credibility. I suspect this especially true when it comes to indie authors, in particular.

Credibility is the key. In some genres, editorial reviews by credible sources carry more weight and are easier to come by. Romance appears to be a prime example. A favorable mention on a premier romance blog can give a book a large boost and start it down the path to commercial success. For sci-fi (what we write), that appears to be much less the case.

Each genre is different, and an author is well served by diligently researching who and what has credibility in his or her particular genre, and attempting to get favorable mention from them or that. That might include editorial reviews.

I offer that as the exception that proves the rule.

I think we are done with “reviews don’t sell books.” On to Point #3.

This final point — reviews do not provide valid feedback on your writing, and can be dangerous to your well-being as a writer — is, I strongly believe, the most important. If you hold to the dogma that reviews sell books, the worst thing that will probably happen is that you’ll waste time, you may damage your book’s chance of selling, and you will be confused when it doesn’t. You might equally well be confused when it does. (After-the-fact rationalizations of success are extremely common.)

But this notion — that reader reviews provide useful feedback on the author’s writing — is damaging and dangerous. It needs to be extinguished, utterly and ruthlessly. Of all the ideas an author can hold, this is the worst. I am not prepared to be temperate on this point and say “Well, maybe, sometimes …” No. Never. To hold this idea is to court, indeed embrace, the self-destruction of one’s life as a writer. Allow me to prove this:

We once received the following feedback from two readers who had strong opinions about one of our main characters. The first felt he was warm, kind, generous, deeply caring and supportive. The second felt he was cold, callous, self-centered, manipulative and deeply untrustworthy. Both readers, however, liked the book quite a bit, to judge by their other comments.

Now, one might leap to the conclusion these two readers were deriving their opinions from different parts of the story. No. Both readers cited the exact same scene as demonstrating why they loved the character, on the one hand, and were less than fond of him (shall we say), on the other.

Both readers were obviously reading into this scene what they wanted to, and reacting in diametrically opposed ways, because of reasons that are particular and personal. In short, they were, in that sense, independent of our writing. Usefulness as feedback on our writing? None.

Now this is an extreme example. The usefulness of extreme examples is that they make things clear. What is true of this example, is true of all such examples to some degree. It is simply impossible to know what goes on in people’s mind when they read our work. Therefore, it is useless to try to second guess it and harmful to worry about it.

Further — and I realize nothing further may be needed, but I warned you I was not prepared to be restrained about this — in general, roughly 1% of readers, or even less, leave reviews on-line. And they are a different breed than those who do not write on-line reviews. In our case, we have received a sizable number of private emails (in comparison to our number of reviews) from readers who have never posted review. They conveyed their opinions in another way. Most (over 99% in our case) say nothing at all.

To allow such a miniscule, vocal and unrepresentative fraction of one’s readership to have any influence whatsoever on how we write is absurd. Authors who believe otherwise will either murder their craft in hot blood and tears, or they will get over it.

So what does it say, if the bulk of our reviewers don’t like our book? If it says anything (and a lot of reviews must accumulate organically to tell this — at least 50, I would say, probably more), it says that somehow our book isn’t getting into the right hands. However, 50+ organic reviews show that our book is selling, so maybe we don’t much care.

I think at this point, I have made clear how I feel about reader reviews. For other readers, they can be helpful. It is for other readers that the reviews were written: to express a subjective opinion that might provide clues to readers of like mind. That is all.

For authors, I’ll reiterate that they can be a wonderful gift, balm to our ravaged souls, evidence that we touched another person and enriched their lives — all sorts of good things.

Or they can be a deadly toxin that throws us into agonizing convulsions; that cripples, and may even kill, our author-soul. If you value that part of you, treat them with extreme caution.

March 20, 2016

Does anyone know how to play this game?

A few years ago (you can look up the history if you like), someone got the idea to let pretty much anyone who felt like it upload a story and hit a “publish” button to offer their work for sale. The tumult has not died down yet. Literature was being cheapened and degraded, the market was being flooded with all manner of trash, not to say filth; the market was being saturated, unfettered competition would strangle new and worthy voices, readers would not be able to find anything (often meaning “find my book”), and so on.

This hue and cry has been raised before, of course, back when paperbacks were introduced. And I’m pretty sure that when a fellow named Gutenberg had this crazy idea about a new invention that would vastly increase the number of books available, there was much wailing and gnashing of teeth. I far as I can tell, whenever there is a change that increases range of what is available for “the masses” to read, some people get bent out of shape. A few of these people think it is just not right for people to read: they start “getting ideas and thinking…” That is probably an exaggeration in most cases, but the idea that people’s reading should be restricted for their own good is not. This idea is foundational to the gatekeepers of publishing, who traditionally decided what the reading public was allowed to buy and what they weren’t. It is also popular among some published authors who fear the “competition” of new authors who didn’t have to jump through all the hoops they did to join their “exclusive” club. Basically, anyone who had a share of the pie and believed that this is a zero-sum game (which is a depressing large number of people) did not see much reason to welcome this innovation. To these poor benighted souls, defending their share of the pie became the order of the day. The notion that the pie itself is growing and that benefits everyone is foreign to them.

My point in devoting a paragraph to this is not just to decry (or if you prefer, rant) about people standing in the way of beneficial innovations yelling “Stop!” for reasons selfish and/or irrational, but to give some context for the current state of affairs. Innovation does create turmoil, and turmoil creates opportunity and not all those opportunities are positive. That’s why I titled this: “Does anyone know how to play this game?”.

The short answer is: No. Strictly speaking, no one can understand a chaotic system because understanding is impossible, even in theory.* But there is no shortage of people who will tell you they do. When the applecart is upset and the apples go rolling off in all directions, there will always be a bunch of clever fellows claiming they will tell you how to gather more apples than other people, if you pay them some of the apples you already have. These people are called “marketers”. Some of them maybe good and worthwhile individuals, but history teaches us that what marketers primarily excel at selling is themselves. When things fall into chaos, those who are adept at marketing tend to fall back on selling themselves because that is the one thing they can reliably sell in a chaotic environment.

This works for a deceptively simple reason: in a chaotic environment, anything can be shown to “work.” True causality is difficult to establish in the best of times, and chaos makes it next to impossible. Thus, just about any theory of marketing can be supported. And if it fails for you, well . . . you did it wrong.

This is perfect for those selling “guaranteed” schemes to sell our books. It is not so great for us.

Bottom line: With some diligence and proper attention to detail, most anyone can learn as much about playing this new game as anyone else. I understand if some do not find that agreeable. That’s okay. All of the foregoing (and much what will follow in future posts) can be boiled down to one simple principle: it’s better to trust in luck than in people who claim they can beat it.

* However, that does not mean all is lost. This is a theme I will develop at a later time.

March 18, 2016

A Matter of Taste – Why Taste Matters

Writing fiction is a bizarre business, especially when it becomes a “business” and not a purely personal pursuit. Instantly we are pummeled by contradictory factors. On the one hand, judgments about fiction are purely subjective. On the other hand, we are constantly told to improve and “refine our craft”. But given any lack of what it means to “improve” – since any and all criteria are subjective and therefore meaningless in any broader sense – the concept of “improvement” is likewise meaningless.

This is called logic.

One might also say it’s called “missing the point”. “Subjective” is one of the tar pits writers face: it’s all too easy to get mired in it and disappear from sight. (This can also be said about a great many other things.) Some attempt to pull themselves to safety using numbers (far too many really): FB likes, twitter follows, number of reviews, sales and whatnot. Of course, insofar as those numbers reflect popularity (subjectivity applied en masse), they are likewise worthless as means to judge whether our writing is “good” or if we are “improving”.

So numbers don’t help much getting us out of the tar pit, in my view. Maybe they make us feel better while sinking.

Is there a solution then? I think so: don’t go there. First, decouple popularity from any notion of quality. Next, forget about numbers. Numbers are data; they are not wisdom. Those are the easier parts. But how to deal with the notion of quality when the matter at hand is subjective?

The answer, as I conceive it, it so recognize that subjective judgments exist on many levels. Once upon a time that was this thing called “taste” and it was held to be “good” or “bad” according to the tenor of the times, and the place. These days, in some circles at least, the concept of taste seems to have been replaced with the concept of “cool,” which is similar to taste but usually involves even more sneering, with a soupçon of ennui. Many people object to the notions of “good taste” and rightly so, as it leads to snobbery. “Cool” leads to much the same thing, but we tend to use bad words for that.

But between them, there is a difference. Taste reflected upon the inherent qualities of a thing; “cool” reflected more on the thing’s superficial appearance. “Cool” therefore tends to be deceptive in ways taste does not. Taste, when it leads to snobbery, is simply annoying and rude (which is bad enough).

But why does taste matter, as I claimed in the title? Because of those levels, I mentioned – or layers, if you prefer. Reality is multilayered, multidimensional, and subtle. To appreciate reality requires one to be attuned to these layers, dimensions, and subtleties. Appreciating reality more fully allows us to live richer, more satisfying lives. It doesn’t matter much that we agree on the merits of these often subtle aspects, just that we are able to experience and appreciate them. That has worth in its own right.

Now, some may argue that “richer, more satisfying lives” is itself a subjective judgment, and they are correct, to a degree. But I will offer a more practical reason. Very old and very true wisdom tells us that “the devil is in the details”. And if we can’t see those details, we can neither see the devil nor deal with him successfully when he arises.

This is one way the devil gets us by the throat. And that is not subjective, as many people discover to their cost.

March 17, 2016

Hello World!

Hello! By default, WP calls the first post “Hello World”. The idea is that you’re supposed to change it. At lease, I assume that’s the idea. But I’m not going to (except that I did capitalize ‘world’) because I can’t think or something better to say right now.

I was urged by some people who should know better to start a blog about writing and publishing, mostly self-publishing or (if you prefer) independent publishing. People need to learn to be careful what they wish for. Yes, I’m an independent author (sometime called an “Indie”) and have been for some years. (Before that I was other things.) For better or not, I will write about my experience, observations, assessments, judgements and conclusions about the crazy business of publishing. I will also ramble about the downright-insane (or so it often seems) avocation of writing.

What I won’t do here is talk about my books. First of all, they aren’t my books, as I write with a co-author these days. Next, they have nothing to do with my purpose in writing this blog. So I won’t even list my books. If you want to find them, you can. At least, I think you can. Given how common my name is, maybe not. Who cares? I doubt very much that’s why you’re here.

Another thing: some folks have accused me of being Johnny-one-note-on-the-kazoo when is comes to writing and publishing. Allow me to assure you this is false. My kazoo has at least two notes, maybe even three. But in the spirit of fairness, I will warn you there are some thing that could come up a lot.

The first is fortune, fate, or plain old luck, whatever you want to call it. That’s why I called this blog “Outrageous Fortune.” The second are some of the myths and delusions that saturate this business, especially the asinine notion that reviews are ABSOLUTELY NECESSARY to sell books. The third is that I hate rules. (You can guess what I think of those who propound them.) In this business, rules are a counterfeit foisted by the arrogant and/or unscrupulous on the naive and/or unsuspecting. No doubt you will hear more about this.

Finally, you’ll note that I love parentheticals, I am rarely concise, my punctuation is sometimes dubious, and I can’t proofread worth a damn. If these things bother you, I’m afraid you may not find reading this blog congenial.

That’s all for now. A hearty welcome to anyone I haven’t run off yet.